2. Theoretical Background

On 7 May 2022, alerts in the UK were skipped when the first case in European territory was reported. The virus quickly spread across Europe and Latin America. On May 23, the World Health Organization (WHO) Managing Director Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus stated that the risk of monkeypox was moderate globally, except in Europe, where the risk was assessed as high. Likewise, a clear risk of international spread was warned, and the following was noted:

“Although I am declaring a public health emergency of international concern, for the moment this is an outbreak that is concentrated among men who have sex with men, especially those with multiple sexual partners […] It’s therefore essential that all countries work closely with communities of men who have sex with men, to design and deliver effective information and services, and to adopt measures that protect the health, human rights, and dignity of affected communities” [

1].

Although the Spanish Society of Epidemiology (SEE) points out that cases are milder than those detected in West Africa and require fewer hospital admissions, it warns of the discomfort caused by skin and mucosal lesions, so it recommends vaccination for target groups. In fact, since 2013, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has authorized a vaccine for smallpox in adults, marketed as Imvanex, which is now under review for use against simian smallpox. In the US, the FDA also authorized its inoculation, in this case, marketed under the name Jynneos.

In general terms, the target audience is, on this occasion, the laboratory staff or close contacts of those affected, although in Spain, it is specified that “those under 45 years of age who maintain high-risk sexual practices, mainly but not exclusively GBHSH (Gays, Bisexuals, and Men who have Sex with Men)” should be vaccinated [

4]. On 20 July 2022, Catalonia and Madrid started the vaccination campaign, which, given the small number of doses they had (5300 vaccines), required a remittance [

5]. This massive buyout triggered the stock exchanges of Danish biotech Bavarian Nordic, which “saw its shares grow by 53% after the US contract for 115 million to buy a lyophilized version that protects up to 85%” [

6].

As the SEE postulates, the underdiagnosis of monkeypox and a delay in the reporting of new cases make it difficult to contain the outbreak. Additionally, “communication is essential to avoid rumors and misinformation and help mitigate the transmission of a disease such as a monkeypox” [

4]. Therefore, they give a priority role to truthful information and correct scientific disclosure. On May 19, the WHO issued an explanatory dossier on the disease, reflecting, among other aspects, a journey through its evolution, epidemic outbreaks, transmission routes, signs, and symptoms, treatments, vaccination, and various recommendations for the reduction of transmission. The Pan American Health Organization [

2] proposed four lines of action, among which communication was a fundamental axis. On July 6th, the SEE launched a guide to address the disease from an approach away from stigmatization and discrimination toward certain groups. The document, prepared by the SEE’s Working Group on Gender, Affective-Sexual Diversity, and Health, is intended for healthcare professionals, and highlights six recommendations [

4]:

Use language appropriately, and craft messages with accurate, complete, and up-to-date information.

Adapt communication strategies in each case to effectively reach the target population, providing sufficient data in an understandable manner, and without losing sight of those with a lower level of health literacy.

Build trust among the population, although there is still significant uncertainty regarding monkeypox since the characteristics of the current outbreak do not correspond to those known previously, including their clinical presentation, as well as the routes of transmission and the affected population.

The right to enjoy a full and satisfying sex life, which involves protecting the health of oneself and sexual partners, knowing the state of health, and negotiating the safest practices.

Articulate prevention strategies in a coordinated manner among institutions, expert individuals, NGOs, and civil society organizations and consider the participation of the populations involved at all levels. In this regard, consider that experience in the management of HIV and STIs may facilitate this process.

Involve the community in health alert situations from the moment of participation so that its members do not feel excluded from the decision-making process.

On July 22, the SEE issued a final press release in question-and-answer format to resolve questions about the disease and vaccination.

In the face of continued growth, on July 23, the WHO declared monkeypox an Emergency of Public Health of International Importance (ESPII or PHEIC). On July 29 and 30, the first two and only deaths occurred in Spain. On August 4, the U.S. proclaimed a national health emergency in the face of new cases.

Scientific Misinformation and Fact-Checking

The demand for information in times of social instability is evident during health crises; in fact, in the 2022 outbreak of monkeypox, the public’s interest in being informed after the WHO declaration of 23 July was 103% [

7]. In this context of constant informative demand, the dissemination of scientific misinformation has become a first-order problem for democracies [

8]. From the explosion of misinformation, disinformation, and misinformation [

9,

10,

11] during the health pandemic, fundamentally viral in the digital stage [

12,

13,

14], this problem has been addressed by agencies and institutions [

15] that ensure the sanitation of public discourse to reduce the disinformation interest adopted by anti-vaccine movements [

16,

17], political personalities, such as Donald Trump or Jair Bolsonaro, or medical groups that place home remedies that induce and produce a public health hazard by recommending the cure for diseases through natural therapies, harmful compounds for health and unregulated medical practices, against the safety and effectiveness of vaccination [

18], more specifically, stigmatizing the COVID-19 vaccine [

19].

López-Pujalte and Nuño-Moral [

20] point out that Spain and Latin America are at worrying levels of misinformation, especially in countries, such as Argentina and Ecuador, where this false and deceptive content grows at a rapid pace, many with a political component that emphasizes marked distrust and political disaffection [

21]. During the pandemic, the studies indicated this disinformation increase [

22,

23,

24,

25], as occurred with vaccination, whose discursive axes revolved around the side effects derived from their inoculation and conspiratorial theories that point to governments and pharmaceuticals as bioterrorists.

For this reason, it is essential to understand the mechanisms of production and the channels of dissemination of fraudulent content [

26], especially when misinformation is scientific in nature and may pose a risk to the population, contributing to reducing vaccine predisposition [

27,

28]. To filter the overabundance of information [

29], fact-checking [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35] is presented as an effective possibility to heal, contextualize, and cure the content [

36,

37,

38,

39].

The screening procedure is common in all of these agencies and is based on a selection of potentially false or misleading content, which is received by the audience, which becomes an information monitor [

32], or at the initiative of these professionals, who check public figures or viral content on social networks. Once the texts have been selected, they undergo a treatment that is based on a documentary and scientific review, in the resource of the sources of information (expert statements and interviews, official or scientific documents, etc.), in material extracted from the media, and to work jointly with other fact-checkers. This is complemented by the verification of images, videos, or texts through digital tools and, finally, by typological classification according to the degree of intentionality and maliciousness pursued by said content. At this point, in the categorization point, some of these agencies disagree. The disparity in classification causes some organizations to speak up about false, misleading, decontextualized, or true information, among others. After the completion of this last step, they prepare the check-in note or dismissal in an informative tone to be disseminated by their social networks and their respective web portals.

From this perspective, this work seeks to understand the scope of misinformation and the reaction of verification bodies to contain false and misleading information that emerges in this new public health emergency, given the sensitivity from which citizens began at a time of convulsion for science. As the task of the fact-checking agencies grew exponentially during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the emergence of a new outbreak of monkeypox also leads us to assume high activity in this journalistic specialization [

38] to heal media speeches and try to preserve the truth in science. The interest of this research lies in the absence of scientific literature on the subject and in the importance that hoaxes are disseminated and become viral that harm the containment of the virus and magnify the transmission of the disease, paying special attention to the alert created around vaccination processes as an effective mechanism against viral diseases.

This research seeks to study the characteristics of disinformation disseminated about monkeypox in ten Ibero-American countries that have been affected to a greater or lesser extent by this new outbreak and that also suffered a high degree of misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this regard, we consider it appropriate to understand the disinformation scope that this health emergency is having and the relationship it has with the conspiracy theories disseminated by social networks around SARS-CoV-2 in order to assimilate the continuous nature or the existence of a pattern of conduct on the creation of this false content. Specific objectives include:

OE1. To study and compare the agenda on monkeypox by fact-checkers in ten Ibero-American countries and determine the chronological evolution to estimate their actions and potential for the containment of scientific misinformation.

OE2. Analyze the characteristics of the hoax denial about monkeypox, considering aspects related to the location of the disinformant, the prevailing themes, the formats used, the social networks through which they circulate, and the capacity to transnationalize this content.

OE3. Review the activity of the Iberian verification agencies in the preparation of denials, paying special attention to the sources of information consulted and the digital tools used in these processes.

3. Materials and Methods

The methodology applied to meet the proposed objectives uses retrospective bibliometric analysis. The purpose is to extract the denials made on monkeypox by the fact-checking agencies of ten Ibero-American countries through their respective websites to quantitatively study the evolution in the production of denials by these agencies and to draw a comparison between countries and qualitatively and quantitatively analyze the characteristics of the bobbles they verify and the processes and tools used by these fact-checkers. The choice of countries is governed by a first criterion that is the language; in this case, Spanish, countries such as Brazil and Portugal are ruled out. The second condition is that they practice verification on a consolidated basis and have the seal of the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN), an institution that ensures the quality and transparency of these organizations. The representative sample consists of Spain, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela, Mexico, and Costa Rica.

Based on data extracted from the WHO, these ten Ibero-American countries total 11,501 infected as of the date of consultation for this study, 14 September 2022. Spain has 6947 cumulative cases and 2 deceased cases, followed by Peru with 1937 infected, Colombia with 938, Mexico with 788, Chile with 486, Argentina with 221, Bolivia with 110, Ecuador with 68 cases and 1 deceased, and Costa Rica and Venezuela with 3 infected cases, respectively. In the US, for example, 19,833 cases had already been detected on the same date.

The Reporters’ Lab, a journalistic research center at Duke University, has been accessed for agency selection, which has a map of verification organizations worldwide. Through this space, the fact-checkers operating in the ten Ibero-American countries selected for this study have been defined: Spain, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela, Mexico, and Costa Rica.

- ○

España: Maldita, Newtral, EFE Verifica, Verificat, and Salud con Lupa.

- ○

Argentina: Chequeado and Reverso.

- ○

Bolivia: Bolivia Verifica and Chequea Bolivia.

- ○

Chile: Cazadores de Fake News, Dínamos`s Chequeo, El Polígrafo, FactCheckingCL, Fake News Report, FastCheckCL, La Tercera Fact-Checking, and Mala Espina Check.

- ○

Colombia: ColombiaCheck, Detector de mentiras, and RedCheq.

- ○

Ecuador: Ecuador Chequea and Ecuador Verifica.

- ○

Perú: #ConvocaVerifica, OjoBiónico, Salud con Lupa, and Verificador.

- ○

Venezuela: Cocuyo Chequea, Cotejo, and EsPaja.

- ○

México: El Sabueso de Animal Político.

The temporary adjustment for the sample includes the content verified from May 7, the day on which alerts in the United Kingdom skipped when the first case of monkeypox in non-endemic countries was reported, as of September 10, 2022, the closure of the data collection of this work. This temporary space is taken into account since, as Zhou, Xiao, and Heffernan [

40] point out, the amount of information disseminated during a public health epidemic finds its peak at the start of the outbreak, remains at optimal levels during the course of the epidemic, and decreases as the extent of transmission is reduced. In total, 82 are found, which undergo quantitative and qualitative analysis through the content analysis technique [

41,

42,

43]. The test instrument is run using a coding sheet that includes the 14 parameters listed in

Table 1. The items chosen for this tab are intended to resolve the proposed objectives and were tested and validated in previous work on fact-checking during the COVID-19 health pandemic [

26,

44,

45,

46].

The registration variables allow the compilation and quantitative determination of the number of verifications by countries and check agencies, as well as the establishment of a comparison between said territories. The items that measure the characteristics of the viral content can be understood if these agencies can locate the original disinformant of the hoax (localizable), or on the contrary, it is impossible to establish its origin (unknown). If it can be located, identify whether it is a person with media significance and public notoriety or, on the contrary, whether it is an anonymous, fictitious, or impersonated profile on social networks.

The broadcast channel will allow us to conclude which social networks are used most frequently for the dissemination of misinformation (Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, TikTok, WhatsApp, Telegram, Other). They are sometimes spread on multiple social media networks at the same time (three or more). If a single network is specified, it will reflect what it is; if they are disseminated over two specific networks, these will be counted in a specific category. For example, if they are found to be viral by Twitter and WhatsApp, the category will be Twitter + WhatsApp. The format can be text, image, a text composition with image (common on social media posts), audio, or video. The registered territorial origin (international, national, and local) makes it possible to measure the geographical focus in which these hoaxes arise. If matches are detected that reveal the repetition of denials by other countries and agencies, the ability to internationalize scientific misinformation in countries that share a language can be understood.

The theme of hoaxes is subdivided into specific themes that are structured around the origin of the virus, which include conspiracy theories, side effects due to COVID-19 vaccination, and its relationship with existing ones. The characteristics of the virus will discuss the main features of the disease, its rate of spread, the target population, and its symptoms, while the risk and contagion category pertains to the transmission pathways of the virus, situations of risk, or contagion of certain people. Alleged cures and health remedies collect the contents of home remedies used to overcome the disease, the use of certain medications or vaccines, and their effectiveness. The country’s situation attempts to reflect the evolution in the number of contagions, the fatality rate, or the development of the disease in certain countries, while political/government management adheres to the measures applied by the public authorities to control the health emergency.

In order to understand the screening process carried out by the selected agencies, the interest that drives these agencies to undertake their verification is analyzed, which ranges between the virality of the content and the need to check public figures. The sources of information requested to participate in order to contextualize and deny the content are classified as sources involved (those affected within the misinformation), officers (those from institutions, international bodies and national governments, regional, and local, as well as its associated entities), experts (provide scientific knowledge and are often included within the health orbit), media (whether on media or digital), and other fact-checkers (refers to interagency collaboration to verify content). Below are the digital tools and resources used for checking images, texts, or identities on social media.

4. Results

4.1. Ibero-American Checkers against Monkeypox

The data collected for this study total 82 denials by verification agencies. Explanatory content created by verification agencies for the purpose of informing them about the nature of the virus, its routes of spread, symptomatology, treatment for its healing, and objective audiences have been discarded for analysis, since we understand that these are information that fulfills another function of fact-checking, contextualizing, and not verifying the veracity of the content. Instead, those classified in the category ‘explainer’ who respond to a request from the audience to verify a particular content and classify it as true, false, or misleading have been taken into account.

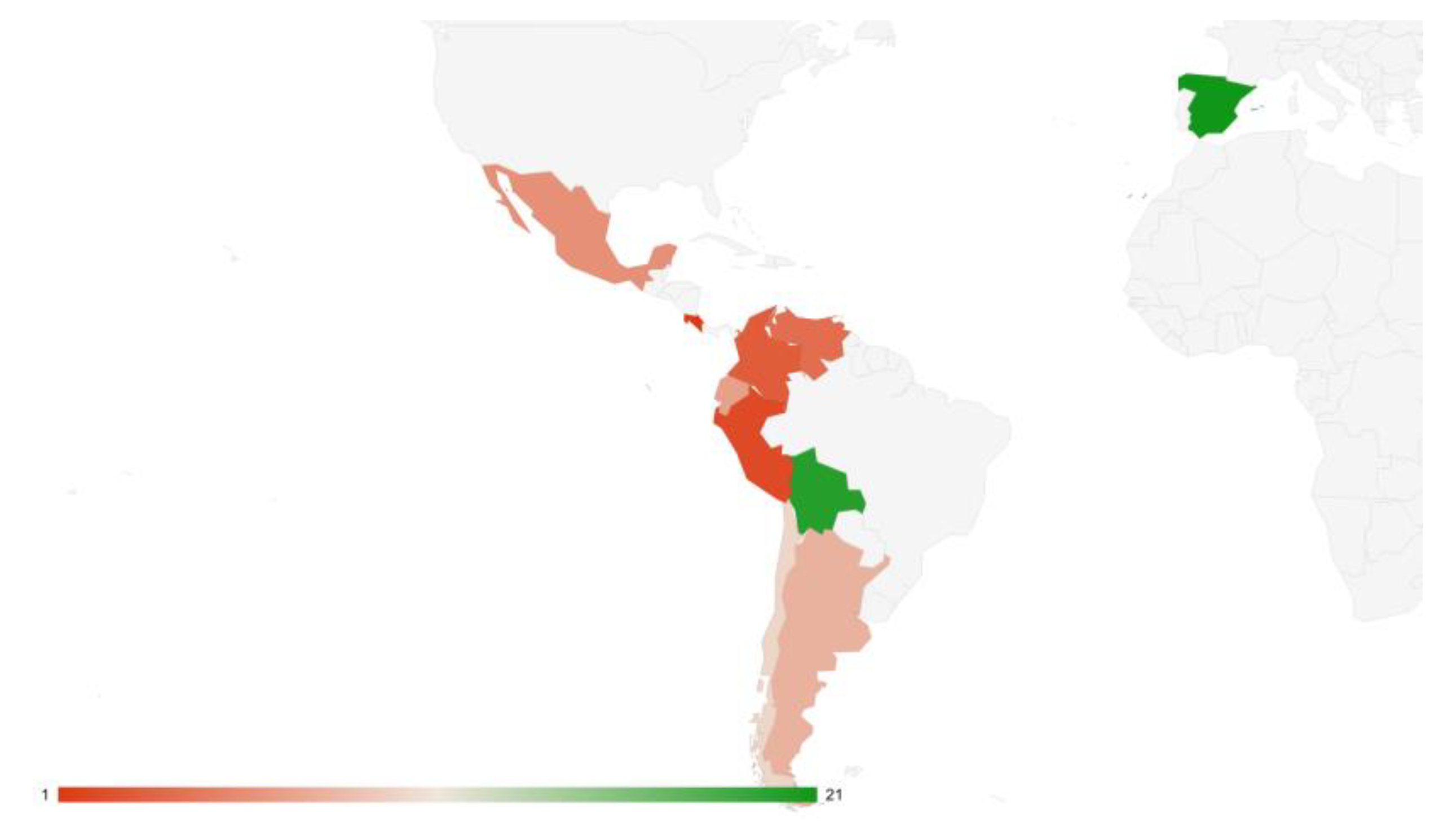

By country, Spain is the territory with the highest verification activity since the start of the outbreak, with 25.6%, and Costa Rica, with less than 1.2%. In the second position, Bolivia is 19.5%, and in third Chile it is 12.2%. It is followed by Argentina (9.81%) and Ecuador (8.5%), as shown in

Figure 1.

The verification agencies that issue the most notes are Bolivia Verifica (19.5%), Maldita (11%), and Chequeado (9.81%), three references for international fact-checking members of the IFCN, the regulatory body of the verifiers. There are some organizations analyzed that do not publish checks on their pages, such as Reverso (Argentina), Ecuador Chequea (Ecuador), and RedCheq (Colombia). In this line, we find Fake News hunters, Dinemos’s Checking, El Polígrafo, FactCheckingCL, Fake News Report and La Ter Third Fact-Checking in Chile and Health with Magnifying Glass and #ConvocaVerifica in Peru.

In Spain, in addition to Maldita (11%), the work of Newtral (7.3%) stands out; in Bolivia, Bolivia Verifica (19.5%) stands out, while in Chile, there is a relative parity between Mala Espina (7.3%) and FastCheck (4.9%), as well as in Mexico, with El Sabueso and Verificado, both with 3.65%, and in Peru, with Bionic Eye and Verificator, with 1.2% each. In Venezuela and Colombia, there is a balance between agencies, although in territories such as Argentina, Ecuador, and Costa Rica, they are centralized in a single verification entity, as shown in

Figure 2.

According to the type of content, 81.7% of false content, 8.5% of true information, 6.1% of misleading information, and 3.7% of notes that fall into the category ‘explainer’ are found.

The chronological evolution of the denials states that May was the month with the highest number of verifications, 36.6% (30), followed by the months of August, 29.2% (24), and June, 24.5% (20). The figure decreased significantly in July, 8.5% (7), and in September, 1.2% (1), although this last month has limited data as the closing of the work is 14 September 2022. As depicted in Chart 1, the days with the highest content disputed in May are 26 (8), 28 (4), 23 (4), and 22 (3), as well as on 4 August (4), as shown in

Figure 3.

By country, the data yield disparate results, as represented in

Table 2. The Bolivian verification agencies are the most active in May (10) and September (1), Spanish ones stand out in June (7), Mexican ones in July (2), and Ecuador Chequea in August (6), as shown in

Table 2.

4.2. False Content Characteristics

The characteristics of the misinformation analyzed by the verifiers enable us to understand the viralization pathways of the hoax, the location of the disinformant and its identification, the most used format, its internationalization capacity and, above all, the thematic axes and conditional intention.

Finding and identifying the disinformative source is complicated. Of the 82 hoaxes studied, in only 22, the author or primary author of the hoaxes could be identified. Therefore, in 73.17% the source of the hoax is unknown, and in 26.83%, it is localizable. Of these, 18.29% are from people and groups with public notoriety, 6.1% are fictitious, and in 2.44% of cases, they are impersonated identities. Among those identified are the protagonist who disseminated the virus in Spain on the alleged contagious metro of Madrid, @arturohenriques; other names such as Heiko Schöning of Doctors by the Truth, that of cardiologist Peter McCullough, or that of the satirical website The Babylon Bee are also notable. The fictitious sources include the @mei_rito Twitter account, formerly @SusanaPresident, which closed after the spread of the contagion hoax of buying a scooter on Wallapop; and a web portal, ‘Dato Certero’, which was opened to disseminate information about monkeypox by bouncing false content from other portals. We also found impersonations of televisions, such as Antena 3 in Spain or Unitel in Bolivia.

The highlighted format Is a combination of image and text in 39% of cases. Text is also predominant when used at 36.6%, while others such as the image (9.8%), the video (4.9%), and the video with text in the publication (1.2%) do not stand out. A high percentage is found in the ‘unspecified’ category (8.5%) since the weekly disinformation collections that have been submitted by several verifiers during the outbreak have been included in this category. This content does not refer to the features that pertain to the format, as shown in

Figure 4.

The themes in increasing order are those that refer to the characteristics of the virus (3.7%), to political/government management (7.3%), to the category ‘other’ (7.3%)—where the collections of verified disinformation already mentioned are included—to the situation of a country (8.5%), to the alleged cures and health advice (12.2%), to risks and contagions (15.9%), and to the origin of the virus (45.2%). Regarding the origin of the virus, it is revealed that 35.4% can be seen in the relationship between the onset of the disease and the side effects derived from the AstraZeneca and Pfizer vaccines for SARS-CoV-2.

Misinformation about the origin of monkeypox also recovers other vaccine hoaxes that talk about conspiracy theories that focus on Bill Gates as a bioterrorist or the pharmacists themselves as allegedly interested in the expansion of these types of diseases for business enrichment. Those who refer to risks and contagions focus mostly on stigmatizing the LGTBI+ group, by classifying it as a sexually transmitted disease, also linked to AIDS. In addition, other subtopics such as those that mention animal contagion, the alleged condition of a Colombian politician, such as Rodolfo Hernández, or the possible routes of transmission by physical contact are highlighted in this topic.

The hoaxes that affect the cures are based on the creation of new vaccines, the alleged coverage provided by existing sera, such as Emergent Biosolutions, or the remedies already proposed to cure COVID-19, such as hydroxychloroquine. Those referring to the situation of the countries refer to the appearance of the first cases, alleged outbreaks, and the deceased, which in the case of the countries analyzed is limited to three. Hoaxes are disseminated on political management that announce measures or false contagions of public personalities that directly affect the country’s management.

By country, Spain is the predominant territory for hoaxes circulating on the origin of the virus, risks and contagions, and the alleged cures and health advice, while Bolivia is the country that stands out for misinformation about the characteristics and Ecuador about the country’s situation (

Table 3). Bolivia stands out for political management and government, as does the category ‘other’.

The spread of this viral content checked by the organizations studied materializes through several social networks at the same time (34.1%). Twitter is the network through which the most misinformation circulates (24.4%), followed by Facebook (18.3%) and ultimately by WhatsApp (3.7%), Telegram (2.4%), and TikTok (1.2%). In addition, certain combinations between networks, such as Facebook and Twitter (8.5%), Twitter and Telegram (3.7%), WhatsApp and Twitter (1.2%), and Facebook and Telegram (1.2%), are repeated. No viral YouTube misinformation has been verified, and in the category ‘unspecified’, we found a value of 1.2%.

On the territory covered by this checked content, a high percentage of international (74.39%) and local (7.32%) disinformation are observed, well above national (18.29%) and local (7.32%) disinformation. The premises are located in the Community of Madrid (Spain) and refer to the blunts about transmission in the metro and by the electric scooter purchased in Wallapop, both originating from a Twitter thread. This last hoax was viral and reached Peru, where the content was denied by the Bionic Eye. The false content whose territorial demarcation is national are located in Latin America, specifically Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia, Costa Rica, and Venezuela, and on one occasion, in Spain. In the ‘national’ category, check-ups stand out to public figures, especially in the case of Bolivia.

When correlating the territory with the theme, it can be seen that national hoaxes are 46.7% of a country’s situation, 33.3% of management and policy, 13.3% of contagions, and 6.7% of the origin of the virus, specifically, on its relationship with the COVID-19 vaccine. Local hoax dozers occupy 100% contagion-related issues, especially in terms of transmission numbers and counts. In contrast, international misinformation refers to the origin of the virus at 59%, of which 45.9% corresponds to the side effects of the vaccines used during the pandemic. A total of 16.4% refers to remedies and cures, such as the use of hydroxychloroquine, 8.2% to contagions, and 4.9% to the characteristics of the virus, classifying the LGTBI+ group as a transmitter of the disease. A total of 1.6% talk about management and refer to false information announcing that WHO had proclaimed the monkeypox outbreak as a pandemic. The ‘other’ category occupies 9.8% and deals with weekly collections on international blunts. It should be noted that all information checked and rated as true are Colombian, Ecuadorian, Venezuelan, and national.

When the territory is international, it is discovered that there is a greater chance that this false content will become transnational and circulate in several countries at the same time. Local hoax dozers hardly have this possibility, while national content traverses multiple territories. For example, in Spanish, hoaxes about fake Twitter threads are made to create social alarm, but not in Bolivia or Chile, whose themes are political. As represented in

Table 4, there is disinformation that has become viral in several Ibero-American countries, sometimes on the same day or with little margin of delay. The hoax that spread the most was the one that alludes to the origin of monkeypox as a side effect of the COVID-19 vaccines, as well as others that resemble the disease to shingles, confusing and making it difficult to diagnose and treat it.

4.3. Verification Process—Sources and Semantics

The initiative that drives fact-checking agencies to initiate a verification process is, firstly, due to the viralization capacity of the hoax (89.2%), and secondly, to the check of public figures, whose message has a greater impact and significance, although in this case the figure is significantly lower (10.98%). Verification of public policy and management speeches is usually limited to statements by representatives or official institutions, such as the WHO, which should mark guidelines on health emergencies.

Fact-checking requires sources of information and digital tools that allow information to be corroborated or disproved, if possible, with scientific and divulgation richness. Therefore, after this analysis, it is verified that only 1.2% do not reference the sources used in the note. In addition, only 7.3% of the content studied uses a single source. This is official at 3.7%, involved at 2.4%, and expert at 1.2%. There is no check-up with the media or other fact-checkers as the sole source of information.

A total of 92.7% handle a variety of information sources, at least two or more. In particular, 44% opt for two sources (Official and expert: 30.5%; involved and media: 3.7%; involved and other fact-checkers: 1.2%; official and other verifiers: 1.2%; official and media: 3.7% and official and involved: 3.7%). The use of three sources of information is 37.7% (Official, expert, and media: 14.6%; official, expert, and involved: 6.1%; official, expert, and other fact-checkers: 11%; official, involved, and other check agencies: 2.4%; official, involved, and media: 2.4% and expert, involved, and other fact-checkers: 1.2%). The use of four sources already has limited figures, in particular, 8.6% (Official, involved, media, and other verification agencies: 1.2%; official, expert, involved, and media: 1.2% and official, expert, media, and other fact-checkers: 6.2%). Verification notes using five sources are cut to 1.2% (official, expert, involved, media, and other screening agencies).

Official sources include public bodies and national and international institutions related to the scientific and health field, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), the WHO, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Community of Madrid, the Vaccine Advisory Committee (CAV) of the Spanish Association of Pediatrics, the Spanish Association of Vaccinology (AEV), the UK National Health System (NHS), the American Academy of Dermatology, the Spanish Society of Preventive Medicine, Public Health and Hygiene (Sempsph), the European Medicines Agency (EMA), the National Vaccine Safety Commission (CoNaSeVa), the National Council for the Prevention and Control of AIDS (Conasida), the UN, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), the governments of Argentina, or the Community of Madrid.

Expert sources include renowned specialists in social health care and scientific fields such as Victor Jimenez, UCM Professor of Microbiology; Matilde Cañelles, CSIC immunologist; Rafael Blasco, National Institute of Agrarian and Food Technology and Research (INIA-CSIC) virologist Paloma Borregón, Dermatologist of the Fundación Skin Sana of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV); Jacob Lorenzo-Morales, Professor of the Parasitology Area and Director of the University Institute of Tropical Diseases and Public Health of the Canary Islands of the University of La Laguna; Gunnar Jeremias, Head of the University of Hamburg Interdisciplinary Research Group for Biological Risk Analysis; Mariano Esteban, CSIC investigator; Salvador Peiró, Physician specializing in Preventive Medicine and Public Health; César Ríos Head of Epidemiology of the Departmental Health Service (HQ) of Chuquisaca (Bolivia); Diego Peña, Professor of Organic Chemistry at the University of Santiago de Compostela; or publications in indexed scientific journals, such as The Lancet, from which work, such as Herpes zoster related hospitalization after inactivated (CoronaVac) and mRNA (BNT162b2) SARS-CoV-2 vaccination is extracted: A self-controlled case series and nested case-control study.

As sources involved, we found some of the accused pharmaceutical companies, such as Emergent Biosolutions and Pfizer, as well as other organizations, such as the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities (Conaie). Among the media, we can review the consultation with El País, Cuatro, Antenna 3, LaSexta, 20minutes, Agencia SINC, Eurosurveillance Monthly, TheHealthSite.com, The New York Times, El Hufftington Post, El Universo, El Vanguardista, France24, and BBC, among others. Among the verification agencies consulted, the Spanish verifiers Maldita, Newtral, and verificaRTVE, the British Full Fact, the Chilean Mala Espina, the Argentine Chequeado, the German Correctiv, and AFP Factual stand out, which are based in different countries.

Verification notes also display in their texts some of the digital tools and resources for checking images, such as Google, Google Lens, Yandex, or InVid reverse search, and advanced search on social media, such as Twitter or Crowdtangle on Facebook. Despite the mention of these resources, as well as the observation they state, it should be noted that the basis for verification is determined by the wealth of information sources used in the text (

https://bit.ly/3Y3I6i8).

5. Discussion

Responding to OE.1, the countries in which the most content has been verified about monkeypox have been Spain and Bolivia, as well as the agencies that register the most activity, Maldita and Bolivia Verifica. The months that accumulate the most misinformation are May, the start of the outbreak, and August, after having been declared a public health emergency on July 23. At the beginning, Bolivian fact-checkers showed the greatest verification capacity, and in June, it was the Spanish. Ecuador expedited its activity in August.

OE.2 focuses on the characteristics of disinformation: location of the disinformation source, broadcast channel, format, theme, and territorial scope. Locating the disinformant source is complicated, with 73.17% of unknown origin. Localized disinformation experts include those with media significance, such as Doctors for Truth, this time with input from Heiko Schöning, its founder in Germany. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this negationist group took on a major role. There are also fictitious sources on fake Twitter profiles or spoofed sources that emulate media, such as Antena 3 in Spain and Unitel in Bolivia.

The formats used are the image with text at 39% and the text at 36.6%. This predominance of the text has already been exposed in previous works [

26,

45] and can reveal to us that in video or audio, the dissemination of misinformation becomes more complicated, probably due to the greater effort in its creation [

46]. There is an added problem, and it is that many of the images used are alarming and correspond to other infectious processes that have nothing to do with monkeypox. This has also occurred in the media, as reported by fact-checkers in various verifications. If, in addition to sensational images, they are false and correspond to other diseases or viral processes, the creation of social alertness and confusion is greater. The broadcast channel in individual terms is Twitter (24.4%), although they are usually distributed through several social networks at the same time (34.1%), following the line of other works [

26]. Although other social networks, such as TikTok, have not been considerable transmission vehicles, when they have done so, it has been with a high impact, since there are bugs with more than 43.6 thousand reactions, 2427 comments, and 21.6 thousand shared on this social network.

The star theme is the one that concerns the origin of the virus (45.2%), especially the one that considers it a side effect of COVID-19 sera from AstraZeneca and Pfizer, a topic that also recurred during the pandemic [

18]. The disinformation explosion may be related to the reactivation of the anti-vaccine movement, which has regained momentum, with discursive axes already employed during the health pandemic. The same threads are followed concerning COVID-19: origin of the virus (Bill Gates, side effects of vaccines, reduction of the global population, economic objective of pharmaceuticals, etc.); creation of an alert for new cases and stigmatization of groups, in the pandemic on immigrants [

21], now on the LGTBI+ group, something of which scientific experts have warned. This can cause irreparable harm by confusing the population and making them think that they cannot become transmission vehicles: “stigma and discrimination can be as dangerous as any virus” [

4]. Other topics that are also recovered from COVID-19 hoaxes are those that refer to political management and health response and cures with home remedies or ineffective treatments with hydroxychloroquine. In addition, there is speculation about the effectiveness of other vaccines for monkeypox or the creation of a new serum.

Depending on the territory in which this verified content is framed, international content is predominant, which stimulates its internationalization, according to other studies [

46,

47]. It is important to note that those circulating in more countries are the most sensationalistic, or those that had already emerged, with nuances, during the health pandemic. Despite this, there are national hoaxes that are also easily internationalized, given the social panic they pursue when claiming a contagion by physical contact.

The results demonstrate that the hoaxes circulating in these ten Ibero-American countries over monkeypox are closely related to the vaccine and negationist groups arising and magnified during the COVID-19 health crisis. Although the magnitude of the problem is not such, the risk is significant, as all scientific misinformation endangers public health, even more so when the disease is disclosed as a sexually transmitted disease linked to specific groups that are stigmatized. As Salvi and Schittecatte report [

48]: “Stigma and fear can hinder public health responses, whether it’s because it leads people to hide their disease, avoid seeking medical care, or adopt healthy preventive behavior” (p.7).

The activity of fact-checking agencies (OE.3) shows that the initiative to verify content is intrinsically related to social media echo and viralization, which is explained by the implications of creating disinformative echo cameras in digital spaces [

19]. On the other hand, public figure screening is reduced because scientific misinformation is not usually of political origin. To begin verification after selecting potentially fake content, organizations opt for information sources to debunk, contextualize, and cure hoaxes. This work demonstrates the importance of the sources of information and wealth used by these agencies, as only 7.3% use one, while 92.7% use two or more sources. Those who stand out are the officers and experts, although they also request the intervention of the sources involved, the media, and, with limitations, other fact-checkers. On these, it is revealing that Maldita and AFP Factual are the organizations from which most checks are replicated. Digital tools are applied for image checking with Google resources or other search engines, such as Yandex, as well as resources provided by social media, such as CrowdTangle on Facebook. Despite being used in some verification notes, these digital resources complement informational sources.

6. Conclusions

Although Spain is the country with the highest number of content denials by the verification agencies and the one that has reached the highest number of infections during the new outbreak of monkeypox, it cannot be considered that the agenda by the Ibero-American countries is comparable to the task they performed during the health pandemic, although the severity and impact of this outbreak are also not comparable. It is also not possible to establish a direct relationship between the increase in health affectation and the greater activity of these screening agencies. This is evidenced in countries such as Peru, Colombia, and Mexico that have high transmission figures and not an increase in their verification. The downside is a coincidence between both criteria in the case of Costa Rica, a country that reports fewer cases and verifies less. On the other hand, Venezuela, which confirms, similar to Costa Rica, three cases, shows greater activity than transmissibility, which is the opposite of Colombia, whose verification is scarce, but its level of contagion is high. This data prevents accepting such an interrelationship as a trend.

The results on the evolution of the tasks of these organizations and the dissemination of false and misleading content demonstrate that it is essential to control misinformation in the first days of any health crisis to avoid the multiplication of disinformation and misinformation. Exponential growth emerged in the days following the announcement of the first cases in Europe in May, and in August, when the virus began to expand vigorously and was declared a public health emergency by the WHO. This early state of epidemiological disclosure is essential, as other work on COVID-19 points out [

49]. On May 18, Bolivia was the first Latin American country to deny the hoax, in this case, relating it to the side effects of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. In Spain, the first denial took place on 23 May and coincided thematically with Bolivians. It should be noted that the first references to monkeypox are found in early May, although these are included in the explainer category, and they are responsible for informing about the nature of the disease itself and not of blunts.

It should be concluded that scientific misinformation seems to arise with each of the health alerts and emergencies since there is a hard core of denialists [

44], largely articulated by doctors and public personalities, who have become false counterfactual figures, who use emotional weapons on social networks, taking advantage of the fact that they are fast-transmitting vehicles. This study demonstrates the interrelationship that exists between the hoaxes located in the context of COVID-19 and those referring to the outbreak of monkeypox. The simplicity with which false and deceptive content can be created and false profiles can be created on social networks negatively impacts the containment of misinformation, a fact that, together with the speed of the network and the informative amalgam poured daily that intoxicates the citizens, makes it difficult to retain this malicious viralization. In addition to this, the facilities found by the disinformants to disseminate their hoaxes on social networks and the performance of certain media outlets that have come to amplify their speeches see the case of the hoax of the infected in the Madrid metro (Spain) and whose protagonist copied minutes on Spanish private televisions.

Therefore, institutions should not only advocate for appropriate scientific disclosure, with up-to-date communication tools, such as online campaigns and social media management, or with the publication of materials available to communicators and educational and graphic resources; they should also study and discuss with cross-functional experts the impact and positive or negative echo that the verification process exerts on citizens. At the same time, it is relevant to speed up verification times and the creation of screening techniques to increase the reach and interaction of the public, to not only serve as a retaining wall in the dissemination but as another factor that contributes to the media literacy of the audiences. Here is a possible way of study that analyzes whether fact-checking achieves the interaction and engagement necessary to alleviate this climate of uncertainty and communicative disaffection. To do so, it may be interesting to investigate the potential of social media verifiers instead of the rhythms of misinformative hatching through these avenues.

The main limitation of the investigation has been the reduced activity of the verification agencies around the monkeypox. This has resulted in a sparse but representative sample by collecting all cases published by the verification agencies. The conclusions would have been more robust if a larger sample had been available.