Greater Mouse-Eared Bats (Myotis myotis) Hibernating in the Nietoperek Bat Reserve (Poland) as a Vector of Airborne Culturable Fungi

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

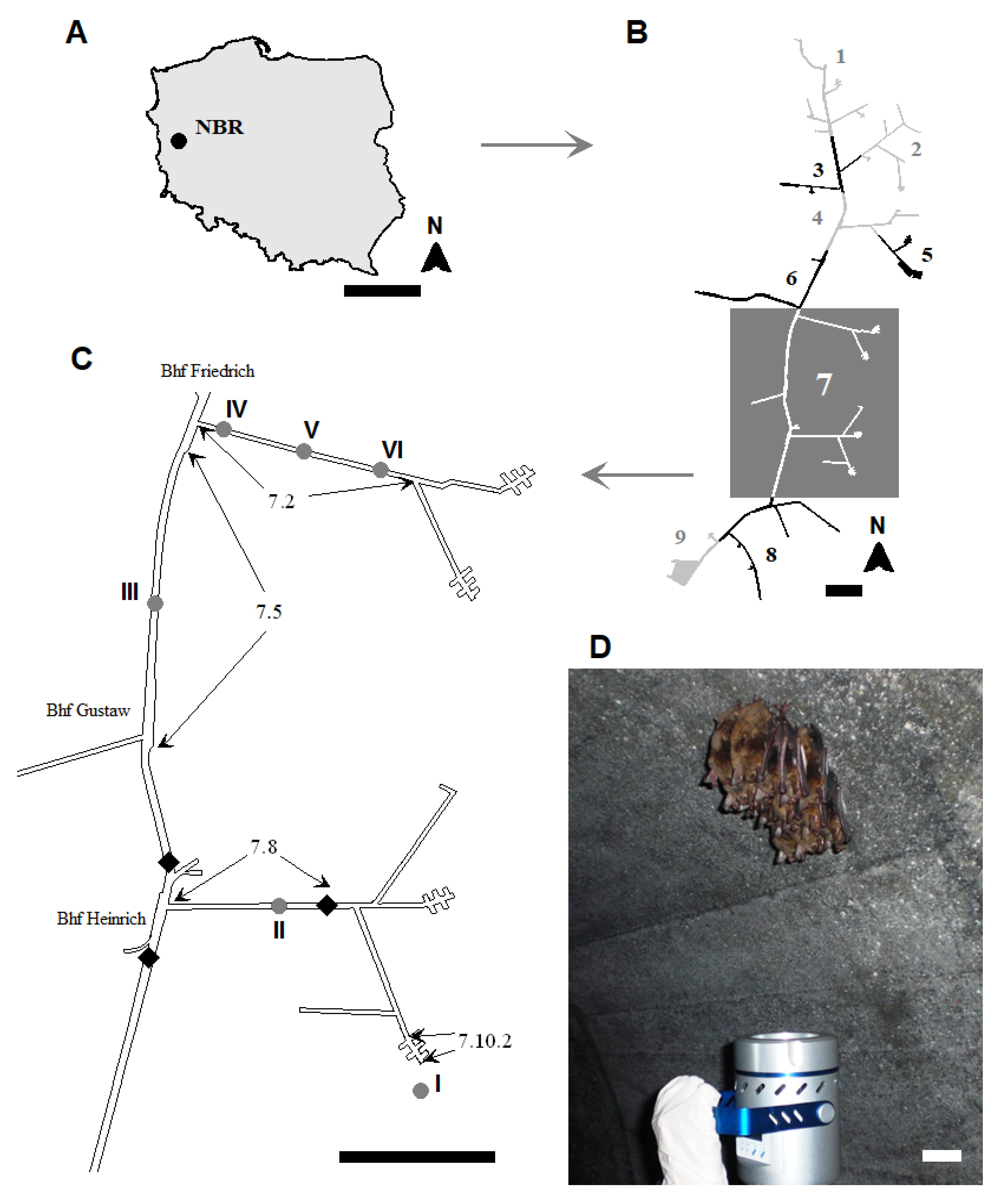

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Aeromycological Study

2.2.1. Sampling Methods

2.2.2. Identification of Airborne Fungi

2.3. Bat Number and Species Composition

2.4. Measurements of Underground Corridors, Temperature, and Relative Humidity

2.5. Data Analyses

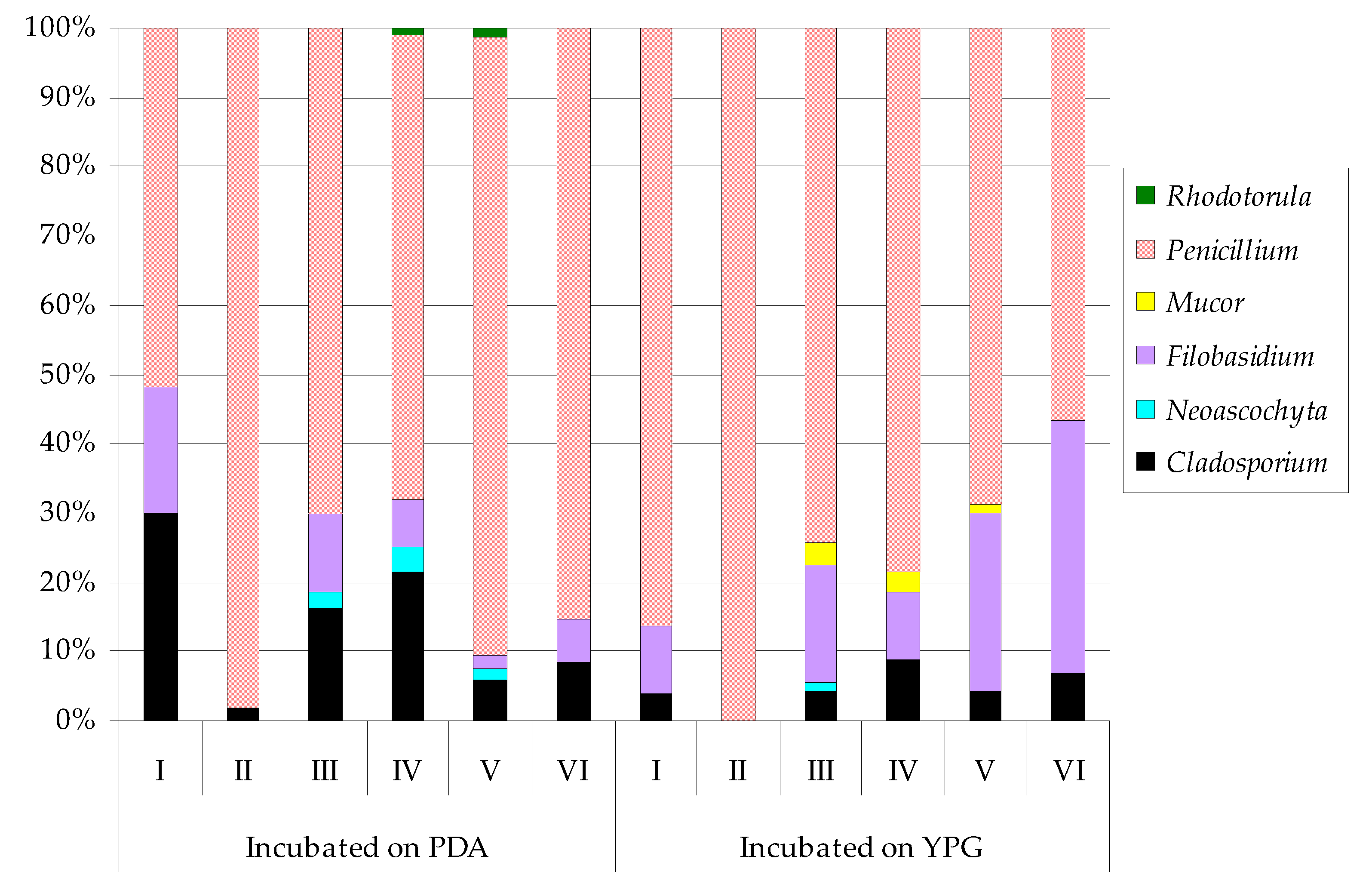

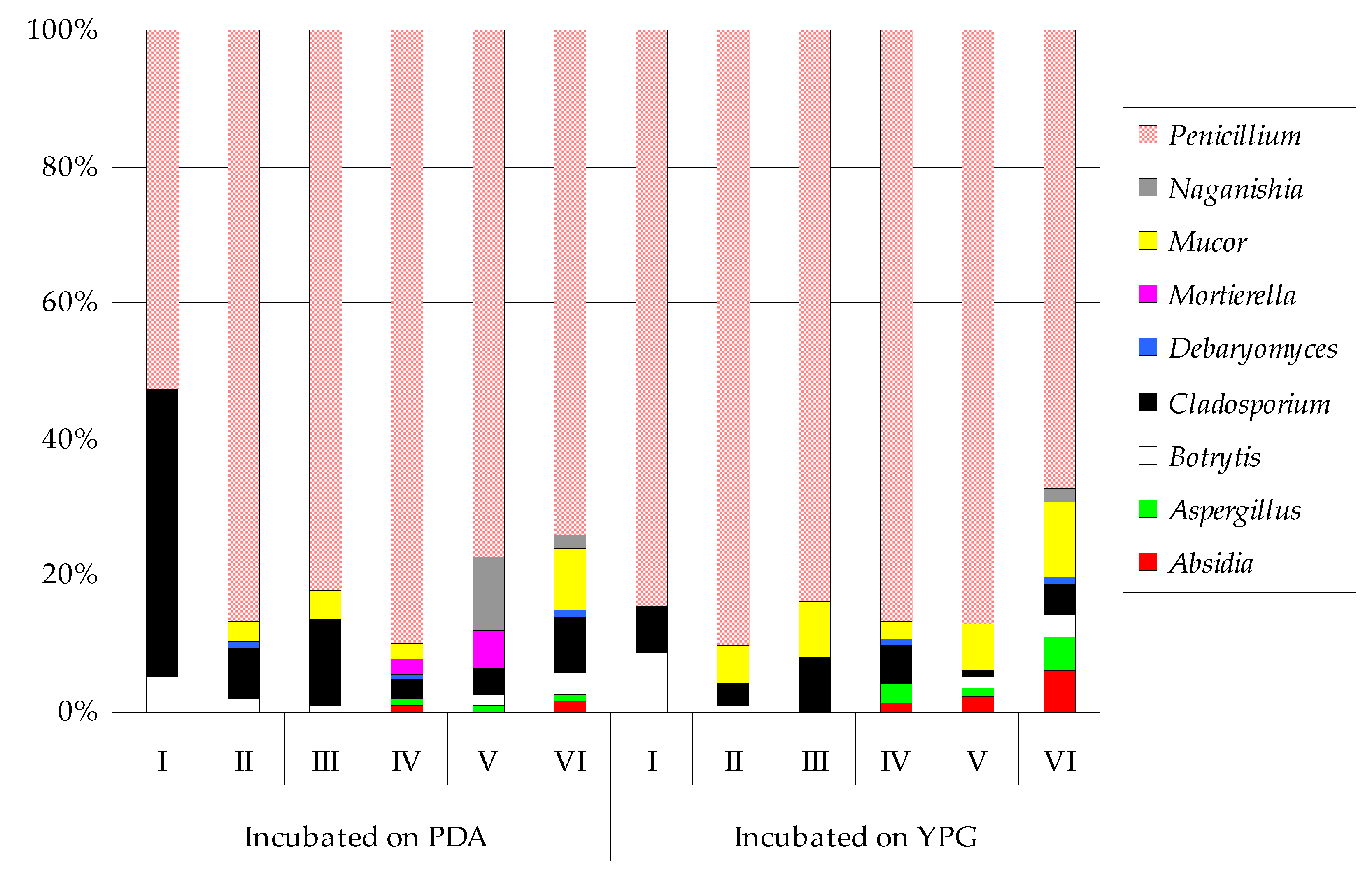

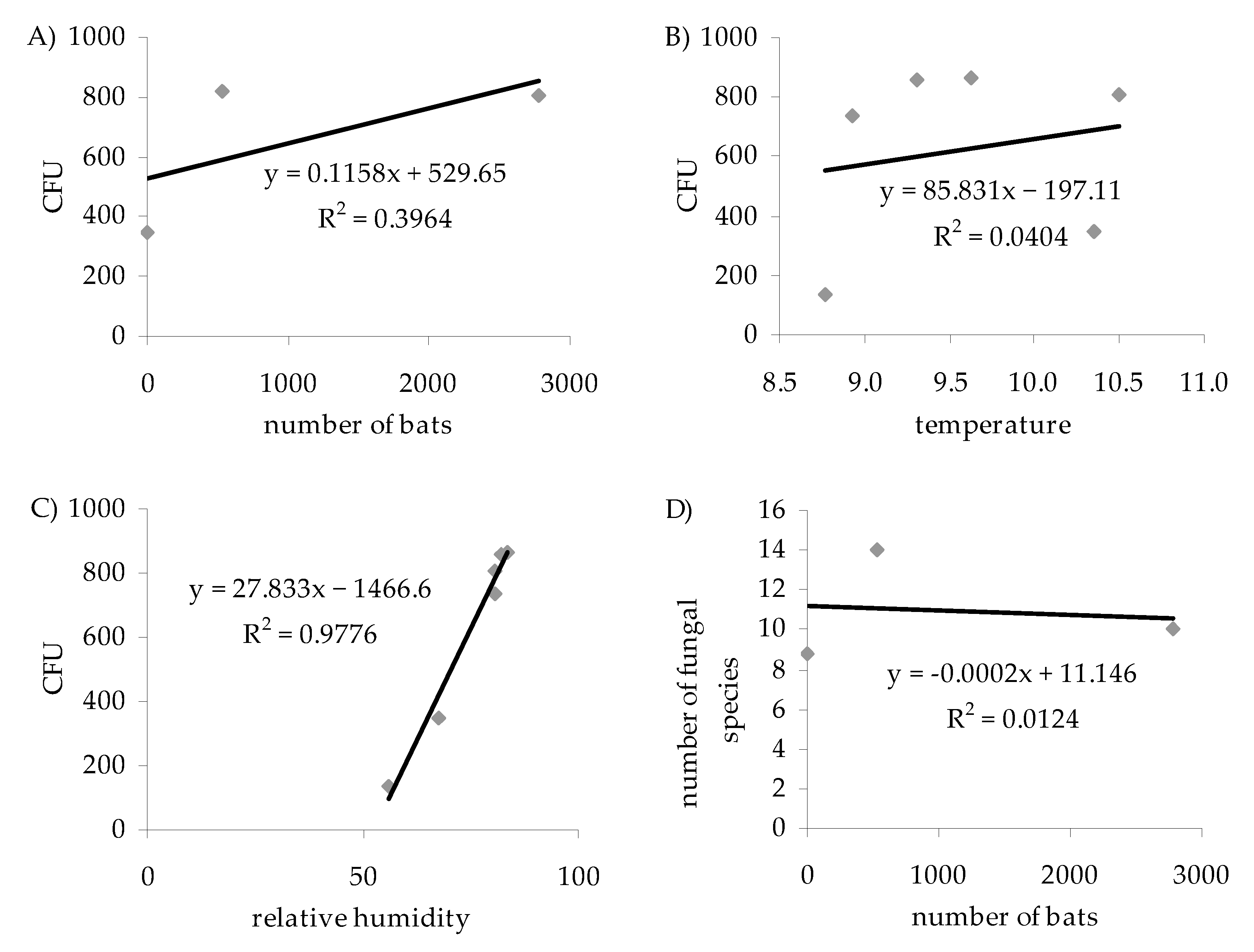

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Physical Conditions in the Nietoperek Bat Reserve

4.2. Fungal Species Composition and the Number of Bats

4.3. Influence of Air Temperature and Humidity on the Number and Species Composition of Airborne Culturable Fungi

4.4. Influence of the Culture Medium and Incubation Temperature on Fungal Isolation

4.5. Mycological Air Quality and Biological Safety Assessment for Human and Animal Health

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Fungi | Isolate | GenBank Accession No. | Identity with Sequence from GenBank | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Query Cover, % | Identity, % | Accession | Isolate | |||

| Absidia glauca | UWR_114 | MK690542.1 | 99% | 94.71% | KY465754.1 | UWR_100 |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | UWR_115 | MK690543.1 | 100% | 99.72% | MN258567.1 | R29 |

| Aspergillus tubingensis | UWR_116 | MK690544.1 | 100% | 100.00% | KU243047.1 | HRb |

| Botrytis cinerea | UWR_117 | MK690545.1 | 100% | 100.00% | MG744435.1 | MGGM002 |

| Cladosporium cladosporioides | UWR_118 | MK690546.1 | 99% | 99.80% | JN986781.1 | DHMJ29 |

| Cladosporium herbarum | UWR_119 | MK690547.1 | 100% | 100.00% | MN486496.1 | YMZZ2 |

| Cladosporium macrocarpum | UWR_120 | MK690548.1 | 100% | 99.60% | KX815295.1 | JS4-25 |

| Debaryomyces hansenii | UWR_121 | MK690549.1 | 100% | 99.83% | MK268125.1 | R97192 |

| Neoascochyta exitialis | UWR_122 | MK690550.1 | 100% | 99.60% | EU167564.1 | CBS 446.82 |

| Filobasidium magnum | UWR_123 | MK690551.1 | 100% | 100.00% | MK226208.1 | D6 |

| Mortierella polycephala | UWR_124 | MK690552.1 | 99% | 99.16% | MH860490.1 | CBS 327.72 |

| Mucor circinelloides | UWR_125 | MK690553.1 | 100% | 100.00% | MK928427.1 | KKP 3008 |

| Mucor flavus | UWR_126 | MK690554.1 | 94% | 92.93% | NR_103633.1 | CBS 234.35 |

| Mucor fragilis | UWR_127 | MK690555.1 | 100% | 99.66% | MK910073.1 | BC3 |

| Naganishia diffluens | UWR_128 | MK690556.1 | 100% | 100.00% | KY104328.1 | CBS:160 |

| Penicillium bialowiezense | UWR_129 | MK690557.1 | 100% | 100.00% | MH854996.1 | CBS 227.28 |

| Penicillium brevicompactum | UWR_130 | MK690558.1 | 100% | 100.00% | MH865309.1 | CBS 129415 |

| Penicillium brevistipitatum | UWR_131 | MK690559.1 | 99% | 99.62% | MG490883.1 | KAS7539 |

| Penicillium cavernicola | UWR_132 | MK690560.1 | 100% | 100.00% | MN413150.1 | CBS 109557 |

| Penicillium chrysogenum | UWR_133 | MK690561.1 | 99% | 100.00% | KM357336.1 | no data |

| Penicillium commune | UWR_134 | MK690562.1 | 99% | 100.00% | MK660354.1 | QP3 |

| Penicillium camemberti | UWR_135 | MK690563.1 | 100% | 99.62% | KY218668.1 | IF2SW-F1 |

| Penicillium concentricum | UWR_136 | MK690564.1 | 100% | 100.00% | DQ339561.1 | NRRL 2034 |

| Penicillium crustosum | UWR_137 | MK690565.1 | 100% | 91.00% | KF938379.1 | 04SK002 |

| Penicillium echinulatum | UWR_138 | MK690566.1 | 100% | 100.00% | KT876710.1 | A4-2 |

| Penicillium expansum | UWR_139 | MK690567.1 | 100% | 100.00% | MK201595.1 | SE1 |

| Penicillium freii | UWR_140 | MK690568.1 | 99% | 99.44% | JN942696.1 | CBS 794.95 |

| Penicillium lilacinoechinulatum | UWR_141 | MK690569.1 | 100% | 99.63% | KC773837.1 | CBS 454.93 |

| Penicillium robsamsonii | UWR_142 | MK690570.1 | 100% | 99.63% | NR_144866.1 | CBS 140573 |

| Penicillium solitum | UWR_143 | MK690571.1 | 100% | 100.00% | MK660356.1 | QPA4 |

| Penicillium viridicatum | UWR_144 | MK690572.1 | 100% | 100.00% | MH856411.1 | CBS 390.48 |

| Rhodotorula mucilaginosa | UWR_145 | MK690573.1 | 100% | 100.00% | MK263185.1 | IMUFRJ 52392 |

| Fungi | Incubated on PDA | Incubated on YPG | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | |||||||||||||

| Cladosporium macrocarpum | 23 | ab 2 | 5 | c | 109 | ab | 126 | ab | 38 | b | 46 | b | 4 | b 2 | ― | 34 | cde | 80 | bc | 40 | d | 55 | b | |

| Neoascochyta exitialis | ― 1 | ― | 17 | d | 21 | d | 9 | b | ― | ― 1 | ― | 2 | e | ― | ― | ― | ||||||||

| Filobasidium magnum | 14 | bc | ― | 76 | bc | 39 | cd | 13 | b | 34 | b | 10 | b | ― | 133 | b | 91 | bc | 253 | b | 301 | a | ||

| Mucor circinelloides | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | 21 | de | ― | ― | ― | |||||||||||

| Mucor fragilis | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | 4 | e | 25 | c | 14 | d | ||||||||||

| Penicillium chrysogenum | 31 | a | 69 | b | 228 | a | 166 | a | 201 | a | 213 | a | 35 | a | 221 | a | 307 | a | 506 | a | 442 | a | 376 | a |

| Penicillium concentricum | ― | 154 | a | 96 | bc | ― | 52 | b | ― | ― | 87 | b | 76 | bcd | ― | 29 | d | ― | ||||||

| Penicillium crustosum | ― | 26 | bc | 87 | bc | 149 | a | 306 | a | 248 | a | ― | 6 | c | 92 | bc | 46 | bc | 165 | c | 90 | b | ||

| Penicillium freii | 9 | c | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | 53 | a | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ||||||||||

| Penicillium solitum | ― | ― | 60 | bc | 78 | bc | 11 | b | ― | ― | 8 | c | 105 | b | 167 | b | 38 | d | ― | |||||

| Rhodotorula mucilaginosa | ― | ― | ― | 2 | cd | 6 | b | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ||||||||||

| Shannon Index | 0.5594 | 0.4204 | 0.7637 | 0.7074 | 0.5833 | 0.4812 | 0.4612 | 0.3378 | 0.5290 | 0.5773 | 0.6305 | 0.4989 | ||||||||||||

| Fungi | Incubated on PDA | Incubated on YPG | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | |||||||||||||

| Absidia glauca | ― 1 | ― | ― | 7 | ef | ― | 11 | d | ― 1 | ― | ― | 15 | e | 24 | cd | 59 | bcd | |||||||

| Aspergillus fumigatus | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | 36 | e | 9 | d | 44 | bcdef | |||||||||

| Aspergillus tubingensis | ― | ― | ― | 6 | ef | 7 | f | 4 | d | ― | ― | ― | 2 | e | 7 | d | 3 | ef | ||||||

| Botrytis cinerea | 7 | c 2 | 6 | d | 5 | e | ― | 11 | f | 22 | cd | 21 | b 2 | 3 | b | ― | ― | 18 | cd | 30 | cdef | |||

| Cladosporium cladosporioides | 32 | ab | 24 | bcd | 40 | de | 11 | ef | 27 | ef | 38 | bcd | 12 | b | 5 | b | 44 | bcd | 13 | e | 10 | d | ― | |

| Cladosporium herbarum | 23 | bc | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | 5 | b | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ||||||||||

| Cladosporium macrocarpum | ― | ― | 63 | cde | 9 | ef | ― | 15 | d | ― | 11 | b | 36 | bcd | 55 | de | ― | 43 | bcdef | |||||

| Debaryomyces hansenii | ― | 1 | d | ― | 2 | f | ― | 3 | d | ― | ― | ― | 3 | e | ― | 1 | f | |||||||

| Mortierella polycephala | ― | ― | ― | 15 | ef | 40 | def | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ||||||||||

| Mucor circinelloides | ― | 9 | cd | 34 | de | 18 | def | ― | 59 | bc | ― | 26 | b | ― | 35 | e | 51 | cde | 66 | bc | ||||

| Mucor flavus | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | 78 | bc | ― | ― | 18 | def | ||||||||||

| Mucor fragilis | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | 25 | de | 21 | cdef | ||||||||||

| Naganishia diffluens | ― | ― | ― | ― | 73 | cde | 12 | d | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | 17 | def | |||||||||

| Penicillium bialowiezense | ― | 40 | ab | 106 | bc | 110 | b | 164 | a | 62 | bc | ― | 22 | b | 80 | bc | ― | 114 | bc | ― | ||||

| Penicillium brevicompactum | ― | 47 | ab | 137 | b | 59 | cd | 87 | cd | 78 | b | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | |||||||

| Penicillium brevistipitatum | ― | ― | 42 | de | ― | ― | ― | ― | 80 | a | 55 | bcd | 138 | bcd | 245 | a | 41 | bcdef | ||||||

| Penicillium cavernicola | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | 12 | b | ― | 87 | cde | 43 | de | 56 | bcd | ||||||||

| Penicillium chrysogenum | 12 | c | 65 | a | 198 | a | 229 | a | 110 | bc | 184 | a | 2 | b | 121 | a | 219 | a | 284 | a | 165 | b | 145 | a |

| Penicillium commune | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | 3 | b | 12 | d | 21 | e | 72 | cde | 50 | bcde | |||||||

| Penicillium camemberti | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | 8 | b | ― | ― | ― | 7 | ef | ||||||||||

| Penicillium concentricum | ― | 35 | bc | ― | 37 | def | ― | 30 | cd | 8 | b | 4 | b | ― | 179 | bc | ― | 169 | a | |||||

| Penicillium crustosum | ― | 10 | cd | 70 | cd | 83 | bc | 150 | ab | 61 | bc | 171 | a | 31 | b | 179 | a | 85 | de | 48 | cde | 82 | b | |

| Penicillium echinulatum | ― | 21 | bcd | ― | 60 | cd | ― | 43 | bcd | ― | 33 | b | 63 | bcd | 44 | e | 78 | cd | ― | |||||

| Penicillium expansum | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | 21 | cd | 26 | e | 27 | de | ― | |||||||||

| Penicillium freii | 6 | c | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | 4 | b | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ||||||||||

| Penicillium lilacinoechinulatum | 51 | a | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | 19 | b | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ||||||||||

| Penicillium robsamsonii | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | 9 | b | 47 | bcd | ― | 21 | cd | 25 | cdef | ||||||||

| Penicillium solitum | ― | ― | 47 | cde | 29 | def | ― | ― | ― | 2 | b | 53 | bcd | 41 | e | ― | ― | |||||||

| Penicillium viridicatum | ― | 63 | a | 56 | cde | 48 | cde | 30 | ef | 26 | cd | ― | 115 | a | 96 | b | 181 | b | 156 | b | 64 | bcd | ||

| Shannon Index | 0.6661 | 0.9113 | 0.9359 | 0.9393 | 0.8654 | 0.9974 | 0.4806 | 0.9260 | 1.0047 | 1.0232 | 1.0440 | 1.1283 | ||||||||||||

References

- Jones, G.; Jacobs, D.S.; Kunz, T.H.; Willig, M.R.; Racey, P.A. Carpe Noctem: The importance of bats as bioindicators. Endanger. Species Res. 2009, 8, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mildenstein, T.; Tanshi, I.; Racey, P.A. Exploitation of bats for bushmeat and medicine. In Bats in the Anthropocene: Conservation of Bats in a Changing World; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Volume 20, pp. 325–375. [Google Scholar]

- Shetty, S.; Sreepada, K.S.; Bhat, R. Effect of bat guano on the growth of Vigna radiata L. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2013, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Boyles, J.G.; Cryan, P.M.; McCracken, G.F.; Kunz, T.H. Economic importance of bats in agriculture. Science 2011, 332, 41–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilas, R.A. Ecological and economical impact of bats on ecosystem. Int. J. Life Sci. 2016, 4, 432–440. [Google Scholar]

- Berková, H.; Pokorný, M.; Zukal, J. Selection of buildings as maternity roosts by greater mouse-eared bats (Myotis myotis). J. Mammal. 2014, 95, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bagstad, K.J.; Wiederholt, R. Tourism Values for Mexican Free-Tailed Bat Viewing. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2013, 18, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennisi, L.A.; Holland, S.M.; Stein, T.V. Achieving bat conservation through tourism. J. Ecotourism 2004, 3, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, G.M.; Bravo, A.V.; Espino, A.; Lindsley, M.D.; Gutierrez, R.E.; Rodriguez, I.; Corella, A.; Carrillo, F.; McNeil, M.M.; Warnock, D.W.; et al. Histoplasmosis associated with exploring a bat-inhabited cave in Costa Rica, 1998–1999. Am. J. Trop Med. Hyg. 2004, 70, 438–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, A.O.B.; Bezerra, J.D.P.; Oliveira, T.G.L.; Barbier, E.; Bernard, E.; Machado, A.R.; Souza-Motta, C.M. Living in the dark: Bat caves as hotspots of fungal diversity. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbáčová, K.; Maliničová, L.; Kisková, J.; Maslišová, V.; Uhrin, M.; Pristaš, P. The faecal microbiome of building-dwelling insectivorous bats (Myotis myotis and Rhinolophus hipposideros) also contains antibiotic-resistant bacterial representatives. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 2333–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollentze, N.; Streicker, D.G. Viral zoonotic risk is homogenous among taxonomic orders of mammalian and avian reservoir hosts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 9423–9430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mallapaty, S. Meet the scientists investigating the origins of the COVID pandemic. Nature 2020, 588, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretzschmar, F.; Heinz, B. Social behaviour of a large population of Pipistrellus pipistrellus (Schreber, 1774) (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) and some other bat species in the mining-system of a limestone quarry near Heidelberg (South West Germany). Myotis Int. J. Bat Res. 1995, 32–33, 221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Kokurewicz, T.; Ogórek, R.; Pusz, W.; Matkowski, K. Bats increase the number of cultivable airborne fungi in the “Nietoperek” bat reserve in Western Poland. Microb. Ecol. 2016, 72, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ogórek, R.; Guz-Regner, K.; Kokurewicz, T.; Baraniok, E.; Kozak, B. Airborne bacteria cultivated from underground hibernation sites in the Nietoperek bat reserve (Poland). J. Caves Karst Stud. 2018, 80, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C. Bats are a key source of human viruses—But they’re not special. Nature 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokurewicz, T. Sex and age-related habitat selection and mass dynamics of Daubenton’s bats Myotis daubentonii (Kuhl, 1817) hibernating in natural conditions. Acta Chiropterol. 2004, 6, 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogórek, R.; Lejman, A.; Matkowski, K. The fungi isolated from the Niedźwiedzia Cave in Kletno (Lower Silesia, Poland). Int. J. Speleol. 2013, 42, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jurado, V.; Laiz, L.; Rodriguez-Nava, V.; Boiron, P.; Hermosin, H.; Sanchez-Moral, S.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. Pathogenic and opportunistic microorganisms in caves. Int. J. Speleol. 2010, 39, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, L.J.; Miller, A.N.; McCleery, R.A.; McClanahan, R.; Kath, J.A.; Lueschow, S.; Porras-Alfaro, A. Psychrophilic and psychrotolerant fungi on bats and the presence of Geomyces spp. on bat wings prior to the arrival of white nose syndrome. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 5465–5471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khizhnyak, S.V.; Tausheva, I.V.; Berezikova, A.A.; Nesterenko, E.V.; Rogozin, D.Y. Psychrophilic and Psychrotolerant Heterotrophic Microorganisms of Middle Siberian Karst Cavities. Russ. J. Ecol. 2003, 34, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderwolf, K.J.; Malloch, D.; McAlpine, D.F.; Forbes, G.J. A world review of fungi, yeasts, and slime molds in caves. Int. J. Speleol. 2013, 42, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogórek, R.; Pusz, W.; Zagożdżon, P.P.; Kozak, B.; Bujak, H. Abundance and diversity of psychrotolerant cultivable mycobiota in winter of a former aluminous shale mine. Geomicrobiol. J. 2017, 34, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verant, M.L.; Boyles, J.G.; Waldrep, W., Jr.; Wibbelt, G.; Blehert, D.S. Temperature-dependent growth of Geomyces destructans, the fungus that causes bat white-nose syndrome. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorch, J.M.; Muller, L.K.; Russell, R.E.; O’Connor, M.; Lindner, D.L.; Blehert, D.S. Distribution and environmental persistence of the causative agent of White-Nose Syndrome, Geomyces destructans, in bat hibernacula of the Eastern United States. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zukal, J.; Bandouchova, H.; Brichta, J.; Cmokova, A.; Jaron, K.S.; Kolarik, M.; Kovacova, V.; Kubátová, A.; Nováková, A.; Orlov, O.; et al. White-nose syndrome without borders: Pseudogymnoascus destructans infection tolerated in Europe and Palearctic Asia but not in North America. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veselská, T.K.; Homutová, K.; García, F.P.; Kubátová, A.; Martínková, N.; Pikula, J.; Kolařík, M. Comparative eco-physiology revealed extensive enzymatic curtailment, lipases production and strong conidial resilience of the bat pathogenic fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulson, T.L.; Lavoie, K.H. The trophic basis of subsurface ecosystems. In Ecosystems of the World: Subterranean Ecosystems; Wilkens, H., Culver, D.C., Humphreys, W.F., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 231–249. [Google Scholar]

- Ogórek, R.; Dyląg, M.; Kozak, B.; Višňovská, Z.; Tancinová, D.; Lejman, A. Fungi isolated and quantified from bat guano and air in Harmanecka’ and Driny Caves (Slovakia). J. Caves Karst Stud. 2016, 78, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunarathna, S.C.; Dong, Y.; Karasaki, S.; Tibpromma, S.; Hyde, K.D.; Lumyong, S.; Xu, J.C.; Sheng, J.; Mortimer, P.E. Discovery of novel fungal species and pathogens on bat carcasses in a cave in Yunnan Province, China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 1554–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, J.; Brandl, H. Bioaerosols in indoor environments—A review with special reference to residential and occupational locations. Open Environ. Biol. Monit. J. 2011, 4, 3–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bastian, F.; Alabouvette, C.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. The impact of arthropods on fungal community structure in Lascaux Cave. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 106, 1456–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, D.W.; Gray, M.A.; Lyles, M.B.; Northup, D.E. The transport of nonindigenous microorganisms into caves by human visitation: A case study at Carlsbad Caverns National Park. Geomicrobiol. J. 2014, 31, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogórek, R.; Lejman, A.; Matkowski, K. Influence of the external environment on airborne fungi isolated from a cave. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2014, 23, 435–440. [Google Scholar]

- Ogórek, R.; Kurczaba, K.; Cal, M.; Apoznański, G.; Kokurewicz, T. A culture-based ID of micromycetes on the wing membranes of Greater mouse-eared bats (Myotis myotis) from the “Nietoperek” site (Poland). Animals 2020, 10, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderwolf, K.J.; Campbell, L.J.; Goldberg, T.L.; Blehert, D.S.; Lorch, J.M. Skin fungal assemblages of bats vary based on susceptibility to white-nose syndrome. ISME J. 2020, 15, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajewski, J.; Twarożek, M. The healthy aspects of the influence of moulds and mycotoxins. Alergia 2004, 13, 44–45. [Google Scholar]

- Frick, W.F.; Kingston, T.; Flanders, J. A review of the major threats and challenges to global bat conservation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2020, 1469, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Directive 92/43/EEC—The Conservation of Natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora in The Habitats Directive. 1992. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/legislation/habitatsdirective/index_en.htm (accessed on 18 December 2020).

- De Bruyn, L.; Gyselings, R.; Kirkpatrick, L.; Rachwald, A.; Apoznański, G.; Kokurewicz, T. Temperature driven hibernation site use in the Western barbastelle Barbastella barbastellus (Schreber, 1774). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokurewicz, T.; Apoznański, G.; Gyselings, R.L.; Kirkpatrick, L.; De Bruyn, L.; Haddow, J.; Glover, A.; Schofield, H.; Schmidt, C.; Bongers, F.; et al. 45 years of bat study and conservation in Nietoperek bat reserve (Western Poland). Nyctalus 2019, 19, 252–269. [Google Scholar]

- Bensch, K.; Braun, U.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W. The genus Cladosporium. Stud. Mycol. 2012, 72, 1–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frisvad, J.C.; Samson, R.A. Polyphasic taxonomy of Penicillium subgenus Penicillium. A guide to identification of food and air-borne terverticillate Penicillia and their mycotoxins. Stud. Mycol. 2004, 49, 1–174. [Google Scholar]

- Chilvers, M.I.; du Toit, L.J. Detection and identification of Botrytis species associated with neck rot, scape blight, and umbel blight of onion. Plant. Health Prog. 2006, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Samson, R.A.; Visagie, C.M.; Houbraken, J.; Hong, S.B.; Hubka, V.; Klaassen, C.H.W.; Perrone, G.; Seifert, K.A.; Susca, A.; Tanney, J.B.; et al. Phylogeny, identification and nomenclature of the genus Aspergillus. Stud. Mycol. 2014, 78, 141–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Q.; Jiang, J.R.; Zhang, G.Z.; Cai, L.; Crous, P.W. Resolving the Phoma enigma. Stud. Mycol. 2015, 82, 137–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Visagie, C.M.; Hirooka, Y.; Tanney, J.B.; Whitfield, E.; Mwange, K.; Meijer, M.; Amend, A.S.; Seifert, K.A.; Samson, R.A. Aspergillus, Penicillium and Talaromyces isolated from house dust samples collected around the world. Stud. Mycol. 2014, 78, 63–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Doyle, J.J.; Doyle, J.L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 1987, 19, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ogórek, R.; Piecuch, A.; Višňovská, Z.; Cal, M.; Niedźwiecka, K. First report on the occurence of dermatophytes of Microsporum cookei clade and close affinities to Paraphyton cookei in the Harmanecká Cave (Veľká Fatra Mts., Slovakia). Diversity 2019, 11, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J.W. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNAgenes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Ogórek, R.; Dyląg, M.; Kozak, B. Dark stains on rock surfaces in Driny Cave (Little Carpathian Mountains, Slovakia). Extremophiles 2016, 20, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dietz, C.; von Helversen, O. Illustrated Identification Key to the Bats of Europe; Technol Report; Dietz & von Helversen: Tuebingen & Erlangen, Germany, 2004; p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Bliss, C.I. The method of probits. Science 1934, 79, 38–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spellerberg, I.F.; Fedor, P. A tribute to Claude Shannon (1916–2001) and a plea for more rigorous use of species richness, species diversity and the ‘Shannon–Wiener’ Index. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2003, 12, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumaresan, D.; Wischer, D.; Stephenson, J.; Hillebrand-Voiculescu, A.; Murrell, J.C. Microbiology of Movile Cave—Chemolithoautotrophic ecosystem. Geomicrobiol. J. 2014, 31, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusz, W.; Baturo-Cieśniewska, A.; Zagożdżon, P.P.; Ogórek, R. Mycobiota of the disused ore mine of Marcinków in Śnieżnik Masiff (western Poland). J. Mt. Sci. 2017, 14, 2448–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Villar, D.; Lojen, S.; Krklec, K. Is global warming affecting cave temperatures? Experimental and model data from a paradigmatic case study. Clim. Dyn. 2015, 45, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammola, S.; Piano, E.; Cardoso, P.; Vernon, P.; Domínguez-Villar, D.; Culver, D.C.; Pipan, T.; Isaia, M. Climate change going deep: The effects of global climatic alterations on cave ecosystems. Anthr. Rev. 2019, 6, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Solache, M.A.; Casadevall, A. Global warming will bring new fungal diseases for mammals. mBio 2010, 1, e00061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nadkarni, N.M.; Solano, R. Potential effects of climate change on canopy communities in a tropical cloud forest: An experimental approach. Oecologia 2002, 131, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Tian, J.; Xiang, M.; Liu, X. Living strategy of cold-adapted fungi with the reference to several representative species. Mycology 2017, 8, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piecuch, A.; Ogórek, R. Quantitative and qualitative assessment of mycological air pollution in a dormitory bathroom with high humidity and fungal stains on the ceiling. Case Study. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2020, 30, 1955–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyron, S.; Lazzari, A.; Riccucci, M.; Calvini, M.; Varese, G.C. First mycological investigations on Italian bats. Hystrix 2011, 22, 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Deshmukh, S.K.; Rai, M.K. Biodiversity of Fungi: Their Role in Human Life; Science Publishers: Enfield, NH, USA, 2005; p. 460. [Google Scholar]

- Holz, P.H.; Lumsden, L.F.; Marenda, M.S.; Browning, G.F.; Hufschmid, J. Two subspecies of bent-winged bats (Miniopterus orianae bassanii and oceanensis) in southern Australia have diverse fungal skin flora but not Pseudogymnoascus destructans. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotedar, R.; Kolecka, A.; Boekhout, T.; Fell, J.W.; Anand, A.; Al Malaki, A.; Zeyara, A.; Al Marri, M. Naganishia qatarensis sp. nov., a novel basidiomycetous yeast species from a hypersaline marine environment in Qatar. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 2924–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coemans, E. Quelques hyphomycetes nouveaux. 1. Mortierella polycephala et Martensella pectinata. Bull. Acad. R. Sci. Belg. 1863, 15, 536–544. [Google Scholar]

- Dauphin, J. Contribution à l’étude de Mortiérellées. Ann. Sci. Nat. Bor. 1908, 8, 1–112. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Hyde, K.D.; Hongsanan, S.; Jeewon, R.; Bhat, D.J.; Mckenzie, E.H.C.; Gareth Jones, E.B.; Phookamsak, R.; Ariyawansa, H.; Boonmee, S.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Fungal diversity notes 367–490: Taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions to fungal taxa. Fungal Divers. 2016, 80, 1–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboutalebian, S.; Mahmoudi, S.; Okhovat, A.; Khodavaisy, S.; Mirhendi, H. Otomycosis due to the rare fungi Talaromyces purpurogenus, Naganishia albida and Filobasidium magnum. Mycopathologia 2020, 185, 569–575. [Google Scholar]

- Niazi, S.; Hassanvand, M.S.; Mahvi, A.H.; Nabizadeh, R.; Alimohammadi, M.; Nabavi, S.; Faridi, S.; Dehghani, A.; Hoseini, M.; Moradi-Joo, M.; et al. Assessment of bioaerosol contamination (bacteria and fungi) in the largest urban wastewater treatment plant in the Middle East. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 16014–16021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogórek, R. Speleomycology of air in Demänovská Cave of Liberty (Slovakia) and new airborne species for fungal sites. J. Cave Karst Stud. 2018, 80, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, V.; Poulson-Cook, S.; Moldenhauer, J. Comparative mold and yeast recovery analysis (the effect of differing incubation temperature ranges and growth media). PDA J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 1998, 52, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Minnis, A.M.; Lindner, D.L. Phylogenetic evaluation of Geomyces and allies reveals no close relatives of Pseudogymnoascus destructans, comb. nov., in bat hibernacula of Eastern North America. Fungal Biol. 2013, 117, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blehert, D.S.; Hicks, A.C.; Behr, M.; Meteyer, C.U.; Berlowski-Zier, B.M.; Buckles, E.L.; Coleman, J.T.; Darling, S.R.; Gargas, A.; Niver, R.; et al. Bat white-nose syndrome: An emerging fungal pathogen? Science 2009, 323, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drees, K.P.; Lorch, J.M.; Puechmaille, S.J.; Parise, K.L.; Wibbelt, G.; Hoyt, J.R.; Sun, K.; Jargalsaikhan, A.; Dalannast, M.; Palmer, J.M.; et al. Phylogenetics of a fungal invasion: Origins and widespread dispersal of White-Nose Syndrome. mBio 2017, 8, e01941-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Meletiadis, J.; Meis, J.F.G.M.; Mouton, J.W.; Verweij, P.E. Analysis of growth characteristics of filamentous fungi in different nutrient media. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Littman, M.L. A culture medium for the primary isolation of fungi. Science 1947, 106, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogórek, R.; Kalinowska, K.; Pląskowska, E.; Baran, E.; Moszczyńska, E. Zanieczyszczenia powietrza grzybami na różnych podłożach hodowlanych w wybranych pomieszczeniach kliniki dermatologicznej. Część I/Mycological air pollutions on different culture mediums in selected rooms of dermatology department. (Part I). Mikol. Lek. 2011, 18, 30–38. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Eisen, J.A. Environmental Shotgun Sequencing: Its Potential and Challenges for Studying the Hidden World of Microbes. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Ma, X.; Ma, Y.; Maoa, L.; Wu, F.; Maa, X.; Ana, L.; Fenga, H. Seasonal dynamics of airborne fungi in different caves of the Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2010, 64, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilarek, M. Polska Norma PN-89/Z-04111/03. Ochrona Czystości Powietrza. Badania Mikrobiologiczne. Oznaczanie Liczby Grzybów Mikroskopowych w Powietrzu Atmosferycznym (Imisja) Przy Pobieraniu Próbek Metodą Aspiracyjną i Sedymentacyjną/Polish Norm PN-89/Z-04111/03. Determination of the Number of Bacteria in the Atmospheric Air by aspiration and Sedimentation Sampling; Polski Komitet Normalizacji Miar i Jakości: Warszawa, Poland, 1989. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Indoor Air Quality: Biological Contaminants Report on a WHO Meeting, Rautavaara, 29 August–2 September 1988; WHO Regional Publications, European Series No. 31; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, C.J.; Straus, D.C. The roles of Penicillium and Aspergillus in Sick Building Syndrome. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 55, 215–238. [Google Scholar]

- Sorrenti, V.; Di Giacomo, C.; Acquaviva, R.; Barbagallo, I.; Bognanno, M.; Galvano, F. Toxicity of ochratoxin A and its modulation by antioxidants: A review. Toxins 2013, 5, 1742–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Egbuta, M.A.; Mwanza, M.; Babalola, O.O. Health risks associated with exposure to filamentous fungi. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frisvad, J.C.; Thrane, U. Mycotoxin production by commonfilamentous fungi. In Introduction to Food- and Air Borne Fungi, 6th ed.; Samson, R.A., Hoekstra, E.S., Frisvad, J.C., Filtenborg, O., Eds.; Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 321–330. [Google Scholar]

- Talcott, P.A. Mycotoxins. In Small Animal Toxicolo, 3rd ed.; Peterson, M.E., Talcott, P.A., Eds.; Elsevier Saunders: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2013; pp. 677–682. [Google Scholar]

- Frisvad, J.C.; Filtenborg, O. Terverticillate penicillia: Chemo-taxonomy and mycotoxin production. Mycologia 1989, 81, 837–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahomed, K.; Mlisana, K. Penicillium species: Is it a contaminant or pathogen? Delayed diagnosis in a case of pneumonia caused by Penicillium chrysogenum in a systemic lupus erythematosis patient. Int. J. Trop. Med. Publ. Health 2016, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geltner, C.; Lass-Flör, C.; Bonatti, H.; Müller, L.; Stelzmüller, I. Invasive pulmonary mycosis due to Penicillium chrysogenum: A new invasive pathogen. Transplantation 2013, 95, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latgé, J.-P.; Chamilos, G. Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillosis in 2019. Clin. Microb. Rev. 2019, 33, e00140-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, B.H. Aspergillosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 1870–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, J.C.; Jensen, H.E.; Nillius, A.M. Aspergillus and aspergillosis. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 1992, 30, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kredics, L.; Varga, J.; Kocsubé, S.; Rajaraman, R.; Raghavan, A.; Dóczi, I.; Bhaskar, M.; Németh, T.M.; Antal, Z.; Venkatapathy, N.; et al. Infectious keratitis caused by Aspergillus tubingensis. Cornea 2009, 28, 951–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarros, I.C.; Veiga, F.F.; Corrêa, J.L.; Barros, I.L.E.; Gadelha, M.C.; Voidaleski, M.F.; Pieralisi, N.; Pedroso, R.B.; Vicente, V.A.; Negri, M.; et al. Microbiological and virulence aspects of Rhodotorula mucilaginosa. EXCLI J. 2020, 19, 687–704. [Google Scholar]

- Scholtz, H.D.; Meyer, L. Mortierella polycephala as a cause of pulmonary mycosis in cattle. Berl. Muench Tieraerztl. Wochenschr. 1965, 78, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kantarcioǧlu, A.S.; Boekhout, T.; De Hoog, G.S.; Theelen, B.; Yücel, A.; Ekmekci, T.; Fries, B.; Ikeda, R.; Koslu, A.; Altas, K. Subcutaneous cryptococcosis due to Cryptococcus diffluens in a patient with sporotrichoid lesions case report, features of the case isolate and in vitro antifungal susceptibilities. Med. Mycol. 2007, 45, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rapiejko, P.; Lipiec, A.; Wojdas, A.; Jurkiewicz, D. Threshold pollen concentration necessary to evoke allergic symptoms. Int. Rev. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2004, 10, 91–94. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, T.; Ajello, L.; Matsuda, T.; Szaniszlo, P.J.; Walsh, T.J. Developments in hyalohyphomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis. Med. Mycol. 1994, 32, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahan, T.A.; Sorenson, W.G.; Paulauskis, J.D.; Morey, R.; Lewis, D.M. Concentration- and time-dependent upregulation and release of the cytokines MIP-2, KC, TNF, and MIP-1 α in Rat alveolar macrophages by fungal spores implicated in airway inflammation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Bio. 1998, 18, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Study Site Number | Locations 1 | Section No. 1 | Dimensions of Underground Corridors | Temperature (°C) ± SD 2 (n = 9) | Relative Humidity (%) ± SD (n = 9) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (m) | Height (m) | Width (m) | Volume (m3) | |||||||

| I | Entrance to object | near 7.10.2 | ― | ― | ― | ― | 8.77 ± 0.07 | f 3 | 56.20 ± 0.24 | e |

| II | from security gate to Bhf Heinrich | 7.8 | 669.0 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 2943.6 | 10.35 ± 0.05 | b | 67.65 ± 0.59 | d |

| III | from Bhf Gustav to Bhf Friedrich | 7.5 | 1075.0 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 12,728.0 | 10.50 ± 0.00 | a | 80.68 ± 0.07 | c |

| IV | from Bhf Friedrich of Section 7.2 | beginning of 7.2 | 806.0 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 3546.4 | 9.63 ± 0.10 | c | 83.72 ± 0.61 | a |

| V | center of 7.2 | 9.31 ± 0.05 | d | 82.06 ± 0.25 | b | |||||

| VI | end of 7.2 | 8.93 ± 0.07 | e | 80.63 ± 0.04 | c | |||||

| Bat Species | Number of Bats | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. 7.2 (Study Site No. IV, V, and VI) | No. 7.5 (Study Site No. III) | No. 7.8 (Study Site No. II) | |

| Myotis myotis | 497 | 2052 | 3 |

| Myotis daubentonii | 20 | 411 | 1 |

| Myotis nattereri | 15 | 287 | 0 |

| Barbastella barbastellus | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Plecotus auritus | 4 | 21 | 0 |

| Myotis dasycneme | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Other species | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| In total | 537 | 2775 | 4 |

| In total per 1 m3 of the corridor | 0.151 | 0.218 | 0.001 |

| % of M. myotis to the total bat number | 92.6 | 73.9 | 75.0 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Borzęcka, J.; Piecuch, A.; Kokurewicz, T.; Lavoie, K.H.; Ogórek, R. Greater Mouse-Eared Bats (Myotis myotis) Hibernating in the Nietoperek Bat Reserve (Poland) as a Vector of Airborne Culturable Fungi. Biology 2021, 10, 593. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10070593

Borzęcka J, Piecuch A, Kokurewicz T, Lavoie KH, Ogórek R. Greater Mouse-Eared Bats (Myotis myotis) Hibernating in the Nietoperek Bat Reserve (Poland) as a Vector of Airborne Culturable Fungi. Biology. 2021; 10(7):593. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10070593

Chicago/Turabian StyleBorzęcka, Justyna, Agata Piecuch, Tomasz Kokurewicz, Kathleen H. Lavoie, and Rafał Ogórek. 2021. "Greater Mouse-Eared Bats (Myotis myotis) Hibernating in the Nietoperek Bat Reserve (Poland) as a Vector of Airborne Culturable Fungi" Biology 10, no. 7: 593. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10070593

APA StyleBorzęcka, J., Piecuch, A., Kokurewicz, T., Lavoie, K. H., & Ogórek, R. (2021). Greater Mouse-Eared Bats (Myotis myotis) Hibernating in the Nietoperek Bat Reserve (Poland) as a Vector of Airborne Culturable Fungi. Biology, 10(7), 593. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10070593