1. Introduction

Dockless shared bicycles (DBS) have provided a convenient and affordable solution to city dwellers’ first-/last-mile trips since their emergence in 2015 due to the popularity of smartphones and mobile payments all over the world [

1]. DBS systems have been widely adopted by municipal governments to promote sustainable modes of transportation [

2]. Users can locate the bicycle fleet through the corresponding mobile app, and then they can unlock a bicycle by scanning a QR code on the bicycle they find. In addition, bicycle-sharing systems can reduce the emissions of harmful gases by reducing the use of fuel-burning vehicles and increasing the use of public transportation [

3]. Besides the contribution to sustainable transportation, DBS systems also help users improve physical health and bring about economic growth [

4].

In 2017, due to the explosive growth of DBS systems, the entire society started to pay attention to this industry to monitor its following development. Besides the convenience brought by the DBS systems, problems also came to light, such as lack of financial sustainability, vulnerability to vandalism, threat to local bicycle industries through low profitability for manufacturers [

5], poor management [

6], and disorderly parking; these negative aspects gradually overshadowed the advantages and convenience brought by DBS. Due to the free-floating mode, the problem of disorderly parking of DBS has been troubling users, enterprises, and governments. The bicycle-sharing industry was initially defined as a completely independent business model, with the government giving sufficient market freedom, which has brought both growth and regulatory challenges to the industry. Frenken and Schor [

7] propose that the expansion of the shared travel business may also bring about some disadvantages, such as the potential deterioration of travel demand, abuse of public space, increase in social injustice, platform monopoly, and long-term destruction of urban environment and social sustainability. In fact, the disorderly parking of shared bicycles in China has totally exceeded expectations since its large-scale nationwide launch. According to the “Shared Bicycle Summer Market Special Report for 2017” in China, 42% of DBS users claimed that disorderly parking was a serious problem and 26.8% said that the problem of disorderly parking was extremely serious [

8]. To achieve the sustainable development of the DBS industry, it is very urgent to find out how to promote users’ ordered parking behavior.

Previously, research related to the DBS industry has maintained a high degree of interest, and various countermeasures to different problems have also been continuously proposed. However, the problem of disorderly parking of shared bicycles is still difficult to solve. Previous research on dockless bicycle sharing has mainly focused on usage patterns [

9,

10,

11,

12], its influence on travel congestion and efficiency [

13,

14,

15], travel modes [

5,

16], and the environment [

17,

18,

19]. “Electric fencing” was also proposed to help reduce disorderly parking [

20]. However, the psychological mechanisms underlying users’ behavior remain unclear. Thus, this study focuses on the users’ disorderly parking behavior of DBS from the psychological perspective.

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) is one of the most widely used frameworks for studying individual behaviors [

21]. The TPB deconstructs people’s behavior into intention and perceived behavioral control (PBC), which in turn depends on three direct predictors: attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control. Attitude is one’s favorable or unfavorable evaluation of the consequences of the behavior; a subjective norm with regard to the perceived social pressure towards the consequences of the behavior; and PBC refers to the feasibility of executing the behavior in a corresponding context [

22]. These three determinants are influenced by behavioral, normative, and control beliefs. TPB has proven its applicability in many areas, such as the adoption of alternative transportation [

23], energy conservation [

24], low carbon consumption [

25], etc. Hence, this study uses TPB as the basic theoretical framework to construct the psychological mechanisms of DBS users’ parking behavior.

To examine the behavior of disorderly parking shared bicycles from the user perspective, the present research aimed to (1) propose an integrated theoretical framework to examine the influence of individual and social environmental factors on disorderly parking behavior; (2) conduct a questionnaire survey to collect data and test the framework; and (3) derive policy implications for DBS.

The structure of this paper is as follows. In

Section 2, we reviewed the studies about the theory of planned behavior and other constructs and then proposed hypotheses and the research structure. In

Section 3, we described the methodology. In

Section 4, we presented the procedure of data analysis and discussion. In

Section 5, we summarized the academic and practical contributions of this research and drew conclusions.

2. Hypothesis Deduction

In the research employing the theory of planned behavior, perceived risk is a construct that is often associated with negative expectations. Pavlou [

26] believes that perceived risk is the subjective prediction of some kind of loss that users encounter in the process of pursuing desired results. Dowling and Staelin [

27] mentioned that perceived risk is consumers’ perception of uncertainty and unfavorable results in the purchase of products or services. The PE construct of this study is a subjective expectation of the consequences of users’ disorderly parking of DBS, which is like the existence of perceived risk. A few studies focused on the usage, parking, or search costs [

28,

29,

30]. However, the impact of penalty incentives on users’ behavior is rare, hence we considered it necessary to explore the impact of punishment on users’ attitude to and behavioral intention of orderly parking behavior in this study. Based on this, the following hypotheses were proposed:

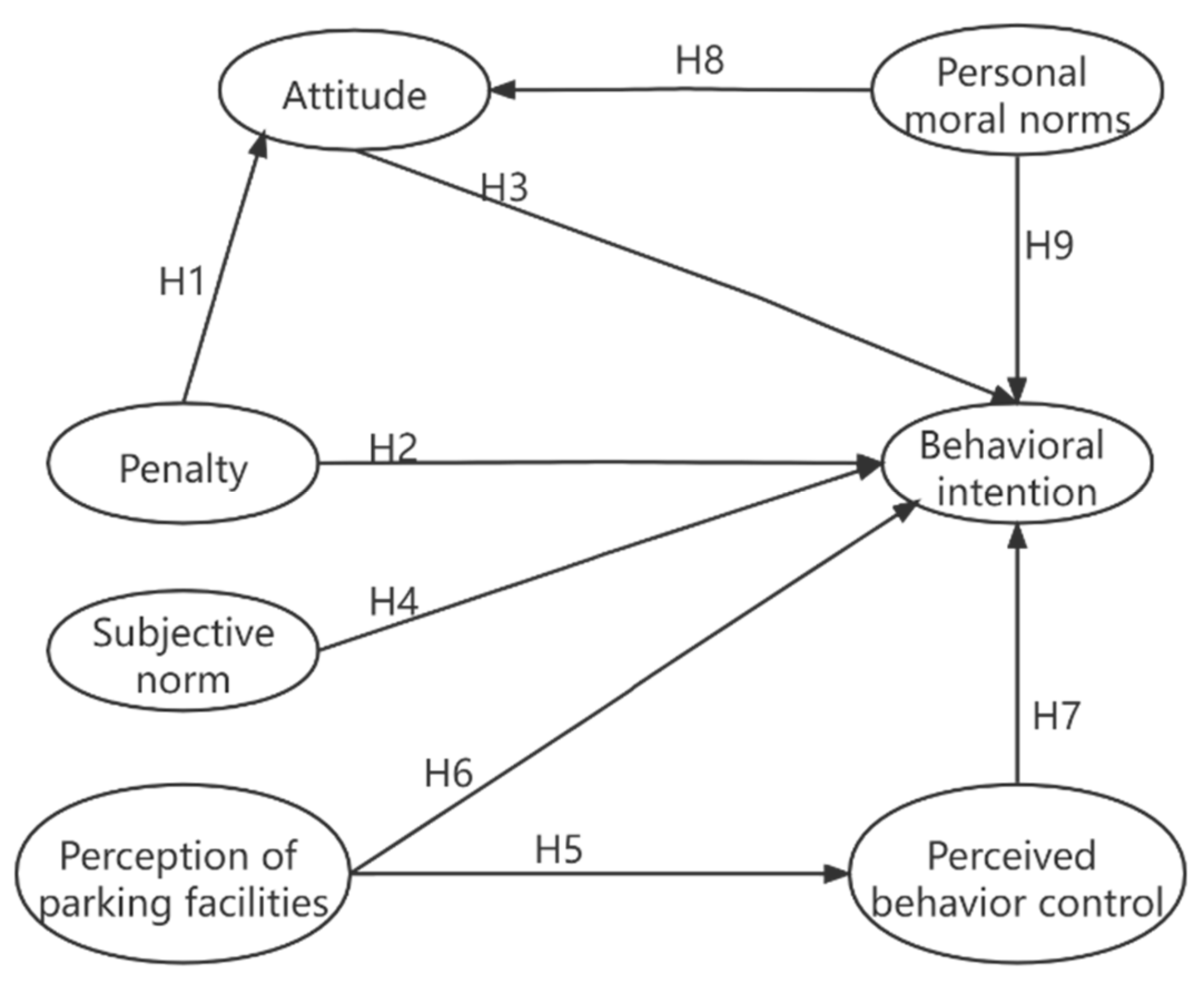

H1: Penalty (PE) has significant influence on attitudes (ATT) of DBS users.

H2: PE has significant influence on users’ behavioral intentions of orderly parking (BI).

The rapid development of the DBS industry has left many users unable to adapt to the new cycling culture, and most of them are still stuck in the old pattern of using their own bicycles. As the damage or loss of a personal bicycle owned by an individual leads to a negative loss, users are careful when parking it. On the contrary, DBS users do not have such concerns as the losses and consequences of disorderly parking will not cause a direct loss to users. In previous studies using the planned behavior theory, Bazargan-Hejazi et al. [

31] found that attitude had the strongest explanatory power for behavioral intention in the behavioral study of mobile phone use while driving; Valle et al. (2005) also confirmed the influence of attitude on behavior intention in their study on resource recovery participation behavior. Therefore, this study proposed hypothesis H3: ATT has a significant influence on BI.

According to the findings of [

32] on the causes of disorderly parking of shared bicycles, the publicity efforts of the government, enterprises, and the social media to regulate the parking behavior of shared bicycles are considered insufficient. The lack of publicity directly leads to the standard parking information not being able to cover a sufficiently wide user group, which results in difficulty in embedding and reinforcing regulated parking in the user community. Secondly, copycat behavior is also considered to be one of the reasons for disorderly parking by users of shared bicycles. Copycatting refers to the behavior of users who are influenced by the disorderly parking of other users and then park shared bicycles out of order. This phenomenon also reflects that users do not feel social pressure in the current social environment, especially the constraints of mutual supervision within the user group. In addition, Wan et al. [

33] confirmed that subjective norms significantly enhance the resource–recycle behavior in their research, and [

34] also confirmed the influence of subjective norms on behavioral intention in their research on the online learning mode of college students. Based on the above literature, this study proposed hypothesis H4: Subjective norms (SN) have a significant influence on BI.

The findings of Jiang, Ou, and Wei [

32] conclude those factors that hinder users from parking shared bicycles orderly are parking space, parking facilities, parking guidance, etc. These supporting facilities are the infrastructure that failed to follow up with the rapid development of the bicycle-sharing industry. The lack of parking facilities and parking guidance brings barriers to users’ regulated parking behavior to some extent. Taylor and Todd [

35] broke down the control belief into favorable conditions and self-efficacy. Favorable conditions are mainly related to time, money, and resources. It is easy to associate users’ disorderly parking of shared bicycles with external conditions such as time and parking facilities. Users’ DBS parking behavior is not only affected by factors such as their own time and willingness, but also by external conditions. DBS operators and governments have the obligation to provide users with corresponding parking facilities to ensure that users can park shared bicycles according to regulations. Therefore, the favorable conditions of control belief are specially translated into supporting parking facilities, which is called perception of parking facilities (PPF). Its operational definition is as follows: users’ perception of the adequacy of supporting facilities for DBS. To sum up, this study proposed hypothesis H5: PPF has a significant influence on the users’ perceived behavior control (PBC); H6: PPF has a significant influence on BI.

Si et al. [

36] found out that perceived behavioral control is one of the most important factors driving users’ sustainable usage intention of DBS. Lin [

37] argued that perceived behavioral control has a significant impact on behavioral intention in his research on user participation in online communities. In view of the wide applicability of the theory of planned behavior (TPB) in many fields, this study retained the main framework of the TPB and proposed hypothesis H7: PBC has a significant influence on BI.

Based on public attributes and social attributes of shared bicycle services, we believed that users’ moral attributes should be added to the research structure of this study. However, early studies were controversial as to how to integrate moral attributes into the original framework of the TPB. Ajzen [

22] believed that the ways in which moral norms influence behavior are mainly indirectly influenced by various constructs of the TPB, which also means that moral norms are highly correlated with some constructs of the TPB. However, Harland et al. [

38] believed that moral norms mainly affect behaviors directly, which means that they are not closely related to the original framework of the TPB. Klöckner [

39] conducted a meta-analysis of the studies at that time, and the results support Ajzen’s view. Klöckner believes that part of the influence of moral norms on intentions is mediated by attitudes. People will not simply consider whether the behavior is in line with personal values, but will consider the advantages and disadvantages of the behavior together. Shin and Hancer [

40] proved the influence of moral norms on purchasing intention when investigating consumers’ local food purchasing behavior. Leeuw et al. [

41] found that the inclusion of moral norms in the TPB could better predict behavioral intention, which increased the overall variation explanation from 61% to 73% in the case of consumers’ purchase of fair-trade products. Therefore, this study proposed hypothesis H8: Personal moral norms (PMN) have a significant influence on ATT; H9: PMN have a significant influence on BI.

This study focused on the relevant factors affecting the parking behavior of DBS users and combined the literature on the TPB and the parking behavior of DBS users, deduced and put forward nine hypotheses. The theoretical model of this study is as

Figure 1.

5. Discussion

Hypothesis 1 is invalid. The direct influence coefficient of the PE construct and the ATT construct was −0.101, and the bias-corrected significance was 0.300, which was not significant (

p > 0.05). That means the PE construct did not have a direct significant effect on the ATT construct, hence H1 was rejected. The penalty measures for DBS users’ disorderly parking can be divided into financial penalty, credit penalty, and right of use penalty. Practically, these measures not only have difficulty in enforcing, but also vary from person to person in terms of penalty extent. Early DBS companies did not have penalty measures for disorderly parking, hence users would not have the psychological burden of the corresponding negative consequences. At present, most DBS companies have implemented measures of riding range limitation and redistribution fee for disorderly parking, but disorderly parking has not been eradicated, which means that such soft penalty measures by increasing the use cost are acceptable to most users. Gao Liangpeng et al. believe that the disorderly parking behavior of DBS users could be regarded as a policy compliance problem related to users’ behavioral intentions and decision-making motivation, and economic incentives can help develop good parking habits [

58]. Therefore, in order to cultivate the users’ good parking habits, in addition to the current penalty measures, there is also a need for more incentives.

Hypothesis 2 is invalid. The direct influence coefficient between the PE construct and the BI construct was −0.039, and the bias-corrected significance was 0.552, which was not significant (

p > 0.05); the indirect influence coefficient between the PE construct and the BI construct was –0.022, the bias-corrected significance was 0.212, and the Z-value of multiplication was less than 1.96, which was also not significant (

p > 0.05); the overall influence coefficient between the PE construct and the BI construct was −0.061, and the bias-corrected significance was 0.416, which was not significant (

p > 0.05). The research of Yacan Wang et al. shows that users with a higher willingness to park in order believe that financial penalties and a credit system are less effective [

59]. In this study, 86.5% of the respondents had a Bachelor’s degree or similar professional qualification, which shows that the overall quality of the respondents was high. The average value of the BI construct was 6.12, the median was 6, and the mode was 6, which shows that the overall orderly parking intention of the respondents was high. Therefore, penalties for disorderly parking behavior have no significant influence on orderly parking behavior, which is also consistent with the research results of Wang, Jia, Zhou, Charlton, Hazen, and Applications [

59].

Hypothesis 3 is invalid. The direct influence coefficient between the ATT construct and the BI construct was 0.222, and the bias-corrected significance was 0.108, which was not significant (

p > 0.05). Users’ attitude towards orderly parking had no direct significant effect on orderly parking behavioral intention. This result does not comply with most studies based on the theory of planned behavior. It is speculated that since the development of shared bikes has gone through a period of time, the idea that shared bikes should be parked according to regulations has actually been deeply rooted in users’ minds, so that most users do have a correct and positive attitude toward orderly parking. However, in the end, attitude is no longer dominant when parking shared bicycles. Instead, other influencing factors are more important. This study speculated that after a period of development, in fact, the idea that shared bicycles need to be parked according to regulations has been deeply rooted in people’s minds, so that most users have a correct and positive attitude toward parking. However, when users park shared bicycles, the effect of attitude on behavioral intention is obviously weaker than other interfering factors. For example, some users are forced to park disorderly in places where vehicles are stranded during peak hours [

11] and suffer from poor use experience [

59] and lack of parking facilities [

60,

61].

Hypothesis 4 is invalid. The direct influence coefficient between the SN construct and the BI construct was 0.259, and the bias-corrected significance was 0.088, which was not significant (

p > 0.05). The SN construct did not have a direct significant effect on the BI construct. Similar results were also obtained in other fields of research. For example, Teo found SN had no significant influence on BI in his research about the technology usage behavior of teachers in the teaching process. They speculated that this was due to the teachers’ rich teaching experience, which meant that the teaching methods were relatively mature and could not be changed without the request of the school [

62]. Since most users have experience using private bicycles before using DBS, it is understandable that they follow their original parking behavior to park DBS. Lin also obtained the same result in the study of users’ behavior in using online communities. Lin speculated that this may be so since using online communities is a very self-centered behavior and that 43% of the respondents spent more than five hours a day online, which might have signified Internet dependence [

37]. Orderly parking is a prosocial behavior; it also requires a trade-off between personal convenience and benefits to society [

63,

64]. However, there is no widely accepted definition of orderly parking of DBS so far, hence bicycle-sharing users themselves do not feel the expectation of so-called orderly parking behavior from other users or friends and relatives around them.

Hypothesis 5 is valid. The direct influence coefficient between the PPF construct and the PBC construct was 0.464, and the bias-corrected significance was 0.001, which was significant (

p < 0.05). Users’ perception of parking facilities had a direct positive significant effect on the users’ perceived behavior control. This means that the more users perceive the supporting facilities of DBS, the higher their perceived control over the intention of orderly parking. Previous research found out that a lack of parking spots and limited parking facilities are associated with lower intentions of orderly parking [

59,

60,

61]. This is also consistent with our findings.

Hypothesis 6 is valid. The direct influence coefficient between the PPF construct and the BI construct was –0.293, and bias-corrected significance was 0.003, which was significant (p < 0.05). The indirect influence coefficient between the PPF construct and the BI construct was 0.212, and the bias-corrected significance was 0.001. The Z-value of the multiplication method was greater than 1.96, which was significant (p < 0.05). The overall influence coefficient between the PPF construct and the BI construct was −0.081, and the bias-corrected significance was 0.435, which was not significant (p > 0.05). Such a result was obviously different from the author’s expectations. According to the results, after the addition of DBS parking facilities and equipment, users’ perception of parking facilities would be improved, yet users’ behavioral intention of orderly parking would then decrease. The possible explanation here is that when the parking facilities for DBS have already met the demand, if the facilities continue to be added, the psychological construct of parking bicycles in a standardized way of DBS users would be relaxed, and then the expectations would be violated. On the other hand, due to the addition of more DBS parking facilities, it is easier for users to park DBS in good order. In other words, with the cost of orderly parking decreased, through mediation of the PBC construct, the behavioral intention of orderly parking would be significantly increased among DBS users. The addition of more supporting facilities for DBS would also enhance users’ behavioral intention of orderly parking. However, considering the positive and negative direct and indirect effects, the addition of supporting facilities for DBS cannot significantly affect users’ behavioral intentions of orderly parking overall; that is, complete supporting facilities for DBS cannot achieve the effect of eliminating users’ disorderly parking behaviors.

Hypothesis 7 is valid. The direct influence coefficient between the PBC construct and the BI construct was 0.456, and the bias-corrected significance was 0.001, which was significant (p < 0.05). The PBC construct can produce a direct positive significant effect on the BI construct. This indicates that the enhancement of users’ control over orderly parking of DBS can significantly improve the orderly parking intention, that is, users’ behavioral intention of orderly parking is amplified.

Hypothesis 8 is valid. The direct influence coefficient between the PMN construct and the ATT construct was 0.569, and the bias-corrected significance was 0.001, which was significant (p < 0.05). The PMN construct had a direct positive significant effect on the ATT construct. This indicates that the stronger the users’ moral condemnation of disorderly parking, the better their attitude is when parking shared bicycles in accordance with the regulations, that is, users’ strict moral constraints make them have a better attitude to orderly parking behavior.

Hypothesis 9 is valid. The direct influence coefficient between the PMN construct and the BI construct was 0.343, and the bias-corrected significance was 0.002, which was significant (

p < 0.05). The indirect influence coefficient between the PMN construct and the BI construct was 0.126, the bias-corrected significance was 0.068, and the z-value of the multiplication method was less than 1.96, which was not significant (

p > 0.05). The overall influence coefficient between the PMN construct and the BI construct is 0.469, and the bias-corrected significance was 0.002, which was significant (

p > 0.05). The PMN construct had a direct and significant effect on the BI construct, and although it did not have an indirect and significant effect, it can still have an overall significant effect on the BI construct. Fujii [

65] pointed out that activating moral obligation would be effective in increasing orderly parking behavioral intention, but not sufficiently effective with respect to decreasing the behavior. This indicates that the stronger the users’ moral condemnation of disorderly parking, the stronger the users’ behavioral intention of parking according to the regulations when using shared bicycles. In other words, users’ strict moral constraints amplify their behavioral intention of orderly parking.