1. Introduction

The cultural heritage (CH) sector has always acted as catalyst in allowing groups to coexist harmonically by investing in cultural diversity and intercultural dialogue. However, the vast majority of the cultural experiences offered by cultural institutions are designed to address the mainstream audience and rarely take provisions to make these experiences inclusive for groups with diverse sociocultural characteristics. Inclusiveness and social cohesion may be hindered by a number of factors ranging from poverty and cultural misalignment between visitors and the provided experience to experiences insufficiently targeted to attract diverse audiences. Excluded sociocultural groups are not attracted in cultural institutions per se, because their cultural interests are not sufficiently reflected in or connected to the offered experiences. Making them co-creators of the offered museum cultural experience could increase their interest and foster their cultural inclusion and cohesion with the rest of the society. When people can actively participate in cultural institutions, these places become central to the cultural and community life. Similarly, cultural institutions can reconnect with the public by inviting visitors to actively participate not as passive consumers, but as contributors to the offered experiences.

Nowadays, the Social Web has ushered in a varying set of Web 2.0 tools and design patterns that make public’s participation more accessible than ever. Visitors expect the ability to discuss, share, and remix what they consume, becoming more and more accustomed to participatory learning experiences. Specifically, the current information revolution requires the adoption of learning models that cultivate skills such as creative and critical thinking, reflection, and collaboration. However, the adoption of the Web 2.0 philosophy is understandably not a simple matter to approach for museums, as it requires the establishment of a delicate balance between different priorities. In addition, although learning theories that take into account the social and active nature of learning have gained authority among educators, in most cases, learning in museum settings still largely remains a top-down activity up to this point. Therefore, the adoption of Web 2.0 principles should not be viewed as a kind of panacea in the museum sphere. Instead, museum specialists should pursue a cautious re-examination of current practices in order to carefully redefine their relationship with their audience. In this context, the ongoing research of both successful and unsuccessful cases of Web 2.0 museum practices is of great importance, studying the matter of how visitors can be engaged in cultural learning processes where identity can be shaped, merging both the domains of individuality and collective cohesion.

In this context, in order to increase the democratization of culture and wider participation, while at the same time respecting museums’ authority and identity, this paper proposes the design and development of an efficient technology-based solution that could facilitate the creation of an online learning community for curators and museum visitors. Its main aim is to facilitate the sharing and discussing of cultural experiences and information, and many other types of interactions among them. Thus, the ability of these individuals to reflect and connect with the cultural offerings could be restored by engaging in a process of collective learning in a shared domain of cultural endeavor. In more detail, the scope of this research work is to provide a user-friendly tool where curators can offer expert commentaries on artifacts, follow and monitor visitors’ activity, and interact with them. On the other hand, the proposed application could also be used by visitors as an interactive self-guided tour tool with augmented reality (AR) features for exploring museum exhibitions, encouraging them at the same time to adopt an active role through interaction with other visitors, content sharing, and feedback provision. Therefore, the AR-enhanced exhibition navigation screen is considered the core of the ARtful mobile application. The sharing of cultural learning episodes aims to enhance awareness, participation, and contribution of new cultural material for visitors, and enable cultural institutions to expose their audience to diverse cultural content, aggregated to through the continuous passing of visitors. Taking into consideration the propositions of modern social learning theories and the state-of-the-art analysis, the main aim of this study is to test the hypothesis that the educational use of such a social media tool could help museums transform into more democratizing, inclusive, and polyphonic spaces by enhancing knowledge sharing, social learning, reflection, and knowledge assessment attitudes.

To evaluate the proposed approach, a preliminary small-scaled experiment was conducted in an AR-enhanced art exhibition to test the educational potential and effectiveness of the developed application. In more detail, in order to assess the perceived quality of the proposed app, a questionnaire was used for evaluating cognitive, emotional, and behavioral elements of the participants’ attitudes toward the use of the proposed app as a self-guided tour tool and its potential to enhance further cultural learning and social interactions among the audience. Specifically, the structure of this study is organized as follows:

Section 2 elaborates on the introduction of educational theories in the field of museum education, focusing mainly on the impact and principles of more radical educational theories, such as social Constructivism, Communities of Practice, and Connectivism, which highlight the social and active nature of learning;

Section 3 summarizes the current state of the art by reviewing related research works with respect to the creation of inclusive cultural experiences in the CH sector;

Section 4 presents in detail the functionalities of the proposed tool; that it was designed and developed in the form of a social media mobile application;

Section 5 presents the methodology adopted for evaluating the proposed application’s efficacy and the analysis of the experimental results;

Section 6 concludes the work and discusses future work.

2. Theoretical Framework

The current study focuses on the specialized educational field of museum education that conceives museums as important educational environments with a unique learning potential. In more detail, it studies the development of the educational role of non-formal education spaces and institutions, such as museums, that provide the potential for experimentation by listening and adapting to public’s needs, in order to offer richer learning experiences. These learning experiences not only help the process of cognitive information, but also aim to enhance visitors’ skills (e.g., critical thinking, self-knowledge, self-regulation, etc.). According to Philip Coombs [

1], non-formal education has the potential to satisfy the learning demands of both individuals and collectivities. Unlike formal education, that is rigid with its rules and programs, it is flexible and considers local diversities of culture and society.

In the past, museum education practices and research have been challenged by abstract terms’ confusing use and the absence of agreement on the definition of appropriate educational goals and expected outcomes, due to the lack of a coherent approach towards the use of educational theories in the museum space, a key factor in understanding how modern museum’s educational strategy and operation are closely interconnected. George Hein’s [

2] analysis helped the establishment of a theoretical base for museum education that encourages learning of all kinds—changes in an individual’s knowledge, skills, attitudes, beliefs, feelings, and concepts. His vision regarding the educational character of museums acted as a trigger for the introduction of new educational theories, which adopt a holistic approach to education. Therefore, George Hein’s work on educational theories and their relationship to museum educational practice is still a point of reference today. George Hein’s choice analysis also confirmed that there are no strict divisions between educational theories of learning and knowledge, which essentially means that multiple educational approaches can coexist in the museum space and practices.

In this context, this section presents the selected learning theories whose key principles provided both direction and impetus to the following design process and research inquiry. Specifically,

Section 2.1 briefly presents the learning theory of Constructivism. Next,

Section 2.2 describes Lev Vygotsky’s learning theory of social Constructivism, highlighting the effect of social interactions in the enhancement of knowledge acquisition. Following this, in

Section 2.3, the key features of the Communities of Practice (CoP) learning theory are defined, as well as their role in the definition of learning as a trajectory into a community process.

Section 2.4 studies the connection between Web 2.0 tools and the learning theory of Connectivism, and their impact in learning. Last but not least,

Section 2.5 concludes the current section.

2.4. Web 2.0 Connection to Connectivism and Its Impact in Learning

Virtual communities offer the ability to combine modern and asynchronous communication, increasing the number of learner–educator and learner–learner interactions [

13,

14,

15]. In this study, the Web 2.0 term is used from a learning perspective and not a technological one, and it refers to websites and applications that make use of user-generated content for end users. It reflects the new age of the internet, which puts greater emphasis on social networking, cloud computing, higher participation levels and sharing information between internet users, and collaboration [

16]. Web 2.0 technologies allow users to be social producers, rather than just consumers, while their active participation enhances the tools through their use in return.

There is a rather rich body of research reporting that the introduction of Web 2.0 in learning has significant potential to support and enhance learners’ overall learning [

15,

17]. Learners using Web 2.0 technologies are currently able to participate directly in the creation, refinement, and distribution of shared content, in contrast to being merely passive receivers of information [

18]. Web 2.0 tools make knowledge decentralized, accessible, and co-constructed by and among a broad base of participants [

19]. In addition, they empower the sense of belonging in a learning community [

13] and enhance the quality of the collaboration by stimulating new modes of enquiry, knowledge creation, and sharing [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Studies also suggest that the use of Web 2.0 tools seem to enhance learners’ engagement, confidence, autonomy, and motivation [

20,

21,

22]. Furthermore, Web 2.0 enabled learners to become information evaluators as opposed to passive learners who merely reflect their instructor‘s knowledge [

23]. As evaluators, they are encouraged to think critically about the information and actively engage in its evaluation by providing feedback. Finally, participants tend to develop a sense of ownership [

20] that motivates them to produce quality work [

24]. This process is closely connected with the shaping of their identity within virtual learning spaces and how fellow members perceive them.

However, it is of special importance that the value of Web 2.0 should not be exaggerated, because the crucial matter is how such practices can be incorporated organically and effectively into the learning process [

25]. Therefore, with this new generation of learners, who are using the Internet as part of their daily lives and are growing less and less satisfied with being passive users, pedagogical approaches need to adapt. The learning theory of Connectivism was conceived as an answer to the belief that there was a need for a learning theory that took into account the manner in which society has changed due to rapid digital technology advancement. Connectivism, introduced by George Siemens [

26], pulls together the understanding of learning with and into the Web, meaning that the efficient use of Web 2.0 technologies is the key to the Connectivist pedagogical practice. Connectivism argues that learning (defined as actionable knowledge) can reside outside of people (e.g., within an organization or a database), and focuses on connecting specialized information sets. In more detail, learning becomes a process of connecting specialized information sets, and the connections that enable us to learn more are more important than our current state of knowing [

26]. The acquisition of new knowledge is established when connections between ideas and perspectives are made, with technology having a key role in facilitating the connections necessary for learning to occur [

27]. Such connections enable learners to acquire more knowledge. The ability to draw distinctions between important and unimportant information is also vital. Connectivism’s key principles are summarized [

26] as below:

Learning is enhanced by opinion diversity and is a process of connecting specialized nodes or information sources;

Learning and knowledge may reside in non-human appliances, and currency (accurate, up-to-date knowledge) is the purpose of all Connectivist learning activities;

Developing and maintaining connections is needed to facilitate continual learning;

Capacity to know more is more critical than what is currently known;

Self-regulation and decision making in the learning process is vital. Choosing what to learn and the meaning of incoming information is seen through the lens of a shifting reality.

As it is understood, the fundamental insight offered by Connectivism concerns learners’ ability to construct their own chosen social networks that act as personal learning environments, fostering and sustaining the flow of knowledge and information.

3. Related Literature and Studies

Museums have long invested in digital forms of presence, as proved by the numerous virtual museums and on-line exhibitions [

28]. However, such paradigms are based mostly on top-down practices with very little input sought from visitors. The rise in Web 2.0 and social media tools offers the possibility for the public, on the contrary, to become engaged, to make the museum offer their own, or even to produce and share content, rejecting vertical hierarchical structures. The current section presents a state-of-the-art analysis regarding recent research works that study how and to what degree the integration of Web 2.0 principles from a learning perspective [

29] is managed by museums, along with the question of how their practices, their role, and their relationship with their audience is influenced by such a shift in paradigm.

Social learning practices can contribute to the transformation of the museum from a space where there are just exhibits on display to a place of interaction between citizens and society, where meaning and connective knowledge is constructed through a collective and social process [

30]. Specifically, cultural institutions are often considered a medium where emerging social issues of various social groups can be discussed. Therefore, their role should not be limited to the conservation of objects; memory must not only be preserved, but also relived through processes that enable its preservation and its process [

30]. In this case, cultural institutions have to face the issue of integration not only of the material culture, but also of their oral history into the framework of CH experiences [

31]. Material culture and oral history can be related through personal or collective memories and views. Artifacts are related to autobiographies and storytelling because of the meaning and the resonance they hold with a person’s memory.

Lois Silverman [

32] supported the idea that museum visitors construct deeply personalized (or very detached) meanings from the explicit content of an exhibition. Therefore, the collection of oral history testimonies should not be restricted to specific target groups. On the contrary, a wide range of diverse views can shape a more complete representation of the information plurality concerning a certain artifact. Particularly, views of marginalized groups are often neglected by society due to the problem of “othering”. In more detail, one’s identity constituted the beliefs, values, qualities, and expressions within which they are trained, constructing the sense of self and how they perceive themselves. At the same time, our identity also creates the idea of the constitutive “Other” and how we perceive the other people, according to our similarities and dissimilarities with them. John Powell and Stephen Menendia [

33] suggest pluralism and multiculturalism as an answer to the issue of othering, which could provide space for not only acceptance or diversity, but also for the recreation of new inclusive narratives, identities, and structures. Museums and cultural institutions in modern societies can act as agents of cultural understanding by mirroring diversity and tolerance, and by calling to actions that increase social cohesion through the design of cultural experiences that take into account diverse sociocultural groups.

Nowadays, IT developers and museum specialists have in their disposal a wide selection and variety of Web 2.0 tools (blogs, Wikis, etc.) that can be used in a variety of educational scenarios, as well as a plethora of creative digital tools with a higher degree of specialization, such as Storybird (Storybird Web 2.0 tool

http://storybird.com) for creative writing short stories alongside illustrations, PowToon (Powtoon video maker Web 2.0 tool

http://powtoon.com) for creating videos, or MakeBeliefsComix (Make beliefs Comix Web 2.0 tool

http://makebeliefscomix.com) for creating comics. Another instance is PicBreeder (Pibreeder Web 2.0 tool

http://picbreeder.org/), a collaborative art application based on the idea of evolutionary art that stores images created through interactive evolution in a public gallery, where users can edit each other’s creations. Recent research works that stand out include cultural awareness games developed by the CrossCult project, where a badge system rewards users that explore how to combine paintings on a virtual gallery wall [

34], while exploring the city and contributing their stories. In this way, interactive narratives that maximize situational curiosity and learning are enabled. Furthermore, the PLUGGY project provides a social platform where audiences act as storytellers. Specifically, participants can create personalized stories and share them on social networks. The shared material is both crowd-sourced and retrieved from digital collections, allowing users to establish connections between seemingly unrelated facts, events, people, and digitized collections [

35]. Moreover, the GIFT project, designed and developed in partnership with leading museums, called the GIFT Box [

36], is a set of free, open-source tools that enables visitors to compose their own museum tours as digital “mixtapes” and share their creations with close contacts.

Such innovative approaches place interaction at the heart of the museum strategy and are considered by researchers as emblematic cases of Web 2.0 practices that enhance visitors’ skills and redefine their relationship with the museum. However, these initiatives can be considered the exception and not the rule. Paul Capriotti et al. [

37] conclude that museums currently pursue a low level of interactivity regarding the presentation of information, relying mostly on traditional forms of reporting, and practice a medium level of interactivity with regard to the interaction resources.

Nevertheless, it should be highlighted that such paradigms of shift are, as expected, followed by consequences for the visitor–museum relationship. Yet, the possible challenges and limitations of such efforts are rarely addressed and discussed in the literature, which is unfortunate since the addition and analysis of unsuccessful cases could also contribute to an improvement in current Web 2.0 practices [

38]. Paradoxical tensions may be induced that challenge museums’ authority and legitimacy and disenchant the public’s visit experience [

39]. Nina Simon [

40] further argues that visitors’ ability to produce quality content should not be exaggerated, as often happens in Web 2.0 practices, and a balance must be maintained between visitor input and curator expertise to ensure the quality and coherence of museum content and exhibition interpretation. She also reports several tension triggers such as:

Museums shape clearly defined spaces, while Web 2.0 tools define blurred boundaries allowing users to outline their own space;

Museum exhibitions are usually fixed without many alterations after their completion, whereas Web 2.0 content is constantly updated;

Museum specialists own authority in museums, but Web 2.0 practices hand power and control to users.

However, despite the challenges, experimentation with Web 2.0 practices, besides promoting greater educational opportunities for the audience and society, also offers other more straightforward benefits for cultural institutions’ operation. For example, such practices can grant access to a wide range of observable visitor data in a fast and cost-efficient way. Valuable data can be translated into a stream of continuous visitor feedback, offering insight into how audiences perceive their museum experience or even information on their thoughts regarding exhibits. Such invaluable input can contribute to cultural institutions’ practices improvement, social empowerment, and economic growth.

Specifically, the information collection around artifacts is a widely known methodology in cultural institutions [

41]. Currently, several sources of information about autobiographies, artifacts, and intangible CH can be found from DBPedia (DBpedia

https://wiki.dbpedia.org/), Europeana (Europeana

https://www.europeana.eu/en), and other sources. At the core of figuring out the ways people perceive a given cultural item to serve large-scale research initiatives, there is the need to describe in a computer-understandable manner how they interact with it. Specifically, computer–audience interaction is needed for precise user modeling and content analysis in order to provide successful user experiences and generated content metadata. With the rapid rise in social networks and media in recent years, many research approaches focus on social interactions in order to design a general understanding of people’s behaviors and their cultural background [

42]. On top of this, social media and networking sites are the virtual space where subjects publicly interact and exchange views on several emerging issues. In particular, large-scale information on what people believe about any given topic remains present online in the form of social network activities.

Another part of research in this direction focuses on online experiences such as behaviors, tendencies, and preferences related to a user’s activity. General user modeling techniques can be classified based on how much information they need from users and how they extract such information from their behavior. In particular, such techniques can either directly ask the user their personal information (explicit feedback) or simply extract it from specified user activities (implicit feedback) [

43]. Directly asking information can be considered invasive; therefore, studies are focused mainly on the latter case, where users do not provide personal info and the modeling is based on how they behave in certain times, such as the recording and analysis of users’ clicks in web page navigation [

44].

To conclude, cultural institutions in collaboration with computer science experts can envision and construct adequate virtual and shared spaces to encourage visitors to create their own personal narratives within the museum space that best reflect their goals and needs. However, the degree of integration of Web 2.0 practices by museums surely depends on their readiness to redefine their relationship with their audience, and each case should be studied on its own. The adoption of Web 2.0 philosophy is understandably not a simple matter to approach and requires the creation of a completely new vision, one many museums are not familiar with. Although many already speak of a new digital and participatory revolution [

45], this evolving process in the relationship between museums and their visitors is actually part of a movement that started many years back, with many unresolved difficulties [

39]. As aforesaid, the matter of maintaining a certain degree of control over published content and reconciling the quality of information with users’ freedom of participation is of great importance for a museum’s authority and reputation [

30,

40]. This is an issue that surely requires the establishment of a delicate balance between different priorities. Therefore, the ongoing talk about Web 2.0 tools viewed as a kind of panacea in the museum sphere calls for a cautious re-examination of current practices [

39]. As [

30] suggests, there is a lack of awareness of the potential of Web 2.0 for creating virtual communities around cultural institutions.

Instead of simply identifying technology tools, museum specialists should define specific goals before selecting appropriate technology solutions [

39]. On the other hand, the adoption of Web 2.0 practices, even if they are well designed, unfortunately, does not guarantee the creation of a virtual meeting point in museum settings [

30]. Usually, pre-existing active communities create successful museum virtual communities, while social media tools are used to enhance communication among its members [

30]. Museums use web tools differently depending on their philosophy of communication and their identity [

46]. However, it remains of great importance to continue the further research on both successful and unsuccessful cases of Web 2.0 museum practices that experiment with the concept of how visitors can be engaged in cultural learning processes, where identity can be shaped, merging the domains of individuality and collective cohesion.

4. Design and Development of the Proposed Tool

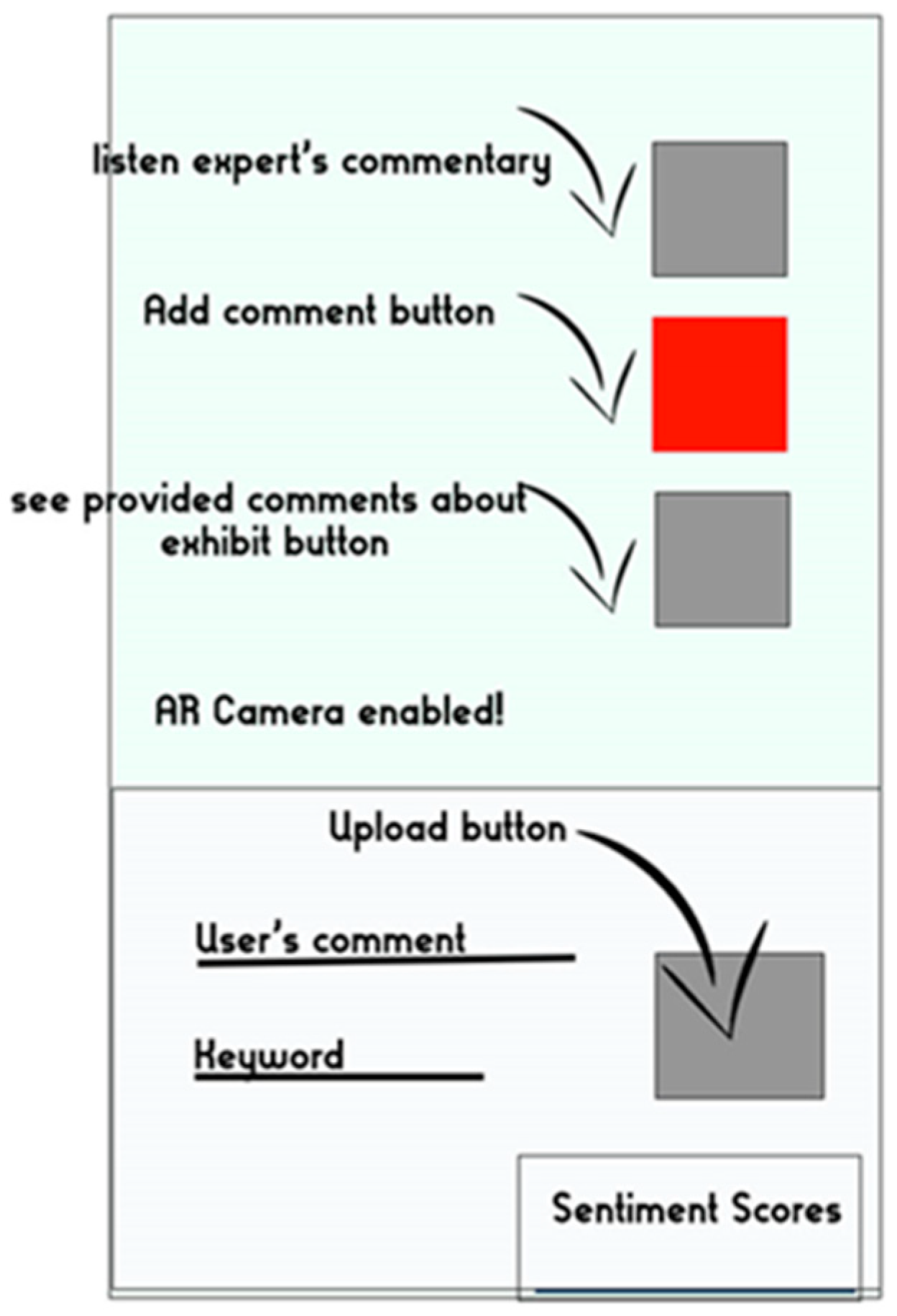

Taking into careful consideration the sections of the social learning theories and the state-of-the-art analysis, the scope of this research work is to design, to develop, and to provide an efficient and creative technology-based solution that could facilitate the creation of a virtual learning community for curators and museum visitors, aiming to motivate participants to practice in discussing art and enable many types of interactions among them. In order to introduce an adequate Web 2.0 technology to museums that are typically less open to innovation, the proposed tool should facilitate such outcomes in an affordable and technically minimally demanding way for museums and its staff and visitors; a user-friendly tool where curators can offer expert commentaries on highlighted artifacts in the museum exhibition, follow and monitor visitors’ activity, and interact with them. On the other hand, the proposed tool could also be used by visitors as a self-guided tour tool for exploring exhibitions. However, the audience should not be expected to remain passive, but on the contrary, should be encouraged to adopt an active role by offering input, expressing feelings, accessing each other’s generated content, and providing each other with feedback. Therefore, the upper goal is to foster such a museum network activity that encourages a collective discussion with audiences by enabling visitors to relate to the exhibits by interacting with fellow museum visitors, learning from each other, and questioning their own understanding, while being exposed to a range of different perspectives concerning the same matter.

In more detail, for the creation of an efficient and easy-to-use mobile app, the 10 heuristic usability rules proposed by Jakob Nielsen [

47] were followed and a heuristic evaluation was performed by having a number of individual evaluators inspect the interface by themselves. Prior to the implementation of the application, early usage scenarios were created (storyboards), which showcased a detailed description of the key features of the application using images and comments, and acted as guiding resources for its development (see

Figure 1). The produced outcome of the design and development process was named ‘ARtful’.

Figure 2 depicts screenshots of its intro video. The font’s shapes cross over and its colors are blended, representing the forming of an open, participatory and fluid community.

Next, in

Section 4.1, the technological framework of the ARtful mobile app is briefly explained, as is how the application can be downloaded and installed.

Section 4.2 presents the registration and login phase a user has to go through to use the app. Furthermore,

Section 4.3 describes the components of the user interface (UI) of the application and the bottom menu for navigating through the screens hosted inside the app.

Section 4.4 presents the addition of certain gamification features that aim to acquire, engage, and retain users. Finally,

Section 4.5 provides some brief conclusions regarding the design and development process.

6. Conclusions

The degree of integration of Web 2.0 practices by museums depends on their readiness to redefine their relationship with their audience, although it is understandably not a simple matter to approach and requires the creation of a completely new vision, one with which many museums are not yet familiar. In this context, based on the analyses of modern social learning theories and state-of-the-art technologies, this study proposed the implementation of a novel social media tool that can be used as a self-guided tour tool with AR features by visitors. Its use may facilitate the creation of a virtual learning community of museum curators and visitors that will enable art discussions, information sharing, and other interactions in a cost-effective and less technically demanding way. The proposed tool’s scope is to connect the individual interactions of users, creating a virtual meeting point and a space for publishing content, as happens in popular social networks. Hence, visitors become co-creators of the offered museum cultural experience and are exposed to different perspectives and opinions, thus strengthening social cohesion and inclusion. In addition, taking into account potential worries of museum experts, certain capabilities were added to their accounts to allow them to have more control over the visitors’ generated content.

Evaluation results, derived from a small-scaled experiment in cultural settings with potential users, have shown the positive potential of the ARtful mobile app. In more detail, participants considered the proposed app satisfactory and efficient, its visual elements pleasant and helpful, and its setup easy to do. Furthermore, they positively evaluated its educational character, stating that the art discussion experience would be easier with the use of such an app in exhibition spaces. They also expressed a positive attitude toward the idea of using such an app in museum settings to enhance their interactions with other visitors and museum specialists, since they claimed that they enjoyed reading other visitors’ generated content. In general, they perceived the proposed app as an efficient, satisfactory new tool to be used in in the cultural sector. Furthermore, participants showed a rather positive attitude toward its potential to create an online community in museum settings, since participants stated that that its use enhanced their feeling of participating and belonging during their exhibition experience, an incident that motivated them to share more meaningful content. However, although the majority of them shared relevant information regarding the exhibits, their interactions remained on a superficial level, since incidents of discourse among them were of limited quantity. Therefore, it is important to mention that the creation of a functioning online learning community cannot be the result of merely using a social media tool, even a well-designed one. On the contrary, it is usually a museum staff’s task to develop the community and improve discussions and debates [

30]. Their stance, along with the audience’s attitude toward the adoption of such Web 2.0 practices, plays a principal role in the development and maintenance of an efficient virtual community, but, unfortunately, such parameters are also unpredictable and tend to vary from case to case.

The findings of this study highlight several directions for future research. First, from a technological point of view, future work will focus on improvements derived from feedback gained from how users interacted with the proposed app during the assessment process, so its use can become more efficient. Specifically, future refinements may concern the improvement in user experience through refining and redefining the app’s information architecture for ease of navigation and usability. Furthermore, future work may include ARtful’s development as a PWA application, so its technology framework will become lighter and better support short loading times, good performance in poor network conditions, and instant updates.

Second, from a research point of view, it should be further studied how the addition of such an information stream could influence the audience’s overall museum experience, since there are already exhibitions which rely too heavily on text. John Falk and Lynn Dierking in [

54] highlight the need to find the right balance of text in museums, making sure that objects are supported by concise and effective interpretive text. In more detail, they note that inexperienced visitors face a higher risk of being overwhelmed in comparison to experienced visitors that are able to group, filter, and classify the shared information. In this case, a potential research question of great interest could be the effect of the ARtful mobile app to the Interactive Experience Model [

54], which suggests that a museum visit takes place within three contexts: the personal, the social, and the physical. Specifically, elaborating on the use of such a tool in museum settings and examining whether its addition enhances or deteriorates visitors’ experience could yield useful information concerning both the proposed tool’s functionalities and diverse audiences’ behavioral patterns.

Next, further research should be conducted and, in particular, more large-scale controlled experiments should be organized in close cooperation with museum staff and diverse audiences to study how such a tool can adapt to different museum settings and improve visitors’ experience under varying circumstances. For example, since results showed that the use of the proposed app can enhance a museum’s network activity, such a tool can be used, for instance, by memorial museums on the work concerning transitional justice in domestic tourism [

55]. By enabling visitors to relate to the exhibits by interacting with fellow visitors and museum experts, while being exposed to a range of different perspectives concerning the same matter, the relationship between individual experiences in memorial museums and wider societal process of coming to terms with traumatic past histories can be further studied. Last but not least, the proposed tools’ impact can be studied in the context of both rural and urban tourism development, researching its use and adequacy for the participatory creation of interactive digital cultural experiences (e.g., AR enhanced self-guided tours for open-air museums). Such an application can allow the engagement and interaction of multiple stakeholders, a process of underlying importance according to [

56].