Bacteriophage Adsorption: Likelihood of Virion Encounter with Bacteria and Other Factors Affecting Rates

Abstract

:1. Introduction

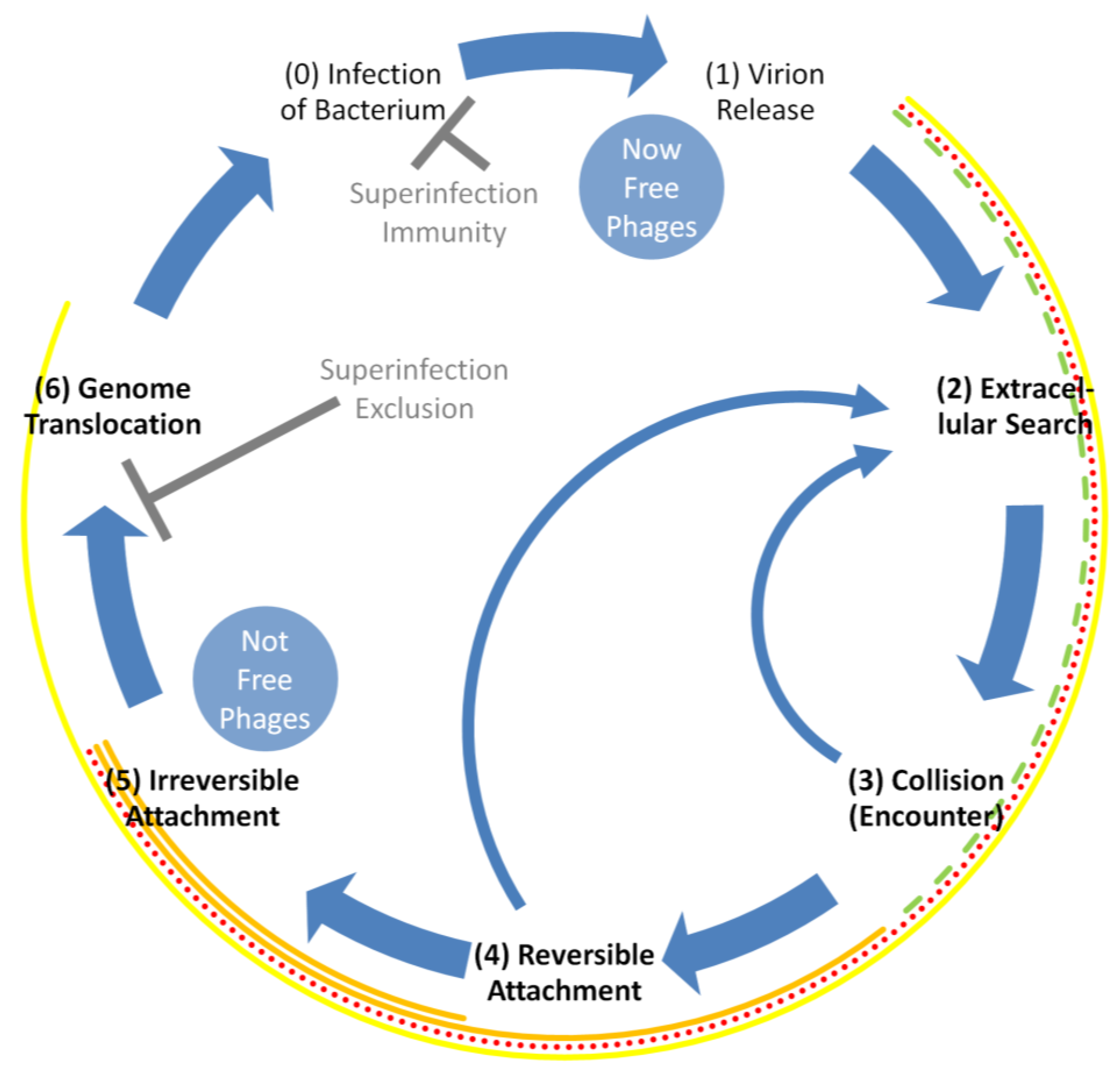

2. Phage Adsorption within the Phage Life Cycle

- (0)

- Infection →

- (1)

- Release (of virions from a cell) →

- (2)

- Movement (of virions; a.k.a., ‘extracellular search’ or ‘transport’ [1]) →

- (3)

- Collision (a.k.a., encounter, of virions with a potentially adsorbable bacterium) →

- (4)

- Reversible attachment (of a virion to a cell’s surface [8]) →

- (5)

- Irreversible attachment (of a virion to a cell’s surface) →

- (6)

- Translocation (of a phage genome into a bacterium’s cytoplasm) →

- (0)

- Infection.

2.1. More-Truncated Descriptions of Phage Adsorption

2.2. The Phage Adsorption Rate Constant

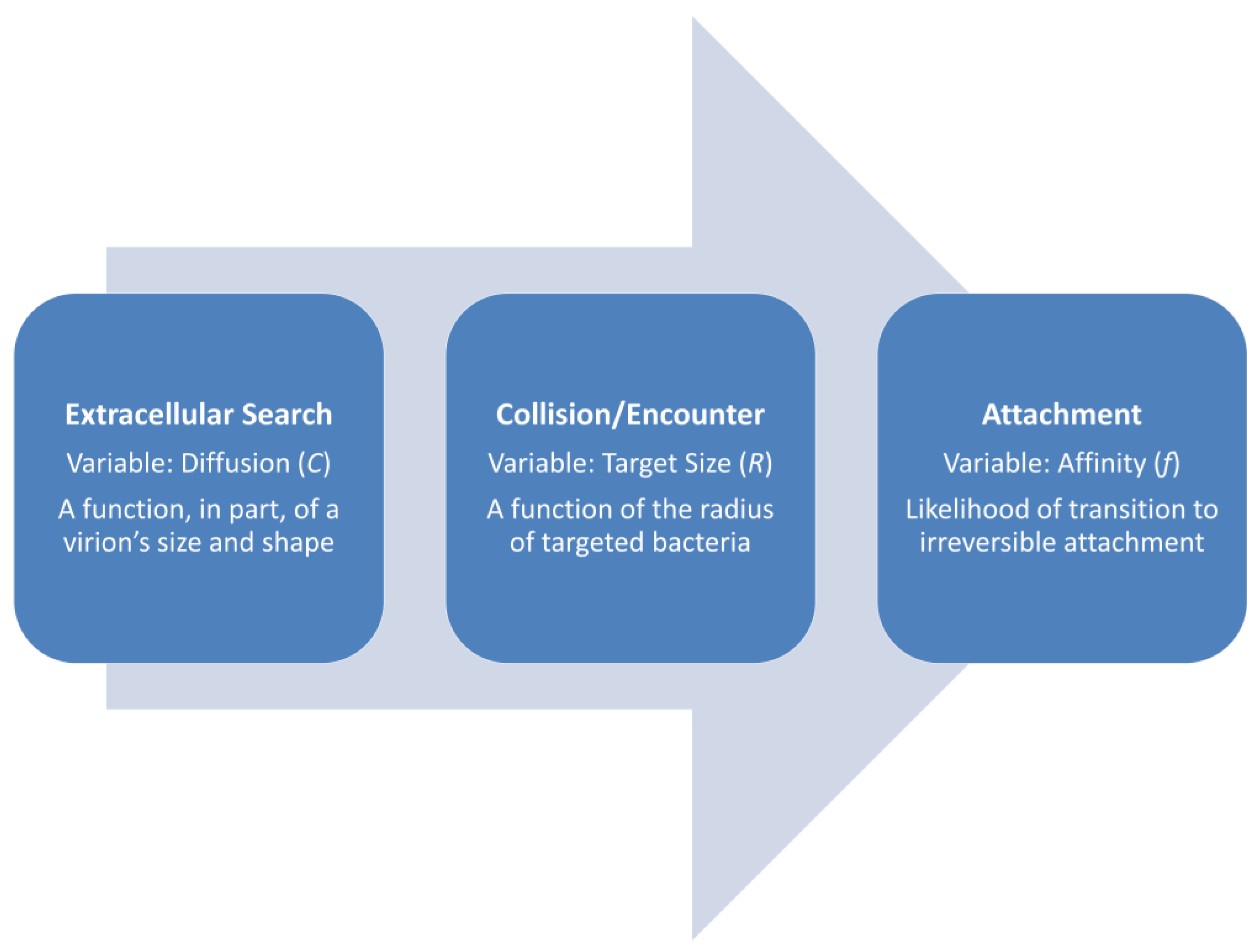

- To limit descriptions of particle motion to just that of virion diffusion (that is, assuming that hosts are comparably stationary and that viruses only move as a consequence of diffusion; see Section 3 for exceptions to the latter). Diffusion here is abbreviated as C, after Stent [8], for the diffusion Constant.

- To limit considerations of particle size to just that of host cells, assuming that virions are small relative to the size of bacteria, though note that ‘jumbo’ phages do exist for which that size discrepancy is not as great [27].

- To invoke considerations of collision efficiency to describe the likelihood of virion attachment to a bacterium given encounter with that bacterium. The latter here is abbreviated as f, also after Stent, which is for efficiency. This particularly is the efficiency of the transition from step (3) to step (5) as considered above (Figure 2).

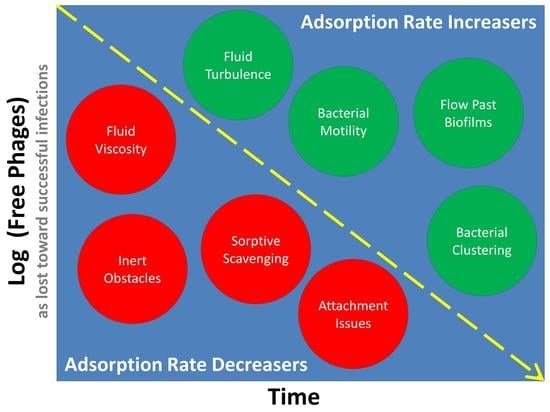

2.3. Adsorption Rate Generalizations

2.4. Phage Adsorption Rates

2.5. Importance of Different Variables and Parameters

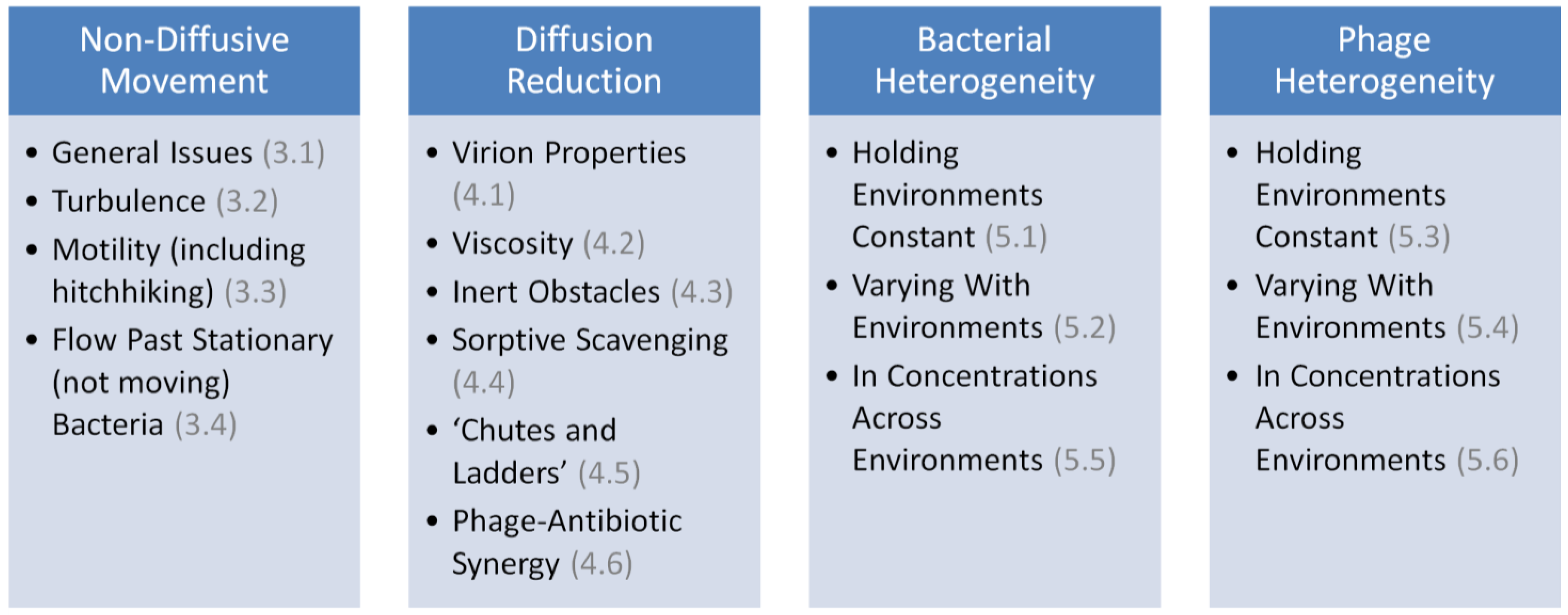

3. Non-Diffusive Movement

3.1. Anticipated Impact of Relative Movement (Theory)

3.2. Turbulence

3.3. Motility

3.4. Flow Past Stationary (Not-Moving) Bacteria

4. Reductions in Rates of Virion Diffusion

4.1. Virion Properties

4.2. Viscosity

4.3. Inert Obstacles

4.4. Sorptive Scavenging

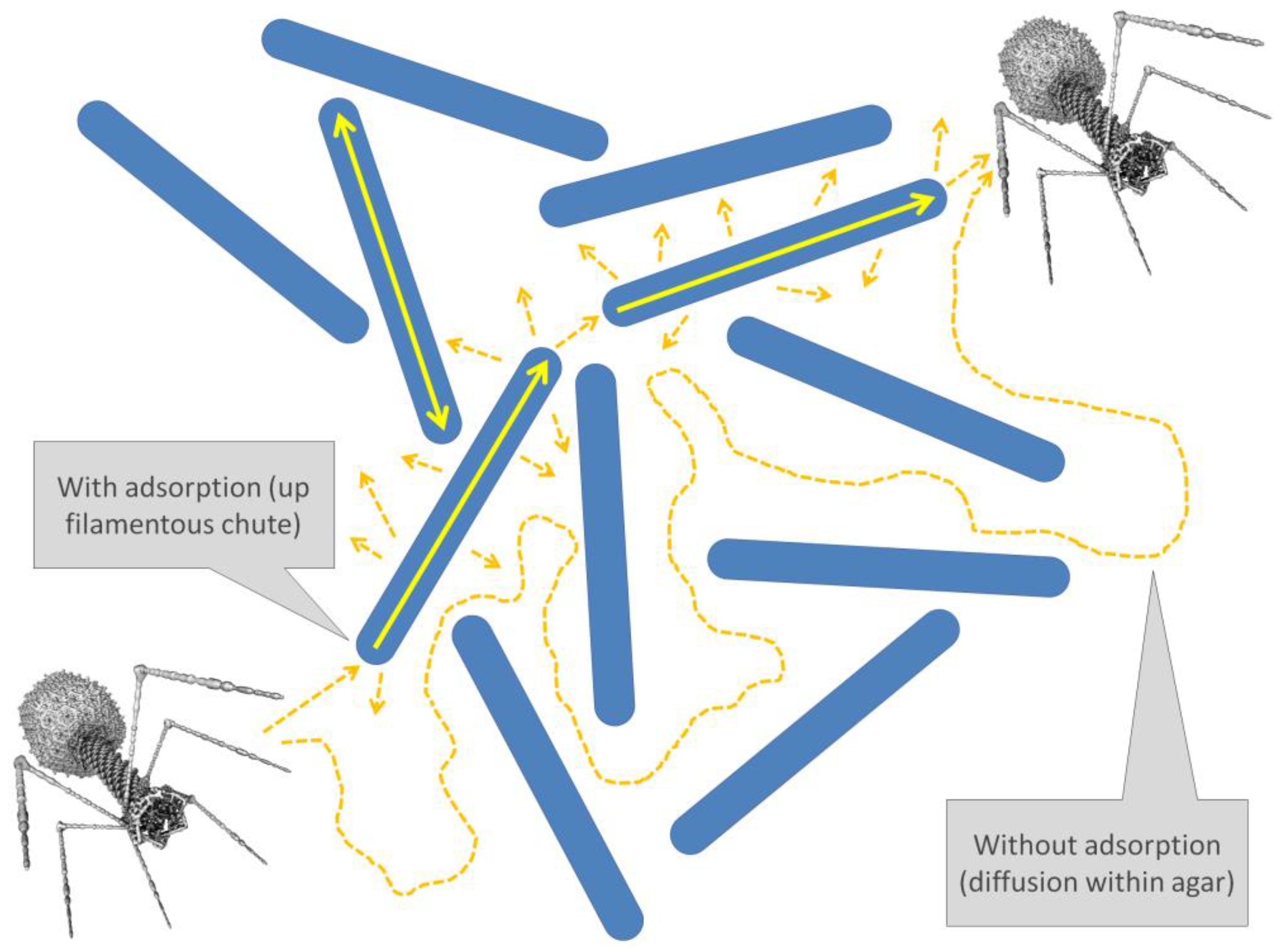

4.5. Chutes and Ladders

4.6. Phage–Antibiotic Synergy

5. Adsorption Rate Heterogeneity

5.1. Bacterial Heterogeneity across Populations

5.2. Bacterial Heterogeneity as a Function of Environments

5.3. Phage Heterogeneity across Populations

5.4. Phage Heterogeneity as a Function of Environments

5.5. Heterogeneity in Bacterial Concentrations

5.6. Heterogeneity in Phage Concentrations

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

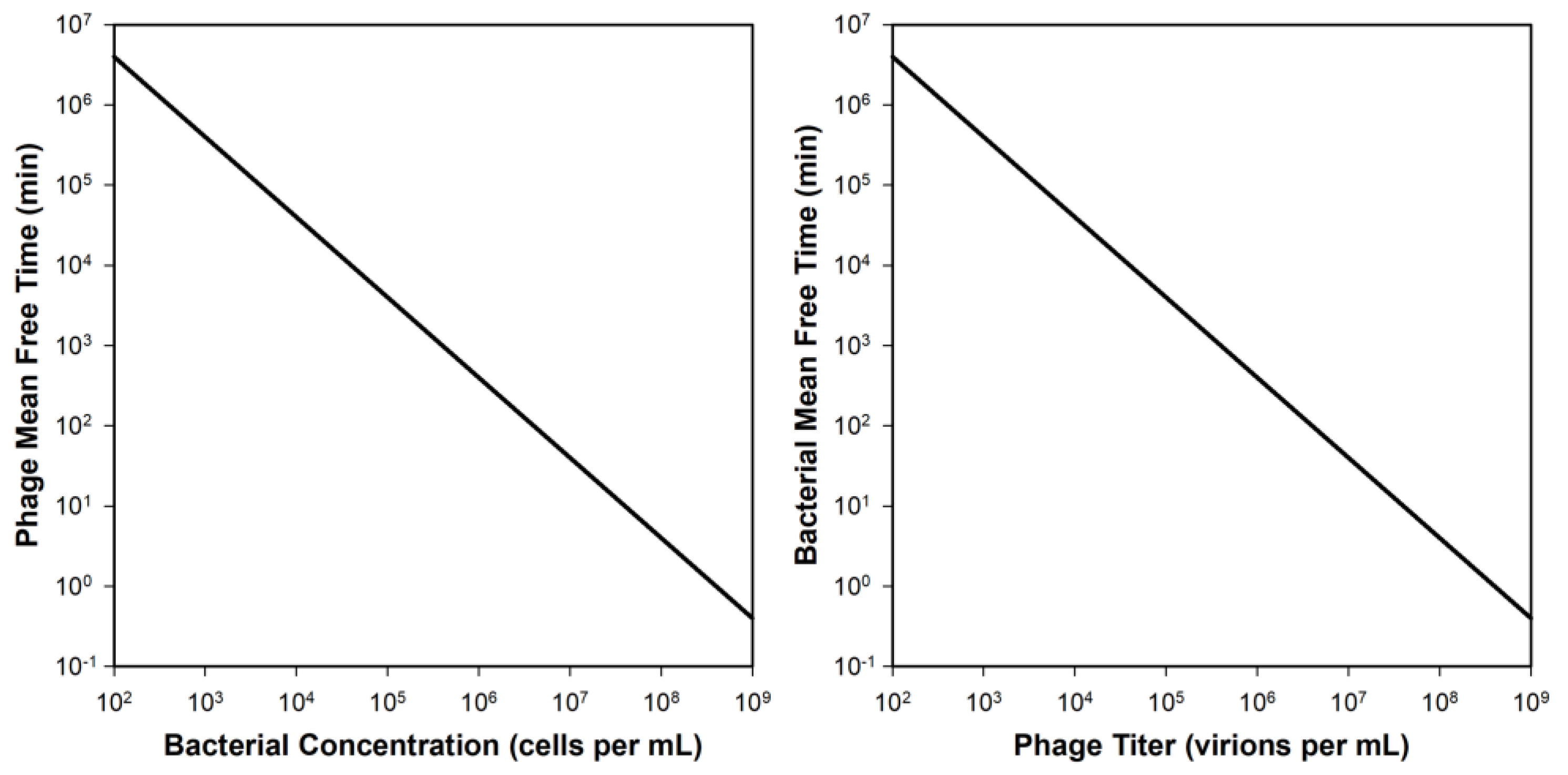

Appendix A. Dependence of Adsorption Rates on Phage and Bacterial Concentrations

Appendix A.1. Phage Adsorption Rate Theory

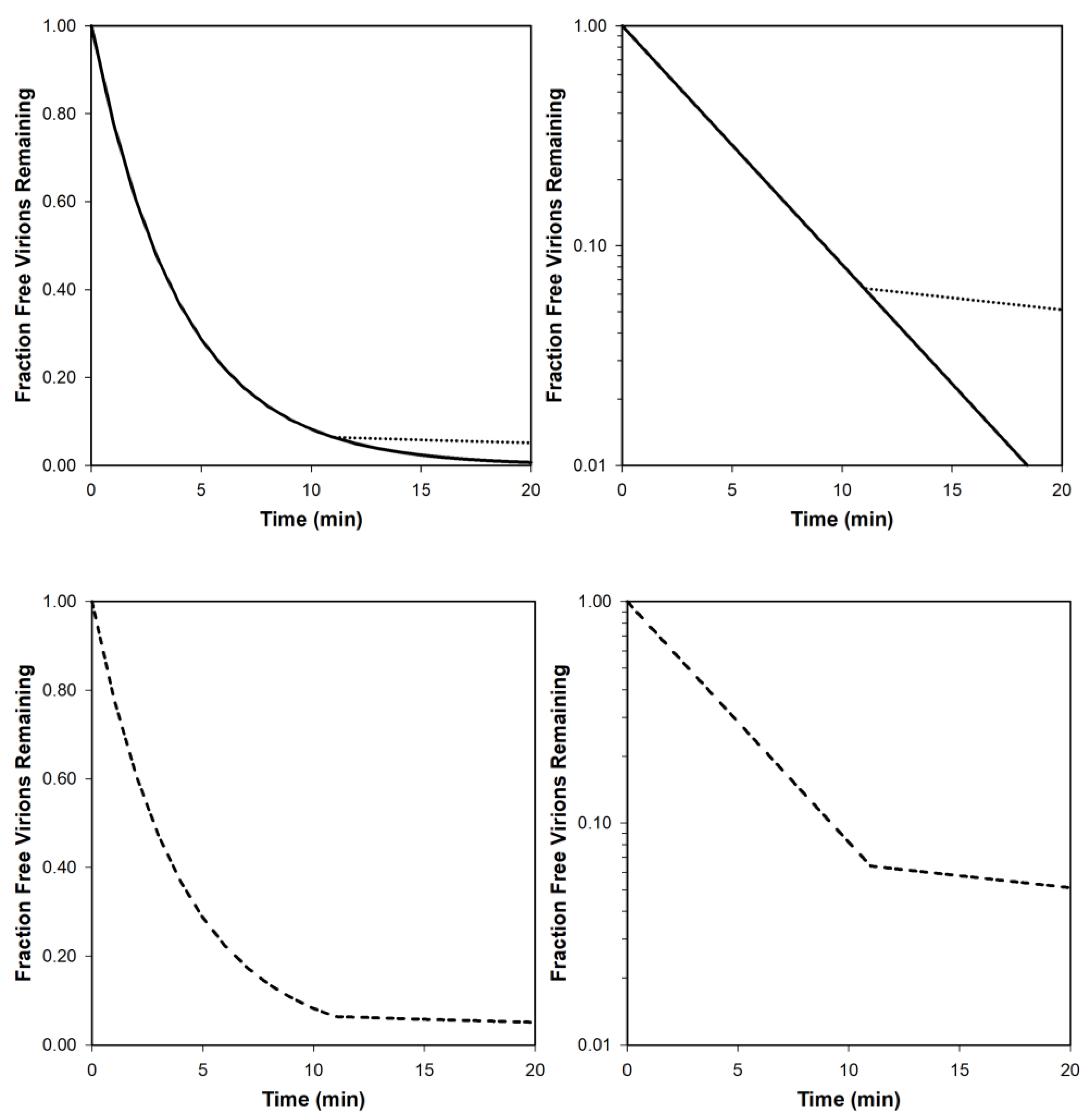

Appendix A.2. Rate of Loss of Individual Virions to Adsorption

Appendix A.3. Rate of Loss of Individual Bacteria to Phage Adsorption

Appendix A.4. Once More, but without Calculus

Appendix A.4.1. Fraction of Phages Adsorbing

Appendix A.4.2. Fraction of Bacteria Adsorbed

| t → | 1 | 5 | 10 | 30 | 60 | 120 | 180 | 240 | 300 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P ↓ | Unadsorbed bacteria (percentage) as based on Equation (A10): | ||||||||

| 105 | 100% | 100% | 99% | 97% | 94% | 89% | 84% | 79% | 74% |

| 106 | 99% | 95% | 90% | 74% | 55% | 30% | 17% | 9% | 5% |

| 107 | 90% | 61% | 37% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 108 | 37% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 109 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 1010 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| t → | 1 | 5 | 10 | 30 | 60 | 120 | 180 | 240 | 300 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P ↓ | Unadsorbed bacteria (percentage) as based on Equation (A10): | ||||||||

| 105 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 99% | 99% | 98% | 98% | 97% |

| 106 | 100% | 100% | 99% | 97% | 94% | 89% | 84% | 79% | 74% |

| 107 | 99% | 95% | 90% | 74% | 55% | 30% | 17% | 9% | 5% |

| 108 | 90% | 61% | 37% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 109 | 37% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 1010 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| t → | 1 | 5 | 10 | 30 | 60 | 120 | 180 | 240 | 300 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P ↓ | Unadsorbed bacteria (percentage) as based on Equation (A10): | ||||||||

| 105 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| 106 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 99% | 99% | 98% | 98% | 97% |

| 107 | 100% | 100% | 99% | 97% | 94% | 89% | 84% | 79% | 74% |

| 108 | 99% | 95% | 90% | 74% | 55% | 30% | 17% | 9% | 5% |

| 109 | 90% | 61% | 37% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 1010 | 37% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| t → | 1 | 5 | 10 | 30 | 60 | 120 | 180 | 240 | 300 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P ↓ | Unadsorbed bacteria (percentage) as based on Equation (A10): | ||||||||

| 105 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| 106 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| 107 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 99% | 99% | 98% | 98% | 97% |

| 108 | 100% | 100% | 99% | 97% | 94% | 89% | 84% | 79% | 74% |

| 109 | 99% | 95% | 90% | 74% | 55% | 30% | 17% | 9% | 5% |

| 1010 | 90% | 61% | 37% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

Appendix A.4.3. Not All Phage Adsorptions Are to Not Yet Adsorbed Bacteria

References

- Murray, A.G.; Jackson, G.A. Viral dynamics: A model of the effects of size, shape, motion, and abundance of single-celled planktonic organisms and other particles. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1992, 89, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, D.R. Biological control by microorganisms. In eLS; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górski, A.; Międzybrodzki, R.; Borysowski, J. Phage Therapy: A Practical Approach; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee, S.A.; Hatfull, G.F.; Mutalik, V.K.; Schooley, R.T. Phage therapy: From biological mechanisms to future directions. Cell 2023, 186, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, J.J.; Regoes, R.R. Pharmacodynamics of non-replicating viruses, bacteriocins and lysins. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2006, 273, 2703–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- d’Herelle, F. Immunity in Natural Infectious Disease; Williams & Wilkins Co.: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1924. [Google Scholar]

- Abedon, S.T. Further considerations on how to improve phage therapy experimentation, practice, and reporting: Pharmacodynamics perspectives. Phage 2022, 3, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stent, G.S. Molecular Biology of Bacterial Viruses; WH Freeman and Co.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Delbrück, M. Adsorption of bacteriophage under various physiological conditions of the host. J. Gen. Physiol. 1940, 23, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adams, M.H. Bacteriophages; InterScience: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman, P.; Abedon, S.T. Practical methods for determining phage growth parameters. Meth. Mol. Biol. 2009, 501, 175–202. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Miyanaga, K.; Tanji, Y. Diffusion of bacteriophages through artificial biofilm models. Biotechnol. Prog. 2012, 28, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedon, S.T. Pathways to phage therapy enlightenment, or why I’ve become a scientific curmudgeon. Phage 2022, 3, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumby, N.; Edwards, A.M.; Davidson, A.R.; Maxwell, K.L. The bacteriophage HK97 gp15 moron element encodes a novel superinfection exclusion protein. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 5012–5019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abedon, S.T. Look who’s talking: T-even phage lysis inhibition, the granddaddy of virus-virus intercellular communication research. Viruses 2019, 11, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shi, K.; Oakland, J.T.; Kurniawan, F.; Moeller, N.H.; Banerjee, S.; Aihara, H. Structural basis of superinfection exclusion by bacteriophage T4 Spackle. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrich, T.N.; Hatfull, G.F. Evolution of superinfection immunity in Cluster A mycobacteriophages. MBio 2019, 10, e00971-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koch, A.L. Encounter efficiency of coliphage-bacterium interaction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1960, 39, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, E. Recognition, attachment, and injection. In Bacteriophage T4; Mathews, C.K., Kutter, E.M., Mosig, G., Berget, P.B., Eds.; American Society for Microbiology: Washington, DC, USA, 1983; pp. 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, E.; Grinius, L.; Letellier, L. Recognition, attachment, and injection. In The Molecular Biology of Bacteriophage T4; Karam, J.D., Kutter, E., Carlson, K., Guttman, B., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 347–356. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, H.; Hu, M.; Zhao, G.; Du, Y.; Xu, N.; Chen, X.; Jiao, X. The “fighting wisdom and bravery” of tailed phage and host in the process of adsorption. Microbiol. Res. 2020, 230, 126344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molineux, I.J.; Panja, D. Popping the cork: Mechanisms of phage genome ejection. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storms, Z.J.; Smith, L.; Sauvageau, D.; Cooper, D.G. Modeling bacteriophage attachment using adsorption efficiency. Biochem. Eng. J. 2012, 64, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoluchowski, M.V. Attempt at a mathematical theory of the coagulation kinetics of colloidal solutions. Z. Phys. Chem. 1917, 92, 129–168. [Google Scholar]

- Storms, Z.J.; Sauvageau, D. Modeling tailed bacteriophage adsorption: Insight into mechanisms. Virology 2015, 485, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meyer, C.J.; Deglon, D.A. Particle collision modeling—A review. Miner. Eng. 2011, 24, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, A.; Ali, A.; Qing, H.; Tong, Y. Emerging aspects of jumbo bacteriophages. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 5041–5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, J.B.; Storms, Z.; Sauvageau, D. Host receptors for bacteriophage adsorption. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2016, 363, fnw002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hyman, P. Phage receptor. In Reference Module in Life Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, M. The adsorption of coliphage lambda to its host: Effect of variation in the surface density of the receptor and in phage-receptor affinity. J. Mol. Biol. 1976, 103, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stent, G.S.; Wollman, E.L. On the two step nature of bacteriophage adsorption. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1952, 8, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennehy, J.J.; Abedon, S.T. Adsorption: Phage acquisition of bacteria. In Bacteriophages: Biology, Technology, Therapy; Harper, D., Abedon, S.T., Burrowes, B.H., McConville, M., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 93–117. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, T.F. The reactions of bacterial viruses with their host cells. Botan. Rev. 1949, 15, 464–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershey, A.D.; Chase, M. Independent functions of viral protein and nucleic acid in growth of bacteriophage. J. Gen. Physiol. 1952, 36, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhwa, N.; Berg, H.C. Bacterial motility: Machinery and mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 2022, 20, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttenplan, S.B.; Kearns, D.B. Regulation of flagellar motility during biofilm formation. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2013, 37, 849–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berg, H.C.; Purcell, E.M. Physics of chemoreception. Biophys. J. 1977, 20, 193–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abedon, S.T. Phage “delay” towards enhancing bacterial escape from biofilms: A more comprehensive way of viewing resistance to bacteriophages. AIMS Microbiol. 2017, 3, 186–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, D.; Wang, T.; Fraebel, D.T.; Maslov, S.; Sneppen, K.; Kuehn, S. Hitchhiking, collapse, and contingency in phage infections of migrating bacterial populations. ISME J. 2020, 14, 2007–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, J.J.; Auro, R.; Furlan, M.; Whiteson, K.L.; Erb, M.L.; Pogliano, J.; Stotland, A.; Wolkowicz, R.; Cutting, A.S.; Doran, K.S.; et al. Bacteriophage adhering to mucus provide a non-host-derived immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 10771–10776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barr, J.J.; Auro, R.; Sam-Soon, N.; Kassegne, S.; Peters, G.; Bonilla, N.; Hatay, M.; Mourtada, S.; Bailey, B.; Youle, M.; et al. Subdiffusive motion of bacteriophage in mucosal surfaces increases the frequency of bacterial encounters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 13675–13680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abedon, S.T. Ecology of anti-biofilm agents II: Bacteriophage exploitation and biocontrol of biofilm bacteria. Pharmaceuticals 2015, 8, 559–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trubl, G.; Hyman, P.; Roux, S.; Abedon, S.T. Coming-of-age characterization of soil viruses: A user’s guide to virus isolation, detection within metagenomes, and viromics. Soil Syst. 2020, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Igler, C.; Abedon, S.T. Commentary: A host-produced quorum-sensing autoinducer controls a phage lysis-lysogeny decision. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dennehy, J.J.; Abedon, S.T. Bacteriophage ecology. In Bacteriophages: Biology, Technology, Therapy; Harper, D., Abedon, S.T., Burrowes, B.H., McConville, M., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 253–294. [Google Scholar]

- Sisler, F.D. The Transmission of Bacteriophage by Mosquitoes; MS University of Maryland: College Park, MD, USA, 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Dennehy, J.J.; Friedenberg, N.A.; Yang, Y.W.; Turner, P.E. Bacteriophage migration via nematode vectors: Host-parasite-consumer interactions in laboratory microcosms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 1974–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, Z.; Schwarz, C.; Zhu, L.; Chen, L.; Shen, Y.; Yu, P. Hitchhiking behavior in bacteriophages facilitates phage infection and enhances carrier bacteria colonization. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 2462–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, X.; Kallies, R.; Kuhn, I.; Schmidt, M.; Harms, H.; Chatzinotas, A.; Wick, L.Y. Phage co-transport with hyphal-riding bacteria fuels bacterial invasion in a water-unsaturated microbial model system. ISME J. 2022, 16, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, X.; Klose, N.; Kallies, R.; Harms, H.; Chatzinotas, A.; Wick, L.Y. Mycelia-assisted isolation of non-host bacteria able to co-transport phages. Viruses 2022, 14, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedon, S.T. Spatial vulnerability: Bacterial arrangements, microcolonies, and biofilms as responses to low rather than high phage densities. Viruses 2012, 4, 663–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saltzman, W.M. Tissue Engineering: Principles for the Design of Replacement Organs and Tissues; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zwanzig, R. On the relation between self–diffusion and viscosity of liquids. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 4507–4508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serwer, P.; Wright, E.T. In-gel isolation and characterization of large (and other) phages. Viruses 2020, 12, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elford, W.J.; Andrewes, C.H. The sizes of different bacteriophages. Brit. J. Exp. Path. 1932, 13, 446–456. [Google Scholar]

- Hershey, A.D. Mutation of bacteriophage with respect to type of plaque. Genetics 1946, 31, 620–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellenberger, E.; Bolle, A.; Boy de la Tour, E.; Epstein, R.H.; Franklin, N.C.; Jerne, N.K.; Reale-Scafati, A.; Séchaud, J.; Bendet, I.; Goldstein, D.; et al. Functions and properties related to tail fibers of bacteriophage T4. Virology 1965, 26, 419–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, M.P.; Wood, W.B. Bacteriophage T4 whiskers: A rudimentary environment-sensing device. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1975, 72, 3701–3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharp, D.G.; Hook, A.E.; Taylor, A.R.; Beard, D.; Beard, J.W. Sedimentation characters and pH stability of the T2 bacteriophage of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1946, 165, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.; Talley, S.K. The viscosity of aqueous solutions as a function of the concentration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1933, 55, 624–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omni Claculator Water Viscocity Calculator. 2023. Available online: https://www.omnicalculator.com/physics/water-viscosity (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Késmárky, G.; Kenyeres, P.; Rábai, M.; Tóth, K. Plasma viscosity: A forgotten variable. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2008, 39, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankaran, J.; Tan, N.J.H.J.; But, K.P.; Cohen, Y.; Rice, S.A.; Wohland, T. Single microcolony diffusion analysis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2019, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yin, J.; McCaskill, J.S. Replication of viruses in a growing plaque: A reaction-diffusion model. Biophys. J. 1992, 61, 1540–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebrun, L.; Junter, G.A. Diffusion of sucrose and dextran through agar gel membranes. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 1993, 15, 1057–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, E.L.; Bond, M.C.; Koskella, B.; Drescher, K.; Bucci, V.; Nadell, C.D. Biofilm structure promotes coexistence of phage-resistant and phage-susceptible bacteria. mSystems 2020, 5, e00877-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winans, J.B.; Wucher, B.R.; Nadell, C.D. Multispecies biofilm architecture determines bacterial exposure to phages. PLoS Biol. 2022, 20, e3001913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, S.; Fernandez, L.; Gutierrez, D.; Campelo, A.B.; Rodriguez, A.; Garcia, P. Analysis of different parameters affecting diffusion, propagation and survival of staphylophages in bacterial biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedon, S.T. Phage Tails as Polymeric Substance Probes: Arguments for and Against. 2016. Available online: https://asmallerflea.org/2016/11/13/phage-tails-as-polymeric-substance-probes-arguments-for-and-against/ (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Wilkinson, J.F. The extracellualr polysaccharides of bacteria. Bacteriol. Rev. 1958, 22, 46–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedon, S.T. Bacteriophage exploitation of bacterial biofilms: Phage preference for less mature targets? FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2016, 363, fnv246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacheron, J.; Heiman, C.M.; Keel, C. Live cell dynamics of production, explosive release and killing activity of phage tail-like weapons for Pseudomonas kin exclusion. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedon, S.T. Frequency-dependent selection in light of phage exposure. In Bacteriophages as Drivers of Evolution: An Evolutionary Ecological Perspective; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 275–292. [Google Scholar]

- Abedon, S.T. Ecology and evolutionary biology of hindering phage therapy: The phage tolerance vs. phage resistance of bacterial biofilms. Antibiotics 2023, 11, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallet, R.; Shao, Y.; Wang, I.-N. High adsorption rate is detrimental to bacteriophage fitness in a biofilm-like environment. BMC Evol. Biol. 2009, 9, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koch, A.L. The growth of viral plaques during the enlargement phase. J. Theor. Biol. 1964, 6, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roychoudhury, P.; Shrestha, N.; Wiss, V.R.; Krone, S.M. Fitness benefits of low infectivity in a spatially structured population of bacteriophages. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2014, 281, 20132563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Morrisette, T.; Kebriaei, R.; Lev, K.L.; Morales, S.; Rybak, M.J. Bacteriophage therapeutics: A primer for clinicians on phage-antibiotic combinations. Pharmacotherapy 2020, 40, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, X.; He, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wei, J.; Hu, T.; Si, J.; Tao, G.; Zhang, L.; Xie, L.; Abdalla, A.E.; et al. A combination therapy of phages and antibiotics: Two is better than one. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 3573–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łusiak-Szelachowska, M.; Międzybrodzki, R.; Drulis-Kawa, Z.; Cater, K.; Knežević, P.; Winogradow, C.; Amaro, K.; Jończyk-Matysiak, E.; Weber-Dąbrowska, B.; Rękas, J.; et al. Bacteriophages and antibiotic interactions in clinical practice: What we have learned so far. J. Biomed. Sci. 2022, 29, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Hong, Q.; Chang, R.Y.K.; Kwok, P.C.L.; Chan, H.K. Phage-antibiotic therapy as a promising strategy to combat multidrug-resistant infections and to enhance antimicrobial efficiency. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirnay, J.P.; Ferry, T.; Resch, G. Recent progress toward the implementation of phage therapy in Western medicine. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2022, 46, fuab040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comeau, A.; Tétart, F.; Trojet, S.A.; Prère, M.-F.; Krisch, H.M. Phage-antibiotic synergy (PAS): β-lactam and quinolone antibiotics stimulate virulent phage growth. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kamal, F.; Dennis, J.J. Burkholderia cepacia complex phage-antibiotic synergy (PAS): Antibiotics stimulate lytic phage activity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 1132–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, M.; Jo, Y.; Hwang, Y.J.; Hong, H.W.; Hong, S.S.; Park, K.; Myung, H. Phage-antibiotic synergy via delayed lysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e02085-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Uchiyama, J.; Shigehisa, R.; Nasukawa, T.; Mizukami, K.; Takemura-Uchiyama, I.; Ujihara, T.; Murakami, H.; Imanishi, I.; Nishifuji, K.; Sakaguchi, M.; et al. Piperacillin and ceftazidime produce the strongest synergistic phage-antibiotic effect in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Arch. Virol. 2018, 163, 1941–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.M.; McCutcheon, J.G.; Dennis, J.J. Aztreonam lysine increases the activity of phages E79 and phiKZ against Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, P.C.; Piatti, G. Kinetics of filamentation of Escherichia coli induced by different sub-MICs of ceftibuten at different times. Chemotherapy 1993, 39, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredborg, M.; Rosenvinge, F.S.; Spillum, E.; Kroghsbo, S.; Wang, M.; Sondergaard, T.E. Automated image analysis for quantification of filamentous bacteria. BMC. Microbiol. 2015, 15, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kaur, S.; Harjai, K.; Chhibber, S. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus phage plaque size enhancement using sublethal concentrations of antibiotics. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 8227–8233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Santos, S.B.; Carvalho, C.M.; Sillankorva, S.; Nicolau, A.; Ferreira, E.C.; Azeredo, J. The use of antibiotics to improve phage detection and enumeration by the double-layer agar technique. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Danis-Wlodarczyk, K.M.; Cai, A.; Chen, A.; Gittrich, M.R.; Sullivan, M.B.; Wozniak, D.J.; Abedon, S.T. Friends or foes? Rapid determination of dissimilar colistin and ciprofloxacin antagonism of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phages. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagami, H.; Endo, H. Loss of lysis inhibition in filamentous Escherichia coli infected with wild-type bacteriophage T4. J. Virol. 1969, 3, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kropinski, A.M. Practical advice on the one-step growth curve. Meth. Mol. Biol. 2018, 1681, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Storms, Z.J.; Brown, T.; Cooper, D.G.; Sauvageau, D.; Leask, R.L. Impact of the cell life-cycle on bacteriophage T4 infection. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2014, 353, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Hu, T.; Wei, J.; He, Y.; Abdalla, A.E.; Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Teng, T. Characterization of a novel bacteriophage Henu2 and evaluation of the synergistic antibacterial activity of phage-antibiotics. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, E.M.; Alkawareek, M.Y.; Donnelly, R.F.; Gilmore, B.F. Synergistic phage-antibiotic combinations for the control of Escherichia coli biofilms in vitro. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2012, 65, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eisenstark, A. Bacteriophage techniques. Meth. Virol. 1967, 1, 449–524. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K.M.; Isberg, R.R. Defining heterogeneity within bacterial populations via single cell approaches. BioEssays 2016, 38, 782–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedon, S.T. Active bacteriophage biocontrol and therapy on sub-millimeter scales towards removal of unwanted bacteria from foods and microbiomes. AIMS Microbiol. 2017, 3, 649–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cota, I.; Sanchez-Romero, M.A.; Hernandez, S.B.; Pucciarelli, M.G.; Garcia-Del, P.F.; Casadesus, J. Epigenetic control of Salmonella enterica O-antigen chain length: A tradeoff between virulence and bacteriophage resistance. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turkington, C.J.R.; Morozov, A.; Clokie, M.R.J.; Bayliss, C.D. Phage-resistant phase-variant sub-populations mediate herd immunity against bacteriophage invasion of bacterial meta-populations. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Porter, N.T.; Hryckowian, A.J.; Merrill, B.D.; Fuentes, J.J.; Gardner, J.O.; Glowacki, R.W.P.; Singh, S.; Crawford, R.D.; Snitkin, E.S.; Sonnenburg, J.L.; et al. Phase-variable capsular polysaccharides and lipoproteins modify bacteriophage susceptibility in Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 1170–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisio, F.; Matic, I.; Radman, M.; Rodrigues, O.R.; Taddei, F. Plasmids spread very fast in heterogeneous bacterial communities. Genetics 2002, 162, 1525–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisio, F. Plasmids survive despite their cost and male-specific phages due to heterogeneity of bacterial populations. Evol. Ecol. Res. 2005, 7, 1089–1107. [Google Scholar]

- Delbrück, M. Bacterial viruses (bacteriophages). Adv. Enzymol. 1942, 2, 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Woody, M.A.; Cliver, D.O. Effects of Temperature and Host Cell Growth Phase on Replication of F-Specific RNA Coliphage QB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 1520–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hadas, H.; Einav, M.; Fishov, I.; Zaritsky, A. Bacteriophage T4 development depends on the physiology of its host Escherichia coli. Microbiology 1997, 143, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sillankorva, S.; Oliveira, R.; Vieira, M.J.; Sutherland, I.W.; Azeredo, J. Bacteriophage Φ S1 infection of Pseudomonas fluorescens planktonic cells versus biofilms. Biofouling 2004, 20, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hoyland-Kroghsbo, N.M.; Maerkedahl, R.B.; Svenningsen, S.L. A quorum-sensing-induced bacteriophage defense mechanism. mBio 2013, 4, e00362-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Storms, Z.J.; Arsenault, E.; Sauvageau, D.; Cooper, D.G. Bacteriophage adsorption efficiency and its effect on amplification. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2010, 33, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storms, Z.J.; Sauvageau, D. Evidence that the heterogeneity of a T4 population is the result of heritable traits. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e116235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallet, R.; Lenormand, T.; Wang, I.N. Phenotypic stochasticity protects lytic bacteriophage populations from extinction during the bacterial stationary phase. Evolution 2012, 66, 3485–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutter, E.; Kellenberger, E.; Carlson, K.; Eddy, S.; Neitzel, J.; Messinger, L.; North, J.; Guttman, B. Effects of bacterial growth conditions and physiology on T4 infection. In The Molecular Biology of Bacteriophage T4; Karam, J.D., Kutter, E., Carlson, K., Guttman, B., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 406–418. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Dai, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Tang, F. Mechanisms of interactions between bacteria and bacteriophage mediate by quorum sensing systems. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 2299–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, P.S.; Franklin, M.J. Physiological heterogeneity in biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Bassler, B.L. Surviving as a community: Antibiotic tolerance and persistence in bacterial biofilms. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedon, S.T. Evolution of bacteriophage latent period length. In Evolutionary Biology: New Perspectives on Its Development; Dickins, T.E., Dickens, B.J.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 375–426. [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowska, K. Phage therapy: What factors shape phage pharmacokinetics and bioavailability? Systematic and critical review. Med. Res. Rev. 2019, 39, 2000–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Payne, R.J.H.; Jansen, V.A.A. Phage therapy: The peculiar kinetics of self-replicating pharmaceuticals. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000, 68, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Payne, R.J.H.; Jansen, V.A.A. Understanding bacteriophage therapy as a density-dependent kinetic process. J. Theor. Biol. 2001, 208, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abedon, S.T.; Thomas-Abedon, C. Phage therapy pharmacology. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2010, 11, 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, M. Adsorption of bacteriophages to homologous bacteria. II Quantitative investigations of adsorption velocity and saturation. Estimation of particle size of the bacteriophage [translation]. In Bacterial Viruses; Stent, G.S., Ed.; Little, Brown and Co.: Boston, MA, USA, 1960; pp. 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Said, M.B.; Masahiro, O.; Hassen, A. Detection of viable but non cultivable Escherichia coli after UV irradiation using a lytic Qbeta phage. Ann. Microbiol. 2010, 60, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, I.-N.; Dykhuizen, D.E.; Slobodkin, L.B. The evolution of phage lysis timing. Evol. Ecol. 1996, 10, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Wang, I.-N. Bacteriophage adsorption rate and optimal lysis time. Genetics 2008, 180, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yanagawa, R.; Shinagawa, M. Characteristics of Corynebacterium renale phage. Jpn. J. Vet. Res. 1968, 16, 137–143. [Google Scholar]

- De Klerk, H.C.; Coetzee, J.N.; Theron, J.J. The characterization of a series of Lactobacillus bacteriophages. Microbiology 1963, 32, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kasman, L.M.; Kasman, A.; Westwater, C.; Dolan, J.; Schmidt, M.G.; Norris, J.S. Overcoming the phage replication threshold: A mathematical model with implications for phage therapy. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 5557–5564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gill, J.J. Modeling of bacteriophage therapy. In Bacteriophage Ecology; Abedon, S.T., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; pp. 439–464. [Google Scholar]

| Term * | Definition |

|---|---|

| Adsorption process | Multi-step progression that involves a combination of virion diffusion, phage encounter with a bacterium, and then various processes of attachment to that bacterium |

| Adsorption rate (dP/dt) | Description of the timing particularly of irreversible virion attachment to bacterial cells, as is a function of the phage adsorption rate constant, phage concentrations, and bacterial concentrations |

| Adsorption rate constant (k) | Description of the intrinsic timing of virion attachment, particularly irreversible attachment to bacteria |

| Attachment | Post-encounter, specific interactions of a virion with a bacterial surface |

| Bacterial concentration (N) | Description of numbers of bacteria within an environment such as in per mL units |

| Collision kernel | Description of the number of collisions expected between particles within a given volume over a given span of time, as involves a particle’s rate of motion, its size, and between-particle affinity |

| Diffusion rate (2) (C) | Random virion motion within and relative to fluid environments; this is a key aspect of particle motion in predicting adsorption rate constants |

| Efficiency (of attachment) (f) | Description of the affinity between particles, such as between a phage virion and targeted bacterium, with affinities ranging from 0 to 1; this otherwise can be described as a collision efficiency in predicting adsorption rate constants |

| Encounter (Collision) (3) | Contact of an extracellular virion with an object such as an adsorbable bacterium |

| Extracellular search (2) | Period starting with phage virion release from a phage-infected bacterium and potentially ending with virion encounter with an adsorbable bacterium |

| Free phage (or free virion) | Extracellular phage particle, contrasting with virions existing prior to their release; the adsorption process involves the conversion of free phages to irreversibly attached virions |

| Genome translocation (6) | Movement of, until-this-point, virion-encapsidated phage chromosome across the bacterial cell envelope, from the extracellular virion particle into the bacterial cytoplasm |

| Infection (0) | Here defined as a state involving, minimally, the presence of a phage genome within a bacterium’s cytoplasm; the process of “Infection” should not be equated with the process of “Adsorption”, e.g., given the existence of superinfection exclusion |

| Irreversible attachment (5) | Committed interactions between a virion and bacterial surface as ideally (for the phage) leading to genome translocation |

| Phage receptor | Bacterial molecule, such as a protein or polysaccharide, that is displayed on the outside of a bacterium’s cell envelopment and to which a virion displays affinity in the course of attachment (reversible or irreversible) |

| Release (1) | Transition of an intracellularly located virion particle into an extracellularly located virion; the process of becoming a free phage or free virion |

| Reversible attachment (4) | Non-covalent initial interactions between a virion and a bacterial surface; generally followed by either irreversible virion attachment or instead by virion desorption |

| Superinfection exclusion | Process of blockage of phage genome translocation that acts following virion irreversible attachment |

| Target radius (R) | As controls in part the likelihood of encounter (or collision) between particles, with a larger radius resulting in greater likelihoods of collision; it generally is only the bacterium’s radius rather than that of virions as well which is considered |

| Titer (P) | Description of the concentration of free phages within an environment, such as in per mL units |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abedon, S.T. Bacteriophage Adsorption: Likelihood of Virion Encounter with Bacteria and Other Factors Affecting Rates. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 723. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12040723

Abedon ST. Bacteriophage Adsorption: Likelihood of Virion Encounter with Bacteria and Other Factors Affecting Rates. Antibiotics. 2023; 12(4):723. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12040723

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbedon, Stephen Tobias. 2023. "Bacteriophage Adsorption: Likelihood of Virion Encounter with Bacteria and Other Factors Affecting Rates" Antibiotics 12, no. 4: 723. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12040723

APA StyleAbedon, S. T. (2023). Bacteriophage Adsorption: Likelihood of Virion Encounter with Bacteria and Other Factors Affecting Rates. Antibiotics, 12(4), 723. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12040723