Abstract

The use of information age technology favors pervasive communication exchanges and complex phenomenologies, which affect the production of knowledge and the permanent transformation of personalities and contexts, not always with a view to prosocial empowerment of differences. From the analysis of the liquid socio–psycho–educational frames explored in the research activated at the University of Salerno, the permanent need for a widespread media education emerges, to be rooted in a lifelong learning vision to achieve systemic inclusiveness. This is the basis of the epistemology of the existential design model Flipped Inclusion, promoted and tested at the University of Salerno, whose complex idiomatic phrase constitutes the integrated and complex synthesis of the multi-perspective and multimodal approach pursued by the model. In the exploratory–descriptive–transformative research underway since 2014, through blended learning, complex blended learning and with formal, non-formal and informal contexts, the design–organizational, algorithmic–computational architecture of flipped inclusion is experimented upon. The trend of data since 2014 confirms the educational value of the model, due to the positive impact relating to inclusiveness on personal styles and social contexts, hence the intention to continue research on larger samples.

Keywords:

learning; education; transformation; inclusion; system; management; organization; social capital; Microsoft Teams; ergonomy 1. Introduction

Socio-Contextual Analysis and Integrative Background

The global information society, generated by the advent of the technological era and its media accessibility, has suspended the person in a network of self-constructed meanings. They require continuous interpretation and reworking to be placed by social context, through lifelong learning, as a phenomenological study of the existential evolution of liquid society [1]. All this is linked to the training need for a re-education of human and cultural capital [2] to promote media citizenship [3] and democracy [4] through the activation of cross-media re-co-productive re-co-structural processes of knowledge.

Therefore, the current situational/relational geography that is rooted in the social atomism promoted by the web requires new process management skills, with a view to incessant emancipation and continuous form–action.

The use of information age technology favors pervasive communication exchanges and complex phenomenologies, which affect the production of knowledge and the permanent transformation of personalities and contexts, not always with a view to prosocial empowerment of differences. From the analysis of the liquid socio–psycho–educational frames explored in the research activated at the University of Salerno, the permanent need for a widespread media education emerges, to be rooted in a lifelong learning vision to achieve systemic inclusiveness. This is the basis of the epistemology of the existential design model Flipped Inclusion, promoted and tested at the University of Salerno, whose complex idiomatic phrase constitutes the integrated and complex synthesis of the multi-perspective and multimodal approach pursued by the model. The learning contexts in the knowledge society highlight an incessant exploratory–phenomenological reinterpretation among the new training needs which, in involving socio–cultural practices, uses and habits, requires a cyclical classification in socio–political–economic mobile frames. All this requires the activation of social orientation and re-orientation policies towards the exogenous pressures generated by the economic forces, which have gradually occupied the European political space [5]. This is possible through a training investment in human capital, with training methods focused on the empowerment of integrated systems [6]; an acknowledgment by each social actor of the role and the centrality of each in the definition of context conditions; the individual power of activation, promotion and management of processes in social systems; and with continuous structural change. In this sense, the priority role of the scientific community and field research is confirmed: to monitor all the education of the community of practice [7], aimed at improving the social system structure [8]. In fact, despite the interactive exchanges and fluid comparisons, the incessant transformative symbolic productions that are not always anchored to a value assessment focused on the person–community–society trinomial, continue to produce existential precariousness with continuous, priceless searches for meaning and belonging. We are witnessing multiple forms of accessibility to information and knowledge [9]. The involvement of the (1) personal, (2) political, (3) cultural, (4) socio–economic [10] spheres; the exercise of a new form of cross-literacy, provides multidimensional benefits [11]. It is possible to promote the development (a) of trust, (b) of potentiality, (c) of creativity, (d) of critical thinking, which pertain to the personal sphere.

With regard to the political sphere, the aim is to strengthen the skills of: (a) participation, (b) promotion, (c) reconciliation, (d) sharing. The cultural area, on the other hand, is guaranteed through the actions that (a) preserve identity, (b) recognize differences, (c) promote comparison, (d) reflect on attitudes. For an enhancement of the socio–economic sphere, it is necessary to invest in phases of: (a) prevention, (b) support, (c) guarantee, (d) sustainability [12] of education, equality, opportunity, well-being [13]. The strategic value of educational research on democratic generativity is decisive for decoding information, communication [14] and socio-psycho-cultural processes. It is a question of promoting models of integrated digital citizenship, as new ways of digital literacy, to also focus on the principles of the existing European framework [15] through the activation of "practices and social relations, centered on knowledge, language and culture" [11] (p. 1).

The Flipped Inclusion model experimented upon at the University of Salerno, which strategically uses cross-media tools to support design and systemic inclusiveness, starts from a reflection on the technological-trans-educational environments. It is organized on the flipped classroom, a sub-type of the blended learning approach, which for the resources it incorporates [16], gives an integrated educational enhancement. Investments are made in the educational value of mixed learning systems, which improve self-regulated learning [17], autonomy in research and cooperative relationships [18]. Digital competence, together with the method used and the Blended Learning environments, favor the motivation to learn [16]. The cross-media integration between different sensory–perceptual systems affects the modification of the awareness of a being in the global world [1]; the apparently unlimited and intangible space-temporal dimensions, which involve and condition through diffuse liquidity [1], relationships, cognitions and metacognition, individual and collective. Through teaching media technologies [19], it is possible to program educational interventions that make use of use of mixed cross-media learning environments [20], with data mining applied to asynchronous interactions and blended learning environments [21], which allows application variability [22], with differentiations for: (1) position; (2) means of distribution; (3) type of education; (4) synchrony, which facilitates its functional use in the predictive emergence of latent problems [23]. With the flipped inclusion model, investments are made in active teaching approaches from mixed learning, such as flipped learning, but with a new perspective of the meaning of overturning which extends to social roles and educational contexts, intended as an augmented classroom [22].

Flipped Inclusion through the co-construction of stimulating environments promotes generalization processes [24], through didactic paths of co-responsible prosocial mediation, and forms of multiple multimodal re-literacy [25] located by context, which involve different languages, from the iconic to the visual. “By retracing the epistemological perspectives of complexity that are supported by technologies used as instrumental teas, we intend to propose an overturning of the Aristotelian approach and an adoption of the socio-intersubjective [26] socio-constructive and connectionist poietic philosophy” [27] (p. 33).

Experimental research on the Flipped Inclusion model, in line with the ergonomic–anthropocentric conceptual paradigm, is rooted in the principles of the strategic accessibility of Universal Design [28], such as values and universal rights [29] in terms of inclusive opportunity, and promotes de-construction and re-construction of the person, principle and outcome of any pedagogical reflection [30], in view of a pro-social generative and re-generative transformation of the quality of human relationships, of the connective tissue of the community. “We aim for a qualitative communicative relationship [31], characterized by an emotional-experiential harmony, with a sharing of codes, meanings and objectives” [32] (p. 161).

The flipped inclusion model, with an ergonomic–anthropocentric didactic approach [33], therefore, aims at inclusive, ecological–systemic well-being [34], through computational logic operating procedures, organized in systematic and systemic design architectures, to encourage the acquisition of inclusive prosocial skills.

The model was proposed and experimented upon at the University of Salerno in an exploratory–descriptive–transformative pilot study in 2014, in which the educational value of the design architectures and methodological system were verified, as supporting systemic inclusiveness, through the promotion of prosocial and inclusive personal profiles and inclusive contexts [33].

2. Methods

2.1. Flipped Inclusion: Theoretical–Methodological Architecture and Learning Contexts

The drying up of the concept of human community [35], as shared transcendence and intersubjective communion, typical of the mobile and disoriented post-modern society [36] (p. 6), from the narcissistic cultural and existential drifts [37], is configured as the reflection of postmodern metaphysical individualism. The anthropology of the atomized individual [38], enveloped in logical aporias, acts in the principle of total and divine self-sufficiency. The uncritical adherence to pre-established dogmas translates into the inability to both refute widespread symbolizations, and to produce divergent universes, to the point of inhibiting new transformative solutions and producing acquiescent forms of discernment [39].

The interhuman bond, which takes the form of embodied communicative forms, reductio ad unum, risks both depleting the dialogical value of a foundational alterity and inducing prejudicially nihilistic sense productions [40].

The unveiling of the axiological value of the person, individual substance of a relational nature [41], allows us to glimpse the epicenter of a neo-anthropology of the community, which heals and reconfigures the cultural presuppositions of global capitalism, starting from the dialogic re-humanization between universes values [42]. In this sense, the trajectory of humanist anthropocentrism, tendentially ethical, so-called noble [43] (p.38), promotes an effective renewal “aimed at reconfiguring pedagogical knowledge and educational practices” [30] (p. 73), providing critical–interpretative tools, including technological ones, for a remission of subjectivity, in the context of an ergonomic–inclusive existential design [44] that responds to the cognitive, emotional and social styles of the learners, through methodological criteria capable of “guiding an attitude problematic, questioning and reflective “ [30] (p. 73).

2.2. Experimental Research and Applied Methods

The research was conducted in the three-year period 2014–2017, and studied the potential connections between the media applied in the classroom and beyond the classroom [45], with transformative teaching [46], such as flipped learning, applied in an inclusive way of learning of the system [47]. Multi-method, interpretative–descriptive–transformative research was conducted to examine, discriminate, and highlight conclusions based on empirical evidence.

The research project took into account a review of the literature, which addressed the exploratory investigation, concerning the role of cross-media technologies and the incidents on the socio–political–economic macro-structure and educational psycho-anthropic [48,49].

The exploratory, descriptive-trans-formative study [50,51] on the flipped inclusion model, carried out at the University of Salerno, originates from an analytical reflection on the pervasive post-modern technological trans-formativity. A management model [52] and organization of new teaching challenges is proposed that aims to promote socio–educational policies, organized in simplexity phases [46] of exploration and declination of located phenomenological frames, to design universal design solutions to be experimented upon from a perspective of ecological–systemic inclusiveness and circular [48] re-education [4], which crosses the cross-media computational logic of web 4.0.

We hypothesized that scientificity is a procedural quality of life [47] and we focused on collecting data that can help us answer questions related to aspects of society, to understand it.

The research questions were:

Research Question-guide 1: Does the Flipped inclusion model facilitate your study method and influence learning, cognitive, attribution styles (communicative, relational, cooperative) and promote the formation of individual prosocial, inclusive-plural profiles

Research Question-guide 2: Does flipped inclusion teaching affect the promotion of inclusive contexts?

The research hypotheses verified were:

- (1)

- the teaching–transformative–design model of flipped inclusion promotes pro-social skills and inclusive-plural profiles with

- (2)

- contexts transformed into an inclusive, ecological–systemic perspective.

The flipped inclusion model [53] stands as a democratic, metadisciplinary [54] model of existential planning [4] which invests in a dynamic organization (modular and recursive) of simple teaching, with increasing complexity [46]. It is a matter of promoting structured forms of permanent, co-responsible and self-managed system learning in a network-learning organization[55], with a prosocial vision and inclusive well-being mission-learning society [56], through a Lifelong learning vision (continuous and recursive learning), Lifewide Learning (diffuse-transversal learning process) and Lifedeep Learning (deep empowerment learning). A dynamic, circular, generative and maieutic work organization of relational communion is proposed. Using modular taxonomic [57] and cyclic-recursive paths of cooperative interdependence [58], Flipped Inclusion combines the concept of inclusion in a micro-meso-macro and systemic macro-perspective [34] through top down and bottom project co-actions up [45] to the proactive, transformative non-linear didactic approach of the Flipped Classroom [45].

With the experimental research–action paths, therefore, the effects of the flipped inclusion model were studied; these made use of cross-media tools in the classroom and beyond the class it was experimented through research–action paths, verifying

- (1)

- cognitive and metacognitive, social and prosocial processes;

- (2)

- inclusive learning styles (knowledge and skills), cognitive style and attribution style (communicative and socio-relational);

- (3)

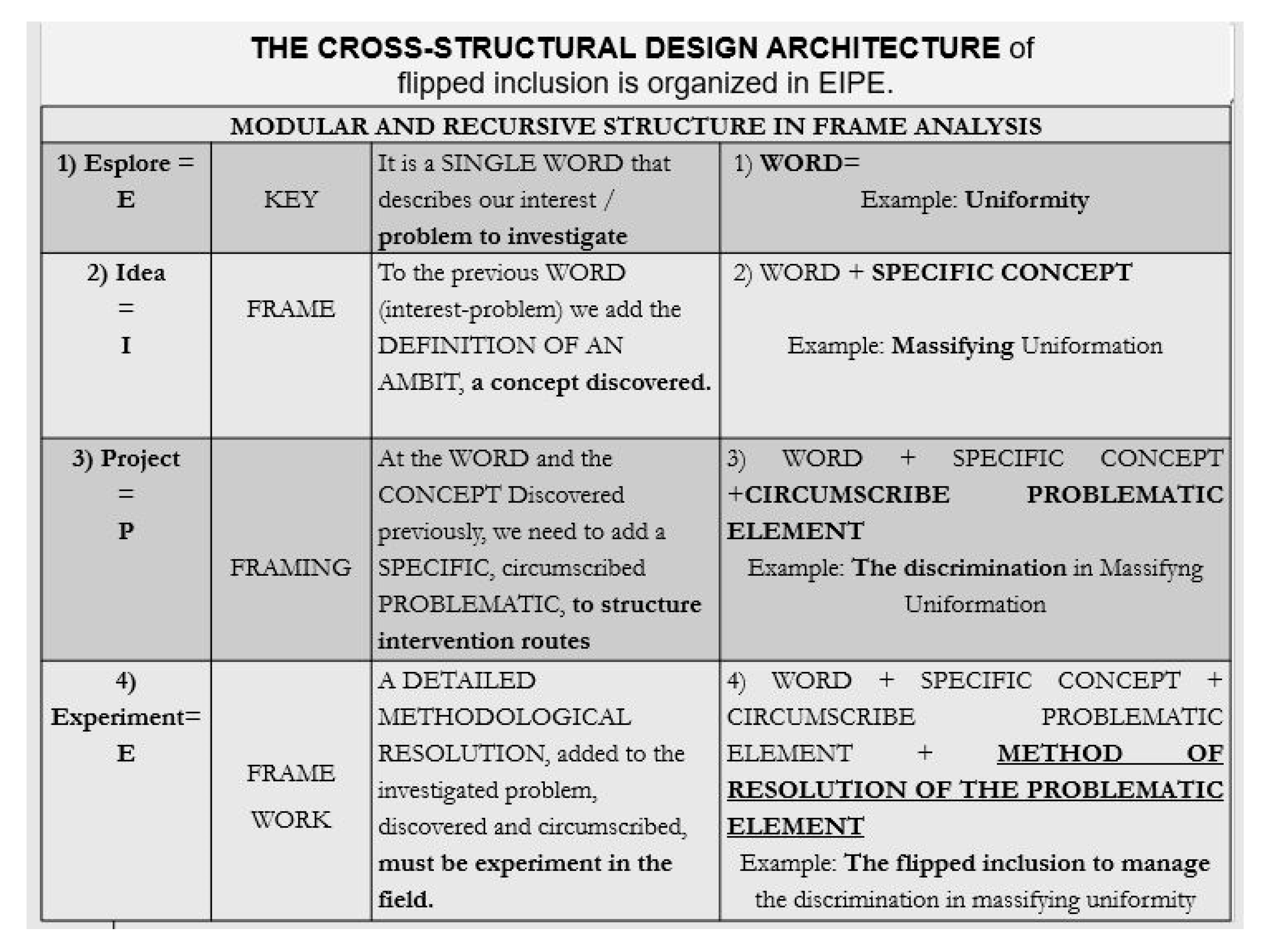

- promotion of inclusive, ecological and systemic prosocial contexts. The design architecture is organized in modular and recursive medium empowerment paths [59], which pursue the cross-media logic of crossing between different approaches, transposed didactically. Frame analysis [60] is applied as a top down approach; while the systemic ecological inclusive perspective [61] is transposed and organized in bottom up mode, with intergroup peer-empowerment-cooperative paths, to educate on the observation of inter-agency between contextual factors, from micro to macro-structural [34], which trace the complexities of the network and the management of the inputs and dynamics that are expressed in the technological habitat. A modular and recursive systematic application of an EIPE (stands for Explore-Idea-Project-Experimet) matrix-process is foreseen, which declined in top down design logic, through a didactic transposition of the frame analysis [60] and in bottom up, taking into account Gee’s learning principles [25]. In particular, the following phases:

- E-Exploring—Problem Finding/Setting/Analysis [62], which is activated by the analysis of a contextual stimulus, and is crossed by the principle and semiotic domain of self-knowledge, for the identification of a stimulus word, through paths of educational inquiry learning [63].

- I-Idea—Creative Thinking [64] is based on the Amplification, Input and Communication Competence Principle, making use of discovery learning [65].

- P-Project—Decision making [66], based on the principles of design and active Control and Meta-level thinking, which contribute to declining the principle of Identity through mastery learning [57].

- E-Experiment—Problem solving [67] is characterized by the application of the Committed Principles and continuous learning, focused on the experiential practice that characterizes the Experimental learning [68].

With the aim of achieving the set objectives [69], each path develops in a systemic perspective, in that “knowledge of a work system is inextricably linked to the study of the interactions between the parts that constitute it” [33] (p. 4).

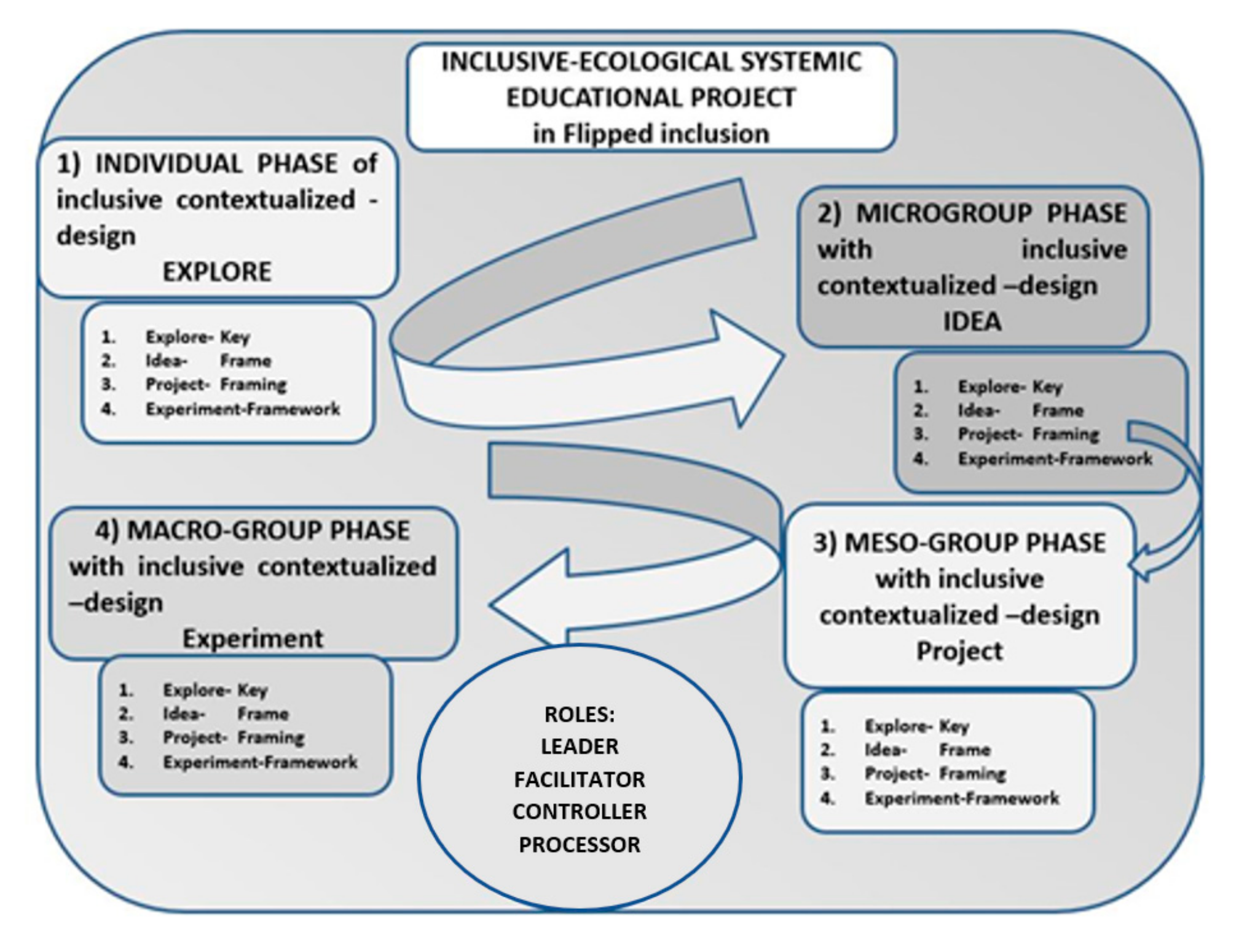

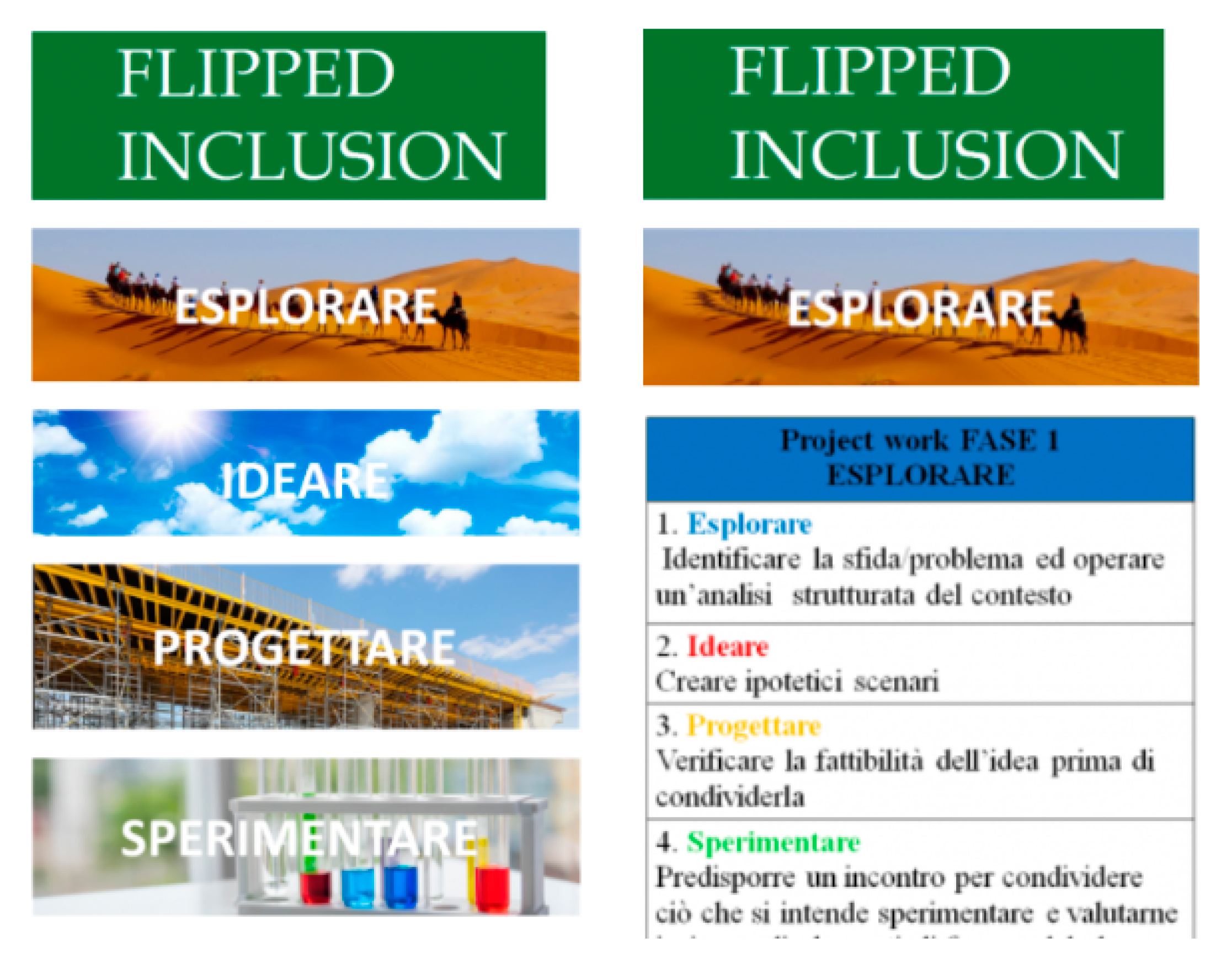

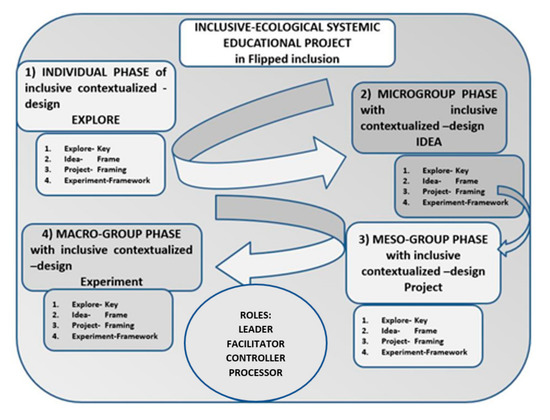

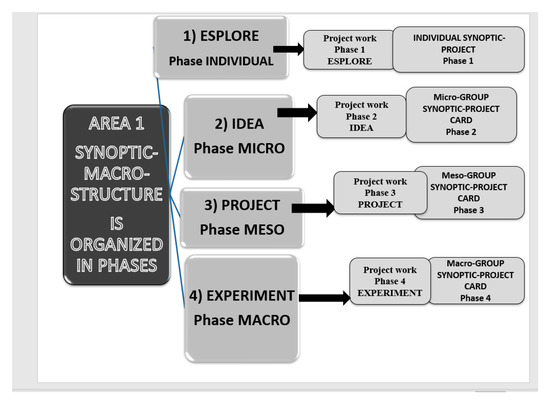

The Flipped Inclusion design model (Figure 1) is organized in four sequential macro-transformative phases [70], ordered by descending logic - top down - with the didactic-design application of frame analysis, and bottom up, with transversal cooperative organization, in a systemic ecological system ascending perspective. The macro-project architecture of the Flipped Inclusion model envisages simple levels of cooperation, organized in phases of increasing complexity of the work: (1) individual; (2) in micro-groups of participants (with four components and four roles); (3) role mesogroup (leaders, facilitators, processors, controllers); (4) context macro-group (by class / course / school).

Figure 1.

Project work [12].

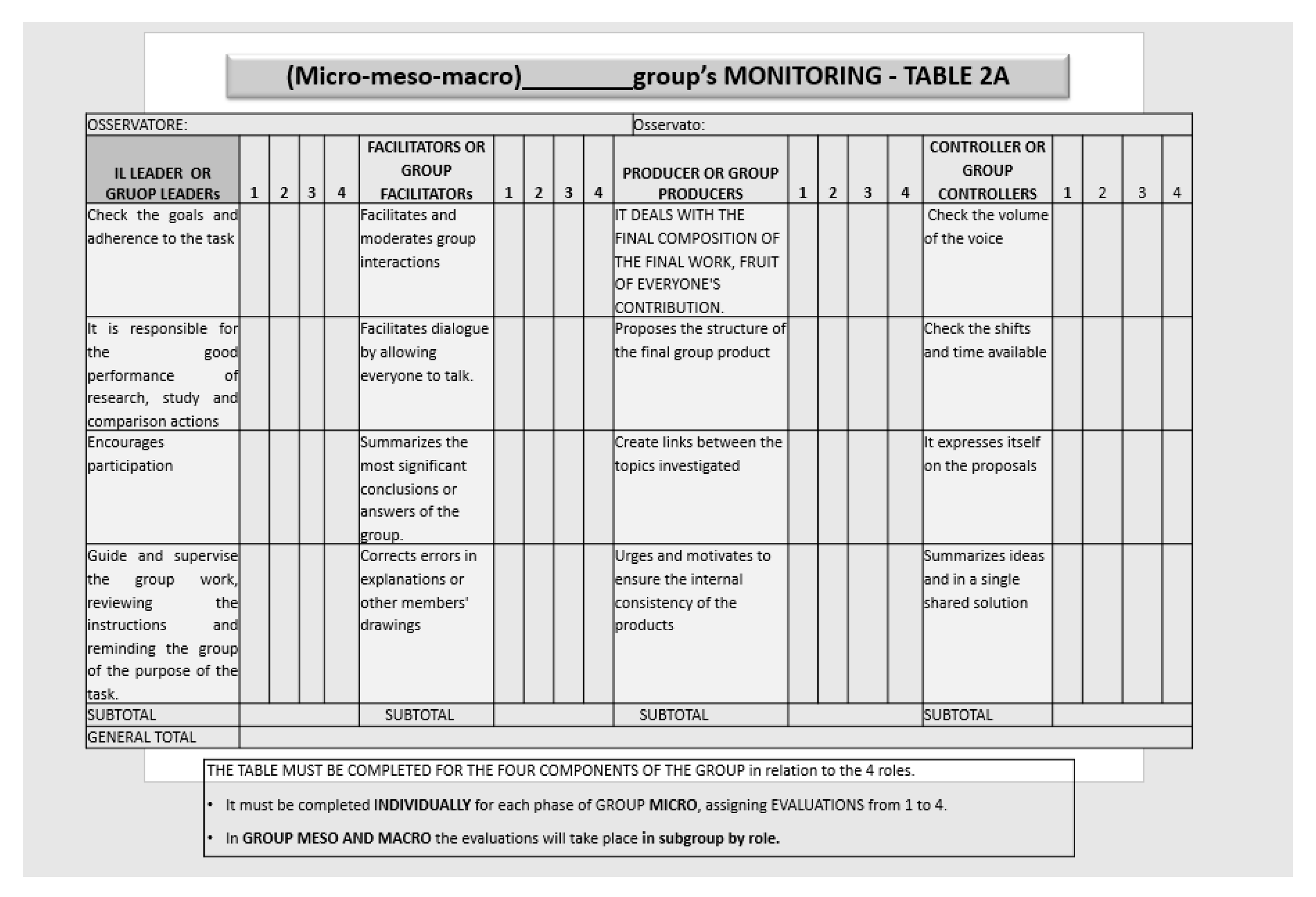

Specifically, for the definition of roles:

- (1)

- The Leader verifies the objectives and adherence to the task; he/she is responsible for the good performance of the research, study and comparison actions; encourages participation; guide supervises the team work by reviewing the instructions and reminding the group of the purpose of the assigned task.

- (2)

- The Facilitator moderates in group interactions; facilitates dialogue by allowing everyone to speak; summarizes the group’s most significant conclusions or responses; corrects errors in other members’ explanations or plans.

- (3)

- The Processor takes charge of the final composition of the work carried out thanks to the contribution of all; he expresses himself about the “form” to be given to the job; he connects the concepts studied at that moment with those studied previously; he asks for reasons and consistency with the format of the work.

- (4)

- The Controller checks the voice volume; check the shifts and time available; judges ideas, not people; summarizes the ideas and reasoning of the members in a single statement shared by all [32].

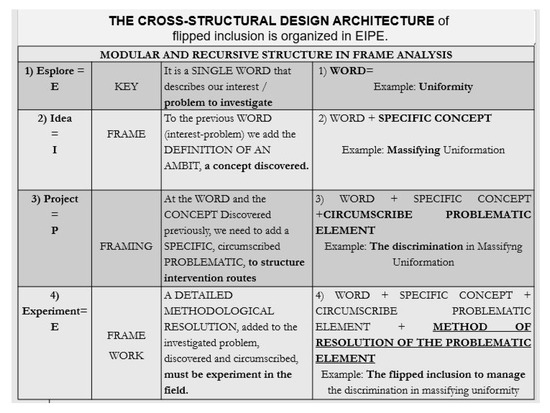

The EIPE matrix also makes use of a transposition of Goffman’s Frame analysis [60], through the stimulation of processes aimed at identifying anchors and forms of decisive selectivity. Systemic procedures are organized in phases of (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

The cross-structural design architecture of Flipped Inclusion [12].

- (1)

- Key (identification of the contextual stimulus);

- (2)

- Frame (selection of primary frame);

- (3)

- Framing (analysis of problems selected by focus–problem–context);

- (4)

- Framework (identification of methodological resolutions of elements of focus–problem–context [32] (p. 168).

In this sense, the educational value of simple teaching [46] organized in levels of learning, for disproportionate problems [49], is reaffirmed.

Investments are made in immersive teaching with moments of intense transference [71], organized for activities centered on the individual and on the context-class [25] through Empowered Learners [25], with personalized co-design phases, Problem Solving to promote resolutive skills [67] and Understanding [72] (p. 6), for a systematic organization of thought as understanding [25], in Empowered Peer Education mode [73].

The project work, structurally ordered and organized in a deconstructivist perspective [74], follows interaction procedures for increasing levels of complexity, is considered in sequence (times and spaces) between the persons, equipment, materials and information present in a system, carefully thought “to attribute the right importance to the human factor” [75] (p. 30). Retracing what the International Organization for Standardization reaffirmed in ISO 6385: 2016 [76] regarding the principles of ergonomics as basic guidelines for the design of work systems, flipped inclusion follows a cooperative approach throughout the exploration, idea, project and experimentation process with attention to human, social and technical requirements in a balanced way.

The EIPE phases also retrace the design phases of the ISO 6385: 2016 standard, such as: (1) Formulation of goals—requirement analysis; (2) Design concept; (3) Detailed design; (4) Realization, implementation and validation—(Analysis and allocation of functions and Evaluation) [76]. “Only the close collaboration between designers or system users allows a gradual progression of the phases which, at each step, must be discussed until the final goal is achieved” [75] (p.30).

- (1)

- The ergonomic phase of the Formulation of goals (requirement analysis) corresponds to the Exploration phase (problem finding). Conceptual nodes (Key) are collected, analyzed, interpreted and problematized, which reflects misunderstood experiences, recessive feelings, unpublished and unexpected thoughts, typical of the “private space of the self” [77] (p.1), which emerge from the requests made by the teacher (prompting), through the identification of social problems connected to the complex [78] and disoriented cross-media society.

- (2)

- In making use of the intrinsic motivational momentum, deriving from the process of active involvement of the learners, starting from Exploration phase, Flipped Inclusion positively predisposes the subjects to learning, with a view to an authentic anthropocentric enhancement of resources, potential and differences. The ergonomic pedagogical-inductive methodology used in this phase is Inquiry Learning [68], a process of discovery, investigation of problems, critical co-discussion and decisive research in a constructivist perspective [79]. By stimulating the acquisition of knowledge through investigation, participatory action [80] and the formulation of questions in a phenomenological perspective, the trajectory of a disseminated and embodied community of pluralities unfolds, free from the oppression of unrecognized needs.

- (3)

- The Ideation phase of Flipped Inclusion traces the Design concept of the ISO norm [76] and is based on the conceptual circumscription of the macro-areas of problems previously identified and inspected. It consists of the generation and selection of the most innovative ideas, in view of the didactic elaboration of interpretative frameworks of the conceptual framework of the social problem explored. This is the phase of the problem setting and analysis, in which “the keyword (Key) becomes a concept, with sequential chaining and reinforcements” [53] (p. 139). Through the ergonomic Discovery Learning methodology [65], the student discovers the conceptual relationships of a given domain of knowledge and “enhances the retention of information by virtue of their autonomous organization and transformation” [81] (p. 176). The result of inductive procedures, the discovery as a surprise stimulates an intuitive meaningfulness capable of mobilizing the cognitive–cultural heritage of the learners involved, detaching the individual from an empirical vision of knowledge to promote the construction of inclusive prosocial profiles capable of refuting the incurrence of doctrines tout court.

- (4)

- The detailed design of the International Organization for Standardization 6385: 2010 is reaffirmed in the Project phase of Flipped Inclusion “which represents the set of the key word that has become the concept (Frame), to which is added the challenge problem on which the intention is to carry out the search for resolution (Framing) “[53] (p. 139). Through the specific specification of the interrelationships of the meanings investigated, the aim is to plan the actions necessary for the creative resolution of the problems analyzed (problem solving and creative thinking). In order to pursue inclusive equity, with a view to enhancing the potential of contemporary anthrophos, ergonomic–anthropocentric learning by mastery or mastery is adopted [57], through a preparatory, individualized and diversified path of objectives ordered by increasing complexity. In an ongoing activity of modulation and ethical redefinition of means and ends [82], the Flipped Inclusion model aims to redefine any homologating, socially connoted attitudes.

- (5)

- The implementation and validation ISO-2010 is present in the decision taking of the Experiment phase of Flipped Inclusion, a step that allows the shared, re-defined and progressive resolution of explored, circumscribed and problematized conceptual nodes (Framework). Using the methodology of experiential learning, the systematic reflection of the experienced experience unfolds in a recursive cyclicity, in which knowledge is configured as the product of a previous experience of which it is the result [68].

In a continuous transaction of anthropocentric cognitive, ethical and emotional solicitations (insight), the acquired experience becomes cognitive heritage, the principle of subsequent explorations (Key), in a dynamic process of identifying the purpose with the objective, no longer originated from a simple instinct, for the root of personal lived experience. In this way, the trajectory of the development of the Person unfolds [83], which implies a cognitive–behavioral change of free will to act, a basic prerequisite for reflecting on the community principle of being aware and sentient of the systemic value of society.

The ergonomic–anthropocentric phases of the Analysis and allocation of functions and of the Evaluation [76], from the perspective of the Flipped Inclusion model, are configured as transversal to the process phases. To structure and consolidate the interactive circuit of co-responsible human actions, related to the development of community moral action, Flipped Inclusion invests in a democratic management of knowledge, centered on the system of roles (Leader–Facilitator–Controller–Processor), in view of the assumption of unprecedented forms, faculties and possibilities. Through group logic, the giving of divergences, conflicts and discrepancies, one experiences belonging to a community of life, in a relationship made of mirroring and self-transcendence.

Complex mixed learning systems and formal, non-formal and informal [52], real and virtual settings used in the classroom and outside the classroom.

In Flipped Inclusion, investments are made in the construction of stimulus environments aimed at promoting generalization processes [24], through co-responsible prosocial mediation paths. The preparation of formal, non-formal and informal architectures of sharing, interaction, collaboration and cooperation for and between levels of increasing complexity took into account the rules of learning together [58] and complex education [84]. All this allows the promotion of integrated, off-line and on-line management training courses between two levels of community; of educational practice with educational–inclusive approaches, rooted in the values and centrality of the Person, in a mutual exchange of experiences and information, to search for solutions; of learning (for the acquisition of knowledge, skills and competences, based on reciprocity of intent and interventions), finalizing both learning processes to the inclusive prosocial meta-competence.

The flipped inclusion model explored, investigated and described the activation of dynamically critical intersubjective [3] trans-educational processes [85], which traverse the structural logics of computational thinking, knowledge management [86], and in particular, the DIKW pyramidal hierarchy organized in EIPE matrix:

- (1)

- Explore/ D, usData information, data collection.

- (2)

- Idea—I, us Information, with a process of aggregation and contextualization of data, transformed into information.

- (3)

- Project—K, us Knowledge, transformation of information into organized knowledge.

- (4)

- Experiment—W, us Wisdom is the phase of metacognitive wisdom and personal, experiential reworking.

Ergonomic–educational interventions, as envisaged in Flipped Inclusion, presuppose the involvement of people in the planning and control of their own activities, on the basis of sufficient knowledge and autonomy to influence both the processes and the results [87].

One of the aims is to promote prosociality in media ecological education, investing in social nature and in peer-communication and media-education as proactive proximity, through the promotion of an anthropomedial empowerment that transcends individualisms [88].

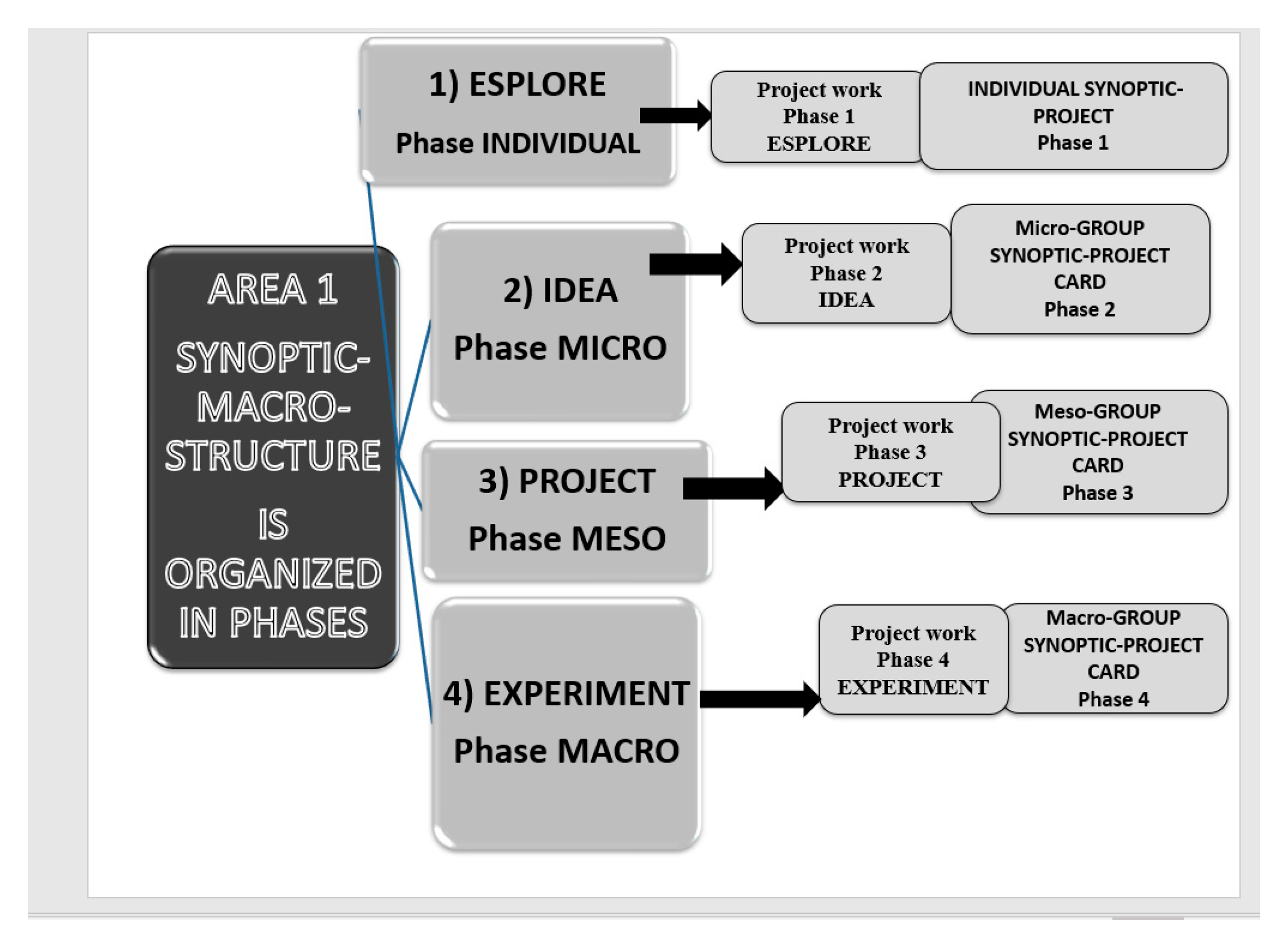

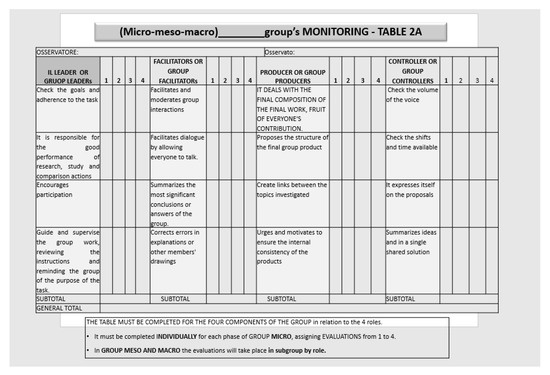

For this reason, the activities tested in the research (1) followed individual work phases, to responsibly explore ways of action; (2) were in micro-groups, to allow proactive design through forms of interaction; (3) were in a mesogroup, to design collaborative forms of proactive co-responsibility; (4) were in a macro-group, to experiment with forms of co-responsible, proactive and prosocial cooperation (Figure 3).

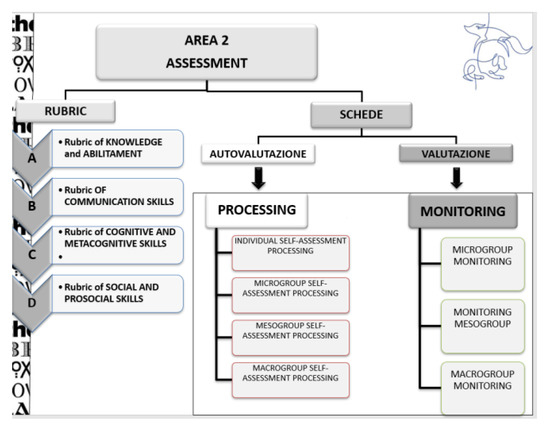

Figure 3.

Assessment Flipped Inclusion [12].

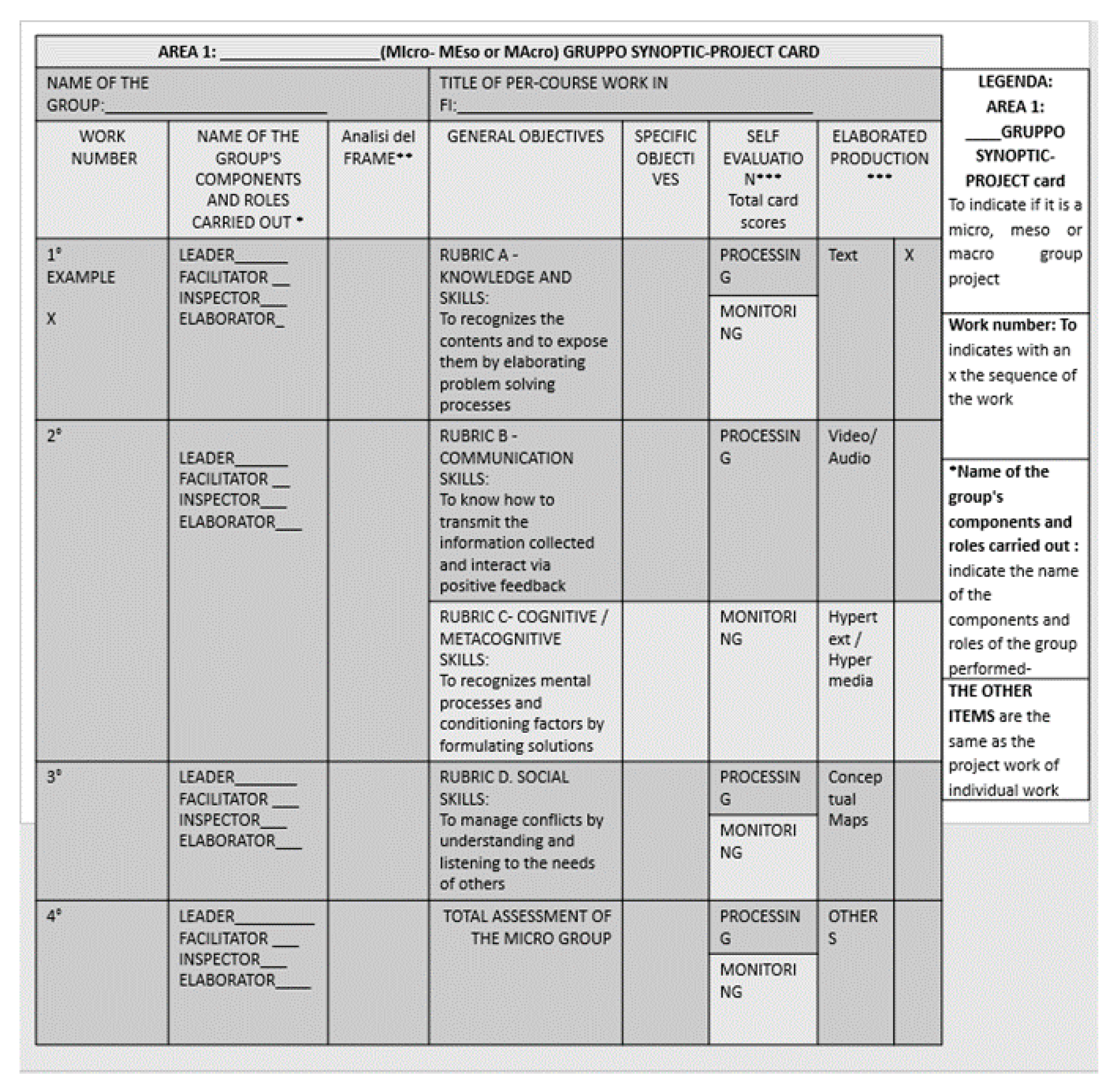

The Flipped Inclusion project work is organized by modular and recursive focus groups of increasing complexity (micro, meso eso and macro). Specifically, in the macro-architectural design:

- the exploration phase corresponds to the process and product and individual level;

- the idea phase is at the micro-group work level;

- the phase of planning at the level of work in the meso group is organized by roles (leaders, facilitators, controllers, processors;

- the phase of experimenting is at the process level and produced in macro group.

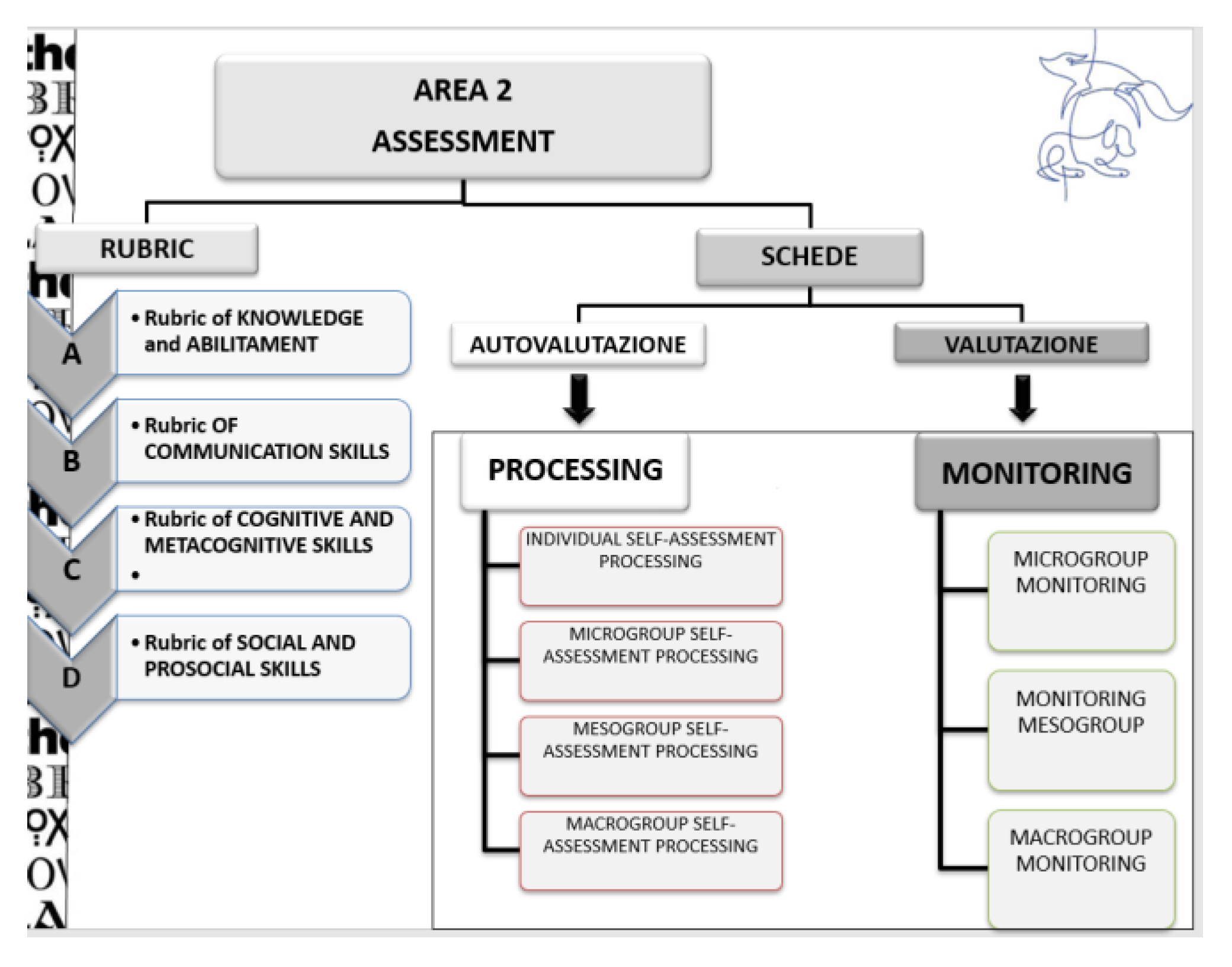

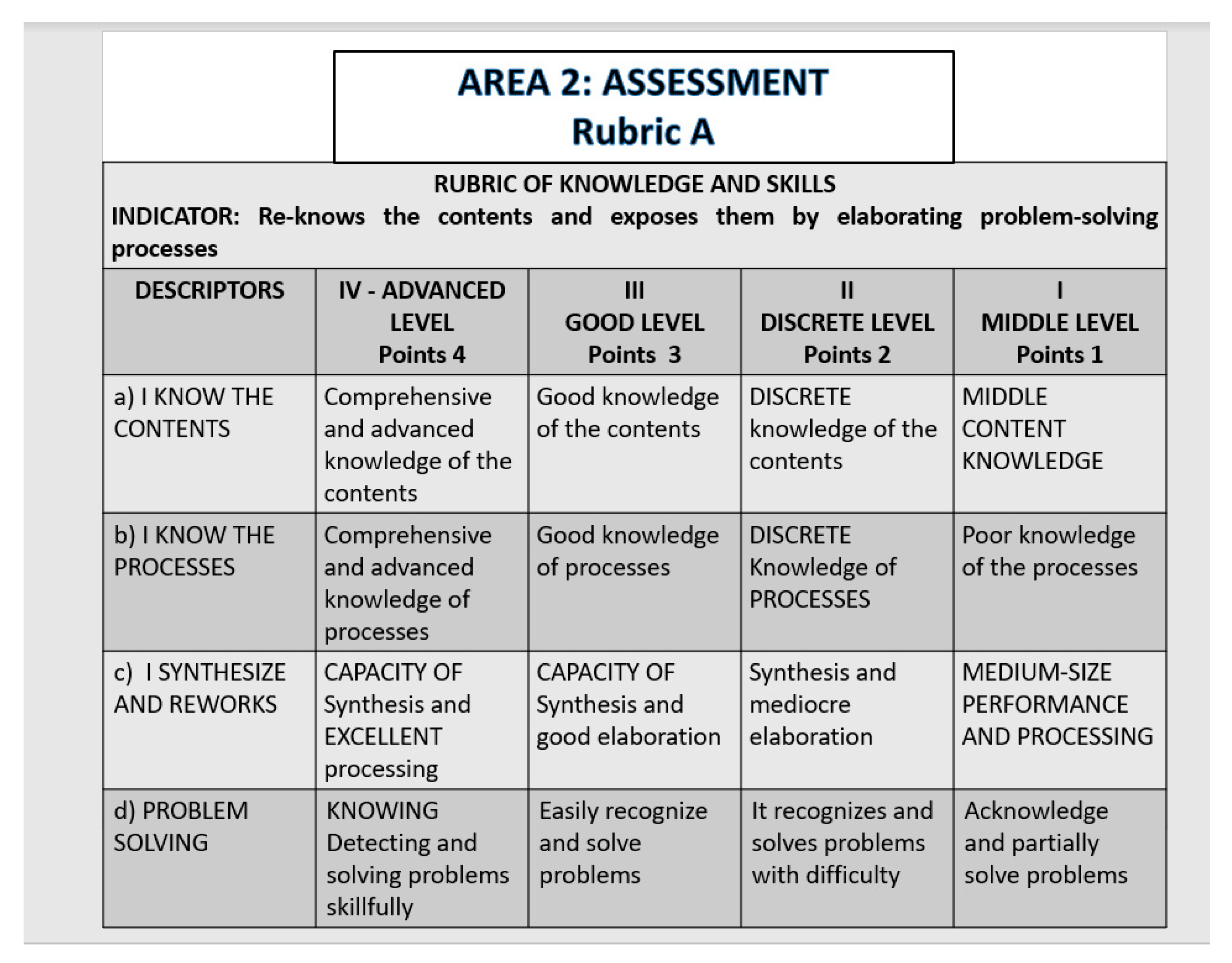

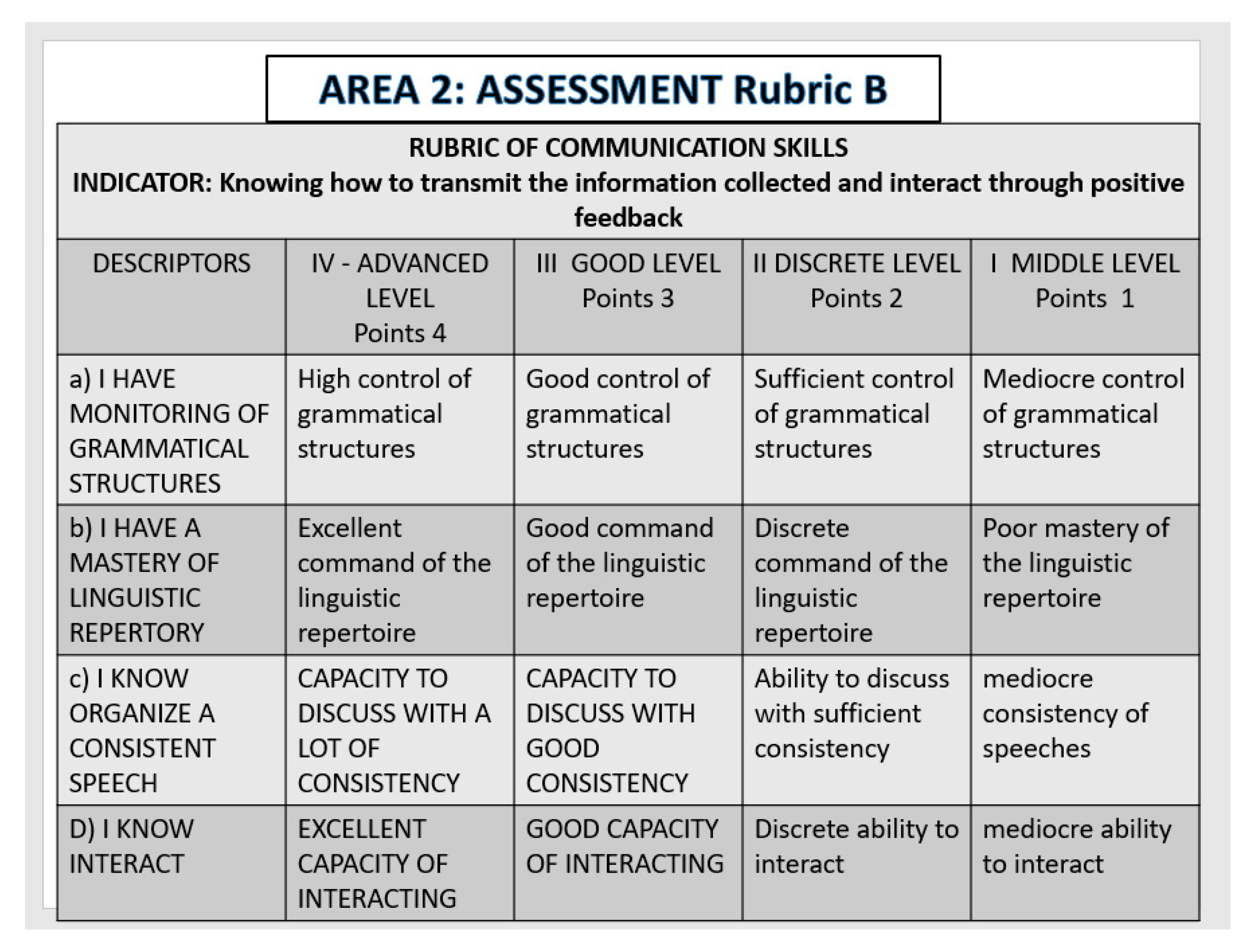

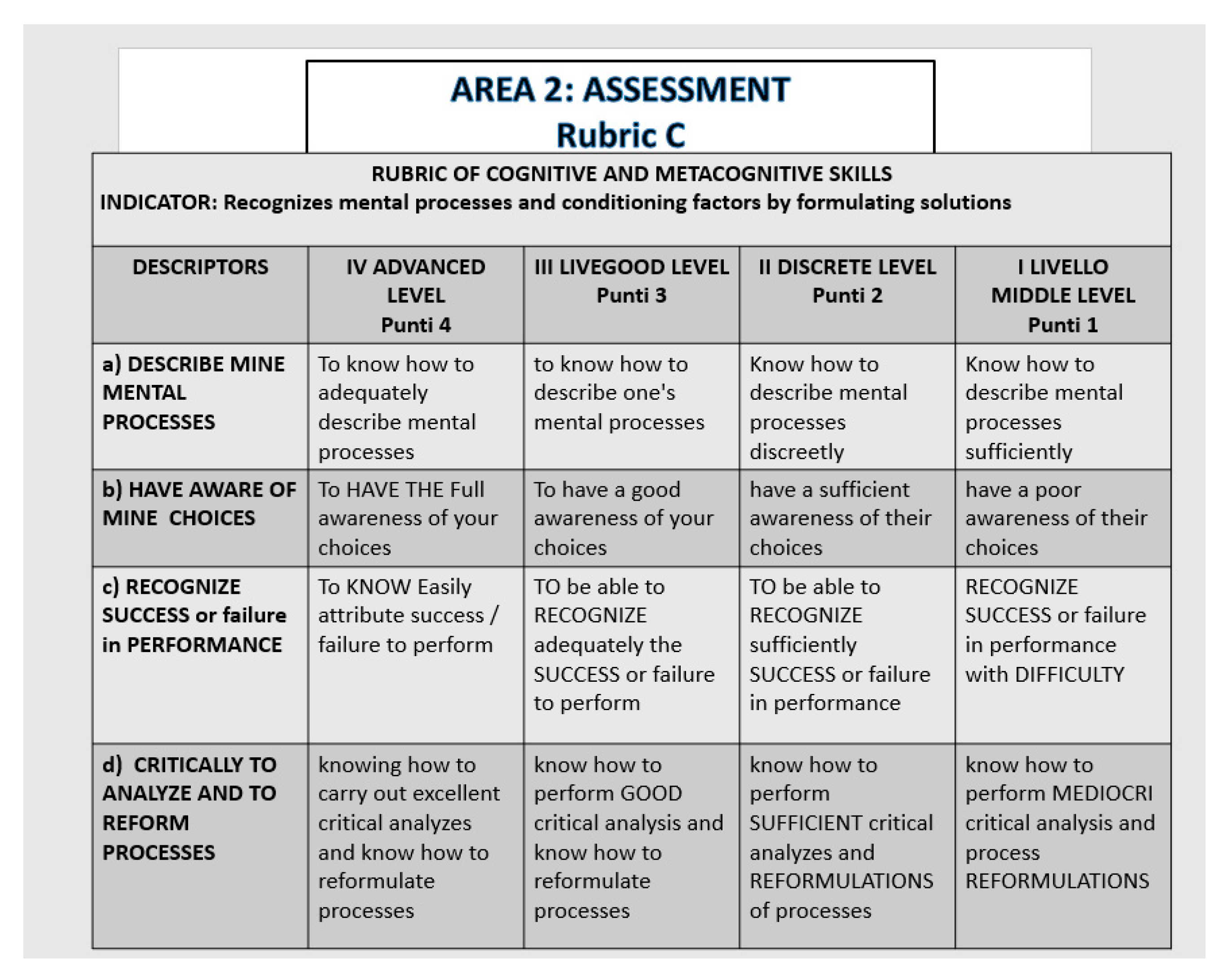

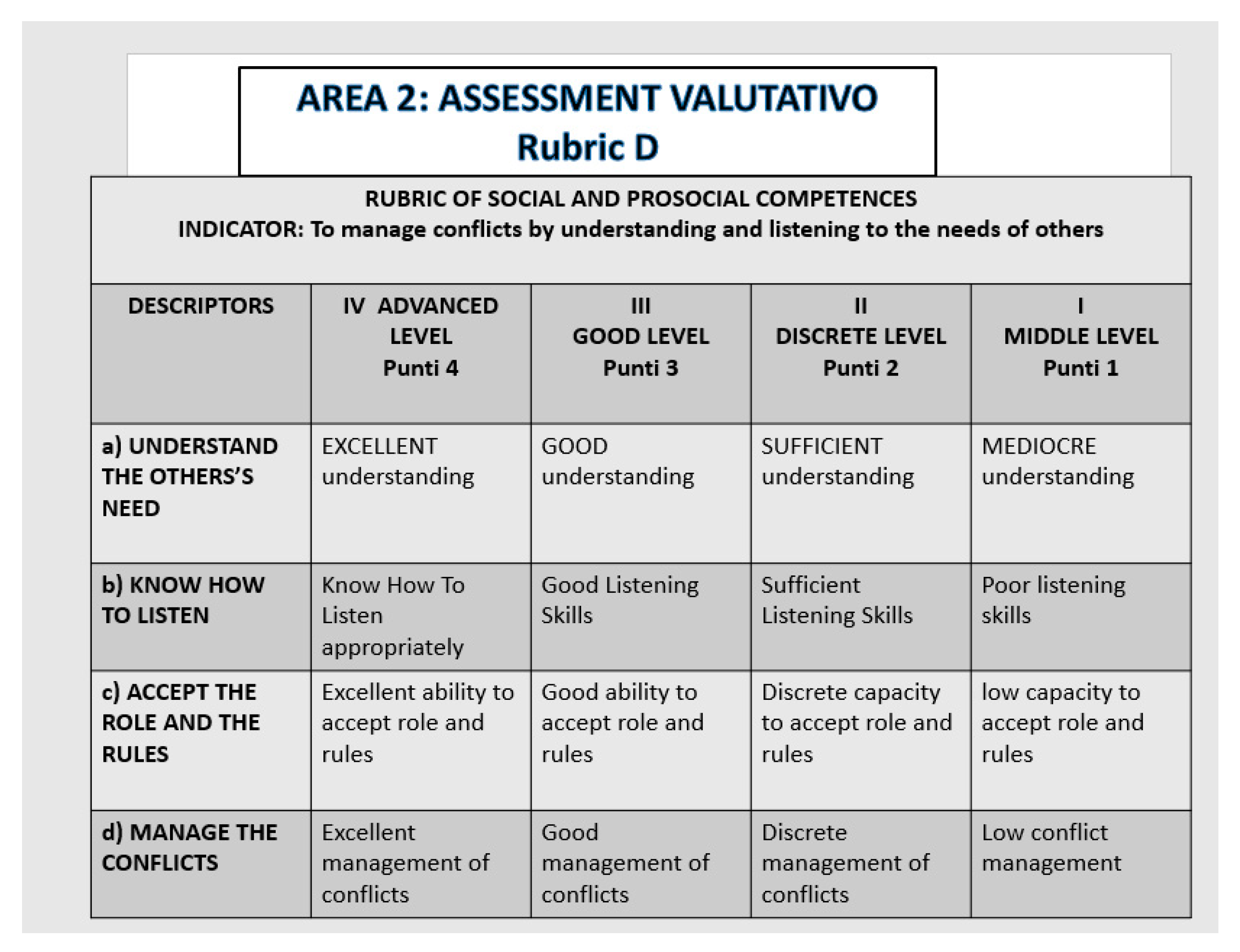

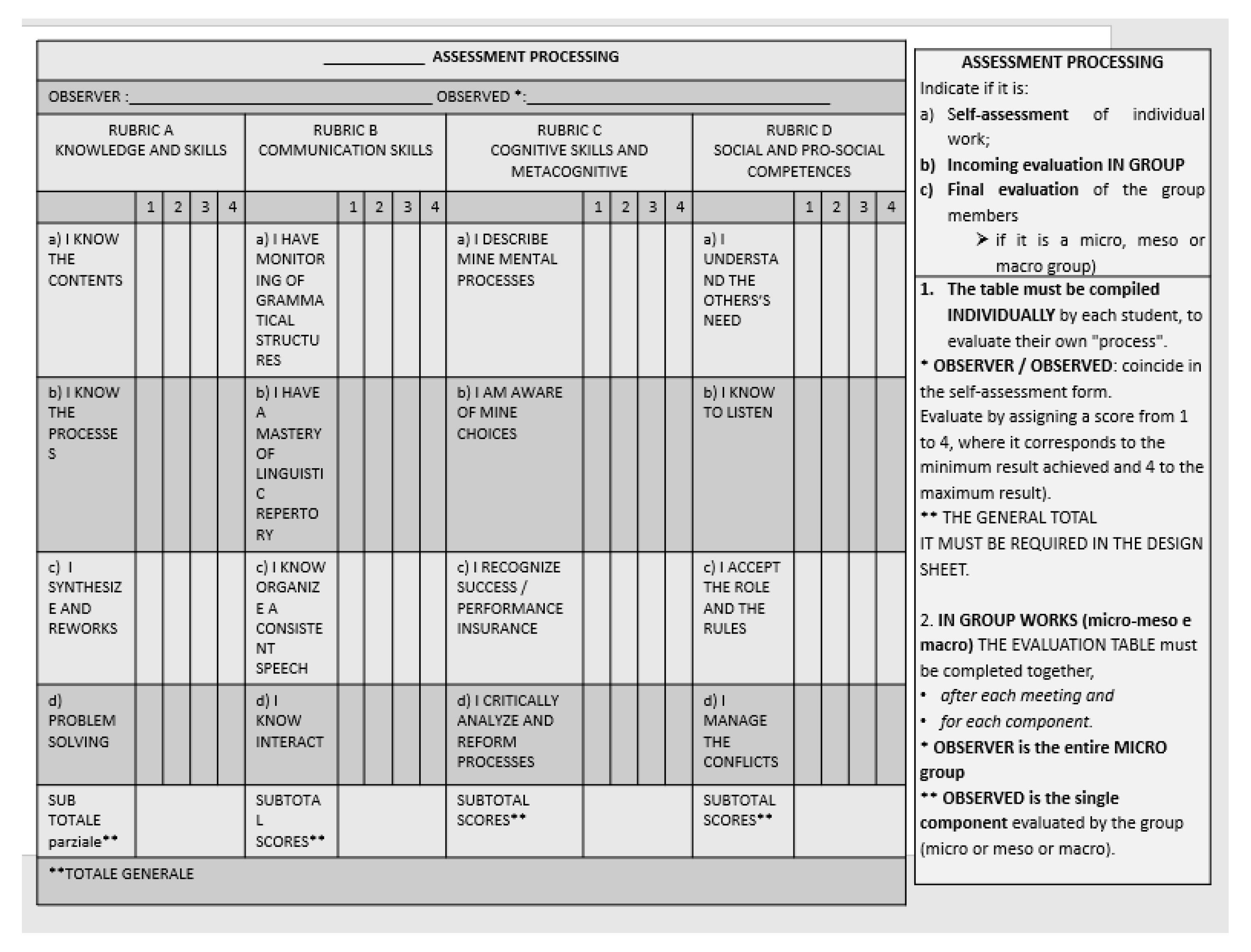

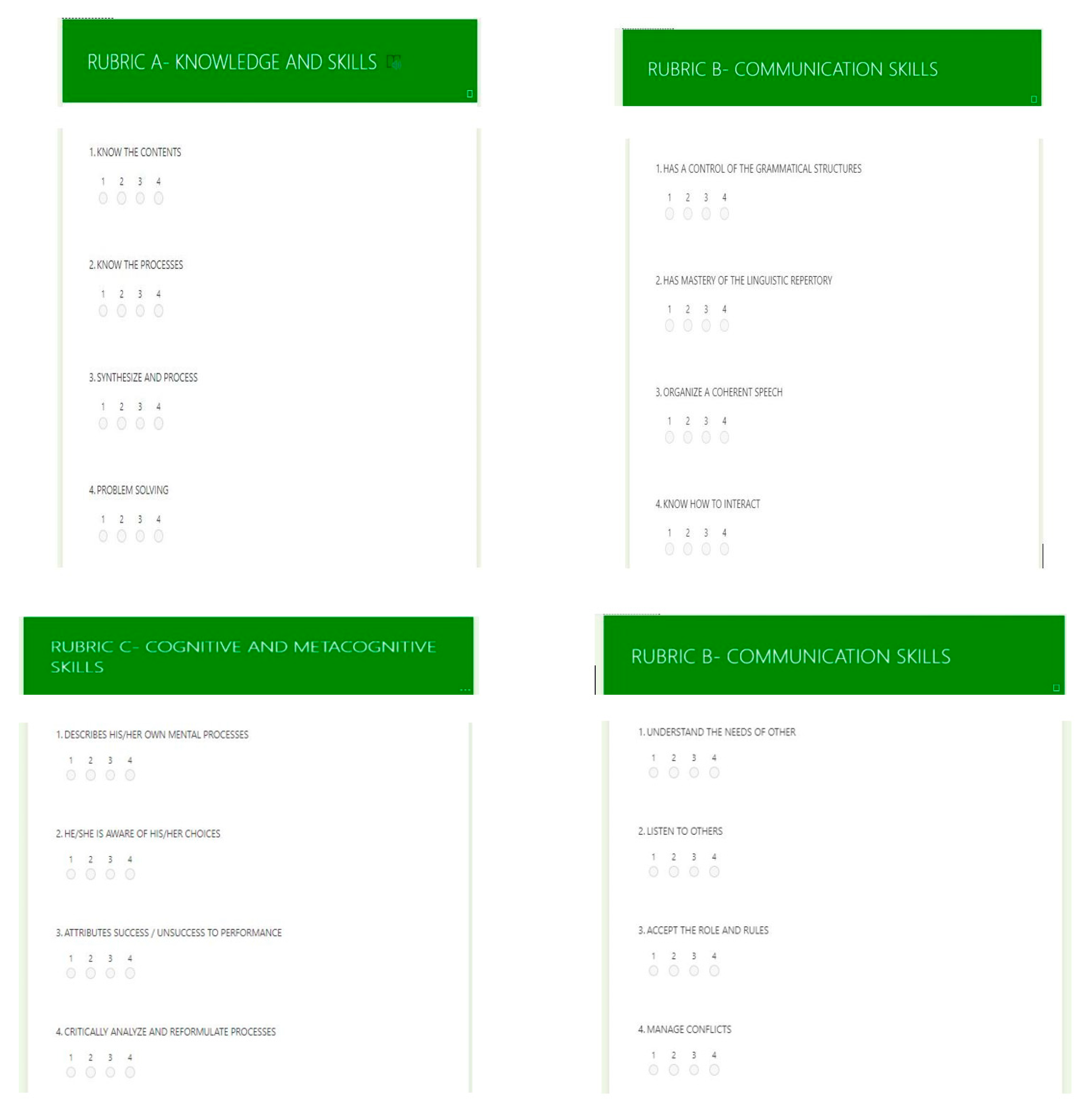

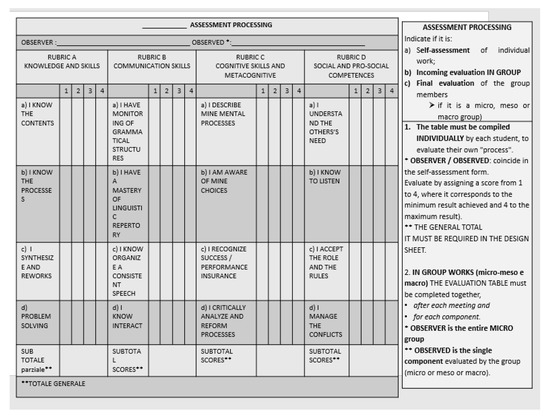

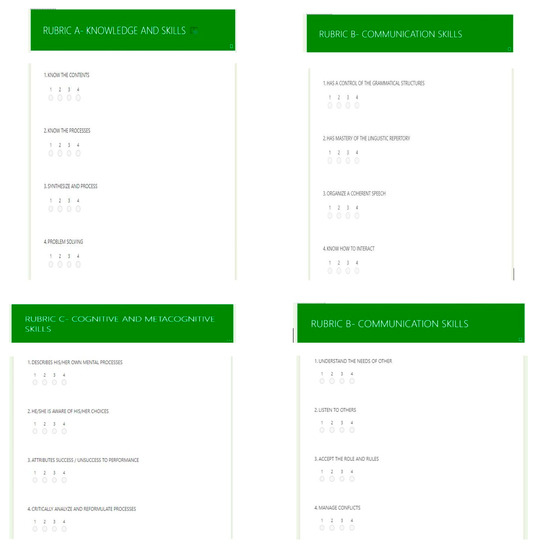

In order to manage the complexity of the intervening variables in progress and to rebalance the processes through systematic and non-extemporaneous feedback, Flipped Inclusion consists of a constant evaluation and self-evaluation control in the pre (monitoring)–post (processing) carrying out of the micro-months -ex and inclusive macro contextualized designs, with ergonomic cards organized according to standard evaluation rubrics by role, objective (communication/cognitive skills and knowledge/cognitive/social and prosocial goals) and phases [52]. Links have been prepared for monitoring, self-assessment and evaluation, initially and finally online, by stages and levels (Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8).

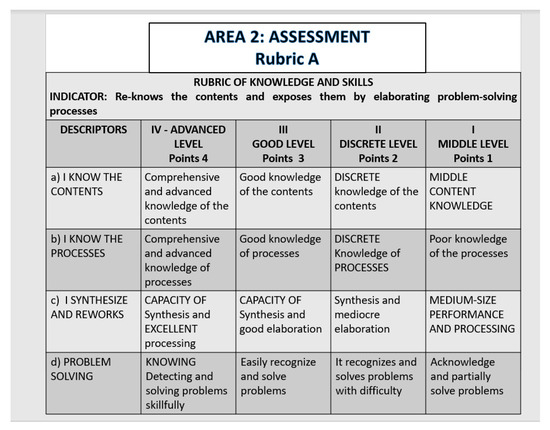

Figure 4.

Assessment in Flipped Inclusion.

Figure 5.

Assessment Rubric A—Flipped Inclusion [12].

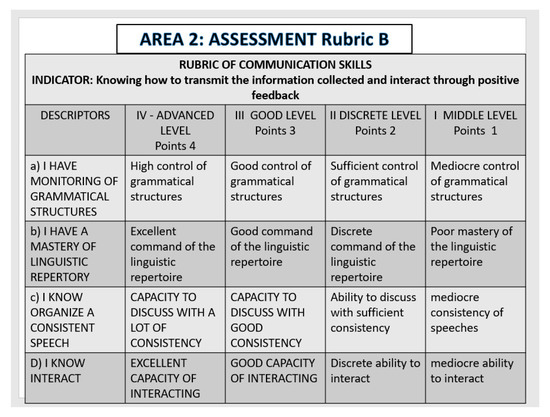

Figure 6.

Assessment Rubric B—Flipped Inclusion [12].

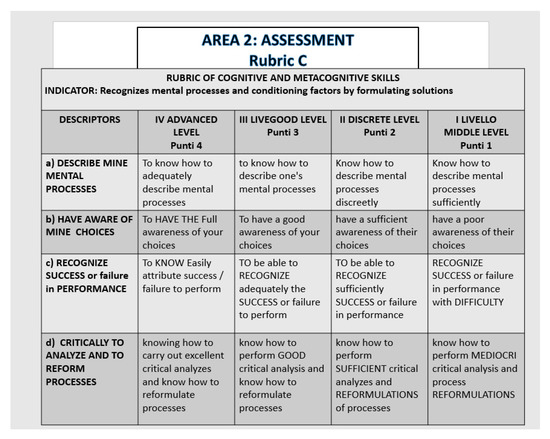

Figure 7.

Assessment Rubric C— Flipped Inclusion.

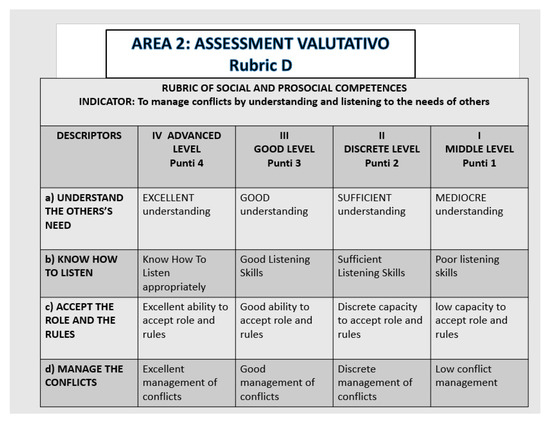

Figure 8.

Assessment Rubric D—Flipped Inclusion [12].

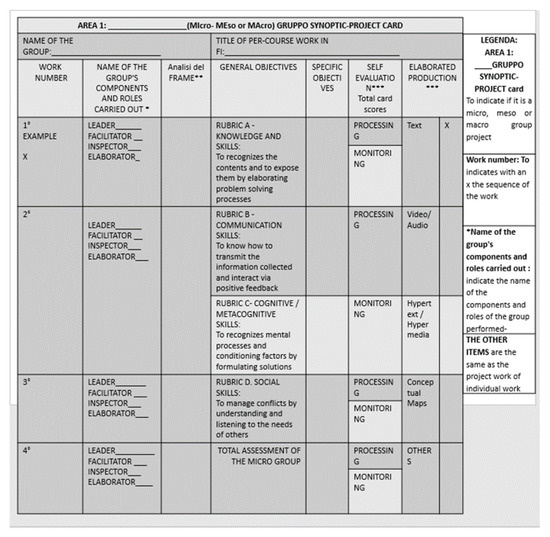

Each phase and each level of the training path presents a precise evaluation organization structured in monitoring and elaboration by levels of cooperation. It is an evaluation organization, recursive by levels and modular for monitoring and processing (Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11).

Figure 9.

Processing structure—Flipped Inclusion [12].

Figure 10.

Processing monitoring—Flipped Inclusion [12].

Figure 11.

Synoptic project/evaluation sheets [12].

Below is an example of the evaluation sheets and the four evaluation categories, designed in top down mode, in collaboration with the students/interns (sample of the three-year longitudinal study).

Each level follows an assessment with quantitative, recursive and modular detection forms submitted to students by process levels and by intergroup.

The evaluation phase performed a social certification function of experiential results in the research–action activity of inverted inclusion, with an educational investment in reflexive–metacognitive processes, as tools of self-awareness. The following have been carried out:

- personalized evaluation to measure objectives achieved, with respect to the starting levels;

- authentic alternative evaluation to evaluate processes with self-evaluation methods to learn self-efficacy and a pro-social co-evaluation;

- socialized assessment, managed by groups;

- mixed external evaluation, functional to self-esteem, focused on individual and comparative progress.

The research was dictated by the desire to examine, discriminate and highlight conclusions based on the evidence and starts from the assumption that “scientificity is a procedural quality of life” [32] (p. 133). It was multi-method research, developed as the integration of two heuristic models, traditionally antithetical, ontologically and epistemologically, in the field of educational research (action-research) [89], with an interpreter, hermeneutic and critical position, oriented towards the emergence of experiential meanings and experimental research, in a positivist position, from the objective, realistic and linear interpretation of the observed phenomena [90]. The research was developed as an integration of two traditionally antithetical heuristic models, action-research and experimental research. Qualitative and quantitative approaches have been integrated, using qualitative investigation techniques (focus groups, participant observation with descriptive evaluation), and quantitative tools (structured questionnaires and structured evaluation forms), to guarantee empirical data and produce a critical reflection [91] and a shared attribution of meaning [92] (p. 135).

For quantitative data, a comparative analysis was carried out between the tabulated data of the structured assessments, monitoring by levels (individual phase, in micro-group, mesogroup, macro-group) and processing by role, the results of the questionnaires [93], and a re-test 3 years from the application of the methodology of the sample made up of 80, split between pupils and interns, for which a synchronic comparison of the same was carried out by course and by stages of the courses. Furthermore, the data collected through the Toronto Empathy Questionnaire standardized test [94], a measure of psychometric empathy with a factorial–analytical solution with multiple empathic measures, were also taken into account to evaluate the research aspects related to social cognition and the promotion of prosocial behavior with the application of the Flipped Inclusion model; the questionnaire was administered at the entrance and exit to a sample of 20 students.

For the collection of qualitative data, the hermeneutic approach was followed, with textual data deriving from the reports of individual observations [95] and of the micro, meso, exo and macro groups [32] (p. 136), and taking into account the methodological [96], visual sociology [97] and sociology of images [98] (p.137) investigation techniques, for the evaluation of audio–video products (viewable on the flipped inclusion.it website or on the flipped inclusion Facebook page), evaluated as a personalized translation of subjective and intersubjective phenomenological readings.

The significance of the assessment was based on the global identification of predicted, observable and measurable behavioral performance levels. The range of variability was defined as the range of expected performance levels and the expected number of ratings, each of which was associated with a numerical value, thus arriving at an overall value of the results achieved.

In assessing social skills we have not ignored principles such as:

- discussion, to examine and define the skills to be learned and the recognition of new behaviors;

- objectivity, observation of prosocial behaviors, to induce imitation;

- reinforcement, understood as any event that increases the probability of emitting behavior;

- reflection on experience.

2.3. Materials

In the Flipped Inclusion model, the experimentation of inclusive communities was also proposed through a didactic organization, aimed at acquiring co-built knowledge, skills, social problem solving skills, which are contingent and dependent on the context. The goal is to integrate community levels, making use of formal, non-formal and informal learning contexts and off-line and on-line virtual learning environments, designed to promote inclusive prosocial meta-competence.

For the design of activities in inverted the inclusion mode, virtual platforms such as Blendspace and Spiral were used, but above all the website flippedinclusion.it. It allows a choice of communication tools, exchange of materials and audio–video productions.

To foster skills of (1) investigation, (2) discovery, (3) resolutive-design and (4) experiential mastery, complex blended learning tools and platforms were used, as well as the flippedinclusion.it website, which through instrumental communication exchange options, meetings and the production of audio–video materials, with access to a reserved area, allows the use of 4 types of formal learning environments [87].

- Scheduling, to publish and define deadlines, appointments, fixed-term objectives;

- Conferencing, to define discussion topics and manage folders for the storage of materials and messages;

- Document sharing and Link sharing, to share documents on the net and individual and group links.

- Personal messaging, to send and receive individual, micro, meso, exo and macro-group messages.

The initial and final links that refer to the self-evaluation and the monitoring of the evaluation are both provided online, by stages and levels.

3. Results

3.1. Research Contexts and Sample

The processes activated in research on the Flipped Inclusion model, in retracing the postmodern logic in an anthropological–paradigmatic key, confirm the importance of an inclusive transformative didactic action. In fact, Flipped Inclusion, focusing on pro-active anthrophos, as the protagonist of the co-built training event [99], aims at an educational reconstruction [100]. Flipped Inclusion therefore promotes capitalization of the communities, as places of reality with increased spaces and times, in which being completes itself into post-modern becoming, whose cross-media processes highlight the educational need for prosocial management of incessant and trans-mediated trans-figurations. The investment in the person, as an ontological synthesis of the ergonomic project in the hermeneutics of being, is the cornerstone that must be educated for in order to to experiment with systemic inclusiveness, even on the net, in an exclusive joint merger union. In the use of Microsoft Teams, a dynamic-non-linear platform, we invest in the constitution, also in e-learning, of “a place of exploration and focus on complex problems, pluralistic discussion, collective decisions and evaluation of results” [101] (p. 72). In crystallizing and establishing social relationships [102], profiles that are significantly connected at an interpersonal level, Flipped Inclusion fits into the horizon of “renewing pedagogies” [103], undermining the insular conception of man, but luminary of the anthropocentric, ecological-systemic value subjectivity [104].

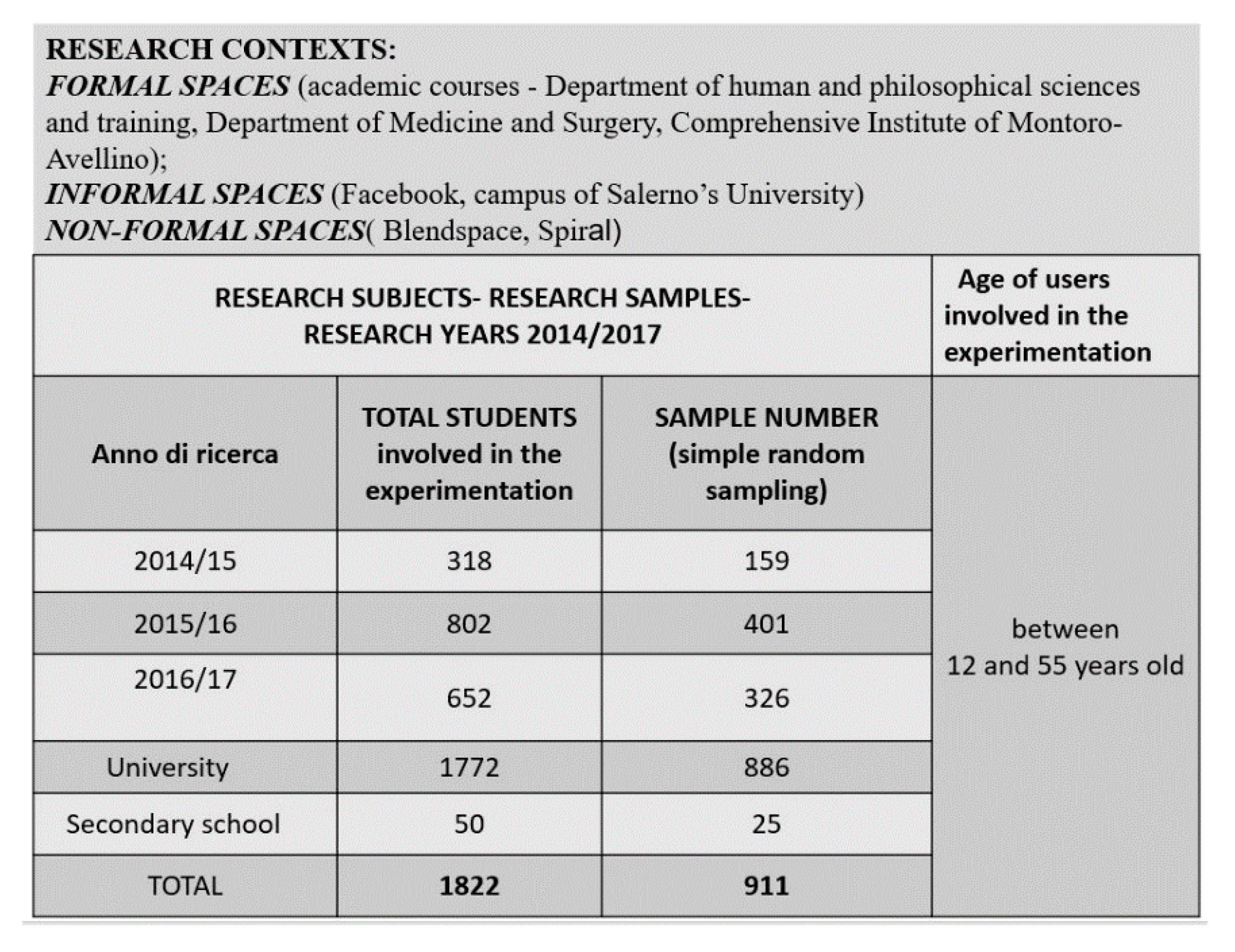

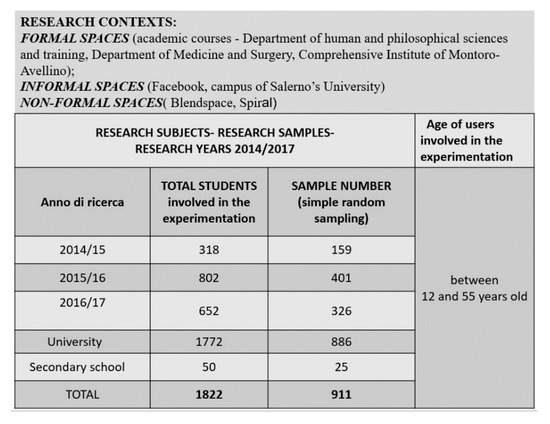

The interpretative–descriptive–transformative longitudinal pilot study [51] in the years of experimentation of the model from 2014/17 has seen the involvement of 1772 university students (of which 25 have also carried out internship activities for a three-year period and allowing them to obtain information from the longitudinal perspective) and 50 students of a compulsory school, for a total of 1822 students, and a simple random sampling of 911 people.

It took place in formal (academic courses, school) and informal spaces (campus of the University of Salerno—Department of human and philosophical sciences and training, Department of Medicine and surgery). Spatial and institutional contiguities were used to obtain convenience from the point of view of information collection. The research verified the hypothesis formulated on a sample composed of academic students, trainee teachers and compulsory school students, with a methodological–didactic–laboratory framework. The students involved ranged in age from 12 to 55 years and were also part of Active Training Internship courses. The subjects involved in the research and the research samples were (Figure 12):

Figure 12.

Research contexts, research subjects, research sample.

3.2. Data on the Impact of the Model

The impact of the Flipped Inclusion model was investigated, with the cross-media application applied in the classroom and beyond the classroom on:

- (1)

- inclusive learning (knowledge and skills), cognitive and attribution styles (communicative and socio-relational);

- (2)

- promotion of inclusive, ecological and systemic prosocial contexts.

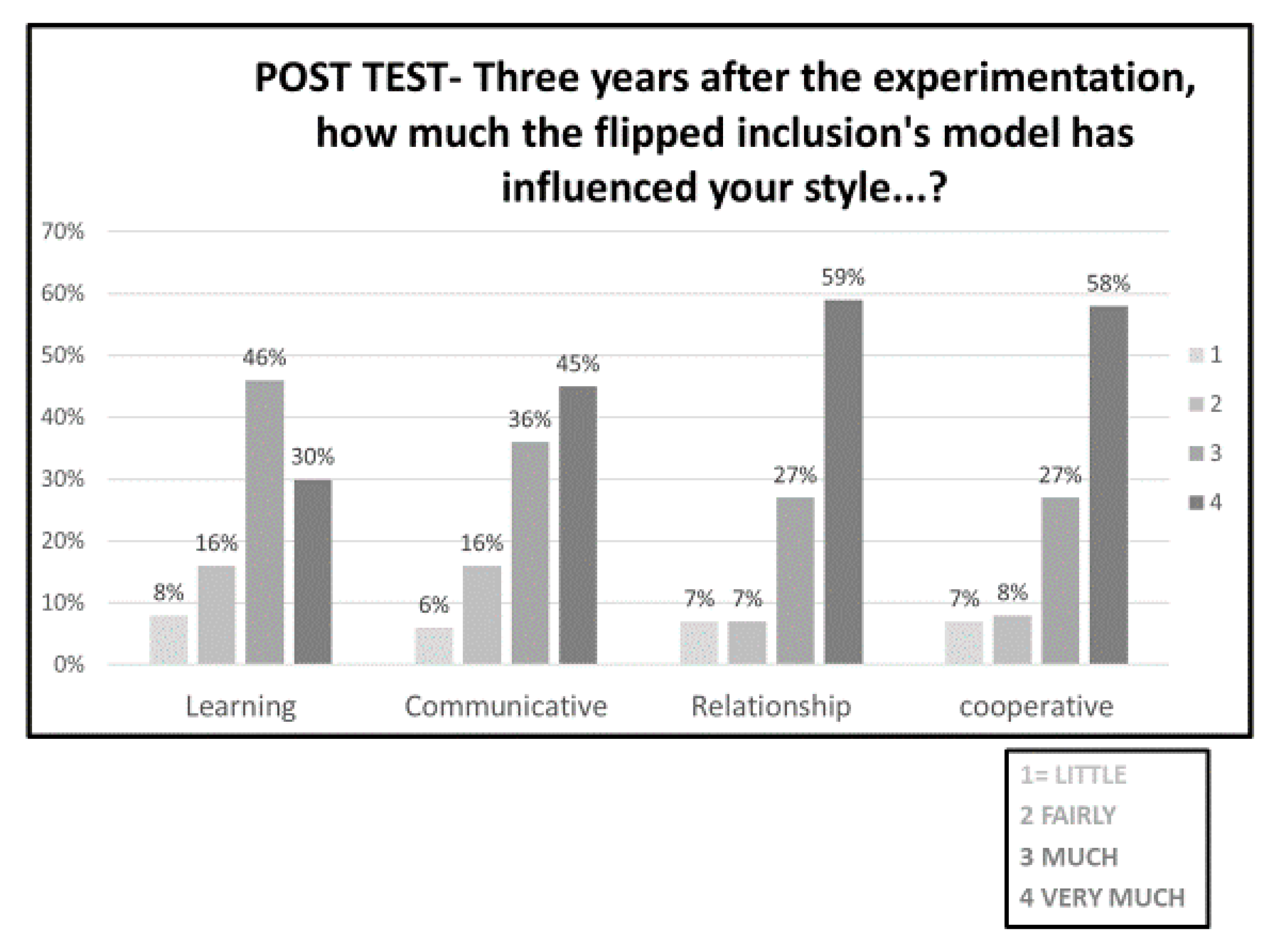

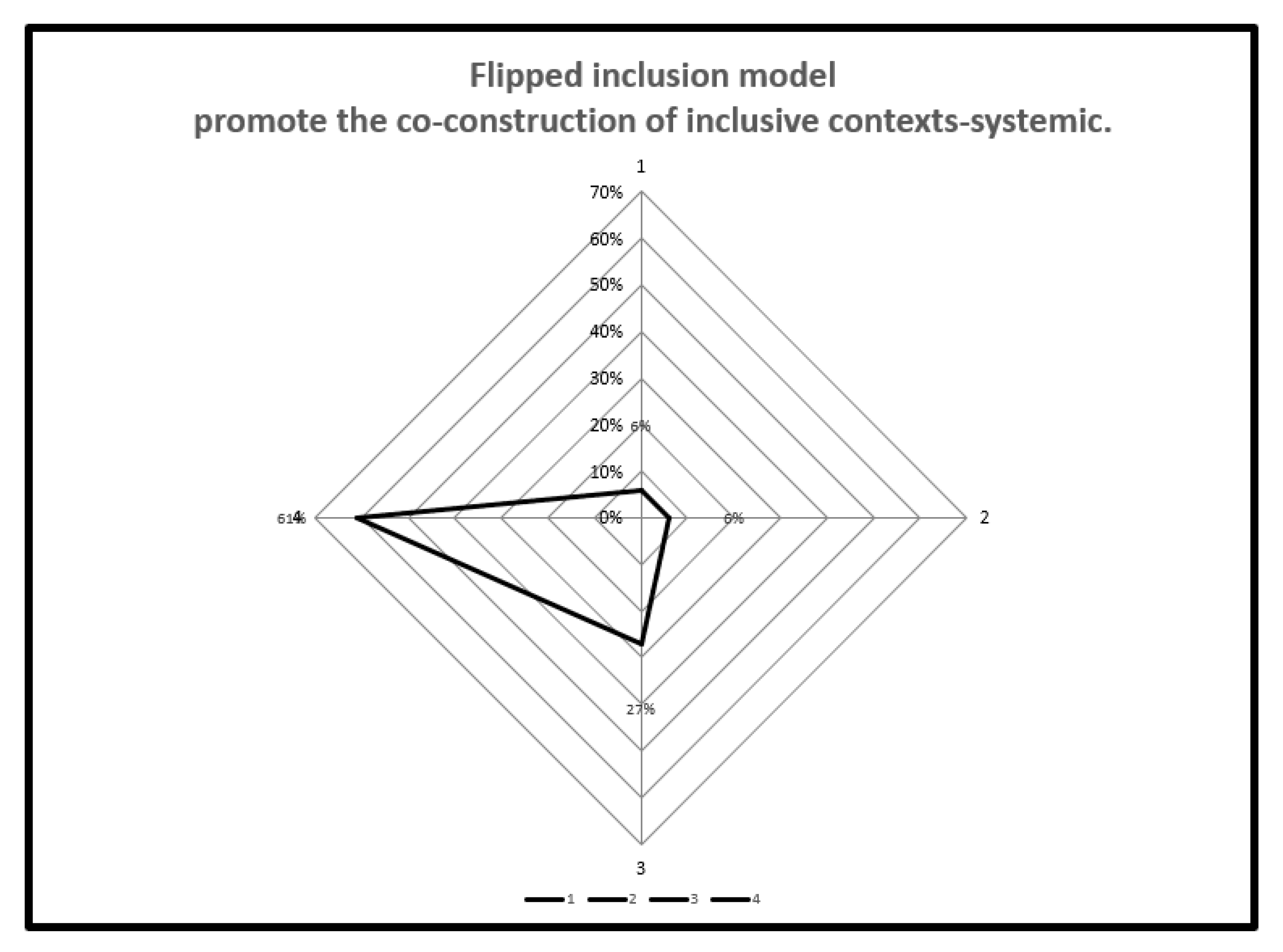

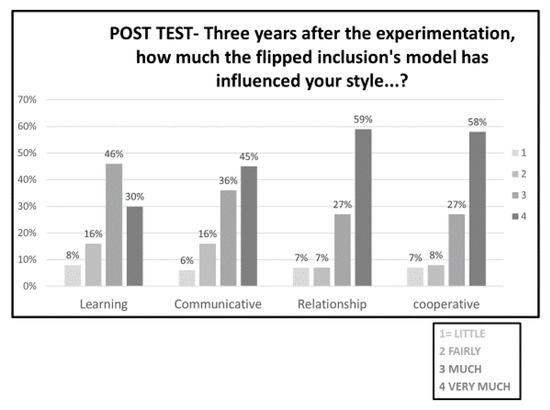

From the first research question (the methodology helped facilitate your study method and influenced your styles (learning, cognitive and attribution–communicative, relational, cooperative)) it emerged that 58% found a change of cooperative style, for 59% it an impact on the relationship style [32] (p. 207) and for 45% on the learning style; only 6% believed that the methodology did not influence their communication style (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Data—learning, communicative, relational, cooperative styles [12].

In reference to the first question of the research: has the methodology helped to facilitate your study method and has it influenced your styles (learning, cognitive and attribution–communicative, relational, cooperative) and prosocial and plural inclusive profile?

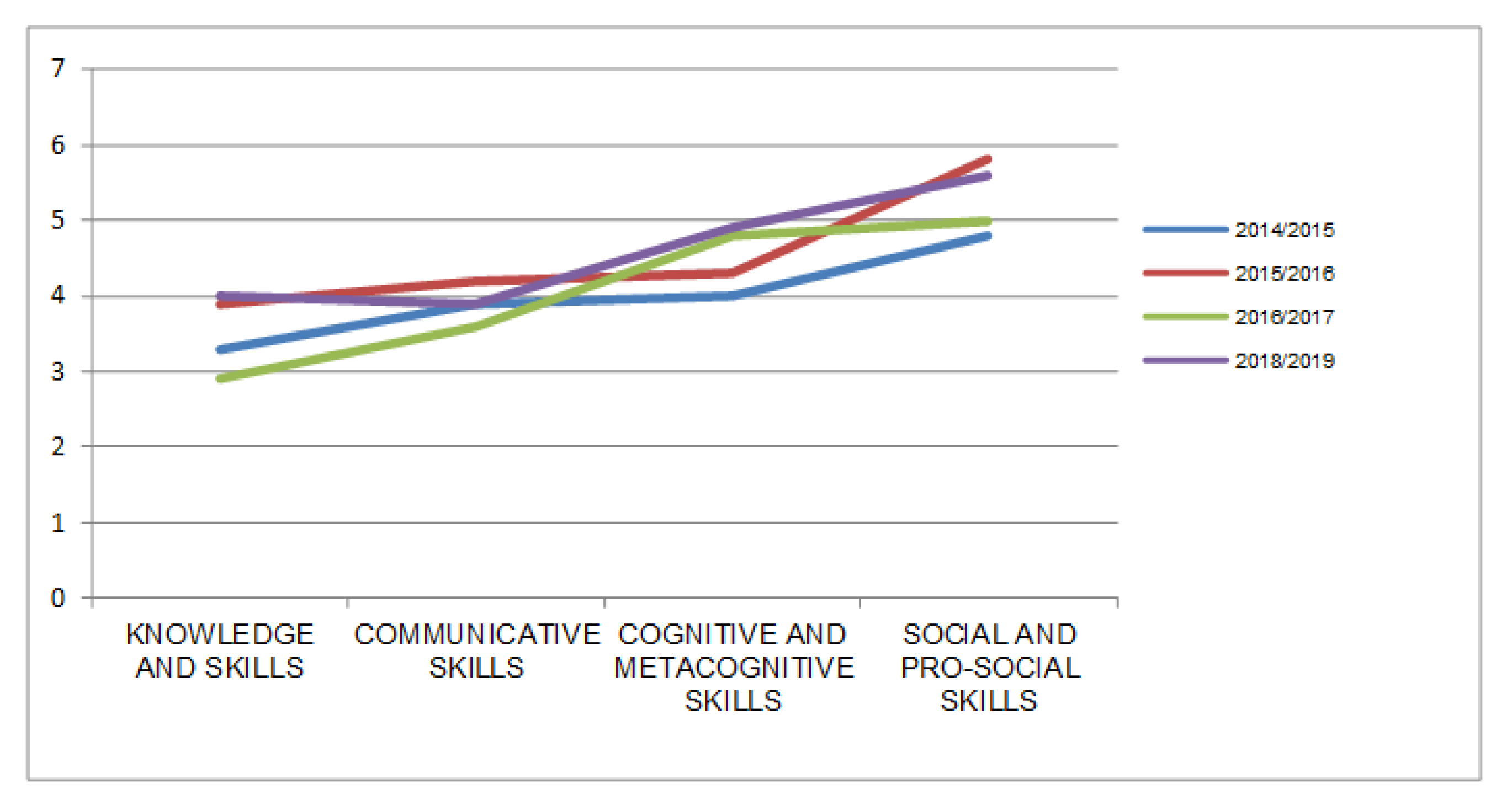

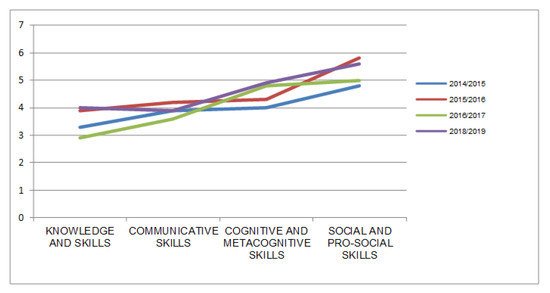

The results collected in relation to the different areas observed show an improvement (Figure 14):

Figure 14.

Trend of research data with an observation from knowledge to pro-social skills.

- -

- in medium-high knowledge and skills in problem solving for 56% of the sample and in high communication skills in interaction for 52%;

- -

- in medium-high cognitive and metacognitive skills, for voice awareness of their choices and capacity for critical analysis and process reformulation (42%)

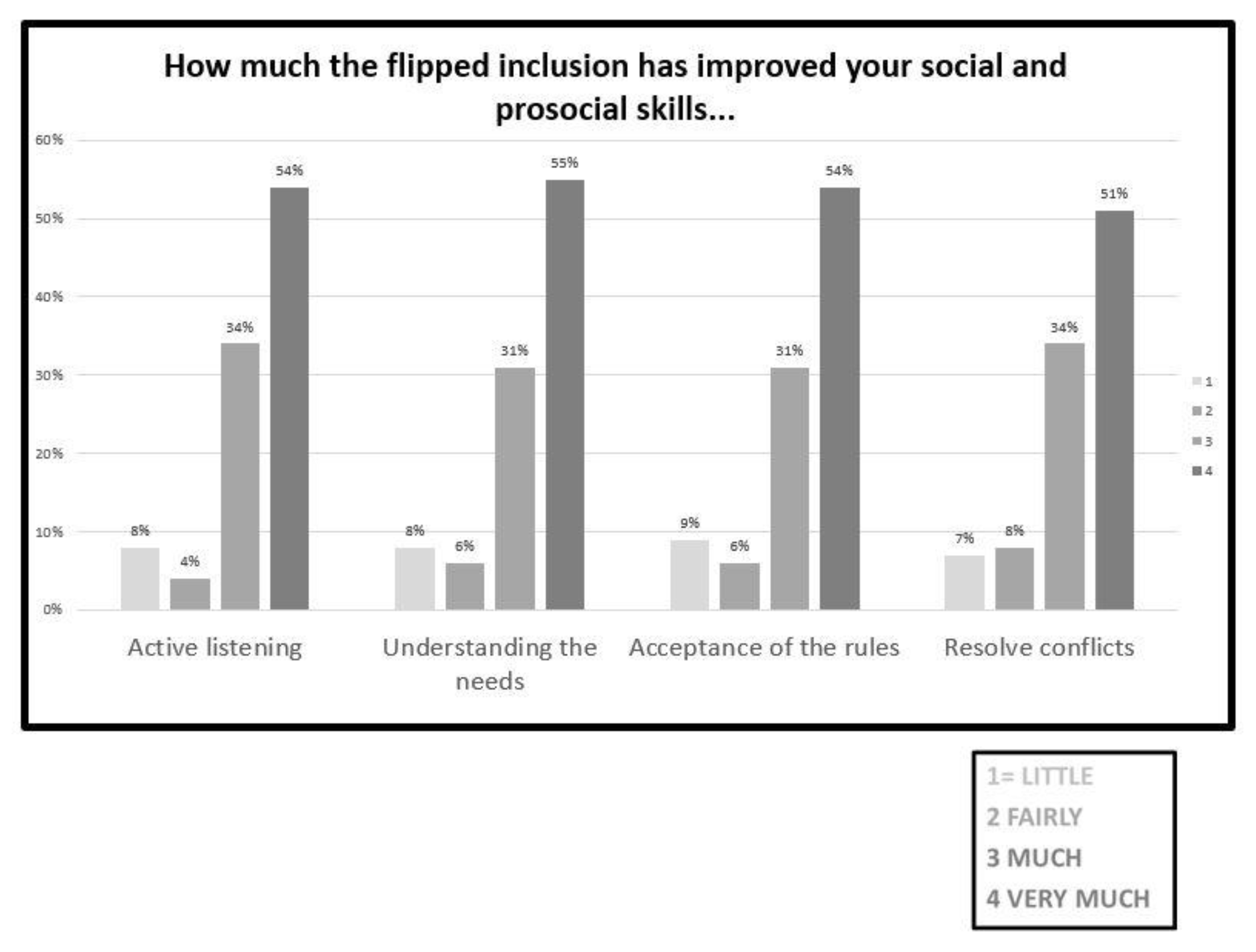

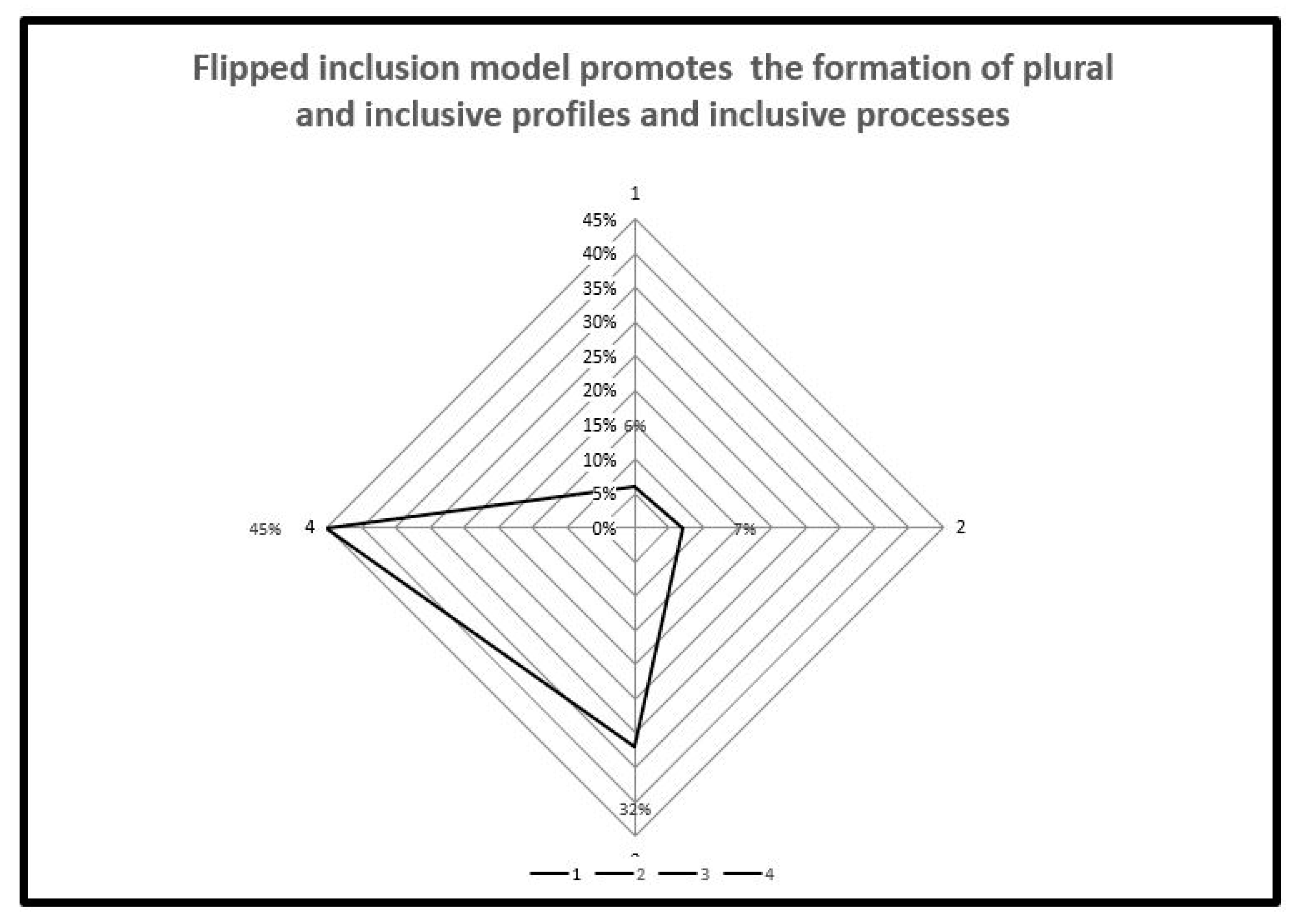

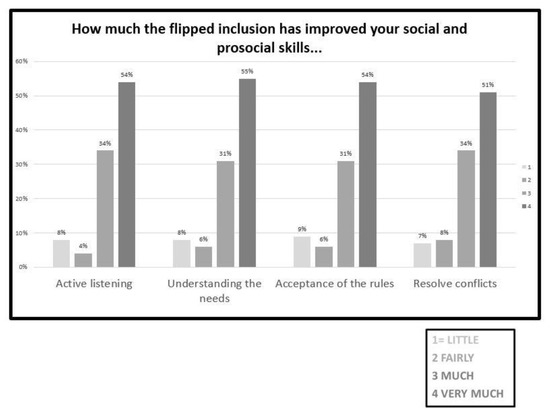

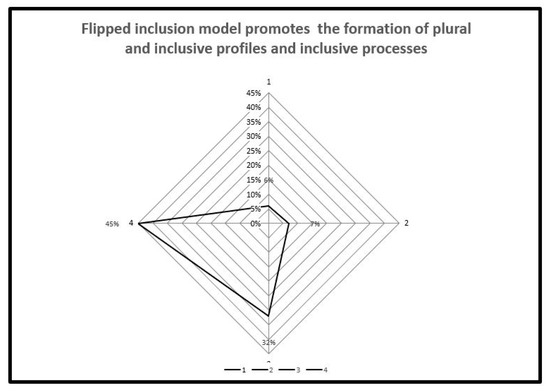

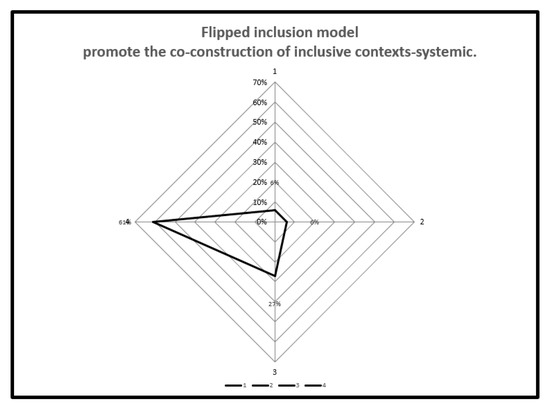

From the second research question: (flipped inclusion teaching promotes the formation of individual and collective inclusive-prosocial profiles, it emerged that 55% of the sample show a greater empathic prosocial predisposition, while the lowest percentage of the sample (4%) was found in active listening skills (Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17).

Figure 15.

Item analysis—prosocial skills [12].

Figure 16.

Percentage data—Promotion of inclusive profiles and processes [12].

Figure 17.

Percentage data—Promotion of inclusive contexts [12].

“The probabilistic value of the conclusions, which characterize the experimental educational research, taking into account the impossibility of reaching the definition of causal inferences, with the exposure of the evaluation of the result to the risks of imprecision and indeterminacy, both for the innumerable intervening variables, both due to the impossibility of a rigorous control of unpredictable dynamic phenomenal events, it has only partially allowed to reach a first evaluation of the significance of the research results. Further in-depth studies with rigorous control measures are therefore necessary” [32] (p. 230). Hence the interest/need to continue the research with studies on sampling and new fields of investigation.

3.3. Meta-Evaluation

A meta-evaluation triangulation of the data sought with the S.W.O.T. (Stregnths, Weakenesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis through constant adherence to the theoretical research framework [12].

The strengths of the flipped inclusion model were: (1) multi-method and multi-context research; (2) involvement of the formal and informal sphere; (3) systemic strengthening of the processes of dynamic-relational learning-structuring of the top-down and bottom-up didactic design, which uses the analysis of contextual frames to trace the circular, modular and recursive logic of the ecological–systemic perspective and of computational thinking.

The Weaknesses were: (1) Re-organized didactic organization was not always efficient. (2) Organization not always was structurally adequate for research, in informal and non-formal education—automatic tabulation of data in the evaluation and design forms has been prepared on the dedicated site, flippedinclusion.it. (3) Training interventions and focus groups periodically were also with the teachers of the school involved—time management was not always adequate. (4) Difficulties were in managing logistics and connections.

The Opportunities were: (1) live agitated, formal and informal spaces; (2) to experiment with co-construction of shared knowledge; (3) to experience participatory democracy in the recognition of differences; (4) to observe different perspectives and manage conflicts due to problem levels; (5) to experiment with action research, simulating, observing, participating, cooperating in synchronous and asynchronous modes.

The Threats were: (1) underestimation of the process and blinkered focus only on the product, with the risk of trivializing the pre-course; (2) unconstrainability of the intervening variables, with a consequent difficulty of pro-active involvement and activation of forms of negative modeling of some participants; (3) difficulties in managing conflicts and differences, in the presence of a lack of awareness of cooperative role rules.

The essential link between the cross-media transformation of postmodern society and the constitutive impact of the new personalities in a global system requires individual skills, capable of going towards an existential project projected towards the qualitative well-being of life. The mechanization process of life [1], with permanent evolutionary and socio–technological processes, makes the technological tools receptors and emitters of signs and language. All this highlights the strategic value of the infrastructural interconnections spread in data platforms, due to their great generative, productive and creative potential of change processes, with products with a dynamic socio-economic content that are self-determined in virtual learning contexts. The permanent re-generative virtual collective co-construction of knowledge and subcultures feeds on self-generated narrated cultures and virtual projections of sometimes idealized experiences.

The subjective co-construction of meaning by context is reaffirmed, as a process of signification, as a process of development and training, centered on the dynamic, situated and manifested human relationship: the process of producing meaning influences individual actions, beliefs and emotions.

From this perspective, learning assumes different social identities for categorical systems and for formal, non-formal and informal contexts, as an inevitable element of an integrated training system. The expansion of spatiality and learning macro-categories delineates the new theoretical-praxic context, in which democratic processes of substantial digital citizenship are activated. Since in postmodern society, therefore, there is no single, homogeneous and linear sense of episteme, from explicit rules in the construction of the sense of civilization, the new educational challenge bypasses the simple instrumental use of technologies, and is placed in the importance of inducing a critical reflection on the drawbacks and potential inherent in cross-media society.

Lifelong learning of the connectionist system [104], an expression of collective intelligence, situated and contextual, places the socio–educational value of formal, non-formal and informal learning environments as interaction plans at the center of the pedagogical debate which is negotiated but not always controllable [105]. The aim is to train for management skills and re-understanding indispensable in a constantly hyper-connected global, plural, world. The declinations of the augmented classroom-educational contexts represent the places of manifestations of development potentials, characterized by the training dialectic on subjective and intersubjective experiences.

The educational investment in the interpretation of relationships allows us to grasp the correlations between material and intangible resources, such as human capital, and to promote the processes of mobilizing subjective internal resources, so as to make them interact dialectically with the context.

This avant-garde educational approach allows the recognition of the phenomenological repercussions and the expression of the concrete communication processes at a psychological, anthropological and cultural level, which are reflected in the choices and in the social and political directions.

Through the promotion of competent self-reflexivity, it is possible to control the risks of antisocial modeling, through investments in education to self-awareness [106].

4. Conclusions

4.1. New Research Perspectives: Accessibility Tools and E-Learning Platforms for a New Experiment in Flipped Inclusion

The ergonomic–educational interventions of Flipped Inclusion, in response to the Prime Ministerial Decree of 4 March 2020 [107], containing urgent measures regarding the containment and management of the epidemiological emergency from COVID-19, were implemented through the Open and Distance Learning system [108].

The design of on-line paths of flexible personalization, accessibility of content, space-time-technology, [91], were configured as guarantors of fair-inclusive training opportunities, functional to the form–action of the Planetary Man [109], referent specific to pedagogical knowledge and educational practice.

For the creation and assessment of content accessibility, in line with ISO/IEC 40500: 2012 [93], Flipped Inclusion adopts the criteria of:

- Perceptibility: of web content and user interface, viewable from any sensory replacement device. “Provide textual alternatives for any non-text content, so that it can be transformed into other usable forms according to user needs” [110].

- Usability: the user interface components must be easily usable (functionality via keyboard, adjustment of execution times, adjustment of the target).

- Understanding: information, services and user interface operations (readability, identification–suggestions–prevention of errors)

- Robustness: content optimization for the interpretability of each software and assistive technology; compatibility with a wide variety of user programs [111].

The quick availability and inclusive accessibility of the training content is combined with the need for flexibility of the (1) training objectives; (2) educational paths; (3) evaluation criteria; (4) verification tools. The application of the ergonomic principles in Flipped Inclusion, in e-learning mode, invests in a phenomenological approach built on implementation freedom, for the self-management of self-learning [112] and self-determination, self/co-generated and regulated [113]. The cognitive–recursive computational modularity of e-learning, by promoting the reorganization and re-construction of disciplinary knowledge, overcomes the linear–temporal rigidity of cumulative-sequential thinking, to open up to the circularity of training which is “a spiral ascent (…) so that more and more touches the object of knowledge “[114] (p. 224).

The web-based context allows autonomy of the didactic-educational activities [115] for the responsibility “to selectively activate specific portions of networks, specific segments of interaction” [98] (p. 21) for the ergonomic availability and reusability of the training content. In applying the ergonomic principles in e-learning mode, we intend to subjugate the danger of the creation of non-places [99] of transitory usability, which are historically dissolvable, agnostic, devoid of identity–relational value, typical of excess time, space and ego of super-modernity [116]. In promoting co-counseling, collaboration and participation processes, Flipped Inclusion aims to activate the “third space” [117] (p. 17), an anthropological place [118] of harmonious convergence of human beings.

Through the use of Microsoft Teams [119], a multimedia technological infrastructure of communicative productivity, we invest in learning environments of reflective education, of individual cognitive growth resulting from collective-group interaction [120,121]. For both the production of design artifacts and the training process, Flipped Inclusion makes use of Microsoft Teams [122], an ergonomic–anthropocentric platform for the creation of communities of practice and learning [7], with an interesting reification, participation and social negotiation of meanings [123]. In Teams for Education, the principles of ISO [76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93] are applied in e-learning mode through the preparation of virtual classes accessible from the Uniform Resource Locator (URL) or through the invitation of users–participants (also guests), transmitted by the ‘administrator–owner’. The free suite Microsoft teams, the hub of Office 365, is intellectual partner of elaboration, fruition, sharing and access to knowledge, consisting of the main sharing of four hermeneutical tools—(1) Channels; (2) Chat; (3) Meetings; (4) Quiz [124]—transversely retracing the six design phases of the ISO 6385: 2016 [125]—which, invested in the quality of the Flipped Inclusion pedagogical project [126,127], aimed at the autonomization of prosocial-inclusive profiles.

Just as in presence and in blended mode, systemic micro- meso- exo- macro- [34] collaborative problem-solving [128] activities are proposed through Microsoft Teams, a communication tool. It invests in the collective-resolutive identification of the specific analysis of a social problem and in the evaluation of the process [129] of co-creation of co-constructed works. The ergonomic asynchrony of the network, in amplifying multiple interpretations [130], allows the individualized adaptation of cognitive rhythms and learning styles, triggering positive consequential actions, with a connotative social impact [131,132].

- The channels in Teams [133] are configured as places of conversation for the users, ergonomic organized sections divided by area, domain and object of interest. The standard channels [134], open to all members, are used by the teacher in the preparatory and executive phase:

- (1)

- To inform learners about the purposes and structure of the ergonomic micro- meso- exo- and macro-contextualized inclusive designs. It invests in the introduction of preliminary micro-warming lessons [45] in which the conceptual coordinates of the course are defined, for the conversion of an individually perceived discomfort into a problematic node to be analyzed. The teacher makes use of the ergonomic advance organizers [135], functional to the activation of reticular anchored knowledge structures, to design their lesson in a self-determined way [136]. It is a question of providing a “visual representation of knowledge, that is, a way of structuring information, or of organizing the important aspects of a concept or topic in a scheme that uses definitions” [137] (p. 6). The anticipation is stimulated with elicitation activities through brainstorming sessions [138], creative planning and problem solving techniques, capable of promoting Engagement [139], a positive psychological state of connection, involvement, active and attentive, functional participation and cognitive investment [140]. The aim is the anthropocentric enhancement of the individual, capable of bringing formal and informal knowledge to the discussion and acquiring the most hidden meanings by discovery [65], through the punctual assignment of circumscribed and self-consistent artifacts (individual project work).

- (2)

- For the feedback, a circuit process takes the form of input while awaiting output [141]. Investments are made in cognitive training feedback, in feedback phenomena relating to specific disciplinary contents, which are functional for on-going variational-corrective procedures, and in emotional insights [142] for positive, emotional-motivational reinforcement. In Flipped Inclusion the teacher, in Microsoft Teams, provides frequent and precise ergonomic correction, processes and self-evaluation feedback [143,144], through stimulus questions or shared self-reflection. Investments are made in individualized-immediate communication interventions, to make constructive adaptations to progress, supporting the learning process. Regular administration of Feedback in educational-training contexts of distance learning [145] constitutes the priority motivation lever for the qualitative improvement of performance and human potential, in a review of circular-anthropocentric progress, for the activation of a dynamic system of mutual influence. In Flipped Inclusion, the feedback action, an accelerator of cultural change, supports relational systems by regulating behavior and verification and control of communicative understanding; it promotes the acquisition of greater self-awareness, active listening and harmonious, ergonomic productive, organizational well-being.

- (3)

- For the presentation of interventions and anthropocentric enhancement of the elaborated artifacts. The individual project works, accompanied by Word files, are co-discussed in the standard channels in Microsoft Teams [146] through the use of Digital Storytelling, narrative-explanatory videos made in Adobe Spark Video. The ergonomic software application developed by Adobe Systems combines animated graphics, personalized typography, music and audio recording. The tool is configured to be intuitive, free, accessible to any desktop browser, available for Windows and macOS operating systems; it is Cloud Computing or Web Based, as it does not require software installation but can be supplied, upon request, from the internet. It can be used by mobile devices, such as smartphones and tablets, through the web. For the production of artifacts, which can also be used offline, Adobe Spark Video allows the use of diversified website templates, one-tap animations, movement effects and transitions, expressive fonts for style, shape and color; the suite allows you to create impact visuals in multiple languages for ergonomic–inclusive accessibility. The processed digital content will be shared on the website www.flippedinclusion.it, in the informal socio–cultural contexts of Facebook, Twitter and Youtube.

- (4)

- For debriefing, as a retrospective co-discussed reflection of anecdotes, thoughts, cognitions, emotional states [147]. In Flipped Inclusion, the ergonomic reverse analysis process is applied, the reconstruction of the critical–problematic nodal aspects, for the launch of new and unexplored problem settings. Formally used at the end of the significant experience, in contrast to the warming up, the semi-structured process of debriefing is configured as a group processing method to capitalize on experienced experiences through description, analysis and transference phases. Investments are made in the ergonomic reflexive review of the team members’ practices and artifactual products, “aimed at raising awareness of relational and communicative dynamics [...]; in a series of procedures that allow instilling narrative customs “[148] (p. 151), functional to decision making processes [66]. For hermeneutic circularity, the debriefing opens new scenarios, new interpretations: the reflection on the resolution given to a problem generates a further problematic question, with emotional implications, to be submitted to structured analysis.

Private channels [149], however, in the application of Flipped Inclusion in Microsoft Teams, are used to host consultation conversations in micro, and subsequently, in meso and exo groups of specific recipients. The private channels are free to access for teachers. They are used following the delineation of individual project works. They are also used for confidential discussions, the comparison of a restricted target of users co-belonging to the team and for the elaboration of ergonomic micro–meso–eso contextualized inclusive designs. The artifacts co-conceived and co-built in private channels will subsequently be co-analyzed and co-discussed in standard channels, through (1) brainstorming, (2) collection of feedback (3) presentation of the elaborated products (4) debriefing, for the delineation of a prosocial-inclusive macro-design in plenum.

- 2.

- The ergonomic Microsoft Teams used for the application of the Flipped Inclusion model, in e-learning mode, allows Chat room instant messaging functions, with a dual or group size. Through the Teams collaboration app, micro-communities of users can:

- (1)

- Start and assign a name to a group chat [150], which in Flipped Inclusion follows the identity identification, the name assumed by the individual micro- meso- exo- and macro-group to which they belong. Chats, as spaces of virtuality enlivened by authentic interaction, are marked with the name of the managing communities, to facilitate the process of mutual recognition. The asynchronic relational exchange—through the media alphabet, computer code, for the interaction dialogue of converging and divergent operational roles, of differentiation and communion—favors recognition, the sense of cohesion and self-definition, the containment of anxiety-inducing phenomena, de-identification and moral disengagement. The group–identity dimension favors the perception of individual relevance; the self-determination of the singularity within the co-inhabited community educates the sharing of a set of representations, norms and values [151].

- (2)

- Highlight the most used chats [152], using the “lock” button located at the top of the Teams app. In this way, the group conversation will remain fixed at the top of the personal messaging list. The priority iconic-identity visualization of the chat acts as a facilitating medium to stimulate the attention–memory processes of anchoring to the task to be elaborated. In this way, the chat object will be memorized-remembered and used quickly for future needs, since it is learned from the concrete to the abstract and the visual symbols precede the verbal ones [153].

- (3)

- Share files [154], co-view and co-edit Word documents, co-create diagrams and graphs with Visio, upload Adobe Spark multimedia videos through the ergonomic SharePoint Online software in the cloud, functional for the shared management of cognitive content. The use of SharePoint, the online Content Management System (CMS) platform, in Teams, provides a web hosting service, supports the productivity and efficiency of micro- meso- exo- and macro team-working [155]; it facilitates the coordination and divided organization of tasks, the acquisition of anthropocentric [43] soft skills, a cluster of transversal skills relating to the personal qualities of the relational Being [83] for the educational-integral formation of the Social Person [156]. Once completed, the artifacts shared and co-processed in chat are individually archived in the ergonomic OneDrive for Business, a private-encrypted personal repository, a guarantor of security and privacy.

- (4)

- Select the amount of chat history to include [102]. The e-learning application of the Flipped Inclusion in Teams model invests in the complete chronological saving of chats, an effective ergonomic tool for recursive retention, a graphic display of the historical reconstruction of the educational and metacognitive process experienced. This chrono-dialogic documentation is configured as a “meaning attribution device” [157] (p. 67), an instrument for the evolutionary detection of the didactic phenomenon, co-acted in a condition of temporal simultaneity [158]. The chronology-chat, as a qualitative approach to knowledge, allows the temporal reporting of the communicative-media sociality process for the “conversion of narration into training” [159] (p. 121), mediated by meta-reflective and self- analysis evaluation of the shared practice.

Teams chats [160] allow virtual micro- meso- exo- and macro-communities to: (1) Send free read confirmations of receipt; (2) Instantly translate the e-learning message thread, a guarantor of multilingual accessibility; (3) Activate Immersive Reader, an ergonomic tool for immersive reading, inclusive learning, accessibility of cognitive contents. Functional to the readability, comprehension and decoding of the texts, the text-to-speech (read aloud) technology is configured as a tool for satisfying the distinctive-individualized special educational needs of the individual team members (it is particularly functional for diagnosing disorders with impaired reading and written expression [161]; (4) Send priority notifications.

- 3.

- Meetings [162]. The application of Flipped Inclusion in Microsoft Teams allows:

- (1)

- For members of standard and private channels, the launch of operational meetings and immediate live meetings, for timely micro- meso- exo- and macro-group communications, and the synchronization of scheduled meetings, established as agreed in advance. The ability in Teams to activate ergonomic subtitles in real time facilitates accessibility to the process of co-construction of the artifacts, multimedia content and reciprocity of intent co-discussed in the meeting. The simultaneous, self-generated caption on the platform, for the textual visualization of the verbal (semantic), non-verbal (emotionality) and para-verbal (paralinguistic system) component, is a guarantee of didactic-inclusive perceptibility. The accessible design of Microsoft Teams allows the activation of intra-interlingual subtitles (in 60 different languages) for the removal, in team building meetings, of the linguistic–architectural barriers [28]. The synchrony of visual–audio–textual digital elements improves the levels of sustained attention, for greater understanding [163] of the co-discussed content, in the anthropocentric enhancement of the Person [83] (regardless of the presence of special educational needs, of sensory disabilities or neurodevelopmental disorders) [164].

- (2)

- To preserve the productive and inclusive accessibility of the meeting, the ergonomics of the Teams platform, thanks to the interactive problem solving [67], signals the members of the micro- meso- exo- and macro-groups of the hypothetical deactivation of the microphone and/or video, when they are about to co-participate in the community dialogue. In addition, by invitation from an e-mail address and the generation of the “Join Microsoft Teams Meeting” link, in Teams the audio and/or video-conferencing meetings can be extended to include the participation of external users in the organization of private and standard channels. The management of the predefined meeting criteria [165], for the privacy of distance learning, allowed the personalization of the control of the functionalities available for the participants, through the adoption of security restrictions in the acceptance–admission of the participants from the virtual lobby-hall.

- (3)

- Sharing content [166]. In Microsoft Teams the micro- meso- exo- and macro-groups have the possibility of sharing their screen in meetings (desktop/windows/power point/blackboard) [167] and system audio; grant and/or take control of the shared screen to allow instant modification of the files. Screen sharing, a cognitive–visual interface [168], facilitates remote communication, management and sharing of ergonomic organizational knowledge [169], relating to the collaborative interaction of an operational-interdependent social network of relationally productive individuals. By applying the Flipped Inclusion model, the immediate sharing and correction of cognitive content aims to favor the interactive role of members in Teams, the remote (online) socialization of cognitive processes; through alternative forms of communication, thought becomes collective [170] and connective [171], as a result of the “synergy of skills, resources and projects, of the dynamic constitution and conservation of common memories, of the activation of flexible and transversal ways of cooperation” [172] (p. 50). Flipped Inclusion in Teams invests, also through the possibility of control, sharing and modification of the screened works, in the ergonomic enhancement of human relationships, in the interconnection of cooperative feelings of collective intellectuals [173]. The aim is to promote the group social nature, capable of mobilizing skills [174], amplifying intelligence and personal memory, “an intelligence distributed everywhere, continuously coordinated in real time” [39] (p. 34), for the creation of prototypes and collective-reticular mentalities, since “nobody knows everything, everyone knows something: the totality of knowledge resides in humanity” [39] (p. 34).

- (4)

- Cloud registration [174]. The application in Microsoft Teams of the Flipped Inclusion model makes it possible to acquire the entire ecological–systemic [34], interactive located [175] process carried out (from the needs analysis to the assessment), through transformative ergonomic educational cloud recordings. By systematically observing the video recordings stored in Teams, we invest in the phenomenological analysis [176] of the didactic practices [177] embodied, to activate processes of collective intersubjective confrontation, with a view to building inclusive–reflective identity profiles. The video recording [178] of the activities, in allowing the deferred objectification of the lived experience, through self-observation and psychological distancing, contributes to the systematic recovery of variables previously not considered [179] and their collection for subsequent cross-self-comparison [180]. In documenting group dynamics, interaction processes [181], gaze direction, facial mimics, body posture and movements, plural [182] and personal actions, one invests in evidence-based video-self-modeling techniques, [183] in self-learning by imitation of positive conduct, and adequate self-control strategies. The analysis of group dynamics, carried out through self-observation of video recordings, aims to introduce and automate gradual behavioral changes, to activate vicariant learning [184], processes of recognition, reflection and self-awareness. The choral examination of the high amount of segmented details observed allows us to broaden perspectives of personal meaning, in view of new cognitive, global, prosocial re-compositions [185].

In adopting non-evaluative postures, aimed at self-understanding, Flipped Inclusion invests in self-managed training through psycho-transformational self-observation exercises, video-counseling as an ergonomic-anthropocentric instrument of autonomy education [186] and a propulsor of proactive-proactive attitudes. The cloud video recordings in Teams support learning [185], for the facilitation of the processes of attention, retention, motivation [176], the democratization of knowledge, for the combination of different symbolic–cultural systems that stimulate introspection, involvement and community participation, respecting personal cognitive styles and rhythms. Flipped Inclusion invests in self-observation as self-regulation, for the structuring of re-generated maieutic personalities, problem solvers capable of modifying reality, with a view to the principle of Heisembergerian uncertainty [153] (to change a phenomenon it is necessary to observe it).

- (5)

- Initiate calls [102]. The ergonomic Microsoft Teams supports general telephone network (PSTN) conferences by allowing members of the micro- meso- eso- macro-groups to access meetings from an external telephone number. In case of Wireless Fidelity (Wi-Fi) connection problems, the audio-conference service acts as a safeguard to ensure “the didactic performance in remote modes, using available IT or technological tools, IT equipment and telephone connections and telematics, to contain any spread of the infection “[89]. In this regard, the use of the Flipped Inclusion mobile app for Android (Figure 18), which can be downloaded free of charge from the Google Play Store digital distribution service, is also a valid vicarious ergonomic–anthropocentric support tool [49], to any interruptions of access in Teams. A versatile, simple, intuitive teaching assistant [28], it is functional for the graphic, active representation of the conceptual contents of the theoretical Flipped Inclusion system, expressed in synthetic form. It is an educational–digital resource useful for the schematic, organization and syntactic-lexical reformulation of the course, functional for supporting, integrating and reinforcing the user’s learning from their device.

Figure 18. Graphical interface of the Flipped Inclusion App.

Figure 18. Graphical interface of the Flipped Inclusion App.

- 4

- Quiz [102]. For docimological evaluation, Flipped Inclusion, in its remote application in Microsoft Teams, the ergonomic–anthropocentric Microsoft Forms Office 365 App for the personalized creation of surveys, tests and online quizzes with automatic marking is being launched [102]. Usable in a web browser, for the ongoing use of participants’ satisfaction and for the collection of in-quiz feedback (automatic-individualized feedback provided for immediate upgrade), it is configured as a valid upside-down learning tool [45], with the possibility of structuring logic-trees of questions with threaded branching [154] on a likert or ranking scale. Using the Microsoft Forms in Teams application, users fill in the individual synoptic project evaluation (monitoring) and self-assessment (processing), micro- meso- exo- and macro-group forms, corresponding to rubric (1) knowledge and skills (2) communication skills (3) cognitive and metacognitive skills (4) social and pro-social skills (Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8). In this regard, we invest in a transdisciplinary, non-judgmental, authentic formative evaluation [155], an integrated part of the same educational action [156], in a meta-competitive approach [157] with different degrees of structuring, in a qualitative–quantitative balance [158] of digital methodologies and tools, for the multiplicity of procedural, contextual, individual, participatory–collaborative aspects, to be monitored, certified and checked [159].

The design of the app (Figure 19), currently being tested, naturally followed the assessment provided by the model, according to the structure organized by levels of increasing difficulty (from knowledge to prosocial skills) in compliance with the provisions of the flipped inclusion model.

Figure 19.

Examples of evaluation rubrics for Flipped Inclusion in Microsoft Teams with the Office Forms App.

The teacher has the ability to share the assessment rubrics in Microsoft Forms [170] through a Code Generator (QR), by sending participants the link of the form via a Uniform Resource Locator (URL), by email or via the web, or by using the “Activities” function in Microsoft Teams, to assign the Flipped Inclusion synoptic-design sheets directly from the platform. In Forms, the assessment can be completed using personal computers, smartphones and tablets.