Secular “Angels”. Para-Angelic Imagery in Popular Culture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Infantilization of Angelic Iconography

…Christian theology has nearly always explained ‘the appearance’ of an angel in the same way. It is only the ignorant, says Dionysius in the fifth century, who dream that spirits are really winged men.

In the plastic arts, these symbols have steadily degenerated. Fra Angelico’s angels carry in their face and gesture the peace and authority of heaven. Later come the chubby, infantile nudes of Raphael; finally the soft, slim, girlish and consolatory angels of nineteenth-century art, shapes so feminine that they avoid being voluptuous only by their total insipidity—the frigid houris of a tea-table paradise. They are a pernicious symbol. In Scripture, the visitation of an angel is always alarming; it has to begin by saying “Fear not”. The Victorian angel looks as if it were going to say “There, there”.

3. The Americanization of Film Depictions of the Angel

Human or Angel?

- “Death makes angels of us all…

- And gives us wings

- Where we had shoulders

- Smooth as raven’s claws21”

- (Feast of Friends, Jim Morrison)

4. Sexuality and Gender of the Angel

5. Moral Ambiguity of Popular Imagery

Can an Angel Fall?

6. After the End of the World? Angels of the Apocalypse

”)—often thankful (people thank God without specifying for what specifically; in others, they give thanks for faith, for Jesus Christ, for angels, etc.); (2) provocative—for example, attributing beauty to demons (a comment on the series of beautiful, named angels), or “oh so Angels also wear clothes?”, evoking the second commandment “tu ne te feras point de représentation quelconque des choses qui sont en haut des le ciel37”; (3) perfunctory—“amen”, “Michael”, “beautiful” and “God is wonderful”; (4) questioning—“Which is my guardian?”; “Mais qui vous a dit que cet créatures ont cette forme mes frère. Arrêtez de vous faireembrouillé ainsi38.”; and (5) claiming—“if you believe in God, Jesus Christ—text affirm (AMEN) to my inbox now to receive a big blessing to pay up ur rent and bills E.T.C.” (this comment is not from the person posting the material online). Although these clips generate extensive commentary, not all viewers leave a trace of their feelings or their thoughts in the comments. The impact in popular consciousness of such AI-created narratives requires long-term and multifaceted research. It is worth remembering that AI introduced to create web content is still in the learning stage; and is burdened with many biases—gender (Walsh 2017, pp. 161–162), racial39 and cultural (Jarecka and Fortuna 2022). Is AI also burdened by religious biases? This is an interesting topic, worthy of separate studies.

”)—often thankful (people thank God without specifying for what specifically; in others, they give thanks for faith, for Jesus Christ, for angels, etc.); (2) provocative—for example, attributing beauty to demons (a comment on the series of beautiful, named angels), or “oh so Angels also wear clothes?”, evoking the second commandment “tu ne te feras point de représentation quelconque des choses qui sont en haut des le ciel37”; (3) perfunctory—“amen”, “Michael”, “beautiful” and “God is wonderful”; (4) questioning—“Which is my guardian?”; “Mais qui vous a dit que cet créatures ont cette forme mes frère. Arrêtez de vous faireembrouillé ainsi38.”; and (5) claiming—“if you believe in God, Jesus Christ—text affirm (AMEN) to my inbox now to receive a big blessing to pay up ur rent and bills E.T.C.” (this comment is not from the person posting the material online). Although these clips generate extensive commentary, not all viewers leave a trace of their feelings or their thoughts in the comments. The impact in popular consciousness of such AI-created narratives requires long-term and multifaceted research. It is worth remembering that AI introduced to create web content is still in the learning stage; and is burdened with many biases—gender (Walsh 2017, pp. 161–162), racial39 and cultural (Jarecka and Fortuna 2022). Is AI also burdened by religious biases? This is an interesting topic, worthy of separate studies.7. Conclusions: Cultural Trends as Presented by Secular Angels

- -

- In human form, they exhibit worse traits than many humans (“rogue” Teen Angel l and the vengeful angel of death in Dogma) and plunge into sensuality like Nathaniel in the film City of Angels or the debauched and hedonistic titular Michael;

- -

- They are all too eager to help people straighten out their life paths, not only realizing the essence of the problems that overwhelm people (series such as Highway to Heaven, Touch of an Angel) but sometimes forcing them to change their decisions (Highway to Heaven);

- -

- They desire to become human, which is a glorification of human everyday life (Der Himmel über Berlin/City of Angels) and a degradation of perfect heavenly existence, expressing disagreement with God’s plans.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | It is worthwhile to analyze all these topics, if only to highlight the paradoxical tendencies and opposing phenomena permeating contemporary culture: real waste versus exhortations to austerity; surplus production versus the “zero waste” ideology; virtual wealth (e.g., bitcoin and NFT collecting) versus real poverty (huge individual and national debts); and creating a desire for new gadgets versus popularizing the ideology of minimalism. However, this essay is not the appropriate medium to elaborate on these topics. Moreover, in the context of this essay, one might add observable tendencies, such as the secularization of political and social life on the one hand (Taylor 2007), and on the other, the longing for spirituality (Ammerman 2013; Chowdhury 2018), for that which grows beyond the material expression of life on Earth. Religiosity and spirituality are not defined by statistics, but rather by human needs. |

| 2 | The concept of convergence culture by Henry Jenkins is followed here, where convergense means: “the flow of content across multiple media platforms, the cooperation between multiple media industries, and the migratory behavior of media audiences who will go almost anywhere in search of the kinds of entertainment experiences they want” (Jenkins 2008, p. 2). It is not only the technological process: “Convergence does not occur through media appliances, however sophisticated they may become. Convergence occurs within the brains of individual consumers and through their social interactions with others. Each of us constructs our own personal mythology from bits and fragments of information extracted from the media flow and transformed into resources through which we make sense of our everyday lives” (ibidem: 3–4). |

| 3 | |

| 4 | The differences between religions also concern the understanding of the fall of angels, the tasks of Satan (Emberger 2022; Ryba 2018; Schatz 2008; Zarasi et al. 2015). |

| 5 | “You shall not make for yourself an image in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below. You shall not bow down to them or worship them; for I, the Lord your God, am a jealous God, punishing the children for the sin of the parents to the third and fourth generation of those who hate me, but showing love to a thousand generations of those who love me and keep my commandments”, Ex 20: 4–6 (https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Exodus%2020&version=NIV, accessed on 4 February 2025). |

| 6 | https://www.tertullian.org/fathers/areopagite_13_heavenly_hierarchy.htm, accessed on 4 February 2025. |

| 7 | A captivating example of wingless angels is Ecce Ancilla Domini! painted in 1850 by Dante Gabriel Rosetti. The painting which was not created for an ecclesiastical commission and can now be seen at the Tate Gallery in London. |

| 8 | “Angels depicted heralding the birth of Jesus in nativity scenes across the world are anatomically flawed, according to a scientist who claims they would never be able to fly” (https://www.telegraph.co.uk/topics/christmas/6860351/Angels-cant-fly-scientist-says.html, accessed on 11 February 2025). |

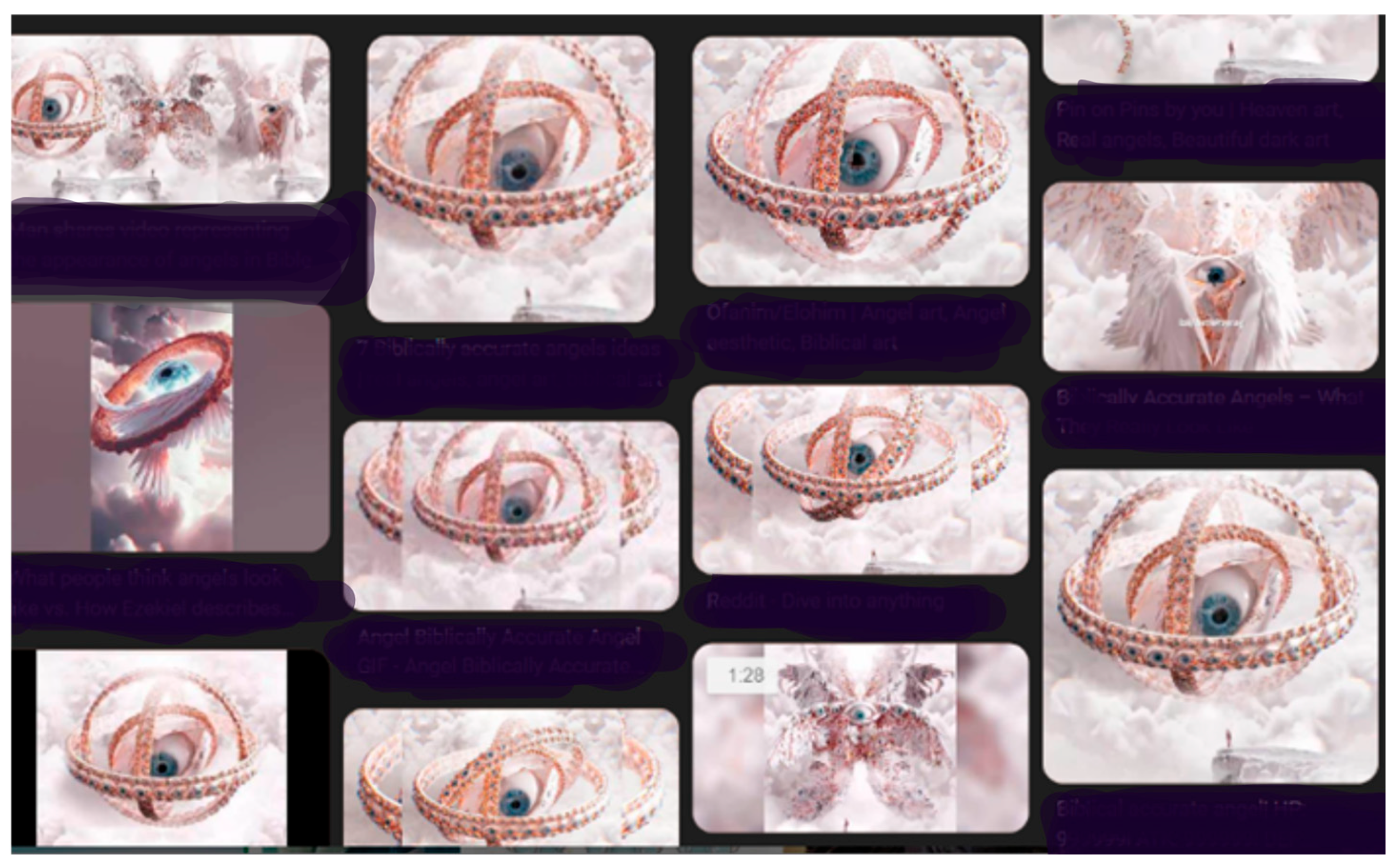

| 9 | In AI-generated clips created by artists and common Internet users presented on TikTik or Instagram, angels are powerful figures, often in armor, with huge wings, sometimes even exceeding the size of the angels themselves. The costumes here are more standardized than in historical art: one common style features —gold or white; while another one consists of white robes or armor with gold ornaments, or white with luminous elements in a chosen color, green, purple or blue. |

| 10 | Jesus Christ, who appeared to St. Francis in a vision in the form of a six-winged seraph and marked him with stigmata, is portrayed in this way. This visualization stems from the testimony of St. Francis. And, it was upheld by artists such as Giotto, Domenico Ghirlandaio and El Greco. |

| 11 | Research on this topic started more than 10 years ago and resulted in conference presentations and published article (Jarecka 2014). This essay builds upon the previous text with the use of new materials, collected after its publication. |

| 12 | It is worth mentioning some of the difficulties in web research. To estimate the interest in the web, one can use popular tools such as Google trends. In this section, one can find statistics divided between the “whole world”, continents, countries or even regions. To narrow down the results, one can use specific categories—“education”, “finances”, “garden”, “society”, “entertainment”, and “books and literature”; however, “religion” is not included. It is difficult to use this tool, as the algorithm is not adjusted to much of the important parts of human existence. Spirituality is not included either. The same problem occurs when using other search engines. Even if the Google search engine indicates 3,450,000,000 hits for the keyword “angel” in half a minute, the selection of the religious, spiritual or artistic context must be done not mechanically, but manually, using the researcher’s experience. |

| 13 | Many documentaries are available on this platform, including those on the history of angels https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xzxLDqXtlt4 (accessed on 5 January 2025 or the psychology of angels https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ErXWtdC2ZYI&t=1332s (accessed on 5 January 2025. |

| 14 | For example, in studies such as Angels by Paola Giovetti (2001), Angels. Images of Celestial Beings in Art by Ward and Steeds (2005) and Mythical Creatures and Demons. The Fantastic World of Mixed Beings by Heinz Mode (1975). Religious works, on the other hand, deal with Christian images, such as Angels in Salvation History by Rev. Marian Polak (2001). |

| 15 | This is typical of the New Age. The attractiveness of the New Age, as Rev. Witold Jedynak notes “…lies in its ability to gather elements from all religions and ages, and then transform them into a message of new strength and relevance for modern man” (Jedynak 1995, p. 4). |

| 16 | https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/5f/Durer%2C_la_grande_passione_06.jpg (accessed on 29 January 2025). |

| 17 | https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:D%C3%BCrer_-_Large_Passion_12.jpg#/media/File:D%C3%BCrer_-_Large_Passion_12.jpg (accessed on 29 January 2025). |

| 18 | The Screwtape Letters: Annotated Edition: https://www.google.pl/books/edition/The_Screwtape_Letters_Annotated_Edition/aSj_-mgwWbYC?hl=pl&gbpv=1, accessed on 10 December 2024. |

| 19 | https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Carlo_crivelli,_montefiore,_piet%C3%A0_di_londra.jpg (accessed on 5 January 2025). |

| 20 | Often, ostensibly “religious” films deal with political issues or talk about conspiracy theories linked to the Vatican, such as the documentary Angels and Demons Revealed by David McKenzie (2005), explores stories about the Illuminati, the KGB, blackmail, preparations for world war, assassination attempts on popes, etc. Similar stories are also included in the documentary Angels vs. Demons: Fact or Fiction? directed by Will Ehbrecht in 2009. The latter was made on the wave of popularity of Dan Brown’s (2001) novel Angels and Demons and the feature film inspired by it. |

| 21 | https://genius.com/Jim-morrison-a-feast-of-friends-lyrics (accesssed on 27 November 2024). |

| 22 | This idea is probably rooted in the works of Emanuel Swedenborg, who wrote that after death, the human mind “no longer thinks naturally, but spiritually […] it becomes wise like an angel, all of which confirms that the internal part of man, called his spirit, is in its essence an angel […]; and when loosed from the earthly body is equally in the human form and an angel” (1966, p. 314). |

| 23 | All pictures based on the movies or social media clips are created by the author with the usage of AI (apps available in Canva and Photoshop). |

| 24 | The Screwtape Letters: Annotated Edition: https://www.google.pl/books/edition/The_Screwtape_Letters_Annotated_Edition/aSj_-mgwWbYC?hl=pl&gbpv=1 (accessed on 10 December 2024). |

| 25 | Industriousness, perseverance, frugality, courage to take on challenges, etc., are typical qualities that enable a person to strive for success. Success itself is understood as primarily business success, cf. (Grzeszczyk 2003, pp. 38–43). In contrast, underachievement can lead to disbelief in oneself and bitterness. Paul Pearsall wrote of the toxic success syndrome, that it is “a chronic sense of inadequacy, doubt, disappointment and lack of connection” (Pearsall 2004, p. 59). These are the kinds of undeveloped states of mind that the series’ angels (in both Highway to Heaven [1984–1989] and Touched by an Angel [1994–2003]) help overcome. |

| 26 | The series’ creators also wrote: “Monica, Tess and Andrew are angels who are sent down to earth to help people who are in difficult situations. Monica is still an inexperienced angel, and Tess is her guide and teacher… [distributor’s description]”, from http://www.filmweb.pl/serial/Dotyk+anio%C5%82a-1994-93637 (accessed 10 December 2024). |

| 27 | “Satan or the devil and the other demons are fallen angels who have freely refused to serve God and his plan. Their choice against God is definitive. They try to associate man in their revolt against God” (cf. CCC 1993, p. 414). |

| 28 | Discussing American individualism, Ewa Grzeszczyk writes: “…Indeed, people who highly value individualism tend to isolate themselves from the rest of society, locking themselves in a tight circle of family and friends” (Grzeszczyk 2003, p. 37). |

| 29 | Film angels are given names. In some movies, one can identify an angel due to his biblical name (such as Michael); however, in film narratives, they are given ordinary names—Giordano, Lawrence, Monica and Tess. One can look for meanings related to history, e.g., Giordano Bruno or Monica, the mother of St. Augustine, but this is not the purpose of calling an angel by a name that can sound very anonymous, peculiar or strange—Giordano. He is one of us, perhaps a visitor from heaven, and seems like a normal, ordinary one. By contrast, in the movie Dogma, the angel of death, Loki, is named after a pagan god of destruction from Scandinavian mythology, which signals the ideological hybridity of such a character. |

| 30 | The heterogeneous colors of angelic representations are also typical of Western painting; there are no established or typical color patterns. Although, the “husband in a white robe” is an angel appearing after the resurrection, some of the angels from the history of painting wear more than just white robes. We can also find quite a few examples illustrating the symbolism associated with specific archangels. For example, in the scene painted by Lucas de Heere of Mary and Jesus with two angels (16th century), St. Archangel Michael kneels before the Mother of God in dark, graphite armor covered with a golden–red mantle, while symmetrically on the other side, Archangel Gabriel kneels in a white flowing robe with an imposed golden–green mantle. Gold is a companion color to angelic images throughout the history of painting and may form the background of the depiction, a halo or certain elements of the costume. For example, the painting Angels from the 14th century by Italian master Ridolfo Guariento depicts a host of armed angels, as warriors in soldier’s attire: golden belts, golden spears, golden epaulettes and halos, golden halves of their coats and other elements of their image, which set the tone for the whole painting, emphasizing the majesty of the holy spirits.Their armor is decorated with golden embroidery. Their wings are golden–red–black, and red complements the colors of their garments. |

| 31 | In the series “Tajemniczy śwat żydów” (The secret world of the Jews), episode Anioły w Judaizmie (“Angels in Judaism”), A Polish Chassidic Jew explains the nature of angels in the Torah: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QbhS86UqNIU (accessed on 10 December 2024). |

| 32 | These ideas are propagated not only in the movie, but such an explanation is also typical to the Judaica narrative: “…Rivkah Kluger claims that ‘the Hebrew Bible knows no Satan’, no rebel angel who challenges the authority of God and tempts man […]. Nevertheless the passages, which refer to a celestial Satan, point to a progressive development of this figure in the Hebrew Bible. Rivkah Kluger suggests that, over time, one can detect a process of ‘cleansing Yahweh of his dark side’. That is, from Job to Zechariah to the book of Chronicles, there is a notable shift from the source of provocation being a functionary on behalf, perhaps even as an aspect of God, to a projection of malevolence onto the other, Satan (as accuser in the Higher court)” (Rachel 2009, pp. 64–65). |

| 33 | The book by Peter G. Riddell and Beverly Smith Riddell (Riddell and Riddell 2007) is dedicated to various visions of angels in different Christian denominations and in Islam. Those who are interested in classical religious literature will find extensive information in the works of Aquinas St. Thomas (2025), which aligns with the Catholic tradition, and Emanuel Swedenborg (1966), whose works resonate in Protestant thought. |

| 34 | There are many possible contexts for presenting angels and angelic-like creatures; in some clips, “angels” appeared as models at a fashion show (one of TikToker’s @mongo.ai videos). |

| 35 | “Glory be to God”. |

| 36 | In all quotes from network comments—original spelling. |

| 37 | “thou shalt not make unto thyself any representation of the things which are in heaven above”. |

| 38 | “but who told you that these creatures have this shape my brother. stop being so foggy!”. |

| 39 | https://time.com/5520558/artificial-intelligence-racial-gender-bias/; https://www.ajl.org/ (accessed on 4 February 2025). |

| 40 | The internet search was done in June 2024 in the broser Microsoft Bing, the keyword - “angels”. |

| 41 | The internet search was done in June 2024, the broser Microsoft Bing, the keywords - “angels” and “Ezekiel’s vision”. |

| 42 | https://wellcomecollection.org/works/yebnb6mv (accessed on 3 November 2024). |

| 43 | Alexis de Tocqueville, Chapter XVIII: Of Honor In The United States And In Democratic Communities, (https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/de-tocqueville/democracy-america/ch37.htm, accessed on 3 November 2024). |

| 44 | Ibidem. |

| 45 | It has already been mentioned that the rebellious angels are demonic creatures, which is no longer commented on in the narratives. |

References

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2013. Spiritual But Not Religious? Beyond Binary Choices in the Study of Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 258–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, Randall N. 1989. Inside the New Age Nightmare. Lafayette: Huntington House. [Google Scholar]

- Bannister, Robert C., ed. 1972. American Values in Transition. A Reader. New York: Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, Benjamin R. 2007. Consumed: How Markets Corrupt Children, Infantilize Adults, and Swallow Citizens Whole. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Berefelt, Gunnar. 1968. A Study on the Winged Angel: The Origin of a Motif. Translated by Patrick Hort. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell. [Google Scholar]

- Besançon, Alain. 2000. The Forbidden Image. An Intellectual History of Iconoclasm. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowker, John. 2004. The Complete Bible Handbook. London: Dorling Kindersley. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Dan. 2001. Angels and Demons. London: Transworld Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Buranelli, Francesco, Robin C. Dietrick, Cecilia Sica Marco Bussagli, and Roberta Bernabei. 2007. Between God and Man. Angels in Italian Art. Jackson: Mississippi Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- CCC. 1993. Catechism of the Catholic Church. Citta del Vaticano: Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/_INDEX.HTM (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Chowdhury, Rafi M. M. I. 2018. Religiosity and Voluntary Simplicity: The Mediating Role of Spiritual Well-Being. Journal of Business Ethics 152: 149–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danesi, Marcel. 2008. Popular Culture. Introductory Perspectives. Lanham-Plymouth: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Emberger, Gary. 2022. The Nonviolent Character of God, Evolution, and the Fall of Satan. Perspectives on Science & Christian Faith 74: 224–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Claude S. 2008. Paradoxes of American Individualism. Sociological Forum 23: 363–72. [Google Scholar]

- Fromm, Erich. 1968. The Revolution of Hope: Toward a Humanized Technology. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Fromm, Erich. 1994. Escape from Freedom. New York: Henry Holt & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, Rosa. 2003. Angeli e Demoni. I Dizionnaridell’Arte. Turin: Gruppo Editoriale L’Espresso, vol. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Giovetti, Paola. 2001. Aniołowie. Translated by Agnieszka Michalska-Rajch. Łódź: Ravi. [Google Scholar]

- Grzeszczyk, Ewa. 2003. Sukces. Amerykańskie Wzory—Polskie Realia. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo IFIS PAN. [Google Scholar]

- Heelas, Paul. 1996. The New Age Movement. The Celebration of the Self and the Sacralization of Modernity. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Heelas, Paul, and Linda Woodhead. 2005. The Spiritual Revolution: Why Religion is Giving Way to Spirituality. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Jarecka, Urszula. 2014. Świeckie „anioły”. Wyobrażenia para-anielskie w kulturze popularnej. In Religijność w Dobie Popkultury. Edited by Tomasz Chachulski, Jerzy Snopek and Magdalena Ślusarska. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo UKSW, pp. 146–172. [Google Scholar]

- Jarecka, Urszula, and Paweł Fortuna. 2022. Social media in the future: Under the sign of unicorn. In Studia Humanistyczne AGH. A special issue. Edited by Paul Levinson. Kraków: Wydawnictwa AGH, vol. 21, pp. 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Jaritz, Gerhard, ed. 2011. Angels, Devils: The Supernatural and Its Visual Representation. Budapest and New York: Central European University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jedynak, Witold. 1995. Neopogański Ruch New Age—Zagrożeniem dla Życia Religijnego. Niepokalanów: Wydawnictwo Ojców Franciszkanów. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Henry. 2008. Convergence Culture: Where New and Old Media Collide. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keen, Andrew. 2007. The Cult of the Amateur. How Today’s Internet is Killing Our Culture and Assaulting Our Economy. New York: Doubleday/Currency. [Google Scholar]

- Lasch, Christopher. 1991. The Culture of Narcissism. American Life in An Age of Diminishing Expectations. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, C.S. 2013. The Screwtape Letters: Annotated Edition. New York: Harper Collins. Available online: https://www.google.pl/books/edition/The_Screwtape_Letters_Annotated_Edition/aSj_-mgwWbYC?hl=pl&gbpv=1 (accessed on 20 September 2024) (the whole original version of 1941: https://www.samizdat.qc.ca/arts/lit/PDFs/ScrewtapeLetters_CSL.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2024)).

- Mode, Heinz. 1975. Fabulous Beasts and Demons. New York: Phaidon. [Google Scholar]

- Ouspensky, Léonide. 1990. Theology of the Icon. New York: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pearsall, Paul. 2004. Toxic Success: How to Stop Striving and Start Thriving. Makawo: Inner Ocean. [Google Scholar]

- Polak, Marian. 2001. Aniołowie w Historii Zbawienia. Warszawa: Michalineum. [Google Scholar]

- Rachel, Adelman. 2009. The Return of the Repressed Pirqe de-Rabbi Eliezer and the Pseudepigrapha. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Rand, Ayn. 1964. The Virtue of Selfishness: A New Concept of Egoism. Contributed by Nathaniel Branden. New York: New American Library. [Google Scholar]

- Riddell, Peter G., and Beverly Smith Riddell, eds. 2007. Angels and Demons. Perspectives and Practice in Diverse Religious Traditions. Nottingham: Inter-Varsity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rollin, Roger, ed. 1989. The Americanization of the Global Village. Essays in Comparative Popular Culture. Bowling: Bowling Green State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ryba, Thomas. 2018. The Fall of Satan, Rational Psychology and the Division of Consciousness. A Girardian Thought Experiment. Forum Philosophicum 23: 301–37. [Google Scholar]

- Schatz, Elihu A. 2008. Sons of Elokim as used in Genesis. Jewish Bible Quarterly 36: 125–26. [Google Scholar]

- Schor, Juliet B. 2004. Born to Buy. The Commercialized Child and the New Consumer Culture. New York: Scribner. [Google Scholar]

- St. Thomas, Aquinas. 2025. Summa Theologiae (Summa Theologica). Translated by Alfred J. Freddoso. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame. Available online: https://www3.nd.edu/~afreddos/summa-translation/toc.htm (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Swedenborg, Emanuel, trans. 1966. Heaven and Its Wonders and Hell. From Things Heard and Seen. London: The Swedenborg Society. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Charles. 2007. A Secular Age. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tocqueville, de Alexis. 2006. Democracy in America. Translated by Henry Reeve. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics. Available online: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/816 (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Turek, Andrzej. 2002. Sacrum na Sprzedaż. Symbolika Chrześcijańska w Reklamie. Lublin: Gaudium. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Toby. 2017. It’s Alive! Artificial Intelligence from the Logic Piano to Killer Robots. Collingwood: Schwartz. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, Laura, and Will Steeds. 2005. Angels: A Glorious Celebration of Angels in Art. London: Carlton Books. [Google Scholar]

- Wilk, Richard. 2001. Consuming Morality. Journal of Consumer Culture 1: 269–84. [Google Scholar]

- Wyllie, Irvin G. 1966. The Self-Made Man in America. The Myth of Rags to Riches. New York: Free Press—Collier-Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Zarasi, Mohammad, Abdollatif Ahmadi Ramchahi, and Iman Kanani. 2015. Satan in Dialogue with God: A Comparative Study between Islam, Judaism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism. Al-Bayan: Journal of Qur’an and Hadith Studies 13: 197–222. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jarecka, U. Secular “Angels”. Para-Angelic Imagery in Popular Culture. Religions 2025, 16, 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16030396

Jarecka U. Secular “Angels”. Para-Angelic Imagery in Popular Culture. Religions. 2025; 16(3):396. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16030396

Chicago/Turabian StyleJarecka, Urszula. 2025. "Secular “Angels”. Para-Angelic Imagery in Popular Culture" Religions 16, no. 3: 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16030396

APA StyleJarecka, U. (2025). Secular “Angels”. Para-Angelic Imagery in Popular Culture. Religions, 16(3), 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16030396