Prescribing Antibiotics in Public Primary Care Clinics in Singapore: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Data Source and Study Population

2.2. Diagnosis Categorization and Antibiotic Classifications

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Respiratory Conditions (Presumed To Be Infective) | |||||||

| respiratory tuberculosis unspecified, without mention of bacteriological or histological confirmation | tuberculosis | pneumonia | pneumonia, unspecified | COPD | chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, unspecified | chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | CAP (community acquired pneumonia) |

| asthma-copd overlap syndrome | bronchiectasis | whooping cough, unspecified | |||||

| Respiratory Conditions (Presumed To Be Non-Infective) | |||||||

| acute bronchitis, unspecified | acute upper respiratory infection, unspecified | asthma | asthma, unspecified | influenza with other respiratory manifestations, influenza virus identified | upper respiratory tract infection | URTI (acute upper respiratory infection) | COVID-2019: suspect case |

| URTI | influenza-like illness | acute bronchitis | disorder of respiratory system | respiratory disorder, unspecified | other respiratory conditions | asthma (bronchial) | coronavirus infection, unspecified site |

| pulmonary embolism without mention of acute cor pulmonale | pulmonary embolism | coronavirus infection | respiration disorder | cough | |||

| Skin Conditions (Presumed To Be Infective) | |||||||

| acne, unspecified | abscess | carbuncle of skin and/or subcutaneous tissue | cellulitis | cellulitis, unspecified | burn of unspecified body region, unspecified thickness | disorder of nail | unspecified diabetes mellitus with foot ulcer due to multiple causes |

| furuncle of skin or subcutaneous tissue | nail disorder, unspecified | DM foot | open wound of unspecified body region | ulcer of lower limb, not elsewhere classified | burns | skin infection | open wound |

| diabetic foot ulcer | nail disease | chronic ulcer of lower extremity | acne | FB skin | multiple wounds | cutaneous abscess, furuncle and carbuncle, unspecified | decubitus ulcer and pressure area, unspecified |

| injury | injury, unspecified | superficial foreign body (splinter) of unspecified body region | other injuries | other breast conditions | burn | wound cellulitis | pressure ulcer |

| superficial burn | boil | furuncle | paronychia of left thumb | laceration | dog bite | cat bite | skin abscess |

| folliculitis | foreign body (FB) in soft tissue | mastitis | paronychia of great toe of left foot | paronychia of finger | acute mastitis | paronychia of third toe of right foot | cellulitis of foot, right |

| breast abscess | erysipelas | foot ulcer due to secondary dm | surgical wound breakdown | superficial foreign body | |||

| Skin Conditions (Presumed To Be Non-Infective) | |||||||

| skin disorder | dermatomycosis | disorder of skin and subcutaneous tissue | disorder of skin and subcutaneous tissue, unspecified | flexural atopic dermatitis | fungal infection | nonscarring hair loss, unspecified | other atopic dermatitis |

| other psoriasis | scabies | superficial mycosis, unspecified | unspecified contact dermatitis, unspecified cause | viral warts | contusion | warts | eczema |

| abrasion | pruritus | psoriasis | corn/callus | urticaria | other skin conditions | alopecia | neonatal jaundice |

| corns and callosities | other specified soft tissue disorders, site unspecified | soft tissue disorder | varicose veins of lower extremities without ulcer or inflammation | varicose veins, legs | dermatitis | atopic dermatitis | neonatal jaundice, unspecified |

| contact dermatitis | skin abnormalities | sebaceous cyst | varicose veins of lower extremity | viral wart | tinea pedis | corn | asteatotic eczema |

| lipoma | callus | skin tag | abrasion of heel | callus of hand | squamous cell carcinoma of skin | rash | melanocytic naevi |

| tinea corporis | ingrowing toenail | ingrowing left great toenail | ingrown left big toenail | IGTN (ingrowing toe nail) | ingrowing right great toenail | ingrown nail of great toe | disorder of skin |

| lump in neck | granuloma of skin | neck mass | follow-up examination after surgery for other conditions | atherosclerotic pvd with ulceration | tinea unguium | ganglion cyst | ganglion, site unspecified |

| swelling of left side of face | |||||||

| Genitourinary Conditions (Presumed To Be Infective) | |||||||

| Gonococcal infection of lower genitourinary tract without periurethral or accessory gland abscess | urinary tract infection | urinary tract infection, site not specified | UTI | unspecified sexually transmitted disease | vaginal discharge | balanitis | sexually transmitted disease |

| male genital lesion | UTI (urinary tract infection) | BV (bacterial vaginosis) | cystitis | bacterial vaginosis | chronic prostatitis | other venereal disease | |

| Genitourinary Conditions (Presumed To Be Non-Infective) | |||||||

| Candidiasis | Candidiasis, unspecified | haematuria | unspecified haematuria | disorder of kidney and ureter, unspecified | unspecified condition associated with female genital organs and menstrual cycle | urinary incontinence | unspecified urinary incontinence |

| urinary calculus, unspecified | sexual dysfunction | other male genital disorders | other gynaecological conditions | dysmenorrhoea | menorrhagia | calculus, urinary tract | other urinary disorders |

| abnormal uterine and vaginal bleeding, unspecified | calculus, urinary | disorder of kidney and ureter | genital herpes (recurrent) | undescended testicle, unspecified laterality, unspecified site | unspecified sexual dysfunction, not caused by organic disorder or disease | disorder of menstrual bleeding | bph associated with nocturia |

| BPH (benign prostatic hyperplasia) | phimosis of penis | congenital anomaly of urinary system | congenital anomaly of female genital system | uterine fibroid | PCOS (polycystic ovarian syndrome) | calculus of ureter | Candidiasis of vagina |

| Candidiasis of vulva and vagina | vulvovaginal Candidiasis | prolapse of female pelvic organs | menopause | urinary disorder | urine abnormality | benign essential microscopic haematuria | urolithiasis |

| albuminuria | bladder disorder | fibroid | post-menopausal atrophic vaginitis | atrophic vaginitis | disorder of male genital organ | disorder of male genital organs, unspecified | disorder of female genital organs |

| female genital disorder | renal stone | AKI (acute kidney injury) | congenital malformation of urinary system, unspecified | ||||

| Gastrointestinal Conditions (Presumed To Be Infective) | |||||||

| anorectal abscess | other gastroenteritis and colitis of unspecified origin | peptic ulcer, unspecified as acute or chronic, without haemorrhage or perforation | peptic ulcer disease | acute appendicitis unspecified | perineal abscess | perianal abscess | |

| Gastrointestinal Conditions (Presumed To Be Non-Infective) | |||||||

| GORD (gastro oesophageal reflux disease) | gastroesophageal reflux disease | gastroenteritis, acute | anal fissure, unspecified | anal fistula | dysphagia | functional dyspepsia | gastroduodenitis, unspecified |

| gastro-oesophageal reflux disease without oesophagitis | haemorrhoids | irritable bowel syndrome without diarrhoea | noninfectious gastroenteritis and colitis | unspecified abdominal hernia without obstruction or gangrene | unspecified haemorrhoids without complication | incontinence/enuresis | constipation |

| gerd | piles | gastritis | other git conditions | dyspepsia | disease of intestine, unspecified | foreign body in alimentary tract, part unspecified | other and unspecified abdominal pain |

| abdominal pain | dyspepsia and disorder of function of stomach | IBS | vomiting of pregnancy, unspecified | disorder of intestine | anal fissure | gastroduodenitis | abdominal hernia |

| irritable bowel syndrome | gastroenteritis | piles (haemorrhoids) | diarrhoea | intestinal disorder | GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease) | foreign body in alimentary tract | perianal fistula |

| intestinal bleeding | inguinal hernia | enteritis,ge | enteritis | ||||

| Infectious Disease Conditions (Presumed To Be Infective) | |||||||

| infectious disease | other and unspecified infectious diseases | other infections (non-notifiable) | |||||

| Infectious Disease Conditions (Presumed To Be Non-Infective) | |||||||

| dengue fever [classical dengue] | enteroviral vesicular stomatitis with exanthem | varicella without complication | zoster without complication | herpes zoster | dengue | chickenpox | herpes zoster without complication |

| unspecified arthropod-borne viral fever | varicella uncomplicated | viral illness | fever | hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD) | parasite infection | viral hepatitis | |

| Dental Conditions | |||||||

| necrosis of pulp | reversible pulpitis | irreversible pulpitis | periodontitis | dental caries | gingivitis | defective dental restoration | retained dental root |

| combined periodontal and endodontic lesion | caries | tooth abrasion | arrested dental caries | fracture of crown, enamel, and dentin of tooth without pulp exposure | dentine hypersensitivity | fracture of crown, enamel, and dentin of tooth with pulp exposure | abrasion of teeth |

| fracture of dental restoration | gingival hyperplasia | fracture of tooth | teeth problem | gum disease | disorder of teeth and supporting structures | disorder of teeth and supporting structures, unspecified | other and unspecified lesions of oral mucosa |

| teeth & supporting structure disease | disease of salivary gland, unspecified | disorder of oral soft tissue | disorder of salivary gland | oral soft tissue disease | abscess of buccal space of mouth | impacted third molar tooth | cracked tooth |

| impacted teeth with abnormal position | oral infection | horizontal fracture of tooth | vertical fracture of root of tooth | peri-implantitis, dental | fascial space infection of mouth | infection of buccal space | fracture of root of tooth |

| periodontal abscess | pericoronitis | symptomatic periapical periodontitis | alveolar osteitis | symptomatic irreversible pulpitis | chronic apical abscess | pulpal necrosis | apical abscess |

| ENT Conditions (Presumed To Be Infective) | |||||||

| acute tonsillitis | disorder of ear | disorder of ear, unspecified | otitis externa, unspecified | otitis media, unspecified | otitis externa | otitis media | acute sinusitis |

| chronic sinusitis | disorder of nose | acute infective otitis externa | infective otitis externa | external otitis of left ear | sinus disorder | sinusitis | cervical lymphadenopathy |

| ENT Conditions (Presumed To Be Non-Infective) | |||||||

| allergic rhinitis, unspecified | epistaxis | allergic rhinitis | chronic mucoid otitis media | chronic secretory otitis media | foreign body in ear | foreign body in nostril | impacted cerumen |

| ear wax | other ear conditions | FB ear | hearing loss, unspecified | hearing loss | mumps without complication | problems with hearing | foreign body in nose |

| MUMPS | |||||||

| Eye Conditions (Presumed To Be Infective) | |||||||

| FB eye | conjunctivitis | chalazion | conjunctivitis, unspecified | eyelid disorder | disorder of eyelid, unspecified | foreign body on external eye, part unspecified | foreign body in external eye |

| blepharitis of eyelid of left eye | external hordeolum | infected eye lid | hordeolum | blepharitis | stye external | stye | periorbital cellulitis |

| Eye Conditions (Presumed To Be Non-Infective) | |||||||

| disorder of eye | disorder of eye and adnexa, unspecified | disorder of refraction, unspecified | glaucoma, unspecified | refractive vision | cataracts | other eye conditions | cataract, unspecified |

| disorder of eyelid | congenital anomaly of eye | eye disorder | cataract | dry eyes | glaucoma | eye discomfort | disorder of refraction and accommodation |

| blindness of one eye | conjunctival haemorrhage | H/O subconjunctival haemorrhage | vitreous haemorrhage of left eye | congenital malformation of eye, unspecified | |||

| Unspecified | |||||||

| Impaired glucose regulation | Bursitis | Encounter for education | Acquired absence of leg at or below knee | Generalised osteoarthritis | Routine child health examination | Osteoporosis-fracture-vertebral | Chronic renal failure |

| Impaired glucose regulation without complication | Acquired absence of foot | Status post below-knee amputation | Administrative encounter | Gynaecological examination (general)(routine) | Routine postpartum follow-up | Stroke (infarct) | Chronic renal insufficiency, stage iii (moderate) |

| Impaired glucose tolerance | Peripheral venous insufficiency | Medical care complication | Allergy, unspecified | Headache | Schizophrenia, unspecified | TIA | CKD stage 2 (EGFR 60–89) |

| Personal history of long-term (current) use of other medicaments, insulin | Arthralgia | De quervain’s tenosynovitis | Anaemia, unspecified | Heart disease, unspecified | Severe depressive episode without psychotic symptoms, not specified as arising in the postnatal period | Hypertension (diet only) | Osteopenia |

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus without complication | Venous embolism and thrombosis | Frozen shoulder | Arthropathy | Hereditary and idiopathic neuropathy, unspecified | Special screening | Epilepsy | Achilles tendinitis |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | Vomiting as reason for care in pregnancy | Disorder of gallbladder | Myalgia, site unspecified | Hyperlipidaemia | Special screening examination, unspecified | Sprain/strain | Cerebral palsy |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus without complication | Complication related to pregnancy | Congenital anomaly of musculoskeletal system | Arthrosis, unspecified, site unspecified | Hyperlipidaemia, unspecified | Sprain, strain | Well women clinic | Arrhythmias |

| Unspecified diabetes mellitus with background retinopathy | Unwanted pregnancy | Back pain | Atherosclerosis of arteries of extremities | Hyperplasia of prostate | Stroke | Hyperlipidemia (diet only) | Thyroiditis |

| Unspecified diabetes mellitus with hypoglycaemia | Cobalamin deficiency | Dyslipidaemia | Atrial fibrillation | Hypertension | Stroke, not specified as haemorrhage or infarction | Non–DM nephropathy–incipient | Gall bladder disease |

| Impaired fasting glucose(IFG) | Folic acid deficiency | Itch | Atrial fibrillation and flutter | Hypothyroidism, unspecified | Supervision of normal pregnancy, unspecified | Other screening/growth monitoring. Questionnaires | Adverse effect, medication, chemical |

| DM retinopathy | Lateral Epicondylitis (Tennis Elbow) | Low Back Pain | Back Ache | IHD (ischaemic heart disease) | Tendency To Fall, Nec | Insomnia | Iron Deficiency |

| Impaired Glucose Tolerance(IGT) | Synovitis and tenosynovitis | TIA (transient ischaemic attack) | Bell’s palsy | Ill-defined condition | Thalassaemia, unspecified | Med exam/investigations | Menopausal disorders |

| Dm neuropathy | Tendinitis | Mammogram abnormal | Benign neoplasm of unspecified site | Inappropriate diet and eating habits | Thyrotoxicosis, unspecified | Schizophrenia | Family planning |

| DM nephropathy - ESRF on dialysis | Transient ischemic attack | Disease of circulatory system | Breast lump | Isolated proteinuria | Tobacco use, current | Osteoporosis | Pes planus |

| DM type i on medication | Fatty liver | Osa (obstructive sleep apnoea) | Cardiac arrhythmia, unspecified | Liver disease, unspecified | Transient cerebral ischaemic attack, unspecified | Antenatal care | Down’s syndrome |

| DM type ii on medication | Neck ache | Palpitations | Carpal tunnel syndrome | Loss of consciousness of unspecified duration | Trigeminal neuralgia | Acute ischemic heart disease | Other renal disorders |

| DM nephropathy - overt | Benign neoplasm | Metastatic malignant neoplasm | Other cvs conditions | Malignant neoplasm | Unspecified adverse effect of drug or medicament | Health education | Unspecified mental retardation without mention of impairment of behaviour |

| DM nephropathy - incipient | Well adult exam | Thyroid nodule | Chest pain, unspecified | Malignant neoplasm without specification of site | Unspecified dementia | Malignant neoplasms | Adjustment disorders |

| DM type ii (diet only) | Fracture neck of femur | Depressive illness | Chronic ischaemic heart disease, unspecified | Menopausal and perimenopausal disorder, unspecified | Unspecified disorder of bone density and structure, site unspecified | Anemia (except thal.) | Bipolar affective disorder, unspecified |

| Current use of insulin | Abnormal bone density screening | Stroke, haemorrhagic | Chronic nephritic syndrome, unspecified | Menopausal and postmenopausal disorder | Unspecified dorsalgia, site unspecified | Code not in dimension | Unspecified complication of procedure |

| Diabetes mellitus with incipient diabetic nephropathy | Idiopathic peripheral neuropathy | Prenatal consult | Chronic liver disease | Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of alcohol, acute intoxication | Unspecified lump in breast | Travel clinic | Contact with and exposure to other communicable diseases |

| Diabetes mellitus with retinopathy | Benign neoplastic disease | Chronic glomerulonephritis | Condition originating in the perinatal period, unspecified | Migraine, unspecified | Unspecified mental disorder due to brain damage and dysfunction and to physical disease | Stroke (haemorrhage) | Need for immunisation against unspecified combinations of infectious diseases |

| Impaired fasting glucose | Parkinson disease | Sprain and strain | Congenital malformation of heart, unspecified | Mild cognitive disorder | Unspecified nonorganic psychosis | Dementia | Radial styloid tenosynovitis [de quervain] |

| Hypoglycaemia | Dietary counselling and surveillance | Optional surgery | Congenital malformation of musculoskeletal system, unspecified | Neurotic disorder, unspecified | Unspecified osteoporosis, site unspecified | Depression (others) | Other and unspecified abnormalities of gait and mobility |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus with hyperosmolarity with coma | Non-compliance with treatment | Encounter for postnatal visit | Congestive heart failure | Nutritional deficiency, unspecified | Unspecified synovitis and tenosynovitis, site unspecified | Non – dm nephropathy – overt | Unspecified harmful use of non-dependence producing substance |

| Diabetes mellitus, type ii | Cognitive dysfunction | Female infertility | Arthralgia & myalgia | Obesity | Chronic ischemic heart disease | Parkinsonism | Examination for adolescent development state |

| Diabetes mellitus | Trigger finger | Complication of the puerperium, postpartum | Contusion of unspecified body region | Obesity due to excess calories | Thyrotoxicosis | Migraine | Other problems related to housing and economic circumstances |

| Diabetic kidney disease | Mood disorder | Engorgement of breasts associated with childbirth, delivered | Counselling, unspecified | Obesity, unspecified | Backache | Preventive measures/immunisation child | Other specified postprocedural states;previously initiated endodontic therapy completed |

| IFG (impaired fasting glucose) | Hyperthyroidism | Subfertility of couple | Delayed milestone | Osteoarthritis | Anxiety | Headache, not specified | Other specified prophylactic measures |

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus | Thalassaemia | Mood and affect disturbance | Depressive episode, unspecified, not specified as arising in the postnatal period | Other amnesia | Benign neoplasms | Drp | Persistent delusional disorder, unspecified |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus with hyperosmolar coma | Allergic drug reaction | Injured in road traffic accident | Disease of blood and blood-forming organs, unspecified | Other and unspecified disorders of breast associated with childbirth, without mention of attachment difficulty | Head injury | Hernia | Pregnancy-related condition, unspecified |

| Hypoglycaemia associated with diabetes | Elective surgical procedure | Gad (generalised anxiety disorder) | Disease of gallbladder, unspecified | Other and unspecified disorders of circulatory system | Ccf | Follow-up exam. | Cerebral palsy, unspecified |

| Diabetic retinopathy | Disorder of brain | Normal psychiatric assessment | Dislocation, sprain and strain of unspecified body region | Other examinations for administrative purposes | Spinal disorder | Nephritis (eg glomerulonephritis) | Cognitive impairment |

| DM (diabetes mellitus) | Major depression | Well child check | Disorder of brain, unspecified | Other general symptoms and signs | Psychosis | Other cns conditions | Postoperative follow-up |

| Diabetic neuropathy | Memory impairment | Encounter for examination for adolescent development state | Disorder of heart | Other specified counselling | Hyperlipidemia on medication | Rheumatoid arthritis | Myalgia |

| Long term current use of insulin | Stage 4 chronic kidney disease | Orthostatic hypotension | Disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep [insomnias] | Other specified disorders of breast | Stroke (not specified) | Nephritis, nephropathy, unspecified | Delayed developmental milestones |

| T2DM (type 2 diabetes mellitus) | Persistent delusional disorder | Asymptomatic human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection status | Dizziness and giddiness | Overweight | Thalassemia | Hypertension on medication | General counselling and advice for contraceptive management |

| IGT (impaired glucose tolerance) | Smoker | Venous insufficiency (chronic) (peripheral) | Down’s syndrome, unspecified | Parkinson’s disease | Other deformities of ankle and foot | BPH | Closed fracture |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus with complications | Ischemic cerebrovascular accident (cva) | Screening for condition | Elevated blood pressure reading without diagnosis of hypertension | Peripheral vascular disease | Pvd | Congenital heart anomaly | Vertigo |

| Complication of procedure | Concussion | Disorder of endocrine system | Elevated blood-pressure reading, without diagnosis of hypertension | Peripheral vascular disease, unspecified | Nutritional def. | Depression (major) | Fall |

| Bipolar disorder | Deep vein thrombosis | Nutritional deficiency disorder | Embolism and thrombosis of unspecified vein | Personal history of noncompliance with medical treatment and regimen | Other blood disorders | Complication of medical care | Adverse effect of drug or medicament |

| Heart failure | Anxiety state | Erroneous encounter--disregard | Encounter for follow-up in outpatient clinic | Personal history of other mental and behavioural disorders | Glomerulonephritis | Basic health screen | ESRF (end stage renal failure) |

| Inflammatory arthropathy | Strain of knee | Anaemia | Endocrine disorder, unspecified | Plantar fascial fibromatosis | Other msk conditions | Disorder of synovium, tendon & bursa | carrier of viral hepatitis b |

| Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) | Dysfunction, psychosexual | Chronic ischaemic heart disease | Epilepsy, unspecified, without mention of intractable epilepsy | Plantar fasciitis | Giddiness, not specified | Other endocrine diseases | unspecified viral hepatitis without hepatic coma |

| End stage chronic kidney disease | Peripheral neuropathy | Allergy | Essential (primary) hypertension | Polyarthrosis, unspecified | Fractures | Drug/alcohol abuse | Hep B carrier follow-up |

| Congenital abnormality | Lipid disorder | Disorder of breast | Fatty (change of) liver, not elsewhere classified | Polyneuropathy, unspecified | Follow-up post surg | Need for immunisation against influenza | Hepatitis B carrier |

| Psoriatic arthropathy | Follow up | Disorder of cellular component of blood | Female infertility, unspecified | Problems related to unwanted pregnancy | Other psychiatric conditions | Encounter for gynecological examination | Hepatitis B infection |

| Disorder of thyroid | Limb ischaemia | Chest pain | Follow-up examination after unspecified treatment for other conditions | Procedure for purposes other than remedying health state, unspecified | Bunion/hallux valgus | Chronic kidney disease, unspecified | Disappearance and death of family member |

| CKD (chronic kidney disease) | Nonrheumatic aortic valve stenosis | Gout | Fracture of unspecified body region, closed | Prophylactic measure, unspecified | Hypothyroidism | ckd stage 3 or 4 (EGFR 15–59) | lack of physical exercise |

| Lymphadenopathy | Alcohol abuse | Gout, unspecified, site unspecified | General counselling and advice on contraception | Proteinuria | Graves’ disease | CKD stage 5/ESRF (EGFR < 15) | complication of surgical and medical care, unspecified |

| Food poisoning | Hypokalaemia | Acquired absence of foot and ankle | General medical examination | Rheumatoid arthritis, unspecified, site unspecified | Chest pain nos | Renal failure, chronic | Thalamic haemorrhage |

| Postural hypotension | Acquired absence of leg above knee | Generalised anxiety disorder | Risk for falls | Bipolar disorders | CKD stage 4 (egfr 15–29) | ||

| B | SE | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Gender (Female) | 0.111 | 0.016 | <0.001 | 1.12 | 1.08 | 1.15 |

| Race * | <0.001 | |||||

| Indian | −0.044 | 0.027 | 0.104 | 0.957 | 0.908 | 1.01 |

| Malay | −0.085 | 0.024 | <0.001 | 0.919 | 0.877 | 0.963 |

| Others | 0.101 | 0.032 | 0.002 | 1.11 | 1.04 | 1.18 |

| Age | 0.005 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 1.005 | 1.004 | 1.006 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.295 | 0.020 | <0.001 | 1.34 | 1.29 | 1.40 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0.272 | 0.022 | <0.001 | 1.31 | 1.26 | 1.37 |

| Physician Training (Locally trained) | −0.001 | 0.018 | 0.972 | 0.999 | 0.965 | 1.04 |

| Years of physician experience | −0.007 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.993 | 0.991 | 0.995 |

| Family physician | 0.150 | 0.018 | <0.001 | 1.16 | 1.12 | 1.20 |

| Place of practice + | <0.001 | |||||

| Clinic A | 0.166 | 0.027 | <0.001 | 1.18 | 1.12 | 1.25 |

| Clinic B | 0.087 | 0.027 | 0.001 | 1.09 | 1.04 | 1.15 |

| Clinic C | −0.148 | 0.029 | <0.001 | 0.862 | 0.815 | 0.912 |

| Clinic D | 0.028 | 0.029 | 0.333 | 1.03 | 0.972 | 1.09 |

| Constant | −2.46 | 0.037 | <0.001 | 0.085 | ||

| B | SE | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Gender (Male) | 0.233 | 0.032 | <0.001 | 1.26 | 1.19 | 1.35 |

| Race * | 0.243 | |||||

| Indian | −0.046 | 0.051 | 0.359 | 0.955 | 0.864 | 1.05 |

| Malay | −0.064 | 0.046 | 0.159 | 0.938 | 0.858 | 1.03 |

| Others | 0.059 | 0.059 | 0.318 | 1.06 | 0.945 | 1.19 |

| Age | 0.007 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 1.007 | 1.005 | 1.009 |

| Diabetes mellitus | −0.067 | 0.041 | 0.101 | 0.935 | 0.863 | 1.01 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0.018 | 0.043 | 0.672 | 1.02 | 0.936 | 1.11 |

| Training (Locally trained) | 0.197 | 0.032 | <0.001 | 1.22 | 1.14 | 1.30 |

| Years of physician experience | 0.008 | 0.002 | <0.001 | 1.008 | 1.005 | 1.011 |

| Family physician | 0.155 | 0.034 | <0.001 | 1.17 | 1.09 | 1.25 |

| Place of practice + | <0.001 | |||||

| Clinic A | 0.104 | 0.049 | 0.033 | 1.11 | 1.01 | 1.22 |

| Clinic B | −0.279 | 0.051 | <0.001 | 0.757 | 0.684 | 0.837 |

| Clinic C | 0.101 | 0.048 | 0.037 | 1.11 | 1.01 | 1.22 |

| Clinic D | −0.379 | 0.053 | <0.001 | 0.684 | 0.616 | 0.760 |

| Visit diagnoses ^ | <0.001 | |||||

| Dental | −0.116 | 0.194 | 0.551 | 0.891 | 0.609 | 1.30 |

| ENT | 1.36 | 0.088 | <0.001 | 3.91 | 3.20 | 4.64 |

| Eye | 0.225 | 0.195 | 0.249 | 1.25 | 0.854 | 1.83 |

| Gastrointestinal | 3.35 | 0.086 | <0.001 | 28.5 | 24.1 | 33.8 |

| Genitourinary | 2.32 | 0.058 | <0.001 | 10.2 | 9.07 | 11.4 |

| Infectious diseases | 1.06 | 0.394 | 0.007 | 2.88 | 1.33 | 6.23 |

| Multiple diagnoses | 1.82 | 0.103 | <0.001 | 6.18 | 5.05 | 7.56 |

| Respiratory | 2.47 | 0.058 | <0.001 | 11.9 | 10.6 | 13.3 |

| Undefined | 1.59 | 0.064 | <0.001 | 4.88 | 4.31 | 5.52 |

| Constant | −4.58 | 0.086 | <0.001 | 0.010 | ||

| Topical Antibiotics | 2018, n = 14,558 | 2019, n = 14,445 | 2020, n = 14,359 | 2021, n = 14,809 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin related diagnoses | 9436 (64.8%) | 9349 (64.7%) | 9265 (64.5%) | 8875 (59.9%) |

| Non-skin related diagnoses | 5122 (35.2%) | 5096 (35.3%) | 5094 (35.5%) | 5934 (40.1%) |

| B | SE | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Gender (Female) | 0.172 | 0.018 | <0.001 | 1.19 | 1.15 | 1.23 |

| Race * | <0.001 | |||||

| Indian | −0.171 | 0.031 | <0.001 | 0.843 | 0.793 | 0.897 |

| Malay | −0.369 | 0.030 | <0.001 | 0.691 | 0.652 | 0.733 |

| Others | −0.229 | 0.042 | <0.001 | 0.795 | 0.732 | 0.864 |

| Age | 0.013 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 1.013 | 1.012 | 1.015 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.405 | 0.021 | <0.001 | 1.50 | 1.44 | 1.56 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0.211 | 0.023 | <0.001 | 1.23 | 1.18 | 1.29 |

| Training (Locally trained) | 0.066 | 0.019 | <0.001 | 1.07 | 1.03 | 1.11 |

| Years of physician experience | −0.002 | 0.001 | 0.101 | 0.998 | 0.996 | 1.000 |

| Family physician | 0.094 | 0.020 | <0.001 | 1.10 | 1.06 | 1.14 |

| Place of practice + | <0.001 | |||||

| Clinic A | 0.343 | 0.033 | <0.001 | 1.41 | 1.32 | 1.50 |

| Clinic B | 0.296 | 0.032 | <0.001 | 1.35 | 1.26 | 1.43 |

| Clinic C | −0.041 | 0.033 | 0.213 | 0.960 | 0.899 | 1.02 |

| Clinic D | 0.227 | 0.033 | <0.001 | 1.26 | 1.18 | 1.34 |

| Constant | −1.79 | 0.043 | <0.001 | 0.166 | ||

| B | SE | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Gender (Female) | 0.121 | 0.021 | <0.001 | 1.13 | 1.08 | 1.18 |

| Race * | <0.001 | |||||

| Indian | −0.082 | 0.034 | 0.017 | 0.921 | 0.861 | 0.985 |

| Malay | −0.128 | 0.030 | <0.001 | 0.880 | 0.829 | 0.934 |

| Others | −0.117 | 0.043 | 0.007 | 0.890 | 0.818 | 0.968 |

| Age | −0.006 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.994 | 0.993 | 0.995 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.053 | 0.027 | 0.046 | 1.06 | 1.001 | 1.11 |

| Chronic kidney disease | −0.103 | 0.029 | <0.001 | 0.902 | 0.852 | 0.954 |

| Training (Locally trained) | −0.167 | 0.023 | <0.001 | 0.846 | 0.809 | 0.885 |

| Years of physician experience | 0.017 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 1.017 | 1.015 | 1.019 |

| Family physician | 0.148 | 0.023 | <0.001 | 1.16 | 1.11 | 1.21 |

| Place of practice + | <0.001 | |||||

| Clinic A | 0.003 | 0.036 | 0.931 | 1.00 | 0.934 | 1.08 |

| Clinic B | −0.021 | 0.034 | 0.531 | 0.979 | 0.916 | 1.05 |

| Clinic C | 0.444 | 0.035 | <0.001 | 1.56 | 1.45 | 1.67 |

| Clinic D | 0.077 | 0.036 | 0.032 | 1.08 | 1.01 | 1.16 |

| Constant | −0.604 | 0.046 | <0.001 | 0.547 | ||

References

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Agri-Food & Veterinary Authority of Singapore (AVA), Ministry of Health (MOH), Singapore, National Environment Agency (NEA), National Water Agency (PUB). National Strategic Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sg/resources-statistics/reports/national-strategic-action-plan-on-antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Hsu, L.Y.; Kwa, A.L.; Lye, D.C.; Chlebicki, M.P.; Tan, T.Y.; Ling, M.L.; Wong, S.Y.; Goh, L.G. Reducing antimicrobial resistance through appropriate antibiotic usage in Singapore. Singap. Med. J. 2008, 49, 749–755. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, A.Q.; Kwa, A.L.H.; Tan, T.Y.; Chlebicki, M.P.; Tan, T.Y.; Ling, M.L.; Wong, S.Y.; Goh, L.G. Ten-year narrative review on antimicrobial resistance in Singapore. Singap. Med. J. 2019, 60, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, I.; Hayward, A.C. SACAR Surveillance Subgroup. Antibacterial prescribing in primary care. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007, 60, I43–I47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Singapore. White Paper on Healthier SG; Ministry of Health: Singapore, 2022.

- Kitano, T.; Brown, K.A.; Daneman, N.; MacFadden, D.R.; Langford, B.J.; Leung, V.; So, M.; Leung, E.; Burrows, L.; Manuel, D.; et al. The impact of COVID-19 on outpatient antibiotic prescriptions in ontario, canada; an interrupted time series analysis. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, ofab533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.M.; Lovegrove, M.C.; Shehab, N.; Tsay, S.; Budnitz, D.S.; Geller, A.I.; Lind, J.N.; Roberts, R.M.; Hicks, L.A.; Kabbani, S. Trends in us outpatient antibiotic prescriptions during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e652–e660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcolm, W.; Seaton, R.A.; Haddock, G.; Baxter, L.; Thirlwell, S.; Russell, P.; Cooper, L.; Thomson, A.; Sneddon, J. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on community antibiotic prescribing in Scotland. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2020, 2, dlaa105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.M.; Tan, S.H.; Heng, S.T.; Tay, H.L.; Yap, M.Y.; Chua, B.H.; Teng, C.B.; Lye, D.C.; Lee, T.H. Effects of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on antimicrobial prevalence and prescribing in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2021, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.B.; Cook, M.J.; Logan, P.; Rozanova, L.; Wilder-Smith, A. Singapore’s pandemic preparedness: An overview of the first wave of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. AWaRe Classification; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Hildon, Z.J.L.; Lye, D.C.B.; Straughan, P.T.; Chow, A. The associations between poor antibiotic and antimicrobial resistance knowledge and inappropriate antibiotic use in the general population are modified by age. Antibiotics 2021, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, R.; Nellums, L.B. Antibiotic prescribing in general practice during COVID-19. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, e144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Pol, A.C.; Boeijen, J.A.; Venekamp, R.P.; Platteel, T.; Damoiseaux, R.A.; Kortekaas, M.F.; van der Velden, A.W. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on antibiotic prescribing for common infections in the netherlands: A primary care-based observational cohort study. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.H.M.; Pan, D.S.T.; Huang, J.H.; Chen, M.I.-C.; Chong, J.W.C.; Goh, E.H.; Jiang, L.; Leo, Y.S.; Lee, T.H.; Wong, C.S.; et al. Results from a patient-based health education intervention in reducing antibiotic use for acute upper respiratory tract infections in the private sector primary care setting in Singapore. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e02257-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNicholas, M.; Hooper, G. Effects of patient education to reduce antibiotic prescribing rates for upper respiratory infections in primary care. Fam. Pract. 2022, 39, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinggera, D.; Kerschbaumer, J.; Grassner, L.; Demetz, M.; Hartmann, S.; Thomé, C. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on patient presentation and perception to a neurosurgical outpatient clinic. World Neurosurg. 2021, 149, e274–e280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soo, R.J.J.; Chiew, C.J.; Ma, S.; Pung, R.; Lee, V. Decreased influenza incidence under COVID-19 control measures, singapore. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1933–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teo, J. All 20 Polyclinics and Some GPs Can Now Perform Coronavirus Swab Test; The Straits Times: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Abu Baker, J. PCR Tests to be Reserved for Those Who Are Unwell; more ART kits to be distributed; CAN: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Foo, C.D.; Verma, M.; Tan, S.M.; Haldane, V.; Reyes, K.A.; Garcia, F.; Canila, C.; Orano, J.; Ballesteros, A.J.; Marthias, T.; et al. COVID-19 public health and social measures: A comprehensive picture of six Asian countries. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e009863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, D.S.T.; Huang, J.H.; Lee, M.H.M.; Yu, Y.; Chen, M.I.-C.; Goh, E.H.; Jiang, L.; Chong, J.W.C.; Leo, Y.S.; Lee, T.H.; et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards antibiotic use in upper respiratory tract infections among patients seeking primary health care in Singapore. BMC Fam. Pract. 2016, 17, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shively, N.R.; Buehrle, D.J.; Clancy, C.J.; Decker, B.K. Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in primary care clinics within a veterans affairs health care system. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e00337-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotwani, A.; Wattal, C.; Katewa, S.; Joshi, P.C.; Holloway, K. Factors influencing primary care physicians to prescribe antibiotics in Delhi India. Fam. Pract. 2010, 27, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health Singapore. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Use of Antibiotics in Adults. Ministry of Health Clinical Practice Guidelines 1/2006; Ministry of Health Singapore, Academy of Medicine Singapore, Chapter of Infectious Disease Physicians College of Physicians: Singapore, 2006.

- Palin, V.; Mölter, A.; Belmonte, M.; Ashcroft, D.M.; White, A.; Welfare, W.; Van Staa, T. Antibiotic prescribing for common infections in UK general practice: Variability and drivers. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 2440–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasziou, P.; Dartnell, J.; Biezen, R.; Morgan, M.; Manski-Nankervis, J.A. Antibiotic stewardship: A review of successful, evidence-based primary care strategies. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2022, 51, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, T.R.; Efthimiou, J.; Dréno, B. Systematic review of antibiotic resistance in acne: An increasing topical and oral threat. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, e23–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, D.J.; Hicks, L.A.; Pavia, A.T.; Hersh, A.L. Antibiotic prescribing for adults in ambulatory care in the USA, 2007–2009. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Antimicrobial Resistance Control Committee (NARCC) Secretariat, Antimicrobial Resistance Coordinating Office (AMRCO). Surveillance of Antimicrobial Utilisation in Polyclinics, 2017–2021; Ministry of Health Singapore: Singapore, 2022.

- Khoo, H.S.; Lim, Y.W.; Vrijhoef, H.J. Primary healthcare system and practice characteristics in Singapore. Asia Pac. Fam. Med. 2014, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | 2018, n = 44,047 (5.11%) 1 | 2019, n = 42,631 (4.75%) | 2020, n = 28,977 (3.99%) | 2021, n = 26,289 (3.38%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Prescription Rate % | n (%) | Prescription Rate % | n (%) | Prescription Rate % | n (%) | Prescription Rate % | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 52 (17) | - | 52 (17) | - | 53 (18) | - | 53 (18) | - |

| Age group | ||||||||

| 22–44 | 15,107 (34.3%) | 7.02% | 14,472 (34.0%) | 6.54% | 9790 (33.8%) | 6.07% | 8759 (33.3%) | 4.67% |

| 45–54 | 7586 (17.2%) | 5.70% | 7072 (16.6%) | 5.09% | 4711 (16.3%) | 4.44% | 4209 (16.0%) | 3.53% |

| 55–64 | 9598 (21.8%) | 4.98% | 9244 (21.7%) | 4.64% | 6244 (21.6%) | 3.73% | 5452 (20.7%) | 2.97% |

| 65–74 | 7459 (16.9%) | 4.47% | 7687 (18.0%) | 4.22% | 5315 (18.3%) | 3.24% | 4919 (18.7%) | 2.66% |

| >=75 | 4297 (9.76%) | 4.29% | 4156 (9.75%) | 3.94% | 2917 (10.1%) | 3.19% | 2950 (11.2%) | 2.84% |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 20,283 (46.0%) | 5.17% | 19,639 (46.1%) | 4.78% | 13,654 (47.1%) | 3.99% | 11,794 (44.9%) | 3.09% |

| Female | 23,764 (54.0%) | 5.71% | 22,992 (53.9%) | 5.33% | 15,323 (52.9%) | 4.40% | 14,495 (55.1%) | 3.65% |

| Race | ||||||||

| Chinese | 28,910 (65.6%) | 4.78% | 28,080 (65.9%) | 4.44% | 18,920 (65.3%) | 3.72% | 17,422 (66.3%) | 3.21% |

| Malay | 7306 (16.6%) | 5.58% | 6840 (16.0%) | 5.09% | 4686 (16.2%) | 4.35% | 3995 (15.2%) | 3.89% |

| Indian | 4697 (10.7%) | 6.10% | 4685 (11.0%) | 5.98% | 3313 (11.4%) | 4.91% | 2968 (11.3%) | 4.15% |

| Others | 3134 (7.12%) | 6.46% | 3026 (7.10%) | 5.97% | 2058 (7.10%) | 3.77% | 1904 (7.24%) | 3.87% |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 11,835 (26.9%) | - | 11,632 (27.3%) | - | 8536 (29.5%) | - | 7329 (27.9%) | - |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 10,943 (24.8%) | - | 10,461 (24.5%) | - | 7538 (26.0%) | - | 6537 (24.9%) | - |

| Primary care clinic, n (%) | ||||||||

| Clinic A | 9917 (22.5%) | 5.70% | 8513 (20.0%) | 4.82% | 5819 (20.1%) | 4% | 5100 (19.4%) | 3.24% |

| Clinic B | 11,379 (25.8%) | 4.91% | 10,174 (23.9%) | 4.42% | 6594 (22.8%) | 3.57% | 5718 (21.8%) | 3.10% |

| Clinic C | 9185 (20.9%) | 5.93% | 8873 (20.8%) | 5.45% | 5733 (19.8%) | 4.43% | 5175 (19.7%) | 3.81% |

| Clinic D | 7262 (16.5%) | 3.82% | 7604 (17.8%) | 3.93% | 5540 (19.1%) | 3.55% | 5060 (19.3%) | 3.05% |

| Clinic E | 6304 (14.3%) | 5.69% | 7467 (17.5%) | 5.60% | 5291 (18.3%) | 4.74% | 4629 (17.6%) | 3.96% |

| Clinic F | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | - | 607 (2.31%) | 3.26% |

| Prescriber | ||||||||

| Family physician | 22,887 (52.0%) | - | 25,415 (59.6%) | - | 17,227 (59.5%) | - | 17,212 (65.5%) | - |

| Locum | 4801 (10.9%) | - | 4037 (9.47%) | - | 2209 (7.62%) | - | 1861 (7.08%) | - |

| Medical officer | 4652 (10.6%) | - | 3356 (7.87%) | - | 2902 (10.0%) | - | 1761 (6.70%) | - |

| Resident physician | 11,707 (26.6%) | - | 9823 (23.0%) | - | 6639 (22.9%) | - | 5455 (20.8%) | - |

| Training location | ||||||||

| Local | 15,597 (35.4%) | - | 15,861 (37.2%) | - | 10,554 (36.4%) | - | 10,452 (39.8%) | - |

| Overseas | 28,450 (64.6%) | - | 26,770 (62.8%) | - | 18,423 (63.6%) | - | 15,837 (60.2%) | - |

| Conditions | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | % Visits Prescribed Antibiotics | n (%) | % Visits Prescribed Antibiotics | n (%) | % Visits Prescribed Antibiotics | n (%) | % Visits Prescribed Antibiotics | n (%) | % Visits Prescribed Antibiotics | |

| Dental | 826 (1.88%) | 17.7 | 891 (2.09%) | 17.2 | 782 (2.70%) | 16.9 | 897 (3.41%) | 19.4 | 3396 (2.39%) | 17.8 |

| ENT (ear, nose, and throat) | 1710 (3.88%) | 7.74 | 1531 (3.59%) | 6.80 | 1535 (5.30%) | 7.51 | 1322 (5.03%) | 8.78 | 6098 (4.30%) | 7.61 |

| Eye | 770 (1.75%) | 2.21 | 729 (1.71%) | 2.19 | 604 (2.08%) | 2.34 | 560 (2.13%) | 2.31 | 2663 (1.88%) | 2.25 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1019 (2.31%) | 1.06 | 952 (2.23%) | 0.96 | 497 (1.72%) | 0.77 | 429 (1.63%) | 0.75 | 2897 (2.04%) | 0.911 |

| Genitourinary | 5592 (12.7%) | 18.5 | 5577 (13.1%) | 19.2 | 5156 (17.8%) | 18.4 | 5299 (20.2%) | 11.4 | 21,624 (15.2%) | 16.2 |

| Infectious diseases | 51 (0.116%) | 2.43 | 63 (0.148%) | 2.10 | 73 (0.252%) | 1.91 | 49 (0.186%) | 1.96 | 236 (0.166%) | 2.07 |

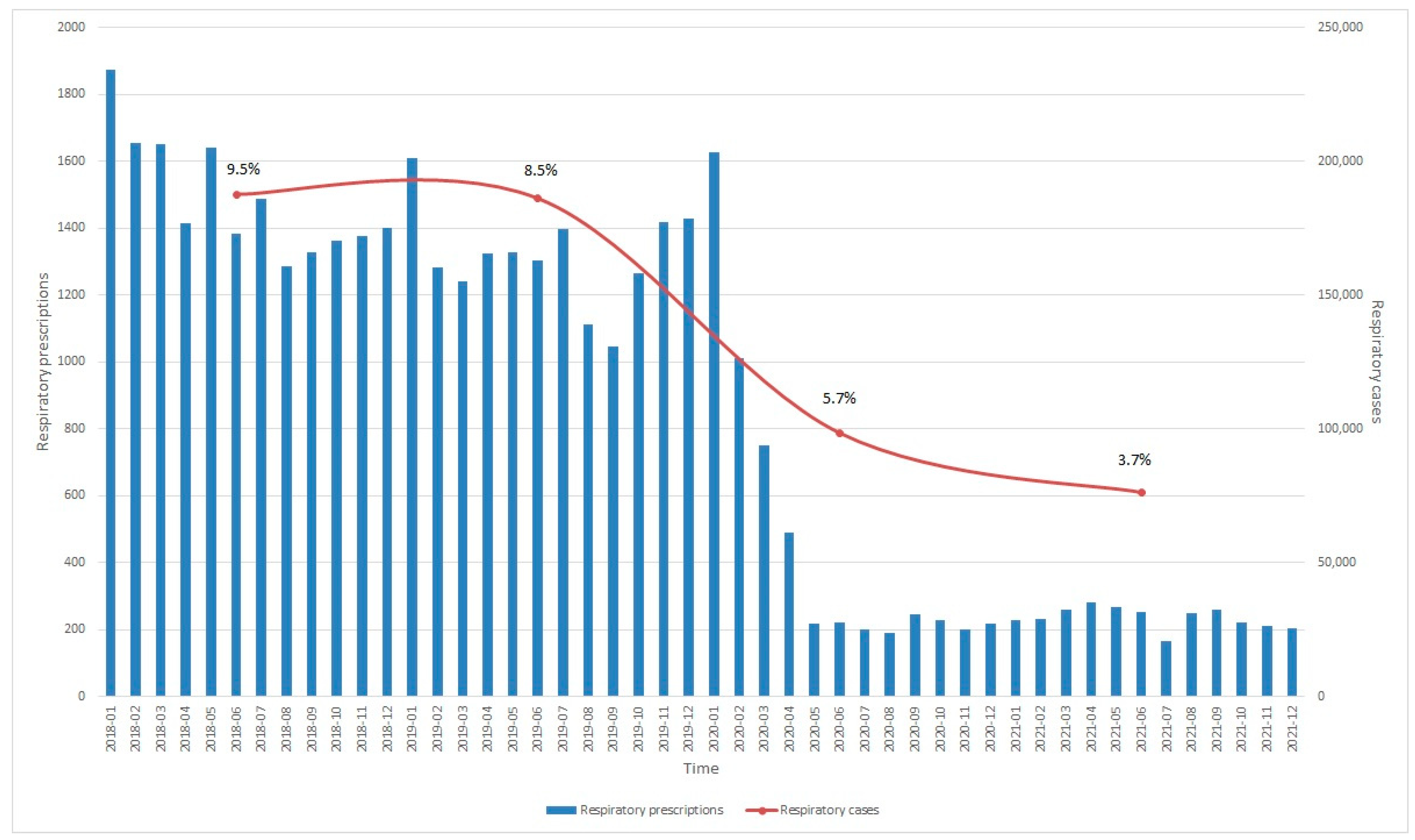

| Respiratory | 17,864 (40.6%) | 9.52 | 15,756 (37.0%) | 8.47 | 5611 (19.4%) | 5.70 | 2848 (10.8%) | 3.73 | 42,079 (29.6%) | 7.67 |

| Skin and soft tissue | 9856 (22.4%) | 11.9 | 10,903 (25.6%) | 12.7 | 10,343 (35.7%) | 13.2 | 9913 (37.7%) | 14.0 | 41,015 (28.9%) | 12.9 |

| Multiple diagnoses | 1625 (3.69%) | - | 1567 (3.68%) | - | 809 (2.79%) | - | 439 (1.67%) | - | 4440 (3.13%) | - |

| Undefined | 4734 (10.8%) | - | 4662 (10.9%) | - | 3567 (12.3%) | - | 4533 (17.2%) | - | 17,496 (12.3%) | - |

| Variable | 2018, n = 3991 (0.463%) 1 | 2019, n = 4042 (0.451%) 1 | 2020, n = 4274 (0.588%) 1 | 2021, n = 4591 (0.590%) 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Prescription Rate % | n (%) | Prescription Rate % | n (%) | Prescription Rate % | n (%) | Prescription Rate % | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 52 (17) | - | 51 (17) | - | 51 (17) | - | 51 (17) | - |

| Age group, n (%) | ||||||||

| 22–44 | 1373 (34.4%) | 0.638% | 1443 (35.7%) | 0.652% | 1490 (34.9%) | 0.924% | 1622 (35.3%) | 0.866% |

| 45–54 | 693 (17.4%) | 0.521% | 733 (18.1%) | 0.528% | 744 (17.4%) | 0.701% | 780 (17.0%) | 0.654% |

| 55–64 | 947 (23.7%) | 0.492% | 885 (21.9%) | 0.444% | 1037 (24.3%) | 0.619% | 1050 (22.9%) | 0.572% |

| 65–74 | 652 (16.3%) | 0.391% | 710 (17.6%) | 0.389% | 741 (17.3%) | 0.452% | 812 (17.7%) | 0.440% |

| >= 75 | 326 (8.17%) | 0.325% | 271 (6.71%) | 0.257% | 262 (6.13%) | 0.286% | 327 (7.12%) | 0.315% |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||||

| Male | 1956 (49.0%) | 0.499% | 1928 (47.7%) | 0.469% | 2079 (48.6%) | 0.608% | 2247 (48.9%) | 0.589% |

| Female | 2035 (51.0%) | 0.489% | 2114 (52.3%) | 0.490% | 2195 (51.4%) | 0.631% | 2344 (51.1%) | 0.590% |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||||

| Chinese | 2612 (65.4%) | 0.432% | 2704 (66.9%) | 0.427% | 2844 (66.5%) | 0.559% | 3123 (68.0%) | 0.576% |

| Malay | 612 (15.3%) | 0.467% | 552 (13.7%) | 0.411% | 611 (14.3%) | 0.567% | 608 (13.2%) | 0.592% |

| Indian | 484 (12.1%) | 0.629% | 522 (12.9%) | 0.667% | 521 (12.2%) | 0.772% | 539 (11.7%) | 0.754% |

| Others | 283 (7.09%) | 0.583% | 264 (6.53%) | 0.521% | 298 (6.97%) | 0.545% | 321 (6.99%) | 0.652% |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 978 (24.5%) | - | 887 (21.9%) | - | 973 (22.8%) | - | 983 (21.4%) | - |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 877 (22.0%) | - | 819 (20.3%) | - | 823 (19.3%) | - | 849 (18.5%) | - |

| Primary care clinic, n (%) | ||||||||

| Clinic A | 806 (20.2%) | 0.463% | 744 (18.4%) | 0.421% | 792 (18.5%) | 0.544% | 870 (19.0%) | 0.553% |

| Clinic B | 1048 (26.3%) | 0.452% | 948 (23.5%) | 0.412% | 916 (21.4%) | 0.496% | 953 (20.8%) | 0.517% |

| Clinic C | 800 (20.0%) | 0.517% | 845 (20.9%) | 0.519% | 919 (21.5%) | 0.710% | 937 (20.4%) | 0.689% |

| Clinic D | 758 (19.0%) | 0.398% | 746 (18.5%) | 0.385% | 839 (19.6%) | 0.538% | 970 (21.1%) | 0.584% |

| Clinic E | 579 (14.5%) | 0.523% | 759 (18.8%) | 0.569% | 808 (18.9%) | 0.724% | 761 (16.6%) | 0.651% |

| Clinic F | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | - | 100 (2.18%) | 0.538% |

| Prescriber, n (%) | ||||||||

| Family physician | 1950 (48.9%) | - | 2428 (60.1%) | - | 2563 (60.0%) | - | 3060 (66.7%) | - |

| Locum | 422 (10.6%) | - | 352 (8.71%) | - | 314 (7.35%) | - | 307 (6.69%) | - |

| Medical officer | 562 (14.1%) | - | 365 (9.03%) | - | 502 (11.8%) | - | 346 (7.54%) | - |

| Resident physician | 1057 (26.5%) | - | 897 (22.2%) | - | 895 (20.9%) | - | 878 (19.1%) | - |

| Training location, n (%) | ||||||||

| Local | 1447 (36.3%) | - | 1574 (38.9%) | - | 1608 (37.6%) | - | 1912 (41.6%) | - |

| Overseas | 2544 (63.7%) | - | 2468 (61.1%) | - | 2666 (62.4%) | - | 2679 (58.4%) | - |

| Prescription rate by diagnosis, % | - | 18.1% | - | 18.0% | - | 20.9% | - | 30.5% |

| Variable | 2018, n = 9703 (1.13%) 1 | 2019, n = 9386 (1.05%) 1 | 2020, n = 7159 (0.985%) 1 | 2021, n = 7040 (0.904%) 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Prescription Rate % | n (%) | Prescription Rate % | n (%) | Prescription Rate % | n (%) | Prescription Rate % | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 49 (17) | 49 (17) | 51 (17) | 50 (17) | ||||

| Age group, n (%) | ||||||||

| 22–44 | 3807 (39.2%) | 1.77% | 3754 (40.0%) | 1.70% | 2607 (36.4%) | 1.62% | 2666 (37.9%) | 1.42% |

| 45–54 | 1762 (18.2%) | 1.32% | 1548 (16.5%) | 1.12% | 1240 (17.3%) | 1.17% | 1225 (17.4%) | 1.03% |

| 55–64 | 2145 (22.1%) | 1.11% | 2059 (21.9%) | 1.03% | 1676 (23.4%) | 1.00% | 1512 (21.5%) | 0.823% |

| 65–74 | 1427 (14.7%) | 0.855% | 1487 (15.8%) | 0.816% | 1245 (17.4%) | 0.759% | 1223 (17.4%) | 0.663% |

| >= 75 | 562 (5.79%) | 0.561% | 538 (5.73%) | 0.510% | 391 (5.46%) | 0.427% | 414 (5.88%) | 0.398% |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||||

| Male | 4656 (48.0%) | 1.19% | 4633 (49.4%) | 1.13% | 3605 (50.4%) | 1.05% | 3567 (50.7%) | 0.934% |

| Female | 5047 (52.0%) | 1.21% | 4753 (50.6%) | 1.10% | 3554 (49.6%) | 1.02% | 3473 (49.3%) | 0.875% |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||||

| Chinese | 6699 (69.0%) | 1.11% | 6471 (68.9%) | 1.02% | 4913 (68.6%) | 0.965% | 4883 (69.4%) | 0.901% |

| Malay | 1636 (16.9%) | 1.25% | 1564 (16.7%) | 1.16% | 1181 (16.5%) | 1.10% | 1083 (15.4%) | 1.05% |

| Indian | 812 (8.37%) | 1.06% | 802 (8.55%) | 1.02% | 627 (8.76%) | 0.929% | 625 (8.88%) | 0.874% |

| Others | 556 (5.73%) | 1.15% | 549 (5.85%) | 1.08% | 438 (6.12%) | 0.802% | 449 (6.38%) | 0.912% |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 1913 (19.7%) | - | 1774 (18.9%) | - | 1469 (20.5%) | - | 1324 (18.8%) | - |

| Chronic kidney dsease, n (%) | 1679 (17.3%) | - | 1579 (16.8%) | - | 1272 (17.8%) | - | 1127 (16.0%) | - |

| Primary care clinic, n (%) | ||||||||

| Clinic A | 1956 (20.2%) | 1.12% | 1792 (19.1%) | 1.01% | 1478 (20.6%) | 1.02% | 1396 (19.8%) | 0.888% |

| Clinic B | 2456 (25.3%) | 1.06% | 2155 (23.0%) | 0.937% | 1358 (19.0%) | 0.736% | 1286 (18.3%) | 0.698% |

| Clinic C | 2024 (20.9%) | 1.31% | 2036 (21.7%) | 1.25% | 1672 (23.4%) | 1.29% | 1538 (21.8%) | 1.13% |

| Clinic D | 1918 (19.8%) | 1.01% | 1818 (19.4%) | 0.939% | 1376 (19.2%) | 0.882% | 1529 (21.7%) | 0.921% |

| Clinic E | 1349 (13.9%) | 1.22% | 1585 (16.9%) | 1.19% | 1275 (17.8%) | 1.14% | 1156 (16.4%) | 0.989% |

| Clinic F | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 135 (1.92%) | 0.726% | |||

| Prescriber, n (%) | ||||||||

| Family physician | 4862 (50.1%) | - | 5803 (61.8%) | - | 4377 (61.1%) | - | 4778 (67.9%) | - |

| Locum | 1162 (12.0%) | - | 853 (9.09%) | - | 567 (7.92%) | - | 522 (7.42%) | - |

| Medical officer | 1122 (11.6%) | - | 725 (7.72%) | - | 685 (9.57%) | - | 419 (5.95%) | - |

| Resident physician | 2557 (26.4%) | - | 2005 (21.4%) | - | 1530 (21.4%) | - | 1321 (18.8%) | - |

| Training location, n (%) | ||||||||

| Local | 3318 (34.1%) | - | 3603 (38.4%) | - | 2623 (36.6%) | - | 2928 (41.6%) | - |

| Overseas | 6385 (65.8%) | - | 5783 (61.6%) | - | 4536 (63.4%) | - | 4112 (58.4%) | - |

| Prescription rate by diagnosis, % | - | 27.9% | - | 28.2% | - | 27.7% | - | 29.1% |

| Variable | 2018, n = 14,558 (1.69%) 1 | 2019, n = 14,445 (1.61%) 1 | 2020, n = 14,359 (1.98%) 1 | 2021, n = 14,809 (1.90%) 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Prescription Rate % | n (%) | Prescription Rate % | n (%) | Prescription Rate % | n (%) | Prescription Rate % | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 56 (18) | - | 56 (18) | - | 57 (17) | - | 57 (17) | - |

| Age group, n (%) | ||||||||

| 22–44 | 3909 (26.9%) | 1.82% | 3793 (26.3%) | 1.71% | 3450 (24.0%) | 2.14% | 3667 (24.8%) | 1.96% |

| 45–54 | 2155 (14.8%) | 1.62% | 2048 (14.2%) | 1.48% | 2053 (14.3%) | 1.93% | 2135 (14.4%) | 1.79% |

| 55–64 | 3292 (22.6%) | 1.71% | 3231 (22.4%) | 1.62% | 3283 (22.9%) | 1.96% | 3273 (22.1%) | 1.78% |

| 65–74 | 3189 (21.9%) | 1.91% | 3301 (22.9%) | 1.81% | 3552 (24.7%) | 2.17% | 3721 (25.1%) | 2.02% |

| >= 75 | 2013 (13.8%) | 2.01% | 2072 (14.3%) | 1.96% | 2021 (14.1%) | 2.21% | 2013 (13.6%) | 1.94% |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||||

| Male | 7556 (51.9%) | 1.93% | 7414 (51.3%) | 1.80% | 7547 (52.6%) | 2.21% | 7550 (51.0%) | 1.98% |

| Female | 7002 (48.1%) | 1.68% | 7031 (48.7%) | 1.63% | 6812 (47.4%) | 1.96% | 7259 (49.0%) | 1.83% |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||||

| Chinese | 10,485 (72.0%) | 1.73% | 10,557 (73.1%) | 1.67% | 10,622 (74.0%) | 2.09% | 11,003 (74.3%) | 2.03% |

| Malay | 1826 (12.5%) | 1.39% | 1726 (11.9%) | 1.28% | 1691 (11.8%) | 1.57% | 1629 (11.0%) | 1.59% |

| Indian | 1461 (10.0%) | 1.90% | 1383 (9.57%) | 1.77% | 1325 (9.23%) | 1.96% | 1410 (9.52%) | 1.97% |

| Others | 786 (5.40%) | 1.62% | 779 (5.39%) | 1.54% | 721 (5.02%) | 1.32% | 767 (5.18%) | 1.56% |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 5166 (35.5%) | - | 5174 (35.8%) | - | 5450 (38.0%) | - | 5230 (35.3%) | - |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 4574 (31.4%) | - | 4509 (31.2%) | - | 4598 (32.0%) | - | 4356 (29.4%) | - |

| Primary care clinic, n (%) | ||||||||

| Clinic A | 2825 (19.4%) | 1.62% | 2740 (19.0%) | 1.55% | 2976 (20.7%) | 2.05% | 2983 (20.1%) | 1.90% |

| Clinic B | 3596 (24.7%) | 1.55% | 3406 (23.6%) | 1.48% | 3142 (21.9%) | 1.70% | 3222 (21.8%) | 1.75% |

| Clinic C | 3426 (23.5%) | 2.21% | 3301 (22.9%) | 2.03% | 2932 (20.4%) | 2.27% | 2965 (20.0%) | 2.18% |

| Clinic D | 3003 (20.6%) | 1.58% | 3145 (21.8%) | 1.62% | 3426 (23.9%) | 2.20% | 3361 (22.7%) | 2.03% |

| Clinic E | 1708 (11.7%) | 1.54% | 1853 (12.8%) | 1.39% | 1883 (13.1%) | 1.69% | 1965 (13.3%) | 1.68% |

| Clinic F | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | - | 313 (2.11%) | 1.68% |

| Prescriber, n (%) | ||||||||

| Family physician | 7679 (52.7%) | - | 8692 (60.2%) | - | 8781 (61.2%) | - | 10,436 (70.5%) | - |

| Locum | 1641 (11.3%) | - | 1198 (8.29%) | - | 1039 (7.24%) | - | 994 (6.71%) | - |

| Medical officer | 1573 (10.8%) | - | 1200 (8.31%) | - | 1267 (8.82%) | - | 992 (6.70%) | - |

| Resident physician | 3665 (25.2%) | - | 3355 (23.2%) | - | 3272 (22.8%) | - | 2387 (16.1%) | - |

| Training location, n (%) | ||||||||

| Local | 5251 (36.1%) | - | 5705 (39.5%) | - | 5521 (38.5%) | - | 6264 (42.3%) | - |

| Overseas | 9307 (63.9%) | - | 8740 (60.5%) | - | 8838 (61.6%) | - | 8545 (57.7%) | - |

| Prescription rate by diagnosis, % | - | 17.6% | - | 16.8% | - | 18.3% | - | 20.9% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koh, S.W.C.; Lee, V.M.E.; Low, S.H.; Tan, W.Z.; Valderas, J.M.; Loh, V.W.K.; Sundram, M.; Hsu, L.Y. Prescribing Antibiotics in Public Primary Care Clinics in Singapore: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 762. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12040762

Koh SWC, Lee VME, Low SH, Tan WZ, Valderas JM, Loh VWK, Sundram M, Hsu LY. Prescribing Antibiotics in Public Primary Care Clinics in Singapore: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Antibiotics. 2023; 12(4):762. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12040762

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoh, Sky Wei Chee, Vivien Min Er Lee, Si Hui Low, Wei Zhi Tan, José María Valderas, Victor Weng Keong Loh, Meena Sundram, and Li Yang Hsu. 2023. "Prescribing Antibiotics in Public Primary Care Clinics in Singapore: A Retrospective Cohort Study" Antibiotics 12, no. 4: 762. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12040762

APA StyleKoh, S. W. C., Lee, V. M. E., Low, S. H., Tan, W. Z., Valderas, J. M., Loh, V. W. K., Sundram, M., & Hsu, L. Y. (2023). Prescribing Antibiotics in Public Primary Care Clinics in Singapore: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Antibiotics, 12(4), 762. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12040762