A New “Non-Traditional” Antibacterial Drug Fluorothiazinone—Clinical Research in Patients with Complicated Urinary Tract Infections

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Primary Outcome

2.2. Secondary Outcomes

2.3. Additional Outcomes

2.4. Safety Report

3. Discussion

3.1. Limitations

3.2. Interpretation

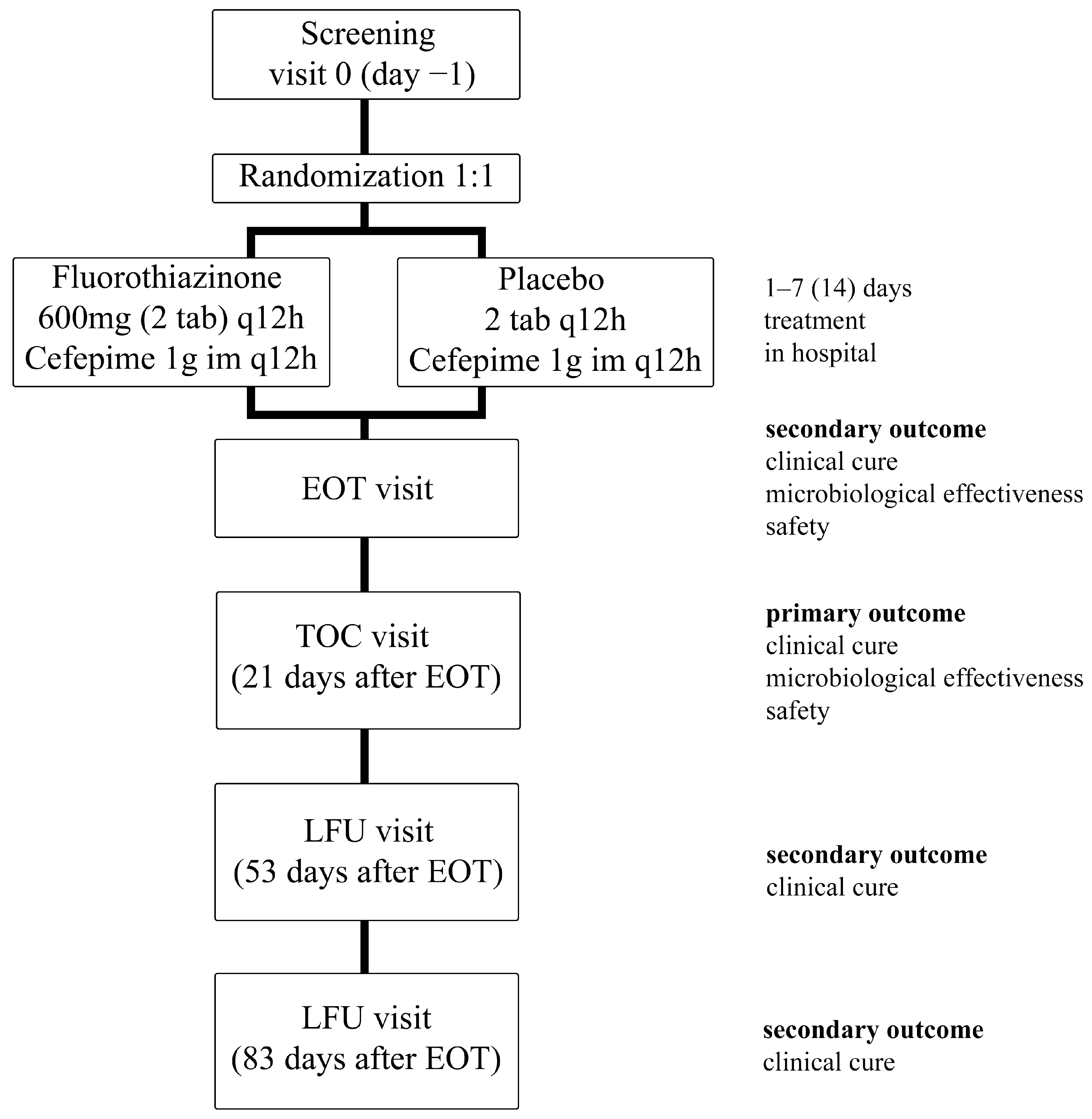

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Trial Design

4.2. Participants

4.3. Interventions

4.4. Outcomes

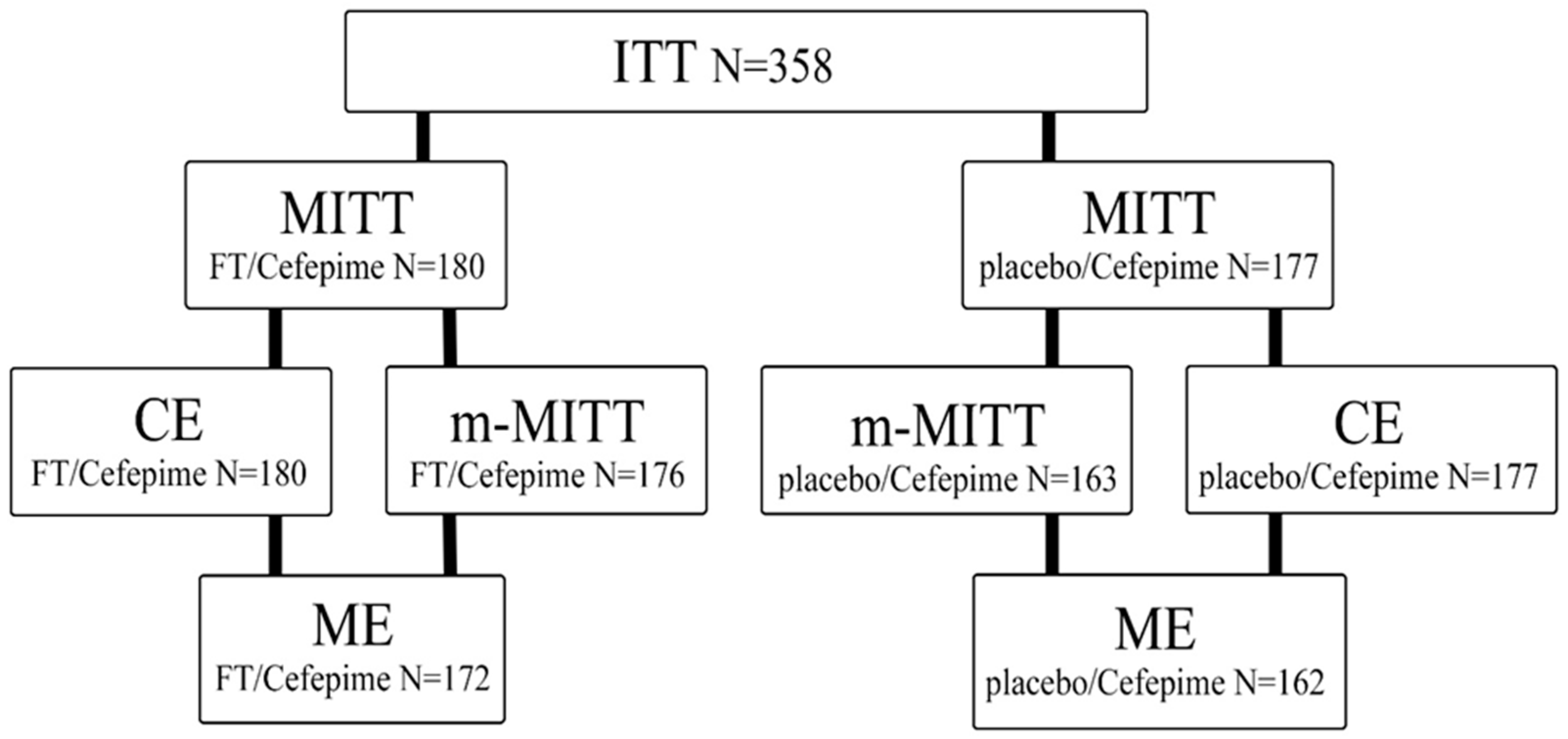

4.4.1. Study Populations

- MITT—patients who met the ITT (intent-to-treat) criterion and received any amount of the drug specified by the study protocol;

- m-MITT—included patients who met the MITT criteria and who had any pathogenic microorganism detected in their urine, including P. aeruginosa, E. coli, and Enterococcus spp., at baseline;

- The population of patients eligible for CE included patients who met the MITT criteria and met the criteria for suitability evaluation (met the basic inclusion criteria, had no non-inclusion criteria, received ≥80% of the estimated doses, and lacked any other factors that could interfere with the efficacy assessment);

- The population of patients suitable for ME included patients who met the m-MITT criteria and CE criteria and who had a properly collected urine sample for culture and a suitable urine culture result for evaluation at the EOT or the TOC visits.

4.4.2. Descriptions of Responses

- -

- clinical cure—compliance with the criteria of clinical cure and absence of signs of cUTIs at visit;

- -

- recurrence—clinical cure after completion of therapy at the EOT visit, but appearance of new signs and symptoms of complicated UTIs at the TOC visit, causing the patient to be in need for antibiotic therapy for complicated UTIs;

- -

- clinical inefficacy—the symptoms of the complicated UTI that were present at the time of inclusion in the study were not completely resolved at the EOT and TOC visits, or new symptoms developed and antibiotic therapy beyond the scope of the study is required, or death occurred;

- -

- clinically uncertain response—there are insufficient data to determine cure or inefficacy to the patient.

- -

- microbiological eradication—microbiological eradication;

- -

- presumed sustained microbiological eradication—urine culture at the TOC visit was not performed or was lost, but the patient meets the clinical criteria for clinical cure;

- -

- microbiological recurrence—urine culture performed at the TOC visit showed ≥104 CFU/mL of any of pathogenic bacteria identified at baseline;

- -

- microbiologically uncertain response—there was no urine culture at the TOC visit, or urine culture was unable to be interpreted for any reason at the follow-up visit, or urine culture was recognized as contaminated.

- colonization—isolation of a new pathogenic bacteria at a concentration of ≥105 CFU/mL (different from pathogenic microorganisms found at baseline) from urine culture of the patients who met the criteria of clinical cure.

4.4.3. Descriptions of Outcomes

- proportion of patients with an overall outcome in the form of a cure at TOC visit in the group of patients meeting the m-MITT criterion, i.e., having isolated pathogen (including P. aeruginosa, E. coli, and Enterococcus spp.) in urine at baseline;

- proportion of patients with a clinical cure response at TOC visit in the population of patients treated with drugs specified by the study protocol, i.e., meeting the MITT criterion; in the group of patients with an isolated pathogen (including P. aeruginosa, E. coli, and Enterococcus spp.) in urine at baseline, i.e., corresponding to the m-MITT criterion; populations of patients suitable for clinical evaluation (CE); populations of patients suitable for microbiological evaluation (ME);

- proportion of patients with a clinical response in the form of recurrence based on combined data from LFU visits in the patient population suitable for clinical evaluation (CE);

- proportion of patients with a response in the form of microbiological eradication for all isolated pathogens in the MITT, m-MITT, and ME populations at the EOT visit and at the TOC visit;

- proportion of patients with a microbiological response in the form of recurrences and colonization, represented by groups, in the ME population at the TOC visit;

- frequency of withdrawal from the study due to insufficient efficacy of therapy.

4.5. Sample Size Calculation

4.6. Randomization

4.7. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Antibacterial Agents in Clinical and Preclinical Development: An Overview and Analysis. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240047655 (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Zigangirova, N.; Lubenec, N.; Zaitsev, A.; Pushkar, D. Antibacterial agents reducing the risk of resistance development. CMAC 2021, 23, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theuretzbacher, U.; Piddock, L.J.V. Non-traditional antibacterial therapeutic options and challenges. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Totsika, M. Benefits and challenges of antivirulence antimicrobials at the dawn of the post-antibiotic era. Drug Deliv. Lett. 2016, 6, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, S.W.; Cheung, G.Y.C.; Otto, M. Different drugs for bad bugs: Antivirulence strategies in the age of antibiotic resistance. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Outterson, K.; Rex, J.H. Evaluating for-profit public benefit corporations as an additional structure for antibiotic development and commercialization. Transl. Res. 2020, 220, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Provenzani, A.; Hospodar, A.R.; Meyer, A.L.; Vinci, D.L.; Hwang, E.Y.; Butrus, C.M.; Polidori, P. Multidrug-resistant gram-negative organisms: A review of recently approved antibiotics and novel pipeline agents. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2020, 42, 1016–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroleva, E.A.; Kobets, N.V.; Zayakin, E.S.; Luyksaar, S.I.; Shabalina, L.A.; Zigangirova, N.A. Small molecule inhibitor of type three secretion suppresses acute and chronic Chlamydia trachomatis infection in a novel urogenital Chlamydia model. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 484853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheremet, A.B.; Zigangirova, N.A.; Zayakin, E.S.; Luyksaar, S.I.; Kapotina, L.N.; Nesterenko, L.N.; Kobets, N.V.; Gintsburg, A.L. Small molecule inhibitor of type three secretion system belonging to a class 2,4-disubstituted-4H-[1,3,4]-thiadiazine-5-ones improves survival and decreases bacterial loads in an airway Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in mice. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 5810767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigangirova, N.A.; Nesterenko, L.N.; Sheremet, A.B.; Soloveva, A.; Luyksaar, S.; Zayakin, E.S.; Balunets, D.; Gintsburg, A.L. Fluorothiazinon, a small-molecular inhibitor of T3SS, suppresses salmonella oral infection in mice. J. Antibiot. 2021, 74, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondareva, N.E.; Soloveva, A.V.; Sheremet, A.B.; Koroleva, E.A.; Kapotina, L.N.; Morgunova, E.Y.; Luyksaar, S.I.; Zayakin, E.S.; Zigangirova, N.A. Preventative treatment with Fluorothiazinon suppressed Acinetobacter baumannii-associated septicemia in mice. J. Antibiot. 2022, 75, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroleva, E.A.; Soloveva, A.V.; Morgunova, E.Y.; Kapotina, L.N.; Luyksaar, S.V.; Bondareva, N.E.; Nelubina, S.A.; Lubenec, N.L.; Zigangirova, N.A.; Gintsburg, A.L. Fluorothiazinon inhibits the virulence factors of uropathogenic Escherichia coli involved in the development of urinary tract infection. J. Antibiot. 2023, 76, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsarenko, S.V.; Zigangirova, N.A.; Soloveva, A.V.; Bondareva, N.E.; Koroleva, E.A.; Sheremet, A.B.; Kapotina, L.N.; Shevlyagina, N.V.; Andreevskaya, S.G.; Zhukhovitsky, V.G.; et al. A novel antivirulent compound fluorothiazinone inhibits Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilm in vitro and suppresses model pneumonia. J. Antibiot. 2023, 76, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawara, H. Possible drugs for the treatment of bacterial infections in the future: Anti-virulence drugs. J. Antibiot. 2021, 74, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savitskii, M.V.; Moskaleva, N.E.; Brito, A.; Markin, P.A.; Zigangirova, N.A.; Soloveva, A.V.; Sheremet, A.B.; Bondareva, N.E.; Lubenec, N.L.; Tagliaro, F.; et al. Pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution, bioavailability and excretion of the anti-virulence drug Fluorothiazinon in rats and rabbits. J. Antibiot. 2024, 77, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govindarajan, D.K.; Kandaswamy, K. Virulence factors of uropathogens and their role in host pathogen interactions. Cell Surf. 2022, 8, 100075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.M.; Lowder, J.L. Diagnosis and treatment of urinary tract infections across age groups. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 219, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.; Gomolin, I.H. Cefepime neurotoxicity: Case report, pharmacokinetic considerations, and literature review. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2006, 26, 1169–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pais, G.M.; Chang, J.; Barreto, E.F.; Stitt, G.; Downes, K.J.; Alshaer, M.H.; Lesnicki, E.; Panchal, V.; Bruzzone, M.; Bumanglag, A.; et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cefepime. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2022, 61, 929–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lüthje, P.; Brauner, A. Virulence factors of uropathogenic E. coli and their interaction with the host. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 2014, 65, 337–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, J.J.; Mulvey, M.A.; Schilling, J.D.; Pinkner, J.S. Type 1 pilus-mediated bacterial invasion of bladder epithelial cells. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 2803–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, M.P.; Aleandri, M.; Marazzato, M.; Conte, A.L.; Ambrosi, C.; Nicoletti, M.; Zagaglia, C.; Gambara, G.; Palombi, F.; De Cesaris, P.; et al. The adherent/invasive Escherichia coli strain LF82 invades and persists in human prostate cell line RWPE-1, activating a strong inflammatory response. Infect. Immun. 2016, 84, 3105–3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patangia, D.; Ryan, C.A.; Dempsey, E.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. Impact of antibiotics on the human microbiome and consequences for host health. Microbiologyopen 2022, 11, e1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Zyl, K.N.; Matukane, S.R.; Hamman, B.L.; Whitelaw, A.C.; Newton-Foot, M. Effect of antibiotics on the human microbiome: A systematic review. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2022, 59, 106502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, P.; Curtis, N. The effect of antibiotics on the composition of the intestinal microbiota—A systematic review. J. Infect. 2019, 79, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mühlen, S.; Dersch, P. Anti-virulence strategies to target bacterial infections. In How to Overcome the Antibiotic Crisis: Facts, Challenges, Technologies and Future Perspectives; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 147–183. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, C.; Huang, X.; Wang, Q.; Yao, D.; Lu, W. Virulence factors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and antivirulence strategies to combat its drug resistance. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 926758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascioferro, S.; Totsika, M.; Schillaci, D. Sortase A: An ideal target for anti-virulence drug development. Microb. Pathog. 2014, 77, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Prioritization of Pathogens to Guide Discovery, Research and Development of New Antibiotics for Drug-Resistant Bacterial Infections, including Tuberculosis. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-EMP-IAU-2017.12 (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Reveiz, L.; Chan, A.-W.; Krleža-Jerić, K.; Granados, C.E.; Pinart, M.; Etxeandia, I.; Rada, D.; Martinez, M.; Bonfill, X.; Cardona, A.F. Reporting of methodologic information on trial registries for quality assessment: A study of trial records retrieved from the WHO search portal. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, S.-C.; Shao, J.; Wang, H.; Lokhnygina, Y. Sample Size Calculations in Clinical Research; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghaei, M. An overview of randomization and minimization programs for randomized clinical trials. J. Med. Signals Sens. 2011, 1, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puza, B.; O’Neill, T. Generalised Clopper–Pearson confidence intervals for the binomial proportion. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2006, 76, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | N, Patients | Absolute Frequency with Cure, Patients | Means, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Frequency | LL (Lower Limit) 95% of CI | UL (Upper Limit) 95% of CI | |||

| FT/Cefepime | 180 | 136 | 75.6 | 68.6 | 81.6 |

| Placebo/Cefepime | 177 | 90 | 50.8 | 43.0 | 58.1 |

| Response/Population | n/N (% (CI)) FT/Cefepime | n/N (% (CI)) Placebo/Cefepime | p 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 21 after the last antibiotic dose | |||

| Overall success/m-MITT | 135/176 (76.7 (95% CI: 69.7–82.7)) | 90/163 (55.2 (95% CI: 47.2–63.0)) | 0.0001 * |

| Clinical cure/MITT | 159/180 (89.2 (95% CI: 83.7–93.4)) | 110/163 (67.5 (95% CI: 59.7–74.6)) | 0.0001 * |

| Clinical cure/m-MITT | 157/176 (89.2 (95% CI: 83.7–93.4)) | 110/163 (67.5 (95% CI: 59.7–73.6)) | 0.0001 * |

| Clinical cure/CE (clinical evaluation) | 159/180 (88.3 (95% CI: 82.7–92.6)) | 123/177 (69.5 (95% CI: 62.1–76.2)) | 0.0001 * |

| Clinical cure/ME (microbiological evaluation) | 153/172 (89.0 (95% CI: 83.3–93.2)) | 109/162 (67.3 (95% CI: 59.5–74.4)) | 0.0001 * |

| Microbiological efficiency/m-MITT | 134/176 (76.1 (95% CI: 69.1–82.2%)) | 102/163 (62.6 (95% CI: 54.7–70.0%)) | 0.009 * |

| Microbiological efficiency/ME | 134/172 (77.9 (95% CI: 71.0–83.9%)) | 102/162 (63.0 (95% CI: 55.3–70.6)) | 0.004 * |

| Recurrence/MITT | 9/180 (5 (95% CI: 2.3–9.3%)) | 29/177 (16.4 (95% CI: 11.3–22.7%)) | 0.001 * |

| Day 53 after the last antibiotic dose | |||

| Recurrence/CE | 2/179 (1.1 (95% CI: 0.1–4.0)) | 28/175 (16.0 (95% CI: 10.9–22.3)) | <0.0001 * |

| Day 83 after the last antibiotic dose | |||

| Recurrence/CE | 3/178 (1.7 (95% CI: 0.3–4.8)) | 14/175 (8.0 (95% CI: 4.4–13.1)) | 0.012 * |

| Day 53+ 83 after the last antibiotic dose | |||

| Recurrence/CE | 5/179 (2.8 (95% CI: 0.9–6.4)) | 38/175 (21.7 (95% CI: 15.8–28.6)) | <0.0001 * |

| Response | Clinical Cure | Clinically Uncertain Outcome | Clinical Inefficacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| The EOT visit | |||

| Microbiological eradication | 159 | 4 | 0 |

| Colonization | 16 | 2 | 0 |

| Microbiological persistence | 14 | 2 | 0 |

| The TOC visit | |||

| Microbiological eradication | 146 | 3 | 2 |

| Colonization | 12 | 0 | 7 |

| Microbiological recurrence | 12 | 3 | 12 |

| Pathogens | Eradication at the EOT Visit | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n/N (%) FT/Cefepime | n/N (%) Placebo/Cefepime | Treatment Difference, % | |

| Enterobacter | 11/13–84.6 | 9/11–81.8 | 2.8 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 58/70–82.9 | 35/50–70 | 12.9 |

| Escherichia coli | 105/109–96.3 | 79/93–84.9 | 11.4 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 47/49–95.9 | 32/39–82.1 | 13.8 |

| Proteus spp. | 12/14–85.7 | 12/16–75.0 | 10.7 |

| Pseudomonas spp. | 11/12–91.7 | 11/16–68.8 | 22.9 |

| Staphylococcus | 24/29–82.8 | 22/32–68.8 | 14 |

| Streptococcus | 15/18–83.3 | 10/17–58.8 | 24.5 |

| Eradication at the TOC visit | |||

| Acinetobacter spp. | 3/4–75.0 | 4/8–50 | 25 |

| Enterobacter spp. | 11/12–91.7 | 7/11–63.6 | 28.1 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 54/70–77.1 | 33/61–54.1 | 23 |

| Escherichia coli | 94/109–86.2 | 70/93–75.3 | 10.9 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 42/49–85.7 | 27/39–69.2 | 16.5 |

| Proteus spp. | 13/14–92.9 | 14/16–87.5 | 5.4 |

| Pseudomonas spp. | 10/12–83.3 | 12/16–75 | 8.3 |

| Staphylococcus spp. | 25/29–86.2 | 23/32–71.9 | 14.3 |

| Streptococcus spp. | 17/18–94.4 | 14/17–82.4 | 12 |

| SOC MedDRA | FT/Cefepime, N = 180 n (%) | Placebo/Cefepime, N = 177 n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with any treatment-emergent adverse event | 37 (58.7) | 27 (41.3) |

| Headache | 6 (3.3) | 5 (2.8) |

| Blood creatinine increased | 6(3.3) | 1 (0.6) |

| Blood urea increased | 4 (2.2) | 2 (1.1) |

| Cough | 1 (0.6) | 3 (1.7) |

| Nasal congestion or rhinorrhea | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) |

| Diarrhea | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) |

| Kidney and urinary disorders | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) |

| Creatine phosphokinase increased | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.1) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.1) |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate increased | 2 (1.1) | 0 |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 2 (1.1) | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) |

| Blood bilirubin increased | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) |

| Kidney and urinary disorders | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) |

| Hypotension | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) |

| Sleep disorder | 1 (0.6) | 0 |

| Bradycardia or tachycardia | 1 (0.6) | 0 |

| Infections and infestations | 1 (0.6) | 0 |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Nausea | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Increased eosinophil count | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Total protein decreased | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zigangirova, N.A.; Lubenec, N.L.; Beloborodov, V.B.; Sheremet, A.B.; Nelyubina, S.A.; Bondareva, N.E.; Zakharov, K.A.; Luyksaar, S.I.; Zolotov, S.A.; Levchenko, E.U.; et al. A New “Non-Traditional” Antibacterial Drug Fluorothiazinone—Clinical Research in Patients with Complicated Urinary Tract Infections. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 476. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13060476

Zigangirova NA, Lubenec NL, Beloborodov VB, Sheremet AB, Nelyubina SA, Bondareva NE, Zakharov KA, Luyksaar SI, Zolotov SA, Levchenko EU, et al. A New “Non-Traditional” Antibacterial Drug Fluorothiazinone—Clinical Research in Patients with Complicated Urinary Tract Infections. Antibiotics. 2024; 13(6):476. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13060476

Chicago/Turabian StyleZigangirova, Nailya A., Nadezda L. Lubenec, Vladimir B. Beloborodov, Anna B. Sheremet, Stanislava A. Nelyubina, Nataliia E. Bondareva, Konstantin A. Zakharov, Sergey I. Luyksaar, Sergey A. Zolotov, Evgenia U. Levchenko, and et al. 2024. "A New “Non-Traditional” Antibacterial Drug Fluorothiazinone—Clinical Research in Patients with Complicated Urinary Tract Infections" Antibiotics 13, no. 6: 476. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13060476

APA StyleZigangirova, N. A., Lubenec, N. L., Beloborodov, V. B., Sheremet, A. B., Nelyubina, S. A., Bondareva, N. E., Zakharov, K. A., Luyksaar, S. I., Zolotov, S. A., Levchenko, E. U., Luyksaar, S. V., Koroleva, E. A., Fedina, E. D., Simakova, Y. V., Pushkar, D. Y., & Gintzburg, A. L. (2024). A New “Non-Traditional” Antibacterial Drug Fluorothiazinone—Clinical Research in Patients with Complicated Urinary Tract Infections. Antibiotics, 13(6), 476. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13060476