3.1. Architectural Design

The construction of the past may be described as a process of conceiving an initial Target Past and using it to produce a Constructed Past. These two concepts may be compared to the plans and the actual building in physical architecture. They adapt the distinction in Pierce’s theory of signs between immediate object, a sign as understood at some point in a semiotic process, and dynamic object, the understanding of the sign at the end of that process [

28]. Analogously, the Target Past is the object of a past construction as it is conceived at the outset and evolves during the process. The process of developing a Constructed Past from a Target Past can be a simple or complex affair, ranging from finding a few data items, such as contact information for an individual, to extensive discovery, extraction, interpretation, analysis and synthesis of data and complex argumentation. Extending the analogy to physical architecture, the initial Target Past is like the original blue prints for a building, but progress in construction is likely to lead to changes in the Target Past, comparable to as-built plans for buildings. The Constructed Past is the final product.

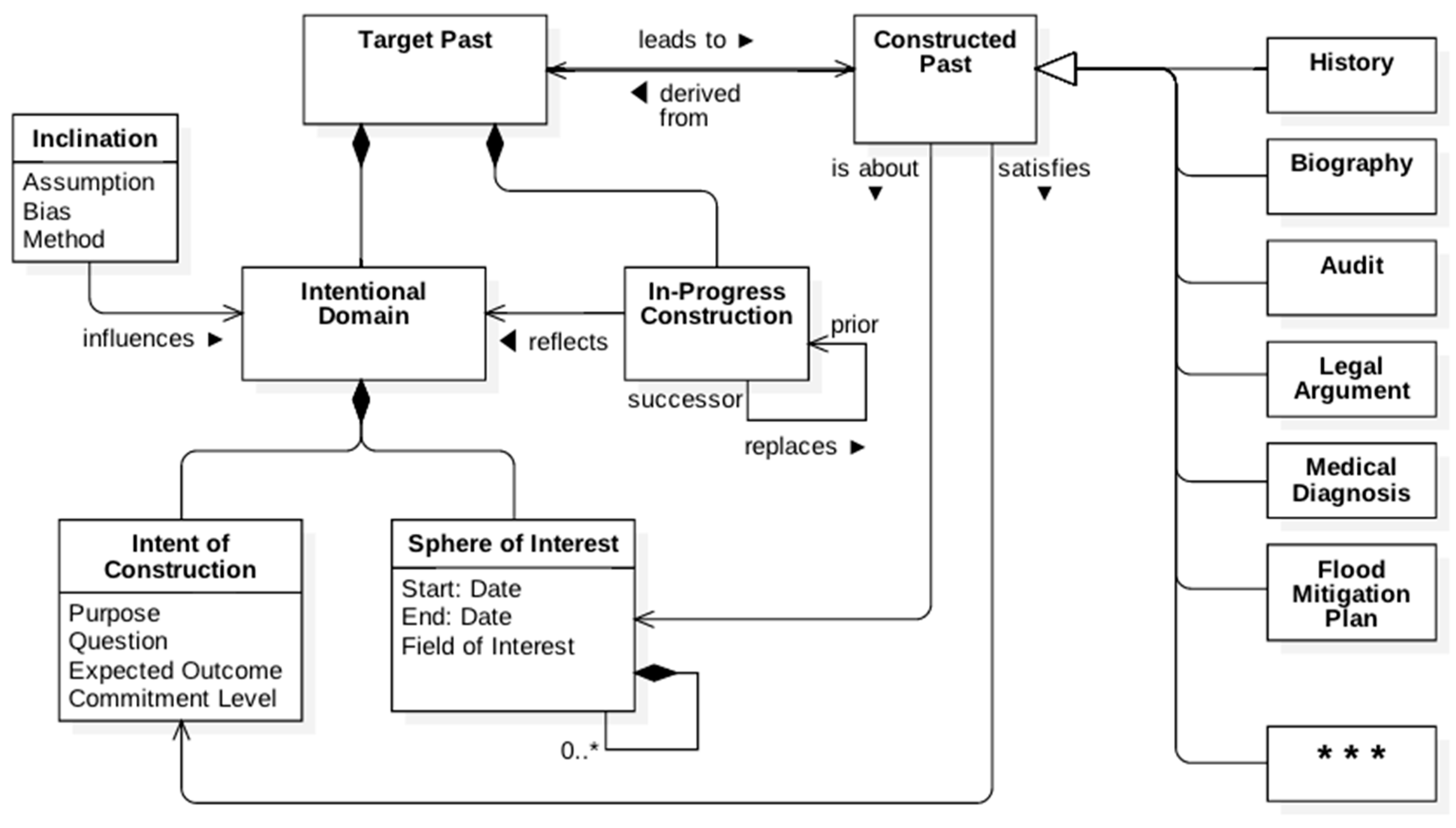

Target Past and Constructed Past are represented as two classes in

Figure 1, Framework for Construction of the Past, a UML class diagram.

Figure 1 shows the fundamental relationship between these two classes: the Target Past leads to the Constructed Past, which is derived from the Target Past.

The Target Past has two components, Intentional Domain and In-Progress Construction. They are shown related to Target Past by composition; that is, if an instance of the Target Past disappeared, so would its components. The Intentional Domain undergirds and guides the construction. Influenced by the Inclination of the party undertaking the construction, including Assumptions about the past, Bias toward the result of construction and preferred Methods of selecting, processing and presenting data about the Target Past, the Intentional Domain is the foundation on which the past is constructed. The In-Progress Construction encapsulates the results during the process.

Intentional Domain comprises the Intent of Construction and Sphere of Interest. Intent of Construction shapes the process and its results, articulating the Purpose for which the construction is undertaken, identifying the Questions that will be addressed, characterizing the Expected Outcome and indicating the Commitment Level, including the amount of time and effort expected to be expended. Intent of Construction can vary widely. The construction of a Target Past can aim to satisfy personal, professional, communal, or organizational interests. It may be motivated by mere curiosity, deep intellectual interest, or practical concerns, such as safety, material gain, competitive advantage, or other reasons. The Expected Outcome can range across a wide spectrum from minor additions or updates to a database to in depth analyses. The expected outcome can change in the process of construction.

Sphere of Interest specifies the time period under investigation and what is of interest. The time frame can range from a point in time, such as when a specific event happened, to a lengthy span, such as tracing the evolution of a major change in society. Everything within the Sphere of Interest must have existed within its start and end date. A subject of interest may not be bounded by those dates; that is, it may exist previously or afterwards, and it might come into existence after the start date or go out of existence before the end date. However, it must exist at some time within the time frame of the Sphere of Interest. A priori, the things that are of interest in the time frame could be anything that existed or occurred within its limits. In practice, however, the Field of Interest will determine what types of things receive attention. Thus, in a study of military tactics of the U.S. Army in the Indian Wars in the Great Plains, weaponry, and in particular, the introduction of the Colt revolver, will be of interest, while the evolution of property rights in relation to cattle ranching in the same area and period will not [

29,

30].

At the start of the process, the Sphere of Interest could be explicitly articulated or tacitly assumed. It may be based on extensive awareness of things in the time frame or chosen out of curiosity about something previously unknown. The Field of Interest could be a broad area such as geography, politics, economics, culture, a scientific discipline, social norms, or some combination of these. However, it could also be highly focused, addressing only a single person or event. A Sphere of Interest may contain lower-level Spheres of Interest. Obvious examples are comparative studies, where the same questions are addressed to different, but comparable, empirical domains and multi-disciplinary research, where different types of question are addressed to a single domain. Sphere of Interest is addressed more fully in

Section 3.1.1.

The Intent of Construction and the Sphere of Interest are interdependent. Different intents can produce different specifications for what is nominally the same Sphere of Interest. For example, the historic growth of a forest could be investigated for an environmental analysis, for purposes of wildfire management, or to project timber yields. Each would result in different Target and Constructed Pasts [

31,

32,

33]. Conversely, as the Sphere of Interest is explored, insights gained may lead to modifying the Purpose, causing the Sphere of Interest to be viewed from a different perspective or changing the expectation of what the Constructed Past will be. Things leaned in the process may also lead to modification of the Sphere of Interest, expanding or contracting the time frame or Field of Interest, revealing additional objects or events that should be considered, or reevaluating the importance or relevance of various elements.

At initiation, the Target Past may only reflect a rudimentary notion of what is being investigated. Except in the simplest cases, as the process of construction proceeds, there will be changes in the In-Progress Construction. New elements may be added, others modified or deleted. Thus,

Figure 1 includes a self-referential relationship for In-Progress Construction, with prior versions succeeded by successor ones. The direction of the relationship shown in

Figure 1 is from successor to prior because the successor is derived from and replaces the prior version.

The Constructed Past should satisfy the Intent of Construction and be about the Sphere of Interest. The Constructed Past may be knowledge that is kept only in a person’s memory, but it could take a tangible and persistent form such as a publication or data in a database. Histories and biographies readily come to mind as examples of persistent Constructed Pasts, but many other types are possible. For example, reports of audits share with histories and biographies that they are extensive descriptions of things in the Sphere of Interest; however, while the purpose of constructing histories and biographies is to produce such descriptions, audits are performed for purposes that go beyond description, namely, assessing conformance with laws, regulations, policies, standards, etc. Other forms of Constructed Past do not aim to describe anything in the past so much as to use data about the past to support present or future-oriented purposes. Examples of such products shown in

Figure 1 include Legal Argument, Medical Diagnosis, and Flood Mitigation Plan. The class icon labeled with three stars (“* * *”) is included in

Figure 1 to indicate that there are other possible products.

The class, Constructed Past, is largely outside of the scope of this article, but it is worth noting that the framework for constructing the past, as illustrated in

Figure 1, encompasses the concern of historiography to analyze instances of Constructed Past in light of the Inclinations and Intentional Domains that influenced them.

3.1.1. Sphere of Interest

This section further articulates the Sphere of Interest.

Figure 2, Sphere of Interest, is a UML class diagram showing, as classes, the main things that may be taken into account given the time frame and Field of Interest defined in the Sphere of Interest. There are four such classes: Entity, Event, Process and State of Affairs. An Entity is something that existed. An Event is something that happened or was done. At least one Entity must be involved in every Event, but interest may be limited to an Entity apart from any involvement in an Event. A Process is a set of several related Events. State of Affairs is a configuration of one or more objects which have some characteristic(s) that are invariant during a period of time.

A Sphere of Interest can encompass many things in all four classes, but it must be about at least one thing. If only one, that object must be an Entity. Thus, the other possible elements in a Sphere of Interest have a multiplicity of zero or more. If the Target Past only aims to determine one or more properties of one or more Entities, the Sphere of Interest need not include any Event. If no Event is included, by definition, neither is any Process. A State of Affairs may focus on an Event or Process but, given that every Event must involve at least one Entity, the minimum of one Entity per Sphere of Interest holds in this case. Similarly, a Sphere of Interest that only concerns characteristic(s) of one or more Entities, may not include any State of Affairs.

An Entity may or may not have a duration. Abstract concepts, such as time, justice, viscosity and monarchy, have no inherent temporal attribute, even though the instantiation, expression or understanding of such concepts may vary over time. Physical objects, such as organisms, buildings and electrical signals have durations. However, every Entity, whether conceptual or physical, must have at least one inherent property that is persistent. Persistent inherent properties of an object may be inherited from a class in which it belongs.

In an Event, something changes. What changes is one of the defining properties of an event. It will often be one or more Entities. However, an Event might alter a Process; for example, a power failure can interrupt the execution of a computer program. A second defining characteristic of an Event is the nature of the change. For example, enacting a law is different than applying the law in a judicial decision. Specifying when and where an Event occurred may also be necessary to identify the Event as the same thing may happen to an object multiple times. Every Event has a finite duration bounded by start and end times, at least one of which must be within the time frame of the Sphere of Interest.

Events and Processes, as well as their relationships with Entities, are further explored in

Section 3.1.2. State of Affairs is addressed in more detail in

Section 3.1.3.

3.1.2. Event, Process and Action

This section provides more details on the relationship between Event and Process and introduces a special type of Event, Action. Every Event involves at least one Entity.

Figure 3, Entity Involvement in Event, illustrates the relationship between these two classes. The way an Entity is involved in an Event is specified in the class, Involvement. Involvement is an association class; that is, a class each instance of which associates single instances of two other classes. Involvement has subclasses; that is, there are different ways an Entity can be involved in an Event. Four common ways are shown in

Figure 3. An Entity may have more than one Involvement in an Event, but an Involvement is specific to a single Event. If the Event did not happen, there could be no Involvement. Further, if the Event did not happen, no Entity would have any Involvement in it. Similarly, if the Entity did not exist, it could not have an Involvement in any Event.

The four subclasses of Involvement depicted in

Figure 3 are Participant, Observer, Altered and Instrument. An Entity as a Participant has an Active Role in an Event, such as initiating, terminating, guiding or performing it. An Observer produces some Observation, which may or may not be persistent in the form in which it is originally made. An Observer might also have a Reaction to an Event and the Reaction could be recorded in a persistent form. An Entity that is altered in an Event has some Impact that changes the Entity. An Impact is a direct consequence of the Event entailed by the nature of the change it involves. The Impact might be intentional; for example, when an environmental sensor transmits data it was designed to register. However, an Impact might be unintentional, such as civilian casualties in battle. An Instrument contributes to the initiation or completion of the Event. It might also be altered by the Event but that would be in the Altered role.

Figure 4, Event and Process, elucidates the relationship between Event and Process. An Event may occur without being part of a Process and, even if it is part of one, an Event may not be dependent on the completion of the Process. Hence, the relationship between Event and Process is one of aggregation, not composition and an Event might not be included in any Process. An extended Process may include one or more subprocesses.

A Process includes at least two Events as Steps, but may include many more. The subclass, Step, is defined as an Event which is part of a Process. Hence, a Step is dependent for its existence on Process and would cease to exist as a Step if the Process did not occur. Its relationship to Process is thus one of composition. Given that there must be several Steps in a Process, two Steps may be related as prior and subsequent. Steps may also be parallel to one another, but

Figure 3 does not include this detail. The subclass will have at least one attribute not found in the superclass: Order or position in the Process.

A Process may follow a Process Pattern, which could be explicitly defined and imposed, for example, by regulation or corporate policy, or observed to occur habitually or regularly. The relationship is defined as “follows” rather than “adheres to” because an instance of a Process may conform by and large to a Process Pattern, but deviate from it in some respect. A complex Process could include subprocesses that may not follow a corresponding Process Pattern. The patterns that are followed by subprocesses in a Process may be subprocess patterns in an overarching Process Pattern, but subprocesses could also follow different, and even independent, Process Patterns. Hence, the relationship of Process Pattern to Process is zero or more.

A Process Pattern must include at least two Pattern Steps and there is a one-to-one correspondence between a Step and a Process Step which it follows. However, there may be Steps in a Process that do not strictly follow a Process Pattern. Even when a Process adheres to a Process Pattern, there may be Steps besides those in the Process Pattern. Hence, there may be zero or one Pattern Step for each Step in a Process.

Figure 5, Human Action, introduces a subclass of Event, Action, in which humans have an Active Role. Other subclasses of Event not addressed in this paper could be added to the model. Action is an Event in which at least one Human Agent is actively involved. Human Agent is a subclass of Participant. In addition to the Active Role that all Participants have, Human Agents characteristically participate in Events in a manner which furthers a particular Aim.

Five subclasses of Human Agent are distinguished: Individual Person, Member Person, Group of People, Organization or Purposed Device. An Individual Person is a biological human. A Group of People and Organizations include several individuals. The difference between a Group of People and an Organization is that a Group of People is defined by the Individual Persons who constitute the group and share a common purpose or interest, while an Organization has a structure and norms, and often a legal status, that transcends the set of Individual Persons who belong to it both at any given time and over time. Member Person is an association class that relates an Individual Person to either a Group of People or an Organization. Member Person acts in a role or capacity defined by a Group of People or Organization to which the individual belongs. These four subclasses are obvious types of Human Agent in the ordinary sense of that term, but Purposed Device is not intuitively a subclass of Human Agent. In CPT, a device qualifies as a Human Agent when it is put into place by an Individual Person, Member Person, Group of People or Organization to effect some purpose. Examples of Purposed Devices include computer applications, surveillance cameras, and traffic signals. An Action may involve no other Human Agent than a Purposed Device. For example, a fire may set off fire alarms that have the Active Role of warning and the Aim of helping people to avoid injury and minimize damage. Nevertheless, Purposed Device is an association class that relates a device to one of the other subclasses of Human Agent. Hence, Purposed Device is modeled with the attribute, Sponsor in

Figure 5.

The subclasses of Human Agent are also subclasses of Entity. Instances of any of them may be objects in a Sphere of Interest without being involved in an Event as a Human Agent. For example, an Individual Person could be affected by an Event; a Group of People could observe an Event; an Organization could be formed by an Event; or a Purposed Device might be reverse engineered in an Event. Human Agents might also have instrumental, rather than intentional Involvement, in Events. For example, human decisions in planning and actions in building a dam might be critical in its eventual collapse [

34].

Just as a Process is a set of related Events, an Activity is a set of related Actions. The relationship between Human Agent and Action and between Action and Activity parallel those relating Participant, Event and Process. The details about Event and Process shown in

Figure 4 are inherited by their subclasses, Action and Activity, respectively, as shown in

Figure 5.

3.1.3. State of Affairs

The class, State of Affairs was introduced in

Section 3.1.1 as one of the principal components of the Sphere of Interest. A State of Affairs is defined by a set of one or more assertions, all of which are true for the same chronological period and concern the same or related objects that are either instances of the Entity, Event or Relationship or their subclasses. Each assertion in the set is about either a single instance, or a single property of such an instance, or a single Relationship. When a Relationship characterizes a State of Affairs, the state includes the two related objects. The related instances may be of the same or different classes. If any of the defining assertions ceases to be true, the State of Affairs terminates. A Target Past could include several State of Affairs determined by different time spans, different sets of objects or different properties.

An assertion may be existential, qualitative or quantitative. It may stipulate whether an object existed or not for the duration of the State of Affairs. Alternatively, the State of Affairs might be determined based on whether an Event or Process endured throughout or did not occur at all during that time. For example, a period of peace is a time when there are no armed hostilities between two parties. An assertion about a State of Affairs may specify a qualitative or quantitative value of a property. The value need not be static; that is, the value might be a constant rate of change or even a constant acceleration. Moreover, the value may be the result of a Boolean expression of arbitrary complexity. Multiple assertions may be combined in a single complex expression.

The value specified in an assertion must be invariant throughout the State of Affairs; however, the property of which the value is specified must itself be variable because, if a property is invariant, the object is stateless with respect to that property.

The following statement exemplifies a State of Affairs: Barbara McClintock pursued graduate studies in cytology and genetics at Cornell University from 1923 to 1927. The statement asserts the persistence of a Relationship, student, between an instance, Dr. McClintock, of the class, Member Person, to an Organization, Cornell University, during a four-year period and specifies a qualitative property of the Relationship; namely, that it concerned cytology and genetics.

A second case illustrates a complex State of Affairs described in a single, complex expression: During Algeria’s war of independence (1954–1962), successive governments in the French Fourth Republic insisted it was a purely internal affair, not an international one. The assertion fixes the time frame of the State of Affairs, associating it with a Process, the Algerian War of Independence, and makes it dependent on a qualitative condition; namely, assertions by French governments about the scope of the process. The condition is a Boolean assertion and would fail if it were shown that any government in the Fourth Republic held a different position during the war.

In the first instance given above, if the Purpose were to determine the role McClintock’s graduate studies had on her eventual winning of the Nobel Prize, the Sphere of Interest might include things like the frequency of women in various roles (student, graduate assistant, professor) in science education in that time frame, the experience and careers of other women with similar education and careers and even broader subjects such as the state of the science during McClintock’s student and professional years [

35].

Similarly, if in the second case cited the Purpose were to discover whether the public statements of the Fourth Republic were consistent with its internal actions or dynamics, the Sphere of Interest would be expanded considerably, including exploring the impact of tactics used by the Algerian rebels and examining the relations of France with other nations, especially the United States, and exploring the perceived self-interests and objectives of those nations [

36,

37].

The definition of a State of Affairs entails the inclusion of certain Entities, Events, Processes and Relationships in the Sphere of Interest; however, the Intent of Construction would be determinative of scope. If the Purpose of construction were to decide the truth or falsity of the assertions in the State of Affairs, the primary objects of interest would be the Entities, Events, Processes and relationships that are the subjects of these assertions. This would also be the case if the Purpose were to develop more detailed data about the State of Affairs. However, if the Purpose were to elucidate the impact of the State of Affairs, the contents of the Sphere of Interest could be expanded or reduced. If, for example, the Target Past focused on how McClintock earned the Nobel Prize, her graduate years might be of minor interest [

38]. A State of Affairs could extend beyond the time frame of the Sphere of Interest. Alternatively, a State of Affairs might start or end within the time frame of the Sphere of Interest.

A State of Affairs, depicted in

Figure 6, depends on the existence of one or more Persistent Properties or one or more Persistent Relationships or some combination of both. In any case, persistence means that a property or relationship has a Start Date and an End Date that defines a period of time which is at least partly within the time frame of the Sphere of Interest. If any Persistent Property or Persistent Relationship that characterizes a State of Affairs changed or went out of existence, the State of Affairs would end. Thus, the duration of a State of Affairs is the shortest intersection of the duration of a Persistent Property or Relationship with the time frame of the State of Affairs.

A Persistent Property is an attribute or behavior of an instance of a Defining Class, which must be a class of Entity or Event that is part of the Target Past. An instance of Persistent Property identifies the Defining Class and the instance of that class that has the Persistent Property indicates what type of property and its name, and specifies the value of that property during the duration of the State of Affairs. The relationship between Persistent Property and Defining Class is one of composition because if Property Value changed or the identified instance of the Defining Class disappeared, so would the Persistent Property and thus the State of Affairs would be terminated.

In the McClintock example, as described above, a new class, University, would be needed and Student should be added as a subclass of Relationship and associated with both Individual Person and University. Student would need two persistent attributes in this State of Affairs. One, which might be named Student Status, would have enumerated values of undergraduate, masters and doctoral. The specifications for the State of Affairs would be satisfied if the actual value of the Barbara McClintock instance were either masters or doctoral. The other attribute could be named Area of Study, with possible values including all the major and minor fields offered by the Cornell College of Agriculture where she was enrolled. The actual values in her case would be cytology and genetics. In practice, the domain model would need to be refined further to suit the case, including adding more specific classes of Entities such as University, School, Department, Scientific Discipline, etc., and more specific classes of Processes and Process Patterns for masters and doctoral studies.

To illustrate the need for additional specification of the model, consider the State of Affairs of the Fourth Republic. Central to this state is the relationship between successive governments and statements about the relationship of France to Algeria. The governments fall within the scope of Organizations as Human Agents. Statements accessible for construction of the Target Past are documents. To address the empirical situation, subclasses of Human Agents need to be added to represent not only government, but also government agencies and officials. Document must be defined as a subclass of Entity and a variety of subclasses of Document are needed. These examples only begin to illustrate the extensions that would be required to apply the model to this case.

The discussion of the McClintock and Fourth Republic cases should not be taken as indicating that the construction of instances of Target Past need to articulate a detailed model of a State of Affairs and populate it with related data. Rather, it is intended primarily to demonstrate that concepts in the CPT model are applicable empirically. The variety of possible constructions of the past is sufficient that there are undoubtedly some situations where articulating a more detailed formal model and organizing data within its structure would be advantageous. In other situations, the model might be applied heuristically to identify the objects and relationships that should be considered in pursuing a Target Past without being substantially elaborated.

3.2. Construction Materials

The concepts set out in the last section characterize the motivation, approach, scope and contents of past constructions. This section explores and describes the things that may be used in the construction of the past, as it were, its Construction Materials. Construction Material is a class whose instances contain or convey data useful in constructing a Target Past.

Figure 7, Construction Materials in Context, is a class diagram that indicates the relationship of Construction Material to the framework of construction. Construction Material must relate to the Sphere of Interest either by providing context or data related to one or more Entities or Events within the sphere. To some degree, an instance of Construction Material should satisfy the Intent of Construction, such as by contributing to answering one or more questions, contributing to the content or structure of the Expected Outcome or satisfying the Purpose of the construction. It is likely to be used at some stage in an In-Progress Construction, although it may subsequently be eliminated. The most valuable Construction Materials are those that contribute to the Constructed Past, even if not explicitly referenced therein.

Thus, the selection and use of Construction Material is critical in producing the Constructed Past. Selection in this context means the determination that an item will be exploited in construction by extracting data from it; accepting assertions it makes, analyzing its contents, etc. The first criterion of selection is that the item relates to the Sphere of Interest. The item should also be perceived as serving the Intent of Construction. Evaluation according to both criteria may be weighted according to how well it seems to serve the intent; to what extent it is congruent with the Sphere of Interest; how well it relates to key objects or events in the Sphere of Interest; and its potential for yielding new or improved data or understanding.

Initial selection may be heavily influenced by the Intent of Construction. Someone who wants to quickly gain familiarity with, or some depth of understanding of a Target Past would likely choose expert sources, such as audit reports, scholarly publications or encyclopedia entries. In contrast, someone who wants to develop original insights would prefer writings by Individual Persons within the Sphere of Interest. Selection could change by both additions and deletions as knowledge is gained in the process.

Construction Materials are either Vestiges or Reflections, as indicated in

Figure 8, Construction Materials. A Vestige is an object that existed within and survives from the time frame of the Sphere of Interest. A Reflection is an information object produced in the course of construction. A Reflection typically expresses a cognitive reaction to one or more Vestiges or earlier Reflections. A Reflection might reflect an existing Constructed Past deemed relevant to the Intentional Domain.

Both Vestige and Reflection have subclasses. The subclasses of Vestige are Item Vestige and Composite Vestige. An Item Vestige may be anything that satisfies the definition of Vestige. An Item Vestige may or may not be part of a Composite Vestige. Hence,

Figure 8 showed Item Vestige as part of zero or more Composite Vestiges. A Composite Vestige is an aggregate of Item Vestiges that existed within the time frame of the Sphere of Interest.

Figure 8 does not show it, but a Composite Vestige may be either ordered or unordered. The order, if any, must have existed within the time frame of the Sphere of Interest. It is possible that both the membership and the relationships within a Composite Vestige varied during that time frame. A Vestige Item may be discovered in isolation and subsequently associated with a Composite Vestige. Likewise, the ordering within a Composite Vestige might be determined progressively during the process of construction. However, all assertions about both the membership and relationships in a Composite Vestige must be based on evidence that is itself vestigial and sufficient to justify an estimate of a high probability that the composite existed within the specified time.

There are many possible types of Composite Vestige.

Figure 8 shows four subclasses: Archaeological Remains, Archival Capital, Serial Publications and Social Media Platform. These four relate to a broad scope of time and illustrate different types of contemporaneous relationships. Social Media Platforms are recent phenomena. All items in a platform date from a brief period of time. Relationships on a platform are created ad hoc by users based on interests in given topics or themes [

39]. Although the earliest serial record keeping dates back millennia [

40], Serial Publications are a phenomenon of the modern era, even though they have existed for centuries longer than social media [

41] (pp. 460–462). The Relationships of instances of Serial Publications are determined top-down according to a priori criteria [

42].

Archival Capital is an adaptation of one of the principal concepts of archival science, that of the archival fonds. This concept was first developed in France and defined as “Un fonds d’archives est en effect l’ensemble des pièces de toute nature que tout corps administratif, toute personne physique or morale, a automatiquement et organiquement réuni en raison même de ses fonctions or d son activité” [

43] (pp. 22–23). This may be rendered in English as the totality of information items of any type whatever that any administrative body or any physical or legal person automatically and organically assembled as a direct consequence of its functions or activities. The unfortunate translation of ‘fonds d’archives’ into ‘archival fonds’ loses the connotation it has in French of something of value, in this case, an ensemble of information assets. ‘Archival assets’ restores this connotation and has the additional benefit of avoiding the reduction that often occurs in practice of an archival fonds to the information assets managed in a formal record keeping regime. Frequently, and especially in the digital realm, even extensive sets of information assets are not subject to records management. This discussion leads to the recognition that there can be at least two types of Relationships within Archival Assets: those that result directly from the performance of functions and activities and those imposed in accordance with a filing system. The former are the relationships described in the concept of the archival bond [

44].

A basic question, which will be addressed further in

Section 4, is: what is an item in Archival Assets. The obvious answer that would be given by archivists and records managers is that it is a record. A record is “A document made or received in the course of a practical activity as an instrument or a by-product of such activity, and set aside for action or reference” [

45]. Unfortunately, in practice, record is often treated as equivalent to document, ignoring that, by definition, a record is a document within a specific context. Instead of ‘record’, CPT adopts the German term of ‘Archivalieneinheit’; that is, an Archival Unit, which is defined as a unit within a fonds [

46]. This construct is both consistent with the concept of fonds d’archives and does not entail that an item in an instance of Archival Assets has been categorized or set aside as a record.

The basic composite in Archaeological Remains is an aggregate of archaeological materials that were all found in the same site and are related chronologically. Archaeological materials include artifacts, ecofacts, structures, and features associated with human activity [

47]. Archaeological research can be described as a multi-layered construction of a Target Past. First, field work involves constructing a past that relates the items found in a site to one another, in effect taking the individual items discovered and defining them as members of a Contemporaneous Composite. This composite has two dimensions: the matrix which characterizes the site as a whole, and the provenience which specifies the position of an item within the matrix. The initial process also entails inferring the time frame of the composite from properties of the items in it. A second phase relates this composite to other Archeological Remains. In archaeological terms, this type of Constructed Past is characterized as an association of the Archeological Remains at different sites. The next phase involves analyzing how people affected the Archaeological Remains at a site. This enables constructing a past that infers things about the material culture, way of life, activities and even belief systems of the people who left the Archaeological Remains behind [

48].

The subclasses of Reflection identified in

Figure 8 are arranged from left to right roughly according to their relation to other instances of Construction Material. An Annotation is a Reflection that is specifically linked, physically or conceptually, to one such instance. The related material may be either a Vestige or another Reflection. A Note is data about some aspect of the Intentional Domain created during the process of construction. Like an Annotation, a Note might be about another instance of Construction Material but is not tightly bound to it and it might be about several other instances. Furthermore, a Note might have a more general scope or be related to the process of construction rather than its contents. A Data Structure is a conceptual schema that defines categories of data within the Intentional Domain, as well as relationships between categories and among data objects. A Data Structure is used to organize Construction Materials or data extracted from them. A Data Structure is likely to reflect the Purpose, Expected Outcome and Questions identified in the Intent of Construction. As indicated by its name, Analysis is something that is produced by analyzing data collected or created in the course of construction. Similarly, Synthesis brings together data from different sources. While the Data Structure provides a way of assembling data, a Synthesis is an object produced by combining multiple pieces of data into a coherent whole. Its scope may extend to the entire Sphere of Interest, but it might be limited to only part of it. A Synthesis may be organized in a way that is parallel to the Data Structure, but it might also be shaped by one or more Questions in the Intent of Construction, including issues that arise in the course of construction. Additional subclasses of Reflection not identified in

Figure 8 may be added to the model. Data Structure, Analysis, and Synthesis might be used to qualify an item as vestigial or as the basis for asserting the existence, membership and structure of a Composite Vestige. They might also be used to define composites that are artifacts of the construction, rather than vestigial.