The Mechanical Performance Enhancement of the CrN/TiAlCN Coating on GCr15 Bearing Steel by Controlling the Nitrogen Flow Rate in the Transition Layer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Methods

2.1. Coating Deposition

2.2. Coating Characterization

2.3. Nanoindentation and Scratch Test

2.4. Sliding Friction Test

3. Results and Discussion

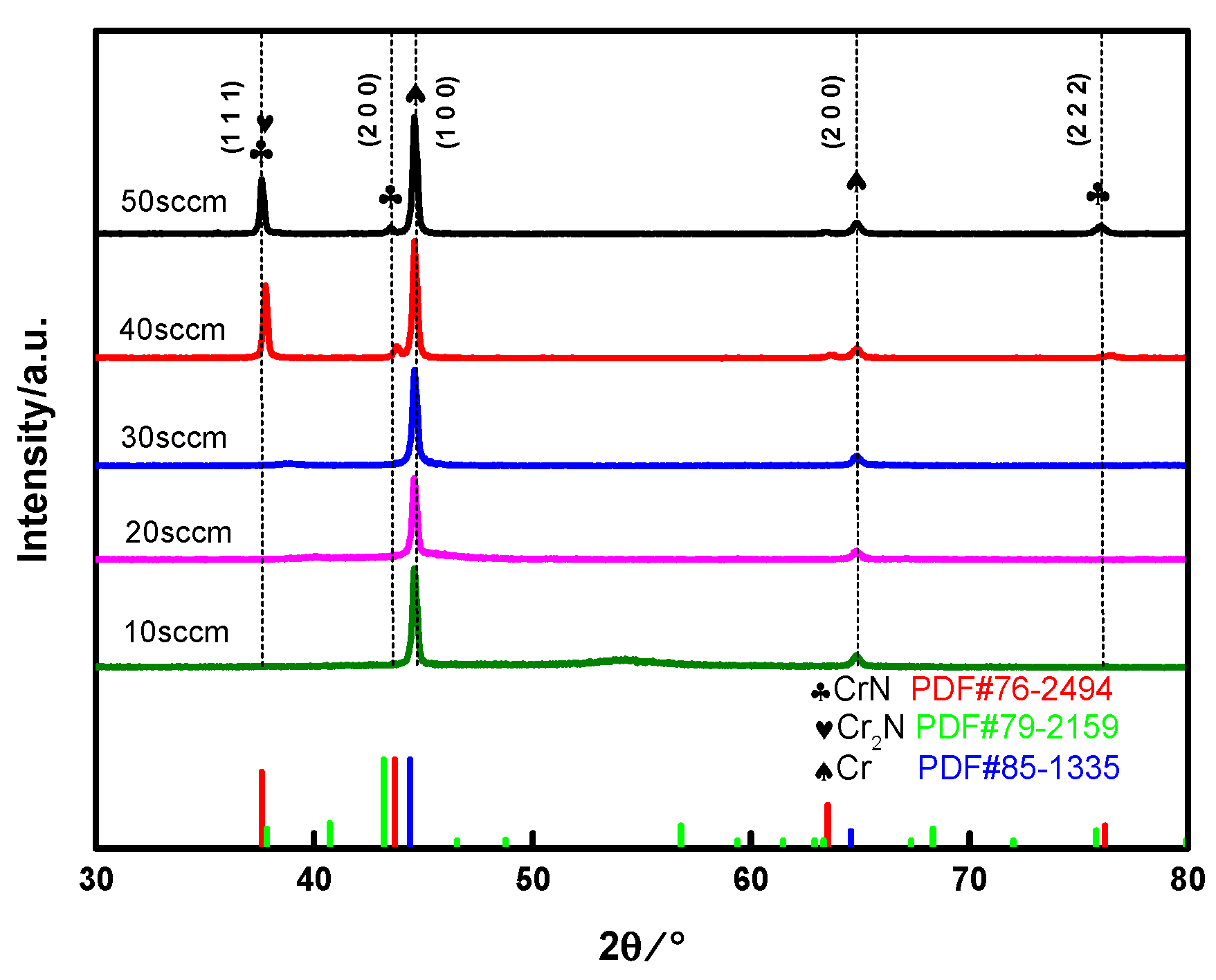

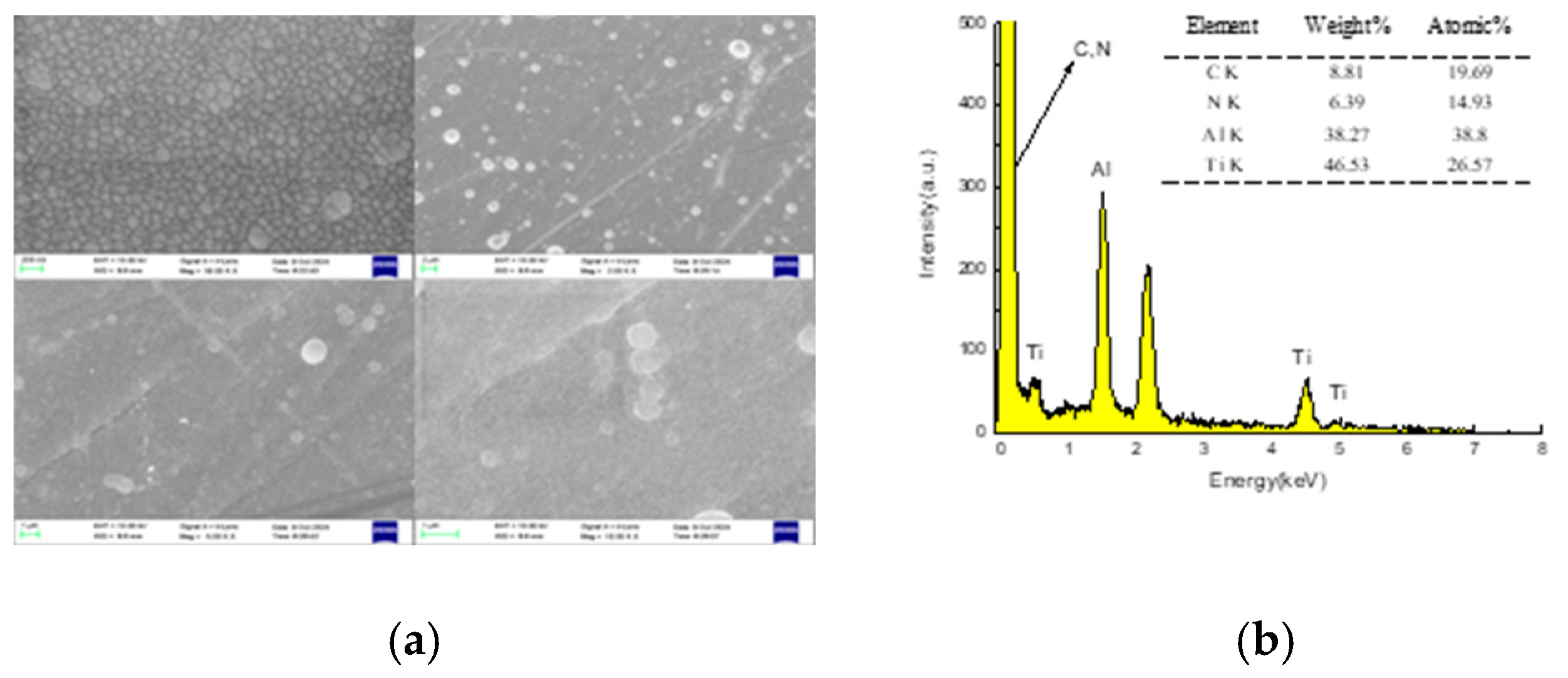

3.1. Coating Surface Morphology

3.2. The Nanomechanical Characterization of the Coatings

3.2.1. Nanohardness Measurement

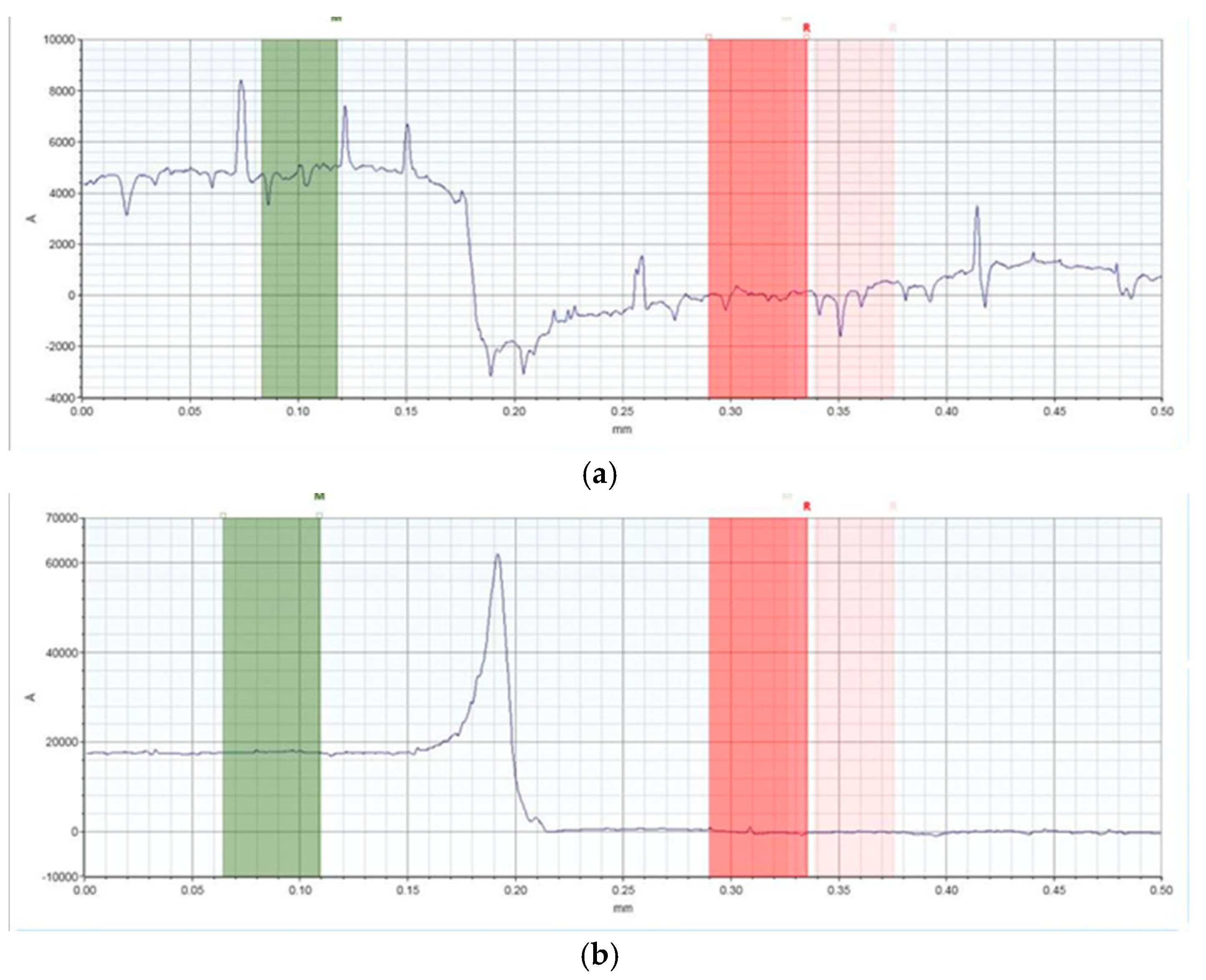

3.2.2. The Scratch Behavior of the Coatings

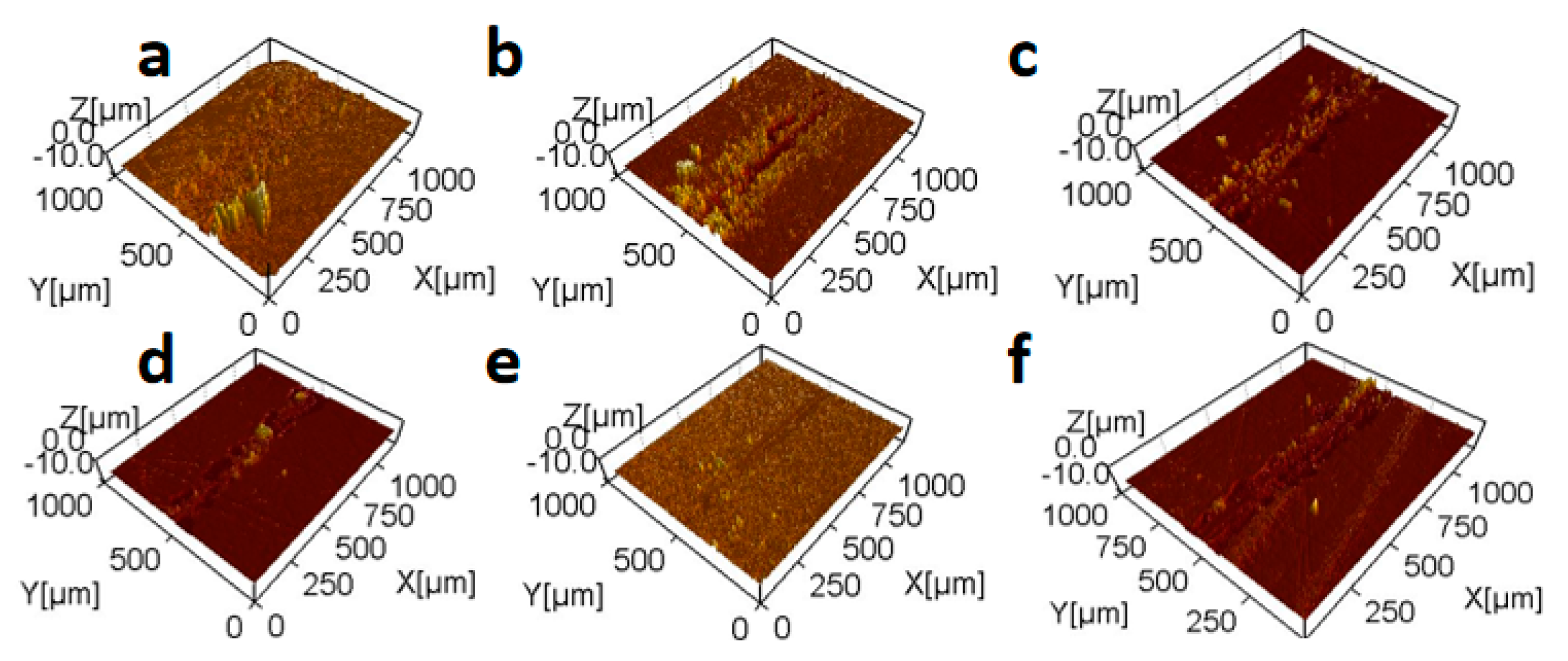

3.3. The Tribological Characterization of the Coatings

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The addition of the CrN transition layer between the TiAlCN coating and the substrate effectively strengthened the physical properties of the composite coating.

- (2)

- As the N2 flow rate increased, the hardness and elastic modulus of the coating initially rose and then gradually declined. The hardness peaked at 23.3 GPa when the N2 flow rate reached 40 sccm.

- (3)

- The continuous rise in the N2 flow rate increased the nitride content in the CrN transition layer, making the TiAlCN coating quite compatible with the substrate.

- (4)

- The friction coefficient and wear rate of the CrN/TiAlCN coating decreased with the continuous rise in the N2 flow rate, and the values reached 0.27 and 0.19 × 10−7 mm3/N·m, respectively, at a N2 flow rate of 40 sccm, yielding the best performance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, T.; Song, G.; Shao, R.; Du, S.; Zhang, Y. Sliding Friction and Wear Properties of GCr15 Steel under Different Lubrication Conditions. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2022, 31, 7653–7661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Li, B.; Pueh, L.H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y. Effect of single/multi-particle grinding parameters on surface properties of bearing steel GCr15. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2024, 58, 101851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Bai, H.; Li, R.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhao, N.; Xu, Y. Microstructure and bond strength of niobium carbide coating on GCr15 prepared by in-situ hot press sintering. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 4843–4851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yuan, W.; Guo, Q.; Wang, N.; Chi, B.; Yu, J. Effect of picosecond laser surface texturing under Babbitt coating mask on friction and wear properties of GCr15 bearing steel surface. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 157, 107878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Shan, R.; Wang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Cui, Z.; Liu, H.; Yan, H. Bonding properties and corrosion resistance of TaC-Fe enhanced layer on GCr15 surface prepared by in-situ hot pressing. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 940, 168489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wang, L.; Shang, L.; Zhang, G.; Li, C. Temperature-dependent tribological behavior of CrAlN/TiSiN tool coating sliding against 7A09 Al alloy and GCr15 bearing steel. Tribol. Int. 2023, 177, 107942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakib, S.E.; Babakhani, A.; Torbati, M.K. Nanomechanical assessment of tribological behavior of TiN/TiCN multi-layer hard coatings deposited by physical vapor deposition. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 25, 1344–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Guo, J.; Yang, Y.; Geng, K.; Xiang, M.; Zhu, Q.; Hu, C.; Zhao, H. Fe 2 Ti interlayer for improved adhesion strength and corrosion resistance of TiN coating on stainless steel 316L. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 504, 144483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Bukhaiti, M.A.; Al-hatab, K.A.; Tillmann, W.; Hoffmann, F.; Sprute, T. Tribological and mechanical properties of Ti/TiAlN/TiAlCN nanoscale multilayer PVD coatings deposited on AISI H11 hot work tool steel. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 318, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, G.; Lü, W.; Liu, S.; Deng, J.; Wang, Q. High-temperature resistance and self-lubricating TiAlTaCN nanocomposite hard coating by synergistic interaction of TiAlN (C) and TaN (C) phases. Corros. Sci. 2024, 227, 111687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Ma, F.; Lou, M.; Dong, M.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, X.; Li, J. Structure and tribocorrosion behavior of TiAlCN coatings with different Al contents in artificial seawater by multi-arc ion plating. Surf. Topogr. Metrol. Prop. 2021, 9, 045004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.N.; Zhao, Y.M.; Zhang, Y.F.; Chen, L.; Liao, B.; Zhang, X.; Ouyang, X.P. Influence of carbon content on the structure and tribocorrosion properties of TiAlCN/TiAlN/TiAl multilayer composite coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 411, 126886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shen, Y.Q.; Zhao, Y.M.; Chen, S.N.; Ouyang, X.; Zhang, X.; Liang, H.; Liao, B.; Chen, L. Structure control of high-quality TiAlN Monolithic and TiAlN/TiAl multilayer coatings based on filtered cathodic vacuum arc technique. Surf. Interfaces 2023, 38, 102836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.; Kumar, M.; Ankah, N.; Abdelaal, A. Surface, mechanical, and in vitro corrosion properties of arc-deposited TiAlN ceramic coating on biomedical Ti6Al4V alloy. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2023, 33, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Mao, X.; Tan, S.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Jiang, J. Superhard TiAlCN coatings prepared by radio frequency magnetron sputtering. Thin Solid Film. 2015, 584, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavol, Š.; Ľuboš, M.; Roman, P.; Miroslav, B.; Ernest, G. Wear of TiAlCN Coating on HCR Gear. Lubricants 2022, 10, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, N.; Figueiredo, M.R.d.; Franz, R.; Kainz, C.; López, J.C.S.; Rojas, T.C.; Reyes, D.F.d.l.; Colominas, C.; Abad, M.D. Microstructural and mechanical properties of TiN/CrN and TiSiN/CrN multilayer coatings deposited in an industrial-scale HiPIMS system: Effect of the Si incorporation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 494, 131461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolawole, F.O.; Kolawole, S.K.; Fukumasu, N.K.; Varela, L.B.; Vencovsky, P.K.; Ludewigs, D.A.; Souza, R.M.d.; Tschiptschin, A.P. Elevated Temperature Tribological Behavior of Duplex Layer CrN/DLC and Nano Multilayer DLC-W Coatings Deposited on Carburized and Hardened 16MnCr5 Steel. Coatings 2024, 14, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenchuk, N.V.; Kolubaev, A.V.; Sizova, O.V.; Denisova, Y.A.; Leonov, A.A. Structure and Properties of Multilayer CrN/TiN Coatings Obtained by Vacuum-Arc Plasma-Assisted Deposition on Copper and Beryllium Bronze. Russ. Phys. J. 2023, 66, 1077–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Liu, J.; Li, W. Microstructures, mechanical and tribological properties of NbN/MoS2 nanomultilayered films deposited by reactive magnetron sputtering. Vacuum 2019, 160, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movassagh-Alanagh, F.; Mahdavi, M. Improving wear and corrosion resistance of AISI 304 stainless steel by a multilayered nanocomposite Ti/TiN/TiSiN coating. Surf. Interfaces 2020, 18, 100428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhi, J.; Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Hei, H.; Yu, S. Effect of modulation ratio on microstructure and tribological properties of TiAlN/TiAlCN multilayer coatings prepared by multi-excitation source plasma. Vacuum 2023, 211, 111917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, K. Improving the adhesion of CrN coatings on TC4 alloy substrates by discharge current modulation in magnetron sputtering. Surf. Eng. 2023, 39, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tian, X.-B.; Zhao, Z.-W.; Gao, J.-B.; Zhou, Y.-W.; Gao, P.; Guo, Y.-Y.; Lv, Z. Evaluation of the adhesion and failure mechanism of the hard CrN coatings on different substrates. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 364, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieske, M.; Börner, R.; Schubert, A. Influence of the surface microstructure on the adhesion of a CVD-diamond coating on steel with a CrN interlayer. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 190, 14008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Luo, G.; Xu, X.; Dong, H.; Wei, Q.; Tian, F.; Qin, J.; Shen, Q. Enhance the tribological performance of soft AISI 1045 steel through a CrN/W-DLC/DLC multilayer coating. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 485, 130916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badillo, J.A.H.; Casco, I.H.; Hernández, H.H.; Vargas, O.S.; Pacheco, A.D.C.; Morán, C.O.G.; Hernández, J.M.; Cuautle, J.d.J.A.F. A Tribological Study of CrN and TiBN Hard Coatings Deposited on Cobalt Alloys Employed in the Food Industry. Coatings 2024, 14, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayana, T.; Saleem, S.S. Comparative investigation and characterization of the nano-mechanical and tribological behavior of RF magnetron sputtered TiN, CrN, and TiB2 coating on Ti6Al4V alloy. Tribol. Int. 2024, 193, 109348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrey, F.; Andrey, V.; Nickolay, S.; Evgeny, M.; Olga, N.; Evgeny, K.; Yuliya, D.; Andrei, L.; Vladimir, D.; Sergei, T. Dry Sliding Friction Study of ZrN/CrN Multi-Layer Coatings Characterized by Vibration and Acoustic Emission Signals. Metals 2022, 12, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Liang, W.; Miao, Q.; Lin, H.; Yi, J.; Gao, X.; Song, Y. Characterization of a CrN/Cr gradient coating deposited on carbon steel and synergistic erosion-corrosion behavior in liquid–solid flow impingement. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 33925–33933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, P.; Peter, G.; Matjaž, P.; Tonica, B.; Aljaž, D.; Mihaela, A.; Miha, Č.; Franc, Z. Microstructure and Surface Topography Study of Nanolayered TiAlN/CrN Hard Coating. Coatings 2022, 12, 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, A.; Aliyu, A. Structural and mechanical properties of Si-doped CrN coatings deposited by magnetron sputtering technique. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfgang, T.; Diego, G.; Dominic, S.; Arne, T.C.; Jörg, D.; Alexander, N.; Daniel, A. Residual stresses and tribomechanical behaviour of TiAlN and TiAlCN monolayer and multilayer coatings by DCMS and HiPIMS. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 406, 126664. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Li, G.; Lü, W.; Liu, S.; Li, C.; Wang, Q. Controllable high adhesion and low friction coefficient in TiAlCN coatings by tuning the C/N ratio. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 597, 153542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Duan, H.; Li, X. The influence of plasma nitriding on microstructure and properties of CrN and CrNiN coatings on Ti6Al4V by magnetron sputtering. Vacuum 2017, 136, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, C.; Chen, Q.; Yang, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, R.; He, L.; Long, J.; et al. Microstructure, high-temperature corrosion and steam oxidation properties of Cr/CrN multilayer coatings prepared by magnetron sputtering. Corros. Sci. 2021, 191, 109755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, W.; Shen, M.; Zhu, S. A comparative study of the electrochemical corrosion behavior between Cr2N and CrN coatings. Heat Treat. Surf. Eng. 2022, 4, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; He, L.I.; Xia, L.U.; Chen, J. Structure and mechanical properties of thick r/Cr2N/CrN multilayer coating deposited by multi-arc ion plating. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2015, 25, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar]

- Tillmann, W.; Grisales, D.; Tovar, C.M.; Contreras, E.; Apel, D.; Nienhaus, A.; Stangier, D.; Dias, N.F. Tribological behaviour of low carbon-containing TiAlCN coatings deposited by hybrid (DCMS/HiPIMS) technique. Tribol. Int. 2020, 151, 106528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N.; Zhu, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, F.; Shen, M.; Li, H. Preparation and Performance of a Cr/CrN/TiAlCN Composite Coating on a GCr15 Bearing Steel Surface. Coatings 2024, 14, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharani, G.S.; Sumitra, S. Magnetron Sputtered Thin Films Based on Transition Metal Nitride: Structure and Properties. Phys. Status Solidi 2023, 220, 2200229. [Google Scholar]

- Hassani, S.; Raeissi, K.; Azzi, M.; Li, D.; Golozar, M.A.; Szpunar, J.A. Improving the corrosion and tribocorrosion resistance of Ni–Co nanocrystalline coatings in NaOH solution. Corros. Sci. 2009, 51, 2371–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, K. Wear in relation to friction—A review. Wear 2000, 241, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Cr (at%) | N (at%) |

|---|---|---|

| 10 sccm | 89.81 | 10.19 |

| 20 sccm | 75.33 | 24.67 |

| 30 sccm | 70.68 | 29.32 |

| 40 sccm | 56.9 | 43.1 |

| 50 sccm | 59.99 | 40.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, F.; Li, H.; Yan, N. The Mechanical Performance Enhancement of the CrN/TiAlCN Coating on GCr15 Bearing Steel by Controlling the Nitrogen Flow Rate in the Transition Layer. Coatings 2025, 15, 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15030254

Cheng Y, Li J, Liu F, Li H, Yan N. The Mechanical Performance Enhancement of the CrN/TiAlCN Coating on GCr15 Bearing Steel by Controlling the Nitrogen Flow Rate in the Transition Layer. Coatings. 2025; 15(3):254. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15030254

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Yuchuan, Junxiang Li, Fang Liu, Hongjun Li, and Nu Yan. 2025. "The Mechanical Performance Enhancement of the CrN/TiAlCN Coating on GCr15 Bearing Steel by Controlling the Nitrogen Flow Rate in the Transition Layer" Coatings 15, no. 3: 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15030254

APA StyleCheng, Y., Li, J., Liu, F., Li, H., & Yan, N. (2025). The Mechanical Performance Enhancement of the CrN/TiAlCN Coating on GCr15 Bearing Steel by Controlling the Nitrogen Flow Rate in the Transition Layer. Coatings, 15(3), 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15030254