Environmental Factors Causing the Development of Microorganisms on the Surfaces of National Cultural Monuments Made of Mineral Building Materials—Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Factors Influencing the Development of Microorganisms

- precipitation,

- ground water,

- rainwater,

- process and operating water,

- condensation of water vapors on the surface of the partition and inside it,

- damage to installations,

- humid air surrounding partitions and building materials,

- flooding [13].

- minimum, below which cell growth and divisions do not occur

- optimal, in which cells grow and divide at the fastest rate

- maximum, above which growth and divisions do not occur

- absolutely aerobic (absolute aerobes)—require aerobic conditions at atmospheric concentration (20%); get their energy through aerobic respiration; the value of the potential is in the range 0.2–0.4. Absolutely anaerobic (absolute anaerobes)—get their energy anaerobically; hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), a strongly oxidizing compound, is formed in metabolic processes in the presence of oxygen; the potential (Eh) is below −0.2 V

- relatively anaerobic—can develop under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions, grow at low atmospheric oxygen concentration, get their energy through aerobic respiration; the value of the potential can be both positive and negative

- microaerophiles—microorganisms that require oxygen to survive but at a low concentration [18].

- gram-negative bacteria sensitive to high pressure. They can be inactivated at 300 MPa and higher

- fungi that are inactivated at 400 MPa or higher

- gram-positive bacteria resistant to high pressures, inactivated at 600 MPa and higher

- dry rot and mold on lintels, jambs, under windowsills, and in corners

- steamy windows

- condensed water vapor on cool wall surfaces and objects

- air supply through exhaust grilles in the kitchen or bathroom (so-called back draught)

- swelling of wood furniture and floors.

- non-heating season, i.e., the summer period during which climatic conditions indoors are similar to those in outdoor air

- heating season (with intense growth), i.e., the autumn-winter period during which a new microclimate is established.

- prototrophs, which only require one type of carbon compound to grow, and

- auxotrophs, which require at least two types of carbon compounds [18].

- nitrous acid, e.g., Nitrosomonas spp.,

- nitric acid, e.g., Nitrobacter spp.,

- sulfuric acid, e.g., Acidothiobacillus spp.

2.1. Inside

2.2. Outside

- release of corrosive acids—limestone and marble [85];

- alkaline attack on silicate rocks [86];

- uptake and accumulation of sulfur and calcium to cells [87];

- change of stone forming minerals [88];

- and pore widening as a result of penetration of the keel and fiber, loosening stone particles from the parent rock material, mainly on granite rocks [89].

- patina type 1—biofilm formation. It occurs on rocks such as silica sandstone, granite, basalt, slate, limestone, metamorphic rocks (gneiss, quartzite, marble). A single-layer biofilm is formed on the surface or along natural cracks and fissures. The biofilm is dominated by phototrophic microflora or fungi. There are the following biodeterioration processes: discoloration due to the separation of pigments and oxidation of iron and manganese ions; the formation of a biofilm (EPS) and the subsequent development of a thinly flaking coating; local bio-corrosion (bio-pitting) due to the secretion of organic acids by microorganisms.

- Patina type 2—surface corrosion. Occurs on rocks such as volcanic tuff, sintered clays (aluminum binder), silica sandstone, artificial stones (brick, mortar, concrete. Microbial contamination to a depth of 5 cm. Mainly dominated by bacteria. The following biodeterioration processes occur here: biofilm formation) (EPS) narrowing of the pores of the scale, which leads to an increase in capillary rise of water; biocorrosion due to the release of inorganic and organic acids by microorganisms.

- Patina type 3—formation of the crust (deposits). Occurs on rocks with a binder of clay and limestone, material binding. Occurs in the highest layers of stone, it penetrates deeply (max. 1 cm or with stone slate). Rises complex and stable microflora (“microbial mat”). The following biodeterioration processes exist here: discoloration due to the separation of pigments and oxidation of Fe and Mn ions; the formation of a biofilm (EPS), sealing the pores of rocks due to a reduction in diffusion of moisture and enrichment with atmospheric particles with the subsequent formation of a crust (deposit); biocorrosion due to the release of inorganic and organic acids by microorganisms

3. Conclusions

- In areas with warm, humid climates, they provide favorable environmental conditions for the development of most organisms. Objects undergo degradation and discoloration under the influence of the action and growth of microorganisms. It forms on the surface of the biofilm, thus reducing its aesthetic values.

- In tropical climate conditions, biodegradation and biodeterioration is accelerated.

- In a cold continental climate, air pollution causes similar effects to those mentioned above.

- Microorganisms can also grow on the surfaces of mineral materials in winter, creating biofilms at night at low temperatures from −10 to −25 °C.

- Inside the rooms, biofilms are produced on the surfaces, colour changes occur and the material/binder is dissolved by the chemical action of the metabolites. Infection of the surface can occur at any temperature and humidity.

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bertron, A. Understanding interactions between cementitious materials and microorganisms: A key to sustainable and safe concrete structures in various contexts. Mater. Struct. 2014, 47, 1787–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gadd, G.M.; Dyer, T.D. Bioprotection of the built environment and cultural Heritage. Microb. Biotechnol. 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charkowska, A.; Mijakowski, M. Wilgoć, Pleśnie i Grzyby w Budynkach, 1st ed.; Verlag Dashofer: Warszawa, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Wang, C.; Fei, B.; Ma, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, S.; Huang, A. Biological Degradation of Chinese Fir with Trametes versicolor (L.) Lloyd. Materials 2017, 10, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piontek, A.; Lechów, H. Deterioracja Elewacji Zewnętrznych Wywołana Biofilne. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Zielonogórskiego 2013, 151, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Koul, B.; Upadhyay, H. Fungi-Mediated Biodeterioration of Household Materials, Libraries, Cultural Heritage and Its Control. In Fungi and Their Role in Sustainable Development: Current Perspectives; Gehlot, P., Singh, J., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyska, B. Mikrobiologiczna Korozja Materiałów, 1st ed.; Wydawnictwa Naukowo-Techniczne: Warszawa, Poland, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Curling, S.F.; Clausen, C.A.; Winandy, J.E. Experimental method to quantify progressive stage of decay of wood by basidomycete fungi. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2002, 49, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esener, A.A.; Bol, G.; Kossen, N.W.F.; Roels, J.A. Effect of Water Activity on Microbial Growth; Murray, M.-Y., Robinson, C.W., Vezina, C., Eds.; Scientific and Engineering Principles: Pergamon, Turkey, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libudzisz, Z.; Kowal, K. Praca zbiorowa. In Mikrobiologia techniczna, Tom I, 1st ed.; Politechnika Łódzka: Łódź, Poland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kostyrko, K.; Okołowicz-Grabowska, B. Pomiary i Regulacja Wilgotności w Pomieszczeniach; Arkady: Warszawa, Poland, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Trechsel, H.R.; Bomberg, M.T. Moisture Control in Buildings—The Key Factor in Mold Prevention Limitation of Access to Water; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ważny, J.; Karyś, J. Ochrona Budynków Przed Korozją Biologiczną; Arkady: Warszawa, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Czajnik, M. Impregnacja i Odgrzybianie w Budownictwie; Arkady: Warszawa, Poland, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Frisvad, J.C.; Gravesen, S. Penicillium and Aspergillus from Danish homes and working places with indoor air problem: Identification and mycotoxin determination. In Health Implications of Fungi in Indoor Air Environment: Air Quality Monographs; Samson, R.A., Flannigan, B., Flannigan, M.E., Verhoeff, A.P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel, H.G. Mikrobiologia Ogólna, Pod Red. Nauk. Zdzisława Markiewicza; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brasca, M.; Morandi, S.; Lodi, R.; Tamburini, A. Redox potential to discriminate among species of lactic acid bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 103, 1516–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elimer, E. Mikrobiologia Techniczna; Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej: Wrocław, Poland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowska-Pańczyk, E.; Kołodziejska, I. Wpływ wysokiego ciśnienia na mikroorganizmy. Med. Wet. 2005, 61, 150–153. [Google Scholar]

- Dudzińska, A.; Domagała, J.; Wszołek, M. Wpływ wysokiego ciśnienia hydrostatycznego na mikroorganizmy występujące w mleku i na właściwości mleka. Żywność Nauka Technol. Jakość 2014, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Powalowski, S.; Gulewicz, P.; Grajek, W. Wplyw cisnienia osmotycznego na stan fizjologiczny komórek bakteryjnych. Postępy Biol. Komórki 2002, 29, 435–448. [Google Scholar]

- Keenleyside, W. Microbiology: Canadian Edition. Open Library PressBooks. Available online: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/microbio/front-matter/preface/ (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Libudzisz, Z. Mikroorganizmy a Rozkład i Korozja Mikrobiologiczna. I Ogólnokrajowa Konferencja Naukowa “Rozkład i Korozja Mikrobiologiczna Materiałów Technicznych”, Poland, 27 Stycznia 2000; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Łódzkiej: Łódź, Poland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rymsza, B. Biodeterioracja Pleśniowa Obiektów Budowlanych, 1st ed.; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Poznańskiej: Poznań, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

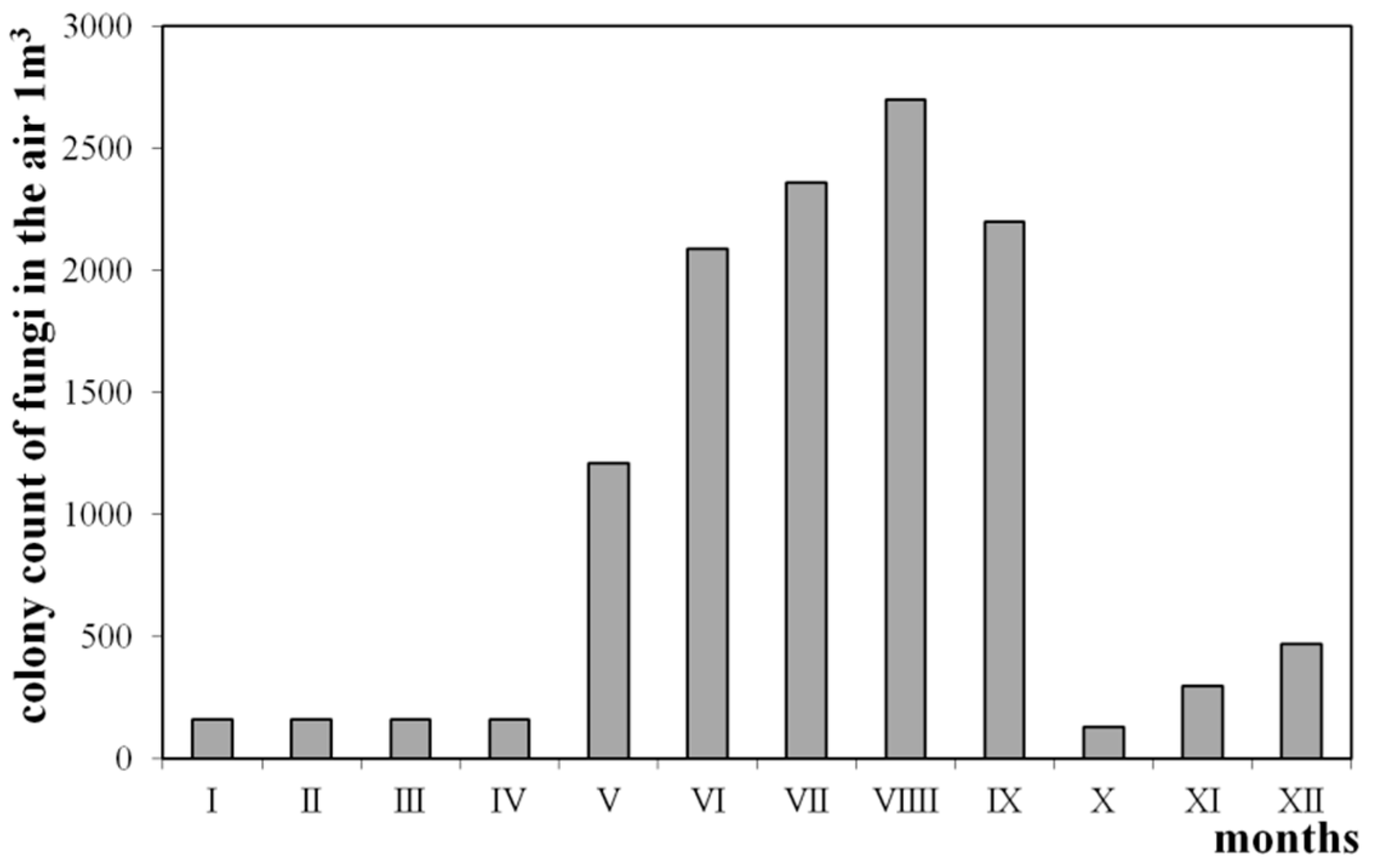

- Mędrela-Kuder, E. Sezonowe Wahania w Występowaniu Grzybów w Powietrzu sal Dydaktycznych oraz w Powietrzu Otwartej Przestrzeni. In Problemy Jakości Powietrza Wewnętrznego w Polsce ’99, Poland, 2000; Politechnika Warszawska: Warszawa, Poland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jasińska, B. Czynniki środowiskowe determinujące aktywność korozji mikrobiologicznej w budownictwie. In Ogólnokrajowa Konferencja Naukowa “Rozkład i Korozja Mikrobiologiczna Materiałów Technicznych”, Poland, 27 Stycznia 2000; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Łódzkiej: Łódź, Poland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ważny, J.; Karyś, J. Korozja Biologiczna Betonu, Zapraw i Cegły Wywołana Przez Grzyby Domowe; Kontra: Zakopane, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gaylarde, C.; Silva, M.; Warscheid, T. Microbial impact on building materials: An overview. Mater. Struct. 2003, 36, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domsch, K.H.; Gams, W.; Andersen, T.-H. Compendium of Soil Fungi, 1st ed.; Academic Press: London, UK; New York, NY, USA; Toronto, ON, Canada; Sydney, Australia; San Francisco, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hyvärinen, A.; Meklin, T.; Vepsäläinen, A. Fungi and actinobacteria in moisture-damaged building materials—Concentrations and diversity. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2002, 49, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piontek, M. Pleśnie występujące w obiektach budowlanych w województwie lubuskim. In II Ogólnokrajowa Konferencja Naukowa “Rozkład i Korozja Mikrobiologiczna Materiałów Technicznych”, Poland; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Łódzkiej: Łódź, Poland, 2001; pp. 86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Reiß, J. Moulds in the domestic environment. Mycosen 1987, 30, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutarowska, B.; Żakowska, Z. Elaboration and application of mathematical model for estimation of mould contamination of some building materials based on ergosterol content determination. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2002, 49, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flennigan, B. Microbial aerosols in building: Origins, health, implications and controls. In II Konferencja Naukowa “Rozkład i Korozja Mikrobiologiczna Materiałów Technicznych”; Politechnika Łódzka: Łódź, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Żakowska, Z.; Piotrkowska, M.; Gutarowska, B. Grzyby pleśniowe w budynkach—Zagrożenia mikrobiologiczne dla ludzi i zwierząt. In Proceedings of the IV Warsztaty Rzeczoznawcy Mikologiczno—Budowlanego Polskiego Stowarzyszenia Mykologów Budownictwa, Święta Katarzyna, Poland, 23–25 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- PN-89/Z-04111/03. Ochrona Czystości Powietrza. Badania Mikrobiologiczne. Oznaczenia Liczby Grzybów Mikroskopowych w Powietrzu Atmosferycznym (Imisja) Przy Pobieraniu Próbek Metodą Aspiracyjną i Sedymentacyjną; PKN Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny: Warszawa, Poland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Krzysztofik, B. Mikrobiologia Powietrza; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Warszawskiej: Warszawa, Poland, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Doleżał, M.; Doleżał, M.; Pieniążek, M. Grzyby Pleśniowe w Budownictwie Mieszkalnym; Inwestprojekt: Łódź, Poland, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J. Building Mycology: Management of Decay and Health in Buildings, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, M.A.; Alves, M.M.; Azeredo, J.; Mota, M.; Oliveira, R. Influence of physico-chemical properties of porous microcarriers on the adhesion of an anaerobic consortium. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2000, 24, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tran, T.H.; Govin, A.; Guyonnet, R.; Grosseau, P.; Lors, C.; Garcia-Diaz, E.; Damidot, D.; Devès, O.; Ruot, B. Influence of the intrinsic characteristics of mortars on biofouling by Klebsormidium flaccidum. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2012, 70, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- D’Orazio, M.; Cursio, G.; Graziani, L.; Aquilanti, L.; Osimani, A.; Clementi, F.; Yéprémian, C.; Lariccia, V.; Amoroso, S. Effects of water absorption and surface roughness on the bioreceptivity of ETICS compared to clay bricks. Build. Environ. 2014, 77, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrozzi, S.; Dunn, I.J.; Heinzle, E.; Kut, O.M. Carrier influence in anaerobic biofilm fluidized beds for treating vapor condensate from the sulfite cellulose process. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 1991, 69, 527–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirynen, M.B.; Bollen, C.M. The influence of surface roughness and surface-free energy on supra and subgingival plaque formation in man. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1995, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barberoussea, H.; Ruota, B.; Yepremian, C.; Boulon, G. An assessment of façade coatings against colonisation by aerial algae and cyanobacteria. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 2555–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.; Oliveira, R. Influence of surface characteristics on the adhesion of Alcaligenes denitrificans to polymeric substrates. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 1999, 13, 1243–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pekhtasheva, E.L.; Zaikov, G.E.; Neverov, A.N. Biodamage and Biodegradation of Polymeric Materials—New Frontiers—References; Smithers Rapra Technology: North Freedom, WI, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shimp, R.J.; Pfaender, F.K. Effect of surface area and flow rate on marine bacterial growth in activated carbon columns. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1982, 44, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Uchida, E.; Ogawa, Y.; Maeda, N.; Nakagawa, T. Deterioration of stone materials in the Angkor monuments. Eng. Geol. 1999, 55, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.I.; Bhangar, S.; Dannemiller, K.C.; Eisen, J.A.; Fierer, N.; Gilbert, J.A.; Green, J.L.; Marr, L.C.; Miller, S.L.; Siegel, J.A.; et al. Ten questions concerning the microbiomes of buildings. Build. Environ. 2016, 109, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gutarowska, B. Metabolic activity of moulds as a factor of building materials biodegradation. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2010, 59, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, C.P.; Kinney, K.A.; Corsi, R.L.; Szaniszlo, P.J. Resistance of green building materials to fungal growth. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2010, 64, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutarowska, B. Niszczenie materiałów technicznych przez drobnoustroje. LAB Lab. Apar. Bad. 2013, 2, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gutarowska, B.; Janińska, B. Ocena stopnia porażenia pleśniami materiałów budowlanych w określonych warunkach mikroklimatycznych. In Ogólnokrajowa Konferencja Naukowa “Rozkład i Korozja Mikrobiologiczna Materiałów Technicznych”; Politechnika Łódzka: Łódź, Poland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowska, M.; Żakowska, Z.; Bogusławska-Kozłowska, J. Liczba drobnoustrojów jako kryterium stanu zagrzybienia przegród budowlanych. In Proceedings of the VI Sympozjum PSMB “Ochrona obiektów budowlanych przed korozją biologiczną i ogniem”, Wrocław—Szklarska Poręba, Poland, 6–8 September 2001; Volume 2001, pp. 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Currie, C.R. A community of ants, fungi, and bacteria: A multilateral approach to studying symbiosis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2001, 55, 357–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Monds, R.D.; O’Tool, G.A. The developmental model of microbial biofilms: Ten years of a paradigm up for review. Trends Microbiol. 2009, 17, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, H.C.; Wingender, J. The biofilm matrix. Nature reviews. Microbiology 2010, 8, 623–633. [Google Scholar]

- Schlafer, S.; Meyer, R.L. Confocal microscopy imaging of the biofilm matrix. J. Microbiol. Methods 2017, 138, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, P.D. What about biofilms on the surface of stone monuments? Open Conf. Proc. J. 2016, 7, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Negi, A.; Sarethy, I.P. Microbial Biodeterioration of Cultural Heritage: Events, Colonization, and Analyses. Microb. Ecol. 2019, 78, 1014–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanematsu, H.; Barry, D.M. Biofilm and Materials Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanematsu, H.; Barry, D.M. Formation and Control of Biofilm in Various Environments; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Piñar, G.; Sterflinger, K. Microbes and building materials. In Building Materials: Properties, Performance and Applications; Cornejo, D.N., Haro, J.L., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 163–188. [Google Scholar]

- Kakakhel, M.A.; Wu, F.; Gu, J.-D.; Feng, H.; Shah, K.; Wang, W. Controlling biodeterioration of cultural heritage objects with biocides: A review. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2019, 143, 104721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darlington, A. Ecology of Walls; Heinemann: London, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Calvo, J.J.; Arino, X.; Hernandez-Marine, M.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. Factors affecting the weathering and colonization of monuments by phototrophic microorganisms. Sci. Total Environ. 1995, 167, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterflinger, K.; Piñar, G. Microbial deterioration of cultural heritage and works of art—Tilting at windmills? Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 9637–9646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bock, E.; Ahlers, B.; Meyer, C. Biogene Korrosion von Beton und Natursteinen durch Salpetersäure bildende Bakterien. Bauphysik 1989, 4, 141–144. [Google Scholar]

- Ascaso, C.; Sancho, L.; Rodriguez-Pascual, C. Weathering action of saxicolous lichens in maritime Antartica. Polar Biol. 1990, 11, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vourinen, A.; Manterc-Alhonen, S.; Uusinoka, R.; Alhonen, P. Bacterial weathering of Rapakivi granite. J. Geomicrobiol. 1981, 2, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheerer, S.; Ortega-Morales, O.; Gaylarde, C. Microbial deterioration of stone monuments—An updated overview. Adv. Microbiol. 2009, 66, 97–139. [Google Scholar]

- Piñar, G.; Garcia-Valles, M.; Gimeno-Torrente, D.; Fernandez-Turiel, J.L.; Ettenauer, J.; Sterflinger, K. Microscopic, chemical, and molecular-biological investigation of the decayed medieval stained window glasses of two Catalonian churches. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2013, 84, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Haliem, M.E.F.; Sakr, A.A.; Ali, M.F.; Ghaly, M.F.; Sohlenkamp, C. Characterization of Streptomyces isolates causing colour changes of mural paintings in ancient Egyptian tombs. Microbiol. Res. 2013, 168, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaarakainen, P.; Rintala, H.; Vepsalainen, A.; Hyvarinene, A.; Nevalainen, A.; Meklin, T. Microbial content of house dust samples determined with qPCR. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 4673–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konkol, N.R.; McNamara, C.J.; Hellman, E.; Mitchell, R. Early detection of fungal biomass on library materials. J. Cult. Herit. 2012, 13, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Meng, H.; Wang, Y.; Katayama, Y.; Gu, J.D. Water is a critical factor in evaluating and assessing microbial colonization and destruction of Angkor sandstone monuments. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 2018, 133, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarela, M.; Alakomi, H.L.; Suihko, M.L.; Maunuksela, L.; Raaska, L.; Mattila-Sandholm, T. Heterotrophic microorganisms in air and biofilm samples from Roman catacombs, with special emphasis on actinobacteria and fungi. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2004, 54, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellezza, S.; Paradossi, G.; De Philippis, R.; Albertano, P. Leptolyngbya strains from Roman hypogea: Cytochemical and physico-chemical characterisation of exopolysaccharides. J. Appl. Phycol. 2003, 15, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leo, F.; Iero, A.; Zammit, G.; Urzi, C.E. Chemoorganotrophic bacteria isolated from biodeteriorated surfaces in cave and catacombs. Int. J. Speleol. 2012, 41, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gaylarde, C.C.; Rodrıguez, C.H.; Navarro, N.Y.; Ortega, M.B. Microbial biofilms on the sandstone monuments of the Angkor Wat Complex, Cambodia. Curr. Microbiol. 2012, 64, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadd, G. Geomycology: Biogeochemical transformations of rocks, minerals, metals and radionuclides by fungi, bioweathering and bioremediation. Mycol. Res. 2007, 111, 3–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragon, M.; Restoux, G.; Moreira, D.; Møller, A.P.; Lopez-Garcia, P. Sunlight-exposed biofilm microbial communities are naturally resistant to Chernobyl ionizing-radiation levels. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, 21764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gadd, G. Metals, minerals and microbes: Geomicrobiology and bioremediation. Microbiology 2010, 156, 609–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehrmann, C.; Krumbein, W.E. Interactions between Epilithic and Endolithic Lichens and Carbonate Rock. In Proceedings of the Third International Symposium on the Conservation of Monuments in the Mediterranean Basin, Venice, Italy, 22–25 June 1994; Volume 1994, pp. 311–316. [Google Scholar]

- Gaylarde, C.C.; Morton, L.H.G. Biodeterioration of Mineral Materials; Encyclopedia of Environmental Microbiology Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 516–527. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Calvo, J.J.; Arino, X.; Stal, L.J.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. Cyanobacterial sulfate accumulation from black crusts of a historic building. J. Geomicrobiol. 1994, 12, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, B.; Rivas, T.; Silva, B.; Carballa, R.; de Lopez Silanes, E. Colonization by lichens of granite dolmes in Galicia (NW Spain). Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 1994, 34, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romao, P.M.S.; Rattazzi, A. Biodeterioration on megalithic monuments—Study of lichen’s colonization on Tapadao and Zambujeiro Dolmens (Southern Portugal). Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 1996, 37, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, R.J.; Hirsch, P., Jr. Photosynthesis-based microbial communities on two churches in Northern Germany: Weathering of granite and glazed brick. Geomicrobiol. J. 1991, 9, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danin, A.; Gerson, R.; Marton, K.; Garty, J. Patterns of limestone and dolomite weathering by lichens and blue-green algae and their palaeoclimatic significance. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 1982, 37, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuhoglu, Y.; Oguz, E.; Uslu, H.; Ozbek, A.; Ipekoglu, B.; Ocak, I.; Hasenekoglu, I. The accelerating effects of the microorganisms on biodeterioration of stone monuments under air pollution and continental-cold climatic conditions in Erzurum, Turkey. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 364, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosling, A.; Finlay, R.D.; Gadd, G.M. Geomycology. In Fungal Applications in Sustainable Environmental Biotechnology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2009; Volume 23, pp. 91–93. [Google Scholar]

- Sterflinger, K.; Prillinger, H. Molecular taxonomy and biodiversity of rock fungal communities in an urban environment (Vienna, Austria). Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2001, 80, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterflinger, K. Black yeasts and meristematic fungi: Ecology, diversity and identification. In Yeast Handbook: Biodiversity and Ecophysiology of Yeasts; Rosa, C., Gabor, P., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; Volume 1, pp. 505–518. [Google Scholar]

- Urzi, C.E.; Krumbein, W.E.; Warscheid, T. On the question of biogenic colour changes of mediterranean monuments (coating-crust-microstromatolite-patina-scialbatura-skin-rock varnish). In Proceedings of the Second International Symptom Conservation of Monuments in Mediterranean Basins, Geneva, Switzerland, 19–21 November 1992; pp. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- Warscheid, T. Impacts of microbial biofilms in the deterioration of inorganic building materials and their relevance for the conservation practice. Int. Z. Bauinstandsetz. 1996, 2, 493–504. [Google Scholar]

- Warscheid, T.; Krumbein, W.E. Biodeterioration of inorganic nonmetallic materials—General aspects and selected cases. In Microbially Induced Corrosion of Materials; Heitz, H., Sand, W., Flemming, H.C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1996; pp. 273–295. [Google Scholar]

- Gaylarde, C.C.; Morton, L.H.G. Deteriogenic biofilms on buildings and their control: A review. Biofouling 1999, 14, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, M.; Wolf, F.; Dannecker, W. Deposition and Enrichment of Atmospheric Pollutants on Building Stones as Determined by Field Exposure Experiments; Conservation of Stone and Other Materials; Thiel, M.-J., Ed.; E & FN Spon: London, UK, 1993; Volume 1, pp. 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Piñar, G.; Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Sterflinger, K.; Ettenauer, J.; Jroundi, F.; Fernandez-Vivas, A.; Gonzalez-Munoz, M.T. Bacterial community dynamics during the application of a Myxococcus xanthus-inoculated culture medium used for consolidation of ornamental limestone. Microb. Ecol. 2010, 60, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Rodriguez-Navarro, C.; Piñar, G.; Carrillo-Rosua, F.J.; Rodriguez-Gallego, M.; Gonzalez-Muñoz, M.T. Consolidation of degraded ornamental porous limestone stone by calcium carbonate precipitation induced by the microbiota inhabiting the stone. Chemosphere 2007, 68, 1929–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amoroso, G.G.; Fassina, V. Stone Decay and Conservation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Saiz-Jimenez, C.; Laiz, L. Occurrence of halotolerant/halophilc bacterial communities in deteriorated monuments. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2000, 46, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warscheid, T.; Braams, J. Biodeterioration of stone: A review. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2000, 46, 343–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Microorganisms | Water Activity |

|---|---|

| G(−) bacteria, some yeasts | 0.95 |

| Sea algae | 0.92 |

| Vegetative cells, certain molds | 0.91 |

| Staphylococci | 0.85 |

| most yeasts | 0.88 |

| most molds | 0.80 |

| halophytic: bacteria, algae | 0.75 |

| osmophilic yeasts, xerophilic molds | 0.60 |

| Microorganisms | Min. | Optimal | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychofiles (grow best at relatively low temperatures) | >0 | 10–15 | <20 |

| Psychotropes (capable of growing at low temperatures, preferring moderate temperatures) | >0 | 25 | 15–30 |

| Mesophiles (most bacteria mainly coexist with warm-blooded organisms) | 10–15 | 30–40 | <45 |

| Thermofiles (including extreme Thermofiles, a group with high temperature variation) | 45 | 50–85 | <100 |

| Hyperthermophiles | 45 | 80–100 | 110 |

| Photoautotrophs | Chemotrophs | |

|---|---|---|

| energy source: solar energy; carbon source: CO2; electron source: inorganic compounds; environmental development: there may be no organic compounds; development: allows for the appearance of chemoorganotrophic microorganisms; microorganisms: anaerobic phototrophic bacteria, e.g., purple sulfuric bacteria and aerobic phototrophic microorganisms, e.g., algae or cyanobacteria | energy source: as a result of oxidative transformations of inorganic and organic chemicals. carbon source: CO2 or organic compounds. | |

| chemolitotrophs | chemoorganotrophs | |

| the energy source: from reduced inorganic compounds such as sulfur and nitrogen compounds; electron source: reduced compounds/ion such as CO2, H2S or Fe2+; microorganisms: sulfuric, nitrifying, ferrous and other bacteria. | products of transformation: mostly aggressive (organic and inorganic acids) in relation to building materials. energy source, carbon, electrons: organic compounds; microorganisms: all fungi, certain bacteria, as well as protozoa | |

| Air/Conditions of Occurrence | According to | Permissible Contamination (cfu/m3) |

|---|---|---|

| Atmospheric | PN-89/Z-04111/03 [36] | 3000 ÷ 5000 |

| Bedroom | Krzysztofik et al. [37] | ≤100 |

| Kitchen | ≤300 | |

| Very good mycological purity, there is multi-species microflora | Doleżał et al. [38] | 100 ÷ 300 |

| General Hygiene anomaly—indication for further investigation | >500 | |

| Very high contamination, active mold process, predominance of fungi species | 105 ÷ 106 (up to an uncountable amount) |

| Technical Material | Destruction Mechanism | Effects, Destruction |

|---|---|---|

| mineral building materials (stone, concrete, brick, mortar, glass) | corrosion induced by microorganisms, surface formation | crushing, cracking, decay, dissolving, fouling, tarnish, color changes, pitting, changes in heat and moisture transfer, weight loss |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stanaszek-Tomal, E. Environmental Factors Causing the Development of Microorganisms on the Surfaces of National Cultural Monuments Made of Mineral Building Materials—Review. Coatings 2020, 10, 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings10121203

Stanaszek-Tomal E. Environmental Factors Causing the Development of Microorganisms on the Surfaces of National Cultural Monuments Made of Mineral Building Materials—Review. Coatings. 2020; 10(12):1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings10121203

Chicago/Turabian StyleStanaszek-Tomal, Elżbieta. 2020. "Environmental Factors Causing the Development of Microorganisms on the Surfaces of National Cultural Monuments Made of Mineral Building Materials—Review" Coatings 10, no. 12: 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings10121203

APA StyleStanaszek-Tomal, E. (2020). Environmental Factors Causing the Development of Microorganisms on the Surfaces of National Cultural Monuments Made of Mineral Building Materials—Review. Coatings, 10(12), 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings10121203