Abstract

Grief is often seen as a personal response to losing a loved one, but it can also arise from the loss of deeply held values and identities linked to social, structural, and religious spheres. Political grief is a unique form of this, stemming from political policies, laws, and social messaging that certain groups perceive as losses. As societies face political decisions and systemic failures, grief can emerge from losing trust in institutions, shared beliefs, and a sense of belonging. An outgrowth of political grief is a strain on relationships due to polarization, heightened by threat-activating events and resulting tensions. Many people turn to religion to counter feelings of vulnerability and incoherence in today’s political climate. While this may relieve anxiety and provide stability, it can also exacerbate some sources of grief. Understanding these dimensions is crucial for addressing political grief’s broader implications, as individuals and communities seek meaning and attempt to rewrite their narratives in adversity. This discussion includes defining grief beyond death-loss and exploring the interplay between social/political structures and culture. It also considers specific threats and responses, including religious alignment, focusing on recent events in the United States.

1. Introduction

Grief is most commonly understood as an individual response to the death of a loved one. However, grief may also result from the “death” of deeply held values, ideals, and identities that originate in social, structural, and religious spheres. A unique form of grief that has significant relevance to current world events is political grief, which occurs from the implementation of political policies, laws, organizational norms, and social messaging that are experienced as losses to specific individuals and groups. As societies grapple with the implications of political decisions, violence, and/or systemic failures, feelings of grief can emerge from the loss of trust in institutions and leaders, loss of collectively held beliefs and values, and the loss of a shared sense of belonging.

Another aspect of political grief is the impact on relationships due to the polarization that occurs in its wake, often intensified by exposure to threat-activating events and the ensuing tensions that they foster. Many individuals turn to various expressions of religion as a means of countering the sense of vulnerability and lack of coherence that is present in the current political milieu. While embracing religion may relieve anxiety and provide stability, there is also the potential to exacerbate and perpetuate some of the sources of grief that initiate this process. Understanding these dimensions is crucial for addressing the broader implications of political grief, as individuals and communities seek to find meaning and attempt to rewrite their narratives in the face of adversity. This paper will begin by providing a definition of grief that moves beyond death-loss, followed by a discussion of the interplay between social/political structures and culture in grief. The impact of specific threats and potential responses to these threats, including identification and alignment with religion, form the undercurrent for the response to threats and the political grief that is occurring in many places around the world, but more specifically focused on recent events in the United States.

2. What Is Grief?

Before delving into political grief specifically, it might be useful at this point to review current understandings about grief and the grieving process. Early explanations about grief were that it was the result of a severed attachment bond between the deceased and those left behind. The broken attachment bond was assumed to be what triggered the grief response (Stroebe et al. 2014). This view changed after research in the 1990s demonstrated that most bereaved individuals continue with a relationship in some form with their deceased loved ones, countering the previous assumption that the attachment bond between them was severed and broken after death. This research led to the framework of the Continuing Bonds Theory of Bereavement (Klass et al. 2014). The question then arose: If grief was not the result of a broken attachment bond, what activates the grief response? Many researchers and theorists in the field discussed the role of meaning as it relates to loss and grief. For example, Neimeyer (2000) indicated that a significant loss results in disruption of the coherence of one’s life narrative, leading to a profound sense of disequilibrium and a painful sense of meaninglessness. Attig (2001) indicated that significant losses cause the shattering of one’s way of being in the world, requiring the grieving individual to begin a difficult process of ‘re-learning’ how to be in a world that is now strange and void of what previously provided a sense of congruence and meaning prior to the loss. These examples highlight the existential aspects of loss and grief.

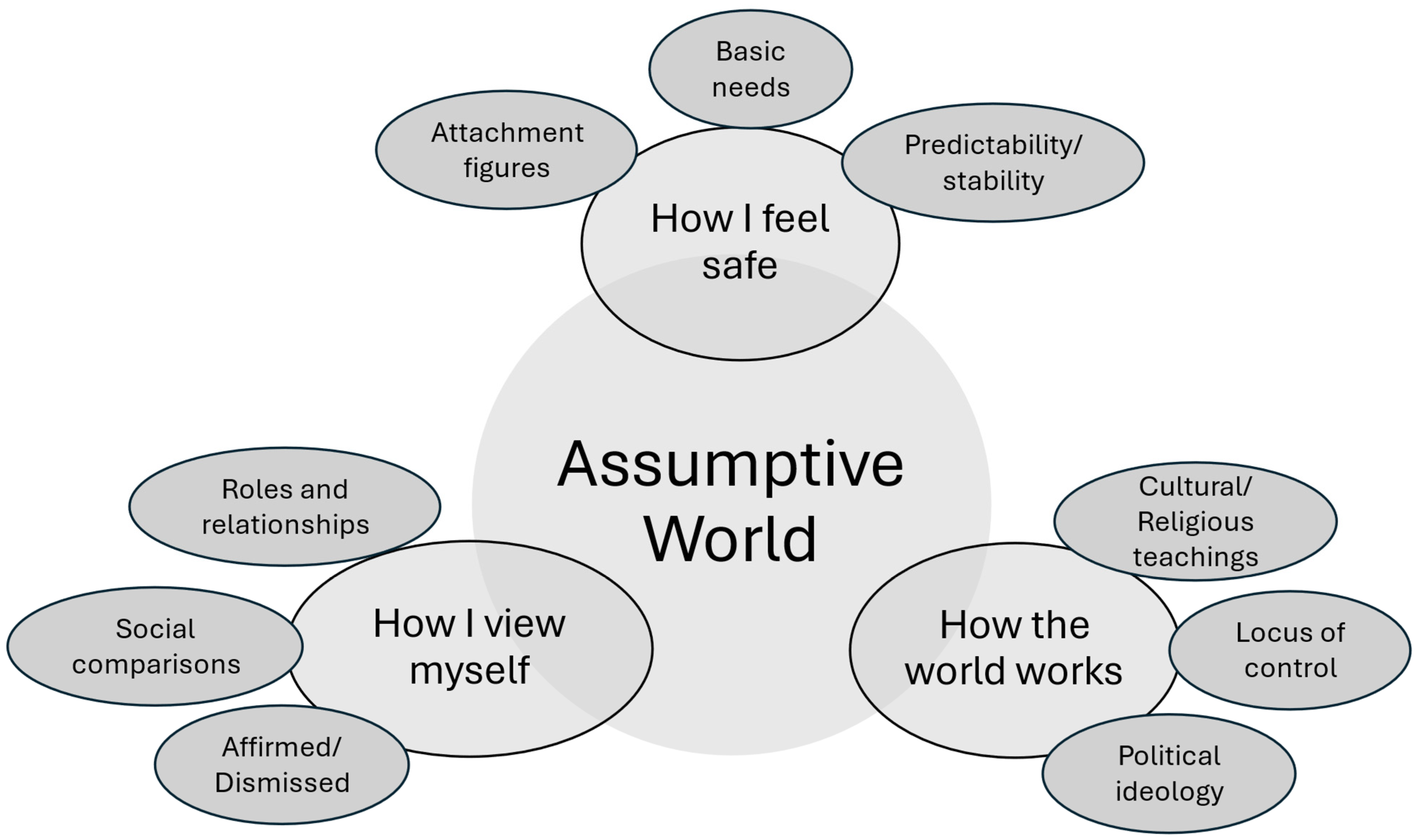

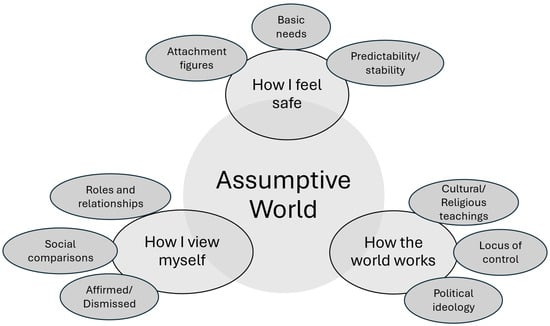

Several scholars have discussed the concept of the assumptive world in relation to grief. The assumptive world is formed very early in life, most likely in tandem with the attachment system, and shaped through various life experiences as one grows and matures. Janoff-Bulman (2010) suggested the three main aspects that comprise the overarching assumptive world are that (1) the world is benevolent, (2) the world has meaning, and (3) the self is worthy. Harris (2022) adjusted the components of the assumptive world to include life experiences that might not necessarily lead to an understanding of the world in a positive way. The key here is that the assumptive world develops and is maintained to preserve coherence, meaning, and predictability for the individual, and that may include positive or negative views about aspects of life, such that people may not all be good or the world may not be benevolent. For example, a child who has grown up in a stable, loving home will have a completely different assumptive world and understanding of relationships than a child who has grown up in the foster care system and has been bounced around between different homes. Harris’ (2022) description of the assumptive world includes the following three main areas:

- How an individual finds safety and feelings of safeness.

- How an individual explains why things happen, such as their understanding of a sense of justice or cause and effect (sometimes referred to as how the world should work).

- How an individual views themselves, including their roles and how they fit into their social networks.

Figure 1 provides a visual representation of these aspects of the assumptive world.

Figure 1.

Aspects of the Assumptive World.

Parkes (2014) described the assumptive world as the core aspect of one’s deeply abiding beliefs about the world around them, including their place and sense of belonging in the world and for some, a relationship to an entity that they believe to be transcendent. Most of the time, these assumptions are in the background, and not in our conscious awareness. As we live our lives, events may happen that challenge our assumptions, and we can usually find ways to assimilate or accommodate “bumps” to our assumptive world. However, when a significant aspect or the entirety of our assumptive world is challenged beyond our ability to integrate or accommodate events, we experience a shattering of this core aspect of ourselves. This shattering is not simply an example of cognitive dissonance, but rather a deep upheaval that leaves us floundering, disconnected, and unable to find a place to ground ourselves. A crisis of meaning, identity, and coherence is felt as a profound loss, activating the grief response. In essence, it is the loss of our assumptive world and the meaning that it provides to us that triggers our grief. A poignant example is from Elie Wiesel, a holocaust survivor who was eventually awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his work on human rights. In his well-known book, Night (Wiesel and Wiesel 2006), he describes his inability to understand how a God that he associated with mercy could allow such horrific things to happen and not stop the Germans when it was within His power to do so. In speaking of his time in Auschwitz, Wiesel wrote that he would “never forget those moments that murdered God and his soul and turned his dreams into ashes” (p. 34). This is an excellent description of the shattering of one’s assumptive world. The grief associated with this shattering was profound and completely life-altering for Wiesel.

Our fundamental beliefs about how life should unfold can be profoundly disrupted by experiences that clash with our understanding of the world and ourselves. Relationships can end. Estrangements happen. Our health can abruptly decline. Infertility can dash hopes of becoming a parent. These upheavals create a sense of imbalance, compelling us to reevaluate our identities and beliefs in a world that no longer aligns with our expectations or what we have been taught is true. At these times, we find ourselves in a reality that contradicts our assumptions and previous ways of living. The grief we experience stems from the loss of our assumed reality and the security and predictability it once offered. Thus, grief can arise from losses related to death as well as those not directly involving death. Sometimes, what we mourn is internal—our hopes, dreams, innocence, or the self-image we held before our beliefs were rendered meaningless by a reality that is nothing like our expectations of what life should be (Harris 2020).

3. The Role of the Social Context and Structures

While grief is no longer viewed solely as a reaction to the disruption of an attachment bond with a deceased loved one, the significance of attachment continues to be a crucial element of our development, growth, and sense of self. We inherently need to feel a sense of belonging (Eisenberger 2012). Our survival depends on the attachments we form, and the individuals within our social circles greatly influence us. There exists a dynamic interplay of reciprocity and exchange between a person and those close to them (Gilbert and Simos 2022). Moreover, our perceptions of the world are shaped by the social and political contexts we inhabit and identify with. Although losses are often seen as personal experiences, the broader social and political environment plays a key role in determining whether specific losses are recognized or deemed valid and whether support is offered for particular experiences of loss (Doka 2020).

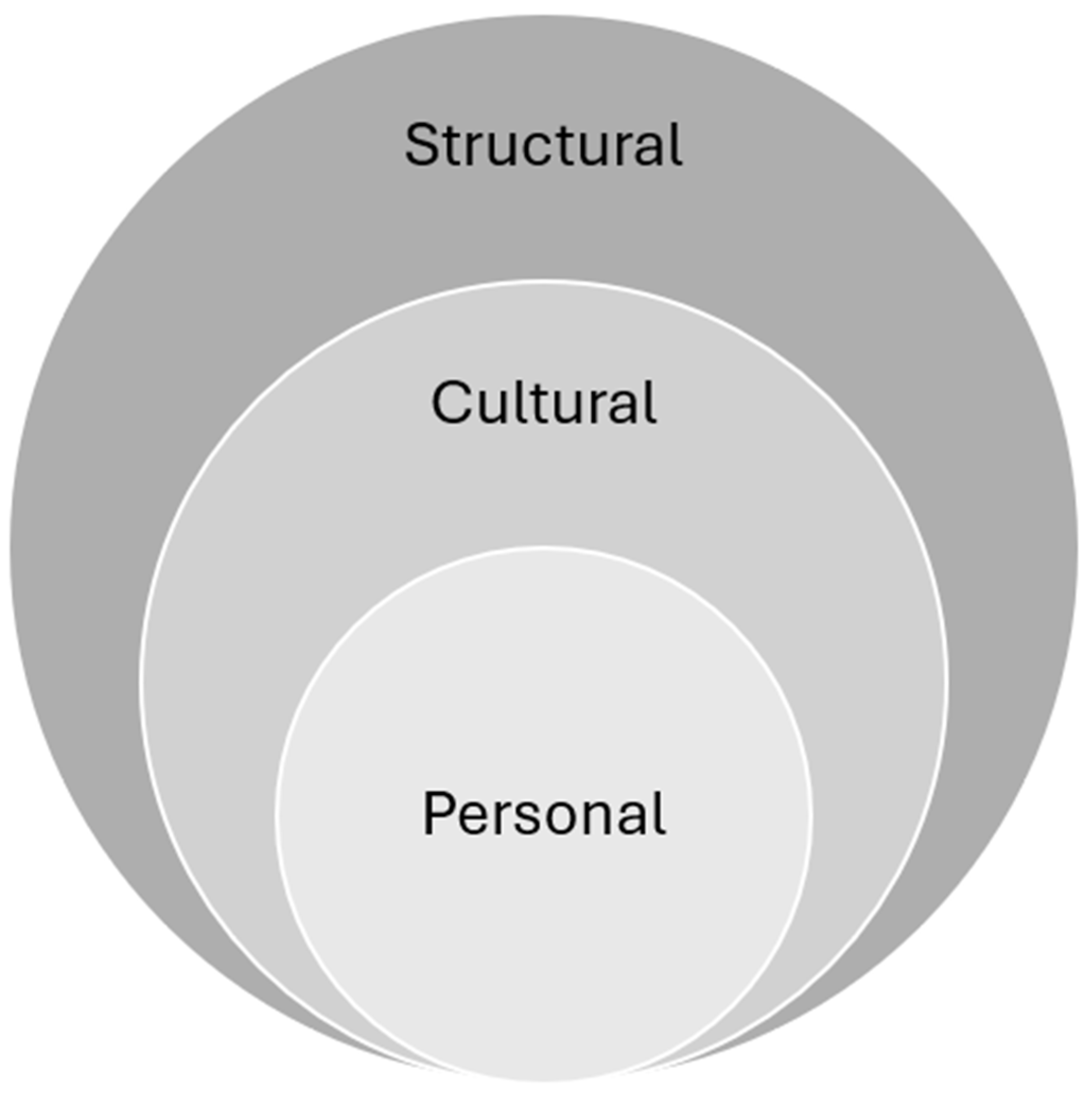

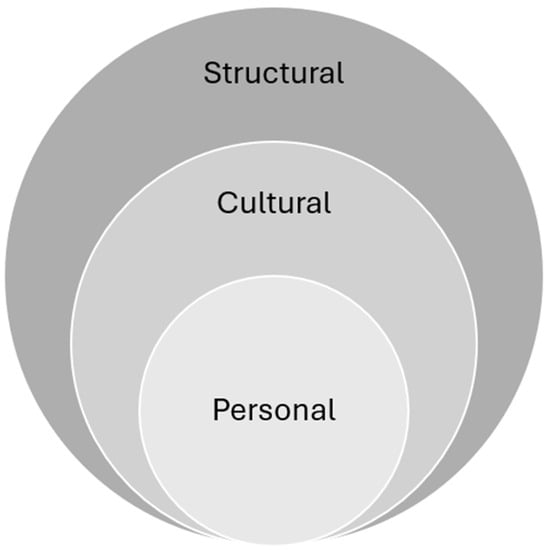

Human experience can be described in layers, where the individual (or micro level) is situated within a local network of friends and family, which in turn exists within a broader social and community context (mezzo level). This framework is further encompassed by overarching structural and political influences (macro level). Every individual experience is viewed through lenses that are inherently social, cultural, and political. These layers are interconnected, and in reality, it is impossible to distinguish them from each other. Thompson (2021) emphasizes the necessity of considering not only the personal aspects but also the cultural and structural dimensions that inform an experience, a concept he refers to as PCS analysis. Figure 2 illustrates this model.

Figure 2.

PCS Analysis (adapted from (Thompson 2021)).

The personal level encompasses the actions, attitudes, and feelings experienced or expressed by individuals. The cultural level involves shared understandings and cultural norms. Lastly, the structural level addresses attitudes embedded within and enacted by social institutions, policies, and government practices. To illustrate this analysis, we look at Robert, a 90-year-old white retired military officer in the USA1. He grew up in eastern North Carolina and picked tobacco to help his family before he joined the military in World War II. Although he moved to several places during his career, he always considered this part of North Carolina to be his home.

Personal: When he retired after 40 years of military service, Robert moved back home. His distinguished career left him financially secure and able to afford a very comfortable lifestyle. However, as he got older, he suffered from severe arthritis in his back and knees, which limited his mobility, and he required help with his activities of daily living. Fiercely independent, he felt a sense of shame and self-loathing over his inability to take care of himself. He often talked about his life not being worth living because of his limitations. Robert also struggled with the fact that most of the personal care workers who were sent to help him were persons of color. Having these individuals in his personal space bothered him immensely. As a result, he often refused care and could go for days without bathing. His daughter was frequently called by the administrator of the senior’s residence where he lived because of his attitude toward the staff and his refusal to accept the care that he needed.

Cultural: Robert grew up in an area of the U.S. that was torn apart by the Civil War, which even after more than 150 years, has left lasting scars on those who reside there. Those scars include racism. When he was younger, he was taught that black people were not to be trusted and that they would steal from white people if given a chance. He remembers hearing his father and grandfather talk about their resentment toward black people, complaining that they took government handouts and were lazy. All his childhood heroes were white men who had financial means and were independent. Robert also attended church regularly when he was younger, where the messages indicated that God had uniquely blessed America and that the country had a mission to the world. He felt proud to be an American. The post-civil war attitudes and WWII culture that informed his way of seeing the world reinforced the messages that white American men had a special dispensation from God to take what they needed, suppress those who threatened them, and be the saviors of the world.

Structural: In his career, Robert eventually was promoted to a high rank and asked to serve on the Joint Chiefs of Staff, advising the President on military matters. He helped set up military policies to defend the country should it be attacked. He also voted for and financially supported conservative politicians whose perspectives about the country, religion, and appropriate leadership matched his own. These politicians enacted legislation that made sense to Robert, including tax breaks for those who were successful, the empowerment of police, especially in areas that were predominantly black or racially diverse, and supporting conservative agendas at all levels of the government. The laws passed by these politicians ensured that the world, as Robert knew it, would continue to define the country in the ways that made sense to him.

This section emphasizes the importance of understanding the social context surrounding loss experiences and recognizing the interplay between individuals and their environments. Looking at Robert’s behavior toward the black caregivers needs to be seen in the context of his culture and the structural elements that reinforced that culture and his personal worldview. Robert grieves the loss of his independence and youth, which were a core aspect of his assumptive world. He is no longer the strong, independent man who was valued as such by a culture that rewards these attributes. In his dependent state, he is vulnerable and unable to exercise his choices as he once could. On top of having to let go of so many things that gave his life meaning, he is forced to confront his prejudice in a way that further seems to rob him of his choice. The issue here is not whether we would agree with Robert’s assumptive world or debate the ethics of his worldview. Rather, it is important to note that individuals are intricately enmeshed with the culture that forms their worldview, which is reinforced by structural elements that stem from the individual and cultural levels in an ongoing feedback loop.

While a loss may be subjectively evaluated and felt by an individual, its origins can often stem from uniquely social and political factors (Thompson et al. 2016). Grief can be experienced both individually and collectively; collective grief occurs when a loss impacts a group and shatters commonly held assumptions. The shared experience of loss and mourning during the COVID-19 pandemic is an example of collective grief. Key concepts related to the social context of grief highlight that we are:

- Inherently social beings with a fundamental need to belong. It is impossible to separate individuals from the families, society, and culture they inhabit and personally identify with.

- We are conditioned to be attuned to social cues, which develop and shape our experiences.

- Feelings of pain arise when we face rejection, shame, or ostracism from our social groups, reinforcing our drive to conform to the social norms and expectations of the groups where we either belong or wish to belong (Harris 2022; MacDonald and Leary 2005).

Building on the description of the assumptive world construct, and how our interaction within our social spheres forms it, we can examine the experience of loss in a more nuanced way. Our interactions with these various influences shape our assumptive world. Therefore, events that challenge any aspect of our personal, interpersonal, social, or political worldview can feel like direct attacks on the core of our deeply embedded assumptive world (Harris 2020). For instance, if a legislative body passes a law that conflicts with my moral values or religious beliefs—values that inform my understanding of a just society—I might perceive this as a loss of justice that directly undermines my personal assumptive world.

4. Political Grief

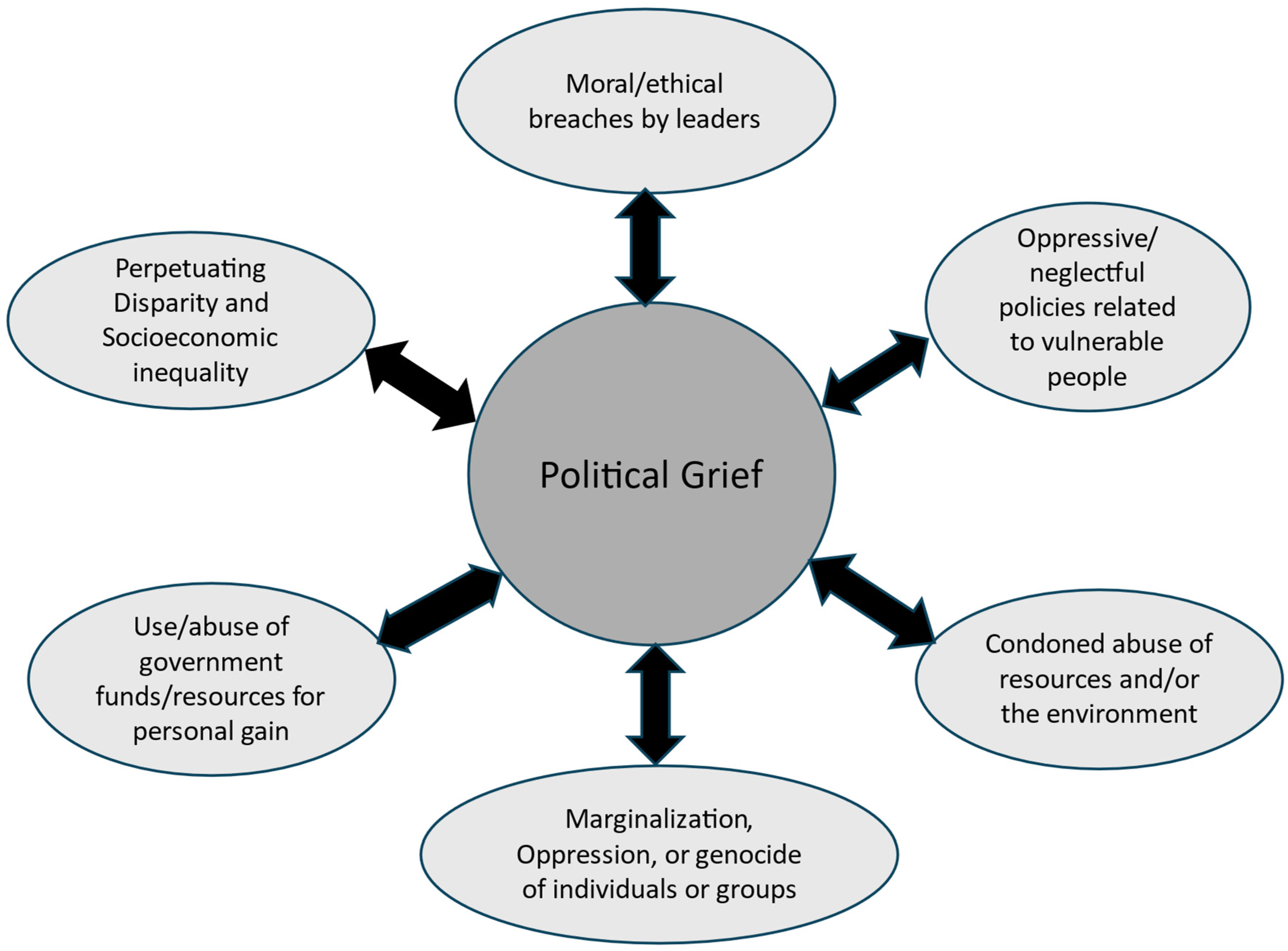

Political grief is a unique form of grief that originates from the structural and political levels. It may be experienced individually as well as collectively. A definition of political grief includes the following:

- A poignant sense of assault to the assumptive world of those who struggle with the ideology and practices of their governing bodies, and/or those who have power/authority.

- Losses experienced as a result of historical or contemporary political policies, decisions, and actions that give rise to division, oppression, and/or marginalization enacted and empowered at the sociopolitical level.

- Loss of life, safety, and/or security due to decisions and actions made by those who have power, authority, and/or influence in the sociopolitical sphere (Harris 2025).

Figure 3 identifies common sources of political grief that illustrate this definition.

Figure 3.

Examples of Sources of Political Grief.

In line with the idea that grief stems from the disruption of one’s assumptive world, political grief often manifests as a profound sense of despair arising from the loss of fundamental beliefs regarding:

- Morality, ethics, and what is generally recognized as the appropriate response to various situations.

- The expectation that elected/public officials and leaders will embody widely accepted values through their actions and the policies they promote.

- The belief in oneself and others as capable agents of positive change (Harris 2022).

Political grief is often accompanied by feelings of despair, anger, disconnection, and apathy, stemming from the impact of government policies, legislation, and their integration into social systems like healthcare and education. It is typically associated with the perceived erosion of core beliefs about justice and fairness that are central to the assumptive world. Citizens may struggle and suffer while legislative bodies remain mired in divisions that hinder progress toward improving their lives. Furthermore, intense polarization and division can exacerbate feelings of loss; an inability to accept differences or fear of negative repercussions can fracture workplaces, communities, families, and other relationships (DeGroot and Carmack 2021).

We can map political grief against the domains of the assumptive world to better understand how it occurs and the processes that lead to the grief response. Table 1 provides a sample of potential ways that the assumptive world can be shattered by events that occur at the political/structural level. Many of the losses associated with political grief revolve around the loss of the ability to feel safe, not feeling that we are heard, valued, and/or respected, and experiencing a sense of disconnection or being shut out in situations where we may have previously felt that we belonged. In political grief, there is the potential for collective grief to occur when groups of people experience these losses together.

Table 1.

Mapping the Shattered Assumptive World in Political Grief.

5. The Impact of Threat Perception

The operation of governments or leadership within structures often seems disconnected and irrelevant to the average person’s daily life. However, when policies and issues resonate more personally with individuals, the stakes become significantly higher. A pertinent example is the recent implementation of laws in the U.S. that limit access to some individuals’ ability to seek certain types of health care. In this context, political debates shift from simply supporting a party or candidate to a deeper anxiety about protecting one’s lifestyle, values, and identity (DeGroot and Carmack 2021). Family discussions can become intensely charged and stressful. Friendships may fracture over differing voting choices. Unfiltered (and often unmonitored) social media interactions can manipulate perceptions, fostering an atmosphere of fear and defensiveness. Those who disagree are often viewed as ‘the other’, creating an ‘us’ versus ‘them’ mentality. This polarization is a painful consequence of people feeling threatened, leading to divisions and the marginalization of anyone perceived as different (Alorainy et al. 2019).

The results of the 2024 election have shown a movement in the United States toward more radically conservative leanings and, in some instances, candidates with extreme right-wing views. This was also an election that favored Donald Trump, who presents himself as a person “for the people”, a true populist leader whose appeal crosses many groups that would appear to be opposed to each other on the surface. News outlets, social media sites, and even TikTok video clips provided much conjecture and analysis of the results of this election. In December, Merriam-Webster announced that its word of the year for 2024 was polarization (Merriam-Webster 2024). Indeed, the country is deeply divided. In the past when elections were held, most elected candidates may have represented more conservative (Republican) or more liberal (Democrat) views. Still, all typically ended up just to the right or left of the center on most issues. But certainly, that is not what occurs now. How did this happen?

Exposure to Threat

Several scholars offer a framework for understanding how feeling a sense of threat (which could also be interpreted as a challenge to our assumptive world) results in specific behaviors that attempt to mitigate the threat or create a stronger sense of safety. These behaviors may help to explain how we arrived at a place where differences at many levels cannot be tolerated.

Terror Management Theory. One explanation for the current situation may be found in the core tenets of Terror Management Theory (TMT), a theory that is supported by substantial empirical evidence (Pyszczynski et al. 2015). TMT purports that exposure to the awareness of death and scenarios that heighten a sense of threat produce potentially paralyzing existential anxiety that humans “manage” by more firmly seeking refuge in culture and religion. Meeting cultural/religious standards for appropriate conduct and the sense of belonging to a group leads to the perception that one is a person of value in a world of meaning, buffering anxiety in the present and increasing the prospect of immortality in the future, thus allaying fears about death. TMT posits that people identify with religion in order to control anxiety, protect against threats, bond with fellow members of faith communities, and achieve immortality (Vail et al. 2019). The rise of extremist religious groups can be seen as a reaction to various threats, whether these be viewed as personal, familial, communal, and/or political (Alparslan and Kuşdil 2024).

One of the distinctly human forms of anxiety relates to death anxiety. All major religions address this anxiety through the teaching of various versions of the immortality of the person. Literal immortality includes the concept of heaven, the afterlife, reincarnation, resurrection, and the idea that some aspects of human existence are indestructible, which is central to most religions. Symbolic immortality can be obtained by having children, amassing great fortunes, producing great works of art or science, or being a member of a great and enduring tribe or nation. People are, therefore, highly motivated to maintain faith in their cultural and religious worldviews as a defense against existential threats and dread (Solomon 2020).

Terror Management Theory suggests that when individuals feel threatened—what the authors refer to as mortality salience—they tend to seek comfort in cultural/religious traditions that provide a sense of safety and reduce vulnerability by their identification with something larger than themselves. This often leads to a preference for those with similar appearances, religious beliefs, cultural norms, or even historical backgrounds. People will often retreat to familiar environments and gravitate toward those who mirror their cultural or religious values, as these connections offer feelings of safety and protection. The downside of this tendency is that it can readily foster a dichotomous ‘us’ versus ‘them’ mentality, where allegiance to ‘us’ inherently positions individuals against those deemed ‘not us’ (Hobfoll 2019).

Biopsychosocial Approach. Paul Gilbert (2014) describes how our brains have evolved in ways to support social processing and emotion regulation linked to social roles, such as status, belonging, affiliation, cooperation, and caring. Our relationships and the need to belong are intricately tied to our responses in social situations. Emotions serve underlying motives, with the three dominant motives being harm avoidance (threat system), resource seeking (drive system), and rest, digest, and repair (soothe system). His description of the threat system is of most interest to our discussion.

According to Gilbert, when activated, the threat system launches to drive us to seek safety. The feelings that are evoked when this system is activated include anger, anxiety, and disgust, all of which quickly grab our attention to help us focus on the threat and protect ourselves (Gilbert 2014). Threat appraisal is a subjective process for each individual; however, when the threat system is engaged, there is a preprogrammed response where we lose the ability to think expansively and inclusively. When the zebra is running from a lion, it does not have time to stop and consider the meaning of life! The threat system makes us singularly focused on finding safe people and places; similar to the response to threat as described in TMT, Gilbert’s biopsychosocial model indicates that activation of the threat system makes us want to be with others who are like us, who share our same worldviews and beliefs, and who will help us to feel soothed and safe. Both of these theories have extensive empirical backing; the instinctual response to threat is protective in nature, but it also has the potential to lead to rigid, black-and-white, exclusionary thinking that can easily become entrenched.

6. Sources of Threat and Their Impact

The discussion of threat is important because losses of all types can shatter our assumptive world, activating our threat system. The activated threat system leads to the mechanism that underscores political grief: The sense of ‘us’ versus ‘them’ that occurs alongside black-and-white thinking and the resulting polarization and inability to work together for the best interests of our common humanity. It is impossible to consider a person from ‘the other side’ as a fellow human being if you believe that their presence is a threat to your existence, including what you hold dear and value the most in life. In this next section, we will explore how specific threats contribute to the current sociopolitical environment and the grief it perpetuates. Table 2 provides a visual representation of some of the primary threats driving current sociopolitical movements that ultimately set the stage for the current political milieu.

Table 2.

Threats Driving Current Social and Political Movements in Western Industrial Countries.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is not included as an active threat at this time; however, it should be stated that the catastrophic death and non-death losses that were associated with the pandemic continue as an undercurrent of vulnerability that most people in Western industrialized countries could not have fathomed prior. The pandemic highlighted not just physical vulnerability due to the threat of death and disease but also the resulting vulnerability related to ongoing issues with supply chain shortages, inflation, and strains on the healthcare systems in countries around the world.

6.1. Cultural Backlash and Displacement

In an attempt to explain the rise of populism in Western industrialized countries, Norris and Inglehart (2019) put forward the cultural backlash theory, which states that the current climate of political polarization can be explained as a reaction against progressive cultural change. After the end of the Second World War, there was an increasing sense of security and growth, fostering support for progressive movements such as environmental protection, civil rights, gender equality, and greater acceptance of diverse lifestyles, religions, and cultures. It has been argued that, particularly across older generations, among white men, and more commonly in those with less education, a sense of moral and fiscal decline is associated with the rise of progressive values. These groups may feel displaced by the loss of familiar traditional norms; as a result, this perceived loss tends to create a group of supporters that label these changes as negative and ‘morally wrong’, often citing the need to return to traditional values.

The spread of progressive values has also stimulated a cultural backlash among people who feel threatened by these social changes. These groups resent being told that the traditional values and views that formed their basic understandings of the world are now ‘politically incorrect’, leading to a change in their status from the mainstream in previous generations to being scrutinized and suspect for these same values today. We are currently seeing a movement in many countries rescinding legislation that upheld rights for the LGBTIA+ community, as well as other groups (such as racial, ethnic, and religious minorities) that previously occupied marginalized positions in society. The current backlash favors groups that are predominantly white, Christian, and heterosexual.

Despite the fact that the foundation of the U.S. democracy is based upon the separation of church and state, Christian nationalism has been growing as a powerful force, where extreme conservative Christian beliefs are infiltrating structures at all levels of government, resulting in laws that deny the pluralistic foundation of the Constitution (Whitehead and Perry 2020). Some school boards are now requiring students to read the Bible, to have copies of the Ten Commandments posted in classrooms (Ortiz 2024), and to remove any material that challenges the core beliefs (and thus the power) of this movement (Tetterton 2025). Many Christian nationalists talk about “taking back the country” or returning the country to a previous place in history where they had considerable respect and power before decisions and laws that were passed by the more liberal leadership took their privilege away. These forms of religiously oriented movements are actually fueling the destruction of pluralistic society and causing grief for many people. It is ironic that this form of extreme religious adherence is often fueled by loss—of status and cultural significance.

In summary, as a result of the post-modern rise of progressive policies and attitudes, those whose assumptive world was based upon more traditional, conservative values experienced a profound sense of loss, displacement, and grief over the upending of their view of the world that once provided a sense of safety and security in a known environment. On the other side are those who felt supported in their worldview by the movement toward widespread acceptance of diversity, gender equality, and civil rights over the past few decades now grieve the loss of these gains as exemplified by the election of individuals whose platforms include ‘traditional’ values that will return them back to the outgroup and a marginalized identity once again.

We have witnessed a surge in racism, antisemitism, and Islamophobia, accompanied by a rise in intolerance and violence linked to increasing protectionist and nationalistic sentiments in many Western developed nations. This polarizing rhetoric leads to a heightened sense of vigilance, limiting openness to diversity because embracing different perspectives diverts energy from the self-protective stance that alleviates anxiety (Solomon 2020). For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, many Asian individuals who resided in Western countries faced prejudice and ostracization from social groups they had previously belonged to, largely due to their perceived association with the virus’s origins (Huang et al. 2023).

6.2. Economic Insecurity and Inequity

Significant economic inequality chimes with the populist credo that ‘the people’ are pitted against a self-serving and, most likely, corrupt, ‘elite’ who are in positions of power. Most populists portray extreme inequality as evidence that the political establishment has lost democratic legitimacy (O’Connor 2017). Economic stress often fuels right-wing populism by creating an environment of uncertainty and fear, leading individuals to seek out simplistic solutions and strong authoritarian leadership (Torres-Vega et al. 2021). During times of economic downturn, people may feel threatened by globalization, immigration, and economic changes that they perceive as detrimental to their livelihoods. This sense of insecurity can drive voters toward populist leaders who promise to restore national pride, protect jobs, and prioritize the interests of ‘ordinary’ citizens over elites. Such leaders frequently employ rhetoric that scapegoats immigrants or foreign entities, appealing to a desire for stability and security. Consequently, economic hardship and inequity can create fertile ground for populist movements as individuals seek to reclaim their sense of agency in a rapidly changing world (Margalit 2019).

Scheiring et al. (2024) completed a systematic review and meta-analysis that showed a strong causal association between economic insecurity and populism. Colantone and Stanig (2018) argue that skepticism toward liberal values and democracy is a political manifestation of distress driven by economic insecurity. The notion of status loss creates mutually reinforcing—economic and cultural—(double devaluations) of working-class skills, values, and lifestyles that are increasingly at odds with the demands of the globalized post-industrial economy. These researchers found that overall, economic insecurity seems to predict right-wing populism.

Economic inequity in a society refers to unequal wealth, resources, and opportunities among individuals or groups. This disparity can manifest in various ways, such as differences in income, access to education, job opportunities, and healthcare. The consequences of economic inequity can be profound, leading to social unrest, reduced economic growth, and a weakened sense of community and social cohesion (Jay et al. 2019). Economic inequity can paradoxically foster a shift toward conservatism as individuals and communities seek stability and security in uncertain times. When wealth becomes concentrated in the hands of a few, many may feel disenfranchised and anxious about their economic prospects, leading them to embrace conservative ideologies that emphasize tradition, order, and responsibility. This response can manifest in a desire for policies that prioritize the preservation of established social norms and values often seen as a safeguard against perceived threats posed by rapid social change and economic instability. Conservative movements may capitalize on these feelings by promoting narratives that blame societal problems on progressive policies or cultural shifts, further solidifying support among those who feel left behind. As a result, the interplay between economic inequity and a longing for a return to perceived stability can drive individuals toward conservative social movements (Pástor and Veronesi 2021).

In the past two decades especially, there has been a rise in the growth of extreme economic inequality, represented by the disproportionate growth in the income share of the top one percent. The Gini coefficient (or “The Gini”), developed by the World Bank, is the most commonly used measure of income distribution across countries. The Gini provides an indication of the gap between those who are the wealthiest and those who are the poorest in countries around the world. High levels of income inequality can have several undesirable political and economic impacts, including slower Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth, reduced income mobility, greater household debt, political polarization, and higher poverty rates (International Monetary Fund n.d.). According to The Gini, income inequality has steadily increased in the U.S. over the past 30 years. Currently, the top 10% of Americans control nearly 70% of the wealth in the country (Statista Research Department 2024), which has implications for the stability of the society, potentially creating a steady erosion of social cohesion.

Turchin (2023) makes the argument that developed societies have, in the past, experienced significant decline based solely on the presence of income inequality, which occurs when the very rich continue to acquire more wealth while the general populace experiences stagnation or decline in their income and quality of life. This results in increasing disgruntlement and outrage by the working class, with the potential for either a correction that restores social stability by enhancing more equitable distribution of wealth, such as what occurred with FDR’s New Deal in the aftermath of the Great Depression or the opposite result of the rise of populist leaders, who eventually divert more wealth to those already rich, leading to further oppression and decline of those with lesser means. This latter outcome eventually leads to the disintegration of the social fabric of the country. The current situation in the United States is demonstrating a rapid and precarious trend toward this possibility.

6.3. Rise of Use of Social Media

The rise of social media has been linked to an increased sense of personal threat and anxiety among many users, as these platforms often amplify exposure to distressing news, bullying, rude comments, and unfiltered images and content (Thorisdottir et al. 2020). Additionally, social media algorithms prioritize sensational content, further intensifying feelings of threat and urgency. This phenomenon is exacerbated by online interactions that polarize opinions and foster hostility, making individuals feel more isolated and threatened within their own communities (Rao and Kalyani 2022). Consequently, while social media serves as a platform for connection and expression, it can also contribute to a pervasive sense of personal danger and insecurity. Users may feel a heightened sense of vulnerability as they witness real-time accounts of crises and injustices, often with very personally charged narratives. This can lead to a perception that their safety or values are under attack.

It is concerning that social media outlets are the primary sources of information for younger people (Nielsen et al. 2023). These sources can be highly problematic for their emotive content, lack of context or background information, and nonadherence to ethical codes of journalistic fact-checking and accuracy. Recently, major social media platforms such as X and Facebook indicated that they will, in fact, no longer engage in fact-checking the content that is posted on their sites (Gibson 2025). In a 2024 survey conducted by the Pew Research Center, more than half of U.S. adults (54 percent) claim they get a good portion of their news from social media, with roughly one-third of Americans indicating that their most common source for news is either Facebook or YouTube, with Instagram, TikTok, and X coming in closely tied after that (Pew Research Center 2024). People’s sense of vulnerability is amplified by the constant influx of graphic content from social media. The widespread use of unmonitored and unfiltered social media sites also increases feelings of threat from others who attack, slander, and post outright false and/or abusive statements with impunity about specific individuals and groups (Perloff 2016).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the concept of doomscrolling emerged, describing the excessive consumption of short videos or social media content for an excessive period of time without stopping (Leskin 2020). This activity is characterized by compulsive browsing on social media newsfeeds with an obsessive focus on negative news and events. Rodrigues (2022) described it as negative newsfeed binging. Doomscrolling can feel like a strangely fulfilling way of feeling in control in a world that feels so out of control. There is a sense of empowerment and safety that we experience when we enhance our knowledge or engage the curiosity of our minds. However, studies have shown that doom-scrolling has a negative impact on mental health, triggering and worsening mental and neurological health across users of all ages (George et al. 2024; Leloudas and de Wit 2024; Shabahang et al. 2023).

In an attempt to limit the onslaught of negativity and activating content from social media (which can be interpreted as a form of threat management), many individuals limit their social circles and curate their news/social media feeds to align with their ideological and religious beliefs, avoiding exposing themselves to opposing viewpoints and any potential for constructive dialogue. The result is that people tend to live in silos populated by individuals who are like-minded and are not pressed to think critically about current events. One study revealed that one in six Americans ceased communicating with a family member or close friend over political disagreements (DeGroot and Carmack 2021). These same researchers later wrote about their experience of having death threats called into their homes and places of work by Trump supporters after they wrote about the 2016 U.S. election (DeGroot and Carmack 2020). This erosion of relationships, respectful democratic discourse, and shared humanity has significant emotional repercussions, often manifesting as anger, frustration, and negative labeling about others, with a toll on relationships and the ability to engage in constructive discussions and normal conversations.

6.4. Unchecked Bias in News Media Outlets

In recent years, the landscape of news media has undergone a significant transformation, shifting from a focus on factual reporting to an emphasis on sensationalism. This change has been driven largely by the need for media outlets to attract viewers and generate revenue in an increasingly competitive environment where news is made available around the clock, every day of the year. As traditional advertising models have evolved, many news organizations have adopted clickbait strategies prioritizing eye-catching headlines and emotionally charged narratives over objective reporting. This trend not only influences how stories are presented but also shapes public perception, often blurring the line between informative journalism and entertainment (Watts et al. 2021). Consequently, the quest for profit has led to a media ecosystem where sensational accounts often overshadow the critical analysis of events, raising important questions about the integrity of news reporting in the modern age (Jones 2009).

Algorithms based on an individual’s online activity tend to push readers to content that is more sensational, negative, and controversial (George et al. 2024). The result is often highly emotionally laden and predominantly negative reporting that assaults us 24/7. The constant stream of information that is often biased and exaggerated, including reports of violence, political turmoil, and social unrest, can create an environment of heightened anxiety and fear. Much of what is shown elicits fear and a heightened sense of threat, creating unease and increased feelings of defensiveness and intolerance.

6.5. Environmental Crisis

It is impossible to ignore the impact of the changing climate on the Earth. This past year (2024) was the hottest on record (UNEP 2024). Massive wildfires destroyed large swaths around the globe. One million of the world’s estimated eight million species of plants and animals are threatened with extinction, and 75 percent of the Earth’s land surface has been significantly altered by human actions, including 85 percent of wetland areas (UNEP 2024). Severe storms and unusual weather patterns brought flooding and damage to some places, while severe draught and unprecedented heat waves profoundly affected other areas. In the recent COP29 meeting, world leaders came together and acknowledged that the changes we see now directly result from the extensive use of fossil fuels (UNFCCC 2024). Antonio Guterres, the Secretary General of the United Nations, stated “The era of global warming has ended; the era of global boiling has arrived” (United Nations 2023).

Beyond providing news and information, it is assumed that the intent in showing images of habitat destruction, animals dying and going extinct, and massive climate disasters is to help motivate people to make significant changes to their use of fossil fuels to literally save the planet. However, exposure to these images not only increases the sense of anxiety and inevitable doom but can also result in behavior that is antithetical to this intention. O’Neil and Nicholson-Cole (2009) found that when people are overwhelmed by images related to climate change, they often feel a sense of paralysis, unable to engage in a meaningful response to initiate action to address the issues. Howell (2013) found that if people felt that their actions would not result in some element of positive change, they tended to do nothing. Research by Clark and Adams (2023) found that exposure to images of habitat destruction or devastation from climate-related causes increased feelings of threat, even when those images were not directly relevant to the viewer. The more people were exposed to images of environmental destruction, the higher their sense of anxiety and the less likely they were to respond in constructive ways.

6.6. Increasing Violence Around the World

It comes as no surprise that we are living in a world where there is widespread violence and the threat of war escalating on a global level. According to the 2024 Global Peace Index, there were 92 countries engaged in a conflict beyond their borders, with the internationalization of these conflicts creating complications for negotiating processes for lasting peace, leading to the probability of prolonged conflicts (Institute for Economics and Peace 2024). This increase in violence and war in several places around the world remains profoundly troubling, characterized by a complex interplay of geopolitical tensions, civil conflicts, and the pervasive threat of terrorism. Various regions around the world, including Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and parts of Africa, continue to experience intense hostilities fueled by longstanding grievances, religious differences, resource competition, and ideological divides.

The impact of these conflicts is exacerbated by humanitarian crises, leading to significant displacement and suffering among civilian populations. Meanwhile, the rise of new technologies in warfare and the shifting dynamics of international relations further complicate efforts to achieve lasting peace. This multifaceted state of violence not only undermines global stability but also poses significant challenges to international diplomacy and humanitarian efforts. If people were not already feeling a sense of heightened threat due to what has already been described in this article, they most certainly cannot ignore the current state of the world. Russian President Vladimir Putin has, on several occasions, threatened to use nuclear weapons in his campaign to control Ukraine (Aggarwal 2024). The Middle East is a powder keg of hostilities, further exacerbated by some of the governments and the terrorist networks that reside in these areas.

7. Discussion

In the context of difficult situations, the well-known humanistic psychiatrist Irvin Yalom expands upon Sarte’s statement that “We are condemned to freedom” (Yalom 2001, p. 137). There is a lot to unpack in this statement, but the application to the subject of political grief is poignant. Although the freedom to choose those who are in positions of governmental power and authority is the foundation of Western democracies, the choices that are made will be a reflection of the social milieu and the many influences that affect these choices. We are also free to obtain information from unmonitored and unchecked sources. We have the freedom to post misinformation and slanderous comments on social media about pretty much anyone in the world without meaningful consequences.

The overarching concern is that prolonged exposure to negativity, polarizing rhetoric about others, biased news reporting, and potentially traumatic images that can be found online can make people feel anxious, stressed, fearful, depressed, and isolated. In other words, this type of exposure regularly activates our threat systems, creating a vicious circle of threat response as described by Terror Management researchers. Feeling a sense of threat makes us revert to black-and-white thinking, which perpetuates polarization between individuals and groups, and an inability to identify our common humanity with those who we perceive as different from us. We are essentially fueling the very causes of the grief that we are experiencing.

7.1. Constructively Approaching Political Grief

I make the case here that the predominant underpinnings of political grief stem from many sources. Still, there is a common thread of increased perception of threat that sets certain patterns of human behavior in motion, leading to the grief that results from the shredding of our social fabric and the destruction of an assumptive world that once provided us with stability and coherence. Thus, in the next section, I will highlight possible ways that we might be able to counter the negative impact of these threats and, in turn, constructively approach political grief.

7.2. Common Humanity

According to Terror Management Theory, the primary response to threat is to seek safety by identifying with cultural and religious belief systems that help us to feel a sense of being a part of something that is larger than ourselves (Solomon 2020). In this identification, we gravitate toward people who share our worldview. While recognizing that this is an essential primary response meant to alleviate our anxiety, over the long term, this reaction leads to the perception that those who are not in our ‘safe’ group are potential threats to defend against. Many Christians take the view that not only is the Christian religion the only true religion, but that their particular sect or denomination is right to the exclusion of all others. In addition, many Christians believe that Muslims want to destroy all Western democracies, and many Muslims believe that Christians want to destroy Islam (Koopmans 2015). Jewish individuals carry the legacy of the Holocaust and keenly remember being singled out and murdered for their religion. This stance of rigidly adhering to a ‘safe’ group eventually leads to othering those who are not in the same group, and someone who does not agree with our perspective is seen as ‘the other’ in an ‘us versus them’ dichotomy. The polarization that is present in societies where this dynamic is at play is a painful outgrowth of feeling threatened, with the resulting divisions and ‘othering’ directed to anyone different from oneself (Alorainy et al. 2019). Udah (2019) describes othering as an imposed state of difference, which relies on binary, dualistic thinking, making divisions into two opposing categories such as ‘I’ versus ‘you’, ‘we’ versus ‘them’, or ‘self’ versus ‘other’. It is often based on differences in terms of race, skin color, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, language, name, dress, religion, or other differential characteristics. As such, the notion of otherness is important for understanding how societies categorize and form identities.

A Pew research study that explored how Democrats and Republicans in the U.S. view each other demonstrated that each group felt the other was immoral, less patriotic, and completely closed-minded. Republicans were more likely to describe Democrats as lazy, and Democrats were more prone to describe Republicans as closed-minded. Republicans often referred to Democrats as ‘socialists’, and Democrats referred to Republicans as ‘fascists’ (Pew Research Center 2019). This study also reported that since 2016, both Democrats and Republicans felt they had very little in common with opposing party members, stating that even with politics aside, they do not have the same values or goals. There are many studies indicating that more Americans now use their political party affiliation as a source of meaning and social identity, with these identities linked to how they engage in leisure activities, what they buy, the movies they like, and even their basic sense of right and wrong (DellaPosta et al. 2015; Hiaeshutter-Rice et al. 2023). Most concerning are the views expressed by a large segment of Americans that they would take pleasure in the thought of their political opponents being harmed (Smith and Jilani 2024). With this level of polarization, how is a society supposed to function?

Several movements are actively attempting to counter the growing polarization and sense of othering that is currently prevalent in many Western-oriented countries. One example is the growth of interest in the study of compassion, grounded in the Buddhist approach to the relief of suffering. The concept of compassion goes beyond empathy and prosocial behaviors (such as kindness and sympathy) to focus on intention and motivation. The ability to acknowledge suffering, turn toward it, and actively seek to relieve it functions as a buffer to divisive rhetoric that perpetuates the suffering of many. Of interest is the growing amount of empirical evidence demonstrating that training in compassion provides a sense of sustainable response-ability in the midst of very distressing and difficult situations (Halifax 2013; Ho and Harris 2022; Klimecki et al. 2014). Gilbert (2014) stresses that it is not necessary to like someone in order to enact your intention for compassion for that person. The key is in the cultivation of this intention and motivation to relieve suffering, whether there is affinity toward or agreement with the recipient.

One response to how people have become polarized was the creation of the Berkeley Greater Good Science Center’s work on Bridging Differences (Greater Good Science Center n.d.). The Center has produced numerous research-based articles, videos, podcast episodes, a Playbook, an online course, and other resources attempting to highlight the skills and social conditions that might help reduce polarization and promote more constructive dialogue. The resources from The Center focus on the following:

- Helping people to recognize, understand, and guard against the negative impact of personal biases and prejudices

- Finding ways to communicate that foster understanding and deeper connection rather than exacerbating divides

- Ways to find commonalities and connection with people who might seem different from you

- How to set up and support positive interactions between members of different groups who might be at odds with one another

- How to foster and support positive interactions between members of different groups who might be at odds with one another (BerkeleyX n.d.)

The Center holds a unique place in the U.S. as a non-partisan organization focusing on identifying and acknowledging the common humanity that binds us together rather than the polarizing differences currently tearing people apart. Being able to acknowledge our commonalities is incredibly difficult during a time when our sense of threat (and indignation) is high. By attempting to direct resources to engage in activities that help reduce the sense of threat, it is hoped that individuals (and groups) may more readily be able to stop participating in the activities that perpetuate differences and the sense of threat accompanying them.

Another relevant area of practice that underscores our common humanity is respect and value for each other as we communicate in social media and online communities. It is important to choose how we express ourselves in ways that foster bridging rather than further fracturing. When your threat system is activated by an online post or thread, allow yourself the time to walk away from the conversation and to be reminded of your intention. A compassion-based approach to interactions with others includes the motivation to prevent suffering and to relieve suffering when possible, and we must include ourselves in this intention (Harris 2025). Consider the ways that your online communication aligns with this intention. Refuse to gaslight, respond with inflammatory responses, or use language that could be interpreted as threatening, degrading, or belittling.

7.3. Conscious Capitalism and Practices of Gratitude

As described earlier, some of the basis for the activation of our threat centers is related to economic insecurity and inequity. The anxiety surrounding the difficulties that many have right now in finding affordable housing, being able to buy their groceries and other necessities, and the overall sense of precarity in day-to-day living makes people want to pull inward, isolate, and protect themselves (Bierman et al. 2024). The increasing divide between those with wealth and those who live from paycheck to paycheck also fosters a growing sense of inequity that spills over into civil unrest and further activates the sense of threat that is present. Capitalism, especially as it has been enacted in the U.S., locks people into a system that pushes the perpetual accumulation of goods and profit rather than focusing on satisfying needs or contributing to the common good. A growing sense of anxiety about financial stability creates a mentality that is focused on ‘not enough’. This is also a threat-based stance, further amplifying the underlying polarization and othering dynamic.

To reflect on how capitalism might have a negative effect on the social fabric is difficult in Western industrialized countries because so many of the tenets of capitalism are deeply woven into foundational aspects of these societies. However, there has recently been a countering movement toward conscious capitalism, which seeks to buffer against the negative effects of consumer capitalism. Conscious capitalism is an evolving business philosophy that seeks to redefine the purpose of capitalism by prioritizing ethical practices, social responsibility, and environmental sustainability alongside profit generation (Mackey and Sisodia 2014). This approach recognizes that traditional capitalism can often lead to negative consequences, including exploitation of workers, environmental degradation, and widening social inequalities. By fostering a more holistic view of business, conscious capitalism encourages companies to operate with a greater awareness of their impact on all stakeholders—employees, customers, communities, and the planet. This paradigm shift not only aims to reduce harm but also promotes long-term success by aligning business practices with the values and expectations of a more socially conscious consumer base.

Drawing on Buddhist teachings, Macy and Johnstone (2022) discuss the practice of gratitude as a powerful antidote to the capitalistic mindset that perpetuates a constant feeling of inadequacy and an insatiable desire for more wealth and material goods. These authors suggest that in a society where success is often measured by material accumulation and financial status, cultivating gratitude shifts the focus from what we lack to what we already have. Macy (2006) suggests that applying Buddhist practices that focus on gratitude, presence, being able to turn toward suffering, and the ability to respond through principled action can foster connection and healing in a society ravaged by years of materialism, oppression, abuse, and othering. She suggests that by appreciating the abundance in our lives—whether it be relationships, experiences, or simple joys—a sense of contentment can be cultivated that counters the relentless drive to pursue wealth and the scarcity mentality that continually keeps our threat systems activated. This mindset enhances personal well-being and encourages a more compassionate and interconnected community, challenging the notion that self-worth is tied solely to financial success.

7.4. Individual Reflection; Principled Social Action

Political grief is often accompanied by very strong emotions, including anger over perceived injustice, and disgust for leaders who use their position for personal gain or to fulfill their personal vendettas, including retaliation on their enemies. For many who experience this type of grief, there is no middle ground; the violations of human decency are obvious, and the reactions to what people feel in response are a defense against these feelings of violation. One family member recoils in horror as another family member expresses alignment with a leader or group that they experience as personally egregious. Groups that are rendered more vulnerable or at risk due to political movements and policies being enacted have no recourse for their voices to be heard or their rights reinstated. Many of these political movements are aligned with religious teachings in ways that cloud the real underlying issues, using religion as a means to wield power rather than alleviate suffering and work for the good of all.

The term moral outrage describes the anger provoked by a real (or perceived) violation of an ethical standard such as fairness, respect, or beneficence. Ungrounded moral outrage can be disturbing and detrimental, and it is often intensified by a sense of moral sanction. Rushton (2013, 2018) discusses the concept of principled moral outrage, where there is an ability to respond to the violation with a sense of balance and compassion rather than from the hugely negative reactive energy that is felt. Principled moral outrage is a powerful response to political grief, manifesting when individuals confront injustices that challenge their core values and ethical beliefs. This form of outrage is not merely a reaction to personal loss or disappointment; rather, it is driven by a deep-seated commitment to social justice and the well-being of others.

When political decisions result in suffering, inequality, or oppression, those who experience grief may channel their pain into activism, advocating for change and holding those in power accountable. The moral indignation associated with these feelings of violation serves as a catalyst for collective action, uniting people across diverse backgrounds to demand a more equitable society. However, discernment, curious inquiry, and humility are essential to determine the right and best response to these situations. As examples, we can consider the ways that leaders like Martin Luther King or Gandhi responded to injustice, racism, and oppression during their lives. The ability to respond to situations of moral outrage with intentionality, reflexivity (instead of reactivity), and respect forms the basis of an intentioned, principled response. A person who is acting from principled moral outrage can make important distinctions, including the ability to accurately assess the situation and respond from recognition of the inherent value of our shared humanity. Ultimately, principled moral outrage has the potential to transform grief into a force for positive change, fostering resilience and hope in the face of adversity. The key to developing principled responses is the ability to take the time to reflect and respond constructively rather than simply reacting to the strong emotions that are present.

8. Summary

Political grief is a unique form of grief that occurs in response to events, decisions, and policies that originate from social and political structures. Although structural in its origin, the sense of loss that occurs can feel profoundly personal due to the impact on the individual’s assumptive world. When the assumptive world is shattered by a significant loss experience that originates from a structural/political level, a sense of threat and unease occurs, leading to specific behaviors that further intensify the impact of political grief. These behaviors typically include the desire to align with others who share similar values, beliefs, and world views to feel safe and comforted, along with the sense that there is strength in numbers. However, there is the potential for the safe group identity to become siloed into an ‘us versus them’ mentality in opposition to those who are different, which can result in othering as well as fractured relationships with those who are different in their views, beliefs, race, and/or ethnicity. There are many sources of threat in our current world, and the rapid dissemination of unchecked information and unfiltered images across all forms of media intensifies how these threats are perceived and personalized. As a result, the political grief that is experienced becomes fuel for movements that favor protectionism, absolutism, and the rise of populist leaders that do not value the ideals of the post-modern movements toward greater equity, appreciation of diversity, and inclusion of all voices within society.

There is an irony when exploring the role of religion in political grief, as affiliation with some forms of religious ideation can make people feel more secure and connected; however, this same religious affiliation can perpetuate division, othering, and oppression of non-aligned groups. Because religious beliefs and ideology can function as a defense against feelings of threat and vulnerability, people gravitate toward specific forms of religion to feel more powerful and in control. However, this form of religious affiliation thrives on fear motivation to enact agendas and laws that likely have nothing to do with the original teachings and doctrine of that religion. People may feel more protected and stronger in their alignment with religiously branded nationalism, but the result is increased division and harm to those not part of the ‘in’ group. There is much grief associated with these movements in several countries, but most particularly in the U.S., where Whitehead and Perry (2020) describe Christian Nationalism as “Christianity co-opted in the service of ethno-national power” (p. xix). The ability to acknowledge our grief and find ways to focus on our common humanity amid such difficulties provides us with an opportunity to consciously choose our responses rather than react out of our instinct for self-preservation. Becoming more conscious in our use of social media to ensure that we do not expose ourselves to more material that will activate our threat systems further and being judicious in how we use social media to share our thoughts, feelings, and opinions is also important to help mend the tattered social fabric that we now see in so many places. Finally, advocacy and activism have always been important ways to bring about social change; what is most important is that the activities are chosen from a place of clarity and ethical resolve rather than out of anger, a desire for control, and a need to retaliate for our pain. Recognizing political grief helps us to acknowledge that there is a wound that needs tending. It is our choice to find ways to enable this wound to heal rather than allow it to fester, become infected, and cause more harm to us and others in the process.

Funding

This article and the research supporting it received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 | Robert is a fictitious person, whose identity is drawn from an amalgamation of several individuals. |

References

- Aggarwal, M. 2024. Putin Issues New Nuclear Doctrine in Warning to the West over Ukraine. NBC News, November 19. Available online: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/putin-nuclear-doctrine-us-ukraine-strike-russia-war-west-rcna180740 (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Alorainy, Wafa, Pete Burnap, Han Liu, and Matthew L. Williams. 2019. The Enemy Among Us: Detecting Cyber Hate Speech with Threats-Based Othering Language Embeddings. ACM Transactions on the Web 3: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alparslan, Kenan, and M. Ersin Kuşdil. 2024. A Review of Research on the Role of Different Types of Religiosity in Terror Management. Psikiyatride Güncel Yaklaşımlar 16: 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attig, Thomas. 2001. Relearning the World: Making and Finding Meanings. In Meaning Reconstruction & the Experience of Loss. Edited by Robert Neimeyer. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- BerkeleyX. n.d. BerkeleyX: Bridging Differences. Available online: https://www.edx.org/learn/sociology/university-of-california-berkeley-bridging-differences (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Bierman, Alex, Laura Upenieks, and Yeonjung Lee. 2024. Perceptions of Increases in Cost of Living and Psychological Distress among Older Adults. Journal of Aging and Health 6: 414–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, Kylie, and Aubrie Adams. 2023. Altering attitudes on climate change: Testing the effect of time orientation and motivation framing. CSU Journal of Sustainability and Climate Change 3: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantone, Ilaria, and Piero Stanig. 2018. The Economic Determinants of the ‘Cultural Backlash’: Globalization and Attitudes in Western Europe. BAFFI CAREFIN Centre Research Paper No. 2018-91. Milan: Bocconi University. [Google Scholar]

- DeGroot, Jocelyn M., and Heather J. Carmack. 2020. Unexpected Negative Participant Responses and Researcher Safety: ‘Fuck Your Survey and Your Safe Space, Trigger Warning Bullshit’. Journal of Communication Inquiry 4: 354–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGroot, Jocelyn M., and Heather J. Carmack. 2021. Loss, Meaning-Making, and Coping after the 2016 Presidential Election. Illness, Crisis & Loss 29: 159–81. [Google Scholar]

- DellaPosta, Daniel, Yi Shi, and Mark Macy. 2015. Why Do Liberals Drink Lattes? American Journal of Sociology 120: 1473–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doka, Kenneth J. 2020. Disenfranchised Grief and Non-Death Losses. In Non-Death Loss and Grief: Context and Clinical Implications. Edited by D. Harris. New York: Routledge, pp. 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger, Naomi I. 2012. The Pain of Social Disconnection: Examining the Shared Neural Underpinnings of Physical and Social Pain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 13: 421–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A. Shaji, AS Hovan George, T. Baskar, and M. M. Karthikeyan. 2024. Reclaiming Our Minds: Mitigating the Negative Impacts of Excessive Doomscrolling. Partners Universal Multidisciplinary Research Journal 1: 17–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, Kate. 2025. Meta to End Fact-Checking, Replacing It with Community-Driven System Akin to Elon Musk’s X. CBS News, January 8. Available online: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/meta-facebook-instagram-fact-checking-mark-zuckerberg/ (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Gilbert, Paul. 2014. The Origins and Nature of Compassion Focused Therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 53: 6–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, Paul, and George Simos, eds. 2022. The Evolved Functions of Caring Connections as a Basis for Compassion. In Compassion Focused Therapy. New York: Routledge, pp. 90–121. [Google Scholar]

- Greater Good Science Center. n.d. Bridging Differences. Available online: https://ggsc.berkeley.edu/what_we_do/major_initiatives/bridging_differences (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Halifax, Joan. 2013. Understanding and cultivating compassion in clinical settings. The ABIDE compassion model. In Compassion: Bridging Practice and Science. Munich: Max Planck Society, pp. 209–28. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Darcy. 2020. Nondeath Loss and Grief: Laying the Foundation. In Nondeath Loss and Grief: Context and Clinical Implications. Edited by D. Harris. New York: Routledge, pp. 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Darcy. 2022. Political Grief. Illness, Crisis & Loss 30: 572–89. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Darcy. 2025. Sociopolitical Grief. Mortality, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiaeshutter-Rice, Dan, Fabian G. Neuner, and Stuart Soroka. 2023. Cued by Culture: Political Imagery and Partisan Evaluations. Political Behavior 45: 741–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Andy H. Y., and Darcy L. Harris. 2022. What Is Compassion Training? In Compassion-Based Approaches in Loss and Grief. London: Routledge, pp. 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E. 2019. Threat and the Rise of Fear Politics and Tribalism. In Stress and Anxiety: Contributions of the STAR Award Winners. Edited by P. Buchwald, K. Kaniasty, K. Moore and P. Arenas-Landgrave. Berlin: Logos, pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, Rachel A. 2013. It’s not (just)“the environment, stupid!” Values, motivations, and routes to engagement of people adopting lower-carbon lifestyles. Global Environmental Change 23: 281–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Justin T., Masha Krupenkin, David Rothschild, and Julia Lee Cunningham. 2023. The Cost of Anti-Asian Racism during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nature Human Behaviour 7: 682–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute for Economics and Peace. 2024. Global Peace Index 2024: Measuring Peace in a Complex World. June. Available online: http://visionofhumanity.org/resources (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- International Monetary Fund. n.d. Income Inequality. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/Inequality/introduction-to-inequality (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Janoff-Bulman, Ronnie. 2010. Shattered Assumptions. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Jay, Sunny, Anna Batruch, John Jetten, Clifford McGarty, and O. T. Muldoon. 2019. Economic Inequality and the Rise of Far-Right Populism: A Social Psychological Analysis. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 29: 418–28. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Amy. 2009. Losing the News: The Future of the News That Feeds Democracy. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Klass, Dennis, Phyllis R. Silverman, and Susan Nickman. 2014. Continuing Bonds: New Understandings of Grief. New York: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Klimecki, Olga M., Susanne Leiberg, Matthieu Ricard, and Tania Singer. 2014. Differential pattern of functional brain plasticity after compassion and empathy training. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 9: 873–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, Ruud. 2015. Religious fundamentalism and hostility against out-groups: A comparison of Muslims and Christians in Western Europe. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41: 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leloudas, George, and J. de Wit. 2024. Doom-Scrolling Under the Microscope: The Factors of a Recurrent Harmful Behavior and Its Impact on Online Risk Behavior, Self-Esteem, and Pessimism. Master’s thesis, Tilburg University, Tilburg, The Netherlands. Available online: https://arno.uvt.nl/show.cgi?fid=177664 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Leskin, Paige. 2020. Staying Up Late Reading Scary News? There’s a Word for That: ‘Doomscrolling’. Business Insider, April 19. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/doomscrolling-explainer-coronavirus-twitter-scary-news-late-night-reading-2020-4 (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- MacDonald, Geoff, and Mark R. Leary. 2005. Why Does Social Exclusion Hurt? The Relationship Between Social and Physical Pain. Psychological Bulletin 131: 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, John, and Raj Sisodia. 2014. Conscious Capitalism: Liberating the Heroic Spirit of Business. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- Macy, Joanna. 2006. The Work That Reconnects. Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Macy, Joanna, and Chris Johnstone. 2022. Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We’re in with Unexpected Resilience and Creative Power, rev. ed. Novato: New World Library. [Google Scholar]

- Margalit, Yotam. 2019. Economic insecurity and the causes of populism, reconsidered. Journal of Economic Perspectives 33: 152–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam-Webster. 2024. 2024 Word of the Year: Polarization. December 4. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/wordplay/word-of-the-year (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Neimeyer, Robert A. 2000. Searching for the Meaning of Meaning: Grief Therapy and the Process of Reconstruction. Death Studies 24: 541–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]