Carbon Nanotube Films with Fewer Impurities and Higher Conductivity from Aqueously Mono-Dispersed Solution via Two-Step Filtration for Electric Heating

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of CNT Films

2.3. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mechanism of Two-Step Filtration

3.2. Characterization of CNT Films

3.3. Hydrophilic Properties of CNT Films

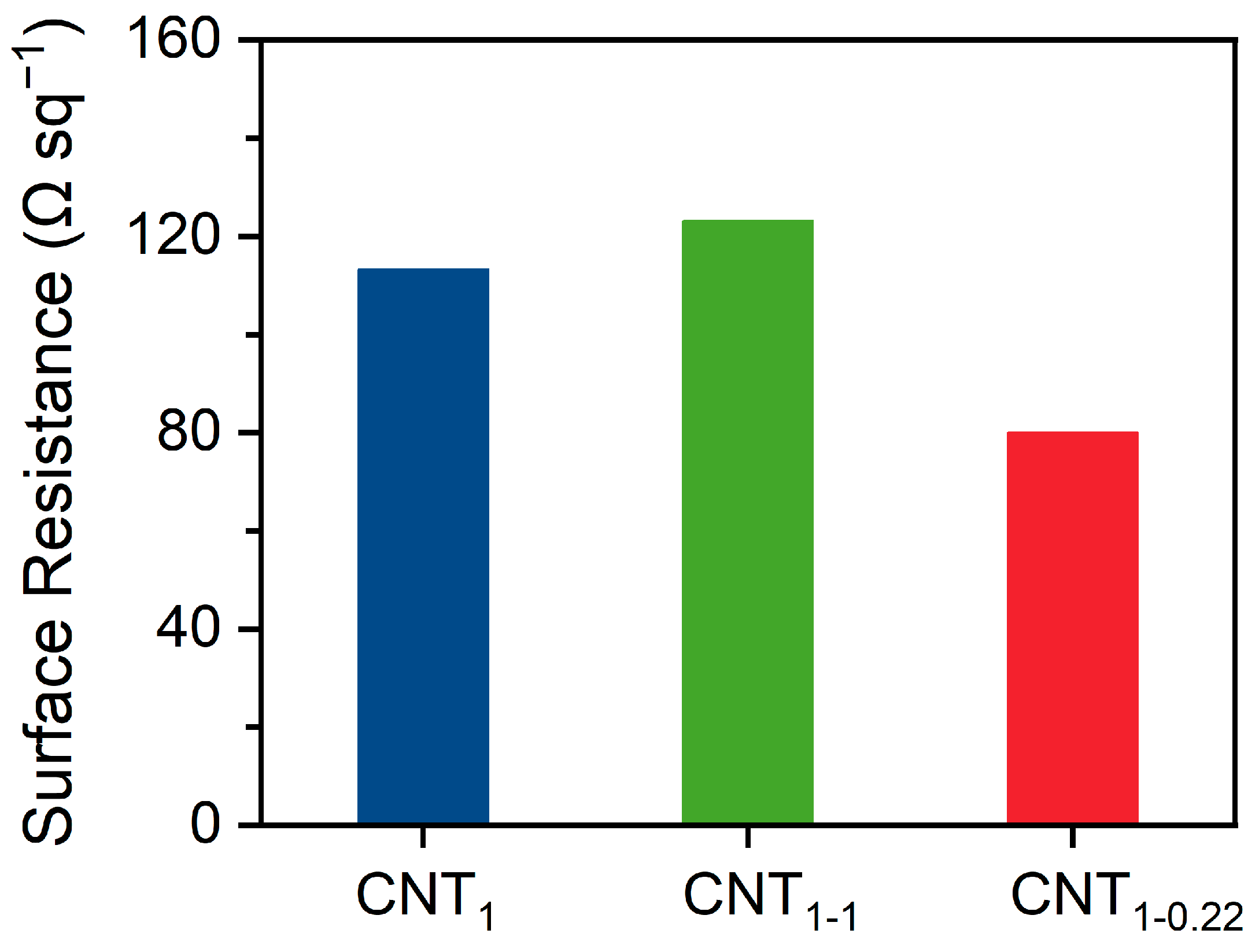

3.4. Electrical Properties of CNT Films

3.5. Thermal Properties of CNT Films

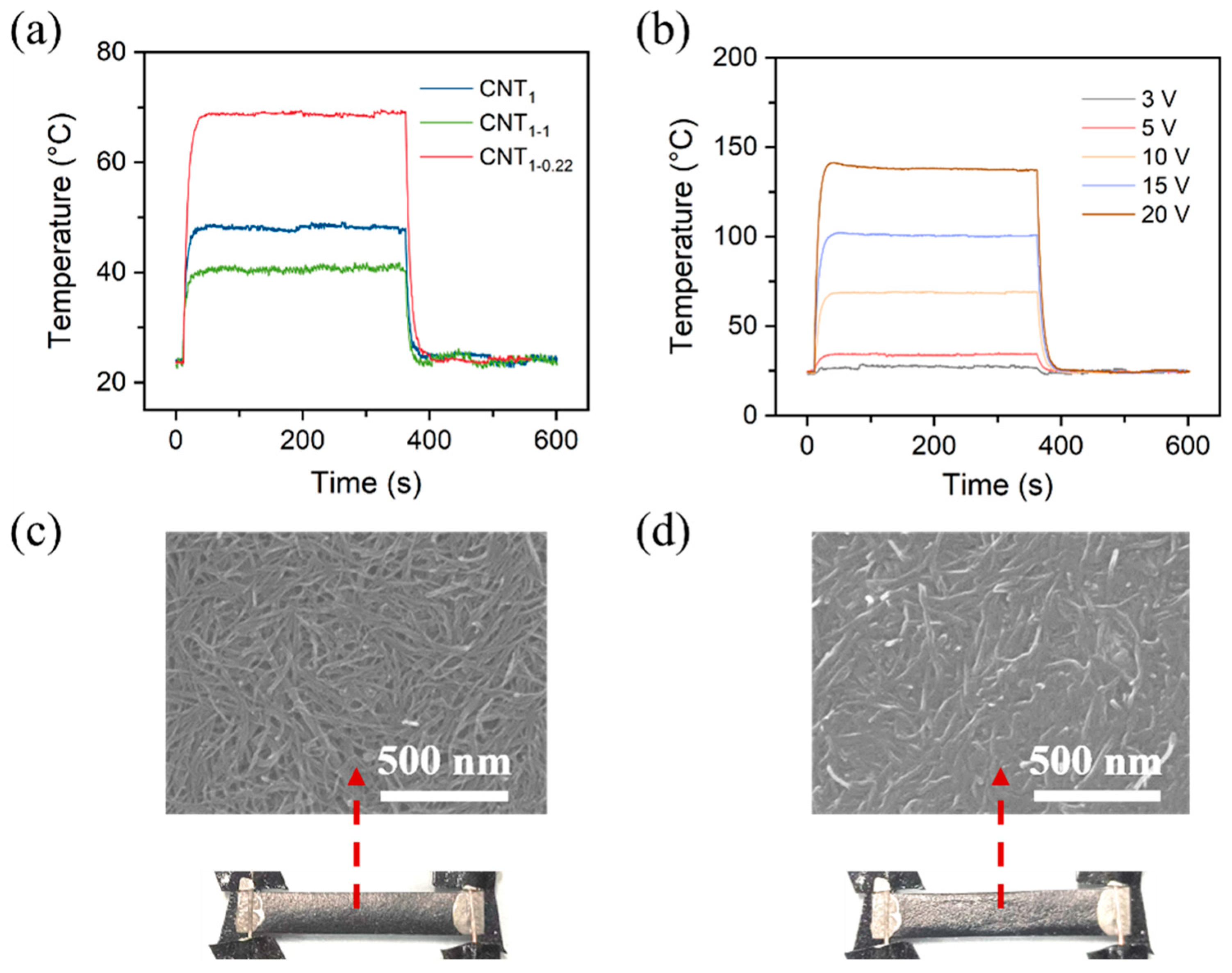

3.5.1. Thermal Properties at Constant Voltage

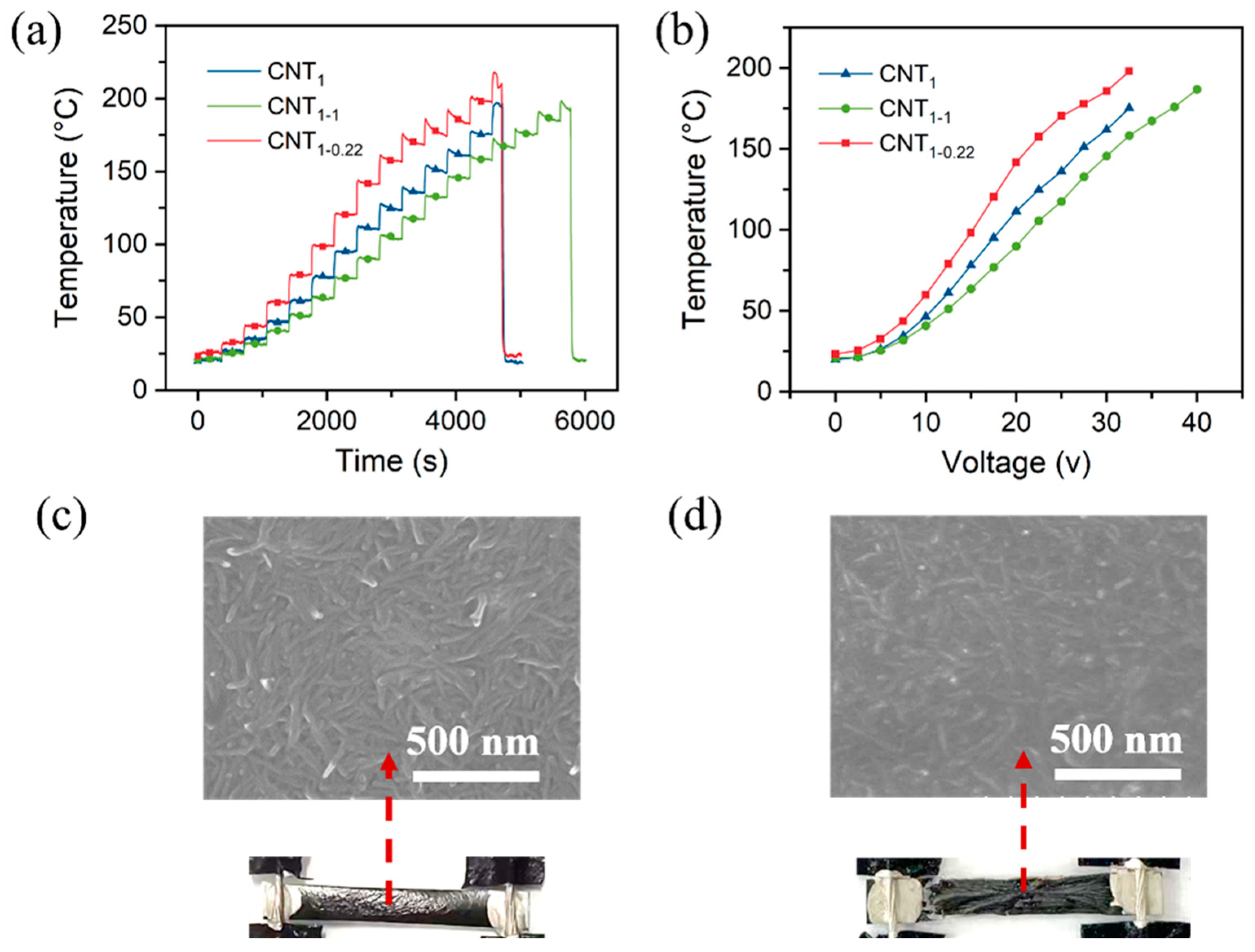

3.5.2. Thermal Properties with Increasing Voltage

3.5.3. Stable Performance

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, Z.; Lu, H.; Zhao, W.; Chang, X. Materials, performances and applications of electric heating films. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 184, 113540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Wang, R.; Ni, H.; Liu, H.; Liu, L. A review of flexible electric heating element and electric heating garments. J. Ind. Text 2020, 51, 101S–136S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janas, D.; Koziol, K.K. A review of production methods of carbon nanotube and graphene thin films for electrothermal applications. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 3037–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Lin, Z.; Han, M.; Mu, Y.; Yu, J. Electrospun carbon nanofiber-based flexible films for electric heating elements with adjustable resistance, ultrafast heating rate, and high infrared emissivity. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 14542–14555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, T.; Pan, K.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Afroj, S.; Novoselov, K.S.; Hu, Z. Screen-Printed Graphite Nanoplate Conductive Ink for Machine Learning Enabled Wireless Radiofrequency-Identification Sensors. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 6197–6208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xie, C.; Yang, S.; He, R.; Guo, Y.; Guo, Z.-X.; Guo, B.; Tuo, X. Aramid-based electric heating films by incorporating carbon black. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 34, 105105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.-E.; Jeong, Y.G. Structure and electric heating performance of graphene/epoxy composite films. Eur. Polym. J. 2013, 49, 1322–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Lu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Yao, Y.; Chen, M.; Li, Q. Flexible carbon nanotube/polyurethane electrothermal films. Carbon 2016, 110, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, D.; Wagner, G.J.; Liu, W.K. Mechanics of carbon nanotubes. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2002, 55, 495–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berber, S.; Kwon, Y.-K.; Tománek, D. Unusually high thermal conductivity of carbon nanotubes. In High Thermal Conductivity Materials; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 227–265. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, P.; Shi, L.; Majumdar, A.; McEuen, P.L. Thermal Transport Measurements of Individual Multiwalled Nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 87, 215502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Tran, B.; Zhai, L. Fabrication of metal nanoparticles on highly dispersed pristine carbon nanotubes. Int. J. Smart Nano Mater. 2011, 2, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, B.; Kim, H.G.; Lee, J.-H.; Arepalli, S.; Nah, C. Carbon nanotube-reinforced elastomeric nanocomposites: A review. Int. J. Smart Nano Mater. 2016, 6, 211–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujigaya, T.; Nakashima, N. Non-covalent polymer wrapping of carbon nanotubes and the role of wrapped polymers as functional dispersants. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2015, 16, 024802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.Y.; Xu, Y.J.; Duo, S.W.; Zhang, R.F.; Li, M.S. Non-Covalent Functionalization of Carbon Nanotubes with Surfactants and Polymers. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2013, 56, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleemi, M.A.; Fouladi, M.H.; Yong, P.V.C.; Wong, E.H. Elucidation of Antimicrobial Activity of Non-Covalently Dispersed Carbon Nanotubes. Materials 2020, 13, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, H.; Aiswarya, R.; Surendran, K.P. Screen printable MWCNT inks for printed electronics. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 44076–44081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.D.; de Andrade, M.J.; Skákalová, V.; Nobre, F.; Bergmann, C.P.; Roth, S. In-situ synthesis of transparent and conductive carbon nanotube networks. Phys. Status Solidi Rapid Res. Lett. 2007, 1, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, M.; Small, J.P.; Steiner, M.; Freitag, M.; Green, A.A.; Hersam, M.C.; Avouris, P. Thin film nanotube transistors based on self-assembled, aligned, semiconducting carbon nanotube arrays. ACS Nano 2008, 2, 2445–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Gao, L.; Sun, J. Production of aqueous colloidal dispersions of carbon nanotubes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003, 260, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, S.; Kamada, F.; Futaba, D.N.; Yumura, M.; Hata, K. Influence of lengths of millimeter-scale single-walled carbon nanotube on electrical and mechanical properties of buckypaper. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, I.; Verma, A.; Kaur, I.; Bharadwaj, L.M.; Bhatia, V.; Jain, V.K.; Bhatia, C.S.; Bhatnagar, P.K.; Mathur, P.C. The effect of length of single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) on electrical properties of conducting polymer–SWNT composites. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2009, 48, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.V.; Francisco, W.; Menezes, B.R.C.; Brito, F.S.; Coutinho, A.S.; Cividanes, L.S.; Coutinho, A.R.; Thim, G.P. Correlation of surface treatment, dispersion and mechanical properties of HDPE/CNT nanocomposites. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 389, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.H.; Song, J.W.; Kim, D.; Kim, J.; Park, J.K.; Oh, S.K.; Han, C.S. Transparent Film Heater Using Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19, 4284–4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Ding, X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, L. Scalable electric heating paper based on CNT/Aramid fiber with superior mechanical and electric heating properties. Compos. Part B-Eng. 2021, 224, 109242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, Q.; Shen, J. Correlation between Porosity and Electrical-Mechanical Properties of Carbon Nanotube Buckypaper with Various Porosities. J. Nanomater 2015, 16, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, Y.J.; Yun, C.H.; Kim, W.N.; Lee, H.S. The effect of mesoscopic shape on thermal properties of multi-walled carbon nanotube mats. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2011, 11, 1144–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, A.; Shariaty-Niasar, M.; Rashidi, A.M.; Khodafarin, R. Effect of CNT structures on thermal conductivity and stability of nanofluid. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer 2012, 55, 1529–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jiang, D. Influence of geometries of multi-walled carbon nanotubes on the pore structures of Buckypaper. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2012, 43, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jiang, D.; Peng, H.-X. A pressurized filtration technique for fabricating carbon nanotube buckypaper: Structure, mechanical and conductive properties. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2014, 184, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhu, J. Enhanced direct steam generation via a bio-inspired solar heating method using carbon nanotube films. Powder Technol. 2017, 321, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; He, Q. Preparation of superhydrophobic conductive CNT/PDMS film on paper by foam spraying method. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 648, 129327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tantawy, F. Joule heating treatments of conductive butyl rubber/ceramic superconductor composites: A new way for improving the stability and reproducibility? Eur. Polym. J. 2001, 37, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tantawy, F.; Kamada, K.; Ohnabe, H. In situ network structure, electrical and thermal properties of conductive epoxy resin–carbon black composites for electrical heater applications. Mater. Lett. 2002, 56, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.-W.; Lee, S.-E.; Jeong, Y.G. Carbon nanotube/cellulose papers with high performance in electric heating and electromagnetic interference shielding. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2016, 131, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Li, H.; Lai, X.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wu, W.; Zeng, X. Vacuum-assisted layer-by-layer superhydrophobic carbon nanotube films with electrothermal and photothermal effects for deicing and controllable manipulation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 16910–16919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, T.; Liang, H.-L.; Taimur, M.; Chiodarelli, N.; Khawaja, H.A.; Edvardsen, K.; de Volder, M. Roll to roll coating of carbon nanotube films for electro thermal heating. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2021, 182, 103210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-Q.; Lou, T.-J.; Wang, T.; Cao, W.; Zhao, H.; Qian, P.-F.; Bao, Z.-L.; Yuan, X.-T.; Geng, H.-Z. Flexible Electrothermal Laminate Films Based on Tannic Acid-Modified Carbon Nanotube/Thermoplastic Polyurethane Composite. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 7844–7852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Pu, H.; He, P.; Zhao, Q.; Pan, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C. Robust cellulose-carbon nanotube conductive fibers for electrical heating and humidity sensing. Cellulose 2021, 28, 7877–7891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Park, J.G.; Kim, Y.K.; Lim, Y.J.; Kang, J.-W.; Kim, E.S.; Kwon, J.Y.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, S.H. An active carbon-nanotube polarizer-embedded electrode and liquid-crystal alignment. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 17698–17702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustero, I.; Gaztelumendi, I.; Obieta, I.; Mendizabal, M.A.; Zurutuza, A.; Ortega, A.; Alonso, B. Free-standing graphene films embedded in epoxy resin with enhanced thermal properties. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2020, 3, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjadi, M.; Sitti, M. Self-Sensing Paper Actuators Based on Graphite–Carbon Nanotube Hybrid Films. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1800239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Voltage (V) | (s) | R2 | (s) | R2 | (mW/°C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNT1 | 10 | 6.38 ± 0.03 | 0.99 | 6.60 ± 0.03 | 0.93 | 5.26 |

| CNT1-1 | 10 | 5.83 ± 0.04 | 0.97 | 6.32 ± 0.05 | 0.88 | 6.75 |

| CNT1-0.22 | 10 | 8.21 ± 0.20 | 0.97 | 9.4 ± 0.106 | 0.98 | 3.36 |

| Materials | Thickness (μm) | Resistance (Ω sq−1) | Thermal | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ODA-(MWCNT-COOH/MWCNT-NH2)6 film | 5.6 | 1160 | 60 °C at 30 V | [36] |

| CNT film (CNT suspension 2 wt%) | \ | 6530 | 50.3 °C at 35 V | [37] |

| CNT film (CNT suspension 3 wt%) | 20,540 | 22.8 °C at 35 V | ||

| MWCNT content 0.5 wt% | 220 | \ | 35 °C at 10 V | [38] |

| MWCNT content 0.75 wt% | 48 °C at 10 V | |||

| MWCNT content 1 wt% | 80 °C at 10 V | |||

| C/CNT-20% fiber | \ | \ | 55 °C at 9 V | [39] |

| CNT/PMIA paper | 230 °C at 20 V | [25] | ||

| P-ECS | 3.6 | 340 | \ | [40] |

| CNT BP | 52 | 2.6 | \ | [41] |

| Graphite film | \ | 771 ± 69 | \ | [42] |

| CNT film | 247 ± 8 | |||

| Graphite and CNT hybrid films | 99 ± 9 | |||

| This work | 1.2 | 80 | 70 °C at 10 V |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chu, Y.; Sun, L.; Wang, J.; Han, Z.; Wei, C.; Han, C.; Yan, H. Carbon Nanotube Films with Fewer Impurities and Higher Conductivity from Aqueously Mono-Dispersed Solution via Two-Step Filtration for Electric Heating. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 911. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14110911

Chu Y, Sun L, Wang J, Han Z, Wei C, Han C, Yan H. Carbon Nanotube Films with Fewer Impurities and Higher Conductivity from Aqueously Mono-Dispersed Solution via Two-Step Filtration for Electric Heating. Nanomaterials. 2024; 14(11):911. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14110911

Chicago/Turabian StyleChu, Yingying, Ling Sun, Jing Wang, Zhaoyang Han, Chenyu Wei, Changbao Han, and Hui Yan. 2024. "Carbon Nanotube Films with Fewer Impurities and Higher Conductivity from Aqueously Mono-Dispersed Solution via Two-Step Filtration for Electric Heating" Nanomaterials 14, no. 11: 911. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14110911