High-Throughput Micro-Combinatorial TEM Phase Mapping of the DC Magnetron Sputtered YxTi1−xOy Thin Layer System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2. Characterization Methods

3. Results

3.1. As Deposited Y-Ti-O Sample

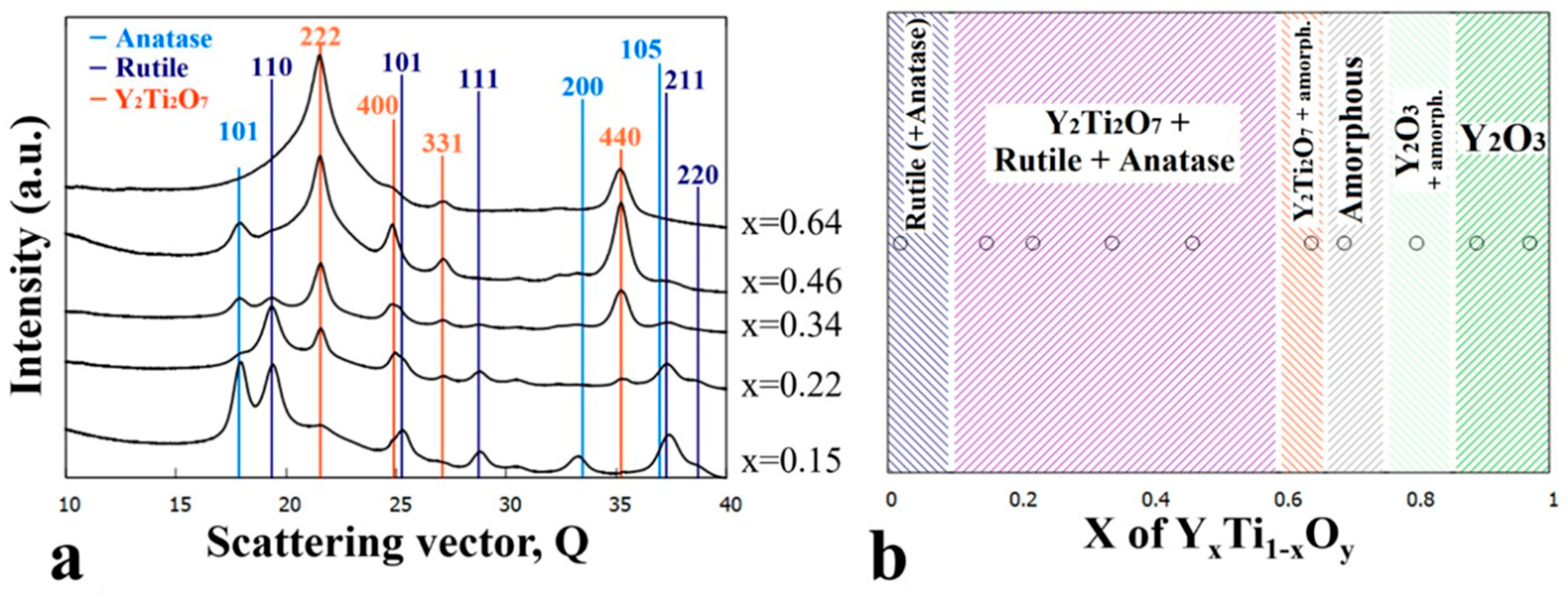

3.2. Sample Annealed at 600 °C

3.3. Sample Annealed at 700 °C

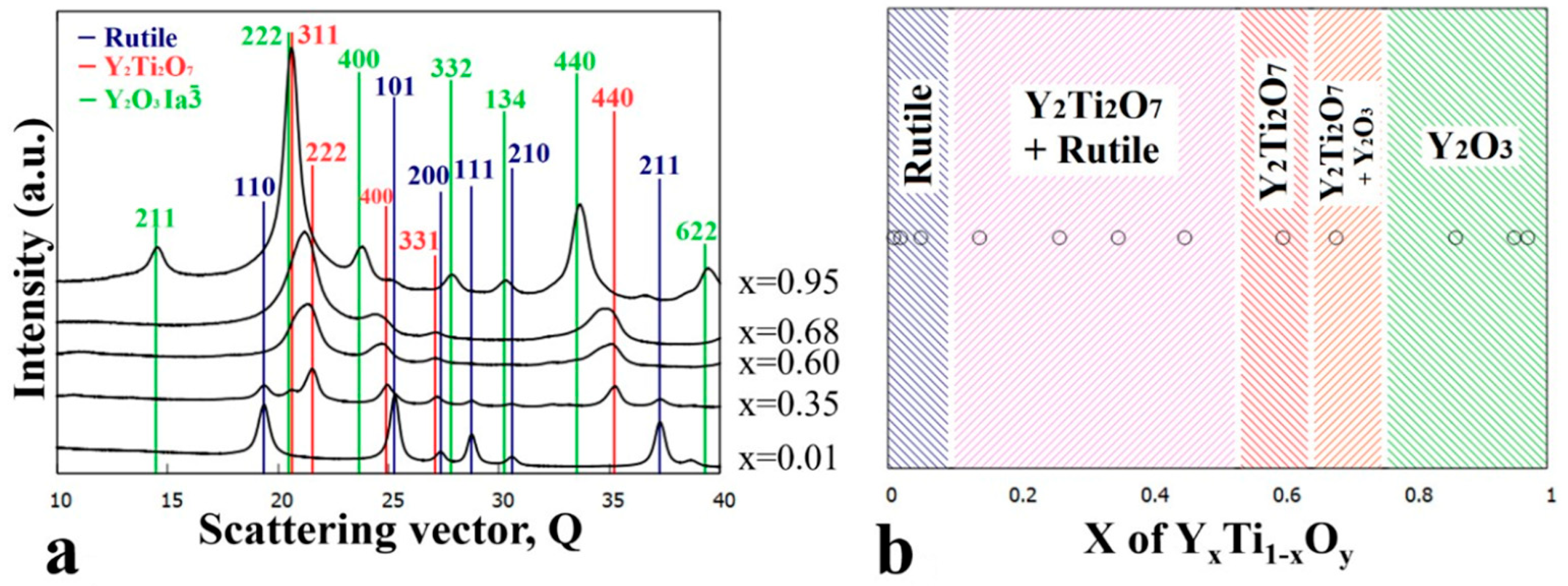

3.4. Sample Annealed at 800 °C

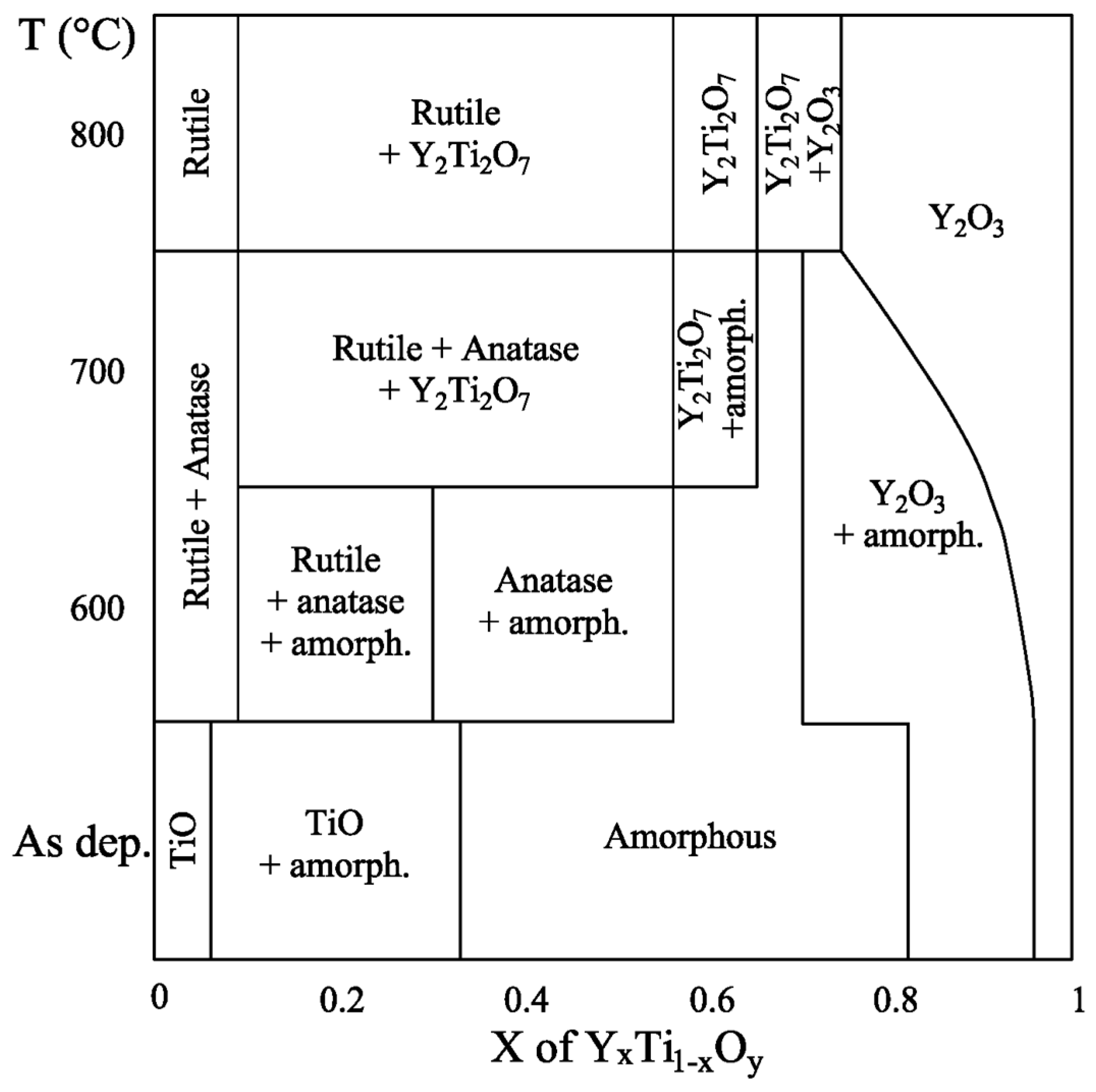

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nagy, P.; Kaszás, B.; Csabai, I.; Hegedűs, Z.; Michler, J.; Pethö, L.; Gubicza, J. Machine Learning-Based Characterization of the Nanostructure in a Combinatorial Co-Cr-Fe-Ni Compositionally Complex Alloy Film. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zrinski, I.; Zavašnik, J.; Duchoslav, J.; Hassel, A.W.; Mardare, A.I. Threshold Switching in Forming-Free Anodic Memristors Grown on Hf-Nb Combinatorial Thin-Film Alloys. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, M.; Bogar, R.; Takacs, D.; Labadi, Z.; Horvath, Z.E.; Zolnai, Z. Investigation of Combinatorial WO3-MoO3 Mixed Layers by Spectroscopic Ellipsometry Using Different Optical Models. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, S.R.; Stanford, M.G.; Vlassiouk, I.V.; Rack, P.D. Combinatorial Cu-Ni Alloy Thin-Film Catalysts for Layer Number Control in Chemical Vapor-Deposited Graphene. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sáfrán, G.; Petrik, P.; Szász, N.; Olasz, D.; Chinh, N.G.; Serényi, M. Review on High-Throughput Micro-Combinatorial Characterization of Binary and Ternary Layers towards Databases. Materials 2023, 16, 3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sáfrán, G. “One-sample concept” micro-combinatory for high throughput TEM of binary films. Ultramicroscopy 2018, 187, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohner, T.; Kalas, B.; Petrik, P.; Zolnai, Z.; Serényi, M.; Sáfrán, G. Refractive Index Variation of Magnetron-Sputtered a-Si1−xGex by “One-Sample Concept” Combinatory. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáfrán, G.; Szász, N.; Dobrik, G.; Kalas, B.; Serényi, M. Smart gas dosage by a peristaltic pump for reactive RF sputtering of composition spread combinatorial hafnium-oxy-nitride layers. Vacuum 2020, 182, 109675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olasz, D.; Sáfrán, G.; Szász, N.; Huhn, G.; Chinh, N.Q. Indentation size effect in exceptionally hard AlCu thin films. Mat. Lett. 2023, 330, 133409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegedüs, N.; Balázsi, C.; Kolonits, T.; Olasz, D.; Sáfrán, G.; Seréneyi, M.; Balázsi, K. Investigation of the RF Sputtering Process and the Properties of Deposited Silicon Oxynitride Layers under Varying Reactive Gas Conditions. Materials 2022, 15, 6313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschler, F.; Neher, D.; Schmidt-Mende, L. Perovskite semiconductors for next generation optoelectronic applications. APL Mater. 2019, 7, 080401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmbrecht, L.; Futscher, M.H.; Muscarella, L.A.; Ehrler, B.; Noorduin, W.L. Ion Exchange Lithography: Localized Ion Exchange Reactions for Spatial Patterning of Perovskite Semiconductors and Insulators. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2005291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvajal, E.; Navarro, O.; Allub, R.; Avignon, M.; Alascio, B. Ferromagnetic transition in ordered double perovskites and related alloys. Eur. Phys. J. B 2005, 48, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.O.; Chapman, J.P.; Hernández-Bocanegra, E.; Insausti, M.; Arriortua, M.I.; Rojo, T. Structural phase transitions in the ordered double perovskite Sr2MnTeO6. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2004, 16, 3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, T.; Kageyama, H.; Ueda, Y. Successive phase transitions in a metal-ordered manganite perovskite YBaMn2O6. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2002, 53, 913–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Hsieh, Y.; Chiu, S.; Ting, C. The effect of annealing on the optoelectronic properties and energy state of amorphous pyrochlore Y2Ti2O7 thin layers by sol-gel synthesis. Crystals 2022, 12, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhou, G.; Xie, J.; Wang, S. Highly transparent yttrium titanate (Y2Ti2O7) ceramics from co-precipitated powders. J. Eur. Ceram. 2019, 39, 3229–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chishkala, V.; Lytovchenko, S.; Mazilin, B.; Gevorkyan, E.; Shkuropatenko, V.; Voyevodin, V.; Rucki, M.; Siemiatkowski, Z.; Matijošius, J.; Dudziak, A.; et al. Novel microwave-assisted method of Y2Ti2O7 powder synthesis. Materials 2020, 13, 5621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganya, M.; Ganesan, K.; Vijayakumar, P.; Gill, A.S.; Ramaseshan, R.; Ganesamoorthy, S. Structural, optical and mechanical properties of Y2Ti2O7 single crystal. Scr. Mater. 2020, 187, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Morall, D.; Zhang, Z.; Yabuuchi, K.; Kimura, A. Radiation response of ODS ferritic steels with different oxide particles under ion-irradiation at 550 °C. J. Nucl. Mater. 2018, 502, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadipelly, T.; Dasgupta, A.; Ghosh, C.; Krupa, V.; Sornadurai, D.; Sahu, B.K.; Dhara, S. Synthesis and structural characterization of Y2Ti2O7 using microwave hydrothermal route. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 814, 152273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karak, S.K.; Majumdar, J.D.; Lojkowski, W.; Michalski, A.; Ciupinski, L.; Kurzydlowski, K.J.; Manna, I. Microstructure and mechanical properties of nano-Y2O3 dispersed ferritic steel synthesized by mechanical alloying and consolidated by pulse plasma sintering. Phil. Mag. 2012, 92, 516–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Yang, M.; Feng, Q.; Liu, T. Influences of adding Y2Ti2O7 and HfH1.98 nanoparticles on the microstructure and mechanical properties of oxide dispersion strengthen steels. Mater. Charact. 2023, 202, 113040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Liu, T.; Bai, Z.; Wang, L.; Gao, W.; Zhang, L. Corrosion behavior of 14Cr ODS steel in supercritical water: The influence of substituting Y2O3 with Y2Ti2O7 nanoparticles. Corros. Sci. 2020, 163, 108272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, L.; Kim, Y.J.; Xu, A.; Karatchevtseva, I.; Scales, N.; Gregg, D.J. Hot isostatically pressed Y2Ti2O7 and Gd2Ti2O7 pyrochlore glass-ceramics as potential waste forms for actinide immobilization. J. Eur. Ceram. 2019, 39, 1546–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, S.; Cannillo, V.; Wu, J.; Boccaccini, D.N.; Seglem, S.; Boccaccini, A.R. Processing glass-pyrochlore composites for nuclear waste encapsulation. J. Nucl. Mater. 2005, 341, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.K.; Pandey, O.P.; Singh, K. Ionic conductivity, structural and thermal properties of pure and Sr2+ doped Y2Ti2O7 pyrochlores for SOFC. Solid State Sci. 2011, 13, 1960–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Xiao, Y.; Han, P.; Zhang, Q. Effects of rare earth oxides on dielectric properties of Y2Ti2O7 series ceramics. J. Rare Earths 2010, 28, 765–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashi, M.; Abe, R.; Sayama, K.; Sugihara, H.; Abe, Y. Improvement of photocatalytic activity of titanate pyrochlore Y2Ti2O7 by addition of excess Y. Chem. Lett. 2005, 34, 1122–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.T.; Nakayama, T.; Suematsu, H.; Suzuki, T.; Nanko, M.; Cho, H.; Huynh, M.T.T.; Jiang, W.; Niihara, K. Synthesis of molten-metal corrosion resistant yttria-based refractory by hot-pressing and densification. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2015, 35, 2651–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Zhou, W.; Gao, H.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, F.; Zhu, D.; Huang, Z.; Qing, Y. Enhanced dielectric and microwave absorption properties of Y2Ti2O7 ceramics by Sr doping. Appl. Phys. A 2019, 125, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, D.; Kaliyaperumal, C.; Mumoorthy, S.; Paramasivam, T. Dependence on the temperature of the electrical properties of nanocrystalline Y2Ti2O7 ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 5426–5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthick, G.; Karati, A.; Murty, B.S. Low temperature synthesis of nanocrystalline Y2Ti2O7, Y2Zr2O7, Y2Hf2O7 with exceptional hardness by reverse co-precipitation technique. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 837, 155491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, T.; Bai, Z.; Wang, C.; Shen, H. Synthesis and characterization of Y2Ti2O7 nanoparticles from Y-Ti hydride nanocomposite at a low sintering temperature. J. Mater. Sci. 2016, 51, 6967–6973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czigány, Z.; Kis, V.K. Acquisition and evaluation procedure to improve the accuracy of SAED. MRT 2023, 86, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lábár, J.L. Electron Diffraction Based Analysis of Phase Fractions and Texture in Nanocrystalline Thin Films, Part I: Principles. Microsc. Microanal. 2008, 14, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olasz, D.; Kis, V.; Cora, I.; Németh, M.; Sáfrán, G. High-Throughput Micro-Combinatorial TEM Phase Mapping of the DC Magnetron Sputtered YxTi1−xOy Thin Layer System. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 925. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14110925

Olasz D, Kis V, Cora I, Németh M, Sáfrán G. High-Throughput Micro-Combinatorial TEM Phase Mapping of the DC Magnetron Sputtered YxTi1−xOy Thin Layer System. Nanomaterials. 2024; 14(11):925. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14110925

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlasz, Dániel, Viktória Kis, Ildikó Cora, Miklós Németh, and György Sáfrán. 2024. "High-Throughput Micro-Combinatorial TEM Phase Mapping of the DC Magnetron Sputtered YxTi1−xOy Thin Layer System" Nanomaterials 14, no. 11: 925. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14110925

APA StyleOlasz, D., Kis, V., Cora, I., Németh, M., & Sáfrán, G. (2024). High-Throughput Micro-Combinatorial TEM Phase Mapping of the DC Magnetron Sputtered YxTi1−xOy Thin Layer System. Nanomaterials, 14(11), 925. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14110925