Intensity Modulation Effects on Ultrafast Laser Ablation Efficiency and Defect Formation in Fused Silica

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

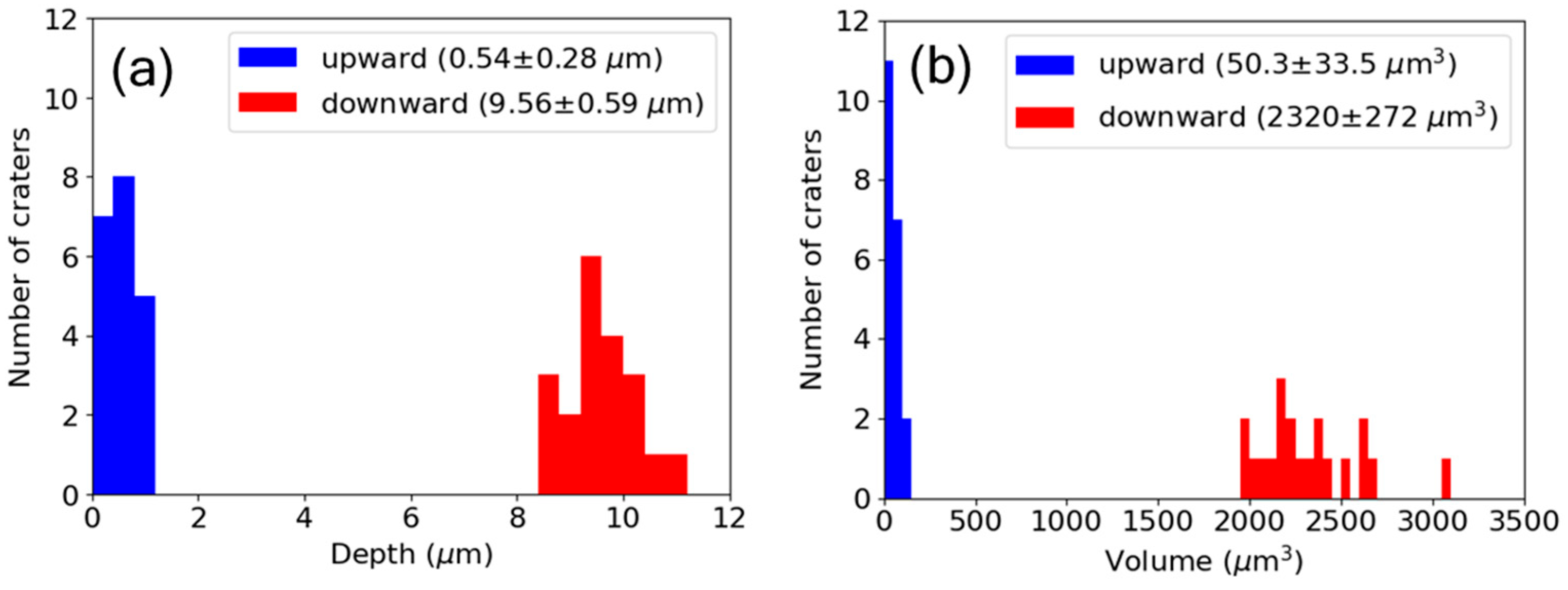

3.1. Ablation Efficiencies Under Upward and Downward Ramps

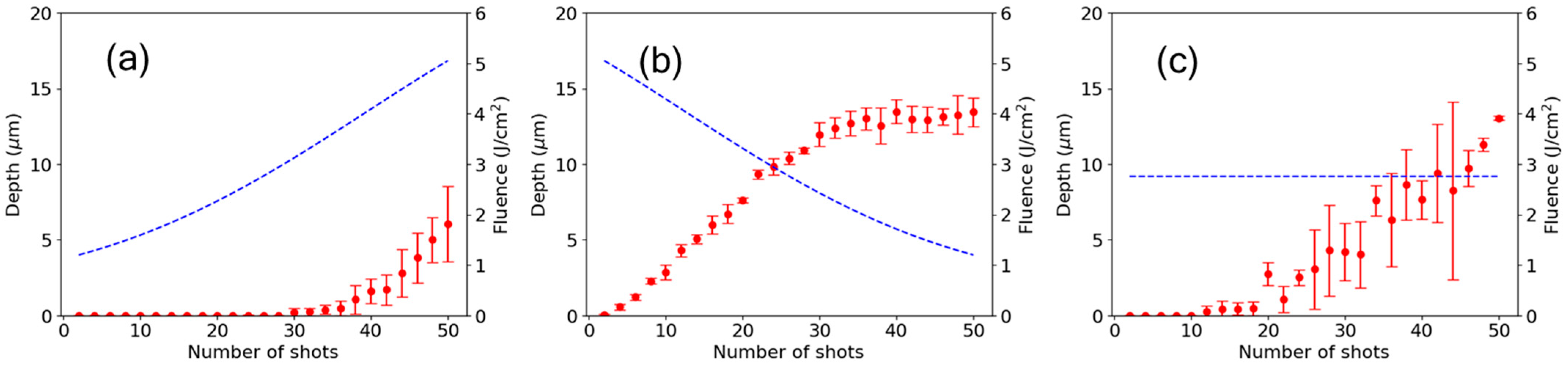

3.2. Shot-To-Shot Ablation Dynamics

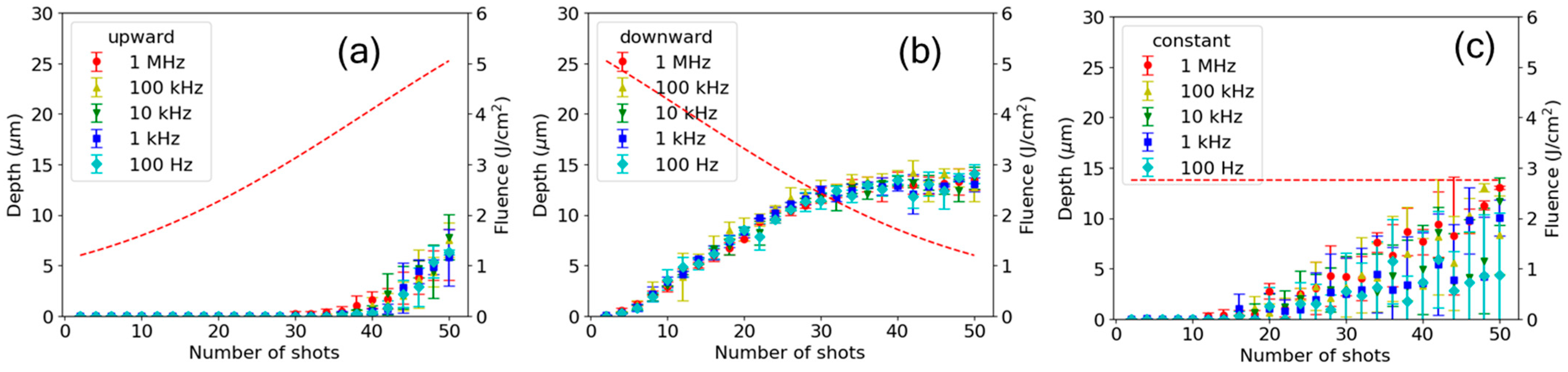

3.3. Repetition Rate Dependence

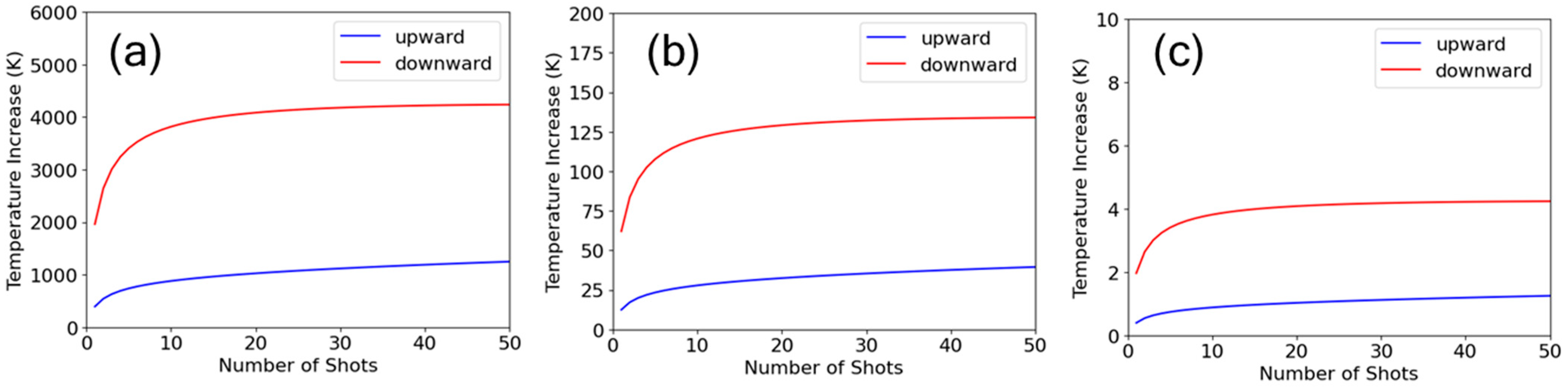

3.4. Transient Residual Effects

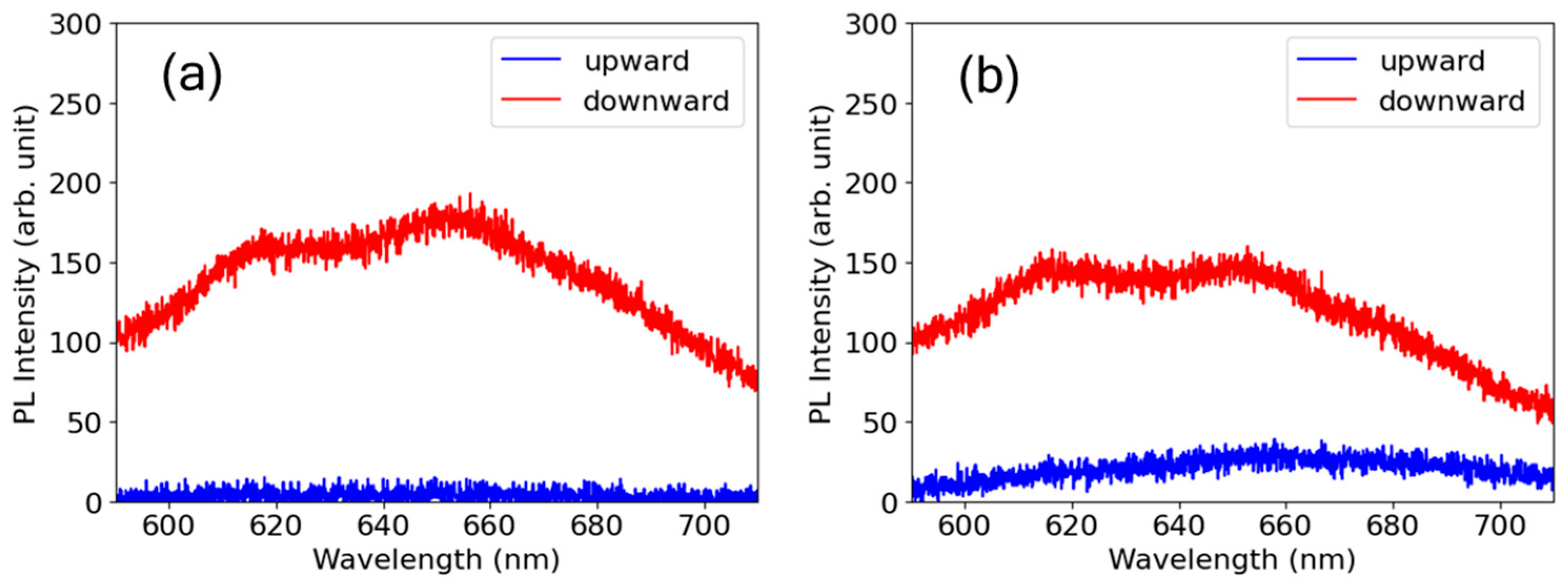

3.5. Photoluminescence Microscopy to Evaluate Defect Formation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LIPSS | Laser-Induced Periodic Surface Structure |

| CPA | Chirped-Pulse Amplification |

| AOM | Acousto-Optical Modulator |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| PL | Photoluminescence |

| STE | Self-Trapped Exciton |

| NBOHC | Non-Bridging Oxygen Hole Center |

References

- Mourou, G.A.; Du, D.; Dutta, S.K.; Elner, V.; Kurtz, R.; Lichter, P.R.; Liu, X.; Pronko, P.P.; Squier, J.A. Method for Controlling Configuration of Laser Induced Beakdown and Ablation. U.S. Patent 5656186, 12 August 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Chichkov, B.N.; Momma, C.; Nolte, S.; von Alvensleben, F.; Tünnermann, A. Femotosecond, picosecond and nanosecond laser ablation of solids. Appl. Phys. A 1996, 63, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rethfeld, B.; Ivanov, D.S.; Garcia, M.E.; Anisimov, S.I. Modeling ultrafast laser ablation. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2017, 50, 193001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, B.C.; Feit, M.D.; Herman, S.; Rubenchik, A.M.; Shore, B.W.; Perry, M.D. Optical ablation by high-power short-pulse lasers. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 1996, 13, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.; Liu, X.; Korn, G.; Squier, J.; Mourou, G. Laser-induced breakdown by impact ionization in SiO2 with pulse widths from 7 ns to 150 fs. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1994, 64, 3071–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, I.H.; Xu, X.; Weiner, A.M. Ultrafast double-pulse ablation of fused silica. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 86, 151110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkenasi, D.; Lorenz, M.; Stoian, R.; Rosenfeld, A. Surface damage threshold and structuring of dielectrics using femtosecond laser pulses: Thre role of incubation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1999, 150, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, A.; Lorenz, M.; Stoian, R.; Ashkenasi, D. Ultrashort-laser-pulse damage threshold of transparent materials and the role of incubation. Appl. Phys. A 1999, 69, S373–S376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Jiang, L.; Li, X.; Shi, X.; Yu, D.; Qu, L.; Lu, Y. Femtosecond laser pulse-train induced breakdown in fused silica: The role of seed electrons. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2014, 47, 435105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.-H.; Young, H.-T.; Li, K.-M. Picosecond dual-pulse laser ablation of fused silica. Appl. Phys. A 2022, 128, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanuka, A.; Wootton, K.P.; Wu, Z.; Soong, K.; Makasyuk, I.V.; England, R.J.; Schächter, L. Cumulative material damage from train of ultrafast infrared laser pulses. High Power Laser Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyaji, G.; Nagai, D.; Miyoshi, T.; Takada, H.; Yoshitomi, D.; Narazaki, A. Stable fabrication of femtosecond-laser-induced periodic nanostructures on glass by using real-time monitoring and active feedback control. Light Adv. Manuf. 2024, accepted. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, A.; Mizuta, T.; Shimotsuma, Y.; Sakakura, M.; Otobe, T.; Shimizu, M.; Miura, K. Picosecond burst pulse machining with temporal energy modulation. Chin. Opt. Lett. 2020, 18, 123801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, J.; Ito, Y.; Sugita, N. Crackless femtosecond laser percussion drilling of SiC by suppressing shock wave magnitude. CIRP Ann. 2023, 72, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balage, P.; Bonamis, G.; Lafargue, M.; Guilberteau, T.; Delaigue, M.; Hönninger, C.; Qiao, J.; Lopez, J.; Manek-Hönninger, I. Advances in femtosecond laser GHz-burst drilling of glasses: Influence of burst shape and duration. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimahara, K.; Tani, S.; Sakurai, H.; Kobayashi, Y. A deep learning-based predictive simulator for the optimization of ultrashort pulse laser drilling. Commun. Eng. 2023, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshitomi, D.; Takada, H.; Torizuka, K.; Kobayashi, Y. 100-W average-power femtosecond fiber laser system with variable paramters for rapid optimization of laser processing. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics, San Jose, CA, USA, 5–10 May 2019. paper SM3L.2. [Google Scholar]

- Narazaki, A.; Takada, H.; Yoshitomi, D.; Torizuka, K.; Kobayashi, Y. Study on nonthermal-thermal processing boundary in drilling of ceramics using ultrashort pulse laser system with variable parameters over a wide range. Appl. Phys. A 2020, 126, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narazaki, A.; Takada, H.; Yoshitomi, D.; Torizuka, K.; Kobayashi, Y. Ultrafast laser processing of ceramics: Comprehensive survey of laser parameters. J. Laser Appl. 2021, 33, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.M. Simple technique for measurements of pulsed Gaussian-beam spot sizes. Opt. Lett. 1982, 7, 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Yakar, A.; Byer, R.L. Femtosecond laser ablation properties of borosillicate glass. J. Appl. Phys. 2004, 96, 5316–5323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höhm, S.; Rosenfeld, A.; Krüger, J.; Bonse, J. Femtosecond laser-induced periodic surface structures on silica. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 112, 014901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, A.; Rohloff, M.; Höhm, S.; Krüger, J.; Bonse, J. Formation of laser-induced periodic surface structures on fused silica upon multiple parallel polarized double-femtosecond-laser-pulse irradiation sequences. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 258, 9233–9236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navickas, M.; Grigutis, R.; Junka, V.; Tamošauskas, G.; Dubietis, A. Low spatial frequency laser-induced periodic surface structures in fused silica inscribed by widely tunable femtosecond laser pulses. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, R.; Graf, T.; Berger, P.; Onuseit, V.; Wiedenmann, M.; Freitag, C.; Feuer, A. Heat accumulation during pulsed laser materials processing. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 11312–11324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaton, S.M.; Zhang, H.; Herman, P.R.; Yoshino, F.; Shah, L.; Bovatsek, J.; Arai, A.Y. Heat accumulation effects in femtosecond laser-written waveguides with variable repetition rate. Opt. Express 2005, 13, 4708–4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancona, A.; Döring, S.; Jauregui, C.; Röser, F.; Limpert, J.; Nolte, S.; Tünnermann, A. Femtosecond and picosecond laser drilling of metals at high repetition rates and average powers. Opt. Lett. 2009, 34, 3304–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, J.; Nolte, S.; Tünnermann, A. Plasma evolution during metal ablation with ultrashort laser pulses. Opt. Express 2005, 13, 10597–10607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, D.J.; Faas, S.; Gröninger, S.; Bauer, F.; Michalowski, A.; Weber, R.; Graf, T. Shielding effects and re-deposition of material during processing of metals with bursts of ultra-short laser pulses. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 440, 926–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuderi, D.; Albert, O.; Moreau, D.; Pronko, P.P.; Etchepare, J. Interaction of a laser-produced plume with a second time delayed femtosecond pulse. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 86, 071502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höhm, S.; Rosenfeld, A.; Krüger, J.; Bonse, J. Femtosecond diffraction dynamics of laser-induced periodic surface structures on fused silica. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 102, 054102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortmann, D.; Ramme, M.; Gottmann, J. Refractive index modifications using fs-laser double pulses. Opt. Express 2007, 15, 10149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucheyev, S.O.; Demos, S.G. Optical defects produced in fused silica during laser-induced breakdown. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003, 82, 3230–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, L.; Cannas, M.; Radzig, V.; Boscaino, R. Luminescence of the surface nonbridging oxygen hole center in silica: Spectral and decay properties. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 78, 075421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, L.; Cannas, M.; Radzig, V. Luminescence properties of nonbridging oxygen hole centers at the silica surface. J. NonCryst. Solids 2009, 355, 1020–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skuja, L. The origin of the intrinsic 1.9 eV luminescence band in glassy SiO2. J. NonCryst. Solids 1994, 179, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yoshitomi, D.; Takada, H.; Kinugasa, S.; Ogawa, H.; Kobayashi, Y.; Narazaki, A. Intensity Modulation Effects on Ultrafast Laser Ablation Efficiency and Defect Formation in Fused Silica. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 377. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15050377

Yoshitomi D, Takada H, Kinugasa S, Ogawa H, Kobayashi Y, Narazaki A. Intensity Modulation Effects on Ultrafast Laser Ablation Efficiency and Defect Formation in Fused Silica. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(5):377. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15050377

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoshitomi, Dai, Hideyuki Takada, Shinichi Kinugasa, Hiroshi Ogawa, Yohei Kobayashi, and Aiko Narazaki. 2025. "Intensity Modulation Effects on Ultrafast Laser Ablation Efficiency and Defect Formation in Fused Silica" Nanomaterials 15, no. 5: 377. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15050377

APA StyleYoshitomi, D., Takada, H., Kinugasa, S., Ogawa, H., Kobayashi, Y., & Narazaki, A. (2025). Intensity Modulation Effects on Ultrafast Laser Ablation Efficiency and Defect Formation in Fused Silica. Nanomaterials, 15(5), 377. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15050377