Study on the Properties of Plastic Fillers in Carbon Dioxide Capture System Under High Temperature and High Pressure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiment Section

2.1. Raw Materials

2.2. Sample Preparation and Experimental Methods

2.2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2.2. Experimental Method

2.3. Performance Testing and Characterization

2.3.1. Quality Rate of Change Testing

2.3.2. Volume Rate of Change Test

2.3.3. Stretch Test

2.3.4. Fourier Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Testing

2.3.5. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Test

2.3.6. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) Test

2.3.7. Vica Softening Temperature Test

2.3.8. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

2.4. Experimental Equipment

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chlorinated Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC-C) Corrosion Resistance at High Temperature and Pressure

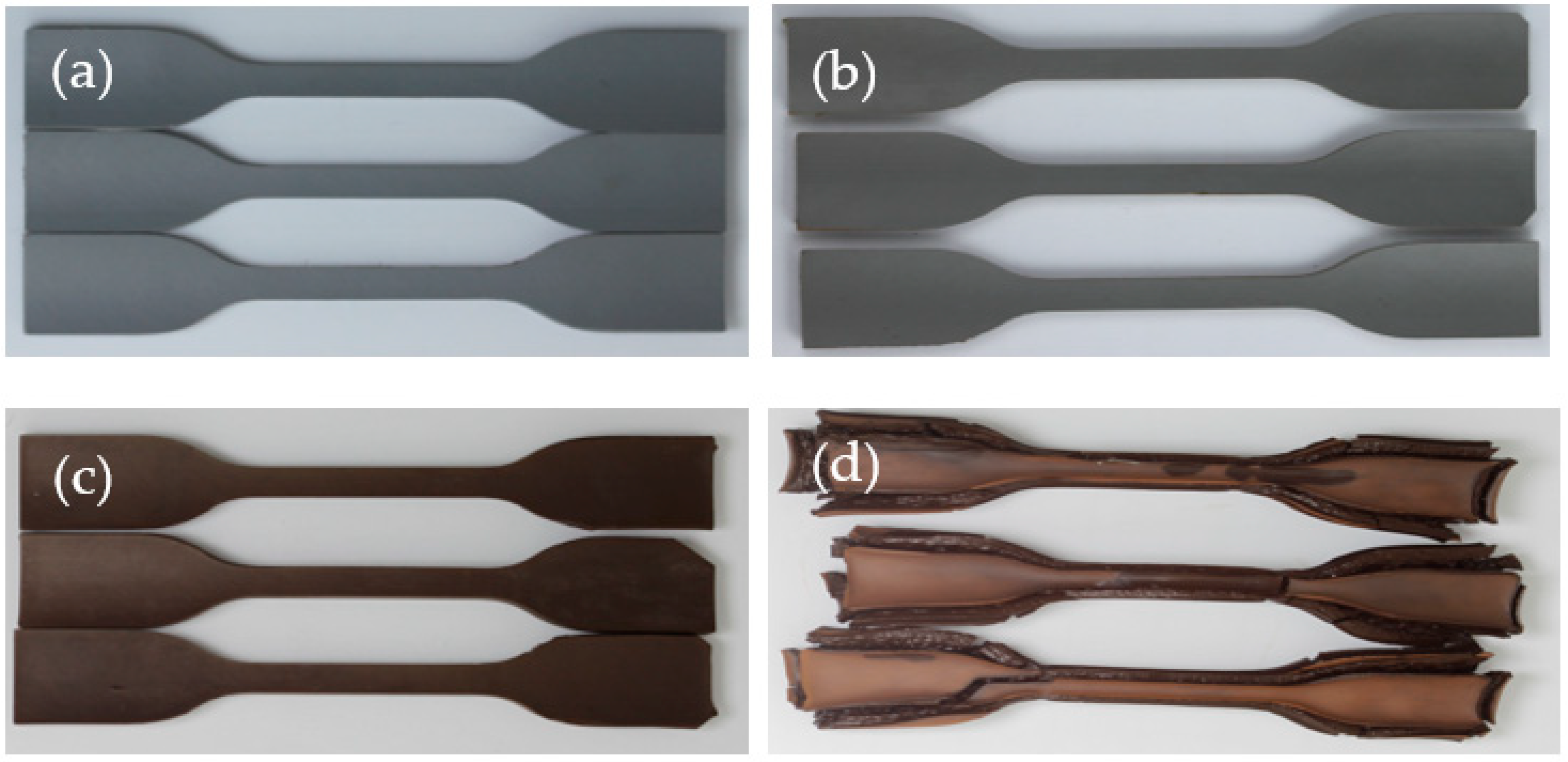

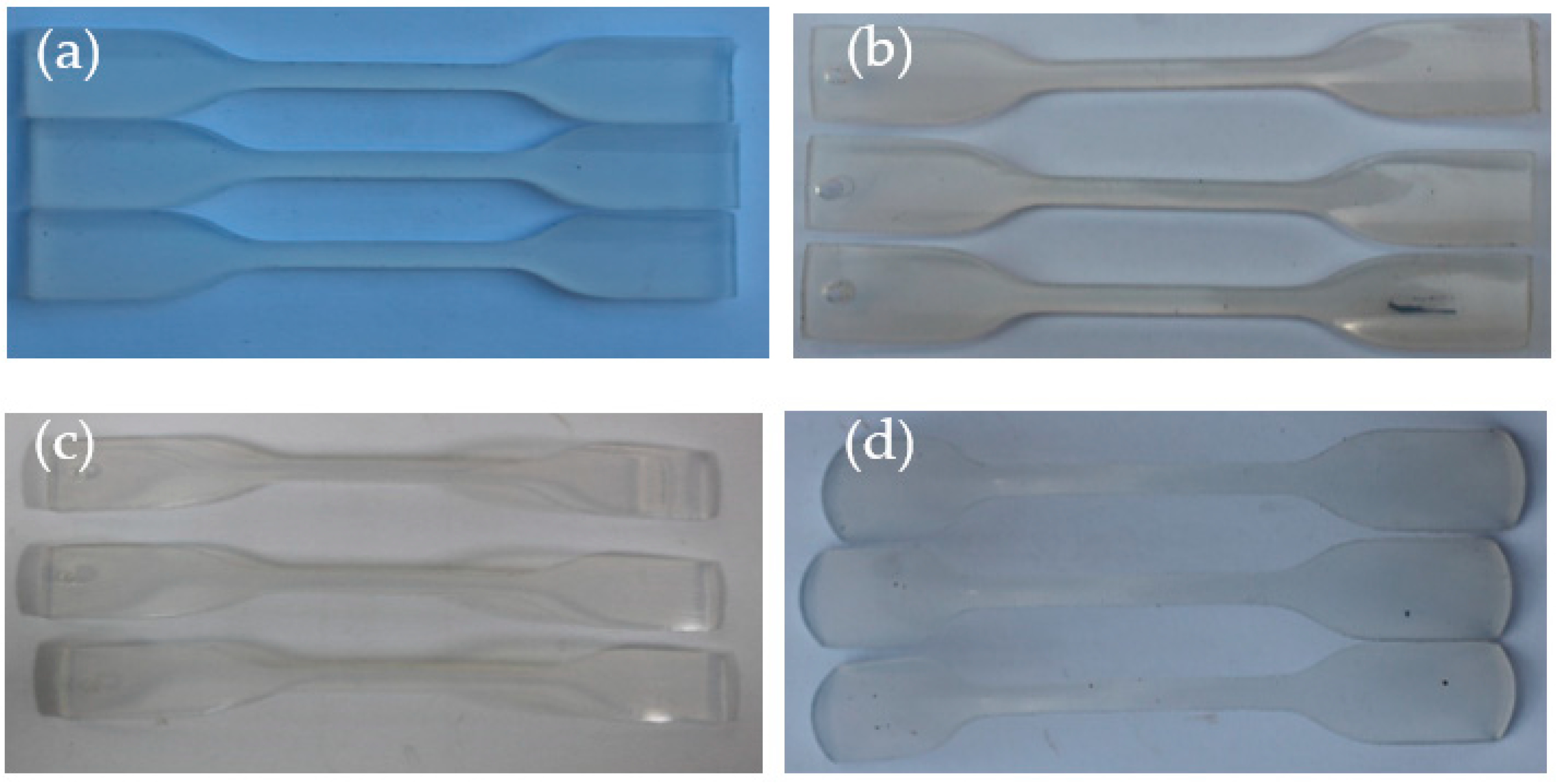

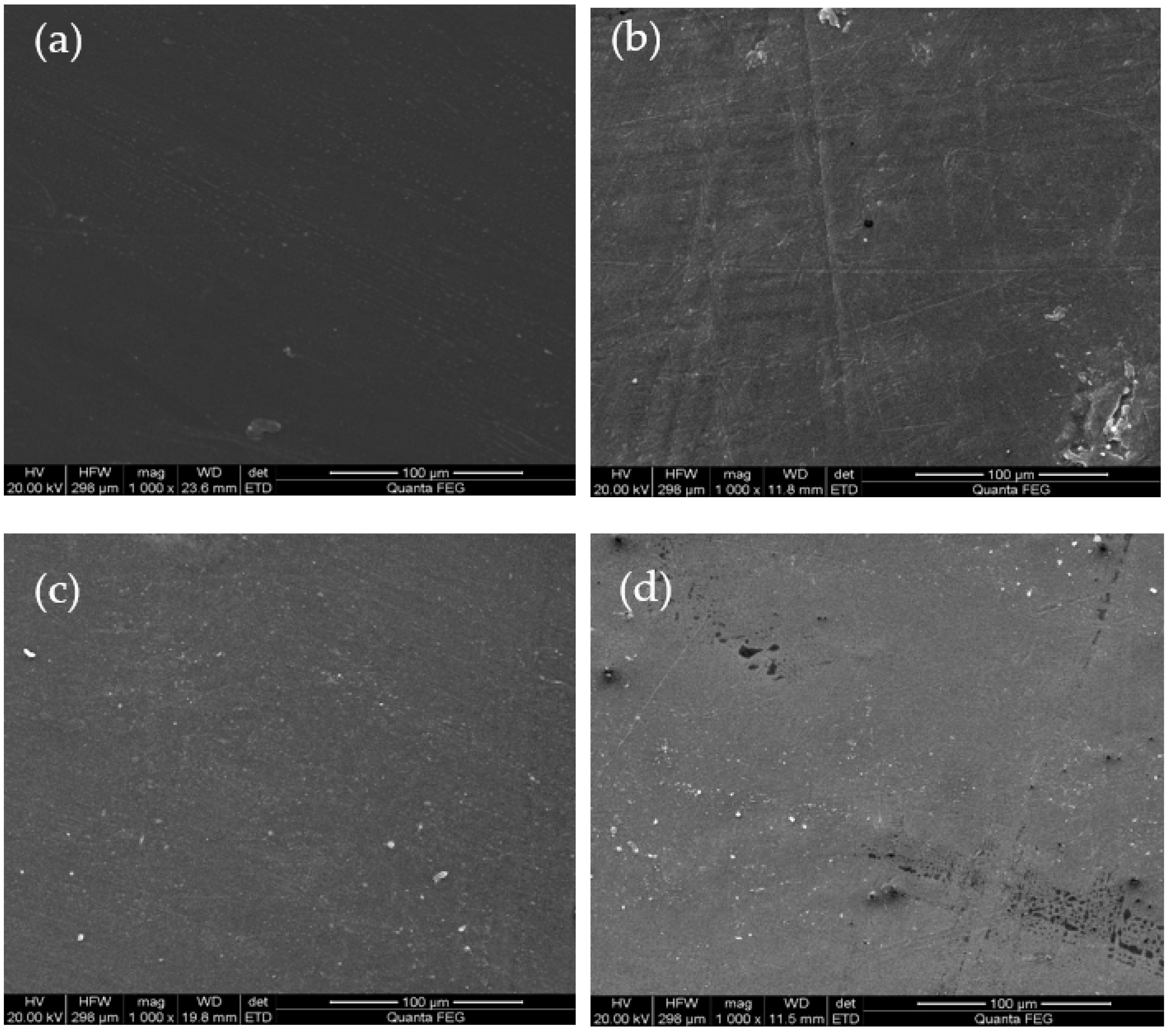

3.1.1. Morphological Changes

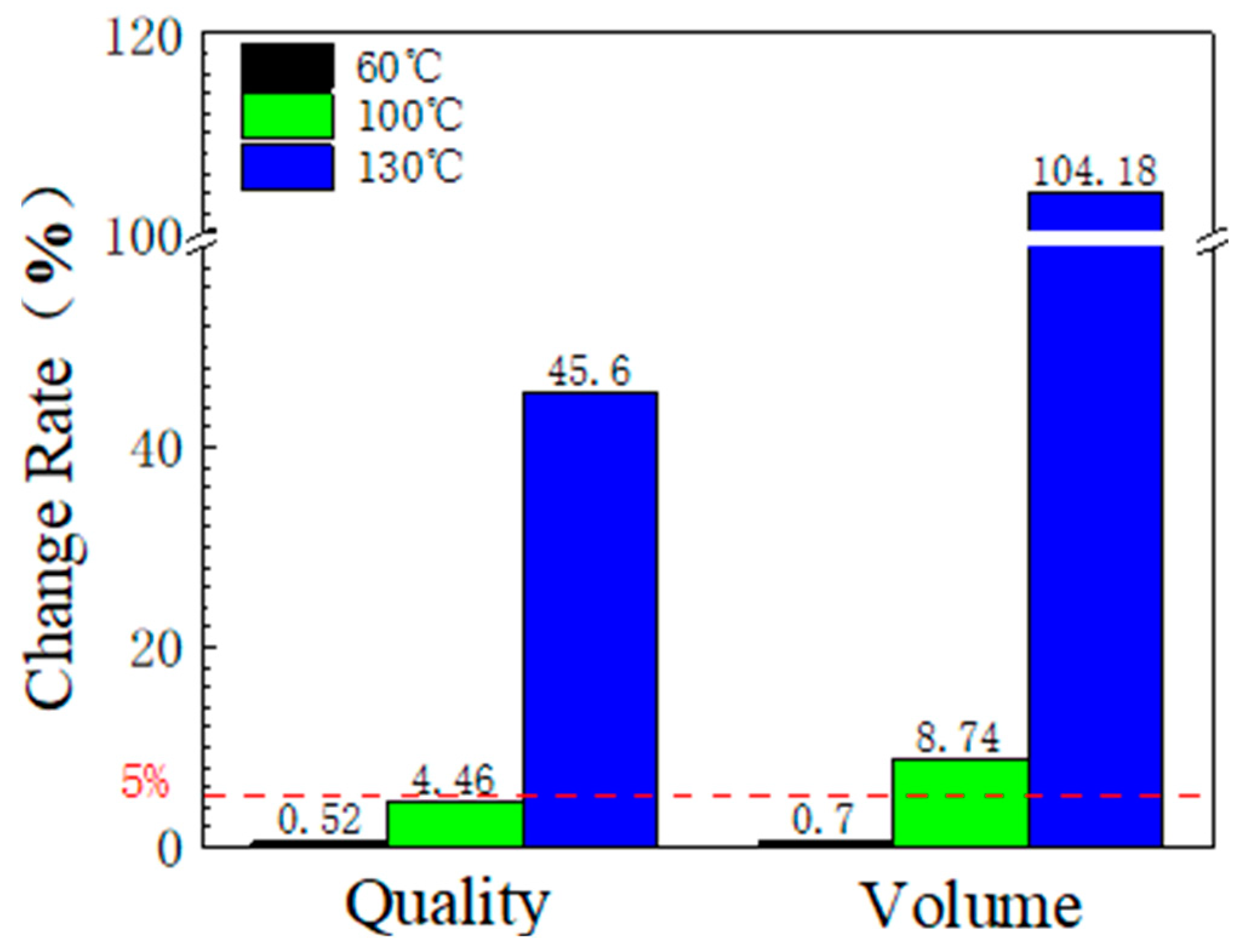

3.1.2. Mass and Volume Change

3.1.3. Mechanics and Change of Softening Temperature of Vicat

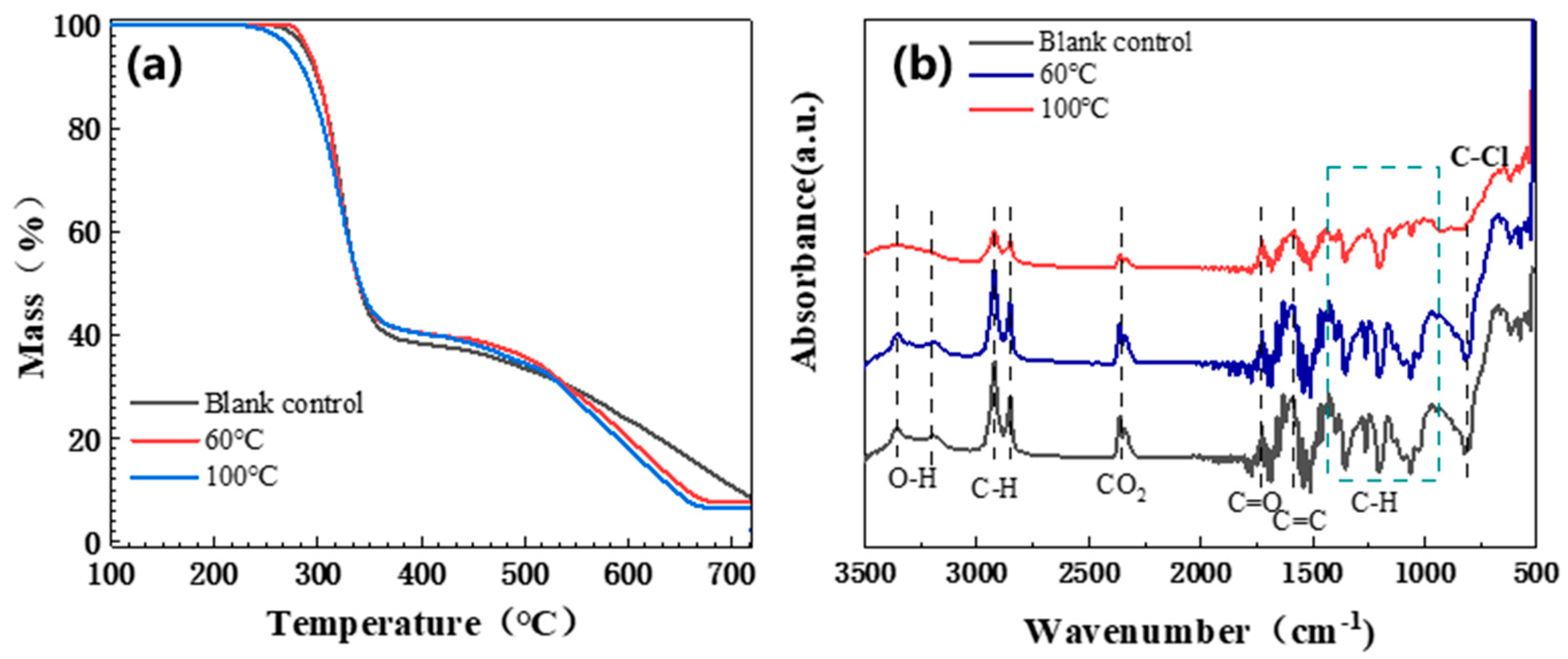

3.1.4. Other Performance Changes

3.1.5. Aging Mechanism Analysis

3.2. Polypropylene (PP) High Temperature and High Pressure Corrosion Resistance

3.2.1. Morphological Changes

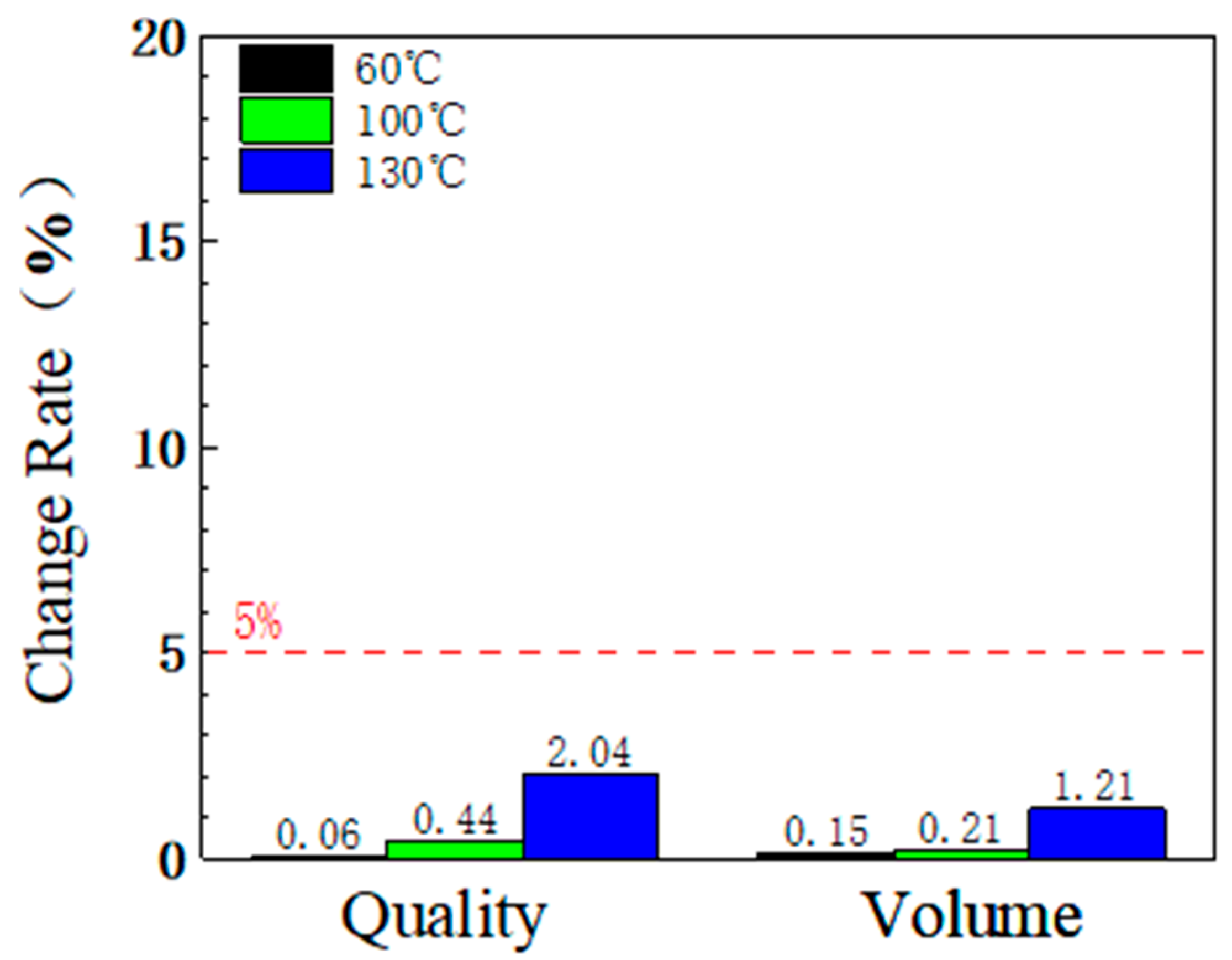

3.2.2. Mass and Volume Changes

3.2.3. Mechanics and Change of Softening Temperature of Vicat

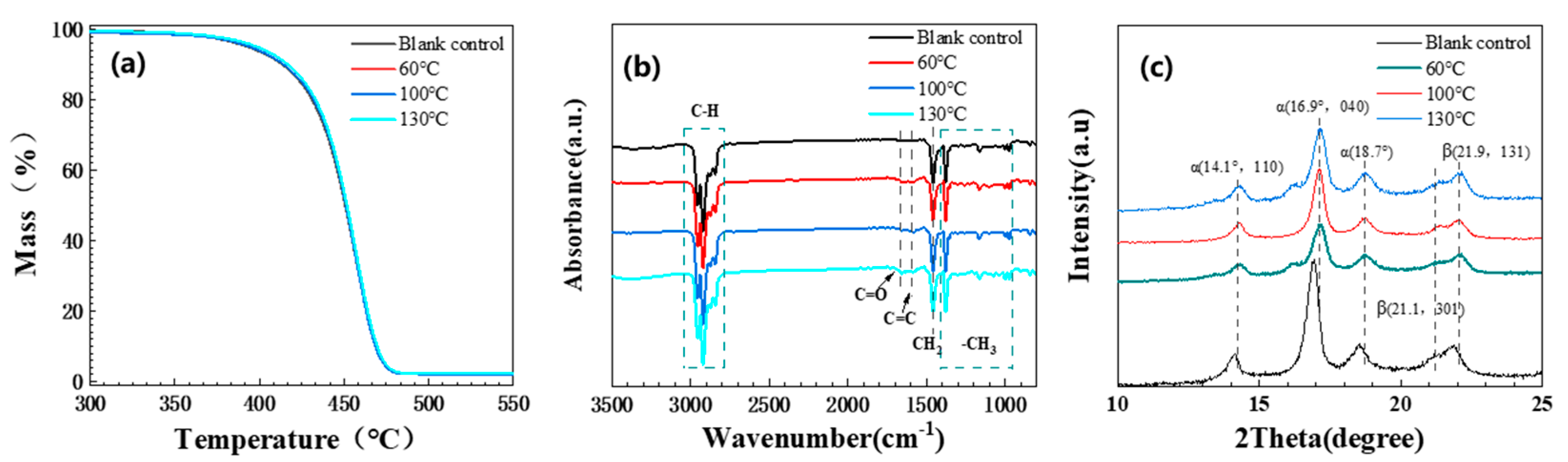

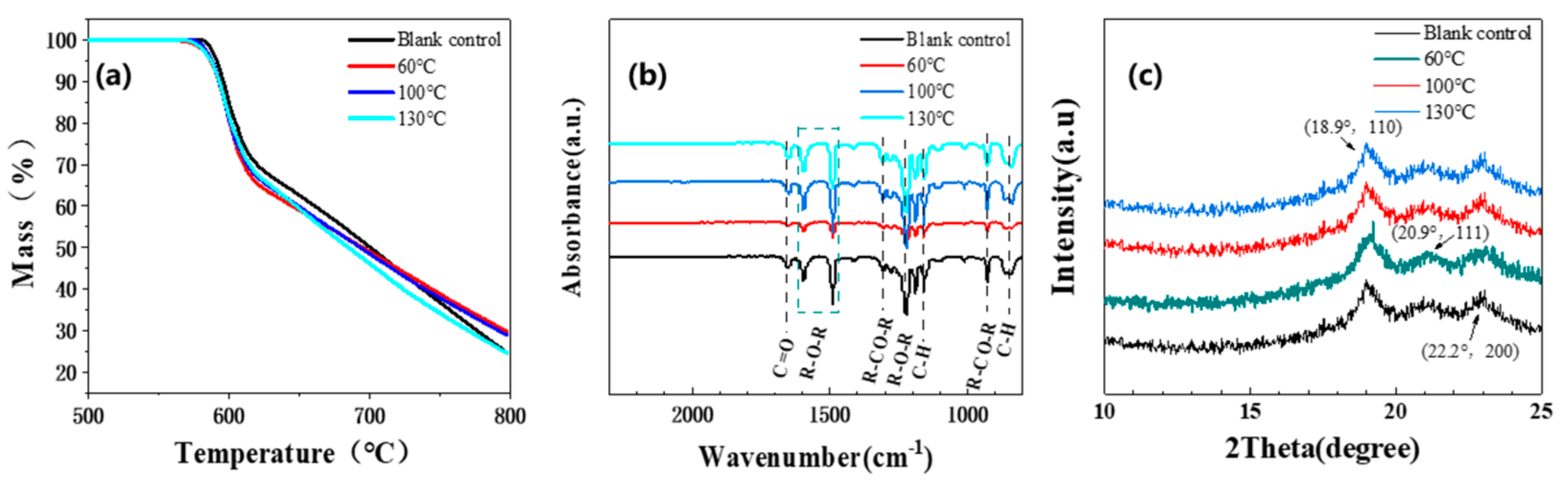

3.2.4. Molten Crystallization Condition

3.2.5. Other Performance Changes

3.2.6. Aging Mechanism Analysis

3.3. Fluorinated Ethylene Propylene Copolymer (FEP) Corrosion Resistance at High Temperature and Pressure

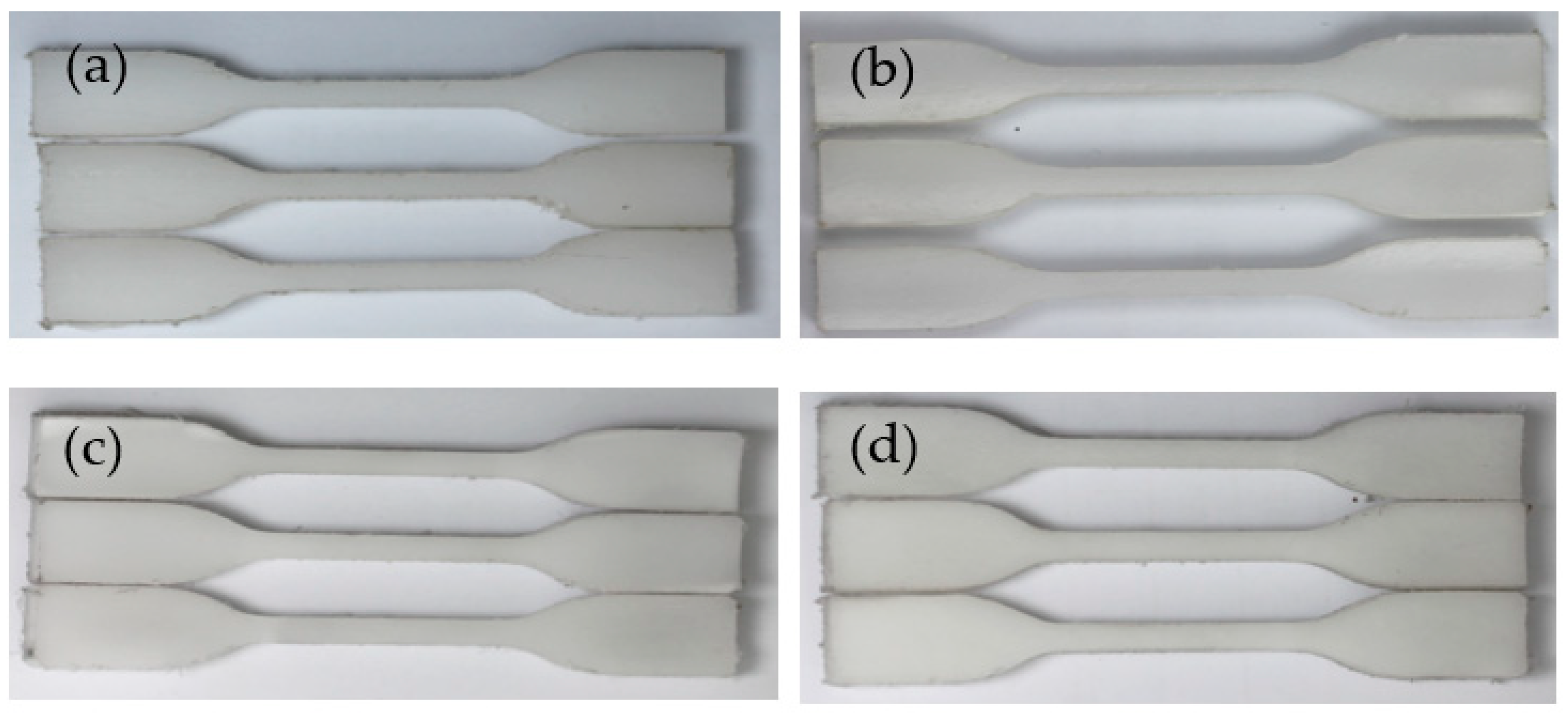

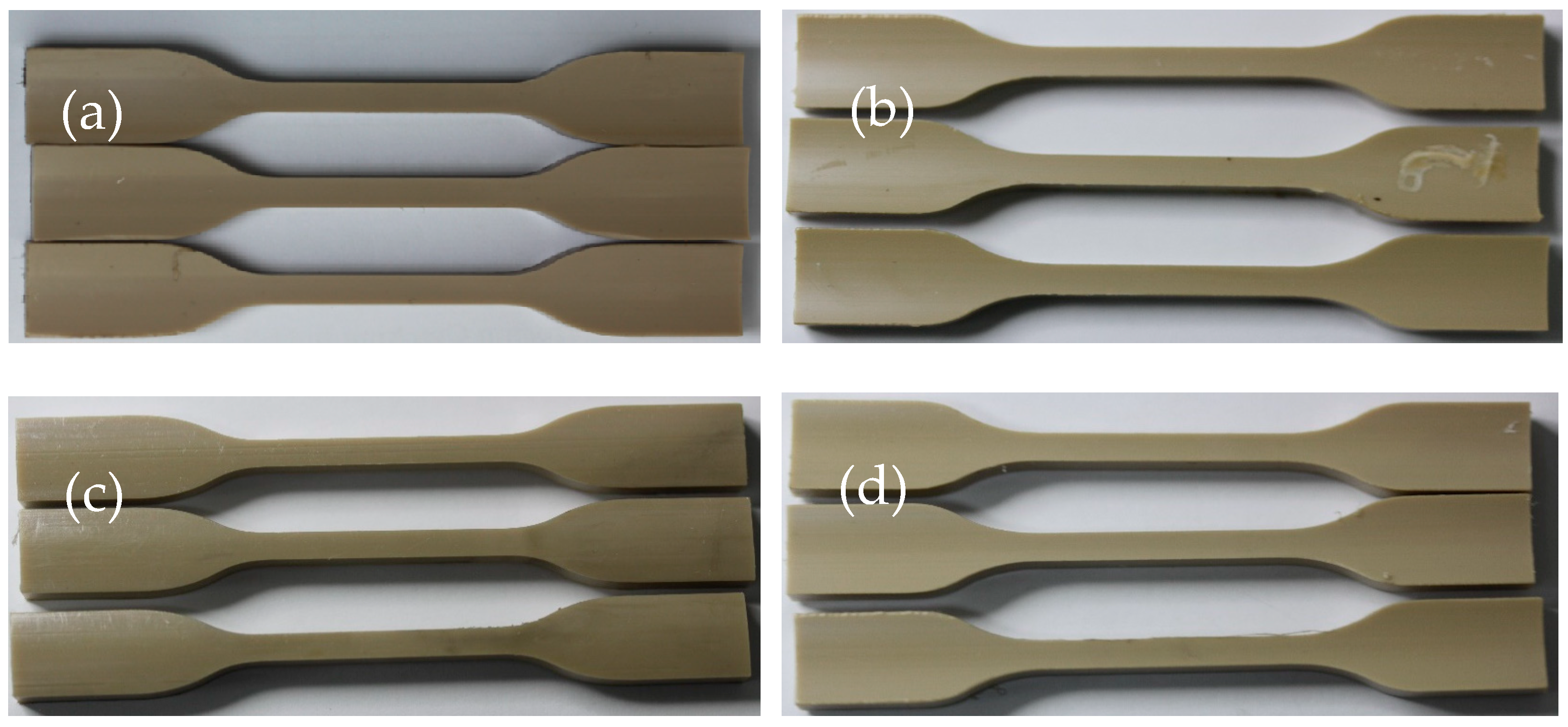

3.3.1. Morphology Change

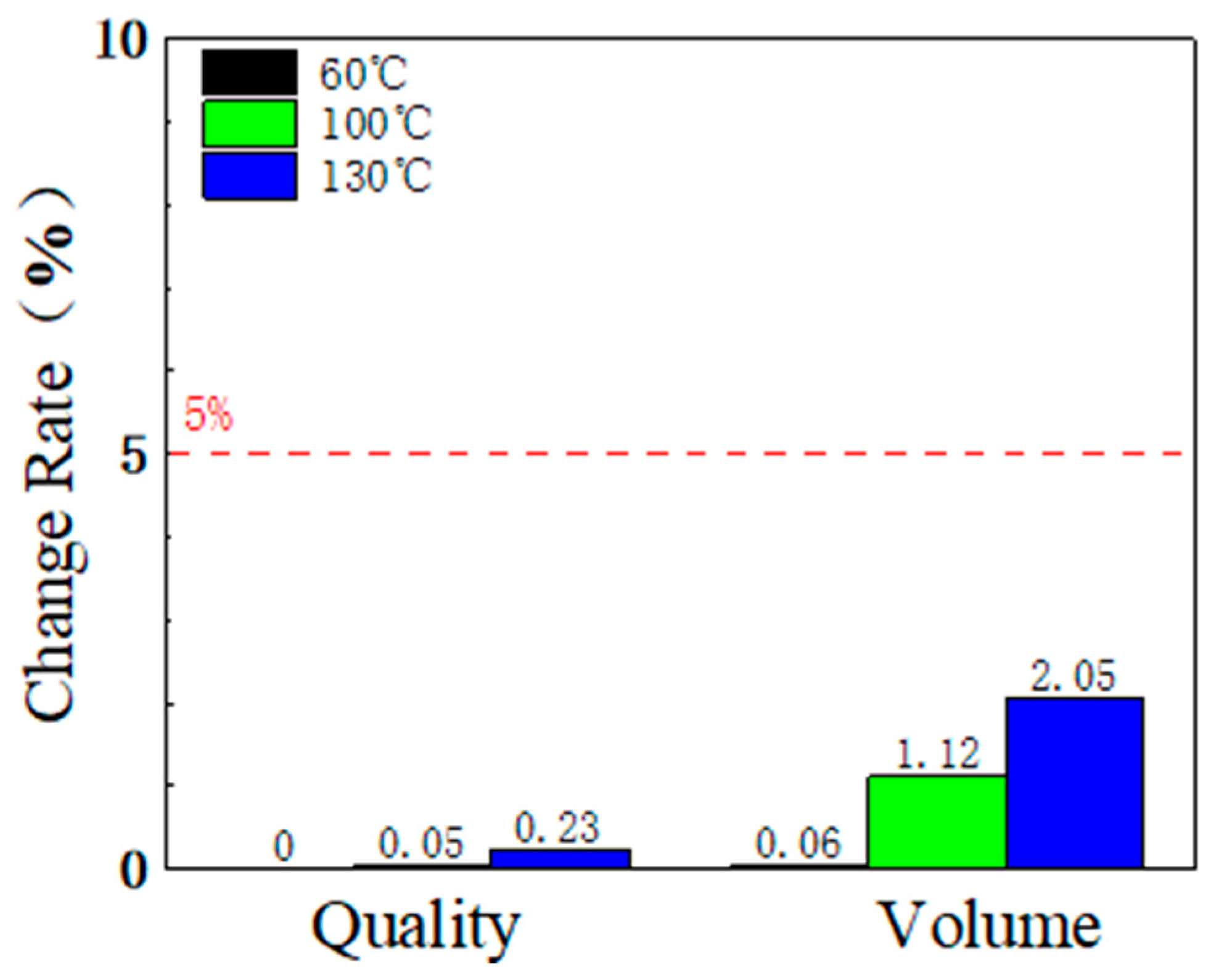

3.3.2. Mass and Volume Change

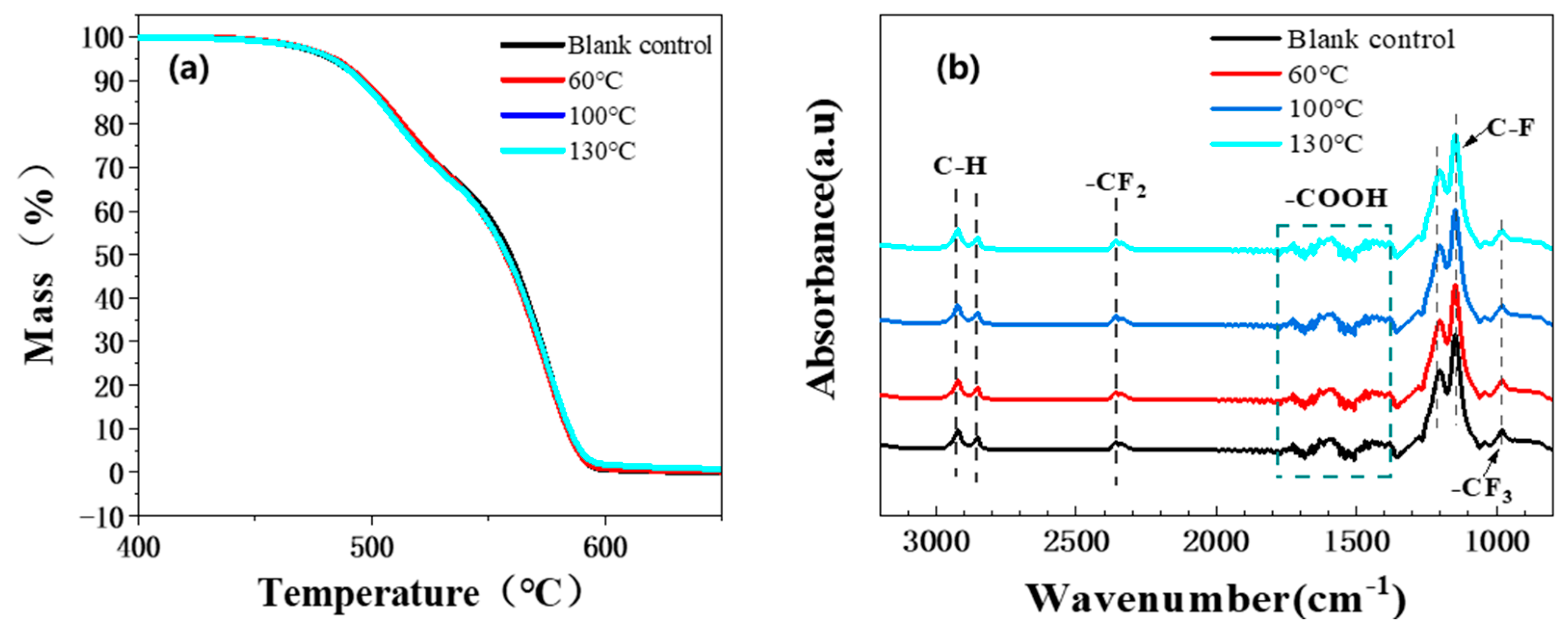

3.3.3. Mechanics and Change of Softening Temperature of Vicat

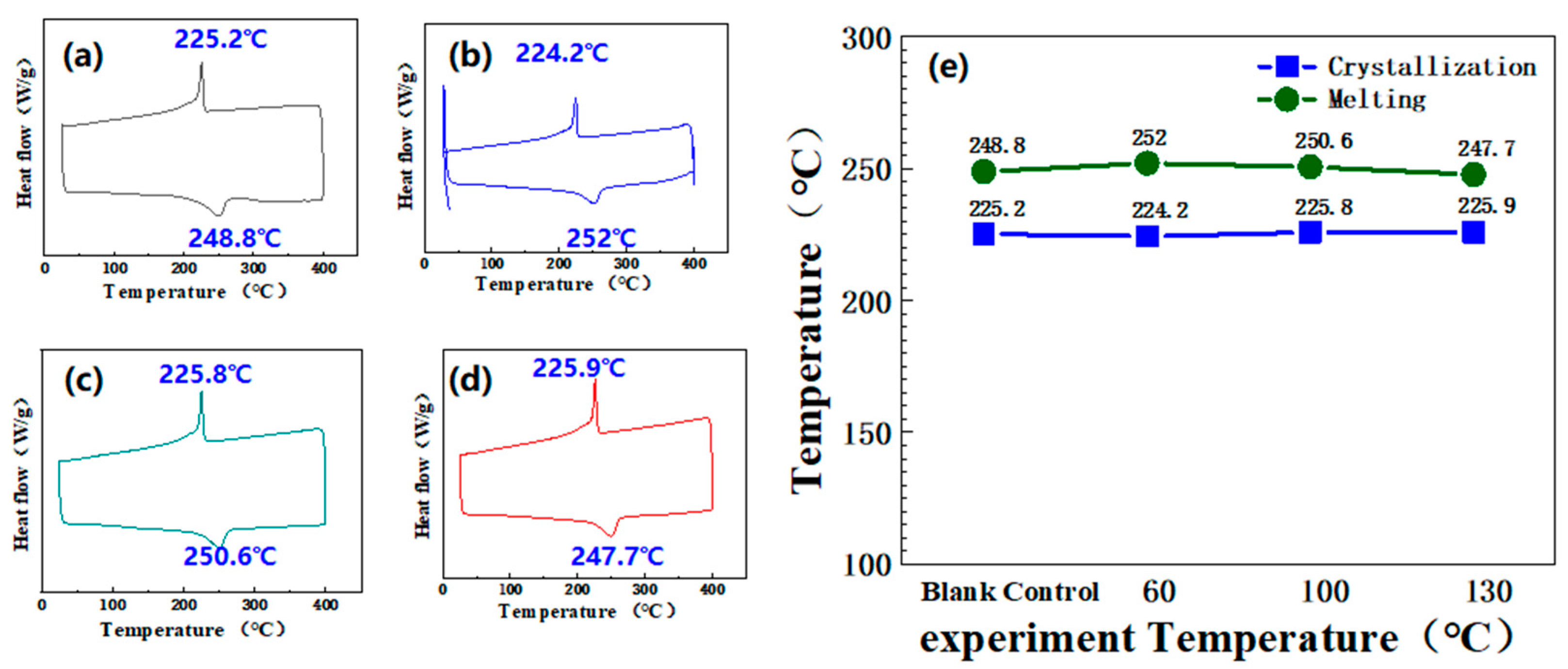

3.3.4. Molten Crystallization Condition

3.3.5. Other Performance Changes

3.4. Polyether Ether Ketone (PEEK) High Temperature and High Pressure

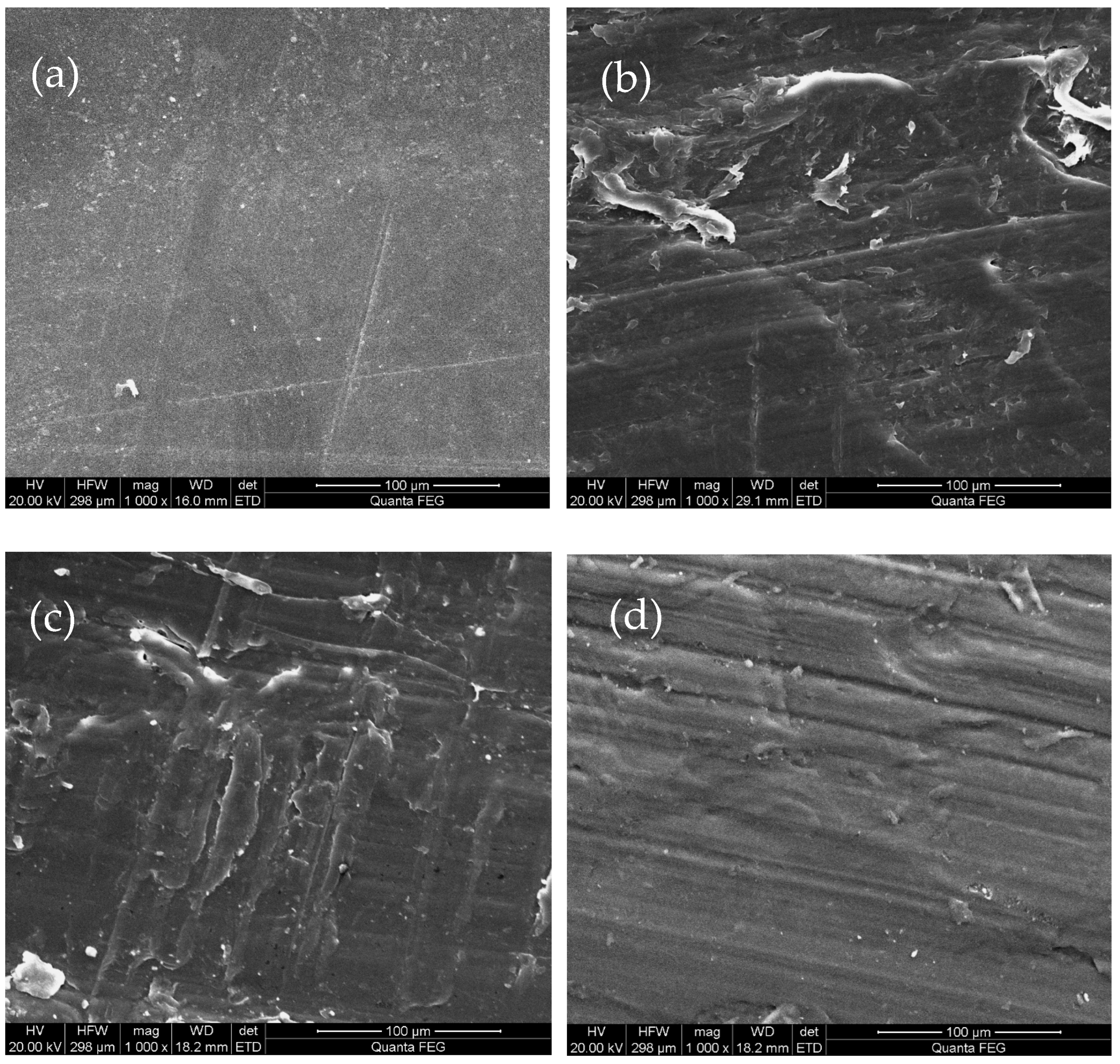

3.4.1. Morphology Change

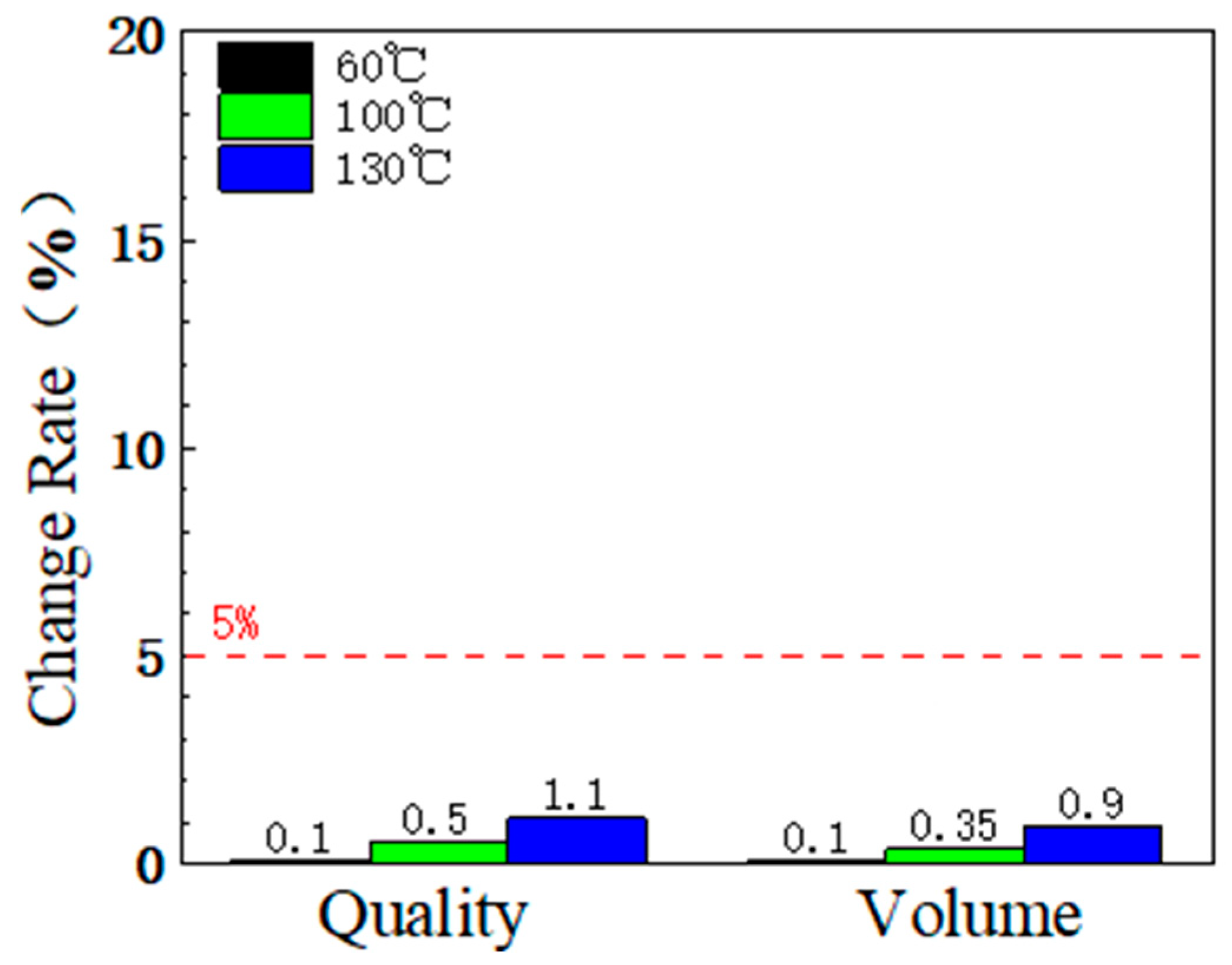

3.4.2. Mass and Volume Change

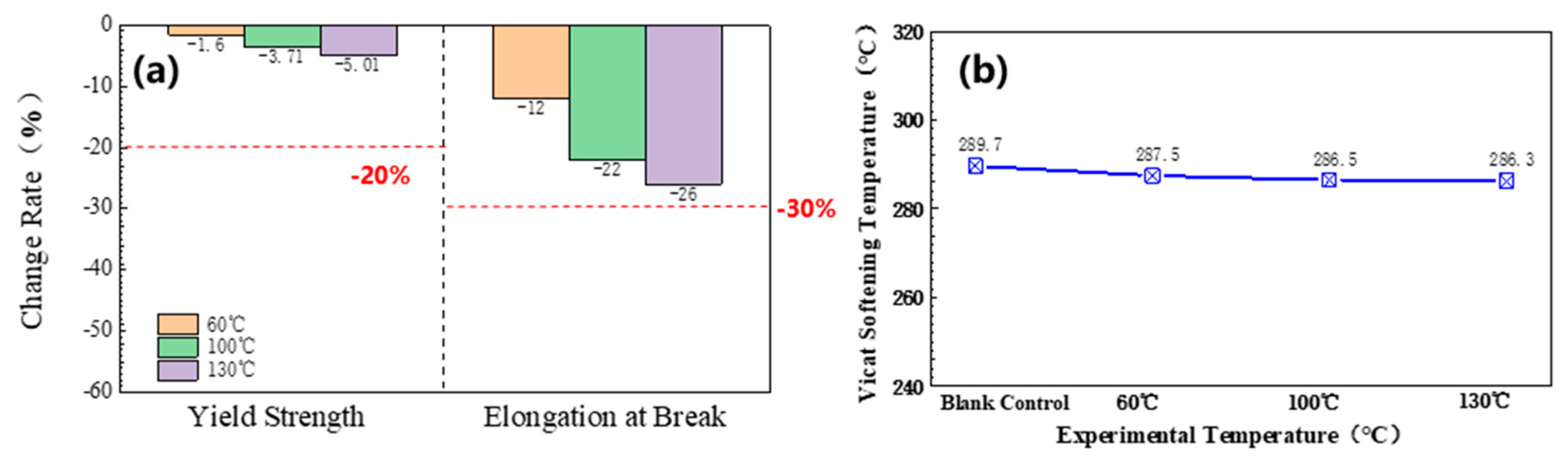

3.4.3. Mechanics and Change of Softening Temperature of Vicat

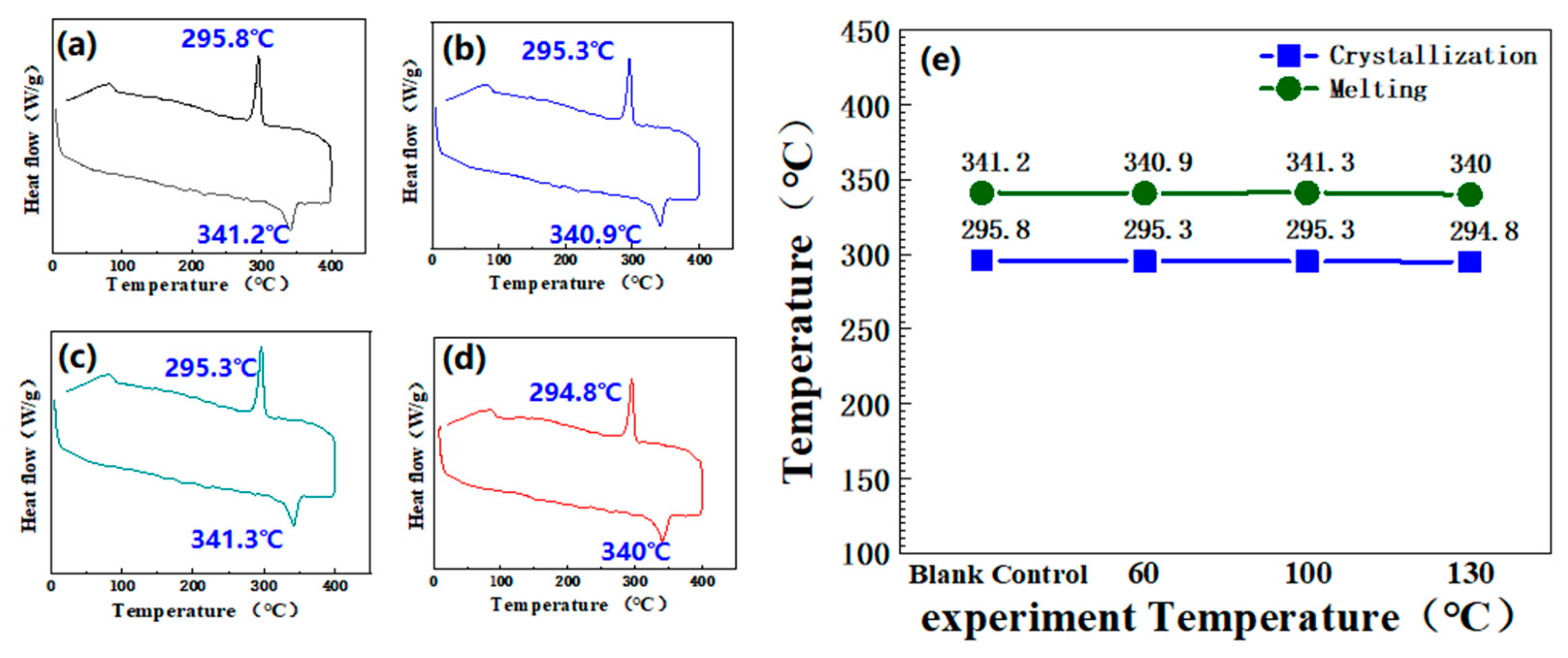

3.4.4. Molten Crystallization Condition

3.4.5. Other Performance Changes

3.4.6. Aging Mechanism Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yusuf, M.; Ibrahim, H. A comprehensive review on recent trends in carbon capture, utilization, and storage techniques. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Wang, F.; Ma, D.; Gao, M.; Zhang, Y. Progress and prospect of carbon dioxide capture, utilization and storage in CNPC oilfields. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2023, 50, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, H.; Littlefield, A.A.; Menefee, M.; Kinzer, A.; Hull, T.; Sovacool, B.K.; Bazilian, M.D.; Kim, J.; Griffiths, S. Carbon capture utilization and storage in review: Sociotechnical implications for a carbon reliant world. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 177, 113215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Teng, F.; McLellan, B.C. A critical review on deployment planning and risk analysis of carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) toward carbon neutrality. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, D.; Saravanan, P.; Nagarajan, L.; Byun, H.-S. An overview of technologies for Capturing, Storing, and utilizing carbon Dioxide: Technology Readiness, large–Scale Demonstration, and cost. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 491, 151998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, X.; Qiu, B.; Xu, N. Integration of carbon emission reduction policies and technologies: Research progress on carbon capture, utilization and storage technologies. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 343, 127153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S.; Liu, A.; Hovington, P. Emerging technologies in post–Combustion carbon dioxide capture & removal. Catal. Today 2023, 423, 114286. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H.; Zeng, S.; Wu, D. Development Status and Prospects of CCUS Technology Under the Background of Carbon Peak and Neutrality. Shandong Chem. Ind. 2023, 52, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, B.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y. Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS) Technology Helps to the Realization of Carbon Neutralization. Ind. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 47 (Suppl. S1), 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, J.; Qian, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z. Review of research progress and stability studies of amine–Based biphasic absorbents for CO2 capture. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2024, 134, 28–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Zhang, W.; Han, L.; Zhang, X.; He, L. Mass transfer properties of structured wire mesh packing. J. Tianjin Univ. 2007, 40, 916–920. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, S.; Liang, P.; Ye, Z.; Li, Y. An Accelerated–Based Evaluation Method for Corrosion Lifetime of Materials Considering High–Temperature Oxidation Corrosion. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wang, H.; Yin, H.; Liu, Q.; Tang, Z. Effect of Temperature and Impurity Content to Control Corrosion of 316 Stainless Steel in Molten KCl–MgCl2 Salt. Materials 2023, 16, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niedermeier, K.; Lux, M.; Purwitasari, A.; Weisenburger, A.; Daubner, M.; Müller-Trefzer, F.; Wetzel, T. Design of the LIMELIGHT Test Rig for Component Testing for High–Temperature Thermal Energy Storage with Liquid Metals. Processes 2023, 11, 2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivolta, B.; Gerosa, R.; Panzeri, D.; Nazim, A. Optimization of the Mechanical and Corrosion Resistance of Alloy 625 through Aging Treatments. Crystals 2024, 14, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagavatula, K.G.; Leena, S.; Murugasamy, K.; Nanoth, R.; Narayanan, S.; Pegoretti, A.; Karingamanna, J. Epoxy nanocomposites with dual filler system: Improving surface protection against wear and thermocyclic corrosion. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 55, 105477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Chen, Y.; Cai, M.; Li, J.; Lu, Q.; Hou, D. Characterization and Analysis of Corrosion Resistance of Rubber Materials for Downhole Tools in a High–Stress Environment with Coupled H2S–CO2. Materials 2024, 17, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, İ.; Tuna, S.; Kurtlu, M.A. Evaluation of the use and performance of natural filler based polypropylene/leonardite composites. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 480, 144105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Gu, Y.; Zhao, R.; Huang, Y.; Fang, M.; Yu, X.; Dong, W.; Wang, T.; Wang, Q. Research on Mass Transfer Properties of modified plastic fillers for Carbon capture absorber. Proc. CSEE 2023, 43, 4688–4697. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, D.; Yang, X. Research on the formula and performance of CPVC filler. Polyvinyl Chloride 2023, 51, 10–12+19. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, C.; Huang, J.; Li, C.; Wang, X. Study on Properties of Graphene and Polyphenyl Ester Co–Filled FEP. Mod. Plast. Process. Appl. 2020, 32, 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Rocha, J.D.; Zhou, J.S.; Meyer, H.S.; Bikson, B.; Ding, Y. Post-combustion CO2 capture using super-hydrophobic, polyether ether ketone, hollow fiber membrane contactors. J. Membr. Sci. 2013, 430, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 1040; Mechanical Properties of Plastics—Determination of Tensile Properties. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Zween, A.F.; Shakor, Z.M.; Sherhan, B.Y. Coke Decomposition Kinetic Model of Spent Hydrodesulfurization catalysts. J. Appl. Sci. Nanotechnol. 2024, 4, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khader, E.H.; Mohammed, T.J.; Albayati, T.M.; Zendehboudi, S. Preparation of Eco-Friendly Nanocatalyst Calcium Oxide (CaO) for Oily Wastewater Treatment by Advanced Oxidation Process. J. Appl. Sci. Nanotechnol. 2025, 5, 1. [Google Scholar]

| Ingredients |

|---|

| Chlorinated polyvinyl chloride (PVC-C) |

| Polypropylene (PP) |

| Fluorinated ethylene propylene copolymer (FEP) |

| Polyether ether ketone (PEEK) |

| Material | T, °C | CO2 | O2, V% | SO2, mg/m3 | NO2, mg/m3 | Cl− | Flow Rate, m/s | Period, d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVC-C PP EFP PEEK | 60 | 100% | 5% | 100 | 200 | 1000 | 1 | 30 |

| 100 | 100% | – | 100 | 200 | 1000 | 1 | 30 | |

| 130 | 100% | – | 100 | 200 | 1000 | 1 | 30 |

| Name of Instrument | Model Number |

|---|---|

| Fourier transform infrared analyzer | TENSOR Type II |

| Cold field emission scanning electron microscopy | SU8010 |

| High temperature and high pressure reactor | 5L |

| Universal Material Testing Machine | WDL-5kN-II |

| Differential scanning calorimeter | 204 F1 |

| Vicat softening temperature tester | XRW-300E |

| Thermogravimetric analyzer | TA-60 WS |

| Electronic balance | ME 104E/02 |

| Electric thermostatic blast drying oven | DHG-9036A |

| Electronic density balance | JA3003J |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fang, K.; Fan, X.; Chen, J.; Dong, L.; Hu, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Sun, J.; Zheng, X.; Liu, G. Study on the Properties of Plastic Fillers in Carbon Dioxide Capture System Under High Temperature and High Pressure. Coatings 2025, 15, 360. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15030360

Fang K, Fan X, Chen J, Dong L, Hu J, Liu Y, Liu S, Sun J, Zheng X, Liu G. Study on the Properties of Plastic Fillers in Carbon Dioxide Capture System Under High Temperature and High Pressure. Coatings. 2025; 15(3):360. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15030360

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Kun, Xuehua Fan, Jie Chen, Lei Dong, Jiahui Hu, Yiying Liu, Shengyuan Liu, Jianbo Sun, Xiangyu Zheng, and Guojian Liu. 2025. "Study on the Properties of Plastic Fillers in Carbon Dioxide Capture System Under High Temperature and High Pressure" Coatings 15, no. 3: 360. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15030360

APA StyleFang, K., Fan, X., Chen, J., Dong, L., Hu, J., Liu, Y., Liu, S., Sun, J., Zheng, X., & Liu, G. (2025). Study on the Properties of Plastic Fillers in Carbon Dioxide Capture System Under High Temperature and High Pressure. Coatings, 15(3), 360. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15030360