1. Introduction

Public administrations are large data producers and collectors due to the need to provide support for their internal processes, as well as for services offered to citizens. These data are traditionally available in several formats, according to their own information models, and are managed in different, sometimes isolated, data sources. From the point of view of the organization, the importance of data is undeniable. A proper organizational data management improves decision-making, operational efficiency and service provision. From the side of citizens, the public administration’s data are an essential asset that must be made available in order to enhance transparency and the accountability [

1]. From the point of view of re-users, having these data available enables developing value-added services and applications, consequently stimulating innovation and economy [

2]. Having all these benefits in mind, public administrations are increasingly publishing their data as Open Data, defined as data that can be freely used, re-used and redistributed by anyone—subject only, at most, to the requirement to attribute and sharealike [

3]. An Open Government Data strategy ensures that data are made available across city departments and to third parties, contributes to citizen engagement, increases democracy and serves to drive economic growth and social improvement [

4,

5].

However, these data are mostly represented with information models defined without previous agreements or consensus processes with other institutions, which hinders the possibility of using and sharing them within the same organization or with third parties. This lack of adoption of shared models is one of the major causes of inefficiency of information management within large organizations [

6]. In this regard, ontologies, defined as formal specifications of shared conceptualizations [

7], have been used to describe data without ambiguities. Hence, these may be good artifacts to facilitate reusability, interoperability and data quality assurance.

When all these data are organized according to ontologies (also known as vocabularies in the context of Open Government Data) and represented in some graph-like format, we can talk about a Knowledge Graph. Despite there being no consensus about a single definition for a Knowledge Graph [

8,

9,

10,

11], in this work it is understood as a graph of data with the intent to compose knowledge [

12]. Knowledge Graphs have become a powerful resource in big industries, for example, Google’s Knowledge Graph, Facebook’s Search Engine, and Microsoft’s Satori, among others, use Knowledge Graphs for their business purposes [

10,

13]. Likewise, an increasing amount of public administrations are creating and maintaining Knowledge Graphs as a way to capture, represent, publish and exploit their data. In this respect, several works about Knowledge Graphs for public administration data management have been reported in the literature [

14,

15,

16,

17].

Managing a Knowledge Graph in any organization (e.g., a public administration) represents an advantage because it allows sharing and reusing common parts of knowledge across the organization. This internal reuse promotes that the main re-user will be the own public administration and as a result an open-data-by-default management. In addition, a knowledge graph is a valuable source for scientific studies, economic development, active involvement of citizens, etc.

Having all of these aspects in mind, the Zaragoza city council has been working for more than 15 years on releasing its public data as Open Data. The city council has released its data in structured and open formats, described by agreed vocabularies (when possible) and available from several tools. In addition, the city council efforts to implement this approach have resulted in the development of a well-defined data management process that eases and boosts an open-data-by-default policy. One of the main assets of this policy is the Zaragoza’s Knowledge Graph, which clusters all these data in order to exploit the knowledge of the city.

In this paper, we describe the work performed to generate the Zaragoza’s Knowledge Graph. The remainder of this manuscript is structured as follows: In

Section 2 several public administration initiatives for Open Data publishing are introduced. In

Section 3 a brief history of the Zaragoza’s Knowledge Graph is presented. Then, the technological approach for Knowledge Graph generation and maintenance is shown in

Section 4 and an overview of the Knowledge Graph is provided in

Section 5. Finally, conclusions about this work and foreseen future work are listed in

Section 6.

3. History of Zaragoza’s Knowledge Graph

Since 2003, the Zaragoza city council has been developing an ambitious project in order to become a national and international reference in technological change and innovation. With this goal in mind, the city council launched several actions with the main focus on the use of new information and communication technologies to provide more efficient public services and guarantee all citizens, entities, companies and institutions the exercise of their full rights to information access.

In 2004,

IDEZar (Spatial Data Infrastructure of Zaragoza:

https://www.zaragoza.es/ciudad/idezar) was developed in order to provide several internal and external services publishing its geographical characteristics compliant to international standards like the INSPIRE Directive (

https://inspire.ec.europa.eu) or those provided by the Open Geospatial Consortium (

http://www.opengeospatial.org). Since its first days,

IDEZar was semantically oriented, due to the fact that one of these services was focused on a semantic search engine for public services. It included visualizations, interoperable services, a thematic catalog, etc.

Around those days, the Zaragoza city council’s Open Data policy was implemented in order to comply with the Spanish law about public information reuse [

21]. The aim of this policy is that public data should be: unique, shared, accessible, and reusable by third parties. Thus in 2010, the city council started to publish several services via the

Datos de Zaragoza (Open Data Zaragoza:

http://datosabiertos.zaragoza.es) portal, promoting information reuse by citizens, enterprises, and other organizations in order to increase transparency.

Datos de Zaragoza mainly aggregates the previous developments and experiences of the city council. Thus, having in mind that the Spatial Data Infrastructures (SDI) has been the precursors of data opening, the

IDEZar service represents the core of the current Open Data portal [

22]. Currently, one of the IDEZar key reference services is the

Callejero (

http://idezar.zaragoza.es/callejero), which allows extracting information based on city roads, searches and visualizations.

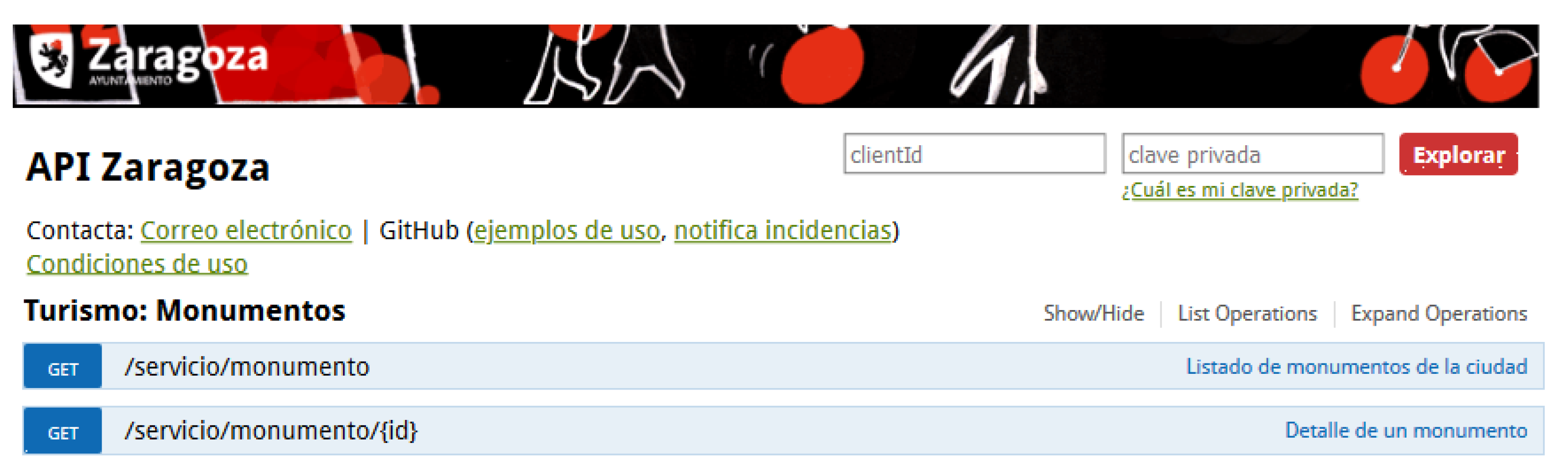

Nowadays, this Open Data policy makes the city operate an open-data-by-default policy for all the public sector information handled by the city council. It has been possible because of the implementation of a data management system for the Zaragoza’s website (

http://www.zaragoza.es/sedeelectronica). This website contains all city council information and services, for instance, the open data portal. The data management system has the following goals: using open-data-by-default, unifying data life cycle management tools and promoting code reuse developed by other administrations. In order to accomplish these goals an API has been implemented as a core piece of this system. The business logic developed for the API becomes the only data access point for read and write operations. Thus, it allows external or internal management tools to be integrated with the API. This approach ensures the sustainability of the Open Data platform, in contrast to other approaches where data publication is performed at the end of the data management life cycle, sometimes creating graveyards.

Following Zaragoza’s approach, a Spanish project named

Ciudades Abiertas (Open Cities:

https://ciudadesabiertas.es) is currently under development. The main objective of this project is generating an interoperable and collaborative platform in order to promote Open Government, which refers to the relationship between citizens and public administrations. On the one hand, citizens will have permanent access to information on administrative processes in order to exercise adequate public control and to become part of government actions. On the other hand, public administrations will manage data in a unique, shared, open-by-default, georeferenced, and semantically annotated manner. This project represents a step forward in order to afford a common representation and generic infrastructure between four pilot Spanish city councils (Zaragoza, Madrid, A Coruña and Santiago de Compostela), to be extended to others in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.C., P.E.-A. and M.J.F.-R.; software, V.M.-P., R.N.-B. and M.J.F.-R.; validation, O.C., M.J.F.-R. and V.M.-P.; investigation, P.E.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, P.E.-A; writing—review and editing, P.E.-A., O.C. and M.J.F.-R.; supervision, O.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by a Predoctoral grant from the I+D+i program of the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid and DATOS 4.0: RETOS Y SOLUCIONES - UPM Spanish national project (TIN2016-78011-C4-4-R).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable contributions of all services and entities of the Zaragoza City Council, Cátedra de Territorio y Visualización de la Universidad de Zaragoza, Grupo de Sistemas de Información Avanzados Universidad de Zaragoza, Miguel Angel García, Freddy Prityana, and Edna Ruckhaus.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| CSV | Comma-separated values |

| FIQL | Feed Item Query Language |

| HTML | Hypertext Markup Language |

| INSPIRE | INfrastructure for SPatial InfoRmation in Europe |

| OWL | Ontology Web Language |

| RDF | Resource Description Framework |

| REST | Representational State Transfer |

| SPARQL | Protocol and RDF Query Language |

| URI | Uniform Resource Identifier |

| W3C | World Wide Web Consortium |

References

- Lourenço, R.P. An analysis of open government portals: A perspective of transparency for accountability. Gov. Inf. Q. 2015, 32, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Charalabidis, Y.; Zuiderwijk, A. Benefits, adoption barriers and myths of open data and open government. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2012, 29, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knowledge, Open. Open Data Handbook. 2012. Available online: https://opendatahandbook.org/guide/en/what-is-open-data (accessed on 2 September 2019).

- Safarov, I.; Meijer, A.; Grimmelikhuijsen, S. Utilization of open government data: A systematic literature review of types, conditions, effects and users. Inf. Polity 2017, 22, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruijer, E.H.; Martinius, E. Researching the democratic impact of open government data: A systematic literature review. Inf. Polity 2017, 22, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villazon-Terrazas, B.; Garcia-Santa, N.; Ren, Y.; Faraotti, A.; Wu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Vetere, G.; Pan, J.Z. Knowledge Graph Foundations. In Exploiting Linked Data and Knowledge Graphs in Large Organisations; Pan, J.Z., Vetere, G., Gomez-Perez, J.M., Wu, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 17–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, R.; Benjamins, V.R.; Fensel, D. Knowledge engineering: Principles and methods. Data Knowl. Eng. 1998, 25, 161–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singhal, A. Introducing the Knowledge Graph: Things, Not Strings. 2012. Available online: https://www.blog.google/products/search/introducing-knowledge-graph-things-not (accessed on 15 September 2019).

- Ehrlinger, L.; Wöß, W. Towards a Definition of Knowledge Graphs. Semantics (Posters Demos SuCCESS) 2016, 48, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Perez, J.M.; Pan, J.Z.; Vetere, G.; Wu, H. Enterprise knowledge graph: An introduction. In Exploiting Linked Data and Knowledge Graphs in Large Organisations; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Paulheim, H. Knowledge graph refinement: A survey of approaches and evaluation methods. Semant. Web 2017, 8, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonatti, P.A.; Decker, S.; Polleres, A.; Presutti, V. Knowledge Graphs: New Directions for Knowledge Representation on the Semantic Web (Dagstuhl Seminar 18371). In Proceedings of the Schloss Dagstuhl-Leibniz-Zentrum fuer Informatik, London, UK, 3–6 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Wang, C.; Cheng, W.; Gao, M.; Zhou, A. A retrospective of knowledge graphs. Front. Comput. Sci. 2018, 12, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradi, A.; Foschini, L.; Ianniello, R. Linked data for open government: The case of Bologna. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), Madeira, Portugal, 23–26 June 2014; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Jaakola, A.; Kekkonen, H.; Lahti, T.; Manninen, A. Open data, open cities: Experiences from the Helsinki Metropolitan Area. Case Helsinki Region Infoshare www. hri. fi. Stat. J. IAOS 2015, 31, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, R.; Awazu, Y. Liberating data for public value: The case of Data. gov. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 668–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simperl, E.; Corcho, O.; Grobelnik, M.; Roman, D.; Soylu, A.; Ruíz, M.J.F.; Gatti, S.; Taggart, C.; Klima, U.S.; Uliana, A.F.; et al. Towards a Knowledge Graph Based Platform for Public Procurement. In Proceedings of the Research Conference on Metadata and Semantics Research, Limassol, Cyprus, 23–26 October 2018; pp. 317–323. [Google Scholar]

- Shadbolt, N.; O’Hara, K.; Berners-Lee, T.; Gibbins, N.; Glaser, H.; Hall, W. Linked open government data: Lessons from data. gov. uk. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2012, 27, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baker, M. Canada’s growing open data movement. Feliciter 2011, 57, 96–98. [Google Scholar]

- Chatfield, A.T.; Reddick, C.G. A longitudinal cross-sector analysis of open data portal service capability: The case of Australian local governments. Gov. Inf. Q. 2017, 34, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ruiz, M.J.; Alonso, J.M.; ALvarez, M.; Morlán-Plo, V.; Perez, M.J.P.; Zarazaga-Soria, F.F.J. La Política de Datos Abiertos del Ayuntamiento de Zaragoza: Datosabiertos. zaragoza. es. In Proceedings of the Actas de CAEPIA, San Cristóbal de la Laguna, Tenerife, Spain, 7–10 November 2011; pp. 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ruiz, M.J.; Zarazaga-Soria, F.J. IDEZar: La Infraestructura de Datos Abiertos Espaciales del Ayuntamiento de Zaragoza (2004-); Servicio de Publicaciones; Universidad de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2017; pp. 10–26. [Google Scholar]

- Denaux, R.; Ren, Y.; Villazon-Terrazas, B.; Alexopoulos, P.; Faraotti, A.; Wu, H. Knowledge Architecture for Organisations. In Exploiting Linked Data and Knowledge Graphs in Large Organisations; Pan, J.Z., Vetere, G., Gomez-Perez, J.M., Wu, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 57–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villazón-Terrazas, B.; Vilches-Blázquez, L.M.; Corcho, O.; Gómez-Pérez, A. Methodological Guidelines for Publishing Government Linked Data. In Linking Government Data; Wood, D., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weibel, S.; Kunze, J.; Lagoze, C.; Wolf, M. Dublin core metadata for resource discovery. Internet Eng. Task Force RFC 1998, 2413, 132. [Google Scholar]

- Guha, R.V.; Brickley, D.; Macbeth, S. Schema. org: Evolution of structured data on the web. Commun. ACM 2016, 59, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Soro, J.F.; Esteban, G.; Corcho, O.; Serón, F. PPROC, an ontology for transparency in public procurement. Semant. Web 2016, 7, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berrueta, D.; Phipps, J.; Miles, A.; Baker, T.; Swick, R. Best Practice Recipes for Publishing RDF Vocabularies. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/swbp-vocab-pub (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- Spain, M.o.F.P.A. Technical Interoperability Standard for the Reuse of Information Resources. 2013. Available online: https://administracionelectronica.gob.es/pae_Home/dam/jcr:a8d2c143-ce9a-4fc7-afe7-ef5d9ba7c4a1/ENGLISH_Interoperability_Agreement_for%20the%20Reuse%20of%20Information%20Resources.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- Soylu, A.; Elvesæter, B.; Turk, P.; Roman, D.; Corcho, O.; Simperl, E.; Konstantinidis, G.; Lech, T.C. Towards an Ontology for Public Procurement based on the Open Contracting Data Standard. In Proceedings of the Conference on e-Business, e-Services and e-Society, Trondheim, Norway, 18–20 September 2019; pp. 230–237. [Google Scholar]

- Zaveri, A.; Rula, A.; Maurino, A.; Pietrobon, R.; Lehmann, J.; Auer, S. Quality assessment for linked data: A survey. Semant. Web 2016, 7, 63–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).