2. Catholic Bishops in US Politics

Historically, Catholic bishops were less dependent on priests to complete the influence loop with parishioners. Prior to the Great Depression and New Deal, the locus of political power and decision-making was centered at the municipal or local government levels. Such local proximity enabled bishops to have a much more direct dealing with elected officials of consequence in creating and implementing policy. As such, bishops cultivated relationships with local politicians to affect policy change reflecting Catholic concerns. As the state and federal governments became more involved in housing, education, and social policy, however, the bishops had to shift their focus to reflect changes in the federalism dynamic [

3]. This included an emphasis on the lobbying activities by state-level Catholic conferences [

4], and working through the bishops’ collective national presence as the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB), also known as the Bishops Conference.

Though abortion has been a high priority for the Bishops Conference [

5], the Church’s public theology informs concern on a host of issues ranging from poverty to immigration [

6], thereby providing the bishops with a full palate of policy concerns to address. Aggregating government policy development up to the state and federal levels increased the number of opposing voices (both Catholic and non-Catholic) wanting to bend political outcomes toward their preferences. It also meant that close relationships between bishops and elected officials—based on the shared proximity of an earlier political era—were no longer effective. As such, bishop reliance on Catholic parishioners to vote on behalf of Church policy preferences became a necessity by the latter half of the twentieth century.

In addition to the question of whether clergy effectively influence parishioners on political issues, a recurring challenge for ensuring bishop political influence through parishioner action has been the decided lack of parishioner cohesion in their political views [

7]. Part of the complication is that, with the breakdown of the New Deal coalition, both Republicans and Democrats have prioritized Catholic voter outreach, with each party focusing on issues it believes best resonate with Church concerns. The result has been the creation of a Catholic “swing vote” in elections since 1960 [

8,

9]. Catholic parishioners can be forgiven somewhat for their partisan ambiguity, as the bishops’ articulated policy positions do not align neatly with the American party system.

Even if the Catholic political landscape was not so complex, it is not a given that bishops would easily compel parishioners to vote in support of Catholic policy concerns. This is because priests, who are usually directed by the bishops on political matters (at least officially), enjoy only variable and inconsistent political influence over their parishioners [

1]. For example, scholars have noted that priests affect parishioner views on capital punishment [

10], but not abortion [

11]. This may be why even priests willing to follow their bishop’s political cues do not readily close the influence loop between bishops and parishioners. Still, finding evidence that priests are receptive to bishop instruction, and that this receptiveness has some effect on priest political behavior, would help to demonstrate that bishops have a command of institutional resources in attempting to sway parishioner opinion.

We pose two central research questions in this article: what leads priests to look to their institutional superiors for professional guidance (i.e., cues), including, presumably, their decision to undertake political activity? The answer to this question is not self-evident, even though a bishop effectively functions as the local boss for priests in his diocese. This is because the priesthood’s professional realties—including the frequent and direct contact priests have with parishioners—opens up an array of alternate sources of influence on priest political behavior beyond the bishop. Our second question flows from the first: assuming that priests rely on their bishops for professional guidance (cues), does this guidance translate into a direct impact on priest political behavior?

3. Clergy Psychology

Determining how priests and other clergy think and behave politically has been a long-standing interest of scholars. Ideological [

12,

13], institutional [

14], personal [

15], and contextual factors [

2,

16] have played prominent roles in explaining the clergy politics puzzle. However, despite the rather apparent psychological dimension inherent in the clergy’s professional responsibilities (given the demands and credentials required in their work [

17]), scholars have been slow to add a psychological lens to assessments of clergy professional identity and its effects on political outcomes (although, see [

18]). We contend that the psychology of professional identity is essential in modeling clergy behavior because one’s professional sense of self motivates work-based behavior [

19,

20]. The psychological lens is linked to the variability of professional contexts and expectations that clergy encounter, and this lens may be considered in at least two ways. The first draws on different representations of clergy in their professional roles as meted through institutional pressures [

21], and may be considered an extension of the institutionally based study of clergy. The second is more interpersonal in nature, and deals with the potential burnout that clergy feel stemming from their ministry with parishioners [

22].

The thought process and relevant constituencies associated with clergy professional roles are not necessarily uniform. Each duty, from representing their denomination’s views to regular interaction with parishioners, elevates certain professional contexts in clergy thinking. As Calfano shows [

23,

24], these professional contexts are tied to constituencies that clergy interact with at regular intervals. These constituencies, which, for Catholic priests include parishioners and bishops, function as reference groups on whose cues priests may select in determining their political behavior.

Priests are ripe for reference group influence because, like other professionals, they can be reasonably considered to have high acceptance of and identification with their organization’s

raison d’etre [

25,

26]. Yet it is this commitment that also likely makes navigating their professional contexts somewhat challenging [

27]. After all, priests are dedicated to serving the needs of their parishioners within the framework established, in part, by the bishops. To the extent that parishioners and bishops are not of the same thinking on theological, social, and political matters, priests may be forced to differentiate between a commitment made to their Church as an institution (represented by the bishops and Church teaching) and a commitment to a certain style of job performance that emphasizes interpersonal or “people” work [

28]. We suspect that reflection on specific reference groups conjures different representations of priest commitment to the Church and their professional identity. Group reflection may even go so far as to divide internal and external motivations for priests, with the latter having more to do with institutional compliance and the latter with components of self- expression and social service [

29]. The relative cognitive salience of these reference groups in clergy thinking, therefore, may be a critical component in understanding how clergy view themselves and their professional identity.

Of course, the notion of reference group influence on clergy political behavior is not new. Campbell and Pettigrew [

30], for example, examined clergy behavior according to personal, professional (denominational), and congregational dimensions, which Djupe and Gilbert [

31] expanded to include community interests. Meanwhile, work by Hadden [

32] and Quinley [

33] affirmed that parishioners have significant sway on clergy behavior. Overall, reference groups appear to both encourage and discourage clergy behavior at times, with specific groups potentially having countervailing influences. Given that parish clergy encounter their parishioners with greater frequency than do their denominational superiors (e.g., bishops), there is a logical expectation that the local congregation has a greater degree of influence on clergy. Yet Ammerman’s [

34] work suggests that clergy may overcome attempts at local control by looking to reference groups beyond parishioner enclaves, and this may be particularly true in denominations with clearly developed lines of authority beyond the local congregation.

This discussion raises some of the complexities at work in the assessment of bishop political influence: though bishops need priests to represent Church-wide policy political preferences to parishioners, the literature shows that priest-to-parishioner influence is not one-directional. What is more, both bishops and parishioners may influence priests in countervailing ways, and it is not yet clear that priests favor their bishops in this process, despite having some reason to do so per Ammerman’s [

34] argument. The reference group dynamic may be especially prevalent for clergy in denominations such as the Roman Catholic Church—where heterogeneity of theological and political preferences among parishioners is the norm, local finances are dwindling, and there are clear opinion differences between parishioners and denominational leaders [

35]. There are also likely to be different contextual representations at work in clergy interaction with their parishioners and bishops, as these reference groups reflect different aspects of priest professional identity (

i.e., the institutional and interpersonal).

We treat the reference groups that clergy encounter as institutionally embedded, psychological influences [

36]. This means, in part, that a group’s institutional location, authority, and/or expectations of service by the clergy contribute to its level of influence. Borrowing broadly from social exchange theory [

37], we expect that clergy are subject to influence from key reference groups representing distinct constituencies of professional relevance, with both having specific sanctions and rewards to wield. Indeed, even though priests are technically leaders of their local parishes—suggesting a tie-in with leader-member exchange theory [

38], priests are, in actuality, elites in voluntary organizations. As such, there is a continued pressure on clergy to lead, but to do so in a way that avoids negative reactions from their prime reference groups. These include sanctions such as leaving the parish or reducing monetary giving (by parishioners) or reprimand and suspension (by bishops).

We theorize that priests have the freedom of choosing the reference group to which they will respond, given that they serve in a complex organizational structure. If clergy behave like rational actors, specific goal orientations are likely behind their decision to rely on certain cues at different times. The relative degree of cognitive attention given to a goal or group likely determines whether that goal or group actively influences priest thinking and behavior at a given time. As such, and akin to a basic goal priming exercise (see [

39]), priests may respond differently when certain goals (and the professional identities, challenges, and payoffs that accompany them) are cognitively highlighted over others.

Based on the goal identity priming approach, we assess whether randomly heightening different frameworks of clergy professional identity affects clergy responses to questions ranging from their reliance on cues regarding professional activities, their perception of religious institutions, and their self-reported frequency of political behavior. The focus here on cue reliance and reported political behavior is fairly self-evident given that our goal is to test for bishop influence on priests. Questioning priests about their perception of religious institutions is also useful in that it sheds light on the extent to which highlighting different representations of priest professional identity affects their stated view of the institutions to which they are committed.

Apart from reference group interplay, and owing to the more psychological aspects of priest identity, parishioners may have an entirely separate effect on priests that is not represented by questions over parish finances, political positioning, and Church teaching, but, rather, reflects the day-to-day stress and fatigue in ministering to people [

40,

41] (but see also [

42]). If priests are exhausted in their ministry, and reflect on this fact when considering the nature of their religious institution, bishops, and political activity, these priests may come to very different representations of their political opinion and activity than if the financial pressures and expectations associated with their core reference groups alone are highlighted. This is why we elect to separate representation of these two characterizations of clergy identity (and highlighted reference groups) in our study.

4. Priming Priests

Our evaluation of priest responses to their bishops is in the form of a randomized survey experiment, and is based on the same underlying principle of Zaller’s [

43] model of survey response: people formulate answers to questions based on the considerations mentally available to them at the time the questions are asked. Though Zaller was focused on political opinion in the mass public, if one accepts the premise that priests confront a complex set of psychological considerations regarding their professional responsibilities and how to respond to reference groups that intersect with these responsibilities, then the idea that priests may express different responses to survey questions based on which of these considerations are active in their thinking at a given time should be seen as a plausible extension of Zaller’s model. Of course, this view runs counter to some of the expectations Zaller had himself regarding elites and opinion influence via media. Assuming that priests function as elites, the more classic view of these local leaders is to consider them nodes of influence on the mass public [

12,

13,

44]. We do not seek to overturn the notion that clergy are influential in their ministries and help to sway public opinion (despite the lack of direct causal evidence demonstrating this effect), as this is not our argument. Instead, our expectation is that clergy are subject to different ways of thinking about their profession and the people they encounter in it (including their bishops). By encouraging priests to think about their professional roles and identity in specific ways at a given time, we look to show an effect on clergy reported political attitudes and behavior (with a particular emphasis on the role of bishop cues in the process).

In conducting this assessment, we use a question order experiment. Our treatments were randomly assigned sets of four survey questions, which we label as primes. The idea behind a question order experiment is that positioning the questions intended as primes early in the question order for some randomly selected subjects (and not others) allows for a comparison of difference in response to follow-on survey questions (which serve as outcome variables in our analysis). Our

Institutional Prime includes questions that heighten reflection on parishioner expectations as juxtaposed with bishop expectations, parish financial concerns, and anticipated parishioner reaction to clergy behavior. To provide a contrast with any institutional reference group effect, we use a second prime that raises clergy consideration of perceived stress, fatigue, exhilaration, and level of care about their interactions with parishioners as developed by Francis

et al. [

45]. In this

Interpersonal Prime, parishioner/priest interactions from a ministerial perspective are the clear focus—the larger institutional and multiple reference group tensions are removed. In order to evaluate whether the act of priming priests had an effect on their survey response beyond any differences between the two primes themselves, our design also includes a control group of subjects who were randomly assigned not to receive any of the Interpersonal or Institutional questions as primes.

Note that we do not use actual responses to the priming questions in our analysis—the act of reading, considering, and responding to the survey questions is intended to activate priest thinking about specific aspect of one’s professional identity. That said, responses to the priming items do reflect underlying patterns, as found in a polychoric factor analysis of both primes.

Table 1 contains the items used as our institutional prime (with a rotated polychoric factor eigenvalue of 1.31), as well Francis

et al. [

45] items (which has a rotated polychoric factor eigenvalue of 1.18).

The idea behind including the control subject group is to capture a baseline sense of priest thinking about their professional identities and reference groups without being asked about them. Any statistical effect we discover from the primes, therefore, will indicate that priest survey response has moved from this baseline. In terms of anticipated impact from the assigned primes, we expect that priests exposed to the reference group expectations in the Institutional Prime will be more likely to (1) seek professional cues from their bishops; (2) disagree with negative characterizations of religious institutions; and (3) report higher frequencies of political behavior. Each of these outcomes is generally in keeping with responsiveness to their bishops and conscientiousness in ministering to their parishioners, and is based on the underlying logic of reference group influence on clergy.

We expect that priests exposed to the questions about professional burnout and exhilaration in the Interpersonal Prime will be less likely to view institutional reference groups consequentially. This is for at least two reasons. First, and most obviously, the focus of the Interpersonal Prime is on the priest-parishioner relationship and does not reference bishops. Second, the prime questions pertain to underlying dimensions of job satisfaction that require priests to ponder their professional identity from a much more personal vantage point than either the Institutional Prime questions or the control condition encourages. Indeed, asking about a priest’s sense of fatigue and exhilaration related to their job should move their mental consideration away from the calculations of reference group expectations and related items. Of course, one might also argue the opposite: reference group expectations may be the source of fatigue and/or exhilaration, and asking about these psychological items may move clergy in the same direction as the Institutional Prime. The advantage of our experimental design is that we will be able to directly test for any such countervailing outcome related to the primes.

Our original survey experiment was conducted in November and December 2014, based on an email list of 4133 parish/pastoral priests in the US Roman Catholic Church, procured from a private vendor. We invited the entire list via email to serve as subjects in our online survey hosted by Qualtrics. Using the Qualtrics algorithm, we randomly assigned 614 consenting clergy subjects to one of the three experimental groups, receiving 555 useable [

46] survey responses after the four-week response period concluded. Similar to Jerit, Barabas, and Clifford’s [

47] design, the Qualtrics algorithm conducted random assignment once subjects clicked on the embedded link within their invitation email. 184 subjects were assigned the Interpersonal Prime, 187 received the Institutional Prime, and 185 were placed in the control group (estimated power = 0.88 at

p < 0.01). Per standard question order experiment construction, all subjects were asked to respond to all survey questions—only the question order was manipulated. Subjects in the control group received both treatment primes at the end of the survey (with the end-of-survey order of the primes set at random).

Table 2 reports basic descriptive about our subject pool. Though our subjects exhibit ideological and age characteristics close to what Jelen [

12] found in his national priest survey, we do not claim our subject pool to be demographically representative of the US Catholic priest population.

5. Clergy Cue Use, Perceptions, and Behavior

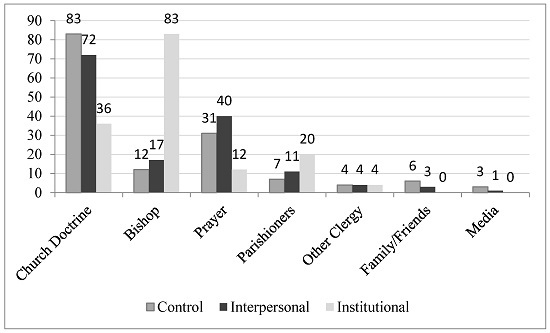

Owing to our theory about reference group influence on priests, our initial question of interest concerns priest self-reports of cue reliance from a list of likely sources. As part of the survey instrument, priest subjects were invited to list, in order, the various groups/entities/practices on which they rely for guidance in discharging their professional responsibilities. Options included: bishops, parishioners, prayer, Church doctrine, other clergy, friends and family, the media, and an “other” category. In the analysis that follows, we focus on comparing the self-reported first choice for cue use that priests indicated in their survey responses.

Figure 1 depicts the frequency distribution of the self-reported cue choices (excluding the “other” category) by priming treatment. It is clear that our priest subjects prefer Church doctrine as their primary cue source (191 subjects). That being said, bishops are the first cue choice of 112 subjects, suggesting that these institutional superiors are regularly on the minds of parish priests overall. By contrast, only 38 subjects listed parishioners as their first cue choice (although this far outpaces the twelve who indicated that other clergy are their first cue choice).

The cue selection is somewhat different when examining priest self-reports according to their assigned primes. Among the subjects randomly exposed to the Interpersonal Prime, Church doctrine is the most frequently indicated first cue choice (72 subjects). However, rather than look to bishops as the second most frequent cue source, “prayer” was actually the second most relied on cue among those encountering the Interpersonal Prime (40 subjects). This finding is in line with the expectation that referencing clergy fatigue in the prime reduces priest attention to reference groups and associated concerns.

The distribution for those receiving the Institutional Prime is substantially different. Rather than Church doctrine, bishops are the most frequently selected first choice among cue gives (83 subjects), followed by Church doctrine (36 subjects). For their part as an alternate reference group, parishioners were the first choice of 20 subjects receiving the Institutional Prime. Though seen only in descriptive difference terms at this point, it is clear that Institutional Prime subjects are much more concerned with cues from their bishops than other contextual reference groups and sources. This helps to further contrast Institutional from Interpersonal Prime effects on clergy response, while also demonstrating that, of their two most consequential reference groups as established by the literature, there is a clear preference for bishop—not parishioner—cues as a first selection. Whether this preference bodes well for bishop influence on priests is a question we take up in our statistical analysis in the following sections. For the sake of comparison, 12 of the 185 control group priests indicated that they look to their bishops for cues while 83 named Church doctrine as their first cue preference—clearly indicating that encouraging priests to focus on reference group expectations shifts preferred cue reliance away from doctrine.

Table 3 contains our first set of statistical tests, and focuses on cue selection across the categories from which priests could select on the survey instrument. We use a multinomial logit model to measure the effect of the assigned treatment primes on subjects’ first preference for a cue source, with the “other” category excluded. Popular control variables in the clergy politics literature include age, political party, ideology, congregational size, and type of area where a parish is located were included. However, we found no correlation between random treatment assignment and these correlates, suggesting that the random assignment of the primes was successful. This also suggests that the inclusion of controls is unnecessary in testing for the direct effect of the treatment primes on cue selection across subjects.

To help interpret the statistically significant coefficients in the model, we report the difference between the minimum and maximum predicted probability value as a specific treatment moves from 0–1, holding the other treatment and control groups at their means. As seen in

Table 3, subject exposure to Institutional Prime shows a significant effect on selection of both Church doctrine and bishops as preferred cues, but the prime has a varied influence. Specifically, subjects exposed to the Institutional Prime are 0.26 less likely to report turning first to Church doctrine for cues in discharging their professional responsibilities. Meanwhile, reflecting our expectations, those exposed to the Institutional Prime are 0.39 more likely to name their bishops as their first cue source. Though the prime also moved subjects toward indicating that they look to parishioner cues first (probability increase of 0.065), this effect was just outside our accepted significance threshold. Most interesting about these findings, given the weaker effect found for parishioner cue selection, is that the Institutional Prime questions were not centered exclusively on the Catholic bishops. This suggests is that, while priests are likely concerned with their parishioners to some extent, cognitively highlighting one’s professional identity in an institutionally centered way places the bishops at the center of priest thinking somewhat at the expense of parishioners.

Somewhat contrary to our expectations, subject exposure to the Interpersonal Prime had no effect on clergy cue preference. Recall that we expected institutional reference groups to be less consequential when burnout and related items were primed in subject thinking. The finding instead suggests that reflection on burnout and related items may take focus off of reference group expectations entirely, leading to the question of whether priests exposed to these self-reflection items begin to lose interest in their professional identity in a general sense. From a different vantage point, the lack of significance for the Interpersonal Prime could be seen as a sign of greater independence from institutional reference groups, which, while not necessarily a bad thing for priests, does not bode well for the strength of bishop influence over their subordinates. In our estimation, it is more likely that the null effect indicates that clergy who think about burnout are generally (if temporarily) stunted in considering their professional identities and attendant responsibilities. This is because, by comparison, even control group subjects—who are significantly likely to eschew all reference groups cues per

Table 3—were found to significantly prefer Church doctrine as their “go to” cue (probability increase of 0.19). The relative response from control group subjects suggests that the null finding for the Interpersonal Prime is part of a larger professional disengagement among priests that derives from cognitive focus on questions about the interpersonal aspects of ministry, as Francis

et al. [

45] largely expected.

From this initial round of findings, we can tentatively conclude that priests are concerned enough about what their bishops think about their professional performance that bishop cues are the first choice among competing sources for priests when asked to focus on their job’s institutional realties. This helps lay the groundwork for an argument that bishops influence priest behavior, though we are not yet at the point of linking cue taking to actual action on the part of priests. At the time same time, the multinomial logit results underscore the reality that priests do not, as a matter of default, look to their bishops for cues on professional behavior. It is only when institutional realities are highlighted through questions in our Institutional Prime that we see a clear preference for bishop cues over other sources. In general, priests are much more likely to consider Church doctrine their preferred cue source unless presented with queries about their parishioner and bishop reference groups.

Our second outcome measure focuses on priest perceptions of religious institutions. The rationale for using this topic as a dependent variable stems from the notion that focusing on the realities of one’s professional identity from different vantage points will impact how priests feel about religious institutions. Though we did not name the Roman Catholic Church in these questions to avoid impression management and other response bias concerns, it is reasonable to expect that subjects made some cognitive association between the general “institutions” reference and their actual denomination. Priest perceptions were captured in series of responses to question statements about institutions, including: “religious institutions have too much power”, “religious institutions have too many rules”; and “religious institutions are focused too much on politics”. Each statement response was scored 0–10, with higher scale values representing greater agreement with a statement, and thereby expressing a more negative view of religious institutions. As might be expected with a large subject sample, mean responses are generally at the scale midpoints: “too much power” (5.52, SD = 3.03), “too many rules” (5.85, SD = 2.60), and “too much on politics” (5.00, SD = 2.81). The three questions loaded on a single factor with a rotated polychoric factor eigenvalue of 1.32. Given this, we generated an Institutional Perception Index from the question responses for use as our dependent variable.

As with the cue reliance indicators in the multinomial logit model, we want to first see if the randomly assigned primes made a statistical difference in how priests responded without the use of statistical controls. Since our outcome variable in this instance is an index score rather than a categorical selection, we are able to conduct a simple means test using Tukey’s highly significant difference measure for post-hoc comparisons of control group index scores to each of the two treatments. Results are reported in

Table 4. Our expectation was that effects from the Institutional Prime would decrease negative perceptions of religious institutions, but the exact opposite is the case. The significant Tukey score is between the control group and the Institutional Prime, as subjects encountering the reference group-based questions had an index mean score of 7.10 (

versus 4.51 for the control, while the Interpersonal Prime mean of 4.66 was statistically indistinguishable from the control). This shows that subjects exposed to the institutions-based frame of reference group expectations were spurred to report a more negative perception of religious institutions (

p < 0.01) (presumably including the Roman Catholic Church).

That the index’s component questions mention rules, power, and political involvement, the finding of an increase in priest agreement with a negative institutional characterization suggests that the realities of responding to reference groups puts priests in a decidedly critical mindset about institutions of faith. Based on how our research design is constructed, it is not possible to say whether priests find a particular component of reference group expectations (or specific reference group) to be more objectionable than another. It is, however, interesting that the Interpersonal Prime, which only references priest interaction with parishioners, has no statistical effect on the Institutional Perception Index score versus the control group. This tends to suggest that priests are reacting to mention of their bishops in the Institutional Prime and/or the combined reference to bishop and parishioner expectations.

Unfortunately we cannot parse the Institutional Prime effect any further; however, and coupled with the previous finding of increased priest reliance on bishop cues when treated with the Institutional Prime, it is telling that the same prime would also increase priests’ negative perceptions of religious institutions. Does this raise the possibility that primed priests, while indicating a preference for bishop cues, end up resenting having to do so (at least to some extent)? We believe this is one possible interpretation of the Institutional Prime’s effect on the perception index, particularly if an observer adopts the view that priests (like other clergy) would prefer to operate as independent elites and outside of a constraining set of institutional circumstances. However, in comparing the treatment and control means across the three institutions items, it is clear that the Institutional Prime priests agreed most with the “religious institutions have too much power” statement (7.88 vs. 4.21 for control group priests, p < 0.01). Political involvement by religious institutions was comparatively less of a concern on the 0–10 scale (6.53 vs. 4.42 for control group priests, p < 0.01). Agreement with the notion that “religious institutions have too many rules”—which comes closest to capturing elements of the reference group dynamic—falls in the middle of the three index items (7.08 vs. 5.37 for control group priests, p < 0.01).

Though it is not unreasonable to link priests’ agreement with the “too much power” statement to those who wield considerable power in the Catholic Church (i.e., the bishops) it may also be that the institutionally primed priests are reacting to an entirely different set of issues in their evaluation (e.g., denominational officials’ involvement in secular political debates), rather than any objection by priests to following dictates from their institutional superiors. However, that only the priests in the Institutional Prime group had such a strong, negative reaction to the institutional perception items points to the bishops likely having something to do in triggering the reaction. Determining what this is certainly recommends itself as a topic for future research consideration.

The second outcome measure in

Table 4 (and our third overall) concerns priests’ self-reported political activities on a series of five items: (1) publicly praying on a political issue; (2) taking a public stand or position on a political issue; (3) taking a stand on a political issue during Mass; (4) encouraging parishioners to vote in an upcoming election; (5) and contacting an elected official. Overall, the priests in our sample report moderately high levels of political activity, with 68 percent giving a public prayer on a political issue “sometimes” or “often” (M = 2.76, SD = 0.972), 65 percent taking a public stand on a political issues sometimes or often (M = 2.70, SD = 0.936), 54 percent taking a stand on a political issue during Mass sometimes or often (M = 2.45, SD = 1.00), 89 percent encouraging their parishioners to vote sometimes or often (M =3.44, SD = 0.744), and 58 percent contacting elected officials at least sometimes or often (M = 2.59, SD = 0.884). These five political behavior items loaded on a single factor with a rotated polychoric factor eigenvalue of 1.75. As such, we created a Political Behavior Index score for use as our dependent variable.

In determining effects of the assigned treatments on index scores, we again used the Tukey difference measure between control group subjects and priests in each of the two treatment groups. As seen in

Table 4, the Institutional Prime’s Tukey value again indicates significant impact on subject response, this time in increasing their reported frequency of political behavior (

p < 0.01). Our argument is not that priests behave differently, but the way priests recollect and characterize their behavior is subject to priming effects. Overall, then, we can conclude that framing priest professional identity according to reference group expectations has a strong and consistent effect on how priests respond to political survey items. This is no mean feat. To our knowledge, it is the first time this direct causal effect has been demonstrated in the literature. As we theorized, motivating the primed priests may be the known expectations from their bishops in taking political positions on important issues for the Church (although our measures do not provide issue-specific information to know this for certain). Still, our theoretical view of the priming effect seems to hold: reflection on anticipated bishop reaction to their professional performance leads priests receiving the Institutional Prime to self-report higher levels of political participation

versus the control.

Recall, of course, that the Institutional Prime also contains items regarding priest concern about parishioner reaction to political statements made. While priests demonstrated less interest in parishioners vs. bishops as preferred cue givers in our multinomial logit model, does the threat of parishioner sanction end up cutting against supposed-bishop influence in taking a political stand? Arguably the best indicator of such an effect would be if priests receiving the Institutional Prime were statistically indistinguishable from the control group in response to the “taking a stand on a political issue during Mass” item, as Mass is the time when the largest number of local parishioners are likely to encounter their priest. What we find, however, is that the mean for treated priests on the 1–4 scale is 2.71 vs. 2.30 for the control group (p < 0.01). For reference, the mean on this question for priests treated with the Interpersonal Prime was 2.33. Therefore, even as the taking a political stand during Mass question had the lowest mean of the five Political Behavior Index items, it was not the Institutional Prime priests who contributed to the lower score. Instead, these primed priests were the most likely to indicate taking a political stand during Mass, which recommends the conclusion that priests considering their reference groups’ expectations are more concerned with their bishops than parishioners.

Of our two research questions, we are confident that the findings thus far confirm that priest reliance on bishops for professional cues is based in cognitive reflection about one’s professional identity as seen through the web of reference group expectations. Yet rather than a balance between parishioner and bishop concerns, priests in our Institutional Prime appear most interested in their institutional superiors. Though there is some evidence that this bishop and reference group-centered thinking increases negative views of religious institutions (contrary to our expectations), this reaction is somewhat tangential to the core issue of bishop influence. Indeed, priests may develop a negative perception of religious institution as a result of following their superiors’ wishes, but they follow nonetheless.

Where our analysis remains unfinished, is on the extent to which the bishops factor into priest responses on these outcome measures, particularly that of political behavior (the second of our research questions). Building on our finding of priest preference for bishop cues (most notably among those receiving the Institutional Prime), our next round of statistical analysis incorporates this bishop cue outcome used in the multinomial logit model from

Table 3. Using a generalized structural equation framework, we can isolate the effect of priest reliance on bishop cues as separate and direct effects on the outcome indices, while maintaining measurement of the priming treatment influences on those indices [

48]. Finding that bishop cues have direct effects on the outcome indices would constitute strong support for the notion that priests not only look to their institutional superiors for professional guidance, but that this guidance significantly affects priest behavior.

6. A Bishop Path to Influence?

Our proposed causal path suggests that priests, when considering institutional reference group expectations as spurred through the Institutional Prime, will indicate a reliance on bishop cues in discharging their professional responsibilities. These cues are posited to have a direct effect on the outcome variables (i.e., the Institutional Perception and Political Behavior Indices), and they may also represent an indirect effect from one or both of the assigned primes. Owing to the robust nature of the Institutional Prime’s effect in our analysis to this point, we also expect that the cognitive considerations raised by the treatment will have a direct impact on the outcome indices independent of any bishop cue effects. And, though it has not shown a statistical impact to this point, we extend the same expectation of a direct effect on the outcome measures to the Interpersonal Prime given that our research design is based on a direct comparison of the two treatments. In order to preserve leverage in determining direct causal effects from our randomly assigned primes, priest reliance on bishop cues must be considered endogenous to the primes. In other words, the assigned primes spur priest reflection, which then leads to an indicated preference for cues from their bishop.

As useful and frequently employed structural equation models are [

49], however, the finding of a mediated or indirect effect should be handled with caution no matter how statistically robust it is. Despite the use of random assignment for the question primes, priests’ self-reported reliance on bishop cues is not, itself, a randomly assigned condition. This means that unobserved confounding explanations cannot be ruled out in determining the cue-based portion of any effects reported in the structural equation models [

50]. Unfortunately, it is virtually impossible to satisfy a determined critic where indirect effects are involved, even with a second round of randomization present. The advice Bullock, Green, and Ha [

51] provide on this matter is to build a literature around the study of a specific indirect effect and assess the consistency of its impact across research designs. To our knowledge, we are the first to examine bishop cue use among priests stemming from a randomized treatment. Though this means we are unburdened by reconciling our findings with past results, it also underscores that the findings to follow should be recognized as the first word, not the last, on this question.

Though the success of our random assignment allowed us to avoid use of controls in direct tests of prime effects in the multinomial logit and mean differences assessments, ruling out confounding explanations for an indirect effect without randomization necessitates inclusion of at least the most commonly used control variables from the literature. Based on the broader clergy politics literature, we include controls for a priest Republican party identification (1 = GOP), Democratic Party identification (1 = Democrat), priest age, the reported number of household’s in a priest’s parish, the type of area in which a parish is located (1 = rural), self-reported priest political ideology (0–10 scale, with higher values indicating increased conservatism) and priest perception of their parishioners’ and bishop’s political ideology (measured on the same 0–10 scale). In addition to these base variables, we include the squared differences in perceived ideological difference between (1) the clergy subject and denominational superiors, and (2) subjects and parish congregants to create separate measures of perceived ideological difference among priest reference groups [

52]. Owing to the non-parametric nature of priest subject pool, we report bootstrap standard errors using 100,000 replications with replacement.

Given the results of the multinomial logit model, it is unsurprising that the Institutional Prime is again found to significantly increase priests’ self-reported reliance on bishop cues in the first portion of the model in

Table 5, which focuses on the Institutional Perception Index first discussed as part of the

Table 4 results. The more intriguing finding comes in the model’s second portion, which assesses the role of bishop cues and the assigned treatments on the perception index scores. Though the Institutional Prime significantly and directly increases priest index scores by 2.34 on the 0–10 index, bishop cue reliance also significantly increases negative institutional perceptions, albeit by a much lower magnitude of 0.495. Meanwhile, the indirect effect of the Institutional Prime as it passes through priest reliance on the bishop cue is of an even smaller magnitude: 0.186. Still all three coefficients are significant at

p < 0.01, and, taken together, suggest that priest reliance on bishop cues, which are spurred by the Institutional Prime, increases priests’ negative perceptions of religious institutions. This finding returns attention to the idea that priests may choose to rely on bishop cues, but they do not necessarily like all that this reliance requires.

The more important of the two indices, of course, pertains to priest self-reported political behavior. The structural equation model for this outcome is in

Table 6. Here, we again find that the Institutional Prime animates clergy self-reports. In this case, the prime increased self-reported clergy political behavior index scores by 0.382 (

p < 0.01) on the 1–4 index. However, and unlike in the Institutional Perception model in

Table 5, priest reliance on bishop cues does not increase the behavior index score, nor does the Institutional Prime have a statistically significant indirect effect when passing through the bishop cue variable. We consider implications of this finding in our conclusion.