Abstract

In the dual-channel retail industry, excessive enthusiasm in offline retailers’ services often extends beyond the customer’s “interpersonal distance zone”, leading to psychological discomfort for customers and a subsequent loss of demand. This situation can trap retailers in a dilemma known as the “service trap”. To address this issue, we introduce the concept of the zone of service tolerance, which encompasses desired and adequate levels of service, into a dual-channel supply chain consisting of an online channel manufacturer and an offline retailer. We incorporate the zone of service tolerance into the demand function of the offline retailer and establish its profit function, a dynamic game theory to demonstrate the existence of a linkage mechanism between the optimal selling price and service level, providing the conditions for such a mechanism to exist. Additionally, we establish conditions for offline retailers to avoid over-servicing or under-servicing and consider the impacts of these conditions, and we reveal the stability conditions of the offline retailers’ service decisions. Our findings indicate that both over- and under-servicing can lead to customer churn. For newly launched products, offline retailers risk losing customers by adopting a sales strategy focused on high profits and moderate sales (under-servicing). Similarly, for products nearing removal from the shelves, they risk losing customers by adopting a sales strategy focused on low profits and high sales (over-servicing). Furthermore, under certain ranges for the service sensitivity factor, desired service, or adequate service, the optimal service provided by offline retailers remains robust regardless of the manufacturer’s optimal selling price. This greatly simplifies the offline retailer’s decision-making process regarding service levels, as they can directly focus on providing the desired service without factoring in the manufacturer’s pricing strategy.

1. Introduction

The development of e-commerce has not only revolutionized the organizational structure and management approach of enterprises, as seen in the rise in platforms like Amazon and Alibaba but also transformed supply chain operations, particularly with innovations such as real-time tracking and automated warehouses. In recent years, an increasing number of manufacturers not only provide products and services through traditional offline sales channels (e.g., offline retailers) but also establish online channels for product sales to expand their markets. For instance, companies in sectors such as computing (e.g., Apple, IBM, Cisco), cosmetics (e.g., Estee Lauder), sports goods (e.g., Nike), and electronics (e.g., Samsung, Sony) have increasingly adopted dual-channel sales models in their supply chains [1]. This trend has been further accelerated by the shift towards omni-channel retail strategies and the rise in direct-to-consumer (DTC) platforms, with many brands leveraging both online and offline channels to enhance customer reach and optimize sales. However, the rising promotion costs associated with pure e-commerce platforms have gradually eroded their price advantage. Consequently, the problem of channel conflict stemming from price considerations has been weakened, giving rise to a new round of competition centered on marketing and service [2]. Pricing strategies not only influence consumers’ purchasing decisions but also shape their expectations and experiences regarding service quality. At the same time, service quality can enhance consumer satisfaction and loyalty, thereby indirectly supporting the implementation of pricing strategies. To gain a competitive advantage in a dual-channel environment, pricing and service strategies must be closely aligned, ensuring that the price and service quality across both channels complement each other and create a synergistic effect. Offline retailers possess significant advantages in providing services to customers when compared to online channels [3]. Offline retailers possess significant advantages in providing personalized services to customers, particularly regarding hands-on product experiences, immediate product availability, and the ability to engage with consumers face-to-face. Research indicates that customers exhibit a stronger preference for offline purchases due to the tangible experiences offered by brick-and-mortar retailers, which allow for direct interaction with products and a more immersive shopping environment [4]. However, during the shopping process, customers tend to evaluate the services they receive against their desired expectations. Expectations are shaped by various factors, including prior shopping experiences, marketing communications, social influences, and brand reputation. Advertising and promotional messages establish expectations regarding service quality, while past interactions with the brand or similar products influence customer anticipations concerning support, product performance, and convenience. If the actual service provided does not meet their expectations, customers may become dissatisfied with the offline retailer and be inclined to abandon purchasing products through the offline channel. For instance, if a customer needs hard services (e.g., a lounge, an air-conditioned shopping environment, etc.) in the purchase process, and the offline retailer fails to provide them, a psychological disconnect and dissatisfaction may arise. This can negatively impact customer loyalty and result in a loss of demand [5]. Furthermore, offline retailers may become overly zealous in their service improvements, crossing the so-called “interpersonal distance zone” and potentially causing psychological discomfort for customers. This, in turn, reduces customer satisfaction and ultimately causes a decline in demand. Such a situation pushes retailers into a “service trap”, where the psychological pressure on customers may lead them to abandon purchasing through offline channels.

The following personal experience took place at an offline shop in Guiyang, China, where the author visited to purchase a mobile phone. As the author entered the shop, an enthusiastic staff member asked, “How can I help you?” providing personalized assistance. The employee continuously recommended a specific phone, disregarding any potential customer resentment towards their overzealous behavior, and persistently emphasized, “This phone is truly special for you! This offer ends today!” In contrast, when we entered another specialty store, the sales associates did not proactively greet us or attend to our needs, completely overlooking our presence. When we inquired about the products, the response from the sales associate was indifferent and lacked any substantive assistance, which led us to feel disregarded. Another example that exemplifies excessive service is Haidilao, a renowned Chinese restaurant chain. Despite its reputation for good service, the public has criticized Haidilao for going overboard. For instance, when a customer dines at Haidilao, more than five waiters may assist them when they attempt to use the restroom. In contrast, when dining at other restaurants, there are instances where the wait staff fails to promptly clear the empty plates and cups from previous customers, leading to a sense of neglect. Additionally, when customers inquire about certain matters, the wait staff may lack patience or even exhibit an unwillingness to assist, which results in an unpleasant experience for the customers.

The above demonstrates that both over-service and under-service can lead to customer dissatisfaction. Therefore, studying the zone between under-service and over-service is crucial for retailers. These cases highlight the concept of the Zone of Tolerance in relation to the services provided by retailers [6]. The Zone of Tolerance comprises two service expectations or reference points, namely, desired service (DS) and adequate service (AS), as defined by Parasuraman et al. (1991) [7]. When a customer is in this zone of service tolerance, there is no negative utility to the customer, which leads to no loss of demand [8]. When the level of service provided by a retailer falls below AS, it is considered under-serviced, while exceeding DS is regarded as over-serviced. In order to avoid negatively impacting demand, retailers should aim to offer services within the zone of service tolerance. The previously mentioned under- and over-servicing situations essentially revolve around service expectations or reference points. When an offline retailer provides a service that the customer does not accept or that interferes with their purchasing activity, the service does not generate value. Likewise, if the service offered by the offline retailer does not fulfill the customer’s requirements, it fails to create value as well. The zone of service tolerance explored in this study refers to the range between DS and AS. In a dual-channel supply chain, the offline retailer uniformly provides service to non-segmented customers, with AS serving as the lower limit and DS as the upper limit. If the actual service level is below the AS, the customer may feel left behind and dissatisfied. Conversely, if the actual service level surpasses DS, according to the law of diminishing marginal utility, the customer’s satisfaction decreases, and they become resistant to the service. As a result, offline retailers can enhance customer satisfaction by offering service within the zone of service tolerance.

The purpose of this paper is to examine the factors contributing to under-servicing and over-servicing and to explore the impact of the zone of service tolerance on pricing and service strategies within supply chains. Specifically, this research aims to address the following questions:

- (1)

- How do the pricing strategies employed by manufacturers influence the service decisions of offline retailers?

- (2)

- Will the offline retailer provide services that surpass the desired service level or fall below the adequate service level, and what are the underlying reasons?

- (3)

- Is the optimal service level of the offline retailer resilient to the optimal pricing strategy of the manufacturer, and what are the conditions for this?

To study the above problems, the zone of service tolerance is incorporated into the pricing and service decision research framework of a dual-channel supply chain consisting of an online channel manufacturer and an offline retailer, and the influence mechanism of customer service expectation and the perceived service quality sensitivity coefficient on the optimal decision of a dual-channel supply chain is explored. Firstly, the zone of service tolerance is included in the demand function of offline retailers. On this basis, the game theory is used to demonstrate the conditions for the existence of a linkage mechanism between the manufacturer’s optimal selling price and the service level of offline retailers. Secondly, the conditions of offline retailer services in the zone of service tolerance and the factors that affect them are analyzed. Finally, the stability conditions of optimal service level decisions of offline retailers are established.

Our paper presents three contributions to the study of service and pricing strategies within a dual-channel supply chain context. First, in contrast to prior studies, this paper incorporates the concept of the desired service within the zone of service tolerance and analyzes the reduction in demand caused by over-servicing. We also examine the impact of customer service expectations and the service sensitivity coefficient on pricing and service decisions. Second, we establish a linkage between the manufacturer’s optimal sales price and the service level provided by the offline retailer, given that the price cross-elasticity between channels is within a specific range. Next, we demonstrate the existence of under-service or over-service, analyzing the sales strategies adopted by offline retailers for products at different lifecycle stages and exploring the underlying reasons for these strategies. Finally, we find that, when the over-service sensitivity coefficient and either the desired service level or the adequate service level fall within a certain range, the offline retailer’s optimal service level remains stable relative to the manufacturer’s optimal sales price. This finding significantly simplifies offline retailers’ decision-making process in determining the optimal service level.

The structure of this paper is outlined below. The following section provides a review of the related literature. Section 3 outlines the problem formulation and assumptions. The mathematical models that were developed are presented in Section 4. Numerical results and sensitivity analyses are described in Section 5, and, in Section 6, we conclude our findings and suggest management insights and possible future research.

2. Literature Review

Since this paper deals with service quality and dual-channel supply chain decisions, the relevant literature is divided into two parts, namely, service quality and dual-channel pricing and service.

2.1. Service Quality

Service quality refers to a comparison between the customer’s service expectations and the actual service quality. Gronroos, a Finnish-Swedish professor of economics, was one of the first to introduce this concept. He argued that, when the actual service quality is higher than the service expectations, the customer’s perceived service quality is good, and, conversely, the customer will be dissatisfied [9]. He also believes that customer-perceived service quality consists of three components: technical quality, functional quality, and company image. For example, technical quality refers to the accuracy and efficiency of the service provided, such as a hotel’s ability to ensure a smooth check-in process. Functional quality involves the interpersonal aspects of service, such as the friendliness and professionalism of staff at a restaurant. Lastly, company image encompasses the overall perception of the brand, like the trustworthiness and reputation of a luxury brand. He also distinguishes between perceived service quality and the quality of tangible products, emphasizing that service quality is more about the customer’s experience than the physical attributes of a product. Parasuraman et al. (1985, 1991) [7,10] further suggested on the basis of Gronroos’ research [9] that customers form their own service expectations based on their previous shopping experiences, which are divided into DS (desired service) and AS (adequate service). The area between DS and AS is called the customer’s zone of service tolerance. When the service level is below the threshold AS, demand increases as the service level rises. This effect can be attributed to two opposing mechanisms. On the one hand, the increase in service level directly boosts demand, representing a positive effect. On the other hand, the improvement in service level reduces the negative utility perceived by customers, which also leads to an increase in demand, reflecting a negative effect. When the service level exceeds DS, the impact on demand becomes more complex. Depending on the relative magnitudes of these two effects, it may either increase or decrease. Specifically, the positive effect tends to increase demand, whereas the negative effect, resulting from an increase in customer negative utility, leads to a reduction in demand. When the service level is between AS and DS, the negative effect becomes negligible, and the positive effect dominates, increasing demand. DS is a service that satisfies the customer entirely, while AS is a service that does not annoy the customer. Chen (2014) [6] also developed a service quality evaluation model based on the zone of service tolerance in order to investigate how to improve the service level of hotels, enabling hotel managers to gain a competitive advantage. Chi et al. (2007) [11] believed that there are three types of service expectations that influence the customer satisfaction and evaluation of services, namely, focal-object expectations, other-object expectations and self-based expectations. Although previous studies have concentrated on the factors affecting service quality, some researchers have explored how the combination of actual service from offline retailers and customer service expectations shape purchasing decisions. Ghobadian et al. (1994) [12] found that service quality actually affects the repurchase intentions of existing and potential customers. Pratminingsih et al. (2018) [13] explored the impact of experiential marketing and service quality on consumer satisfaction and loyalty in ethnic restaurants, stating that, if visitors are dissatisfied with the service provided by the restaurant, it can have a negative impact on reducing loyalty to the restaurant and that developing experiential marketing programs and providing excellent service quality can provide solutions for increasing customer loyalty. Öztürk (2015) [14] also found that high customer loyalty can lead to them buying more products or bringing in more customers. Conversely, it can “drive away” customers and even take away other potential customers. That is to say, when offline retailers fail to provide a service that meets the needs of their customers, customers become dissatisfied, which in turn reduces their loyalty and leads to lower demand. Oliveira et al. (2023) [15] contemplates customers’ expectations about service guarantees in an e-commerce platform, relating them to attitudes and behavioral intentions. Veas-González et al. (2024) [16] investigated the fact that service quality is one of the key factors affecting customer satisfaction and customer loyalty in the fast food industry. Bunga et al. (2023) [17] found that service quality has a positive direct and indirect effect on customer trust, which in turn affects customer satisfaction. Golalizadeh et al. (2023) [18] showed that online perceived service quality affects customers’ purchase intentions as well as impulse buying behavior.

Most of these above-mentioned studies have shown that service level positively affects customers’ purchasing behavior [10]. However, can offline retailers necessarily increase customer satisfaction, loyalty, and product demand when they are bent on providing high-quality service levels? Lee and Hur (2019) [19] then argued that high service levels can have both positive and negative effects on customers’ purchasing behavior. If offline retailers continually raise service levels in an attempt to enhance service, they may end up over-servicing, which could create a sense of psychological pressure for customers, leading to a decrease in customer satisfaction and ultimately resulting in a “service trap”. Tosun et al. (2015) [20] found through their analysis of tourism services that the way services are provided will have a huge impact on customer satisfaction, and an inappropriate service approach can lead to a decrease in customer satisfaction and can even have a negative effect. Polas et al. (2022) [21], in their study of restaurant service, also found that improvements in service quality did not significantly increase customer satisfaction and significantly discouraged secondary purchases. This is because overly enthusiastic service invades part of the customer’s privacy and leads to customer disgust. The above literature suggests that over-servicing can lead to a decline in customer satisfaction, ultimately resulting in a “service trap”. Service expectations are shaped by the promotion and promise of the product. Providing a service that is not in line with promises can affect customer satisfaction and thus affect long-term customer demand. Balinado et al. (2021) [22] assessed the service quality of after-sales service in the automotive industry, highlighting that, when after-sales service fails to meet customer expectations, customer loyalty and demand may be significantly affected. This indicates the critical importance of ensuring consistency between service delivery and promises in maintaining customer satisfaction and fostering long-term demand. Park et al. (2020) [23] examined how the quality of airline service attributes influences overall satisfaction and proposed that the quality of attributes has heterogeneous effects on satisfaction or dissatisfaction. Mehta et al. (2023) [24] assessed customer satisfaction through sentiment analysis and the theme modeling of customer reviews of hospitality services provided by hotels in various continents from January to September 2020. Li et al. (2024) [25] found that over-service can intensify consumers’ service stress and negatively affect satisfaction and willingness to revisit.

From the above literature, it is clear that service expectations significantly impact customer loyalty and satisfaction, which in turn influences customer purchasing behavior. Thus, evaluating how the service tolerance zone affects the demand in a dual-channel supply chain due to under-servicing and over-servicing can help manufacturers refine their pricing strategies and assist offline retailers in optimizing service decisions.

While service quality directly influences customer satisfaction and loyalty, it also plays a critical role in shaping pricing decisions, as retailers must balance the costs of high-quality service with competitive pricing strategies to optimize both customer retention and profitability.

2.2. Dual-Channel Service and Pricing

In today’s rapidly evolving retail landscape, a growing body of research emphasizes the strategic importance of pricing and service decisions within dual-channel supply chains, as they play a critical role in optimizing both online and offline sales channels. In a dual-channel supply chain, customers take into account both price and service level when making purchasing decisions. Increasing numbers of researchers have explored service-related decision making in a dual-channel supply chain. Chen et al. (2012) [26] found that, when customers buy products, they are not only affected by channel preferences and prices but also by services. For example, a customer may choose to purchase a product online at a higher price if it comes with faster delivery options or superior customer support. Based on this, Wu et al. (2004) [27] addressed the issue of competition in segmented markets, with findings indicating that offline retailers could gain extra profits by offering information services, even in situations involving free riding—where consumers take advantage of services without paying for them. On the contrary, Shin (2007) [28] suggested that free riding may not necessarily harm offline retailers offering services, and the findings indicated that it could reduce the price competition among them. To reduce the influence of free riding, Xing and Liu (2012) [29] developed contracts for price matching and selective compensation rebates to coordinate the sales activities of offline retailers. Dan et al. (2012) [30] assessed how retail services and customer loyalty towards retail channels influence the pricing strategies of manufacturers and offline retailers. Zhang et al. (2019) [31] analyzed the impact of dual-channel cooperation on pricing by comparing the traditional dual channels, the business model based on platform channels, and the business model of dual-channel cooperation. Dai et al. (2023) [32] examined the pricing and service strategies of both restaurants and online platforms, taking their service levels into account, and discovered that the optimal pricing strategy is influenced by customer sensitivity to service levels and the associated cost coefficients. Song et al. (2020) [33] studied the influence of online purchase and offline pickup behavior on pricing through the enterprise data of the cooperative mode of online purchase and offline pickup. Based on this, Jiang et al. (2020) [34] studied the equilibrium pricing problem under centralized and decentralized decision making and pointed out that the service level of offline retailers would affect their pricing strategies. Guo et al. (2020) [35] studied pricing and the retailers’ choice of delivery lead time in a dual-channel supply chain. Zhang et al. (2023) [36] investigated how advanced delivery and cross-channel returns impact the pricing decisions of retailers within a dual-channel supply chain. Xu et al. (2021) [37] examined the pricing and ordering decisions of retailers faced with online order overload and found that product pricing would remain unchanged or decrease after the retailer implemented the buy-online-and-pickup-in-store (BOPS) strategy. Also, Yang and Ji (2022) [38] considered the pricing of dual channels in the case of online purchases and offline returns. Wang et al. (2023) [39] studied the pricing and channel selection of dual channels with the framework theory of the game in consideration of transportation costs.

As dual-channel differential pricing tends to increase the conflicts among channels, more and more enterprises, such as Suning and Uniqlo, choose non-differential pricing. Zhou et al. (2018) [40] explored the impact of “free riding” behavior on pricing/service strategies and the profits of two channels, examined both differentiated and undifferentiated pricing scenarios, and concluded that undifferentiated pricing benefits offline retailers more but has the opposite effect on manufacturers and the overall supply chain. Li et al. (2019) [41] focused on the problem of the timing of service provision; they examined three scenarios of service capabilities without considering service, ex-ant service, and ex-post service in a dual-channel supply chain, and the equilibrium result suggested that post-service had the best effect. Taleizadeh et al. (2019) [42] focused on decisions related to pricing, service, and quality levels in a two-tier supply chain where alternative products are available. Zhang et al. (2020) [43] examined the situation of a dual-channel supply chain network, where manufacturers provide services in both channels, while offline retailers only provide offline services, proving the existence of Nash equilibrium. Fan et al. (2022) [44] studied the optimal service decision problem under the two-store mode. Zhai et al. (2022) [45] explored how service investment and pricing decisions are affected by various power structures in the presence of demand disruptions. Zhang et al. (2022) [46] examined how pricing decisions can be used to balance service and return costs in a manufacturer’s dual-channel supply chain. Chen et al. (2024) [47] examined how offline channel preferences and service levels influence pricing decisions in a dual-channel supply chain. Lu et al. (2024) [48] explored the strategy for coordinating pricing and service levels in a dual-channel pharmaceutical supply chain. Gu et al. (2023) [49] examined how offline in-sale services affect the performance of a dual-channel supply chain, comparing the impact of service quality on the profits of both retailers and manufacturers in cooperative and non-cooperative scenarios. Lin et al. (2023) [50] investigated a dual-channel service-only supply chain and analyzed its dynamic pricing in two consecutive periods. Li et al. (2024) [51] examined the coordinated decision-making process regarding pricing and promotional strategies in the service collaboration between online and offline retailers and observed that higher levels of after-sales service make consumers more sensitive to service quality.

Despite its significance, the existing literature has yet to incorporate the zone of service tolerance into the research framework for pricing and service decisions in a dual-channel supply chain, leaving a critical gap in understanding. The zone of service tolerance exerts a bidirectional influence mechanism on the pricing strategies of manufacturers and the service decisions of offline retailers. Only He et al. (2022) [5] considered AS under a dual-channel supply chain environment, but DS is not considered in this paper. So, they did not take into account the real zone of service tolerance, which is also different from the essence of this paper. Therefore, this paper incorporates the effects of the discrepancies between the actual service level and customer service expectation on product demand into the framework of pricing and service decisions in dual-channel supply chains and investigates the influence mechanism of the sensitivity coefficient of the zone of service tolerance and service expectation on the optimal decision making of members of the dual-channel supply chain in the case of customers’ “free-riding” behavior and service expectation.

3. Problem Description and Assumptions

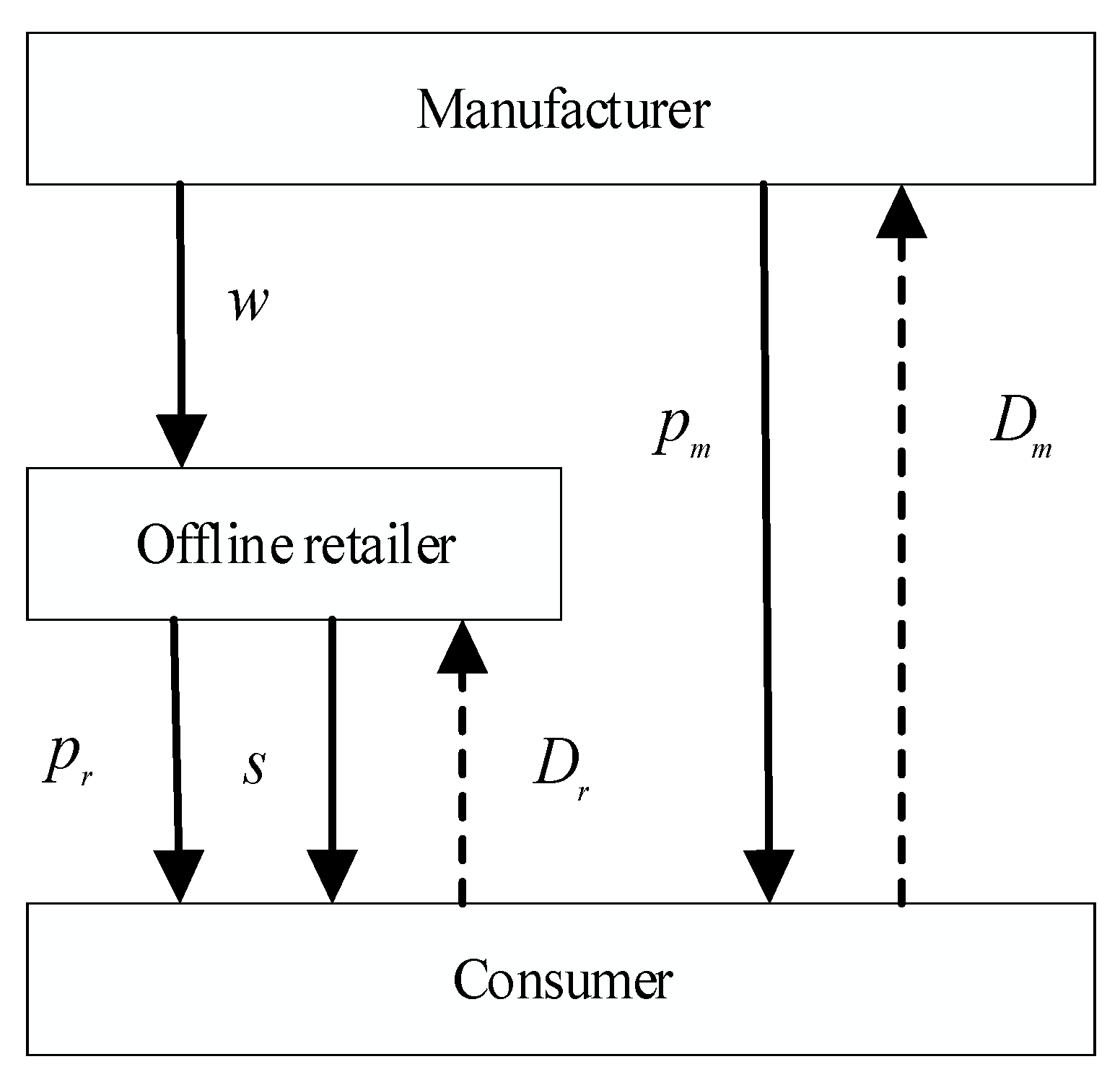

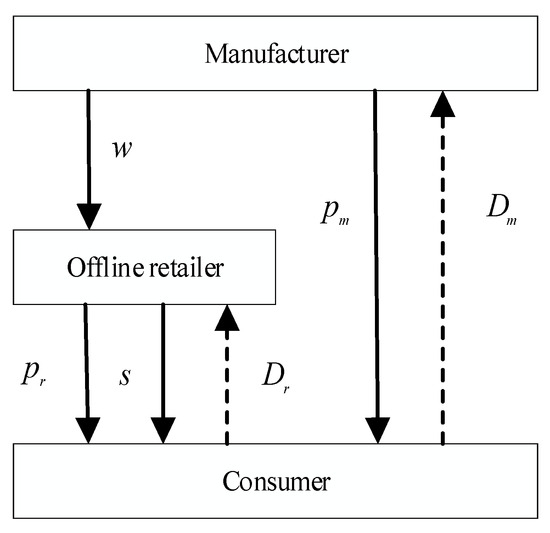

In this paper, we consider a two-tier supply chain system consisting of a manufacturer opening an online channel and an offline retailer, as shown in Figure 1. This dual-channel structure is particularly significant as it captures the evolving dynamics between traditional retail and digital sales, providing insights into how each channel can influence pricing and service strategies. Customers can purchase products through two channels. It is assumed that customers who prioritize convenience and lower prices are more likely to choose online channels. However, customers may prefer the offline option due to factors such as immediate product availability or personalized service. The first is to purchase products directly from manufacturers through online channels. The selling price of this channel is pm, and the demand is denoted as Dm. The second is to purchase through offline retailers. The sales price of this channel is pr, and the demand is denoted as Dr. These two channels may serve distinct customer segments—online customers may prioritize convenience and price, while offline customers may prefer in-person shopping for immediate availability or personalized service. However, there could be some overlap, especially among customers who value both online convenience and offline experiences. The manufacturer’s wholesale price is w. The manufacturer’s wholesale price serves as the basis for the pricing decisions of both the manufacturer and the retailer. The manufacturer sets the online channel price based on the wholesale price, while the retailer determines the offline retail price by applying a markup to the wholesale price. In order to guide customers to buy products, offline retailers provide face-to-face product introduction, consultation, and other services, whose service level is denoted as S. This service level includes not only pre-purchase assistance, such as product demonstrations and advice but also post-purchase services, such as after-sales support, returns, and customer care. The service cost function is expressed as , as referred to in Dan et al. (2012) [30].

Figure 1.

A dual-channel supply chain.

Xiong et al. (2018) [52] found that offline retailers tried to establish a reciprocal relationship with customers by providing services to them. On the one hand, the presence of reciprocal anxiety makes it possible for retailers to over-serve their customers, so there are counter-productive consequences, such as the reconsideration of product purchases, reduced customer satisfaction, and reluctance to actively engage in word-of-mouth communication for offline retailers. On the one hand, the presence of reciprocal anxiety makes it possible for retailers to over-serve their customers, so there may be counter-productive consequences, such as the reconsideration of product purchases, reduced customer satisfaction, and reluctance to actively engage in word-of-mouth communication for offline retailers. The offline retailer offering more than DS to customers can lead to a drop in demand in the offline channel. On the other hand, when the offline retailer offers lower than AS to customers, it can also lead to a drop in demand in the offline channel. The zone of service tolerance is denoted as , is the AS, and is the DS. When the service provided is above or below this interval threshold, it will result in a reduction in demand. Based on the demand function for dual-channel systems developed by Dan and Xu et al. (2012) [30], the demand functions for the offline retailer and the manufacturer are established separately as follows:

Equations (1) and (2) represent the demand functions for the offline retailer and manufacturer online channels, respectively. is the market share held by the offline retailer in the offline channel. Since online and offline sales are assumed to be homogeneous products, it is assumed that . is the cross-price elasticity coefficient between channels, . We also assume that . is the coefficient of “free riding”. and represent the under-service sensitivity coefficient and over-service sensitivity coefficient, respectively. Referring to Ho et al. (2010) [53], the demand loss caused by under-service is ; the demand loss caused by over-service is , where . Generally speaking, since customers are more familiar with the daily necessities that they often buy, they have a higher sensitivity coefficient to the excessive service of such products. For electronic products with low purchase frequency (such as mobile phones and digital cameras), the over-service sensitivity coefficient is low.

4. Model Construction and Analysis

Firstly, the profit functions of the offline retailer and the manufacturer are established, respectively, according to their demand functions, as shown in Equations (3) and (4). These profit functions are critical as they provide the foundation for analyzing the pricing and service strategies of each party, allowing for a deeper understanding of how both entities maximize their profits within the dual-channel supply chain framework.

From Equation (3), represents the profit made by the offline retailer when selling products, and represents the service cost for the offline retailer. From Equation (4), represents the profit generated by the manufacturer selling products to the offline retailer at wholesale price , and represents the profit generated by the manufacturer from selling directly to the customers at selling price . Since the manufacturer is in a strong position, the manufacturer sets the selling price . This assumption is based on the manufacturer’s control over production and supply, as well as its ability to influence market pricing through brand reputation, economies of scale, and established relationships with retailers. In many industries, particularly in sectors with dominant manufacturers or when there is a clear market leader, manufacturers typically hold greater power in price-setting. This has been observed in industries such as electronics and consumer goods, where manufacturers drive pricing strategies. According to this price, the offline retailer determines the optimal service level to maximize its profit. The retailer’s decision is constrained by the budget available for service provision, the competitive landscape, and the required service quality to attract customers without exceeding cost limits. The optimal level of service can be determined by solving Equations (3) and (4) using the optimization method, and the following proposition is obtained.

Proposition 1.

For a given selling price, the optimal service provided by the retailer is shown as Equations (5) and (6). This result demonstrates the retailer’s optimal service strategy, indicating how the service level is influenced by the pricing decision and its impact on maximizing profitability within the context of the retail environment.

- (1)

- If ,

- (2)

- If ,

Proof of Proposition 1.

The optimal service effort level is substituted into Equation (4) to solve for the optimal selling price. If , convert (4) into the following optimization problem:

Introducing the generalized Lagrange Multiplier , let the K-T point be , and thus obtain its K-T condition as follows:

The optimal selling prices and optimal service level can be expressed as

To ensure that holds, conditions and need to be satisfied, while conditions and need to be satisfied to ensure that holds. Therefore, the price cross-elasticity coefficient between channels satisfies . Other cases can be analogous to this method. □

Proposition 1 shows that, when the manufacturer sets a fixed selling price, an increase in the manufacturer’s price may encourage offline retailers to provide a level of service surpassing their DS, particularly when the sensitivity to over-service is low. Conversely, when the over-service sensitivity coefficient is large, the customer’s aversion to over-service is too high, and the over-servicing provided by offline retailers not only increases the service cost but also leads to customer dissatisfaction and reduced demand regardless of whether the under-service sensitivity coefficient is small or large. When the manufacturer’s pricing is low, offline retailers will provide services that are lower than AS for customers due to the cost of service. On the whole, as the manufacturer’s pricing increases, the level of service that offline retailers choose to provide will also increase in order to earn greater profits. In addition, offline retailers are robust to the manufacturer’s optimal pricing when they set the optimal service level.

When the manufacturer sets a lower price, i.e., when is satisfied, its price compensation mechanism fails to offset the rise in service costs caused by the reduced price, leading offline retailers to offer services that fall below the AS of customers, which leads to its lower demand but also lower service costs to compensate for the loss caused by demand. Thus, from Equations (5) and (6), we obtain the result that, when , the offline retailer will consider the under-service to reduce the service cost in order to obtain greater profit.

When the sales price satisfies , for offline retailers, manufacturer pricing is low. Although increasing the service level raises its service cost, it can also lead to an increase in product demand and reduce the negative externality of under-service. Therefore, offline retailers will opt to deliver customers with the service level of the AS, which not only mitigates the negative impacts of under-service but also reduces their service costs.

When the sales price satisfies , for offline retailers, the manufacturer’s pricing in this range can compensate for the service cost, and improving the service level to a certain extent can also improve the product demand. However, due to the negative externality of over-service, exceeding the DS of customers leads to profit loss, and the pricing in this range cannot be compensated. Therefore, offline retailers will choose to increase service levels as sales prices change but will not under-service and over-service.

When the sales price satisfies , for offline retailers, the manufacturer determines this range of pricing. Although the manufacturer’s pricing is high, offline retailers should improve the service level, due to the negative externality of over-service, which would not only make the product demand decline, but also increase the cost of services. In this range of over-service, loss cannot be compensated. Therefore, offline retailers will choose to provide the service level of DS of customers to avoid over-service.

With the increase in the sales price, when the sales price meets , if the over-service sensitivity coefficient is small, offline retailers will provide over-service. The reason is that, when the sensitivity coefficient for over-service is relatively low, even if the service level provided by offline retailers surpasses customers’ service expectations, the over-service has a minimal effect on reducing product demand and is more than offset by the revenue generated from higher prices. As a result, as the sales price increases, offline retailers will still provide a higher service level and will exceed the DS of customers. However, when the over-service sensitivity coefficient is large, and the service level provided by offline retailers exceeds the DS of customers, the demand for products will be drastically reduced, and the reduction in demand cannot be compensated by the revenue brought by the increase in price. Therefore, when the over-service sensitivity coefficient is large, offline retailers will not over-service but only provide a service level equal to the DS of customers.

Proposition 2.

When the condition is satisfied, there is the optimal selling price and service level as shown in Equations (7) and (8), respectively.

- (1)

- If ,

- (2)

- If ,

where

, ,

, ,

,

, ,

, ,

.

Proof of Proposition 2.

Refer to the proof method of Proposition 1. □

Proposition 2 indicates that, when the price cross-elasticity coefficient between channels is within a certain range, an optimal selling price and service level can be determined, with a linkage mechanism connecting the optimal selling price to the service level. When the price cross-elasticity coefficient is below this region, the degree of substitution between the two channels is low, the mutual influence diminishes, and the service externality provided by offline retailers is reduced. Since the prices of the two channels are the same and the services no longer have an externality, there is no longer an optimal level of service. When the price cross-elasticity coefficient is higher than this region, the degree of substitution between the two channels is higher, and the mechanism of selling price influence on demand is weakened, making the pricing mechanism ineffective. In the extreme case, when the two channels are fully substituted, i.e., , the selling price no longer affects the demand for the product.

Additionally, from Equations (7) and (8), it can be obtained that the optimal selling price and optimal service level increase with the increase in the customer service tolerance domain threshold. The higher the customer service tolerance domain threshold, the higher the customer’s demand for the service level. Equations (1) and (2) indicate a substitution relationship between the product price and service quality for consumers in the zone of service tolerance. Hence, manufacturers induce offline retailers to improve their service level by increasing pricing in order to sell more products and thus gain more customers. As shown above, despite the manufacturer and offline retailer being distinct decision makers, a linkage mechanism exists between the optimal selling price and service level. That is, a higher price is inevitably associated with a higher service level, and vice versa. Moreover, when customers demand higher service levels, the manufacturer will not blindly raise the service level, as its compensation system is inadequate to cover the additional service costs incurred by the offline retailer.

Corollary 1.

Offline retailers will provide over-service when the over-service sensitivity coefficient satisfies , and the DS of customers satisfies ; offline retailers will under-service when the AS of customers satisfies , independent of the under-service sensitivity coefficient .

Proof of Corollary 1.

From Equations (7) and (8), we can prove that is satisfied when and . Similarly, when , is satisfied. □

Corollary 1 indicates that, when the over-service sensitivity coefficient is low, and the DS of customers is also low, offline retailers tend to offer over-service. This contradicts our intuition. When the DS of customers is low, the effects of over-service outweigh those of under-service. Hence, as a result of the positive externality of service, when the manufacturer’s price compensation mechanism can offset the profit loss incurred from service costs, offline retailers will moderately increase their service levels to achieve higher profits, assuming an exogenous wholesale price. Consequently, offline retailers are willing to provide higher service levels than the DS of customers at lower retailer prices. In practice, customers are more familiar with electronic products that are withdrawn from the market, and their shopping habits make DS low. They do not expect service personnel to go beyond the “interpersonal distance zone”, resulting in unpleasant shopping. However, with the upgrading of electronic products, offline retailers will strongly recommend that customers buy electronic products that will be delisted at the risk of customer loss and adopt the strategy of small profits and quick sales to sell electronic products that will be delisted. Hence, offline retailers tend to provide services that are higher than the DS of customers.

However, when the AS of customers is high, offline retailers will seek to enhance their service level, but they will not do so blindly. The reason is that, at very high customer AS, the impact of under-service outweighs that of over-service. Offline retailers will try their best to provide customers with satisfactory service levels to reduce the impact of under-service, and the rise in profits does not offset the increase in service costs, so offline retailers will not continue to improve the service levels to blindly meet customer service needs. In effect, customers are unfamiliar with newly listed electronic products or daily necessities and often want retailers to provide more detailed and personalized services, often with higher AS and under-service, resulting in a psychological gap and unpleasant shopping. For instance, for newly launched products, the manufacturer’s pricing is higher, and offline retailers will provide customers with higher service levels but will not ignore the existence of service costs to blindly meet customer demand. By pursuing a strategy focused on high profitability and marketability for newly launched products, offline retailers risk losing customers. As a result, they are more likely to provide a service level lower than the AS of customers.

So, for daily necessities that will be delisted, offline retailers will also provide over-service? And is under-service widespread for newly launched electronics or daily necessities? Corollary 2 gives the corresponding conclusion.

Corollary 2.

As the over-servicing sensitivity coefficient increases, the scope of over-servicing by offline retailers decreases. As the under-servicing sensitivity coefficient increases, the scope of under-servicing by offline retailers decreases.

Proof of Corollary 2.

The first-order derivative of with respect to yields ; the first-order derivative of with respect to yields . □

Corollary 2 suggests that, with the increase in the over-service sensitivity coefficient , the scope of offline retailers to provide over-service becomes smaller until they do not provide over-service. The reason is that, as the over-service sensitivity coefficient rises, the demand for offline retailers’ products resulting from over-service gradually diminishes. When the over-service sensitivity coefficient reaches , the product demand brought by the over-service will no longer grow, but, instead, service costs will rise. In practice, thanks to customers are more familiar with the daily necessities to be withdrawn from the market, they have their own purchase decisions and do not want excessive interference, so they are more averse to over-service. Then, providing over-service is more unfavorable, and they cannot achieve the purpose of small profits and quick sales, so the scope of providing over-service is getting smaller and smaller until it is not considered to provide over-service.

As the sensitivity coefficient of under-service increases, the scope of under-service provided by offline retailers diminishes. The reason is that, with the rise in the under-service sensitivity coefficient, the negative impact of under-service on the product demand of offline retailers becomes more significant. In effect, thanks to customers who have a low understanding of the newly launched products, especially electronic products, they need more personalized and more accurate services, so they are more averse to under-service. As a result, providing less than the service expectation is more unfavorable and cannot achieve the purpose of profit and marketability. Thus, the scope of providing less than the service expectation is getting smaller and smaller.

So, is it necessary to consider the zone of service tolerance, and what is the difference when it is not considered? Proposition 3 gives the corresponding conclusion.

Proposition 3.

When , and hold. When , and hold.

Proof of Proposition 3.

When the zone of service tolerance is not considered, the optimal selling price and the optimal service level are, respectively:

So , . From Proposition 2, when , we obtain , . Similarly, within the range of , we obtain and ; within the range of , we obtain and ; within the range of , we obtain and ; within the range of , we obtain and ; within the range of , we obtain and . □

Proposition 3 indicates that, compared to the case where the customer service level reference effect is not considered, the optimal service and selling price are significantly lower when DS is low and significantly higher when AS is high. The reason is that, when the desired service level is low, offline retailers will provide a service level lower than what would occur without considering the reference effect of customer service levels. This is because the over-service not only increases service costs but also reduces demand due to over-servicing. On the other hand, manufacturers prefer offline retailers to offer a higher service level due to the positive externality of service. However, for electronic products that are about to be delisted, the manufacturer will reduce the selling price to encourage offline retailers to provide a higher service level while moderately increasing the price to offset the decline in product demand caused by over-service. When the adequate service level is high, offline retailers will offer a service level greater than they would if the reference effect of customer service levels was not considered due to the decrease in their own demand caused by under-service. For manufacturers, when offline retailers provide a higher service level, they also set a higher selling price to improve revenue.

In effect, when a product is first launched, on the one hand, the customer’s expectation of minimum acceptable service is high; on the other hand, customers do not care about the selling price but place more emphasis on the service level. Blindly increasing the service level may improve product demand and mitigate the effects of under-service, but it is insufficient to offset the rise in service costs. As a result, the manufacturer would prefer to take the risk of losing customers by pursuing a profitable and marketable strategy. For example, the newly listed Huawei mobile phone is using this strategy; when it was just listed, its sales price was higher, and the service level was also higher.

However, when the product is about to be delisted from the market, customers do not care about the service level and pay more attention to the price because they know more about the product and have lower service expectations. Hence, manufacturers and offline retailers will adopt lower selling prices and lower service levels. For instance, Huawei mobile phones to be delisted will adopt a thin profit and marketable strategy. When the products are delisted, their sales price and service level are reduced. Although offline retailers will offer a service level above the minimum acceptable service expectation, it remains significantly lower than what would be provided without considering customer service expectations.

Proposition 4.

When the over-service sensitivity coefficient satisfies and , or satisfies and , the optimal service level of offline retailers has stability on the pricing of manufacturers. The offline retailer decides to offer a service level that matches the customer’s highest acceptable service expectation, independent of the manufacturer’s pricing strategy. The smaller the over-service sensitivity coefficient is, the smaller the stability range is.

When the customer’s minimum acceptable service expectation is , the optimal service level of offline retailers remains stable relative to the manufacturer’s pricing. Regardless of the manufacturer’s pricing strategy, the offline retailer will choose to provide a service level equal to the customer’s minimum acceptable service expectation.

Proof of Proposition 4.

When and , in the range of , offline retailers will choose to provide the highest level of service, that is

When and , within , that is

Taking the first-order derivative of with respect to , we obtain . Taking the first-order derivative of , and with respect to , we obtain . Other cases can be obtained in the same way.

When the customer’s minimum acceptable service expectation is , the first-order derivative with respect to for yields . The first-order derivative with respect to for , and yields . Thus, its optimal service level is stable compared to the manufacture’s optimal pricing. □

Proposition 4 indicates that the optimal service level of the offline retailer is stable compared to the manufacturer’s optimal selling price when the over-service sensitivity coefficient and the expectation of the highest acceptable service are within a certain range. The reason is that there are two effects when the service level provided by offline retailers is high: the rise in service costs and the loss of demand resulting from the service level surpassing the highest acceptable service expectation. The second effect will be very obvious, especially when the over-service sensitivity coefficient is large. Hence, due to the existence of the second effect, the manufacturer cannot compensate for the demand loss caused by the over-service through the compensation mechanism of setting a lower selling price, so offline retailers will only provide a service level equal to the highest acceptable service expectation. In contrast, the smaller the over-service sensitivity coefficient, the compensation mechanism of the manufacturer will easily compensate for the demand loss caused by the over-service of the offline retailer and, therefore, will exceed the highest acceptable service expectation.

Alternatively, when the minimum acceptable service expectation falls within a specific range, the offline retailer’s optimal service level remains stable relative to the manufacturer’s optimal selling price. The reason for this is that, when the minimum acceptable service expectation is high, two effects arise from a lower service level provided by the offline retailer: a decrease in service costs and a demand loss due to under-service. As the service expectation increases, it becomes increasingly difficult for the manufacturer to offset the rise in service costs through a higher selling price compensation mechanism. As a result, offline retailers will only provide a service level equal to the service expectation. This continues until the minimum acceptable service expectation reaches a threshold, where the impact of the first effect grows larger than the second effect. At this point, the manufacturer’s compensation mechanism, through higher selling prices, can no longer offset the increased service costs incurred by the offline retailer’s higher service level. This finding may vary across industries, as sectors with different service dynamics and cost structures—such as luxury goods versus mass-market products—may experience different levels of effectiveness in the compensation mechanism and its impact on service-level decisions. Therefore, offline retailers will provide a service level lower than the minimum acceptable service expectation, leading to the under-servicing of customers. This not only reduces customer satisfaction and loyalty but can also result in customer churn, ultimately affecting brand image and long-term sales performance.

In practice, this significantly simplifies the service decisions for offline retailers, enabling them to leverage decision-making tools such as cost–benefit analysis, service level optimization models, or dynamic pricing strategies to manage service levels and associated costs effectively. By understanding the service expectations of customer segments, retailers can directly offer the service level that customers expect without needing to consider the manufacturers’ selling prices.

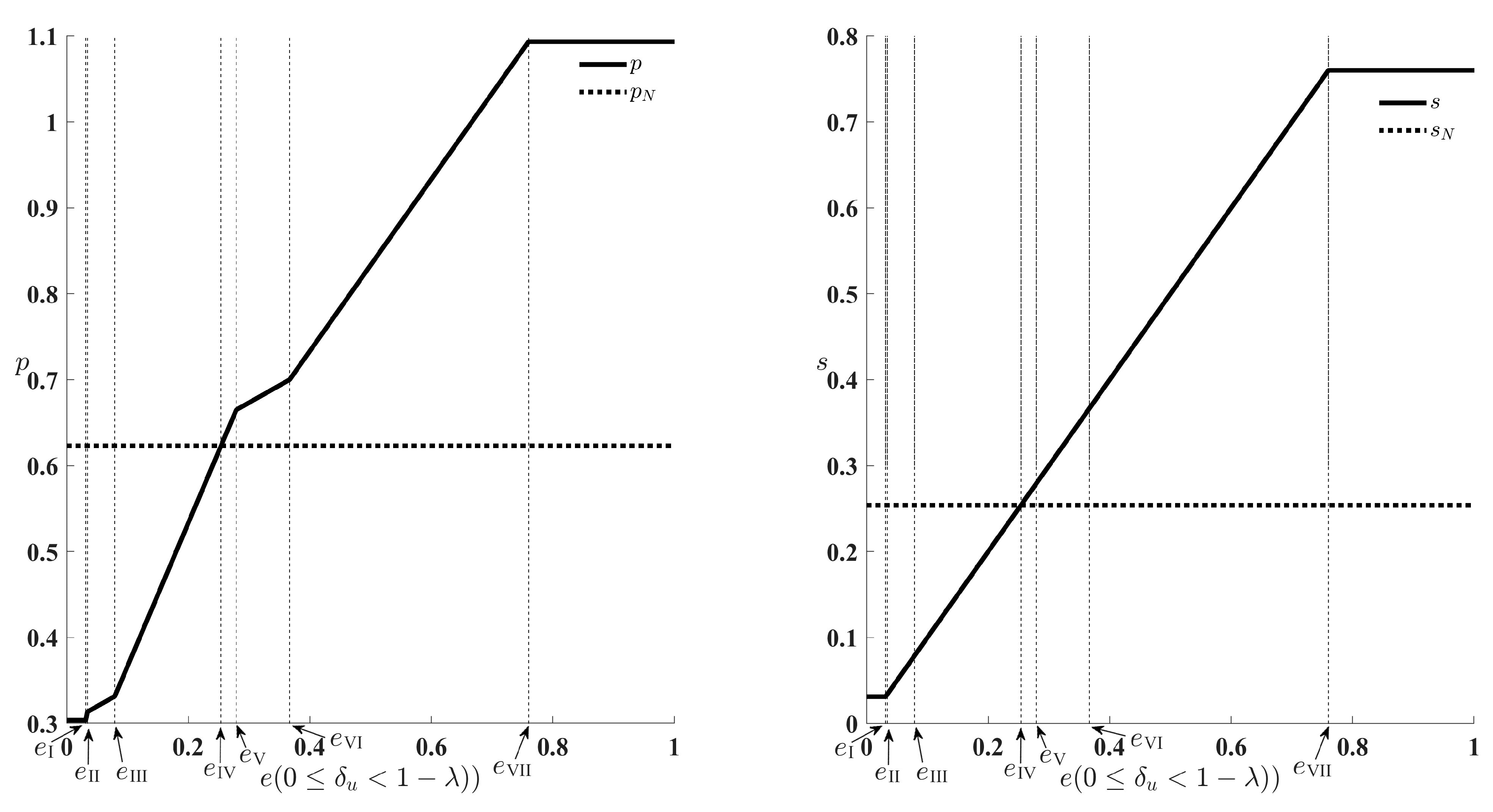

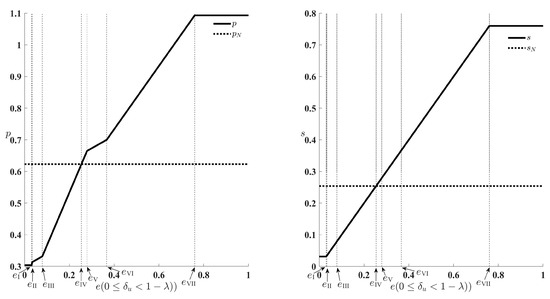

5. Numerical Analysis

In this paper, the previous conclusions are further verified by numerical analysis, assuming the essential parameters: , , , , , . indicates that, when the total market share is 1, the offline retailer’s share in the offline channel is 0.6, meaning the offline channel accounts for a larger share than the online channel. suggests that there is a price differential between the two channels, which could lead to consumer channel switching. In this case, the retailer might implement a differentiated pricing strategy to attract consumers. reflects a certain level of synergy between the two channels in the dual-channel supply chain. For instance, consumers may first experience products offline and then purchase them through the online channel. represents the wholesale price set by the manufacturer. denotes a simplified model of the offline retailer’s service level, which is operational and helpful in analyzing how changes in service levels affect consumer demand, pricing strategies, and other factors. indicates moderate consumer sensitivity to service deficiencies, meaning that a decrease in service level leads to a certain reduction in demand but not an extreme reaction. First, the situation when the over-service sensitivity coefficient is low is studied, let . Since and represents the over-service sensitivity coefficient, a value of indicates a relatively low sensitivity. The over-service sensitivity coefficient significantly influences the retailer’s decisions regarding service level selection, cost control, and pricing strategy. Based on the demand’s sensitivity to service, the retailer must find a balance between enhancing service levels and controlling costs in order to maximize competitiveness and profitability in the market. The relationship between the selling price, service level, and customer service expectations is shown in Figure 2. As customer service expectations change, both the sales price and service level adjust accordingly. As can be seen from Figure 2, when the over-service sensitivity coefficient is low, initially, as the customer’s desired service (DS) increases, both the manufacturer’s optimal selling price and the offline retailer’s optimal service level rise. As the DS increases beyond the threshold value (i.e., ), offline retailers turn to focus on the AS of customers due to the negative externality effect of under-service outweighing the negative externality effect of over-service to prevent the demand loss from under-service, and, due to the existence of service cost, the offline retailer does not continuously raise both the price and service level. So, when the customer’s minimum acceptable service expectation rises, neither the price nor service levels will increase.

Figure 2.

Correlation of and with .

As stated in Corollary 1, for electronic products with low customer service expectations prior to being delisted, manufacturers, leveraging the positive externality of services, will lower prices and pass some of the benefits to offline retailers. This reduces the retailers’ reluctance to improve service levels due to associated costs, enabling them to provide service levels that exceed customer expectations. As shown in Proposition 4, the manufacturer’s optimal pricing has stability for the offline retailer’s optimal service level. In the range of , offline retailers will select a service level equal to the lowest acceptable service expectation, irrespective of the manufacturer’s pricing. Within , offline retailers will select a service level equal to the highest acceptable service expectation, irrespective of the pricing set by the manufacturer.

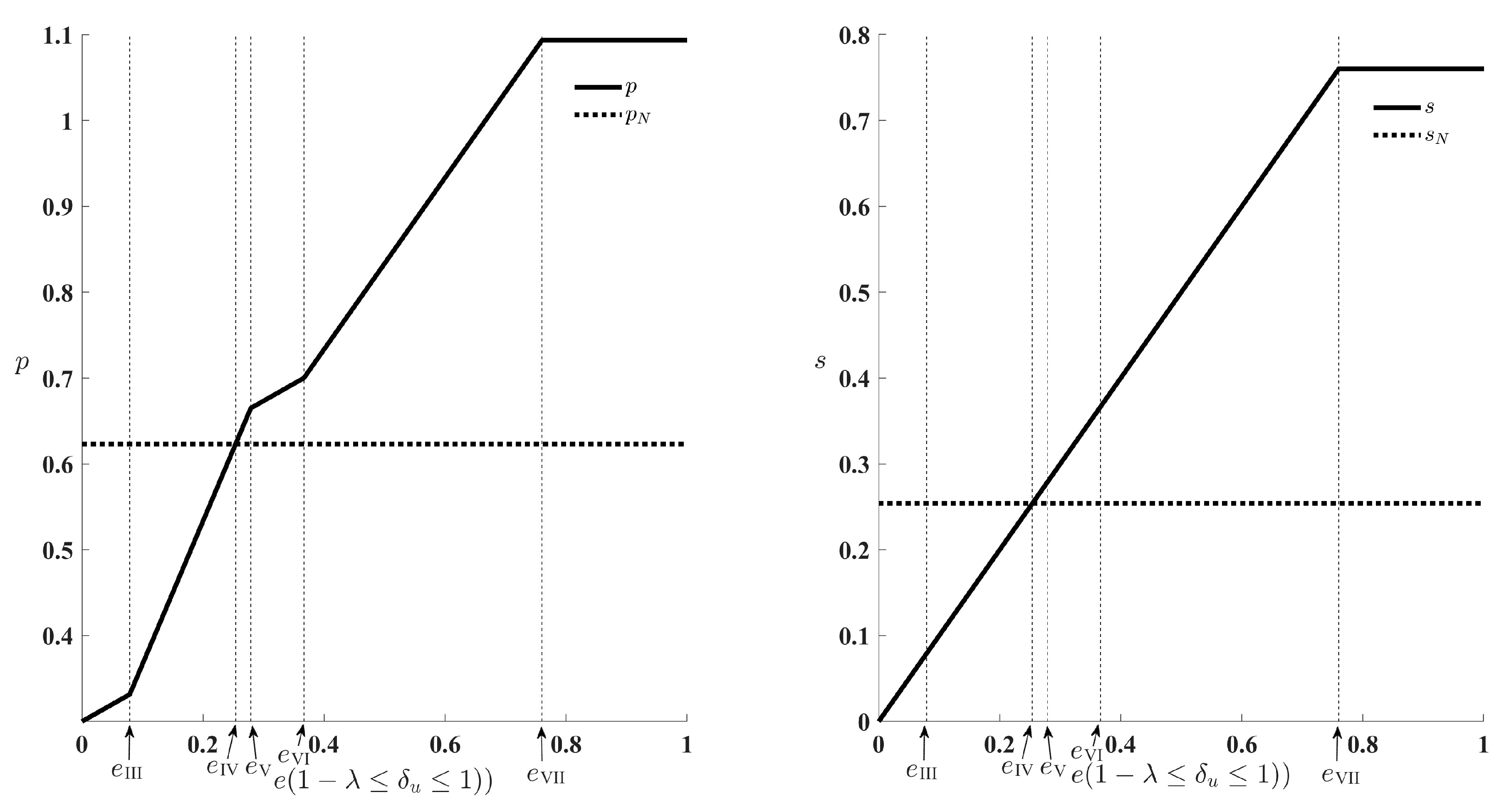

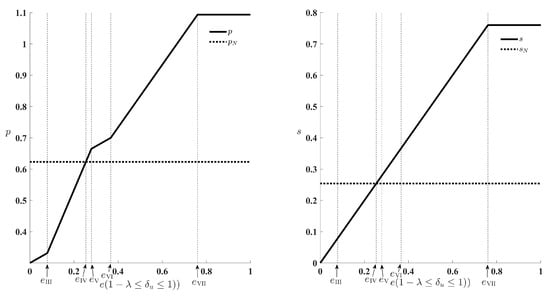

Secondly, in the situation when the over-service sensitivity coefficient is high is investigated, let . The relationship between selling price, service level, and customer service expectation is shown in Figure 3. According to Figure 3, compared with Figure 2, offline retailers will not provide a higher service level than customer service expectations, and manufacturers will not reduce prices due to the higher sensitivity coefficient of over-service and the higher negative externality of over-service. The manufacturer’s optimal pricing also exhibits stability with respect to the offline retailer’s optimal service level. In the range of , regardless of how the manufacturer sets the pricing, the offline retailer will choose a service level equal to the service expectation. And there is a wider range of service decision stability compared to Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Correlation of and with .

From Figure 2 and Figure 3, it can be found that the prices and services in the case of considering the zone of service tolerance are different from those in the case of not considering the zone of service tolerance. Considering the zone of service tolerance scenario, the price and service are lower than the non-consideration scenario due to the existence of customers’ service expectations, especially when customers buy delisted daily necessities and electronic products such as mobile phones, which have lower service expectations. And, if the price and service level are too high, more customers will be lost, and profits will be reduced. For the newly listed daily necessities and electronic products such as mobile phones, the service expectations are improved, and manufacturers and offline retailers can appropriately increase the price and service level to reduce the impact of under-service and increase profits. Hence, the price and service are higher than without consideration.

6. Conclusions, Managerial Insights, and Future Research

6.1. Conclusions

In dual-channel retail, when the service provided is lower than AS (adequate service), the utility of customer satisfaction is not achieved. However, with the increase in services, the actual service level is higher than the DS (desired service) due to the law of diminishing marginal utility, which instead reduces customer utility. This suggests that, beyond a certain point, additional service offerings may not enhance and could even detract from customer satisfaction. Retailers should carefully balance service levels to avoid over-investment in services that offer diminishing returns, ensuring that service offerings are aligned with customer preferences and maximize overall value. That is, there is a zone of service tolerance for customers, which refers to the range between the DS (desired service) and AS (adequate service) levels, within which customers consider the service to be acceptable. Existing research has not incorporated customers’ service tolerance domains into the pricing and service decision-making framework of dual-channel supply chains. Specifically, He et al. (2022) [1] only investigated adequate service in the context of dual-channel supply chains without addressing the desired service. Therefore, this study aims to fill this gap by incorporating the desired service into the framework for further investigation. In response to this issue, this paper converts the zone of service tolerance into customer service expectations and incorporates it into the pricing and service decision-making framework of a dual-channel supply chain consisting of an online-channel manufacturer and an offline retailer. This paper explores the influence mechanism of customer service expectations and service sensitivity coefficients on the optimal decisions of dual-channel supply chain members. The conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- When the price cross-elasticity between channels is within a certain range, regardless of whether it is daily necessities or electronic products such as mobile phones, there exists a linkage mechanism between the manufacturer’s optimal sales price and the offline retailer’s service level. The price cross-elasticity between channels ensures that the manufacturer’s pricing mechanism influences the offline retailer’s service decisions. When the desired service level is low, the manufacturer, in order to encourage the offline retailer to improve service levels, will lower the sales price to compensate for the demand loss caused by the offline retailer’s over-service. Hence, lower selling prices lead to lower service levels, and vice versa when AS is higher.

- (2)

- For the electronic products to be delisted, offline retailers will likely provide over-service, and offline retailers will take on the risk of customer loss and adopt a small profit and quick sales strategy to sell products that are about to be delisted. Customers are more familiar with the products that are to be withdrawn from the market. Their shopping habits make the expectation of the highest acceptable service low. They do not expect service personnel to cross the “interpersonal distance zone”, which will make their shopping unpleasant. However, to upgrade the products, offline retailers strongly recommend customers buy the products that will be delisted and often provide a service level higher than the expectation of the highest acceptable service.

- (3)

- For newly listed electronic products or daily necessities, there is a possibility of under-service provided by offline retailers. Offline retailers will take the risk of customer loss and adopt a profitable and marketable strategy to sell newly listed electronic products. Customers are unfamiliar with the newly listed products, and their AS is high due to their shopping habits. They hope to receive more personalized and refined services. However, due to service costs, offline retailers will not blindly satisfy customer needs and often provide service levels below customers’ expectations.

- (4)

- When the over-service sensitivity coefficient falls within a specific range of desired or adequate service, the optimal service level offered by offline retailers remains stable in relation to the manufacturer’s optimal selling price, which significantly simplifies the offline retailer’s optimal service level decision. In other words, when offline retailers are aware of customer expectations, they can directly deliver the desired service level without needing to factor in the manufacturer’s pricing strategy.

6.2. Managerial Insights

Based on our theoretical exploration of the zone of service tolerance in dual-channel supply chains, our findings provide two key managerial insights into which strategies firms should adopt.

First, optimize the linkage strategy between pricing and service levels. For example, in retail channels, Apple adjusts its pricing based on varying service experiences and customer demand. In flagship stores, Apple offers customized services, technical support, and superior customer experiences while maintaining higher product prices. This strategy ensures a match between high-priced products and high-quality services, enhancing consumer purchase intent and fostering customer loyalty. Firms should recognize an important linkage between manufacturers’ pricing strategies and offline retailers’ service levels. When the price cross-elasticity coefficient between channels is moderate, manufacturers can influence offline retailers’ service decisions by adjusting sales prices. When service demand is low, lowering the selling price to incentivize retailers to improve service levels is an effective strategy. This linkage mechanism makes it necessary for firms to fully consider offline retailers’ service capabilities and customers’ service expectations when formulating pricing strategies, thus forming a complete set of market strategies to enhance overall customer satisfaction and market competitiveness.

Second, the dynamic management of customer service expectations: For products at different life cycle stages (e.g., products that are about to be retired or have just been launched), firms must flexibly adjust their service strategies to meet customers’ expectations. This can be achieved through methods such as data analytics or customer surveys, which allow for the continuous monitoring and alignment of services with evolving customer needs, thus enhancing the effectiveness of the strategy. For products about to be retired from the market, customers’ expectations of service are low, so retailers must carefully balance service levels to avoid over-service that causes customer discomfort. For newly launched products, customers expect a higher level of service, and retailers should consider investing more in service to meet customer demand. Firms should regularly assess customers’ service tolerance for different products to dynamically adjust their service strategies to ensure that retailers’ service levels are in line with customers’ expectations, thereby enhancing customer loyalty and brand image.

6.3. Future Research

This paper only considers a supply chain system consisting of an offline retailer and a manufacturer with an online channel. Future research could extend this model to include online channels or multi-channel supply chains, exploring how the integration of digital platforms might influence pricing, service levels, and overall supply chain efficiency. However, the sales platform is receiving more and more attention now, and future research should consider the role of the sales platform. In addition, the specific criteria of the DS or AS mentioned in this paper have not been clarified in different industries. Future empirical research could test this framework within specific sectors, such as the airline industry and FMCG (Fast-Moving Consumer Goods), to examine how service level criteria vary and how the framework can be adapted to the unique dynamics of each industry and provide more targeted guidance for theory and practice. Finally, the research of this paper mainly focuses on the competitive relationship between offline retailers and manufacturers that open up online channels. Still, the cooperation between the two should not be ignored. Future research could explore the cooperative relationship between offline retailers and manufacturers that open up online channels, especially how to establish an effective coordination mechanism to achieve a win–win situation. This could be approached through methodologies such as case studies or simulations, which would allow for a deeper understanding of the dynamics and challenges in these partnerships, providing valuable insights into effective collaboration strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.H.; methodology, Q.H.; software, X.L.; validation, Q.H.; formal analysis, X.L.; investigation, X.L.; resources, Q.H.; data curation, Q.H.; writing—original draft preparation, P.W.; writing—review and editing, P.W.; visualization, P.W.; supervision, Q.H.; funding acquisition, Q.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by a research grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72161004) and the Key Special Project of Guizhou University’s Research Base and Think Tank (No. GDZX2021033).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hsiao, L.; Chen, Y.J. Strategic motive for introducing internet channels in a supply chain. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2014, 23, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, F.; Kök, A.G.; Martínez-de-Albéniz, V. The future of retail operations. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2020, 22, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.I.; Chan, H.J. Perceived service quality and self-concept influences on consumer attitude and purchase process: A comparison between physical and internet channels. Total Qual. Manag. 2011, 22, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkadir, S.I.; Bawa, S.A.; Arunkumar, S. A Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards Online And Offline Shop**. Library of Progress-Library Science. Inf. Technol. Comput. 2024, 44, 15292. [Google Scholar]

- He, Q.; Shi, T.; Wang, P. Mathematical modeling of pricing and service in the dual channel supply chain considering underservice. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.Y. Improving importance-performance analysis: The role of the zone of tolerance and competitor performance. The case of Taiwan’s hot spring hotels. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Berry, L.L.; Zeithaml, V.A. Understanding customer expectations of service. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 1991, 32, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Chung, J.E.; Suh, Y.G. Multiple reference effects on restaurant evaluations: A cross-cultural study. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1441–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. An applied service marketing theory. Eur. J. Mark. 1982, 16, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A. A Conceptual Model Service Quality and Its Implications for Future Research. J. Mark. 1985, 42, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim CK, B.; Chan, K.W.; Hung, K. Multiple reference effects in service evaluations: Roles of alternative attractiveness and self-image congruity. J. Retail. 2007, 83, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobadian, A.; Speller, S.; Jones, M. Service quality. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 1994, 11, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratminingsih, S.A.; Astuty, E.; Widyatami, K. Increasing customer loyalty of ethnic restaurant through experiential marketing and service quality. J. Entrep. Educ. 2018, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Öztürk, R. Exploring the relationships between experiential marketing, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty: An empirical examination in Konya. Int. J. Soc. Behav. Educ. Econ. Bus. Ind. Eng. 2015, 9, 2817–2820. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira AS, D.; Souki, G.Q.; Silva, D.D.; Rezende, D.C.D.; Batinga, G.L. Service guarantees in an e-commerce platform: Proposition of a framework based on customers’ expectations, negative experiences and behavioural responses. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2023, 15, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veas-González, I.; Carrión-Bósquez, N.G.; Serrano-Malebran, J.; Veneros-Alquinta, D.; García-Umaña, A.; Campusano-Campusano, M. Exploring the moderating effect of brand image on the relationship between customer satisfaction and repurchase intentions in the fast-food industry. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 2714–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunga, R.S. How Service Quality is Able to Influence Customer Satisfaction Through the Trust of Traveloka Application Users in Indonesia. KnE Soc. Sci. 2023, 9, 223–241. [Google Scholar]

- Golalizadeh, F.; Ranjbarian, B.; Ansari, A. Impact of customer’s emotions on online purchase intention and impulsive buying of luxury cosmetic products mediated by perceived service quality. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2023, 14, 468–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Hur, Y. Service quality and complaint management influence fan satisfaction and team identification. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2019, 47, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C.; Dedeoğlu, B.B.; Fyall, A. Destination service quality, affective image and revisit intention: The moderating role of past experience. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polas MR, H.; Raju, V.; Hossen, S.M.; Karim, A.M.; Tabash, M.I. Customer’s revisit intention: Empirical evidence on Gen-Z from Bangladesh towards halal restaurants. J. Public Aff. 2022, 22, e2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balinado, J.R.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Young, M.N.; Persada, S.F.; Miraja, B.A.; Redi, A.A.N.P. The effect of service quality on customer satisfaction in an automotive after-sales service. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, J.S.; Nicolau, J.L. Understanding the dynamics of the quality of airline service attributes: Satisfiers and dissatisfiers. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, M.P.; Kumar, G.; Ramkumar, M. Customer expectations in the hotel industry during the COVID-19 pandemic: A global perspective using sentiment analysis. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2023, 48, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, T.; Cheung, C. The effects of over-service on restaurant consumers’ satisfaction and revisit intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 122, 103881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y. A supply chain model with direct and retail channels. Rairo Rech. Opérationnelle 2012, 46, 159–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Ray, G.; Geng, X.; Whinston, A. Implications of reduced search cost and free riding in e-commerce. Mark. Sci. 2004, 23, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J. How does free riding on customer service affect competition? Mark. Sci. 2007, 26, 488–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, D.; Liu, T. Sales effort free riding and coordination with price match and channel rebate. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 219, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, B.; Xu, G.; Liu, C. Pricing policies in a dual-channel supply chain with retail services. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 139, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Pauwels, K.; Peng, C. The impact of adding online-to-offline service platform channels on firms’ offline and total sales and profits. J. Interact. Mark. 2019, 47, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Ma, H.; Zhao, M.; Fan, T. Group Buying Pricing Strategies of O2O Restaurants in Meituan Considering Service Levels. Systems 2023, 11, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Wang, Q.; Liu, H.; Li, Q. The value of buy-online-and-pickup-in-store in omni-channel: Evidence from customer usage data. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2020, 29, 995–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, L.; Lim, A. Optimal pricing decisions for an omni-channel supply chain with retail service. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2020, 27, 2927–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Cao, B.; Xie, W.; Zhong, Y.; Zhou, Y.-W. Impacts of pre-sales service and delivery lead time on dual-channel supply chain design. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 147, 106579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Lu, Y.; Liu, B. Pricing decisions and game analysis on advanced delivery and cross-channel return in a dual-channel supply chain system. Systems 2023, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Shao, Z.; He, Y. Effect of the buy-online-and-pickup-in-store option on pricing and ordering decisions during online shopping carnivals. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2021, 28, 2496–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]