Why Do Older Adults Feel Negatively about Artificial Intelligence Products? An Empirical Study Based on the Perspectives of Mismatches

Abstract

:1. Introduction

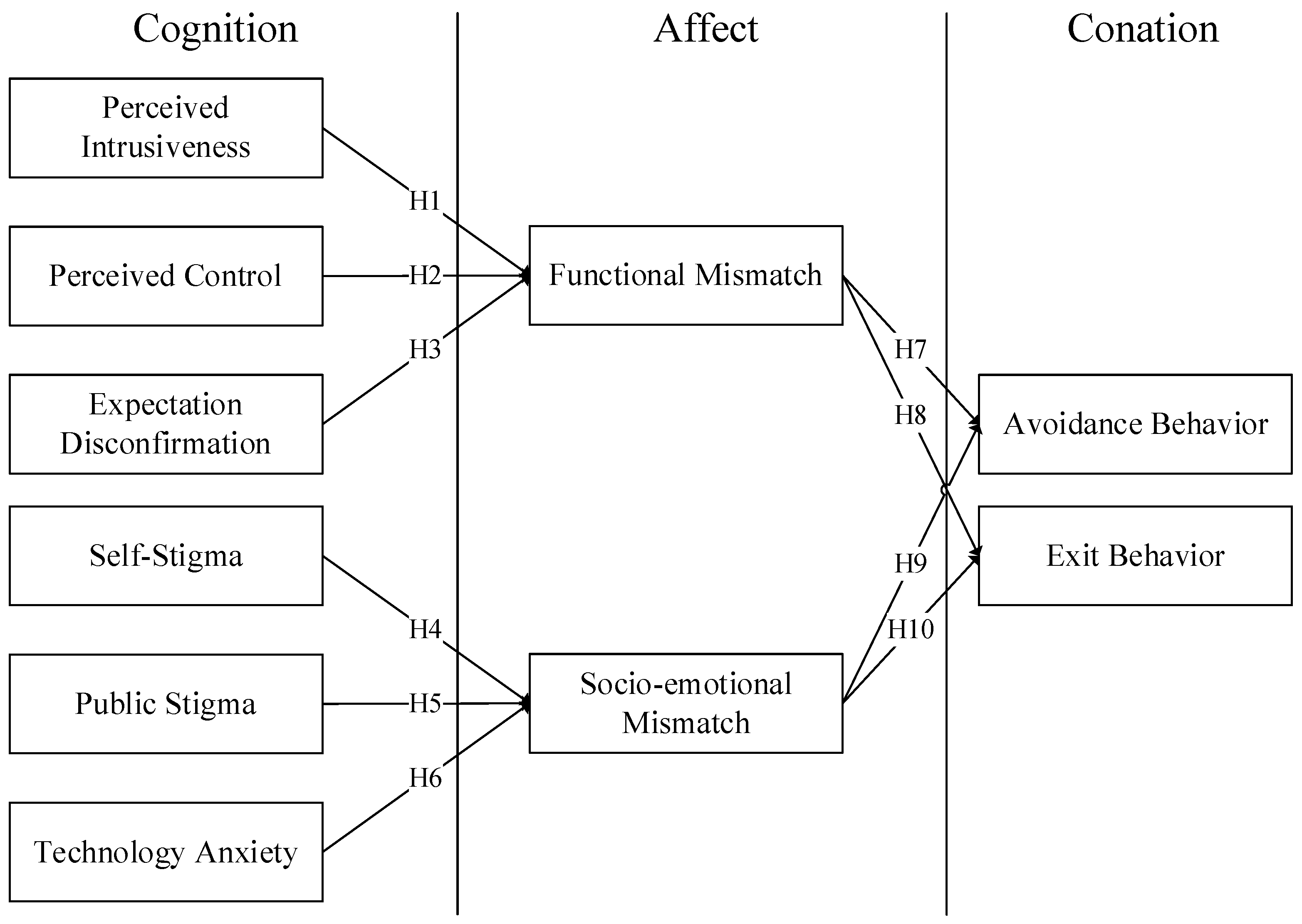

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. The Cognition–Affect–Conation Pattern

2.2. Negative Effects of AIPs for Older People

2.3. Functional Mismatch of AIPs

2.4. Socio-Emotional Mismatch of AIPs

2.5. Avoidance and Exit Behavior

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Survey Instruments

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement Model Testing

4.1.1. Common Method Biases and Multicollinearity

4.1.2. Reliability and Validity

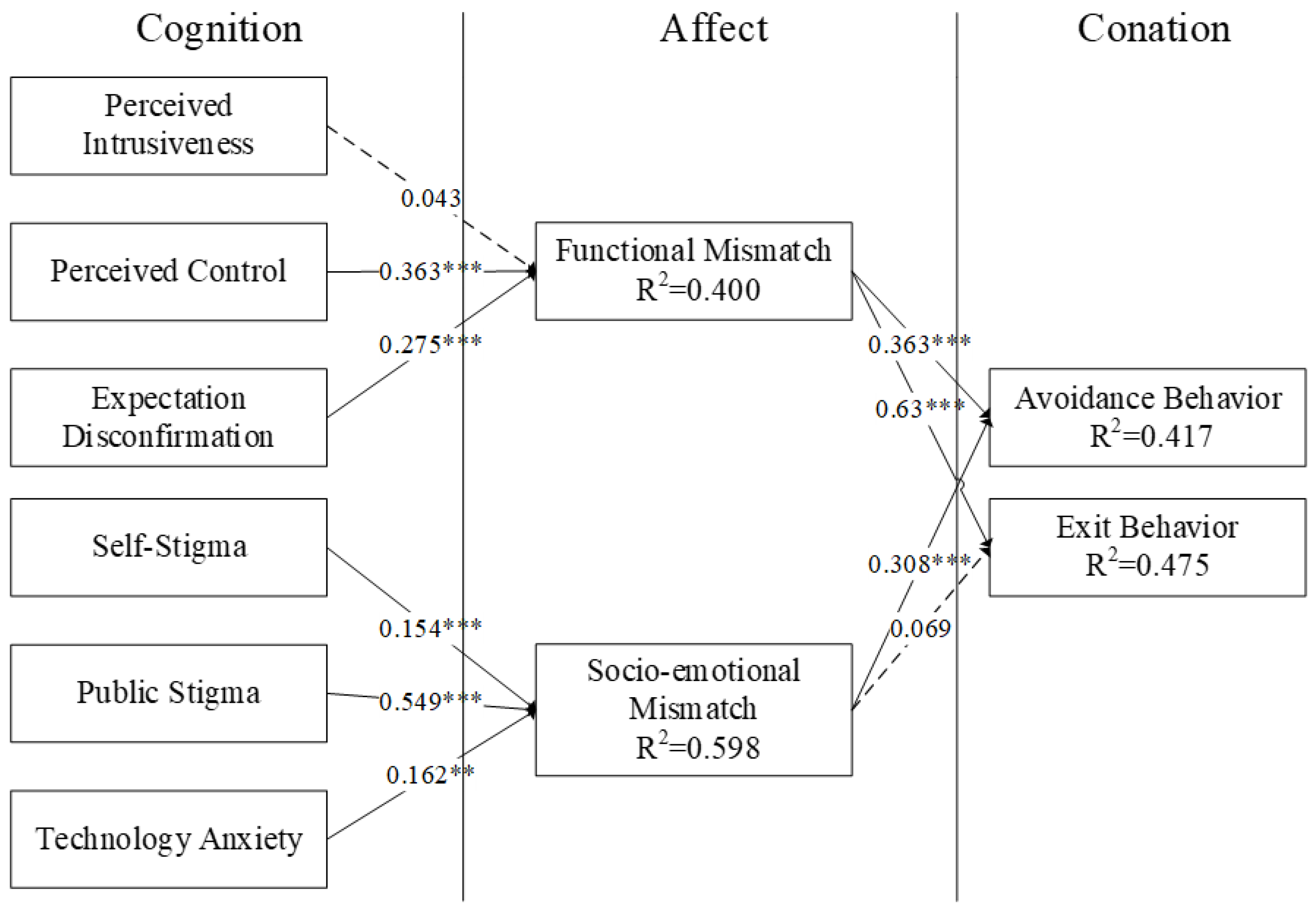

4.2. Structural Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Implications for Research

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haibe-Kains, B.; Adam, G.A.; Hosny, A.; Khodakarami, F.; Waldron, L.; Wang, B.; McIntosh, C.; Goldenberg, A.; Kundaje, A.; Greene, C.S. Transparency and reproducibility in artificial intelligence. Nature 2020, 586, E14–E16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, K.; Kwon, O. Technology acceptance theories and factors influencing artificial Intelligence-based intelligent products. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 47, 101324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dis, E.A.; Bollen, J.; Zuidema, W.; van Rooij, R.; Bockting, C.L. ChatGPT: Five priorities for research. Nature 2023, 614, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusif, S.; Soar, J.; Hafeez-Baig, A. Older people, assistive technologies, and the barriers to adoption: A systematic review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2016, 94, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubeis, G. The disruptive power of artificial intelligence. Ethical aspects of gerontechnology in elderly care. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 91, 104186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Hughes, L.; Ismagilova, E.; Aarts, G.; Coombs, C.; Crick, T.; Duan, Y.; Dwivedi, R.; Edwards, J.; Eirug, A. Artificial Intelligence (AI): Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 57, 101994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.H.; Nyrup, R.; Leslie, K.; Shi, J.; Bianchi, A.; Lyn, A.; McNicholl, M.; Khan, S.; Rahimi, S.; Grenier, A. Digital Ageism: Challenges and Opportunities in Artificial Intelligence for Older Adults. Gerontologist 2021, 62, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-K. Gerontechnology and artificial intelligence: Better care for older people. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 91, 104252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angeli, A.; Jovanović, M.; McNeill, A.; Coventry, L. Desires for active ageing technology. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2020, 138, 102412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Xu, B.; Zhao, Z. Can People Experience Romantic Love for Artificial Intelligence? An Empirical Study of Intelligent Assistants. Inf. Manag. 2022, 59, 103595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berridge, C.; Grigorovich, A. Algorithmic harms and digital ageism in the use of surveillance technologies in nursing homes. Front. Sociol. 2022, 7, 957246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merkel, S.; Kucharski, A. Participatory design in gerontechnology: A systematic literature review. Gerontologist 2019, 59, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephanidis, C.; Salvendy, G.; Antona, M.; Chen, J.Y.; Dong, J.; Duffy, V.G.; Fang, X.; Fidopiastis, C.; Fragomeni, G.; Fu, L.P. Seven HCI grand challenges. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2019, 35, 1229–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.H.; Werder, K.; Cao, L.; Ramesh, B. Why do Family Members Reject AI in Health Care? Competing Effects of Emotions. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2022, 39, 765–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K. Why do older people love and hate assistive technology?—An emotional experience perspective. Ergonomics 2020, 63, 1463–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Ali, A.; Wang, H. Exploring information avoidance intention of social media users: A cognition–affect–conation perspective. Internet Res. 2020, 30, 1455–11478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.W.; Tang, Y.; Yip, L.S.; Sharma, P. Managing customer relationships in the emerging markets–guanxi as a driver of Chinese customer loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiotsou, R.H. Sport team loyalty: Integrating relationship marketing and a hierarchy of effects. J. Serv. Mark. 2013, 27, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Osatuyi, B.; Xu, L. How mobile augmented reality applications affect continuous use and purchase intentions: A cognition-affect-conation perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.-B.; Du, C.-T. Mobile Social Network Sites as innovative pedagogical tools: Factors and mechanism affecting students’ continuance intention on use. J. Comput. Educ. 2014, 1, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, F.; Qu, Q.-X.; Hao, D. How Does Perceived Overload in Mobile Social Media Influence Users’ Passive Usage Intentions? Considering the Mediating Roles of Privacy Concerns and Social Media Fatigue. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2021, 38, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glikson, E.; Woolley, A.W. Human Trust in Artificial Intelligence: Review of Empirical Research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2020, 14, 627–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Zhang, Z.; Yamamoto, Y.; Schuller, B.W. Artificial intelligence internet of things for the elderly: From assisted living to health-care monitoring. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2021, 38, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Weert, J.; Van Munster, B.C.; Sanders, R.; Spijker, R.; Hooft, L.; Jansen, J. Decision aids to help older people make health decisions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2016, 16, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siau, K.; Wang, W. Artificial intelligence (AI) ethics: Ethics of AI and ethical AI. J. Database Manag. 2020, 31, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, A.; Fernández-Ardèvol, M. Structural ageism in big data approaches. Nord. Rev. 2019, 40, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Shi, K.; Yang, C.; Niu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, N.; Liu, T.; Chu, C.H. Ethical issues of smart home-based elderly care: A scoping review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 30, 3686–3699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damant, J.; Knapp, M.; Freddolino, P.; Lombard, D. Effects of digital engagement on the quality of life of older people. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 1679–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplante, P.; Milojicic, D.; Serebryakov, S.; Bennett, D. Artificial intelligence and critical systems: From hype to reality. Computer 2020, 53, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer Dahlke, D.; Ory, M.G. Emerging opportunities and challenges in optimal aging with virtual personal assistants. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2017, 27, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortellessa, G.; De Benedictis, R.; Fracasso, F.; Orlandini, A.; Umbrico, A.; Cesta, A. AI and robotics to help older adults: Revisiting projects in search of lessons learned. Paladyn J. Behav. Robot. 2021, 12, 356–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Bolling, K.; Mao, W.; Reichstadt, J.; Jeste, D.; Kim, H.-C.; Nebeker, C. Technology to support aging in place: Older adults’ perspectives. Healthcare 2019, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, M.; Estève, D.; Fourniols, J.-Y.; Escriba, C.; Campo, E. Smart wearable systems: Current status and future challenges. Artif. Intell. Med. 2012, 56, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Chan, A.H.-S. Use or non-use of gerontechnology—A qualitative study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 4645–4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Chan, A.H.S. Gerontechnology acceptance by elderly Hong Kong Chinese: A senior technology acceptance model (STAM). Ergonomics 2014, 57, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwijsen, S.A.; Niemeijer, A.R.; Hertogh, C.M. Ethics of using assistive technology in the care for community-dwelling elderly people: An overview of the literature. Aging Ment. Health 2011, 15, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Han, S. Investigating older consumers’ acceptance factors of autonomous vehicles. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Lee, C.-F.; Xu, S. Stigma Threat in Design for Older Adults: Exploring Design Factors that Induce Stigma Perception. Int. J. Des. 2020, 14, 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Di Giacomo, D.; Ranieri, J.; D’Amico, M.; Guerra, F.; Passafiume, D. Psychological barriers to digital living in older adults: Computer anxiety as predictive mechanism for technophobia. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Schwemmle, M.; Kuehnl, C. New product design: Concept, measurement, and consequences. J. Mark. Anal. 2015, 79, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.-L.; Duan, S.-F.; Lyu, X. Affective Voice Interaction and Artificial Intelligence: A research study on the acoustic features of gender and the emotional states of the PAD model. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 664925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Tang, M. Exploiting user experience from online customer reviews for product design. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 46, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menghi, R.; Papetti, A.; Germani, M. Product Service Platform to improve care systems for elderly living at home. Health Policy Technol. Soc. 2019, 8, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbilek, O.; Demirkan, H. Universal product design involving elderly users: A participatory design model. Appl. Ergon. 2004, 35, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrahi, M.H. Artificial intelligence and the future of work: Human-AI symbiosis in organizational decision making. Bus. Horiz. 2018, 61, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.T.; Rice, C.; Lam, M.; Chandler, E.; Lee, K.J. Toward TechnoAccess: A narrative review of disabled and aging experiences of using technology to access the arts. Technol. Soc. 2021, 65, 101537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. Ethical issues in service robotics and artificial intelligence. Serv. Ind. J. 2021, 41, 860–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, M.U. Regulating artificial intelligence systems: Risks, challenges, competencies, and strategies. Harv. JL Tech. 2015, 29, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.; Magerko, B. What is AI literacy? Competencies and design considerations. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cukier, K. Commentary: How AI shapes consumer experiences and expectations. J. Mark. Res. 2021, 85, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiselman, H.L. A review of the current state of emotion research in product development. Food Res. Int. 2015, 76, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, H.M.; Helander, M.G. Customer emotional needs in product design. Concurr. Eng. 2006, 14, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Morris, S.B.; Michaels, P.J.; Rafacz, J.D.; Rüsch, N. Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: A meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatr. Serv. 2012, 63, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogra, N.; Adil, M.; Sadiq, M.; Rafiq, F.; Paul, J. Demystifying tourists’ intention to purchase travel online: The moderating role of technical anxiety and attitude. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 26, 2164–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Ji, Y.; Jiang, S.; Liu, X.; Feng, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Integrating aesthetic and emotional preferences in social robot design: An affective design approach with Kansei engineering and deep convolutional generative adversarial network. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2021, 83, 103128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Demiris, G.; Thompson, H.J. Ethical considerations regarding the use of smart home technologies for older adults: An integrative review. Annu. Rev. Nurs. Res. 2016, 34, 155–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploug, T.; Holm, S. The right to refuse diagnostics and treatment planning by artificial intelligence. Med. Health Care Philos. 2020, 23, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachman, M.E.; Weaver, S.L. The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Gupta, S.; Rosson, M.B.; Carroll, J.M. Measuring mobile users’ concerns for information privacy. In Proceedings of the Thirty Third International Conference on Information Systems, Orlando, FL, USA, 16–19 December 2012; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, D.L.; Bitman, R.L.; Hammer, J.H.; Wade, N.G. Is stigma internalized? The longitudinal impact of public stigma on self-stigma. J. Couns. Psychol. 2013, 60, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, M.-Y.; Pai, F.-Y.; Yeh, T.-M. Antecedents for Older Adults’ Intention to Use Smart Health Wearable Devices-Technology Anxiety as a Moderator. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.S.; Wu, S.; Tsai, R.J. Integrating perceived playfulness into expectation-confirmation model for web portal context. Inf. Manag. 2005, 42, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbanufe, O.; Gerhart, N. Exploring smart wearables through the lens of reactance theory: Linking values, social influence, and status quo. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 127, 107044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C. Artificial Intelligence in FinTech: Understanding robo-advisors adoption among customers. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2019, 119, 1411–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristea, M.; Noja, G.G.; Stefea, P.; Sala, A.L. The impact of population aging and public health support on EU labor markets. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, H.; Iqbal, S.; Akhtar, S. Exploring predictors of innovation performance of SMEs: A PLS-SEM approach. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2023, 45, 909–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.-H.; Tsai, J.-F.; Lin, M.-H.; Hu, Y.-C. A hybrid model with spherical fuzzy-ahp, pls-sem and ann to predict vaccination intention against COVID-19. Mathematics 2021, 9, 3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N. Detecting multicollinearity in regression analysis. Am. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 2020, 8, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, A.S.; Enz, C.A. The role of emotions in service encounters. J. Serv. Res. 2002, 4, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Thatcher, J.B.; Wright, R.T. Assessing common method bias: Problems with the ULMC technique. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 1003–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Etemad-Sajadi, R.; Gomes Dos Santos, G. Senior citizens’ acceptance of connected health technologies in their homes. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2019, 32, 1162–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essén, A. The two facets of electronic care surveillance: An exploration of the views of older people who live with monitoring devices. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudrie, J.; Junior, C.-O.; McKenna, B.; Richter, S. Understanding and conceptualising the adoption, use and diffusion of mobile banking in older adults: A research agenda and conceptual framework. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 88, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Kartajaya, H.; Setiawan, I. Marketing 5.0: Technology for Humanity; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nimrod, G. Technostress: Measuring a new threat to well-being in later life. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 1086–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, G.; Ugolini, M.M.; Sestino, A. Active ageing of elderly consumers: Insights and opportunities for future business strategies. SN Bus. Econ. 2022, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschis, G.P. Consumer behavior in later life: Current knowledge, issues, and new directions for research. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Objects | Research Subjects | Negative Effects | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ICT and older people | The impact of digital participation on the quality of life of older people | Perceived control; feelings of shame; privacy disclosure; social isolation | [28] |

| 2 | AI | The ethical issues of geriatric technology in elderly care | Discrimination; dehumanization | [5] |

| 3 | AI and IoT | The influence of AI on life assistance and health monitoring of older people | Perceived control; perceived intrusiveness | [23] |

| 4 | AI | Opportunities and challenges | Prejudice; discrimination | [6] |

| 5 | AI and expert systems | Expectations of AI | Expectation disconfirmation | [29] |

| 6 | Virtual personal assistant | Active aging | Perceived intrusiveness | [30] |

| 7 | AI and robotics | Lessons from intelligent products for older people | Non-availability; emotional reaction; discrimination; loss of autonomy | [31] |

| 8 | AI | Aging in place | Perceived control; non-availability; lack of technical literacy | [32] |

| 9 | Intelligent wearable system | Status and challenges | Stigma; feelings of shame; perceived intrusiveness | [33] |

| 10 | Intelligent assistive technology | The emotional experiences and attitudes | Perceived control; lack of literacy; stigma; feelings of shame | [15] |

| 11 | Geriatric technology | Reasons for negative behavior of older people | Social isolation; addiction | [34] |

| 12 | Geriatric technology | The acceptance of geriatric technology | Technology anxiety | [35] |

| 13 | Assistive equipment | The ethical discussion of technologies in the community | Stigma; feelings of shame; private anxiety; perceived control; perceived intrusiveness | [36] |

| 14 | Autonomous vehicles | External and internal factors for acceptance | Stigma; stereotype | [37] |

| 15 | Wearable devices and sensors | Quantified self | Stigma; feelings of shame; perceived control | [38] |

| 16 | Advanced technology (AI and robotics) | Psychological barriers to digital society | Technology anxiety | [39] |

| 17 | Assistive technology | Barriers to technology adoption | Perceived uselessness; stigma; not being independent | [4] |

| Variable | Measurement Items | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived Control | PC1: I feel like I’m losing the territory that I used to control. | [58] |

| PC2: I feel like I lack control over the outside world (other people, situations). | ||

| PC3: I can set clear, realistic, and meaningful goals. | ||

| PC4: Something (human or machine) exerts too much control over me. | ||

| Perceived Intrusiveness | PI1: I am concerned that AIPs are collecting too much information about me. | [59] |

| PI2: I feel that as a result of my using an AIP, others know about me more than I am comfortable with. | ||

| PI3: I believe that as a result of my using an AIP, information about me that I consider private is now more readily available to others than I would want. | ||

| PI4: I feel that as a result of my using an AIP, information about me is out there that, if used, will invade my privacy. | ||

| Self-Stigma | SS1: It makes me feel inferior to use an AIP. | [60] |

| SS2: When I use an AIP, my view of myself is more negative. | ||

| SS3: My self-image feels threatened when I use an AIP. | ||

| SS4: Using an AIP makes me feel like there is something wrong with me. | ||

| Public Stigma | PS1: Using an AIP carries a social stigma. | |

| PS2: It is a sign of weakness and aging to use an AIP. | ||

| PS3: People tend to like others less when those others are using an AIP. | ||

| PS4: It is advisable for me to hide that I use an AIP. | ||

| Socio-emotional Mismatch | SM1: AIPs cannot satisfy my emotional needs. | [15] |

| SM2: AIPs cannot match my emotional needs. | ||

| SM3: I cannot say that AIPs please me. | ||

| SM4: AIPs have no positive impact on my affection. | ||

| Functional Mismatch | FM1: AIPs can not meet my daily needs. | |

| FM2: AIPs don’t fit my daily needs. | ||

| FM3: I cannot say that AIPs help me in my life. | ||

| FM4: AIPs have not changed my life. | ||

| Expectation Disconfirmation | ED1: My experience with using the AIP was worse than what I expected. | [62] |

| ED2: The service level provided by the AIP was worse than what I expected. | ||

| ED3: Overall, most of my expectations about using the AIP were not confirmed. | ||

| Technology Anxiety | TA1: I feel stressed when I use a new AIP. | [61] |

| TA2: I am worried that the new AIP will affect my life. | ||

| TA3: I fear that AIPs will change my life. | ||

| TA4: I’m afraid that I don’t have enough ability to use AIPs. | ||

| Avoidance Behavior | AB1: The transition to AIPs is stressful for me. | [63] |

| AB2: I feel comfortable not continuing to use AIPs. | ||

| AB3: I like using the original product instead of AIPs. | ||

| Exit Behavior | EB1: I won’t be using the AIPs as much as I used to. | |

| EB2: After using an AIP for a while, my interest in continuing to use it gradually decreases. | ||

| EB3: I’m going to stop using my AIPs, but that doesn’t mean I’m going to give them up altogether. |

| Measure | Item | Count |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 55–59 | 212 (19.24%) |

| 60–69 | 515 (46.73%) | |

| 70–79 | 237 (21.50%) | |

| >80 | 138 (12.53%) | |

| Gender | Male | 585 (53.09%) |

| Female | 517 (46.91%) | |

| Education | Primary school | 116 (10.53%) |

| Junior middle school | 477 (43.28%) | |

| High school | 353 (32.03%) | |

| Undergraduate | 156 (14.16%) | |

| AI used (multi-choice) | Healthy | 670 (60.80%) |

| Accompanied | 784 (71.14%) | |

| Monitored | 836 (78.86%) | |

| Walking-aided | 539 (48.91%) |

| Index | Value | HI95 | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| SRMR | 0.034 | 0.133 | Support |

| d_ULS | 0.828 | 12.439 | Support |

| d_G | 0.59 | 0.938 | Support |

| Construct | Item | Loading | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Function Mismatch | FM1 | 0.941 | 0.944 | 0.960 | 0.857 |

| FM2 | 0.941 | ||||

| FM3 | 0.943 | ||||

| FM4 | 0.877 | ||||

| Avoidance Behavior | AB1 | 0.897 | 0.908 | 0.942 | 0.845 |

| AB2 | 0.939 | ||||

| AB3 | 0.922 | ||||

| Socio-emotion Mismatch | SM1 | 0.928 | 0.962 | 0.972 | 0.898 |

| SM2 | 0.960 | ||||

| SM3 | 0.954 | ||||

| SM4 | 0.947 | ||||

| Technology Anxiety | TA1 | 0.921 | 0.934 | 0.953 | 0.835 |

| TA2 | 0.905 | ||||

| TA3 | 0.912 | ||||

| TA4 | 0.917 | ||||

| Expectation Disconfirmation | ED1 | 0.857 | 0.861 | 0.916 | 0.783 |

| ED2 | 0.912 | ||||

| ED3 | 0.885 | ||||

| Public Stigma | PS1 | 0.949 | 0.960 | 0.971 | 0.892 |

| PS2 | 0.949 | ||||

| PS3 | 0.960 | ||||

| PS4 | 0.920 | ||||

| Perceived Intrusiveness | PI1 | 0.779 | 0.884 | 0.920 | 0.743 |

| PI2 | 0.869 | ||||

| PI3 | 0.898 | ||||

| PI4 | 0.897 | ||||

| Perceived Control | PC1 | 0.918 | 0.950 | 0.964 | 0.869 |

| PC2 | 0.928 | ||||

| PC3 | 0.948 | ||||

| PC4 | 0.935 | ||||

| Self-stigma | SS1 | 0.925 | 0.947 | 0.962 | 0.863 |

| SS2 | 0.936 | ||||

| SS3 | 0.920 | ||||

| SS4 | 0.935 | ||||

| Exit Behavior | EB1 | 0.797 | 0.827 | 0.897 | 0.744 |

| EB2 | 0.886 | ||||

| EB3 | 0.902 |

| FM | AB | SM | TA | ED | PS | PI | PC | SS | EB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FM | 0.926 | |||||||||

| AB | 0.625 | 0.919 | ||||||||

| SM | 0.851 | 0.617 | 0.947 | |||||||

| TA | 0.610 | 0.556 | 0.627 | 0.914 | ||||||

| ED | 0.581 | 0.538 | 0.521 | 0.459 | 0.885 | |||||

| PS | 0.777 | 0.616 | 0.750 | 0.697 | 0.541 | 0.945 | ||||

| PI | 0.511 | 0.506 | 0.471 | 0.502 | 0.769 | 0.510 | 0.862 | |||

| PC | 0.600 | 0.567 | 0.555 | 0.516 | 0.754 | 0.574 | 0.707 | 0.932 | ||

| SS | 0.602 | 0.595 | 0.554 | 0.534 | 0.723 | 0.572 | 0.677 | 0.842 | 0.929 | |

| EB | 0.688 | 0.558 | 0.605 | 0.452 | 0.519 | 0.645 | 0.457 | 0.540 | 0.537 | 0.863 |

| FM | AB | SM | TA | ED | PS | PI | PC | SS | EB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FM | ||||||||||

| AB | 0.675 | |||||||||

| SM | 0.842 | 0.660 | ||||||||

| TA | 0.644 | 0.599 | 0.655 | |||||||

| ED | 0.644 | 0.608 | 0.572 | 0.510 | ||||||

| PS | 0.816 | 0.660 | 0.780 | 0.728 | 0.595 | |||||

| PI | 0.555 | 0.563 | 0.507 | 0.549 | 0.829 | 0.551 | ||||

| PC | 0.634 | 0.610 | 0.580 | 0.545 | 0.834 | 0.601 | 0.767 | |||

| SS | 0.636 | 0.641 | 0.580 | 0.565 | 0.801 | 0.599 | 0.734 | 0.837 | ||

| EB | 0.779 | 0.647 | 0.678 | 0.512 | 0.616 | 0.724 | 0.534 | 0.610 | 0.608 |

| Hypotheses | Path Coefficient | T Value | p-Value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: PI -> FM | 0.043 | 1.02 | 0.307 | No support |

| H2: PC -> FM | 0.363 | 7.842 | <0.001 | Support |

| H3: ED -> FM | 0.275 | 6.071 | <0.001 | Support |

| H4: SS -> SM | 0.154 | 4.441 | <0.001 | Support |

| H5: PS ->SM | 0.549 | 12.610 | <0.001 | Support |

| H6: TA -> SM | 0.162 | 3.544 | 0.001 | Support |

| H7: FM -> AB | 0.363 | 5.683 | <0.001 | Support |

| H8: FM -> EB | 0.630 | 12.237 | <0.001 | Support |

| H9: SM -> AB | 0.308 | 4.902 | <0.001 | Support |

| H10: SM -> EB | 0.069 | 1.307 | 0.191 | No support |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hong, W.; Liang, C.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, J. Why Do Older Adults Feel Negatively about Artificial Intelligence Products? An Empirical Study Based on the Perspectives of Mismatches. Systems 2023, 11, 551. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11110551

Hong W, Liang C, Ma Y, Zhu J. Why Do Older Adults Feel Negatively about Artificial Intelligence Products? An Empirical Study Based on the Perspectives of Mismatches. Systems. 2023; 11(11):551. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11110551

Chicago/Turabian StyleHong, Wenjia, Changyong Liang, Yiming Ma, and Junhong Zhu. 2023. "Why Do Older Adults Feel Negatively about Artificial Intelligence Products? An Empirical Study Based on the Perspectives of Mismatches" Systems 11, no. 11: 551. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11110551

APA StyleHong, W., Liang, C., Ma, Y., & Zhu, J. (2023). Why Do Older Adults Feel Negatively about Artificial Intelligence Products? An Empirical Study Based on the Perspectives of Mismatches. Systems, 11(11), 551. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11110551