Bad Religion as False Religion: An Empirical Study of UK Religious Education Teachers’ Essentialist Religious Discourse

Abstract

:1. Introduction

We teach general tolerance to all people, of all religions and that all religions teach peace, love and compassion, with the odd exception where there may be extremists who misinterpret their holy books, but that they exist within all religions and that they are not true followers.[English Secondary Academy/Free School Teacher]

Buddhist terrorist. Muslim terrorist. That wording is wrong. Any person who wants to indulge in violence is no longer a genuine Buddhist or genuine Muslim, because it is a Muslim teaching, you see, once you are involved in bloodshed actually you are no longer a genuine practitioner of Islam. All major world religious traditions carry the same message: the message of love, compassion, forgiveness, tolerance, contentment, self-discipline—all religious traditions.(Dalai Lama 2016 [Emphasis added])

It is not good enough to say simply that Islam is a religion of peace and then to deny any connection between the religion of Islam and the extremists. Why? Because these extremists are self-identifying as Muslims. From Tunisia to the streets of Paris, these murderers all spout the same twisted narrative that claims to be based on a particular faith. To deny that is to disempower the critical reforming voices that want to challenge the scriptural basis on which extremists claim to be acting—the voices that are crucial in providing an alternative worldview that could stop a teenager’s slide along the spectrum of extremism. We can’t stand neutral in this battle of ideas.(Cameron 2017a [Emphasis added])

2. What’s Wrong with Essentializing Religion?

[A]l-Qaeda is a distinctively Islamic group. Not only is its chosen constituency a confessional one, but al-Qaeda also uses—and when necessary adapts—well-known Islamic religious concepts to motivate its operatives, ranging from conceptions of duty to conceptions of ascetic devotion.

3. Religious Education in the United Kingdom (UK)

- Respect being given prominence over understanding;

- The essentialization of religious phenomena as a “cabinet of curiosities”;

- A failure to examine and consider the “rough edges” of religious phenomena;

- A lack of critical awareness of religious phenomena.

4. Presentation of Data

4.1. Question 23: “Religion Is Dangerous”

[Codes: Non-Essentialist; Dangerous People] I don’t think that religion is good or bad, safe or dangerous. I think that individual people are good or bad.[Secondary English State School Teacher]

[Codes: Non-Essentialist; Dangerous People] Lions are dangerous. So are people. Religion can’t be dangerous as it isn’t an actor. However, as with many ways of thinking, we have to acknowledge that religion can be a contributory factor in people becoming dangerous.[Secondary English State School Teacher]

[Codes: Essentialism; Extremism; Dangerous Interpretations] All religions are peaceful. It’s certain extremist people who misuse/misinterpret religion to create barriers and hate amongst people.[Primary/Junior English State School Teacher]

[Codes: Essentialism; Extremism; Dangerous Interpretations] We teach general tolerance to all people, of all religions and that all religions teach peace, love and compassion, with the odd exception where there may be extremists who misinterpret their holy books, but that they exist within all religions and that they are not true followers.[Secondary English Academy/Free School Teacher]

[Codes: Essentialism; Religion can be Dangerous] All religions want a loving a peaceful world where we all do what is right. It becomes dangerous only when religions start judging each other. We all worship God Almighty but religion allows people to do this in different ways.[Primary/Junior English State School Teacher]

[Codes: Dangerous People; Essentialism; Instrumentalism] I think that people choose to use religion in a dangerous way, to support their own beliefs, but that religion itself is not intrinsically dangerous. I cannot think of a religion that actively supports dangerous ideals.[Primary/Junior English State School Teacher]

[Codes: Essentialism; Dangerous Interpretations; Dangerous People] Religion is only dangerous if a “follower” makes it so. Religions are peaceful, interpretations of followers are dangerous.[Secondary Scottish State School Teacher]

[Codes: Dangerous People; Essentialism] It’s people who are dangerous when they change religious texts to fit in with their own ideology not religion itself.[Secondary Scottish State School Teacher]

[Dangerous People; Essentialism] People are dangerous, not religion.[Secondary English Academy/Free School Teacher]

[Codes: Dangerous People; Essentialism; Religion is not Dangerous] It is people that [Sic.] pervert religion that [Sic.] can be violent, not the religion.[Secondary English State School Teacher]

[Codes: Religion is not Dangerous; Essentialism; Instrumentalism; Dangerous People] Religion is not dangerous—it is merely a tool used by dangerous people in an attempt to justify their actions. If people were not using religion to incite violence, they would use something else. Religion is not dangerous—people are dangerous.[Secondary English Academy/Free School Teacher]

[Codes: Dangerous Interpretations; Essentialism; Instrumentalism] Wrong understanding, or wrong interpretation of religion is dangerous. No religion advocates violence per se, but all can be/have been used that way in human history.[Primary/Junior English State School Teacher]

[Codes: Essentialism; Lack of Education; Religion can be Dangerous] Lack of education about other religions leads to misunderstanding and intolerance, which is what makes religion dangerous; not religion itself.[Primary/Junior English Independent School Teacher]

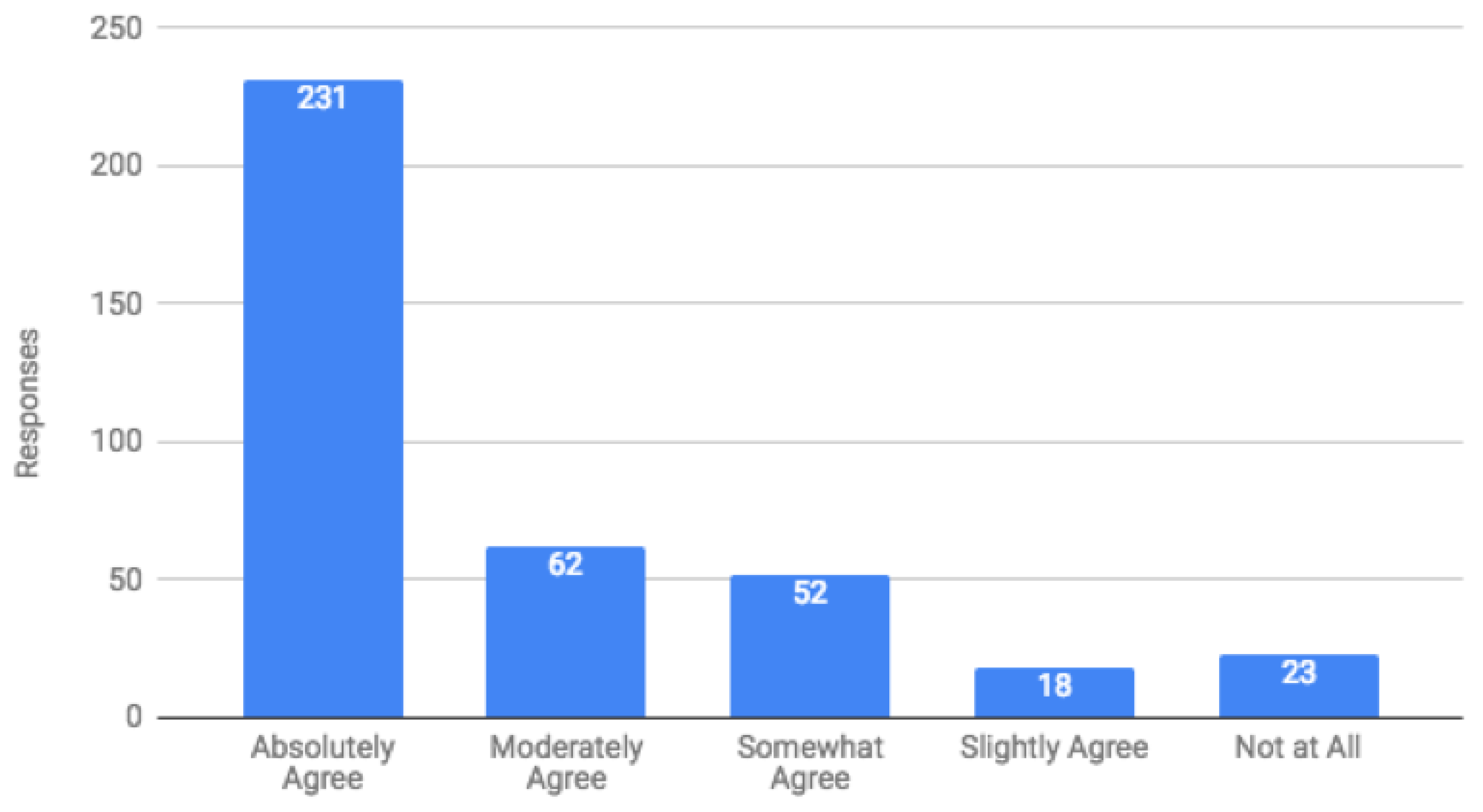

4.2. Question 24: “Religion Should Be Taught in A Positive Way in RE”

[Codes: Religion is Positive; Positive and Negative Presentations; Essentialism] Religion is a positive, loving entity and thus should be taught as such. This doesn’t mean negative elements should be left out, but the overarching feeling should be positivity.[Secondary English State School Teacher]

[Codes: Essentialism; Instrumentalism; Religion is Positive] We need to accept that some aspects of religion can be taken in a negative way and deal with these issues, however, it should always be underlined that these are tiny minority groups distorting religious doctrine.[Secondary English Academy/Free School Teacher]

[Codes: Essentialism; Instrumentalism] I would say that one needs to learn to see how religion is being used by those in authority to create discord in the world and within our communities. Children need to know about Religion and what it says and how it is being manifested in the world…school needs to do this, because I don’t think parents can do this.[Secondary Scottish State School Teacher]

[Codes: Positive and Negative Presentations; Essentialism] It’s a complex subject. Religion is a tool for life. Tools can be misused and so both the positives and negatives need to be explored to ensure proper use of the tool. This can be done in a positive way but the pitfall of dumbing down should be avoided.[Secondary English Academy/Free School Teacher]

[Codes: Bias; Essentialism; Media] Correct teaching of faiths would counteract prejudices and choices of discriminatory behavior among some of our society. A perception based on poor reporting, unsubstantiated media and preconceived ideas needs to be challenged with true, unbiased responsible teaching.[Secondary English State School Teacher]

[Codes: Criticality; Essentialism; Instrumentalism; Taught Positively] The positive impact on human lives should definitely be taught. However, so should the critical skills needed to discern when religion is being used to promote inhuman or immoral conduct or attitudes.[Secondary English Academy/Free School Teacher]

[Codes: Criticality] RE is about the critical study of religion.[Secondary Northern Irish State School Teacher]

[Codes: Choice; Criticality; Objectivity] Religion should be taught about factually, in an objective manner. Students should be encouraged to critically evaluate religious concepts and beliefs for themselves to determine whether a particular religion is “positive”.[Secondary English Independent School Teacher]

[Codes: Criticality] RE must include critical thinking and philosophy encouraging pupils to think independently i.e., atheist and agnostic views must be part of lessons.[Secondary English State School Teacher]

[Codes: Criticality; Dangerous Interpretations] Religious studies must encourage students to be critical. There are issues which cannot be ignored that stem from interpretations etc. of religious teachings. We do not have to respect all beliefs, we should engage critically and encourage our students to do the same, drawing conclusions and views on teaching and practices that are reasoned and justified. I would not teach children to “respect” or view positively the issue of child marriage or FGM as it is a practice tied to religion or culture. I would present them with the information and let them decide if it is a belief to be challenged or respected.[Secondary Scottish State School Teacher]

[Codes: Bias, Neutrality] It should be taught in a neutral way but it’s usually taught as positive. I teach it as a phenomenon, not a guide. It seems that most RE teachers and resources tend to pick the nice bits and shy away from some controversies, especially in primary schools and faith schools. Children are guided towards a biased understanding of religion.(Primary/Junior English State School Teacher)

5. Discussion

It is indisputable that the suicide-bombers derive inspiration and comfort from their reading of the Qur’an. It is therefore peculiarly important that a true and fair reading is taught. For the problem in a nutshell is this: that there are verses in the Qur’an—as there are in the Bible—which, taken out of context and without regard for the import of the Qur’an as a whole, do justify hatred and violence…The overwhelming import of both Bible and Qur’an is pro-love and anti-violence.(Watson and Thompson 2006, p. 149 [Emphasis added])

This potential will only be realized…when educators fully acknowledge the “intractable” nature of religious difference and implement strategies and policies that predicate respect for others on personhood rather than on theological assumptions about the essential agreement between religions and between religious adherents.

6. Religious Literacy?

7. Recommendations

- Educate teachers and learners, and encourage them, to recognize and critique essentialist representations of religion;

- Avoid using essentialist expressions, such as “Hindus believe…” in favor of “while some Hindus believe, others…” or “the majority of Hindus believe…while a minority believe…”;

- Embed the concept of religious plurality through the use of terms, such as “Christianities”, “Islams”, etc.;

- Emphasize diverse religious expressions: beliefs, practices, and attitudes, within and across religious traditions and communities;

- Use a range of images in lesson resources and classroom displays which reflect religious diversity;

- Create a dialogic space, being prepared to “pause” the lesson to discuss issues, examples, and experiences of religious diversity;

- Arrange encounters with diverse representations through visitors, visits, and video clips; for example, invite three Buddhists rather than one to talk about what the concept of rebirth means to them;

- Avoid using stereotypical images of religious people—for example, only showing Muslim women wearing headscarves;

- Explicitly consider religious diversity, and where relevant where these intersect with other forms of diversity, when devising learning aims and intended learning outcomes;

- Avoid crude equivalences between religions, for example, the Qur’an is the Muslim Bible;

- Avoid giving narrative privilege to any particular denominations/sect/spokesperson, for example, presenting the Dalai Lama as the leader of Buddhism globally;

- Ensure clear distinctions between the purpose(s) of RE and any religious activity in schools (in particular religious observance/worship) as there is evidence of an ongoing conflation of the two (Nixon 2018) which perpetuates essentialism.

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adib-Moghaddam, A. 2009. A Metahistory of the Clash of Civilisations: Us and Them beyond Orientalism. London: Hurst. [Google Scholar]

- Baldick, C. 2008. The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms, 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, R. 1974. Matthew’s Understanding of the Law: Authenticity and Interpretation in Matthew 5:17–20. Journal of Biblical Literature 93: 226–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, P. L. 2009. Religious Education: Taking Religious Difference Seriously. Impact Special Issue 17: 9–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, D. 2017a. Extremism Speech. The Independent Newspaper. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/david-cameron-extremism-speech-read-the-transcript-in-full-10401948.html (accessed on 23 September 2018).

- Cameron, D. 2017b. Lord Mayor’s Speech. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/lord-mayors-banquet-2015-prime-ministers-speech (accessed on 12 September 2018).

- Cavenaugh, W. 2004a. Terrorist Enemies and Just War. Christian Reflection 12: 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cavenaugh, W. 2004b. The Violence of ‘Religion’: Examining a Prevailing Myth. Working Paper No. 310. Available online: http://www.nd.edu/~kellogg/publications/workingpapers/WPS/310.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2018).

- Conroy, J. C., D. Lundie, R. A. Davis, V. M. Baumfield, L. P. Barnes, T. Gallagher, K. Lowden, N. Bourque, and K. Wenell. 2013. Does RE Work? A Mutli-Dimensional Investigation. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Conroy, J. C. 2016. Religious Education and Religious Literacy—A Professional Aspiration? British Journal of Religious Education 38: 163–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment. 2015. Religious Education. Available online: http://ccea.org.uk/curriculum/key_stage_1_2/areas_learning/religious_education (accessed on 13 May 2018).

- Schools Council. 1971. Working Paper 36: Religious Education in Secondary Schools. London: Evan/Methuen. [Google Scholar]

- Dalai Lama. 2016. Speaking at the European Parliament in Strasbourg in France. The Independent Newspaper. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/dalai-lama-muslim-terrorism-islam-no-such-thing-as-video-watch-speech-a7317001.html (accessed on 21 August 2018).

- Department for Education. 2017. School Workforce in England. Available online: https://www.ethnicity-facts figures.service.gov.uk/workforce-and-business/workforce-diversity/school-teacher-workforce/latest (accessed on 7 November 2018).

- Scottish Education Department. 1972. Moral and Religious Education in Scottish Schools; Edinburgh: Scottish Education Department.

- Department for Children, Schools and Families. 2010. Religious Education in English Schools: Non Statutory Guidance. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/190260/DCSF-00114-2010.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2018).

- Dunn, J. D. G. 2015. Neither Jew nor Greek: Christianity in the Making, Volume 3. Grand Rapids: Wm B. Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education. 2015. The Prevent Duty Departmental Advice for Schools and Childcare Providers. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/439598/prevent-duty-departmental-advice-v6.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2018).

- Eickelman, D., and J. Piscatori. 1996. Muslim Politics. Princeton: Princetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- The Office for Security and Co-Operation in Europe. 2007. Toledo Guiding Principles on Teaching about Religon and Belief in Public Schools; Warsaw: Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights.

- Evangelical Alliance Commission on Unity and Truth among Evangelicals. 2000. The Nature of Hell. London: Acute/Paternoster. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, T. 1997. A Critique of the Concept of Religion. Method and Theory in the Study of Religion 9: 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, M., and A. Dinham. 2016. Religious Literacies: The Future. In Religious Literacy in Policy and Practice. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garland, D. E. 2003. 1 Corinthians. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Government. 2008. Curriculum for Excellence, Religious and Moral Education Principles and Practice Paper. Available online: https://education.gov.scot/Documents/rme-pp.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2018).

- Welsh Assembly Government. 2017. National Exemplar Framework for Religious Education for 3 to 19—Year Olds in Wales. Available online: http://learning.gov.wales/docs/learningwales/publications/130426-re-national-exemplar-framework-en.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2018).

- Gunning, J. 2007. A Case for Critical Terrorism Studies? Government and Oppositions 42: 363–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunning, Jeroen, and Richard Jackson. 2011. What’s so ‘religious’ about ‘Religious Terrorism’? Critical Studies on Terrorism 4: 369–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasenclever, A., and V. Rittberger. 2000. Does Religion Make a Difference? Theoretical Approaches to the Impact of Faith on Political Conflict. Millemium 29: 641–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, Ahmed S. 2014. The Islamic State: From Al-Qaeda Affiliate to Caliphate. Middle East Policy 21: 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitchens, C. 2008. God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything. London: Atlantic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, B. 2006. Inside Terrorism. Columbia: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, P. 2011. Historical Literacy and Transformative History. In The Future of the Past: Why History Education Matters. Edited by L. Perikleous and D. Shelmit. Nicosia: Kailas. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D. C. 1993. The New Moses—A Matthean Typology. Edinburgh: T & T Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D. C. 2013. The End of the Ages Has Come: An Early Interpretation of the Passion and Resurrection of Jesus. Eugene: Wipf and Stock. [Google Scholar]

- Masters, D. 2008. The Origin of Terrorist Threats: Religious Seperatist, or Something Else? Terrorism and Political Violence 20: 396–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D. 2007. Overcoming Religious Illiteracy: A Cultural Studies Approach to the Study of Religion in Secondary Education. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, D. 2016. Diminishing Religious Literacy: Methodological Assumptions and Analytical Frameworks for Promoting the Public Understanding of Religion. In Religious Literacy in Policy and Practice. Edited by A. Dinham and M. Francis. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, G. 2013. Religious Education on the Darkling Plain: The Emergene of Philosophy within Scottish Religious Education. Saarbrucken: Lambert Academic Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, G. 2018. Conscientious Withdrawal from Religious Education in Scotland: Anachronism or Necessary Right? British Journal of Religious Education 40: 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obama, B. 2016. Why I Won’t Say Islamic Terrorism. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2016/09/28/politics/obama-radical-islamic-terrorism-cnn-town-hall/index.html (accessed on 23 September 2017).

- Panjwani, F., and L. Revell. 2018. Religious Education and Hermeneutics: The Case of Teaching about Islam. British Journal of Religious Education 40: 268–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pape, R. A. 2005. Dying to Win: The Strategic Logic of Suicide Terrorism. London: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, P. J., II. 1994. Catechism of the Catholic Church. London: Geoffrey Chapman. [Google Scholar]

- Prothero, S. 2008. Religious Literacy, What Every American Needs to Know. New York: Harper Col. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, David C. 1983. Fear and Trembling: Terrorism in Three Religious Traditions. American Political Science Review 78: 658–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revell, L. 2012. Islam and Education: The Manipulation and Misrepresentation of a Religion. London: Institute of Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, N. 2008. Faith Schooling: Implications for Teacher Educators. A Perspective from Northern Ireland. Journal of Beliefs and Values 29: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, N. 2017. Religious Literacy, Moral Recognition, and Strong Relationality. Journal of Moral Education 46: 363–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riches, J. 1996. Matthew. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, G. 1997. Building a Palestinian State: The Incomplete Revolution. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sageman, M. 2011. Understanding Terror Networks. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin, A. 2017. Religious Literacy, Interfaith Learning and Civic Education in Pluralistic Societies. In Interfaith Education for All. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, pp. 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Sayyid, S. 2003. A Fundamental Fear: Eurocentrism and the Emergence of Islamism. London: Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Schaffalitzky de Muckadell, C. 2014. On Essentialism and Real Definitions of Religion. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 8: 495–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission on Religious Education in Schools. 1970. The Fourth R: The Report of the Commission on Religious Education in Schools. London: Commission on Religious Education in Schools. [Google Scholar]

- Sedgwick, M. 2010. Al-Qaeda and the Nature of Religious Terrorism. Terrorism and Political Violence 16: 795–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D. 2009. Hand This Man over to Satan: Curse, Exclusion and Exclusion and Salvation in 1 Corinthians 5. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J. 2018. Identity and Instrumentality: History in the Scottish School Curriculum 1992–2017. Historical Encounters: A Journal of Historical Consciousness, Historical Cultures, and History Education 5: 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Wilfred Cantwell. 1962. The Meaning and End of Religion: A New Approach to the Religious Traditions of Mankind By. New York: Macmillam. [Google Scholar]

- Temple, W. 1924. Christus Veritas. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, B., and P. Thompson. 2006. The Effective Teaching of Religious Education. Oxon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Winant, H. 2004. The New Politics of Race: Globalism, Difference, Justice. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, A. 1993. Religious Education in the Secondary School: Prospects for Religious Literacy. London: Fulton. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, A. 2004. The Justification of Compulsory Religious Education: A Response to Professor White. Religious Education 26: 165–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Cf., Schaffalitzky de Muckadell (2014) who whilst accepting the “diversity and mutability of religion” (Schaffalitzky de Muckadell 2014, p. 502) argues for an essentialist definition of ‘religion’ as a category: “the fact that religious traditions are constantly changing does not mean that the category ‘religion’ is changing” (Schaffalitzky de Muckadell 2014, p. 503). While not disputing this specific premise, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell’s theoretical argument does not sufficiently engage with religious traditions from a historical perspective: the very phenomena that Schaffalitzky de Muckadell seeks to categorise. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | E.g., Banks concludes that the Law in Matthew 5:17 has the function of “pointing forward to that which as now arrived in its place” (Banks 1974), namely Jesus. In Jesus’ teachings, the Law has been fulfilled, and so transcended (Banks 1974, p. 231). See also Riches: “The intensification of the Law leads to its replacement by a new, more radical, law” (Riches 1996). |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | The move from the term ‘Religious Instruction’ to ‘Religious Education’ is indicative of the subject’s transition from a confessional to a non-confessional conceptualization. |

| 10 | Arts Humanities Research Council. |

| 11 | Economic and Social Research Council. |

| 12 | This ratio resembles the teaching workforce ratio in England, where approximately 75% of the School Teacher Workforce in 2017 were women (Department for Education 2017). |

| Jurisdiction | RE Guidance |

|---|---|

| England | Religious Education provokes challenging questions about: the ultimate meaning and purpose of life; beliefs about God; the self; the nature of reality; issues of right and wrong; and what it means to be human. It can develop pupils’ knowledge and understanding of Christianity, of other principal religions, other religious traditions and worldviews that offer answers to questions, such as these. RE also contributes to pupils’ personal development and well-being and to community cohesion, by promoting mutual respect and tolerance in a diverse society. RE can also make important contributions to other parts of the school curriculum such as citizenship, personal, social, health, and economic, education (Department for Children, Schools and Families 2010). |

| Northern Ireland | Religious Education provides young people with the opportunities to learn about, discuss, evaluate and learn from, religious beliefs, practices, and values. Through Religious Education, young people are able to develop a positive sense of themselves and their beliefs, along with a respect for the beliefs and values of others. The curriculum for Religious Education is defined by the Department of Education and the four main Christian Churches in Northern Ireland in the Core Syllabus. It also has a role to play within the context of the revised curriculum, through presenting young people with chances to develop their personal understanding and to enhance their spiritual and ethical awareness (Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment 2015). |

| Scotland | Religious and Moral Education enables children and young people to explore the world’s major religions, and views which are independent of religious belief and to consider the challenges posed by these beliefs and values. It supports them in developing and reflecting upon their values and their capacity for moral judgement. Through developing awareness and appreciation of the value of each individual in a diverse society, Religious and Moral education engenders responsible attitudes to other people. This awareness and appreciation will assist in counteracting prejudice and intolerance, as children and young people consider issues, such as sectarianism and discrimination more broadly (Scottish Government 2008). |

| Wales | Religious Education in the Twenty-First century encourages pupils to explore a range of philosophical, theological, ethical, and spiritual questions in a reflective, analytical, balanced way that stimulates questioning and debate. It also focuses on understanding humanity’s quest for meaning, the positive aspects of multi-faith/multicultural understanding and pupils’ own understanding and responses to life and religion. Religious education in the twenty-first century consists of an open, objective, exploratory approach but parents continue to have the legal right to withdraw their children. (Welsh Assembly Government 2017) |

| Code | Occurrence | % Total Responses |

|---|---|---|

| Essentialism | 73 | 39.45 |

| Dangerous People | 60 | 32.43 |

| Instrumentalism | 51 | 27.56 |

| Dangerous Interpretations | 43 | 23.24 |

| Religion is not Dangerous | 38 | 20.54 |

| Extremism | 24 | 12.97 |

| Religion can be Dangerous | 21 | 11.35 |

| Absolutely Agree | Moderately Agree | Somewhat Agree | Slightly Agree | Not at all | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q15: Atheist | 7.46% 5 | 11.94% 8 | 22.39% 15 | 31.34% 21 | 26.87% 18 | 18.82% 67 |

| Q15: Agnostic | 1.69% 2 | 5.93% 7 | 28.81% 34 | 27.12% 32 | 36.44% 43 | 33.15% 118 |

| Q15: Theist | 1.75% 3 | 5.85% 10 | 20.47% 35 | 29.24% 50 | 42.69% 73 | 48.03% 171 |

| Code | Occurrence | % Total Responses |

|---|---|---|

| Positive and Negative Presentations | 48 | 35.03 |

| Taught Positively | 30 | 21.89 |

| Criticality | 26 | 18.97 |

| Objectivity | 20 | 14.59 |

| Essentialism | 13 | 9.48 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Smith, D.R.; Nixon, G.; Pearce, J. Bad Religion as False Religion: An Empirical Study of UK Religious Education Teachers’ Essentialist Religious Discourse. Religions 2018, 9, 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9110361

Smith DR, Nixon G, Pearce J. Bad Religion as False Religion: An Empirical Study of UK Religious Education Teachers’ Essentialist Religious Discourse. Religions. 2018; 9(11):361. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9110361

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmith, David R., Graeme Nixon, and Jo Pearce. 2018. "Bad Religion as False Religion: An Empirical Study of UK Religious Education Teachers’ Essentialist Religious Discourse" Religions 9, no. 11: 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9110361

APA StyleSmith, D. R., Nixon, G., & Pearce, J. (2018). Bad Religion as False Religion: An Empirical Study of UK Religious Education Teachers’ Essentialist Religious Discourse. Religions, 9(11), 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9110361