Unraveling the Role of Metals and Organic Acids in Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in the Food Chain

Abstract

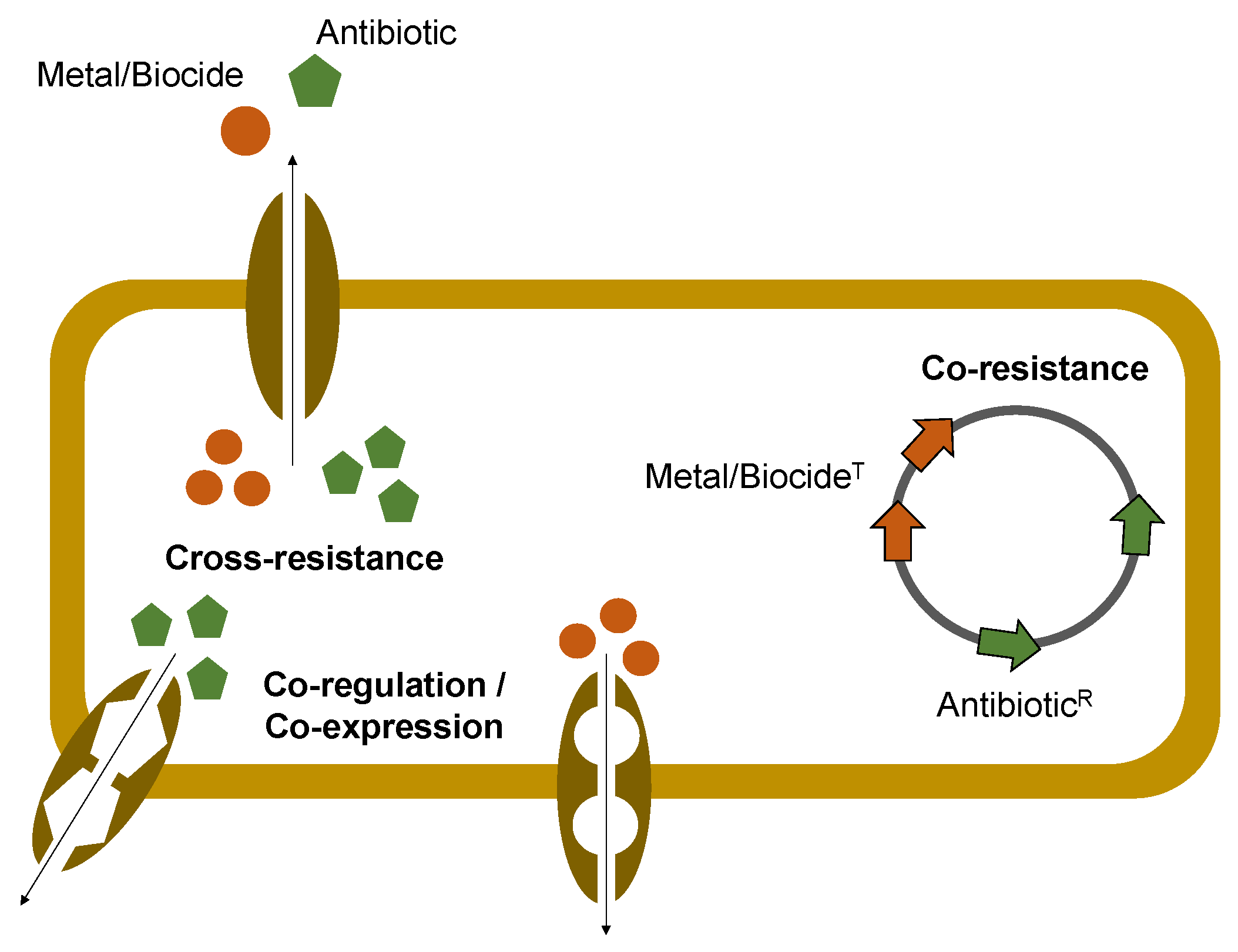

:1. Introduction

2. Metals

2.1. Copper

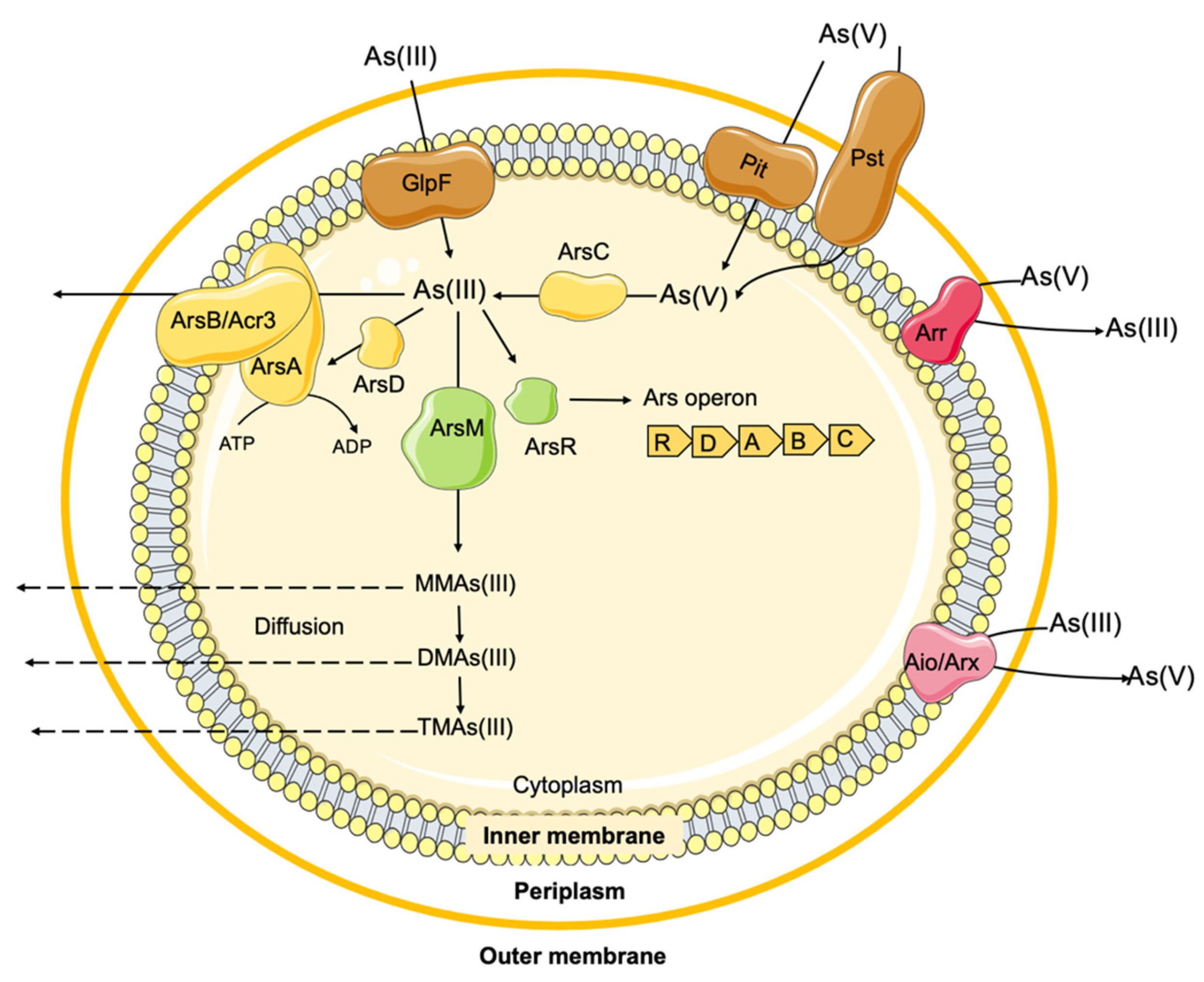

2.2. Arsenic

2.3. Mercury

3. Organic Acids

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). 10 Global Health Issues to Track in 2021; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/10-global-health-issues-to-track-in-2021 (accessed on 9 May 2023).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Antimicrobial Resistance; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 9 May 2023).

- European Commission. AMR: A Major European and Global Challenge; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2020-01/amr_2017_factsheet_0.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: A Systematic Analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations; Government of the United Kingdom: London, UK, 2016.

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament: A European One Health Action Plan against Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2020-01/amr_2017_action-plan_0.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2023).

- Levy, S.B.; Marshall, B. Antibacterial Resistance Worldwide: Causes, Challenges and Responses. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, S122–S129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolaou, K.C.; Rigol, S. A Brief History of Antibiotics and Select Advances in Their Synthesis. J. Antibiot. 2018, 71, 153–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, B.G.; Schellevis, F.; Stobberingh, E.; Goossens, H.; Pringle, M. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Antibiotic Consumption on Antibiotic Resistance. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landers, T.F.; Cohen, B.; Wittum, T.E.; Larson, E.L. A Review of Antibiotic Use in Food Animals: Perspective, Policy, and Potential. Public Health Rep. 2012, 127, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, A.H.; Moore, L.S.P.; Sundsfjord, A.; Steinbakk, M.; Regmi, S.; Karkey, A.; Guerin, P.J.; Piddock, L.J.V. Understanding the Mechanisms and Drivers of Antimicrobial Resistance. Lancet 2016, 387, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, B.M.; Levy, S.B. Food Animals and Antimicrobials: Impacts on Human Health. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 24, 718–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ); Koutsoumanis, K.; Allende, A.; Álvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Bolton, D.; Bover-Cid, S.; Chemaly, M.; Davies, R.; De Cesare, A.; Herman, L.; et al. Role Played by the Environment in the Emergence and Spread of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) through the Food Chain. EFSA J. 2021, 19, e06651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interagency Coordination Group on Antimicrobial Resistance (IACG). No Time to Wait: Securing the Future from Drug-Resistant Infections—Report to the Secretary-General of the United Nations. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/no-time-to-wait-securing-the-future-from-drug-resistant-infections-en.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2023).

- McEwen, S.A.; Collignon, P.J. Antimicrobial Resistance: A One Health Perspective. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018, 6, 521–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.; Hughes, J.M. Critical Importance of a One Health Approach to Antimicrobial Resistance. EcoHealth 2019, 16, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Gray, G.C. The Mandate for a Global “One Health” Approach to Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 100, 227–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irfan, M.; Almotiri, A.; AlZeyadi, Z.A. Antimicrobial Resistance and Its Drivers—A Review. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samtiya, M.; Matthews, K.R.; Dhewa, T.; Puniya, A.K. Antimicrobial Resistance in the Food Chain: Trends, Mechanisms, Pathways, and Possible Regulation Strategies. Foods 2022, 11, 2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019; CDC, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Van Boeckel, T.P.; Pires, J.; Silvester, R.; Zhao, C.; Song, J.; Criscuolo, N.G.; Gilbert, M.; Bonhoeffer, S.; Laxminarayan, R. Global Trends in Antimicrobial Resistance in Animals in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Science 2019, 365, eaaw1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO); World Health Organization (WHO). Foodborne Antimicrobial Resistance—Compendium of Codex Standards; First Revision; Codex Alimentarius Commission: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Miguel, J.; Hernández, M.; Fernández-Natal, I.; Rodríguez-Lázaro, D. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Harboring mecC in Livestock in Spain. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 4067–4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quddoumi, S.S.; Bdour, S.M.; Mahasneh, A.M. Isolation and Characterization of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from Livestock and Poultry Meat. Ann. Microbiol. 2006, 56, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Li, J.; Hu, C.; Jin, S.; Li, F.; Guo, Y.; Ran, L.; Ma, Y. Isolation and Characterization of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus from Swine and Workers in China. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2009, 64, 680–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantosti, A.; Del Grosso, M.; Tagliabue, S.; Macri, A.; Caprioli, A. Decrease of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci in Poultry Meat after Avoparcin Ban. Lancet 1999, 354, 741–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemcke, R.; Bülte, M. Occurrence of the Vancomycin-Resistant Genes vanA, vanB, vanC1, vanC2 and vanC3 in Enterococcus Strains Isolated from Poultry and Pork. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2000, 60, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisner, A.; Feierl, G.; Gorkiewicz, G.; Dieber, F.; Kessler, H.H.; Marth, E.; Köfer, J. High Prevalence of VanA-Type Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci in Austrian Poultry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 6407–6409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, J.; Jordens, J.Z.; Griffiths, D.T. Farm Animals as a Putative Reservoir for Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcal Infection in Man. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1994, 34, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S.; Ohnishi, M.; Kawanishi, M.; Akiba, M.; Kuroda, M. Investigation of a Plasmid Genome Database for Colistin-Resistance Gene mcr-1. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 284–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tse, H.; Yuen, K.-Y. Dissemination of the mcr-1 Colistin Resistance Gene. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 145–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, H.E.; Granier, S.A.; Marault, M.; Millemann, Y.; Den Bakker, H.C.; Nightingale, K.K.; Bugarel, M.; Ison, S.A.; Scott, H.M.; Loneragan, G.H. Dissemination of the mcr-1 Colistin Resistance Gene. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 144–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Zhang, P.; Du, P.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Sun, H.; Wang, Z.; Cui, S.; Li, R.; et al. Prevalence and Genomic Characteristics of Mcr -Positive Escherichia coli Strains Isolated from Humans, Pigs, and Foods in China. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e04569-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.-T.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Wan, S.-W.; Hao, J.-J.; Jiang, R.-D.; Song, F.-J. Characteristics of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Ready-to-Eat Vegetables in China. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köck, R.; Daniels-Haardt, I.; Becker, K.; Mellmann, A.; Friedrich, A.W.; Mevius, D.; Schwarz, S.; Jurke, A. Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Wildlife, Food-Producing, and Companion Animals: A Systematic Review. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018, 24, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wen, J.; Wang, S.; Xu, X.; Zhan, Z.; Chen, Z.; Bai, J.; Qu, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; et al. Plasmid-Encoded blaNDM-5 Gene That Confers High-Level Carbapenem Resistance in Salmonella Typhimurium of Pork Origin. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 1485–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; He, J.; Li, Q.; Tang, Y.; Wang, J.; Pan, Z.; Chen, X.; Jiao, X. First Detection of NDM-5-Positive Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Isolated from Retail Pork in China. Microb. Drug Resist. 2020, 26, 434–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennani, H.; Mateus, A.; Mays, N.; Eastmure, E.; Stärk, K.D.C.; Häsler, B. Overview of Evidence of Antimicrobial Use and Antimicrobial Resistance in the Food Chain. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. The European Union Summary Report on Antimicrobial Resistance in Zoonotic and Indicator Bacteria from Humans, Animals and Food in 2019–2020. EFSA J. 2022, 20, e07209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The FAO Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance 2021–2025; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.L.; Caffrey, N.P.; Nóbrega, D.B.; Cork, S.C.; Ronksley, P.E.; Barkema, H.W.; Polachek, A.J.; Ganshorn, H.; Sharma, N.; Kellner, J.D.; et al. Restricting the Use of Antibiotics in Food-Producing Animals and Its Associations with Antibiotic Resistance in Food-Producing Animals and Human Beings: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Planet. Health 2017, 1, e316–e327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postma, M.; Vanderhaeghen, W.; Sarrazin, S.; Maes, D.; Dewulf, J. Reducing Antimicrobial Usage in Pig Production without Jeopardizing Production Parameters. Zoonoses Public Health 2017, 64, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, S.; Mourão, J.; Novais, Â.; Campos, J.; Peixe, L.; Antunes, P. From Farm to Fork: Colistin Voluntary Withdrawal in Portuguese Farms Reflected in Decreasing Occurrence of Mcr-1-Carrying Enterobacteriaceae from Chicken Meat. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 7563–7577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourão, J.; Ribeiro-Almeida, M.; Novais, C.; Magalhães, M.; Rebelo, A.; Ribeiro, S.; Peixe, L.; Novais, Â.; Antunes, P. From Farm to Fork: Persistence of Clinically-Relevant Multidrug-Resistant and Copper-Tolerant Klebsiella pneumoniae Long after Colistin Withdrawal in Poultry Production. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e01386-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Direção Geral da Saúde (DGS). Plano Nacional de Combate à Resistência aos Antimicrobianos 2019–2023. Âmbito Do Conceito “Uma Só Saúde”; DGS: Lisbon, Portugal, 2019.

- European Commission. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) on Designating Antimicrobials or Groups of Antimicrobials Reserved for Treatment of Certain Infections in Humans, in Accordance with Regulation (EU) 2019/6 of the European Parliament and of the Council; OJ L191/58; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022R1255 (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- European Medicines Agency (EMA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Veterinary Use (CVMP); EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ); Murphy, D.; Ricci, A.; Auce, Z.; Beechinor, J.G.; Bergendahl, H.; Breathnach, R.; Bureš, J.; Duarte Da Silva, J.P.; et al. EMA and EFSA Joint Scientific Opinion on Measures to Reduce the Need to Use Antimicrobial Agents in Animal Husbandry in the European Union, and the Resulting Impacts on Food Safety (RONAFA). EFSA J. 2017, 15, e04666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Sales of Veterinary Antimicrobial Agents in 31 European Countries in 2021—Trends from 2010 to 2021—Twelfth ESVAC Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhelle, C. Pharming Animals: A Global History of Antibiotics in Food Production (1935–2017). Palgrave Commun. 2018, 4, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety. A Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2020-05/f2f_action-plan_2020_strategy-info_en.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Cheng, G.; Hao, H.; Xie, S.; Wang, X.; Dai, M.; Huang, L.; Yuan, Z. Antibiotic Alternatives: The Substitution of Antibiotics in Animal Husbandry? Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO), Regional Office for Europe. Tackling Antibiotic Resistance from a Food Safety Perspective in Europe; WHO/Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/326398 (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Mehdi, Y.; Létourneau-Montminy, M.-P.; Gaucher, M.-L.; Chorfi, Y.; Suresh, G.; Rouissi, T.; Brar, S.K.; Côté, C.; Ramirez, A.A.; Godbout, S. Use of Antibiotics in Broiler Production: Global Impacts and Alternatives. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 4, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, M.C.; Hill, G.M. Trace Mineral Supplementation for the Intestinal Health of Young Monogastric Animals. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadde, U.; Kim, W.H.; Oh, S.T.; Lillehoj, H.S. Alternatives to Antibiotics for Maximizing Growth Performance and Feed Efficiency in Poultry: A Review. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2017, 18, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rensing, C.; Moodley, A.; Cavaco, L.M.; McDevitt, S.F. Resistance to Metals Used in Agricultural Production. In Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacteria from Livestock and Companion Animals; Schwarz, S., Cavaco, L.M., Shen, J., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachman, K.E.; Baron, P.A.; Raber, G.; Francesconi, K.A.; Navas-Acien, A.; Love, D.C. Roxarsone, Inorganic Arsenic, and Other Arsenic Species in Chicken: A U.S.-Based Market Basket Sample. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013, 121, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA), Committee for Veterinary Medicinal Products (CVMP). Copper Chloride, Copper Gluconate, Copper Heptanoate, Copper Oxide, Copper Methionate, Copper Sulfate and Dicopper Oxide: Summary Report. 1998. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/mrl-report/copper-chloride-copper-gluconate-copper-heptanoate-copper-oxide-copper-methionate-copper-sulphate_en.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- European Medicines Agency (EMA), Committee for Veterinary Medicinal Products (CVMP). Thiomersal and Timerfonate Summary Report. 1996. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/mrl-report/thiomersal-timerfonate-summary-report-committee-veterinary-medicinal-products_en.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- European Medicines Agency (EMA), Committee for Veterinary Medicinal Products (CVMP). Zinc Salts Summary Report. 1996. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/mrl-report/zinc-salts-summary-report-committee-veterinary-medicinal-products_en.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Frei, A.; Zuegg, J.; Elliott, A.G.; Baker, M.; Braese, S.; Brown, C.; Chen, F.; Dowson, C.G.; Dujardin, G.; Jung, N.; et al. Metal Complexes as a Promising Source for New Antibiotics. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 2627–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemire, J.A.; Harrison, J.J.; Turner, R.J. Antimicrobial Activity of Metals: Mechanisms, Molecular Targets and Applications. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puschenreiter, M.; Horak, O.; Friesl, W.; Hartl, W. Low-Cost Agricultural Measures to Reduce Heavy Metal Transfer into the Food Chain—A Review. Plant Soil Environ. 2005, 51, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vareda, J.P.; Valente, A.J.M.; Durães, L. Assessment of Heavy Metal Pollution from Anthropogenic Activities and Remediation Strategies: A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 246, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Cheng, H.; Tao, S. Environmental and Human Health Challenges of Industrial Livestock and Poultry Farming in China and Their Mitigation. Environ. Int. 2017, 107, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/1039 of 23 July 2018 Concerning the Authorisation of Copper(II) Diacetate Monohydrate, Copper(II) Carbonate Dihydroxy Monohydrate, Copper(II) Chloride Dihydrate, Copper(II) Oxide, Copper(II) Sulphate Pentahydrate, Copper(II) Chelate of Amino Acids Hydrate, Copper(II) Chelate of Protein Hydrolysates, Copper(II) Chelate of Glycine Hydrate (Solid) and Copper(II) Chelate of Glycine Hydrate (Liquid) as Feed Additives for all Animal Species and Amending Regulations (EC) No 1334/2003, (EC) No 479/2006 and (EU) No 349/2010 and Implementing Regulations (EU) No 269/2012, (EU) No 1230/2014 and (EU) 2016/2261; OJ L186/3; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018R1039&from=NL (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- European Commission. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/1095 of 6 July 2016 Concerning the Authorisation of Zinc Acetate Dihydrate, Zinc Chloride Anhydrous, Zinc Oxide, Zinc Sulphate Heptahydrate, Zinc Sulphate Monohydrate, Zinc Chelate of Amino Acids Hydrate, Zinc Chelate of Protein Hydrolysates, Zinc Chelate of Glycine Hydrate (Solid) and Zinc Chelate of Glycine Hydrate (Liquid) as Feed Additives for all Animal Species and Amending Regulations (EC) No 1334/2003, (EC) No 479/2006, (EU) No 335/2010 and Implementing Regulations (EU) No 991/2012 and (EU) No 636/2013; OJ L182/7; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016R1095 (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Ölmez, H.; Kretzschmar, U. Potential Alternative Disinfection Methods for Organic Fresh-Cut Industry for Minimizing Water Consumption and Environmental Impact. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 42, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Huang, C.-H. Reactivity of Peracetic Acid with Organic Compounds: A Critical Review. ACS EST Water 2021, 1, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Chemicals Agency (ECHA). Peracetic Acid. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/es/substance-information/-/substanceinfo/100.001.079 (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) No 101/2013 of 4 February 2013 Concerning the Use of Lactic Acid to Reduce Microbiological Surface Contamination on Bovine Carcases; OJ L3471; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2013:034:0001:0003:EN:PDF (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- European Commission. Commission Directive of 8 July 1985 Amending the Annexes to Council Directive 70/524/EEC Concerning Additives in Feedingstuffs (85/429/EEC); OJ L 245; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, R.; Wales, A. Antimicrobial Resistance on Farms: A Review Including Biosecurity and the Potential Role of Disinfectants in Resistance Selection. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2019, 18, 753–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdankhah, S.; Rudi, K.; Bernhoft, A. Zinc and Copper in Animal Feed—Development of Resistance and Co-Resistance to Antimicrobial Agents in Bacteria of Animal Origin. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2014, 25, 25862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, C.; Asiani, K.; Arya, S.; Rensing, C.; Stekel, D.J.; Larsson, D.G.J.; Hobman, J.L. Chapter Seven—Metal Resistance. In Advances in Microbial Physiology; Poole, R.K., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; Volume 70, pp. 261–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutkina, J.; Marathe, N.P.; Flach, C.-F.; Larsson, D.G.J. Antibiotics and Common Antibacterial Biocides Stimulate Horizontal Transfer of Resistance at Low Concentrations. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 616–617, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Gu, A.Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, B.; Li, D.; Chen, J. Sub-Lethal Concentrations of Heavy Metals Induce Antibiotic Resistance via Mutagenesis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 369, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Song, H.; Lu, J.; Yuan, Z.; Guo, J. Copper Nanoparticles and Copper Ions Promote Horizontal Transfer of Plasmid-Mediated Multi-Antibiotic Resistance Genes across Bacterial Genera. Environ. Int. 2019, 129, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gu, A.Z.; Cen, T.; Li, X.; He, M.; Li, D.; Chen, J. Sub-Inhibitory Concentrations of Heavy Metals Facilitate the Horizontal Transfer of Plasmid-Mediated Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Water Environment. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 237, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalecki, A.G.; Crawford, C.L.; Wolschendorf, F. Chapter Six—Copper and Antibiotics: Discovery, Modes of Action, and Opportunities for Medicinal Applications. In Advances in Microbial Physiology; Poole, R.K., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; Volume 70, pp. 193–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanovic, M.I.; Ding, C.; Thiele, D.J.; Darwin, K.H. Copper in Microbial Pathogenesis: Meddling with the Metal. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 11, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladomersky, E.; Petris, M.J. Copper Tolerance and Virulence in Bacteria. Metallomics 2015, 7, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.-E.; Nevitt, T.; Thiele, D.J. Mechanisms for Copper Acquisition, Distribution and Regulation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008, 4, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festa, R.A.; Thiele, D.J. Copper: An Essential Metal in Biology. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, R877–R883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, P.; Pereira, A.S.; Moura, J.J.G.; Moura, I. Metalloenzymes of the Denitrification Pathway. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2006, 100, 2087–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, A.; Verderosa, A.D.; Elliott, A.G.; Zuegg, J.; Blaskovich, M.A.T. Metals to Combat Antimicrobial Resistance. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2023, 7, 202–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, M.; Hartemann, P.; Engels-Deutsch, M. Antimicrobial Applications of Copper. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2016, 219, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dollwet, H.H.A.; Sorenson, J.R.J. Historic Uses of Copper Compounds in Medicine. Trace Elem. Med. 1985, 2, 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Lamichhane, J.R.; Osdaghi, E.; Behlau, F.; Köhl, J.; Jones, J.B.; Aubertot, J.-N. Thirteen Decades of Antimicrobial Copper Compounds Applied in Agriculture. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 38, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehne, S.; Roßberg, D.; Röhrig, P.; Von Mehring, F.; Weihrauch, F.; Kanthak, S.; Kienzle, J.; Patzwahl, W.; Reiners, E.; Gitzel, J. The Use of Copper Pesticides in Germany and the Search for Minimization and Replacement Strategies. Org. Farm. 2017, 3, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrees, M.; Ali, S.; Rizwan, M.; Ibrahim, M.; Abbas, F.; Farid, M.; Zia-ur-Rehman, M.; Irshad, M.K.; Bharwana, S.A. The Effect of Excess Copper on Growth and Physiology of Important Food Crops: A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 8148–8162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grass, G.; Rensing, C.; Solioz, M. Metallic Copper as an Antimicrobial Surface. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Chemicals Agency (ECHA). Information on Biocides. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/pt/information-on-chemicals/biocidal-active-substances?p_p_id=dissactivesubstances_WAR_dissactivesubstancesportlet&p_p_lifecycle=1&p_p_state=normal&p_p_mode=view&_dissactivesubstances_WAR_dissactivesubstancesportlet_javax.portlet.a (accessed on 13 May 2023).

- Montero, D.A.; Arellano, C.; Pardo, M.; Vera, R.; Gálvez, R.; Cifuentes, M.; Berasain, M.A.; Gómez, M.; Ramírez, C.; Vidal, R.M. Antimicrobial Properties of a Novel Copper-Based Composite Coating with Potential for Use in Healthcare Facilities. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2019, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyce, J.O.; Michels, H.; Keevil, C.W. Use of Copper Cast Alloys to Control Escherichia coli O157 Cross-Contamination during Food Processing. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 4239–4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadishettar, N.; Bhat, K.U.; Bhat Panemangalore, D. Coating Technologies for Copper Based Antimicrobial Active Surfaces: A Perspective Review. Metals 2021, 11, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFlorio, W.; Liu, S.; White, A.R.; Taylor, T.M.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Min, Y.; Scholar, E.M.A. Recent Developments in Antimicrobial and Antifouling Coatings to Reduce or Prevent Contamination and Cross-contamination of Food Contact Surfaces by Bacteria. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 3093–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, E.-L.; Yosef, H.; Borkow, G.; Caine, Y.; Sasson, A.; Moses, A.E. Reduction of Health Care–Associated Infection Indicators by Copper Oxide-Impregnated Textiles: Crossover, Double-Blind Controlled Study in Chronic Ventilator-Dependent Patients. Am. J. Infect. Control 2017, 45, 401–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewawaduge, C.; Senevirathne, A.; Jawalagatti, V.; Kim, J.W.; Lee, J.H. Copper-Impregnated Three-Layer Mask Efficiently Inactivates SARS-CoV2. Environ. Res. 2021, 196, 110947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Ren, L.; Yang, K.; Qin, L. Anti-Infection Mechanism of a Novel Dental Implant Made of Titanium-Copper (TiCu) Alloy and Its Mechanism Associated with Oral Microbiology. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 8, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melamed, E.; Kiambi, P.; Okoth, D.; Honigber, I.; Tamir, E.; Borkow, G. Healing of Chronic Wounds by Copper Oxide-Impregnated Wound Dressings—Case Series. Medicina 2021, 57, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forouzandeh, A.; Blavi, L.; Abdelli, N.; Melo-Duran, D.; Vidal, A.; Rodríguez, M.; Monteiro, A.N.T.R.; Pérez, J.F.; Darwich, L.; Solà-Oriol, D. Effects of Dicopper Oxide and Copper Sulfate on Growth Performance and Gut Microbiota in Broilers. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, C.D.; Stein, H.H. Digestibility and Metabolism of Copper in Diets for Pigs and Influence of Dietary Copper on Growth Performance, Intestinal Health, and Overall Immune Status: A Review. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cruz Ferreira Júnior, H.; da Silva, D.L.; de Carvalho, B.R.; de Oliveira, H.C.; Cunha Lima Muniz, J.; Junior Alves, W.; Eugene Pettigrew, J.; Eliza Facione Guimarães, S.; da Silva Viana, G.; Hannas, M.I. Broiler Responses to Copper Levels and Sources: Growth, Tissue Mineral Content, Antioxidant Status and mRNA Expression of Genes Involved in Lipid and Protein Metabolism. BMC Vet. Res. 2022, 18, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.B.; Kuang, Y.G.; Ma, Z.X.; Liu, Y.G. The Effect of Feeding Broiler with Inorganic, Organic, and Coated Trace Minerals on Performance, Economics, and Retention of Copper and Zinc. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2020, 29, 1084–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marco, M.; Zoon, M.V.; Margetyal, C.; Picart, C.; Ionescu, C. Dietary Administration of Glycine Complexed Trace Minerals Can Improve Performance and Slaughter Yield in Broilers and Reduces Mineral Excretion. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2017, 232, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.; Vadalasetty, K.P.; Chwalibog, A.; Sawosz, E. Copper Nanoparticles as an Alternative Feed Additive in Poultry Diet: A Review. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2018, 7, 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathakoti, K.; Manubolu, M.; Hwang, H.-M. Nanostructures: Current Uses and Future Applications in Food Science. J. Food Drug Anal. 2017, 25, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-Elsalam, K.A. Chapter 1—Copper-Based Nanomaterials: Next-Generation Agrochemicals: A Note from the Editor. In Copper Nanostructures: Next-Generation of Agrochemicals for Sustainable Agroecosystems; Abd-Elsalam, K.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarczuk, K.; Piotrowska-Seget, Z. Molecular Basis of Active Copper Resistance Mechanisms in Gram-Negative Bacteria. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2013, 29, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig, S.; Rees, E.M.; Thiele, D.J. The ABCDs of Periplasmic Copper Trafficking. Structure 2002, 10, 1292–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupont, C.L.; Grass, G.; Rensing, C. Copper Toxicity and the Origin of Bacterial Resistance—New Insights and Applications. Metallomics 2011, 3, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banci, L. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. In Metallomics and the Cell; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macomber, L.; Imlay, J.A. The Iron-Sulfur Clusters of Dehydratases Are Primary Intracellular Targets of Copper Toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 8344–8349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besold, A.N.; Culbertson, E.M.; Culotta, V.C. The Yin and Yang of Copper during Infection. JBIC J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 21, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, R.; Ross, M.O.; Batelu, S.; Kusowski, A.; Stemmler, T.L.; Hoffman, B.M.; Rosenzweig, A.C. Cu+-Specific CopB Transporter: Revising P1B-Type ATPase Classification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 2108–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odermatt, A.; Suter, H.; Krapf, R.; Solioz, M. An ATPase Operon Involved in Copper Resistance by Enterococcus hirae. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1992, 671, 484–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solioz, M.; Stoyanov, J.V. Copper Homeostasis in Enterococcus hirae. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 27, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solioz, M.; Odermatt, A. Copper and Silver Transport by CopB-ATPase in Membrane Vesicles of Enterococcus hirae. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 9217–9221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobine, P.; Wickramasinghe, W.A.; Harrison, M.D.; Weber, T.; Solioz, M.; Dameron, C.T. The Enterococcus hirae Copper Chaperone CopZ Delivers Copper(I) to the CopY Repressor. FEBS Lett. 1999, 445, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strausak, D.; Solioz, M. CopY Is a Copper-Inducible Repressor of the Enterococcus hirae Copper ATPases. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 8932–8936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rensing, C.; Grass, G. Escherichia coli Mechanisms of Copper Homeostasis in a Changing Environment. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 27, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Outten, F.W.; Huffman, D.L.; Hale, J.A.; O’Halloran, T.V. The Independent Cue and cus Systems Confer Copper Tolerance during Aerobic and Anaerobic Growth in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 30670–30677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi, K.S.; Henderson, J.P. Pathogenic Adaptations to Host-Derived Antibacterial Copper. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2014, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.L.; Barrett, S.R.; Camakaris, J.; Rouch, D.A. Molecular Genetics and Transport Analysis of the Copper-Resistance Determinant (Pco) from Escherichia coli Plasmid pRJ1004. Mol. Microbiol. 1995, 17, 1153–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouch, D.A.; Brown, N.L. Copper-Inducible Transcriptional Regulation at Two Promoters in the Escherichia coli Copper Resistance Determinant Pco. Microbiology 1997, 143, 1191–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Grass, G.; Rensing, C.; Barrett, S.R.; Yates, C.J.D.; Stoyanov, J.V.; Brown, N.L. The Pco Proteins Are Involved in Periplasmic Copper Handling in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 295, 616–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.; Udagedara, S.R.; Sze, C.M.; Ryan, T.M.; Howlett, G.J.; Xiao, Z.; Wedd, A.G. PcoE—A Metal Sponge Expressed to the Periplasm of Copper Resistance Escherichia coli. Implication of Its Function Role in Copper Resistance. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012, 115, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rensing, C.; Alwathnani, H.A.; McDevitt, S.F. The Copper Metallome in Prokaryotic Cells. In Stress and Environmental Regulation of Gene Expression and Adaptation in Bacteria; De Bruijn, F.J., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Lüthje, F.L.; Qin, Y.; McDevitt, S.F.; Lutay, N.; Hobman, J.L.; Asiani, K.; Soncini, F.C.; German, N.; Zhang, S.; et al. Survival in Amoeba—A Major Selection Pressure on the Presence of Bacterial Copper and Zinc Resistance Determinants? Identification of a “Copper Pathogenicity Island”. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 5817–5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Matsui, K.; Lo, J.-F.; Silver, S. Molecular Basis for Resistance to Silver Cations in Salmonella. Nat. Med. 1999, 5, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, S. Bacterial Silver Resistance: Molecular Biology and Uses and Misuses of Silver Compounds. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 27, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourão, J. Metal Tolerance in Emerging Clinically Relevant Multidrug-Resistant Salmonella enterica Serotype 4,[5],12:i:− Clones Circulating in Europe. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2015, 45, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourão, J.; Marçal, S.; Ramos, P.; Campos, J.; Machado, J.; Peixe, L.; Novais, C.; Antunes, P. Tolerance to Multiple Metal Stressors in Emerging Non-Typhoidal MDR Salmonella Serotypes: A Relevant Role for Copper in Anaerobic Conditions. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 2147–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, L.N.; Siqueira, T.E.S.; Martinez, R.; Darini, A.L.C. Multidrug-Resistant CTX-M-(15, 9, 2)- and KPC-2-Producing Enterobacter hormaechei and Enterobacter asburiae Isolates Possessed a Set of Acquired Heavy Metal Tolerance Genes Including a Chromosomal sil Operon (for Acquired Silver Resistance). Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, J.E.; Fricker, A.D.; Kapili, B.J.; Petassi, M.T. Heteromeric Transposase Elements: Generators of Genomic Islands across Diverse Bacteria: Heteromeric Transposase Elements. Mol. Microbiol. 2014, 93, 1084–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Switt, A.I.; Den Bakker, H.C.; Cummings, C.A.; Rodriguez-Rivera, L.D.; Govoni, G.; Raneiri, M.L.; Degoricija, L.; Brown, S.; Hoelzer, K.; Peters, J.E.; et al. Identification and Characterization of Novel Salmonella Mobile Elements Involved in the Dissemination of Genes Linked to Virulence and Transmission. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, G.; Rozas, K.; Amachawadi, R.; Scott, H.; Norman, K.; Nagaraja, T.; Tokach, M.; Boerlin, P. Distribution of the pco Gene Cluster and Associated Genetic Determinants among Swine Escherichia coli from a Controlled Feeding Trial. Genes 2018, 9, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagui, G.S.; Moreira, N.C.; Santos, D.V.; Darini, A.L.C.; Domingo, J.L.; Segura-Muñoz, S.I.; Andrade, L.N. High Occurrence of Heavy Metal Tolerance Genes in Bacteria Isolated from Wastewater: A New Concern? Environ. Res. 2021, 196, 110352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, J.P.R.; Ramos, M.S.; Rosa, R.D.S.; Savazzi, E.A.; Stehling, E.G. Occurrence and Genetic Characteristics of Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli Isolates Co-Harboring Antimicrobial Resistance Genes and Metal Tolerance Genes in Aquatic Ecosystems. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2022, 244, 114003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamathewatta, K.; Bushell, R.; Rafa, F.; Browning, G.; Billman-Jacobe, H.; Marenda, M. Colonization of a Hand Washing Sink in a Veterinary Hospital by an Enterobacter hormaechei Strain Carrying Multiple Resistances to High Importance Antimicrobials. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2020, 9, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasman, H.; Aarestrup, F.M. tcrB, a Gene Conferring Transferable Copper Resistance in Enterococcus faecium: Occurrence, Transferability, and Linkage to Macrolide and Glycopeptide Resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 1410–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arguello, J.M. Identification of Ion-Selectivity Determinants in Heavy-Metal Transport P1B-Type ATPases. J. Membr. Biol. 2003, 195, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasman, H. The tcrB Gene Is Part of the tcrYAZB Operon Conferring Copper Resistance in Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis. Microbiology 2005, 151, 3019–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, E.; Freitas, A.R.; Antunes, P.; Barros, M.; Campos, J.; Coque, T.M.; Peixe, L.; Novais, C. Co-Transfer of Resistance to High Concentrations of Copper and First-Line Antibiotics among Enterococcus from Different Origins (Humans, Animals, the Environment and Foods) and Clonal Lineages. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amachawadi, R.G.; Scott, H.M.; Alvarado, C.A.; Mainini, T.R.; Vinasco, J.; Drouillard, J.S.; Nagaraja, T.G. Occurrence of the Transferable Copper Resistance Gene tcrB among Fecal Enterococci of U.S. Feedlot Cattle Fed Copper-Supplemented Diets. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 4369–4375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Hasman, H.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Alwathnani, H.A.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Rensing, C. Genome Sequences of Copper Resistant and Sensitive Enterococcus faecalis Strains Isolated from Copper-Fed Pigs in Denmark. Stand. Genomic Sci. 2015, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourão, J.; Rae, J.; Silveira, E.; Freitas, A.R.; Coque, T.M.; Peixe, L.; Antunes, P.; Novais, C. Relevance of tcrYAZB Operon Acquisition for Enterococcus Survival at High Copper Concentrations under Anaerobic Conditions. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 560–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, A.; Duarte, B.; Ferreira, C.; Mourão, J.; Ribeiro, S.; Freitas, A.R.; Coque, T.M.; Willems, R.; Corander, J.; Peixe, L.; et al. Enterococcus spp. from Chicken Meat Collected 20 Years Apart Overcome Multiple Stresses Occurring in the Poultry Production Chain: Antibiotics, Copper and Acids. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 384, 109981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, A.; Mourão, J.; Freitas, A.R.; Duarte, B.; Silveira, E.; Sanchez-Valenzuela, A.; Almeida, A.; Baquero, F.; Coque, T.M.; Peixe, L.; et al. Diversity of Metal and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Enterococcus spp. from the Last Century Reflects Multiple Pollution and Genetic Exchange among Phyla from Overlapping Ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 787, 147548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervantes, C.; Gutierrez-Corona, F. Copper Resistance Mechanisms in Bacteria and Fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1994, 14, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Lee, S.; Choi, S. Copper Resistance and Its Relationship to Erythromycin Resistance in Enterococcus Isolates from Bovine Milk Samples in Korea. J. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 540–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, L.; Ye, C.; Yu, X. Co-Selection of Antibiotic Resistance via Copper Shock Loading on Bacteria from a Drinking Water Bio-Filter. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 233, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazhar, S.H.; Li, X.; Rashid, A.; Su, J.; Xu, J.; Brejnrod, A.D.; Su, J.-Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Zhou, S.G.; et al. Co-Selection of Antibiotic Resistance Genes, and Mobile Genetic Elements in the Presence of Heavy Metals in Poultry Farm Environments. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Ma, Y.; Chen, D.; He, J. Field-based Evidence for Copper Contamination Induced Changes of Antibiotic Resistance in Agricultural Soils. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 3896–3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasman, H.; Aarestrup, F.M. Relationship between Copper, Glycopeptide, and Macrolide Resistance among Enterococcus faecium Strains Isolated from Pigs in Denmark between 1997 and 2003. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 454–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Li, S.; Liao, X.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y. Co-Spread of Metal and Antibiotic Resistance within ST3-IncHI2 Plasmids from E. coli Isolates of Food-Producing Animals. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; He, Z.; Kang, Y.; Yu, H.; Wang, J.; Du, P.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, S.; Gao, Z. Complete Nucleotide Sequence of pH11, an IncHI2 Plasmid Conferring Multi-Antibiotic Resistance and Multi-Heavy Metal Resistance Genes in a Clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolate. Plasmid 2016, 86, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.; Tacão, M.; Alves, A.; Henriques, I. Antibiotic and Metal Resistance in a ST395 Pseudomonas aeruginosa Environmental Isolate: A Genomics Approach. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 110, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flach, C.-F.; Pal, C.; Svensson, C.J.; Kristiansson, E.; Östman, M.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Tysklind, M.; Larsson, D.G.J. Does Antifouling Paint Select for Antibiotic Resistance? Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 590–591, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, H.; Kobayashi, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Asako, H.; Aono, R. Overexpression of the robA Gene Increases Organic Solvent Tolerance and Multiple Antibiotic and Heavy Metal Ion Resistance in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 2302–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centre International de Recherche sur le Cancer. A Review of Human Carcinogens; IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, B.K.; Suzuki, K.T. Arsenic Round the World: A Review. Talanta 2002, 58, 201–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, C.; Ji, G.; Ramirez, J.; Silver, S. Resistance to Arsenic Compounds in Microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1994, 15, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páez-Espino, D.; Tamames, J.; De Lorenzo, V.; Cánovas, D. Microbial Responses to Environmental Arsenic. BioMetals 2009, 22, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Caminero, A.; Howe, P.D.; Hughes, M.; Kenyon, E.; Lewis, D.R.; Moore, M.; Aitio, A.; Becking, G.C.; Ng, J. Arsenic and Arsenic Compounds, 2nd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom, D.K. Worldwide Occurrences of Arsenic in Ground Water. Science 2002, 296, 2143–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, N.P.; Galván, A.E.; Yoshinaga-Sakurai, K.; Rosen, B.P.; Yoshinaga, M. Arsenic in Medicine: Past, Present and Future. BioMetals 2023, 36, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Model List of Essential Medicines—22nd List, 2021; WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Argudín, M.A.; Hoefer, A.; Butaye, P. Heavy Metal Resistance in Bacteria from Animals. Res. Vet. Sci. 2019, 122, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachman, K.E.; Graham, J.P.; Price, L.B.; Silbergeld, E.K. Arsenic: A Roadblock to Potential Animal Waste Management Solutions. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 1123–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wen, M.; Wu, L.; Cao, S.; Li, Y. Environmental Behavior and Remediation Methods of Roxarsone. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Withdrawal of Approval of New Animal Drug Applications for Combination Drug Medicated Feeds Containing an Arsenical Drug; No. 39, FDA-2014-N-0002; Department of Health and Human Services, FDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Volume 79.

- Hu, Y.; Cheng, H.; Tao, S.; Schnoor, J.L. China’s Ban on Phenylarsonic Feed Additives, A Major Step toward Reducing the Human and Ecosystem Health Risk from Arsenic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 12177–12187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tóth, G.; Hermann, T.; Silva, M.R.D.; Montanarella, L. Heavy Metals in Agricultural Soils of the European Union with Implications for Food Safety. Environ. Int. 2016, 88, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sager, M. Trace and Nutrient Elements in Manure, Dung and Compost Samples in Austria. Soil Biol. 2007, 39, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachman, K.E.; Raber, G.; Francesconi, K.A.; Navas-Acien, A.; Love, D.C. Arsenic Species in Poultry Feather Meal. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 417–418, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Li, Y.; Yang, M.; Li, W. Content of Heavy Metals in Animal Feeds and Manures from Farms of Different Scales in Northeast China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 2658–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, E. The Behavior of Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Arsenic Influenced by Biochar during Different Manure Composting. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 14484–14490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourão, J.; Rebelo, A.; Ribeiro, S.; Peixe, L.; Novais, C.; Antunes, P. Tolerance to Arsenic Contaminant among Multidrug-resistant and Copper-tolerant Salmonella Successful Clones Is Associated with Diverse ars Operons and Genetic Contexts. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 2829–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Chen, X.; Du, S.; Deng, Z.; Wang, L.; Chen, S. Genetic Mechanisms of Arsenic Detoxification and Metabolism in Bacteria. Curr. Genet. 2019, 65, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, J.; Bertin, P.N. The Microbial Genomics of Arsenic. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2016, 40, 299–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, M.C.; Bertin, P.N.; Heipieper, H.J.; Arsène-Ploetze, F. Bacterial Metabolism of Environmental Arsenic—Mechanisms and Biotechnological Applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 3827–3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Fekih, I.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.P.; Zhao, Y.; Alwathnani, H.A.; Saquib, Q.; Rensing, C.; Cervantes, C. Distribution of Arsenic Resistance Genes in Prokaryotes. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, B.P.; Liu, Z. Transport Pathways for Arsenic and Selenium: A Minireview. Environ. Int. 2009, 35, 512–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oremland, R.S.; Stolz, J.F. The Ecology of Arsenic. Science 2003, 300, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, B.P. Biochemistry of Arsenic Detoxification. FEBS Lett. 2002, 529, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, C.; Lee, S.; Kathariou, S. Dissemination and Conservation of Cadmium and Arsenic Resistance Determinants in Listeria and Other Gram-positive Bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 2020, 113, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novick, R.P.; Roth, C. Plasmid-Linked Resistance to Inorganic Salts in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 1968, 95, 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, R.W.; Baumberg, S. Resistance to Arsenic Compounds Conferred by a Plasmid Transmissible Between Strains of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1973, 115, 459–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zhou, T.; Kuroda, M.; Rosen, B.P. Metalloid Resistance Mechanisms in Prokaryotes. J. Biochem 1998, 123, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-C.; Fu, H.-L.; Lin, Y.-F.; Rosen, B.P. Pathways of Arsenic Uptake and Efflux. Curr. Top. Membr. 2012, 69, 325–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, G.; Silver, S. Reduction of Arsenate to Arsenite by the ArsC Protein of the Arsenic Resistance Operon of Staphylococcus aureus Plasmid P1258. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 9474–9478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.N.; Saltikov, C.W. The ArsR Repressor Mediates Arsenite-Dependent Regulation of Arsenate Respiration and Detoxification Operons of Shewanella Sp. Strain ANA-3. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 6722–6731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleerebezem, M.; Siezen, R.J. Functional Analysis of Three Plasmids from Lactobacillus plantarum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 1223–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Kobayashi, Y. The Ars Operon in the Skin Element of Bacillus subtilis Confers Resistance to Arsenate and Arsenite. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 1655–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaltonen, E.K.J.; Silow, M. Transmembrane Topology of the Acr3 Family Arsenite Transporter From. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008, 1778, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.-L.; Meng, Y.; Gil, J.A.; Mateos, L.M.; Rosen, B.P. Properties of Arsenite Efflux Permeases (Acr3) from Alkaliphilus metalliredigens and Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 19887–19895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, A.; Garrity, G.M. Valid Publication of the Names of Forty-two Phyla of Prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2021, 71, 005056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achour, A.R.; Bauda, P.; Billard, P. Diversity of Arsenite Transporter Genes from Arsenic-Resistant Soil Bacteria. Res. Microbiol. 2007, 158, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, R.; Saier, M.H. Functional Promiscuity of Homologues of the Bacterial ArsA ATPases. Int. J. Microbiol. 2010, 2010, 187373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, S.; Lilley, R.M.; Zhang, R. The Diversity of Membrane Transporters Encoded in Bacterial Arsenic-Resistance Operons. PeerJ 2015, 3, e943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Liu, G.; Rensing, C.; Wang, G. Genes Involved in Arsenic Transformation and Resistance Associated with Different Levels of Arsenic-Contaminated Soils. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.R.; Cook, G.M. Isolation and Characterization of Arsenate-Reducing Bacteria from Arsenic-Contaminated Sites in New Zealand. Curr. Microbiol. 2004, 48, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltikov, C.W.; Olson, B.H. Homology of Escherichia coli R773 arsA, arsB, and arsC Genes in Arsenic-Resistant Bacteria Isolated from Raw Sewage and Arsenic-Enriched Creek Waters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Ward, T.J.; Jima, D.D.; Parsons, C.; Kathariou, S. The Arsenic Resistance-Associated Listeria Genomic Island LGI2 Exhibits Sequence and Integration Site Diversity and a Propensity for Three Listeria monocytogenes Clones with Enhanced Virulence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e01189-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, R.; Card, R.M.; Nunez-Garcia, J.; Mendonça, N.; Da Silva, G.J.; Anjum, M.F. Multidrug-Resistant Salmonella enterica Isolated from Food Animal and Foodstuff May Also Be Less Susceptible to Heavy Metals. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2019, 16, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noormohamed, A.; Fakhr, M. Arsenic Resistance and Prevalence of Arsenic Resistance Genes in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli Isolated from Retail Meats. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2013, 10, 3453–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argudín, M.A.; Lauzat, B.; Kraushaar, B.; Alba, P.; Agerso, Y.; Cavaco, L.; Butaye, P.; Porrero, M.C.; Battisti, A.; Tenhagen, B.-A.; et al. Heavy Metal and Disinfectant Resistance Genes among Livestock-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolates. Vet. Microbiol. 2016, 191, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusick, K.D.; Polson, S.W.; Duran, G.; Hill, R.T. Multiple Megaplasmids Confer Extremely High Levels of Metal Tolerance in Alteromonas Strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 86, e01831-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandegren, L.; Linkevicius, M.; Lytsy, B.; Melhus, Å.; Andersson, D.I. Transfer of an Escherichia coli ST131 Multiresistance Cassette Has Created a Klebsiella pneumoniae-Specific Plasmid Associated with a Major Nosocomial Outbreak. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branchu, P.; Charity, O.J.; Bawn, M.; Thilliez, G.; Dallman, T.J.; Petrovska, L.; Kingsley, R.A. SGI-4 in Monophasic Salmonella Typhimurium ST34 Is a Novel ICE That Enhances Resistance to Copper. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wan, K.; Zeng, J.; Lin, W.; Ye, C.; Yu, X. Co-Selection and Stability of Bacterial Antibiotic Resistance by Arsenic Pollution Accidents in Source Water. Environ. Int. 2020, 135, 105351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cocerva, T.; Cox, S.; Tardif, S.; Su, J.-Q.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Brandt, K.K. Evidence for Co-Selection of Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Mobile Genetic Elements in Metal Polluted Urban Soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 656, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshanee, M.; Chatterjee, S.; Rath, S.; Dash, H.R.; Das, S. Cellular and Genetic Mechanism of Bacterial Mercury Resistance and Their Role in Biogeochemistry and Bioremediation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 126985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nies, D.H. Microbial Heavy-Metal Resistance. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1999, 51, 730–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syversen, T.; Kaur, P. The Toxicology of Mercury and Its Compounds. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2012, 26, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, D.; Hou, D.; Ok, Y.S.; Mulder, J.; Duan, L.; Wu, Q.; Wang, S.; Tack, F.M.G.; Rinklebe, J. Mercury Speciation, Transformation, and Transportation in Soils, Atmospheric Flux, and Implications for Risk Management: A Critical Review. Environ. Int. 2019, 126, 747–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahbub, K.R.; Krishnan, K.; Naidu, R.; Andrews, S.; Megharaj, M. Mercury Toxicity to Terrestrial Biota. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 74, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhoft, R.A. Mercury Toxicity and Treatment: A Review of the Literature. J. Environ. Public Health 2012, 2012, 460508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Cai, Y.; O’Driscoll, N.; Feng, X.; Jiang, G. Overview of Mercury in the Environment. In Environmental Chemistry and Toxicology of Mercury; Liu, G., Cai, Y., O’Driscoll, N., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (Ed.) Beryllium, Cadmium, Mercury and Exposures in the Glass Manufacturing Industry: This Publication Represents the Views and Expert Opinions of an IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Which Met in Lyon, 9–16 February 1993; IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Pirrone, N.; Cinnirella, S.; Feng, X.; Finkelman, R.B.; Friedli, H.R.; Leaner, J.; Mason, R.; Mukherjee, A.B.; Stracher, G.B.; Streets, D.G.; et al. Global Mercury Emissions to the Atmosphere from Anthropogenic and Natural Sources. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010, 10, 5951–5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R.P. Mercury Emissions from Natural Processes and Their Importance in the Global Mercury Cycle. In Mercury Fate and Transport in the Global Atmosphere; Mason, R., Pirrone, N., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, W.F.; Mason, R.P. The Global Mercury Cycle: Oceanic and Anthropogenic Aspects. In Global and Regional Mercury Cycles: Sources, Fluxes and Mass Balances; Baeyens, W., Ebinghaus, R., Vasiliev, O., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1996; pp. 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z. Mercury and Mercury-Containing Preparations: History of Use, Clinical Applications, Pharmacology, Toxicology, and Pharmacokinetics in Traditional Chinese Medicine. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 807807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wujastyk, D. Histories of Mercury in Medicine across Asia and Beyond. Asiat. Stud. Études Asiat. 2015, 69, 819–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, J.G. ‘Two Minutes with Venus, Two Years with Mercury’-Mercury as an Antisyphilitic Chemotherapeutic Agent. J. R. Soc. Med. 1990, 83, 392–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjørklund, G.; Dadar, M.; Mutter, J.; Aaseth, J. The Toxicology of Mercury: Current Research and Emerging Trends. Environ. Res. 2017, 159, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tchounwou, P.B.; Ayensu, W.K.; Ninashvili, N.; Sutton, D. Review: Environmental Exposure to Mercury and Its Toxicopathologic Implications for Public Health. Environ. Toxicol. 2003, 18, 149–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jepson, P.C. Pesticides, Uses and Effects of. In Encyclopedia of Biodiversity; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boening, D.W. Ecological Effects, Transport, and Fate of Mercury: A General Review. Chemosphere 2000, 40, 1335–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marnane, I. Mercury in Europe’s Environment: A Priority for European and Global Action; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, H.; Altaf, A.R. Elemental Mercury (Hg0) Emission, Hazards, and Control: A Brief Review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 5, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gworek, B.; Dmuchowski, W.; Baczewska-Dąbrowska, A.H. Mercury in the Terrestrial Environment: A Review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gworek, B.; Bemowska-Kałabun, O.; Kijeńska, M.; Wrzosek-Jakubowska, J. Mercury in Marine and Oceanic Waters—A Review. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2016, 227, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, G.; Hermann, T.; Szatmári, G.; Pásztor, L. Maps of Heavy Metals in the Soils of the European Union and Proposed Priority Areas for Detailed Assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 565, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettoso, N.; Pittaluga, F.; Predonzani, S.; Zanello, A.; Acquavita, A. Mercury Levels in Sediment, Water and Selected Organisms Collected in a Coastal Contaminated Environment: The Marano and Grado Lagoon (Northern Adriatic Sea, Italy). Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llull, R.M.; Garí, M.; Canals, M.; Rey-Maquieira, T.; Grimalt, J.O. Mercury Concentrations in Lean Fish from the Western Mediterranean Sea: Dietary Exposure and Risk Assessment in the Population of the Balearic Islands. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manceau, A.; Nagy, K.L.; Glatzel, P.; Bourdineaud, J.-P. Acute Toxicity of Divalent Mercury to Bacteria Explained by the Formation of Dicysteinate and Tetracysteinate Complexes Bound to Proteins in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 3612–3623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quig, D. Cysteine Metabolism and Metal Toxicity. Altern. Med. Rev. J. Clin. Ther. 1998, 3, 262–270. [Google Scholar]

- Nies, D.H. Efflux-Mediated Heavy Metal Resistance in Prokaryotes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 27, 313–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Møller, A.K.; Barkay, T.; Hansen, M.A.; Norman, A.; Hansen, L.H.; Sørensen, S.J.; Boyd, E.S.; Kroer, N. Mercuric Reductase Genes (merA) and Mercury Resistance Plasmids in High Arctic Snow, Freshwater and Sea-Ice Brine. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2014, 87, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gionfriddo, C.M.; Tate, M.T.; Wick, R.R.; Schultz, M.B.; Zemla, A.; Thelen, M.P.; Schofield, R.; Krabbenhoft, D.P.; Holt, K.E.; Moreau, J.W. Microbial Mercury Methylation in Antarctic Sea Ice. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 16127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oregaard, G.; Sørensen, S.J. High Diversity of Bacterial Mercuric Reductase Genes from Surface and Sub-Surface Floodplain Soil (Oak Ridge, USA). ISME J. 2007, 1, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobman, J.L.; Crossman, L.C. Bacterial Antimicrobial Metal Ion Resistance. J. Med. Microbiol. 2015, 64, 471–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dash, H.R.; Das, S. Bioremediation of Mercury and the Importance of Bacterial mer Genes. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2012, 75, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkay, T.; Miller, S.M.; Summers, A.O. Bacterial Mercury Resistance from Atoms to Ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 27, 355–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addie, D.D. Metals as Antiseptics and Disinfectants for Use with Animals. MDS Manual, Veterinary Manual. 2022. Available online: https://www.msdvetmanual.com/pharmacology/antiseptics-and-disinfectants/metals-as-antiseptics-and-disinfectants-for-use-with-animals (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Moore, B. A new screen test and selective medium for the rapid detection of epidemic strains of Staph. aureus. Lancet 1960, 276, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, S.; Jernelöv, A. Biological Methylation of Mercury in Aquatic Organisms. Nature 1969, 223, 753–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, E.S.; Barkay, T. The Mercury Resistance Operon: From an Origin in a Geothermal Environment to an Efficient Detoxification Machine. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, I.J.; Roberts, A.P.; Ready, D.; Richards, H.; Wilson, M.; Mullany, P. Linkage of a Novel Mercury Resistance Operon with Streptomycin Resistance on a Conjugative Plasmid in Enterococcus faecium. Plasmid 2005, 54, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narita, M.; Chiba, K.; Nishizawa, H.; Ishii, H.; Huang, C.-C.; Kawabata, Z.; Silver, S.; Endo, G. Diversity of Mercury Resistance Determinants among Bacillus Strains Isolated from Sediment of Minamata Bay. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003, 223, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, H.R.; Sahu, M.; Mallick, B.; Das, S. Functional Efficiency of MerA Protein among Diverse Mercury Resistant Bacteria for Efficient Use in Bioremediation of Inorganic Mercury. Biochimie 2017, 142, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, A.M.A.; Chartone-Souza, E. Operon Mer: Bacterial Resistance to Mercury and Potential for Bioremediation of Contaminated Environments. Genet. Mol. Res. 2003, 2, 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, P.A.; Brown, N.L. Regulation of Transcription in Escherichia coli from the Mer and merR Promoters in the Transposon Tn501. J. Mol. Biol. 1989, 205, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, A.M.; Bruce, K.D.; Strike, P.; Ritchie, D.A. Sequence Conservation between Regulatory Mercury Resistance Genes in Bacteria from Mercury Polluted and Pristine Environments. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1995, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grad, Y.H.; Godfrey, P.; Cerquiera, G.C.; Mariani-Kurkdjian, P.; Gouali, M.; Bingen, E.; Shea, T.P.; Haas, B.J.; Griggs, A.; Young, S.; et al. Comparative Genomics of Recent Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli O104:H4: Short-Term Evolution of an Emerging Pathogen. mBio 2013, 4, e00452-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumiya, H.; Sekizuka, T.; Nakaya, H.; Taguchi, M.; Oguchi, A.; Ichikawa, N.; Nishiko, R.; Yamazaki, S.; Fujita, N.; Watanabe, H.; et al. Whole-Genome Analysis of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium T000240 Reveals the Acquisition of a Genomic Island Involved in Multidrug Resistance via IS 1 Derivatives on the Chromosome. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, M.T.G.; Feil, E.J.; Lindsay, J.A.; Peacock, S.J.; Day, N.P.J.; Enright, M.C.; Foster, T.J.; Moore, C.E.; Hurst, L.; Atkin, R.; et al. Complete Genomes of Two Clinical Staphylococcus aureus Strains: Evidence for the Rapid Evolution of Virulence and Drug Resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 9786–9791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, L.B.; Carias, L.L. Transfer of Tn5385, a Composite, Multiresistance Chromosomal Element from Enterococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 714–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richmond, M.H.; John, M. Co-Transduction by a Staphylococcal Phage of the Genes Responsible for Penicillinase Synthesis and Resistance to Mercury Salts. Nature 1964, 202, 1360–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, C.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Kristiansson, E.; Larsson, D.G.J. Co-Occurrence of Resistance Genes to Antibiotics, Biocides and Metals Reveals Novel Insights into Their Co-Selection Potential. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, D.; Cunningham, M.; Ji, B.; Fekete, F.A.; Parry, E.M.; Clark, S.E.; Zalinger, Z.B.; Gilg, I.C.; Danner, G.R.; Johnson, K.A.; et al. Transferable, Multiple Antibiotic and Mercury Resistance in Atlantic Canadian Isolates of Aeromonas salmonicida Subsp. salmonicida Is Associated with Carriage of an IncA/C Plasmid Similar to the Salmonella enterica Plasmid pSN254. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008, 61, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Blanco, A.; Lemos, M.L.; Osorio, C.R. Integrating Conjugative Elements as Vectors of Antibiotic, Mercury, and Quaternary Ammonium Compound Resistance in Marine Aquaculture Environments. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 2619–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, G.; Si, S.; Wu, X.; Cai, L. Plasmid Genomes Reveal the Distribution, Abundance, and Organization of Mercury-Related Genes and Their Co-Distribution with Antibiotic Resistant Genes in Gammaproteobacteria. Genes 2022, 13, 2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaeta, N.C.; De Carvalho, D.U.; Fontana, H.; Sano, E.; Moura, Q.; Fuga, B.; Munoz, P.M.; Gregory, L.; Lincopan, N. Genomic Features of a Multidrug-Resistant and Mercury-Tolerant Environmental Escherichia coli Recovered after a Mining Dam Disaster in South America. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 823, 153590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Palacios, P.; Delgado-Valverde, M.; Gual-de-Torrella, A.; Oteo-Iglesias, J.; Pascual, Á.; Fernández-Cuenca, F. Co-Transfer of Plasmid-Encoded bla Carbapenemases Genes and Mercury Resistance Operon in High-Risk Clones of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 9231–9242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novais, Â.; Cantón, R.; Valverde, A.; Machado, E.; Galán, J.-C.; Peixe, L.; Carattoli, A.; Baquero, F.; Coque, T.M. Dissemination and Persistence of bla CTX-M-9 Are Linked to Class 1 Integrons Containing CR1 Associated with Defective Transposon Derivatives from Tn 402 Located in Early Antibiotic Resistance Plasmids of IncHI2, IncP1-α, and IncFI Groups. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 2741–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahardoli, A.; Jalilian, F.; Memariani, Z.; Farzaei, M.H.; Shokoohinia, Y. Chapter 26—Analysis of Organic Acids. In Recent Advances in Natural Products Analysis; Sanches Silva, A., Nabavi, S.F., Saeedi, M., Nabavi, S.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 767–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Chauhan, A.K.; Singh, R.B.; Khan, S.; Halabi, G. Organic Acids: Microbial Sources, Production, and Applications. In Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals in Metabolic and Non-Communicable Diseases; Singh, R.B., Watanabe, S., Isaza, A.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, N.; Liu, L. Microbial Response to Acid Stress: Mechanisms and Applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherrington, C.A.; Hinton, M.; Mead, G.C.; Chopra, I. Organic Acids: Chemistry, Antibacterial Activity and Practical Applications. In Advances in Microbial Physiology; Rose, A.H., Tempest, D.W., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991; Volume 32, pp. 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nollet, L.M.L. Food Analysis by HPLC, 2nd ed.; Food Science and Technology; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Anyasi, T.A.; Jideani, A.I.O.; Edokpayi, J.N. Application of Organic Acids in Food Preservation. In Organic Acids: Characteristics, Properties and Synthesis; Vargas, C., Ed.; Nova Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Theron, M.M.; Lues, J.F.R. Organic Acids and Food Preservation; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, C.; Thielmann, J.; Muranyi, P. Chapter 46—Organic Acids: Usage and Potential in Antimicrobial Packaging. In Antimicrobial Food Packaging; Barros-Velázques, J., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricke, S. Perspectives on the Use of Organic Acids and Short Chain Fatty Acids as Antimicrobials. Poult. Sci. 2003, 82, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Regulation (EC) No 1831/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2003 on Additives for Use in Animal Nutrition; OJ L268; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2003; pp. 29–43. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2003:268:0029:0043:EN:PDF (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- European Commission. Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on Food Additives; OJ L 354; pp. 16–33. 31 December 2008. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2008/1333/oj (accessed on 23 August 2019).

- Saleem, K.; Saima; Rahman, A.; Pasha, T.N.; Mahmud, A.; Hayat, Z. Effects of Dietary Organic Acids on Performance, Cecal Microbiota, and Gut Morphology in Broilers. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2020, 52, 3589–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, S.; Haldar, S.; Ghosh, T.K. Comparative Efficacy of an Organic Acid Blend and Bacitracin Methylene Disalicylate as Growth Promoters in Broiler Chickens: Effects on Performance, Gut Histology, and Small Intestinal Milieu. Vet. Med. Int. 2010, 2010, 645150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Wang, J.; Mahfuz, S.; Long, S.; Wu, D.; Gao, J.; Piao, X. Supplementation of Mixed Organic Acids Improves Growth Performance, Meat Quality, Gut Morphology and Volatile Fatty Acids of Broiler Chicken. Animals 2021, 11, 3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.-H.; Choi, M.-R.; Park, J.-W.; Park, K.-H.; Chung, M.-S.; Ryu, S.; Kang, D.-H. Use of Organic Acids to Inactivate Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella Typhimurium, and Listeria monocytogenes on Organic Fresh Apples and Lettuce. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, M293–M298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, C.; Schönknecht, A.; Püning, C.; Alter, T.; Martin, A.; Bandick, N. Effect of Peracetic Acid Solutions and Lactic Acid on Microorganisms in On-Line Reprocessing Systems for Chicken Slaughter Plants. J. Food Prot. 2020, 83, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ). Scientific Opinion on the Evaluation of the Safety and Efficacy of Peroxyacetic Acid Solutions for Reduction of Pathogens on Poultry Carcasses and Meat. EFSA J. 2014, 12, 3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Food Contact Materials, Enzymes and Processing Aids (CEP); Silano, V.; Barat Baviera, J.M.; Bolognesi, C.; Brüschweiler, B.J.; Chesson, A.; Cocconcelli, P.S.; Crebelli, R.; Gott, D.M.; Grob, K.; et al. Evaluation of the Safety and Efficacy of the Organic Acids Lactic and Acetic Acids to Reduce Microbiological Surface Contamination on Pork Carcasses and Pork Cuts. EFSA J. 2018, 16, 5482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgunov, I.G.; Kamzolova, S.V.; Dedyukhina, E.G.; Chistyakova, T.I.; Lunina, J.N.; Mironov, A.A.; Stepanova, N.N.; Shemshura, O.N.; Vainshtein, M.B. Application of Organic Acids for Plant Protection against Phytopathogens. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety. Active Substance: Acetic Acid. EU Pesticides Database. European Commission: Brussels, Belgium. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/plant/pesticides/eu-pesticides-database/start/screen/active-substances/details/1051 (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- Lund, P.A.; De Biase, D.; Liran, O.; Scheler, O.; Mira, N.P.; Cetecioglu, Z.; Fernández, E.N.; Bover-Cid, S.; Hall, R.; Sauer, M.; et al. Understanding How Microorganisms Respond to Acid pH Is Central to Their Control and Successful Exploitation. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 556140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theron, M.M.; Lues, J.F.R. Organic Acids and Meat Preservation: A Review. Food Rev. Int. 2007, 23, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyghebaert, G.; Ducatelle, R.; Immerseel, F.V. An Update on Alternatives to Antimicrobial Growth Promoters for Broilers. Vet. J. 2011, 187, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani-López, E.; García, H.S.; López-Malo, A. Organic Acids as Antimicrobials to Control Salmonella in Meat and Poultry Products. Food Res. Int. 2012, 45, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrington, C.A.; Hinton, M.; Chopra, I. Effect of Short-Chain Organic Acids on Macromolecular Synthesis in Escherichia coli. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1990, 68, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trček, J.; Mira, N.P.; Jarboe, L.R. Adaptation and Tolerance of Bacteria against Acetic Acid. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 6215–6229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.B. Another Explanation for the Toxicity of Fermentation Acids at Low pH: Anion Accumulation versus Uncoupling. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1992, 73, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampf, G. Antiseptic Stewardship: Biocide Resistance and Clinical Implications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitis, M. Disinfection of Wastewater with Peracetic Acid: A Review. Environ. Int. 2004, 30, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Barry, S.; Zhang, Y.; Marmier, N. Review of Advanced Oxidation Processes Based on Peracetic Acid for Organic Pollutants. Water 2022, 14, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, J.A.L.; Godfree, A.F.; Jones, F. Use of Peracetic Acid in Operational Sewage Sludge Disposal to Pasture. Water Sci. Technol. 1985, 17, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Brumelis, D.; Gehr, R. Disinfection of Wastewater by Hydrogen Peroxide or Peracetic Acid: Development of Procedures for Measurement of Residual Disinfectant and Application to a Physicochemically Treated Municipal Effluent. Water Environ. Res. 2002, 74, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauret, C.P. Sanitization. In Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, W.P.; Carlos, T.D.; Cavallini, G.S.; Pereira, D.H. Peracetic Acid: Structural Elucidation for Applications in Wastewater Treatment. Water Res. 2020, 168, 115143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, P.; Tramonti, A.; De Biase, D. Coping with Low pH: Molecular Strategies in Neutralophilic Bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 38, 1091–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slonczewski, J.L.; Fujisawa, M.; Dopson, M.; Krulwich, T.A. Cytoplasmic pH Measurement and Homeostasis in Bacteria and Archaea. In Advances in Microbial Physiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 55, pp. 1–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanjee, U.; Houry, W.A. Mechanisms of Acid Resistance in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 67, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tang, H.; Lin, Z.; Xu, P. Mechanisms of Acid Tolerance in Bacteria and Prospects in Biotechnology and Bioremediation. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 1484–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, R.; Yu, R.; Guo, T.; Kong, J. Molecular Analysis of Glutamate Decarboxylases in Enterococcus avium. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 691968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castanie-Cornet, M.-P.; Penfound, T.A.; Smith, D.; Elliott, J.F.; Foster, J.W. Control of Acid Resistance in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 3525–3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, P.; Ma, D.; Chen, Y.; Guo, Y.; Chen, G.-Q.; Deng, H.; Shi, Y. L-Glutamine Provides Acid Resistance for Escherichia coli through Enzymatic Release of Ammonia. Cell Res. 2013, 23, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, M.P.; Kenyon, W.J. Resistance and Survival Strategies of Salmonella enterica to Environmental Stresses. Food Res. Int. 2012, 45, 455–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.I.; Matos, D.; San Romão, M.V.; Barreto Crespo, M.T. Dual Role for the Tyrosine Decarboxylation Pathway in Enterococcus faecium E17: Response to an Acid Challenge and Generation of a Proton Motive Force. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.F.; Maier, R.J. Ammonium Metabolism Enzymes Aid Helicobacter pylori Acid Resistance. J. Bacteriol. 2014, 196, 3074–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y. F1F0-ATPase Functions Under Markedly Acidic Conditions in Bacteria. In Regulation of Ca2+-ATPases, V-ATPases and F-ATPases; Chakraborti, S., Dhalla, N.S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.; Wang-Kan, X.; Neuberger, A.; Van Veen, H.W.; Pos, K.M.; Piddock, L.J.V.; Luisi, B.F. Multidrug Efflux Pumps: Structure, Function and Regulation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Yu, Y.; Fu, C.; Chen, F. Bacterial Acid Resistance Toward Organic Weak Acid Revealed by RNA-Seq Transcriptomic Analysis in Acetobacter pasteurianus. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Shao, Y.; Chen, F. Overview on Mechanisms of Acetic Acid Resistance in Acetic Acid Bacteria. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 31, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Cui, Y.; Qu, X. Mechanisms and Improvement of Acid Resistance in Lactic Acid Bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 2018, 200, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Shao, Y.; Chen, T.; Chen, W.; Chen, F. Global Insights into Acetic Acid Resistance Mechanisms and Genetic Stability of Acetobacter pasteurianus Strains by Comparative Genomics. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 18330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seixas, A.F.; Quendera, A.P.; Sousa, J.P.; Silva, A.F.Q.; Arraiano, C.M.; Andrade, J.M. Bacterial Response to Oxidative Stress and RNA Oxidation. Front. Genet. 2022, 12, 821535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]