Hermeneutic Neurophenomenology in the Science-Religion Dialogue: Analysis of States of Consciousness in the Zohar

Abstract

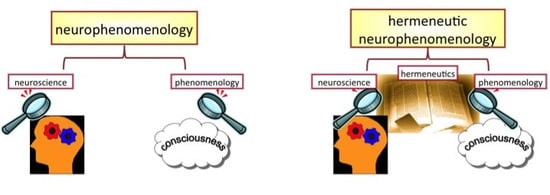

:1. Neurophenomenology and Hermeneutics

[E]xegesis, as understood by the world’s mystical communities, by the world’s mystical personalities, is a way of learning theurgical practices that can influence God or the Ultimate; a primary form, a main channel, of mystical ascent; a basic source of spiritual energy; a performative mystical act with salient experiential—transformational—consequences; a way of defining one’s mystical path; and a way to meet and interact with God or the Ultimates(s).[18], p. 57. Italics added

“O God, You are my God, I search for You [ashaḥareka]” (Psalm 63:2) … I will enhance the light that shines at dawn [be-shaḥaruta], for the light that abides at dawn does not shine until enhanced below. And whoever enhances this dawn light, although it is black, attains a shining white light; and this is the light of the speculum that shines. Such a person attains the world that is coming.This is the mystery of the verse “and those who seek Me [u-meshaḥarai] will find Me” (Proverbs 8:17); U-meshaḥarai—those who enhance the black light (meshaḥara) of dawn.

This passage outlines the nature and process of the mystical path. The maskil, wise of heart, “arrays” [cf. “enhances”] the black light of dawn, and in so doing ascends to the state of consciousness known as the “speculum that does not shine”—the dimension of the sefirah Malkhut. Working within this dimension he attains and ascends to a higher level—the “speculum that shines”, the symbol of the sefirah Tiferet.[31], p. 84

2. Mystical States of Consciousness as Conveyed by the Zohar

This is the light of the sun, the light of Torah, the King seated on His throne, the truth, the light of day, the center, the heart, the center bar [of the Tabernacle] running from end to end, the firmament, and the radiant light like which the enlightened wish to shine. Generally speaking, this light is associated with stability and majesty.[31], p. 269

3. Cognitive Neuroscience and States of Consciousness Depicted in the Zohar

3.1. Hermeneutic Neurophenomenology in the Modelling of Mind

- The first step is to clarify some of the key characteristics of the normal sate of consciousness and the neurocognitive processes that are thought to correlate with them.

- Following this I shall consider the ways in which the features of mystical states as portrayed in the Zohar suggest how these key characteristics, and their neural correlates, may become altered.

- Finally, I shall develop a model of the states of consciousness which incorporates material from the above two steps. This final step in the argument is intended to demonstrate the value for cognitive neuroscience of incorporating insights form mysticism more generally. These insights can enrich our scientific models, and perhaps suggest new avenues of enquiry.

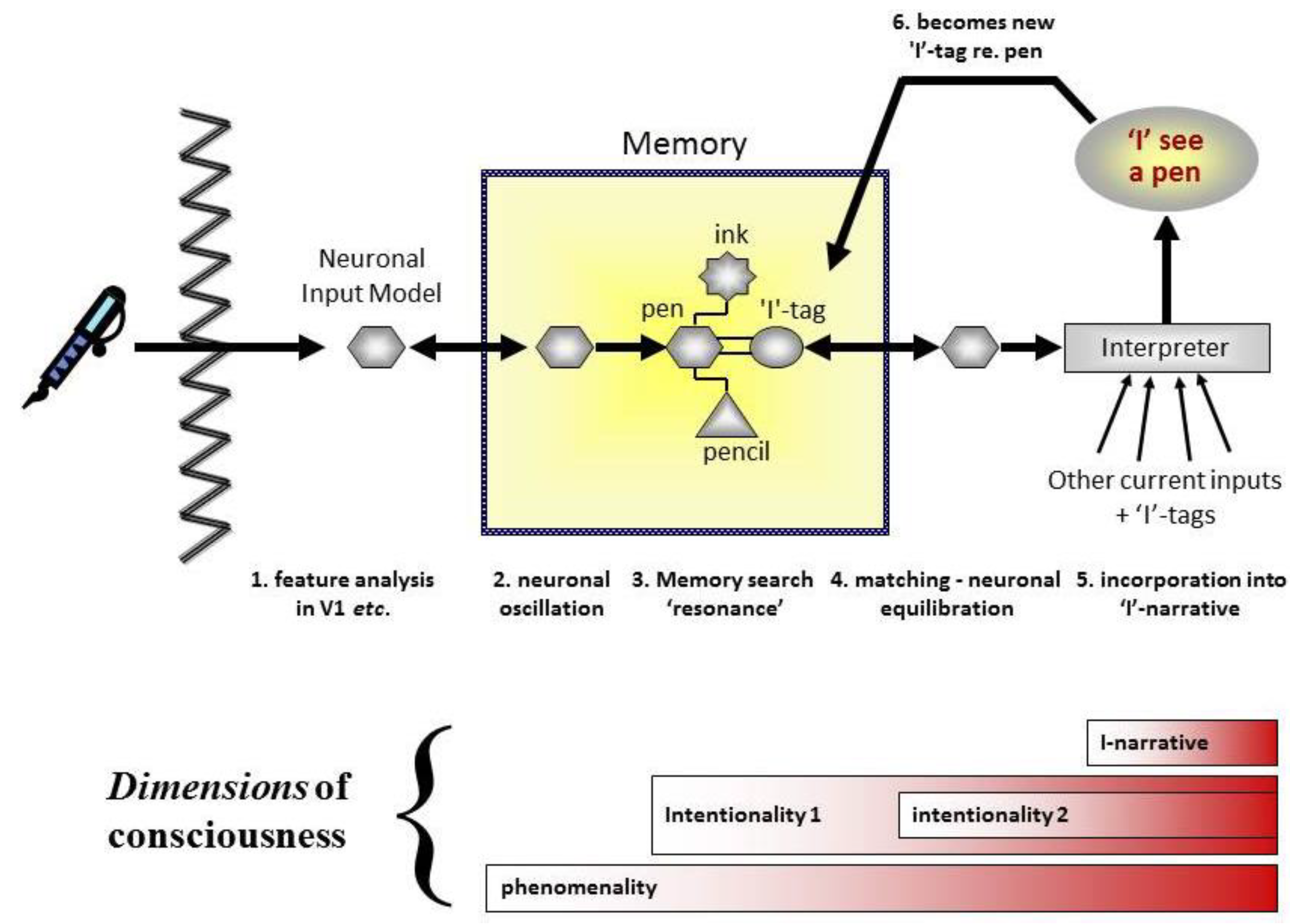

3.2. The Normal State of Consciousness

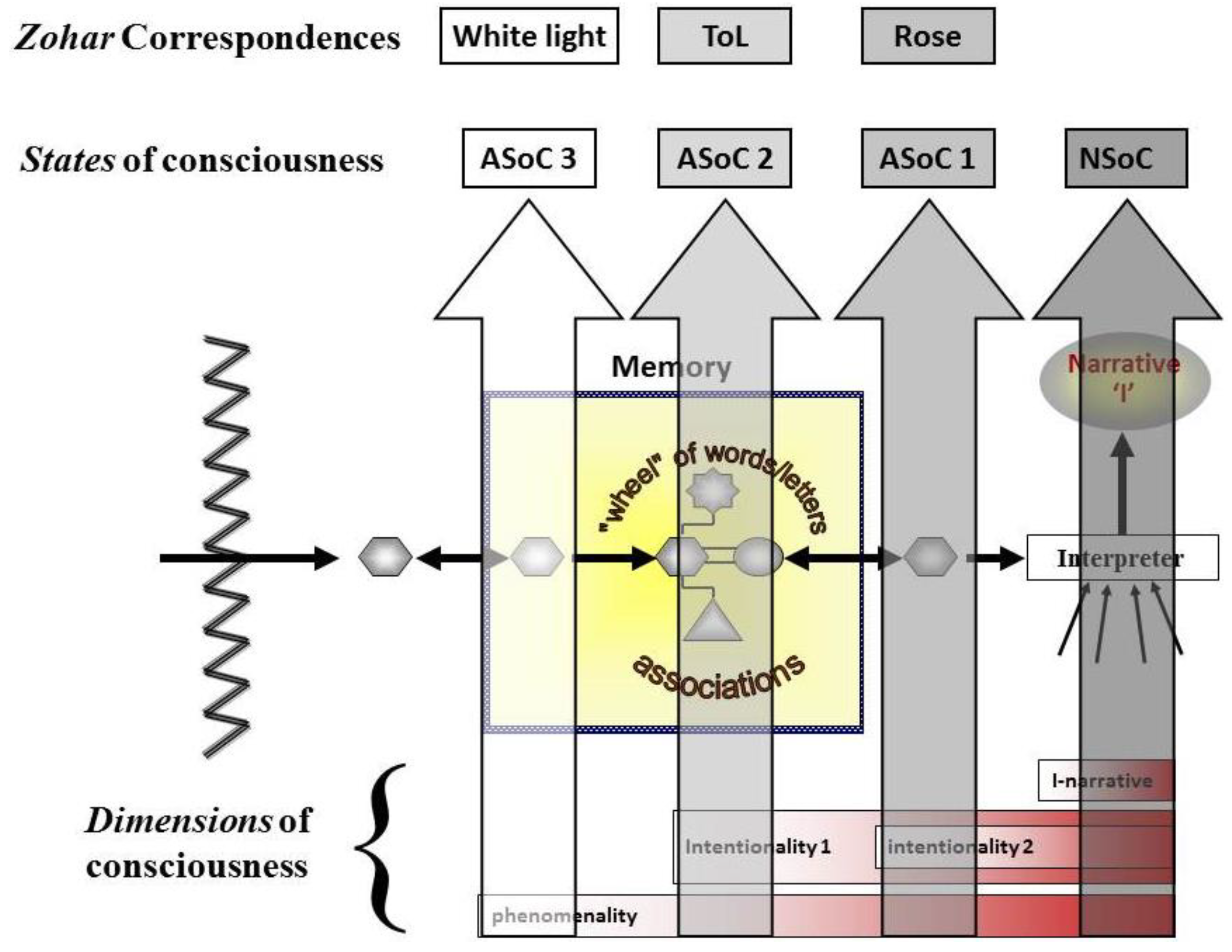

3.3. States of Consciousness in the Zohar and Neurocognitive Processes

3.4. Towards a Model of States of Consciousness

4. Conclusions

Abbreviations

| NSoC | Normal state of consciousness |

| ASoC | Altered state of consciousness |

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Francisco J. Varela. “Neurophenomenology: A methodological remedy for the hard problem.” Journal of Consciousness Studies 3 (1996): 330–49. [Google Scholar]

- Antoine Lutz, and Evan Thompson. “Neurophenomenology: Integrating subjective experience and brain dynamics in the neuroscience of consciousness.” Journal of Consciousness Studies 10 (2003): 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Antoine Lutz, John D. Dunne, and Richard J. Davidson. “Meditation and the neuroscience of consciousness.” In The Cambridge Handbook of Consciousness. Edited by Philip D. Zelazo, Morris Moscovitch and Evan Thompson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007, pp. 499–555. [Google Scholar]

- Evan Thompson. “Neurophenomenology and contemplative experience.” In The Oxford Handbook of Science and Religion. Edited by Philip Clayton. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 226–35. [Google Scholar]

- “Mind and Life Institute.” Available online: http://www.mindandlife.org/ (accessed on 28 January 2015).

- Jesse Edwards, Julio Peres, Daniel A. Monti, and Andrew B. Newberg. “The neurobiological correlates of meditation and mindfulness.” In Exploring Frontiers of the Mind-Brain Relationship. Edited by Alexander Moreira-Almeida and Franklin Santana Santos. New York: Springer, 2012, pp. 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Antoine Lutz, Heleen A. Slagter, John D. Dunne, and Richard J. Davidson. “Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 12 (2008): 163–69. [Google Scholar]

- Katya Rubia. “The neurobiology of meditation and its clinical effectiveness in psychiatric disorders.” Biological Psychology 82 (2009): 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Peter Malinowski. “Neural mechanisms of attentional control in mindfulness meditation.” Frontiers in Neuroscience 7 (2013): 8. [Google Scholar]

- Paul Grossman, Ludger Niemann, Stefan Schmidt, and Harald Walach. “Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis.” Journal of Psychosomatic Research 57 (2004): 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Shian-Ling Keng, Moria J. Smoski, and Clive J. Robins. “Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: A review of empirical studies.” Clinical Psychology Review 31 (2011): 1041–56. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob Piet, Hanne Würtzen, and Robert Zachariae. “The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on symptoms of anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients and survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 80 (2012): 1007–20. [Google Scholar]

- Geoffrey Samuel. “Between Buddhism and science, between mind and body.” Religions 5 (2014): 560–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rahul Banerjee. “Buddha and the bridging relations.” Progress in Brain Research 168 (2007): 255–62. [Google Scholar]

- Georgea Dreyfus, and Evan Thompson. “Asian Perspectives: Indian Theories of Mind.” In The Cambridge Handbook of Consciousness. Edited by Philip Zelazo, Morris Moscovitsch and Evan Thompson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007, pp. 89–114. [Google Scholar]

- Brian L. Lancaster. “On the stages of perception: Towards a synthesis of cognitive neuroscience and the Buddhist Abhidhamma tradition.” Journal of Consciousness Studies 4 (1997): 122–42. [Google Scholar]

- Brian L. Lancaster. Approaches to Consciousness: The Marriage of Science and Mysticism, 2004.

- Steven T. Katz. Mysticism and Sacred Scripture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel Boyarin. “The eye in the Torah: Ocular desire in Midrashic hermeneutic.” Critical Inquiry, 1990, 532–50. [Google Scholar]

- Moshe Idel. Enchanted Chains: Techniques and Rituals in Jewish Mysticism. Los Angeles: Cherub Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shimon Shokek. Kabbalah and the Art of Being. London: Routledge, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot R. Wolfson. Through a Speculum that Shines: Vision and Imagination in Medieval Jewish Mysticism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Moshe Idel. Kabbalah: New Perspectives. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Moshe Idel. Absorbing Perfections: Kabbalah and Interpretation. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan Wolski. A Journey into the Zohar: An Introduction to the Book of Radiance. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- William James. The Varieties of Religious Experience. London: Fontana, 1960, First published 1902. [Google Scholar]

- Underhill Evelyn. Mysticism: A Study in the Nature and Development of Man’s Spiritual Consciousness. New York: E.P. Dutton and Company, 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Reuvein Margoliot, ed. Sefer Ha-Zohar. Jerusalem: Mosad ha-Rav Kook, 1978.

- Daniel C. Matt. The Zohar: Pritzker Edition. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004–2014. [Google Scholar]

- Henri Corbin. “The visionary dream in Islamic spirituality.” In The Dream and Human Societies. Edited by G.E. von Grunebaum and Roger Cailloi. London: Cambridge University Press, 1966, pp. 381–408. [Google Scholar]

- Melilah Hellner-Eshed. A River Flows from Eden: The Language of Mystical Experience in the Zohar. Translated by Nathan Wolski. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Eitan P. Fishbane. “The Zohar: Masterpiece of Jewish mysticism.” In Jewish Mysticism and Kabbalah: New Insights and Scholarship. Edited by Frederick E. Greenspahn. New York: New York University Press, 2011, pp. 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- “Midrash.” In Song of Songs Rabbah, Vilna edition. first published 1887.

- “Babylonian Talmud.” Eruvin.

- Moshe Idel. The Mystical Experience in Abraham Abulafia. Translated by Jonathan Chipman. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Brian L. Lancaster. “On the relationship between cognitive models and spiritual maps. Evidence from Hebrew language mysticism.” Journal of Consciousness Studies 7 (2000): 231–50. [Google Scholar]

- Robert R. Hoffman, Edward L. Cochran, and James M. Nead. “Cognitive metaphors in experimental psychology.” In Metaphors in the History of Psychology. Edited by David E. Leary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990, pp. 173–229. [Google Scholar]

- George Lakoff, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Brian L. Lancaster. “The hard problem revisited: From cognitive neuroscience to Kabbalah and back again.” In Neuroscience, Consciousness, and Spirituality. Edited by Harald Walach, Stefan Schmidt and Wayne B. Jonas. Heidelberg: Springer, 2011, pp. 229–52. [Google Scholar]

- Brian L. Lancaster. “Neuroscience and the transpersonal.” In The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Transpersonal Psychology. Edited by Harris Friedman and Glenn Hartelius. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2013, pp. 223–38. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot R. Wolfson. Language, Eros, Being: Kabbalistic Hermeneutics and Poetic Imagination. New York: Fordham University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew A. Fingelkurts, Alexander A. Fingelkurts, and Carlos F.H. Neves. “Phenomenological architecture of a mind and Operational Architectonics of the brain: the unified metastable continuum.” New Mathematics and Natural Computation 5 (2009): 221–44. [Google Scholar]

- Dieter Vaitl, Niels Birbaumer, John Gruzelier, Graham A. Jamieson, Boris Kotchoubey, Andrea Kübler, Ute Strehl, and et al. “Psychobiology of altered states of consciousness.” Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice 1 (2013): 2–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sanford L. Drob. Kabbalistic visions: CG Jung and Jewish Mysticism. New Orleans: Spring Journal Books, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jerome Bruner. “A narrative model of self‐construction.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 818 (1997): 145–61. [Google Scholar]

- Brian L. Lancaster. “The mytholoy of anatta: Bridging the East-West divide.” In The Authority of Experience: Readings on Buddhism and Psychology. Edited by John Pickering. Richmond: Curzon Press, 1997, pp. 173–202. [Google Scholar]

- Michael S. Gazzaniga. The Social Brain: Discovering the Networks of the Mind. New York: Basic Books, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Michael S. Gazzaniga. “Shifting gears: Seeking new approaches for mind/brain mechanisms.” Annual Review of Psychology 64 (2013): 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Jessica R. Andrews-Hanna. “The brain’s default network and its adaptive role in internal mentation.” The Neuroscientist 18 (2012): 251–70. [Google Scholar]

- Stanislas Dehaene, Jean-Pierre Changeux, Lionel Naccache, Jérôme Sackur, and Claire Sergent. “Conscious, preconscious, and subliminal processing: A testable taxonomy.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 10 (2006): 204–11. [Google Scholar]

- Victor A. F. Lamme, and Pieter R. Roelfsema. “The Distinct Modes of Vision Offered by Feedforward and Recurrent Processing.” Trends in Neurosciences 23 (2000): 571–79. [Google Scholar]

- Simon Van Gaal, and Victor A. F. Lamme. “Unconscious high-level information processing implication for neurobiological theories of consciousness.” The Neuroscientist 18 (2012): 287–301. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel L. Schacter, Peter C.-Y. Chiu, and Kevin N. Ochsner. “Implicit memory: A selective review.” Annual Review of Neuroscience 16 (1993): 159–82. [Google Scholar]

- John F. Kihlstrom. “The psychological unconscious and the self.” Experimental and Theoretical Studies of Consciousness, 1993, 147–67. [Google Scholar]

- John F. Kihlstrom. “Consciousness and me-ness.” Scientific Approaches to Consciousness, 1997, 451–68. [Google Scholar]

- Brian L. Lancaster. Mind, Brain and Human Potential: The Quest for an Understanding of Self. Shaftesbury, Dorset & Rockport: Element Books, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Charles T. Tart. “States of consciousness and state-specific sciences.” Science 176 (1972): 1203–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jonathan Garb. Shamanic Trance in Modern Kabbalah. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot R. Wolfson. “Abraham ben Samuel Abulafia and the prophetic Kabbalah.” In Jewish Mysticism and Kabbalah: New Insights and Scholarship. Edited by Frederick E. Greenspahn. New York: New York University Press, 2011, pp. 68–90. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel Abrams. The Book Bahir: An Edition Based on the Earliest Manuscripts. Los Angeles: Cherub Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ithamar Gruenwald. “A preliminary critical edition of Sefer. Yezira.” Israel Oriental Studies 1 (1971): 132–77. (In Hebrew)[Google Scholar]

- Elliot R. Wolfson. “Letter Symbolism and Merkavah Imagery in the Zohar.” In Alei Shefer: Studies in the Literature of Jewish Thought Presented to Rabbi Dr. Alexandre Safran. Edited by Moshe Hallamish. Ramat-Gan: Bar-Ilan Press, 1990, pp. 195–236, (English section). [Google Scholar]

- Moshe Idel. Language, Torah, and Hermeneutics in Abraham Abulafia. Edited by Albany M. Kallus. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Harris L. Friedman. “Transpersonal self-expansiveness as a scientific construct.” In The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Transpersonal Psychology. Edited by Harris Friedman and Glenn Hartelius. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2013, pp. 203–22. [Google Scholar]

- Harry T. Hunt. “A cognitive psychology of mystical and altered-state experience (Monograph Supplement 1-V58).” Perceptual and Motor Skills 58 (1984): 467–513. [Google Scholar]

- Matthew T. Kapstein. The Presence of Light: Divine Radiance and Religious Experience. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Robert K. Forman. The Problem of Pure Consciousness. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Steven T. Katz. Mysticism and Philosophical Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Steven T. Katz. Mysticism and Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Robert K. Forman. The Innate Capacity: Mysticism, Psychology, and Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo Chen, Ralph W. Hood Jr., Yang Lijun, and Paul J. Watson. “Mystical experience among Tibetan Buddhists: The common core thesis revisited.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50 (2011): 328–38. [Google Scholar]

- Philip R. Sullivan. “Contentless consciousness and information-processing theories of mind.” Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology 2 (1995): 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- David J. Chalmers. “Facing up to the problem of consciousness.” Journal of Consciousness Studies 2 (1995): 200–19. [Google Scholar]

- Imants Barušs, and Robert J. Moore. “Measurement of beliefs about consciousness and reality.” Psychological Reports 71 (1992): 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Imants Barušs. “What We Can Learn about Consciousness from Altered States of Consciousness? ” Journal of Consciousness Exploration & Research 3, 2012, 805–19. [Google Scholar]

- Edoardo Bisiach. “The (haunted) brain and consciousness.” In Consciousness in Contemporary Science. Edited by Anthony J. Marcel and Edoardo Bisiach. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988, pp. 101–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ned Block. “On a confusion about a function of consciousness.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 18 (1995): 227–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ned Block. “Two neural correlates of consciousness.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 9 (2005): 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Franz Brentano. Psychology from an Empirical Stand Point. Translated by Anots C. Rancurello, D.B. Terrell, and Linda McAlister. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1973, Original German edition first published 1874. [Google Scholar]

- Max Velmans. “When perception becomes conscious.” British Journal of Psychology 90 (1999): 543–66. [Google Scholar]

- Sigmund Freud. The Psychopathology of Everyday Life. Translated by Alan Tyson. London: Ernst Benn, 1966, Original German edition first published 1904. [Google Scholar]

- Andreas Mavromatis. Hypnogogia: The Unique State of Consciousness between Wakefulness and Sleep. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Carl Gustav Jung. “Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self.” Translated by R.F.C. Hull. In The Collected Works of C.G. Jung. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1959, vol. 9, Part 2. [Google Scholar]

- Michael Fishbane. The Midrashic. Imagination: Jewish Exegesis, Thought, and History. New York: State University of New York Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander A. Fingelkurts, and Andrew A. Fingelkurts. “Is our brain hardwired to produce God, or is our brain hardwired to perceive God? A systematic review on the role of the brain in mediating religious experience.” Cognitive Processing 10 (2009): 293–326. [Google Scholar]

- 1Details of the Mind and Life Institute and of their programs of research can be found on their website [5].

- 2Wolfson is writing here about the mystical experience of light, and therefore his interest lies with visionary experience. The point stands that more generally for the Jewish mystic, hermeneutics is intertwined with all forms of mystical experience

- 3It is worth noting in this context that the kabbalistic understanding of correspondence and isomorphism between different levels in the created hierarchy is in line with recent developments in dynamic neuroscience. Fingelkurts, Fingelkurts, and Neves have argued that phenomenal architecture of a mind and operational architectonics of the brain are intimately connected within a single integrated metastable continuum through functional isomorphism [42].

- 4The term “preconscious” is problematic inasmuch as these early processes are deemed to be imbued with certain dimensions of consciousness (see Section 3.3 below). To be more precise, they are pre- the normal state of consciousness to the extent that the normal state is dominated by the end stage of perceptual activity through which the I-narrative is generated. Issues of terminology in the study of consciousness are fraught with inconsistency, and my approach to identifying the different dimensions of consciousness in terms of operationalized processes in perception is intended to overcome at least some of the inconsistencies.

- 5There has been some debate in the scholarly literature on Jewish mysticism as to whether the approach of the fraternity of the Zohar was more theosophical-theurgic compared with other approaches that emphasized use of ecstatic practices [57]. The exegetical orientation of the Zohar is indeed primarily theosophical—meaning that its interest lies in the structure of the divine world—and theurgic—implying that it encourages ritual practices to bring about harmony within that world and between the divine and human realms. However, it is unlikely that those responsible for its authorship had no experience of ecstatic practices. On the contrary, it is likely that a common core lies within the theosophical-theurgic Kabbalah of the Zohar and the so-called ecstatic Kabbalah that focuses on techniques for attaining higher, individual states. As Wolfson notes, the view that polarizes these two strands “fails to take seriously the many shared doctrines that may be traced to a common wellspring of esoteric tradition with much older roots” ([59], p. 85 n7). The intense intermingling of these strands in the Zohar is summed up by Hellner-Eshed: “In zoharic mysticism, theurgic ends serve as the vehicle for ecstatic experiences, while the ecstatic quest and the ecstatic experience serve theurgic ends” [31], p. 316).

- 6In using this phrase “deviations from the normal” I do not intend to convey any implication that the mystical states are not progressive or beneficial to the practitioner. It is simply that their potential value in the context I am examining here arises to the extent that they are deviations from the normal state of consciousness.

- 7This position, of course, begs the question concerning possible contentless consciousness. Whether or not such experience can be taken at face value, the NSoC is clearly identified not only by its focus on egocentricity (the I-narrative) but also by its intentionality. If there were to be a contentless state it would certainly not be a NSoC.

- 8In terms of classical classifications of spiritual and mystical practices, this formulation corresponds to the distinction between apophatic and kataphatic practices. Attenuation of processes involved in the I-narrative comes about through apophatic meditation directed towards stilling the mind, and augmentation of earlier processes entails kataphatic practices such as visualizations in which disciplined exploration of associations is encouraged.

- 9Throughout its history until recent times, the Kabbalah was very much a male preserve. The erotic storyline of the male kabbalist’s encounter with the Shekhinah forms one of the Zohar’s primary themes. To the extent that women in our day are increasingly entering into the world of the Kabbalah, this storyline is evolving. The psychological impact of this development is the subject for a future study. Here, my interest is focused on the states of consciousness in the male psyche, since this is the extent of the Zohar’s worldview.

- 10In my own case I might take this a stage further: My engagement with rabbinic hermeneutics and kabbalistic practices was instrumental in enabling me to incorporate research data from cognitive neuroscience into my formulation of the model presented over these pages and in my other works on this topic.

- 11As indicated earlier in my examination of the fit between the Zohar’s scheme and that of Underhill, this threefold division of mystical states would seem to be evident beyond the realm of Jewish mysticism. Such a conclusion would clearly lend further support to the neurocognitive model of states of consciousness presented here. However, a full analysis of mystical states across diverse religious systems is beyond the scope of my article.

© 2015 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lancaster, B.L. Hermeneutic Neurophenomenology in the Science-Religion Dialogue: Analysis of States of Consciousness in the Zohar. Religions 2015, 6, 146-171. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel6010146

Lancaster BL. Hermeneutic Neurophenomenology in the Science-Religion Dialogue: Analysis of States of Consciousness in the Zohar. Religions. 2015; 6(1):146-171. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel6010146

Chicago/Turabian StyleLancaster, Brian L. 2015. "Hermeneutic Neurophenomenology in the Science-Religion Dialogue: Analysis of States of Consciousness in the Zohar" Religions 6, no. 1: 146-171. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel6010146

APA StyleLancaster, B. L. (2015). Hermeneutic Neurophenomenology in the Science-Religion Dialogue: Analysis of States of Consciousness in the Zohar. Religions, 6(1), 146-171. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel6010146