1. Introduction

In recent years, the Planetary Health movement has gained significant attention and recognition as a response to the interconnected challenges facing our planet. This movement seeks to address the complex and interdependent relationship between human health and the health of the natural environment [

1]. However, as the movement continues to evolve, there is a growing recognition of the need to incorporate diverse perspectives, particularly those from the Global South, in order to foster a truly inclusive and equitable approach [

2]. There has also been a rise in grassroots organizations that aim to attract like-minded people to address this crisis. ACOPPHE is one such organization. ACOPPHE, an acronym that stands for African Community of Planetary Partners for Health and Environment, is a value-centered, multi-disciplinary, Planetary Health solution-oriented grassroots organization based in Kenya. Under ACOPPHE, there are a number of action teams, including the Arts, Culture, and Indigenous Knowledge System (ACIKS) team. The Planetary Health field is in need of solutions from the human sciences and that is what the ACIKS team in ACOPPHE aims to explore.

One key aspect worth exploring within the Planetary Health movement is the development of autoethnographic and arts-based methodologies [

3]. Autoethnography is characterized by its personal and reflexive nature. It allows researchers to integrate their personal experiences into scholarly work, contributing to a more holistic and nuanced understanding of cultural and social phenomena [

4]. These innovative approaches recognize the power of personal narratives and creative expression in understanding and addressing Planetary Health issues. By acknowledging the unique knowledge systems and cultural practices of indigenous communities [

5], ACOPPHE, through its ACIKS team, a Global South-centered initiative, seeks to honor and integrate diverse perspectives into the broader framework of the Planetary Health field.

At its core, this initiative is based on indigenous knowledge systems (IKS), which are defined as the complex, interconnected, and culturally embedded knowledge and practices developed and maintained by indigenous peoples over time [

6]. As the integration of IKS presents a significant challenge for the Planetary Health movement, numerous researchers, including Nicole Redvers [

7] and Heather Castleden [

8], have been dedicated to this area of study. Autoethnography methods have emerged as a crucial tool in the pursuit of this objective, as demonstrated by Haeffner et al. [

9]. The aim is to foster loving relationships between humans and the natural world. It acknowledges that indigenous communities have long-standing relationships with their environments, rooted in a deep understanding of their ecosystems and the need for sustainable practices [

8]. By centering on indigenous knowledge systems, this initiative seeks to challenge dominant narratives and power structures, promoting a more equitable and diverse approach to Planetary Health.

Through autoethnography, individuals and communities are encouraged to critically reflect on their own roles and responsibilities within the context of Planetary Health [

10]. This introspective process allows for a deeper understanding of the complex relationships between human actions, ecosystems, and health outcomes. Arts-based methodologies further enhance this exploration by providing alternative channels for communication and expression [

11]. By integrating art forms such as storytelling, visual arts, music, and dance, diverse voices and perspectives can be amplified, fostering a richer and more inclusive dialogue within Planetary Health [

12].

By centering on the Global South, this initiative recognizes the importance of the local context and the unique challenges faced by communities in different regions of the world. It seeks to empower communities to lead their own efforts in addressing Planetary Health issues, building upon their existing knowledge and practices. Through collaboration and knowledge exchange, this initiative aims to create a more balanced and equitable Planetary Health movement that respects and uplifts the voices and experiences of marginalized communities.

This paper looks at the autoethnographies of three individuals, members of ACIKS/ACOPPHE, bringing together their different perspectives and expertise in order to tackle the less explored challenges within the Planetary Health movement related to the humanities field.

2. Our Collaborative Autoethnography Journey

Here, we use a collaborative autoethnographic and arts-based research approach, using our personal histories/narratives as examples to model it. By doing so, we incorporate traditional indigenous knowledge and practices and foster emotional engagement, creating spaces for critical dialogues. This demonstrates how to enhance inclusivity, diversity, and representation in projects related to Planetary Health.

Collaborative autoethnography harnesses the power of sharing personal experiences, as well as interrogating and analyzing them to find out how they affect our intersectional beings and ultimately Planetary Health [

13]. Arts-based research helps to implement creative ways of collecting these personal accounts of individuals and communities, examining them, and using the results to improve how we engage with the process of merging arts, indigenous knowledge, and science for Planetary Health research [

14]. These spaces may take the form of online spaces or small group meetings engaging in Planetary Health issues. We model this by providing our own personal narratives.

3. Our Personal Histories/Narratives

Movement was always part of my understanding of life. When I studied Philosophy, I thought we might be in a different level of society if we had chosen to follow Heraclitus’ understanding that movement was the principle of life, instead of Parmenides’ static conception. I started studying movement in the art field with a dance called Flamenco. Tapping my foot, cutting the air with my arms, and vibrating castanets with my hands affirmed my expressiveness and my willingness to be powerful and healthy. Symbolically with my movement, I “cut off” all the bad things/energies that were not welcome in my life. After deciding to graduate in the health field as a dietitian, the movement again made total sense within the concept of homeostasis. In my understanding, “disease is equal to stagnated energy”; this intuitive perception was corroborated with the oriental medicine concept developed in Traditional Chinese as well as Ayurvedic Medicine, which understands that to keep our energy flowing/moving is what keeps mind, body, and soul in balance.

For a second time, I went back to study movement but this time within the health field, studying somatic techniques that were able to bring people motor recovery through movement. Occidental medicine drove away from this concept, mechanizing and compartmentalizing our bodies, getting lost in the whole and the connection with cosmic flow being narrowed in the academic cartesian “truth” and ignoring ancient knowledge from traditional healers that the limited scientific methodology couldn’t absorb.

Having ancestors from Bahia made it easy to connect with this wisdom and brought me to be part of this African gathering called ACOPPHE. Today, with our complex challenges within Planetary Health, it is imperative to rescue these practices and to rethink academic methodologies to be able to incorporate this field of knowledge.

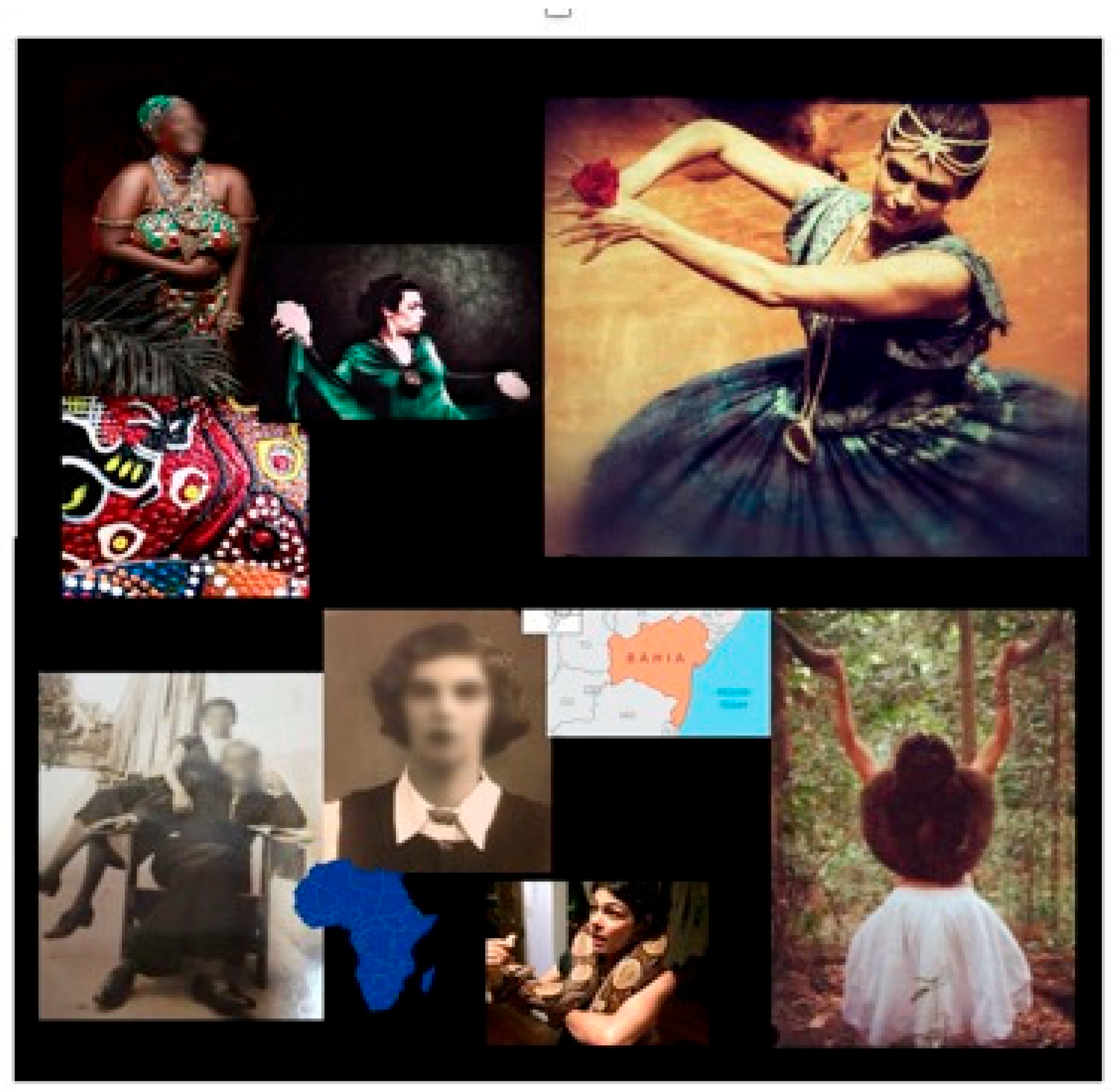

Figure 1 below is a representation of my experiences and background as well as the people who have helped to shape who I am and the paths I chose to follow.

When I was a little girl, my mother traveled with me to different countries for work. As a result, I have lived and settled outside of my home country, Zambia, for most of my life. Despite moving around a lot, my mother understood one thing: I must be taken home to Zambia as often as possible; I must never forget where I come from, the languages of my mothers, the food we eat, and the songs we sing. These trips involved traveling to Lusaka, staying for a while, and then traveling to my mother’s village. I would often fall ill the first few days of arrival in the village. I would often fall ill with a running tummy and vomiting. This would happen without fail every single time we went to the village. Until one day, my mother’s sister told me to follow her into the bushes. When we got in front of a particular bush, she asked me to take a bite of leaves from the bush without touching the bush. She told me to chew the leaves and swallow the juice. Then, she told me to spit the chewed leaves into my hands and rub them over my tummy. That was the end of that session. We made it back to the village, and I had one last turn of my tummy that sent me running for the pit latrine. From that moment onwards till this day, I have never gotten sick when I travel back to the village.

This experience made a great impression on me and remains a vivid memory. It got me questioning and seeking how much indigenous knowledge is buried in the memories of my elders. It has made me an insider–outsider of the Bemba culture. I appreciate the value of this knowledge and try to find ways to revive these practices. As a trained fashion designer, I often find ways to express my culture and find healing through the way I dress, the fabrics used, the accessories, and the colors I am drawn to. As an academic, I got involved in our institution’s mandate to decolonize the curriculum; the knowledge I have gained has offered me a way to make connections and study the intersectionality of marginalized indigenous knowledge, the arts, and the business of health.

Figure 2 below show cases a visual representation of my previously mentioned identities: I am Black, African, Bemba, a woman, academic, fashion, and a fashion designer. I want to emphasize that decolonization carries various meanings and evokes diverse sentiments, some negative and some revolutionary. When I use the term decolonization, I’m referring to breaking down current structural powers that uphold specific knowledge and ways of life. This involves redistributing power and promoting the equal sharing of diverse knowledge and practices globally [

15,

16]. Based on this work, I was invited to engage with an ACOPPHE, and I quickly became a member due to the shared passion to bring marginalized indigenous knowledge to the forefront in solving and healing our African problems and ultimately the planet. ACOPPHE is a space where people with different kinds of knowledge and backgrounds, from medicine to arts, come together to create new and transformative solutions to our health problems. Through my Master’s studies as an artist, I learned about self-study methodologies such as autoethnography, which require that the researcher reflectively and systematically writes about their own relevant experiences of a particular social–cultural phenomenon, providing a unique perspective into a particular culture. It is the sharing of personal experiences that allows us to humanize and broaden the boundaries of inaccessible fields of study, such as medicine, with the inclusion of indigenous knowledge systems and the arts allowing us to rethink the concept of medicine. Is medicine dance, is it drawing, is it storytelling, or is it pills or plants?

Although I have always been environmentally conscious, my first serious engagement with conservation, climate change awareness, and the impact of global warming and its causes was when I met the revolutionary activist Vanessa Black at a meditation retreat. We became instant friends around the year 2003. While I was a Rastafarian pursuing a degree in Sociolinguistics at the University of KwaZulu Natal, she was working at Earthlife and freelancing with Biowatch SA.

Within the Rasta movement, I was involved in the arts, but my engagements with Vanessa and her circle of partners impacted me so much that I began infusing my poetry, events, and other social activities with an active awareness of all our impacts on the environment as you see presented in

Figure 3 below. A few years later, I registered with the Institute for Zero Waste, wherein I learned practical know-how regarding how everything is interconnected with human actions in business/industry education, politics, but most of all food production. I became an interpreter and translator whenever Biowatch or Earthlife or other affiliated organizations went on educational projects within rural and urban communities. My Black consciousness Pan-Afrikanist background made me especially active within the ghetto youth and artistic sectors, and this is how everything I did became interconnected with Planetary Health initiatives. Meeting the ACOPPHE member Tinashe Goronga was a natural progression along the designed path.

For the past 15 years or so, I have also been invited to various interfaith dialogues and conferences to present the Rastafari and traditional spiritual perspective on current affairs. My deep reading of Afrika and its global impact and practical application of the knowledge led me to knowledge of the self or inner knowing, and working with my personal gifts of herbal and elemental healing. In this journey, I have met and co-created learning and healing institutions and campaigns with progressive people within the traditional healing and indigenous knowledge systems sector.

4. Our Collective Outputs so Far as a Team under a Planetary Health Organization

As part of ACOPPHE, we have established a team called Arts Culture and Indigenous Knowledge Systems (ACIKS). Our focus is on exploring the human sciences and arts, and finding ways to use these to connect the natural sciences with people in different communities in a way that is accessible to them. Our aim is to empower marginalized communities to develop their own solutions to issues brought about by Planetary Health problems.

Since we are based in different cities across two continents, our work is conducted online. We experiment with creative ways to raise awareness about Planetary Health issues. For example, we held an event called The Power of Arts and Culture through Food (2022), which showcased indigenous foods from Brazil, South Africa, and Zambia using collages and music from these countries. We also organized an event called June 16: Decolonizing Curricula and the Implications for Planetary Health (2022), to celebrate Youth Day in South Africa. This event aimed at investigating the types of curricula on the African continent that do not address the issues that we face.

As leaders of the team, we have faced challenges since we are all pursuing postgraduate studies while also juggling work and family responsibilities. However, we plan to delve deeper into our ideas as a team and explore how dance, music, and poetry can be used as research methods to share knowledge to address some of the issues related to Planetary Health in 2024.

5. Autoethnography as a Tool to Intersect Community and Scientific Knowledge

Autoethnography, as a tool, can play a crucial role in solidifying the intersection between communities and scientific knowledge. Autoethnography combines the personal experiences and narratives of individuals within a cultural or social context, allowing for a deep exploration of the intersectionality between personal stories, community dynamics, and scientific understanding [

17]. Autoethnography can facilitate this intersection by amplifying community voices, by providing a platform for community members to share their lived experiences, perspectives, and knowledge in their own words. By giving voice to community narratives, autoethnography challenges the dominant scientific discourse, which often overlooks or marginalizes local knowledge and community perspectives such as indigenous knowledge [

18]. It helps to bridge the gap between scientific knowledge and community experiences by highlighting the unique insights and challenges faced by communities in relation to Planetary Health issues, contributing to bidirectionally translationate knowledge. Autoethnography can contextualize scientific knowledge, allowing individuals within communities to contextualize scientific knowledge within their own cultural, social, and environmental environments [

19], providing opportunities to critically examine scientific concepts, theories, and findings in light of community experiences and local realities. By connecting scientific knowledge with lived experiences, autoethnography helps to make scientific concepts more tangible and relevant to communities, fostering a deeper understanding and engagement with scientific information. In addition, autoethnography can help to identify gaps, biases, and limitations within scientific knowledge and research methodologies. By critically reflecting on personal experiences and community narratives, individuals can highlight areas where scientific understanding falls short or fails to capture the complexity and nuances of community dynamics [

9]. This process can lead to a more inclusive and comprehensive scientific approach that takes into account diverse perspectives and challenges existing biases or stereotypes.

Furthermore, autoethnography humanizes scientific research by emphasizing personal stories, emotions, and experiences [

20]. It goes beyond statistical data and abstract theories to capture the lived realities and impacts of Planetary Health issues on individuals and communities. By integrating personal narratives and emotions, autoethnography creates a stronger connection between scientific research and the human element, fostering empathy, understanding, and a sense of shared responsibility, as well as creating loving relationships in addressing Planetary Health challenges [

21]. Equally important is the possibility of the co-creation of knowledge afforded by autoethnography, which is centered on a collaborative approach to knowledge production. It recognizes that communities possess valuable knowledge and expertise that can contribute to scientific understanding. Lastly, actively involving community members in the research process, autoethnography allows for the co-creation of knowledge, where scientific expertise and community knowledge intersect and inform each other. Diversifying scientific methodologies with collaborative approaches could allow multiple perspectives, not only strengthening the scientific knowledge base but also empowering communities as active participants in addressing Planetary Health challenges.

From the above shared personal narratives, we aim to demonstrate the benefits of using autoethnographic or self-study methods. We do this by providing unique perspectives derived from our personal experiences, different backgrounds, and expertise in how we approach Planetary Health.

6. Indigenous Knowledge Systems within Planetary Health Context

Contextualizing indigenous knowledge systems within the framework of Planetary Health is essential in fostering a comprehensive and inclusive approach to addressing the interconnected challenges facing our planet [

22]. Indigenous knowledge systems are holistic and time-tested frameworks that have guided indigenous communities in their interactions with their environments for generations [

23]. These knowledge systems are deeply rooted in cultural traditions, spirituality, and a profound understanding of the natural world.

It is crucial to recognize and respect the diversity and uniqueness of indigenous cultures and their relationships with their ecosystems. Indigenous communities possess a wealth of knowledge about local biodiversity, ecological processes, and sustainable practices that have enabled them to thrive in harmony with nature for centuries [

24].

One key aspect of examining indigenous knowledge systems within Planetary Health is acknowledging the interconnectedness of all living beings. Indigenous cultures often view the environment as a complex web of relationships, where humans are seen as part of, rather than separate from, nature. This holistic perspective emphasizes the interconnectedness of ecological, social, and spiritual dimensions and recognizes the importance of maintaining balance and harmony for the well-being of both people and the environment [

25].

Furthermore, it involves recognizing the unique challenges and experiences faced by indigenous communities. Historical and ongoing colonization, the dispossession of land, and marginalization have disproportionately affected indigenous peoples, leading to detrimental impacts on their health and well-being [

7]. Understanding these social determinants of health is essential in addressing the root causes of disparities and advancing equity within the Planetary Health movement.

In addition, incorporating indigenous knowledge systems within Planetary Health requires engagement in meaningful partnerships and collaborative approaches with indigenous communities. This involves respecting indigenous protocols, engaging in reciprocal relationships, and recognizing indigenous sovereignty and self-determination. By working together with indigenous communities as equal partners, the Planetary Health movement can benefit from the wealth of indigenous knowledge and contribute to the preservation and revitalization of indigenous cultures and practices [

26].

Finally, giving context to indigenous knowledge systems within Planetary Health also involves addressing power dynamics and decolonizing approaches to knowledge production [

27,

28]. It requires challenging Western-centric paradigms and recognizing the validity and relevance of diverse ways of knowing, including oral traditions, storytelling, and experiential learning. By embracing the plurality of knowledge systems and valuing indigenous perspectives, the Planetary Health movement can foster a more inclusive and transformative approach to addressing the complex challenges of our time [

29,

30].

7. Indigenous Knowledge Systems and the Interconnectedness between Art, Spirituality, and Healing Practices (Music, Dance, Chant, Painting Bodies, Rituals)

Indigenous knowledge systems (IKS) encompass a rich body of knowledge, beliefs, practices, and worldviews that have been developed and passed down through generations within indigenous communities worldwide. These knowledge systems are holistic in nature, recognizing the interconnectedness of all things, including art, spirituality, and healing practices [

31].

Art within indigenous cultures often serves as a powerful medium for expression, storytelling, and cultural preservation. Indigenous art forms can include visual arts such as paintings, sculptures, and carvings, as well as performing arts like music, dance, and theater [

32]. Artistic creations often reflect spiritual and cultural beliefs, connecting individuals to their ancestors, land, and the spiritual realm. Through art, indigenous peoples express their identities, histories, and ongoing struggles. Artistic practices can also be deeply healing, providing a means of personal and collective catharsis, resilience, and transformation [

33].

Spirituality is an integral part of indigenous cultures, and it shapes their understanding of the world, their relationships, and their well-being. Indigenous spirituality often emphasizes the interconnectedness and interdependence of all living beings and the environment [

34]. It recognizes the existence of a spiritual dimension that permeates all aspects of life. Spiritual practices vary among indigenous cultures but commonly include rituals, ceremonies, prayer, meditation, and connection to sacred places. These practices foster a sense of balance, harmony, and connection with the larger web of life, promoting healing and well-being at individual, community, and ecological levels.

Healing practices within indigenous communities are deeply rooted in spiritual beliefs and cultural traditions. Indigenous healing approaches recognize that wellness encompasses physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual aspects of being [

35]. Healing is seen as a holistic process that involves restoring balance and harmony within oneself, with others, and with the natural and spiritual worlds [

36]. Indigenous healing practices can include herbal medicine, traditional therapies, energy healing, storytelling, dream work, and guidance from elders and spiritual leaders. These practices not only address physical ailments but also address the underlying spiritual, emotional, and social factors contributing to illness.

The interconnectedness between art, spirituality, and healing practices in indigenous cultures is fundamental. Art provides a means of expressing and reconnecting with spiritual and cultural beliefs, promoting healing and resilience. Spirituality forms the foundation of indigenous worldviews, guiding healing practices and emphasizing the interconnectedness of all things. Healing practices, in turn, draw upon art and spirituality to promote holistic well-being and restore balance at individual and community levels. This interconnectedness fosters a deep sense of belonging, identity, and cultural continuity within indigenous communities [

37].

8. Conclusions

This grassroots initiative has a Global South-centered approach and aims to explore autoethnographic and arts-based methodologies within the Planetary Health movement. This is a significant step towards a more inclusive, equitable, and diverse approach that honors indigenous knowledge systems and fosters loving relationships between humans and the natural world. The initiative seeks to challenge existing power structures and amplify the voices of marginalized communities. Through self-reflection and creative expression, individuals and communities can contribute to a more holistic understanding of Planetary Health. This understanding can help us to work towards sustainable and just solutions that benefit everyone. The intersection between communities and scientific knowledge is crucial in addressing the challenges that our world faces today. Autoethnography and arts-based methods are powerful tools that help to solidify this intersection within the Planetary Health movement. Through autoethnography, community voices are amplified, scientific knowledge is contextualized, research is humanized, gaps and biases are identified, and knowledge is co-created. This approach facilitates a more inclusive, nuanced, and community-centered understanding of Planetary Health issues.

Lastly, it is crucial to understand indigenous knowledge systems within the framework of Planetary Health to promote a comprehensive, inclusive, and equitable approach. By recognizing the holistic nature of indigenous knowledge systems, acknowledging the unique challenges faced by indigenous communities, engaging in meaningful partnerships, and decolonizing approaches to knowledge, the Planetary Health movement can integrate indigenous wisdoms and perspectives, leading to more effective and sustainable solutions for the well-being of both people and the planet.