Abstract

The Circular Economy (CE) has evolved as a philosophy to transform industrial supply chains to become greener to combat climate change issues. Countries’ target of achieving Net Zero will never be fulfilled unless, along with larger organizations, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are decarbonized, as more than 90% of the world’s businesses are SMEs. Although, recently, there have been many studies on SMEs’ sustainability practices and performance covering drivers, bottlenecks, and opportunities, the holistic approach for embedding circular economy and sustainability covering design, planning, implementation, and operations is missing. This research bridges this knowledge gap by revealing trends and theories of circular economy adoption in SMEs. Additionally, this research derives the drivers/enablers, issues, and challenges and determines strategies, resources, and competencies for CE adoption in SMEs. This study concludes with a consolidated framework comprising factors and methods for CE implementation in SMEs. This entire piece of research has been undertaken using the secondary data analysis method through the content analysis of 188 published articles in highly ranked peer-reviewed journals.

1. Introduction

Small and medium-sized businesses need to be a part of carbon reduction plans with proper support from large corporations. This is vital if developed and emerging economies are targeting to become carbon neutral by 2050. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are vital for both developed and emerging economies, as well as an important part of the supply chain. Around 90% of the world’s business happens through SMEs, and they employ almost 60% of the world’s employable population (http://www.thefsegroup.com/definition-of-an-sme/ (accessed on 11 October 2023)). While SMEs contribute to the economies of countries, they also contribute to 70% of the global pollution. It is further observed that manufacturing SMEs contribute almost 65% of the air pollution, which is mostly due to limited compliance towards environmental management systems [1], amongst other factors. As SMEs are growing in importance for economies, so are the challenges for them in terms of environmental concerns. So, SMEs need to rethink and redesign their business models to respond to and overcome emerging challenges [2,3]. In such circumstances, the adoption of circular economy (CE) principles by SMEs could be a strategy to overcome business challenges and ensure economic growth.

According to Boulding [4], an ecological economist, we need to follow the pattern of the earth’s closed economic system and develop a circular economic system to increase the sustainability of human life. Building on this initial concept, Segerson et al. [5], in their theoretical framework, explained the need to shift from an open-ended economic system to a CE system. The CE has now come a long way and changed the manner of interaction between human society and nature [6]. The focus of the CE has also gone through a paradigm shift with a focus on sustainable development at the micro (enterprises and consumers), meso (economic agents integrated into symbiosis), and macro (cities, regions, governments) levels [7]. The attainment of a circular model also requires innovation in cyclical and regenerative ways, following the ways in which society produces, consumes, and legislates. According to [8], the CE constitutes emerging components—energy and resource recirculation, resource demand minimization, recovering value from waste through either reuse, reduction, or recycling, and a multi-level approach to achieving sustainable development through closely connecting with societal innovation.

In the last decade, there has been considerable research on CE. Several review papers have been published focusing on the factors related to sustainability linked to the concept of CE. The review of sustainability has mainly focused on barriers or challenges related to sustainable development [9] or the adoption of Lean practices to facilitate sustainable development [10]. There are also some reviews on sustainable development in SMEs focusing on drivers, motivators, and financial performance [11,12,13]. The reviews on the CE are more related to understanding the drivers, barriers, challenges, business models, and practices [14,15,16,17] required for its adoption. Another aspect of these reviews is to focus on sectors such as manufacturing, supply chains, or SMEs [18,19,20,21]. There are also reviews that focus on the product–service system in order to achieve resource efficiency through CE adoption [22] or to understand the interplay between environmental and economic systems as a result of CE adoption [23]. Unlike reviews on sustainability, there are limited reviews focusing solely on the adoption of the CE in SMEs.

The literature reflects the exploratory nature of research to understand CE adoption in different environments. This is reflected in a multitude of articles on qualitative studies and research questions asking more “What” than “How” questions. A lot of theories have also been applied to explain the CE adoption phenomenon in different contexts. These include the systems theory, resource-based view, and stakeholder theory in the context of CE adoption in the supply chain [24,25,26,27]. Further, a considerable focus of research has been to understand the building blocks, such as drivers, enablers, barriers, challenges, and practices, of CE adoption. Some of the major enablers highlighted in the literature relate to customer awareness, environmental safeguards, economic considerations, policy, and regulations [28,29,30]. Some of the barriers or challenges relate to resource constraints and external factors, such as government regulations, training requirements, and initial investments [19,31,32].

The above analysis shows that, although a considerable amount of research exists on CE adoption, there is still a lack of research focused on understanding its adoption mechanisms in the supply chain specifically linked to SMEs and CE adoption. The current policies and regulations, as well as government support, are not adequate for SMEs; hence, there is a need for a focused understanding of the adoption of the CE in the SME context. Although there is research on CE adoption in larger organizations (e.g., [33]), studies on SMEs’ adoption of the CE are scant [34]. There is also a lack of research on integrated approaches to the successful implementation of the CE in manufacturing SMEs in both developed and emerging economies [35].

Accordingly, the aim of this review paper is to create an opportunity to fill the gaps in the existing literature by assembling conceptual, theoretical, and empirical developments related to the topic of the CE in SMEs from a multi-disciplinary perspective. While doing so, we reveal areas of research related to the CE in SMEs that have been largely overlooked. Conducting a structured literature review, using secondary data from published articles in peer-reviewed journals published between 2010 and 2024 through content and meta-analysis, we address the below Research Questions (RQs).

RQ1: What are the emerging trends and theories applied in the research of CE adoption in SMEs?

RQ2: What are the drivers/enablers, issues, and challenges linked to the adoption of the CE in SMEs?

RQ3: What strategies (e.g., energy and resource efficiency, waste management, wellbeing, corporate social responsibility), practices, and frameworks are utilized for CE adoption in SMEs?

By answering the research questions, this paper makes the following contributions. The literature so far has mostly focused on supply chains or large corporations. Thus, our review identifies specific drivers, challenges, and strategies related to the CE in SMEs. There are existing papers on the implementation of the CE from a supply chain perspective. This study helps in the adoption of the CE from an SME perspective through a framework grounded in the literature.

Section 2 presents the methodology for selecting the relevant papers for undertaking this review and a framework for analyzing the research questions. Section 3 analyses the selected papers following the proposed framework. Section 4 discusses the findings in line with the research questions. Section 5 presents propositions for future research on SMEs’ adoption of the CE and concludes the analysis.

2. Literature Review

This section provides an overview of the existing research on the CE and sustainability and reveals the emerging knowledge gaps. Literature reviews in the field of the CE started around 2008 but picked up from 2014 onwards [19] (refer to Table S1 in Supplementary File). The existing literature review papers have been critically examined to establish the rationale for the necessity of this review paper.

We initially focused our review only on SMEs but found that there were no review papers on CE adoption in SMEs prior to 2020. The reviewed papers on sustainability focus on drivers and barriers related to SMEs as well as identifying these, such as innovation and green management, affecting financial performance. Though there are some articles about sustainability and SMEs, the articles on sustainability and SMEs focus mainly on innovation [11], drivers [12], barriers [9], Lean practices, and sustainability [36]. In the case of the review on CE, there were no articles on SMEs, but, rather, they focused mainly on business models [14,16,37,38], adoption in manufacturing [18,20], or supply chain context [19].

A significant gap exists in understanding the financial impacts of circular business models, especially during the design, implementation, and evaluation phases. The literature lacks detailed strategies for CE implementation across different organizational levels, suggesting a need for models that address micro, meso, and macro-level challenges. Geographical variations in the barriers and enablers of CE, particularly outside of contexts such as Chinese SMEs, are underexplored. Moreover, there is a scarcity of empirical studies on CE implementation tools and a need for more in-depth research in circular finance within supply chains. Studies on the systematic application of circular practices in different industries, such as the automobile industry, are also lacking. These gaps underscore the need for more comprehensive, practical frameworks for CE, particularly in SMEs, and a deeper understanding of the integration of circular economy principles into competitive strategies without compromising economic growth.

In order to understand the landscape of circular economy adoption in SMEs, we looked at the highly cited articles in this area. We observed that most of these articles are empirical papers that have reported on enablers, challenges, and strategies as observed from practice. Another set of papers focused on SDGs and circular business models. Table 1 below provides a list of highly cited papers on CE adoption in SMEs as per the Web of Science.

Table 1.

Highly cited articles on CE adoption in SMEs.

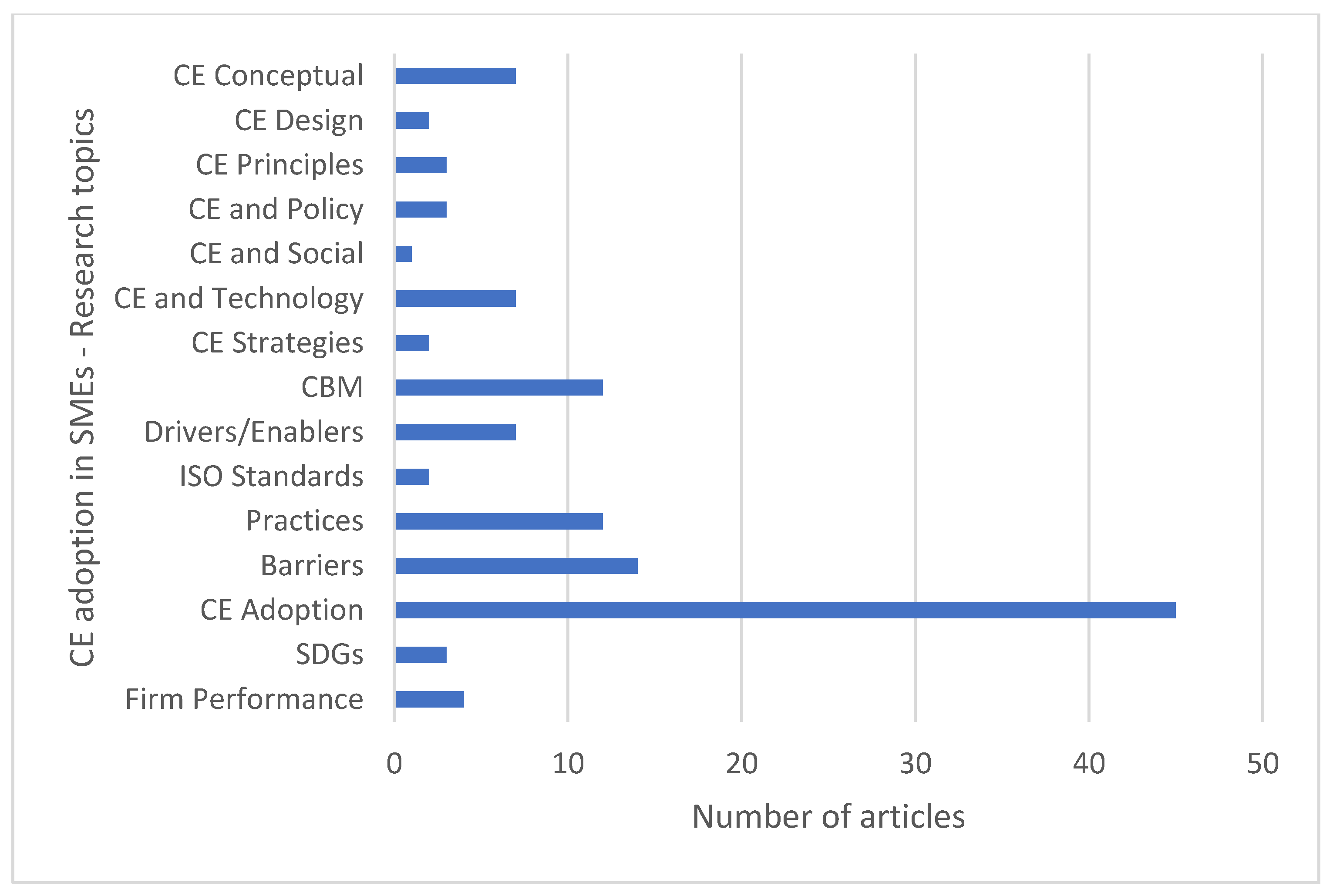

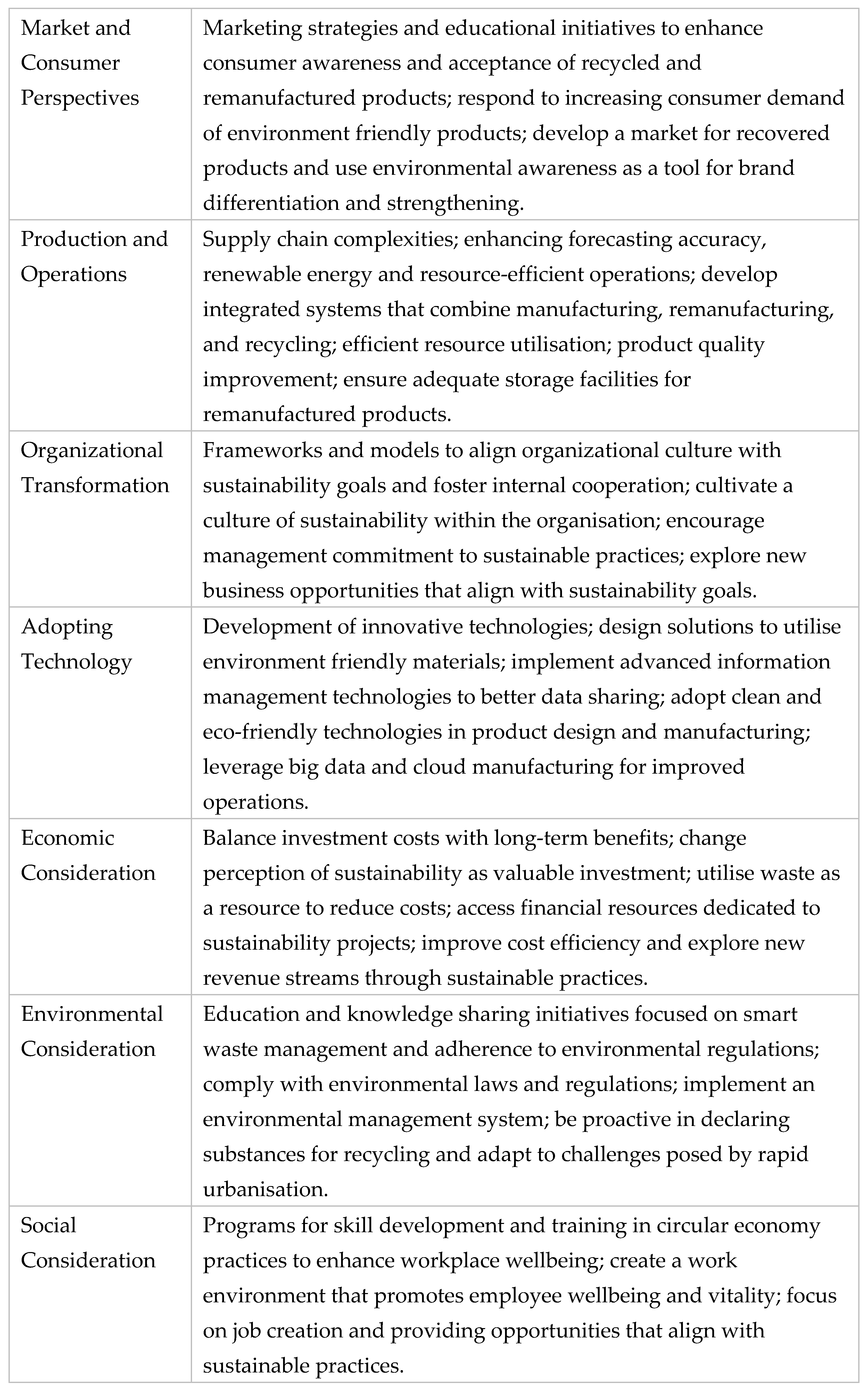

To better understand the state of CE adoption in SME research, we also explored the topic focus of the articles published. From Figure 1, we can observe that the highest number of articles have explored CE adoption aspects such as the Lean green approach [10], resource efficiency [22], remanufacturing capability [25], etc., in SMEs. There are a few articles that focus on the conceptual aspect of CE, but the majority of other articles explore, either theoretically or empirically, topics such as CE practices, CE enablers, circular business models, barriers, and technology (digitalization or Industry 4.0). Thus, we can see that there is still divergence on topics published on CE adoption in SMEs, but, in the last few years, from 2021 onwards, there has been growing convergence on topics and an increased number of empirical works in this area.

Figure 1.

The research topics on CE adoption in SMEs (Authors’ own conception).

Further analyses of the review papers specifically focusing on CE adoption in SMEs provided a handful of articles. Most of these articles were published between 2021 and 2023. Table 2 below provides a list of these articles and their focus areas.

Table 2.

Review papers on CE adoption in SMEs.

The above table shows that most of the review papers about CE adoption in SMEs are focused on business models except [21], which provides insight into enablers and challenges. This shows that there is a need for an updated review that focuses on drivers, barriers, practices, actions, etc., from the SME perspective and includes the findings from empirical works performed in this period. Another aspect that is missing is a robust framework [46] that can enable the adoption of the CE and objectively deriving solutions to successfully achieve higher sustainability performance. This is an important consideration when discussing CE adoption in SMs. A list of the review papers on sustainability and the circular economy with their focus area is presented in Table S1.

3. Methodology

This study adopts a structured literature review approach. To achieve the aims of the research the authors have adapted the systematic review procedures outlined by [49] that consist of three stages: planning, execution, and reporting. The approach has been followed to combat the potential effect of researchers’ bias and to ensure that a traceable path has been followed. One of the advantages of undertaking the systematic review approach is to become aware of the breadth of research and the theoretical background in a specific field [50]. Researchers believe that it is very important to conduct a systematic review in any field, specifically to understand the level of previous research that has been undertaken and to know about the weaknesses and areas that need more research [51]. Further, to ensure that the systematic literature review is valuable for the readers, we prepared a transparent, accurate, and complete account of why the review was performed, what process is that we followed, and the present findings based on the suggestions by [52]. In order to achieve up-to-date reporting guidance, we also followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement published in 2020. As mentioned by [52], “familiarity with PRISMA 2020 statement is useful when planning and conducting systematic reviews to ensure that all recommended information is captured”.

3.1. Material Collection

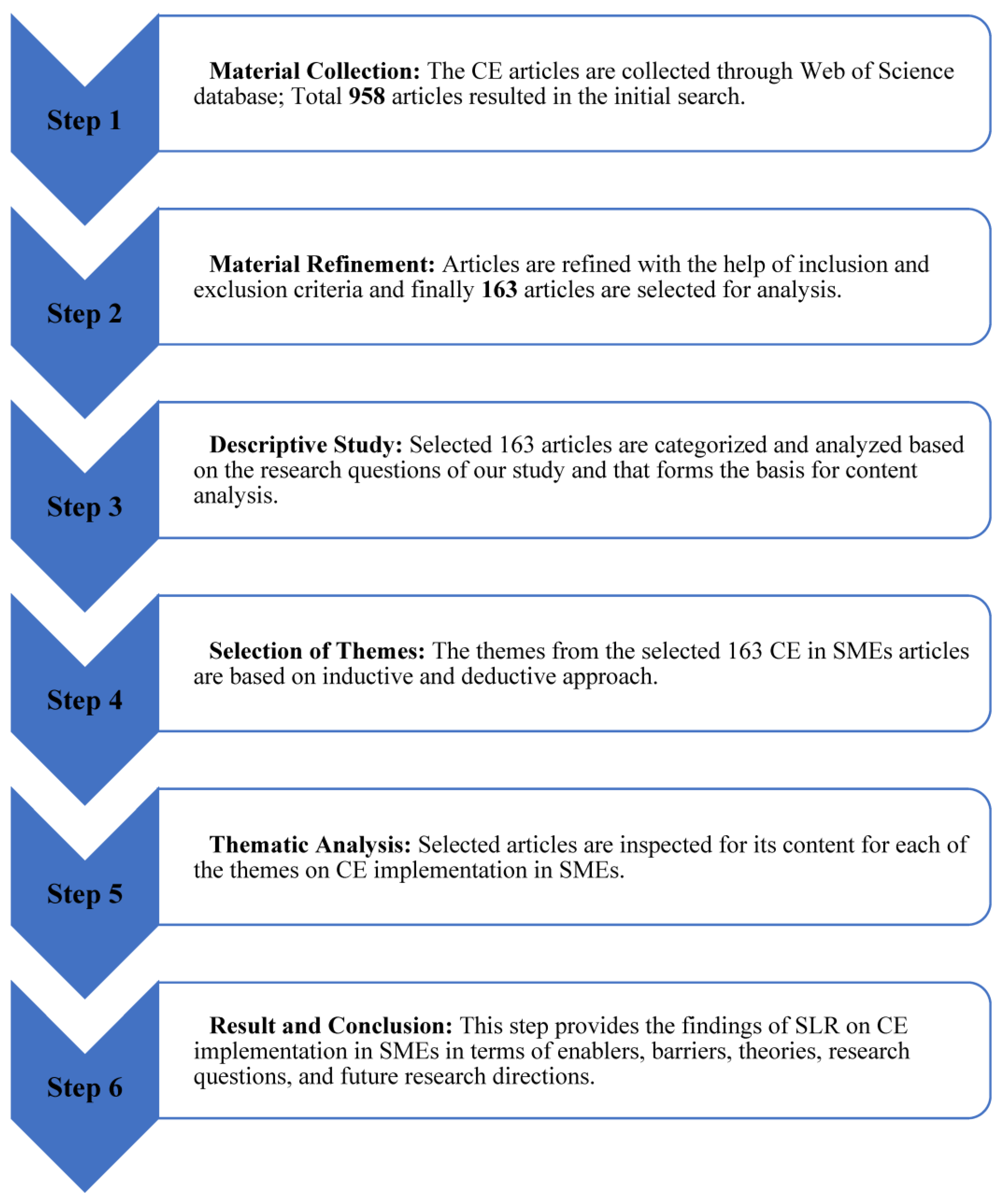

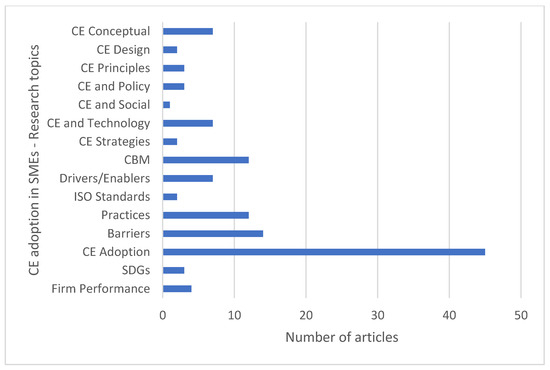

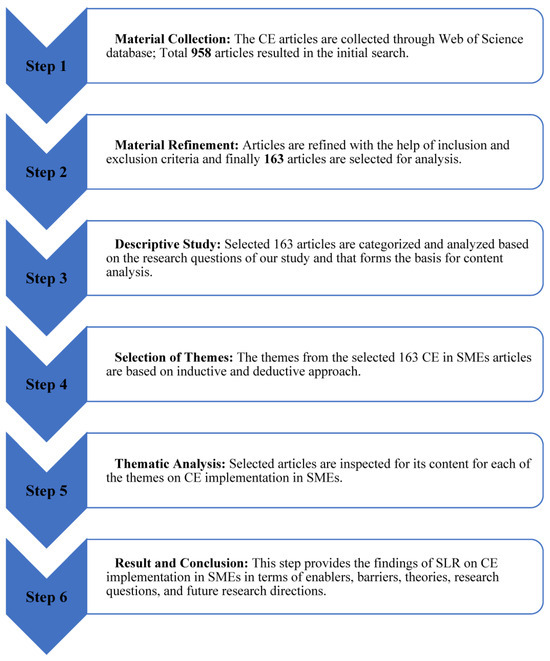

The articles related to the CE were collected from the Web of Science. The period of collection of articles was from 2008 to 2024. During this period, we found that the focus of CE research has been on supply chain management and, primarily, SMEs. Though the number of papers specifically focused on SMEs we found was limited, our initial search focused mainly on CE, but, later, we refined our search based on the developed research questions and focus of our study. The steps we followed in this regard are presented in Figure 2. Figure 3 presents the article selection process we followed.

Figure 2.

The analysis process (Authors’ own conception).

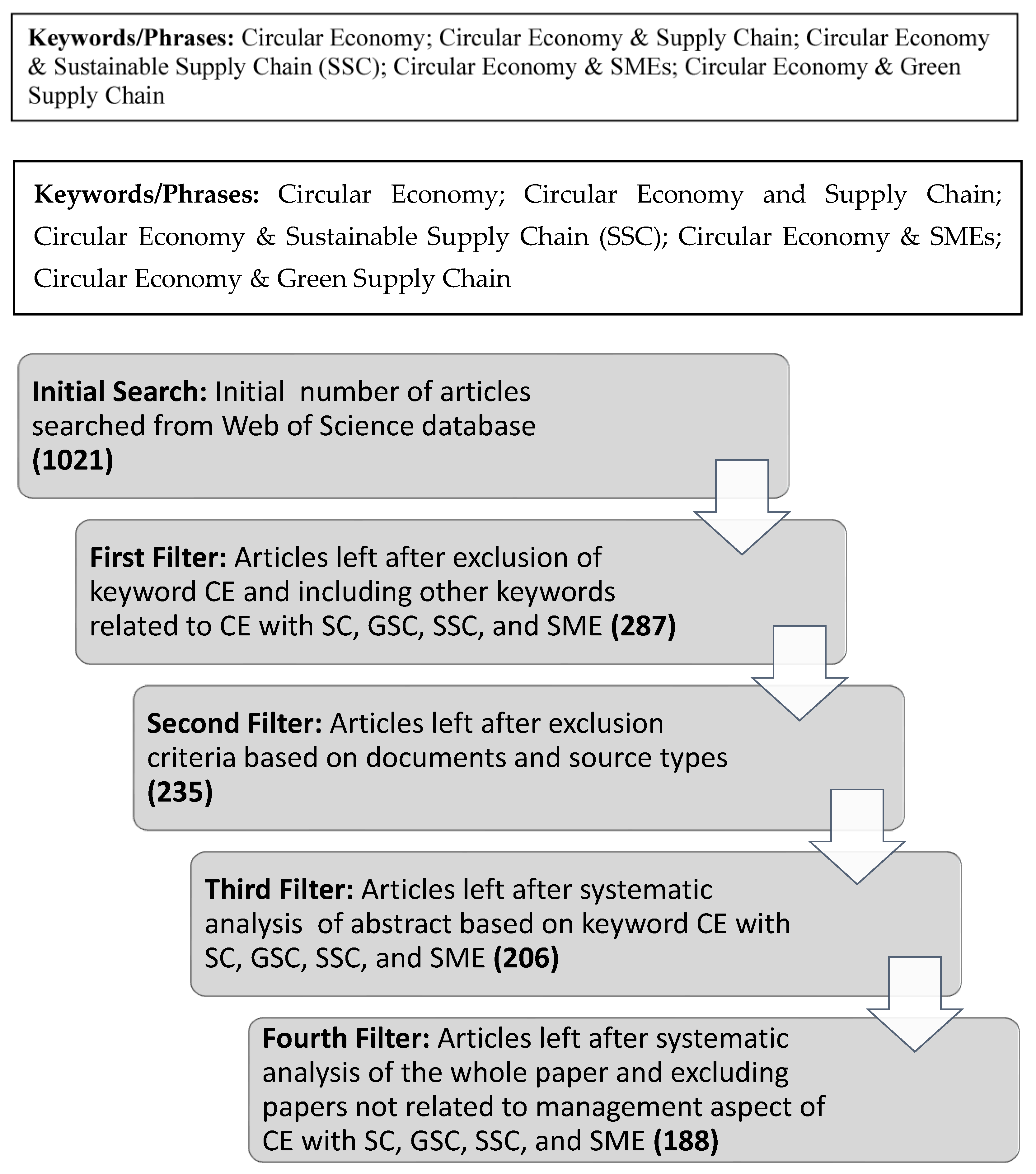

Figure 3.

Article selection process (Authors’ own conception).

3.2. Article Selection

The first set of articles is identified based on the keyword/phrase “circular economy”. This helped us understand the breadth of publications on the topic. In the next stage, we started narrowing down our search based on the focus of our study and aligned with our research questions. This focused search helped us to reduce the number of articles to 287 from the initial 1021. The next phase of the search focused on only peer-reviewed journal articles, eliminating editorials, book reviews, academic dissertations, textbooks, and working papers, or any other form of grey literature.

The articles were selected from double-blind, peer-reviewed journals, as they are known sources of valuable knowledge [53] and are also helpful in setting up the theoretical and empirical work undertaken in the research domain [54]. In this phase, we also looked into the major journals in the field to enhance the coverage of our review and included additional articles that might have been excluded in the first instance [55,56]. The authors also cross-checked with prior reviews and undertook manual searches of different citations and reference lists from selected articles in an attempt to minimize the number of articles that were omitted due to human error [56,57]. For this, manual searches of several reference lists were carried out from the selected papers to identify additional relevant papers that are covered under the defined selection criteria.

The last two phases of the methodology focused on the selected papers (235 papers) from the previous phase. Now, the focus is more on the contents of the articles. Starting with Abstracts, we wanted to understand whether these papers are relevant to our aim and to address our research questions. Each researcher went through the contents and, when there was an agreement about the relevance of the article for our study, those were included. There were some articles for which we were not sure (based on the abstract), so those articles were taken to the final phase of our selection process. The final phase required us to extensively go through the articles to closely scrutinize them and ensure that our study includes the most relevant articles required to answer our research questions. One of the key eliminating factors of the articles in the final phase was articles that have an engineering orientation, such as papers focused on chemical engineering processes or thermodynamics-based papers (aligned with mechanical engineering). Finally, we ended up with 188 articles which were then analyzed. Descriptive analyses focused on trends, research methodology, and theories applied in these articles. The purpose was to understand the current scenario and how we can interpret the progress in the field based on these trends.

More in-depth content analyses were further carried out to understand the major themes of the articles published in the areas of green supply chain, sustainable supply chain, and circular supply chain. The content analysis was followed by a meta-analysis of the literature. Finally, a conceptual framework was developed. The objective is to understand these themes in a broader supply chain context and then develop a conceptual underpinning for SMEs.

4. Current Trends of Circular Economy Research in SMEs

4.1. Content Analysis

Content analysis focused on addressing our three research questions. The initial part of the analysis focused on descriptives such as trends, research questions examined, research methodologies adopted, and theories utilized for research. This helped us to understand the nature and theory stage [58] of CE adoption research in SMEs. We observed an increasing trend in CE adoption in SMEs, though the focus is still very much on the overall supply chain. An analysis of the research questions and methodologies helped us to realize that the focus of CE adoption research is still at a nascent stage [58], with more focus on exploratory qualitative case studies. A detailed discussion of content analysis is provided in the sections below.

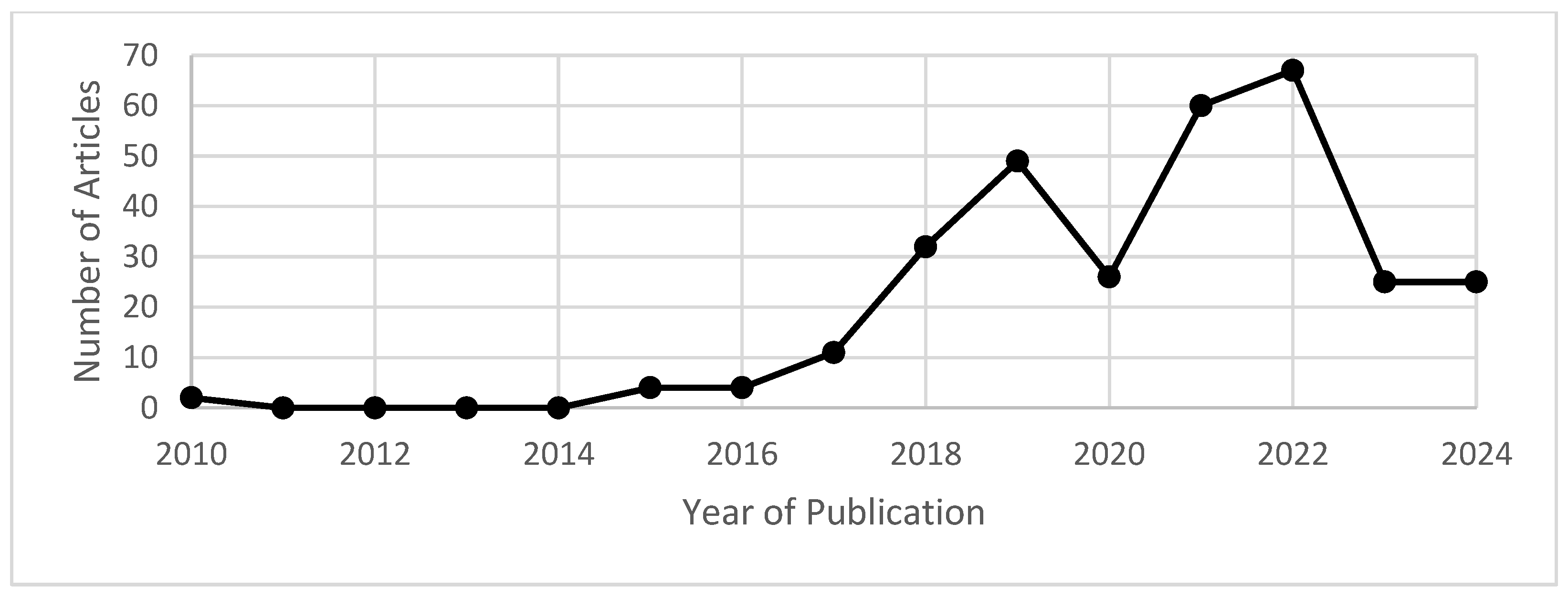

Trends

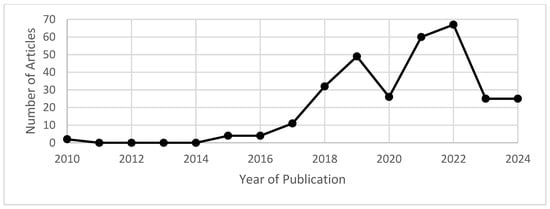

The research on the CE has grown exponentially in the last decade. However, the focus of the research has been more generic and mostly in the areas of engineering and biological sciences [19]. As can be seen from Figure 4, there is an increasing trend in the number of articles from 2016 onwards. This period has seen an increase in review articles too. The reviews are mainly focused on CE implementation in green supply chains, circular supply chains, and sustainable supply chains. In the last three years, there has been an increase in the number of articles that explore drivers, practices, and challenges not only from the supply chain perspective but also from the SMEs’ context.

Figure 4.

Publication trend on CE implementation in supply chain (Authors’ own conception).

4.2. Research Questions Addressed by Previous Research

Research Questions

One of the first aspects that we wanted to investigate was the research questions of the articles which were focused on CE implementation in the supply chain or SME context. This helped us understand the focus of the articles.

Looking at the research questions (see Table S2) helps us to understand that researchers have focused on CE implementation in the supply chain from various lenses. One lens is based on their field of expertise, such as in human resources [59], strategy [60,61,62], operations management [63], or marketing [64,65]. In the operations management area, the research questions can be further categorized based on the focus, such as SMEs [34,66], supply chain [19,40,67,68], reverse logistics [69], Industry 4.0 [70,71], remanufacturing [65], etc.

Another criterion used to address the research question is linked to the geographic location where the study was based, such as in Thailand [72], India [65], Mexico [67], Scandinavian countries [73], the Netherlands [74], the United Kingdom [34], and other European countries [35]. There is also a generic lens where the focus is either on factors or on drivers, practices, challenges, etc., about CE adoption in supply chains or SMEs, such as in the studies by different scholars [19,34,66,75,76,77]. There are articles that are also focused on understanding the theories that are required to explain the phenomenon of CE adoption. Some of these articles are by [78,79]. Overall, we see that the research on CE adoption in supply chains or in SMEs is still very open-ended and the researchers are still exploring the phenomenon using different lenses.

4.3. Research Methodology and Theory That Are Used to Answer the Research Questions

4.3.1. Research Methodology

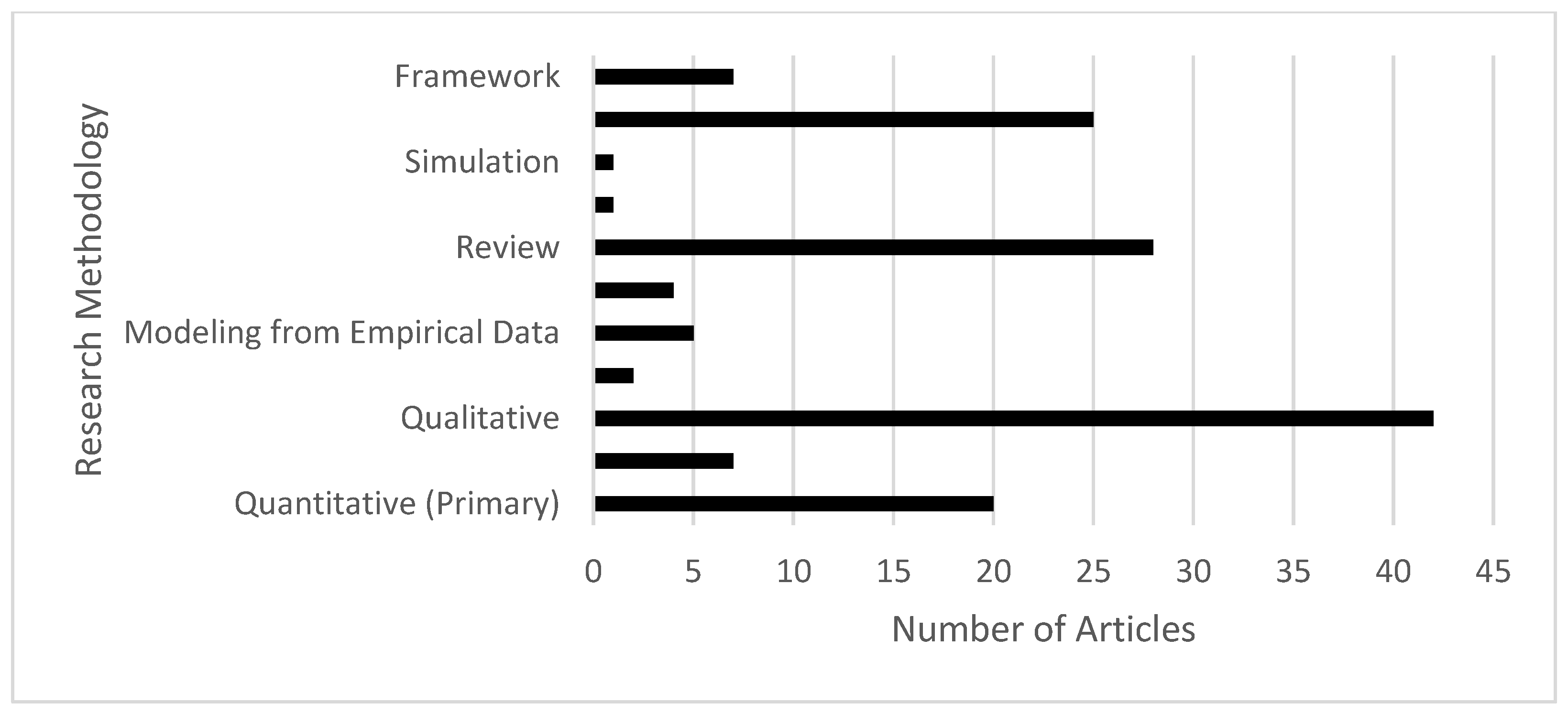

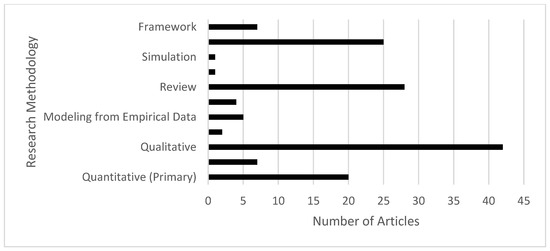

The research questions identified in the reviewed articles have been addressed using the methodologies depicted in Figure 5. It becomes clear that the dominant research methodology in the articles is qualitative studies or modeling without empirical evidence. According to [80], the choice of research strategy should consider three conditions: the type of research questions, the extent of control an investigator has over the actual behavior events, and the degree of focus on contemporary as opposed to historical events. This aligns with the observations from the previous section where we found most of the research questions are exploratory in nature and for both qualitative studies and mathematical models the investigators have control. Thus, based on the observations from the research methodology we can say that the theory of CE adoption in the SME context is at a nascent stage [58].

Figure 5.

Research methodology of the articles on CE implementation in supply chain/SMEs (Authors’ own conception).

4.3.2. Theory

Our survey of the articles shows that the CE adoption in supply chains and SMEs has seen the advent of theories in explaining the phenomena only in the last 4–5 years (see Table 3). Some of the major theories that are used include Agency theory, Institutional theory, Prospect theory, Stakeholder theory, and Systems theory. Given that SMEs are a vital component of the supply chain, the inclusion of these theories helps in explaining the interlocking mechanism between them and Overall Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) or Public Sector Units (PSUs). This is evident from the articles by [81,82,83,84,85], where they applied institutional and stakeholder theories. According to them, these theories substantiate the effect of both internal and external pressures, where these pressures help SMEs to change their practices in order to reduce negative impacts and increase positive ones in CE adoption. The application of systems theory by researchers such as [86,87], shows that the theory helps in explaining the consideration of the various interrelated elements that collectively affect the viability of CE adoption in SMEs.

Table 3.

Theories used in explaining CE adoption.

4.4. Enablers and Challenges

4.4.1. Enablers

In the last 5 years, there have been a few articles that highlight enablers, drivers, motivators, or success factors for CE implementation (refer to Table S3). For our research, we call them together enablers, but we are equally aware of the slight difference in meanings of these terminologies. Some of these enablers mentioned in the literature are very context-dependent, such as those from the fashion industry [73], feedstock industry [90], and also if the articles are discussing CE adoption in the whole supply chain or in a particular sector of SME or SMEs in general.

After going through the enablers of CE adoption in the reviewed articles, we classified the drivers for SMEs individually and then we came together and discussed the classification further. Once we all agreed on the categories, we individually started to list the drivers in those categories and, similar to the categories finalization, we came together again to finalize the list under each category of drivers for SMEs. The finalized list is provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Proposed enablers of CE adoption in SMEs.

Based on the review of enablers, we can see that there are a lot of enablers that can be considered for CE adoption in SMEs. We have gone beyond some of the existing classification systems in the literature, such as those by [19,91]. These classifications were from the supply chain perspective; so, there is a need for understanding the enablers from the SME context. Based on our prior research, we have found that employee well-being and adoption of new technologies are the enablers for SMEs if they are adequately supported by OEMs [34].

4.4.2. Challenges

The review of the articles showed us that there are around 29 articles that discuss the challenges in CE adoption or implementation in supply chains or SMEs.

The challenges have been classified by various researchers (see Table S4). Most of the classifications are around the environment, economy, technology, stakeholder, and market [19,32,34,92]. There are two classifications which are based on design [29] and specific product—printer cartridge [93]. Rajput and Singh [29], based on design orientation, classified challenges as interface design, technology upgradation, and synergy model; whereas [93] classified the challenges as related to the collection of the cartridges, issues in remanufacturing, and challenges at the organization level. Overall, the challenges still have common categories and, accordingly, we categorized them for the SMEs as shown in Table 5. One of the categories that we felt is not explored much in the supply chain and not at all in SMEs regards introducing workplace well-being and needs to be further studied.

Table 5.

Challenges for SMEs to overcome for CE adoption.

5. Meta-Analysis

Meta-analysis has been undertaken to answer research questions 1 and 2.

5.1. Research Trends, Questions, Methods, and Theories

In order to answer Research Question 1, we focused on understanding the trend of articles in CE research, including different types of research questions, research methods, and theories. The article publication trend shows a steady increase in the numbers. There was a sharp drop in article numbers in 2020, which might be attributed to COVID-19 when everything went to a standstill. However, the last three years have shown a steady increase in the number of articles about CE adoption in SMEs. This shows that there is increased interest in CE adoption in SMEs. This is evident from the types of research questions framed and also the theories applied in these research papers. The questions were primarily exploratory in nature and wanted to understand the enablers, barriers, practices, and strategies related to CE adoption in SMEs.

The patterns are also evident through the research methodologies applied. Our meta-analysis shows that qualitative research methods were primarily used in most of the articles and this aligns with the research question pattern [73].

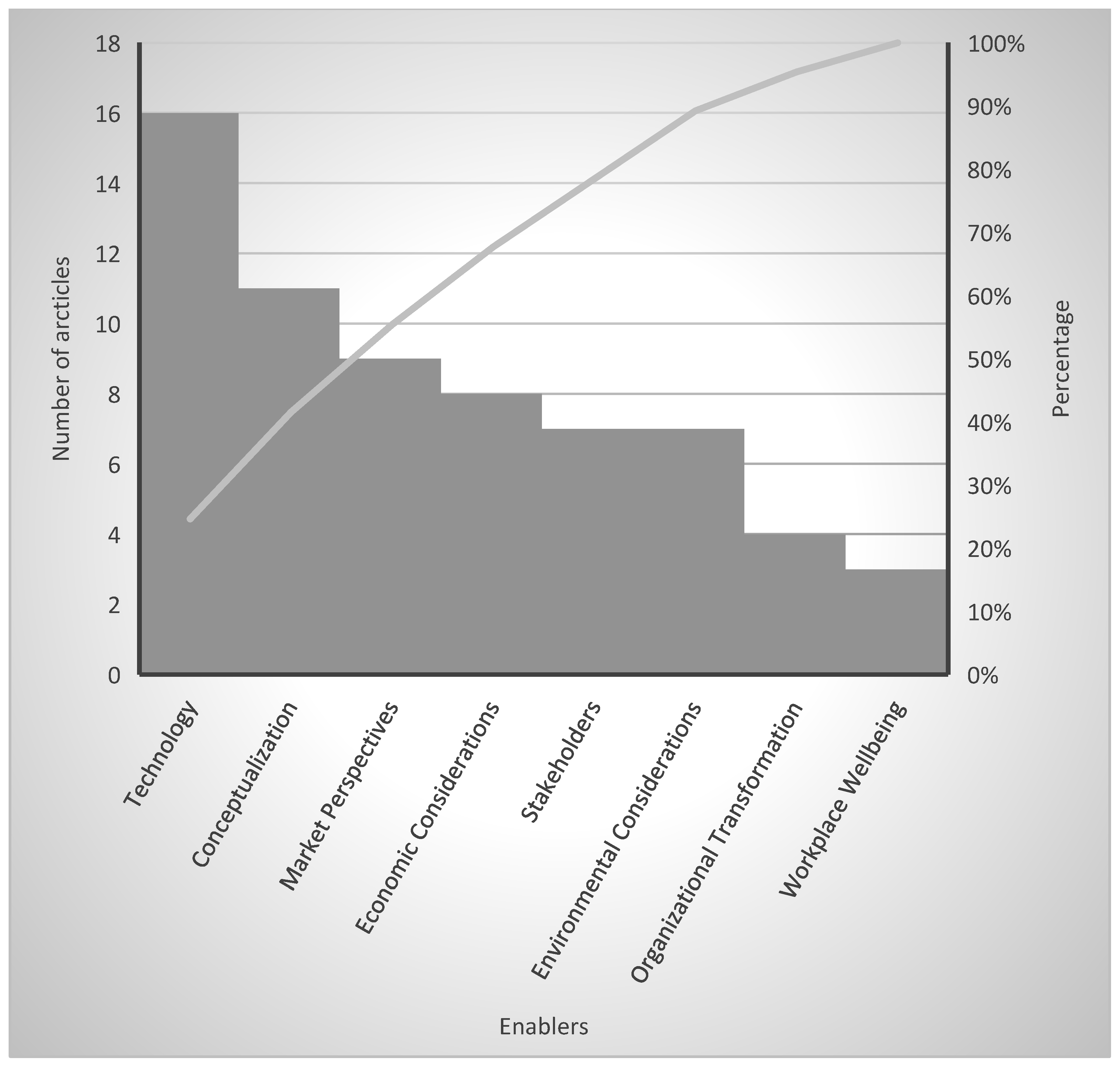

5.2. Enablers and Challenges

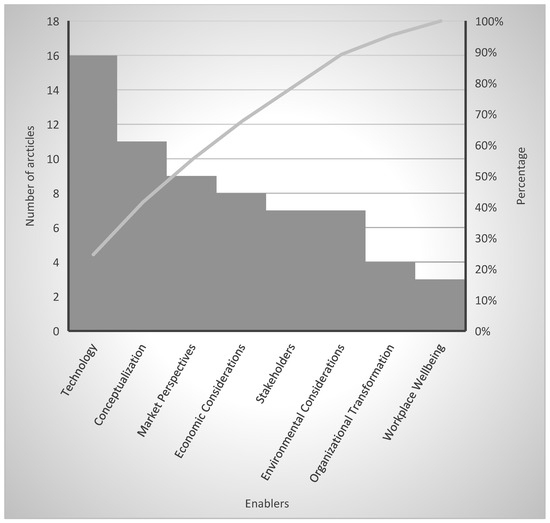

Figure 6 below shows that the first four categories almost cover 80 percent of the enablers for CE adoption. Advancement in technology is one of the major enabler categories, followed by conceptualization, market perspectives, and economic considerations. Surprisingly, stakeholder involvement is much lower in importance than the other factors. This is counterintuitive given the notion that top management commitment has always been a key success factor behind the successful adoption of any initiative. It can also be argued from the point of view of the difference between enabler and success factors. Top management commitment can definitely be a highly ranked success factor but enabling an adoption requires other considerations, such as marketing perspectives, economic considerations, etc.

Figure 6.

Pareto chart to identify enablers contributing to CE adoption (Authors’ own conception).

Technology is going to be a major enabler due to the emergence of Industry 4.0 in the manufacturing sector [29]. There is an emergence of other technologies, such as IoT, visual computing, and big data, which help not only companies but also customers to make more responsive and better decisions due to shorter feedback cycles [94]. SMEs in the supply chain of manufacturing industries will need adequate support from OEMs (Overall Equipment Manufacturers) to keep them abreast of technological advancements for successful CE adoption. Conceptualization is related to the design and development of processes and operations which aligns with different technological advancements and helps SMEs in developing products and services aligned with the benefits due to CE adoption. The literature suggests that the enablers in this category are mostly related to the development of supplier networks with low environmental impacts [28], proper inventory management system both for raw materials and remanufactured products [95], increased and efficient information sharing and better utilization of resources [84,95,96], and adequate know-how to improve existing processes according to the requirements of CE adoption [95].

Marketing perspectives are driven by two factors. One is the identification of markets for remanufactured, reused, and recycled products and services and the other is the consumer awareness about environment-friendly products and services creating pressure for CE adoption [19,56,96,97]. Finally, economic considerations revolve mostly around cost savings [87,98,99] but also include policies related to benefits received due to the design, development, and production of environment-friendly products and services through CE adoption [19,47,100]. The economic considerations, such as policy and regulation development towards incentivizing CE adoption, we feel will benefit SMEs and motivate them toward green solutions.

Low consideration of workplace wellbeing as an enabler is one category, which we feel needs to be looked at in-depth. As suggested by [95], it will be good to develop potential workplaces and improve vitality in order to motivate employees towards CE adoption. Further, SMEs can benefit greatly from investing in their employee health and wellbeing [73,86].

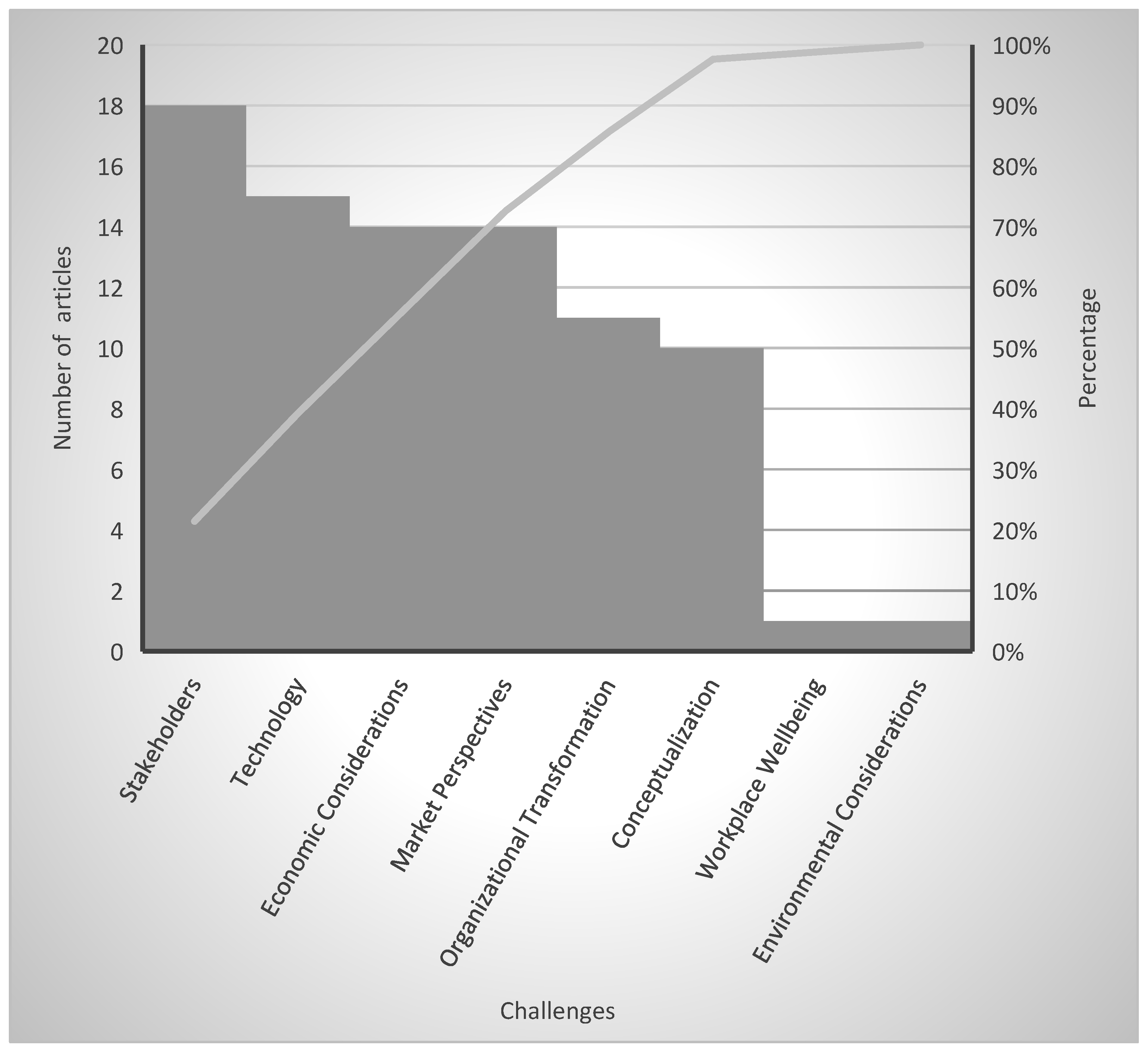

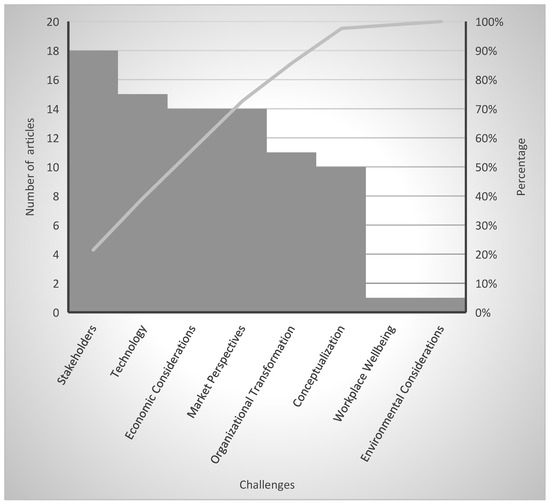

In an analysis similar to enablers, we found technology, economic considerations, and market perspectives as major challenges (refer to Figure 7) along with stakeholders towards CE adoption. Here, stakeholders are mostly external to the organization, such as the government and policymakers. A lack of government and legal standards, regulations, and policies towards incentivizing the organizations, in this case, SMEs, has been highlighted as a major roadblock towards CE adoption [19,34,95,101]. There is even a lack of definition regarding sustainability from an SME perspective [28]. Challenges on the technical front include bottlenecks related to the designing of reusable or recoverable products, a lack of knowledge related to intellectual property or patents for in-house innovative technology development [87], and a lack of technical skills and innovation capacity [2,40,97].

Figure 7.

Pareto chart to identify challenges hindering CE adoption (Authors’ own conception).

Economic challenges are related to both technological and stakeholder-related challenges. One of the costs is high investment or transition cost which will be due to developing green solutions or investing in R&D or newer technologies [63,91]. Another aspect that is related to cost considerations is adequate policies and procedures related to financial support and incentives, which makes it difficult for SMEs to think of CE adoption. This leads SMEs to believe that developing sustainable products and services is a cost rather than an investment [31,35,40,96]. Finally, though enablers suggest that there is pressure due to customer education about environment-friendly products and services, the literature on barriers and challenges suggests otherwise. According to several authors, there is a lack of social awareness and uncertainty about customers’ responsiveness and subsequent demand for recycled, reused, or remanufactured products [19,50,85]. There is also poor market confidence in refurbished or recycled products as there is a lack of technical standards related to such products and services. So, we feel that there are interlinkages between challenges and if they are addressed at the policy level then the challenges will be more internal than external to an organization. The literature focuses on both enablers and challenges and is still about government and legal policies and procedures; so, more understanding is required about CE adoption from an organizational change management perspective as well as about employee health and wellbeing. These factors are more important from the SME perspective.

We also explored the literature to understand the measures that will be useful for SMEs to understand the success of CE adoption. The literature mainly suggests cost savings as one of the metrics followed by a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. The cost savings will happen mainly due to reduced costs of production, disposal, inventory carrying, and transportation. Also, there will be more profitability due to customer satisfaction, better resource utilization, and lower cost of raw materials [30,82,91]. The literature is still limited in measuring the success of CE adoption and, thus, there is further research scope to work on developing appropriate metrics for SMEs.

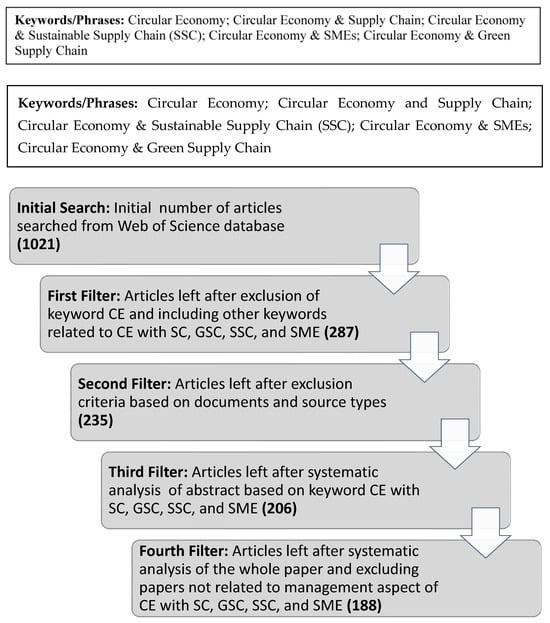

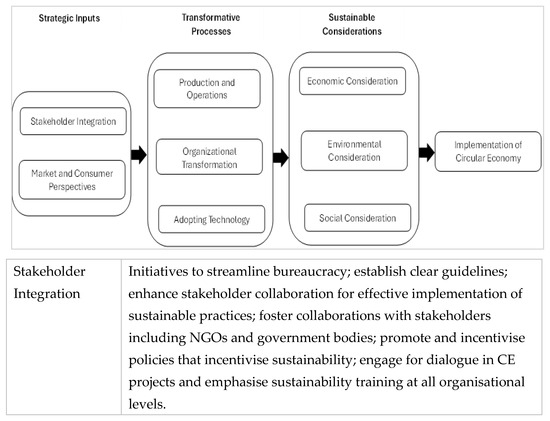

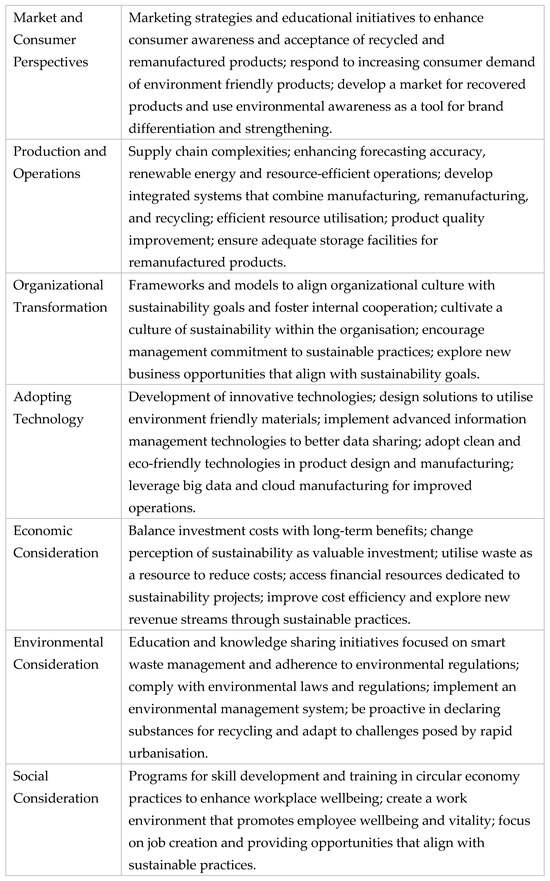

5.3. Strategies, Practices, and Framework for Circular Economy Adoption

The content analysis of 188 papers resulted in robust strategies, practices, and frameworks for CE adoption in SMEs. The whole underpinning is to embed CE philosophy within the organizational value chain (i.e., circular economy fields of action—design, procurement, production, distribution, consumption, and recovery) and supply chain drivers (facility, transportation, inventory, information, sourcing, and pricing). Practicing sustainability-oriented innovation and lean approach [35,75,86] across products, processes, facilities, and supply chains will enable the achievement of both energy and resource efficiency, well-being, waste management, and corporate social responsibility (CSR) following the reduce, reuse, and recycle principle. Both inter- and intra-organizational human resource management covering leadership, awareness and training, CSR, and governmental regulations are also key to adopting CE. Demand management encompassing understanding product attributes and customers’ requirements dynamically contributes to sustainability in CE adoption. Policy-makers’ regulations related to climate change issues also govern CE practices for effective adoption in a dynamic environment. Both conversion technology and communication technology play a major role in embedding sustainability practices across the CE fields of action and supply chain drivers. All these lead to enhanced sustainability (economic, environmental, and social) performance.

This robust framework will enable organizations and their supply chains to measure the current CE state and identify issues, challenges, and means for improvement. A cost–benefit analysis will be undertaken to develop a business model to make a decision on CE project implementation. An evaluation of the improvement project will be undertaken following the implementation of the improvement project.

6. Discussion

The advent of the CE in the last couple of decades has seen an increase in research interest related to sustainable products and services, sustainable development and sustainable consumption, economic and environmental sustainability assessments, technical advancements in products and processes, etc. Larger corporations are already investing the resources and time towards CE adoption but the same cannot be said about its adoption in SMEs. So, to understand this lacuna in the literature and check the state of the art we did a systematic literature review about CE adoption in SMEs. As SMEs are the vital cog of the supply chain, we focused on the articles on CE adoption not only in SMEs but also in the supply chain.

Three major research questions were the driving force behind this study. They are as follows: What are the drivers/enablers for CE implementation in SMEs? What are the challenges and barriers to CE implementation in SMEs? How can we measure CE implementation success for SMEs? We also focused on the basic demographics of the articles, but the major thrust was to understand the research questions, research designs, and the theories applied so far in the studies selected for our research. This helped us understand the theory stage of the research [51] on CE adoption in SMEs or supply chains. Table 6 below summarizes our answers to the research questions.

Table 6.

Summary of answers to research questions.

In answering Research Question 1, analysis of research questions and research design helped us to understand that the field is still exploratory in nature as most of the research methods are still qualitative. According to [51], we can suggest that the research on CE adoption in supply chains, as well as in SMEs, is at a nascent stage. This shows that there are a lot of opportunities to explore CE adoption; so, our review, at this stage, is timely. The theories applied in the studies so far include stakeholder theory, systems theory, agency theory, and institutional theory. Most of these theories focus on the arrangement of and relations between the parts that connect them into a whole. As our study focused on supply chains and SMEs, the application of these theories is understandable. However, the application of theories is still very limited. Going forward, there is a need to look beyond the existing theories that can explain CE adoption in SMEs as well as develop theories to help SMEs in CE adoption. In the literature, there is an immense discussion about SMEs being resource-poor and that they might not have the required capabilities to successfully adopt the CE [79,91]. In such scenarios, it will be worthwhile to study CE adoption strategically and look through theoretical lenses such as a resource-based view [52] or dynamic capability [61]. We started with several research questions initially but, for this study, we narrowed it down to three research questions and, through SLR and meta-analysis, tried to explore and answer the questions. We found that there is very limited research about CE adoption in SMEs and there is definitely a need to have an extensive study. SMEs are the growth engine for not only emerging but also developed economies; so, a thorough understanding and the development of a pathway for CE adoption in SMEs is a need of the hour.

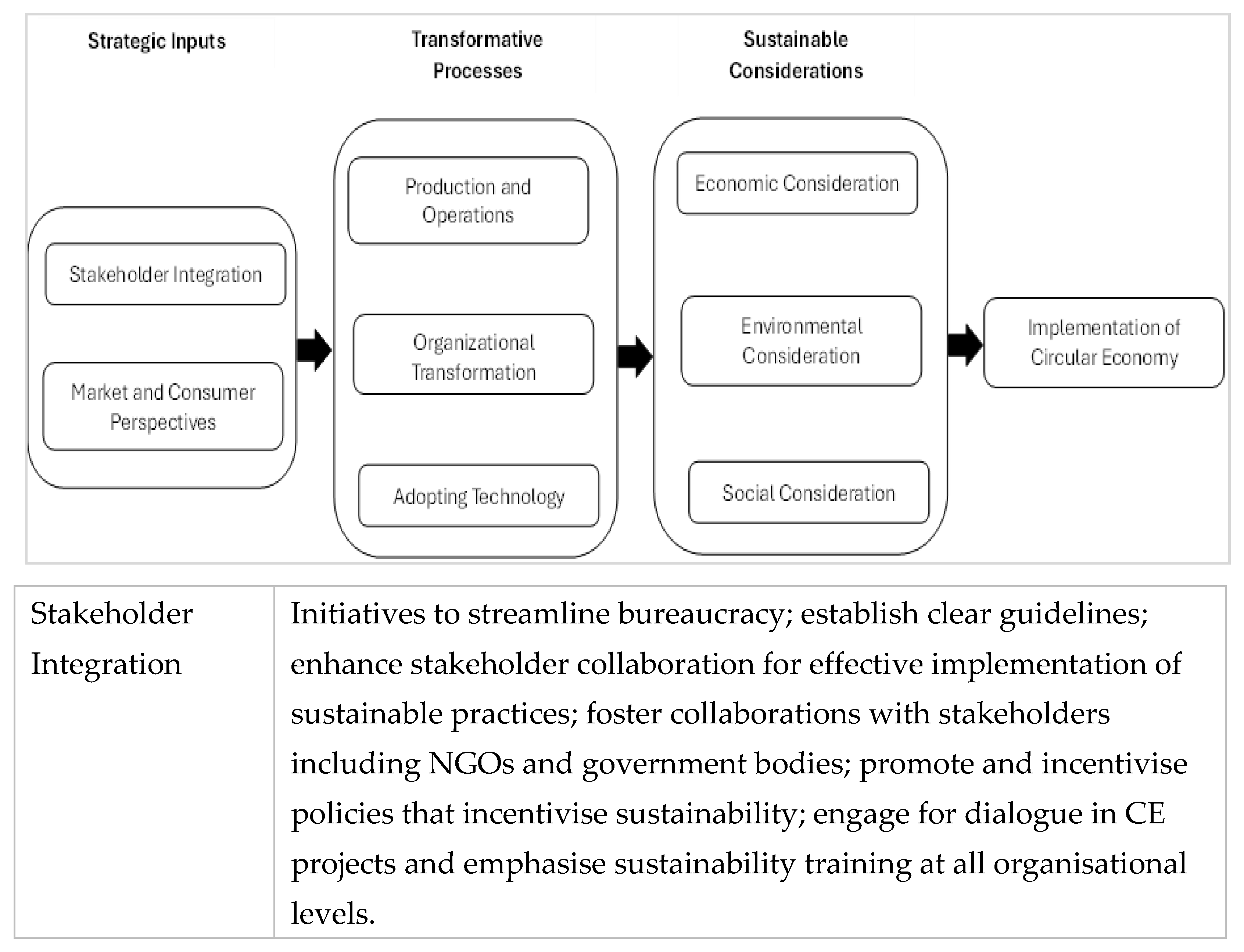

To answer Research Question 2, based on our analyses and findings, we developed a conceptual framework (refer to Figure 8), which includes enablers, challenges, and outcomes. In enablers and challenges, there are two broad categorizations. One is “Push” and the other “Pull”. These broad categorizations help us to understand CE adoption in a better manner. As per our framework, we feel that Technology, Stakeholders, and Organizations push SMEs towards CE adoption. Technology, due to ongoing advancements, will prompt SMEs to always look for new technologies not only to align with customer needs but also to develop sustainable products and services. Similarly, there is always a push from the stakeholders and organizational aspects to stay ahead of the competitors and align with the customers which prompts SMEs towards adoption of CE. On the Pull side, market, economy, and environment. The market aspect is driven by either customers or competition. These two factors both pull SMEs towards CE adoption as either there is a requirement from the customers or the competition prompts them to stay ahead, or, at least, stay abreast [25,42,89,90]. The economic considerations, such as policy and regulation development, toward incentivizing CE adoption and the development of supplier networks with a low environmental impact further pull SMEs toward CE adoption [19,28,70,79]. We feel that enablers will help in overcoming the challenges and, thus, CE adoption will lead to measurable outcomes or sustainable performance for SMEs.

Figure 8.

Framework for CE implementation in SMEs.

Finally, strategies for resource and energy efficiency are important to facilitate CE adoption in SMEs. Moving towards the CE will help increase resource efficiency by keeping the highest values of the materials as well as keeping different materials, components, and products in the economy as long as possible. This will help in reducing or eliminating not only the waste but also the extraction of virgin materials as inputs for production [35]. OECD [91] proposes processes related to closing, slowing, and narrowing resource loops (refer to Table 7) in order to achieve resource efficiency.

Table 7.

Resource loops (adapted from [91]).

Improvements in resource efficiency provide a complementary solution to the policies related to decarbonization through the addition of renewable energy sources or through energy efficiency [50,62,66,80,84,101]. Resource efficiency also provides a pathway to minimize primary energy use and waste and addresses issues related to resource scarcity [102].

Thus, through content analysis, meta-analysis, and a conceptual framework, we have tried to answer all the research questions. Figure 8 shows the framework that could be used to implement CE adoption in SMEs.

Research question 3 is used to suggest strategies for SMEs to promote the implementation of the CE in SMEs. The analysis provided in the findings section can be summarized as below:

- (a)

- Conceptualization, Design, Implementation, and Operations:

The drivers for the conceptualization, design, and operation in SMEs struggle with the integration of manufacturing processes, resource efficiency, and assessing the circular economy as their competitive advantage. SMEs also face challenges in navigating renewable energy markets, forecasting spare parts, and complexity in supply chains.

Hence, the strategies for CE adoption lie in the step-by-step approach. The SMEs first need to overcome supply chain complexities and enhance forecasting accuracy in the context of renewable energy and resource-efficient operations. They need to develop integrated systems that combine manufacturing, remanufacturing, and recycling. Also, there needs to be a focus on efficient resource utilization, product quality improvement, and ensuring adequate storage facilities for remanufactured products.

- (b)

- Stakeholders:

SMEs actively work in collaboration with stakeholders to understand policies and secure support for sustainability training. In this process, SMEs must navigate bureaucratic issues, the lack of clear sustainability guidelines, and the insufficient implementation of circular economy laws. Therefore, SMEs should initiate efforts to streamline bureaucratic processes, establish clear guidelines, and enhance stakeholder collaboration for the effective implementation of sustainability practices.

SMEs should strive to foster collaborations with stakeholders, including NGOs and government bodies, promote and support policies that incentivize sustainability, engage in dialogues about circular economy projects, and emphasize sustainability training at all organizational levels.

- (c)

- Adopting Newer Technology:

SMEs can access enhanced information sharing, gain access to clean technology, and use environmentally friendly materials.

However, SMEs face limited innovation capacity, technological limitations, and design challenges, along with limited financial resources. SMEs should develop innovative technologies and design solutions to overcome these limitations and effectively utilize environmentally friendly materials. They should aim to implement advanced information management technologies for better data sharing. Additionally, they should adopt clean and eco-friendly technologies in product design and manufacturing. SMEs should also leverage big data and cloud manufacturing for improved operations.

- (d)

- Organizational Transformation:

SMEs’ unique characteristics involve a commitment to sustainability, innovation, and leadership for sustainable commitment. SMEs have challenges across organizational reluctance, conflicts with existing culture, and a lack of effective business models. Hence, for organizational transformation, SMEs need to adopt frameworks and models to align organizational culture with sustainability goals and foster internal cooperation, cultivate a culture of sustainability within the organization, and encourage management commitment to sustainable practices. SMEs need to explore new business opportunities that align with sustainability goals.

- (e)

- Introducing Workplace Wellbeing:

For SMEs, there is workforce well-being if there is an increase in workplace vitality and job creation. However, there is a lack of employee skills in a circular economy.

SMEs need to have programs for skill development and training in circular economy practices to enhance workplace well-being, create a work environment that promotes employee well-being and vitality, and focus on job creation and providing opportunities that align with sustainable practices.

- (f)

- Economic Considerations:

SMEs are capable of cost savings and generating new revenue streams. However, SMEs face challenges of high investment costs, perception issues, and economic disincentives.

SMEs need strategies to balance investment costs with long-term benefits and to change perceptions of sustainability as a valuable investment. They tend to utilize waste as a resource to reduce costs. SMEs need to access financial resources dedicated to sustainability projects, improve cost efficiency, and explore new revenue streams through sustainable practices.

- (g)

- Market Perspectives:

SMEs have increased customer awareness and market potential for recovered products. However, SMEs face challenges of low consumer awareness, the need for new consumer behavior, and flawed perceptions.

The SME strategy would be marketing strategies and educational initiatives to enhance consumer awareness and acceptance of recycled and remanufactured products, respond to increasing consumer demand for environmentally friendly products, develop a market for recovered products, and use environmental awareness as a tool for brand differentiation and strengthening.

- (h)

- Environmental Considerations:

SMEs have compliance with environmental regulations, environmental management systems. However, they have slack of knowledge in smart waste management.

The SME strategy would be education and knowledge-sharing initiatives focused on smart waste management and adherence to environmental regulations, comply with environmental laws and regulations. Implement an environmental management system, be proactive in declaring substances for recycling, and adapt to the challenges posed by rapid urbanization.

7. Conclusions

In the last decade, a circular economy has become imperative because of the growing population and rapid urbanization. This has also necessitated that researchers focus on this phenomenon and explore possibilities of CE adoption in different contexts. There have been several review papers that have focused either on CE definitions, CE business models, or on the CE in the supply chain. There are also several reviews, as evident from our paper, about drivers, practices, and challenges of CE adoption, but there are no reviews about drivers, barriers, practices, etc., about CE adoption in SMEs, to the best of our knowledge. We have observed an increase in the number of articles focusing specifically on SMEs in the last two years. This is an encouraging sign showing the growing importance of SMEs in various economies. The focus of these articles is on enablers and barriers to CE adoption for SMEs. This helped us to understand the enablers and barriers of SMEs in a better manner.

7.1. Implications

Thus, based on the review of 188 articles on CE adoption in supply chains and SMEs, we identified the research methodologies used and theories applied to explain the CE adoption phenomenon, drivers, and challenges of CE adoption. We found that the literature mostly talks about these issues in terms of a lack of policy and regulations, government interventions, and technological advancements in CE adoption and categorization based on economy, environment, stakeholder, technology, and social perspectives. Many of these categorizations will be for CE adoption in SMEs but there is a real need to understand the drivers, barriers, etc., from the SME perspective. So, keeping this in view, we have classified the drivers and challenges for SMEs based on conceptualization, stakeholder perspective, technology adoption, organizational transformation, employee well-being, and economic, marketing, and environmental considerations. The key contribution of the review is the framework proposed. The framework can be used by practitioners for the implementation of the CE. The framework has been derived from a structured approach to understanding the subject matter. The key contributions of the review include synthesizing the existing literature, identifying gaps in knowledge, and proposing the framework for implementation.

7.2. Future Directions

Our study is primarily based on a systematic literature review following the PRISMA framework. The analyses carried out are primarily content and meta-analysis.

There are several other analyses that can be carried out further by researchers using bibliometric software, such as VOSviewer (version 1.6.20), Biblioshiny (version 4.1), etc. These tools will help in understanding the most cited works, including the most prolific authors contributing extensively to this field.

Further studies will be needed to empirically explore the drivers and challenges of CE adoption in SMEs as well as reorganize the categories. We feel our work provides the following:

- A landscape of research questions, theories, drivers, and challenges on CE adoption in SMEs in the last decade.

- This review helps both practitioners and researchers to develop a pathway for CE adoption and understand the whole gamut of drivers and challenges to manage successful CE adoption.

- The information synthesized from this research shows the power of systematic literature review through content analyses and visualize large volumes of content in a structured manner from peer-reviewed journals.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/systems13030200/s1, Tables S1–S4. S1: Summary of previous literature reviews on CE and sustainability; S2: Research questions of the study articles; S3: Enablers of CE adoption in the reviewed articles; S4: Challenges in CE adoption in the reviewed articles

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C. and P.K.D.; methodology, A.C. and D.D.; formal analysis, A.C. and D.D.; investigation, A.C. and D.D.; resources, A.C.; data curation, A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C. and D.D.; writing—review and editing, A.C., D.D. and P.K.D.; visualization, A.C. and D.D.; supervision, P.K.D.; project administration, A.C. and P.K.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CE | Circular Economy |

| SMEs | Small and Medium Enterprises |

| SLR | Systematic Literature Review |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis |

References

- Bonner, J. SMEs and Environmental/Social Impacts’ 2019. Available online: https://blogs.accaglobal.com/2012/09/27/smes-and-environmentalsocial-impacts/ (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Jaeger, B.; Upadhyay, A. Understanding barriers to circular economy: Cases from the manufacturing industry. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2020, 33, 729–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M.; De los Rios, C.; Rowe, Z.; Charnley, F. A conceptual framework for circular design. Sustainability 2016, 8, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulding, E.K. The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth. In Environmental Quality in a Growing Economy, Resources for the Future; Jarrett, H., Ed.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1966; pp. 3–14. Available online: https://e4a-net.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/the-economics-of-the-coming-spaceship-earth-historical-encyclopedia-of-earth.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Segerson, K.; Pearce, D.W.; Turner, R.K. Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment. Land Econ. 1991, 67, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, H.S.; Mosgaard, M.A. A review of micro level indicators for a circular economy—Moving away from the three dimensions of sustainability? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, J.Á.; Sossa, J.W.Z.; Mendoza, G.L.O. Barriers to sustainability for small and medium enterprises in the framework of sustainable development—Literature review. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.; Antony, J.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Cherrafi, A.; Lameijer, B. Integrated green lean approach and sustainability for SMEs: From literature review to a conceptual framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 118205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klewitz, J.; Hansen, E.G. Sustainability-oriented innovation of SMEs: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Gupta, K.; Rani, L.; Rawat, D. Drivers of Sustainability Practices and SMEs: A Systematic Literature Review. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 7, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolacci, F.; Caputo, A.; Soverchia, M. Sustainability and financial performance of small and medium sized enterprises: A bibliometric and systematic literature review. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 1297–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, M. Designing the business models for circular economy—Towards the conceptual framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferasso, M.; Beliaeva, T.; Kraus, S.; Clauss, T.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D. Circular economy business models: The state of research and avenues ahead. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 3006–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendzel-Skowera, K. Circular economy business models in the SME Sector. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarja, M.; Onkila, T.; Mäkelä, M. A systematic literature review of the transition to the circular economy in business organizations: Obstacles, catalysts and ambivalences. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 286, 125492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieder, M.; Rashid, A. Towards circular economy implementation: A comprehensive review in context of manufacturing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 115, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Hasanagic, M. A systematic review on drivers, barriers, and practices towards circular economy: A supply chain perspective. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 278–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnbet, M.M.; Skaar, C.; Fet, A.M.; Schulte, K.Ø. Circular economy in manufacturing companies: A review of case study literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 294, 126268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Z.; Sawang, S.; Kivits, R.A. Proposing circular economy ecosystem for Chinese SMEs: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukker, A. Product services for a resource-efficient and circular economy—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A Review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, F. Circular business models: Business approach as driver or obstructer of sustainability transitions? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 224, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Gupta, S.; Foropon, C. Examining the role of dynamic remanufacturing capability on supply chain resilience in circular economy. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 863–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Chen, H.; Hazen, B.T.; Kaur, S.; Gonzalez, E.D.S. Circular economy and big data analytics: A stakeholder perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 144, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, C.P.; González, P.D.R.; Carrillo-Hermosilla, J. Drivers and barriers of eco-innovation types for sustainable transitions: A quantitative perspective. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, M.; Longo, M.; Zanni, S. Circular economy in Italian SMEs: A multi-method study. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, S.; Singh, S.P. Connecting circular economy and industry 4.0. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, M.S.; Srivastava, R.K. Antecedents of implementation success in closed-loop supply chain: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 7344–7360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumpa, T.J.; Ali, S.M.; Rahman, H.; Paul, S.K.; Chowdhury, P.; Khan, S.A.R. Barriers to green supply chain management: An emerging economy context. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236, 117617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressanelli, G.; Perona, M.; Saccani, N. Challenges in supply chain redesign for the Circular Economy: A literature review and a multiple case study. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 7395–7422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.K.; Malesios, C.; De, D.; Chowdhury, S.; Ben Abdelaziz, F. Could lean practices and process innovation enhance supply chain sustainability of small and medium-sized enterprises? Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 582–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.K.; Malesios, C.; De, D.; Budhwar, P.; Chowdhury, S.; Cheffi, W. Circular economy to enhance sustainability of small and medium-sized enterprises. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 2145–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooque, M.; Zhang, A.; Thürer, M.; Qu, T.; Huisingh, D. Circular supply chain management: A definition and structured literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 882–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahane, S.; Kant, R.; Shankar, R. Circular supply chain management: A state-of-art review and future opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizos, V.; Behrens, A.; Van Der Gaast, W.; Hofman, E.; Ioannou, A.; Kafyeke, T.; Flamos, A.; Rinaldi, R.; Papadelis, S.; Hirschnitz-Garbers, M.; et al. Implementation of circular economy business models by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): Barriers and Enablers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormazabal, M.; Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Puga-Leal, R.; Jaca, C. Circular economy in Spanish SMEs: Challenges and opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, D.; Veijonaho, S.; Toppinen, A. Towards sustainability? Forest-based circular bioeconomy business models in Finnish SMEs. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 110, 101848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, U.; Sroufe, R. Sustainability in the circular economy: Insights and dynamics of designing circular business models. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Dhamija, P.; Bryde, D.J.; Singh, R.K. Effect of eco-innovation on green supply chain management, circular economy capability, and performance of small and medium enterprises. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Espíndola, O.; Cuevas-Romo, A.; Chowdhury, S.; Díaz-Acevedo, N.; Albores, P.; Despoudi, S.; Dey, P. The role of circular economy principles and sustainable-oriented innovation to enhance social, economic and environmental performance: Evidence from Mexican SMEs. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 248, 108495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.K.; Malesios, C.; Chowdhury, S.; Saha, K.; Budhwar, P.; De, D. Adoption of circular economy practices in small and medium-sized enterprises: Evidence from Europe. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 248, 108496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negri, M.; Neri, A.; Cagno, E.; Monfardini, G. Circular economy performance measurement in manufacturing firms: A systematic literature review with insights for small and medium enterprises and new adopters. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangarso, A.; Sisilia, K.; Peranginangin, Y. Circular economy business models in the micro, small, and medium enterprises: A review. Etikonomi 2022, 21, 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuik, S.; Kumar, A.; Diong, L.; Ban, J. A Systematic literature review on the transition to circular business models for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Sustainability 2023, 15, 9352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Bachrach, D.G.; Podsakoff, N.P. The influence of management journals in the 1980s and 1990s. Strat. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furrer, O.; Thomas, H.; Goussevskaia, A. The structure and evolution of the strategic management field: A content analysis of 26 years of strategic management research. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2008, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashishth, A.; Chakraborty, A.; Antony, J. Lean Six Sigma in financial services industry: A systematic review and agenda for future research. Total. Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2017, 30, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedharan, V.R.; Pattusamy, M.; Mohan, S.; Persis, D.J. A systematic literature review of lean six sigma in financial services: Key finding and analysis. Int. J. Bus. Excel. 2020, 21, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, V.; Antony, J.; Linderman, K. A Multilevel Framework of Six Sigma: A Systematic Review of the Literature, Possible Extensions, and Future Research. Qual. Manag. J. 2014, 21, 36–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A.C.; Mcmanus, S.E. Methodological fit in management field research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 1155–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Sarkis, J.; Jabbour, A.B.L.d.S.; Renwick, D.W.S.; Singh, S.K.; Grebinevych, O.; Kruglianskas, I.; Filho, M.G. Who is in charge? A review and a research agenda on the ‘human side’ of the circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolakis, N.; Bam, W.; Srai, J.S.; Kumar, M. Renewable chemical feedstock supply network design: The case of terpenes. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 802–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, E.; Urbinati, A.; Chiaroni, D. Managerial practices for designing circular economy business models: The case of an Italian SME in the office supply industry. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2019, 30, 561–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, L.; Jia, F.; Xu, Z. Complementarity of circular economy practices: An empirical analysis of Chinese manufacturers. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 6369–6384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.; Rojas Luiz, J.V.; Rojas Luiz, O.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Ndubisi, N.O.; Caldeira de Oliveira, J.H.; Junior, F.H. Circular economy business models and operations management. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 1525–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, I.; Confente, I.; Scarpi, D.; Hazen, B.T. From trash to treasure: The impact of consumer perception of bio-waste products in closed-loop supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 218, 966–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, D.; Tripathy, S.; Jena, S.K. Acceptance of remanufactured products in the circular economy: An empirical study in India. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 953–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veleva, V.; Bodkin, G. Corporate-entrepreneur collaborations to advance a circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 188, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Liu, S.; Zhang, T.; Choi, T.-M. Optimal advertising and pricing for new green products in the circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 233, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, C.V.; Bond, A.; Vaz, C.R.; Bertolo, R.J. Reverse flows within the pharmaceutical supply chain: A classificatory review from the perspective of end-of-use and end-of-life medicines. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 238, 117719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalverkamp, M.; Young, S.B. In support of open-loop supply chains: Expanding the scope of environmental sustainability in reverse supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, C.; Singh, A. A review of Industry 4.0 in supply chain management studies. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2019, 31, 863–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, D.L.M.; Alencastro, V.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Caiado, R.G.G.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Rocha-Lona, L.; Tortorella, G. Exploring Industry 4.0 technologies to enable circular economy practices in a manufacturing context: A business model proposa. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2019, 30, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandvik, I.M.; Stubbs, W. Circular fashion supply chain through textile-to-textile recycling. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 23, 366–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leising, E.; Quist, J.; Bocken, N. Circular Economy in the building sector: Three cases and a collaboration tool. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 976–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homrich, A.S.; Galvão, G.; Abadia, L.G.; Carvalho, M.M. The circular economy umbrella: Trends and gaps on integrating pathways. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.A. Circular economy at the micro level: A dynamic view of incumbents’ struggles and challenges in the textile industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 833–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Godinho Filho, M.; Roubaud, D. Industry 4.0 and the circular economy: A proposed research agenda and original roadmap for sustainable operations. Ann. Oper. Res. 2018, 270, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Feng, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J. Green supply chain management and the circular economy: Reviewing theory for advancement of both fields. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2018, 48, 794–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Identifying Your Case(s) and Establishing the Logic of Your Case Study. Appl. Soc. Res. Methods Ser. 2013, 34, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meherishi, L.; Narayana, S.A.; Ranjani, K. Sustainable packaging for supply chain management in the circular economy: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 117582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Childe, S.J.; Papadopoulos, T.; Helo, P. Supplier relationship management for circular economy: Influence of external pressures and top management commitment. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 767–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.; Pascucci, S. Institutional incentives in circular economy transition: The case of material use in the Dutch textile industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 155, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, V.; Bloemhof-Ruwaard, J.; Borsato, M. Towards Regenerative Supply Networks: A design framework proposal. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 221, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolakis, N.; Srai, J.S. Mapping supply dynamics in renewable feedstock enabled industries: A systems theory perspective on ‘green’ pharmaceuticals. Oper. Manag. Res. 2018, 11, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, H.K.; Stewart, R.A.; Sahin, O.; Dudley, M. Drivers, barriers and enablers to end-of-life management of solar photovoltaic and battery energy storage systems: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhu, Q. Barriers of a closed-loop cartridge remanufacturing supply chain for urban waste recovery governance in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 1544–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettel, M.; Fischer, F.G.; Bendig, D.; Weber, A.R.; Wolff, B. Enablers for Self-optimizing Production Systems in the Context of Industrie 4.0. Procedia CIRP 2016, 41, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posada, J.; Toro, C.; Barandiaran, I.; Oyarzun, D.; Stricker, D.; de Amicis, R.; Pinto, E.B.; Eisert, P.; Dollner, J.; Vallarino, I. Visual Computing as a Key Enabling Technology for Industrie 4.0 and Industrial Internet. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 2015, 35, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.; McMahon, E.; Samtani, S.; Patton, M.; Chen, H. Identifying vulnerabilities of consumer Internet of Things (IoT) devices: A scalable approach. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Intelligence and Security Informatics: Security and Big Data, ISI, Beijing, China, 22–24 July 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tura, N.; Hanski, J.; Ahola, T.; Ståhle, M.; Piiparinen, S.; Valkokari, P. Unlocking circular business: A framework of barriers and drivers. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, S.B.; Masi, D.; Feibert, D.C.; Jacobsen, P. How the reverse supply chain impacts the firm’s financial performance: A manufacturer’s perspective. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2018, 48, 284–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, M.H.A.; Genovese, A.; Acquaye, A.A.; Koh, S.C.L.; Yamoah, F. Comparing linear and circular supply chains: A case study from the construction industry. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 183, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rawashdeh, S.; Nasaj, M.; Ahmad, S.Z. Driving circular economy adoption through top management commitment and organisational motivation: A quantitative study on small- and medium-sized enterprises. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2024, 32, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.K.; Panda, A.; Arghode, V. Tourism’s circular economy: Opportunities and challenges from an integrated theoretical perspective. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2024, 33, 6172–6186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, M.; Powell, S. Health and well-being in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). What public health support do SMEs really need? Perspect. Public Health 2014, 135, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Towards a More Resource-Efficient and Circular Economy: The Role of the G20; OECD: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, H.; van Beukering, P.; Brouwer, R. Business models and sustainable plastic management: A systematic review of the literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piyathanavong, V.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Kumar, V.; Maldonado-Guzmán, G.; Mangla, S.K. The adoption of operational environmental sustainability approaches in the Thai manufacturing sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 507–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, A.; Dellink, R.; Bibas, R. The Macroeconomics of the Circular Economy Transition: A Critical Review of Modelling Approaches; OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 30; OECD: Paris, France, 2018; Available online: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/sites/default/files/knowledge_-_oecd_ce_transition.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Paes, L.A.B.; Bezerra, B.S.; Deus, R.M.; Jugend, D.; Battistelle, R.A.G. Organic solid waste management in a circular economy perspective—A systematic review and SWOT analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 239, 118086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalhammar, C. Industry attitudes towards ecodesign standards for improved resource efficiency. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 123, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Venkatesh, V.; Liu, Y.; Wan, M.; Qu, T.; Huisingh, D. Barriers to smart waste management for a circular economy in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 118198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingley, D.D.; Cooper, S.; Cullen, J. Understanding and overcoming the barriers to structural steel reuse, a UK perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 148, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Xu, Q.; Wu, P. Omnichannel retail operations with refurbished consumer returns. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, A.R.M.; Genovese, A.; Brint, A.; Kumar, N. Improving reverse supply chain performance: The role of supply chain leadership and governance mechanisms. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 216, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P.; Wilson, P.; Walsh, C.; Hodgson, P. The role of material efficiency to reduce CO2 emissions during ship manufacture: A life cycle approach. Mar. Policy 2017, 75, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Gold, S.; Bocken, N.M.P. A Review and Typology of Circular Economy Business Model Patterns. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 36–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).