Abstract

China’s media governance policies play a crucial role in shaping media ecology and promoting the modernization of national governance capacity. This study employed the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) model and co-occurrence network analysis to systematically analyze the thematic content of national-level media governance policies issued in China between 1996 and 2024, and to examine the evolution of policy themes from a triple logical synergy perspective. In consideration of the socio-economic context and governance issues, this study has categorized the evolution of media governance policies into four distinct phases. This study used the LDA model to extract high-frequency words and built a co-occurrence network to explore the structural relationship among these words, with a synergy framework to analyze the thematic evolution across periods. The findings indicate that China’s media governance policies over the past three decades have been the result of stage-by-stage adjustments under the synergistic influences of technological drivers, social demands, and governance philosophies. Media governance constitutes a pivotal component in the modernization of China’s national governance capacity. A comprehensive analysis of the evolution of policy themes reveals the internal pattern of media governance in China.

1. Introduction

Media governance, as a conceptual framework for regulating media ecosystems, exhibits divergent evolutionary trajectories between Western liberal democracies and China’s state-led model. While Western scholarship predominantly conceptualizes media governance through the prism of market autonomy and Fourth Estate ideals [1,2,3], China’s paradigm has undergone a fundamental reconfiguration since the 2013 articulation of national governance modernization and the elevation of media convergence as a strategic priority in 2015. The distinctiveness of China’s media governance system is attributable to its institutional logic, whereby the system functions not only as a regulatory mechanism, but also as an infrastructural pillar for political communication, social stability, and ideological security [4,5]. This distinction is especially salient when viewed within the broader context of East Asia’s increasingly de-regionalized media landscape, a phenomenon that has been documented by several scholars [6]. In this context, the analysis of policy texts becomes imperative, as these documents serve to consolidate the evolving governance rationality. By examining these cases, we can gain insight into the translation of macro-level political philosophies into meso-level institutional designs and micro-level operational norms [7,8,9,10,11]. A historical perspective is imperative for a comprehensive understanding of media governance in China. These texts can be regarded as the primary conduits of governance philosophies, regulatory measures, and developmental guidelines, offering critical insights into the historical conceptualization, implementation, and adaptive evolution of media governance in China. They present an analytical roadmap that elucidates both the enduring principles and dynamic transformations of regulatory frameworks within the distinct politico–social–technological matrix at the national level.

Since the foundational 1996 Circular of the General Office of the CPC Central Committee and the General Office of the State Council on Strengthening the Management of the Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television Industries, and the 1997 Code of Professional Ethics for Chinese Journalists issued by the All-China Journalists Association, China’s media governance framework has evolved through four distinct phases. The early 2000s signaled the inception of a regulatory framework for the Internet, as evidenced by the 2005 Regulations on the Administration of Internet News Information Services (jointly issued by the State Council Information Office and the Ministry of Information Industry). In 2012, a nationwide campaign was initiated to combat journalistic extortion, with the objective of addressing paid news and extortionate reporting practices to ensure the credibility of the media. A strategic shift toward media convergence emerged in 2015, epitomized by Guiding Opinions of the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television on Promoting Integrated Development of Traditional Publication and Emerging Publication, which institutionalized cross-platform integration of traditional and digital media. The most recent phase places a focus on algorithmic content governance, notably exemplified by the ongoing Qinglang Campaign, which specifically targets unethical practices by self-media accounts that exploit algorithmic systems for traffic manipulation and unscrupulous commercial gain.

This study is guided by three central objectives. First, it seeks to systematically analyze 28 nationally significant media governance policies from the years 1996 to 2024 using Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), a computational text mining technique designed to identify policy themes and their evolutionary patterns at specific stages without compromising the fidelity of high-dimensional terms. By constructing co-word networks for each period, we further validate and reveal the structural relationships between keywords. Second, it employs a tri-logic synergistic framework of technological drivers, societal demands, and governance philosophy to theoretically analyze the dynamic evolution of these themes. Finally, it seeks to gain insights into the unique characteristics of media governance in China through thematic mining of policy texts. Our contribution is manifested in three dimensions: we introduced a cutting-edge and innovative method to dissect the policy texts and empirically analyze the phased themes; we explained the evolution and theorized these shifts through a tri-logic synergistic framework; and we provided an understanding of the field of media governance research in the Chinese context. We expect our findings to provide valuable insights for global media governance researchers, policymakers, and media practitioners, and, furthermore, to form the understanding of media governance development in China and beyond.

2. Literature Review

The study of media governance policies is important for understanding how regulatory frameworks shape media ecosystems and their societal implications. For instance, Bajomi-Lazar demonstrates that universalistic media policies, such as news subsidies and frequency allocations, can mitigate inequalities in media access, while particularistic policies can exacerbate structural inequities, highlighting the real-world consequences of policy design [12]. Similarly, Banghart et al. examines the significance of organizational social media policies in the management of boundaries in digital spaces, emphasizing the potential of policy interventions to mediate the tension between institutional control and individual agency [13]. The prevailing focus of ongoing research in the field of media governance focuses primarily on following areas: (1) content integrity and disinformation control, e.g., AI-driven fake news detection [14], (2) discussion on the close relationship between media governance policies and the public sphere [15,16], (3) public–private power dynamics, e.g., critique of corporate entities’ predominance in digital platform governance [17], and (4) media governance and digital authoritarianism: citizens creatively utilize digital technologies to assert their rights [18], while, conversely, the state utilizes media technologies to cultivate social cohesion and national identity among them [19]. This inherent tension underscores the critical importance of media governance policies. Hallin and Mancini proposed three models of media systems development—polarized pluralism, democratic corporatism, and liberal models—that offer valuable theoretical frameworks for understanding media governance logics across diverse national contexts [20]. These models underscore the diverse roles that media assumes within the political systems of the respective countries. In this context, the construction of legitimacy emerges as a core challenge. Lipset proposes that the stability of democracy depends not only on economic development but also on the political system’s effectiveness and legitimacy, defining legitimacy as a system’s capacity to foster and sustain the belief that existing political institutions are best suited to society [21]. Beetham further conceptualizes legitimacy as encompassing three elements: rule-derived validity, the justifiability of power rules, and expressed consent [22]. This framework reveals significant differences in how nations prioritize these elements: China tends to prioritize the rule-derived validity and justifiability of power rules, while Western democracies often highlight expressed consent. This underscores the critical importance of considering the national context when researching media governance policies.

In contrast to the global perspectives offered by these frameworks, recent research in the Chinese context reveals the following research trajectories: a systematic assessment of media reform by means of longitudinal policy analysis [23]; exploration of a hybrid regulatory paradigm that integrates characteristics of both power-regulated and rights-regulated societies [24]; and strong support from the country’s political and financial resources for specific media industries [25], as well as the transnational economic evaluation of expansion strategies [26]. Notably, MacKinnon’s research on “networked authoritarianism” reveals how China has adapted to the realities of citizens’ Internet usage, developing mechanisms—content filtration and state-aligned information dissemination—to repurpose the Internet as an instrument of governance [27]. Despite these advances, research on media governance policies in the Chinese context remains scarce, especially in terms of elucidating the thematic evolutionary trajectories, pattern identification, and explanatory frameworks of media governance policy transformations in China. Existing studies, such as qualitative investigation of private media regulation in the digital economy [28] and analysis of social media policies in educational institutions [29], have relied predominantly on qualitative methodologies such as interviews and case studies, with gaps in systematic longitudinal analyses of policy evolution.

Rapid advances in computational social science have introduced rigorous quantitative techniques for policy analysis and for enabling objective, accurate, and replicable studies of large textual data. For example, a hybrid approach combining Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) and quantitative textual analyses was utilized to map the objectives and instruments of China’s circular economy policy for electric vehicle batteries, thereby revealing priority themes in the development of EV battery policy in China [30]. Similarly, LDA was utilized to track the progression of China’s renewable energy policy, with the objective of comprehending the national-level strategic planning and official attitudes towards the development of renewable energy [31]. Moreover, the integration of text mining and visualization techniques to elucidate annual shifts in Japan’s marine policy demonstrates the efficacy of these approaches in capturing temporal policy dynamics [32]. More innovatively, LDA was used to explore the dynamics of attention allocation in China’s e-government agenda by analyzing the punctuations and diversity of texts [33], and to quantify public concerns across constituencies in the UK through e-petition data [34]. However, extant studies have tended to emphasize thematic extraction at the expense of theoretical explanations of policy development. While these studies have effectively quantified thematic salience and mapped temporal patterns, concerns about deeper socio-political and technological mechanisms driving thematic shifts have not been the focus of these studies. It highlights the necessity to integrate evolutionary frameworks into computational analyses. The framework must consider the dynamic interplay between technological advances, societal needs, and governance philosophies. This integration enables the anchoring of thematic insights in the broader contextual forces that influence the evolution of policy, thereby enhancing the explanatory depth of policy text analyses.

In recognition of the existing research gaps, our study proposed to leverage advanced text mining techniques for a systematically in-depth analysis of China’s media governance policy texts, elucidating the adaptive epistemic framework of such guidance and regulatory tools in the media ecosystem.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: Section 3 describes the methodological framework of the study, including the data collection protocol and analysis tools. Then, Section 4 presents the empirical results derived from LDA topic modeling and co-word networks, as well as provides a theoretical interpretation framework across periods from the synergistic perspective. Finally, Section 5 discusses the conclusions, limitations, and further research in future.

3. Methodology

Topic modeling is a widely used statistical technique for identifying latent variables in large unstructured text corpora. It is an important tool for discovering topic relevance and temporal variation in policy discourse [35,36]. The LDA model, introduced by Blei et al., is a generative probabilistic framework that assumes documents are mixtures of latent topics, each of which is characterized by a distribution of words, and that each document exhibits a probability distribution of these topics [37]. This unsupervised approach enables researchers to algorithmically detect hidden thematic structures without the need for predefined categories, thus avoiding the influence of the researcher’s subjective tendencies, and is therefore particularly well-suited for exploratory analysis of complex policy texts.

The LDA model offers three significant advantages in policy text mining:

- (1)

- Scalability and Flexibility: It efficiently processes large-scale text datasets across domains (e.g., legislative documents, social media) and adapts to heterogeneous data formats [38].

- (2)

- Unsupervised Pattern Discovery: In contrast to supervised approaches that necessitate labeled training data, this method autonomously identifies emerging themes and reduces researcher bias in theme predetermination [39].

- (3)

- Visualization and Interpretable Presentation: Its probabilistic topic-word distributions enable intuitive and straightforward interpretation, thereby facilitating interdisciplinary communication and debate between computational and qualitative researchers in social science fields [40].

In policy research, the LDA has been extensively validated as a robust and reliable method for mapping thematic priorities and their evolutionary trajectories. In the study of China’s policy research, the capacity of LDA to quantify temporal changes in the themes of the governance agenda demonstrates its utility in capturing macro-level policy dynamics [41,42]. The empirical rigor of the model is commensurate with the requirement of computational social science for a scientifically valid and objective analytical framework.

3.1. Data

We collected national-level media governance policy texts issued between 1996 and 2024 to dissect and analyze the characteristics, evolutionary patterns, and internal logic of China’s media governance framework. All policy documents were retrieved from the PKULAW database (www.pkulaw.com), a widely recognized text database of Chinese laws and regulations, and cross-verified through official websites of central governmental bodies, including the State Council, the National Radio and Television Administration, and the Publicity Department.

Specifically, we used the semantic search function on PKULAW to identify policy titles and full texts using “media” and “governance”, and “news” and “governance” as keywords, thereby building an initial policy dataset. To ensure rigor, we manually cross-checked these documents with announcements published on government portals to eliminate extraneous data and verify the authenticity of the documents. Furthermore, in order to mitigate selection bias, we also consulted with experts in the field of media and journalism policy studies to confirm the relevance and completeness of the corpus.

As of 1 March 2025, after an initial screening process, 28 national-level policy documents were retained for our analysis, encompassing laws, regulations, industry guidelines, and administrative directives. Regional or provincial policies were excluded due to their limited jurisdictional scope and their inability to reflect national-level governance trends. This exclusion is consistent with our focus on capturing macro-level thematic shifts driven by central authorities that have a definitive impact on China’s media governance paradigm.

3.2. Processing

The policy texts processing phase entailed rigorous text normalization in order to enhance the semantic coherence of the corpus for topic modeling. This phase was conducted in accordance with a systematic workflow in order to ensure analytical validity. Firstly, the policy documents were divided into four chronological periods (1996–2005, 2006–2013, 2014–2020, and 2021–2024), reflecting significant regulatory milestones. Subsequently, domain-specific preprocessing was performed using an integrated linguistic pipeline. The Jieba POS tagger (jieba.posseg) was used to perform morphosyntactic analysis, enabling the selective retention of policy-relevant lexical categories. This was complemented by a custom media governance dictionary, which enhanced the precision of segmentation for institutional terms such as “三审制” (three-tier editorial review) and “机构编制” (organizational staffing). These terms were meticulously curated from policy analysis literature and expert consultations with the objective of preserving culturally salient concepts that are frequently overlooked by generic NLP tools. We subsequently employed a triple filtering mechanism: (1) tokens shorter than two characters were removed, as such fragments usually contribute noise rather than meaningful content [43]; (2) morphological filtering was used to retain only nouns, verbal nouns, verbs, and adjectives to capture policy actions and goals; (3) frequent stop words, including high-frequency function words (e.g., “什么” [what], “哪里” [where], “关于” [about]) and non-lexical symbols, were systematically filtered using the Harbin Institute of Technology (HIT) Stopwords List. This is a standardized resource that has been extensively adopted in the domain of Chinese computational linguistics for the purpose of eliminating semantically redundant terms. The cleaned texts were then vectorized using term frequency counts and fed into period-specific LDA models. Each model underwent 30 training passes with 300 iterations per topic configuration to ensure full convergence, incorporating automatic alpha optimization. The optimal number of topics was determined by selecting the number of topics corresponding to the highest c_v coherence score, calculated via Gensim’s CoherenceModel from Python [44,45]. Finally, dominant policy themes were extracted on the basis of topic probability distributions, and high-frequency words were derived in tabular form for comparative analysis across time periods.

The framework of the analysis is shown in Figure 1, wherein the topic analysis and co-occurrence analysis across periods were conducted after completing the data and processing stage. These processing steps ensured analytical reliability by optimizing the policy dataset and balancing noise reduction with semantic preservation. In addition, period-by-period modeling and rigorous coherence validation ensured the cross-temporal comparability of policy themes, thereby providing a robust basis for studying the temporal evolution of media governance paradigms in China.

Figure 1.

Framework of analysis of policy evolution.

4. Results

4.1. Temporal Segmentation and Topic Number Selection

The temporal segmentation (periods of 1996–2005, 2006–2013, 2014–2020, and 2021–2024) is based on landmark policy shifts (e.g., the 2006 national campaign to regulate and standardize the market economy, the 2015 media convergence strategy) and technological inflection points (e.g., the Internet expansion to AI adoption), validated by LDA topic modeling to reveal distinct lexical clusters. This segmentation ensures methodological rigor and consistency with empirical evidence and effectively avoids arbitrary chronological divisions.

The optimal topic numbers were determined through an iterative optimization of c_v coherence scores, a well-validated metric for evaluating topic interpretability in policy texts [38], avoiding thematic fragmentation [46], and aligning with media governance policy shifts. Following established computational linguistics protocols, we implemented Latent Dirichlet Allocation with 300 iterations and 30 passes per model to ensure parameter stability, while allowing document–topic distributions to self-adjust through automated hyperparameter tuning [37,47].

As shown in Figure 2, the trajectories of coherence scores differ significantly across the four periods. The number of themes with the highest coherence score represents the optimal number of themes. Therefore, the optimal numbers of the periods 1996–2005, 2006–2013, 2014–2020 and 2021–2024 are 4, 3, 6, and 6, respectively. Obviously, the coherence scores of the optimal number of topics for each of the four time periods exceed 0.5, indicating that the topics generated by the model exhibit good semantic interpretability and strong intrinsic correlation with the text data, which further validates the reasonability of our topic number selection. As LDA uses randomness in both training and inference steps, we minimized randomness by fixing the random_state value; slight variations in the coherence curves are inevitable. However, these variations will not materially affect the research and main conclusions of this paper. Subsequently, the high-frequency words of the related topics for each period were retained, as shown in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4.

Figure 2.

The coherence scores calculation result based on the LDA model.

Table 1.

The distribution of topic-relevant words in media governance policies during 1996–2005.

Table 2.

The distribution of topic-relevant words in media governance policies during 2006–2013.

Table 3.

The distribution of topic-relevant words in media governance policies during 2014–2020.

Table 4.

The distribution of topic-relevant words in media governance policies during 2021–2024.

4.2. Tri-Logical Analysis of Evolution Across Periods

4.2.1. 1996–2005 Period: Institutionalization of Media Governance Framework Under Emerging Information Society

The 1996–2005 period witnessed the institutional consolidation of China’s media governance framework, as shown in Table 1. This is evidenced by the dominance of four primary themes: Hierarchical Licensing of Media Institutions (28.3%), Bureaucratization of Journalism Credentialing Systems (24.6%), Administrative Governance of Print Media Distribution (20.7%), and Civic Oversight Institutionalization in News Systems (16.3%). These themes reflect systematic efforts to institutionalize media regulation and operational protocols through statutory oversight (e.g., National Press and Publication Administration, Supervision by Public Opinion), accreditation systems (e.g., Journalist Accreditation Certificate), and hierarchical controls (e.g., Central Authorities). The high-frequency words highlight the state’s prioritization of stability through mechanisms such as public opinion oversight and licensing regimes. Notably, while traditional formats such as print, radio, and television remain fundamental, the Internet era is steadily elevating online news from a supplementary role to a central position, simultaneously underscoring the limited technological ambition compared to its institutional preoccupations.

From a technical perspective, the government’s prioritization of infrastructure development and the regulation of the news publishing industry mirrors the fundamental principles of media governance, characterized by efforts to construct a hierarchical network of physical infrastructure to facilitate the digital transition. With respect to societal demands, considerable disparities emerge between urban and rural media environments, as evidenced by initiatives such as “village-to-village” broadcasting, which caters specifically to rural audiences, and the substantial surge in news website development observed during the 2000s. Furthermore, journalists, as a pivotal component of the media industry, were emphasized to consciously accept the supervision of the government and the people. In terms of governance, the county-level radio and television stations were merged into a unified broadcasting entity, which primarily disseminated radio and television programs from the central and provincial levels. The establishment of stations without authorization, redundant setups, and indiscriminate broadcasting were prohibited without unified approval.

4.2.2. 2006–2013 Period: Transitioning to Professionalized and Market-Responsive Media Governance

The 2006–2013 period marked a strategic adjustment of China’s media governance, as shown in Table 2. This is evidenced by the dominance of three primary themes. Professionalization of Media Practices (23.6%) is dominated by credentialing mechanisms (e.g., Journalist Accreditation Certificate, Personnel, Editing and Reporting) and accountability frameworks (e.g., Administrative Measures). Concurrently, Construction of Market-Oriented Regulatory System (15.0%) emphasized media sector modernization (e.g., Press and Publication, Enterprise, Publishing Industry) and bureaucratic efficiency (e.g., Development Agenda, Market). For the third theme, Ethical Compliance Enforcement (12.7%) targeted commercialized distortions (e.g., Paid News) through specialized campaigns, mirroring the anti-corruption drive in the media industry during this period. The coexistence of persistent legacy high-frequency words (e.g., Press and Publication, Journalist Accreditation Certificate) and emerging high-frequency words (e.g., Enterprise, Paid News) reveals a dual-track balance between institutional inertia and the establishment of a new regulatory system in a rapidly developing media market.

Technological advances drove the initial digital transformation and the subsequent development of platform-based media. However, policy had remained anchored in traditional governance frameworks such as publishing authorizations, reflecting a prudent adaptation to the empowering potential of Internet technologies. In terms of its social implications, the advent of marketization had given rise to a pressing need for reform in the realm of professional qualification management, particularly with regard to the emergence of corruption in the media industry, as evidenced by phenomena such as paid journalism and editorial misconduct. In addition, the institutional architecture of public service functions has been meticulously crafted to align with the public’s expectations of social responsibility in the media sphere. The governance strategy combined centralized regulation with procedural standardization, thereby marking a transition from purely administrative control to a synergistic mechanism combining market regulation and state guidance. In China, personnel management mechanisms have maintained their distinctive institutional characteristics through different policy cycles, reflecting the continued focus of the Chinese media ecosystem on professional qualification systems and strategic talent development. The personnel system constitutes an important component in the development of media professionalism. The enhancement of professional standards within the media industry, in conjunction with the fortification of a hierarchical regulatory framework, are congruent in their pursuit of modernizing national governance capabilities. The media adhere to both professional norms and political requirements, with professional competence serving as the pathway to the fulfillment of the media’s political function.

4.2.3. 2014–2020 Period: Technological Empowerment and Legal Governance in the Media Convergence Era

The 2014–2020 period witnessed China’s media governance evolve into a techno-legal hybrid regime, systematically integrating algorithmic control, bureaucratic efficiency, and statutory compliance, as shown in Table 3. This is characterized by Localized Algorithmic Governance in Media Regulatory Implementation (31.3%) and Comprehensive Governance of Information Ecology (29.9%), as evidenced through high-frequency term analysis (e.g., Local Government, Information, Online News). The Cyberspace Administration of China exercises oversight over Internet news services and enforces regulations on a national scale, while local offices manage these duties within their respective jurisdictions. The service providers who introduce new technologies or features with public opinion attributes or social mobilization capabilities must undergo security assessments by national- or provincial-level administrations. All online platforms, including websites, applications, social media, and livestreaming services, that provide public news services are obligated to obtain official licenses, as mandated by Provisions for the Administration of Internet News Information Services (2017). In addition, Techno-Legal Reconfiguration of Sectors (20.5%), Centralized Professional Coordination Framework for Media Convergence Governance (17.5%), and Data-Oriented Public Service Delivery (15.4%) held slightly lower proportions than the leading themes but remained essential in driving the governance of media convergence and fostering digital public engagement. The high-frequency keyword analysis reveals that the governance framework during this period confronted dual imperatives of regulatory institutionalization driven by technological innovation and the containment of disinformation proliferation. Such governance demands transcended localized jurisdictions, necessitating coordinated efforts between central and local authorities to deploy cutting-edge technological solutions for systematic oversight.

The empowerment of digital technology not only enhances the precision and efficiency of governance processes, but also streamlines operations via online approval, big data analysis, and other mechanisms, thereby increasing the flexibility of traditional hierarchical structures. Furthermore, the integration of traditional media and digital platforms has fostered a polycentric media ecosystem, characterized by diversified formats (e.g., short-video narratives, interactive live streams) and multi-layered content networks. This convergence, however, amplifies latent governance tensions (e.g., copyright protection), thereby imposing heightened demands on cross-platform regulatory coordination. At the social level, digital governance has expanded channels for public participation in public affairs. This development has enabled governments to utilize basic data to more effectively address citizens’ needs and protect the public interest. Meanwhile, diversified media formats (e.g., short videos from various apps) spurred social engagement, thereby cultivating grassroots innovation and a more vibrant public sphere. The governance paradigm prioritizes institutionalized techno-legal integration and the development of professional governance capacity, addressing both systemic risks and developmental needs through hierarchical coordination. Notably, such a paradigm is profoundly influencing the state–society interaction and fostering an innovative governance model.

4.2.4. 2021–2024 Period: Precision Governance and People-Centric Service Integration in the AI-Driven Media Era

China’s media governance policies from 2021 to 2024 have been marked by the synergistic deepening of platform consolidation, AI-driven empowerment, and people-centric public service, as shown in Table 4. For the theme of Algorithmic Accountability Frameworks for Self-Media Ecosystems (19.8%), the evolution of media governance has shifted from superficial oversight to precision-oriented, intelligent, and predictive–preventive paradigms; in the meantime, significantly, governance logic has shifted toward quantified evaluation systems and dynamic precision regulation through digital governance tools. Under the themes of Dynamic Risk Prevention in Cross-Platform Information Ecology (13.8%) and Content Innovation in Mainstream Media (13.3%), the government has centralized information dissemination channels through government-affiliated new media platforms and official portals, while completing media entities’ registered account certifications to strengthen accountability tracing. In this process, artificial intelligence (AI) technologies have been systematically integrated into cross-cycle auditing frameworks for online information content. Regulatory frameworks now establish compliance thresholds as red lines and implement tiered classifications for regulatory incidents. Within the theme of Differentiated Regulation in Smart Audiovisual Industrial Clusters, local governments across all levels are actively cultivating emerging digital audio-visual industry clusters (e.g., Industrial Corridors) to amplify economies of scale and further strengthen their agglomeration and spillover effects.

Advances in digital technologies and innovations have led to the emergence of new media forms and have enhanced regulatory precision and operational efficiency. Innovations such as metaverse media and generative AI content creation have contributed to the maturation of the polycentric media ecosystem, resulting in the establishment of distinct media platforms for both government and public entities, thereby enabling these entities to exert influence over public discourse. Significant shifts have occurred in the relationship between the government and the citizenry. Regarding societal demands, the 12345 Hotline platform, integrating Weibo accounts, government portals, and news apps, creates an innovative grassroots governance paradigm that integrates one-stop services with grid-based management, enabling direct government-to-people communication and generating governance data for addressing precise needs. Through interactive platforms, e-petition systems, and civic apps (e.g., Shanghai’s “Suishenban”, Hebei’s “Ji Shi Ban”, Guizhou’s “Gui Ren Service”), residents can seamlessly access government services anytime and anywhere. Supported by government initiatives, the diversification of media products and formats (e.g., AI-generated content, digital news anchors, and immersive storytelling) have further catalyzed societal vibrancy to a greater extent than in the previous period. In terms of governance philosophy, media has transformed from regulated entities to active collaborators within China’s national governance modernization agenda. This shift is evidenced by the emphasis placed by policymakers on the efficacy of algorithm-enhanced governance, complemented by the advocacy of an approach termed “emotional governance with human warmth.”

4.2.5. Integrating Tri-Logic Synergy Across Periods: The Evolutionary Logic of Media Governance Policies

This subsection categorizes the high-frequency terms from the four periods into three dimensions, Technological Drivers, Societal Demands, and Governance Philosophy, as shown in Table 5, to examine the overall logic behind the evolution of China’s media governance policy themes. The tri-logic synergistic perspective does not rely on a pre-defined framework; rather, it naturally reveals the characteristics of policy evolution over periods through the distribution of high-frequency terms across these three dimensions.

Table 5.

High-frequency terms distribution across periods.

Analysis based on the tri-logic synergy reveals that policy evolution is the result of the dynamic interplay and mutual constitution of Technological Drivers, Societal Demands, and Governance Philosophy, presenting a distinct trajectory from centralized control to collaborative governance. In this process, technological drivers not only reshape media forms but also reconfigure governance structures; changes in societal demands both guide policy direction and are modulated by governance mechanisms, and the evolution of governance philosophy is propelled by both technology and society while, in turn, steering the direction of their synergy.

Technological drivers have undergone a profound transformation, transitioning from the role of governance targets to that of active governance agents. Technological advancement continuously responds to evolving citizen needs, such as information supply equity, enthusiasm for participating in public affairs, and the demand for co-governance. Each shift in technological logic has forced governance to upgrade: the platform era necessitated personnel systems, the media convergence era demanded hierarchical collaboration, and the current ecosystem era requires algorithmic governance coupled with emotional accommodation.

Societal demands achieve creative transformation through institutionalized channels. Technological progress has spawned new societal demands; for example, the development of digital technologies and media convergence have engendered public needs for convenient access to news and diversified media content. Societal demands exert legitimacy pressure, reshaping governance logic through institutional pathways. From addressing regional imbalances in service supply to cracking down on paid news and strengthening copyright protection, governance has been promoted toward greater refinement, digitization, and human warmth.

Governance philosophy embodies the institutional absorption of conflicts and demonstrates adaptive wisdom. When technology weakens the effectiveness of control, control tools are innovated—for instance, as media platformization weakened quota management, personnel systems were adopted to strengthen supervision. Governance philosophy defines the “reasonableness” of societal demands via value guidance, provides their “material foundation” via resource allocation, and establishes their “realization pathways” via institutional design. In this way, governance philosophy both responds to social pressures and maintains its leading role. Facing the growing public enthusiasm for participating in governance and the mature and diverse media ecology, governance has not simply strengthened control but has created a novel paradigm of “emotional and humanized governance”, along with more sophisticated digital governance, and transformed industrial innovation policies into economic benefits.

From the perspective of tri-logic synergy, the core characteristics of media governance with Chinese characteristics are revealed. The evolution of the three logics has always been accompanied by a long-term pursuit of balance, and it is precisely this pursuit of balance that has driven the development of technological innovation and social needs. The “technology–society” relationship is not a binary antagonism; rather, governance philosophy enables a creative transformation, facilitating synergistic co-evolution where technological empowerment and societal participation advance together. The tri-logic synergy provides a valuable analytical framework for governance research. Future studies could either extend its application to adjacent domains (e.g., education or healthcare governance) or deepen its theoretical refinement within the evolving media governance landscape.

4.3. Co-Word Network Analysis

In order to systematically analyze the structural logic of China’s media governance paradigm, this study adopted co-word network analysis to map the conceptual interdependencies in policy texts from 1996 to 2024. The text mining and graphing process was implemented using Python 3.12.10 and Gephi 0.10.1. First, keyword frequencies and co-occurrence relationships were extracted from the policy texts. Then, a co-occurrence matrix was constructed to quantify the strength of semantic associations between concepts. Finally, the combination of node degrees and edges data was used for generating network graphs over four periods as well as for interpreting network structure characteristics. Co-occurrence network analysis effectively addresses the issue of ambiguous conceptual hierarchies in traditional policy text analysis. Its visual outputs excel at intuitively depicting the structural features of policy systems, thereby providing a valuable complement to topic modeling methods.

The co-occurrence networks show the dynamic evolution of policy priorities across four periods, as presented in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6. The size of the nodes denotes the degree of keywords, i.e., their importance, while the edges between nodes represent the connections among keywords. In addition, the core-periphery model highlights the centrality of dominant policy frameworks, while the cluster pattern reflects how subsidiary policies form synergistic groups to support overarching goals. These findings have significant theoretical value in explaining the path dependency and evolutionary mechanisms of China’s media governance system. Through these networks, nuanced changes in policy priorities become observable, enabling a detailed analysis of the temporal patterns and trends of policy development.

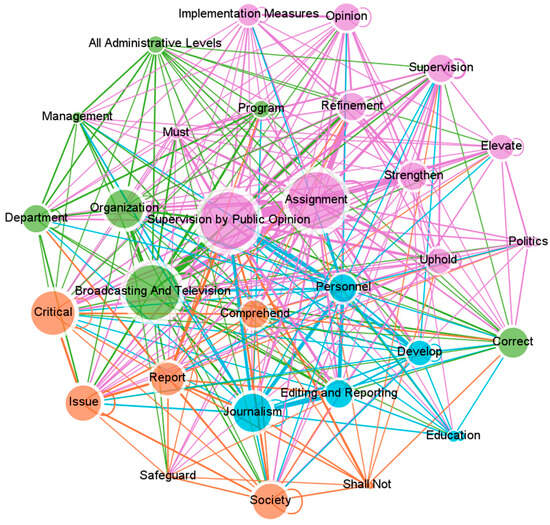

Figure 3.

Policy keyword co-occurrence networks during 1996–2005.

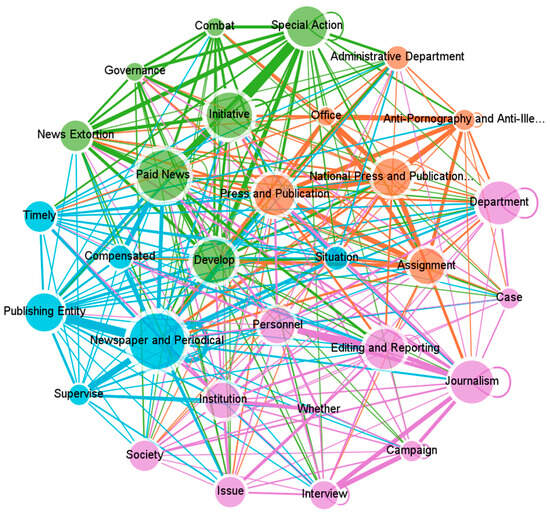

Figure 4.

Policy keyword co-occurrence networks during 2006–2013.

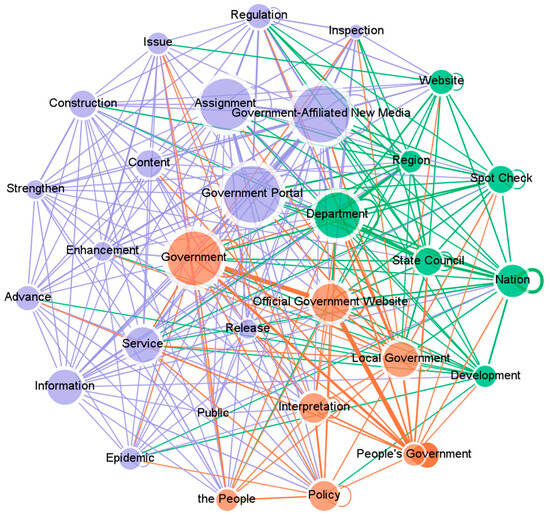

Figure 5.

Policy keyword co-occurrence networks during 2014–2020.

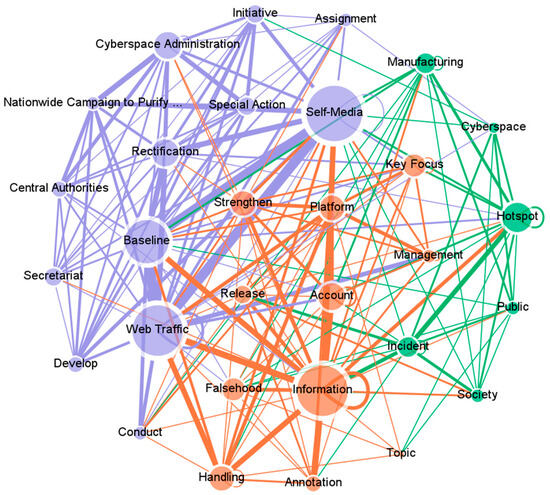

Figure 6.

Policy keyword co-occurrence networks during 2021–2024.

As shown in Figure 3, the 1996–2005 period co-word network visualized four distinct clusters: institutional framework cluster (centered on Supervision by Public Opinion, Assignment); industry personnel system cluster (Editing and Reporting, Personnel, Education); regulation cluster (Critical, Issue, Shall not); and traditional media cluster (Broadcasting and Television, Organization). Remarkably, Assignment, Supervision by Public Opinion and Broadcasting and Television as prominent nodes with high node degree show strong co-occurrence patterns with terms like Refinement, Strengthen, and Organization. This period witnessed growing governance demands for Internet content oversight and public opinion regulation driven by technological advancement, characterized by rigorous bureaucratic control mechanisms.

As shown in Figure 4, the 2006–2013 period visualized four clusters: media industry cluster (centered on Newspapers and Periodicals, Publishing Entities); news corruption rectification cluster (Paid News, Special Actions); publishing industry regulation cluster (Press and Publication, Assignments); and industry talent cultivation cluster (Personnel, Institutions, Editing and Reporting). Nodes like Special Actions and Initiatives emerged as the most strongly associated pair, followed by Publishing Entities and Newspapers and Periodicals, underscoring bifurcated policy priorities: combatting paid journalism while advancing market-oriented reforms in news publishing. In addition, other key nodes like Develop and Personnel further emphasize the importance that governance attaches to professional capacity-building and talent development.

As shown in Figure 5, the 2014–2020 period visualized three clusters: government-affiliated media cluster (centered on Government Portals, Government-affiliated New Media); e-governance cluster (Government, Local Government, Official Government Website); and new media regulation cluster (Departments, Spot Check), reflecting a maturing digital governance framework that combined administrative modernization with media supervision. Emerging media technologies enabled one-stop government services and the optimization of grassroots social governance, while the interplay between self-media and official discourse created multi-layered media landscapes. The elevation of media convergence as a national strategy in 2015 was accompanied by the duality of combining strict content oversight with industrial promotion, and with governance prioritizing central–local coordination, bureaucratic efficiency, and cutting-edge technological applications.

As shown in Figure 6, the 2021–2024 period visualized three clusters: self-media regulation cluster (centered on Self-Media, Web Traffic, Baseline); information governance cluster (Information, Account, Platform); and participatory governance cluster (Hotspot, Incident, Public). This phase featured intensified self-media regulation, exemplified by the 2024 Qinglang Campaign initiated by the Cyberspace Administration of China. The ongoing campaign targets a variety of bottomless traffic-boosting behaviors, including fake personas that violate public order and morals, misinformation and malpractice in livestreaming, and exaggerated headlines and clickbait. In addition, nodes like Special Action and Central Authorities show the significance of bureaucracy within platform governance, while other nodes like Public and Society reflect alignment with public interests. Media platforms like self-media and web portals are actively leveraged by the government, thereby transforming the media from an object of governance to a subject of governance. Utilizing bureaucratic structures and emerging media technologies, media governance has achieved a sophisticated and delicate balance between institutional rigidity and technological flexibility.

5. Conclusions, Limitations and Future Research

This study provides scholars, policymakers, and media practitioners with a focused analysis of China’s media governance policy evolution and trajectories (1996–2024), offering valuable insights for future research and practice. A nuanced understanding of policy thematic shifts is critical to interpreting the institutional logic and operational dynamics underpinning the governance framework.

Based on our analysis, there were three key findings as follows:

Firstly, the evolution of media governance policies over the past three decades in China constitutes a dynamic adaptive system shaped by three interconnected dimensions: technological advancement, evolving societal expectations, and transformed governance philosophies.

- (1)

- Technological progress has been foundational, evolving from early distribution authorization protocols to AI-powered response architectures.

- (2)

- Societal priorities have driven policy adjustments, shifting from fundamental public service coordination to more nuanced solutions for complex quality-of-life issues.

- (3)

- Governance paradigms have transitioned from centralized administrative frameworks to integrated systems that prioritize citizen welfare and social cohesion.

These dimensions and dynamics interact to form a balanced, tripartite framework that fulfills the dual governance requirements of control and oversight, as well as guidance and support. This synergy has resulted in a resilient media governance model. This model effectively navigates China’s evolving digital and informational landscape while maintaining institutional continuity, gradually becoming a crucial component of the national governance system.

China’s media governance policy demonstrates a distinctive philosophy. On the one hand, it promotes the sound operation and strong development of media organizations by coordinating cooperation between the state and society and striking a delicate balance between regulatory discipline and social innovation. On the other hand, it explores the role of the media as a governing body within a broader governance context by integrating intelligent, precise governance with a humane and emotional approach.

Secondly, through systematic analysis of research findings, we reveal that the thematic evolution of China’s media governance policies essentially constitutes an adaptive reproduction of governance legitimacy, operationalized via the state’s dual mechanisms: systematic technological progression and institutionalized co-optation of societal demands. This manifests as a controlled innovation path with three core operational logics:

- (1)

- Technological Drivers: From Infrastructure Building to Intelligent Precision Governance

Policy priorities have transitioned from analog-era practices (periodical registration, editorial oversight) to digital governance tools (registered account systems) and algorithmic regulation (designated platforms), culminating in intelligent response systems (e.g., 12345 Hotline). Crucially, technology has evolved from a governance target to an active governance agent, functioning as a legitimacy mediation mechanism under state stewardship.

- (2)

- Societal Demands: From Stability Primacy to Emotional Resonance

Policy responsiveness has shifted from information services to market-oriented services, then to participatory and emotional governance. This trajectory signifies the public’s transition from passive recipients to data-engaged stakeholders, propelling governance systems towards empathetic and human-centered capabilities.

- (3)

- Governance Philosophy: From Institutionalized and Professionalized Governance to Collaborative Governance

Initially with strong regulation and bureaucratic hierarchy, it transitioned to a decentralization-control balance—promoting specialization via accreditation systems while curbing the negative externalities of marketization via publication authorizations. Then, it evolved into techno-legal convergence, where technocratic rationality manifested itself in compliance thresholds and regulatory benchmarks, thereby forming a state–society synergy. The mature stage emphasizes intelligent and precise governance, aligning public sentiment through consensus building, and institutionalizing the “co-construction, co-governance, co-sharing” philosophy in both theory and practice.

The state institutionalizes technological innovations and societal demands into the normative framework through regulatory instruments, along with dynamic adaptation, to achieve the harmonization of technology, society, and governance. Co-word network analysis further substantiates this governance structure, revealing that the policy network invariably revolves around national strategic nodes, while societal nodes form sub-clusters through synergistic linkages. This structural configuration demonstrates the resilience of governance and the dialectic between high-level coordination and grassroots innovation.

Finally, our investigation of the thematic evolution reveals the trend of Chinese media government policy development. From 1996 to 2005, the primary focus was on institutional consolidation, with the objective of establishing a vertical regulatory system. From 2006 to 2013, the policy underwent a period of professionalization and market-oriented development, during which industry standards were elevated through the implementation of professional certifications. Concurrently, the market irregularities were addressed and anti-corruption measures were intensified in media sectors. The subsequent period 2014–2020 saw a transition in governance towards an integrated model that combines technology and law, with the strategy of media convergence being employed to embed algorithmic regulation into public services. The period 2021–2024 saw a progression towards an intelligent precision governance stage, marked by the utilization of AI-powered response systems for policy supply–demand alignment, real-time data visualization for demand tracking, and sentiment analysis to quantify public sentiment as governance performance metrics. These phases do not strictly succeed one another in a linear fashion; instead, they exhibit cumulative evolution, where institutional legacies provide organizational foundations for technological innovations. Concurrently, the shift in governance philosophy, namely from a control-oriented to a collaborative paradigm, permeates the dynamic interplay between technological tools and societal demands throughout the process.

While this study provides critical insights into the thematic evolution of China’s media governance policies, three limitations must be acknowledged. Firstly, although the analysis of policy texts reveals thematic shifts, it struggles to capture the interactions and practical tensions among stakeholders during policy implementation. Secondly, the micro-level operational mechanisms of the tri-logic framework require further empirical validation. Thirdly, the evolutionary drivers of China’s media governance policies require deeper theoretical conceptualization. Future research could be expanded in three directions: (1) In-depth interviews with policymakers and practitioners, as well as public feedback data, are to be integrated in order to uncover the micro-dynamics of the co-evolution framework. (2) Cross-national comparative studies are to be conducted to examine how tri-logic synergies and couplings differ across political systems. (3) The transformative impact of emerging technologies like generative AI on media governance paradigms is to be investigated, with a particular focus on value conflicts and institutional adaptation challenges posed by the black-boxing of algorithmic systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.; Methodology, M.A.; Software, M.A.; Validation, L.S. and M.A.; Formal analysis, M.A.; Investigation, M.A.; Resources, L.S. and M.A.; Data curation, L.S.; Writing—original draft, M.A.; Writing—review & editing, L.S. and M.A.; Visualization, M.A.; Supervision, L.S.; Project administration, M.A.; Funding acquisition, L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Heilongjiang Provincial Higher Education Undergraduate Teaching Reform Key Entrusted Project “Research on Knowledge Production and Innovation Pathways in New Liberal Arts Disciplines—With the Development of Social Science Majors as an Example”, grant number SJGZ20220008.

Data Availability Statement

The policy text data used in this study are sourced from publicly accessible government websites and the PKULAW database. All data can be directly accessed through the official sources referenced in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Girard, C. Making democratic contestation possible: Public deliberation and mass media regulation. Policy Stud. 2015, 36, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, N. Which civil society? State-run media and shaping the politics of NGOs in post-uprising Egypt. Policy Stud. 2025, 46, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsson, P.; Lindell, J.; Stiernstedt, F. Media policy attitudes and political attitudes: The politization of media policy and the support for the ‘media welfare state. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2022, 29, 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; James, T.S.; Man, C. Governance and public administration in China. Policy Stud. 2022, 43, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W. Slow boat from China: Public discourses behind the ‘going global’ media policy. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2015, 21, 400–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Iwabuchi, K.; Gassin, G.; Seto, W. Transcultural media practices fostering cosmopolitan ethos in a digital age: Engagements with East Asian media in Australia. Inter-Asia Cult. Stud. 2020, 21, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Huang, C. Exploring the diversity and consistency of China’s information technology policy. J. Inf. Sci. 2024, 50, 1605–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xue, C.; Xie, F. The impact of policy mix characteristics of multi-level governance on innovation output of the new energy vehicle industry in China. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boossabong, P.; Chamchong, P. The practice of deliberative policy analysis in the context of political and cultural challenges: Lessons from Thailand. Policy Stud. 2019, 40, 476–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, R.; Li, Y.; Cui, T. Policy narrative, policy understanding and policy support intention: A survey experiment on energy conservation. Policy Stud. 2022, 43, 1361–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Lv, B.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Liu, S. Heterogeneous Impacts of Policy Sentiment with Different Themes on Real Estate Market: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajomi-Lazar, P. Particularistic and Universalistic Media Policies: Inequalities in the Media in Hungary. Javnost 2017, 24, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banghart, S.; Etter, M.; Stohl, C. Organizational Boundary Regulation Through Social Media Policies. Manag. Commun. Q. 2018, 32, 337–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuraisingham, B.; Thomas, T. Social Media Governance and Fake News Detection Integrated with Artificial Intelligence Governance. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Information Reuse and Integration for Data Science (IRI), San Jose, CA, USA, 7–9 August 2024; pp. 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniazzi, L.; Bengesser, C.H. Media-political inroads for Europeanising national cultural public spheres: EU-level obstacles and national public service perspectives. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2022, 29, 360–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, K. ‘Are you being served?’ Public service media: Audience conceptions of value in UK critical media infrastructure. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, R. Public and Private Power in Social Media Governance: Multistakeholderism, the Rule of Law and Democratic Accountability. Transnatl. Leg. Theory 2023, 14, 46–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, T.; Roberts, T. (Eds.) Digital Citizenship in Africa: Technologies of Agency and Repression, 1st ed.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steemers, J. Blurred Lines: Public Service Media and the State. In Global Media and National Policies; Flew, T., Iosifidis, P., Steemers, J., Eds.; Palgrave Global Media Policy and Business: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallin, D.C.; Mancini, P. Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lipset, S. Martin. Political Man: The Social Bases of Politics, 1st ed.; Doubleday: Garden City, NY, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Beetham, D. The Normative Structure of Legitimacy. In The Legitimation of Power. Issues in Political Theory; Palgrave: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G.S.; Lu, J.Y.; Hao, Y. Assessing China’s Media Reform. Asian Perspect. 2016, 40, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiguang, W. The Rationale of China’s Media Regulation Policy in the Process of the Institutional Transformation. Notre Dame J. Int. Comp. Law 2017, 7, 64–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kokas, A. Serious chemistry on set: The molecular structure of film investment in China. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2019, 26, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, M. China’s digital media industries and the challenge of overseas markets. J. Chin. Cine. 2019, 13, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, R. China’s “Networked Authoritarianism”. J. Democr. 2011, 22, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enli, G.; Raats, T.; Syvertsen, T.; Donders, K. Media policy for private media in the age of digital platforms. Eur. J. Commun. 2019, 34, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muls, J.; Thomas, V.; De Backer, F.; Zhu, C.; Lombaerts, K. Identifying the Nature of Social Media Policies in High Schools. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 25, 281–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Hu, S.; Shen, L. Quantitative Text Analysis of Circular Economy Policies for Electric Vehicle Batteries in China: Focus on Objectives and Tools. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 501, 145021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Wang, W. Evolution of renewable energy laws and policies in China. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Tanaka, K.; Akamatsu, T. Visualizing the annual transition of ocean policy in Japan using text mining. Mar. Policy 2023, 155, 105754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Fan, Z. Punctuations and diversity: Exploring dynamics of attention allocation in China’s E-government agenda. Policy Stud. 2022, 43, 502–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.D.; Lomax, N. Using e-petition data to quantify public concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study of England. Policy Stud. 2024, 45, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayansky, I.; Kumar, S.A.P. A review of topic modeling methods. Inf. Syst. 2020, 94, 101582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gui, W.; Wen, J. China’s policy similarity evaluation using LDA model: An experimental analysis in Hebei province. J. Inf. Sci. 2024, 50, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Michale, I.J. Latent Dirichlet Allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, T.L.; Steyvers, M. Finding scientific topics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101 (Suppl. 1), 5228–5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiMaggio, P.; Nag, M.; Blei, D. Exploiting affinities between topic modeling and the sociological perspective on culture: Application to newspaper coverage of U.S. government arts funding. Poetics 2013, 41, 570–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, A.; Blei, D. Visualizing Topic Models. Proc. Int. AAAI Conf. Web Soc. Media 2021, 6, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Zhang, J.; Liu, D.; Wang, Q.; Lin, S. Technological topic analysis of standard-essential patents based on the improved Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) model. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2022, 36, 2084–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Chen, Y. Evolution of Chinese original-innovation talent policies: A topic modelling approach. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2023, 36, 4128–4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; He, Y.; Fu, Y.; Xin, Y.; Du, J.; Ni, W. Cross-Domain Developer Recommendation Algorithm Based on Feature Matching. In Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing Chinese (CSCW 2019), Communications in Computer and Information Science; Sun, Y., Lu, T., Yu, Z., Fan, H., Gao, L., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röder, M.; Both, A.; Hinneburg, A. Exploring the Space of Topic Coherence Measures. In Proceedings of the 8th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, WSDM ’15, Shanghai, China, 2–6 February 2015; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Hou, B.; Klein, A.; O’Connor, K.; Chen, J.; Mondragón, A.; Yang, S.; Gonzalez, H.G.; Shen, L. Exploring Semantic Topics in Dementia Caregiver Tweets. Alzheimer’s Dement. J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2024, 20, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contiero, B.; Holand, Ø.; Cozzi, G. Identifying the optimal number of topics in text mining: A case study on reindeer pastoralism literature. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 23, 1348–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, J.; Champagne, L.E.; Dickens, J.M.; Hazen, B.T. Approaches to improve preprocessing for Latent Dirichlet Allocation topic modeling. Decis. Support Syst. 2024, 185, 114310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).