A Nationwide Survey of Australian General Practitioners on Antimicrobial Stewardship: Awareness, Uptake, Collaboration with Pharmacists and Improvement Strategies

Abstract

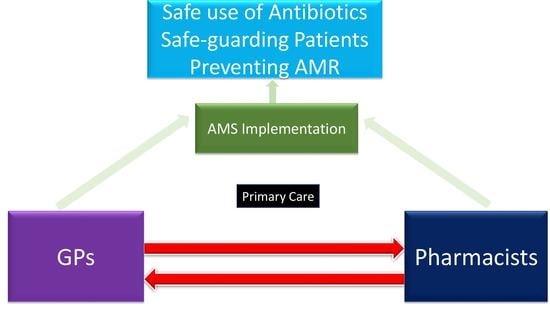

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Response and Reliability

2.3. Demographic Characteristics

2.4. Awareness of AMS

2.5. Uptake of AMS Strategies

2.6. Attitudes Towards GP–Pharmacist Collaboration in AMS

2.7. Attitudes Towards Future AMS Strategies

2.8. Barriers and Facilitators to Improve AMS

2.8.1. Barriers to Conducting AMS by GPs

2.8.2. Facilitators to Conducting AMS

2.9. Discussions

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Development of the Survey Tool

3.2. Description of Survey Tool

3.3. Sampling Strategy

3.4. Survey Deployment

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Approval

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Antimicrobial Resistance and Primary Health Care Geneva: WHO, 2018, 1–12. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/326454/WHO-HIS-SDS-2018.56-eng.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2019).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Stemming the Superbug Tide: Just a Few Dollars More; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/health/stemming-the-superbug-tide-9789264307599-en.htm (accessed on 26 December 2018).

- McCullough, A.R.; Pollack, A.J.; Plejdrup Hansen, M.; Glasziou, P.P.; Looke, D.F.; Britt, H.C. Antibiotics for acute respiratory infections in general practice: Comparison of prescribing rates with guideline recommendations. Med. J. Aust. 2017, 207, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingram, R.; Manski-Nankervis, J.; Biezen, R.; Buising, K. A need for action: Results of the Australian pilot General Practice National Antimicrobial Prescribing Survey (GP NAPS). In Proceedings of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID), 29th ESCMID Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherland, 28 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dyar, O.J.; Beovic, B.; Vlahovic-Palcevski, V.; Verheij, T.; Pulcini, C. How can we improve antibiotic prescribing in primary care? Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2016, 14, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Australian Government Released the First National Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy 2015–2019 to Guide the Response to the Threat of Antibiotic Misuse and Resistance. Available online: https://www.amr.gov.au/resources/national-amr-strategy (accessed on 12 June 2018).

- Del Mar, C.B.; Scott, A.M.; Glasziou, P.P.; Hoffmann, T.; van Driel, M.L.; Beller, E. Reducing antibiotic prescribing in Australian general practice: Time for a national strategy. Med. J. Aust. 2017, 207, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Antimicrobial Stewardship (AMS) Resources and Links. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/antimicrobial-stewardship/antimicrobial-stewardship-ams-resources-and-links (accessed on 16 October 2018).

- NPS Medicine Wise. World Antibiotic Awareness Week 2018. Available online: https://www.nps.org.au/antibiotic-awareness (accessed on 28 September 2018).

- NPS Medicine Wise. Antimicrobial Modules. Available online: https://learn.nps.org.au/mod/page/view.php?id=4282 (accessed on 27 July 2018).

- NPS Medicine Wise. Case Study-Otitis Media: Clarifying the Role of Antibiotics. Available online: https://learn.nps.org.au/totara/coursecatalog/courses.php. (accessed on 6 February 2019).

- Klepser, M.E.; Adams, A.J.; Klepser, D.G. Antimicrobial stewardship in outpatient settings: Leveraging innovative physician-pharmacist collaborations to reduce antibiotic resistance. Health Secur. 2015, 13, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.K.; Hawes, L.; Mazza, D. Effectiveness of interventions involving pharmacists on antibiotic prescribing by general practitioners: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Antimicrob Chemother. 2019, 74, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepser, M.E.; Klepser, D.G.; Dering-Anderson, A.M.; Morse, J.A.; Smith, J.K.; Klepser, S.A. Effectiveness of a pharmacist-physician collaborative program to manage influenza-like illness. J. Am. Pharm Assoc. 2016, 56, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepser, D.G.; Klepser, M.E.; Dering-Anderson, A.M.; Morse, J.A.; Smith, J.K.; Klepser, S.A. Community pharmacist-physician collaborative streptococcal pharyngitis management program. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2016, 56, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.F.; Owens, R.; Sallis, A.; Ashiru-Oredope, D.; Thornley, T.; Francis, N.A. Qualitative study using interviews and focus groups to explore the current and potential for antimicrobial stewardship in community pharmacy informed by the Theoretical Domains Framework. BMJ. Open 2018, 8, e025101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlam, T.F.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Abbo, L.M.; MacDougall, C.; Schuetz, A.N.; Septimus, E.J.; Srinivasan, A.; Dellit, T.H.; Falck-Ytter, Y.T.; Fishman, N.O.; et al. Implementing an Antibiotic Stewardship Program: Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñalva, G.; Fernández-Urrusuno, R.; Turmo, J.M.; Hernández-Soto, R.; Pajares, I.; Carrión, L.; Vázquez-Cruz, I.; Botello, B.; García-Robredo, B.; Cámara-Mestres, M.; et al. Long-term impact of an educational antimicrobial stewardship programme in primary care on infections caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in the community: An interrupted time-series analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Katwyk, S.R.; Jones, S.L.; Hoffman, S.J. Mapping educational opportunities for healthcare workers on antimicrobial resistance and stewardship around the world. Hum. Resour. J. 2018, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, N.A.; Gillespie, D.; Nuttall, J.; Hood, K.; Little, P.; Verheij, T.; Goossens, H.; Coenen, S.; Butler, C.C. Delayed antibiotic prescribing and associated antibiotic consumption in adults with acute cough. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2012, 62, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, P.; Moore, M.; Kelly, J.; Williamson, I.; Leydon, G.; McDermott, L.; Mullee, M.; Stuart, B. Delayed antibiotic prescribing strategies for respiratory tract infections in primary care: Pragmatic, factorial, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2014, 348, g1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avent, M.L.; Fejzic, J.; van Driel, M.L. An underutilised resource for Antimicrobial Stewardship: A ‘snapshot’of the community pharmacists’ role in delayed or ‘wait and see’antibiotic prescribing. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2018, 26, 373–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borek, A.J.; Wanat, M.; Sallis, A.; Ashiru-Oredope, D.; Atkins, L.; Beech, E.; Hopkins, S.; Jones, L. How can national antimicrobial stewardship interventions in primary care be improved? A stakeholder consultation. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnet, D.L.; Ferech, M.; Frimodt-Møller, N.; Goossens, H. The more antibacterial trade names, the more consumption of antibacterials: A European study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 41, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Agency for the Safety of Medicines and Health Products (ANSM) 2013. Available online: https://www.emergobyul.com/resources/europe/french-agency-safety-health-products#:~:text=The%20National%20Agency%20for%20the,%2C%20medical%20devices%2C%20and%20cosmetics (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Vardpersonal, F. Startsida. Available online: https://www.fass.se/LIF/startpage?userType=0 (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Aabenhus, R.; Hansen, M.P.; Siersma, V.; Bjerrum, L. Clinical indications for antibiotic use in Danish general practice: Results from a nationwide electronic prescription database. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2017, 35, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perozziello, A.; Lescure, F.X.; Truel, A.; Routelous, C.; Vaillant, L.; Yazdanpanah, Y.; Lucet, J.C. Prescribers’ experience and opinions on antimicrobial stewardship programmes in hospitals: A French nationwide survey. J. Antimicrob Chemother. 2019, 74, 2451–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gastel, E.; Costers, M.; Peetermans, W.E.; Struelens, M.J. Hospital Medicine Working Group of the Belgian Antibiotic Policy Coordination Committee. Nationwide implementation of antibiotic management teams in Belgian hospitals: A self-reporting survey. J. Antimicrob Chemother. 2010, 65, 576–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brijnath, B.; Bunzli, S.; Xia, T.; Singh, N.; Schattner, P.; Collie, A.; Sterling, M.; Mazza, D. General practitioners knowledge and management of whiplash associated disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder: Implications for patient care. BMC Fam. Pract. 2016, 17, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonevski, B.; Magin, P.; Horton, G.; Foster, M.; Girgis, A. Response rates in GP surveys: Trialling two recruitment strategies. Aust. Fam. Physician 2011, 40, 427. [Google Scholar]

- Cull, W.L.; O’connor, K.G.; Sharp, S.; Tang, S.F.S. Response rates and response bias for 50 surveys of pediatricians. Health Serv. Res. 2005, 40, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulcini, C.; Leibovici, L. CMI guidance for authors of surveys. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016, 22, 901–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, A.; Labbate, M.; Norris, J.M.; Gilbert, G.L.; Ward, M.P.; Bajorek, B.V.; Degeling, C.; Rowbotham, S.J.; Dawson, A.; Nguyen, K.A.; et al. Opportunities and challenges to improving antibiotic prescribing practices through a One Health approach: Results of a comparative survey of doctors, dentists and veterinarians in Australia. BMJ Open 2017, 8, e020439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baadani, A.M.; Baig, K.; Alfahad, W.A.; Aldalbahi, S.; Omrani, A.S. Physicians’ knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes toward antimicrobial prescribing in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2015, 36, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giry, M.; Pulcini, C.; Rabaud, C.; Boivin, J.M.; Mauffrey, V.; Birgé, J. Acceptability of antibiotic stewardship measures in primary care. Med. Mal. Infect. 2016, 46, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauffrey, V.; Kivits, J.; Pulcini, C.; Boivin, J.M. Perception of acceptable antibiotic stewardship strategies in outpatient settings. Med. Mal. Infect. 2016, 46, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, R.; Jones, L.; Moore, M.; Pilat, D.; McNulty, C. Self-Assessment of Antimicrobial Stewardship in Primary Care: Self-Reported Practice Using the TARGET Primary Care Self-Assessment Tool. Antibiotics 2017, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.T.; Ferreira, M.; Roque, F.; Falcão, A.; Ramalheira, E.; Figueiras, A.; Herdeiro, M.T. Physicians’ attitudes and knowledge concerning antibiotic prescription and resistance: Questionnaire development and reliability. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.K.; Barton, C.; Promite, S.; Mazza, D. Knowledge, Perceptions and Practices of Community Pharmacists Towards Antimicrobial Stewardship: A Systematic Scoping Review. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raosoft. An Online Sample Size Calculator. Available online: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html (accessed on 10 July 2018).

- Gattellari, M.; Worthington, J.M.; Zwar, N.A.; Middleton, S. The management of non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) in Australian general practice: Bridging the evidence-practice gap. A national, representative postal survey. BMC Fam Pract. 2008, 9, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, A.; Overgaard, S.; Lauritsen, J.M. Quality of data entry using single entry, double entry and automated forms processing—An example based on a study of patient-reported outcomes. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health. General Practice Workforce Statistics–2001–02 to 2016–17; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2017. Available online: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/General+Practice+Statistics-1 (accessed on 25 January 2018).

- Holden, R.J.; Carayon, P.; Gurses, A.P.; Hoonakker, P.; Hundt, A.S.; Ozok, A.A.; Rivera-Rodriguez, A.J. SEIPS 2.0: A human factors framework for studying and improving the work of healthcare professionals and patients. Ergonomics 2013, 56, 1669–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, S.C.; Tamma, P.D.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Miller, M.A.; Sateia, H.; Szymczak, J.; Gurses, A.P.; Linder, J.A. Ambulatory antibiotic stewardship through a human factors engineering approach: A systematic review. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2018, 31, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Sample Availability: Data of this study are available from the corresponding author and are accessible to all authors. |

| Demographics | Frequency (n) | Valid % | Australian GPs (n = 34,606) | Chi Square P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (n = 381) | ||||

| Male | 195 | 51.1 | ||

| Female | 186 | 48.8 | 44.7 | <0.109 |

| Education (n = 384) | ||||

| B. Med science | 4 | 1.0 | - | |

| MBBS | 305 | 79.4 | - | |

| MD | 31 | 8.0 | - | |

| Masters | 39 | 10.1 | - | |

| PhD | 5 | 1.3 | - | |

| Years of practice (n = 385) | ||||

| ≤5 | 20 | 5.2 | ||

| 6–10 | 43 | 11.1 | ||

| >10 | 322 | 83.6 | ||

| Current practice location (n = 384) | ||||

| Metro | 234 | 60.9 | 68.2 | <0.0023 |

| Regional | 74 | 19.2 | 28.0 | <0.0001 |

| Rural | 62 | 16.1 | - | |

| Remote | 14 | 3.6 | 3.9 | <0.76 |

| State of work (n = 385) | ||||

| New South Wales (NSW) | 104 | 27.0 | 30.6 | <0.127 |

| Victoria (VIC) | 105 | 27.2 | 24.1 | <0.157 |

| Queensland (QLD) | 73 | 18.9 | 21.7 | <0.184 |

| Australian Capital Territory (ACT) | 5 | 1.2 | 1.5 | < 0.63 |

| South Australia (SA) | 39 | 10.1 | 7.8 | <0.094 |

| Western Australia (WA) | 36 | 9.3 | 10.2 | <0.561 |

| Tasmania (TAS) | 18 | 4.6 | 2.6 | <0.014 |

| Northern Territory (NT) | 5 | 1.3 | 1.5 | <0.75 |

| Medical training (n = 385) | ||||

| Outside Australia | 124 | 32.2 | - | |

| Inside Australia | 261 | 67.7 | - | |

| Completion of the National Prescribing Service’s (NPS’) antimicrobial prescribing course (n = 383) | ||||

| Yes | 105 | 27.4 | - | |

| No | 200 | 52.2 | - | |

| Not aware | 78 | 20.3 | - |

| Factors | Major Barriers | Major Facilitators |

|---|---|---|

| Person | Patient level: Patient expectations, lack of awareness regarding the risk of antibiotic use, late presentation of patients despite severe symptoms, desire for a quick recovery and poor health literacy. GP-level: GPs’ perception: “pharmacists are just a dispenser”, and “pharmacists have no adequate knowledge to educate GPs in AMS” Older GPs. Old habit of antibiotic prescribing. Inertia to change prescribing. Pharmacist level: conflict of interest to recommending antimicrobials, ignorance of a patient’s clinical records. | GPs’ willingness to follow AMS guidance AMS training. Confidence to not to prescribe antibiotics. Patients’ awareness and trust on doctors. |

| Tools and technology | No protocol that defines AMS tasks in practice. Lack of access and usability of Therapeutic Guidelines (TG) (Cost, broad recommendations Trustworthiness for some clinical conditions). IT facilities. Limited point-of- care testing facilities. | eTG (electronic Therapeutic Guidelines). Point-of-care tests. Clear guidelines on AMS task. Telehealth technologies. Patient communication tools. |

| Organisation | Lack of access to Infectious Disease physicians, pharmacists and microbiological services. Legal system for delayed prescribing. Delayed access to diagnostic reports (e.g., Antibiotic sensitivity, culture test). Lack of provision of AMS training. No monitoring and follow up of AMS related task. | AMS training programs.Access to infectious disease physicians, microbiologists and pharmacists. Weekly practice meeting for discussing AMS strategies. Improved “My Health Records”. Antimicrobial prescribing audit tools. Rapid testing results of antibiotic sensitivity. NPS-led visits and academic detailing. |

| Task | Time constrain to do AMS task and consulting with pharmacists | Increasing AMS staff time.Longer consultation time. Promoting delayed prescribing. Shared decision-making approach. |

| Physical environment | Information leaflets for educating patients | Patient education leaflets and posters. NPS handouts for treating infections. |

| External environment | Incentives. Funding model for AMS implementation. Extended validity of repeat antimicrobial prescriptions. | Media campaigns. GP–pharmacist group meetings. GP–pharmacy practice agreement. Policy limiting some broad-spectrum antibiotic prescription. Incentives for a longer consultation. Policy restricting repeat antimicrobial prescriptions. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saha, S.K.; Kong, D.C.M.; Thursky, K.; Mazza, D. A Nationwide Survey of Australian General Practitioners on Antimicrobial Stewardship: Awareness, Uptake, Collaboration with Pharmacists and Improvement Strategies. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 310. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics9060310

Saha SK, Kong DCM, Thursky K, Mazza D. A Nationwide Survey of Australian General Practitioners on Antimicrobial Stewardship: Awareness, Uptake, Collaboration with Pharmacists and Improvement Strategies. Antibiotics. 2020; 9(6):310. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics9060310

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaha, Sajal K., David C. M. Kong, Karin Thursky, and Danielle Mazza. 2020. "A Nationwide Survey of Australian General Practitioners on Antimicrobial Stewardship: Awareness, Uptake, Collaboration with Pharmacists and Improvement Strategies" Antibiotics 9, no. 6: 310. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics9060310

APA StyleSaha, S. K., Kong, D. C. M., Thursky, K., & Mazza, D. (2020). A Nationwide Survey of Australian General Practitioners on Antimicrobial Stewardship: Awareness, Uptake, Collaboration with Pharmacists and Improvement Strategies. Antibiotics, 9(6), 310. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics9060310