Abstract

Globalization and urbanization have reshaped the way that service ecosystem subjects interact with each other in rural communities, providing conditions and possibilities for realizing value co-creation in rural communities. Therefore, this study selected rural communities in Guiyang City, China, as research subjects and explored the value co-creation mechanism in rural communities from the perspective of service ecosystems. The authors construct a theoretical framework encompassing “value co-creation conditions, value co-creation processes, and value co-creation results”. The study found that the core mechanism in the process of value co-creation is “subject embedding, relationship interaction, and resource integration”. At the macro level, resource sharing is achieved through complex and heterogeneous interactions among multiple subjects, under the influence of institutions, policies, and cultures. At the meso level, organizations complement each other’s resources through the cooperation and empowerment of other actors horizontally, under the influence of structure, function, and rules. At the micro level, individuals optimize resources through cooperative and empowering interactions, under the influence of motivations and value preferences. Finally, the integration of individual, organizational, and overall values constitutes public values, under the joint cross-level action of institutional and cultural elements. This study provides a new theoretical perspective for exploring the value co-creation mechanism in rural communities and provides important practical insights for promoting the sustainable development of rural communities.

1. Introduction

Rural governance is both the basis for rural revitalization and the cornerstone of national governance [1]. China has been an agriculture-based country since ancient times, and the countryside is not only the bearer of the rural economy and farmers’ lives but also the soil for the inheritance and development of Chinese culture. However, under the influence of globalization, industrialization, and urbanization, the structure of rural communities has changed, with rural communities showing a trend towards hollowing out, ageing, and marginalization [2]. As a result, there are still major differences between rural and urban areas, in terms of grassroots organizational capacity and the development of community organizations, and it is not yet possible to replicate the urban model of community organization and development. Currently, China’s rural areas mainly rely on two paths: exogenous development by the government and enterprises, and endogenous development by developing rural human resources [3]. On the one hand, government-led rural construction has achieved remarkable results in improving infrastructure and the ecological environment. However, government-led rural development may suffer from government failure due to factors such as villagers “free-riding” and inefficient policy implementation, which may result in a loss of equity and efficiency [4]. Therefore, it is difficult to solve the problem of rural revitalization by relying solely on government leadership. On the other hand, with the relevant policies tilted towards rural areas, some enterprise capital is pouring into rural areas on a large scale. Some scholars argue that the involvement of foreign capital in rural construction can create employment opportunities for local villagers, optimize the structure of rural industries, revive traditional villages, and improve rural governance [5,6]. However, enterprises are prone to social conflicts, power games, and conflicts of interest during their interactions with local villagers, which may result in a waste of resources and social instability [4]. It can be seen that the government- and enterprise-led model of rural construction has triggered controversy, and how to give full play to the villagers’ role as the mainstay of rural revitalization has then aroused extensive discussion in the academic communities. In rural areas, most villagers have difficulties in participating in rural construction due to their low level of education and poor labor skills, which results in a lack of a sense of gain and happiness. Rural construction, led by rural elites with certain technical and resource advantages, may capture financial and policy support, resulting in the phenomenon of “elite capture” [7]. Hence, in the practice of rural governance, there is an urgent need to explore a new path for the integration and development of key stakeholders to harmonize the relationship between various subjects.

Value co-creation from the perspective of service ecosystems focuses on the dynamic process of relational interactions between subjects at different levels, and the integration of heterogeneous resources [8]. In rural construction, value co-creation can play a role in accurately grasping the service demands so that different subjects can participate in the planning and management of rural construction, thus forming closer community networks and cooperative relationships [9]. Through interaction and resource integration, the subjects can promote the efficient use of resources, reduce rural burdens, and enhance community cohesion and their capacity for self-development [10]. The conditions and possibilities for promoting rural revitalization can only be provided if different subjects work together, deepen the linkage of interests for value co-creation, and realize value sharing from micro to macro [11]. Thus, based on existing studies, this study selected the typical rural communities in Guiyang City, China, as a case study from the perspective of service ecosystems, and tried to explore the following core questions: How does the value co-creation mechanism of a rural community take shape? What factors influence it? What kinds of value co-creation results have been realized? Based on the above questions, the authors first collected data through field research using semi-structured interviews. The authors then coded the data using Nvivo 12 software and found the logic between the elements based on the coding. Next, the authors used the proceduralized grounded theory (PGT) method to construct and test a model of rural communities’ value co-creation mechanism. Finally, the authors optimized the rural community value co-creation mechanism model and proposed its realization path. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

First, the authors constructed a model of rural communities’ value co-creation mechanism from the service ecosystem theory and conducted an exploratory study, which, to a certain extent, filled the theoretical gap caused by insufficient contextual considerations in the existing literature. Second, the authors further optimized the mechanism model of value co-creation in rural communities and purposed the realization path of value co-creation in rural communities from the perspective of service ecosystems, which was conducive to the evidence and enrichment of the mechanism model, and to a certain extent, provided new ideas for promoting rural revitalization.

2. Literature Review

Value co-creation, as a new type of value creation model, is different from the previous closed and isolated traditional public service model that over-pursues the internal efficiency of the organization and ignores the external efficiency. Value co-creation has already had a wide impact in the fields of enterprise marketing and sharing economy and has shown strong contextual applicability and theoretical extensibility. Value co-creation, which first appeared in the business field, refers to the idea that private sector service recipients will provide feedback to the company when they participate in production practices, and then the company’s production will be optimized, thus creating a sound service ecosystem [12,13]. Through market-oriented reforms, private sector management experience has been introduced into the public sector in large numbers, and the value co-creation that sprouted in the private sector has been extended to the public service at the same time, which has become an important mechanism for explaining public value creation within the public service system [14]. Scholars are continuously developing boundaries of theoretical research on value co-creation mechanisms. According to the existing literature, the theoretical perspectives on value co-creation mechanisms can be broadly categorized into service-dominant logic, practice, social exchange, and stakeholder theories. First, the service-dominant logic is the foundational theory for the conceptualization of value co-creation, which was originally proposed by Vargo and Lusch, who argued that the roles of the business and the customer in the value creation mechanism are intertwined rather than separate and distinct [15,16,17]. The service-dominant logic theory emphasizes that value is always co-created by the business and the customer, and that value is only realized when the customer uses the service [18]. Businesses as service providers not only provide a value proposition, but also help customers realize that value by interacting with them, and this direct interaction is the key to value co-creation [19]. Businesses focus on using operational resources, such as knowledge and skills, to engage customers in the value co-creation process [20]. Given the theory’s role in the origin of the concept of value co-creation, many studies have used service-dominant logic as the theoretical basis to explain value co-creation mechanisms [21]. However, some scholars have argued that, for the practice studies of subjects in value co-creation mechanisms, practice theory explains their views in more detail, and that the practices adopted by the subjects in the co-creation mechanisms influence the interactions between the subjects, which determines the intensity of the value co-creation process [22]. Individuals’ practical actions affect the relationships in which they interact with others [23]. When investigating the interaction of subjects in value co-creation, social exchange theory suggests that individuals will interact only if their subjective assessment of perceived benefits exceeds their subjective assessment of perceived costs [24,25]. In the process of an individual’s interaction with a service provider, appropriate rewards are expected, which can be material rewards, moral rewards, or even experiences from the relational interaction itself [26], due to the fact that the main purpose of the value co-creation mechanism is to maximize the value created by the participating subjects [27]. Therefore, more scholars have studied the dichotomous relationship between service providers and customers in the process of value co-creation from the perspective of stakeholders [28]. The stakeholder theory suggests that the actions taken by an organization affect the interests of its stakeholders, so the organization needs to build a strong relationship with its stakeholders to avoid affecting the performance of the business [29].

Previous studies have provided some theoretical perspectives on the mechanisms of value co-creation. However, the existing studies are only applicable to explaining value co-creation mechanisms in a specific context. For example, the social exchange theory is the most appropriate theory for assessing the costs and benefits of the subjects involved in the value co-creation process. The theory of practice is the most relevant theoretical perspective when more emphasis is placed on the specific actions adopted by subjects in the process of value co-creation. However, if we want to research the resource integration between subjects, then none of the existing theories can adequately explain this view. Thus, we take the service ecosystem, which is a theory derived from the service-dominant logic, as the main perspective to study the value co-creation mechanism among subjects in rural areas. Although some scholars have carried out some studies on value co-creation mechanisms from the perspective of service ecosystems, most of them have focused on urban areas, while studies on value co-creation mechanisms in rural areas are not yet in-depth and systematic. Service ecosystems exceed the scope of interactions between service systems under other theoretical perspectives and highlight multilevel resource interactions under complex network systems [8]. Firstly, value co-creation mechanisms in contexts specific in rural areas need to be analyzed and refined at different levels. Secondly, the ways in which resource integration is achieved through relationship interactions between subjects at different levels in rural communities need to be further explained. Finally, the characteristics of resource integration in rural areas at different levels and the influence of the core facilitators at different levels on the behaviors of the subjects must be explored in depth. Overall, the studies on value co-creation in rural areas from the service ecosystem perspective are fragmented and lack a systematic theoretical analytical framework.

3. Theoretical Foundation and Framework Construction

3.1. Service Ecosystems

The concept of service ecosystems, developed from business ecosystems and innovation ecosystems, refers to the spatial–temporal structure in which socio-economic actors with different value propositions interact through institutions, technologies, and languages to provide services and co-create value [8,30]. The service ecosystem theory takes over the research method of ecosystems and emphasizes the cross-level interaction structures of macro, meso, and micro levels [31]. As shown in Table 1, firstly, the macro level focuses on the interaction of all social subjects, which influences the meso and micro services, and the three levels work together in the whole service ecosystem by coordinating, informing, and collaborating with each other, thus generating opportunities for service innovations and improving the sustainability of services [32]. Lusch and Vargo emphasized that institutions are a key feature of service ecosystems that act at the macro, meso, and micro levels of service ecosystems. Sharing systems can play a facilitating and constraining role while affecting resource integration and value creation among subjects [20]. In addition, Vargo and Akaka pointed out that the subjects are linked to the internal and external service systems through resource integration and institutions, and that the subjects are centered on resource integration and co-create value through the interaction of technology and institutions within the service ecosystem [33]. Secondly, the meso level focuses on the interaction between different organizations [34]. Institutions play a coordinating role at the meso level, where digital technologies and institutions work together to facilitate the effective integration of resources between different organizations and improve the efficiency of resource utilization [11]. Then, the organizations achieve increased organizational value by aligning mutual interests and sharing resources [35]. Thirdly, at the micro level, Frow et al. stated that the individual should be the center of the study, focusing on the dichotomous activities between enterprises and customers [36]. Institutions are critical in service ecosystems because they provide guidelines for interactions between subjects [37]. Subjects are embedded in the ongoing replication of existing institutional arrangements, realize feedback loops through interrelated reflexivity and reform, and consciously shape institutional arrangements to facilitate intentional changes in the service system [38]. Individuals use their own skills, experience, and knowledge to integrate with new resources to realize personal value [39].

Table 1.

Research on service ecosystems at different levels.

Previous research on service ecosystems by scholars have provided us with certain analytical ideas. First, since China’s reform and opening up, the transformation of the rural social structure has led to an increasing diversification of villagers’ public service demands [40]. Relying on a single subject alone has insurmountable limitations in terms of resources and services [41]. Therefore, subjects can improve the effectiveness of service provision by integrating their existing resources with those possessed by other subjects. Second, by utilizing digital technologies, subjects can facilitate the sharing and transfer of information inside and outside of rural communities and improve subjects’ understanding of and participation in services. Finally, considering the interactions between subjects and resource integration from the perspective of macro, meso, and micro level interactions in the service ecosystem is conducive to a deeper analysis of the value co-creation mechanism in rural communities.

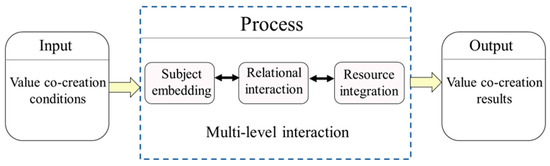

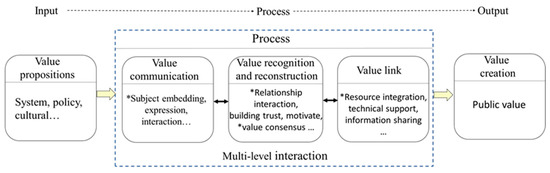

3.2. Theoretical Framework Construction

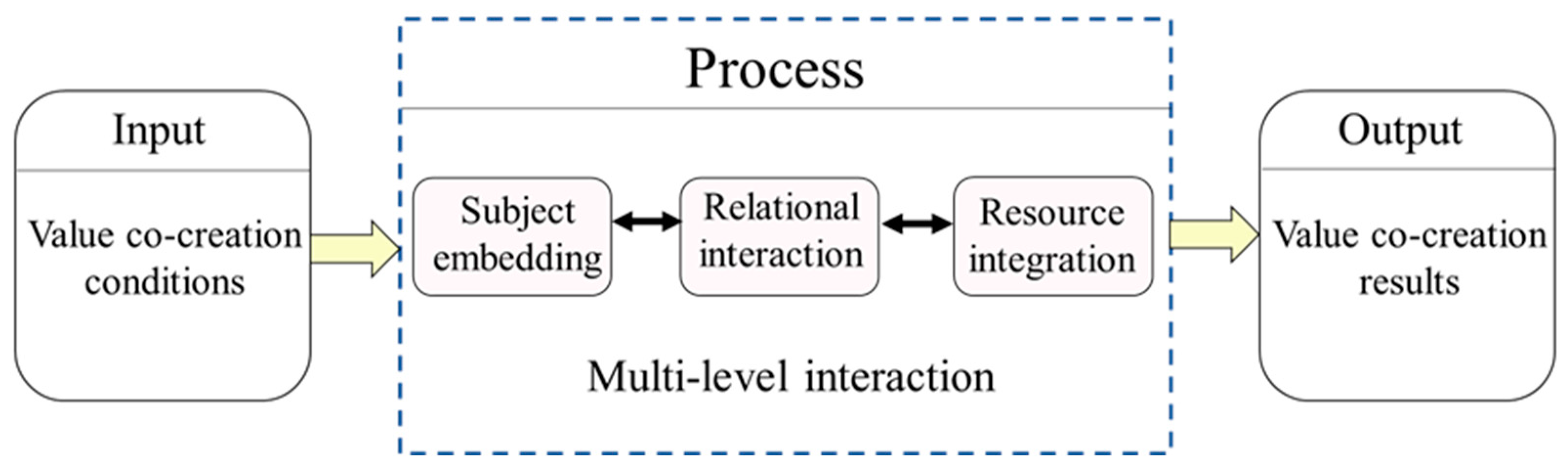

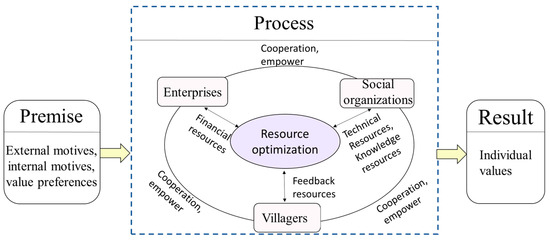

The authors utilized the “Input-Process-Output” IPO theoretical model proposed by Marks, to construct the value co-creation framework under the service ecosystem [42]. First, as important conditions in service ecosystems, institutions, technologies, and cultures provide the basis for the construction, operation, and governance of the system, and influence the realization of individual and systemic value co-creation goals [20,43]. Among them, the value co-creation process is the key link to revealing the value co-creation mechanism, involving the three core elements of subject embedding, interaction, and resource integration, which interact with each other [11]. Specifically, the construction of service ecosystems requires the embedding of different subjects and clarification of their interactions, which can create value in organizing and allocating resources based on specific services [44]. Finally, the authors need to distinguish value outcomes from value creation processes to accurately assess value outcomes [45]. Thus, the authors constructed a framework for value co-creation from the perspective of service ecosystems, with a view to providing a reference for the generation of the mechanism model that follows, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

An evolutionary framework for value co-creation from a service ecosystem perspective.

4. Research Method and Data Sources

4.1. Research Methods

The Wenggong and Gumeng villages have been the research bases of the authors for one and a half years. During these long-term research activities, the authors have built up a good relationship with the villagers, village cadres, and other subjects. The field research for this research topic lasted from March 2022 to August 2023 and was divided into three main phases. In the first phase, from March to April 2022, we collected relevant fieldwork information by randomly visiting the two villages to obtain a general idea of the situation. In the second stage, from October to November 2022, based on the relevant data obtained from the field survey, we selected the interviewees related to the “co-creation” of the two villages (Table 2) and designed the corresponding interview outline (Table 3). With the consent of the interviewees, semi-structured interviews of about 80 min each were conducted according to the outline, and written notes were taken. We learned about the specifics of village development from the perspectives of multiple subjects and their actual perceptions of village development. All data acquisition was explained to the interviewees in advance with their consent and indicated that it was for scientific research needs. In the third phase, from April to August 2023, we visited the villages again with an interview outline developed around the proposed responses to village development, so that we could understand the limitations and challenges of village development in terms of the recommendations and analyze the issues and responses that affect the process of value co-creation in rural communities. The purpose of the second and third phases of data collection was to go deeper into the subject of the study and collect more detailed data to supplement the theoretical model and further enhance the research credibility.

Table 2.

Rural community value co-creation interview outline.

Table 3.

Personal information of respondents in primary data. Note: Code W/G stands for Wenggong Village/Gumeng Village. Code W/M stands for female/male and the code represents the serial number of the respondent.

The survey was conducted in three ways: in-depth interviews, focus group interviews, and participant observation. First, in-depth interviews were based on face-to-face interviews. The interviewees included village committee cadres, social organization managers, villagers, entrepreneurs, and other subjects, totaling 15 people. Secondly, the focus groups were organized in two forms: formal and informal focus groups. Formal focus groups invited village committee members and some village representatives to conduct group talks, which were held twice in total. Informal focus groups were conducted mainly in the context of villagers’ recreational activities. Although it was inevitable that the topic of conversation would be discrete during the recreational activities, we always focused on the process of “co-creation” of the village. Finally, participatory observation also included two forms. The first form involved participation in the process of interaction between villagers, social organizations, enterprises, and village committees. We acted as observers to understand the key processes of their interaction. The second form was to accompany a villager who was dissatisfied with the allocation of resources to the village committee, in which we witnessed the specific ways in which the village committee acted.

Owing to the authors’ long-term research experience in Wenggong and Gumeng villages, the information used in this study is not limited to the field research in the two villages, and some relevant information from previous years is also utilized to form a be-fore-and-after analysis with the current information.

4.2. Data Selection

The authors selected the cases following the principle of theoretical sampling, and compared and analyzed the cases to identify similarities and heterogeneities in the units being analyzed, thus providing a good basis for theory construction [46]. The authors have the following main bases for selecting Wenggong and Gumeng villages in Guiyang City, China, as the research object: first, based on the dimensions of division and integration and natural–social–historical conditions, both cases belong to villages with low social differentiation and strong self-integration in China [47]. The existence of these villages is characterized by “living by the mountains”. Unlike other plains, these villages are located in marginal areas amidst high mountains, with less interaction with the core area, and are relatively closed. Moreover, these areas are far from political centers, with poorer natural conditions and slower civilization development, and have unique natural, social, cultural, and political patterns. Second, characteristic matching; the cooperation and collectivity of villages with low social differentiation and strong self-integration stems mainly from the intrinsic dynamic mechanism. In these villages, it is easier to agree on the collectivity of villagers’ self-identification; thus, the villages can carry out effective self-governance [47]. Despite the differences in the specific practices of the two selected cases, there is a wide range of collaborative exchanges among multiple subjects and cross-organizational, cross-sectoral, and cross-industry characteristics in both of them. Third, representativeness; Wenggong Village is a national model base for ethnic co-creation (a platform set up by a specific community to promote exchanges, integration, and shared development among different ethnic groups), while Gumeng Village is the first rural community to implement the “village stewardship” governance model successfully. Finally, both cases are in Guiyang City and share the same policy context at the municipal level, which suggests that the common parts embodied in these two selected cases are typical under similar institutional environments.

Next, the authors give a brief description of the two cases. Wenggong Village has a deep history of intangible ethnic culture; firstly, it is led by the village committees and supported by enterprises, through social organizations that finance the craftsmen who stay in the villages and empower the ethnic minority women’s groups who are based in traditional culture. Secondly, social organizations set up public numbers through Internet technology and publish relevant information on their official websites to disseminate the traditional culture of village ethnic minorities to society. Thirdly, social organizations have carried out basic research in cooperation with major colleges in order to complete projects with village committees or enterprises on the transmission and preservation of their intangible cultural heritage, organized training activities in cooperation with other organizations, and established a folk museum platform that can be linked to multiple subjects. Nowadays, Wenggong village has driven the surrounding villagers to establish a sense of cultural identity. At the same time, with the cultural workshop as the center, it has radiated the surrounding villages, has used cultural tourism to alleviate poverty as a means to drive the development of a family economy based on non-heritage ethnic minority cultures, and has led to the revitalization of the surrounding villages and the renaissance of traditional handicrafts.

In Gumeng village, first of all, to change the appearance of the village, the village committees have introduced relevant governance policies and set up a “village steward” social organization. So far, the village stewards have organized and carried out more than 10 times of centralized environmental improvement, and the village’s garbage and construction materials, etc., have been comprehensively cleaned up. The village committee director (GM6) said: “We have realized the market-oriented operation of domestic garbage collection and transportation through bidding, and established a small micro-power sewage treatment system, which has effectively solved the problem of villagers’ domestic garbage and sewage treatment”. Secondly, as a traditional agricultural village, Gumeng village has in recent years established a 600-acre orchard planting base on the unused land of the villagers through the model of “village committees + village stewards + villagers”. To ensure the smooth development of the industry, the village committees have gone out to visit and consult with agricultural experts many times to reduce the market risk. Thirdly, to publicize local industrial characteristics, Gumeng village has held exhibitions and sales activities to give enterprises and institution workers a more intuitive understanding of local agricultural and sideline products, and to help revitalize the countryside through practical actions. In addition, Gumeng village has set up a “platform to help farmers sell”, realizing online and offline “double line” to help sell agricultural products, helping farmers broaden sales channels, attracting many consumers and visitors. Today, the village receives more than 20,000 visitors annually, which directly or indirectly drives the employment of more than 4000 people.

4.3. Data Collection

The authors mainly used the semi-structured interview method and the participatory observation method to collect primary data. First, the authors observed interactions between different subjects, forming an observation record of about 5100 words and an interview record of about 98,000 words. Secondly, the collection of secondary data was mainly undertaken by searching relevant public numbers, policy documents released on the website of the organization’s page, various types of news reports, and other publicly available information; this process only selected secondary data related to the research topic. The details are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Collection of secondary information.

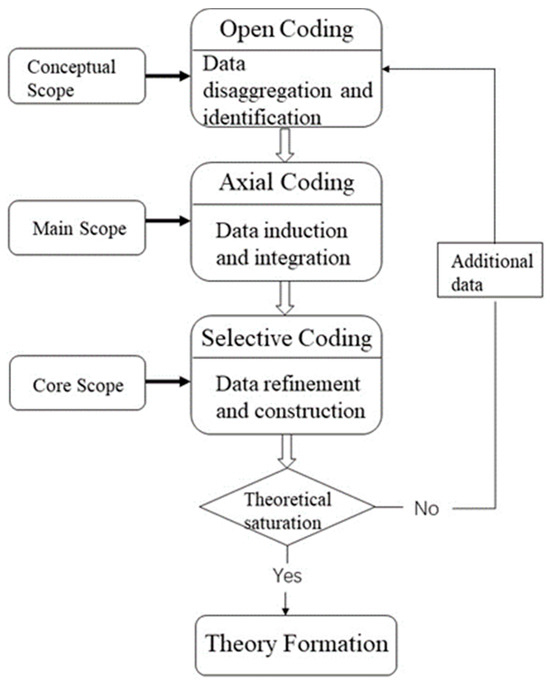

Through the organization and analysis of primary and secondary data, about 110,000 words of textual materials were obtained. Among them, about 2/3 of the materials were randomly selected for third-level coding and model construction, while the remaining data were used to test model saturation. Then, the authors used Nvivo12 software to process the data through coding, which is the process of defining the content of the data, including three steps: open coding, axial coding, and selective coding [48].

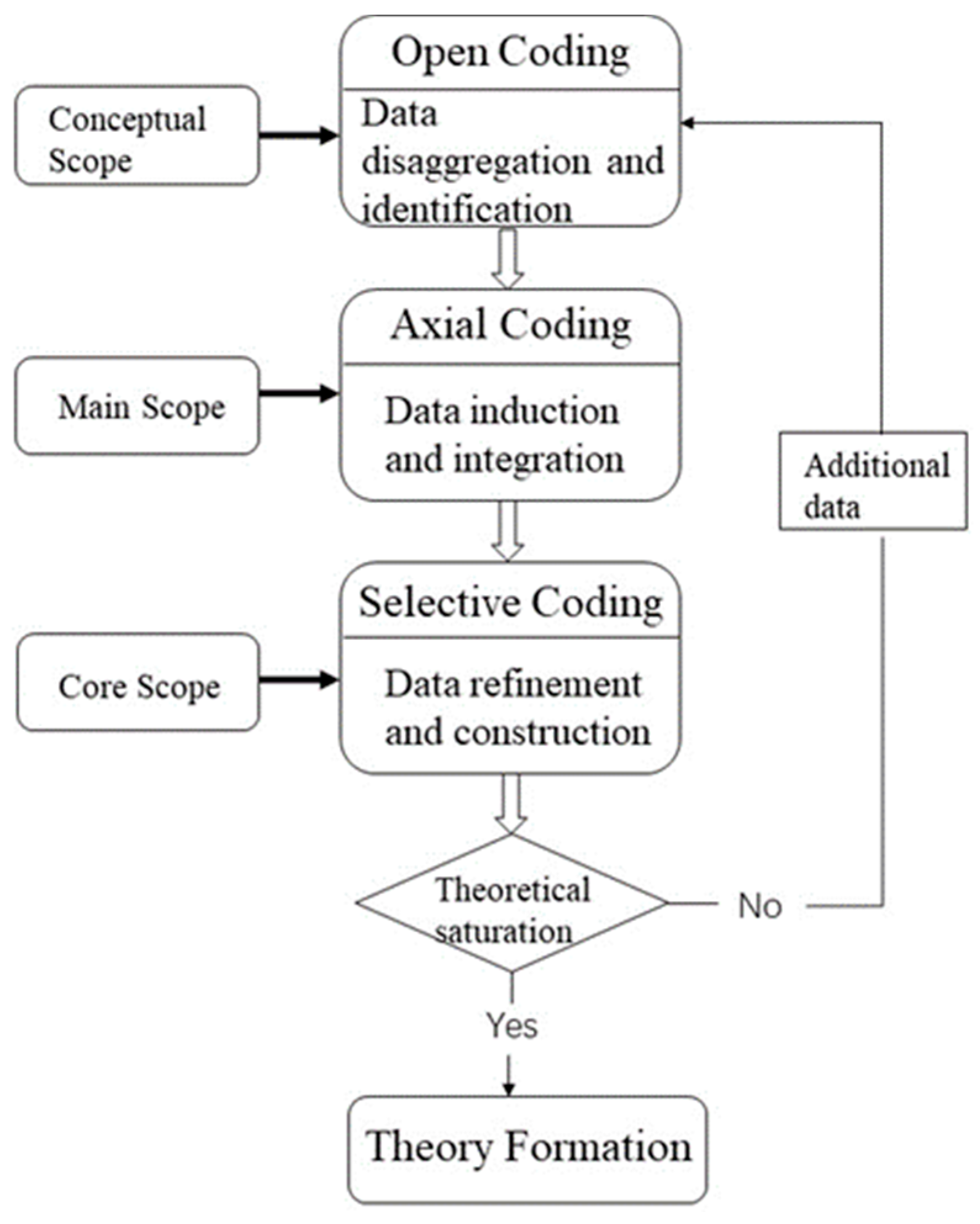

Grounded theory is a qualitative research approach that aims to continuously distill and summarize the core concepts from empirical materials from the bottom up, and then establish the links between each concept to expose the complex relationships and operations behind the practice [49]. Through continuous evolution and development, different divisions of grounded theory have emerged. Among these, constructive grounded theory (CGT) and PGT have been often used. The PGT approach was selected in this study for the following reasons: first, it is exploratory for the study of value co-creation mechanisms in rural communities from the perspective of the service ecosystem. As a realistic path to promoting sustainable rural development, there is no mature theory to explain and illustrate its logic; therefore, this study is not suitable for top-down research thinking. Second, the practice of value co-creation in rural communities involves multiple subjects and complex behaviors, which makes it more suitable for scientific and easy-to-use analytical methods such as PGT. Thirdly, analyzing the data through three-level coding is more likely to reveal the deeper logical patterns of the research phenomenon. The specific research steps are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Proceduralized grounded theory methodology process.

5. Coding Analysis and Model Construction

5.1. Open Coding

Open coding is the process of analyzing the collected information in detail, extracting the keywords and connotations, and conceptualizing them [50]. During the coding process, the authors tried to use canonical words related to this study, words summarized through internal logic, and proper nouns mentioned in the references. Then, the authors kept digging deeper and deeper into the conceptual connotations in the sources and analyzed them repeatedly to come up with more substantial subcategories. The authors removed the concepts that appeared less than three times in the coding and did not fit the study. Finally, a total of 28 subcategories were analyzed and refined. Due to the large space occupied and the fact that the categorization can come from multiple reference statements, the authors have only listed some of the open coding contents and initial statements, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Open coding content.

5.2. Axial Coding

The process of axial coding is to analyze, refine, sample, and merge the subcategories obtained from the open coding to obtain the main categories [51]. The authors analyzed the intrinsic relationship between the categories through the typical logic of “causal condition–phenomenon–vein–mediating condition–action strategy–result” in the grounded theory and then extracted the main categories. It should be noted that subcategories, such as “multilevel interaction”, which is an outcome, may also be a condition for the occurrence of other main categories. Finally, the authors have summarized the 28 subcategories into five main categories, “value proposition, value communication, value recognition and reconstruction, value link, and value creation”, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Axial coding content.

5.3. Selective Coding

Selective coding is the process of further coding the main categories to extract a core category that covers all the main categories and uses storylines to form a complete explanatory framework [52]. The authors chose the IPO theoretical framework for selective coding because of the clear storyline of this study. The authors compared and verified the main categories, carefully analyzed other categories, and extracted “rural community service ecosystem” as the core category. The main category relationships are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Main category relationships.

In summary, the storyline of the case can be summarized as follows: first, to promote rural construction, village committees formulate a variety of relevant rules, regulations, and welfare policies, and give legitimacy to the participation of social organizations in the governance of rural communities to achieve the administrative absorption of the community using administrative contracting and other means. Secondly, after receiving the mission signals, social organizations cooperate horizontally with other organizations, enterprises, colleges and universities, and other subjects to accomplish the mission and strengthen their construction. In the process of cooperation, social organizations constantly interact and communicate their values with other subjects. Third, with the support of Internet technology, social organizations gradually obtain the trust of the public and other subjects by publicizing their governance objectives and disclosing information. Subsequently, in community activities, the subjects realize value recognition and reconstruction through information sharing and service exchange. Timely communication, fair monitoring, and distribution mechanisms avoid the phenomenon of value co-destruction due to conflicts of interest among subjects, thus enabling them to reach value consensus. Fourth, the value consensus promotes the value link between subjects and realizes the effective integration and matching of resources. Ultimately, in the process of multi-layer interaction, integrating different values constitutes public value. Public value plays a supervisory and regulatory role in the behavior of the subject, which in turn promotes the rural community ecosystem to generate new public values, thus forming a sustainable rural community service ecosystem.

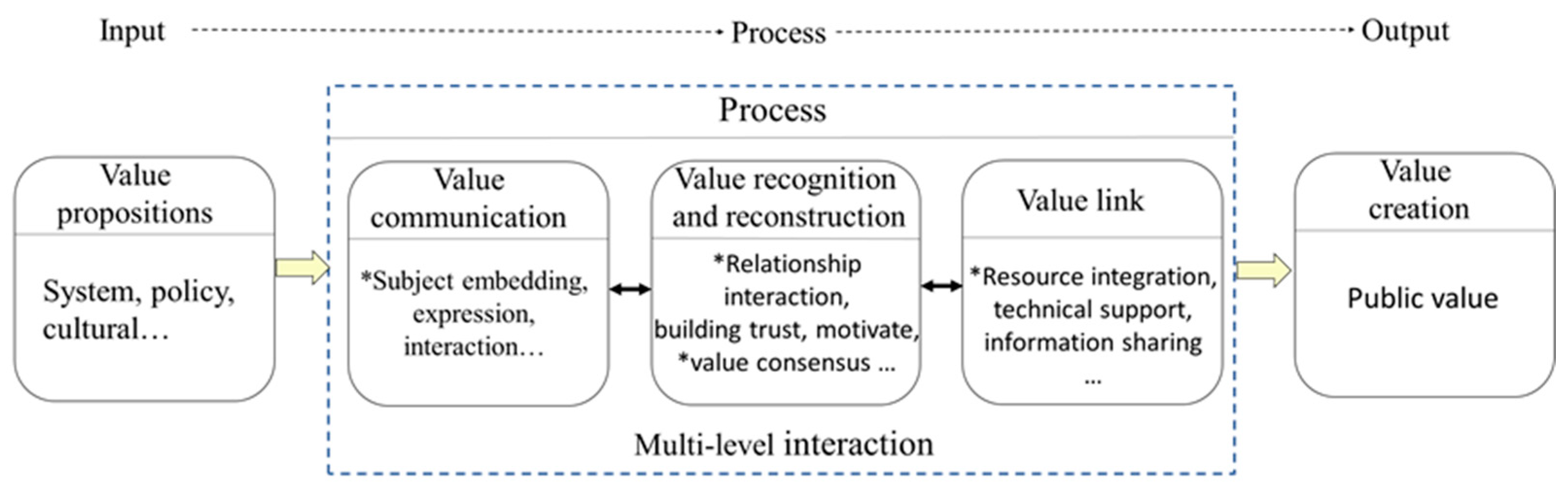

5.4. Model Construction

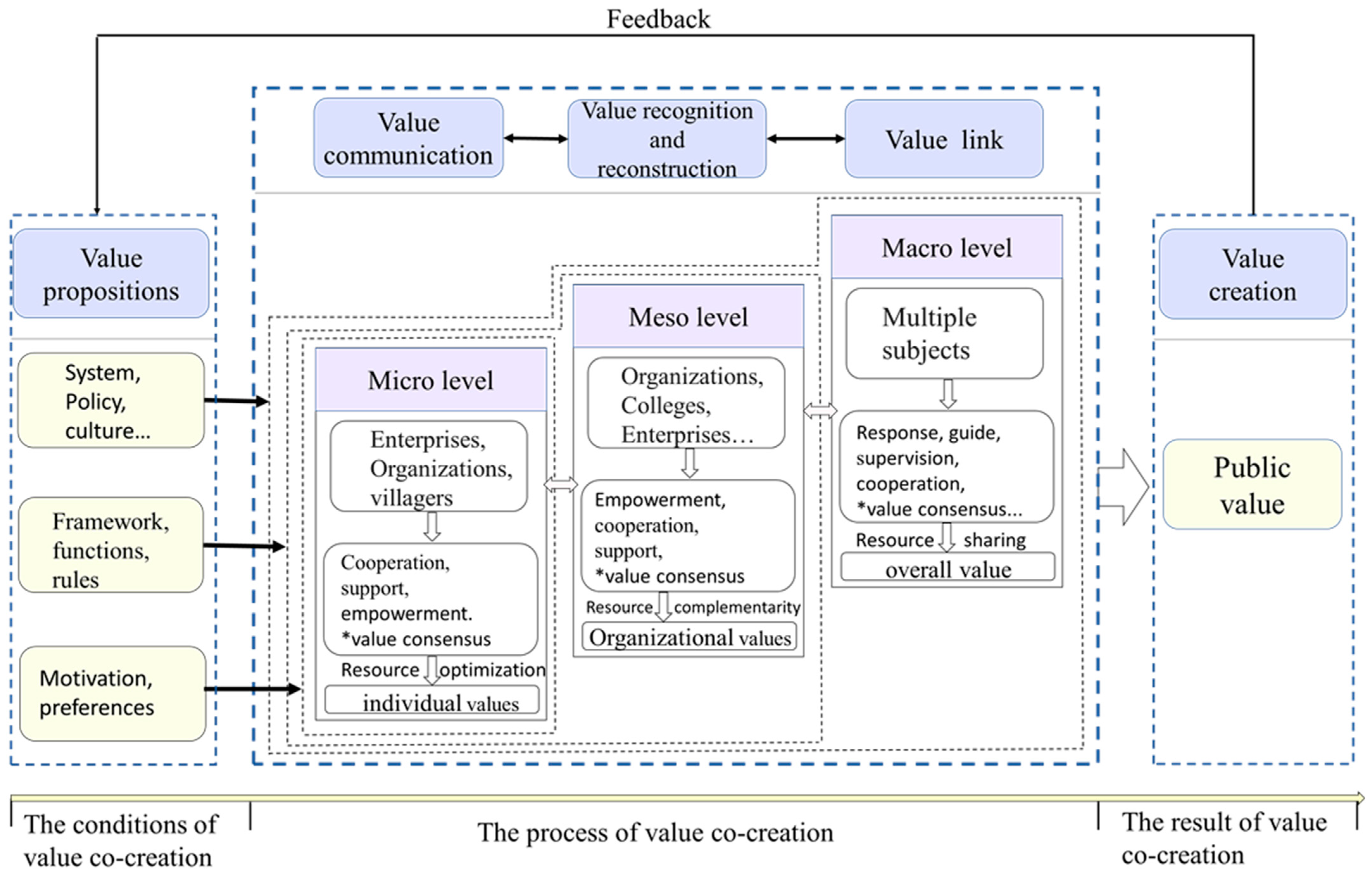

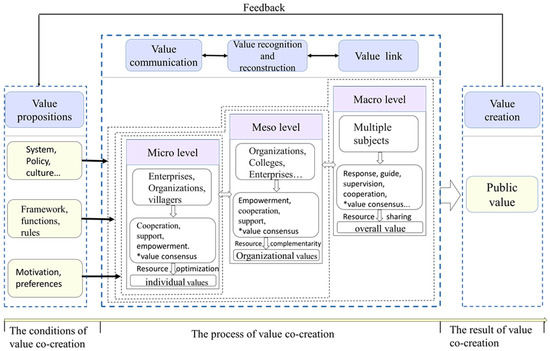

The authors continuously analyze the subcategories and main categories of the phenomenon of value co-creation in rural communities through the PGT method, and clearly explain its storyline, identify the relationship between the categories, and construct a model of the mechanism of value co-creation in rural communities under the IPO framework, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A mechanism model for value co-creation in rural communities. Note: * represents key elements.

5.5. Coding Results Test

For the reliability and validity test of coding, first, the authors fully integrated the group members’ opinions in the generalization and organization of the primary and secondary categories during coding, to form a correct and true response dimension to the real situation in the case. Second, the authors explored uncertain textual content during the coding process to ensure the reliability and consistency of the coding results.

The theory saturation test means that the theory is saturated when no new categories and ideas can be derived from the data collected [49]. Before starting the coding exercise, the authors reserved a portion of the collected data for determining the emergence of new attributes after the coding was completed. Based on this, the authors coded and analyzed the remaining primary and secondary data, and the resulting categories could still be included in the five main categories. Therefore, our model of value co-creation mechanisms in rural communities reached theoretical saturation.

6. Model Analysis

The authors derived a model of value co-creation mechanism in rural communities after three-level coding using the PGT method. Next, as recommended by Chandler and Vargo, the authors discuss the value co-creation in rural communities in this study at the macro, meso, and micro levels [43], and explore the mechanisms at each level under the framework of “value co-creation conditions–value co-creation process–value co-creation results” to construct a path for realizing the mechanism of value co-creation in rural communities.

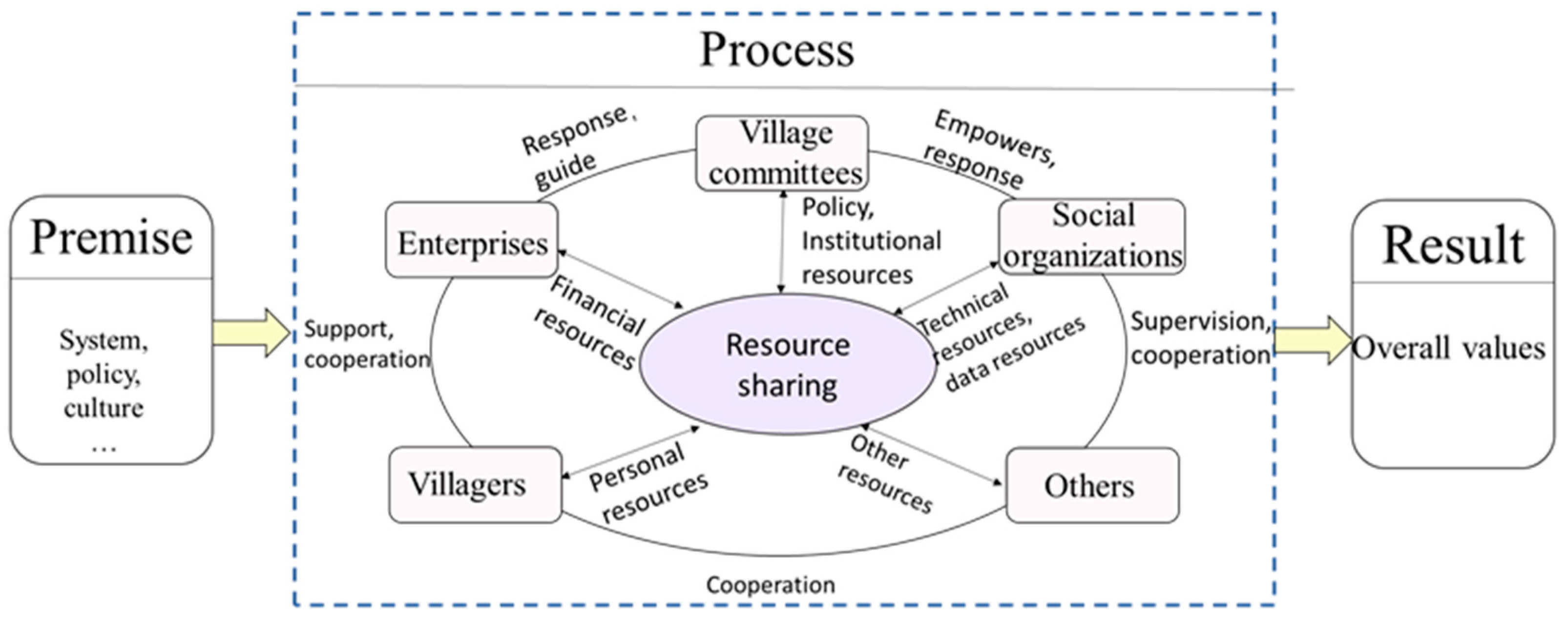

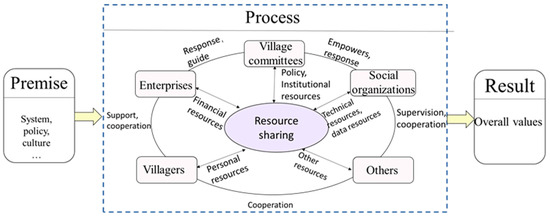

6.1. Macro Level

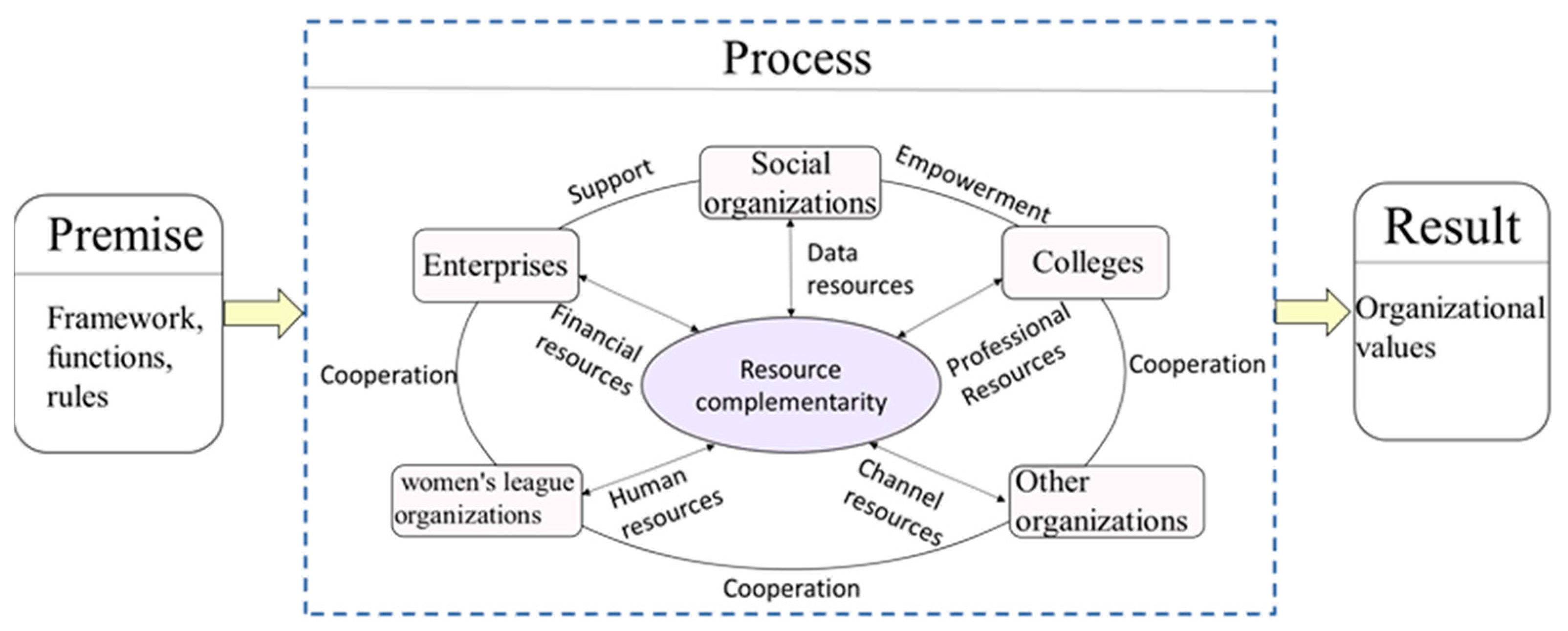

Service ecosystem theory focuses on institutions, policies, and culture at the macro level [53]. Macro level-value co-creation refers to the process of acquiring, configuring, and integrating resources at different levels, from different sources, and with different contents in an orderly manner, guided by policies and systems, and realized through complex heterogeneous interactions among different subjects, as shown in Figure 4. Firstly, the rapid flux and deep deconstruction of rural social structure urgently need to be solved through innovative governance [54]. With this common value belief, village committees have introduced a series of policies to promote rural construction. The social organization was given a legal identity to participate in community governance by village committees in an institutionalized form. As the activities and behaviors of the subjects are legalized and institutionalized, the enthusiasm of the subjects is stimulated, and the resources belonging to the subjects are effectively allocated under the unified regulation of the system. Secondly, facing the complex interests of market subjects, village committees introduce relevant policies to encourage and guide enterprises to support and build local industries in rural communities. For example, it provides enterprises with information services, such as traffic flow and data, and helps them to develop sales channels as well as to organize joint activities for the public good. These approaches can fulfill the subject’s function of docking resources. In addition, the integration of resources such as contacts, knowledge, and technology of social organizations, enterprises, and individuals innovates the dissemination of governance work and gives full play to the expertise or social influence of these subjects, thus expanding the impact of governance work.

Figure 4.

Macro level framework for value co-creation in rural communities.

Overall, the transformation of the rural social structure brings possibilities for the reintegration of different resources [55]. Under the regulatory role of policies and institutions, different subjects interact through the relationships of empowerment, cooperation, supervision, etc., thereby realizing the resource sharing and the value of all subjects at the macro level, thus promoting value co-creation at the macro level.

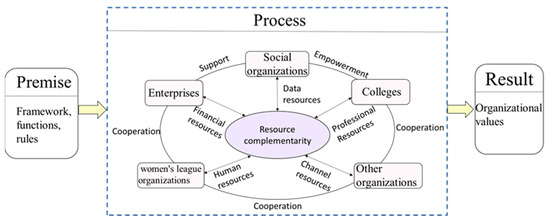

6.2. Meso Level

Service ecosystems focus on the interactions between organizations at the meso level [56]. Organizations need to build strong relationships with their stakeholders because the actions taken by the organization affect the interests of the stakeholders, thus affecting the effectiveness of the cooperation [28]. The authors draw on Merton’s view to explore the interactions between organizations at the meso level from the perspectives of structure, function, and rules [57]. Value co-creation at the meso level is a process whereby subjects realize resource complementarity through cooperative, empowering partnerships under the roles of structure, function, and rules, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Meso level framework for value co-creation in rural communities.

First, the way of interaction between organizations is affected by organizational structure, which determines the way of coordination and communication [58]. Effective communication and coordination between different organizations can be facilitated through collaborative platforms and regular meetings between cooperating organizations. For example, the representative of a social organization (WW1) said, “We communicate regularly with enterprises about the activities carried out on the Platform, and the persons in charge ensure the fair distribution of resources through numerous consultations. In addition, we have published relevant content on our public website, which has attracted many tourists to visit the museum, and at the same time we have created relevant cultural and creative products, which have shaped the image of the enterprise and expanded the visibility of the community”.

Second, different organizations have different advantages in terms of resources, skills, and expertise. They can combine their functions through cooperation to achieve resource complementarity [59]. For example, the representative of the social organization (WM2) said “We make use of the non-heritage cultural knowledge resources we have and unite with some colleges and universities in Guizhou province to carry out basic research while the results of the basic research provide a large number of vivid materials for the dissemination of local resources, attracting more main bodies to join in the action of community resource integration”. In addition, the entrepreneur (GM8) said that “we invested in local agricultural and sideline products, while the village stewards provided us with knowledge and networking resources, and we jointly designed more innovative product packaging, which drove sales of the products”. Functional complementarity is the basis of cooperation, which can promote sound interaction between organizations and increase the value of cooperation [59]. However, functional differences between organizations may also lead to role conflict and coordination difficulties in cooperation, which require institutional rules to play a certain coordinating role [57].

Interactions between organizations are governed and regulated by rules to ensure fairness and sustainability of cooperation [58]. For example, the head of the village committee (GW6) said that “to avoid conflicts of interest that may affect the efficiency of the cooperation, we signed a contract with the enterprise to purchase products and set up a system of dividends from the shares to ensure that we have a long-term and solid cooperative relationship with each other”.

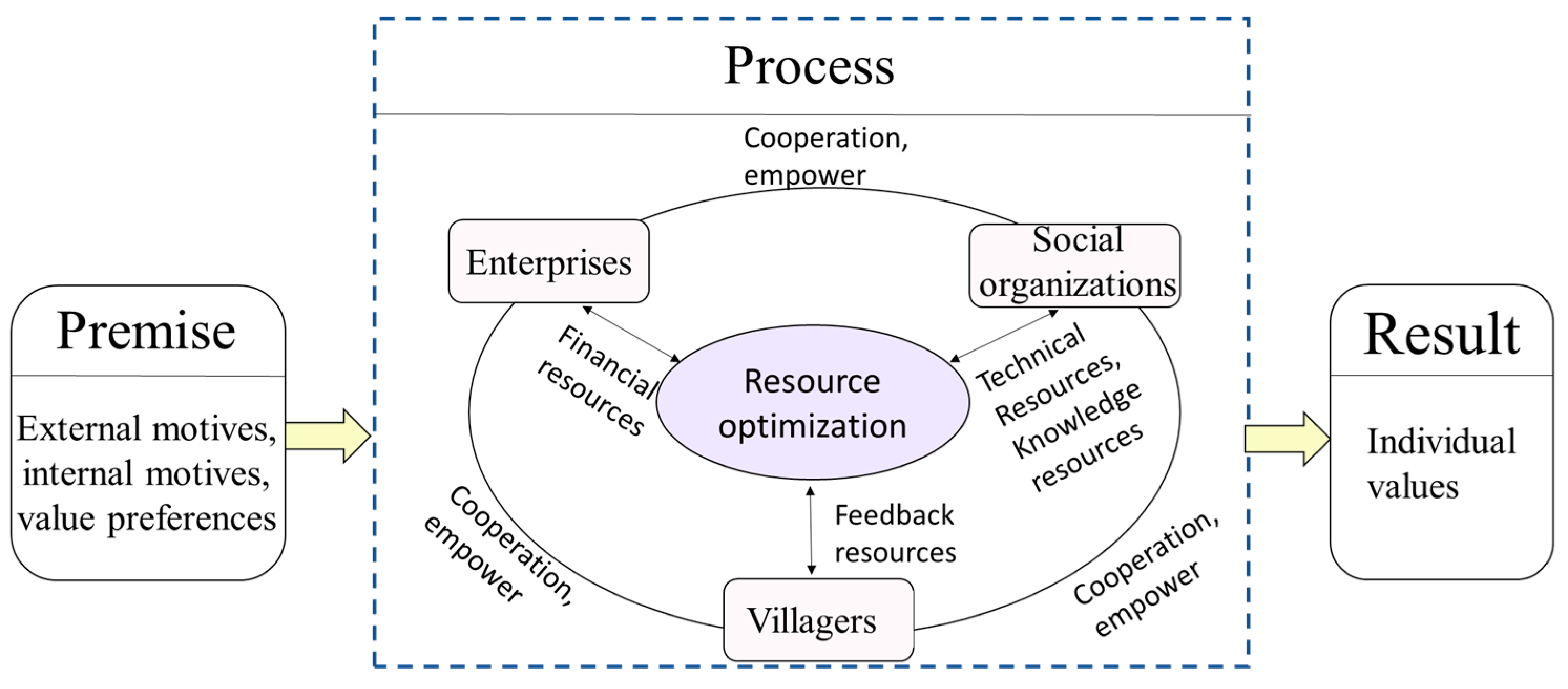

6.3. Micro Level

Service ecosystem theory focuses on the interaction between organizations and individuals, and individuals and individuals at the micro level [36]. In value co-creation at the micro level, external motives, internal motives, and value preferences influence individuals’ willingness to cooperate and their action logic [60], and they interact with each other through cooperative and empowering relationships to optimize their resources, as shown in Figure 6. First, external motives such as economic and political interests can motivate subjects to cooperate [61]. For example, the representative of the social organization (WW1) explained that “to strengthen the organization, we not only need to achieve our improvement in traditional cultural knowledge but also need a certain economic base to support the long-term development of the organization”. In addition, the head of the village committee (GM4) said, “Due to the aging and hollowing out the phenomenon of rural communities, it is difficult to achieve governance innovation by the village committee alone. We can reduce the cost of governance to a certain extent by uniting villagers, enterprises, and other subjects for co-development”. Moreover, to protect the basic interests of individuals and families, villagers are deeply involved in the process of monitoring community management and use their resources to provide continuous feedback, which improves private values and brings about improvements in the public values of the community at the same time. Also, these behaviors are not a direct result of policy interventions, which means that villagers tend to contribute more when the benefits of cooperation have a lasting and critical impact on them [62].

Figure 6.

Micro level framework for value co-creation in rural communities.

Second, participation in the value co-creation activity provides individuals with a rich participatory experience, permeating the interaction between individuals and the activity and between individuals and other individuals [63]. In our study, we found that the intrinsic feelings of individuals in participating in the governance of rural communities are manifested as gratitude, a sense of belonging, and self-efficacy. These feelings shape the value co-creation behavior, which prompts the subject to generate the intrinsic motives of equal exchange and mutual benefit, and altruism [64]. For example, a villager (WW9) said, “After the environmental sanitation improvement in our village, the village road is wider and more convenient for traveling, and the front and back of my house have become more and more tidy. Folks chat in the leisure square after dinner, the quality of life has improved a lot more than before”. Another villager (WM10) also said, “In the past, the scale of my family’s agricultural products was very small, but now I earn about 100,000 yuan a year, thanks to the development of the industry”. Villagers’ sense of belonging is fulfilled during their participation in community activities, which makes it easier for villagers to have positive interactions with community workers and other residents, which in turn enhances villagers’ willingness to put in efforts and engage in diversified behaviors that are in line with the common good [65].

Finally, value preferences affect the subject’s concern for community affairs and attention to public interests [66]. For example, the entrepreneur (WW7) said, “I have always been interested in intangible cultural heritage, so I have invested as start-up capital to carry out public welfare activities related to intangible culture to promote the development of this traditional cultural village”. Such values can combine subjects’ participatory and obligatory value preferences at the behaviorist level and stimulate their initiative in the value co-creation of rural communities.

Through the above in-depth analysis, the authors further optimized the value co-creation mechanism model of rural communities from the perspective of the service ecosystem and obtained the realization path of value co-creation of rural communities from the perspective of the service ecosystem, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The realization path of value co-creation mechanism in rural communities from the perspective of service ecosystem. Note: * represents key elements.

7. Discussion

What makes value co-creation in rural communities possible? The cases of value co-creation in Wenggong and Gumeng villages show that they were able to embark on the path of rural revitalization only because of specific institutional and cultural conditions. The mutual embedding of village committees, enterprises, social organizations, villagers, and other subjects has led to a good collaborative governance dynamic in rural communities. Village committees provide institutional, physical, and social infrastructure for rural communities’ development to encourage innovative activities of social organizations. Social organizations bring together businesses and villagers formally or informally to build networks and platforms. Local social organizations and villagers are knowledge and cultural producers in rural areas, and interactive participation can promote rural culture and agricultural industries. In addition, in the case of this paper, the local cultural identity mainly includes the identity of ethnic minority culture from different subjects such as enterprises, social organizations, villagers, and tourists. Firstly, social organizations attach great importance to the cultural expression of Wenggong Village and consciously take on the role of protectors and inheritors of culture. Social organizations have turned local intangible cultural heritage into cultural industries and have joined forces with local enterprises to build tourism, cultural spaces, and cultural symbols with ethnic minority characteristics. Secondly, with the rapid advance of industrialization and urbanization, the culture of ethnic minority regions has gradually been impacted and forgotten. Enterprises and social organizations have built the platform of non-heritage cultural museums to transform ethnic minority cultures into productive forces and awaken the cultural identity of villagers. Villagers participate in rural development through multiple channels to promote the spatial reproduction of non-heritage culture. Villagers’ attitude towards local culture has changed from passive dissemination driven by economic interests to active protection and inheritance under the reconstruction of cultural identity. Multiple subjects activate and integrate resources in relational interactions, which have a positive significance in cracking the low-level cycle of endogenous development in the countryside [67].

What makes value co-creation in rural communities sustainable? Theories related to organizational ecology suggest that any organization, on the one hand, should effectively adapt to the external environment and meet the requirements of the external environment; on the other hand, it should have a certain degree of autonomy and control over the internal environment of the organization [68]. Drawing from this perspective, the authors argue that the sustainability of value co-creation in rural communities lies in the combination of adaptation and autonomy, whereby subjects continuously adapt to the external environment while ensuring the flexible disposition of internal resources through relational interaction and resource integration. It is worth noting that none of the village committees, enterprises, or villagers can play a role independently. While institution-building requires the functioning of administrative governance, the effectiveness of resource allocation relies on markets and social governance playing an active role. Market governance requires institutional support and regulation by administrative forces to avoid unfair distribution of resources and deeper participation by villagers to stimulate market vitality [4]. And, whether community governance can play a positive role or not, it needs to be led and stimulated by market forces and guaranteed by administrative forces [69]. Therefore, the interdependence between the subjects can overcome the problem of value co-destruction that may arise in the process of value co-creation, thus making value co-creation in rural communities sustainable.

8. Conclusions

This paper focuses on the core issue of the formation mechanism of value co-creation in rural communities under the service ecosystem, takes the typical rural communities in Guiyang City as the case study object, and draws on the IPO theoretical model to specifically explore the value co-creation mechanism in rural communities. The study found that value co-creation in rural communities, from the perspective of service ecosystems, follows the path of “value co-creation conditions (value proposition)–value co-creation process (value communication, value recognition and reconstruction, and value link)– value co-creation results (public value)”. The core mechanism in the process of value co-creation is “subject embedding–relationship interaction–resource integration”. Specifically, at the macro level, resource sharing is achieved through complex and heterogeneous interactions among multiple subjects under the influence of institutions, policies, and cultures. At the meso level, organizations complement each other’s resources by cooperating and empowering other actors horizontally under the influence of structure, function, and rules. At the micro level, individuals optimize resources through cooperative and empowering interactions under the influence of internal and external motivations and value preferences. Ultimately, combining individual, organizational, and overall values, with key elements working together across levels, constitutes public value.

8.1. Theoretical Implications

Firstly, most of the existing studies on value co-creation are of the theoretical review type of literature, carried out in a city context, and they have usefully explored mainly the underlying concepts, interaction structures, and facilitating factors [53,57,70]. However, research exploring how value co-creation mechanism is formed in rural areas is not extensive enough. This study has refined conclusions that are different from the formation mechanism of value co-creation in a city context, thus bridging the theoretical gap caused by insufficient consideration of the research context in the existing literature, to a certain extent, and extending the scope of application of the value co-creation theory.

Secondly, based on the service ecosystem perspective, this study deconstructs the key elements in the formation of value co-creation mechanisms in rural communities and explores the mechanisms through which multiple subjects within the service ecosystem realize value co-creation, using different interactive relationships and resource integration modes under the role of institutional, structural, and motivational factors, responding to the research on value co-creation proposed by scholars such as Meynhardt, Chandler, Strathoff, Merton, Xuejun Wang, and Hangyu Li. Service ecosystems emphasize the interaction of different subjects, and rural communities involve multiple subjects, such as village committees, villagers, and enterprises, in the value co-creation process. By analyzing the effects of different facilitators on the subjects, the interaction between different subjects can be better understood, thus deepening the study of the relationship between value co-creation in rural communities under service ecosystems.

Thirdly, existing studies have focused on the impact of value co-creation facilitators at a single level [71], ignoring their role across levels. Alternatively, they have focused on cross-level value co-creation research with a single facilitator [70], making existing studies on value co-creation in rural areas fragmented and lacking a systematic theoretical analytical framework. This paper analyses the facilitating factors of value co-creation from macro, meso, and micro levels, and extracts the core mechanism of “subject embedding–relationship interaction–resource integration” in the process of value co-creation, which provides certain insights for the operation and governance of value co-creation in rural communities.

8.2. Policy Implications

Firstly, local governments should take into account the actual local situation and introduce relevant systems in accordance with local conditions to provide the subjects with an institutional framework and guidelines for action. Meanwhile, they should increase the dissemination of guidance promoting rural construction through the official government website, the media, and other forms. Regarding policy, the government should encourage social forces, such as enterprises and villagers, to participate in rural revitalization. Value co-creation is being carried out through the construction of a structure of pluralistic rural governance subjects, forming a new network of rural production relations. Rationally supporting and guiding the development of social forces will further promote the modernization of the country’s governance system and capacity and provide a new direction for sustainable rural development. Secondly, local small enterprises can enhance their core competitiveness and sustainable development capacity by learning advanced technology and management experience from large enterprises. Cross-regional and cross-sectoral cooperation between different enterprises can be carried out to create a scale effect to achieve synergy of interests. Finally, the main position of villagers should be clarified, and villagers should be guided to participate in depth, through the regular organization of cultural activities to awaken the villagers’ identification with and love of their native culture, and to enhance their cultural self-confidence.

Limitations: The two cases selected for this paper originate from Guiyang City, China, which may bias the findings due to social structure and institutional environment differences in rural communities. In the future, the authors will try to increase the number of cases from different regions to obtain more sound evidence and improve the research’s credibility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.X.; methodology, Y.W. and L.X.; software, J.L.; validation, Y.W.; formal analysis, M.I.G.; investigation, Y.W. and L.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.W. and L.X.; supervision, L.X.; funding acquisition, L.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 21BZZ054).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Xi, J. Take rural revitalization strategy as the general gripper of “three rural” work in the new era. Social. Forum 2019, 7, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Huang, Y.; Tan, S.; Lang, W.; Chen, T. Jointly Creating Sustainable Rural Communities through Participatory Planning: A Case Study of Fengqing County, China. Land 2023, 12, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, B.; Chen, H. Social entrepreneurship and rural revitalization. Acad. Mon. 2018, 50, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Hu, Y. Research on the realization path of corporate social entrepreneurship for rural revitalization under the perspective of value co-creation. Agric. Econ. Issues 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Tian, H. Industrial and commercial capital to the countryside, factor allocation and agricultural production efficiency. Agric. Technol. Econ. 2018, 9, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Rural spatial production and governance reconfiguration driven by market capital-an empirical observation of Y village in Wuyuan County. Hum. Geogr. 2020, 35, 86–92+114. [Google Scholar]

- Da, L.; Liu, X. Research on poverty alleviation in rural tourism under the perspective of relative deprivation—The case of Wanfenglin community in Xingyi, Guizhou. Reg. Res. Dev. 2019, 38, 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. From Repeat Patronage to Value Co-creation in Service Ecosystems: A Transcending Conceptualization of Relationship. J. Bus. Mark. Manag. 2010, 4, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, S.P. From public service-dominant logic to public service logic: Are public service organizations capable of co-production and value co-creation? Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L. Optimizing the Supply of Rural Public Services and Enhancing the Effectiveness of Social Governance at the Grassroots Level. Macroecon. Manag. 2022, 10, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Su, T.; Wang, K. Value co-creation mechanism of service ecosystem in digital environment—A case study of Shanghai “May 5th Shopping Festival”. Res. Dev. Manag. 2021, 33, 142–157. [Google Scholar]

- Galvagno, M.; Dalli, D. Theory of Value Co-creation. A Systematic Literature Review. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2014, 24, 643–683. [Google Scholar]

- Voorberg, W.; Bekkers, V.; Tummers, L.A. Systematic Review of Co-creation and Co-production: Embarki ng on the Social Innovation Journey. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 9, 1333–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R.; Vargo, S. Service-Dominant Logic: Reactions, Reflections and Refinements. Mark. Theory 2006, 3, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wen, Y.; Jin, J.; Zhang, Y. Towards a service-dominant platform for public value co-creation in a smart city: Evidence from two metropolitan cities in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 142, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.; Vafeas, M.; Hilton, T. Resource integration for co-creation between marketing agencies and clients. Eur. J. Mark. 2018, 52, 1329–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C.; Voima, P. Critical service logic: Making sense of value creation and co-creation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R.F.; Vargo, S.L. Service-Dominant Logic: Premises, Perspectives, Possibilities; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, V.; Goyal, P.; Jebarajakirthy, C. Value co-creation: A review of literature and future research agenda. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2022, 37, 612–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohtamäki, M.; Rajala, R. Theory and practice of value co-creation in B2B systems. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 56, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McColl-Kennedy, J.R.; Vargo, S.L.; Dagger, T.S.; Sweeney, J.C.; Kasteren, Y.V. Health care customer value cocreation practice styles. J. Serv. Res. 2012, 15, 370–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.H.M.; Van Dolen, W. Creative participation: Collective sentiment in online co-creation communities. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 951–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Chen, Y.; Filieri, R. Resident-tourist value co-creation: The role of residents’ perceived tourism impacts and life satisfaction. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breidbach, C.F.; Maglio, P.P. Technology-enabled value co-creation: An empirical analysis of actors, resources, and practices. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 56, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. Value co-creation in service logic: A critical analysis. Mark. Theory 2011, 11, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyer, B.G.; Kastanakis, M.N.; Rhode, A.K. Co-creating stakeholder and brand identities: A cross-cultural consumer perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.; Jian, Z.; Li, L. Service ecosystems: Origins, core perspectives and theoretical framework. Res. Dev. Manag. 2018, 30, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Banoun, A.; Dufour, L.; Andiappan, M. Evolution of a service ecosystem: Longitudinal evidence from multiple shared services centers based on the economies of worth framework. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2990–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Z.; Zurlo, F.; Camussi, E.; Annovazzi, C. Service Ecosystem Design for Improving the Service Sustainability: A Case of Career Counselling Services in the Italian Higher Education Institution. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Akaka, M.A. Value cocreation and service systems (re) formation: A service ecosystems view. Serv. Sci. 2012, 4, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaka, M.A.; Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. The complexity of context: A service ecosystems approach for international marketing. J. Int. Mark. 2013, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.D.; Danatzis, I.; Wernicke, C.; Akaka, M.A.; Reynolds, D. How does innovation emerge in a service ecosystem? J. Serv. Res. 2019, 22, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frow, P.; McColl-Kennedy, J.R.; Payne, A. Co-creation practices: Their role in shaping a health care ecosystem. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 56, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaka, M.A.; Koskela-Huotari, K.; Vargo, S.L. Further Advancing Service Science with Service-Dominant Logic: Service Ecosystems, Institutions, and Their Implications for Innovation; Handbook of Service Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2009; Volume 2, pp. 641–659. [Google Scholar]

- Vink, J.; Koskela-Huotari, K.; Tronvoll, B.; Edvardsson, B.; Wetter-Edman, K. Service Ecosystem Design: Propositions, Process Model, and Future Research Agenda. J. Serv. Res. 2021, 24, 168–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polese, F.; Vesci, M.; Troisi, O.; Grimaldi, M. Reconceptualizing TQM in service ecosystems: An integrated framework. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2019, 11, 104–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J. Comparative analysis of social structure change in rural China since reform and opening up. Rural. Econ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 32, 243–245. [Google Scholar]

- Juan, F. Problems and Countermeasures of Rural Community Building in the Context of Rural Hollowing Out. Agric. Econ. 2022, 425, 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, D.F. Visual imagery differences in the recall of pictures. Br. J. Psychol. 2011, 64, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.D.; Vargo, S.L. Contextualization and value-in-context: How context frames exchange. Mark. Theory 2011, 11, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Wei, J.; Zhou, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, W. Research outlook of service science and innovation management in network environment. China Manag. Sci. 2018, 26, 186–196. [Google Scholar]

- Gummerus, J. Value creation processes and value outcomes in marketing theory: Strangers or siblings? Mark. Theory 2013, 13, 19–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, X. “Divide” and “merge”: Classification of rural regional villages under the perspective of qualitative research. Shandong Soc. Sci. 2016, 7, 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, D.; Myrick, F. Grounded theory: An exploration of process and procedure. Qual. Health Res. 2006, 16, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charmaz, K.; Thornberg, R. The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandkar, S.H. Open Coding; University of Calgary: Calgary, Canada, 2009; p. 23.2009. [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam, A. Coding issues in grounded theory. Issues Educ. Res. 2006, 16, 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. Grounded Theory: Strategies Qualitative Frosting; Huber: Edison, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Meynhardt, T.; Chandler, J.D.; Strathoff, P. Systemic principles of value co-creation: Synergetics of value and service ecosystems. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2981–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiqiang, L.; Qinghua, W. “Structure-function” interoperability theory: A new explanatory framework for innovative social management research in transitional rural areas—Based on the dimension of rural social organizations. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 2014, 14, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Chunxia, Z. Rural Social Management Innovation under the Threshold of Structural Functionalism—An Empirical Analysis Based on the 2005 CGSS. Southeast Acad. 2012, 3, 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Frow, P.; McColl-Kennedy J, R.; Hilton, T.; Davidson, A.; Payne, A.; Brozovic, D. Value propositions: A service ecosystems perspective. Mark. Theory 2014, 14, 327–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R.K. Social Theory and Social Structure; Simon and Schuster: New York, NJ, USA, 1968; pp. 65–66. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R.K. Social structure and anomie. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1938, 3, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R.K. The functions of the professional association. Am. J. Nurs. 1958, 26, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Li, H. Motivational Mapping of Public Participation in Cooperative Production and Its Impacts—A Mixed Study under the Perspective of Value Co-Creation. Public Adm. Rev. 2023, 16, 4–24+196. [Google Scholar]

- Asquer, A.; Street, T.; Square, R. Co-Investment in the Co-Production of Public Services: Are Clients Willing to Do It. In Proceedings of the Workshop on “Co-Production in Public Services: The State of the Art”, Corvinus University, Budapest, Hungary, 22–23 November 2012; pp. 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pestoff, V. Co-production and third sector social services in Europe: Some concepts and evidence. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2012, 23, 1102–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, S.P.; Radnor, Z.; Strokosch, K. Co-Production and the Co-Creation of Value in Public Services: A suitable case for treatment? Public Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.E.; Kilpatrick, S.D.; Emmons, R.A.; Larson, D.B. Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letki, N.; Steen, T. Social-psychological context moderates’ incentives to co-produce: Evidence from a large-scale survey experiment on park upkeep in an urban setting. Public Adm. Rev. 2021, 81, 935–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzochukwu, K.; Thomas, J.C. Who engages in the coproduction of local public services and why? The case of Atlanta, Georgia. Public Adm. Rev. 2018, 78, 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, M.; Shang, P.; Wu, X. How to crack the internal and external linkage but internal immobility of rural revitalization—Based on the practical investigation of Arrow Tower Village, Pujiang County, Chengdu City. Agric. Econ. Issues 2023, 3, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hannan, M.T.; Freeman, J. The population ecology of organizations. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 82, 929–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X. Governance embeddedness and the diversity of innovation policies:A reconceptualisation of state-market-society relations. Public Adm. Rev. 2017, 10, 6–32+209. [Google Scholar]

- Beirão, G.; Patrício, L.; Fisk, R.P. Value cocreation in service ecosystems: Investigating health care at the micro, meso, and macro levels. J. Serv. Manag. 2017, 28, 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Ye, L.; Dong, X. Value co-creation mechanism of innovation ecosystem--a case study based on Tencent Crowd Creative Space. Res. Dev. Manag. 2018, 30, 24–36. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).