The Nature of Employee–Organization Relationships at Polish Universities under Pandemic Conditions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Manager–Employee Relations

2.2. Employee–Employee Relations

2.3. Remote Working

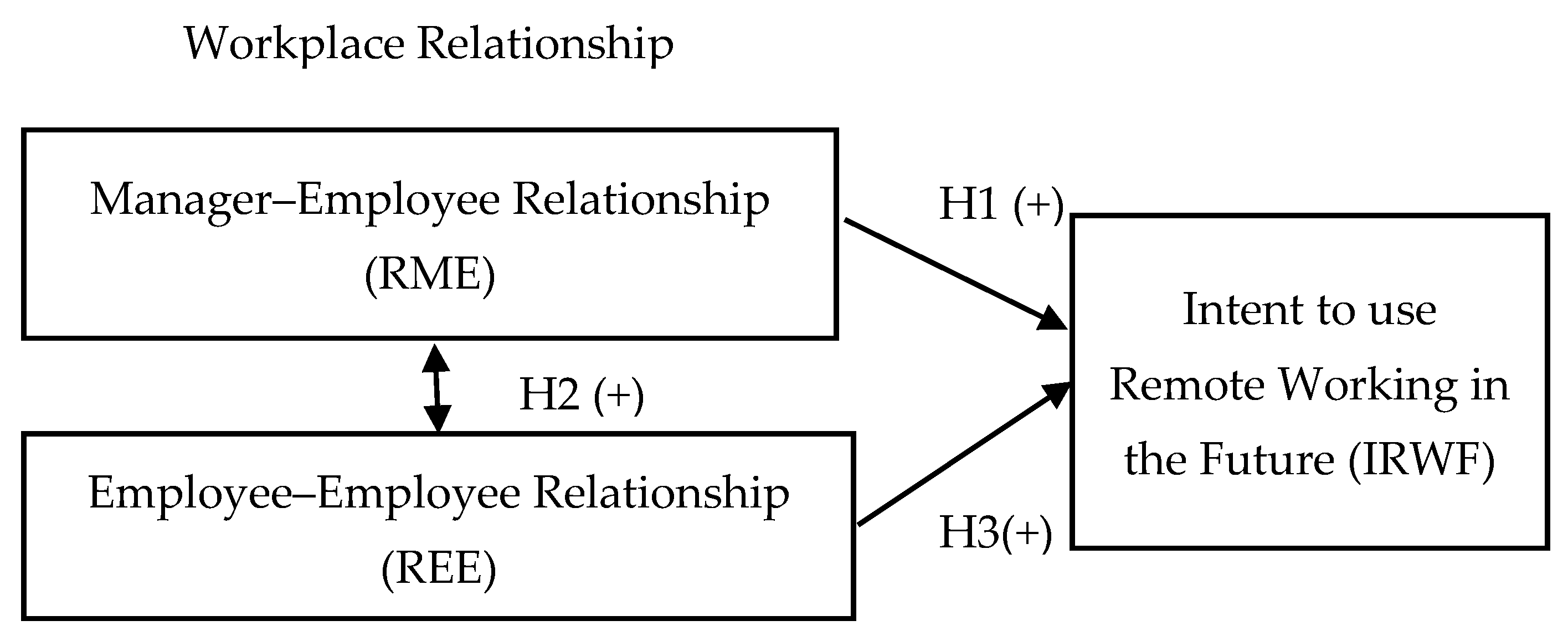

Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Description of Sample

3.2. Instrument of Data Collection

3.3. Measurement Scales

4. Results

4.1. Details of the Results

4.2. Summary of Hypothesis Tests

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Limitations

6.2. Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Katsoulakos, T.; Katsoulacos, Y. Integrating corporate responsibility principles and stakeholder approaches into mainstream strategy: A stakeholder-oriented and integrative strategic management framework. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2007, 7, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, F.; Morris, T.; Young, B. The Effect of Corporate Visibility on Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perrini, F.; Costanzo, L.A.; Karatas-Ozkan, M. Measuring impact and creating change: A comparison of the main methods for social enterprises. Corp. Gov. 2020, 21, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, J.W.; Brightman, B.K. Leading organizational change. J. Work. Learn. 2000, 12, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J. The Theory and Practice of Change Management; Palgrave: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://books.google.pl/books?id=sbZIDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Dyer, J.H.; Singh, H. The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 660–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lavie, D. The competitive advantage of interconnected firms: An extension of the resource-based view. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 638–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.; Foerster, S.; Li, Z.; Tang, Z. Analyst talent, information, and insider trading. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 67, 101803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.; Marques, A.V.; Braga, V.; Ratten, V. Technological transfer and spillovers within the RIS3 entrepreneurial ecosystems: A quadruple helix approach. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pr. 2021, 19, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, A.S.; Pearce, J.L.; Porter, L.W.; Hite, J.P. Choice of Employee-Organization Relationship: Influence Of External And Internal Organizational Factors. Res. Pers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1995, 13, 117–151. [Google Scholar]

- Xesha, D.; Iwu, C.G.; Slabbert, A.; Nduna, J. The Impact of Employer-Employee Relationships on Business Growth. J. Econ. 2014, 5, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, I. Perceptions of Employee Relations Programs (ERPs) by Non-Managerial Employees (NMEs): A Study on the Pharmaceutical Industry in Bangladesh. South Asian J. Manag. 2017, 24, 92–115. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, E.W.; Robinson, S.L. When employees feel betrayed: A model of how psychological contract violation develops. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 226–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D.M. Psychological and implied contracts in organizations. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 1989, 2, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abun, D.; Magallanes, T.; Agoot, F.; Paynaen, E.P. Measuring Workplace Relationship And Job Satisfaction Of Divine Word Colleges’ Employees in Ilocos Region. Int. J. Curr. Res. 2018, 10, 75279–75286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shraddha, P.; Chandak, S.R. A study on Implementation of Employee Relations & Talent Management Practices at Indian Information Technology Companies. Int. J. Glob. Manag. 2014, 5, 10–26. [Google Scholar]

- The Importance of a Strong Employer/Employee Relationship. Nesco Resour. Available online: https://nescoresource.com/blogs/details/the-importance-of-a-strong-employeremployee-relationship/99/ (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Bakotić, D. Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Organisational Performance. Econ. Res. Istraživanja 2016, 29, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle-Shapiro, J.A.-M.; Shore, L.M. The employee–organization relationship: Where do we go from here? Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2007, 17, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seers, A. Team-member exchange quality: A new construct for role-making research. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1989, 43, 118–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raziq, A.; Maulabakhsh, R. Impact of Working Environment on Job Satisfaction. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 23, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhigg, C. What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team. New York Times. 2016. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/28/magazine/what-google-learned-from-its-quest-to-build-the-perfect-team.html (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- EY Polska. Raport EY: Cała Polska Tworzy Idealne Miejsce Pracy. 2020. Available online: https://www.ey.com/pl_pl/raporty-analizy/cala-polska-tworzy-idealne-miejsce-pracy (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Nyaanga, S.G. The Impact of Telecommuting Intensity on Employee Perception Outcomes: Job Satisfaction, Productivity, and Organizational Commitment; ProQuest Publication: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2012; Available online: http://gateway.proquest.com/openurl?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:dissertation&res_dat=xri:pqm&rft_dat=xri:pqdiss:3557296%5Cnhttp://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=psyc11&NEWS=N&AN=2014-99030-010 (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- Collins, F.B.R.W. Distributed Work Arrangements: A Research Framework. Inf. Soc. 1998, 14, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dolot, A. Raport z Badania Dotyczącego Pracy Zdalnej w Czasie Pandemii Covid-19. Published Online First: 2020. Available online: http://docplayer.pl/200627216-Raport-z-badania-dotyczacego-pracy-zdalnej-w-czasie-pandemii-covid-19-krakow-kwiecien-2020-anna-dolot.html (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- Concept Intelligence. Raport Praca Zdalna. 2020. Available online: https://harmonyteam.pl/raport-praca-zdalna/ (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- Cekuls, A.; Malmane, E.; Bluzmanis, J. The Impact of Remote Work Intensity on Perceived Work-Related Outcomes in ICT Sector in Latvia. New Chall. Econ. Bus. Dev. 2017, 96, 96–107. [Google Scholar]

- Dubrin, A.J. Comparison of the Job Satisfaction and Productivity of Telecommuters versus in-House Employees: A Research Note on Work in Progress. Psychol. Rep. 1991, 68, 1223–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sias, P.M. Workplace Relationship Quality and Employee Information Experiences. Commun. Stud. 2005, 56, 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, S.; Sanders, K.; Bednall, T.; Bednall, T. Employee perceptions of management relations as influences on job satisfaction and quit intentions. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2012, 30, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, T.D. The role of relationships in understanding telecommuter satisfaction. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, S.J.; Shore, L.M.; Liden, R.C. Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: A social exchange perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 82–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Manager–Employee Relations | RME | REE | IRWF | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My immediate superior supported me in planning remote working | 0.956 | 2.98 | 2.061 | ||

| My immediate superior supported me in organizing remote working | 0.955 | 2.92 | 2.037 | ||

| My immediate superior oversees my remote working | 0.635 | 3.45 | 2.091 | ||

| My immediate superior collects information on my problems and needs in remote working | 0.749 | 3.00 | 2.021 | ||

| My immediate superior evaluates my remote work | 0.659 | 3.38 | 1.947 | ||

| My immediate superior informs me of the evaluation of my remote work | 0.659 | 2.46 | 1.650 | ||

| My immediate superior motivates me to work remotely | 0.727 | 3.06 | 2.075 | ||

| Employee–Employee Relations | |||||

| My colleagues support me in remote working | 0.849 | 4.40 | 1.974 | ||

| My colleagues are more flexible than in traditional conditions | 0.712 | 4.04 | 1.792 | ||

| My colleagues are willing to share knowledge | 0.789 | 4.92 | 1.767 | ||

| Intent to Use Remote Working in the Future | |||||

| I intend to use remote working in the future as an element complementing my traditional form of work | 0.879 | 5.58 | 1.538 | ||

| I expect the experience of remote working to be useful in my professional life | 0.945 | 5.80 | 1.502 | ||

| The use of remote working tools in the future will enable me to perform my work duties more quickly | 0.925 | 4.96 | 1.695 | ||

| The use of remote working tools in the future will increase my productivity | 0.652 | 4.74 | 1.778 | ||

| The use of remote working tools in the future will improve the quality of my work | 0.666 | 4.88 | 1.705 |

| Construct | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE | Mean | Std. Deviation | Correlation Coefficients | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RME | REE | IRWF | ||||||

| RME | 0.902 | 0.875 | 0.546 | 3.035 | 1.579 | 0.739 a | ||

| REE | 0.823 | 0.828 | 0.617 | 4.453 | 1.587 | 0.368 | 0.785 a | |

| IRWF | 0.917 | 0.911 | 0.618 | 5.193 | 1.426 | 0.205 | 0.383 | 0.786 a |

| Relations | B | S.E. | t | p | β | Sing | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRWF | ← | REE | 0.318 | 0.039 | 8.060 | *** | 0.355 | + | Supported |

| IRWF | ← | RME | 0.057 | 0.030 | 1.870 | 0.062 | 0.074 | Not supported | |

| RME | ↔ | REE | 1.214 | 0.146 | 8.322 | *** | 0.368 | + | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Staniec, I. The Nature of Employee–Organization Relationships at Polish Universities under Pandemic Conditions. Information 2021, 12, 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12040174

Staniec I. The Nature of Employee–Organization Relationships at Polish Universities under Pandemic Conditions. Information. 2021; 12(4):174. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12040174

Chicago/Turabian StyleStaniec, Iwona. 2021. "The Nature of Employee–Organization Relationships at Polish Universities under Pandemic Conditions" Information 12, no. 4: 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12040174

APA StyleStaniec, I. (2021). The Nature of Employee–Organization Relationships at Polish Universities under Pandemic Conditions. Information, 12(4), 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12040174