Disinformation in Social Networks and Bots: Simulated Scenarios of Its Spread from System Dynamics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

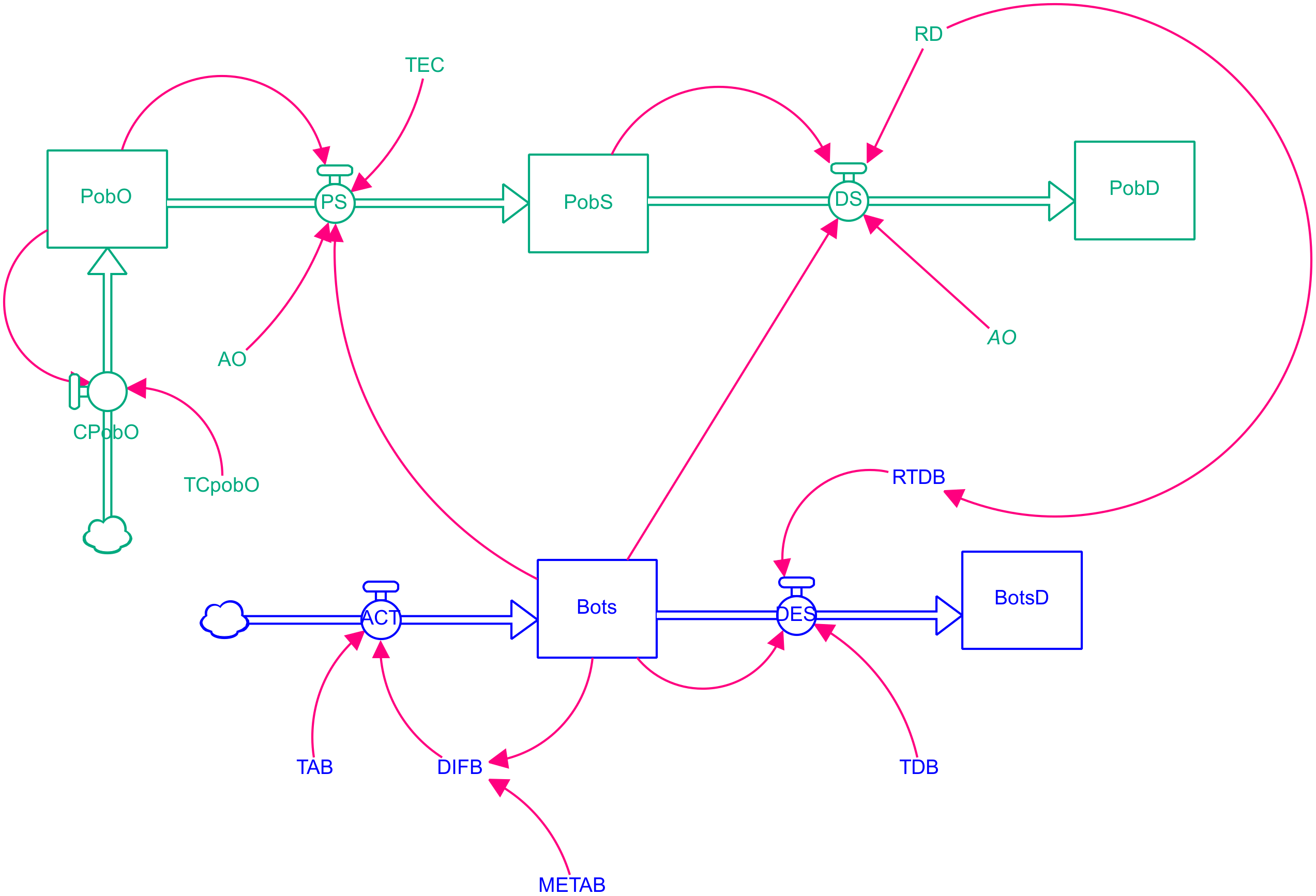

2. Theoretical Framework and Dynamic Model

2.1. What Are the Bots?

- Smoke screening: bots use context-related hashtags on social networks to distract online users from the main point of debate in a discussion.

- Misdirecting: the use of hashtags related to the topic of discussion to talk about other non-corresponding plots to divert the attention of the target audience from the disinformation.

- Astroturfing: the bot tries to influence public opinion, e.g., in a political debate, by creating the impression that a large majority is in favour of a certain position.

2.2. Disinformation, Bots and Causal Loop Diagrams

3. Methodology

- Construction of the flow diagram and levels of the model: this corresponds to the physical structure of the system in a defined period and allows the generation of the model’s patterns. In this step, the variables that allow the system’s behaviour to be represented are defined.

- The writing of differential equations: they represent the causes and effects of the system and allow its operationalisation.

- Parameter estimation: they assign the values of the variables that make it possible to simulate and obtain the system’s behaviour. For the present work, this stage was based on multiple sources, especially the study developed by Himelein-Wachowiak et al. [15].

- The testing of the internal consistency of the model: this corresponds to the evaluation of the behaviours generated by the model and which, for the present case, is based on the theory exposed in Section 2.2.

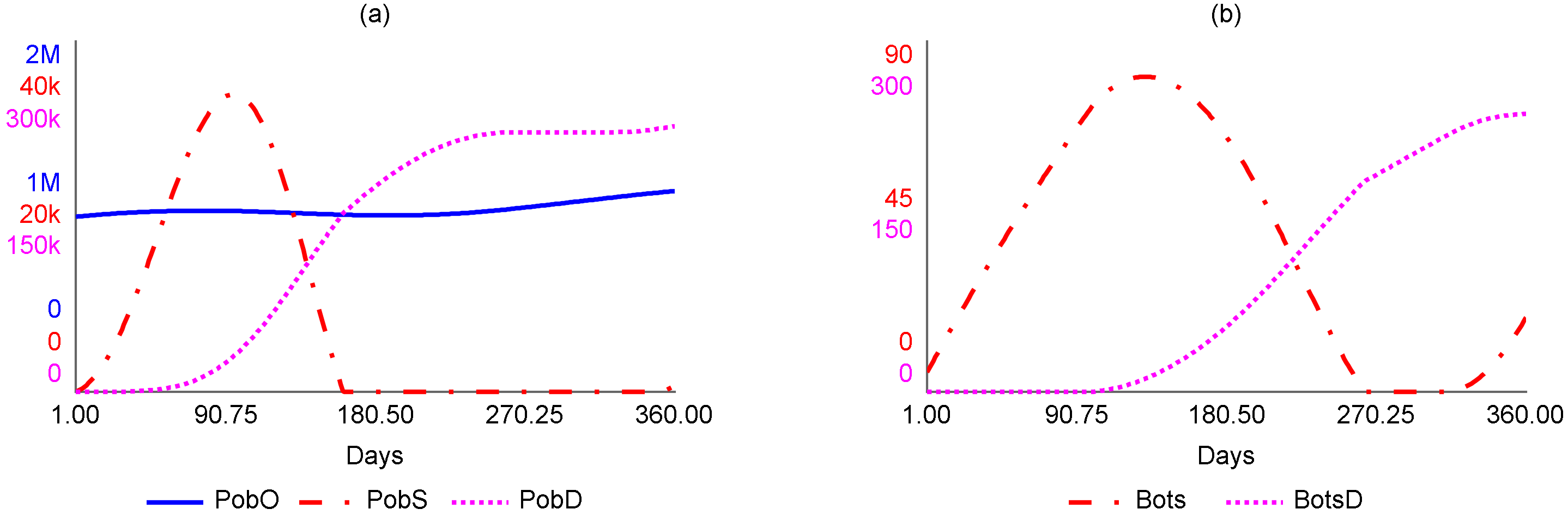

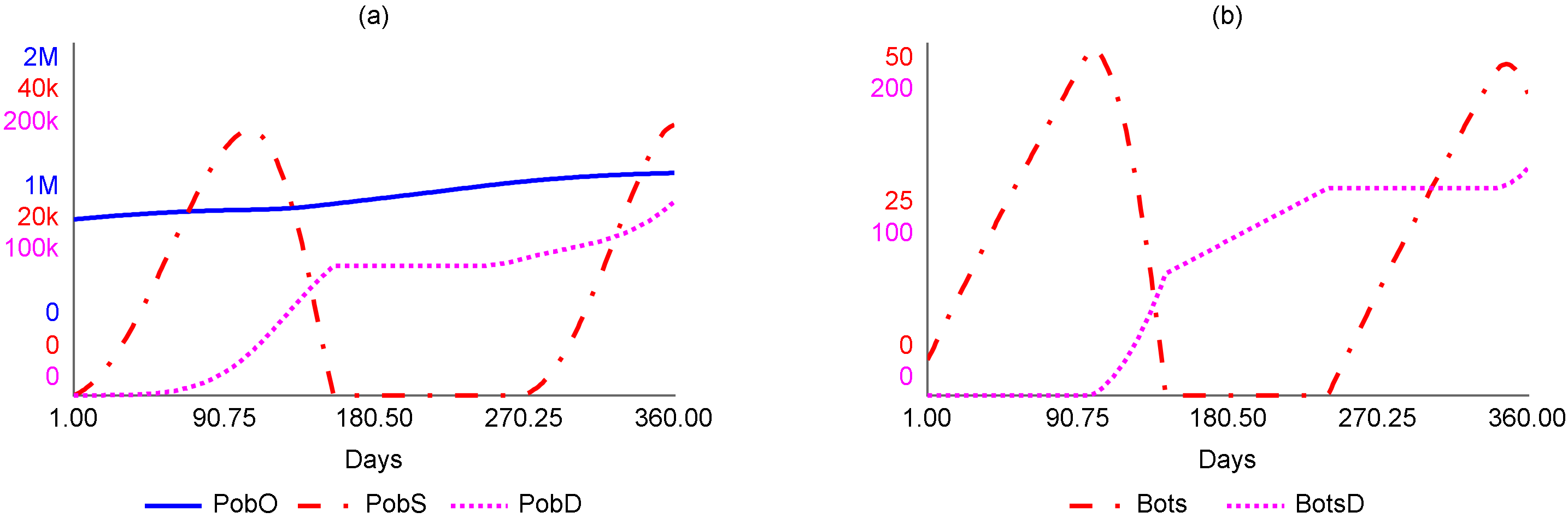

4. Results

4.1. Model

- Between the moment of the constitution of the population susceptible to disinformation (PobS) and the beginning of the spread of disinformation there is a delay.

- There is a limited number of bots that the disinformation agent wishes to place on the social network.

- The existence of a delay for the deactivation of bots.

4.2. Simulations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jussila, J.; Suominen, A.H.; Partanen, A.; Honkanen, T. Text Analysis Methods for Misinformation–Related Research on Finnish Language Twitter. Future Internet 2021, 13, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, A.; Rodríguez-Cánovas, B. Disinformation Propagation in Social Networks as a Diplomacy Strategy: Analysis from System Dynamics. JANUS. NET e-J. Int. Relat. 2021, 11, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.K.; Alsaeedi, F. Understanding and Fighting Disinformation and Fake News: Towards an Information Behavior Framework. Proc. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, e327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Cour, C. Theorising Digital Disinformation in International Relations. Int. Polit. 2020, 57, 704–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, T.; Benson, V. Spreading Disinformation on Facebook: Do Trust in Message Source, Risk Propensity, or Personality Affect the Organic Reach of “Fake News”? Soc. Media Soc. 2019, 5, 205630511988865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bjola, C. The Ethics of Countering Digital Propaganda. Ethics Int. Aff. 2018, 32, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrits, A.W.M. Disinformation in International Relations: How Important Is It? Secur. Hum. Rights 2018, 29, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bennett, W.L.; Livingston, S. The Disinformation Order: Disruptive Communication and the Decline of Democratic Institutions. Eur. J. Commun. 2018, 33, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Quiroz, J.; Iglesias-Osores, S. COVID-19: Desinformación en Redes Sociales. Rev. Cuerpo Med. HNAAA 2020, 13, 218–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, M.; Dyer, S. Information and Disinformation: Social Media in the COVID-19 Crisis. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2020, 27, 640–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, D.R. Medical Disinformation and the Unviable Nature of COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spradling, M.; Straub, J.; Strong, J. Protection from ‘Fake News’: The Need for Descriptive Factual Labeling for Online Content. Future Internet 2021, 13, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmstetter, S.; Paulheim, H. Collecting a Large Scale Dataset for Classifying Fake News Tweets Using Weak Supervision. Future Internet 2021, 13, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, K.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Alatawi, F.; Nazer, T.H.; Ding, K.; Karami, M.; Liu, H. Combating Disinformation in a Social Media Age. WIREs Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2020, 10, e1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himelein-Wachowiak, M.; Giorgi, S.; Devoto, A.; Rahman, M.; Ungar, L.; Schwartz, H.A.; Epstein, D.H.; Leggio, L.; Curtis, B. Bots and Misinformation Spread on Social Media: Implications for COVID-19. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e26933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samper-Escalante, L.D.; Loyola-González, O.; Monroy, R.; Medina-Pérez, M.A. Bot Datasets on Twitter: Analysis and Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawy, A.; Ferrara, E.; Lerman, K. Analyzing the Digital Traces of Political Manipulation: The 2016 Russian Interference Twitter Campaign. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM), Barcelona, Spain, 28–31 August 2018; pp. 258–265. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, F.; Wang, W.; Zhao, L.; Dougherty, E.; Cao, Y.; Lu, C.-T.; Ramakrishnan, N. Misinformation Propagation in the Age of Twitter. Computer 2014, 47, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Sasahara, K. Characterizing the Roles of Bots on Twitter during the COVID-19 Infodemic. J. Comput. Soc. Sci. 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanius, C.; Weber, R.; MacKenzie, W.I. Use of Bot and Content Flags to Limit the Spread of Misinformation among Social Networks: A Behavior and Attitude Survey. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2021, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Angarita, R.; Renna, I. Is This the Era of Misinformation yet: Combining Social Bots and Fake News to Deceive the Masses. In Proceedings of the Web Conference 2018—WWW ’18 Companion, Lyon, France, 23–27 April 2018; ACM Press: Lyon, France, 2018; pp. 1557–1561. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, A.G.; Surian, D.; Dalmazzo, J.; Rezazadegan, D.; Steffens, M.; Dyda, A.; Leask, J.; Coiera, E.; Dey, A.; Mandl, K.D. Limited Role of Bots in Spreading Vaccine-Critical Information Among Active Twitter Users in the United States: 2017–2019. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, S319–S325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, E.C. The Facts of Fake News: A Research Review. Sociol. Compass 2019, 13, e12724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazer, D.M.J.; Baum, M.A.; Benkler, Y.; Berinsky, A.J.; Greenhill, K.M.; Menczer, F.; Metzger, M.J.; Nyhan, B.; Pennycook, G.; Rothschild, D.; et al. The Science of Fake News. Science 2018, 359, 1094–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, C.; Ciampaglia, G.L.; Varol, O.; Yang, K.-C.; Flammini, A.; Menczer, F. The Spread of Low-Credibility Content by Social Bots. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vosoughi, S.; Roy, D.; Aral, S. The Spread of True and False News Online. Science 2018, 359, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, C.; Hui, P.-M.; Wang, L.; Jiang, X.; Flammini, A.; Menczer, F.; Ciampaglia, G.L. Anatomy of an Online Misinformation Network. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, M. Techniques of Disinformation: Constructing and Communicating “Soft Facts” after Terrorism. Br. J. Sociol. 2020, 71, 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.R. Fundamentos del Concepto de Desinformación Como Práctica Manipuladora en la Comunicación Política y Las Relaciones Internacionales. Hist. Comun. Soc. 2018, 23, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McGonagle, T. “Fake News”: False Fears or Real Concerns? Neth. Q. Hum. Rights 2017, 35, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallis, D. What is Disinformation? Libr. Trends 2015, 63, 401–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, K.; Varol, O.; Davis, C.A.; Ferrara, E.; Flammini, A.; Menczer, F. Arming the Public with Artificial Intelligence to Counter Social Bots. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Tech. 2019, 1, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rossmann, A.; Zimmermann, A.; Hertweck, D. The Impact of Chatbots on Customer Service Performance. In Advances in the Human Side of Service Engineering; Spohrer, J., Leitner, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1208, pp. 237–243. ISBN 9783030510565. [Google Scholar]

- Savage, S.; Monroy-Hernandez, A.; Höllerer, T. Botivist: Calling Volunteers to Action Using Online Bots. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, San Francisco, CA, USA, 27 February–2 March 2016; ACM: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 813–822. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, G. The Rise of Social Botnets: Attacks and Countermeasures. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2018, 15, 1068–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cresci, S.; Di Pietro, R.; Petrocchi, M.; Spognardi, A.; Tesconi, M. The Paradigm-Shift of Social Spambots: Evidence, Theories, and Tools for the Arms Race. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web Companion—WWW ’17 Companion, Perth, Australia, 3–7 April 2017; ACM Press: Perth, Australia, 2017; pp. 963–972. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, E.; Varol, O.; Davis, C.; Menczer, F.; Flammini, A. The Rise of Social Bots. Commun. ACM 2016, 59, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Academic Society for Managment and Communication. How Powerful Are Social Bots? Understanding the Types, Purposes and Impacts of Bots in Social Media. 2018. Available online: https://www.akademische-gesellschaft.com/fileadmin/webcontent/Publikationen/Communication_Snapshots/AGUK_CommunicationSnapshot_SocialBots_June2018.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Hollenbaugh, E.E.; Ferris, A.L. Facebook Self-Disclosure: Examining the Role of Traits, Social Cohesion, and Motives. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 30, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahng, M.R. Is Fake News the New Social Media Crisis? Examining the Public Evaluation of Crisis Management for Corporate Organizations Targeted in Fake News. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2021, 15, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzana, I.; Ferrara, E. Measuring Bot and Human Behavioral Dynamics. Front. Phys. 2020, 8, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kooti, F.; Moro, E.; Lerman, K. Twitter Session Analytics: Profiling Users’ Short-Term Behavioral Changes. In Social Informatics; Spiro, E., Ahn, Y.-Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 10047, pp. 71–86. ISBN 9783319478739. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, J. Dynamical Model about Rumor Spreading with Medium. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2013, 2013, 586867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rapoport, A.; Rebhun, L.I. On the Mathematical Theory of Rumor Spread. Bull. Math. Biophys. 1952, 14, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, L.; Huang, R. SIRaRu Rumor Spreading Model in Complex Networks. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2014, 398, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, Y.; Yan, X.; Jin, Z. Research on Knowledge Dissemination Model in the Multiplex Network with Enterprise Social Media and Offline Transmission Routes. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2022, 587, 126468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, B.K.; Arshad, F.M.; Noh, K.M. System Dynamics; Springer Texts in Business and Economics; Springer: Singapore, 2017; ISBN 9789811020438. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, C. Dynamic Performance Management. In System Dynamics for Performance Management; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 1, ISBN 9783319318448. [Google Scholar]

| Code | Simulation | Modified Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Sim—1 | Reference simulation | NA |

| Sim—2 | Increased activation rate | |

| Sim—3 | Increased deactivation rate | |

| Sim—4 | Beginning of disinformation |

| Variables | Conceptualización | Unidades | Parámetro Inicial |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target population: a population with specific characteristics that was defined by the agent to be susceptible to disinformation | People | 1,000,000 | |

| Susceptible population: the population that is subscribed to one of the disinformation agent’s accounts. | People | 0 | |

| Disinformed population: the population that visualised or had some contact with the disinforming message. | People | 0 | |

| Bots: number of bots in the social network used by the disinformation agent at a given time. | Bots | 5 | |

| Deactivated bots: corresponds to the number of bots that were deactivated by the algorithm or social network staff. | Bots | 0 | |

| Target population growth rate: is the ratio of growth of the population for a specified . | % | 0.1% | |

| Organic reach: percentage of publications viewed by the Bots through the distribution of the algorithm. This rate is defined according to the number of contacted. | % | GRAPH (TIME) (0, 0.0017), (10001, 0.0004), (100001, 0.00015), (300000, 0.00015), (400000, 0.00015), (500000, 0.00015), (600000, 0.00015), (700000, 0.00015), (800000, 0.00015), (1000000, 0.00015), (10000001, 0.00008) | |

| Effective contact rate: defined as the percentage of people who subscribe to the disinformation agent’s account. | % | 0.01% | |

| Disinformation delay: This corresponds to the initial at which message starts its propagation. This lag was developed by using the delay function. | Days | 90 | |

| Bot activation rate: the percentage of bots that are activated in each . | % | 50% | |

| Goal bots: number of bots that the uninformed agent wishes to have active. | Bots | 300 | |

| Bot deactivation rate: the percentage of bots that are deactivated by the social network at a given . | % | 1.973% | |

| Delay deactivation of bots: This corresponds to the initial at which the deactivation of the bots is initiated. This lag was developed by using the delay function | Days | 98 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guzmán Rincón, A.; Carrillo Barbosa, R.L.; Segovia-García, N.; Africano Franco, D.R. Disinformation in Social Networks and Bots: Simulated Scenarios of Its Spread from System Dynamics. Systems 2022, 10, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems10020034

Guzmán Rincón A, Carrillo Barbosa RL, Segovia-García N, Africano Franco DR. Disinformation in Social Networks and Bots: Simulated Scenarios of Its Spread from System Dynamics. Systems. 2022; 10(2):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems10020034

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuzmán Rincón, Alfredo, Ruby Lorena Carrillo Barbosa, Nuria Segovia-García, and David Ricardo Africano Franco. 2022. "Disinformation in Social Networks and Bots: Simulated Scenarios of Its Spread from System Dynamics" Systems 10, no. 2: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems10020034

APA StyleGuzmán Rincón, A., Carrillo Barbosa, R. L., Segovia-García, N., & Africano Franco, D. R. (2022). Disinformation in Social Networks and Bots: Simulated Scenarios of Its Spread from System Dynamics. Systems, 10(2), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems10020034