Abstract

Services rendered by bug hunters have increasingly become an indispensable component of the security culture of organizations. By pre-emptively locating vulnerabilities in their information systems, organizations reduce the risk and the potential impact of cyberattacks. Numerous studies have been conducted on this phenomenon; however, the motivational factors driving bug bounty hunters remain underexplored. The present paper aims to further investigate the factors that affect the behavioral intentions of bug hunters by empirically studying 386 computer security professionals across the world. We found that the attitudes behind bug hunters’ intentions are formed by exposure as well as their curiosity regarding the topic, which in turn is modulated by their intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. Our study further highlights the impetus behind effective management of cybersecurity personnel.

1. Introduction

Cyberattacks pose a significant global challenge, with some sectors experiencing a 300% annual increase [1]. The rise in cyberattacks can be attributed to the widespread adoption of advanced technologies such as the Internet of Things, Cloud Computing, and Artificial Intelligence [2,3]. With a significant increase in the number of connected devices, the vulnerabilities have risen as well. As a result, researchers and practitioners are concentrating on enhancing organizations’ preparedness in managing cyber risks [4,5].

Cyber-attackers identify and exploit bugs or vulnerabilities in systems’ defenses for nefarious purposes. In the context of IT security, a bug is defined as an error, fault, or flaw in a computer program or hardware system that causes unexpected results or behavior [6]. In order to prevent malicious hackers from gaining unauthorized access to their systems and data, organizations need to pre-emptively identify vulnerabilities in their technical systems [7]. Staying at the forefront of cybersecurity could be a resource-intensive task for organizations that wish to keep their systems secure [8]. This organizational challenge is further exacerbated by a shortage of security professionals in the workforce [9] with the requisite skills and experiences [10]. As a result, organizations have started exploring alternative options, such as using bug bounty programs, which involve crowdsourcing vulnerability searches by utilizing the expertise of external bug hunters, also known as white hat hackers, from around the world [10]. These programs allow bug hunters to test the security of an organization and report their findings [11].

Bug bounty programs have become a widely adopted, cost-efficient approach to leveraging external talent for identifying security vulnerabilities, providing a structured and effective way to strengthen cybersecurity [12]. In addition to organizations running their own bug bounty programs, third-party platforms like HackerOne facilitate these efforts. By 2020, HackerOne had over 100 participating organizations and 800,000 registered users [13].

Despite the benefits of these programs, there are challenges associated with working with bug hunters for organizations as well as researchers [14]. A significant issue identified by [15] is that, within organizations, many security professionals do not receive the same rewards as bug hunters, which could lead to a situation where permanent employees choose to become bug hunters instead of focusing on their primary responsibilities [16].

To reduce the likelihood of opportunistic behavior among bug hunters, organizations are advised to exercise caution and maintain control over the process [17]. Instead of relying solely on bug hunters, organizations should integrate them into a collaborative effort to improve their cybersecurity practices [18].

Numerous studies have been conducted on bug bounty programs according to [11]. However, it is essential to understand the workings of bug hunters, their motivations, and the challenges encountered. Walshe and Simpson [19] propose that organizations can facilitate better collaboration between organizations and bug hunters. Therefore, relevant research is needed to identify the factors that drive bug hunters.

The current paper builds upon the Theory of Planned Behavior [20,21,22] to further understand the interplay between intrinsic and extrinsic motivational factors that affect the antecedents of behavioral attitudes of bug hunters. This study can further enhance our understanding of factors that will allow companies to better utilize and manage the power of the crowd in protecting the cybersecurity of their information assets. In the following sections, we first describe the relevant research and the conceptual development of the research model in the Background and Conceptual Development section. Then we discuss the methodology and data collection. The paper concludes with implications and avenues for future research.

2. Background and Conceptual Development

2.1. Overview of Relevant Literature

Among the numerous studies on the development and fostering of security cultures within organizations, focus on the information systems security culture is rather limited [22,23,24]. Work on this particular area includes [25] framework, which divides the information security landscape into four distinct cultures: motivation, avoidance, opportunism, and compliance. This framework is useful for comprehending the existing information security culture.

Along these lines, ref. [26] proposed an approach to assess information security culture by focusing on artifacts, espoused values, shared tacit assumptions, and information security knowledge. This result aligns with the findings of [27], who identified variations in security cultures among professionals in their study.

According to [28], culture encompasses the changes in behavior and practices within an organization over time; thus, it is crucial for organizations to implement information security components, as this has a significant impact on employees’ information security behavior. Moreover, ref. [29] emphasized the critical role of top management support in enhancing employee awareness. The structural and functional mechanisms in security governance are also significant influencing factors in identification of responsible parties and building a stronger information security culture [30,31].

Ref. [32] found that organizations with stricter penalties for non-compliance tend to have healthier cybersecurity cultures. Without clear consequences for non-compliance, individuals are more likely to engage in risky behavior [33]. Ref. [34] indicated that the level of punishment or reward has a significant effect on compliance intent. Furthermore, ref. [35] stated that the impact of a punishment or reward on compliance intent is greater when the reward level is low.

In examining the role of reward in cybersecurity culture, ref. [36] found that not all rewards have a positive effect on performance. Ref. [37] also showed that a reward can have a negative impact on compliance intent if the perceived reward for non-compliance is greater than the perceived reward for the organization. Individuals who view intrinsic rewards, such as time savings or ease of use, as a reward for policy noncompliance are more likely to exhibit inappropriate security behaviors [35,38].

Building upon the aforementioned studies on the topic, we believe understanding bug bounty hunters’ motivations and intentions and their impact of information security culture is a phenomenon worthy of further investigation.

2.2. Devlopment of the Conceptual Model

To further understand the factors that impact the intention to participate in bug hunting based on the behavior of bug bounty hunters, we first started with a focus group consisting of four experts to identify the relevant constructs for the study [39]. The duration of these consultations was 1 h, aimed at enhancing the quality of the study and incorporating valuable insights from experts.

Table 1 lists the participants of the consultation phase. Participants were selected based on their expertise in bug hunting. Each consultation session resulted in the identification of one or two constructs (which will be discussed while introducing the constructs in the following subsections). The Delphi method, as highlighted by [40], has several advantages over interviews in terms of time efficiency. This enabled a clear understanding of the subject matter over a short period. Ref. [41] argued that the Delphi method is suitable for cases where there is limited prior research, as is the case for factors influencing the behavioral intention to engage in bug hunting.

Table 1.

Consultation group of experts.

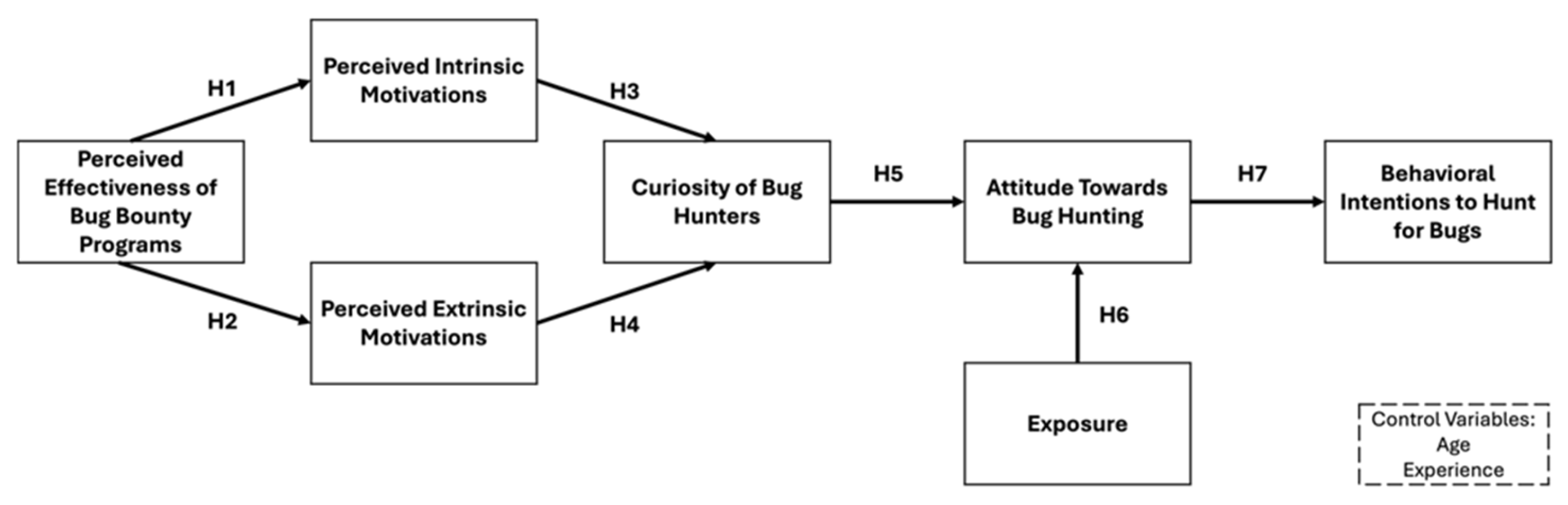

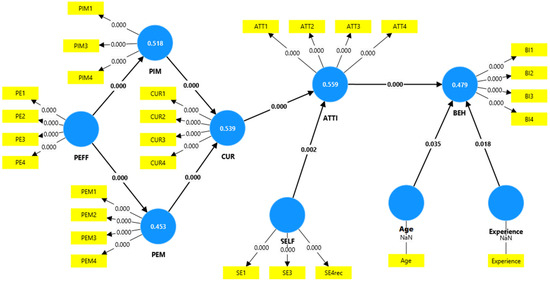

Following the consultation with experts and review of literature on similar topics we developed a research model rooted in [20] Theory of Planned Behavior and ref. [22] work on motivations that affect bug hunters’ behavior. To address potential bias, two bug bounty hunters were included in the study by forming two focus groups [42]. This approach served as an external validity check and helped minimize instrumentation and maturity errors [43] in the context of the study. As a result, a validated conceptual model was developed that is represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

The constructs and the hypotheses will be discussed in depth in the following sections.

2.2.1. Theory of Reasoned Action

The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) has been a strong foundation for explaining the behavioral attitudes and intentions of cybersecurity professionals, as demonstrated by [44]. According to the TRA, a person’s behavioral intention serves as the immediate precursor to their behavior [45]. Behavioral intentions are considered a component of an individual’s behavioral beliefs and their normative beliefs [44]. Behavioral beliefs are formed by an individual’s past experiences, while normative beliefs reflect their perception of subjective norms [46].

2.2.2. Perceived Effectiveness of Bug Bounty Programs

As discussed earlier, bug bounty programs are effective in persuading bug hunters to disclose vulnerabilities. The implementation of bug bounty programs, technologies, and tools can expedite the process of identifying vulnerabilities. Bug bounty hunters play a critical role in safeguarding organizations from potential threats [47]. A prime example would be to utilize cutting-edge tools such as a mitigation bypass [48].

The development of new tools and technologies has improved the effectiveness of bug detection [49]. Effectiveness refers to the extent to which the platform enhances users’ (in this case, bug hunters’) performance in conducting various activities, such as bug hunting.

In the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) by [50], the variable of performance expectancy serves as an indicator to determine the predictor’s intention to use. In the present study, perceived effectiveness serves a similar role as performance expectancy, which is used to determine whether bug bounty programs effectively modify the behavior of bug bounty hunters. To determine the impact of these bug bounty programs on the motivation of bug bounty hunters, the following two hypotheses are proposed:

H1:

Perceived effectiveness of bug bounty programs has an influence on perceived intrinsic motivation.

H2:

Perceived effectiveness of bug bounty programs has an influence on perceived extrinsic motivation.

2.2.3. Perceived Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations

The financial incentives of various entities can provide distinct motivations, such as organizations as well as external bug-bounty programs. It emerged from our consultation rounds that multiple bug bounty hunters could gain status through the ladder positions that they acquire. The more bugs they find, the higher is their rank on the ladder. This concept was established by HackerOne. Similarly, bug bounty hunters can lose their position on the ladder if they find too few bugs, experience bug rejections, or lack knowledge of new techniques, leading to a significant drop in bug findability. According to data from nearly 1700 bug hunters who operate through the HackerOne platform, approximately 14% of hackers are now able to rely on bounties that constitute 90 to 100% of their annual income. Furthermore, 25% of bounty hunters derive half of their income from finding bugs [51].

The motivation to scale up the ranks can be discussed from the perspective of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations [21,22,52]. The theories put forth by these researchers asserted that both constructs are necessary for a comprehensive understanding of motivation [52] contended that intrinsic and extrinsic motivations are separate entities, and according to [22], such motivations lead to curiosity-driven progression. Therefore, the third and fourth hypotheses are as follows:

H3:

Perceived intrinsic motivation has an influence on the curiosity of bug hunters.

H4:

Perceived extrinsic motivation has an influence on the curiosity of bug hunters.

2.2.4. The Curiosity of Bug Hunters

Discovering security vulnerabilities relies on the intellectual curiosity of a bug hunter. Ref. [53] defined curiosity as the degree to which an individual responds positively to something new or unusual. In most cases, if this occurs within the environment, bug hunters will investigate, explore, or even manipulate the phenomenon. Prior research has found that curiosity is a significant predictor of effectiveness, loyalty, accountability, and socialization [54]. Furthermore, several studies have shown a significant relationship between curiosity and age [55], gender [56], and socioeconomic status.

Curiosity has been identified as a significant factor influencing behavior in a variety of contexts. For instance, research in the marketing field has demonstrated that curiosity can enhance the effectiveness of online advertisements [57]. Additionally, curiosity has been found to impact product ownership [58] and behavioral intentions [59]. Ref. [60] further indicate that curiosity can lead to a greater intention to engage in a particular experience. Moreover, content shared by a group member can stimulate curiosity and have a positive impact on attitudes and behavioral intentions. Based on these findings, the fifth hypothesis was formulated as follows:

H5:

Curiosity of bug hunters influences the attitude towards the behavior.

2.2.5. The Curiosity of Bug Hunters

Exposure can significantly influence bug hunters’ decision-making, including whether to make ethical trade-offs. Research has shown that individuals with a higher exposure ratio are more likely to make ethical/social trade-offs in their options, whereas those with a lower exposure probability tend to make unpredictable choices [61,62,63].

Recent studies have widely examined the relationship between exposure and attitude toward behavior [64]. Similarly, ref. [65] established a relationship correlation between adolescent exposure to online self-presentation and behavior, focusing on the impact of digital exposure on personal attitudes and actions. Hence, exposure is a crucial factor for bug hunters when making decisions:

H6:

Exposure influences the attitude towards the behavior.

2.2.6. Attitude Towards the Behavior

The extent to which an action is perceived as positive or negative is determined by one’s attitude toward it. This attitude is shaped by a collection of beliefs about the relationship between behavior and its consequences [20]. Thus, we posit that bug hunters’ behavior in relation to bug hunting is influenced by the perceived attitude toward bug hunting.

Perceived behavioral control can vary depending on context and situational factors [66]. For instance, if a hacker discovers software vulnerability while experimenting with it at home (as discussed during a consultation session with experts), their behavioral intention to hunt may be further motivated by their positive attitude towards this activity [44]. An individual’s view of themselves as part of a larger community is crucial to the hacker’s identity and attitude. This perspective is also essential for bug hunters, as it can affect their behavioral intention to participate in bug hunting [45]. The seventh hypothesis is thus stated as follows:

H7:

Attitude towards the behavior influences the behavioral intention to bug hunt.

3. Methodology

3.1. Survey Development

The primary goal of this study was to gather empirical data on the relationship between bug hunters’ motivation and their behavior in the context of bug bounty programs. The survey was designed to target bug hunters worldwide and included control variables such as age and experience. The survey questions were based on reputable academic papers and were modified to suit this research. Appendix A and Appendix B provides a detailed breakdown of the variables, construct validation, their definitions, survey questions, and corresponding sources.

Several experts reviewed the survey that were not part of the initial expert consultation group. Their practical perspective and critical analysis of the questions and survey design helped in reducing potential biases in the survey design.

3.2. Data Collection and Survey Distribution

The survey was executed using Qualtrics, with the data declared proprietary to the researcher. Approximately 600 bug bounty hunters were contacted through LinkedIn, Telegram, and hacker forums and we received 386 completed responses.

In the subject pool, 95 were between ages of 18 and 24 and 148 were between 25 and 34 years old. The remainder of 141 subjects were over 35 years old. As for location, 190 respondents were from the United States, 74 from the Netherlands, 70 from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, 31 from Canada, 6 from India, and few participants from other countries. We recognize that the sample may not be a comprehensive representative of the global audience. Our focus was mostly limited to countries where English was either the official language of the state or the world of business. Appendix B offers the breakdown of the sample.

4. Results

4.1. Survey Items

Smart PLS was used for testing of our hypotheses. We also conducted factor analysis was used to assess the validity of the survey. The detailed analysis is available in Appendix A. As reported in Table A1 (Appendix A), our constructs had Cronbach’s alpha of over 0.7 and the extracted average variance of items, which represent the average value of the squared factor, were greater than 0.5, indicating that no construct required improvement.

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

For the first hypothesis, we examined the relationship between the perceived effectiveness of bug bounty programs and perceived intrinsic motivation. Considering the p-value < 0.001, there was sufficient evidence to support the hypothesis.

The second hypothesis was also supported with the p-value < 0.001, corroborating the impact of perceived effectiveness of bug bounty programs on perceived extrinsic motivations. Similarly, the third hypothesis regarding intrinsic motivations was also supported (p-value < 0.001).

Furthermore, the relationships between extrinsic and intrinsic motivations and curiosity (H3 and H4) were also significant (p-value < 0.001). The data supported the fifth hypothesis regarding curiosity of bug hunters’ influence on the attitude towards behavior as well. The relationship between exposure and attitudes towards behavior was also statistically significant with a p-value of 0.002. Finally, we found the influence of attitude towards behavior to be statistically significant (p-value < 0.001). Table 2 summarizes the hypotheses tests.

Table 2.

Hypotheses tests.

5. Contributions and Discussions

5.1. Practical Implications

There has been a dearth of research on the behavioral motivators of bug hunters. Our work contributes to further understanding of the bug hunting phenomenon. This study touched upon the psychological and economic aspects of bug hunters.

From a practical perspective, many organizations, including large platform builders who value high product quality, struggle with bugs. Governments and organizations play a crucial role in improving software, particularly in terms of security. It is in the best interests of society that major software providers such as Microsoft minimize vulnerabilities. Given the widespread use of these platforms, the impact of a breach can be far-reaching and affect everyone. Platform builders may benefit from engaging bug hunters to identify and address software bugs, thereby improving the overall software quality.

Governments also play a role in establishing necessary infrastructure. Those who report such vulnerabilities, whether bug bounty hunters or individuals who have engaged in criminal activities and wish to seek redemption, should be rewarded and recognized for their efforts. It is crucial for governments to provide bug hunters with a guarantee of non-prosecution.

5.2. Limitations

Approaching the bug bounty hunters’ community is challenging as they may prefer to minimize interactions with outsiders. This was evidenced by various discussions with the panel of experts. We studied general bug hunters and did not focus on specific settings of governments or organizations. This could have led to a more generalized rather than specific understanding of this subject matter.

The majority of respondents originated from Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States and the Netherlands, resulting in a sample that lacks comprehensive representation from regions such as Asia, Africa, and South America. This geographical concentration presents a limitation to the generalizability of the study findings, particularly in contexts where cultural, economic or regulatory differences may shape behavior. Moreover, while self-reported measures are appropriate proxies for actual behavior, the performance of an action can only be observed in a field study.

5.3. Future Research

Focusing on motivations of bug hunters, it is worthwhile to further investigate the elements that may directly or indirectly augment or diminish their motivations. The ethical implications of a hacker’s transition from malicious to constructive roles could also be studied in the future. The “fraud triangle”, which comprises pressure, opportunity, and rationalization, can be employed to examine why certain individuals cross ethical limitations while others do not. Research on the factors that shape an individual’s moral behavior and the conditions under which they may shift from ethical to unethical conduct, can be applied to extend our understanding of bug hunters’ psyche.

Groups such as Anonymous have engaged in digital resistance [67], digital disobedience [68], and digital activism [69], utilizing hacktivism as a means of expression. Ref. [70] defines hacktivism as the commission of an unauthorized digital intrusion with the intent of expressing a political or moral stance, emphasizing that it is nonviolent in nature. However, when ethical hackers endeavor to influence political objectives, they engage in a form of coercion that obscures the distinction between ethical protest and disruptive force. Moreover, it would be interesting to explore the process by which individuals who have engaged in unethical activities transition back to ethical behavior. Although this topic is typically examined from a sociological standpoint, it may also be approached from a cyber perspective. Overall, examining the psychology of individuals who seek the dark side or those who return to ethical behavior, as well as the ethical implications of their actions, would make an engaging area of research.

A study by [71] sheds light on these ethical dilemmas by asking bug bounty hunters: “Do you have options to sell security bugs in black/grey markets?”. Responses varied, with some stating that they would sell vulnerabilities if offered a high price, while the majority indicated a preference for selling directly to vendors. Interestingly, while financial incentives play a role, many emphasized that feeling valued and appreciated by organization was an even stronger motivator [72]. This finding underscores the ethical complexities within bug bounty programs and the factors influencing bug bounty hunters’ decisions.

Governments have a fundamental responsibility to protect individuals, uphold legal frameworks, and intermediate disagreements. To maintain control in an increasingly digital landscape, they must collaborate closely with organizations and coordinate efforts effectively. Beyond legal frameworks, policies serve as critical instruments in defining enforcement strategies and shaping the behavior of digital actors [70]. These legal frameworks, which are already recognized as valuable by the political community and embedded within society as instruments of justice, can inadvertently shape the actions of hackers. In such cases, hackers may invoke the law as it stands, acting in a manner that aligns with the intended role of the state. This dynamic creates a more nuanced and complex regulatory environment in which hackers operate, shaped by the existing legal and policy provisions that remain in place despite lapses in enforcement.

Building on this, governments and platform providers can potentially decrease obstacles for individuals to exhibit ethical behavior by implementing specific measures. Examining distinctions across continents, countries, and even cities could enable researchers to discover new findings and acquire a more profound understanding of the factors that contribute to individuals’ transition from unethical to ethical behavior in the virtual realm.

According to [47], bug bounty programs are often perceived as a risky approach to improving security, as organizations invite a large group of anonymous and independent bug hunters from around the world to test their software systems. Some organizations may fear that certain bug hunters could damage production systems or steal user data while conducting vulnerability research. Conversely, bug bounty hunters may worry about facing legal consequences for vulnerability research and disclosure [72].

Bug bounty hunters are not always familiar with the correct procedures, which increases the risk of legal repercussions or criminal penalties [73]. In Spain, for example, bug bounty hunters are well integrated into the governance framework. Therefore, it would be beneficial to provide them with a legal framework regulating their activities. Experts indicate that such a framework would obviously formalize the de facto laws on bug bounty programs already existing in other countries. Nations such as France and the Netherlands have already implemented active Coordinated Vulnerability Disclosure (CVD) policies that include protections for bug bounty hunters.

France offers a particularly illustrative example. Under its CDV framework, Article 47 L. 2321-4 exempts individuals who report vulnerabilities in good faith to Agence nationale de la sécurité des systèmes d’information (ANSSI) from the legal obligation outlined in Article 40 of the Code de procédure pénale [73]. This provision protects those who disclose security vulnerabilities related to automated data-processing systems.

Similarly, the Netherlands has implemented a CVD policy with positive results, offering full protection for bug bounty hunters. While most EU member states have yet to introduce similar frameworks, several are actively exploring their implementation, reflecting a broader shift towards structured vulnerability disclosure policies.

Outside the EU, countries such as Japan and the United States have taken proactive steps in this area. In 2016, the US introduced a CVD policy alongside its bug bounty programs. In Japan, CVD aligns with [74] ensuring that once a vulnerability is known to vendors, a public announcement is made in the Japanese Vulnerability Notes [75]. This structured approach has led to a significant increase in vulnerability reports in recent years. Given these developments, further research could explore how countries can learn from each other in established legal frameworks for bug bounty hunters. A comparative analysis of national approaches may provide insights into best practices for ensuring legal protection while maintaining security standards.

6. Conclusions

This study is an attempt in advancing our understanding of the motivational drivers and behavioral intentions of bug bounty hunters. By corroborating all proposed hypotheses, our work emphasizes that both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, alongside perceived effectiveness of platforms, curiosity, exposure, and overall attitude, play a crucial role in shaping the behavior of bug bounty hunters. These findings can offer practical insights for devising more effective bug bounty programs by aligning incentives with the diverse intrinsic and extrinsic motivations of bug hunters.

Moreover, one can emphasize the importance of creating platforms that are perceived as effective by bug hunters. The design of the platform, along with the right mix of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations can further increase the involvement of third-party bug hunters in vulnerability discovery. Furthermore, the demonstrated significance of curiosity and exposure as drivers of behavior suggests that organizations should focus on cultivating paths for personal and professional development.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Cronbach’s alpha and Average Variance Extracted.

Table A1.

Cronbach’s alpha and Average Variance Extracted.

| Construct | Cronbach’s Alpha | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|

| Curiosity (CUR) | 0.815 | 0.644 |

| Perceived intrinsic motivation (PIM) | 0.837 | 0.670 |

| Behavioral intention (BE) | 0.781 | 0.603 |

| Perceived extrinsic motivation (PEM) | 0.807 | 0.634 |

| Attitude towards behavior (Atti) | 0.802 | 0.627 |

| Perceived effectiveness of bug bounty programs (PEFF) | 0.752 | 0.667 |

| Exposure (SE) | 0.531 | 0.515 |

Table A2.

Heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT).

Table A2.

Heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT).

| ATTI | BEH | CUR | PEFF | PEM | PIM | SELF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATTI | |||||||

| BEH | 0.819 | ||||||

| CUR | 0.921 | 0.821 | |||||

| PEFF | 0.825 | 0.844 | 0.850 | ||||

| PEM | 0.828 | 0.846 | 0.779 | 0.827 | |||

| PIM | 0.893 | 0.840 | 0.897 | 0.908 | 0.787 | ||

| SELF | 0.714 | 0.882 | 0.757 | 0.782 | 0.770 | 0.692 |

Table A3.

Fornell–Larcker criterion.

Table A3.

Fornell–Larcker criterion.

| ATTI | BEH | CUR | PEFF | PEM | PIM | SELF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATTI | 0.802 | ||||||

| BEH | 0.681 | 0.819 | |||||

| CUR | 0.736 | 0.667 | 0.777 | ||||

| PEFF | 0.676 | 0.704 | 0.680 | 0.796 | |||

| PEM | 0.671 | 0.696 | 0.619 | 0.673 | 0.792 | ||

| PIM | 0.704 | 0.675 | 0.692 | 0.720 | 0.615 | 0.817 | |

| SELF | 0.474 | 0.587 | 0.488 | 0.513 | 0.507 | 0.441 | 0.717 |

Table A4.

Structural model assessment results.

Table A4.

Structural model assessment results.

| Original Sample | Sample Mean | Standard Deviation | T Statistic | p-Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATTI -> BEH | 0.657 | 0.659 | 0.038 | 17.518 | <0.001 |

| Age -> BEH | 0.086 | 0.086 | 0.041 | 2.108 | 0.035 |

| CUR -> BEH | 0.662 | 0.661 | 0.054 | 12.189 | <0.001 |

| Experience -> BEH | 0.092 | 0.092 | 0.039 | 2.371 | 0.018 |

| PEFF -> PEM | 0.673 | 0.674 | 0.034 | 19.535 | <0.001 |

| PEFF -> PIM | 0.720 | 0.722 | 0.026 | 28.066 | <0.001 |

| PEM -> CUR | 0.311 | 0.312 | 0.063 | 4.930 | <0.001 |

| PIM -> CUR | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.060 | 8.280 | <0.001 |

| SELF -> ATTI | 0.151 | 0.154 | 0.050 | 3.042 | 0.002 |

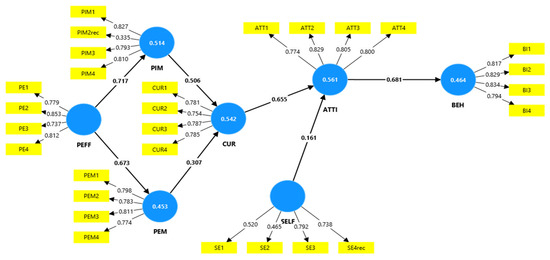

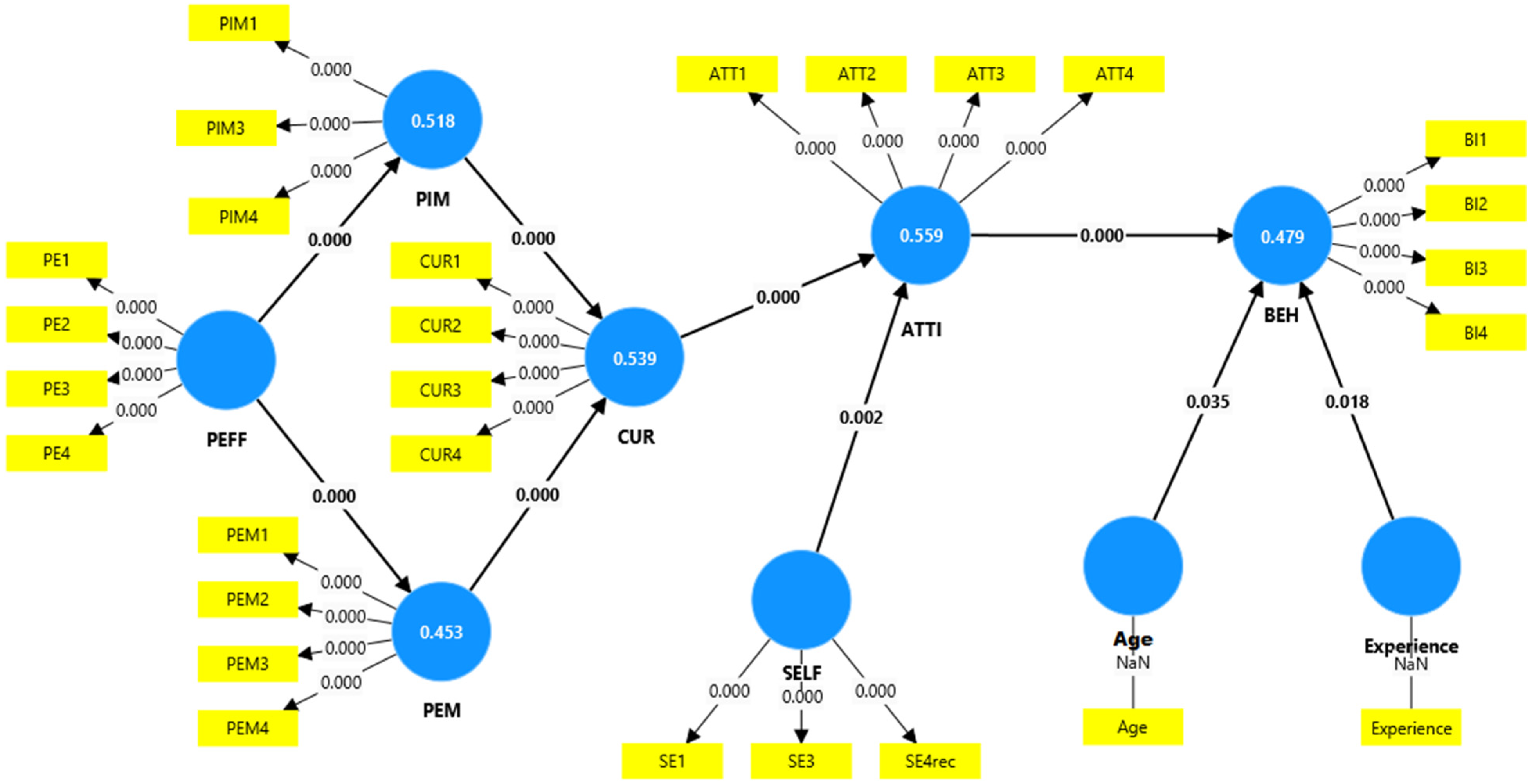

Figure A1 (Appendix A): Model 1 depicts all factor values and loadings between the variables. The values between PEFF and PIM are somewhat high, with a value of 0.717. The value between PEFF and PEM is also relatively high at 0.673, as is the value between PIM and CUR at 0.506. The value between PEM and CUR is 0.307, while the value between CUR and ATTI is 0.655. The value between SELF and ATTI is 0.161, and the value between ATTI and BEH is 0.681.

Regarding SE2, the factor value is quite different, at 0.465, whereas PIM2rec is 0.335. While the load is much better for all other factor values, with values above 0.5, 0.6, and even above 0.7, we want to see that the mean charge squared of the latent variables is much higher than the relationship between the two of the blue dots. In examining Figure A1 (Appendix A), we aimed to enhance the PIM. As depicted in Appendix A, PIM1 is 0.827, PIMrec is 0.335, PIM3 is 0.793, and PIM4 is 0.810. Ideally, the average charge should be approximately 0.7 or higher. To achieve this, PIMrec is removed from the analysis.

With regard to exposure, the values were high except for SE1 and SE2. Consequently, the lowest value, SE2 (0.465), was removed. This improved the exposure load. Although the Cronbach’s alpha for exposure is 0.531, which is below the desired threshold of 0.7, it cannot be increased without compromising narrative strength. Therefore, we continued without SE2. Table A1 (Appendix A) indicates that the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for all items was above 0.5, and the Cronbach’s alphas for all items, except exposure (0.531), were above 0.7.

Figure A1.

Model 1 (all items).

Figure A1.

Model 1 (all items).

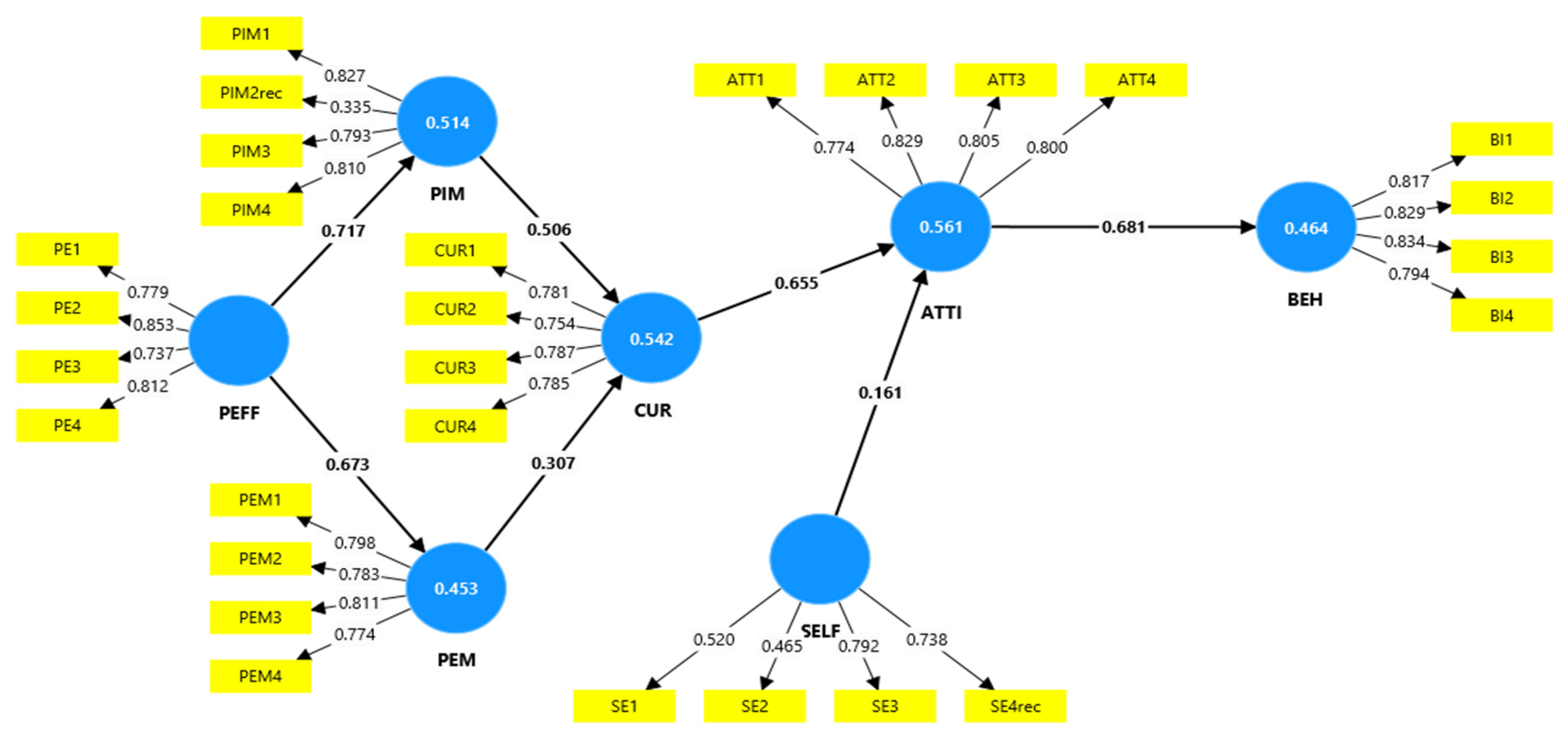

Figure A2.

Revised model—hypothesis testing; bootstrapping direct effect (bootstrap: 5000 subsamples).

Figure A2.

Revised model—hypothesis testing; bootstrapping direct effect (bootstrap: 5000 subsamples).

Appendix B

Table A5.

Survey instrument.

Table A5.

Survey instrument.

| Variable | Definition | Survey Questions | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived effectiveness of bug bounty programs | The extent to which a person believes that using a specific system will improve their job performance. | My job would be difficult to perform without bug bounty programs. The use of bug bounty programs was highly effective. Bug bounty programs are perceived to be effective by bug hunters. I enjoyed being a member of bug bounty programs. | [76] [77] |

| Perceived intrinsic motivation | Participants’ desire to continue working on the task, level of interest in the activity, perceived level of challenge, and task satisfaction. | I like bug hunting. I hate bug hunting. I wish we had more bug bounty programs. In the future I would like to learn more about bug hunting. | [78] [79] |

| Perceived extrinsic motivation | Obtaining satisfaction that is independent of the activity’s content. | I am keenly aware of the income goals I have for myself if I learn business and technical knowledge about bug hunting. I am strongly motivated by the money I can earn if I learn business and technical knowledge about bug hunting. I am strongly motivated by the recognition I can earn from other people for learning business and technical knowledge about bug hunting. I have to feel that I am earning something for learning business and technical knowledge about bug hunting. | [80] [81] |

| Curiosity of bug hunters | The extent to which an individual’s sensory and cognitive curiosity is piqued. | Interacting with bug hunters makes me curious. Finding bugs makes me curious. Finding bugs arouses my imagination. I am curious to find other bug hunters | [82] [81] |

| Attitude towards the behavior | Attitude toward bug hunters. | When I address bugs with bug hunters, I do something good for society. When I address bugs with bug hunters, I enjoy it. When I address bugs with bug hunters, I do something which will satisfy myself. When I address bugs with bug hunters, bug hunters will be pleased with it. | [83] |

| Exposure | The perception of a bug hunter that information and technology resources at work are vulnerable to security risks and threats. | I have been hacked at least once. I have never been hacked. I refuse to believe that I can be hacked. I have a strategy for not being exposed. | [84] |

| Behavioral intention to bug hunt | The extent to which a person has made conscious plans to perform or refrain from performing a specific future behavior. | I intend to continue using bug bounty programs. I predict I will continue using bug bounty programs. If everything goes as I plan, I will bug hunt daily. I intend to bug hunt daily. | [85] |

Table A6.

Experience distribution.

Table A6.

Experience distribution.

| Experience (Years) | Count |

|---|---|

| Almost none | 151 |

| Somewhat | 177 |

| Medium | 44 |

| Much | 12 |

| A lot of experience | 2 |

Table A7.

Age distribution.

Table A7.

Age distribution.

| Age Group | Count |

|---|---|

| 18–24 | 95 |

| 25–34 | 148 |

| 35+ | 141 |

Table A8.

Country distribution.

Table A8.

Country distribution.

| Country | Count |

|---|---|

| United States | 190 |

| Netherlands | 74 |

| United Kingdom | 70 |

| Canada | 31 |

| India | 6 |

| Other countries | 15 |

References

- Al-Somali, S.A.; Saqr, R.R.; Asiri, A.M.; Al-Somali, N.A. Organizational cybersecurity systems and sustainable business performance of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Saudi Arabia: The mediating and moderating role of cybersecurity resilience and organizational culture. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce, D.G. Cybersecurity and platform competition in the cloud. Comput. Secur. 2020, 93, 101774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdemir, N.; Lawless, C.J. Exploring the human factor in cyber-enabled and cyber-dependent crime victimisation: A lifestyle routine activities approach. Internet Res. 2020, 30, 1665–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Rachelle, B.; Rens, S. Protecting organizational competitive advantage: A knowledge leakage perspective. Comput. Secur. 2014, 42, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asbaş, C.; Tuzlukaya, Ş. Cyberattack and cyberwarfare strategies for businesses. In Conflict Management in Digital Business; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2022; pp. 303–328. [Google Scholar]

- McFadden, C. The Origin of the Term ‘Computer Bug’; Interesting Engineering, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://interestingengineering.com/innovation/the-origin-of-the-term-computer-bug (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- McLaughlin, M.D.; Gogan, J. Challenges and best practices in information security management. MIS Q. Exec. 2018, 17, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Malladi, S.S.; Subramanian, H.C. Bug bounty programs for cybersecurity: Practices, issues, and recommendations. IEEE Softw. 2019, 37, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltsik, J. The life and times of cybersecurity professionals 2018. ESG Res. Rep. 2019, 2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Grossklags, J.; Liu, P. An empirical study of web vulnerability discovery ecosystems. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Denver, CO, USA, 12–16 October 2015; pp. 1105–1117. [Google Scholar]

- Laszka, A.; Zhao, M.; Malbari, A.; Grossklags, J. The rules of engagement for bug bounty programs. In Proceedings of the Financial Cryptography and Data Security: 22nd International Conference, FC 2018, Nieuwpoort, Curaçao, 26 February–2 March 2018; Revised Selected Papers 22. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 138–159. [Google Scholar]

- Arshad, J.; Talha, M.; Saleem, B.; Shah, Z.; Zaman, H.; Muhammad, Z. A Survey of Bug Bounty Programs in Strengthening Cybersecurity and Privacy in the Blockchain Industry. Blockchains 2024, 2, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winder, D. These Hackers Have Made $100 Million and Could Earn $1 Billion by 2025. Forbes, 29 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Durward, D.; Blohm, I.; Leimeister, J.M. The nature of crowd work and its effects on individuals’ work perception. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2020, 37, 66–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Straub, D.; Zhang, P.; Cai, Z. How Trust Leads To Commitment On Microsourcing Platforms: Unraveling The Effects of Governance and Third-Party Mechanisms on Triadic Microsourcing Relationships. MIS Q. 2021, 45, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda, R.; Phiri, J.; Nyirenda, M.; Kabemba, M.M. Technological Paradox of Hackers Begetting Hackers: A Case of Ethical and Unethical Hackers and their Subtle Tools. Zamb. ICT J. 2019, 3, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Banna, M.; Benatallah, B.; Schlagwein, D.; Bertino, E.; Barukh, M.C. Friendly Hackers to the Rescue: How Organizations Perceive Crowdsourced Vulnerability Discovery. In Proceedings of the PACIS, Yokohama, Japan, 26–30 June 2018; p. 230. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, L. Collaborating with bounty hunters: How to encourage white hat hackers’ participation in vulnerability crowdsourcing programs through formal and relational governance. Inf. Manag. 2022, 59, 103648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walshe, T.; Simpson, A. An empirical study of bug bounty programs. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 2nd International Workshop on Intelligent Bug Fixing (IBF), London, ON, Canada, 18 February 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M. Motivational synergy: Toward new conceptualizations of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in the workplace. Hum. Res. Manag. Rev. 1993, 3, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Pratt, M.G. The dynamic componential model of creativity and innovation in organizations: Making progress, making meaning. Res. Organ. Behav. 2016, 36, 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwa, E.; Loock, M.; Kritzinger, E. The determinants of an information security policy compliance culture in organisations: The combined effects of organisational and behavioural factors. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2022, 30, 583–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, F.; Åström, J.; Karlsson, M. Information security culture–state-of-the-art review between 2000 and 2013. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2015, 23, 246–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnesk, D.; Lindström, J. Shaping security behaviour through discipline and agility: Implications for information security management. Inf. Manag. Comput. Secur. 2011, 19, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okere, I.; Van Niekerk, J.; Carroll, M. Assessing information security culture: A critical analysis of current approaches. In 2012 Information Security for South Africa; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran, S.; Rao, S.V.; Goles, T. Information security cultures of four professions: A comparative study. In Proceedings of the 41st Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS 2008), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 7–10 January 2008; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2008; p. 454. [Google Scholar]

- Da Veiga, A.; Eloff, J.H. A framework and assessment instrument for information security culture. Comput. Secur. 2010, 29, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, P.A.; Maynard, S.B.; Ruighaver, A.B. Understanding organizational security culture. In Proceedings of the PACIS2002, Tokyo, Japan, 5–9 July 2002; p. 158. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, K.; Ruighaver, A.B.; Maynard, S.B.; Ahmad, A. Security governance: Its impact on security culture. In Proceedings of the 3rd Australian Information Security Management Conference, Perth, Australia, 30 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nicho, M. A process model for implementing information systems security governance. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2018, 26, 10–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, K.M.; Young, E.; Butavicius, M.A.; McCormac, A.; Pattinson, M.R.; Jerram, C. The influence of organizational information security culture on information security decision making. J. Cogn. Eng. Decis. Mak. 2015, 9, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, B.; Hsu, C. The role of abusive supervision and organizational commitment on employees’ information security policy noncompliance intention. Internet Res. 2020, 30, 1383–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ramamurthy, K.; Wen, K.W. Organizations’ information security policy compliance: Stick or carrot approach? J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2012, 29, 157–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaspie, H.W.; Karwowski, W. Human factors in information security culture: A literature review. In Proceedings of the Advances in Human Factors in Cybersecurity: Proceedings of the AHFE 2017 International Conference on Human Factors in Cybersecurity, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 17−21 July 2017; The Westin Bonaventure Hotel: Los Angeles, CA, USA; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 8, pp. 269–280. [Google Scholar]

- Farahmand, F.; Atallah, M.J.; Spafford, E.H. Incentive alignment and risk perception: An information security application. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2012, 60, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, A.; Siponen, M.; Pahnila, S. Motivating IS security compliance: Insights from habit and protection motivation theory. Inf. Manag. 2012, 49, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganye, D.; Smith, K. Examining the effects of cognitive load on information systems security policy compliance. Internet Res. 2024, 35, 380–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakani, F.; Sheerani, M. How to gain consensus from a group of non-experts—An educationist perspective on using the Delphi technique. Dev. Learn. Organ. Int. J. 2012, 26, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, R.; Nelson, R.R.; Chin, W.W.; Land, L. The Delphi Method Research Strategy in Studies of Information Systems. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2015, 37, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarabiat, A.; Ramos, I. The Delphi Method in Information Systems Research (2004–2017). Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2019, 17, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, M.K.; Draugalis, J.R. Establishing the internal and external validity of experimental studies. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2001, 58, 2173–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, M. Improving External Validity May Jeopardize Internal Validity. Anesthesiology 2019, 130, 508–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, K.D. Motivation and Demotivation of Hackers in The Selection of A Hacking Task—A Contextual Approach. Ph.D Dissertation, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Madden, T.J.; Ellen, P.S.; Ajzen, I. A Comparison of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Theory of Reasoned Action. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 18, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Madden, T. Prediction of Goal-Directed Behavior: Attitudes, Intentions, and Perceived Behavioral Control. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 22, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Laszka, A.; Grossklags, J. Devising effective policies for bug-bounty platforms and security vulnerability discovery. J. Inf. Policy 2017, 7, 372–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluoha, O.U.; Yange, T.S.; Okereke, G.E.; Bakpo, F.S. Cutting Edge Trends in Deception Based Intrusion Detection Systems—A Survey. J. Inf. Secur. 2021, 12, 250–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransbotham, S.; Mitra, S.; Ramsey, J. Are Markets for Vulnerabilities Effective? MIS Q. 2012, 36, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chickowski, E. You Break, It, They Buy It: Economics, Motivations Behind Bug Bounty Hunting. Dark Reading. Available online: https://www.darkreading.com/threat-intelligence/you-break-it-they-buy-it-economics-motivations-behind-bug-bounty-hunting (accessed on 19 January 2018).

- Herzberg, F. Work and the Nature of Man; Ty Crowell: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Maw, W.H.; Maw, E.W. Self-appraisal of Curiosity. J. Educ. Res. 1968, 61, 462–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, G. The psychology of curiosity: A review and reinterpretation. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 116, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidler, D.C.; Curiosity, I.S.B. (Eds.) Motivation in Education; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Stoner, S.B.; Spencer, W.B. Age and Sex Differences on the State-Trait Personality Inventory. Psychol. Rep. 1986, 59, 1315–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, S.; Soman, D. Managing the power of curiosity for effective web advertising strategies. J. Advert. 2002, 31, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoham, A.; Pesämaa, O. Gadget loving: A test of an integrative model. Psychol. Mark. 2013, 30, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, K.M.; Fombelle, P.W.; Sirianni, N.J. Shopping under the influence of curiosity: How retailers use mystery to drive purchase motivation. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1028–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V.L.; Vinuales, G. Understanding the role of social influence in piquing curiosity and influencing attitudes and behaviors in a social network environment. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddux, J.E.; Rogers, R.W. Protection motivation and self-efficacy: A revised theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 19, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astremska, I. Influence of Self-Attitude and Attitude to Others on the Success of Representatives of Professions “Person-Person” Type; Psychology Series; Scientific Notes of Ostroh Academy National University: Ostroh, Oekraïne, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Son, J.Y.; Suh, K.S. Fear appeal cues to motivate users’ security protection behaviors: An empirical test of heuristic cues to enhance risk communication. Internet Res. 2022, 32, 708–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechler, C.J.; Tormala, Z.L.; Rucker, D.D. The attitude–behavior relationship revisited. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 32, 1285–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oosten, J.M.; Peter, J.; Boot, I. Exploring associations between exposure to sexy online self-presentations and adolescents’ sexual attitudes and behavior. J. Youth Adolesc. 2015, 44, 1078–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehn, A.; Mueller, M. Analyzing Bug Bounty Programs: An Institutional Perspective on the Economics of Software Vulnerabilities. In 2014 TPRC Conference Paper; SSRN: Arlington, VA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Delmas, C. Is hacktivism the new civil disobedience? Raisons Polit. 2018, 69, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuerman, W.E. Digital disobedience and the law. New Political Sci. 2016, 38, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauter, M. The Coming Swarm: DDOS Actions, Hacktivism, and Civil Disobedience on the Internet; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2014; p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- Bellaby, R.W. An ethical framework for hacking operations. In The Ethics of Hacking; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2023; pp. 32–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hata, H.; Guo, M.; Babar, M.A. Understanding the heterogeneity of contributors in bug bounty programs. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement (ESEM), Toronto, ON, Canada, 9–10 November 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães, J.P. Bug Bounties: Ethical and Legal Aspects. In Legal Developments on Cybersecurity and Related Fields; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 235–250. [Google Scholar]

- Del-Real, C.; Rodriguez Mesa, M.J. From black to white: The regulation of ethical hacking in Spain. Inf. Commun. Technol. Law 2022, 32, 207–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 29147:2018; Information Technology—Security Techniques—Vulnerability Disclosure (2nd ed.). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/72311.html (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Japan Computer Emergency Response Team Coordination Center (JPCERT/CC) and Information-Technology Promotion Agency (IPA). Japan Vulnerability Notes (JVN). Available online: https://jvn.jp/en/ (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Jim, S.; Gallupe, R.B. Using Electronic Meeting Technology to Support Economic Policy Development in New Zealand: Short-Term Re-sults. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1993, 10, 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Alan, R.D.; Valacich, J.S.; Connolly, T. Process Structuring in Electronic Brainstorming. Inf. Syst. Res. 1996, 7, 268–277. [Google Scholar]

- Mossholder, K.W. Effects of externally mediated goal setting on intrinsic motivation: A labora-tory experiment. J. Appl. Psychol. 1980, 65, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W. Self- De-Scription Questionnaire II: A Theoretical and Empirical Basis for the Measurement of Multiple Dimensions of Adolescent Self-Concept: An Interest Manual and a Research Monograph; Psychological Corporstion: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dong-Gil, K. Anteced-ents of knowledge transfer from consultants to clients in enterprise system implementations. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 59–85. [Google Scholar]

- Amabile, T. The Work Preference Inventory: Assessing Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motiva-tional Orientations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 66, 950–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritu, A.; Kara-hanna, E. Time Flies When You’re Having Fun: Cognitive Absorption and Beliefs About Information Technology Usage. MIS Q. 2000, 24, 665–694. [Google Scholar]

- Leurs, M.T.; Bessems, K.; Schaalma, H.P.; de Vries, H. Schaal-ma. Focus points for school health promotion im-provements in Dutch primary schools. Health Educ. Res. 2007, 22, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Weintraub, J.K. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warshaw, P.R. Disentangling behavioral intention and behavioral expectations. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 21, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).