The Political Ideologies of the United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP) Under the Marcos Regimes

Abstract

1. Introduction

[S]ecularism shifts the focus from the institution to the people. The people exercise agency. In this sense, secularism opens the horizon for people to choose and decide on their own. Thus, religion is no longer controlled by organized religion but has been democratized through personal agency.(pp. 128–29)

1.1. The United Church of Christ in the Philippines

Protestant opposition in the Philippines is part of a worldwide reevaluation among Catholics and Protestants concerning the role of Christianity in dealing with unjust political, economic, and social structures that inhibit man’s full human development, particularly in regions of the world plagued by poverty and exploitation. Theologically, the reevaluation marks a shift away from the purely spiritual aspects of Christianity to greater stress on the social justice features of the Gospel. Politically, it represents a reaction to the failures of liberal democracy and developmentalism and the appearance of repressive regimes in much of the third world since World War II.(p. 66)

1.2. The Marcos Sr. and Marcos Jr. Administrations

1.3. UCCP’s Pastoral Statements

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. The Stance of the United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP) During Martial Law

That the Charter of Incorporation of said institutions must be consistent with or supportive of the policies of the General Assembly of the United Church of Christ in the Philippines as contained in its Constitution and By-Laws or such rules and regulations as may be promulgated by the General Assembly or its Executive Committee.(PS09)

All real properties of Church-related institutions acquired from Mission Boards or through the instrumentality of the United Church of Christ in the Philippines shall not be sold, disposed of, or encumbered without the previous approval of the General Assembly or its Executive Committee.(PS09)

Governing boards of such incorporated institutions and/or agencies must operate and/or conduct the affairs or business of said corporation within or under the general policies of the General Assembly of the United Church of Christ in the Philippines.(PS09)

For countless centuries, man lived a precarious existence upon the earth. He was threatened with extinction by wild animals, by famine, by pestilence, by disease, and by war. It is only within the last two centuries that overpopulation or the population explosion has become a threat to human beings. At least, the command God gave to Adam and Eve has been fulfilled: Be fruitful, and multiply, replenish the earth.(PS02)

In its physical purpose, marriage offers a means to marital companionship for the expression of love and the nourishment of the one-flesh marriage union, and also a means for the majority of couples to express their love and fulfill their union in procreation (Gen 1:28). Through the gifts of medical science, these ends are more clearly seen to be separable in God’s intent. Both contribute to the completeness of the marital union, but neither is subordinated to the other.(PS02)

While overpopulation is a great danger to the nation as a whole, too many babies may be catastrophic for an individual family. It may frustrate the possibility of further education for the father; it may ruin the mother’s health or sanity; and it may make it impossible for the children to receive the care and education that will enable them to develop their God-given capacities and be assets to society.(PS02)

The new knowledge of reproduction and contraception underscores the responsibility of the couple to make parenthood or its postponement matters of ethical and caring decisions.(PS02)

For positive efforts by competent persons in giving sound family planning information and materials to underprivileged families who come to church-related hospitals, clinics, community centers, and other social agencies. This counsel would be given as a matter of routine, as other needs are met.(PS02)

We are alarmed by the rapid growth of multinational corporations in the Philippines. We are particularly concerned about the adverse effect of the Philippine-Japan Treaty of Commerce and Navigation. We therefore call on the appropriate authorities and knowledgeable citizens to be most vigilant and to share their thinking as widely as possible, so that the people can participate in making decisions that affect their livelihood and their future.(PS03)

The preferential treatment accorded multi-national Corporations resulting in the exploitation of our natural resources for the benefit of these foreign interests; and the irreparable damage inflicted on our environment due to the uncontrolled operations of agricultural and industrial corporations.(PS08)

Announcement has been made that there might be another referendum within a month or two. Whenever it may be and whatever the issues are, we request the President that he reassures us that there is freedom of speech so that voters can discuss the issues intelligently. Our people should be encouraged to speak out their minds candidly. Furthermore, to help give maximum assurance to our people that fairness and freedom are truly respected, we suggest to the President that the conduct of the coining referendum be entrusted to an independent body composed of citizens whose integrity is beyond reproach, such as the retired justices of the Supreme Court.(PS03)

Under the regime of Martial Law, the military has a big hand in the carrying out of government programs. We pray that they will have the strength equal to the task. We are deeply concerned by the fact that many of those being detained have not been charged in court. We appeal for a more speedy dispensation of justice. Furthermore, we express disapproval of any maltreatment of citizens, believing that every individual, however lowly and humble he may be, is a child of the Heavenly Father.(PS08)

The violation of basic human rights of the greater majority of our people, including the right of food, clothing and shelter; The enslavement of the greater majority of our people, producing crippled beings, not creatures of God, enmeshed in a culture of silence.(PS03)

The Church makes a firm stand against forces of underdevelopment, especially among the cultural communities. Such a condition is sin and people manipulating such factors to further their greed at the expense of the people are sinners in any language.(PS05)

Church take a firm stand in its concern for justice for both Christians and other cultural communities, thus paving the way for development.

To stand for and with the Muslims as a people searching for their identity and direction in history; to assist in the process of building-up a people in their struggle for peace where genuine dialogue can take place on an equal relationship between the oppressor and the oppressed.(PS07)

Only when the Body of Christ moves from its position of status quo to its high calling for exodus based on its vision for the last quarter of the century can it be transformed and transforming as well.(PS07)

2.2. UCCP’s Ideologies During the Marcos Jr. Administration

2.3. The UCCP’s Political Ideology Under Marcos Sr. and Marcos Jr. Through the Lens of Demeterio’s Modified Spectrum

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBCP | Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines |

| POPCOM | Commission on Population |

| UCCP | United Church of Christ in the Philippines |

References

- Abellanosa, Rhoderick John S. 2020. Abuse, elitism, and accountability: Challenges to the Philippine Church. Asian Horizons 14: 361–80. Available online: https://dvkjournals.in/index.php/ah/article/view/2906/2782 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Aguilan, Victor. 2016. Mission and climate justice: Struggling with God’s creation. In “Mission Still Possible?”: Global Perspectives on Mission Theology and Mission Practice. Edited by Jochen Motte and Andar Parlindungan. Solingen: United Evangelical Mission. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilan, Victor. 2020. The Church as Servant of Peace in the Philippines: A Diaconal Engagement. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/42106935/The_Church_as_Servant_of_Peace_in_the_Philippines_a_Diaconal_Engagement (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Akhter, Farida. 1989. On the question of the reproductive right: A personal reflection. Paper presented at the FINRRAGE-UBINIG International Conference, Bard, Kotbari, Comilla, Bangladesh, March 19–25; Available online: https://www.finrrage.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Comilla_Proceedings_1989.pdf#page=29 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Aquino, Belinda. 1984. Political violence in the Philippines: Aftermath of the Aqunio assassination. Southeast Asian Affairs, 266–76. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27908506 (accessed on 25 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Astorga, Ma. Christina. 2006. Culture, religion, and moral vision: A theological discourse on the Filipino People Power Revolution of 1986. Theological Studies 67: 567–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayson, Miguel Enrico G., and Lara Gianina S. Reyes. 2023. The Philippines 2022–2023: A turbulent start for the New Era of Marcos leadership. Asia Maior 34: 167–185. Available online: https://www.asiamaior.org/files/08-AM2023-Philippines-1.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Barry, Coeli M. 2006. The limits of conservative Church reformism in the democratic Philippines. In Religious Organizations and Democratization. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Basu-Zharku, Iulia O. 2011. The Influence of Religion on Health. Available online: http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/367/the-influence-of-religion-on-health (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Batalla, Eric Vincent, and Rito Baring. 2019. Church-State separation and challenging issues concerning religion. Religions 10: 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, Julius. 2009. Living Piously in a Culture of Death: The Catholic Church and the State in the Philippines. Asia Research Institute Working Paper No. 130. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1716529 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Bello, Walden. 2007. Benigno Aquino: Between dictatorship and revolution in the Philippines. Third World Quarterly 6: 283–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, Cheryl A. 2011. The Position of the Catholic Church in Political and Social Relations of the Philippines. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/1206897/The_Position_of_the_Catholic_Church_in_Political_and_Social_Relations_of_the_Philippines (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Canceran, Delfo. 2010. The secularization thesis and its discontent. Justitia 15: 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Caralde, Mae. 2016. Of bodies, death, and martyrdom: The case of Ninoy and Cory Aquino’s death and the re-articulations of Philippine political narratives. The International Journal of Critical Cultural Studies 14: 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartagenas, Aloysius. 2015. Religion and politics in the Philippines: The public role of the Roman Catholic Church in the democratization of the Filipino polity. Political Theology 11: 846–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catholic Bishop of the Philippines. 1973. Population Problem and Family Life. Available online: https://cbcponline.net/pastoral-letter-of-the-catholic-hierarchy-of-the-philippines-on-the-population-problem-and-family-life/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Chopko, Mark. 2003. Stating Claims Against Religious Institutions. Available online: https://lira.bc.edu/files/pdf?fileid=805dce41-ec16-47af-86d8-9c2c886c266c (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Chua, Michael Charleston “Xiao” Briones. 2023. Tortyur: Human Rights Violations During the Marcos Regime. Available online: https://xiaochua.net/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/chua-tortyur-revised-2023-09-24-2.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Collantes, Christianne F. 2018. Reproductive Dilemmas in Metro Manila. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelio, Jayeel, and Erron Medina. 2019. Christianity and Duterte’s War on Drugs in the Philippines. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group 20: 151–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelio, Jayeel, and Robbin Dagle. 2019. Weaponising Religious Freedom: Same-Sex Marriage and Gender Equality in the Philippines. Archīum. ATENEO. Available online: https://archium.ateneo.edu/dev-stud-faculty-pubs/8 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Crisostomo-Pilario, Junesse d.R. 2022. Church talks on peace talks: The United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP) and the Duterte Presidency. Social Sciences & Missions 35: 137–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupin, Bea. 2021. This Study Says Filipinos Trust Religious Leaders, Journalists the Most. Available online: https://www.rappler.com/philippines/filipinos-trust-religious-leaders-journalists-philippine-trust-index-2021-results/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- De Guzman, Miguel. 2025. 73% of Pinoys Believe Religion Is Very Important to the Filipino Identity—Study. Available online: https://philstarlife.com/news-and-views/231475-73-percent-pinoys-believe-religion-very-important-to-filipino-identity?page=2 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Demeterio, Feorillo Petronillo. 2012. Ang mga Ideyolohiyang Politikal ng Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines. Manila: De La Salle University Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Doce, Brian U. 2018. Revisiting the Philippine reproductive health politics via the lens of public theology: The role of progressive Catholic and Protestant sectors. Politics and Religion Journal 12: 285–307. Available online: https://animorepository.dlsu.edu.ph/faculty_research/367 (accessed on 25 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Felicilda, Joshua Mariz, and Feorillo Petronilo A. Demeterio, III. 2019. Ang mga ideolohiyang politikal na nakapaloob sa Rosales Saga ni F. Sionil Jose. Humanities Diliman: A Philippine Journal of Humanities 16: 111–33. Available online: https://journals.upd.edu.ph/index.php/humanitiesdiliman/article/view/6683 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Freedom House. 2025. Freedom in the World 2025. Available online: https://freedomhouse.org/country/philippines/freedom-world/2025 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Gopez, Christian P., and Feorillo A. Demeterio, III. 2022. Ang mga Ideolohiyang Politikal ng Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) at United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP) sa Panahon ng Administrasyong Duterte. Social Science Diliman 18: 1–30. Available online: https://www.humanitiesdiliman.upd.edu.ph/index.php/socialsciencediliman/article/view/9539/8419 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Grzymala-Busse, Anna M. 2015. Nations Under God: How Churches Use Moral Authority to Influence Policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heriot, Geoff. 2025. Book Review: Reinventing Marcos: From Dictator to Hero. Available online: https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/book-review-reinventing-marcos-from-dictator-to-hero/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Herrin, Alejandro N. 2002. Population Policy in the Philippines, 1969–2002. Available online: https://pidswebs.pids.gov.ph/CDN/PUBLICATIONS/ris-old-backups/dps/pidsdps0208.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Heydarian, Richard Javad. 2022. The return of the Marcos dynasty. Journal of Democracy 33: 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, William. 2014. The New People’s Army and Neoliberal Mining in the Philippines: A struggle against primitive accumulation. Capitalism Nature Socialism 25: 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International IDEA. 2025. Philippines. Available online: https://www.idea.int/democracytracker/country/philippines (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Itao, Alexis Deodato S. 2022. The political moralism of some Catholic bishops and priests: A postmodern evaluation. Social Ethics Society Journal of Applied Philosophy, 186–212. Available online: https://philpapers.org/archive/ITATPM-3.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Kjølen, Anders. 2017. How the Catholic Church Influence Italian Politics. Master’s thesis, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway. Available online: https://bora.uib.no/bora-xmlui/bitstream/handle/1956/17416/Masteroppgaven-Anders-Kj-len.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Klaiber, Jeffrey. 2009. The Catholic Church, moral education and citizenship in Latin America. Journal of Moral Education 38: 407–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximiano, Jose Mario Bautista. 2018. Martial Law and Jaime Cardinal Sin. Available online: https://usa.inquirer.net/15903/martial-law-jaime-cardinal-sin (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Mendoza, Meynardo. 2013. Is closure still possible for the Marcos human rights victims? Social Transformations Journal of the Global South 1: 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merez, Arianne. 2018. PH Among World’s Most Religious Countries: Study. Available online: https://www.abs-cbn.com/news/05/09/18/ph-among-worlds-most-religious-countries-study (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Miranda, Felipe, Temario Rivera, Malaya Ronas, and Ronald Holmes. 2011. Chasing the wind: Assessing Philippine Democracy. Quezon City: Commission on Human Rights, Philippines. [Google Scholar]

- Mondares, Jury Angelique, Josh Anghelee Buencamino, Angelie Sumagaysay, Michael Dee Weng, Jr., Rhenel Paragas, Elijah Kurt Bondoc, and Mc Rollyn Vallespin. 2023. Balancing Church and State: An analysis of Philippine politics, issues, and the impact of separation. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Publications 1: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napatotan, Yzian Khyle, Ryan Jade Abud, Ralph Bryant Tarape, Nichael Ashley Pascual, and Mc Rollyn Vallespin. 2024. Public opinion and policy impact: Assessing Church-State separation in the Philippines. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Publications 6: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, Artur, and John T. Jost. 2020. The authoritarian-conservatism nexus. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 34: 148–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overholt, William H. 1986. The rise and fall of Ferdinand Marcos. Asian Survey 26: 1137–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Capulla, Rose, and Feorillo Petronilo A. Demeterio, III. 2023. Mga ideolohiyang politikal na nakapaloob sa mga obra ng sining saysay na kabilang sa panahon ng Batas Militar hanggang sa kasalukuyan. Humanities Diliman: A Philippine Journal of Humanities 20, 2: 72–106. Available online: https://journals.upd.edu.ph/index.php/humanitiesdiliman/article/view/9458 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Reyes, Portia. 2018. Claiming history: Memoirs of the struggle against Ferdinand Marcos’s Martial Law regime in the Philippines. Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 33: 457–498. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26538540 (accessed on 25 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Rigos, Cirilo A. 1975. The posture of the Church in the Philippines under Martial Law. Southeast Asian Affairs, 127–32. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27908249 (accessed on 25 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Rozier, Michael. 2020. A Catholic contribution to global public health. Annals of Global Health 86: 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufo, Aries C. 2013. Altar of Secrets: Sex, Politics, and Money in the Philippine Catholic Church. Manila: Journalism for Nation Building Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Shoesmith, Dennis. 1979. Church and Martial Law in the Philippines: The continuing debate. Southeast Asian Affairs 6: 246–57. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27908361 (accessed on 25 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Slomp, Hans. 2000. European Politics into the Twenty-First Century. Westport: Praeger Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Talamayan, Fernan. 2021. The politics of nostalgia and the Marcos Golden Age in the Philippines. Asia Review, 273–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taya, Shamsuddin L. 2008. Political legal overview perspective: Evaluating human rights in the Philippines. REKAYASA—Journal of Ethics, Legal and Governance 4: 87–98. Available online: https://repo.uum.edu.my/id/eprint/11936/1/9.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Teehankee, Julio. 2023. Beyond Nostalgia: The Marcos Political Comeback in the Philippines. London: Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, pp. 1–46. Available online: https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/119819/3/Southeast_Asia_Working_Paper_7_Beyond_Nostalgia_The_Marcos_Political_Comeback_in_the_Philippines.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Thompson, Mark R. 2023a. Pushback to backsliding: Unconstrained executive aggrandizement in the Philippines versus contested military-monarchical rule in Thailand. In Democratic Backsliding in Southeast Asia. Edited by William Case. London: Routledge, pp. 94–111. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Mark R. 2023b. Whatever happened to the ‘Aircon Opposition’ to Marcos? Or, how the ‘Yellows’ Turned Pink with embarrassment. In The Marcos Reader. Edited by Leia Castaneda-Anastacio and Patricio N. Abinales. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tibus, Van Cliburn. 2017. A Missiological Study of the United Church of Christ in the Philippines in Its Constitution and General Assembly Documents. Master’s thesis, Siliman University, Dumaguete, Philippines. Available online: https://www.vemission.org/fileadmin/redakteure/Dokumente/Tibus_Thesis_UCCP_Study.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Tolentino, Roy Allan B. 2010. Blessed ballots: Bloc voting in the Iglesia ni Cristo and the Roman Catholic Church in the Philippines. Gema Teologi 24: 83–99. Available online: https://journal-theo.ukdw.ac.id/index.php/gema/article/view/23/18 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Turner, Mark M. 2011. Authoritarian rule and the dilemma of legitimacy: The case of President Marcos of the Philippines. The Pacific Review 3: 349–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UCCP (United Church of Christ in the Philippines). 1990. UCCP Statements and Resolutions, 1948–1990. Quezon City: Education and Nurture Desk, United Church of Christ in the Philippines. [Google Scholar]

- UCCP (United Church of Christ in the Philippines). 2015. Amended Constitution and By-Laws. Available online: https://uccpchurch.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/final-uccp_cbl.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- UCCP (United Church of Christ in the Philippines). 2020. Why Is UCCP a “Uniting Church”? Available online: https://www.uccpchurch.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/DOP-OE-Lessons-16-25-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- UCCP Identity. n.d. Available online: https://www.uccpchurch.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/ANNEX-B_UCCP-IDENTITY_Its-Being-and-Becoming-1.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- van Erven, Eugene. 1987. Philippine political theatre and the fall of Ferdinand Marcos. The Drama Review: TDR 31: 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Wylin D. 2017. Economic Ethics & the Black Church. New York: Palgrave Macmillan Cham, pp. 1–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Council of Churches. n.d. United Church of Christ in the Philippines. Available online: https://www.oikoumene.org/member-churches/united-church-of-christ-in-the-philippines (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Wurfel, David. 1977. Martial Law in the Philippines: The methods of regime survival. Pacific Affairs 50: 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Yiwei, and Yuanlin Wang. 2024. The separation of Church and State as an imperial project in the Philippines during the early American colonial period. Religions 15: 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngblood, Robert L. 1978. Church opposition to Martial Law in the Philippines. Asian Survey 18: 505–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngblood, Robert L. 1987. The Corazon Aquino “Miracle” and the Philippine churches. University of California Press 27: 1240–55. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2644632 (accessed on 1 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Youngblood, Robert L. 1990. Marcos Against the Church: Economic Development and Political Repression in the Philippines. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp. 1–205. [Google Scholar]

- Yuzon, Lourdino Aranas. 1974. An Analysis and Evaluation of the Social Mission of the United Church of Christ in the Philippines. Doctoral dissertation, Silliman University, Dumaguete City, Philippines. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/302745750?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Zarsadiaz, James. 2021. Methodists against Martial Law: Filipino Chicagoans and the Church’s role in a global crusade. Alon: Journal for Filipinx American and Diasporic Studies 1: 353–59. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/48644349 (accessed on 1 July 2025). [CrossRef]

| Code | Statement |

|---|---|

| PS34 | The fate of Rodrigo Duterte serves as a significant cautionary tale for those who would dare to misuse their authority. The Scriptures present a stern admonition in Exodus 22:22–24. “One must not subject any widow or orphan to mistreatment. If you choose to mistreat them, and they raise their voices in distress, I will undoubtedly heed their pleas. My anger will ignite, and I shall bring forth retribution upon you, resulting in your wives becoming widows and your children left without a father.” We implore our authorities to let justice run its course. We beseech our constituents to maintain a watchful and resolute stance in our faith and prayers, trusting that justice will soon be delivered to the victims. In support of the thousands of victims of terror and violence, we join the cry for justice and accountability. |

| Code | Statement |

|---|---|

| PS18 | Latest nuisance suit is another vain effort to further their persecution of Church leaders by putting the lives of bishops, church workers, and members in danger by prejudice, misrepresentation, incitement to hatred and filing of baseless charges, coupled with malicious red-tagging. We urge our Church members to thwart the destructive schemes of those who have filed the perjury case with the apparent goading of the State and its agencies and forces who are intolerant of dissent and afraid of the truth. Pray for our Church’s leaders and members, whose lives are in danger and whose personal and family lives are ruined by reckless and ill-motivated accusations of criminal acts. |

| PS29 | Psalm 82:3–4 calls us to “Defend the weak and the fatherless; uphold the cause of the poor and the oppressed. Rescue the weak and the needy; deliver them from the hand of the wicked.” In this spirit, we, the United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP), raise our collective voice to demand the immediate release of Ptr. Jimie Teves Sr., Jodito Montesino, Jaypee Romano, Jasper Aguyong, Rogen Sabanal, Rodrigo Sabanal, Rodrigo Medez, and Elesio Andress, also known as the Himamaylan 7. These individuals have been wrongfully imprisoned, falsely accused, and subjected to ongoing persecution for their unwavering commitment to genuine land reform, social justice for the national minorities, and lasting peace. Let us not passively witness their plight but actively work and pray for their release, for the strength and perseverance of their families, and for the restoration of truth and justice in our land. We believe that God is a God of justice, mercy, and truth, and we trust that, in time, those who seek to do His will and stand with the oppressed will be vindicated. These actions are not just attacks on the truth but also direct assaults on the Church’s mission to serve the oppressed, as Christ Himself did. As UCCP, we stand as a beacon of light in the darkness, proclaiming: injustice will not prevail. |

| PS34 | The fate of Rodrigo Duterte serves as a significant cautionary tale for those who would dare to misuse their authority. The Scriptures present a stern admonition in Exodus 22:22–24. “One must not subject any widow or orphan to mistreatment. If you choose to mistreat them, and they raise their voices in distress, I will undoubtedly heed their pleas. My anger will ignite, and I shall bring forth retribution upon you, resulting in your wives becoming widows and your children left without a father.” We implore our authorities to let justice run its course. We beseech our constituents to maintain a watchful and resolute stance in our faith and prayers, trusting that justice will soon be delivered to the victims. In support of the thousands of victims of terror and violence, we join the cry for justice and accountability. |

| PS10 | For his first 100 days in office, we expect the incoming president to listen to the voice and heed the urgent demands of the most vulnerable and oppressed sectors of our society: the poor and disadvantaged farmers of the land, the exploited workers, the dispossessed urban poor families, the overburdened migrant workers, the browbeaten fisherfolks, the deprived youth and the ill-treated women in society. “Speak up for those who cannot speak for themselves, for the rights of all who are destitute.” Speak up and judge fairly; defend the rights of the poor and needy” (Proverbs 31:8–9). |

| PS11 | In the past, we have not only seen and heard, but more so experienced first-hand the atrocities committed by our leaders especially during the Martial Law years under the Ferdinand E. Marcos Sr. presidency. Because of this, your people painfully learned the lessons of oppression and tyranny leading us to decide to put an end to such leadership through your inspiration and power, peacefully wielded by your people through the People Power revolution. perhaps we have forgotten the lessons of the past, for if the recently-conducted elections were truly without fraud, we can say that we have chosen the son and namesake of the oppressive and tyrannical leader of our country’s Martial Law years to now lead us. Forgive us, dear God, for forgetting the precious lessons of the past, for not being able to enlighten and fully guard the hearts and minds of our sons and daughters and thereby allowing them to be exposed to lies and distortions of truth, leading them to choose again another Marcos who believes that the time of his father’s leadership, those years that we were under Martial Law, was a “Golden Age” of our country’s prosperity, a great lie perpetuated to distort and change the truth. We ask for courage to be able to continue to speak out the truth in behalf of those who cannot speak for themselves and, as the prophet Isaiah strongly reminds us, to fast by loosing the chains of injustice, untying the cords of the yoke and setting the oppressed free. |

| PS12 | Within the perspective of recent history where popularity of political leaders from dynastic families and rising into the top positions of the country, the majority of youth lack of adequate knowledge and understanding of the dark years of Martial Law from 1972 to 1986, allowed the proliferation of fantasy coated perception of the realities contingent on the Philippine society. The state’s tendencies to revert back to repressive and totalitarian governance, should make the Church vigilant and enable the Church members to hold fast to their faith imperatives along with the principles of international human rights law, affirm and emphasized the necessity of such a universal framework of legal accountability for the violation of human dignity and rights. Despite our staunch advocacy for respect and protection of human rights and upholding human dignity both past and present, there still exists violations, such as illegal arrests, red-tagging, and various forms of denigration of the Church, its leaders, church workers and the laity. In the purview of the continuing state policies from Duterte to Marcos Jr. government, the Church decry and laments these prevailing situations: |

| PS14 | What is concerning is the alignment of these voices with the coercive and tyrannical powers in society, which proves to us the continuing existence of the clerico-fascist attacks reminiscent of Martial Rule as imposed 50 years ago today (21 September 1972). |

| PS21 | President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. and his family have been living extravagant lifestyles for the past 11 months while the majority of Filipinos wallow in extreme poverty and hunger as a result of skyrocketing inflation, low wages, and insufficient social services. Without taking tangible steps to end long-standing abuse patterns and ensure justice for previous human rights crimes, President Marcos’ talks lack credibility. He needs to show more than just platitudes about democracy and the rule of law. President Marcos needs to do more than just issue statements about democracy and the rule of law to demonstrate a genuine commitment to human rights. Hitherto, all his election campaign promises remain to be empty rhetoric and his avowals mere bombast words. Marcos Jr’s initiative to achieve genuine and long-lasting peace has not yet been seen. As of yet, there has been no evidence of the government’s willingness to pursue peace negotiations with the NDFP as a viable option for bringing about peace and stability in the nation. Instead, he has carried on his predecessor’s harsh counter-insurgency campaign to crush resistance and prop up power. The Marcos Jr. government has, in fact, bolstered its red-tagging against perceived enemies and critics. |

| PS23 | This 21st of September 2023, we join the nation in commemorating the 51st year of the Declaration of Martial Law. The nightmarish experiences of one-man rule taught us to defend and value democracy and declare that never again should our civil liberties be imperiled, our human dignity violated and human life desecrated. In the same statement was emphasized that UCCP is against the perpetuation of a one-man rule in the country; that it is for the immediate restoration of all the civil and political liberties of the citizens; and that it is for the immediate dismantling of the machinery of Martial Law in the country. Our faith in the God of justice and peace is the strong foundation of our ethical response we have been expressing in the many challenging historical junctures of our society and the world. More so, we admonish our faith communities to keep abreast of the laws and the State’s instrumentalities violative of the constitutional rights, civil liberties, equity and social justice. We have been subjected to the Anti-Terrorism Law (ATL) implemented by the various departments of the government particularly by the Department of Defense, the Department of Justice, the AFP and the NTF-ELCAC. This embodies the “One Nation Approach” an inti-insurgency strategy that is now being strengthened by additional funding by the various government offices such as the Department of Education, and other branches of government. All these are vestiges of Martial Law that still remain in our country and these will continue to be used to persecute and oppress persons, institutions and organizations that are critical of government policies. However, victims and survivors do their share of advocacy for protection of human rights, and giving humanitarian services to marginalized communities and struggling sectors of society. |

| PS25 | As the country marks the 52nd anniversary of the imposition of Martial Law, the United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP) joins the Filipino people in commemorating this historic day. The UCCP restates its conviction that Martial Law is fundamentally bad. It blatantly disregards the rule of law, democracy, human rights, and justice, amply demonstrating a corrupt system of government. In the face of repressive systems that oppress people and violate their inalienable rights to live in peace and completeness, the UCCP never wavers in its prophetic mission. The UCCP Constitution and By-Laws, Article II, Section 5, Declaration of Principles, states that “the fundamental values of love, justice, truth, and compassion are at the heart of our witness to the world and our service to the Church. As a well-known hymn tells us, let us “learn the lessons of the past and not repeat history.” Although foreign dominance and colonization have played a significant role in our history, it is also a tale of rebellion and fight against oppression. History can teach us important lessons that we can apply to our decisions and actions in the present when we see it through the eyes of faith. |

| Code | Statement |

|---|---|

| PS32 | We must also remember the people’s demand for the prosecution of the Marcos family, accountability for their crimes, and the return of the nation’s stolen wealth. Yet, they remain unrepentant. Worse, Ferdinand Marcos Jr. was elected president despite complaints of massive election fraud and other irregularities. Once again, the people were deceived by political rhetoric about good governance—without the track record to support it. As long as corrupt politicians and government officials enrich themselves rather than serve the people—collaborating with big businesses and foreign corporations for personal gain while ordinary Filipinos suffer from poverty and inadequate public services—real change will remain elusive. As long as a few wealthy families control most of the land while many farmers and workers remain impoverished, and as long as urban laborers continue to face unjust conditions—low wages and job insecurity—wealth and power will remain concentrated in the hands of the few, while the majority of Filipinos struggle. |

| PS35 | This election presents a vital opportunity to dismantle systems that perpetuate inequality and embrace a future built on genuine representation, particularly for marginalized and underrepresented sectors. Genuine change requires a fundamental reconfiguration of the political landscape. We must move beyond empty promises and address entrenched inequalities and injustices with concrete actions. We urge the Commission on Elections (COMELEC) to take decisive action in investigating and disqualifying bogus party-lists—especially those backed by traditional political elites or involved in red-tagging, harassment, and other electoral violations. These deceptive practices erode the integrity of the democratic process and suppress the voices of those most in need of representation. Genuine participation from marginalized communities is not only a democratic imperative—it is essential to building a just and equitable society. The United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP) calls on all voters to carefully examine the platforms of candidates and to hold them accountable beyond election day. We urge you to support leaders who are genuinely committed to serving the people, upholding the Constitution, and advancing the common good—especially those who stand firmly against political dynasties and the misuse of the party-list system. The UCCP reaffirms its commitment to active political engagement—advocating for justice, peace, and a truly democratic Philippines. |

| PS36 | Voting dynastic candidates has several negative consequences: it limits competition and accountability; concentrates power, potentially fostering authoritarianism; prioritizes personal gain over public good; exacerbates inequality; and hinders transparency and anti-corruption efforts. This concentration of power undermines democratic governance and equitable development. The hijacking of the Party-list system by traditional politicians undermines its intended purpose: to represent marginalized sectors. Instead, it becomes a tool for these politicians to consolidate power and resources, further exacerbating inequality and hindering genuine representation. Proverbs 29:2 (When the righteous are in authority, the people rejoice) and Micah 6:8 (act justly and to love mercy) guide our electoral choices. As Christians, we are called to responsible citizenship, choosing leaders embodying integrity, accountability, transparency, and commitment to the common good. Matthew 25:31–46 reminds us of our responsibility to care for the least among us, extending to our political choices. We must elect leaders who champion the poor and vulnerable. |

| Code | Statement |

|---|---|

| PS13 | It was the ongoing harassment and intimidation in Mindanao where UCCP was linked with communists along with the Iglesia Filipina Indepediente. In this pastoral statement, our Church continues to uphold that, “The UCCP is not, never was, and will never be a communist.” The present repression experienced by the Church from the state is alarming. It even moves now inside the circle of our church workers. The Church that trains and entrusts God’s flock is now attacked by her shepherd. The shepherd who is supposed to protect the flock from wrong teachings and expected to continue the mission of God is now allowing misinformation and allegations to destroy Christ’s identity. It causes a scattering of speculations within our community of faith that clouded our minds by forgetting our identity as a church. We are standing here like Paul, the Prophets, and Jesus Christ who are being accused with so many allegations without any proof, just because of the faith that is anchored in God’s mission. Thus, let us remember that we must be aware and mindful that no shepherd will allow its flock to be destroyed and scattered. |

| PS19 | Despite political and economic class distinctions, the quality of life of the commoner or ordinary citizen is put into question. They, in the echelons of political and economic power assume that they represent their constituents’ interests and advocate for their needs and concerns. They do budget planning, and oversight of government agencies. It is time, an occasioned time to make amends and change; The call of laborers, employees and all those who are paid below decent living wages. Should be acted now! |

| PS33 | Many Filipino women confront the harsh reality of systemic poverty on a daily basis. Insufficient salaries, along with the high cost of essential goods, result in families struggling to meet their most basic needs. Access to fundamental social services like healthcare, education, and adequate housing remains unattainable for many women, further intensifying their vulnerability. Widespread corruption in our government misappropriates resources that may mitigate these adversities, exacerbating the cycle of poverty and inequality. Moreover, the covert menace of human rights abuses, illustrated by the recent fabricated accusations against UCCP clergy and laypersons in Southern Tagalog, renders women vulnerable to violence, discrimination, and exploitation. These injustices against advocates for the vulnerable constitute a direct assault on the fundamental structure of our society. The fortitude and bravery exhibited by these women, reflecting the resilience of women in the Bible, motivate us to persist in our struggle. Call to address the roots of the armed conflict: We urged the government of the Philippines and the National Democratic Front of the Philippines to go back to the negotiation table to address the deep-seated issues fueling conflict in the country. Let this International Women’s Day be a day of renewed commitment to building a more just and compassionate Philippines, a commitment fueled by the memory of those who fought and died for this very ideal, and inspired by the enduring strength of women throughout history and faith. The UCCP remains steadfast in its unwavering commitment to pursuing justice and abundant life for all. |

| PS31 | Many Filipinos lack access to affordable healthcare, education, and social services, making it harder for them to escape poverty even in times of economic growth. This is exacerbated by natural disasters and climate change. The Philippines’ vulnerability to typhoons, earthquakes, and other natural disasters disrupts livelihoods and disproportionately affects the poor, undermining economic growth at the local level. As concerned Christians, we cannot turn a blind eye to the cries of the poor. The Scripture reminds us: “Whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me” (Matthew 25:40). This is a time for action, compassion, and solidarity. We must challenge the structures of oppression and advocate for a society that values justice and upholds the dignity of every human person. To the faithful, we urge you to embody Christ’s love by caring for one another, especially the least among us. Support community-based initiatives, advocate for fair labor practices, and share your resources with those in need. Let us stand united in demanding systemic changes and fostering a culture of justice, equity, and compassion. |

| PS26 | The Church acknowledges the systemic oppression that Indigenous Peoples have faced, including displacement, militarization, and the exploitation of their resources by corporations and state actors. The prophetic accounts in the Old Testament denounce systemic injustice and exploitation, as reflected in Isaiah 10:1–2: “Woe to those who make unjust laws, to those who issue oppressive decrees, to deprive the poor of their rights and withhold justice from the oppressed of my people, making widows their prey and robbing the fatherless.” Amos 5:24 challenges us with the words, “But let justice roll down like water and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.” These scriptures challenge the Church to confront the injustices experienced by Indigenous Peoples, including land dispossession, discrimination, and cultural suppression. As the UCCP marks October as Indigenous Peoples Solidarity Month and designates every third Sunday as Indigenous Peoples’ Sunday, we urge all churches, faith communities, and civil society organizations to advocate for the rights and welfare of Indigenous Peoples. Together, we must raise awareness, promote dialogue, and support initiatives that uphold the dignity and rights of our Indigenous brothers and sisters. As we stand with them, we pray for the day when justice and peace prevail in their communities, allowing them to live in harmony with their land, free from exploitation and oppression. In the spirit of faith and solidarity, we will continue to walk with Indigenous Peoples on their journey toward liberation, justice, and healing until all people experience life in its fullness. |

| PS28 | The United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP) is deeply saddened by the reality that many Filipinos have lost their homes, livelihoods, lives, and even hope for a better future. This situation highlights that the most vulnerable among us are disproportionately affected by these calamities. We extend our heartfelt gratitude to our local churches and conferences that have initiated relief operations to respond to the urgent needs of our brothers and sisters affected by the storm. However, our call for accountability from our government remains steadfast, particularly regarding the lack of disaster preparedness and risk mitigation planning. Delayed disaster responses, especially in rescue efforts, expose the deep-rooted neglect within our systems and the urgent need for change. |

| PS30 | We join the expressions of support extended to her and her family, from Philippine and Indonesian advocates, and the international community. We remember Mary Jane Veloso’s prolonged years in Indonesia. Holy One, with the lighting of Advent candles, we also ignite our prayers for Mary Jane Veloso and her family. Accept these candle-prayers. Even as the world awaits the labors of these migrants, we affirm their dignity, in asserting the promotion and protection of their human rights, throughout their migration journeys. While waiting for loans and paperwork, migrants also look forward to providing for their families’ daily needs and dreams. Waiting for their next meals, clean homes, child and elder care, families of foreign domestic workers labor for their family-employers. Waiting for their next meals and products, gig drivers deliver for these appetites. While anticipating their next port of call, seafarers service ships and vessels. Ready for the fashion and technology trends, factory workers strive for the consumers. Building everything from ships to skyscrapers to sporting arenas, construction workers and engineers connect people and places. |

| Dimension | Marcos Sr. Era (1972–1986) | Marcos Jr. Era (2022–Present) |

|---|---|---|

| Political Environment | Military rule, suspension of civil liberties, direct repression | Electoral democracy with authoritarian regression, disinformation, red-tagging |

| UCCP Position | Conservative Authoritarianism → Quiet Resistance | Moderate Progressivism |

| Church Response | Institutional protection, quiet resistance, moral appeals | Public denunciation of injustice, advocacy for historical truth, human rights |

| Theological Lens | Emphasis on institutional order, indirect references to injustice | Liberationist ethics, structural sin, biblical justice |

| Role in Civil Society | Defensive autonomy, internal focus | Active engagement, coalition-building, prophetic witness |

| No. | Title | Publication Date | Category | * Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Emphasis of the Whole Church | 7–8 December 1973 | Social | PS01 |

| 2 | Statement on Responsible Parenthood and Family Planning | 31 May–5 June 1974 | Political | PS02 |

| 3 | A Statement on Martial Law and Expression of Concern on Related Issues | 20 May 1974 | Political | PS03 |

| 4 | Statement of Petition to the United Presbyterian Church, USA Regarding the Disposition of the Property on Guerrero Street, Malate, Manila | 5–7 December 1974 | Social | PS04 |

| 5 | Statement on Cultural Communities Affairs | 19–20 May 1975 | Political | PS05 |

| 6 | On the Church and Development | 21–26 May 1978 | Social | PS06 |

| 7 | On the Mindanao Situation | 21–26 May 1978 | Political | PS07 |

| 8 | Epistle to the Christians of Today | 21–26 May 1978 | Political | PS08 |

| 9 | Statement of Policies and/or Guidelines for Church-Related Institutions that are Incorporated as Judicial Entities of the General Assembly | 12–14 July 1979 | Political | PS09 |

| No. | Title | Publication Date | Category | * Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Our Commitment to Manifest God’s Kingdom Goes On: A Pastoral Statement on the Inauguration of President-Elect Ferdinand R. Marcos Jr. | 30 June 2022 | Political | PS10 |

| 2 | A Prayer-Statement on the 1st State of the Nation Address of President Ferdinand R. Marcos Jr. of the Council of Bishops | 25 July 2022 | Political | PS11 |

| 3 | Let Freedom, Justice, and Peace Blossom in our Minds and in Society, Uphold Human Dignity and Protect Human Rights | 21 September 2022 | Political | PS12 |

| 4 | Statement of Support United Church Workers Association West Visayas Jurisdiction | 21 September 2022 | Political | PS13 |

| 5 | Pastoral Admonition to the UCCP Faithful | 21 September 2022 | Political | PS14 |

| 6 | East Visayas Jurisdictional Area Statement on Red-Tagging of SWLC & NELBICON Church Workers | 24 September 2022 | Political | PS15 |

| 7 | A Pastoral Statement on Continuing Solidarity with Indigenous Peoples and in Celebration of the Reformation Month | 20 October 2022 | Political | PS16 |

| 8 | A Pastoral Statement in Commemoration of International Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and Celebration of Advent and Christmas | 10 December 2022 | Political | PS17 |

| 9 | Statement on the Harassment of Church Leaders and Members via Perjury Case and Red-Tagging | 31 January 2023 | Political | PS18 |

| 10 | An Ode to the Cry and Struggle for Decent Living Wages: International Labor Day | 1 May 2023 | Political | PS19 |

| 11 | Let Freedom, Justice, and Peace Reign in Our Land: A Pastoral Statement on the Commemoration of the 125th Philippine Independence | 12 June 2023 | Political | PS20 |

| 12 | Let the Truth be Head: A Pastoral Statement on Marcos Jr’s 2nd State of the Nation Address 2023 | 20 June 2023 | Political | PS21 |

| 13 | Statement of Solidarity: Stop the Attacks | 13 July 2024 | Political | PS22 |

| 14 | A Pastoral Statement on the Commemoration of the 51st Year of the Declaration of Martial Law in the Philippines | 21 September 2023 | Political | PS23 |

| 15 | A Call for Continuing Vigilance | 10 December 2023 | Political | PS24 |

| 16 | Steadfast in Faith, Unwavering in Prophetic Mission: A Pastoral Statement on the Commemoration of the 52nd Year of the Declaration of Martial Law in the Philippines | 19 September 2024 | Political | PS25 |

| 17 | In the Spirit of Faith and Solidarity: A Statement on the Observance of the Indigenous People’s Month | 17 October 2024 | Political | PS26 |

| 18 | Perseverance and Hope Amidst Persecution: A Pastoral Statement on the Release of Rev. Nathaniel Vallente | 30 October 2024 | Political | PS27 |

| 19 | Beyond Resilience: A Call for Accountability and Action in the Face of Disaster: Statement on the Series of Disasters and the Importance of Government Accountability | 2 November 2024 | Political | PS28 |

| 20 | The Chains Shall Break: A Church’s Persistent Call for the Immediate Release of Ptr. Jimie Teves Sr. and the Himalayan 7 | 16 November 2024 | Political | PS29 |

| 21 | Burning and Blazing Candles: A Prayer for May Jane Veloso, with Migrants and their Families | 18 December 2025 | Political | PS30 |

| 22 | A Pastoral Statement on Poverty, Corruption, and Injustice | 21 January 2025 | Political | PS31 |

| 23 | Mind the Lesson of EDSA People’s Power as you Cast Your Votes: A Pastoral Statement on the 39th Anniversary of the EDSA People Power Revolution in the Context of 12 May 2025 Midterm Elections | 24 February 2025 | Political | PS32 |

| 24 | Empowering Women, Arousing Change: UCCP Statement on International Women’s Day | 24 February 2025 | Political | PS33 |

| 25 | A Cry Heard and Answered: A Statement on the Arrest of Former President Rodrigo Duterte | 15 March 2025 | Political | PS34 |

| 26 | A Call to Justice: Statement on the 2025 Midterm Elections | 16 April 2025 | Political | PS35 |

| 27 | A Call to Righteous Leadership: A Unity Statement of UCCP United Metropolis Church Recognized Organizations in the Midterm Elections | 26 April 2025 | Political | PS36 |

| Administration | Number of Documents | Number of Political Documents | Number of Political Documents Analyzed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marcos Sr. | 9 | 6 | 6 |

| Marcos Jr. | 27 | 27 | 27 |

| Total number | 36 | 33 | 33 |

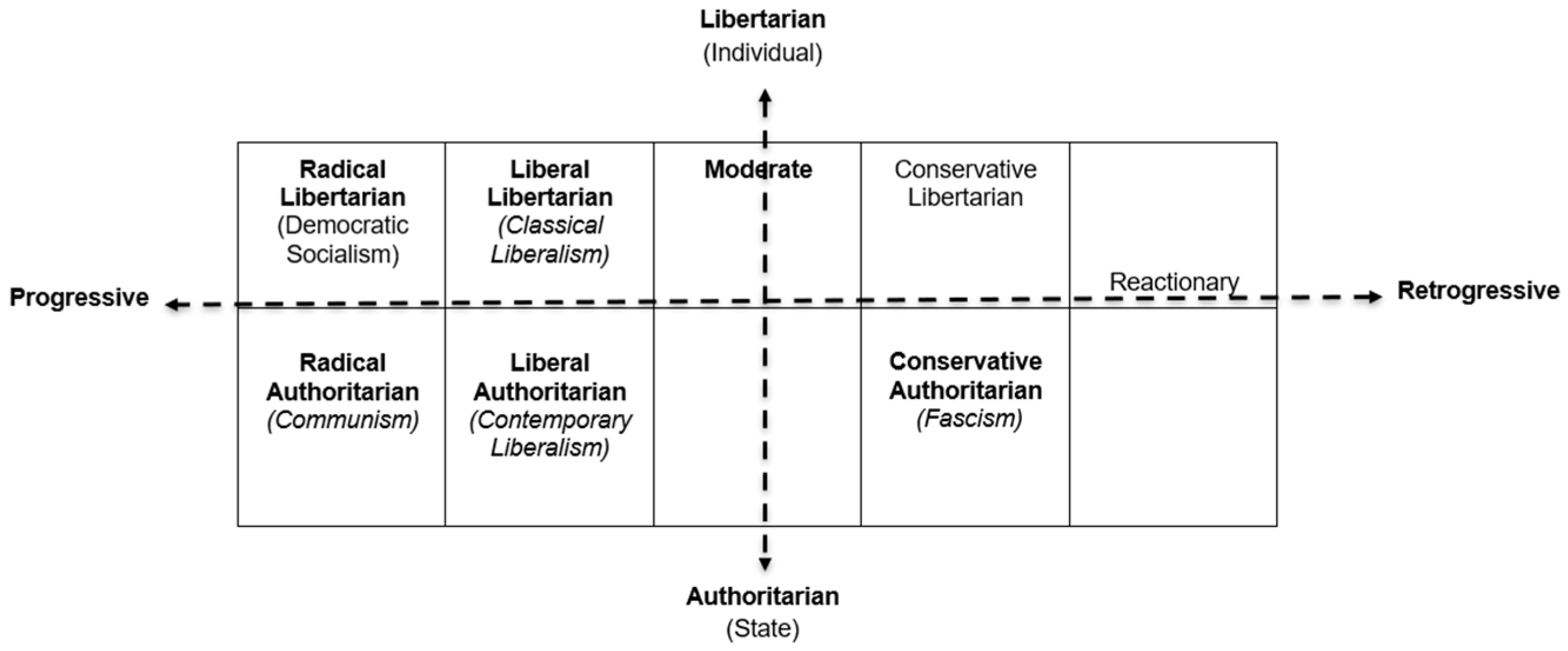

| Political Ideology | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Radical Libertarian | Favors rapid and profound progressive change while valuing freedom and the individual. | Democratic socialism based on Marxist thought where after the proletarian revolution, society is to be governed by a mass democracy. |

| 2. Radical Authoritarian | Favors rapid and profound progressive change while valuing social control and the state. | Communist ideology based on the Leninist interpretation of Marxist thought, where after the proletarian revolution, society is to be governed by a dictatorship. |

| 3. Liberal Libertarian | Favors calculated and controlled progressive change while valuing freedom and the individual. | Classical liberalism, which believes that the state oppresses individuals and thus its power and control must be limited. |

| 4. Liberal Authoritarian | Favors calculated and controlled progressive change while valuing social control and the state. | Contemporary liberalism, which holds that the state is still needed to regulate and organize individual activities and initiatives. |

| 5. Moderate | Strikes a balance between the need for change and the benefits of the current order. | |

| 6. Conservative Libertarian | Favors the current order while valuing freedom and the individual. | Ideology of right-leaning liberals in Europe and North America. |

| 7. Conservative Authoritarian | Favors the current order while valuing social control and the state. | Fascism, as a form of right-wing authoritarianism. |

| 8. Reactionary | Favors a retrogressive or backward-moving form of change. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gopez, C.P.; Cortez, M.N.; Alemania, B.B.M.; Demeterio, F.A., III. The Political Ideologies of the United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP) Under the Marcos Regimes. Religions 2025, 16, 1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091212

Gopez CP, Cortez MN, Alemania BBM, Demeterio FA III. The Political Ideologies of the United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP) Under the Marcos Regimes. Religions. 2025; 16(9):1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091212

Chicago/Turabian StyleGopez, Christian P., Marie_Valen N. Cortez, Belle Beatriex’ M. Alemania, and Feorillo A. Demeterio, III. 2025. "The Political Ideologies of the United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP) Under the Marcos Regimes" Religions 16, no. 9: 1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091212

APA StyleGopez, C. P., Cortez, M. N., Alemania, B. B. M., & Demeterio, F. A., III. (2025). The Political Ideologies of the United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP) Under the Marcos Regimes. Religions, 16(9), 1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091212