Simple Summary

Trichoderma spp. are common soil microorganisms that play an important role in limiting phytopathogenic microorganisms, improving plant growth and degrading plant biomass. Often the determining factors affecting the growth and maintenance of viability of Trichoderma spp. are the composition and condition of the growth medium. This study provides information on post-treatment procedures that would improve the viability of T. asperellum biomass and the antifungal activity obtained from submerged cultivation in a bioreactor. The aim of the study was to determine the viability of fungal biomass and competitiveness against a phytopathogen after treatment with hydrochloric acid, copper (II) sulphate and starch, alone or in combination.

Abstract

T. asperellum MSCL 309 was used in the study. T. asperellum was grown in the stirred bioreactor under submerged cultivation. The resulting biomass was filtered to obtain a thick biomass. The viability and antifungal activity of T. asperellum biomass samples were determined simultaneously by studying the colonization of the malt extract agar medium surface and its competitiveness with the plant pathogenic fungus Fusarium graminearum using in vitro dual culture experiments. Treatment with starch, alone or in combination with copper (II) sulphate and/or hydrochloric acid did not significantly affect fungal viability compared to control. An important factor in maintaining viability was the addition of hydrochloric acid, which significantly increased the storage life of biomass. In all post-treatments, F. graminearum was overgrown with T. asperellum in seven days, and accordingly, the larger the area occupied by T. asperellum, the smaller the area of F. graminearum colonization. Viability and antifungal activity of T. asperellum persisted throughout the experiment, at least for eight weeks. All the post-treatment methods we studied improved the viability and antifungal activity of Trichoderma, at least in terms of the area of the colonized surface. For the development of long-term viable and active T. asperellum preparations, we recommend the use of acidification of T. asperellum biomass obtained by submerged fermentation.

1. Introduction

Trichoderma species are soil fungi whose most important functions in the ecosystem are to degrade plant biomass, but they also limit phytopathogenic microorganisms and improve plant growth [1,2]. For more than 70 years, Trichoderma spp. have been used in crop production as biocontrol agents, biofertilizers and biostimulants [3]. The genus Trichoderma also plays an important role in the bioremediation of contaminated soils [4,5]. As these fungi are widespread in the soil, such biopreparations do not create an imbalance in the ecosystem. Trichoderma spp. are highly adaptive to the environment, and their growth rate is generally higher than that of plant pathogens. Trichoderma spp. can compete with adjacent pathogenic microorganisms for a zone of existence or nutrients, thereby inhibiting the growth of pathogens [1]. The main mechanisms of biocontrol of Trichoderma spp. are antibiosis, competition and mycoparasitism [6]. Trichoderma spp. have shown the ability to compete, for example, with plant pathogenic and mycotoxigenic fungi of the genus Fusarium in vitro in dual confrontation assays [7]. In plant experiments, they reduce the incidence and severity of diseases, mainly as preventive agents and by secreting phytohormones and cell membrane degrading enzymes [8]. Secondary metabolites synthesized by Trichoderma play an important role both in chemical protection against plant pathogens and in communication with other organisms [9].

The composition of the medium and the conditions under which fungi of the genus Trichoderma are cultivated have a significant effect on their growth and viability. There are two general approaches regarding Trichoderma fermentation: submerged (liquid) fermentation (SmF) and solid-state fermentation (SSF) [10]. In comparison to SmF, SSF has lower capital costs and higher productivity, and the produced propagules are more stable, simpler and have cheaper downstream processing, lower wastewater discharge and reduced energy requirements. However, SmF processes are much less labor intensive and easier to control and automate [11]. Trichoderma growth, conidiation and the production of antimicrobial compounds are highly affected by the oxygen transfer rate controlled by aeration and agitation [12]. The morphology of the fungi is also influenced by the composition of the nutrient components in the medium, pH, temperature, etc. [13], and the efficacy of biocontrol agents to suppress plant pathogens varies depending on the nutrient composition of the medium [14].

Trichoderma species reproduce asexually by producing three major types of propagules (mycelia, conidia, and chlamydospores) [12,15] that possess distinct physiological characteristics in terms of production, stability, and biocontrol activity. Trichoderma fungi usually form branched hyphae and chlamydospores under submerged fermentation, but conidia are rarely formed [12,16]. In nature, many species also form ascospores in perithecia [17]. In practice, chlamydosporal preparations are used in some cases [18], but most commercial formulations use aerial conidia [19]. Several soluble and volatile secondary metabolites—peptaibols, polyketides, pyrones, terpenes, etc.—are synthesized by the fungal mycelium just during conidiation [20]. According to available information, we fully agree with [21] that no reports on yields, fermentation time, production costs of liquid fermentation, and comparison with aerial conidia in terms of bioefficacy are available. Formulation studies have focused on stabilization processes for Trichoderma biomass, conidia, and chlamydospores [22]. Despite these attempts, low yields, long fermentation times, and poor storage stability have hampered the use of SmF.

Spores produced by the aerial mycelium of Trichoderma show both higher resistance and longer viability after storage than those produced in a liquid medium [23]. As noted in [16], conidia produced by SSF survive longer than chlamydospores and exhibit almost equal bioefficacy in reducing root rot incidence compared to chlamydospores produced under SmF. As conidia are formed predominantly in aerated conditions, this has led to a two-step production procedure: SmF application for mycelium and SSF application for sporulation [24].

The posttreatment of biomass obtained during SmF can be considered the first step in the two-step production procedure. The posttreatment possibilities have been studied in experiments with the genus Trichoderma [7] by adding substances to the biomass of T. asperellum that reduce metabolic activity and/or increase nutrient uptake. Acidification with hydrochloric acid inhibits the rate of fungal metabolism; low concentrations of copper sulphate act as a metabolic inhibitor, while starch serves as a source of nutrients to prolong shelf life. According to [7], biomass in Petri plates retains viability and antifungal activity for at least 6 months when stored at room temperature. The importance of oxygen availability in maintaining fungal viability should also be considered. It should also be noted that the environmental factors during fermentation influence both the antagonistic properties and duration of cell viability.

The present study aimed to assess the viability and antifungal activity of T. asperellum MSCL 309 biomass obtained in submerged fermentation and its preservation after treatment of biomass with hydrochloric acid, copper sulphate, starch, and their combinations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cultivation of Microorganisms

Trichoderma asperellum MSCL 309 was isolated from a temperate climate region (Latvia) and identified by amplification of the rRNA gene region with specific primers [25].

T. asperellum MSCL 309 was used in this study as a model fungus and Fusarium graminearum MSCL 435 as the model plant pathogen. Both fungi were grown on malt extract agar (MEA, Biolife, Milan, Italy) [26] in Petri plates at 20 ± 2 °C for 7 days.

To prepare the inoculum, T. asperellum was grown statically in malt extract broth in flasks at 28 °C for 57 h, followed by shaking at 150 rpm for 8 h. T. asperellum submerged cultivations were performed in a 15 L stirred-tank bioreactor (EDF-15.1, Biotehniskais centrs, Riga, Latvia) with one standard Rushton turbine (bottom location) and two propeller type turbines (middle located for flow up; above located for flow down). The medium used contained sugar (20 g/L) and yeast extract (3 g/L). 11.4 l of medium and 600 mL of inoculum were added to the bioreactor. The medium was sterilized for 30 min at 1.1 atm and 121 °C. Cultivation set points were a temperature of 28 °C, pH of 6.5 ± 0.2, and dissolved oxygen concentration of 30 ± 5%. Agitation limits ranged from 200 rpm up to 750 rpm, and the aeration rate was 1.67 standard liters per minute. The duration of cultivation was 65 h.

2.2. Posttreatment of T. asperellum Biomass

The obtained biomass was filtered through three layers of gauze to obtain a thick biomass with a moisture content of 88.2%. Moisture content was determined by weighing 10 g of biomass and heating in an AGS 120/T250 moisture analyzer (Axis, Gdańsk, Poland) at 85 °C for 25 min. The biomass was weighed into 12 sterile Petri plates (with three repetitions) 50 mm in diameter, weighing 5 g of biomass on each plate. This biomass was treated in several ways (Table 1) by modifying the [7] method:

Table 1.

Biomass treatments.

- (1)

- HCl (Stanchem, Warszawa, Poland), adding 200 µL of 1 M HCl to achieve a pH of 4;

- (2)

- CuSO4×5H2O solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 2 mg/mL, adding 50 µL to 20 µg/mL (or 100 µg/5 g of biomass) treatment or 150 µL to 60 µg/mL (or 300 µg/5 g of biomass) treatment; and

- (3)

- organic potato starch (Aloja Starkelsen Ltd., Ungurpils, Alojas pagasts, Latvia), 500 mg, thoroughly mixed with biomass.

A total of 350 µL of sterile water was added for the control (treatment No. 1).

Samples were stored at 22 ± 1 °C and humidity was in the range of 55–65%. Each week, part of each sample was watered evenly with 4 mL of sterile distilled water. The viability and antifungal activity of T. asperellum were determined immediately after mixing the biomass with the substances, after 1 week, 2 weeks, 4 weeks, 6 weeks and 8 weeks.

2.3. Determination of Viability, Antifungal Activity and Micromorphology of T. asperellum

The viability and the antifungal activity of T. asperellum biomass samples were determined simultaneously by studying the colonization of the agar medium surface and its competitiveness with the plant pathogenic fungus F. graminearum [27]. Twelve Petri plates with MEA medium were prepared. Autoclaved sterilized filter paper discs with a diameter of 0.4 cm were uniformly moistened with a 1% suspension of T. asperellum prepared by mixing 0.1 g of T. asperellum biomass with 10 mL of sterile water. Biomass was collected and prepared in a laminar flow cabinet. A T. asperellum filter paper was placed on MEA medium at a distance of 4 cm from a 0.4 cm diameter F. graminearum agar plug cut from a previously prepared plate with seven-day-old culture. Petri plates with both cultures were stored for 7 days at room temperature 22 ± 1 °C. Viability was measured on the third day from the area of the colonized surface of T. asperellum and expressed as a percentage of the total surface area of the plate. Antifungal activity was determined on day seven, from the colonized surface area of F. graminearum. Fungal micromorphology was examined using a Leica DM 2000 microscope under 200 and 400× magnification, and images were recorded digitally with a Leica DFC 420 camera. ImageJ software 167 version 1.53e (National Institutes of Health, Washington, DC, USA) was used for image processing.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was performed in triplicate. The data were analyzed using the computer program RStudio, version 1.4.1103 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). For statistics, analysis of variance (ANOVA test) and Duncan’s new multiple range test (MRT) were used. Means were compared using the significance level p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Viability of T. asperellum

Submerged fermentation yielded 11 L of final product, resulting in 585.2 g of wet biomass and a wet biomass yield of 53.2 g/L. Biomass posttreatments were performed during the study, and the effects of several treatments on the duration of viability of the obtained T. asperellum biomass were compared at 5 different times. Immediately after biomass treatment, T. asperellum colonized 30.3 ± 1.4% of the total area of the Petri plates over three days (Table 2). No significant differences were observed between the colonized surface from the differently treated samples (p > 0.05).

Table 2.

Surface colonization with T. asperellum as a function of biomass storage time. Treatment of biomass: 1—control; 2—HCl; 3—CuSO4×5H2O 20 mg/L; 4—CuSO4×5H2O 60 mg/L; 5—HCl and CuSO4×5H2O 20 mg/L; 6—HCl and CuSO4×5H2O 60 mg/L; 7—starch; 8—HCl and starch; 9—CuSO4×5H2O 20 mg/L and starch; 10—CuSO4×5H2O 60 mg/L and starch; 11—HCl, CuSO4×5H2O 20 mg/L and starch; 12—HCl, CuSO4×5H2O 60 mg/L and starch. The standard deviations were calculated from three repetitions. A significant difference was established for all rows (p < 0.05). Significantly different mean values in the same column are indicated by different superscripts (a–e) (Duncan; p < 0.05).

The colonized surfaces of T. asperellum stored for one week showed significant differences between treatments. On one side, the smallest areas were observed in treatments No. 8 and No. 12, being 17.9% of the total area of the plate. On the other side, the highest values were observed in treatments No. 9 and No. 10, being 26.2–26.3%. After a week starch + acid affected colonization capacity and starch + Cu (on both concentrations) promoted colonization. Significant reductions in area % (p < 0.05) were observed for treatments No. 2, No. 4 and No. 12.

There were significant differences (p < 0.05) between the results from weeks one and two for all the treatments. For T. asperellum biomass stored for two weeks, the smallest area of the colonized surface was observed in treatment No. 8, where it was 28.5% of the plate area, and the highest values were observed in treatments No. 10, No. 11 and No. 12, where they were 41.1%, 40.0% and 40.2% of the plate area, respectively.

Samples of T. asperellum stored for four weeks colonized an even larger surface area than those stored for two weeks, i.e., 68.1 ± 5.4% of the total plate area. A significant difference (p < 0.05) between the two- and four-week results was observed for all treatments. After two weeks starch + acid affected colonization capacity and, starch + Cu (60) and starch + acid + Cu at both concentrations promoted colonization.

Significant changes (p < 0.05) between the fourth and sixth weeks were observed only for treatments No. 2, No. 3 and No. 10 and were due to an increase in colonized area. Samples of T. asperellum stored for six weeks were able to colonize 69.4% and 67.6% of treatments No. 1 and No. 7 and 83.0% of treatment No. 2, respectively. A significant difference (p < 0.05) between the six- and eight-week results was observed for treatment Nos. 1–5, No. 9, and No. 11.

Samples stored for eight weeks colonized from 52.2% of the surface for treatment No. 1 up to 71.5% of the surface for treatment No. 9. Overall, in the eighth week, Cu (60) and starch, as well as acid + Cu (60) and starch promoted the highest percentage of colonization compared to other treatments, but these data were not significantly different from treatments No. 2, No. 3, and No. 6 (p > 0.05). Colonization percentage in samples with treatments No. 1, No. 4, No. 5, No. 7, No. 8, No. 9. and No. 11 differed significantly from samples No. 2, No. 3, No. 6, No. 10, and No. 12 (p < 0.05), where surface colonization with T. asperellum was the highest.

3.2. Morphological Features and Antifungal Activity of T. asperellum

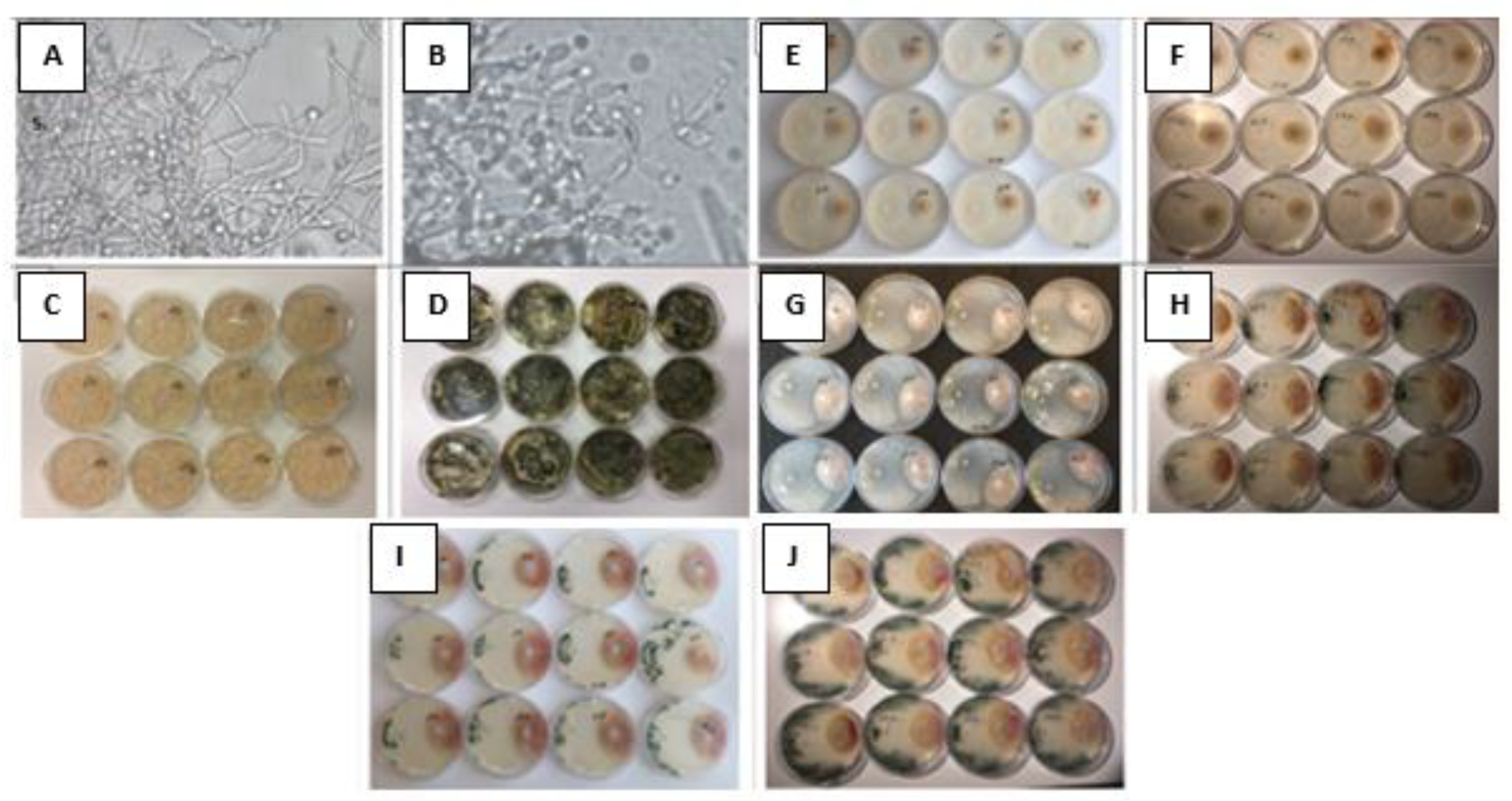

T. asperellum developed mycelium and chlamydospores during submerged fermentation (Figure 1A). Chlamydospores had formed at the hyphal tips as well as intercalary within hyphae. The resulting biomass was colourless (Figure 1C), viable (Table 2) and showed antifungal activity against F. graminearum that did not appear immediately or after three days (Figure 1E) but was observed after five and seven days of co-cultivation in Petri plates (Figure 1G,I). After two weeks of storage in Petri dishes, pigmentation began, and the Trichoderma biomass turned green (Figure 1D). Microscopy showed hyphae with conidiophores and conidia (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Different treated biomasses of T. asperellum and antagonistic action against F. graminearum in dual culture assays depending on the storage time of T. asperellum biomass. (A)—T. asperellum fresh biomass in 200× magnification. (B)—T. asperellum biomass after a storage period of two weeks or more in 400× magnification. (C)—Hyphae with chlamydospores in fresh biomass. (D)—Hyphae with conidiophores, phialides and conidia after a storage period of two weeks or more. Biomass storage time: (C,E,G,I)—0 days; (D,F,H,J)—two weeks. Antagonistic effect: (E,F)—after 3 days; (G,H)—after 5 days ((G)—on a black background); (I,J)—after 7 days.

In all treatments, F. graminearum was overgrown with T. asperellum in seven days, and accordingly, the larger the area occupied by T. asperellum the smaller the area colonized by F. graminearum, as shown in Figure 1. The antifungal activity of T. asperellum persisted throughout the experiment for at least eight weeks.

4. Discussion

Trichoderma submerged fermentation yields unpigmented biomass, usually without producing conidia [12] or substances whose biosynthesis involves the differentiation of hyphae in the atmosphere. Conidia have dispersing and resting functions in nature [28] and show a better long-term viability (an important feature for microbial preparations) than hyphae. The present experiments showed that posttreatment procedures (Table 1) of the obtained biomass had the capacity to induce conidia formation in T. asperellum mycelium. Biomass treatment methods were chosen to slow fungal metabolism while promoting conidiation. As reported in [7], the acidification of biomass to pH 4 and the addition of up to 10% additional nutrient starch to Trichoderma biomass improved its viability. Various species of the genus Trichoderma are known to be able to maintain viability in the range of pH 2 to pH 8 [29]. In several species of Trichoderma, low pH seems to be a determinant for the formation of conidia [30]. This study on T. asperellum MSCL 309 confirmed this fact.

Several heavy metal ions at low concentrations are required for fungal growth, but at higher concentrations, they can be toxic, completely inhibiting the development of microorganisms [31]. CuSO4, when added at low concentrations to biomass, acts as a metabolic inhibitor, inhibiting fungal growth and thus increasing the storage time of biomass [7]. Our results show that the addition of CuSO4 in combinations with HCl and starch produced high values of colonization, but they were not higher than those achieved by the application of HCl alone (Table 2). Considering the environmental toxicity of CuSO4 [32], we recommend using hydrochloric acid as a treatment option.

In addition to dissolved chemicals, air is also an important factor in mycelial differentiation, and in our experiments, air directly affected the mycelium during drying in Petri plates [33]. Oxygen is important for maintaining cell viability and metabolism, including antifungal activity. Another study [34] examined the storage time of T. viride by adding talc and charcoal to biomass. Samples with higher concentrations of talc retained greater viability than those with lower concentrations of talc, but preparations with added charcoal showed the opposite effect. Posttreatment of T. asperellum MSCL 309 with talc could also be investigated in the future.

With changes in the environment and stress conditions, we can probably explain the decrease in the surface area colonized by Trichoderma (Table 2) observed in the first week after the removal of biomass from the bioreactor. This biomass (Figure 1C) consisted of hyphae with chlamydospores (Figure 1A), but hyphae are known to grow at their tips; Ref. [35] described and analyzed in detail the morphogenesis of fungi under stressful conditions and its detailed cellular and molecular mechanisms, including the development of conidiophores at the air interface. It takes several days for conidia to form. In several species of Trichoderma, mechanical damage also triggers the production of conidia [36]. Research using gene knockout and complementation [37] identified the vel1 gene as a key regulator of morphogenetic traits (conidiogenesis, etc.), secondary metabolism (including antibiosis and pigmentation) and biocontrol (including mycoparasitism).

The study [38] showed that T. asperellum biomass, as long as it contains living cells, has antifungal activity, as demonstrated in in vitro dual culture experiments with the Fusarium head blight pathogen F. graminearum (Figure 1). Thus, the antifungal activity of T. asperellum depended on the viability of the biomass as measured by its colonized surface area, and acidification of the biomass with HCl (treatment No. 2) increased its antifungal activity compared to the untreated biomass.

Trichoderma inhibited the growth of the pathogenic mycelium. The fungal pathogen Fusarium graminearum is the most common causal agent of Fusarium head blight (FHB) in many parts of the world. This destructive disease, commonly but perhaps inappropriately known as scab, affects wheat, barley and other small grains both in temperate and in semitropical areas [39]. Diseases caused by F. graminearum are of particular concern because harvested grains frequently are contaminated with harmful mycotoxins such as deoxynivalenol (DON) [40]. DON is a mycotoxin produced by the plant pathogenic fungi F. graminearum and F. culmorum. Other mycotoxins produced by FHB-causing fungi include nivalenol, T-2 toxin, and zearalenone. Ingestion of mycotoxin-contaminated food and feed can lead to toxicosis in humans and animals, respectively [41].

According to published information, the T. asperellum strain MSCL 309 also inhibits the growth of the conifer root and butt rot fungi Heterobasidion annosum s.s. and H. parviporum [25].

5. Conclusions

All the posttreatment methods studied improved the viability of Trichoderma, at least in terms of the area of the colonized surface. Four of the five relatively viable treatments contained heavy metal copper (II) sulphate pentahydrate at 20 or 60 mg/L. To avoid contamination of environmentally friendly Trichoderma preparations with Cu, in the future, we recommend only biomass acidification with HCl. Results of HCl application did not differ significantly from the results of CuSO4 application. There was no synergy or antagonism between the addition of HCl and Cu sulphate. Treatment with starch, alone or in combination with CuSO4 and/or HCl, did not significantly affect fungal viability compared to the control.

In the future, we recommend the use of acidification of T. asperellum biomass obtained by submerged fermentation. Other parameters for fermentation and posttreatment procedures should be studied in more detail to obtain long-term viable T. asperellum preparations.

Author Contributions

M.S.: writing—final draft, data analysis. M.T.D.: conceptualization, data analysis, review and editing. A.R.: methodology. O.G. and V.N.: writing—review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was financed by the ERDF project No. 1.1.1.1/19/A/150 “Scale-up research of the microbiological soil fertilizer and biocontrol agent obtained in submerged and surface cultivation processes”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the 3rd round of the project “Strengthening the doctoral capacity of the University of Latvia within the framework of the new doctoral model”, project identification No. 8.2.2.0/20/I/006, UL registration No. ESS2021/434, co-financed by the European Social Fund.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Harman, G.E.; Howell, C.R.; Viterbo, A.; Chet, I.; Lorito, M. Trichoderma species—Opportunistic, avirulent plant symbionts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Druzhinina, I.; Chenthamara, K.; Zhang, J.; Atanasova, L.; Yang, D.; Miao, Y.; Rahimi, M.; Grujic, M.; Cai, F.; Pourmehdi, S.; et al. Massive lateral transfer of genes encoding plant cell wall-degrading enzymes to the mycoparasitic fungus Trichoderma from its plant-associated hosts. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14, e1007322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Bucio, J.; Pelagio-Flores, R.; Herrera-Estrella, A. Trichoderma as biostimulant: Exploiting the multilevel properties of a plant beneficial fungus. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 96, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacprzak, M.J.; Rosikon, K.; Fijalkowski, K.; Grobelak, A. The effect of Trichoderma on heavy metal mobility and uptake by Miscanthus giganteus, Salix sp., Phalaris arundinacea, and Panicum virgatum. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2014, 2014, 506142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, P.; Singh, P.C.; Mishra, A.; Chauhan, P.S.; Dwivedi, S.; Bais, R.T.; Tripathi, R.D. Trichoderma: A potential bioremediator for environmental clean-up. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2013, 15, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, M.; Kapoor, D.; Kumar, V.; Sheteiwy, M.S.; Ramakrishnan, M.; Landi, M.; Araniti, F.; Sharma, A. Trichoderma: The “secrets” of a multitalented biocontrol agent. Plants 2020, 9, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolombet, L.V.; Zhigletsova, S.K.; Kosareva, N.I.; Bystrova, E.V.; Derbyshev, V.V.; Krasnova, P.; Schisler, D. Development of fan extended shelf-life, liquid formulation of the biofungicide Trichoderma asperellum. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 24, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Gutiérrez, C.; Arroyave, C.; Llugany, M.; Poschenrieder, C.; Martos, S.; Pelaez, C. Trichoderma asperellum as a preventive and curative agent to control Fusarium wilt in Stevia rebaudiana. Biol. Control 2020, 155, e104537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, A.; Schmoll, M. Biology and biotechnology of Trichoderma. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 87, 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, V.; Basu, K. Mass multiplication of Trichoderma in bioreactor. In Trichoderma: Agricultural Applications and Beyond; Manoharachary, C., Singh, H.B., Varma, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 113–126. [Google Scholar]

- Onilude, A.A.; Adebayo-Tayo, B.C.; Odeniyi, A.O.; Banjo, D. Comparative mycelial and spore yield by Trichoderma viride in batch and fed-batch cultures. Ann. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, M.; Brar, S.K.; Tyagi, R.D.; Surampalli, R.Y.; Valero, J.R. Dissolved oxygen as principal parameter for conidia production of biocontrol fungi Trichoderma viride in non-Newtonian wastewater. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 33, 941–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papagianni, M. Fungal morphology and metabolite production in submerged mycelial processes. Biotechnol. Adv. 2004, 22, 189–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schisler, D.A.; Slininger, P.J. Effects of antagonist cell concentration and two strain mixtures on biological control of Fusarium dry rot of potatoes. Phytopathology 1997, 87, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gams, W.; Bissett, J. Morphology and identification of Trichoderma. In Trichoderma and Gliocladium: Basic Biology, Taxonomy and Genetics; Harman, G.E., Kubicek, C.P., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 1998; pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, R.D.; Rangeshwaran, R.; Anuroop, C.P.; Phanikumar, P.R. Bioefficacy and shelf life of conidial and chlamydospore formulations of Trichoderma harzianum Rifai. J. Biol. Control 2002, 16, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.K.; Horwitz, B.A.; Herrera-Estrella, A.; Schmoll, M.; Kenerley, C.M. Trichoderma research in the genome era. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2013, 51, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Su, S.; Zeng, X.; Bai, L.; Li, L.; Duan, R.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C. Inoculation with chlamydospores of Trichoderma asperellum SM-12F1 accelerated arsenic volatilization and influenced arsenic availability in soils. J. Integr. Agric. 2015, 14, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fravel, D.R. Commercialization and implementation of biocontrol. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2005, 43, 337–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivasithamparam, K.; Ghisalberti, E.L. Secondary metabolism in Trichoderma and Gliocladium. In Trichoderma and Gliocladium: Basic Biology, Taxonomy and Genetics; Harman, G.E., Kubicek, C.P., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 1998; pp. 139–191. [Google Scholar]

- Kobori, N.N.; Mascarin, G.M.; Jackson, M.A.; Schisler, D.A. Liquid culture production of microsclerotia and submerged conidia by Trichoderma harzianum active against damping-off disease caused by Rhizoctonia solani. Fungal Biol. 2015, 119, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.A.; Papavizas, G.C. Production of chlamydospores and conidia by Trichoderma spp. in liquid and solid growth media. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1983, 15, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, G.A.; Agosin, E.; Cotoras, M.; San Martin, R.; Volpe, D. Comparison of aerial and submerged spore properties for Trichoderma harzianum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1995, 125, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, R.B.; Faria, M.; Glare, T.R. A nonconventional two-stage fermentation system for the production of aerial conidia of entomopathogenic fungi utilizing surface tension. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 126, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolajeva, V.; Petrina, Z.; Vulfa, L.; Alksne, L.; Eze, D.; Grantina, L.; Gaitnieks, T.; Lielpetere, A. Growth and antagonism of Trichoderma spp. and conifer pathogen Heterobasidion annosum s.l. in vitro at different temperatures. Adv. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brito, J.P.; Ramada, M.H.; de Magalhães, M.T.; Luciano, P.S.; Ulhoa, C.J. Peptaibols from Trichoderma asperellum TR356 strain isolated from Brazilian soil. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, B.M.; Espinosa-Huerta, E.; Villordo-Pineda, E.; Rodríguez-Guerra, R.; Mora-Avilés, M.A. Trichoderma spp. native strains molecular identification and in vitro antagonistic evaluation of root phitopathogenic fungus of the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cv. Montcalm. Agrociencia 2017, 51, 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Carreras-Villasenor, N.; Sanchez-Arreguin, J.; Herrera-Estrella, A. Trichoderma: Sensing the environment for survival and dispersal. Microbiology 2012, 158, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Shahid, M.; Srivastava, M.; Pandey, S.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, V. Optimal physical parameters for growth of Trichoderma species at varying pH, temperature and agitation. J. Virol. Mycol. 2014, 3, 1000127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyaert, J.M.; Weld, R.J.; Stewart, A. Ambient pH intrinsically influences Trichoderma conidiation and colony morphology. Fungal Biol. 2010, 114, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovič, J.J.; Danilovič, G.; Čurčič, N.; Milinkovič, M.; Stošič, N.; Pankovič, D.; Raičevič, V. Copper tolerance of Trichoderma species. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2014, 66, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velicogna, J.R.; Schwertfeger, D.; Jesmer, A.; Beer, C.; Kuo, J.; DeRosa, M.C.; Scroggins, R.; Smith, M.; Princz, J. Soil invertebrate toxicity and bioaccumulation of nano copper oxide and copper sulphate in soils, with and without biosolids amendment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 217, 112222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carboué, Q.; Claeys-Bruno, M.; Bombarda, I.; Sergent, M.; Jolain, J.; Roussos, S. Experimental design and solid state fermentation: A holistic approach to improve cultural medium for the production of fungal secondary metabolites. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2018, 176, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, R.; Om, H. Shelf-life of Trichoderma viride in talc and charcoal based formulations. Ind. J. Agric. Sci. 2013, 83, 566–569. [Google Scholar]

- Riquelme, M.; Aguirre, J.; Bartnicki-García, S.; Braus, G.H.; Feldbrügge, M.; Fleig, U.; Hansberg, W.; Herrera-Estrella, A.; Kämper, J.; Kück, U.; et al. Fungal morphogenesis, from the polarized growth of hyphae to complex reproduction and infection structures. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2018, 82, e00068-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Oñate, M.A.; Esquivel-Naranjo, E.U.; Mendoza-Mendoza, A.; Stewart, A.; Herrera-Estrella, A.H. An injury-response mechanism conserved across kingdoms determines entry of the fungus Trichoderma atroviride into development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 1491814923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.K.; Kenerley, C.M. Regulation of morphogenesis and biocontrol properties in Trichoderma virens by a VELVET protein, Vel1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 2345–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askun, T. Introductory chapter. Fusarium: Pathogenicity, infections, diseases, mycotoxins and management. In Fusarium: Plant Diseases, Pathogen Diversity, Genetic Diversity, Resistance and Molecular Markers; Askun, T., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, M.; Jones, R.; Gallenberg, D. Scab of wheat and barley: A re-emerging disease of devastating impact. Plant Dis. 1997, 81, 1340–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bluhm, B.H.; Zhao, X.; Flaherty, J.E.; Xu, J.R.; Dunkle, L.D. RAS2 regulates growth and pathogenesis in Fusarium graminearum. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2007, 20, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegulo, S.N. Factors influencing deoxynivalenol accumulation in small grain cereals. Toxins 2012, 4, 1157–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).