Scoping Review of National Antimicrobial Stewardship Activities in Eight African Countries and Adaptable Recommendations

Abstract

:1. Background

- What is the current status of AMR?

- What programmes of AMS and IPC are currently in place for human and animal health?

- What national policies and guidelines exist to support these programmes?

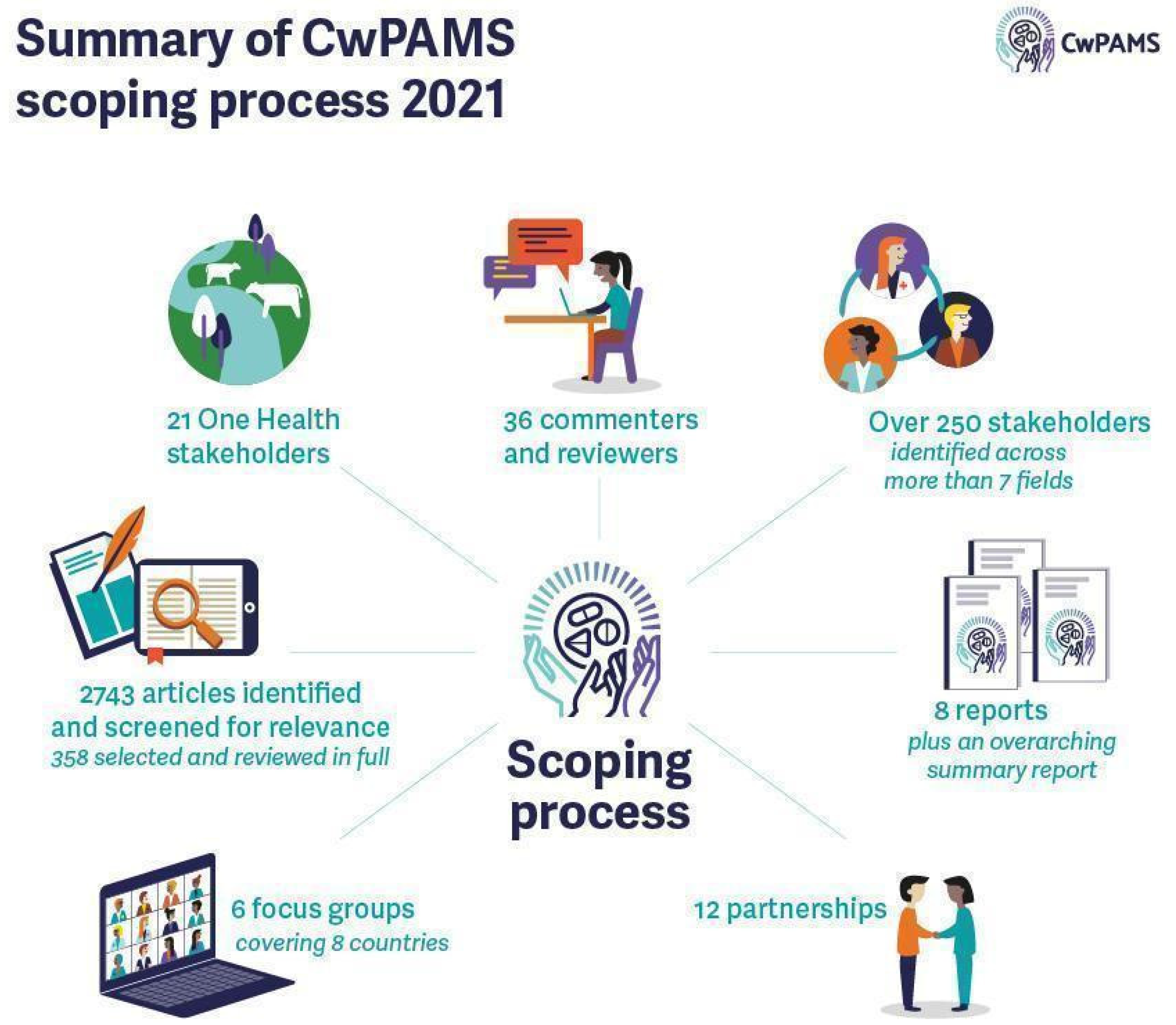

2. Methods

3. Findings

3.1. The Current Status of Antimicrobial Resistance

3.2. Antimicrobial Use, Monitoring, and Stewardship

3.3. Infection Prevention and Control (IPC)

3.4. Use of WHO Tools and Participation in Assessments

3.5. National AMR Strategies and Their Status of Implementation

3.6. Notable Themes in National Action Plans

3.7. Surveillance of Antimicrobial Use (Including Point Prevalence Survey)

3.8. Guidelines on Antimicrobial Use

3.9. Behavioural Barriers to AMS

- Unrestricted access to antimicrobial medicines without prescription due to limited enforcement of legisla-tion;

- Individuals use antimicrobials to try to prevent infection, rather than using for treatment;

- Unaffordability of antimicrobials results in purchasing less than prescribed and patients tend not to finish their prescribed courses;

- Self-medication is common with medicines from market vendors, pharmacies, and drugs shared between friends and family;

- There is a lack of medical supplies, and long distances to health facilities;

- Poor attitudes of medical professionals towards patients;

- The misuse of antibiotics in hospitals, while not well documented, is evident, and there are no national guidelines for the use of antibiotics in intensive care unit (ICUs);

- Guidelines are not adhered to and hardly used, which may be due to a lack of faith in the advice;

- Up-to-date information on AMR is limited and not circulated or collated to be available from one source, so it does not influence clinical practice. This has led to the prescription of antibiotics being a matter of trial and error;

- Financial incentives exist through privately selling antibiotics in hospitals;

- Polypharmacy, including antimicrobials, and the use of fixed-dose combinations;

- Poor enforcement of laws and regulations on the handling of medicines. In addition, many drug shops and private clinics do not conform to the required standards and remain operational in many districts;

- Lack of diagnostic tests in medical decision-making, increasing or decreasing the probability of infection in a patient based on the result;

- Poor education on IPC and AMR;

- Characteristics of the facility and the healthcare worker, such as the healthcare worker’s knowledge and the availability of supplies, suggest that improvements will require a broader focus on behavioural change. Findings also emphasise the need to create hospital leadership buy-in in order to overcome challenges in effective AMS programme implementation, in the response to AMR.

3.10. Initiatives to Improve AMS

- The African Institute for Development Policy (AFIDEP) developed awareness materials, such as comic strips and fact and information sheets, in the local Chichewa language in Malawi [34].

- The Drivers of Resistance in Uganda and Malawi (DRUM) consortium is a multi-stakeholder project working in Malawi and Uganda, researching AMR in humans, animals, and the environment [35].

- Nigeria utilises social media to promote AMS awareness and has an AMR Awareness Facebook page, where information is shared to support the implementation of the Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance and minimise the impact of AMR on human health, animal health, and the environment [36].

- A project was conducted to increase the awareness of AMR from February 2nd to May 13th, 2019, in Nigeria. The project used community outreach and social media to raise awareness about AMR and address issues, such as misconceptions and knowledge gaps. The student-led project had over 200,000 likes on Facebook, demonstrating how social media can be a powerful tool to reach the masses [37].

- In collaboration with relevant ministries, departments, and agencies in the animal and human health sectors, Nigeria’s Centre for Disease Control participates in World Antimicrobial Awareness Week activities every year. In 2020, under the theme ‘Antimicrobials: Handle with care’, several activities were conducted. These included a webinar regarding operationalising One Health interventions on AMS, engagement with livestock farmers, and training with Fleming Fund Fellows on AMR and antimicrobial use (AMU) surveillance [38].

- ReAct Africa assists countries, such as Zambia and Ghana, by bringing together experts and key stakeholders to form technical working groups on AMR. They ensure a multi-sectoral, holistic approach to AMR, targeting the general public, as well as the health, veterinarian, agricultural, and environmental sectors. Their role is to also increase collaboration with other relevant networks and organisations [39].

- In Kenya, both public and private hospitals, such as the Kenyatta National Hospital, Aga Khan University Hospital, and The Nairobi Hospital, have developed and implemented AMS programmes. They have observed significant adherence to AMU guidelines in surgical prophylaxis, restricted carbapenem, and other reserve antibiotic use, resulting in a decline in multi-drug resistant infections and candidemia. Other hospitals are in the process of establishing AMS teams with mentorship from hospitals that have implemented AMS programmes. Insights from the focus group discussions showed initiatives and unpublished documentation on AMS in the country. There is ongoing work with the United States Agency for International Development - Medicines, Technologies, and Pharmaceutical Services (MTaPS) Program (USAID-MTaPS), Fleming Fund, ReAct, CDC, WHO, FAO, and OIE.

- In 2017, Mbeya Zonal Referral Hospital (MZRH) and the University of South Carolina (UofSC) agreed on a collaborative project to strengthen antimicrobial prescribing in the southern highlands of Tanzania and train a new generation of clinicians in responsible AMU and adherence to national guidelines [40].

3.11. Guidelines on Infection Prevention and Control

3.12. One Health Initiative in Relation to Antimicrobial Stewardship

3.12.1. One Health Approach

3.12.2. Raising Awareness of AMR in The Animal Health Sector

3.12.3. Antimicrobial Use and Stewardship in Farms

3.12.4. Veterinarians and AMS

3.12.5. Antimicrobial Surveillance in Animal and Environmental Sectors

3.13. Stakeholder and AMR Coordinating Committee (AMRCC) Engagement

- Assessment of various curricula to determine the extent of inclusion of AMR content;

- Situation analysis of sanitary and phytosanitary measures, IPC, and biosecurity;

- Periodic studies on the efficacy of antimicrobials.

3.14. Digital Health

3.14.1. Advances in the Use of E-Prescribing

3.14.2. Use of Medicines Supply Apps or Software

3.15. Coverage of AMR and AMS in Pharmacy Training

3.16. Access to Antimicrobials, Supply of Medicines

3.17. Access to Medicines via Community Pharmacy

- Poor and inefficient public health systems;

- Lack of policies nor strict enforcement;

- Dispensing of antimicrobials in partial doses;

- Sub-optimal AMR knowledge and attitudes among pharmacy personnel;

- Lack of antimicrobial sensitivity knowledge in patients and clients.

3.18. Impact of COVID-19

4. Conclusions

5. Recommendations

- Develop national AMS plans or guideline documents to facilitate the implementation of national action plans on AMR.

- Increase the number of AMS programmes in healthcare facilities through national roll-outs of successful pilot programmes.

- Incorporate AMS in the curricula for pre-service and in-service training of pharmacists and other healthcare professionals in the national health budget to increase human resources for the in-country implementation of national AMR programmes.

- Identify National Action Plan indicators that need to be improved or upgraded.

- Increase capacity and recognition of technical working groups on AMS.

- Provide technical support to increase the workforce and streamline processes to improve monitoring and evaluation (M&E) for NAPs (Most countries did not have enough literature on the status of AMS implementation).

- Update hospital/healthcare clinical guidelines to include AMS principles and integration of the Access, Watch and Reserve (AWaRe) classification of antibiotics. These customisable guidelines can also be incorporated into existing digital and e-health applications, such as DHIS-2 to optimise prescriptions. The shift towards digitisation can potentially improve antimicrobial prescribing through easy access to information and records.

- Improvement and enforcement of regulations regarding sales of prescription-only antibiotics (There were notable gaps in the policies that govern the sale of antibiotics, especially in community pharmacies. It is important to harness advances in digital technology where possible).

- Streamlining and strengthening national medicine supply chain systems to ensure the consistent availability of quality-assured antimicrobials.

- Encouraging more policies and government regulatory frameworks on the distribution and manufacturing of quality-assured health products at the national level.

- Incorporate bottleneck analysis of national supply chains to identify root causes and human behaviour influencing them.

- The establishment of AMS programmes that incorporate medical supply chain management to facilitate rational antimicrobial selection, procurement, use, monitoring, storage, distribution, and supply.

- The improvement of national quality control and assurance systems of pharmaceuticals to reduce the prevalence of substandard and falsified antimicrobials within the country’s distribution systems and channels.

- The provision of incentives to support AMS programmes and further inclusion/collaboration into/with IPC, WASH, TB and other health programmes in all healthcare facilities.

- The prioritisation of institutionalising and subsequent decentralisation of One Health activities to the sub-national level for implementation, fostering operation, and capacity building.

- Expanding national AMU and AMR surveillance programmes and AMR/AMS awareness campaigns targeted at the stakeholders and MDAs in the animal, food processing, agriculture, and environmental health sectors to enhance coverage.

- The involvement of pharmacists and pharmacy associations further in the implementation of national AMS activities.

- At every opportunity, strengthen and foster partnerships and opportunities that ensure the inclusion of all relevant stakeholders/actors (nationally and internationally) in the implementation of AMS activities.

- The encouragement of more AMR and/or One Health-driven research collaborations between government and non-government stakeholders, with the aim of enhancing the implementation of NAPs.

- Conduct a comprehensive ethnographic study on the use and misuse of antimicrobial drugs in human and animal health, agriculture, and the environment to adequately inform antimicrobial stewardship initiatives.

- Use of digital health tools to support AMS. In Kenya, Sierra Leone, Zambia, and Malawi, it was noted that there is a need for easy access to prescribing information through an app.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elton, L.; Thomason, M.J.; Tembo, J.; Velavan, T.P.; Pallerla, S.R.; Arruda, L.B.; Vairo, F.; Montaldo, C.; Ntoumi, F.; Hamid, M.M.A.; et al. Antimicrobial resistance preparedness in sub-Saharan African countries. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2020, 9, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.J.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance Review. 2016. Available online: https://amr-review.org/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Commonwealth Pharmacists Association. Commonwealth Partnership for Antimicrobial Stewardship (CwPAMS) Toolkit. 2020. Available online: https://commonwealthpharmacy.org/cwpams-toolkit/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Masich, A.M.; Vega, A.D.; Callahan, P.; Herbert, A.; Fwoloshi, S.; Zulu, P.M.; Chanda, D.; Chola, U.; Mulenga, L.; Hachaambwa, L.; et al. Antimicrobial usage at a large teaching hospital in Lusaka, Zambia. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Action Plan on Prevention and Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance, 2017–2022. WHO Regional Office for Africa. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/publications/national-action-plan-prevention-and-containment-antimicrobial-resistance-2017-2022 (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Infection and Prevention Control & WASH Guidelines for Malawi; Ministry of Health Malawi: Lilongwe, Malawi, 2020.

- Commonwealth Pharmacists Association. Commonwealth Partnership for Antimicrobial Stewardship (CwPAMS). Available online: https://commonwealthpharmacy.org/cwpams/ (accessed on 28 March 2022).

- World Health Organization. Joint External Evaluation of IHR Core Capacities of the Republic of Uganda: Mission Report: 26–30 June 2017; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259164 (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- World Health Organization. Joint External Evaluation of IHR Core Capacities of the Republic of Uganda: Executive Summary, 26–30 June 2017; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/258730 (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- World Health Organization. Joint External Evaluation of IHR Core Capacities of the Republic of Zambia: Mission Report, 7–11 August 2017; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259675 (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Khuluza, F.; Haefele-Abah, C. The availability, prices and affordability of essential medicines in Malawi: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Joint External Evaluation of IHR Core Capacities of the Republic of Malawi: Mission Report: 11–15 February 2019; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/325321 (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Antimicrobial Use and Resistance in Nigeria: Situation Analysis and Recommendations. 2017. Available online: https://www.proceedings.panafrican-med-journal.com/conferences/2018/8/2/abstract/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- World Health Organization. Joint External Evaluation of IHR Core Capacities of the United Republic of Tanza-nia-Zanzibar: Mission Report, 22–28 April 2017; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/258696 (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Water, Sanitation and Hygiene in Health Care Facilities: Practical Steps to Achieve Universal Access; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Lyus, R.; Pollock, A.; Ocan, M.; Brhlikova, P. Registration of antimicrobials, Kenya, Uganda and United Republic of Tanzania, 2018. Bull. World Health Organ. 2020, 98, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gates Foundation Project. Alliance for the Prudent Use of Antibiotics. Antibiotic Resistance Situation Analysis and Needs Assessment (ARSANA) in Uganda and Zambia. 2022. Available online: https://apua.org/gates-foundation-project (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care: First Global Patient Safety Challenge Clean Care Is Safer Care. Geneva: World Health Organization. The Burden of Health Care-Associated Infection. 2019. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK144030/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Bedoya, G.; Dolinger, A.; Rogo, K.; Mwaura, N.; Wafula, F.; Coarasa, J.; Goicoechea, A.; Das, J. Observations of infection prevention and control practices in primary health care, Kenya. Bull. World Health Organ. 2017, 95, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashinyo, M.E.; Dubik, S.D.; Duti, V.; Amegah, K.E.; Ashinyo, A.; Asare, B.A.; Ackon, A.A.; Akoriyea, S.K.; Kuma-Aboagye, P. Infection prevention and control compliance among exposed healthcare workers in COVID-19 treatment centers in Ghana: A descriptive cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS) Report: Early Implementation 2016–2017; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris. (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Horumpende, P.G.; Sonda, T.B.; Van Zwetselaar, M.; Antony, M.L.; Tenu, F.F.; Mwanziva, C.E.; Shao, E.R.; Mshana, S.E.; Mmbaga, B.T.; Chilongola, J. Prescription and non-prescription antibiotic dispensing practices in part I and part II pharmacies in Moshi Municipality, Kilimanjaro Region in Tanzania: A simulated clients approach. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS) Report: Early Implementation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS) Report: Early Implementation 2017–2018; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- World Health Organization. WHO Report on Surveillance of Antibiotic Consumption: 2016–2018 Early Implementation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/277359 (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- UNAS; CDDEP; GARP-Uganda; Mpairwe, Y.; Wamala, S. Antibiotic Resistance in Uganda: Situation Analysis and Recommendations (pp. 107). Kampala, Uganda: Uganda National Academy of Sciences; Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy. 2015. Available online: https://www.cddep.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/uganda_antibiotic_resistance_situation_reportgarp_uganda_0-1.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Seale, A.C.; Hutchison, C.; Fernandes, S.; Stoesser, N.; Kelly, H.; Lowe, B.; Turner, P.; Hanson, K.; Chandler, C.I.; Goodman, C.; et al. Supporting surveillance capacity for antimicrobial resistance: Laboratory capacity strengthening for drug resistant infections in low and middle income countries. Wellcome Open Res. 2017, 2, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- African Journal of Clinical and Experimental Microbiology. (n.d.). Antimicrobial Stewardship Implementation in Nigerian Hospitals: Gaps and Challenges. Available online: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajcem/article/view/203077 (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Mehtar, S.; Wanyoro, A.; Ogunsola, F.; Ameh, E.A.; Nthumba, P.; Kilpatrick, C.; Revathi, G.; Antoniadou, A.; Giamarelou, H.; Apisarnthanarak, A.; et al. Implementation of surgical site infection surveillance in low- and middle-income countries: A position statement for the International Society for Infectious Diseases. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 100, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambakusi, C.S. Knowledge, attitudes and practices related to self-medication with antimicrobials in Lilongwe, Malawi. Malawi Med. J. 2019, 31, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antimicrobial Resistance—AMR Awareness. Facebook. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/amr.nigeria/. (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Adebisi, Y. Lesson learned from student-led one hundred days awareness on antimicrobial resistance in Nigeria. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 101, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raising Public Awareness on Antibiotic Resistance in Malawi: Antibiotic Awareness Week 2019. African Institute for Development Policy—AFIDEP. Available online: https://www.afidep.org/raising-public-awareness-on-antibiotic-resistance-in-malawi-antibiotic-awareness-week-2019/ (accessed on 28 March 2022).

- Drivers of Resistance in Uganda and Malawi. African Institute for Development Policy—AFIDEP. Available online: https://www.afidep.org/publication/info-sheet-drivers-of-resistance-in-uganda-and-malawi/ (accessed on 28 March 2022).

- Nigeria Centre for Disease Control. AMR Situation Analysis. Available online: https://ncdc.gov.ng/diseases/guidelines (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- ReAct Africa—A global network. ReAct. Available online: https://www.reactgroup.org/about-us/a-global-network/react-africa/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Hall, J.W.; Bouchard, J.; Bookstaver, P.B.; Haldeman, M.S.; Kishimbo, P.; Mbwanji, G.; Mwakyula, I.; Mwasomola, D.; Seddon, M.; Shaffer, M.; et al. The Mbeya Antimicrobial Stewardship Team: Implementing Antimicrobial Stewardship at a Zonal-Level Hospital in Southern Tanzania. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Database for the Tripartite Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Country Self-Assessment Survey (TrACSS). Available online: http://amrcountryprogress.org/ (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- FAO. Evaluation of FAO’s Role and Work on Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR).Thematic Evaluation Series, 03/2021. Rome . 2021. Available online: http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cb3680en/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Sierra Leone. Fleming Fund. Available online: https://www.flemingfund.org/countries/sierra-leone/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Ghana National Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance 2017–2021.pdf. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/ghana-national-action-plan-for-antimicrobial-use-and-resistance (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Andoh, L.A.; Dalsgaard, A.; Obiri-Danso, K.; Newman, M.J.; Barco, L.; Olsen, J.E. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella serovars isolated from poultry in Ghana. Epidemiol. Infect. 2016, 144, 3288–3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donkor, E.S.; Newman, M.J.; Yeboah-Manu, D. Epidemiological aspects of non-human antibiotic usage and resistance: Implications for the control of antibiotic resistance in Ghana. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2012, 17, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoh, S.; Adekanmbi, O.; Jiba, D.F.; Deen, G.F.; Gashau, W.; Sevalie, S.; Klein, E.Y. Antibiotic use among hospitalized adult patients in a setting with limited laboratory infrastructure in Freetown Sierra Leone, 2017–2018. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 90, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Antibiotic Resistance Partnership—Tanzania Working Group. Situation Analysis and Recommendations: Anti-biotic Use and Resistance in Tanzania. Washington, DC and New Delhi: Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy. 2015. Available online: https://cddep.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/garp-tz_situation_analysis-1.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Pharmacy Assistant Training Program—VillageReach. Available online: https://www.villagereach.org/impact/pharmacy-assistant-training-program/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Alhaji, N.B.; Isola, T.O. Antimicrobial usage by pastoralists in food animals in North-central Nigeria: The associated socio-cultural drivers for antimicrobials misuse and public health implications. One Health 2018, 6, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesokan, H.K.; Akanbi, I.O.; Akanbi, I.M.; Obaweda, R.A. Pattern of antimicrobial usage in livestock animals in south-western Nigeria: The need for alternative plans. Onderstepoort J. Veter- Res. 2015, 82, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra Leone. Terms of Reference for Request for Proposals. Available online: https://1doxu11lv4am2alxz12f0p5j-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/7135a0cec08f827c92300d81b0c2e002.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Kimera, Z.I.; Mshana, S.E.; Rweyemamu, M.M.; Mboera, L.E.G.; Matee, M.I.N. Antimicrobial use and resistance in food-producing animals and the environment: An African perspective. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2020, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multi-sectoral National Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance 2017–2027. Government of the Republic of Zambia. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/zambia-multi-sectoral-national-action-plan-on-antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- NAFDAC—National Agency for Food & Drug Administration & Control. Available online: https://www.nafdac.gov.ng/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Dacombe, R.; Bates, I.; Gopul, B.; Owusu-Ofori, A. Overview of the Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Systems for Ghana, Ma-lawi, Nepal and Nigeria. Available online: https://www.flemingfund.org/wp-content/uploads/b1ef6816d1e94134427b27f4c118ebae.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Sub-Saharan Africa, The Mobile Economy. Available online: https://www.gsma.com/mobileeconomy/sub-saharan-africa/ (accessed on 28 March 2022).

- District Health Information System 2 (DHIS2). Open Health News. Available online: https://www.openhealthnews.com/resources/district-health-information-system-2-dhis2 (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Olaoye, O.; Tuck, C.; Khor, W.P.; McMenamin, R.; Hudson, L.; Northall, M.; Panford-Quainoo, E.; Asima, D.M.; Ashiru-Oredope, D. Improving Access to Antimicrobial Prescribing Guidelines in 4 African Countries: Development and Pilot Implementation of an App and Cross-Sectional Assessment of Attitudes and Behaviour Survey of Healthcare Workers and Patients. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technology & Medicine. Telemedicine Charity. The Virtual Doctors. Available online: https://www.virtualdoctors.org/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Omotosho, A.; Emuoyibofarhe, J.; Ayegba, P.; Meinel, C. E-Prescription in Nigeria: A Survey. J. Glob. Pharma Technol. 2018, 10, 58–64. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330825533_E-Prescription_in_Nigeria_A_Survey (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- MyDawa Brand the First ever Retail License for an e-Retailing Pharmacy in Kenya. CIO East Africa. Available online: https://www.cio.co.ke/mydawa-brand-the-first-ever-retail-license-for-an-e-retailing-pharmacy-in-kenya/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- SanJoaquin, M.A.; Allain, T.J.; Molyneux, M.E.; Benjamin, L.; Everett, D.B.; Gadabu, O.; Rothe, C.; Nguipdop, P.; Chilombe, M.; Kazembe, L.; et al. Surveillance Programme of IN-patients and Epidemiology (SPINE): Implementation of an Electronic Data Collection Tool within a Large Hospital in Malawi. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antimicrobial Stewardship Improved by MicroGuide No 1 Medical Guidance. Available online: http://www.test.microguide.eu/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Liang, L.; Wiens, M.O.; Lubega, P.; Spillman, I.; Mugisha, S. A Locally Developed Electronic Health Platform in Uganda: Development and Implementation of Stre@mline. JMIR Form. Res. 2018, 2, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kariuki, J.; Njeru, M.K.; Wamae, W.; Mackintosh, M. Local Supply Chains for Medicines and Medical Supplies in Kenya: Under-standing the Challenges. Africa Portal. African Centre for Technology Studies (ACTS). 2015. Available online: https://www.africaportal.org/publications/local-supply-chains-for-medicines-and-medical-supplies-in-kenya-understanding-the-challenges/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Kalungia, A.C.; Muungo, L.T.; Marshall, S.; Apampa, B.; May, C.; Munkombwe, D. Training of pharmacists in Zambia: Developments, curriculum structure and future perspectives. Pharm. Educ. 2019, 19, 69–78. Available online: https://pharmacyeducation.fip.org/pharmacyeducation/article/view/638 (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Librarian, I. Assessment of the Pharmaceutical Human Resources in Tanzania and the Strategic Framework. Available online: https://www.hrhresourcecenter.org/node/3269.html (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Partnership between Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital and North Middlesex University Hospital NHS Trust. Fleming Fund. Available online: https://www.flemingfund.org/publications/about-the-partnership-between-korle-bu-teaching-hospital-and-north-middlesex-university-hospital-nhs-trust/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Blogs—The Medicines, Technologies, and Pharmaceutical Services (MTaPs) Program. Available online: https://www.mtapsprogram.org/news-type/blogs/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Banga, K.; Keane, J.; Mendez-Parra, M.; Pettinotti, L.; Sommer, L. Africa Trade and COVID-19. Available online: https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/Africa_trade_and_Covid19_the_supply_chain_dimension.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Manji, I.; Manyara, S.M.; Jakait, B.; Ogallo, W.; Hagedorn, I.C.; Lukas, S.; Kosgei, E.J.; Pastakia, S.D. The Revolving Fund Pharmacy Model: Backing up the Ministry of Health supply chain in western Kenya. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2016, 24, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, H.; Maurer, C.; Willborn, R.J. Impact of Drug Shortages on Patient Safety and Pharmacy Operation Costs. Fed. Pract. 2018, 35, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Shafiq, N.; Pandey, A.K.; Malhotra, S.; Holmes, A.; Mendelson, M.; Malpani, R.; Balasegaram, M.; Charani, E. Shortage of essential antimicrobials: A major challenge to global health security. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e006961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awosan, K.J.; Ibitoye, P.K.; Abubakar, A.K. Knowledge, risk perception and practices related to antibiotic resistance among patent medicine vendors in Sokoto metropolis, Nigeria. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2018, 21, 1476–1483. [Google Scholar]

- Bonniface, M.; Nambatya, W.; Rajab, K. An Evaluation of Antibiotic Prescribing Practices in a Rural Refugee Settlement District in Uganda. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Enrolment to GLASS-AMR | WHO Joint External Evaluation (JEE) | WHO Methodology for PPS | National Action Plans | WHO WASH FIT | WHO Global Plan on AMR | Global TrACSS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghana | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Kenya | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Malawi | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Nigeria | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Sierra Leone | x | x | x | x | |||

| Tanzania | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Uganda | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Zambia | x | x | x | x | x |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kamere, N.; Garwe, S.T.; Akinwotu, O.O.; Tuck, C.; Krockow, E.M.; Yadav, S.; Olawale, A.G.; Diyaolu, A.H.; Munkombwe, D.; Muringu, E.; et al. Scoping Review of National Antimicrobial Stewardship Activities in Eight African Countries and Adaptable Recommendations. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11091149

Kamere N, Garwe ST, Akinwotu OO, Tuck C, Krockow EM, Yadav S, Olawale AG, Diyaolu AH, Munkombwe D, Muringu E, et al. Scoping Review of National Antimicrobial Stewardship Activities in Eight African Countries and Adaptable Recommendations. Antibiotics. 2022; 11(9):1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11091149

Chicago/Turabian StyleKamere, Nduta, Sandra Tafadzwa Garwe, Oluwatosin Olugbenga Akinwotu, Chloe Tuck, Eva M. Krockow, Sara Yadav, Agbaje Ganiyu Olawale, Ayobami Hassan Diyaolu, Derick Munkombwe, Eric Muringu, and et al. 2022. "Scoping Review of National Antimicrobial Stewardship Activities in Eight African Countries and Adaptable Recommendations" Antibiotics 11, no. 9: 1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11091149

APA StyleKamere, N., Garwe, S. T., Akinwotu, O. O., Tuck, C., Krockow, E. M., Yadav, S., Olawale, A. G., Diyaolu, A. H., Munkombwe, D., Muringu, E., Muro, E. P., Kaminyoghe, F., Ayotunde, H. T., Omoniyei, L., Lawal, M. O., Barlatt, S. H. A., Makole, T. J., Nambatya, W., Esseku, Y., ... Ashiru-Oredope, D. (2022). Scoping Review of National Antimicrobial Stewardship Activities in Eight African Countries and Adaptable Recommendations. Antibiotics, 11(9), 1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11091149