1. Tsai Ming-Liang’s Buddhist Filmmaking: Walker, Xuanzang, and Kinhin

Determining whether to regard a film or filmmaker as Buddhist can sometimes be “tricky business” (

Cho 2009, p. 168). Filmmakers, scholars, and film festival curators alike have shown that the absence of overt Buddhistic themes or references in a film hardly negates the fact that it may well be deeply productive to describe and understand a film as Buddhist (

Green 2014;

Whalen-Bridge 2014;

Cho 2017). Even so, interdisciplinary work in Buddhism and film would do well to remain mindful of the patent yet potentially overlooked point that a filmmaker’s personal confession of religiosity does not always translate into Buddhistically-meaningful work. Within the world of transnational Chinese cinema, the varied films of Chen Kaige and Tsui Hark, both self-avowedly devout Buddhists, are a case in point.

Tsai’s oeuvre, though, does not present such difficulties for the study of Buddhism and film. Since the start of his career in the early 1990’s, the prolific Malaysian-Taiwanese auteur has consistently affirmed the definite influence of Buddhist religiosity on his works (

Peranson 2002). In tandem with these affirmations, Song-Hwee Lim highlights the Buddhist symbolic discourse on transience and transmigration in films like

The River (1997) and

What Time Is It There? (2001) (

Lim 2014, pp. 107–12). More recently, Tsai has given a distinctly religious

raison d’etre behind his making of

Face (2009): “I wanted to look at western religious art from the perspective of a Buddhist: ‘all activities are impermanent, all dharmas are non-self, nirvana is tranquil cessation’—this is the state that I most hope to attain with this film” (

Sina Entertainment 2008).

1 Tsai’s verbatim citation of the

sanfayin (Chi: “three seals of the dharma”) from the Chinese

Samyuktagama Sutras demonstrates his deep engagement with Buddhist understandings of

anitya (Skt: “impermanence”),

anatman (Skt: “no-self”), and samsaric liberation in his filmmaking.

Walker is the second and eponymously representative film within Tsai’s “Walker” series, which features the same figure of a Buddhist monk performing walking meditation in diverse locales around the world. Beginning with

No Form (2012), the series now also includes

Diamond Sutra (2012),

Sleepwalk (2012),

Walking on Water (2013),

Journey to the West (2013), and

No Sleep (2015).

Walker was officially released as a “micro film” (

wei dianying) on Youku, one of China’s leading video-hosting platforms. Other films in the series have been screened as feature-length films, performance art, and video installations in film festivals and art biennales. In collaboration with respective local filmmaking, cultural, municipal communities, Tsai has shot these films in Taipei, Hong Kong, Kuching, Marseille, and most recently, Tokyo, and hopes to continue shooting in major cities across the globe. Besides illustrating the global nature of Tsai’s cinematic production, the “Walker” series reflects the long-standing adaptability of Buddhist media, an adaptability evinced in the oft-neglected fact that a CE 868 copy of the

Diamond Sutra (which one of Tsai’s films explores) stands as the oldest extant printed book in the world today (

Grieve and Veidlinger 2017, p. 469).

Tsai’s inspiration for

Walker arose from the figure of Chen Xuanzang (602–664), the Tang dynasty (618–907) monk famed for obtaining and translating Buddhist scriptures from India, and whose arduous, intrepid travels are colorfully mythologized in Wu Cheng’en’s (1640–1715) classic novel,

Journey to the West. In an interview with

Film Comment magazine, Tsai explains:

The reason why I wanted to do something like the

Walker series is rooted in my obsession with the idea of Xuanzang, and the characteristics of the times he lived. There was no car, no train, no airplane, and no cell phone. He just walked (

Chen 2015).

From a Buddhist perspective, Tsai’s fascination with the idea that Xuanzang “just walked” parallels the Japanese Zen patriarch Eihei Dogen’s (1200–1253) notion of “just sitting” (

shikantaza) as a means of realizing enlightenment in this world (

Abe 1992, p. 11). Specifically, the walker’s performance of “just walking” draws explicitly from kinhin, the Zen practice of meditative walking. The Japanese term kinhin comprises two

kanji (Chinese characters). Ideographically signifying the passing of thread through a loom, as a verb

kin (経) means “to traverse” or “to pass by,” and as a noun it means “scripture” or “sutra.”

Hin (行) refers to the act of traveling or walking. It also refers to Buddhist practice (

Riggs 2008, p. 228) and more generally (as in the first phrase of the

sanfayin) to any mode of phenomenal activity. Robert Aitken notes that the binome kinhin literally means “sutra-walking” and suggests that “our everyday actions are themselves sutras” charged with liberative potential for ourselves and others (

Aitken 1982, p. 36).

The historical roots of kinhin qua Zen practice

par excellence may be traced to two texts by the Soto Zen monastic-scholar Menzan Zuiho (1683–1769): the

Kinhinki (“Standards for Walking Meditation”), a short introduction to the practice; and the

Kinhikimonge (“An Explanation of the Standards of Walking Meditation”), a lengthier commentary that seeks to establish kinhin’s canonicity by fabricating an unbroken lineage all the way back to Gautama Buddha via texts like Dogen’s

Shobogenzo (“Treasury of the Eye of the True Dharma”), the

Avatamsaka Sutra (“Flower Garland Sutra”), and the

Lotus Sutra. Interestingly, through his reading of the

Zoku Kosoden (“Further Biographies of Eminent Monks”), a Tang dynasty text which records Xuanzang’s life and achievements, Menzan includes Xuanzang in this lineage. He avers that while in India Xuanzang saw “old traces” and “stone foundations” of the historical Buddha’s kinhin practice (

Riggs 2008, p. 245). Working to balance canonical fidelity with hermeneutical creativity, Menzan declares that the authentic dharma transmission reveals the Buddha as the “Tathagata of the Boundless Tranquil Slow Walk” (

Riggs 2008, p. 235). He also argues that kinhin practice is identical to “treading the splendid path taken by the Tathagata,” whose archetypal walking on earth stemmed from his resolute “wish to benefit and comfort all sentient beings” (

Riggs 2008, p. 234). As we shall soon see, with an adaptive fidelity comparable to Menzan’s reading of canonical scriptures, and in keeping with the priority accorded to ocular, visionary experience in Mahayana Buddhism (

McMahan 2002),

Walker performatively visualizes kinhin via film media to beneficently embody the dharma in modernity.

Tsai further explains that he imagines the peripatetic Xuanzang as a “rebel” who protests the status quo with admirable “solitude, stubbornness, and stupidity” (

Chen 2014;

Kramer 2015). In

Journey to the West—as well as in the popular Chinese imagination—Xuanzang is often known as a timid, indecisive, and legalistic monk whose pilgrimage is commissioned by the imperial court (

Wu 2012, p. 276). However, the historical Xuanzang significantly corresponds to Tsai’s image of him. Anthony C. Yu observes that during the early years of the Tang dynasty, when ordinary subjects were forbidden from traveling beyond state frontiers, Xuanzang’s travel to India was an act of bold “religious defiance against the Chinese state” (

Yu 2009, p. 195). Moreover, Xuanzang’s zeal to acquire and translate Buddhist wisdom from India demonstrates his conviction that the dharma was essential for both the well-being of the Chinese people and the spiritual transformation of Chinese culture (

Yu 2009, p. 192). With similar counter-cultural intent, Tsai employs the trope of Xuanzang’s walking as a foil against what he sees as the excesses of the modern world.

2. On Speed and Slowness: Buddhism in Counterpoint to Modernity

Walker depicts a robed monk practicing kinhin in different locations around the city of Hong Kong. Excluding the opening title and end credits, the film runs for 24 min. It consists of just 21 shots spanning 16 scenes. This ratio translates to an average shot length (ASL) of 69 s—up to 35 times longer than the current Hollywood ASL of 2 to 6 seconds (

Bordwell 2006, pp. 122–23).

Walker opens with a 129-s long shot of the walker descending a dim, dilapidated stairwell very slowly. With his back toward the camera, he moves silently toward the busy street below; the noises of the ambient traffic are the only sounds we hear. We next see him inching by a building wall completely plastered by a colorful, haphazard panoply of paper advertisements, right as someone is finishing with putting up a new poster. This second shot shows the walker clutching a white, round item in his right hand and a small semi-translucent plastic bag in his left, but we cannot determine what the item is nor what the bag contains. Subsequently, his day journey takes him on a glossy overhead bridge in the Central business district, through the crowded folk religious marketplace of Goose Neck Bridge in Wan Chai, and into a bustling thoroughfare in the Mongkok shopping area.

The walker’s voyage continues into the evening, leading him past a stationary, ditty-playing ice cream van; under the roof of a bright-lit tram stop; and across an old overhead bridge, emptied of human presence apart from the nighttime cleaners briskly spray-washing the pavement. In the penultimate series of shots, we see him edge by rows of parked minibuses and taxis, bundles of to-be-recycled paper, and stacks of newspaper awaiting delivery at dawn. We are also finally able to see exactly what he has been holding all along: The item in his right hand is a typical Hong Kong-style bun, while the bag in his left hand contains a disposable plastic cup, presumably containing milk tea. The final scene sees his perambulation coldly halted before the locked grills of a building. Via an unprecedented close-up, the film’s concluding shot reveals the walker’s facial features for the first time. As the non-diegetical soundtrack of a 1970s Cantonese ballad starts, the walker progressively raises the bun to his gaping mouth. With the same extreme unhurriedness that has characterized his journey up till this point, he bites into the bun, and chews on it.

Beginning during the day and ending right before the dawn of a new day, the sequence of scenes in

Walker bespeaks a certain teleological trajectory. In this way, its narrative arc parallels the play on journeying and

telos in

Journey to the West, a masterwork of religious fiction whose allegorical dimensions have been duly observed by scholars (

Plaks 1987;

Cho 1989;

Yu 2009;

Hui 2015). However, while the novel’s Buddhist allegory is mostly conveyed via wordplay, dramatic narratives, and action-filled sequences, the film’s central aesthetic and religious vision lies undoubtedly in its slowness. Tsai affirms that

Walker is “very much about the spiritual aspect” and describes his motivations for shooting the spectacle of kinhin in the following way:

Why should I film this? It’s because your lifestyle needs to be changed. My health is getting worse. You have to change your life tempo, and that’s why I moved to live in the mountains. In the mountains, you feel time. In the mountains, you feel time. Time is slowly fleeting. Wind blows and cloud moves. You can see time. Many people cannot see this, because they only see work, or all kinds of talking. They never stop (

Chen 2015).

Like the Romantic poets who envisioned themselves as prophetic seers of their age, Tsai seeks, via a filmic vision of hyper-slowness, to question and ameliorate the numbing, detrimental results of high-pressured living. His entire oeuvre, in fact, bears the unmistakable traits of slow cinema, a film style characterized by very long takes, attention to the quotidian and the natural, fixed camera or minimal camera movement, and direct sound from the environment (

Lim 2014, pp. 1–2). Abbas Kiarostami, Hou Hsiao-Hsien, Alexander Sukorov, and Apichatpong Weerasethakul are some other prominent contemporary auteurs whose works demonstrate the same stylistic tendencies. In a study of cinematic slowness in Tsai’s oeuvre up till 2009, Lim frames the rise of slow cinema around the millennium’s turn within the broader context of the Slow Movement, a worldwide sociocultural revolution against the “cult of speed” that has driven globalizing modernity to frantic dis-ease. He suggests that like the Slow Movement, slow cinema constitutes “an attempt not only to counter the compression of time and space brought about by technological and other changes, but also to bridge the widening gap between the global and the local under the intense speed of globalization” (

Lim 2014, p. 5). These trenchant insights both inform and compel our analysis of the convergence of the aesthetics of slowness, cultural critique, and Buddhist religiosity in

Walker.To begin with, the walker’s very

form stands in prophetic counterpoint to the enterprise of modernity. His vermillion robe, bald pate, and bare feet are starkly juxtaposed against the backdrop of neon-lit billboards and towering skyscrapers bespeaking Hong Kong’s position as a global economic hub. In contrast to the cellphones and cameras sported by numerous passers-by, the humble bun and plastic cup in the walker’s hands call to mind the alms bowl carried by mendicant monks, intimating the simplicity and poverty of the renunciate life.

2 By his sheer presence in the Chinese metropolis, he functions as a living icon of the Buddhist tradition in the contemporary world. The walker’s iconic import is underscored by the fact that he remains anonymous and itinerant throughout the film. As he makes his way through a deserted street lined with stacks of waste paper after dark (see

Figure 1), he cuts a poor and lonely figure, embodying the ascetic ideal of the homeless wanderer that has been one of the most “defining features of the history of Buddhist monasticism” (

Gethin 1998, p. 99). Even so, although looking quite out of place during the hustle and bustle of every day, he seems placidly at home in the city at night, when most human activity has come to a cessation.

More pointedly, as an incarnation of Tsai’s archetypally peregrinatory and rebellious Xuanzang, the walker’s

performance of kinhin proceeds in contradistinction to modernity’s fixation with speed, progress, and efficiency. At first blush, the camera’s patient, detached observation of kinhin appears charged with a documentary realism reminiscent of Ron Fricke’s

Baraka (1991), which contains a segment that carefully captures a Japanese Zen monk practicing kinhin. Yet, even before

Walker’s closing shot discloses the monk’s facial features, viewers familiar with Tsai’s work would doubtlessly surmise that the walker is portrayed by Lee Kang-Sheng, the Taiwanese thespian who has played the lead in all of Tsai’s films. Given that the film’s kinhin is performed by a professional actor who is virtually a signature of Tsai’s auteurship, it is more fitting to view

Walker as illustrating the “poetics of documentary,” a mode of “active making” whose recording of the putatively objective is inseparable from interrogatory, persuasive, and expressive intent (

Renov 1993, p. 21). Like the irreverent, iconoclastic Zen masters who “play to an audience and aim to affect it in some immediate way,” the walker may be rightly seen as a performance artist whose walking meditation in the city seeks to capture our cognitive attention and trigger an affective response (

Cho and Squier 2016, p. 100). At the same time, by featuring an actor “playing” a monk,

Walker serves as a liminal space where the conventional line between reality and fiction is meaningfully blurred: While on one level Lee is indeed “just” portraying a monk, if all identities are empty of essence, is he not on another level “really” being a monk? In this way, the film effectively mimics the Zen dictum that anyone can performatively become a Buddha in a single instance, “just as they are” (

Cook 1989, p. 21).

Understanding the kinhin in the film as a performance involves approaching it as a “specific ethnographic instance” that varies on the “general model” of traditional walking meditation (

Bell 1998, p. 215). It also involves paying attention to “the movements of the body in space and time, notably the way these movements define a total cosmic orientation” (

Bell 1998, p. 216). Recalling that Menzan himself created “something new out of fragments of unrelated texts scattered across continents and millennia of Buddhism”, a closer look at his now canonical writings helps uncover the performative creativity—and fidelity—of the kinhin in

Walker (

Riggs 2008, p. 252). For Menzan,

the way of kinhin that is to be wished for is to clasp both hands in front of the chest [isshu] (it should be just like this), putting them inside the sleeves, and not letting the sleeves fall down near the feet to the right and left. Look directly one fathom ahead (about six or seven feet). When walking properly, use the breath as measure: a half step is taken in the time of one breath (in and out) (

Riggs 2008, pp. 233–34).

Tsai’s walker does not conform to these established rules. Rather than being clasped in front of his chest and tucked inside his sleeves, his half-outstretched hands hold a bun and a plastic bag. Instead of looking straight ahead, his head is acutely angled downward, as if he were looking at the ground right beneath him. While it may be hard to determine exactly how long Menzan thinks a meditative breath should take, and while the speed of kinhin can vary by tradition and subtradition, it seems that the walker’s pace—about 40 s for a single step with one foot—is much slower than what it would normally be.

3Yet, method may be discerned in the walker’s ostensibly contrarian madness. Menzan was a “reactionary innovator” of monastic regulations who aimed not only at recovering the uncorrupted teachings of Dogen, but also at combatting the influences of the Obaku sect, a separate lineage of Zen transmitted from Ming China (1368–1644) that had become increasingly popular in Japan during Menzan’s time (

Riggs 2008, pp. 225–27). In the

Kinhinkimonge, he explicitly expresses his wish for walking meditation to be practiced in line with “the house standard of the serene, hidden way of our ancestors” instead of the “uncouth ways of other schools” (

Riggs 2008, p. 239). In particular, Menzan criticizes the way that some contemporary monastics chanted loudly and walked in circles while attempting

kinhin. In his book, such habits conditioned practitioners to move about “quickly and in a frenzy” and caused them to “bustle around like dogs and horses” (

Riggs 2008, p. 239). In effect, Menzan’s rules functioned in polemical resistance against what he saw as heterodox visions of ritual power, social arrangement, and cosmological reality.

In the spirit of the

Kinhinki, which warns its readers to “not drift into the bustle of the practices of another family,”

Walker proposes an alternative to the hectic immoderations of modern life by approaching the conventional standards of walking meditation with creative fidelity (

Riggs 2008, p. 233). Where the rule of looking ahead aimed at fostering meditative focus, Tsai’s walker squarely casts his gaze downward, oblivious to the countless advertisement posters, signboards, and digital screens bespeaking consumerist distraction. With a touch of self-reflexivity, the shot of him on Mongkok’s Sai Yeung Choi shopping street—a permanently pedestrianized street when the film was made in 2012—shows him performing kinhin specifically on a crosswalk (see

Figure 2). In this way, the film “focuses on the ground” and “discloses the hustle and bustle of the city [in] counter-consciousness to this business” (

Finnane 2016, p. 127). Further, where Menzan’s admonition to “go straight ahead and return straight” directly opposed the Obaku ritual of circumnavigating effigies of the Amida Buddha, the walker roams across Hong Kong without any obvious agenda or destination (

Riggs 2008, pp. 234, 243). In sharp distinction to the busy, purposed pacing of other pedestrians, the walker’s aimless kinhin evokes the levity of the proto-Zen Zhuangzian sage who “wanders free and easy in the service of inaction” (

Watson 2013, p. 50).

The countercultural slowness of kinhin emerges in distinct relief against myriad modes of mechanical transportation. Right as the film’s opening title appears, we hear a vehicle engine starting up, foreshadowing the ubiquitous sound of motor traffic that hums in almost every scene. As the walker journeys across the city, cars, taxis, buses, trams, and motorcycles zip by him from various angles and directions. Typically, the vehicles run parallel to him in the same or opposite direction. In an arresting close-up of the walker on the overhead bridge, the traffic beneath him flows in a perpendicular direction. In other shots, such as those of him walking under a tram stop or descending the lighted steps of a mall-like building, our view of him is periodically blocked by vehicles stopping either directly before the camera or right in front of him (see

Figure 3). Visually, the automobiles in the film weave their way through the city geographically and around the walker. Building on the conceptual link between the Chinese ideogram for “sutra” and a loom, we might say that in contrast to the dizzying ideology of speed animating the city’s vehicles and surrounding the walker, the latter’s “sutra walking” composes a dissenting sutra of steady, constant slowness. As David Eng perceptively observes, “although always in transit, he remains the least transitory figure within each frame as he is repeatedly surpassed by vehicles” (

Eng 2014).

Indeed, whereas Menzan advises that kinhin be practiced in a “quiet place” within the monastery, the walker brings an oasis of quietude into the restive clamor of the city, grounding each shot with a still, meditative presence (

Riggs 2008, pp. 242, 244). In Zen iconographic terms, the solitary, stubborn simplicity of Tsai’s walker (qua Xuanzang) recalls the figure of a bull, whose movements allegorize “steps in the realization of one’s true nature” (

Reps and Senzaki 1994, p. 241). This brings us to a core aspect of the Buddhist discourse at work in the film’s slow aesthetics. In Mahayana Buddhism, liberation is attained not by active striving, but rather by awakening to the reality of the

tathagatagarbha (Skt: “matrix of the Thus Gone”), that is, the Buddha Nature inherent in all things. For Dogen, this innate Buddhahood is paradigmatically realized through zazen or sitting meditation. Given the indivisible “oneness of practice and attainment” (Jpn:

shusho itto), the practice of sitting actualizes the enlightenment that one already possesses. But for Menzan, the act of walking becomes the chief performative embodiment of Buddha nature. According to David E. Riggs, Menzan’s focus on kinhin plays upon an alternative reading of

kanji characters that, in their broader usage within the Japanese Buddhist context, simply refers to the four basic physical positions that the Buddha himself took (

Riggs 2008, p. 224).

4 Just as both Dogen and Menzan locate the site of enlightenment in fundamental postures of the human body, Tsai sacralizes the act of plain, aimless walking, exemplifying the Soto Zen view that “attainment is a no-attainment. It is not the result of aiming at anything” (

Williams 2009, p. 122). In contrast to the city and its denizens, whose restless activities signal the pursuit of all things bigger, better, and faster,

Walker embraces the virtues of non-striving simplicity and contentment. It calls into question the obsession with “getting somewhere” and invites a consideration of how we might already possess all that we could possibly need and desire. However, the nature and content of exactly what the film suggests that we already possess awaits further explication.

3. Slowness as Seeing: A Pedestrian Dharma for Suturing the “Wounds of the Modern”

“We walk all the time,” Thich Nhat Hanh writes, “but usually it is more like running. Our hurried steps print anxiety and sorrow on the Earth” (

Nhat Hanh 2001, p. 33). And for the restless and incessant mobility of life in the modern world, he recommends walking meditation as an antidote: “Life is here, in each step. For this reason, we must walk in such a way that life arises out of each step” (

Nhat Hanh 2006, p. 83). Thich Nhat Hanh’s vision of walking meditation provides a useful starting point for investigating how Buddhism is harnessed to “suture the wounds of the modern” in

Walker. Given Tsai’s concerns about modernity’s insalubrious fetishization of speed, in what ways does the film’s aesthetics of slowness present a healthier alternative to what Enda Duffy calls “speed’s prospect of vitality” (

Duffy 2009, p. 7)? How does life “arise out of each step” that the walker takes, and what exactly does this vision of human life and liveliness constitute?

The context in which

Walker was produced affords a crucial inroad to understanding its Buddhist therapeutic aesthetics. Besides being the second installment in Tsai’s Walker series, the film was made under commission from Youku and the Hong Kong International Film Festival (HKIFF) as part of a four-part omnibus entitled

Beautiful 2012 (2012). There are currently five such omnibuses, each released in conjunction with the annual HKIFF from 2012 and 2016. Boasting contributions by master filmmakers like Christopher Doyle, Gu Changwei, Ann Hui, Kurosawa Kiyoshi, and Wu Nien-jen, the films in this series are united in their attempt to probe, enlarge, and enrich notions of beauty in various contemporary East Asian contexts. The omnibus’s Chinese title,

Meihao (美好), denotes happiness and wonderfulness, and is composed of two characters that mean “beautiful” and “good.” Thematically, these works share an interest in the connections between beauty and what Greek philosophers call

eudamonia, the good life marked by felicity and flourishing. One film curator, for instance, writes that the

Beautiful 2012 omnibus “wrests moments of rapture from unexpected places” and stands as a “testament to courage and an exhortation to follow one’s joy” (

Mizota 2013).

For Tsai, this vision of human flourishing can be attained through the aesthetic appreciation of phenomena. In an extensive interview with the Museum of the Moving Image, he describes his approach to shooting the Walker series in the following way:

It’s like when a painter goes out to paint a still life. Have you ever heard of a painter planning or conceptualizing anything before going out to paint a still life? He paints what he finds and sees. Because the world is so

full of wonders, one can never run out of subjects to paint. Why deliberately worry or challenge myself (

Pinkerton 2015; emphasis mine)?

When read alongside Tsai’s aforementioned interview with

Film Comment, these words indicate the conflation of therapeutic intent, artistic creativity, and the act of seeing in the Walker series. In likening his filmmaking to the process of painting, the Buddhist auteur follows faithfully in the footsteps of Dogen, who unequivocally affirmed the liberative potentials of aesthetic media.

5 Within the Mahayana tradition, enlightenment involves awakening to the truth of emptiness (Skt:

sunyata), that is, to the contingent, interrelated, and ontophenomologically co-constructed character of all phenomenal form. By virtue of its nature as imaginative fabrication, all forms of art serve as a felicitous medium for cultivating such an awakening. For this reason, Dogen states that “all Buddhas are paintings of Buddhas, and all paintings of Buddhas are the [real] Buddhas… the supreme

bodhi itself is also a picture. The whole universe of things and space are nothing but a picture” (

Cook 1989, p. 80). It is also for this reason that

Walker stands as a companion piece to the antecedent

No Form, the first film in the Walker series whose title plainly refers to the Mahayana view of the emptiness of phenomena.

Precisely because enlightenment sees mind and matter as non-dual, Tsai’s Buddhist filmic imagination seeks its home in the world as it is, finding what it means to be “full of wonders.” In his seminal study of the confluence of religion and the literary arts in medieval Japan, William LaFleur notes that Buddhist poet-seers of that age saw that “our greatest loss lies in failing to see the natural things near at hand and before our eyes”. Whether via verse, prose, or drama, these religious artists conveyed their sense that “the mundane is not so much evil as it is spiritually dangerous,” insofar as thoughtless routine often lulls us into “a world of settled but seriously impaired sight”. In particular, LaFleur contends that works like Matsuo Basho’s (1644–1694) Narrow Road to the Far North exemplify how “the advantage in world rejection lies in the mobility it provides and the clairvoyance that comes from this”. Like Basho’s masterwork of religious pilgrimage, Walker employs both poetics and pilgrimage as means of disrupting the illusion of stability and permanence. But, whereas Basho looks to the natural environment as a place of insight, Tsai fixes his filmic gaze firmly on the modern world and turns the very site of spiritual occlusion into an arena for awakening.

To Tsai, the “wounds of the modern” may be traced not so much to some essential ideology of modernity

per se, but rather to certain mental habits and tendencies that have become habitual to contemporary lifeworlds. And to “suture” these wounds, what his Buddhist filmmaking seeks to transform is our

experience in and of the modern world. “In true Buddhist fashion,” he explains, “I want my films to be like the moon, a beautiful flower, a gurgling stream… I want them to be seen and experienced” (

Biswas 2014). Besides alluding to the notion of

jinghua shuiyue (“flower in the mirror, moon in the water”)—a classical Chinese poetic trope for the illusory nature of things—Tsai’s stress on the experiential dimension of his film aesthetics further parallels Dogen’s appraisal of the liberative powers of our mental and imaginative faculties: “Grass, trees, and lands are mind; thus they are sentient beings. Because they are sentient beings they are Buddha-nature. Sun, moon, and stars are mind; thus they are sentient beings; thus they are Buddha-nature” (

Olson 2005, p. 347).

For Menzan, the discipline of slow walking meditation reaps physical as well as spiritual benefits. He states that kinhin serves to “revive one’s spirit [and] to revitalize,” and brings increased energy, stamina, digestive and overall health, and in and through all these,

samadhi or single-pointed meditative absorption (

Riggs 2008, p. 244). On one level,

Walker seems to also commend the physical benefits of kinhin as remedy to modernity’s unwholesome pace of life. With the uncanny visual perceptivity that characterizes Tsai’s auteurist eye, the film deftly captures the symptoms of physiological malaise dotting the city. For example, the tram stop that the walker passes under in the evening is covered with advertisements for what looks like an insomnia medicine (see

Figure 4). The signboard slogan reads: “Spring, summer, autumn or winter, rain or shine—every day can bring a peaceful night.” In the original, the phrase “peaceful night” is

ping’an ye (平安夜), the exact Chinese title of the well-known Christmas hymn,

Silent Night. Might Tsai be obliquely comparing the city-dweller’s quest for rest to the Christian hope for messianic peace? In this scene, the walker also finds an arresting foil in an older lady who hobbles unwittingly into the shot. For almost 20 s, the two of them are the only persons at the stop, composing an odd showdown of sorts as each makes their way laboriously in the direction of the other. While the walker’s hyper-slow gait is a result of countercultural choice, the lady’s severe limp (from what might be bow legs) poignantly evokes not only the plight of those left behind by the modern rat race, but also the inescapable facticity of old age and human sickness, two of the four sights that led to Gautama’s “great going forth” (Skt:

mahapravrajya).

On another level, however,

Walker primarily commends the

viewerly experience of kinhin as a means of attaining spiritual insight. Just as every infinitesimal step that the walker takes demands his utmost focus, we are likewise invited to summon deep concentration to observe the objects and occurrences within each shot. The act of contemplatively watching the film mimics the practice of meditation, which is itself “a kind of internal cinema of the mind that aims to vivify what the tradition takes to be ultimately real” (

Cho 2009, p. 136). In the

Visuddhimagga (“Path of Purification”), a foundational manual of Buddhist meditation, Buddhaghosa (fl. 5th century) describes

samadhi as the state in which the consciousness “remain[s] evenly and rightly on a single object, undistracted and unscattered” (

Buddhaghosa 2010, p. 82). He lists death, decompositional stages, one’s own breathing, and various

kasinas (Pali; “devices” or heuristic images) as suitable items and subjects for centering concentration. In much the same way, within each frame, the walker himself serves as an ideal object of viewerly focus. For a viewer watching the daytime scenes, the incessant flow of human and motor traffic captured on film can be a formidable source of distraction. Conversely, for the nighttime scenes, the challenge comes from staying watchfully focused even when it might seem or feel like nothing is happening on screen. But regardless of the nature of the distraction, the walker remains a constant in every single shot. “As we witness the Walker’s presence from various perspectives and vantage points,” Eng observes, “his body becomes an anchor around which each scene will coalesce” (

Eng 2014). In this respect, the walker acts as a

kasina for guiding and grounding meditative centeredness, perhaps akin to the way the base of a tilting doll always returns the doll to postural equilibrium.

6Much of the time, the walker is foregrounded in a shot and immediately visible. It is also usually not difficult to recognize the milieu that the walker is traversing. For instance, there is little doubt that the film’s opening two shots respectively show the walker making his way down a flight of stairs in a building, then in front of a patch of wall plastered with property advertisements. However, like incremental stages of meditative practice, many subsequent shots require greater cognitive and contemplative effort before we are able to locate the walker or make better sense of the

mise en scène. Recalling Buddhaghosa’s instructions for the expressly “bounded” and “circumscribed” form of certain heuristic

kasinas (

Buddhaghosa 2010, p. 117), these scenes bid us to dwell even more patiently within the frame. Each shot comes as a visual field awaiting phenomenological grounding. In one of the evening scenes, for instance, a high angle extreme long shot (see

Figure 5) shows the walker dwarfed and hidden by surrounding buildings as he creeps along a scaffolded pavement. But this shot turns out to be a prelude to the more significant ocular riddle that ensues.

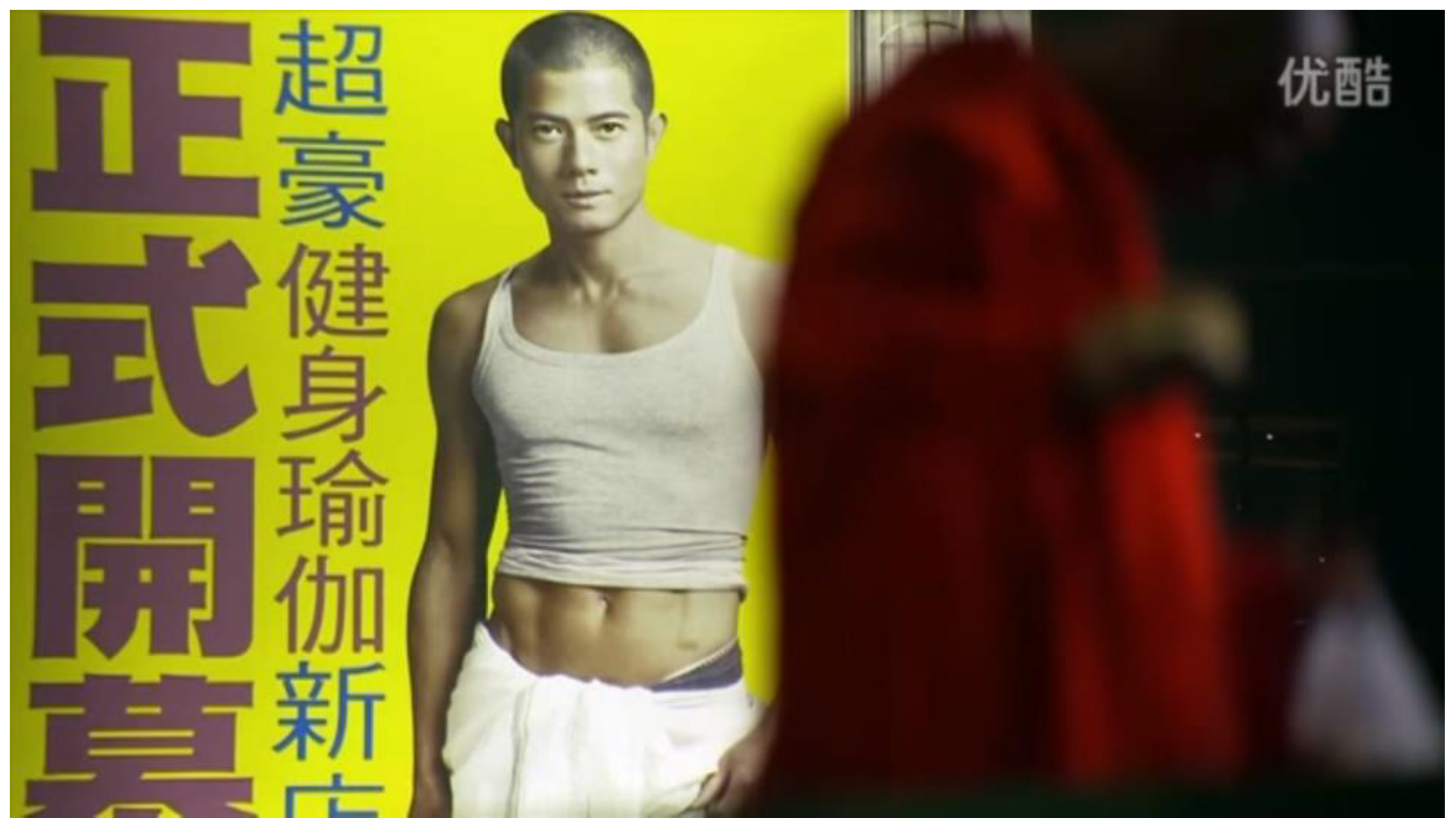

Via what nearly constitutes a bird’s eye view shot of Queen’s Road Central (see

Figure 6), an avenue flanked by commercial buildings, Tsai beckons the viewer to participate in his playful variation on

Where’s Waldo? In this shot, the walker is reduced to such a miniscule scale that one would probably need to scan the entire screen carefully to spot him. The natural darkness of this night scene leads us to look even more intently. To the right of the shot, there is the glassy, futuristic-looking façade of The Center, one of Hong Kong’s tallest and most iconic skyscrapers. To the top, an enormous billboard looms in the distant background, announcing via a yet-unidentifiable model the official opening of some facility. To the bottom and center of the shot, the concrete pavement leads to an august, verdant tree, an unlikely oasis in the middle of the urban jungle. And to the left, a few pedestrians are waiting for taxis as a lit signboard goes off. Here, we finally find the walker, virtually frozen in hyper-slow walking meditation.

On the one hand, the walker’s anchor-like presence in preceding shots has conditioned the viewerly eye to search for him within the frame. On the other hand, the tininess and stillness of his figure in this shot conveys an inverse sense that “the actor, as such, can be absent from [the screen], because man in the world enjoys no a priori privilege over animals and things” (

Bazin 2005, p. 106). As further conveyed through the film’s consistent use of deep focus, in which all the elements within the frame are in equal focus, there seems to be no essential reason why we need to observe the walker more carefully than anything else that appears on screen—whether animate or not, and even whether in this scene or others. The shot composition here appears as a visual analogue for the Zen paradigm that there is “nothing special” to enlightenment, a paradigm enacted in the walker’s own practice of kinhin. Like the practice of body-scan meditation, the exercise of scanning the screen to locate the walker—and letting go of whatever phenomenological priority that may have been hitherto accorded to him—is “tantamount to cultivating moment-to-moment non-judgmental awareness” (

Kabat-Zinn 2013, p. 80). These phenomenological movements, in turn, work to restore a tone of openness, curiosity, and wonder to a viewerly appreciation of pro-filmic phenomena. In this way, the philosophical aesthetics of

Walker accord with Jon Kabat-Zinn’s understanding of how meditation reenchants our vision of reality: “When you understand ‘nothing special,’ you realize that everything is special. Everything’s special and nothing’s special… It’s how you see, it’s what eyes you’re looking through, that matters” (

Kabat-Zinn 1995, p. 114).

The film’s perspectivism becomes more pointed in the zoom shot that immediately follows (see

Figure 7). From being an inconspicuous blip on the screen, the walker starts to fill up to half the screen while moving ever so slowly from the left to the right of the frame. Yet, for the first and only time in the film, he is out of focus; the shallow depth of field keeps the billboard behind him in sharp focus instead. On closer scrutiny (or repeated viewing), it turns out that the billboard is the one that featured in the prior quasi-bird’s eye view shot. We now see that the advertisement announces the opening of the new branch of a trendy yoga studio, and that the buff model is none other than Aaron Kwok, a Hong Kong superstar singer/actor who first rose to fame in the early 1990s. During the opening launch of

Beautiful 2012, Tsai explained that while making

Walker, one of the perspectives he tried to adopt was that of a local Hongkonger observing things in the city that were interesting (Chi:

youqu de) or laden with feeling (Chi:

youganqing de), or that may have disappeared or persisted over time (

Youku 2012). In this light, it becomes clear the transitional zoom aims to help us observe afresh things that city-dwellers may have grown accustomed to, such as the popularity of yoga in contemporary Hong Kong, or the impressive longevity of Kwok’s career and physique. By ingeniously framing the shot such that (the image of) the artiste and the walker are of the same size, the film evokes the camera tricks of Dziga Vertov’s

Man with a Movie Camera (1929), which aim to render “the presentation of even the most ordinary things [with] exceptionally fresh and interesting aspect” (

Vertov 1984, p. 19). At the same time, the fact that within the frame the walker is no more “real” than Kwok—both are performers whose images we see via visual media—suggests the Buddhist view of the non-duality between the physical world and its artistic representation.

Tsai’s Buddhist discourse on non-dualism, perspectivism, and the possibilities of reenchantment in modernity comes to a fore in the two-shot sequence of the walker on the busy overhead bridge connecting World-Wide House, Jardine House, and Exchange Square. From a distant, external vantage point, the first shot observes the constant flow of human traffic on the bridge located in the Central Business District (see

Figure 8). The top and bottom of the screen are mostly filled by the structure’s still façade. Fast-moving silhouettes of pedestrians are visible through a slim window running horizontally across the frame. Readily distinguishable by his bowed head and slow gait, the walker represents a Buddhism that exists in contrapuntal relief to the relentless pace of modern global commerce. Even so, when read within the context of this two-shot scene, it becomes apparent that Tsai does not envision the walker’s meditative path proceeding in simple contradiction to or negation of modernity.

In the second shot, we see the side profile of the walker’s face close-up as pedestrians pass him by in the background (see

Figure 9). Like in the previous shot, the movement of these figures is observable through a horizontal “window” of activity that straddles the middle of the screen. Cued by the flow of motor traffic to the bottom right of the frame, though, it soon becomes apparent that we are in fact looking at the walker’s

reflection on the railing. Given that in the prior shot it was the surrounding skyscrapers that were reflected (on the façade of the bridge), this realization can prove both bewildering and intriguing. Like in a hall of mirrors, conventional views of illusion and reality are playfully upended here. Complementing the film’s use of an actor to play the role of a monk, this sequence betokens how the Buddha “is neither a mental projection nor something that is ontologically other but rather exists in the betwixt-and-between space of play” (

Sharf 2005, p. 267). If Robert Sharf is right that the “ritual constitution of Buddhahood in play” indicates how “all social forms of life are play,” then Tsai seems to be proposing that no

essential difference lies between the movements of modernity (whether religious, economic, transportational, or otherwise) and the walker’s ritual movements; the modern metropolis itself, like the walker’s own body amidst the film’s various vehicles, can serve as the very vehicle for liberative play (

Sharf 2005, p. 259). Most strikingly, the composition of both frames in this sequence—a symmetry of lines and boxed spaces—bears a stark resemblance to strips of film stock and intimates the role that the filmic imagination can play in the therapeutic reenchantment of and

in the modern world. From here, it would probably not be too fanciful to propose a semiotic link between the film reel and the prayer wheel—and that the turning of the reel can generate similar liberative merit for viewers.

Having traversed the myriad terrains of the city, the walker’s journey finally comes to a stop in the penultimate shot. Flanked by two stacks of undelivered newspapers that signal an impending dawn, he finds himself halted in front of firmly-locked metal grills. To the extent that the walker’s journey hitherto this point has partaken in the toils and travails of modern life, his stopping before a “NO ENTRY” sign—like the empty scriptures that Wu Cheng’en’s Xuanzang initially obtains when he finally arrives in India—allegorizes the Zen dictum that one need not search or travel far for deep meaning and fulfilment. In the walker’s decisive stillness, he embodies an admonition from Linji Yixuan (fl. 9th century) that applies as much to moderns as it does to monastics: “What are you seeking as you go around hither and yon, walking until the soles of your feet are flat? There is no Buddha to seek, no Way to attain, no Dharma to obtain” (

Sasaki 2009, p. 27).

Accepting that he can proceed no further than where he already is, in the last shot the walker begins to eat the bun that he has been holding in his hand all this while (see

Figure 10). In his slow, simple mastication, the “prospect of vitality” (

Duffy 2009, p. 7) and “heightened, intensified way of life” (

Jones 1915, p. 157) driving the modern fetishization of speed finds an alternative

telos in what we might call the mysticism of the mundane. Here, Tsai is in concert with contemporary proponents of mindful eating, who identify this practice as an ideal path through which human appetites can “be transformed from a source of suffering to a source of renewal, self-understanding, and delight” (

Bays 2009, p. 5). By affirming and appreciating basic physiological activities like walking and eating, the film seems to say, moderns can rediscover the sheer joy of simply being alive.

The soundtrack accompanying the final shot highlights the importance of levity for touching this joy. The sole instance of extradiegetic music in

Walker, the song is entitled

A Stream Divides the Land and was performed by Samuel Hui in the 1974 Hui brothers film

Games Gamblers Play (Michael Hui, 1974). It cheekily parodies the popular and identically-named 1966 Winnie Wei ballad by altering the lyrics. Whereas the original was effectively a paean to romantic idealism, Hui’s adaptation humorously notes that one does not live on romance alone (“Even bread costs a few pennies a piece/Don’t expect her to live on air”), and that prudence and practicality are probably better keys to staying in love. The tone of lighthearted grassroots realism in this latter song is exemplary of virtually all the movies made by the Hui brothers (also including Michael, Ricky, and Stanley), easily some of the most beloved comedians in Hong Kong and other transnational Chinese communities from the mid 1970s to the early 1990s. The fact that Tsai specifically dedicated

Walker to them (

Youku 2012) speaks volumes of his sense that a Buddhist vision of life need not be forced, laborious, or even formally religious. Rather, the spontaneity and liveliness inherent to the experience of humor mirrors Dogen’s understanding that enlightenment is nothing more than “a profound one-ness with the event at hand, in total openness to its wonder and perfection as manifesting absolute reality” (

Cook 1983, pp. 24–25).