Effect of Antibiotics on Clinical and Laboratory Outcomes After Mandibular Third Molar Surgery: A Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

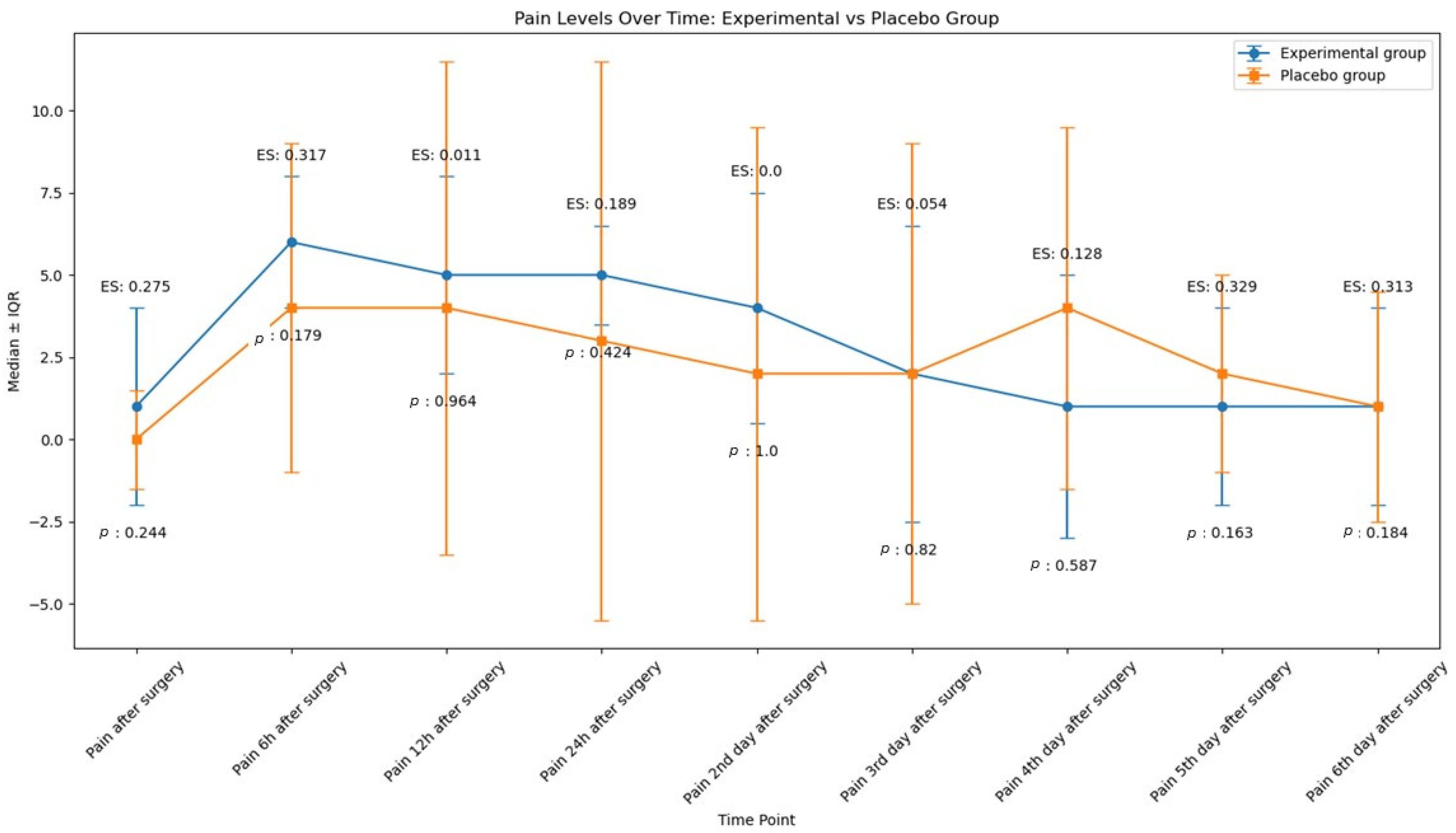

2.1. Pain

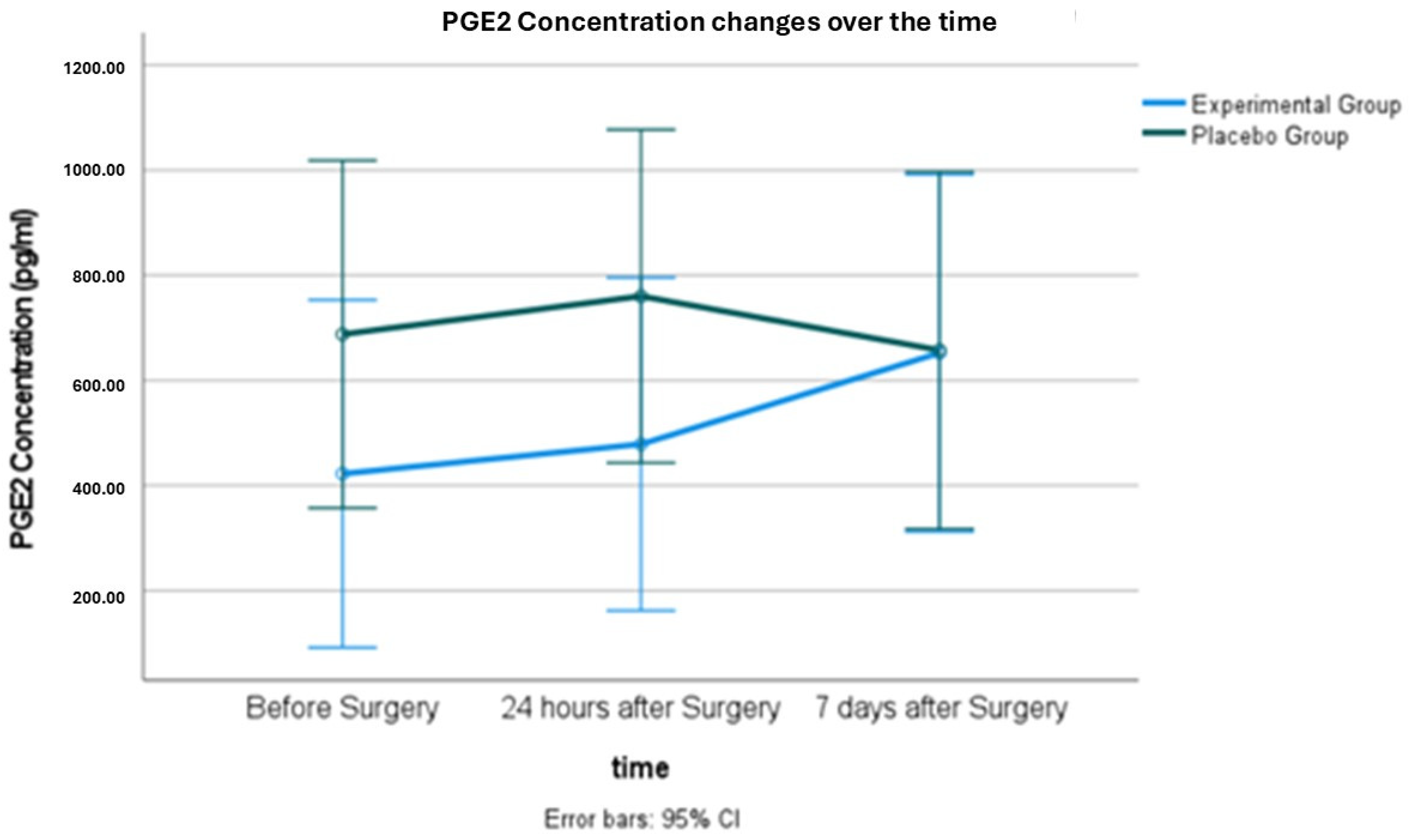

2.2. Salivary PGE2 Concentration

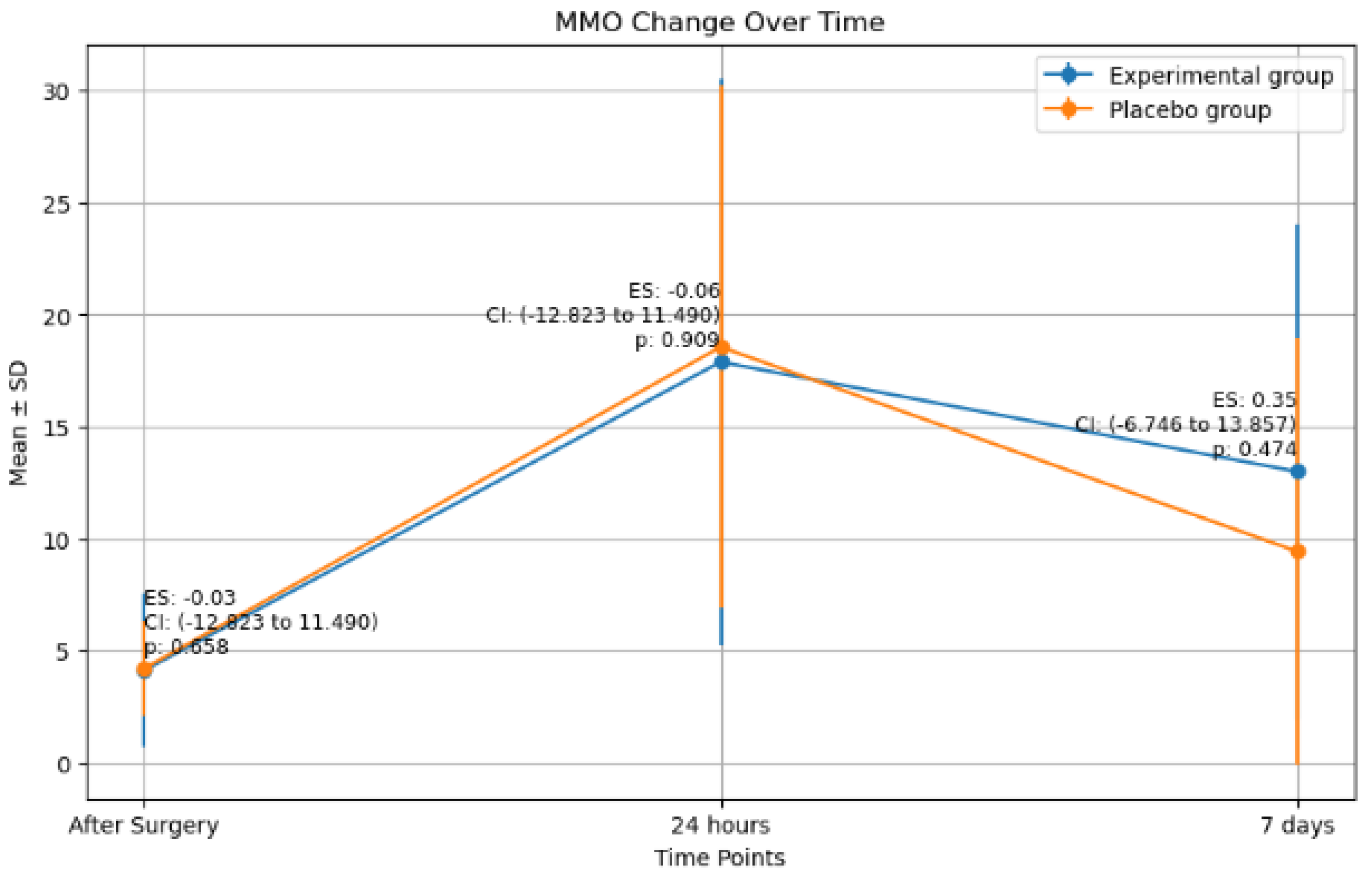

2.3. Maximim Mouth Oppening (MMO) Changes

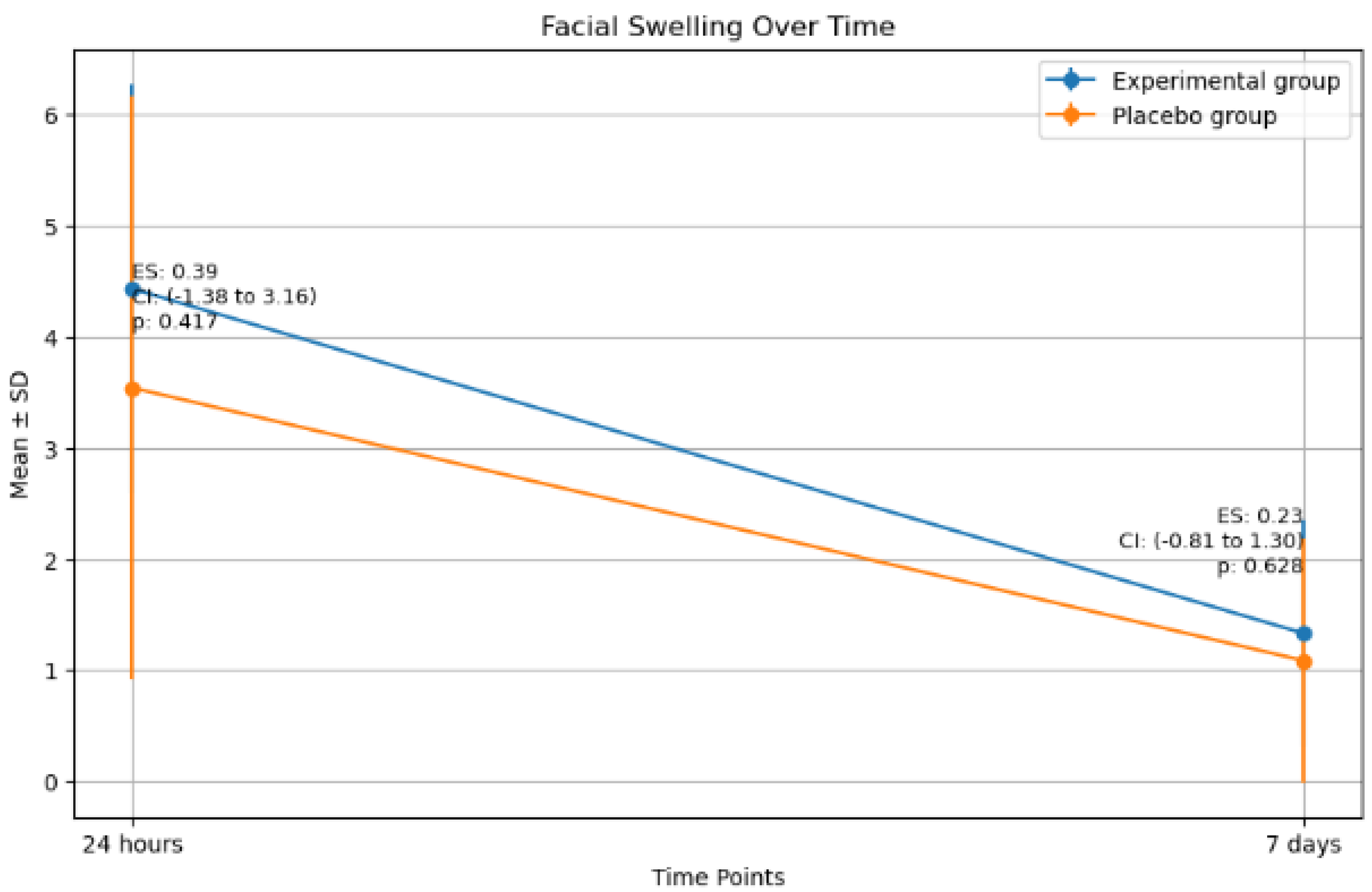

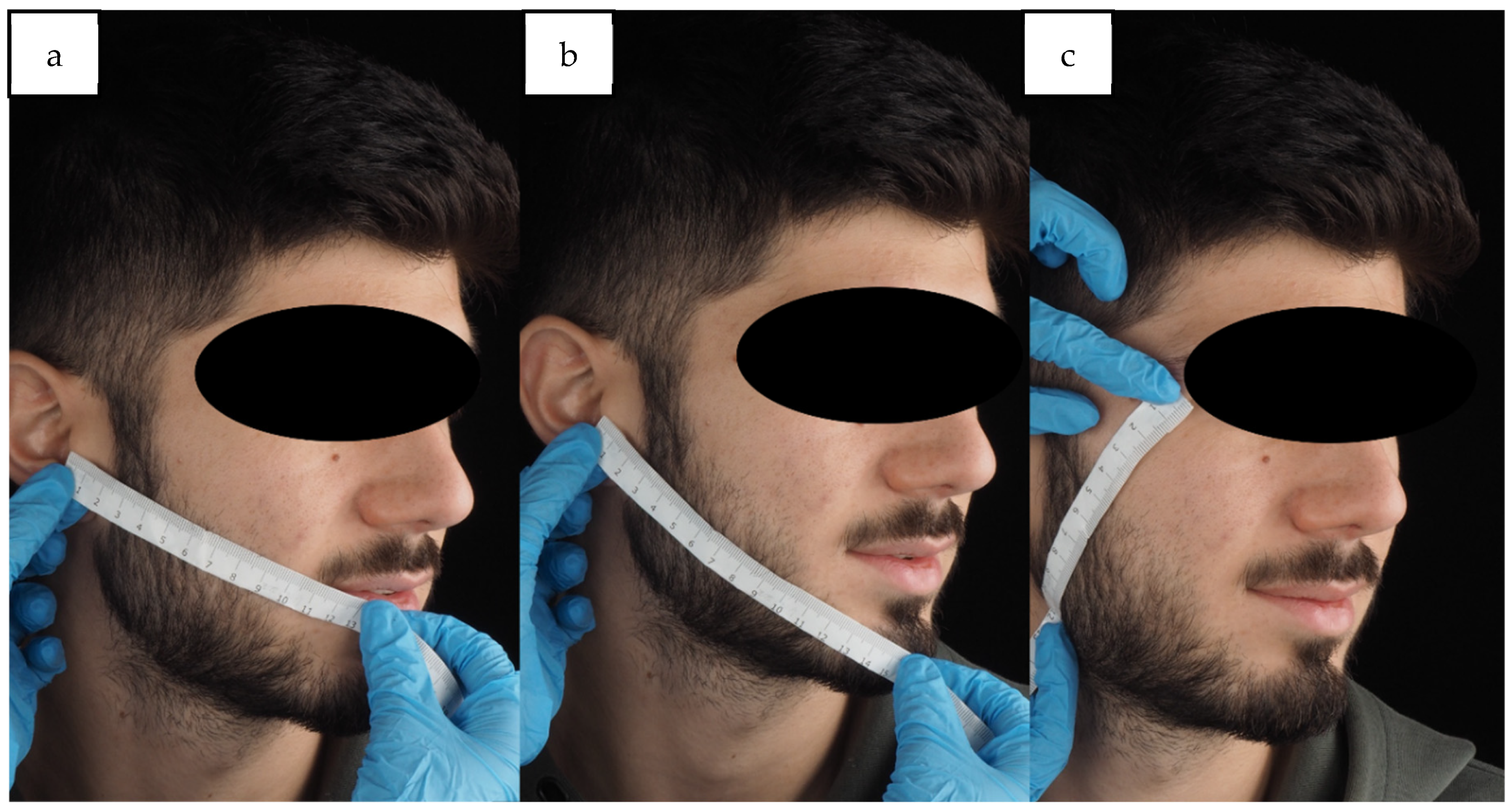

2.4. Facial Swelling

2.5. Correlation Between Primary and Secondary Outcomes

2.6. Study Power Calculation

3. Discussion

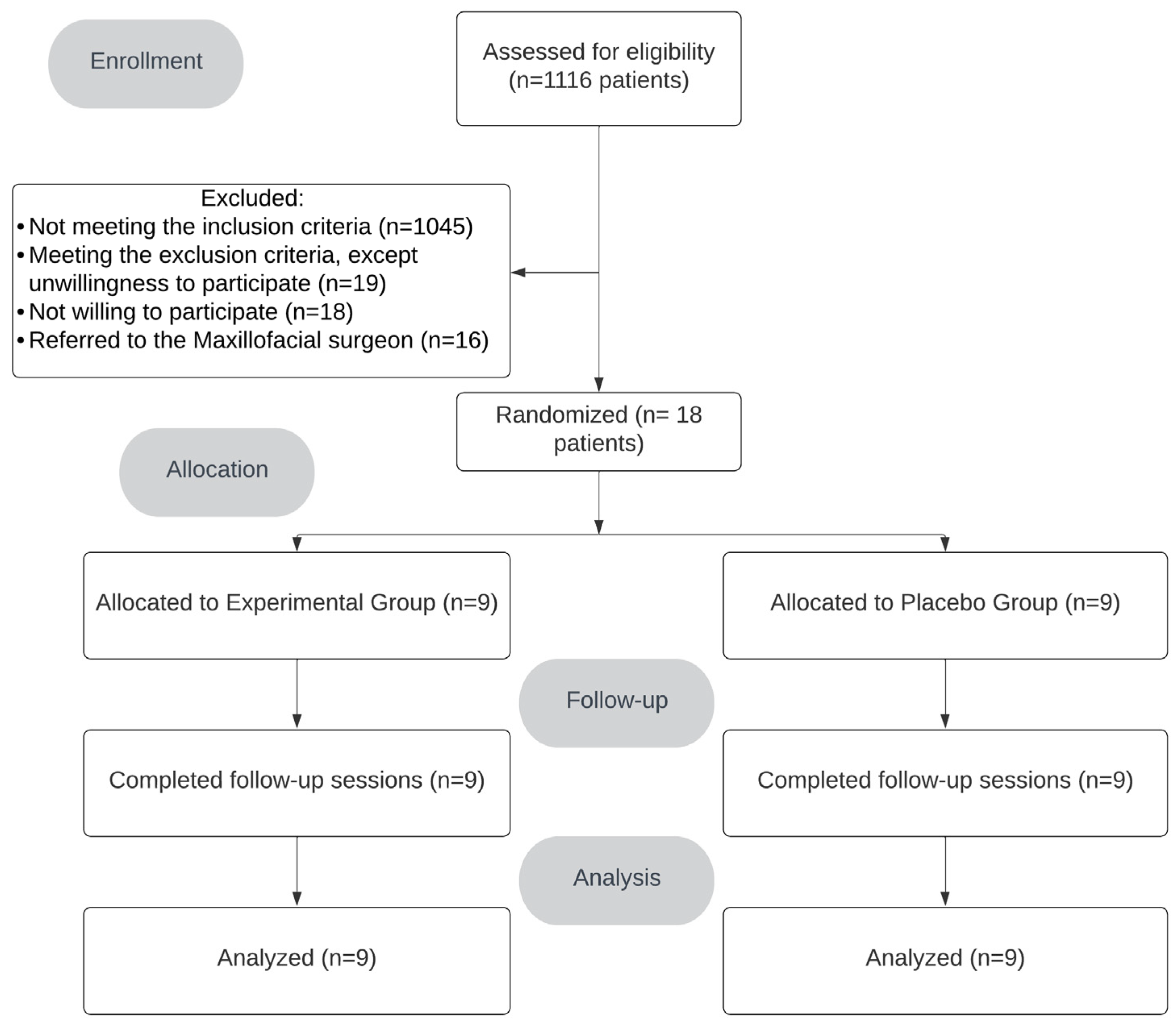

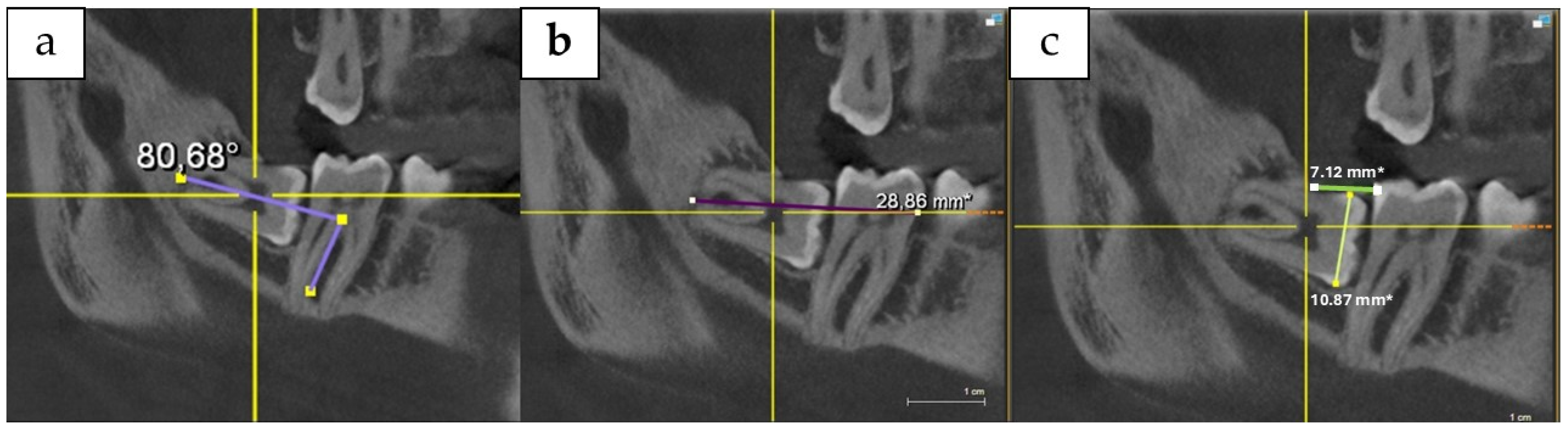

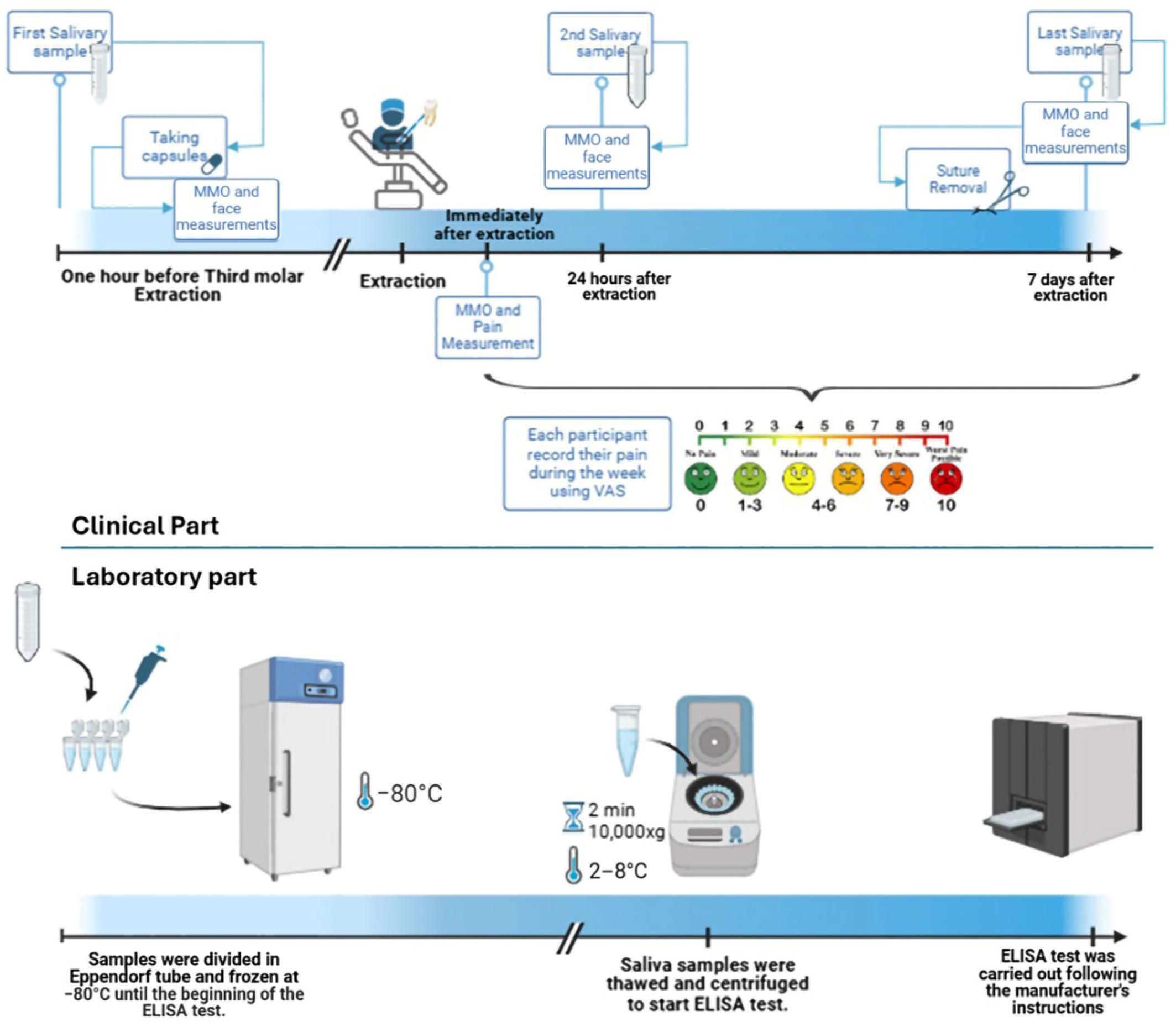

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| PG | Placebo Group |

| EG | Experimental Group |

| Standard Deviation | |

| DI | Difficulty Index |

| MMO | Maximum Mouth Opening |

| CC | Correlation Coefficient |

| PC | Pearson Correlation |

References

- Rohit, S.; Reddy, B.P. Efficacy of postoperative prophylactic antibiotic therapy in third molar surgery. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. JCDR 2014, 8, Zc14–Zc16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, N.; Bakathir, A.; Pasha, M.; Al-Sudairy, S. Complications of Third Molar Extraction: A retrospective study from a tertiary healthcare centre in Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2019, 19, e230–e235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cei, S.; D’Aiuto, F.; Duranti, E.; Taddei, S.; Gabriele, M.; Ghiadoni, L.; Graziani, F. Third Molar Surgical Removal: A Possible Model of Human Systemic Inflammation? A Preliminary Investigation. Eur. J. Inflamm. 2012, 10, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, P.; Reebye, U.; Nadershah, M.; Cottrell, D. Efficacy of anti-inflammatory drugs in third molar surgery: A randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 42, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graziani, F.; D’Aiuto, F.; Gennai, S.; Petrini, M.; Nisi, M.; Cirigliano, N.; Landini, L.; Bruno, R.M.; Taddei, S.; Ghiadoni, L. Systemic Inflammation after Third Molar Removal: A Case-Control Study. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, H.; Zhu, S.; Safi, L.; Alkourdi, M.; Nguyen, B.H.; Upadhyay, A.; Tran, S.D. Salivary Diagnostics in Pediatrics and the Status of Saliva-Based Biosensors. Biosensors 2023, 13, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandini, R.V.; Ghosh, S.; Sharma, S.; Kumari, A.; Rathi, V.; Srivastava, P. Correlation Between Salivary Amylase A Biomarker and Postoperative Pain After Third Molar Surgery. J. Pharm. Negat. Results 2022, 13, 2671–2677. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Corrales, A.; Campano-Cuevas, E.; Castillo-Dalí, G.; Serrera-Figallo, M.; Torres-Lagares, D.; Gutiérrez-Pérez, J.L. Relationship between salivary biomarkers and postoperative swelling after the extraction of impacted lower third molars. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 46, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Roychoudhury, A.; Bhutia, O.; Pandey, S.; Singh, S.; Das, B.K. Antibiotics in third molar extraction; are they really necessary: A non-inferiority randomized controlled trial. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 5, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugh, A.; Patnana, A.K.; Kumar, P.; Chugh, V.K.; Khera, D.; Singh, S. Critical analysis of methodological quality of systematic reviews and meta-analysis of antibiotics in third molar surgeries using AMSTAR 2. J. Oral Biol. Craniofacial Res. 2020, 10, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteagoitia, M.I.; Barbier, L.; Santamaría, J.; Santamaría, G.; Ramos, E. Efficacy of amoxicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid in the prevention of infection and dry socket after third molar extraction. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Y Cir. Bucal 2016, 21, e494–e504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, E.; Santamaría, J.; Santamaría, G.; Barbier, L.; Arteagoitia, I. Do systemic antibiotics prevent dry socket and infection after third molar extraction? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2016, 122, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodi, G.; Azzi, L.; Varoni, E.M.; Pentenero, M.; Del Fabbro, M.; Carrassi, A.; Sardella, A.; Manfredi, M. Antibiotics to prevent complications following tooth extractions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 2, Cd003811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torof, E.; Morrissey, H.; Ball, P.A. The Role of Antibiotic Use in Third Molar Tooth Extractions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina 2023, 59, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sologova, D.; Diachkova, E.; Gor, I.; Sologova, S.; Grigorevskikh, E.; Arazashvili, L.; Petruk, P.; Tarasenko, S. Antibiotics Efficiency in the Infection Complications Prevention after Third Molar Extraction: A Systematic Review. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Hu, J. Prophylactic therapy for prevention of surgical site infection after extraction of third molar: An overview of reviews. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Y Cir. Bucal 2023, 28, e581–e587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soleymani, F.; Pérez-Albacete Martínez, C.; Makiabadi, M.; Maté Sánchez de Val, J.E. Mapping Worldwide Antibiotic Use in Dental Practices: A Scoping Review. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis Prior to Dental Procedures. Available online: https://www.ada.org/resources/ada-library/oral-health-topics/antibiotic-prophylaxis (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Arteagoitia, M.I.; Ramos, E.; Santamaría, G.; Álvarez, J.; Barbier, L.; Santamaría, J. Survey of Spanish dentists on the prescription of antibiotics and antiseptics in surgery for impacted lower third molars. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Y Cir. Bucal 2016, 21, e82–e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camps-Font, O.; Sábado-Bundó, H.; Toledano-Serrabona, J.; Valmaseda-de-la-Rosa, N.; Figueiredo, R.; Valmaseda-Castellón, E. Antibiotic prophylaxis in the prevention of dry socket and surgical site infection after lower third molar extraction: A network meta-analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 53, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupi, S.M.; Olivieri, G.; Landini, J.; Ferrigno, A.; Richelmi, P.; Todaro, C.; Rodriguez y Baena, R. Antibiotic Prophylaxis in the Prevention of Postoperative Infections in Mandibular Third Molar Extractions: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, P.G.J.; Pereira, D.A.; Bonatto, M.S.; Soares, E.C.; Santos, S.d.S.; Martins, A.V.B.; Oliveira, G.J.P.L. Efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis on third molar extraction. Rev. De Odontol. Da UNESP 2023, 52, e20230036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanine, N.; Sabelle, N.; Vergara-Gárate, V.; Salazar, J.; Araya-Cabello, I.; Carrasco-Labra, A.; Martin, C.; Villanueva, J. Effect of antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing infectious complications following impacted mandibular third molar surgery. A randomized controlled trial. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Y Cir. Bucal 2021, 26, e703–e710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcussen, K.B.; Laulund, A.S.; Jørgensen, H.L.; Pinholt, E.M. A Systematic Review on Effect of Single-Dose Preoperative Antibiotics at Surgical Osteotomy Extraction of Lower Third Molars. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 74, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariscal-Cazalla, M.D.M.; Manzano-Moreno, F.J.; García-Vázquez, M.; Vallecillo-Capilla, M.F.; Olmedo-Gaya, M.V. Do perioperative antibiotics reduce complications of mandibular third molar removal? A double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2021, 131, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, R.K.; Kar Yan, L.; Gopinath, D.; Botelho, M.G. Is there a need for postoperative antibiotics after third molar surgery? A 5-year retrospective study. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2019, 10, e12460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.F.; Malmstrom, H.S. Effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis in third molar surgery: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 65, 1909–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodi, G.; Figini, L.; Sardella, A.; Carrassi, A.; Del Fabbro, M.; Furness, S. Antibiotics to prevent complications following tooth extractions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 11, Cd003811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, P.; Wang, J.; Wu, B.; Ma, Y.; Wu, F.; Hou, R. Efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis on postoperative inflammatory complications in Chinese patients having impacted mandibular third molars removed: A split-mouth, double-blind, self-controlled, clinical trial. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 53, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppelaar, M.C.; Zijtveld, C.; Kuipers, S.; Ten Oever, J.; Honings, J.; Weijs, W.; Wertheim, H.F.L. Evaluation of Prolonged vs Short Courses of Antibiotic Prophylaxis Following Ear, Nose, Throat, and Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 2019, 145, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liu, X.G. Efficacy of amoxicillin or amoxicillin and clavulanic acid in reducing infection rates after third molar surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 4016–4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Zhou, F.; Wang, H.; Xu, X.; Xu, S.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, M.; et al. Systemic antibiotics increase microbiota pathogenicity and oral bone loss. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2023, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, R.K.; Gopinath, D.; Li, K.Y.; Leung, Y.Y.; Botelho, M.G. Does the use of amoxicillin/amoxicillin-clavulanic acid in third molar surgery reduce the risk of postoperative infection? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 48, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.Y. Prescription of antibiotics after tooth extraction in adults: A nationwide study in Korea. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 46, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, J.K.; Chang, N.H.; Jeong, Y.K.; Baik, S.H.; Choi, S.K. Development and validation of a difficulty index for mandibular third molars with extraction time. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 46, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Lagares, D.; Gutierrez-Perez, J.L.; Infante-Cossio, P.; Garcia-Calderon, M.; Romero-Ruiz, M.M.; Serrera-Figallo, M.A. Randomized, double-blind study on effectiveness of intra-alveolar chlorhexidine gel in reducing the incidence of alveolar osteitis in mandibular third molar surgery. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2006, 35, 348–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coello-Gómez, A.; Navarro-Suárez, S.; Diosdado-Cano, J.M.; Azcárate-Velazquez, F.; Bargiela-Pérez, P.; Serrera-Figallo, M.A.; Torres-Lagares, D.; Gutiérrez-Pérez, J.L. Postoperative effects on lower third molars of using mouthwashes with super-oxidized solution versus 0.2% chlorhexidine gel: A randomized double-blind trial. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Y Cir. Bucal 2018, 23, e716–e722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera-Barraza, V.; Arroyo-Larrondo, S.; Fernández-Córdova, M.; Catricura-Cerna, D.; Garrido-Urrutia, C.; Ferrer-Valdivia, N. Complications post simple exodontia: A systematic review. Dent. Med. Probl. 2022, 59, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobilio, N.; Vecchiatini, R.; Vasquez, M.; Calura, G.; Catapano, S. Effect of flap design and duration of surgery on acute postoperative symptoms and signs after extraction of lower third molars: A randomized prospective study. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2017, 11, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohn, C.E.; Steimetz, T.; Surkin, P.N.; Fernandez-Solari, J.; Elverdin, J.C.; Guglielmotti, M.B. Effects of saliva on early post-tooth extraction tissue repair in rats. Wound Repair Regen. 2015, 23, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, S.K.; Perrott, D.H.; Susarla, S.M.; Dodson, T.B. Risk factors for inflammatory complications following third molar surgery in adults. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2008, 66, 2213–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz de Baranda, B.; Silvestre, F.J.; Silvestre-Rangil, J. Relationship Between Surgical Difficulty of Third Molar Extraction Under Local Anesthesia and the Postoperative Evolution of Clinical and Blood Parameters. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 77, 1337–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falah Hasan Jumaah, S.S.A.-A. Relationship Between the Surgical Difficulty of Mandibular Third Molar Extraction Under Local Anesthesia and the Postoperative Level of Salivary Alpha Amylase. Pak. J. Med. Health Sci. 2022, 16, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stošić, B.; Šarčev, I.; Mirković, S.; Bajkin, B.; Soldatović, I. A comparative analysis of the efficacy of moxifloxacin and cefixime in the reduction of postoperative inflammatory sequelae after mandibular third molar surgery. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2022, 79, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, S.; Deepak, K.T.; Ambili, R.; Preeja, C.; Archana, V. Gingival biotype and its clinical significance—A review. Saudi J. Dent. Res. 2014, 5, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, T.; Ower, P.; Tank, M.; West, N.; Walter, C.; Needleman, I.; Hughes, F.; Wadia, R.; Milward, M.; Hodge, P. Periodontal diagnosis in the context of the 2017 classification system of periodontal diseases and conditions–implementation in clinical practice. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 226, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, S.M.; Ribeiro, B.C.; Gonçalves, A.S.; Araújo, L.M.; Toledo, G.L.; Amaral, M.B. Double blind randomized clinical trial comparing minimally-invasive envelope flap and conventional envelope flap on impacted lower third molar surgery. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Y Cir. Bucal 2022, 27, e518–e524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experimental Group | Placebo Group | Total Number of Included Data | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, Number | Male | 5 | 8 | 13 | 0.1 * |

| Female | 4 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Age (year), Mean ± SD | 24.1 ± 4.4 | 25.7 ± 3.9 | 18 | 0.1 # | |

| Difficulty index (DI), Number | I | 8 | 3 | 11 | 0.02 * |

| II | 1 | 6 | 7 | ||

| III & IV | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Surgery duration (in seconds), Mean ± SD | 1605.3 ± 1478.6 | 1205.1 ± 964.1 | 18 | 0.06 $ | |

| Osteotomy, Number | Yes | 5 | 5 | 10 | 1 * |

| No | 4 | 4 | 8 | ||

| Tooth section, Number | Yes | 6 | 3 | 9 | 0.6 * |

| No | 7 | 2 | 9 | ||

| Number of tooth sections, Mean ± SD | 3.2 ± 2.9 | 2.72 ± 3 | 9 | 0.4 # | |

| Number of sutures, Mean ± SD | 3.4 ± 1.01 | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 18 | 0.2 # | |

| Group | N | Mean ± SD | Effect Size | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain (Median ± IQR) | After surgery | Experimental | 9 | 1 ± 3 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Placebo | 9 | 0 ± 1.5 | ||||

| 6 h | Experimental | 9 | 6 ± 2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| Placebo | 9 | 4 ± 5 | ||||

| 12 h | Experimental | 9 | 5 ± 3 | 0.01 | 0.9 | |

| Placebo | 9 | 4 ± 7.5 | ||||

| 24 h | Experimental | 9 | 5 ± 1.5 | 0.2 | 0.4 | |

| Placebo | 9 | 3 ± 8.5 | ||||

| 48 h | Experimental | 9 | 4 ± 3.5 | 0.0 | 1.0 | |

| Placebo | 9 | 2 ± 7.5 | ||||

| 72 h | Experimental | 9 | 2 ± 4.5 | 0.05 | 0.8 | |

| Placebo | 9 | 2 ± 7 | ||||

| 4th day | Experimental | 9 | 1 ± 4 | 0.1 | 0.6 | |

| Placebo | 9 | 4 ± 5.5 | ||||

| 5th day | Experimental | 9 | 1 ± 3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| Placebo | 9 | 2 ± 3 | ||||

| 6th day | Experimental | 9 | 1 ± 3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| Placebo | 9 | 1 ± 3.5 | ||||

| Salivary PGE2 concentration (pg/mL) | Baseline | Experimental | 9 | 422.5 ± 436.8 | −0.6 | 0.2 |

| Placebo | 9 | 687.9 ± 497.0 | ||||

| 24 h | Experimental | 9 | 487.8 ± 453.3 | −0.6 | 0.2 | |

| Placebo | 9 | 760.3 ± 461.3 | ||||

| 7 days | Experimental | 9 | 652.3 ± 513.7 | −0.01 | 0.9 | |

| Placebo | 9 | 657.6 ± 445.8 | ||||

| Facial swelling (%) | 24 h | Experimental | 9 | 4.4 ± 1.8 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Placebo | 9 | 3.5 ± 2.6 | ||||

| 7 days | Experimental | 9 | 1.3 ± 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.6 | |

| Placebo | 9 | 1.1 ± 1.1 | ||||

| MMO changes (mm) | After surgery | Experimental | 8 | 4.1 ± 3.4 | −0.03 | 0.7 |

| Placebo | 9 | 4.2 ± 2.1 | ||||

| 24 h | Experimental | 9 | 17.9 ± 12.6 | −0.06 | 0.9 | |

| Placebo | 9 | 18.56 ± 11.6 | ||||

| 7 days | Experimental | 9 | 13.0 ± 11.0 | 0.3 | 0.5 | |

| Placebo | 9 | 9.4 ± 9.5 |

| Pain | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After | 6 h | 12 h | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | 4 D | 5 D | 6 D | ||

| Gender | CC | −0.1 | −0.3 | −0.3 | −0.4 | −0.5 * | −0.4 | −0.3 | −0.1 | −0.05 |

| p | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.8 | |

| Age | CC | −0.6 * | 0.1 | −0.06 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.17 | −0.2 | −0.2 | −0.3 |

| p | 0.01 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | |

| DI | CC | 0.0 | −0.3 | 0.2 | 0.02 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.6 * |

| p | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.08 | 0.01 | |

| Tooth section | CC | 0.0 | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.17 | −0.2 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.05 |

| p | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.8 | |

| Number of tooth sections | CC | 0.2 | −0.06 | −0.06 | −0.05 | −0.4 | −0.3 | −0.3 | −0.35 | −0.09 |

| p | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.7 | |

| Number of sutures | CC | 0.1 | 0.5 * | 0.6 * | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0.12 |

| p | 0.6 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.6 | |

| Surgery duration (S) | CC | 0.2 | −0.1 | 0.05 | −0.01 | −0.2 | −0.16 | −0.1 | −0.05 | 0.3 |

| p | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.3 | |

| Osteotomy | CC | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 ** |

| p | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.007 | |

| PGE2 Concentration | MMO Changes | Facial Swelling | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 24 h | 7 D | After | 24 h | 7 D | 24 h | 7 D | |||

| Gender | PC | 0.2 | −0.2 | −0.2 | 0.4 | 0.08 | −0.2 | −0.3 | −0.3 | |

| p | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.15 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | ||

| Age | PC | 0.15 | −0.2 | −0.2 | −0.1 | −0.45 | −0.3 | −0.4 | −0.3 | |

| p | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.06 | 0.2 | 0.07 | 0.3 | ||

| DI | CC | 0.08 | 0.03 | −0.15 | 0.3 | 0.63 ** | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| p | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.005 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | ||

| Surgery duration | PC | −0.3 | −0.4 | −0.5 * | 0.67 ** | 0.5 * | 0.4 | 0.5 * | 0.1 | |

| p | 0.2 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.003 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.6 | ||

| Osteotomy | PC | −0.004 | −0.1 | −0.2 | 0.5 | 0.8 ** | 0.68 ** | 0.5 * | 0.07 | |

| p | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.06 | 0.0 | 0.002 | 0.03 | 0.8 | ||

| Tooth section | PC | −0.05 | −0.5 * | −0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −0.02 | |

| p | 0.8 | 0.04 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.9 | ||

| Number of tooth sections | PC | 0.3 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 | |

| p | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.5 | ||

| Number of sutures | PC | 0.3 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| p | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | ||

| Facial Swelling | 24 h | PC | −0.15 | −0.07 | −0.07 | 0.5 | 0.66 ** | 0.6 ** | 1 | 0.6 ** |

| p | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.05 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.007 | |||

| 7 D | PC | 0.25 | 0.07 | 0.2 | −0.004 | 0.4 | 0.51 * | 0.6 ** | 1 | |

| p | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.007 | |||

| MMO changes | After | PC | −0.1 | −0.16 | −0.2 | 1 | 0.62 ** | 0.4 | 0.5 | −0.004 |

| p | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.008 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.9 | |||

| 24 h | PC | 0.2 | −0.02 | 0.1 | 0.62 ** | 1 | 0.85 ** | 0.66 ** | 0.4 | |

| p | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.008 | 0.0 | 0.003 | 0.1 | |||

| 7 D | PC | 0.3 | −0.03 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.85 ** | 1 | 0.6 ** | 0.51 * | |

| p | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.005 | 0.03 | |||

| Pain | After | CC | −0.1 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.3 | 0.09 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| p | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.07 | 0.1 | ||

| 6 h | CC | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |

| p | 0.07 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | ||

| 12 h | CC | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.13 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 * | 0.3 | |

| p | 0.2 | 0.07 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.3 | ||

| 24 h | CC | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.25 | −0.06 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | |

| p | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.3 | ||

| 48 h | CC | 0.5 * | 0.5 * | 0.5 * | −0.06 | 0.2 | 0.5 * | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| p | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.02 | 0.2 | 0.1 | ||

| 72 h | CC | 0.5 * | 0.5 * | 0.5 * | 0.04 | 0.3 | 0.6 ** | 0.35 | 0.4 | |

| p | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.008 | 0.15 | 0.1 | ||

| 4 D | CC | 0.6 * | 0.6 * | 0.6 ** | 0.08 | 0.3 | 0.6 ** | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| p | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.005 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.007 | 0.2 | 0.2 | ||

| 5 D | CC | 0.5 * | 0.5 * | 0.5 * | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.6 ** | 0.3 | 0.04 | |

| p | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.3 | 0.08 | 0.009 | 0.3 | 0.9 | ||

| 6 D | CC | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.05 | 0.3 | 0.5 * | 0.5 * | 0.4 | −0.01 | |

| p | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.1 | 0.9 | ||

| Criteria | Details |

|---|---|

| Inclusion Criteria | Adult patients (more than 18 years old) |

| Requiring at least one impacted mandibular third molar extraction | |

| Healthy (ASA I and II) | |

| Non-smokers | |

| No history of viral or microbial diseases in the past four months | |

| No known allergies to penicillin-class antibiotics or other drugs | |

| No use of anti-inflammatory or contraceptive drugs in the past month | |

| No autoimmune diseases | |

| Not pregnant or nursing (for women) | |

| Exclusion Criteria | History of dental pain, inflammation, or abscess in the past month |

| Thyroid hormone therapy | |

| Unwillingness to participate in the study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soleymani, F.; Maté Sánchez de Val, J.E.; Lijnev, A.; Makiabadi, M.; Martínez, C.P.-A. Effect of Antibiotics on Clinical and Laboratory Outcomes After Mandibular Third Molar Surgery: A Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14020195

Soleymani F, Maté Sánchez de Val JE, Lijnev A, Makiabadi M, Martínez CP-A. Effect of Antibiotics on Clinical and Laboratory Outcomes After Mandibular Third Molar Surgery: A Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(2):195. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14020195

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoleymani, Fatemeh, José Eduardo Maté Sánchez de Val, Artiom Lijnev, Mehrdad Makiabadi, and Carlos Pérez-Albacete Martínez. 2025. "Effect of Antibiotics on Clinical and Laboratory Outcomes After Mandibular Third Molar Surgery: A Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial" Antibiotics 14, no. 2: 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14020195

APA StyleSoleymani, F., Maté Sánchez de Val, J. E., Lijnev, A., Makiabadi, M., & Martínez, C. P.-A. (2025). Effect of Antibiotics on Clinical and Laboratory Outcomes After Mandibular Third Molar Surgery: A Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Antibiotics, 14(2), 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14020195