Two instances of Buddhist practice provide examples of the way in which a syntactic analysis can be conducted. The first is insight meditation practice, and the second is tantric fire ritual (homa). As insight meditation practice is not tantric in character, it provides a useful contrast to the homa, which is considered tantric.

4.1. Insight Meditation Practice Session

Insight is a form of Buddhist meditation that has spread from its origins in Burma to the United States, Europe and elsewhere globally over the last several decades [

37,

38]. It is similar to the perhaps more widely known mindfulness meditation, insight having been one of the main sources for the development of mindfulness [

39]. Commonly, insight meditation is practiced in groups on a regular weekly basis. This practice is complemented by individual practice at home, and practitioners may also participate in daylong sessions, or retreat programs of intensive meditation for periods of a few days, to weeks and in some cases months. Most insight groups self-identify as Buddhist, while mindfulness groups tend to eschew any religious identity, claiming instead to be secular. These are not, however, strict segregating markers as the boundaries between the two are very permeable. For example, some of the largest and best-known mindfulness teacher training programs require students to attend Buddhist retreats as part of their training. Also, these institutions continue to undergo rapid change, and characterizations such as “Buddhist,” “secular,” “self-improvement,” “therapeutic,” and so on are presently in flux. The following description is a generalized one largely based on my own experience with such groups, specifically in the San Francisco Bay Area, over several decades of personal involvement with Buddhism.

In present–day insight meditation sessions, most participants—including teachers—are casually dressed in ordinary street clothes. This contrasts with some Buddhist meditation groups whose teachers and in some cases participants adopt special clothing such as traditional robes. Similarly “Westernized” is the accepted use of chairs for sitting during the meditation session per se, and during any attendant instruction (often referred to as a “dharma talk”). Noting that there are variations from teacher to teacher and from group to group, procedurally one could expect the following—

participants enter the hall, sitting quietly, some on chairs, some on cushions on the floor,

at the start of the session, the teacher rings a bell or gives some other conventional signal that the meditation part of the session has started,

participants sit comfortably upright, some with eyes lowered, others with eyes closed, some with their hands folded on their laps, others with their hands on their legs; such variations seem to be quite accepted and it is my understanding that they result from different background experiences participants may have had with yoga, Zen, and so on,

after a few minutes the teacher may speak quietly, reminding the participants to hold their attention on the breath, which is the most common object of meditation for insight meditation sessions; these instructions are usually brief, unless the session is specifically for beginning participants who may need more frequent or more detailed instruction,

the balance of the meditation period, whether twenty, thirty or forty minutes, passes in silence, and at the end the teacher again gives a signal such as ringing a bell,

this is followed by a short period for standing and stretching, after which participants again take their seats,

there may then be announcements of various kinds—of visiting teachers, other meditation trainings, workshops, and social events,

the instruction period, twenty minutes to an hour, then follows; different teachers have widely varying styles—some are quite anecdotal, some draw on a wide range of religious traditions for stories and allegories, some are focused on specific sequences of instruction based on scriptural sources (most commonly from the Pāli canonic and extracanonic materials), and some will mix elements from all three styles,

at the end there may be a period for questions and answers, followed by closing, and then sometimes an opportunity for socializing, including in some cases a shared meal or other refreshments.

This is a very generic description, an outline which both orients those unfamiliar with such meditation sessions, and provides the basis of the syntactic analysis below. In considering this from the perspective of a cognitive study of ritual, there are four important dimensions of insight meditation practice—the absence of any specific content, the problematic character of any role for a “culturally posited supernatural agent” (see below), such sessions as ritualized activities, and the organization of the session.

The meditation itself is not “about” anything, that is, there is no specific referential meaning that is the focus of insight meditation. It is something that one does, an embodied activity. One is to keep one’s attention in the present by focusing on the experience of breathing. There is no specific symbolic reference involved. The instruction will often provide guidance toward better meditation practice, such as by discussing difficulties that one may encounter during practice, and such guidance may draw on canonic or paracanonic texts. In some instances teachers will give specific forms of practice, such as “loving-kindness,” that may be practiced in order to develop certain qualities within oneself. While in a general way such guidance contributes to the development of a particular worldview, these teachings are generally not specifically doctrinal in character. Based on my experience, for example, it would be very unusual to encounter assertions as to the actuality of karma and rebirth as central to the instruction provided, which tends to either focus on meditative practice or more general spiritual topics. Some participants may ask about these kinds of topics during the question and answer period, however usually in response to something they have heard or read outside the context of insight meditation sessions per se.

There are, of course, founding myths, both about the meditation of Śākyamuni Buddha, and about the teacher’s experiences—myths that serve to legitimize the practice and the teacher. And some theorists might attempt to argue that these provide the meditation with meaning. Such meaning is not, however, referential in the way usually meant when scholars assert that ritual has meaning or is meaningful (for clarity we note that “meaningful” is not used to indicate “personally significant” or “emotionally evocative,” but rather to indicate that either the ritual as a whole or elements of it have meanings ascribed to them).

E. Thomas Lawson and Robert N. McCauley [

40], Ilkka Pyysiäinen [

41], and others have promoted the idea that what marks religion is belief in “culturally posited supernatural agents” (CPS-agents; more recently “agents possessing counter-intuitive properties,” or CI-agents (see [

8], p. 89, n. 24). This idea has been extended to the claim that such agents play a founding role in religious ritual. A religious ritual in Lawson and McCauley’s view has a three-part structure: agent, action, object ([

41], p. 14)—basically the structure of an English language sentence with a transitive verb, which they interpret as the cognitive meaning structure describing ritual action. On their view what distinguishes religious ritual from other actions that can be described in terms of the same three part structure is the role of a CPS-agent in establishing or founding the ritual. For example, the CPS-agent may be thought to have provided the first initiation, and the current priesthood derives its authority from that event. If we presume CPS-agent theory a priori and attempt to apply it to insight meditation practice, it may be tempting to interpret the position of the teacher as authorized through an initiatory sequence leading back to the actions of the founder, Śākyamuni.

In my experience, however, most insight meditation practitioners follow some version of the Buddhist modernist belief system, which emphasizes the merely human status of Śākyamuni. It is not uncommon to find teachers of insight meditation who, despite perhaps having spent time in monasteries in South East Asia as either lay practitioners or as monastics, will pointedly say that Śākyamuni is not a god. They will emphasize that he is not an object of worship nor is he prayed to, but that he is honored for having become awakened. Awakening is presented as an accomplishment that is both a model of our own potential and an assurance that it is something that can be achieved by ordinary human beings such as ourselves. Consequently, were we to apply the criteria for “religion” propounded by CPS-agent theorists, insight meditation practice would not be religious. To clarify, the issue is not a contrary claim on my part that insight meditation “really is religious.” Instead, the point is that while the concept of a CPS-agent may be descriptively valuable for some rituals, to employ that concept as a criterion for what is and what is not religious is an arbitrary and a priori use.

Similarly, Lawson and McCauley claim that one criteria for “religious ritual” is that “invariably, religious rituals, unlike mere religious acts, bring about changes in the religious world (temporary in some cases, permanent in others) by virtue of the fact that they involve

transactions with CPS-agents.” ([

42], p. 159). According to this criteria, insight meditation practice is not a religious ritual, and may not even be a “religious act.” While there are ideologues on both sides of the question of secular and religious Buddhisms, my point here is not to fuel those debates, but rather to point to the limitations imposed by an artificial, a priori definitional clarity that covertly introduces theological preconceptions.

If we consider the practice of insight meditation as described above from the perspective of Bell’s approach of ritualization, it is moderately ritualized. Bell says that “formality appears to be, at least in part, the use of a more limited and rigidly organized set of expressions and gestures, a ‘restricted code’ of communication or behavior in contrast to a more open or ‘elaborated code.’” ([

36], p. 139). By this characterization an insight meditation session is moderately formal—it is distinct from other, more clearly social events by having regular times and places, and by having more constrained behavior and speech. Although the kind of meditation is a modern development [

43], it is generally presented as having its origins in the teachings of Śākyamuni. In this representation insight meditation is given the aura of tradition. Bell identifies this as traditionalization, defining this concept by saying that “The attempt to make a set of activities appear to be identical to or thoroughly consistent with older cultural precedents can be called ‘traditionalization.’” ([

36], p. 145).

Bell explains the next characteristic, invariance, stating that “One of the most common characteristics of ritual-like behavior is the quality of invariance, usually seen in a disciplined set of actions marked by precise repetition and physical control” ([

36], p. 150). There is very little variance in the sequence of events from one week to the next in insight meditation sessions, though this invariance is not itself held to be essential to the efficacy of the meditation practice. Bell explores the invariance of meditation practice in relation to the goals of personal transformation, which are central to insight meditation, and also calls attention to the rejection of the label “ritual” by Buddhist modernists who are under the influence of a highly rationalized representation of Buddhism promoted by apologists in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. She says that meditation is an “example of the way in which invariant practice is meant to evoke disciplined control for the purposes of self-cultivation, although some spokespersons for various traditions of meditation have attempted to distinguish meditation from ritual” ([

36], pp. 151–52).

As defined by Bell, rule-governance can be deployed for any number of different ends. “Rule-governance, as either a feature of many diverse activities or a strategy of ritualization itself, also suggests that we tend to think of ritual in terms of formulated norms imposed on the chaos of human action and interaction. These normative rules may define the outer limits of what is acceptable, or they may orchestrate every step” ([

36], p. 155). In addition to the orderliness imposed by the semi-formal nature of an insight meditation session, the practice of insight meditation per se is governed by a set of rules reflecting the ideas regarding proper meditation—though in this case “proper” meditation is itself conceived in terms of “effective” meditation. There may be some sacral symbolism employed in an insight meditation session, perhaps a small statue of Śākyamuni, with flowers and a candle, though these latter are not treated as formal offerings as they might be in a temple setting. Bell notes, however, that there is a fundamental circularity between sacral symbols and ritual activity. “While ritual-like action is thought to be that type of action that best responds to the sacred nature of things, in actuality, ritual-like action effectively creates the sacred by explicitly differentiating such a realm from a profane one” ([

36], pp. 156–57). Thus there is a dialectic between the sacral symbols creating an environment for ritual-like behavior and that ritual-like behavior serving to identify the symbols as sacral. Performance is itself a complex, multifaceted characteristic in Bell’s understanding. One of the facets that is particularly relevant to insight meditation is that “the power of performance lies in great part in the effect of the heightened multisensory experience it affords: one is not being told or shown something so much as one is led to experience something” ([

36], p. 160). The “heightened multisensory experience” afforded by an insight meditation session is created not by increasing stimulation above the norm, but rather by reducing stimuli so that attention can be focused with greater intensity. Thus, in this sense there is the same effect reached by an approach opposite to what her description might lead one to expect. Considered along these axes, we can see that insight meditation sessions score in what might be designated the “upper middle range” of ritualization.

Figure 3 shows the basic structure of an insight meditation session as outlined above. Regarding Bell’s criterion of invariance, we can note that there is no inherent reason that the order of meditation period and instruction could not be reversed. It would give a different experiential tone, and teachers may prefer the tone this structure gives, or it may simply be traditional in the sense that this is the way they learned and prefer to not change it. Syntactically, what is important to notice is the groupings of actions. These will be discussed below in considering the nature of syntax as such, and the importance of hierarchical groups of actions in ritual performances.

When considering ritual, CPS-agent theorists (such as Lawson and McCauley) and others who dichotomize ritual from other actions choose to focus almost exclusively on “religious ritual” (in some instances they write as if they consider “ritual” and “religious ritual” to be coterminous). The instance of insight meditation practice suggests that the scope of their approach could benefit by understanding ritual as a range along Bell’s several categories, and taking into consideration “secular ritual.” An instance of secular ritual relevant here is the sequence of training and testing involved in gaining a driver’s license. It is a highly ritualized sequence requiring the services of specialists who conduct the testing and provide the certification, and has as its grounding the agentive authority of the state. While the “state” is a culturally posited agency, it is not supernatural (nor counter-intuitive)—but does serve the same function of grounding the ritual system. A cognitive study of ritual should, therefore, dispense with the theologically loaded requirement of a supernatural agent, and consider a broader range of ritualized practices than allowed for by Lawson and McCauley, other CPS-agent theorists, as well as all theories based on dichotomizing ritual into a special category separate from other activities.

4.2. Homa—Tantric Fire Offering in the Shingon Tradition

The homa is a very dramatic ritual performance, one involving the construction of a fire on an altar and the making of offerings into that fire. With its roots in the Vedic tradition, Buddhist tantra incorporates the figure of Agni, the Vedic fire god who receives and purifies offerings, and who then transmits them to the gods. The homa is found not only in Buddhist tantric traditions, but throughout the tantric world [

44].

The first homa that I observed was held early on New Year’s morning, beginning about 5 a.m., in the Sacramento Shingon temple. Dark inside the temple, the priest began the ritual, and while he was lighting the fire, a taiko drum began sounding loudly from alongside the altar. The congregation (saṃgha) of about 150 people began chanting the Heart Sutra in unison, while flames on the altar alternately flared up and then died down, and repeated the cycle. It was only later that I understood that there were five subrituals, all basically the same, and that in each subritual additional kindling was first added to the fire, oil was then poured into it causing the flames to light up the dark room, and other offerings made into the fire. After about 45 minutes the ritual was finished. The priest rose from his place in front of the fire, and left the altar (naijin, 内陣). By this time the sun had come up, and the temple was opened to allow the smoke to clear. The priest returned, having changed out of the formal robes of the ritual performance, and gave a short greeting. We were all given a handful of dry soy beans and three times on the count of three threw the beans and shouted “Oni wa soto, fuku wa uchi” (demons out, good luck in), a traditional Japanese way to greet the new year.

The five subrituals were to five different deities or sets of deities. The first is Agni (Katen, 火天), while the second is referred to as the “Lord of the Assembly.” Who this is varies depending on who the Chief Deity of the ritual performance is. The Chief Deity is the main figure of the ritual, and in the case of the New Year’s ceremony at Sacramento, the homa was a protective one and the Chief Deity was Acalanātha Vidyārāja (Fudō Myōō, 不動明王). Protective homas are probably the most commonly performed kind in present day Shingon, and Fudō one of the most popular Chief Deities. The fourth subritual is for the Celestial Deities, that is, asterisms, houses of the moon, and so on, while the fifth is for the Worldly Deities, a group that includes a number of Vedic gods.

While the Sacramento new year’s ritual was a protective one, in contemporary Shingon tradition there are four other functions—prosperity, subduing adversaries, emotional affinity, and summoning—for which the homa may be performed [

45]. Different functions require hearths of different shapes, robes of different colors, different times of performance, different endings to the mantras, and so on.

Homa performances are more highly ritualized than the insight meditation session described above. They are more formal, for example requiring special dress and formal behavior for the officiant, and though members of the

saṃgha are dressed in street clothes, their behavior and speech are also constrained. Like insight meditation, the homa is also represented as traditional—the performance of the ritual in its present form can be traced back several centuries, and is notably similar to performances in cognate tantric traditions as well. The performance tends to be highly invariant, with practitioners following the instructions of a ritual manual (cf. [

8], pp. 112–17). Although individual lineages have their own manuals, such manuals are generally very similar to one another in terms of the ritual actions specified and the order of their performance. There is a clear setting of sacral symbolism, as the ritual is performed on a special altar, which like other Shingon altars is homologized with both a maṇḍala and a stupa, before a statue, scroll, or other representation of the deities, and inside of a Buddhist temple. The flames leaping up in a darkened temple, together with the sonic driving of

taiko drum and group chanting afford the kind of “heightened multisensory experience” that Bell identifies with the performance dimension of ritualization.

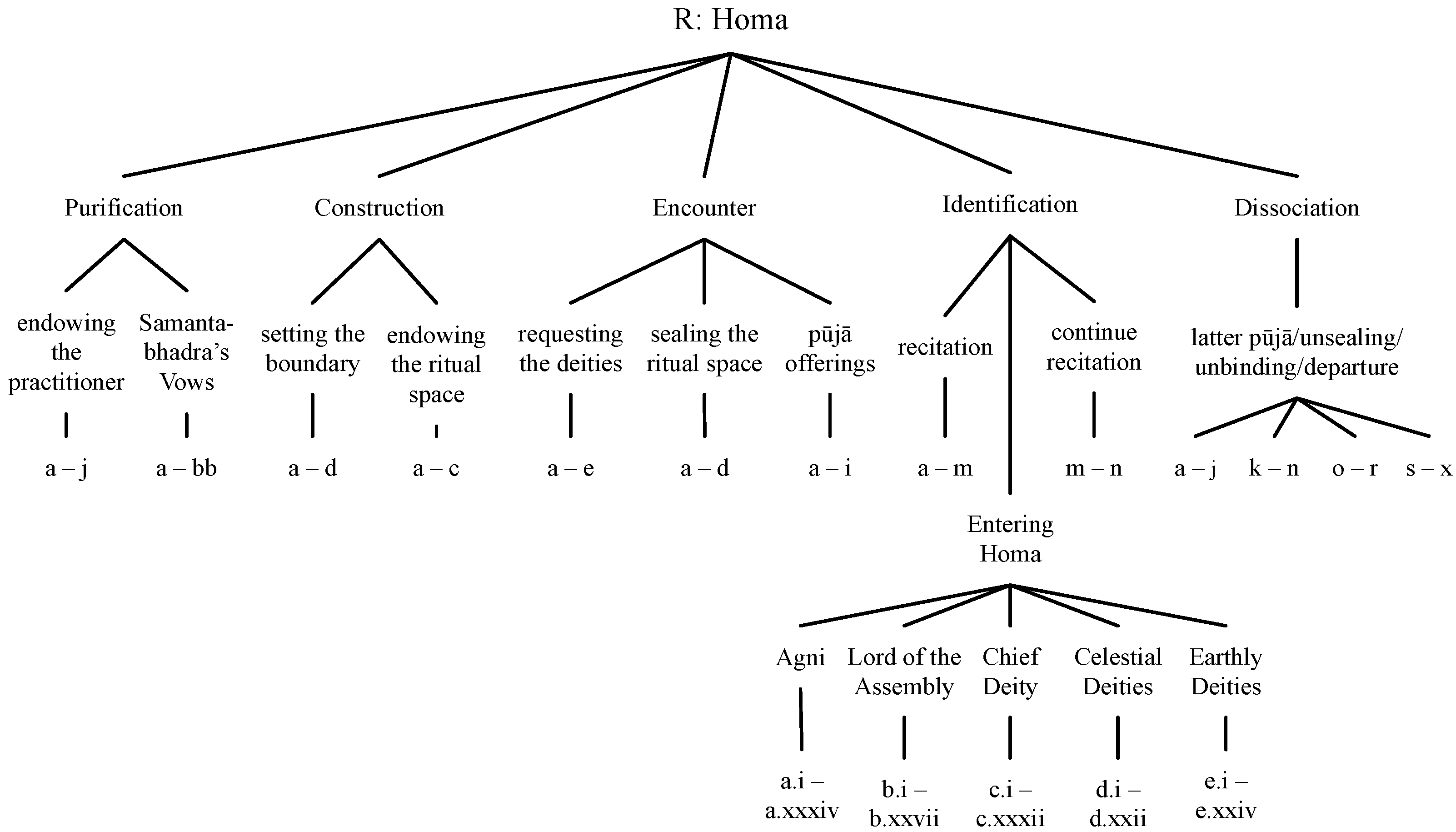

In

Figure 4 the greater complexity of the homa compared to an insight meditation session is evident. In this case the invariance is much greater, and the hierarchical groups of actions more greatly stratified. (The instance represented here is an Acalanātha śāntika homa from the Shingon tradition. For a full analysis, see [

46], pp. 285–321.) The diagram has been abbreviated in order to simplify the basic structure. The ritual has five major sections: Purification of the practitioner, Construction of the ritual site, Encounter with the deities, Identification with the deities, and Dissociation from the deities and ritual. Each of these five constitute a hierarchical group of ritual actions—the significance of such hierarchical groups is discussed below. And the next level of detail indicates that each of these five have groups of actions, and each of those in turn comprise groups of actions—indicated by lower case letters. Some of the actions indicated by lower case letters are single actions, while others are themselves groups of actions, a level of detail not indicated in this diagram.

The group identified as “Entering Homa” is the group of five subrituals described above, one set of offerings for each of the five deities or groups of deities evoked in the ritual. This is an instance of what Staal called embedding, the group of five subrituals having been added to a ritual structure found in other Shingon rituals. In this case each of the five are effectively complete rituals of offering themselves with preparations, invitation, offerings, and dissociation.

In addition to embedding, the homa displays two other rules of ritual syntax, also found in many other rituals of the Shingon corpus (cf. [

8], pp. 89–90). These are symmetry and terminal abbreviation. These are comparable to phrase structure rules, that is, ways in which the elements of rituals may themselves be organized. As in linguistics, a phrase structure rule for ritual does not mean that it is found in every instance of ritual. This kind of phrase structure rule, however, applies to two instances of the “same” phrase within a single ritual, a situation not usual in language, though not impossible. (For example, “The skillful plumber was met by John, who was happy to know someone skilled at plumbing.”)

Symmetrical organization refers to the groups of actions performed at the beginning of the ritual being repeated at the end. While all of the homas in the Shingon corpus examined to date evidence symmetry, this is not “

the key ritual structure” ([

2], p. 156, emphasis in original). Rather, symmetry is a descriptive generalization of a particular set of rituals, not a pattern of “ritual” universally. Though the level of detail given in the diagram here does not reveal it, there are two kinds of symmetry, sequential and mirror-image. In sequential symmetry, the elements occur in the same order at both the beginning and end of a ritual, while in mirror-image symmetry, the order is reversed.

The homa and other rituals also demonstrate “terminal abbreviation.” In some cases the actions done at the end of the ritual are reduced in number of repetitions performed compared to when done at the beginning. Also, the set of actions within the hierarchically structured groups may be simplified. A hypothetical example would be that an act of purification at the beginning of the ritual might include three actions, the second of which is repeated five times. At the end of the ritual purification is to be performed by only three repetitions of the second action—that is, both the first and third actions are absent, and the second is repeated fewer times. This is why the last of the five major groupings shown in the diagram, Dissociation, has listed under it a single compound, “latter pūjā/unsealing/unbinding/departure.” This compound represents in reverse order (mirror-image symmetry) and abbreviated form all of the actions preceding Encounter.

Although more formal and more complex than an insight meditation session, the homa is also problematic for CPS-agent theorists. While like many tantric rituals it is thought to be made effective by the ritual identification of the practitioner with the chief deity, there is no mythology regarding the homa ritual being established by Śākyamuni. While having been introduced to Japan by Kūkai, neither his legendary status nor the character of the transmission of the ritual qualify as the actions of a CPS-agent as defined. Nor is it said to be some kind of primal act by Mahāvairocana, the central buddha for the Shingon tradition, nor by any other buddha. In one of the main scriptures for the Shingon tradition, the Vairocanābhisaṃbodhitantra there are, for example, chapters describing the homas of competing traditions, and of the homas of tantric Buddhist tradition, but nothing about any supernatural agent having first enacted or established the ritual—no mythology of founding in the sense indicated by CPS-agency theories.