Abstract

(1) Background: The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of clostridia strains in a hospital environment in Algeria and to evaluate their antimicrobial susceptibility to antibiotics and biocides. (2) Methods: Five hundred surface samples were collected from surfaces in the intensive care unit and surgical wards in the University Hospital of Tlemcen, Algeria. Bacterial identification was carried out using MALDI-TOF-MS, and then the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of various antimicrobial agents were determined by the E-test method. P. sordellii toxins were searched by enzymatic and PCR assays. Seven products intended for daily disinfection in the hospitals were tested against Clostridium spp. spore collections. (3) Results: Among 100 isolates, 90 P. sordellii were identified, and all strains were devoid of lethal and hemorrhagic toxin genes. Beta-lactam, linezolid, vancomycin, tigecycline, rifampicin, and chloramphenicol all proved effective against isolated strains. Among all strains tested, the spores of P. sordellii exhibited remarkable resistance to the tested biocides compared to other Clostridium species. The (chlorine-based 0.6%, 30 min), (glutaraldehyde solution 2.5%, 30 min), and (hydrogen peroxide/peracetic acid 3%, 15 min) products achieved the required reduction in spores. (4) Conclusions: Our hospital’s current cleaning and disinfection methods need to be optimized to effectively remove spores from caregivers’ hands, equipment, and surfaces.

1. Introduction

Clostridia are composed of a broad spectrum of Gram-positive, spore-forming, and anaerobic bacilli, whose taxonomic classification of genera has been updated. Toxin-producing species can cause mild to life-threatening infections, the most famous being the genus Clostridium (Clostridium botulinum, Clostridium perfringens), the genus Paeniclostridium (Paeniclostridium sordellii), and the genus Clostridioides (Clostridioides difficile) [1]. The clostridial spores display intrinsic resistance to high temperatures and biocides and persist for several months on abiotic surfaces [2]. Their environmental stability and antimicrobial tolerance are significant reasons that this group of bacteria can cause severe problems within healthcare settings [3].

P. sordellii (previously Clostridium sordellii, reclassified in 2016) [4] are ubiquitous in soil, in the gastrointestinal tracts of animals and humans, and in the vaginal microbiota of a modest number of healthy carrier women [5]. As with C. perfringens, P. sordellii is most often associated with fulminant toxic shock syndrome, sepsis, and gas gangrene in postpartum and post-abortive women, in injection drug use, or after trauma or surgery [6]. P. sordellii causes infection in humans sporadically; it is less prevalent than C. perfringens infections, but its lethality rate is relatively higher, close to 70% [7]. The infection can develop from endogenous self-contamination or spore transmission from the environment [8]. Generally, this infection is afebrile, and the clinical manifestations include tachycardia, hypotension, leukemoid reaction, hemoconcentration, edema, and hemorrhage [9].

P. sordellii shares substantial genomic similarity with C. difficile (previously Clostridium difficile, reclassified in 2016) [10], but each has specificities regarding the site of infection and clinical manifestation [11]. Pathogenic isolates produce at least five toxins, two of which are essential for virulence, lethal toxin (TcsL) and hemorrhagic toxin (TcsH). TcsH and TcsL are highly similar in their biological activity and their antigenicity to toxin A (TcdA) and toxin B (TcdA) of C. difficile, respectively, and they can be revealed through cross-reactivity by C. difficile toxin detection [12,13]. These toxins are monoglucosyltransferases, and their main targets are endothelial cells. In addition, numerous studies have reported that non-toxigenic P. sordellii strains are associated with invasive infection cases and had cytotoxicity power towards the mammalian cell in vitro [14,15,16,17].

P. sordellii infections are severe, with a brief period between the onset of symptoms and death. The only viable treatment option is antibiotic therapy [5]. All P. sordellii isolates reported in the literature are highly susceptible to various antibiotics, such as b-lactam, erythromycin, metronidazole, and glycopeptides [5,18]. However, the resistance patterns to clindamycin were different between studies [5].

The presence of spores on surfaces and in the environment in high-risk departments such as intensive care units (ICU) and operating rooms (OR) could be the direct cause of nosocomial infections [19]. The invasive procedures and cutaneous barrier breaking facilitate the penetration and germination of spores in the host and lead to severe complications, such as myonecrosis, gas gangrene, bacteremia, and septicemia [20]. Alkylating agents, oxidizing agents, and chlorine-releasing agents are the most sporicidal disinfectants commonly used in the hospital; despite the success in inactivating spores, routine applications are limited due to their toxic and corrosive properties, and their instability during storage or after preparation influences the quality of disinfection and, more specifically, the elimination of spores [21,22,23].

The goal of the present work was to evaluate the prevalence, and antimicrobial susceptibility, of clostridia strains isolated from environmental surfaces in the University Hospital of Tlemcen (Northwest Algeria). Moreover, molecular investigation of toxin genes was performed on P. sordellii isolates, given the large number of isolates obtained in this study.

2. Results

2.1. Environmental Samples

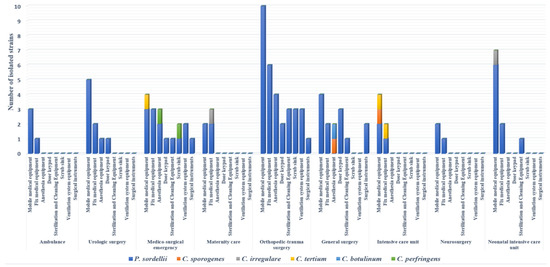

One hundred out of 500 (20%) surface samples collected were positive for clostridia strains after culture. Of these 100 isolates, 90 were identified as P. sordellii, showing a prevalence of 18%; the other Clostridium spp. belonged to seven species, including Clostridium tertium (3/100), C. perfringens (2/100), Clostridium irregulare (2/100), Clostridium sporogenes (2/100), and C. botulinum (1/100) (Figure 1). Eighty percent of strains were isolated from operating room surfaces, with full concentration in three wards (orthopedic–trauma surgery, surgical emergency, general surgery). Regarding the sampling site, a large number of strains (41%) were isolated from mobile medical equipment (stretchers, drip stands, mayo tables, instrumental tables, work tables, trolleys, mobile radiography systems, mobile ultrasound machines, baby incubators). Ten percent of P. sordellii isolates were recovered from cleaning and disinfection equipment and sterile surgical instruments (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of clostridia strains isolated in hospital environment according to sampling sites and wards.

2.2. Antibiotic Susceptibility Test

Overall, all isolated strains were susceptible to beta-lactam, linezolid, vancomycin, tigecycline, rifampicin, and chloramphenicol (Table 1). In addition, one strain of C. perfringens displayed resistance to two antibiotics—metronidazole and clindamycin (MIC 8 and 16 µg/mL, respectively)—and three other strains (two C. tertium, one P. sordellii) were resistant only to clindamycin (MIC 64 µg/mL).

Table 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentration ranges and interpretations of the tested antibiotics to isolated strains from environmental samples.

2.3. Testing of Sporicidal Activity

The disinfectant tests were carried out as part of a suspension test under clean conditions, without the addition of organic loads, and in dirty conditions, with the presence of organic loads (3% bovine serum albumin and 0.3% sheep erythrocytes) added to the test solution to mimic the organic contamination in the hospital environment. The effectiveness of the disinfectants was strongly associated with the product composition, the targeted strain, and the conditions of experimentation. Among the seven products tested), three disinfectants—sodium dichloroisocyanurate (D1), glutaraldehyde (D5), and hydrogen peroxide/peracetic acid (D3)—achieved the required reduction in spores for all tested strains under clean conditions (4 log10) and under dirty conditions (3 log10).

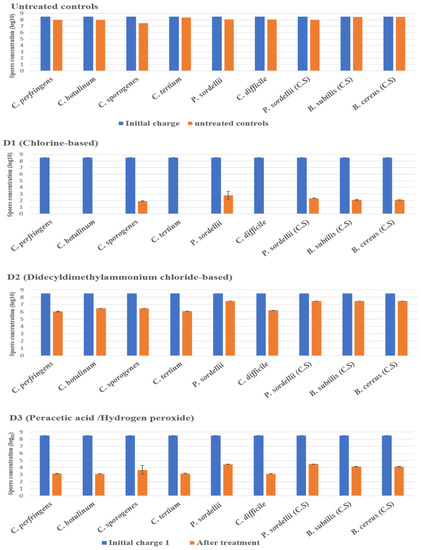

2.3.1. Under Clean Conditions

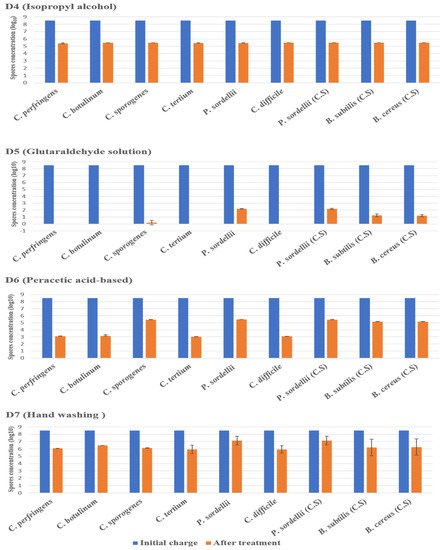

The highest log10 reduction was measured with D1 (chlorine-based) and D5 (glutaraldehyde solution 2.5%) against spores of all strains tested at a contact time of 30 min. D3 (hydrogen peroxide/peracetic acid) also achieved the recommended reduction rate on all spores. D6 (peracetic acid-based) was found effective against spores of C. perfringens, C. botulinum, C. tertium, and C. difficile, giving a reduction of 5.5 log10, at the concentration and the contact time recommended by the manufacturer. Remarkably, this disinfectant showed limited sporicidal activity against P. sordellii, C. sporogenes, and Bacillus spp., with a 3 log10 reduction (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 2.

The effect of D1 (chlorine-based), D2 (didecyldimethylammonium chloride-based), and D3 (hydrogen peroxide/peracetic acid) against spores of tested strains using the European and French standard NF EN 14347, in clean conditions with a standard initial bacterial charge of 3.5 × 108 CFU/mL. Untreated sample was used as a control for experimental conditions. The spore suspensions were suspended in sterile deionized water, for 20 min, and then were filtered and incubated. (C.S) indicates reference strains used as control.

Figure 3.

The effect of D4 (isopropyl alcohol), D5 (glutaraldehyde solution), D6 (peracetic acid-based), and D7 (hand washing) against spores of tested strains using the European and French standard NF EN 14347, in clean conditions, with a standard initial bacterial charge of 3.5 × 108 CFU/Ml. (C.S.) indicates reference strains used as control.

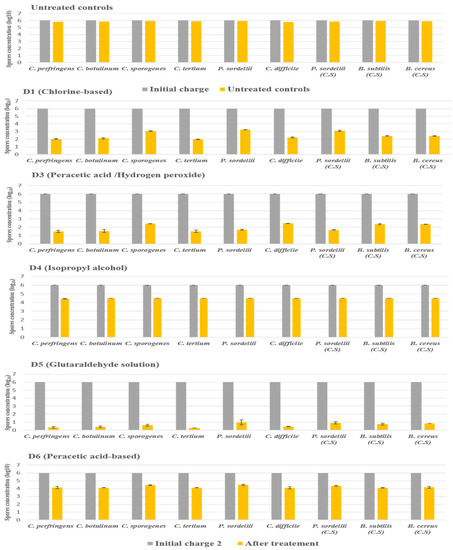

2.3.2. Under Dirty Conditions

The products D2 and D7 were not included in this experiment because they did not show any activity against all species tested under clean conditions.

In dirty conditions, we noted that the activity of most disinfectants slightly decreased, as illustrated in Figure 4. D5 (glutaraldehyde solution 2.5%) kept its effectiveness against the spores of all strains tested, giving a log10 reduction of 5. In contrast, D1 (chlorine-based) lost its activity slightly in the presence of interfering substances, recording a log10 reduction of 2.9 against spores of P. sordellii and C. sporogenes. Indeed, the biocide D3 (hydrogen peroxide/peracetic acid) was always effective on C. perfringens, C. botulinum, C. difficile, and C. tertium, giving a log10 reduction of 4, with a log10 reduction of 3.6 for the four other remaining species.

Figure 4.

The effect of D1 (chlorine-based), D3 (hydrogen peroxide/peracetic acid), D4 (isopropyl alcohol), D5 (glutaraldehyde solution), and D6 (peracetic acid-based) against spores of tested strains using the European and French standard NF EN 13704, in dirty conditions, with a standard initial bacterial charge of 1 × 106 CFU/mL. Untreated samples were used as a control for experimental conditions. The spore was suspended in sterile deionized water with the addition of (3% bovine serum albumin and 0.3% sheep erythrocytes); after 20 min of contact, the spore suspension was filtered and incubated. (C.S.) indicates reference strains used as control.

The D4 disinfectants (isopropyl alcohol) showed a log10 reduction of 1.6, and the D6 disinfectants (peracetic acid-based) showed a log10 reduction of 1.8. They, therefore, did not achieve the required reductions of 3 log10 on all spore species tested after the recommended exposure times under dirty conditions.

2.4. Toxin Enzyme Immunoassays (EIA) and PCR Reaction in P. sordellii Isolates

All P. sordellii isolates were negative for the TcsL and TcsH toxins, as tested using the C. DIFF QUIK CHEK COMPLETE kit. The results of the designed PCR on the extracted genomic DNA of 288 bacterial strains (Table S2), including 239 clostridia strains, with 26 Gram-negative and 23 Gram-positive strains, were 100% specific and only positive on P. sordellii ATCC 9714 and P. sordellii VPI 9048 strains harboring either the tcsL or tcsL and tcsH genes. The detection limit of the tcsL gene in P. sordellii ATCC 9714 and P. sordellii VPI 9048 was 37 and 35 CFU/mL, respectively. In addition, the tcsH gene’s detection limit in P. sordellii VPI 9048 was 40 CFU/mL.

3. Discussion

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the USA has defined spores as the most complicated organism to destroy [24]. In clinical settings, the inanimate environment and healthcare workers’ hands are the most common factors for propagating and transmitting bacterial spores, particularly C. difficile spores [25,26]. Moreover, the presence of other clostridial species in a hospital environment that may be more persistent and virulent is also a reality. In this study, numerous P. sordellii strains were isolated in surgical wards. However, in high-risk departments, the invasive procedures and cutaneous barrier breaking facilitate the penetration and germination of spores in the host. Several authors revealed that clostridia are commonly implicated in deeper tissue infections, gas gangrenous, myonecrosis, and septicemia [20,27]. P. sordellii infections were reported in various pathologies, affecting several anatomical sites, including gynecological infections, peritonitis, endocarditis, pneumonia, arthritis, cellulitis, and myonecrosis [28].

In this study, the contamination of mobile medical equipment such as stretchers, drip stands, mayo tables, instrumental tables, work tables, and trolleys was remarkable; these devices served as potential vectors in spore dissemination in the hospital environment [29]. Ten percent of P. sordellii isolates were recovered from cleaning and disinfection equipment and sterile surgical instruments, probably due to intrinsic spore resistance to biocides and high temperatures [30].

P. sordellii are known to be susceptible to beta-lactam, metronidazole, and vancomycin [5,31], corresponding to the majority of our isolates. Some strains that showed high MICs to clindamycin were reported [31,32,33]. According to numerous studies, enzyme immunoassays and PCR amplification revealed that all P. sordellii isolates were toxin-free [17,34]. The Paloc region of P. sordellii, carrying the lethal toxin tcsL gene, was found mainly within mobile plasmids (pCS1 family) [12]. It is worth noting that they are unstable, and the majority of P. sordellii isolates can be lost quickly upon collection and subculture, thus compromising their detection. In addition, only sporadic research has succeeded in detecting the tcsL gene in a small number of P. sordellii strains isolated from different origins: 2/283 strains from rectal and vaginal swabs [35], 1/14 strains from cadaveric tissue donation [36], and 5/44 strains from clinical and veterinary infections [37]. Invasive diseases are also associated with non-toxinogenic strains according to several clinical reports [14,15,16,17].

The present study is among the few studies designed to assess the sporicidal activity of a range of biocides on clostridia spores. We tried to achieve an experimental situation that best simulated the real conditions of disinfection in the hospital by testing under clean and dirty conditions and for times and concentrations of exposure as recommended by the manufacturer and applied by the hygiene teams. Glutaraldehyde solution at 2.5% was the most effective disinfectant on all spore species at a contact time of 30 min, under both clean and dirty conditions. In concordance with many studies, glutaraldehyde is an effective sporicidal agent, used in most hospitals to disinfect thermosensitive and reusable materials [38,39,40]. However, the application of glutaraldehyde solution to surfaces has not been documented, probably because of its relative respiratory and dermal toxicity [41]. A 0.6% sodium dichloroisocyanurate solution in our study effectively inactivated the clostridial spores.

Several authors have stated that chlorine-based products significantly reduce C. difficile spores [42,43]. Despite their sporicidal effect, these products can quickly interfere with specific materials and/or organic matter, leading to a loss of their activity and the formation of toxic by-products [44]. In addition, they have a corrosive action on various supports, such as stainless and galvanized steel, and are irritating to manipulators [43,45]. For these reasons, their application is often limited to rooms and surfaces close to patients infected with C. difficile [46]. This product is rarely used in the environment of asymptomatic patients, so they are also a potential source of C. difficile contamination [47].

Recent publications [48,49,50] report that the peracetic acid/hydrogen peroxide combination reacts synergistically, having robust sporicidal activity, also observed in the presence of an organic load. In our study, this disinfectant achieved a recommended log10 reduction on various spores of clostridia species, including virulent strains such as C. perfringens, C. difficile and C. botulinum, P. sordellii, and C. sporogenes, and spores of aerobic strains. Peracetic acid oxidates the sulfhydryl and sulfur bonds and denatures enzymes and proteins [51]. Many studies have shown that peracetic acid-based disinfectants inactivate bacterial spores of C. difficile and C. sporogenes in 15 to 30 min [22,52]. The product has proven its effectiveness during our experiment on C. perfringens, C. botulinum, C. tertium, and C. difficile spores, although limited sporicidal activity was observed against P. sordellii and C. sporogenes strains. However, the peracetic acid-based solution decreases their activity in the presence of organic matter and at the time of storage, and it is very corrosive [53,54].

The manufacturer does not report the sporicidal activity of the disinfectants D2 (didecyldimethylammonium chloride) and D4 (isopropyl alcohol). It is already known that alcohol and quaternary ammonium compounds have a narrow spectrum of action and, therefore, a lack of activity against bacterial spores [55,56,57]. We note that disinfectants D2 (didecyldimethylammonium chloride) and D4 (isopropyl alcohol) are extensively used in our hospitals. The widespread use of non-sporicidal disinfectants may encourage bacterial sporulation and participate in their persistence in the environment [25]. In addition, wiping with these products facilitates the spread of bacteria by transferring spores from contaminated sites to clean sites [58]. Healthcare workers’ hands play an essential role in contaminating surfaces and equipment and can transmit bacterial spores between patients.

Many studies have reported that typical hand washing with soap and water does not permanently eliminate C. difficile spores [59,60]; our results confirmed these findings. Recent research suggests new approaches that may be more effective against clostridia spores, such as soaking or wiping hands with electrochemically activated saline solution, generating hypochlorous acid (Vashe) [61], and washing hands with sand- or oil-based products [62].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Samples Collection

Over two years (2016 to 2018), a total of 500 surface sample swabs were collected from nine departments of the University Hospital of Tlemcen (urologic surgery, surgical emergency, gynecologic surgery, orthopedic–trauma surgery, general surgery, neurosurgery, intensive care unit, neonatal intensive care unit, ambulance).

A variety of areas in these high-risk units were swabbed after routine cleaning, including mobile equipment (stretchers, drip stands, mayo tables, instrumental tables, work tables, trolleys, mobile radiography systems, ultrasound machines, baby incubators), fix equipment (passbox, operating tables, storage racks, surgical lighting, computers), anesthesia equipment, door keypads, sterilization and cleaning equipment, scrub sinks, ventilation system equipment, and surgical instruments.

4.2. Culture and Bacterial Identification

The swabs were suspended and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h in BHI (Laboratoire Conda S.A, Torrejón de Ardoz, Spain). Then, the enrichment broth was heated for 10 min at 80 °C to destroy the vegetative cells and activate the spore formation. Then, 100 µL was cultured on Brazier’s agar without added selective agents (D-cycloserine and cefoxitin) and on 7% sheep blood agar, incubated at 37 °C for 48 h/72 h in an anaerobic atmosphere using the GENbag anaer (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). The bacterial identification was performed using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (MS) (Microflex™; Bruker Daltonic, Bremen, Germany) as previously described [63] and confirmed by 16S rRNA sequencing.

4.3. Antibacterial Susceptibility Testing

Antimicrobial drug susceptibility was determined using the E-test method. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) results were interpreted using breakpoints recommended by the Antibiogram Committee of the French Microbiology Society and European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (CA-SFM/EUCAST 2019) https://www.sfm-microbiologie.org/2019/01/07/casfm-eucast-2019/ (accessed on 11 April 2020). The following antibiotics were selected for susceptibility testing: amoxicillin (AC), amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (XL), piperacillin–tazobactam (T/P), imipenem (IP), ertapenem (ETP), clindamycin (CM), metronidazole (MZ), linezolid (LZ), vancomycin (VA), tigecycline (TGC), rifampicin (RI), chloramphenicol (CL) (Ia2, Montpellier, France).

4.4. Spore Preparation and Chosen Biocides

We evaluated the efficacity of biocides for the inactivation of clostridial spores on a collection of nine bacterial strains: seven clostridia species strains and two Bacillus spp. strains. Additional information regarding all strains tested is presented in Table 2. Clostridia spores were prepared as described by Perez et al. (2011) [64] with some modifications. Bacillus spp. spores were prepared according to the ASTM E2197-11 standard [43]. The spores’ concentration was measured by traditional hemacytometer counting. The rate of germinating spores was estimated by counting the number of germinated spores after culture versus the total count of spores.

Table 2.

List of strains tested and their origins, with concentration and percentage of germination of spores in stock solutions.

Seven disinfectant products routinely used in Algerian and French hospital settings were evaluated, including six disinfectants used for the disinfection of surfaces, thermosensitive equipment, instrumentation, and medical devices, and one product used for hand washing among medical staff. Active ingredients and commercial forms are reported in Table 3. The contact times and concentrations were applied according to the manufacturer’s instructions for sporicidal products and as used by the hygiene teams for non-sporicidal products (Table 3). The D2 and D7 products were supplied in ready-to-use liquid form and tested only under clean conditions. The other products were provided in liquid and powder formulations and were prepared by mixing with sterile deionized water.

Table 3.

Product forms, ingredients, use concentrations, and contact times.

4.5. Testing of Sporicidal Activity

The disinfectant tests were carried out as part of a suspension test following the guidelines of the European and French standard NF EN 14347 under clean conditions, without the addition of organic loads, and according to the European and French standard NF EN 13704, in dirty conditions, with the presence of organic loads (3% bovine serum albumin and 0.3% sheep erythrocytes) added to the test solution to mimic organic contamination in the hospital environment [55].

The sporicidal activity was determined in triplicate. For each experiment, a standard initial bacterial charge of 3.5 × 108 CFU/mL and 1 × 106 CFU/mL was used for clean and dirty conditions, respectively, according to the European and French standards mentioned above. After the contact time (Table 3), the suspensions were filtered using membrane filtration (0.22 µm) and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to eliminate any effects of residual antimicrobial components.

After 48 h of incubation, the number of viable spores was determined using the standard colony count method. Log10 reductions were calculated by comparing log10 CFU recovered from disinfectant solutions to untreated controls (spores suspended in deionized water). The sporicidal activity was defined as a reduction of 4 log10 under clean conditions and 3 log10 under dirty conditions.

4.6. Enzyme Immunoassays and PCR for the Detection of P. sordellii Toxins

Enzymatic research on P. sordellii toxins was performed with the C. DIFF QUIK CHEK COMPLETE assay kit (TECHLAB, Blacksburg, VA, USA). The only non-C. difficile micro-organisms detected by the C. DIFF QUIK CHEK COMPLETE® test were P. sordellii strains that produce toxins TcsL and TcsH, which are homologous to toxins TcdA and TcdB, from C. difficile, respectively [65]. Isolated colonies were suspended in the dilution buffer and tested according to the manufacturer’s protocol; P. sordellii VPI 9048 strain was used as a positive control.

For the molecular detection of P. sordellii lethal toxin (TcsL) and hemorrhagic toxin (TcsH), two sets of primers were designed to amplify an internal fragment of 1221 bp size and 1430 bp size, respectively (Table S1). The primers were validated and optimized using DNA extracted from 288 bacterial strains, including 239 clostridia strains, 26 Gram-negative and 23 Gram-positive strains, and two control strains—P. sordellii ATCC 9714 and P. sordellii VPI 9048 (Table S2).

5. Conclusions

P. sordellii is capable of causing severe and often fatal infections. Our study is the first to report a high prevalence of P. sordellii isolates in the hospital environment in Algeria. This situation is probably due to a deficiency in the cleaning of surfaces and instruments, leading to the massive presence of spores in our hospital. This situation needs to be controlled quickly and significantly, since these strains may rapidly acquire the genes of toxins and antibiotic resistance. We observed that the spores of P. sordellii showed higher resistance to all products tested compared to spores of other clostridia species and Bacillus spp. Our results reveal that sodium dichloroisocyanurate (0.6%), glutaraldehyde (2.5%), and hydrogen peroxide/peracetic acid (3%) were the most effective and should be prioritized for routine disinfection in the hospital. Our hospital’s current cleaning and disinfection methods need to be optimized to effectively remove spores from caregivers’ hands, equipment, and surfaces.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/antibiotics11010038/s1, Supplementary Table S1: List of primers designed and validated in this study. Supplementary Table S2: List of the bacterial strains tested for the specificity of the designed PCR assay.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: H.Z., S.M.D. and J.-M.R. methodology: H.Z., A.F., Y.E., S.-A.R., I.P. and S.M.D.; formal analysis: H.Z., I.P., S.A.B. and J.-M.R.; writing—original draft preparation: H.Z.; writing—review and editing: H.Z., I.P., A.F., S.A.B., Y.E., S.-A.R., S.M.D. and J.-M.R.; supervision: J.-M.R. and S.M.D.; funding acquisition: J.-M.R. and S.M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Algerian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research and by the French Government under the “Investissements d’avenir” (reference: Méditerranée Infection 10-IAHU-03).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank Linda Hadjadj for the technical assistance. We are very grateful to the personnel of Tlemcen University Hospital for helping with the sample collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Orrell, K.E.; Melnyk, R.A. Large Clostridial Toxins: Mechanisms and Roles in Disease. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2021, 85, e00064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoff, M.R.; Bouvet, P. Genetic characteristics of toxigenic Clostridia and toxin gene evolution. Toxicon 2013, 75, 63–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, S.; Dolan, A.; Cahill, O.; Daniels, S.; Humphreys, H. Microbial monitoring of the hospital environment: Why and how? J. Hosp. Infect. 2012, 82, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyothsna, T.S.S.; Tushar, L.; Sasikala, C.; Ramana, C.V. Paraclostridium benzoelyticum gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from marine sediment and reclassification of Clostridium bifermentans as Paraclostridium bifermentans comb. nov. Proposal of a new genus Paeniclostridium gen. nov. to accommodate Clostridium sordellii and Clostridium ghonii. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 1268–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidor, C.; Awad, M.; Lyras, D. Antibiotic resistance, virulence factors and genetics of Clostridium sordellii. Res. Microbiol. 2015, 166, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.L.; Bhatnagar, J.; Reagan, S.; Zane, S.B.; D’Angeli, M.A.; Fischer, M.; Killgore, G.; Kwan-Gett, T.S.; Blossom, D.B.; Shieh, W.J.; et al. Toxic shock associated with Clostridium sordellii and Clostridium perfringens after medical and spontaneous abortion. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 110, 1027–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkbuli, A.; Diaz, B.; Ehrhardt, J.D.; Hai, S.; Kaufman, S.; McKenney, M.; Boneva, D. Survival from Clostridium toxic shock syndrome: Case report and review of the literature. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2018, 50, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabi, R.; Turnbull, L.; Whitchurch, C.B.; Awad, M.; Lyras, D. Structural Characterization of Clostridium sordellii Spores of Diverse Human, Animal, and Environmental Origin and Comparison to Clostridium difficile Spores. mSphere 2017, 2, e00343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldape, M.J.; Bryant, A.E.; Stevens, D.L. Clostridium sordellii Infection: Epidemiology, Clinical Findings, and Current Perspectives on Diagnosis and Treatment. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 43, 1436–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, P.A.; Citron, D.M.; Tyrrell, K.L.; Finegold, S.M. Reclassification of Clostridium difficile as Clostridioides difficile (Hall and O’Toole 1935) Prévot 1938. Anaerobe 2016, 40, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaria, J.; Suzuki, H.; Ptak, C.P.; Chen, J.W.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, X.K.; Chang, Y.F. Comparative genomic and phenomic analysis of Clostridium difficile and Clostridium sordellii, two related pathogens with differing host tissue preference. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, A.R.S.; Girinathan, B.P.; Zapotocny, R.; Govind, R. Identification and characterization of Clostridium sordellii toxin gene regulator. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 4246–4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilbault, C.; Labbé, A.C.; Poirier, L.; Busque, L.; Béliveau, C.; Laverdière, M. Development and evaluation of a PCR method for detection of the Clostridium difficile toxin B gene in stool specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 2288–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Hao, Y.; Senn, T.; Opp, J.S.; Young, V.B.; Thiele, T.; Srinivas, G.; Huang, S.K.; Aronoff, D.M. Lethal toxin is a critical determinant of rapid mortality in rodent models of Clostridium sordellii endometritis. Anaerobe 2010, 16, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulla, A.; Yee, L. The clinical spectrum of Clostridium sordellii bacteraemia: Two case reports and a review of the literature. J. Clin. Pathol. 2000, 53, 709–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valour, F.; Boisset, S.; Lebras, L.; Martha, B.; Boibieux, A.; Perpoint, T.; Chidiac, C.; Ferry, T.; Peyramond, D. Clostridium sordellii brain abscess diagnosed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 3443–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Walk, S.T.; Jain, R.; Trivedi, I.; Grossman, S.; Newton, D.W.; Thelen, T.; Hao, Y.; Songer, J.G.; Carter, G.P.; Lyras, D.; et al. Non-toxigenic Clostridium sordellii: Clinical and microbiological features of a case of cholangitis-associated bacteremia. Anaerobe 2011, 17, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Tamura, Y.; Takahashi, T. Tetracycline-resistance genes of Clostridium perfringens, Clostridium septicum and Clostridium sordellii isolated from cattle affected with malignant edema. Vet. Microbiol. 2001, 83, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleyman, G.; Alangaden, G.; Bardossy, A.C. The Role of Environmental Contamination in the Transmission of Nosocomial Pathogens and Healthcare-Associated Infections. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2018, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Itoh, N.; Sugiyama, T.; Kurai, H. Clinical features of Clostridium bacteremia in cancer patients: A case series review. J. Infect. Chemother. 2019, 26, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leggett, M.J.; Setlow, P.; Sattar, S.A.; Maillard, J.Y. Assessing the activity of microbicides against bacterial spores: Knowledge and pitfalls. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 120, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.K.; Pratt, M.D.; Lowe, C.W.; Cohen, M.N.; Satterfield, B.A.; Schaalje, B.; O’Neill, K.L.; Robison, R.A. The differential effects of heat-shocking on the viability of spores from Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus subtilis, and Clostridium sporogenes after treatment with peracetic acid- and glutaraldehyde-based disinfectants. MicrobiologyOpen 2015, 4, 764–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, J.P.; Adrion, A.C. Review of Decontamination Techniques for the Inactivation of Bacillus anthracis and Other Spore-Forming Bacteria Associated with Building or Outdoor Materials. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 4045–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, P.N. Testing standards for sporicides. J. Hosp. Infect. 2011, 77, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraise, A. Currently available sporicides for use in healthcare, and their limitations. J. Hosp. Infect. 2011, 77, 210–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasahara, T.; Ae, R.; Watanabe, M.; Kimura, Y.; Yonekawa, C.; Hayashi, S.; Morisawa, Y. Contamination of healthcare workers’ hands with bacterial spores. J. Infect. Chemother. 2016, 22, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibnoulkhatib, A.; Lacroix, J.; Moine, A.; Archambaud, M.; Bonnet, E.; Laffosse, J.M. Post-traumatic bone and/or joint limb infections due to Clostridium spp. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2012, 98, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, J.; Deleon-Carnes, M.; Kellar, K.L.; Bandyopadhyay, K.; Antoniadou, Z.A.; Shieh, W.J.; Paddock, C.D.; Zaki, S.R. Rapid, simultaneous detection of Clostridium sordellii and Clostridium perfringens in archived tissues by a novel PCR-based microsphere assay: Diagnostic implications for pregnancy-associated toxic shock syndrome cases. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 2012, 972845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jencson, A.L.; Cadnum, J.L.; Wilson, B.M.; Donskey, C.J. Spores on wheels: Wheelchairs are a potential vector for dissemination ofpathogens in healthcare facilities. Am. J. Infect. Control 2019, 47, 459–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozma-Sipos, Z.; Szigeti, J.; Ásványi, B.; Varga, L. Heat resistance of Clostridium sordellii spores. Anaerobe 2010, 16, 226–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Roberts, S.A.; Shore, K.P.; Paviour, S.D.; Holland, D.; Morris, A.J. Antimicrobial susceptibility of anaerobic bacteria in New Zealand: 1999–2003. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 57, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazier, J.S.; Levett, P.N.; Stannard, A.J.; Phillips, K.D.; Willis, A.T. Antibiotic susceptibility of clinical isolates of clostridia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1985, 15, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand-Austin, A.; Rawte, P.; Toye, B.; Jamieson, F.B.; Farrell, D.J.; Patel, S.N. Antimicrobial susceptibility of clinical isolates of anaerobic bacteria in Ontario, 2010–2011. Anaerobe 2014, 28, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouvet, P.; Sautereau, J.; Le Coustumier, A.; Mory, F.; Bouchier, C.; Popoff, M.-R. Foot Infection by Clostridium sordellii: Case Report and Review of 15 Cases in France. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 1423–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, E.; Winikoff, B.; Charles, D.; Agnew, K.; Prentice, J.L.; Limbago, B.M.; Platais, I.; Louie, K.; Jones, H.E.; Shannon, C. Vaginal and Rectal Clostridium sordellii and Clostridium perfringens Presence Among Women in the United States. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 127, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voth, D.E.; Martinez, O.V.; Ballard, J.D. Variations in lethal toxin and cholesterol-dependent cytolysin production correspond to differences in cytotoxicity among strains of Clostridium sordellii. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2006, 259, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couchman, E.C.; Browne, H.P.; Dunn, M.; Lawley, T.D.; Songer, J.G.; Hall, V.; Petrovska, L.; Vidor, C.; Awad, M.; Lyras, D.; et al. Clostridium sordellii genome analysis reveals plasmid localized toxin genes encoded within pathogenicity loci. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyas, A.; Das, B.C. The activity of glutaraldehyde against Clostridium difficile. J. Hosp. Infect. 1985, 6, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, D.W.; Seal, L.A. Evaluation of a novel, rapid-acting, sterilizing solution at room temperature. Am. J. Infect. Control 2000, 28, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wullt, M.; Odenholt, I.; Walder, M. Activity of Three Disinfectants and Acidified Nitrite Against Clostridium difficile Spores. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2003, 24, 765–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, B.; Jordan, S.L. Toxicological, medical and industrial hygiene aspects of glutaraldehyde with particular reference to its biocidal use in cold sterilization procedures. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2001, 21, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, J.; Springthorpe, V.S.; Sattar, S.A. Activity of selected oxidizing microbicides against the spores of Clostridium difficile: Relevance to environmental control. Am. J. Infect. Control 2005, 33, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwamahoro, M.C.; Massicotte, R.; Hurtubise, Y.; Gagné-Bourque, F.; Mafu, A.A.; Yahia, L. Evaluating the Sporicidal Activity of Disinfectants against Clostridium difficile and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Spores by Using the Improved Methods Based on ASTM E2197-11. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, T.G.; Barbosa, T.F.; Teixeira, F.L.; de Ferreira, E.O.; Duarte, R.S.; Domingues, R.M.C.P.; De Paula, G.R. Effect of hospital disinfectants on spores of clinical brazilian Clostridium difficile strains. Anaerobe 2013, 22, 121–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massicotte, R.; Ginestet, P.; Yahia, L.; Pichette, G.; Mafu, A.A. Comparative study from a chemical perspective of two- and three-step disinfection techniques to control Clostridium difficile spores. Int. J. Infect. Control 2011, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbut, F.; Menuet, D.; Verachten, M.; Girou, E. Comparison of the Efficacy of a Hydrogen Peroxide Dry-Mist Disinfection System and Sodium Hypochlorite Solution for Eradication of Clostridium difficile Spores. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2009, 30, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggs, M.M.; Sethi, A.K.; Zabarsky, T.F.; Eckstein, E.C.; Jump, R.L.P.; Donskey, C.J. Asymptomatic carriers are a potential source for transmission of epidemic and nonepidemic Clostridium difficile strains among long-term care facility residents. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 45, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, A.; Mana, T.S.C.; Cadnum, J.L.; Jencson, A.C.; Sitzlar, B.; Fertelli, D.; Hurless, K.; Sunkesula, V.C.K.; Donskey, C.J.; Kundrapu, S. Evaluation of a Sporicidal Peracetic Acid/Hydrogen Peroxide—Based Daily Disinfectant Cleaner. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2014, 35, 1414–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Block, C. The effect of Perasafe® and sodium dichloroisocyanurate (NaDCC) against spores of Clostridium difficile and Bacillus atrophaeus on stainless steel and polyvinyl chloride surfaces. J. Hosp. Infect. 2004, 57, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, L.F.; Valiente, E.; Donahue, E.H.; Birchenough, G.; Wren, B.W. Hypervirulent Clostridium difficile pcr-ribotypes exhibit resistance to widely used disinfectants. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.; Malyshev, D.; Dahlberg, T.; Wiklund, K.; Andersson, P.O.; Henriksson, S. Mode of action of disinfection chemicals on the bacterial spore structure and their raman spectra. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 3146–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterspoor, S.; Farrell, J. An evaluation of buffered peracetic acid as an alternative to chlorine and hydrogen peroxide based disinfectants. Infect. Dis. Health 2019, 24, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, S.A.D.S.; Paula, O.F.P.D.; Silva, C.R.G.; Leão, M.V.P.; Santos, S.S.F.D. Stability of antimicrobial activity of peracetic acid solutions used in the final disinfection process. Braz. Oral Res. 2015, 29, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Huang, C.-H. Reactivity of Peracetic Acid with Organic Compounds: A Critical Review. ACS ES&T Water 2021, 1, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenters, N.; Huijskens, E.G.W.; de Wit, S.C.J.; Sanders, I.G.J.M.; van Rosmalen, J.; Kuijper, E.J.; Voss, A. Effectiveness of various cleaning and disinfectant products on Clostridium difficile spores of PCR ribotypes 010, 014 and 027. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2017, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speight, S.; Moy, A.; Macken, S.; Chitnis, R.; Hoffman, P.N.; Davies, A.; Bennett, A.; Walker, J.T. Evaluation of the sporicidal activity of different chemical disinfectants used in hospitals against Clostridium difficile. J. Hosp. Infect. 2011, 79, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesgate, R.; Rauwel, G.; Criquelion, J.; Maillard, J.Y. Impact of standard test protocols on sporicidal efficacy. J. Hosp. Infect. 2016, 93, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng Wong, Y.K.; Alhmidi, H.; Mana, T.S.C.; Cadnum, J.L.; Jencson, A.L.; Donskey, C.J. Impact of routine use of a spray formulation of bleach on Clostridium difficile spore contamination in non-C difficile infection rooms. Am. J. Infect. Control 2019, 47, 843–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundrapu, S.; Sunkesula, V.; Jury, I.; Deshpande, A.; Donskey, C.J. A Randomized Trial of Soap and Water Hand Wash Versus Alcohol Hand Rub for Removal of Clostridium difficile Spores from Hands of Patients. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2014, 35, 204–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, A.K.; Zellmer, C.; Tischendorf, J.; Duster, M.; Valentine, S.; Wright, M.O.; Safdar, N. On the hands of patients with Clostridium difficile: A study of spore prevalence and the effect of hand hygiene on C difficile removal. Am. J. Infect. Control 2017, 45, 1154–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerandzic, M.M.; Rackaityte, E.; Jury, L.A.; Eckart, K.; Donskey, C.J. Novel Strategies for Enhanced Removal of Persistent Bacillus anthracis Surrogates and Clostridium difficile Spores from Skin. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaacson, D.; Haller, B.; Leslie, H.; Roemer, M.; Winston, L. Novel handwashes are superior to soap and water in removal of Clostridium difficile spores from the hands. Am. J. Infect. Control 2015, 43, 530–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiary, F.; Sayevand, H.R.; Remely, M.; Hippe, B.; Indra, A.; Hosseini, H.; Haslberger, A.G. Identification of Clostridium spp. derived from a sheep and cattle slaughterhouse by matrix-assisted laser desorption and ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) and 16S rDNA sequencing. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 3232–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, J.; Springthorpe, V.S.; Sattar, S.A. Clospore: A liquid medium for producing high titers of semi-purified spores of Clostridium difficile. J. AOAC Int. 2011, 94, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, I.Y.; Song, D.J.; Huh, H.J.; Lee, N.Y. Simultaneous detection of Clostridioides difficile glutamate dehydrogenase and toxin A/B: Comparison of the C. DIFF QUIK CHEK COMPLETE and RIDASCREEN Assays. Ann. Lab. Med. 2019, 39, 214–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).