Use of Antimicrobials for Bloodstream Infections in the Intensive Care Unit, a Clinically Oriented Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- According to the origin of the infection, either community-acquired (CA-BSI), hospital-acquired (HA-BSI) or intensive care unit (ICU)–acquired (ICU-BSI).

- Either secondary to a source of infection or primary, when there is no identified source [2].

- Complicated or uncomplicated, which was recently defined as a having definite source (among urinary, catheter, intra-abdominal, pneumonia, skin or soft tissues), and effective source control, in a non-immunocompromised patient, and with clinical improvement after 72 h of antimicrobial therapy (at least defervescence and haemodynamic stability) [3].

- By clinical severity, which is the absence or presence of organ failures and the need for organ supportive therapy in the ICU.

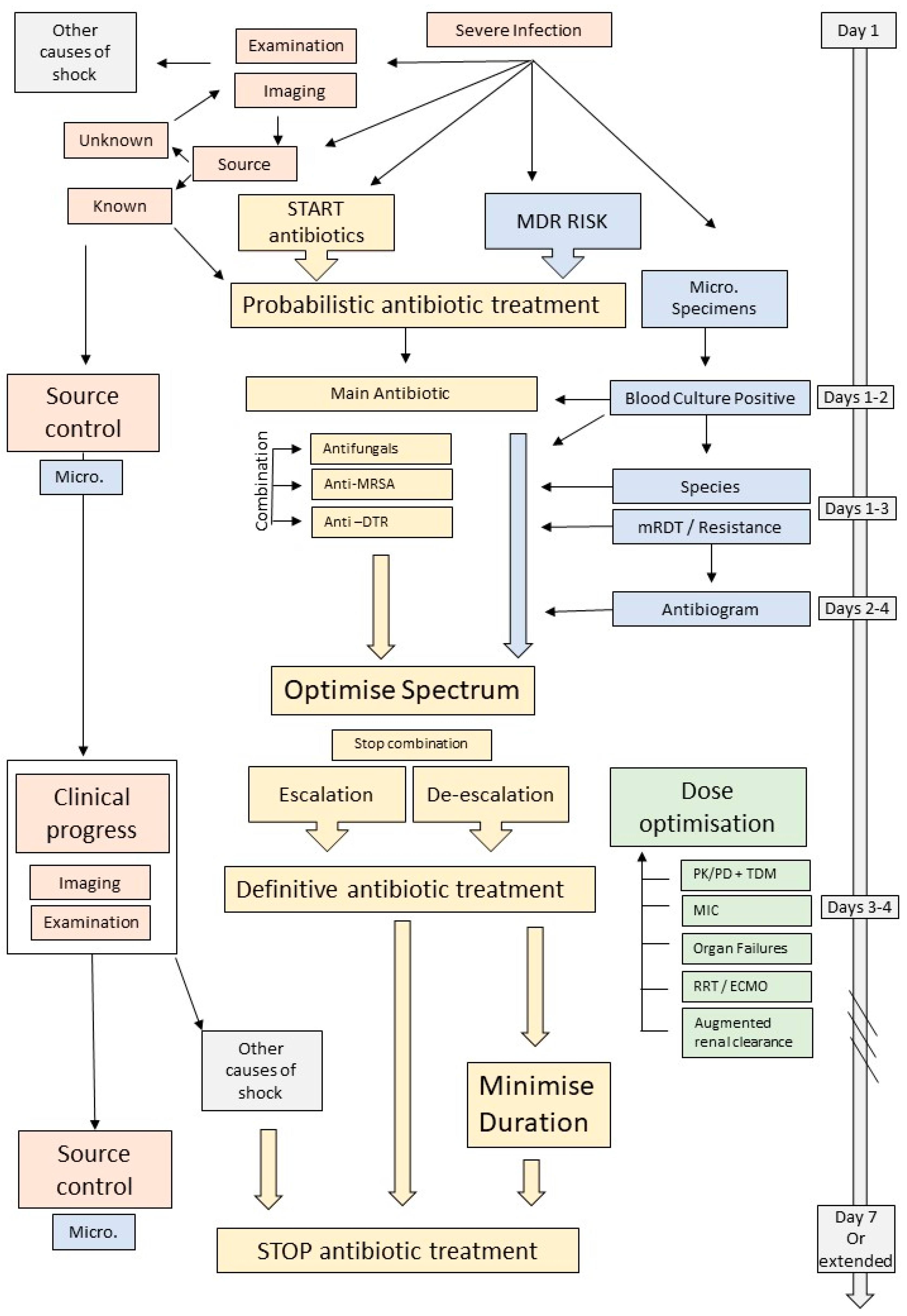

2. Antimicrobial Therapy

2.1. Empirical Antimicrobial Therapy

2.1.1. The Importance of Getting It Right from the Start

2.1.2. Broad-Spectrum Antibiotics and Combination Therapy?

2.1.3. The Importance of Sending Blood Cultures before Starting Antimicrobials

2.1.4. The Advent of Molecular Rapid Diagnostic Testing

2.2. What to Do with Culture Results

2.2.1. Specific Pathogens

Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacterales

Inducible AmpC-Producing Enterobacterales

Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales

Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii

Staphylococcus aureus and MRSA

3. Do Not Forget Source Control

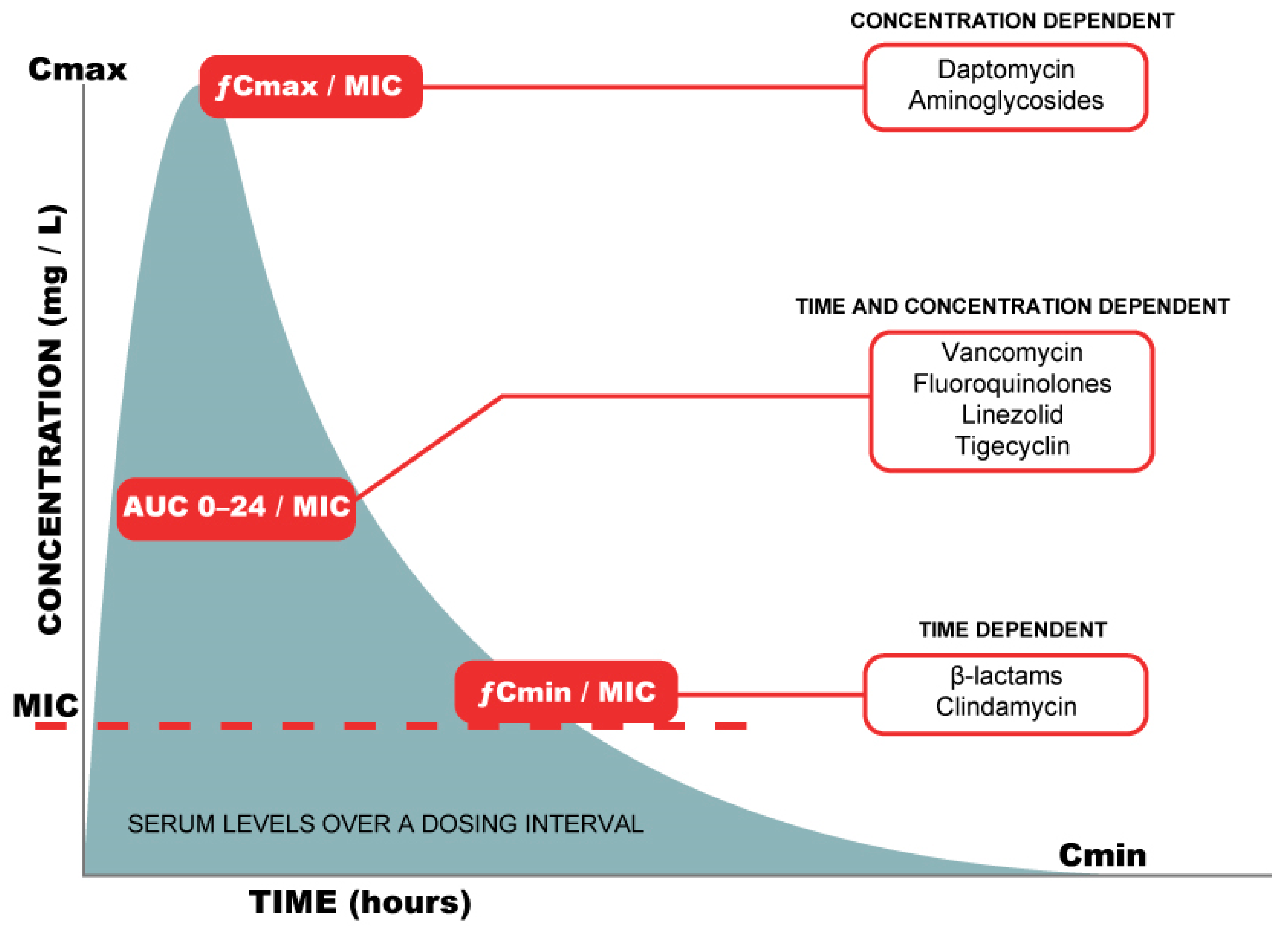

4. Optimisation and Dosing Strategies

5. When and How to Stop Therapy

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Laupland, K.B.; Leal, J.R. Defining microbial invasion of the bloodstream: A structured review. Infect. Dis. 2020, 52, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timsit, J.F.; Ruppe, E.; Barbier, F.; Tabah, A.; Bassetti, M. Bloodstream infections in critically ill patients: An expert statement. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heil, E.L.; Bork, J.T.; Abbo, L.M.; Barlam, T.F.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Davis, A.; Ha, D.R.; Jenkins, T.C.; Kaye, K.S.; Lewis, J.S., 2nd; et al. Optimizing the Management of Uncomplicated Gram-Negative Bloodstream Infections: Consensus Guidance Using a Modified Delphi Process. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, ofab434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angus, D.C.; Opal, S. Immunosuppression and Secondary Infection in Sepsis: Part, Not All, of the Story. JAMA 2016, 315, 1457–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Vught, L.A.; Klein Klouwenberg, P.M.; Spitoni, C.; Scicluna, B.P.; Wiewel, M.A.; Horn, J.; Schultz, M.J.; Nurnberg, P.; Bonten, M.J.; Cremer, O.L.; et al. Incidence, Risk Factors, and Attributable Mortality of Secondary Infections in the Intensive Care Unit After Admission for Sepsis. JAMA 2016, 315, 1469–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tabah, A.; Koulenti, D.; Laupland, K.; Misset, B.; Valles, J.; Bruzzi de Carvalho, F.; Paiva, J.A.; Cakar, N.; Ma, X.; Eggimann, P.; et al. Characteristics and determinants of outcome of hospital-acquired bloodstream infections in intensive care units: The EUROBACT International Cohort Study. Intensive Care Med. 2012, 38, 1930–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garrouste-Orgeas, M.; Timsit, J.F.; Tafflet, M.; Misset, B.; Zahar, J.R.; Soufir, L.; Lazard, T.; Jamali, S.; Mourvillier, B.; Cohen, Y.; et al. Excess risk of death from intensive care unit-acquired nosocomial bloodstream infections: A reappraisal. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 42, 1118–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adrie, C.; Garrouste-Orgeas, M.; Ibn Essaied, W.; Schwebel, C.; Darmon, M.; Mourvillier, B.; Ruckly, S.; Dumenil, A.S.; Kallel, H.; Argaud, L.; et al. Attributable mortality of ICU-acquired bloodstream infections: Impact of the source, causative micro-organism, resistance profile and antimicrobial therapy. J. Infect. 2017, 74, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L.; Rhodes, A.; Alhazzani, W.; Antonelli, M.; Coopersmith, C.M.; French, C.; Machado, F.R.; McIntyre, L.; Ostermann, M.; Prescott, H.C.; et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 1181–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Roberts, D.; Wood, K.E.; Light, B.; Parrillo, J.E.; Sharma, S.; Suppes, R.; Feinstein, D.; Zanotti, S.; Taiberg, L.; et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 34, 1589–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloos, F.; Ruddel, H.; Thomas-Ruddel, D.; Schwarzkopf, D.; Pausch, C.; Harbarth, S.; Schreiber, T.; Grundling, M.; Marshall, J.; Simon, P.; et al. Effect of a multifaceted educational intervention for anti-infectious measures on sepsis mortality: A cluster randomized trial. Intensive Care Med. 2017, 43, 1602–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, M. Antibiotics for Sepsis: Does Each Hour Really Count, or Is It Incestuous Amplification? Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 196, 800–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hranjec, T.; Rosenberger, L.H.; Swenson, B.; Metzger, R.; Flohr, T.R.; Politano, A.D.; Riccio, L.M.; Popovsky, K.A.; Sawyer, R.G. Aggressive versus conservative initiation of antimicrobial treatment in critically ill surgical patients with suspected intensive-care-unit-acquired infection: A quasi-experimental, before and after observational cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2012, 12, 774–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arulkumaran, N.; Routledge, M.; Schlebusch, S.; Lipman, J.; Conway Morris, A. Antimicrobial-associated harm in critical care: A narrative review. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFadden, D.R.; Coburn, B.; Shah, N.; Robicsek, A.; Savage, R.; Elligsen, M.; Daneman, N. Utility of prior cultures in predicting antibiotic resistance of bloodstream infections due to Gram-negative pathogens: A multicentre observational cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018, 24, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Depuydt, P.; Benoit, D.; Vogelaers, D.; Decruyenaere, J.; Vandijck, D.; Claeys, G.; Verschraegen, G.; Blot, S. Systematic surveillance cultures as a tool to predict involvement of multidrug antibiotic resistant bacteria in ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 2008, 34, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhazzani, W.; Moller, M.H.; Arabi, Y.M.; Loeb, M.; Gong, M.N.; Fan, E.; Oczkowski, S.; Levy, M.M.; Derde, L.; Dzierba, A.; et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: Guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 854–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tabah, A.; Bassetti, M.; Kollef, M.H.; Zahar, J.R.; Paiva, J.A.; Timsit, J.F.; Roberts, J.A.; Schouten, J.; Giamarellou, H.; Rello, J.; et al. Antimicrobial de-escalation in critically ill patients: A position statement from a task force of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) and European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) Critically Ill Patients Study Group (ESGCIP). Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 245–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheer, C.S.; Fuchs, C.; Grundling, M.; Vollmer, M.; Bast, J.; Bohnert, J.A.; Zimmermann, K.; Hahnenkamp, K.; Rehberg, S.; Kuhn, S.O. Impact of antibiotic administration on blood culture positivity at the beginning of sepsis: A prospective clinical cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dargere, S.; Cormier, H.; Verdon, R. Contaminants in blood cultures: Importance, implications, interpretation and prevention. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018, 24, 964–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Noster, J.; Thelen, P.; Hamprecht, A. Detection of Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacterales-From ESBLs to Carbapenemases. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabah, A.; Buetti, N.; Barbier, F.; Timsit, J.F. Current opinion in management of septic shock due to Gram-negative bacteria. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 34, 718–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacobbe, D.R.; Giani, T.; Bassetti, M.; Marchese, A.; Viscoli, C.; Rossolini, G.M. Rapid microbiological tests for bloodstream infections due to multidrug resistant Gram-negative bacteria: Therapeutic implications. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pancholi, P.; Carroll, K.C.; Buchan, B.W.; Chan, R.C.; Dhiman, N.; Ford, B.; Granato, P.A.; Harrington, A.T.; Hernandez, D.R.; Humphries, R.M.; et al. Multicenter Evaluation of the Accelerate PhenoTest BC Kit for Rapid Identification and Phenotypic Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Using Morphokinetic Cellular Analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 56, e01317–e01329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meier, M.; Hamprecht, A. Systematic Comparison of Four Methods for Detection of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacterales Directly from Blood Cultures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019, 57, e00709–e00719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nordmann, P.; Sadek, M.; Demord, A.; Poirel, L. NitroSpeed-Carba NP Test for Rapid Detection and Differentiation between Different Classes of Carbapenemases in Enterobacterales. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, e00920–e00932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabah, A.; Cotta, M.O.; Garnacho-Montero, J.; Schouten, J.; Roberts, J.A.; Lipman, J.; Tacey, M.; Timsit, J.F.; Leone, M.; Zahar, J.R.; et al. A Systematic Review of the Definitions, Determinants, and Clinical Outcomes of Antimicrobial De-escalation in the Intensive Care Unit. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sjovall, F.; Perner, A.; Hylander Moller, M. Empirical mono- versus combination antibiotic therapy in adult intensive care patients with severe sepsis–A systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. J. Infect. 2017, 74, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamma, P.D.; Aitken, S.L.; Bonomo, R.A.; Mathers, A.J.; van Duin, D.; Clancy, C.J. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidance on the Treatment of Extended-Spectrum beta-lactamase Producing Enterobacterales (ESBL-E), Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales (CRE), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa with Difficult-to-Treat Resistance (DTR-P. aeruginosa). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.; Carrara, E.; Retamar, P.; Tangden, T.; Bitterman, R.; Bonomo, R.A.; de Waele, J.; Daikos, G.L.; Akova, M.; Harbarth, S.; et al. European Society of clinical microbiology and infectious diseases (ESCMID) guidelines for the treatment of infections caused by Multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli (endorsed by ESICM -European Society of intensive care Medicine). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilmis, B.; Jullien, V.; Tabah, A.; Zahar, J.R.; Brun-Buisson, C. Piperacillin-tazobactam as alternative to carbapenems for ICU patients. Ann. Intensive Care 2017, 7, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Harris, P.N.A.; Tambyah, P.A.; Lye, D.C.; Mo, Y.; Lee, T.H.; Yilmaz, M.; Alenazi, T.H.; Arabi, Y.; Falcone, M.; Bassetti, M.; et al. Effect of Piperacillin-Tazobactam vs Meropenem on 30-Day Mortality for Patients with E. coli or Klebsiella pneumoniae Bloodstream Infection and Ceftriaxone Resistance: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018, 320, 984–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tamma, P.D.; Doi, Y.; Bonomo, R.A.; Johnson, J.K.; Simner, P.J.; Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group. A Primer on AmpC beta-Lactamases: Necessary Knowledge for an Increasingly Multidrug-resistant World. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69, 1446–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fung-Tomc, J.C.; Gradelski, E.; Huczko, E.; Dougherty, T.J.; Kessler, R.E.; Bonner, D.P. Differences in the resistant variants of Enterobacter cloacae selected by extended-spectrum cephalosporins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1996, 40, 1289–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheng, L.; Nelson, B.C.; Mehta, M.; Seval, N.; Park, S.; Giddins, M.J.; Shi, Q.; Whittier, S.; Gomez-Simmonds, A.; Uhlemann, A.C. Piperacillin-Tazobactam versus Other Antibacterial Agents for Treatment of Bloodstream Infections Due to AmpC beta-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e00276-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tamma, P.D.; Aitken, S.L.; Bonomo, R.A.; Mathers, A.J.; van Duin, D.; Clancy, C.J. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidance on the Treatment of AmpC beta-lactamase-Producing Enterobacterales, Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, ciab1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.G.; Paterson, D.L.; Young, B.; Lye, D.C.; Davis, J.S.; Schneider, K.; Yilmaz, M.; Dinleyici, R.; Runnegar, N.; Henderson, A.; et al. Meropenem Versus Piperacillin-Tazobactam for Definitive Treatment of Bloodstream Infections Caused by AmpC beta-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacter spp., Citrobacter freundii, Morganella morganii, Providencia spp., or Serratia marcescens: A Pilot Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial (MERINO-2). Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, ofab387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales (CRE): CRE Technical Information. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hai/organisms/cre/technical-info.html#Definition (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Van Duin, D.; Arias, C.A.; Komarow, L.; Chen, L.; Hanson, B.M.; Weston, G.; Cober, E.; Garner, O.B.; Jacob, J.T.; Satlin, M.J.; et al. Molecular and clinical epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales in the USA (CRACKLE-2): A prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Duin, D.; Lok, J.J.; Earley, M.; Cober, E.; Richter, S.S.; Perez, F.; Salata, R.A.; Kalayjian, R.C.; Watkins, R.R.; Doi, Y.; et al. Colistin Versus Ceftazidime-Avibactam in the Treatment of Infections Due to Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 66, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tumbarello, M.; Raffaelli, F.; Giannella, M.; Mantengoli, E.; Mularoni, A.; Venditti, M.; De Rosa, F.G.; Sarmati, L.; Bassetti, M.; Brindicci, G.; et al. Ceftazidime-Avibactam Use for Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase-Producing K. pneumoniae Infections: A Retrospective Observational Multicenter Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 1664–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, R.K.; Nguyen, M.H.; Chen, L.; Press, E.G.; Potoski, B.A.; Marini, R.V.; Doi, Y.; Kreiswirth, B.N.; Clancy, C.J. Ceftazidime-avibactam is superior to other treatment regimens against carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e00817–e00883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wunderink, R.G.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Rahav, G.; Mathers, A.J.; Bassetti, M.; Vazquez, J.; Cornely, O.A.; Solomkin, J.; Bhowmick, T.; Bishara, J.; et al. Effect and Safety of Meropenem-Vaborbactam versus Best-Available Therapy in Patients with Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Infections: The TANGO II Randomized Clinical Trial. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2018, 7, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bassetti, M.; Echols, R.; Matsunaga, Y.; Ariyasu, M.; Doi, Y.; Ferrer, R.; Lodise, T.P.; Naas, T.; Niki, Y.; Paterson, D.L.; et al. Efficacy and safety of cefiderocol or best available therapy for the treatment of serious infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (CREDIBLE-CR): A randomised, open-label, multicentre, pathogen-focused, descriptive, phase 3 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, R.K.; Doi, Y. Aztreonam Combination Therapy: An Answer to Metallo-beta-Lactamase-Producing Gram-Negative Bacteria? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 1099–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcone, M.; Daikos, G.L.; Tiseo, G.; Bassoulis, D.; Giordano, C.; Galfo, V.; Leonildi, A.; Tagliaferri, E.; Barnini, S.; Sani, S.; et al. Efficacy of Ceftazidime-avibactam Plus Aztreonam in Patients with Bloodstream Infections Caused by Metallo-β-lactamase-Producing Enterobacterales. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 1871–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timsit, J.-F.; Wicky, P.-H.; de Montmollin, E. Treatment of Severe Infections Due to Metallo-Betalactamases Enterobacterales in Critically Ill Patients. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Gutierrez, B.; Salamanca, E.; de Cueto, M.; Hsueh, P.R.; Viale, P.; Pano-Pardo, J.R.; Venditti, M.; Tumbarello, M.; Daikos, G.; Canton, R.; et al. Effect of appropriate combination therapy on mortality of patients with bloodstream infections due to carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (INCREMENT): A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperaki, E.T.; Tzouvelekis, L.S.; Miriagou, V.; Daikos, G.L. Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: In pursuit of an effective treatment. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sader, H.S.; Castanheira, M.; Flamm, R.K.; Mendes, R.E.; Farrell, D.J.; Jones, R.N. Ceftazidime/avibactam tested against Gram-negative bacteria from intensive care unit (ICU) and non-ICU patients, including those with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2015, 46, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.; Daikos, G.L.; Durante-Mangoni, E.; Yahav, D.; Carmeli, Y.; Benattar, Y.D.; Skiada, A.; Andini, R.; Eliakim-Raz, N.; Nutman, A.; et al. Colistin alone versus colistin plus meropenem for treatment of severe infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria: An open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.S.; Prado, G.V.; Costa, S.F.; Grinbaum, R.S.; Levin, A.S. Ampicillin/sulbactam compared with polymyxins for the treatment of infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter spp. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008, 61, 1369–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuji, B.T.; Pogue, J.M.; Zavascki, A.P.; Paul, M.; Daikos, G.L.; Forrest, A.; Giacobbe, D.R.; Viscoli, C.; Giamarellou, H.; Karaiskos, I.; et al. International Consensus Guidelines for the Optimal Use of the Polymyxins: Endorsed by the American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP), European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID), Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), International Society for Anti-infective Pharmacology (ISAP), Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), and Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists (SIDP). Pharmacotherapy 2019, 39, 10–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Routsi, C.; Kokkoris, S.; Douka, E.; Ekonomidou, F.; Karaiskos, I.; Giamarellou, H. High-dose tigecycline-associated alterations in coagulation parameters in critically ill patients with severe infections. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2015, 45, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muralidharan, G.; Micalizzi, M.; Speth, J.; Raible, D.; Troy, S. Pharmacokinetics of tigecycline after single and multiple doses in healthy subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lenhard, J.R.; Smith, N.M.; Bulman, Z.P.; Tao, X.; Thamlikitkul, V.; Shin, B.S.; Nation, R.L.; Li, J.; Bulitta, J.B.; Tsuji, B.T. High-Dose Ampicillin-Sulbactam Combinations Combat Polymyxin-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in a Hollow-Fiber Infection Model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e01268-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Minejima, E.; Mai, N.; Bui, N.; Mert, M.; Mack, W.J.; She, R.C.; Nieberg, P.; Spellberg, B.; Wong-Beringer, A. Defining the Breakpoint Duration of Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia Predictive of Poor Outcomes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 70, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azuhata, T.; Kinoshita, K.; Kawano, D.; Komatsu, T.; Sakurai, A.; Chiba, Y.; Tanjho, K. Time from admission to initiation of surgery for source control is a critical determinant of survival in patients with gastrointestinal perforation with associated septic shock. Crit. Care 2014, 18, R87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sartelli, M.; Catena, F.; Abu-Zidan, F.M.; Ansaloni, L.; Biffl, W.L.; Boermeester, M.A.; Ceresoli, M.; Chiara, O.; Coccolini, F.; De Waele, J.J.; et al. Management of intra-abdominal infections: Recommendations by the WSES 2016 consensus conference. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2017, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Timsit, J.F.; Bassetti, M.; Cremer, O.; Daikos, G.; de Waele, J.; Kallil, A.; Kipnis, E.; Kollef, M.; Laupland, K.; Paiva, J.A.; et al. Rationalizing antimicrobial therapy in the ICU: A narrative review. Intensive Care Med. 2019, 45, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; Paul, S.K.; Akova, M.; Bassetti, M.; De Waele, J.J.; Dimopoulos, G.; Kaukonen, K.M.; Koulenti, D.; Martin, C.; Montravers, P.; et al. DALI: Defining antibiotic levels in intensive care unit patients: Are current beta-lactam antibiotic doses sufficient for critically ill patients? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 1072–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matusik, E.; Boidin, C.; Friggeri, A.; Richard, J.C.; Bitker, L.; Roberts, J.A.; Goutelle, S. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Antibiotic Drugs in Patients Receiving Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy or Intermittent Hemodialysis: A Critical Review. Ther. Drug Monit. 2022, 44, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, G.; Taccone, F.; Villois, P.; Scheetz, M.H.; Rhodes, N.J.; Briscoe, S.; McWhinney, B.; Nunez-Nunez, M.; Ungerer, J.; Lipman, J.; et al. β-Lactam pharmacodynamics in Gram-negative bloodstream infections in the critically ill. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, J.A.; Abdul-Aziz, M.H.; Lipman, J.; Mouton, J.W.; Vinks, A.A.; Felton, T.W.; Hope, W.W.; Farkas, A.; Neely, M.N.; Schentag, J.J.; et al. Individualised antibiotic dosing for patients who are critically ill: Challenges and potential solutions. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roberts, J.A.; Abdul-Aziz, M.H.; Davis, J.S.; Dulhunty, J.M.; Cotta, M.O.; Myburgh, J.; Bellomo, R.; Lipman, J. Continuous versus Intermittent beta-Lactam Infusion in Severe Sepsis. A Meta-analysis of Individual Patient Data from Randomized Trials. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 194, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huttner, A.; Harbarth, S.; Hope, W.W.; Lipman, J.; Roberts, J.A. Therapeutic drug monitoring of the beta-lactam antibiotics: What is the evidence and which patients should we be using it for? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 3178–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curran, J.; Lo, J.; Leung, V.; Brown, K.; Schwartz, K.L.; Daneman, N.; Garber, G.; Wu, J.H.C.; Langford, B.J. Estimating daily antibiotic harms: An umbrella review with individual study meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Dach, E.; Albrich, W.C.; Brunel, A.S.; Prendki, V.; Cuvelier, C.; Flury, D.; Gayet-Ageron, A.; Huttner, B.; Kohler, P.; Lemmenmeier, E.; et al. Effect of C-Reactive Protein-Guided Antibiotic Treatment Duration, 7-Day Treatment, or 14-Day Treatment on 30-Day Clinical Failure Rate in Patients with Uncomplicated Gram-Negative Bacteremia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2020, 323, 2160–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahav, D.; Franceschini, E.; Koppel, F.; Turjeman, A.; Babich, T.; Bitterman, R.; Neuberger, A.; Ghanem-Zoubi, N.; Santoro, A.; Eliakim-Raz, N.; et al. Seven Versus 14 Days of Antibiotic Therapy for Uncomplicated Gram-negative Bacteremia: A Noninferiority Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, J.; Montero-Mateos, E.; Praena-Segovia, J.; Leon-Jimenez, E.; Natera, C.; Lopez-Cortes, L.E.; Valiente, L.; Rosso-Fernandez, C.M.; Herrero, M.; Aller-Garcia, A.I.; et al. Seven-versus 14-day course of antibiotics for the treatment of bloodstream infections by Enterobacterales: A randomized, controlled trial. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, M.A.; Branche, A.; Neeser, O.L.; Wirz, Y.; Haubitz, S.; Bouadma, L.; Wolff, M.; Luyt, C.E.; Chastre, J.; Tubach, F.; et al. Procalcitonin-guided Antibiotic Treatment in Patients with Positive Blood Cultures: A Patient-level Meta-analysis of Randomized Trials. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Fevre, L.; Timsit, J.F. Duration of antimicrobial therapy for Gram-negative infections. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 33, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiala, J.; Palraj, B.R.; Sohail, M.R.; Lahr, B.; Baddour, L.M. Is a single set of negative blood cultures sufficient to ensure clearance of bloodstream infection in patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia? The skip phenomenon. Infection 2019, 47, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuehl, R.; Morata, L.; Boeing, C.; Subirana, I.; Seifert, H.; Rieg, S.; Kern, W.V.; Kim, H.B.; Kim, E.S.; Liao, C.-H.; et al. Defining persistent Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia: Secondary analysis of a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 1409–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, M.C.; Tunkel, A.R.; McKhann, G.M., 2nd; van de Beek, D. Brain abscess. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Bayer, A.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Daum, R.S.; Fridkin, S.K.; Gorwitz, R.J.; Kaplan, S.L.; Karchmer, A.W.; Levine, D.P.; Murray, B.E. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52, e18–e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martin-Loeches, I.; Antonelli, M.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Dimopoulos, G.; Einav, S.; De Waele, J.J.; Garnacho-Montero, J.; Kanj, S.S.; Machado, F.R.; Montravers, P.; et al. ESICM/ESCMID task force on practical management of invasive candidiasis in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2019, 45, 789–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olearo, F.; Kronig, I.; Masouridi-Levrat, S.; Chalandon, Y.; Khanna, N.; Passweg, J.; Medinger, M.; Mueller, N.J.; Schanz, U.; Van Delden, C.; et al. Optimal Treatment Duration of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infections in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Recipients. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020, 7, ofaa246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabre, V.; Amoah, J.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Tamma, P.D. Antibiotic Therapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa Bloodstream Infections: How Long Is Long Enough? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69, 2011–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muff, S.; Tabah, A.; Que, Y.A.; Timsit, J.F.; Mermel, L.; Harbarth, S.; Buetti, N. Short-Course Versus Long-Course Systemic Antibiotic Treatment for Uncomplicated Intravascular Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections due to Gram-Negative Bacteria, Enterococci or Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci: A Systematic Review. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2021, 10, 1591–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebeisen, U.P.; Atkinson, A.; Marschall, J.; Buetti, N. Catheter-related bloodstream infections with coagulase-negative staphylococci: Are antibiotics necessary if the catheter is removed? Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2019, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Urinary | Respiratory | Intra-Abdominal | Intra Vascular Catheter | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community acquired | Enterobacterales Enterococcus sp. P. aeruginosa * | Streptococcus pneumoniae ++ Legionella sp. *** Enterobacterales S. aureus P. aeruginosa * H. influenzae | Enterobacterales Enterococcus sp. Candida sp. Anaerobes Polymicrobial | Coagulase neg. staphylococci S. aureus Enterobacterales |

| Hospital acquired | Enterobacterales Candida sp. Enterococcus sp. P. aeruginosa Acinetobacter sp. | Enterobacterales S. aureus P. aeruginosa Acinetobacter sp. | Enterobacterales P. aeruginosa Enterococcus sp. Candida sp. Anaerobes Polymicrobial | Enterobacterales S. aureus Coagulase neg. staphylococci P. aeruginosa Acinetobacter sp. |

| Individual factors (history) | Recent hospitalisation (1 year) Exposure to antimicrobials (3–6 months) Severe co-morbidities (Charlson ≥ 4) Recent immunosuppression Chronic respiratory disease (COPD, cystic fibrosis) Recurrent urinary tract infections Urinary catheter |

| Individual factors (current) | Prior duration of hospital and ICU stay (continuous increase over time) High severity Known colonisation (surveillance cultures and previous infections) |

| Institution factors | Regional/institutional prevalence of MDR Overwhelmed health systems |

| Antimicrobial | Specific Targets | Dosing Strategies | Caution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-lactam antibiotics | |||

| Ampicillin–sulbactam | CRAB | 9 g q8h (CI/EI) | High dosing increases risk of neurotoxicity |

| Ampicillin or amoxicillin | Narrow-spectrum targeted therapy | 2 g q6h (II) | |

| Amoxicillin–clavulanic acid | Narrow-spectrum targeted therapy CA-peritonitis | 2 g/200 mg q6h (II) | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | Broad-spectrum antipseudomonal probabilistic for HAI | 4.5 g q6h EI/CI preferred, loading dose req. | Biliary excretion Resistance promotion |

| Antistaphylococcal molecules | |||

| Flucloxacillin | MSSA | 2 g q4–6h (II/CI) | |

| Cefazolin | MSSA | 2 g q8h | |

| Ceftaroline | MRSA/VISA/VRSE | 600 mg q8h | Neutropenia especially in longer treatments |

| Ceftobiprole | MRSA, MRSE, non-MDR GNB | 500 mg q8h (2h EI) | Q4–6 h depending on degree of ARC Dose adjust in renal impairment |

| Vancomycin | MRSA/MRSE/E. faecium | LD 30 mg/kg followed by 30 mg/kg (CI) or 15 mg/kg q12h(II) | TDM required |

| Daptomycin | MRSA/MRSE/VRE | 8–10 mg/kg q24h | |

| Linezolid | MRSA/MRSE/VRE | 600 mg q12h | |

| Cephalosporins | |||

| Ceftriaxone | CAP Susceptible Enterobacterales | 1 g q12h EI | |

| Cefotaxime | CAP Susceptible Enterobacterales | 1 g q6h EI CI suggested | |

| Ceftazidime | Pseudomonas sp., Acinetobacter sp. | 2 g q8h ((EI/CI) | |

| Cefepime | AmpC-Es | 2 g q8h EI | MIC ≥ 4 risk of ESBL-Es and treatment failure Most neurotoxic β-lactam, especially in overdose |

| Cefiderocol | CREs (KPCs, OXA48, MBLs), DTR-PA | 2 g q8h EI (3 h) | Poor efficacy for CRAB |

| Carbapenems | |||

| Imipenem-cilastatin | Broad spectrum Probabilistic for HAI Targeted ESBL-Es Pseudomonas sp., Acinetobacter sp. | 1 g q6–8h (II) | |

| Meropenem | 1–2 g q8h (II, EI, CI) | Poor efficacy against Enterococcus sp. | |

| Ertapenem | ESBLE-Es | 1–2 g/24 h (II) | |

| New combinations * | |||

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | CREs (KPCs, OXA-48) | 2 g/500 mg q8h (II/EI) | |

| Aztreonam (+CAZ-AVI) | MBL-CREs, DTR-PA, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 2 g q8h | Infuse aztreonam at same time with CAZ-AVI |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | DTR-PA | 2 g/1 g q8h (II) | |

| Aztreonam–avibactam | MBL-CREs | 2 g/500 mg q8h (II) | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | KPC-CREs, DTR-PA | 2 g/2 g q8h IV (II/EI) | |

| Imipenem–relebactam | KPC-CREs, DTR-PA | 500 mg/250 mg q6h (II) | |

| Aminoglycosides | Combination to extend spectrum when at risk for MDR. ESBL-Es, AmpC-Es, CREs, CRAB, DTR-PA. | Once-Daily dose | Nephrotoxicity Ototoxicity TDM required |

| Amikacin | 25–30 mg/kg (/24h) | ||

| Gentamicin | 7–8 mg/kg (/24h) | ||

| Polymyxins | CREs (KPCs, OXA48, MBLs) CRAB, DTR-PA Resistant to new/targeted antibiotics | Last-line antimicrobials Nephrotoxicity Use TDM if available | |

| Polymyxin B | Systemic infections | Loading dose 2–2.5 mg/ kg (20,000–25,000 IU/kg) 12-hourly injections of 1.25–1.5 mg/kg (12,500–15,000 IU/kg TBW) | Not renally adjusted Very few data on DTR BSIs |

| Colistin (CMS) | Urinary source | Loading dose of 300 mg CBA (9 MUI) then 12–24 h later: 300–360 mg CBA/day (9–10 MUI/day) divided in 2 injections | Renally adjusted More nephrotoxicity than polymyxin B |

| Other classes | |||

| Ciprofloxacin | ESBL-Es, AmpC-Es, MDR-PA, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 400 mg q8–12h (II/EI) | |

| Fosfomycin | CREs (KPCs, OXA48, MBLs) CRAB, DTR-PA | Salvage therapy if susceptible Combination if possible | |

| Tigecycline | CREs (KPCs, OXA48, MBLs) CRAB | 100 mg LD then 50 mg q12h OR 200 mg (LD) then 100 mg q12h | Caution with coagulopathy if high dose Use as part of combination |

| Eravacycline | CREs (KPCs, OXA48, MBLs), CRAB | 1 mg/kg q12h (II) | |

| Cotrimoxazole (TMP/SMX) | ESBL-Es, AmpC-Es, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 1.2–1.6 g SMX q8h (II) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tabah, A.; Lipman, J.; Barbier, F.; Buetti, N.; Timsit, J.-F.; on behalf of the ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Critically Ill Patients—ESGCIP. Use of Antimicrobials for Bloodstream Infections in the Intensive Care Unit, a Clinically Oriented Review. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11030362

Tabah A, Lipman J, Barbier F, Buetti N, Timsit J-F, on behalf of the ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Critically Ill Patients—ESGCIP. Use of Antimicrobials for Bloodstream Infections in the Intensive Care Unit, a Clinically Oriented Review. Antibiotics. 2022; 11(3):362. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11030362

Chicago/Turabian StyleTabah, Alexis, Jeffrey Lipman, François Barbier, Niccolò Buetti, Jean-François Timsit, and on behalf of the ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Critically Ill Patients—ESGCIP. 2022. "Use of Antimicrobials for Bloodstream Infections in the Intensive Care Unit, a Clinically Oriented Review" Antibiotics 11, no. 3: 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11030362

APA StyleTabah, A., Lipman, J., Barbier, F., Buetti, N., Timsit, J.-F., & on behalf of the ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Critically Ill Patients—ESGCIP. (2022). Use of Antimicrobials for Bloodstream Infections in the Intensive Care Unit, a Clinically Oriented Review. Antibiotics, 11(3), 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11030362