Single and Repeated Applications of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Differently Affect the Growth and Biomass Accumulation of Silene flos-cuculi L. (Caryophyllaceae)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

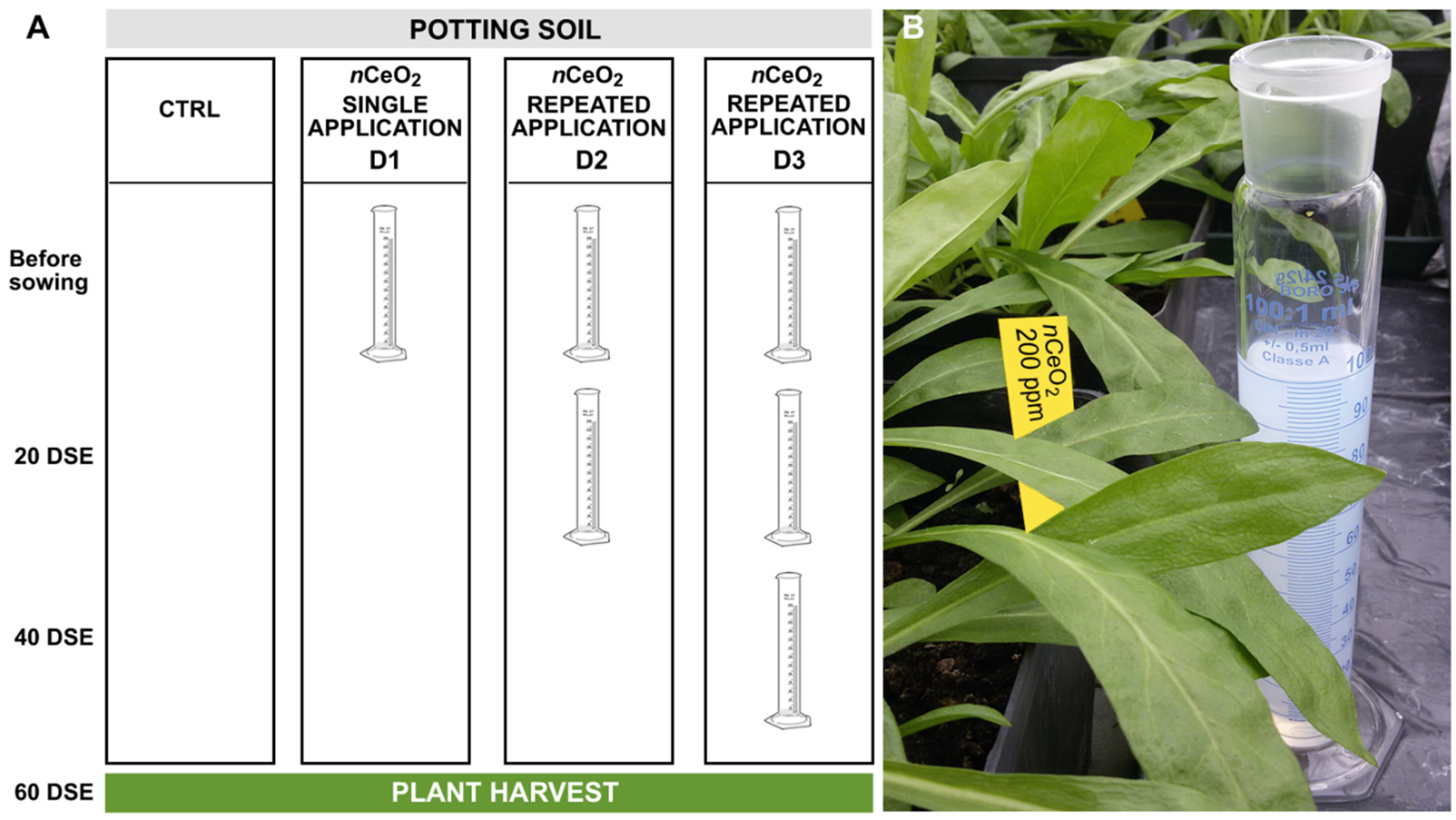

2. Materials and Methods

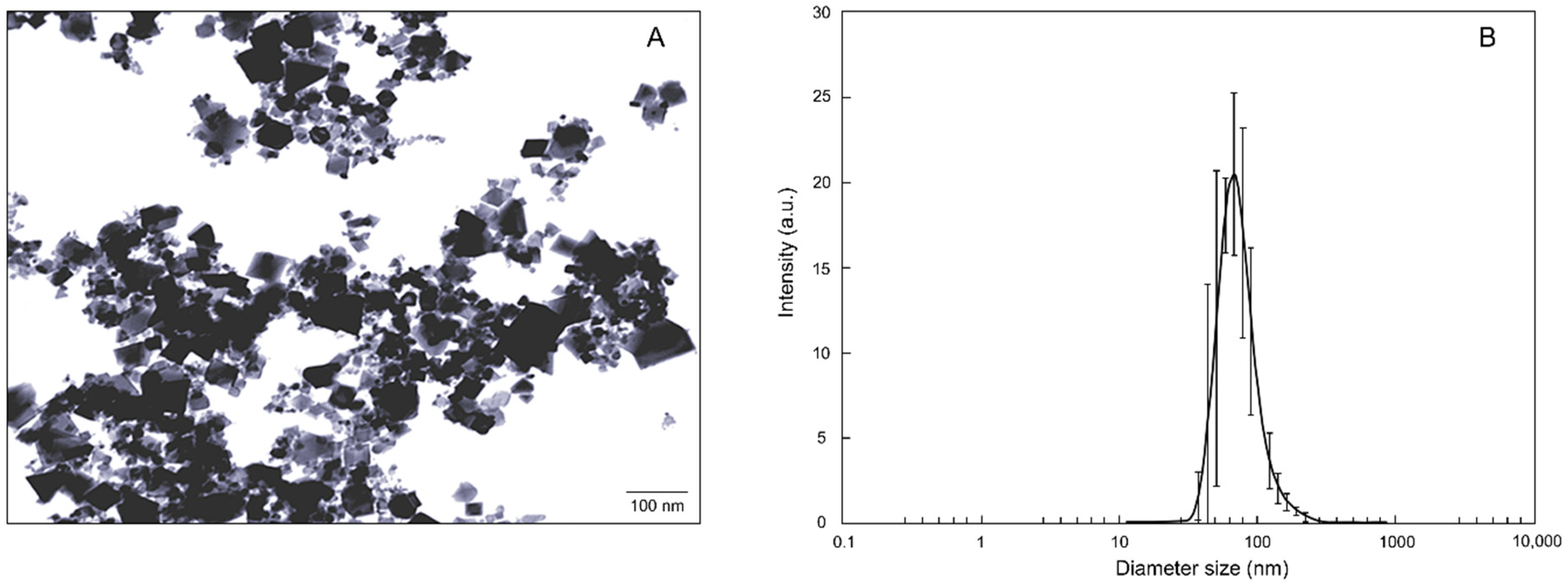

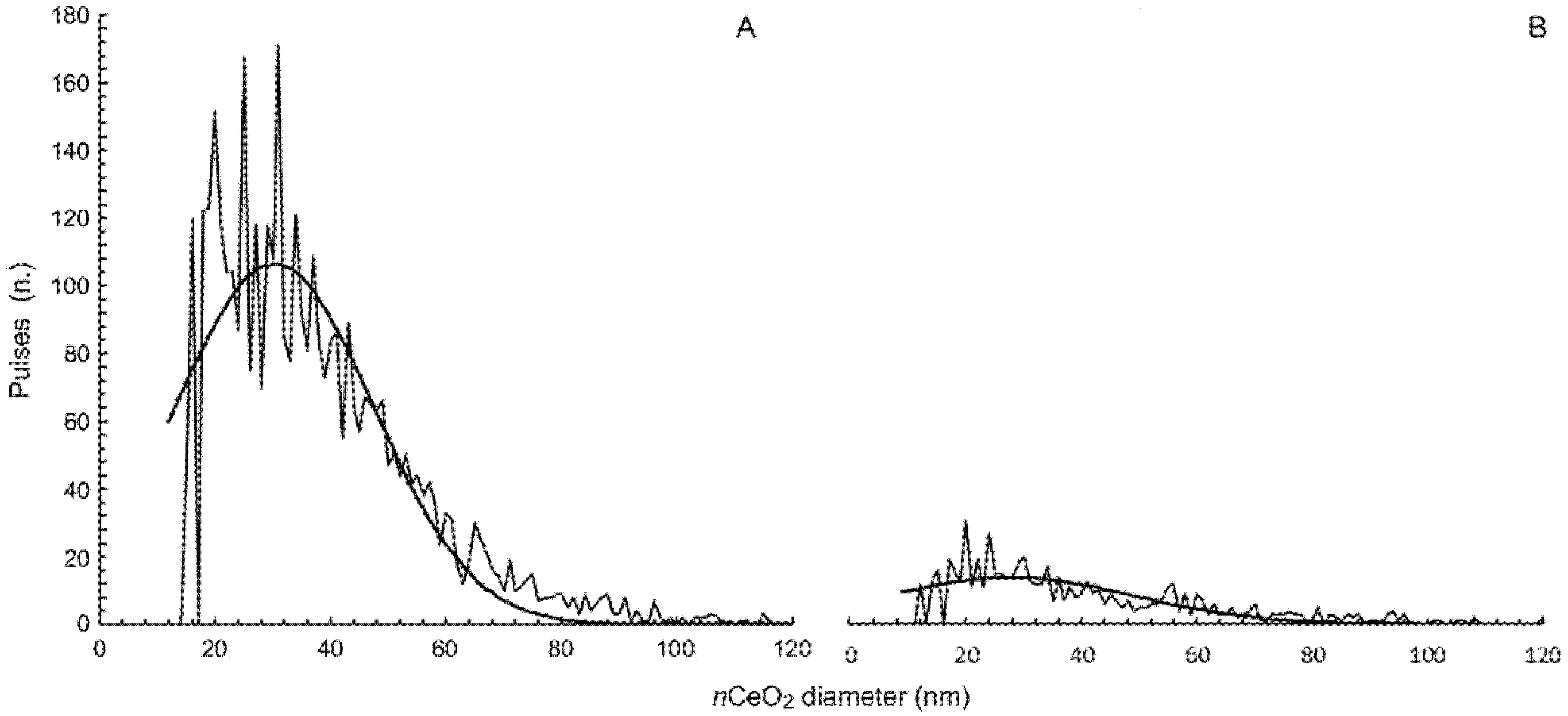

2.1. nCeO2 Characterization

2.2. Plant Material

2.3. Experimental Setup

2.4. nCeO2 Extraction from Plant Tissues

2.5. Ce Concentration in Plant Fractions

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of nCeO2

3.2. nCeO2 in Plant Fractions

3.3. Plant Growth

3.4. Cerium Concentration in Plant Fractions

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hull, M.S.; Bowman, D.M. Nanotechnology Environmental Health and Safety. In Risks, Regulation, and Management, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Meesters, J.A.J.; Quik, J.T.K.; Koelmans, A.A.; Hendriks, A.J.; van de Meent, D. Multimedia environmental fate and speciation of engineered nanoparticles: A probabilistic modeling approach. Environ. Sci. Nano 2016, 3, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holden, P.A.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L.; Klaessig, F.; Turco, R.F.; Mortimer, M.; Hund-Rinke, K.; Cohen Hubal, E.A.; Avery, D.; Barceló, D.; Behra, R.; et al. Considerations of environmentally relevant test conditions for improved evaluation of ecological hazards of engineered nanomaterials. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 6124–6145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hund-Rinke, K.; Baun, A.; Cupi, D.; Fernandes, T.F.; Handy, R.; Kinross, J.H.; Navas, J.M.; Peijnenburg, W.; Schlich, K.; Shaw, B.J.; et al. Regulatory ecotoxicity testing of nanomaterials—Proposed modifications of OECD test guidelines based on laboratory experience with silver and titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Nanotoxicology 2016, 10, 1442–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rasmussen, K.; Rauscher, H.; Kearns, P.; González, M.; Riego Sintes, J. Developing OECD test guidelines for regulatory testing of nanomaterials to ensure mutual acceptance of test data. Reg. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 104, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, Y.M.; Phillips, R.; Milo, R. The biomass distribution on Earth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 16506–16511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Isbell, F.; Calcagno, V.; Hector, A.; Connolly, J.; Stanley Harpole, W.; Reich, P.B.; Scherer-Lorenzen, M.; Schmid, B.; Tilman, D.; van Ruijven, J.; et al. High plant diversity is needed to maintain ecosystem services. Nature 2011, 477, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kah, M.; Kookana, R.S.; Gogos, A.; Bucheli, T.D. A critical evaluation of nanopesticides and nanofertilizers against their conventional analogues. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, E.J.; Mortimer, M.; Burgess, R.M.; Handy, R.; Hanna, S.; Ho, K.T.; Johnson, M.; Loureiro, S.; Henriette Selck, H.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.J.; et al. Strategies for robust and accurate experimental approaches to quantify nanomaterial bioaccumulation across a broad range of organisms. Environ. Sci. Nano 2019, 6, 1619–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuverza-Mena, N.; Martínez-Fernández, D.; Du, W.; Hernandez-Viezcas, J.A.; Bonilla-Bird, N.; López-Moreno, M.L.; Komárek, M.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Exposure of engineered nanomaterials to plants: Insights into the physiological and biochemical responses—A review. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 110, 236–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, X.; Yan, J. Plant uptake and accumulation of engineered metallic nanoparticles from lab to field conditions. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2018, 6, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.Y.; Gottschalk, F.; Hungerbuhler, K.; Nowack, B. Comprehensive probabilistic modelling of environmental emissions of engineered nanomaterials. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 185, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonelli, A.; Fry, C.; Smith, R.J.; Simmonds, M.S.J.; Kersey, P.J.; Pritchard, H.W.; Sofo, A.; Haelewaters, D.; Gâteblé, G. State of the World’s Plants and Fungi 2020; Royal Botanic Gardens: Kew, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wiersema, J.H.; Léon, B. World Economic Plants: A Standard Reference; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Janick, J. New crops and the search for new food resources. In Perspectives on New Crops and New Uses; Janick, J., Ed.; ASHS Press: Alexandria, VA, USA, 1999; pp. 281–304. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.R.B.; Nayak, V.; Sarkar, T.; Singh, R.P. Cerium oxide nanoparticles: Properties, biosynthesis and biomedical application. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 27194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccinno, F.; Gottschalk, F.; Seeger, S.; Nowack, B. Industrial production quantities and uses of ten engineered nanomaterials in Europe and the world. J. Nanopart. Res. 2012, 14, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- OECD. ENV/JM/MONO(2010)46-List of Manufactured Nanomaterials and List of Endpoints for Phase One of the Sponsorship Programme for the Testing of Manufactured Nanomaterials: Revision; OECD: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Bai, X.; Ye, Z.; Ma, L.; Liang, L. Toxicological responses of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on Eichhornia crassipes and associated plant transportation. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 671, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekperusia, A.O.; Sikokic, F.D.; Nwachukwud, E.O. Application of common duckweed (Lemna minor) in phytoremediation of chemicals in the environment: State and future perspective. Chemosphere 2019, 223, 285–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geitner, N.K.; Cooper, J.L.; Avellan, A.; Castellon, B.T.; Perrotta, B.G.; Bossa, N.; Simonin, M.; Anderson, S.M.; Inoue, S.; Hochella, M.F.; et al. Size-based differential transport, uptake, and mass distribution of ceria (CeO2) nanoparticles in wetland mesocosms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 9768–9776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Colman, B.P.; McGill, B.M.; Wright, J.P.; Bernhardt, E.S. Effects of silver nanoparticle exposure on germination and early growth of eleven wetland plants. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jacob, D.L.; Borchardt, J.D.; Navaratnam, L.; Otte, M.L.; Bezbaruah, A.N. Uptake and translocation of Ti nanoparticles in crops and wetland plants. Int. J. Phytorem. 2013, 15, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, U.; Lee, S. Phytotoxicity and accumulation of zinc oxide nanoparticles on the aquatic plants Hydrilla verticillata and Phragmites australis: Leaf-type-dependent responses. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 8539–8545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrowicz-Trzcińska, M.; Bederska-Błaszczyk, M.; Szaniawski, A.; Olchowik, J.; Studnicki, M. The effects of copper and silver nanoparticles on container-grown Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) and Pedunculate Oak (Quercus robur L.) seedlings. Forests 2019, 10, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Servin, A.D.; White, J.C. Nanotechnology in agriculture: Next steps for understanding engineered nanoparticle exposure and risk. NanoImpact 2016, 1, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalas, J.; Suominen, J. Atlas Florae Europaeae (AFE)—Distribution of Vascular Plants in Europe 7 (Caryophyllaceae (Silenioideae)); Committee for Mapping the Flora of Europe and Societas Biologica Fennica Vanamo: Vanamo, Helsinki, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Aavik, T.; Holderegger, R.; Bolliger, J. The structural and functional connectivity of the grassland plant Lychnis flos-cuculi. Heredity 2014, 112, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Biere, A. Parental effects in Lychnis flos-cuculi L.: Seed size, germination and seedling performance in a controlled environment. J. Evol. Biol. 1999, 4, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Lamana, J.; Wojcieszek, J.; Jakubiak, M.; Asztemborska, M.; Szpunar, J. Single particle ICP-MS characterization of platinum nanoparticles uptake and bioaccumulation by Lepidium sativum and Sinapis alba plants. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2016, 31, 2321–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US EPA. EPA Method 3052. Microwave assisted acid digestion of siliceous and organically based matrices in US Environmental Protection Agency. In Test Methods for Evaluating Solid Waste; US EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lizzi, D.; Mattiello, A.; Piani, B.; Fellet, G.; Adamiano, A.; Marchiol, L. Germination and early development of three spontaneous plant species to nanoceria (nCeO2) with different concentrations and particle sizes. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priester, J.H.; Ge, Y.; Mielke, R.E.; Horst, A.M.; Moritz, S.C.; Espinosa, K.; Gelb, J.; Walker, S.L.; Nisbet, R.M.; An, Y.J.; et al. Soybean susceptibility to manufactured nanomaterials with evidence for food quality and soil fertility interruption. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 2451–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- López-Moreno, M.L.; De La Rosa, G.; Hernandez-Viezcas, J.A.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) corroboration of the uptake and storage of CeO2 nanoparticles and assessment of their differential toxicity in four edible plant species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 3689–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mattiello, A.; Pošćić, F.; Musetti, R.; Giordano, C.; Vischi, M.; Filippi, A.; Bertolini, A.; Marchiol, L. Evidences of genotoxicity and phytotoxicity in Hordeum vulgare exposed to CeO2 and TiO2 nanoparticles. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andersen, C.P.; King, G.; Plocher, M.; Storm, M.; Pokhrel, L.R.; Johnson, M.G.; Rygiewicz, P.T. Germination and early plant development of ten plant species exposed to titanium dioxide and cerium oxide nanoparticles. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2016, 35, 2223–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, C.M.; Morales, M.I.; Barrios, A.C.; McCreary, R.; Hong, J.; Lee, W.Y.; Nunez, J.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Effect of cerium oxide nanoparticles on the quality of rice (Oryza sativa L.) grains. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 11278–11285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, A.C.; Medina-Velo, I.A.; Zuverza-Mena, N.; Dominguez, O.D.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Nutritional quality assessment of tomato fruits after exposure to uncoated and citric acid coated cerium oxide nanoparticles, bulk cerium oxide, cerium acetate and citric acid. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 110, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, P.; Ma, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, G.; Zhang, J.; He, X.; Zhang, J.; Rui, Y.; Zhang, Z. Phytotoxicity, uptake and transformation of nano-CeO2 in sand cultured romaine lettuce. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 220, 1400–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Servin, A.D.; De La Torre-Roche, R.; Castillo-Michel, H.; Pagano, L.; Hawthorne, J.; Musante, C.; Pignatello, J.; Uchimiya, M.; White, J.C. Exposure of agricultural crops to nanoparticle CeO2 in biochar-amended soil. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 110, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gunn, S.; Farrar, J.F.; Collis, B.E.; Nason, M. Specific leaf area in barley: Individual leaves versus whole plants. New Phytol. 1999, 143, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchiol, L.; Mattiello, A.; Pošćić, F.; Fellet, G.; Zavalloni, C.; Carlino, E.; Musetti, R. Changes in physiological and agronomical parameters of barley (Hordeum vulgare) exposed to cerium and titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cao, Z.; Stowers, C.; Rossi, L.; Zhang, W.; Lombardini, L.; Ma, X. Physiological effects of cerium oxide nanoparticles on the photosynthesis and water use efficiency of soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.). Environ. Sci. Nano 2017, 4, 1086–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodea-Palomares, I.; Gonzalo, S.; Santiago-Morales, X.; Leganés, F.; García-Calvo, E.; Rosal, R.; Fernández-Piñas, F. An insight into the mechanisms of nanoceria toxicity in aquatic photosynthetic organisms. Aquati. Toxicol. 2012, 122–123, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, B.; Klaessig, F.; Park, P.; Kaegi, R.; Steinfeldt, M.; Wigger, H.; von Gleich, A.; Gottschalk, F. Risks, release and concentrations of engineered nanomaterial in the environment. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlich, K.; Beule, L.; Hund-Rinke, K. Single versus repeated applications of CuO and Ag nanomaterials and their effect on soil microflora. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 215, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Xue, L.; Eivazi, F.; Afrasiabi, Z. Size, concentration, coating, and exposure time effects of silver nanoparticles on the activities of selected soil enzymes. Geoderma 2021, 381, 114682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Dose | RMF | SLA |

|---|---|---|---|

| (g g−1) | (m2 kg−1) | ||

| Ctrl | D0 | 0.054 ± 0.003 c | 25.3 ± 0.70 ab |

| nCeO2 20 mg kg−1 | D1 | 0.117 ± 0.009 a | 25.7 ± 1.21 ab |

| D2 | 0.078 ± 0.008 bc | 27.3 ± 1.32 ab | |

| D3 | 0.077 ± 0.007 bc | 24.4 ± 1.42 b | |

| p = 0.0028 ** | p = 0.2801 ns | ||

| nCeO2 200 mg kg−1 | D1 | 0.105 ± 0.009 ab | 24.1 ± 1.31 b |

| D2 | 0.087 ± 0.01 abc | 28 ± 1.63 ab | |

| D3 | 0.070 ± 0.006 c | 30 ± 1.36 a | |

| p = 0.0271 * | p = 0.0243 * |

| Treatment | Dose | Ce roots | Ce stems | Ce leaves |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (µg kg−1) | (µg kg−1) | (µg kg−1) | ||

| Ctrl | D0 | 546 ± 390 b | 154 ± 125 b | 254 ± 198 b |

| nCeO2 20 mg kg−1 | D1 | 1300 ± 112 b | 333 ± 281 b | 1083 ± 70 ab |

| D2 | 2407 ± 793 b | 477 ± 172 ab | 1240 ± 170 ab | |

| D3 | 2670 ± 1130 b | 1450 ± 918 a | 1770 ± 96.7 a | |

| p = 0.1653 ns | p = 0.0988 ns | p = 0.3638 ns | ||

| nCeO2 200 mg kg−1 | D1 | 3023 ± 700 ab | 573 ± 87 ab | 1580 ± 60.7 ab |

| D2 | 3130 ± 2210 ab | 816 ± 91 ab | 2063 ± 41.8 a | |

| D3 | 5910 ± 1140 a | 1023 ± 61 ab | 1827 ± 24 a | |

| p = 0.0941 ns | p = 0.0015 ** | p = 0.4643 ns |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lizzi, D.; Mattiello, A.; Piani, B.; Gava, E.; Fellet, G.; Marchiol, L. Single and Repeated Applications of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Differently Affect the Growth and Biomass Accumulation of Silene flos-cuculi L. (Caryophyllaceae). Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11010229

Lizzi D, Mattiello A, Piani B, Gava E, Fellet G, Marchiol L. Single and Repeated Applications of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Differently Affect the Growth and Biomass Accumulation of Silene flos-cuculi L. (Caryophyllaceae). Nanomaterials. 2021; 11(1):229. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11010229

Chicago/Turabian StyleLizzi, Daniel, Alessandro Mattiello, Barbara Piani, Emanuele Gava, Guido Fellet, and Luca Marchiol. 2021. "Single and Repeated Applications of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Differently Affect the Growth and Biomass Accumulation of Silene flos-cuculi L. (Caryophyllaceae)" Nanomaterials 11, no. 1: 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11010229

APA StyleLizzi, D., Mattiello, A., Piani, B., Gava, E., Fellet, G., & Marchiol, L. (2021). Single and Repeated Applications of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Differently Affect the Growth and Biomass Accumulation of Silene flos-cuculi L. (Caryophyllaceae). Nanomaterials, 11(1), 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11010229