Tackling the Design of Platform-Based Service Systems, Integrating Data and Cultures: The Case of Urban Markets

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Background

2.1. The Different Cultural Traditions That Approach the Design of Services

2.2. Service Design and Platform Design Applied to Services

2.3. Urban Markets and Their Design

2.4. Complexity of Urban Market Services and (Two-Sided) Platform Dynamics

- Urban markets are distributed over an urban area. This requires a study of the service system at two levels: the single market itself as a retail platform and the entire network of markets in the city, where each market embodies one interface within a multi-interface service system. Consequently, hierarchical modeling of the service and the study of the system architecture are critical. For the former issue, even in retail contexts where interaction and organizational issues still remain central, SDL can be helpful [50]; for the latter, System Engineering can provide a valuable aid. These approaches clearly belong to cells 1–2 in Figure 2.

- Urban markets embody a two-sided platform, for which two distinct groups (i.e., retailers and consumers) provide each other with utility and externalities as a result of participating in the platform. There is ample literature on two-sided platforms (e.g., [85,86]), which however are mainly concerned with ICT services (e.g., Uber, Airbnb, or Amazon). Platforms nowadays have become extremely relevant because of their economic value and since their tendency to follow a winner-take-all strategy, which ultimately leads to monopoly. This usually occurs when network externalities are strong, the costs of participating to multiple platforms are high and differentiation between platforms is low [86].

- Urban markets are iconic, since they are a physical platform with strong network externalities, low costs of participating to multiple platforms and specific differentiation mechanisms). This nature of this economic platform requires studying those variables that govern the system dynamics and which affect the service value, as SDL suggests ([27,28,29,30], located in cell 1 in Figure 2). A single focus by designers on experiential and intangible service dimensions, neglecting the economics of the system, would lead to misleading design actions.

- Urban markets, different from other ICT-platforms for retail, propose a purchasing experience in which consumers physically visit the retail outlet, without a multi-channel configuration. In this sense, they differ from other cases in the literature (e.g., [87]) and instead face different issues: a sufficiently large city, in fact, will host a network of markets; this distribution of markets in the urban territory ensures service coverage to customers, but provokes intra-channel competition within the single market and among markets in the city, as well as inter-channel competition with shops and supermarkets.

- In some countries, such as Italy, the choice of where to operate in a market is left free on a daily basis to retailers, who may consider it more or less convenient to sell in a specific area. This autonomous choice determines the daily market assortment, and presents a different chance for each market to face competition.

- Market areas are public, and municipalities aim to ensure service coverage in the urban territory, avoiding underserved districts or boroughs, both in terms of the presence of markets and for assortment completeness. Municipalities exert their administrative power to provide the physical platform within which markets operate (i.e., the market area) and commercial licenses, which grant market retailers with the right to sell a given commodity in a public market area (depending on the local regulations, the right to occupy a specific stall place in a given market and on a given day). However, retailers can give up their rights on the basis of personal considerations (e.g., in some cases depending on the day, and due to weather). Therefore, the license mechanism often results in being unable to plan and confirm regular service coverage in each market area within a city.

- 2.

- Finally, the attractiveness of a market depends on its value proposition that attracts consumer traffic inside the market. This depends on assortments (which, as previously mentioned, is definitively defined by the number of stalls selling each commodity), on its quality, on expectations, and emotional aspects, or on the social relations that each market fosters among its participants. These elements are again dependent on the behavior of individual retailers that decide what they will offer, and are also influenced by the same-side effects typical of economic platforms. Each retailer in a market, for instance, also has to cope with the opportunistic behaviors of unpleasant colleagues (e.g., not complying with opening hours, neglecting stall appearance of the goods on display, etc.), which damage the attractiveness of the market.

3. Aiming at an Integrated View of the Design of Service Systems

3.1. Emergent Issues

- An analytical study of the variables that govern service economics (Figure 3, cell 1);

- A rigorous study of the system architecture and processes, especially in view of interactions and experiences (Figure 3, cell 2);

- A participatory approach to cope with the multi-stakeholder/public nature (Figure 3, cells 3–4).

3.2. The Methodological Proposal and Its Founding Roots

- At the encounter level: here, economic, transactional, and functional aspects are not only studied to perform an effective design action, but also to activate the participatory process. User needs and encounter processes in the service system can be investigated through more traditional (focus groups and questionnaires, customer journeys, etc.) or novel (field data analysis, if using digital platforms) methods; however, the functioning mechanisms and underlying economics must be thoroughly analyzed through systematic and empirical approaches, to then be shared to stakeholders, to increase awareness, and to build a common vision regarding the design problem.

- At the system architecture level: a platform-based approach is suggested for the design of the architecture to find a balance between flexibility and differentiation. This might be even more useful for designing digital services, where personalization/customization are key drivers. However, these methods are not in contrast to the aim of adopting participatory approaches. Given the simplicity of the concept of modularity, they can be used to structure the enquired data and to discuss the alternatives with stakeholders [93], formulating a “platform for action” by which to enact the co-design processes [94].

- At the value constellation level: the different value constellation alternatives can be generated from the combination of modules, to be put either inside or outside of the previously defined platform. Generally, the main design issue for multi-interface systems is caused by the coherence and coordination among the service interfaces [48]. In this case, the coordination of the service alternatives is particularly relevant to address differentiation, and the platform-based design ensures coherence. At the level of the service system, again, the use of platform methods helps in the formulation of design choices and the negotiation/sharing processes with stakeholders.

4. The Case Study

4.1. The Market Service System in Turin

4.2. The Design Process to Reach the Design of the Entire Value Constellation

- A total of 26 markets out of 42 had significant problems in service delivery (16 markets had a saturation <50% of the total allocated space, and 10 markets achieved less than 30%);

- The market size effectively represented a structural variable dominating attractiveness: the larger markets attracted more customers than the smaller ones, and vice versa, confirming their two-sided nature (Figure A1 and Figure A2 in Appendix A);

- The markets’ offerings were quite haphazardly distributed throughout the city, often with adjacent markets sharing the same offering (e.g., markets with “clothes and fabric” were concentrated in the city center, see Figure 6b).

- Market size was due to the allocation mechanism that influenced the retailers’ location choices. The principle of giving retailers freedom to choose where to locate themselves led them to move to where they perceived they would gain more. As an outcome, the municipality’s service coverage goal was not being achieved;

- Customer experience was affected by poorer vs. richer configurations. Again, the Municipality’s objective of ensuring a good service experience in each of the city’s markets was not met;

- More interventionistic approaches to allocate retailers to markets with the aim of improving market coverage would have implied a complex effect on market size and, as a consequence, on attractiveness.

- Despite the freedom they had to locate anywhere they wanted, the interdependence of their behaviors was affecting the dynamics of the system. The allocative mechanism that seemed to give them freedom was actually generating distorted dynamics that damaged the entire market service;

- An unevenly distributed service in the urban territory was generating both an inadequate service coverage for customers (thus weakening markets with respect to inter-channel competition from supermarkets and shopping centers) and distorted intra-channel competition on the supply side.

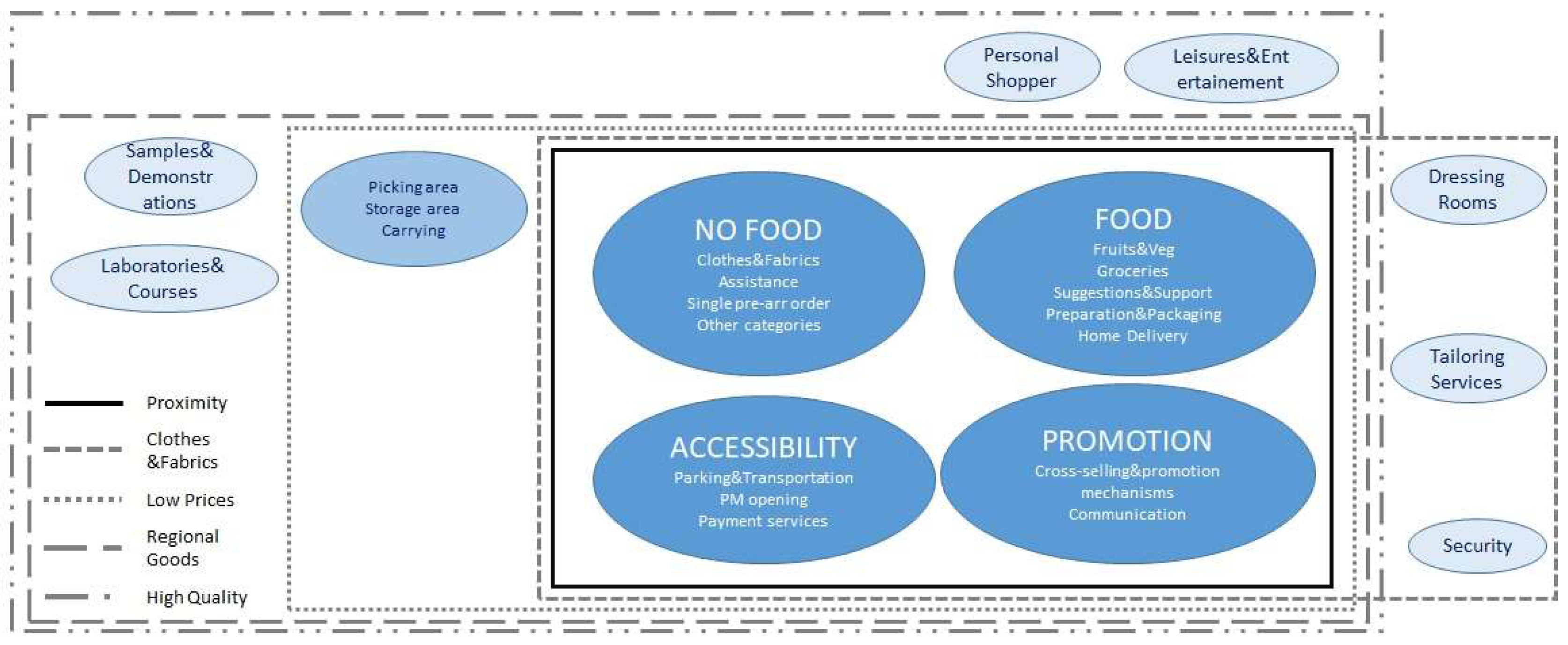

- Food: Fruits and vegetables, Grocery, Preparation and packing, Support to the final purchasing decision, Home delivery;

- Non-Food: Clothes and fabrics, Other categories, Assistance during purchasing, Single pre-arranged orders.

- An ‘accessibility’ module, including home delivery, e-commerce, and free parking areas;

- A ‘usability’ module, including services for collecting, carrying, and storing goods;

- A ‘promotion’ module designed to improve the basic pleasantness of the setting, communication, and the trusting relationship between the retailers and the customers;

- A ‘specific services’ module designed to improve the emotions/atmosphere within the market. This same module also dealt with security, entertainment (e.g., laboratories and courses), and leisure activities (e.g., places for eating).

- The risk of cannibalization by adjacent markets providing similar customer experience;

- The structural and environmental conditions;

- The capacity constraints, efficiency issues, and retailers’ availability to relocate.

5. Discussion of the Results and Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Age | Males | Females | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15–24 | 15 | 20 | 35 |

| 25–44 | 22 | 26 | 48 |

| 44–64 | 18 | 27 | 45 |

| 65+ | 4 | 19 | 23 |

| Total | 59 | 92 | 151 |

| Macro Categories | Second Order Themes |

|---|---|

| Product | product quality (1), food products (2), apparel (3), household products (4), assortment width (5) and length (6), product warranty and authenticity |

| Service | price advantage (8), loyalty and trust with the merchant (9), usability (10), opening time flexibility (11), speed of purchases (12), Tradition (15) |

| Market Setting | Amusement and leisure (13), accessibility (14), parking (16), safety (17), cleanliness (18), protection from the elements (19), Familiarity and social place (20) |

Appendix C

| Age | 15–24 | 25–44 | 45–64 | 65+ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | Total | |

| District of residence | 1 | 6 | 8 | 22 | 24 | 16 | 17 | 20 | 7 | 120 |

| 2 | 10 | 10 | 21 | 24 | 39 | 20 | 16 | 18 | 158 | |

| 3 | 14 | 15 | 54 | 39 | 45 | 27 | 28 | 18 | 240 | |

| 4 | 6 | 10 | 24 | 18 | 17 | 15 | 13 | 9 | 112 | |

| 5 | 14 | 11 | 17 | 24 | 30 | 22 | 20 | 16 | 154 | |

| 6 | 12 | 14 | 21 | 23 | 33 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 151 | |

| 7 | 8 | 11 | 21 | 21 | 15 | 10 | 15 | 8 | 109 | |

| 8 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 16 | 6 | 17 | 6 | 64 | |

| 9 | 5 | 5 | 19 | 20 | 24 | 23 | 21 | 16 | 133 | |

| 10 | 4 | 4 | 12 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 13 | 10 | 74 | |

| Total | 82 | 95 | 216 | 207 | 246 | 167 | 179 | 123 | 1315 | |

Appendix D

Appendix E

| 1 | For reasons of focus and length, the paper does not discuss the transformative aspects of the design process (cell 4). |

References

- Kimbell, L. Designing for service as one way of designing services. Int. J. Des. 2011, 5, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mele, C.; Colurcio, M.; Russo-Spena, T. Research traditions of innovation: Goods-dominant logic, the resource-based approach, and service-dominant logic. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2014, 24, 612–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, A.L.; Parasuraman, A.; Bowen, D.; Patrício, L.; Voss, C.A. Service Research Priorities in a Rapidly Changing Context. J. Serv. Res. 2015, 18, 127–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.P.; Menor, L.J.; Roth, A.V.; Chase, R.B. New Service Development: Creating Memorable Experiences. In A Critical Evaluation of the New Service Development Process: Integrating Service Innovation and Service Design; Fitzsimmons, J.A., Fitzsimmons, M.J., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wetter-Edman, K.; Sangiorgi, D.; Edvardsson, B.; Holmlid, S.; Grönroos, C.; Mattelmäki, T. Design for Value Co-Creation: Exploring Synergies Between Design for Service and Service Logic. Serv. Sci. 2014, 6, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrício, L.; Gustafsson, A.; Fisk, R.P. Upframing Service Design and Innovation for Research Impact. J. Serv. Res. 2017, 21, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karpen, I.O.; Gemser, G.; Calabretta, G. A multilevel consideration of service design conditions: Towards a portfolio of organisational capabilities, interactive practices and individual abilities. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2017, 27, 384–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, R.B. It’s time to get to first principles in service design. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2004, 14, 126–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; Kim, M.; Kim, K.; Kim, K.; Maglio, P.P. Using data to advance service: Managerial issues and theoretical implications from action research. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2009, 28, 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schallehn, H.; Seuring, S.; Strähle, J.; Freise, M. Defining the antecedents of experience co-creation as applied to alternative consumption models. J. Serv. Manag. 2019, 30, 209–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, I.R.; Hannibal, C.; Keating, B.W.; Chester Buxton, R.; Bateman, N. Toward a public service management: Past, present, and future directions. J. Serv. Manag. 2017, 28, 998–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad-Sulonen, J.; de Götzen, A.; Morelli, N.; Simeone, L. Service design and participatory design: Time to join forces? In Proceedings of the 16th Participatory Design Conference, Manizales, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2020; Volume 2, pp. 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, M. Design and Manufacture for Sustainable Development. In Understanding the Potential Opportunities Provided by Service-Orientated Concepts to Improve Resource Productivity; Bhamra, T., Hon, B., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Aas, T.H.; Breunig, K.J.; Hellström, M.; Hydle, K. Service-oriented business models in manufacturing in the digital era: Toward a new taxonomy. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 24, 2040002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ostaeyen, J.; Van Horenbeek, A.; Pintelon, L.; Duflou, J.R. A refined typology of Product-Service Systems based on Functional Hierarchy Modelling. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 51, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Yoon, B. Developing a process of concept generation for new product-service systems: A QFD and TRIZ-based approach. Serv. Bus. 2012, 6, 323–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mont, O.K. Clarifying the concept of product–service system. J. Clean. Prod. 2002, 10, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzacott, J.A. Service system structure. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2002, 68, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FIVA Confcommercio. Le Dinamiche del Commercio Ambulante e Su Aree Pubbliche Nell’ultimo Quadriennio. In Proceedings of the XIV FIVA Conference, Venice, Italy, 16 November 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Magarini, A.; Porreca, E. European Cities Leading in Urban Food Systems Transformation: Connecting Milan & FOOD 2030; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mont, O.K. What is behind meagre attempts to sustainable consumption? Institutional and product-service systems perspective. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Driving Forces and Barriers to Sustainable Consumption, Leeds, UK, 5–6 March 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. Counting Farmers markets. Geogr. Rev. 2011, 91, 655–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, A. Marketplaces: Prospects for Social, Economic, and Political Development. J. Plan. Lit. 2011, 26, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menor, L.J.; Tatikonda, M.V.; Sampson, S.E. New service development: Areas for exploitation and exploration. J. Oper. Manag. 2002, 20, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gremyr, L.; Witell, L.; Löfberg, N.; Edvardsson, B.; Fundin, A. Understanding new service development and service innovation through innovation modes. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2014, 29, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sampson, S.E.; Froehle, C.M. Foundations ad Implications of a Proposed Unified Service Theory. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2006, 15, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwortnik, R.J., Jr.; Thompson, G.M. Unifying service marketing and operations with service experience management. J. Serv. Res. 2009, 11, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R.F.; Vargo, S.L. Service Dominant Logic: Reactions, Reflections, and Refinements. Mark. Theory 2006, 6, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R.F.; Vargo, S.L. Service-Dominant Logic: Premises, Perspectives, Possibilities; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing’. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.M.; Fischbacher, M. New service development: A stakeholder perspective. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 1025–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, I.; Perry, C. A Customer-Oriented New Service Development Process. J. Serv. Mark. 2002, 16, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matthing, J.; Sandén, B.; Edvardsson, B. New Service Development Learning from and with Customers. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2004, 15, 479–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvardsson, B.; Gustafsson, A.; Kristensson, P.; Magnusson, P.; Matthing, J. (Eds.) Involving Customers in New Service Development; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Froehle, C.M.; Roth, A.V.; Chase, R.B.; Voss, C.A. Antecedents of new service development effectiveness an exploratory examination of strategic operations choices. J. Serv. Res. 2000, 3, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roth, A.V.; Menor, L.J. Insights into Service Operations Management: A Research Agenda. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2003, 12, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heineke, J.; Davis, M.M. The Emergence of Service Operations Management as an Academic Discipline. J. Oper. Manag. 2007, 25, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.T.H.; Hofer, K.M. Service innovation and usage intention: A cross-market analysis. J. Serv. Manag. 2015, 26, 516–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.C. Systems Thinking: Creative Holism for Managers; John Wiley & Sons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tansik, D.A.; Smith, W.L. Scripting the Service Encounter, in New Service Design; Fitzsimmons, J.A., Fitzsimmons, M.J., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 239–263. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, L.S.; Bowen, D.E.; Chase, R.B.; Dasu, S.; Stewart, D.M.; Tansik, D.A. Human Issues in Service Design. J. Oper. Manag. 2002, 20, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwinner, K.P.; Bitner, M.J.; Brown, S.W.; Kumar, A. Service Customization through Employee Adaptiveness. J. Serv. Res. 2005, 8, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantine, L.L.; Lockwood, L.A.D. Usage-Centered Engineering for Web Applications. IEEE Softw. 2002, 19, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Vajic, M. The Contextual and Dialectical Nature of Experiences, in New Service Development: Creating Memorable Experiences; Fitzsimmons, J.A., Fitzsimmons, M.J., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Pullman, M.E.; Gross, M.A. Ability of Experience Design Elements to Elicit Emotions and Loyalty Behaviors. Decis. Sci. 2004, 35, 551–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, C.; Spiller, N.; Noci, G. How to Sustain the Customer Experience: An Overview of Experience Components that Co-Create Value with the Customer. Eur. Manag. J. 2007, 25, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrício, L.; Fisk, R.P.; Falcão E Cunha, J. Designing Multi-Interface Service Experiences: The Service Experience Blueprint. J. Serv. Res. 2008, 10, 318–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zomerdijk, L.G.; Voss, C.A. Service Design for Experience-Centric Services. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrício, L.; Fisk, R.P.; Falcão E Cunha, J.; Constantine, L. Multilevel Service Design: From Customer Value Constellation to Service Experience Blueprinting. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 180–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltas, G.; Tsafarakis, S.; Saridakis, C.; Matsatsinis, N. Biologically Inspired Approaches to Strategic Service Design: Optimal Service Diversification Through Evolutionary and Swarm Intelligence Models. J. Serv. Res. 2012, 16, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjögvinsson, E.; Ehn, P.; Hillgren, P.-A. Design Things and Design Thinking: Contemporary Participatory Design Challenges. Des. Issues 2012, 28, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meroni, A.; Sangiorgi, D. Design for Services; Gower Publishing: Aldershot, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kimbell, L.; Seidel, V. Designing for services—Multidisciplinary perspectives. In Proceedings from the Exploratory Project on Designing for Services in Science and Technology-Based Enterprises; Saïd Business School: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Garud, R.; Sanjay, J.; Tuertscher, F. Incomplete by Design and Designing for Incompleteness. Organ. Stud. 2008, 29, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burns, C.; Cottam, H.; Vanstone, C.; Winhall, J. Transformation Design; Design Council: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sangiorgi, D. Transformative services and transformation design. Int. J. Des. 2011, 5, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Brax, S.A.; Bask, A.; Hsuan, J.; Voss, C. Service modularity and architecture—An overview and research agenda. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2017, 37, 686–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bask, A.; Lipponen, M.; Rajahond, M.; Tinnila, M. The concept of modularity: Diffusion from manufacturing to service production. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2010, 21, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, T.W.; Siddique, Z.; Jiao, J. Product Platform and Product Family Design: Methods and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, M.H.; Jekowsky, E.; Crane, F.G. Applying platform design to improve the integration of patient services across the continuum of care. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2007, 17, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajahonka, M. Views of logistics service providers on modularity in logistics services. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2013, 16, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestro, R.; Lustrato, P. Exploring the “mid office” concept as an enabler of mass customization in services. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2015, 35, 866–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyötyläinen, M.; Möller, K. Service packaging: Key to successful provisioning of ICT business solutions. J. Serv. Mark. 2007, 21, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.H.; DeTore, A. Perspective: Creating a Platform-Based Approach for Developing New Services. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2001, 18, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuunanen, T.; Cassab, H. Service Process Modularization: Reuse Versus Variation in Service Extensions. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, M.; Pentek, T.; Otto, B. Design principles for Industry 4.0 scenarios. In Proceedings of the IEEE 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Koloa, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2016; pp. 3928–3937. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, J.; Crainic, T.G.; Christiansen, M. Service network design with management and coordination of multiple fleets. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 193, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crainic, T.G. Service network design in freight transportation. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2000, 122, 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.F.; Lo, H.K. Ferry service network design: Optimal fleet size, routing, and scheduling. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2004, 38, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenberger, M.A. Project-Level Reuse Factors: Drivers for Variation within Software Development Environments. Decis. Sci. 2003, 34, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.H.; Lehnred, A.P. The Power of Product Platforms; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Heese, H.S.; Swaminathan, J.M. Product Line Design with Component Commonality and Cost-Reduction Effort. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2006, 8, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farrell, R.S.; Simpson, T.W. Improving Cost Effectiveness in an Existing Product Line Using Component Product Platforms. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2009, 48, 3299–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairoch, P.; Braider, C. Cities and Economic Development: From the Dawn of History to the Present; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bromley, R.D.F. Market-place Trading and the Transformation of Retail Space in the Expanding Latin American City. Urban Stud. 1998, 35, 1311–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutebi, A.M.; Ansari, R. Small Independent Merchants and Transnational Retail Encounters on Main Street: Some Insights from Bangkok. Urban Stud. 2008, 45, 2689–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.S.; Loukaitou-Sideris, A. Sidewalk Informality: An Examination of Street Vending Regulation in China. Int. Plan. Stud. 2014, 19, 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Hillier, D.; Comfort, D. Changing times and changing places for market halls and covered markets. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2007, 35, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolla, C.; Moura, H. Social Innovation in Brazil Through Design Strategy. Des. Manag. J. 2011, 6, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, R. Street vending and public policy: A global review. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2000, 20, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.R. Managing the Retail Format Portfolio: An Application of Modern Portfolio Theory. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2010, 17, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runyan, R.C.; Droge, C. A categorization of small retailer research streams: What does it portend for future research? J. Retail. 2008, 84, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkin, S.; Morales, A. www.openair.org: Linking street vendors to the Internet. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2000, 20, 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rysman, M. Economics of Two-Sided Markets. J. Econ. Perspect. 2009, 23, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eisenmann, T.; Parker, G.; Van Alstyne, M.V. Strategies for Two-Sided Markets. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Neslin, S.A.; Grewal, D.; Leghorn, R.; Shankar, V.; Teerling, M.L.; Thomas, J.S.; Verhoef, P.C. Challenges and Opportunities in Multi-channel Customer Management. J. Serv. Res. 2006, 9, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekkarinen, S.; Ulkuniemi, P. Modularity in developing business services by platform approach. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2008, 19, 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, J.M.; Fotheringham, D.; Subramony, M.; Gustafsson, A.; Ostrom, A.L.; Lemon, K.N.; McColl-Kennedy, J.R. Service Research Priorities: Designing Sustainable Service Ecosystems. J. Serv. Res. 2021, 24, 462–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, K.; Eppinger, S. Product Design and Development; McGrawHill: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Maglio, P.P.; Akaka, M.A. On value and value co-creation: A service systems and service logic perspective. Eur. Manag. J. 2008, 26, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Institutions and axioms: An extension and update of service-dominant logic. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Yu, S.; Wanga, Y.; Zhonga, R.Y.; Xun, X. User-experience based product development for mass personalization: A case study. Procedia CIRP 2017, 63, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubberly, H.; Evenson, S.; Robinson, R. The Analysis-Synthesis Bridge Model. Interactions 2008, 15, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formicola, L. Luce Su Porta Palazzo: Il Mercato Che non Si Spegne Mai; Conservatoria delle Cucine Mediterranee: Piemonte, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cross River Partnership, Sustainable Urban Markets, An Action Plan for London City. 2014. Available online: https://crossriverpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Sustainable-Urban-Markets-An-Action-Plan-for-London3.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- Eppinger, S.D. A planning method for integration of large-scale engineering systems. In Proceedings of the ICED Conference, Tampere, Finland, 19–21 August 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lanner, P.; Malmqvist, J. An Approach Towards Considering Technical and Economic Aspects in Product Architecture Design. In Proceedings of the 2nd WDK Workshop on Product Structuring, Delft, The Netherlands, 3–4 June 1996. [Google Scholar]

| Requirements from the System’s Economics | Requirements from Stakeholders | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality | Retailers | Customers | |

| (to investigate): service system from a hierarchical perspective | (constraint): multi-stakeholder, negotiating environment, subject to political tensions | ||

| (to investigate): agglomeration phenomena, same-side and cross-side externalities, typical of two-sided platforms (constraint): attractiveness of each market depends on assortment decided by independent economic actors, but it had an impact on the customers’ interest | (to ensure): service coverage and assortment completeness (constraint): the adopted license mechanism | (constraint): retailers are independent economic actors and not passive agents of the public service | (constraint): customer experience, in a similar way to shopping malls, is affected by agglomeration (poorer vs. richer configurations) |

| (to ensure): service coverage in an intra-channel and extra-channel competition environment | |||

| (to ensure): physical purchasing experience, without a multi-channel configuration | |||

| Factor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usability | Safety | Product Range | Convenience | |

| Product Quality | −0.008 | 0.693 | 0.195 | −0.067 |

| Assortment Width | 0.160 | −0.142 | 0.649 | 0.055 |

| Assortment Depth | 0.073 | 0.167 | 0.666 | 0.191 |

| Service Efficiency | 0.530 | 0.139 | −0.195 | 0.280 |

| Safety | 0.302 | 0.643 | −0.062 | 0.074 |

| Hygiene | 0.130 | 0.766 | 0.077 | 0.137 |

| Easy to Reach | 0.296 | 0.307 | 0.134 | 0.358 |

| Opening Times | −0.054 | 0.110 | 0.175 | 0.830 |

| Complementary Services | 0.375 | −0.092 | 0.078 | 0.577 |

| Pleasant Area | 0.677 | 0.167 | −0.036 | 0.169 |

| All Weather Conditions | 0.656 | 0.018 | 0.346 | −0.030 |

| Accessibility | 0.682 | 0.176 | 0.319 | −0.020 |

| Cost-Convenience | −0.008 | 0.246 | 0.598 | 0.052 |

| Requirements from the System’s Economics | Requirements from Stakeholders | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality | Retailers | Customers | |

| (to adopt): a hierarchical perspective to the study | (constraint): multi-stakeholder, negotiating environment, subject to political tensions | ||

| (to investigate): agglomeration phenomena, same-side and cross-side effects of two-sided platforms (constraint): Attractiveness of each market depends on the assortment decided by independent retailers Markets attract consumers on the one side as well as retailers on the other, market size matters | (to ensure): service coverage and assortment completeness (constraint): the adopted license mechanism 16 markets had a saturation < 50, 10 markets achieved less than 30%. Retailers move where they achieve higher gains, consequent inability of the Municipality to reach a regular service coverage. | (constraint): retailers are independent economic actors, not passive agents Despite the location freedom, the interdependence of retailers’ behaviors and utilities affects entire market attractiveness. Opportunistic behaviors of unpleasant colleagues without a central coordination and too high difference with the services of supermarkets or shopping centers. (to ensure): mechanisms of coordination/control to supply service modules, not only as individual retailers, but by the market as a whole | (constraint): customer experience, as in shopping malls, is affected by poorer vs. richer configurations (from focus groups) Customer experience is affected by Safety, Trust, Encounter, Amusement, Tradition, and Convenience (from survey) the main determinants of experience are “usability”, “product range”, “safety” and “convenience” (from focus groups) Customer feelings of: scarce Accessibility, Safety, Chaos and Dirt |

| (to ensure): service coverage in an intra-channel and extra-channel competition environment Unevenly distributed service on the urban territory, inadequate service coverage, high inter-channel and distorted intra-channel competition, cannibalization | |||

| (to ensure): physical purchasing experience, without a multi-channel configuration | (from customer journey maps) Different purchasing processes by products | ||

| Identity | Label | Original Configuration | % | Designed Configuration | Delta Due to Differentiation | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clothes and Fabrics | C&F | 3 | 7% | 4 | 1 | 10% |

| Regional Goods | RG | 3 | 7% | 5 | 2 | 12% |

| High Quality | HQ | 5 | 12% | 6 | 1 | 15% |

| Low Prices | LP | 3 | 7% | 6 | 2 | 15% |

| Proximity | PR | 12 | 29% | 20 | 8 | 49% |

| No Identity | NI | 15 | 37% | - | −15 | - |

| Design Tasks | Method | Cultural Domains/Approaches | Object (to Study/to Design) | Role in the Process | Benefits (Participants Have Been Made Aware of/Have Learnt) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customers | Retailers and Trade Unions | Municipality/Other Stakeholders | |||||

| S1 | Descriptive statistical analyses | (Figure 3, cell 1) | The current situation | As an audience, to be aware of current situation | As an audience, to be aware of current situation | Current situation | |

| S2 | Gravity models | (Figure 3, cell 1) | The structural and managerial variables affecting market functioning | As an audience, to be aware of the effects of their location choices | As an audience, to be aware of the licensing mechanism effects | The effects of their choices | |

| R1 | Focus groups, Cognitive maps, Customer Journey Survey | (Figure 3, cells 2, 3) | Needs, purchasing behaviors, and the retail experience | Active participation to express opinions and improvement suggestions | As an audience, to be aware of customer preferences | As an audience, to be aware of customer preferences | The customer service requirements |

| R2 | Focus groups Survey | (Figure 3, cells 2, 3) | Individual motivations, positive and negative externalities | Actively involved to express opinions and to contribute to improvement | As an audience, to be aware of service requirements | The consequences of design choices | |

| R3 | Descriptive statistical analyses | (Figure 3, cell 1) | Overlaps in the offerings, service penetration, and the economics of retailers’ choices | As an audience, to be aware of requirements led by their location choices | As an audience, to be aware about a rationalized service coverage | The consequences of design choices | |

| CD1 | Adjacency matrices Multi-level service system | (Figure 3, cells 1–4) | The service modules at the single interface | Co-design with consumer organizations | Co-design with retailer associations | Co-design with officials from Municipality | How to operate in the future |

| CD2 | Platform-based design Multi-level service system | (Figure 3, cells 1–4) | The service platform and the modules in common to all markets | Co-design with consumer organizations | Co-design with retailer associations | Co-design with officials from municipality | How to operate in the future |

| CD3 | Platform-based design Multi-level service system | (Figure 3, cells 1–4) | The market alternatives at architectural level | Co-design with consumer organizations | Co-design with retailer associations | Co-design with officials from municipality | How to operate in the future |

| CD4 | Optimization Multi-level service system | (Figure 3, cells 1–4) | The value constellation at urban level | Co-design with consumer organizations | Co-design with retailer associations | Co-design with officials from municipality | How to operate in the future |

| CD5 | Focus groups Training courses | (Figure 3, cells 3, 4) | Active participation (entire constituency of retailers) | Active participation and facilitator | How to operate in the future | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Montagna, F.; Marcocchia, G.; Cantamessa, M. Tackling the Design of Platform-Based Service Systems, Integrating Data and Cultures: The Case of Urban Markets. Systems 2023, 11, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11020066

Montagna F, Marcocchia G, Cantamessa M. Tackling the Design of Platform-Based Service Systems, Integrating Data and Cultures: The Case of Urban Markets. Systems. 2023; 11(2):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11020066

Chicago/Turabian StyleMontagna, Francesca, Giulia Marcocchia, and Marco Cantamessa. 2023. "Tackling the Design of Platform-Based Service Systems, Integrating Data and Cultures: The Case of Urban Markets" Systems 11, no. 2: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11020066

APA StyleMontagna, F., Marcocchia, G., & Cantamessa, M. (2023). Tackling the Design of Platform-Based Service Systems, Integrating Data and Cultures: The Case of Urban Markets. Systems, 11(2), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11020066