Dominant Factors for an Effective Selection System: An Australian Education Sector Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review of Theoretical Framework and Empirical Study Background

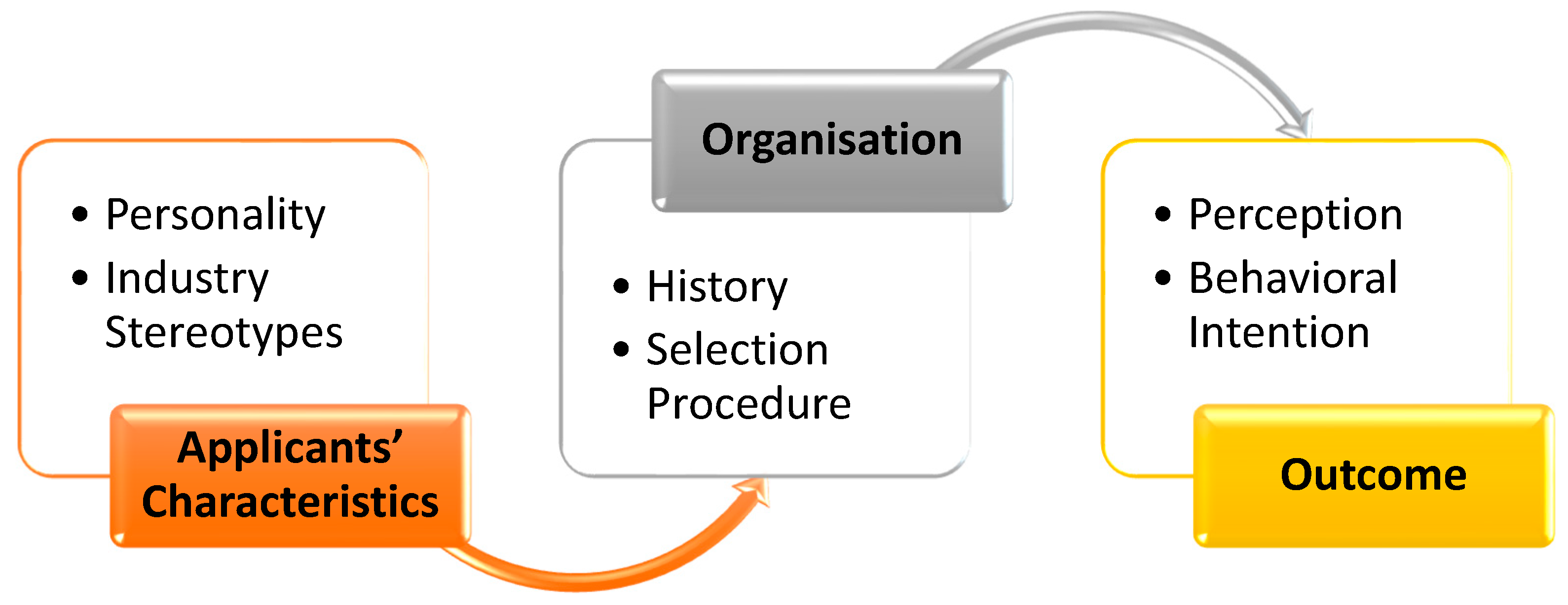

2.1. A Review of the Theoretical Framework

2.2. Empirical Study Background

3. Empirical Study Design

4. Analysis of Dominant Factors to Consider for Improvements to the Interview Selection Process

4.1. Quantitative Analysis: Exploratory Factor Analysis

4.2. Qualitative Analysis—Thematic Analysis

- Training the hiring members for the interview process;

- Planning and preparing for the interview process;

- Removing the bias of the hiring members during the interview process;

- Providing feedback to applicants to ensure a transparent process; and

- Ensuring the hiring decisions are process-driven instead of driven by the interviewer’s personality.

“At [withheld], we use [withheld] on our website, and people can see our positions. So, they apply for our position online, and then our interview process is managed through that recruitment module through the back end. We know which people are shortlisted. We can see where people are at through the stages. That way we can see if they are unsuccessful quite early or we can see if they progress through to the interview stage, etc.”

- Transparent outcome;

- Updating services;

- Improved process;

- Understating the requirements better;

- Data stored as a database and managed online with objective rating systems;

- Better position to provide relevant feedback and to defend the decision taken; and

- Finally making the organization appear professional.

5. Summary of Findings and Discussion

- Ensuring the integrity of the interview selection process;

- Enhancing the applicant feedback process with enriched information; and

- Contributory elements towards the overall satisfaction of the interview selection process.

- Ongoing training should reinforce that discriminatory questions cannot be asked;

- Include an HR/neutral representative on the committee; and

- Rather than necessarily providing feedback, perhaps the HR role should be to obtain feedback on the process from unsuccessful applicants for each position.

6. Conclusions and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| # | SPSS Label | N | Mean | Survey Question |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Total Duration (HM) | 138 | 3 | As a hiring member—The duration of the total hiring process we follow is reasonable |

| 2 | Interview Bias (HM) | 138 | 6 | As a hiring member—There was a bias of some sort in the hiring decision (gender, race, religion, etc.) |

| 3 | Qualified Interviewer (HM) | 138 | 3 | As a hiring member—Every interviewer selected is qualified to be part of the hiring team |

| 4 | Interview Planning and Prep (HM) | 138 | 3 | As a hiring member—Sufficient time is set aside for planning and preparing the hiring process |

| 5 | Prompt Final Decision (HM) | 138 | 3 | As a hiring member—Interviewers are prompt with providing their final hiring decision |

| 6 | Interviewer Questions Provided (HM) | 138 | 2 | As a hiring member—Interviewers are provided with a set of questions for structured interviews |

| 7 | Prefer Unstructured Interviewers (HM) | 138 | 5 | As a hiring member—Interviewers prefer unstructured interviews |

| 8 | Interviewer Temperament (HM) | 138 | 5 | As a hiring member—Interviewers’ temperament affected the hiring decision |

| 9 | Process Taken Seriously (HM) | 138 | 2 | As a hiring member—Interviewers take the hiring process seriously |

| 10 | Process Needs Improvements (HM) | 138 | 3 | As a hiring member—The existing hiring process we follow requires improvements |

| 11 | Overall Good Process (HM) | 138 | 3 | As a hiring member—Overall, I feel we have a good hiring process set for this organisation |

| 12 | Reasonable Total Duration (HS) | 350 | 2 | As a successful applicant—The duration of the total hiring process was reasonable |

| 13 | Appropriate Methods (HS) | 350 | 2 | As a successful applicant—The interview method used was appropriate (phone/face-to-face/panel, etc.) |

| 14 | Bias on Religion (HS) | 350 | 6 | As a successful applicant—There was bias in the hiring decision based on religion |

| 15 | Bias on Gender (HS) | 350 | 6 | As a successful applicant—There was bias in the hiring decision based on gender |

| 16 | Bias on Ethnicity (HS) | 350 | 6 | As a successful applicant—There was bias in the hiring decision based on ethnicity |

| 17 | No Bias (HS) | 350 | 3 | As a successful applicant—There was no bias of any sort in the hiring decision |

| 18 | Temperament Impacted (HS) | 350 | 5 | As a successful applicant—The interviewer’s temperament impacted on the hiring decisions |

| 19 | Relevant Questions (HS) | 350 | 2 | As a successful applicant—All interview questions were relevant to the job |

| 20 | Organised Process (HS) | 350 | 2 | As a successful applicant—The interview process was well organised |

| 21 | Prepared Interviewers (HS) | 350 | 2 | As a successful applicant—The interviewers were well prepared for the interview |

| 22 | Interview Length (HS) | 350 | 2 | As a successful applicant—The length of the interviews was reasonable |

| 23 | Equal Panel Participation (HS) | 350 | 2 | As a successful applicant—All interviewers in the panel participated equally in the interview |

| 24 | Qualified Interviewer (HS) | 350 | 2 | As a successful applicant—I felt the interviewers had the necessary qualifications to interview |

| 25 | Internal Employee Preference (HS) | 350 | 4 | As a successful applicant—I feel that internal employees are preferred to external applicants for interviews |

| 26 | Provided Feedback (HS) | 350 | 4 | As a successful applicant—Constructive interview feedback was provided after the interview |

| 27 | Process Improvements Required (HS) | 350 | 4 | As a successful applicant—The hiring process requires many improvements |

| 28 | Regard Based on Process (HS) | 350 | 3 | As a successful applicant—I have high regard for this organisation based on its hiring process |

| 29 | Overall satisfaction (HS) | 350 | 3 | As a successful applicant—Overall, I was satisfied with the entire hiring process |

| 30 | Scoring System (HP) | 203 | 2 | In general, an interview scoring sheet can be used to assist in hiring decisions |

| 31 | Panel Structure (HP) | 203 | 4 | In general, one-to-one interviews are better than panel interviews |

| 32 | Multiple Interviews (HP) | 203 | 5 | In general, multiple one-to-one interviews can replace a panel interview |

| 33 | Applicant Suggestions (HP) | 203 | 3 | In general, HR can collect feedback/suggestions on interview experience from applicants |

| 34 | Interview Feedback (HP) | 203 | 2 | In general, constructive interview performance feedback should be provided |

| 35 | Objective Consistent System (HP) | 203 | 3 | In general, we promote an objective and standard model for hiring process across all TAFE |

| 36 | Transparency (HP) | 203 | 3 | In general, the hiring process needs to have more transparency in the hiring decision |

| 37 | HR Representative (HP) | 203 | 3 | In general, we always have an HR representative during interviews to ensure standard/consistency |

| 38 | Successful Applicant Summary (HP) | 200 | 4 | In general, we share a summary of a successful candidate with other interview applicants |

| Communalities | ||

|---|---|---|

| Initial | Extraction | |

| HS_Total_hiring_process | 0.535 | 0.438 |

| HS_Appropriate_Int_Method | 0.690 | 0.740 |

| HS_Religion_Bias | 0.598 | 0.517 |

| HS_Gender_Bias | 0.848 | 0.926 |

| HS_Ethnicity_Bias | 0.818 | 0.799 |

| HS_No_Bias | 0.430 | 0.305 |

| HS_Intrwr_Temp_Impact | 0.616 | 0.633 |

| HS_Relvnt_IntQ | 0.610 | 0.601 |

| HS_Int_Process_Organised | 0.788 | 0.761 |

| HS_Prepared_Intrwr | 0.809 | 0.766 |

| HS_Int_length_Reasonale | 0.710 | 0.765 |

| HS_Equal_Panel_Particp | 0.663 | 0.591 |

| HS_Intwr_Quals_Suffcnt | 0.756 | 0.801 |

| HS_InternalEmp_Prf_ExtEmp | 0.455 | 0.430 |

| HS_IntFdbk_Provided | 0.504 | 0.424 |

| HS_Hir_Process_Imprv_Req | 0.683 | 0.705 |

| HS_HighReg_HiringProcess | 0.729 | 0.817 |

| HS_Overall_Satisfied | 0.713 | 0.778 |

| HP_Use_Interview_Scoring | 0.428 | 0.354 |

| HP_ReplacePanel_1to1 | 0.511 | 0.644 |

| HP_Multiple_1to1 | 0.545 | 0.570 |

| HP_HR_collect_suggestions | 0.342 | 0.286 |

| HP_Constructive_interview_feedback | 0.421 | 0.423 |

| HP_Objective_standard_model | 0.316 | 0.310 |

| HP_More_transparency | 0.466 | 0.468 |

| HP_HR_representative_Int | 0.311 | 0.269 |

| HP_summary_successful_candidate | 0.391 | 0.312 |

| HM_Resonable_Total_Dur | 0.592 | 0.697 |

| HM_Bias_Present | 0.522 | 0.468 |

| HM_Qualfd_Intwr | 0.566 | 0.550 |

| HM_Sufficient_PlanPrep | 0.547 | 0.479 |

| HM_Prompt_FinalDesn | 0.540 | 0.445 |

| HM_Intrwr_ProvidedwithQuestion | 0.556 | 0.590 |

| HM_Intrwr_Prfer_UnstructuredInt | 0.531 | 0.457 |

| HM_Intvwrs_Temprmt_ImpactedDecsn | 0.601 | 0.704 |

| HM_Intwrs_take_Hpserious | 0.452 | 0.451 |

| HM_HP_requires_Imp | 0.616 | 0.564 |

| HM_Overall_HP_goodinOrg | 0.751 | 0.714 |

| Total Variance Explained | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Initial Eigenvalues | Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings | Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings | ||||||

| Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | |

| 1 | 9.781 | 25.740 | 25.740 | 9.435 | 24.829 | 24.829 | 3.910 | 10.288 | 10.288 |

| 2 | 2.919 | 7.680 | 33.420 | 2.580 | 6.788 | 31.617 | 2.990 | 7.869 | 18.157 |

| 3 | 2.527 | 6.650 | 40.070 | 2.027 | 5.334 | 36.951 | 2.800 | 7.369 | 25.526 |

| 4 | 1.949 | 5.128 | 45.198 | 1.450 | 3.816 | 40.767 | 2.075 | 5.459 | 30.986 |

| 5 | 1.810 | 4.763 | 49.961 | 1.433 | 3.772 | 44.539 | 1.740 | 4.580 | 35.565 |

| 6 | 1.448 | 3.810 | 53.772 | 1.055 | 2.776 | 47.315 | 1.729 | 4.550 | 40.115 |

| 7 | 1.353 | 3.559 | 57.331 | 0.914 | 2.405 | 49.720 | 1.615 | 4.249 | 44.365 |

| 8 | 1.245 | 3.276 | 60.607 | 0.783 | 2.061 | 51.781 | 1.612 | 4.243 | 48.608 |

| 9 | 1.150 | 3.025 | 63.632 | 0.691 | 1.818 | 53.599 | 1.238 | 3.258 | 51.866 |

| 10 | 1.097 | 2.887 | 66.519 | 0.648 | 1.705 | 55.304 | 0.933 | 2.455 | 54.321 |

| 11 | 1.021 | 2.686 | 69.205 | 0.535 | 1.409 | 56.713 | 0.909 | 2.392 | 56.713 |

| 12 | 0.937 | 2.467 | 71.672 | ||||||

| 13 | 0.916 | 2.410 | 74.082 | ||||||

| 14 | 0.808 | 2.126 | 76.208 | ||||||

| 15 | 0.775 | 2.039 | 78.247 | ||||||

| 16 | 0.721 | 1.896 | 80.143 | ||||||

| 17 | 0.686 | 1.806 | 81.949 | ||||||

| 18 | 0.632 | 1.664 | 83.614 | ||||||

| 19 | 0.618 | 1.627 | 85.241 | ||||||

| 20 | 0.579 | 1.525 | 86.766 | ||||||

| 21 | 0.546 | 1.438 | 88.203 | ||||||

| 22 | 0.485 | 1.276 | 89.479 | ||||||

| 23 | 0.453 | 1.192 | 90.672 | ||||||

| 24 | 0.421 | 1.107 | 91.778 | ||||||

| 25 | 0.377 | 0.991 | 92.769 | ||||||

| 26 | 0.353 | 0.929 | 93.698 | ||||||

| 27 | 0.313 | 0.824 | 94.522 | ||||||

| 28 | 0.289 | 0.759 | 95.281 | ||||||

| 29 | 0.273 | 0.718 | 95.999 | ||||||

| 30 | 0.260 | 0.684 | 96.683 | ||||||

| 31 | 0.231 | 0.607 | 97.290 | ||||||

| 32 | 0.202 | 0.531 | 97.821 | ||||||

| 33 | 0.182 | 0.479 | 98.300 | ||||||

| 34 | 0.162 | 0.426 | 98.726 | ||||||

| 35 | 0.154 | 0.405 | 99.131 | ||||||

| 36 | 0.136 | 0.359 | 99.490 | ||||||

| 37 | 0.115 | 0.303 | 99.794 | ||||||

| 38 | 0.078 | 0.206 | 100.000 | ||||||

| Component | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| HS_Int_length_Reasonale | 0.824 | ||||||||||

| HS_Relvnt_IntQ | 0.787 | ||||||||||

| HS_Int_Process_Organised | 0.715 | ||||||||||

| HS_Prepared_Intrwr | 0.691 | ||||||||||

| HS_Equal_Panel_Particp | 0.687 | ||||||||||

| HS_Appropriate_Int_Method | 0.680 | ||||||||||

| HS_Intwr_Quals_Suffcnt | 0.542 | 0.400 | |||||||||

| HM_Intrwr_ProvidedwithQuestion | 0.783 | ||||||||||

| HM_Sufficient_PlanPrep | 0.699 | ||||||||||

| HM_Qualfd_Intwr | 0.689 | ||||||||||

| HM_Overall_HP_goodinOrg | 0.585 | 0.464 | |||||||||

| HM_Resonable_Total_Dur | 0.551 | ||||||||||

| HM_Prompt_FinalDesn | 0.514 | ||||||||||

| HS_HighReg_HiringProcess | 0.723 | ||||||||||

| HS_Hir_Process_Imprv_Req | −0.717 | ||||||||||

| HM_HP_requires_Imp | −0.602 | ||||||||||

| HM_Bias_Present | −0.530 | ||||||||||

| HS_Gender_Bias | 0.861 | ||||||||||

| HS_Religion_Bias | 0.831 | ||||||||||

| HS_Ethnicity_Bias | 0.828 | ||||||||||

| HM_Intvwrs_Temprmt_ImpactedDecsn | 0.760 | ||||||||||

| HM_Intrwr_Prfer_UnstructuredInt | 0.653 | ||||||||||

| HS_Intrwr_Temp_Impact | 0.527 | −0.403 | |||||||||

| HP_ReplacePanel_1to1 | 0.805 | ||||||||||

| HP_Multiple_1to1 | 0.759 | ||||||||||

| HP_HR_representative_Int | 0.699 | ||||||||||

| HP_Objective_standard_model | 0.606 | ||||||||||

| HP_More_transparency | 0.576 | ||||||||||

| HP_Constructive_interview_feedback | 0.521 | ||||||||||

| HP_summary_successful_candidate | |||||||||||

| HS_IntFdbk_Provided | 0.684 | ||||||||||

| HS_Overall_Satisfied | 0.468 | 0.555 | |||||||||

| HP_Use_Interview_Scoring | 0.687 | ||||||||||

| HS_Total_hiring_process | −0.519 | ||||||||||

| HP_HR_collect_suggestions | −0.417 | 0.441 | |||||||||

| HS_No_Bias | −0.756 | ||||||||||

| HS_InternalEmp_Prf_ExtEmp | 0.730 | ||||||||||

| HM_Intwrs_take_Hpserious | 0.535 | ||||||||||

Appendix B

| # | Codes | Categories | Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Constructive Feedback | Applicant Feedback | Enhancing applicant feedback process with enriched information |

| 2 | Feedback Utility | Applicant Feedback | Enhancing applicant feedback process with enriched information |

| 3 | Organisational Change Impacts | External Association to the Interview Process | Ensuring integrity of the interview selection process |

| 4 | Feeling of Being Unsuccessful | External Association to the Interview Process | Enhancing applicant feedback process with enriched information |

| 5 | Feeling of Being Successful | External Association to the Interview Process | Enhancing applicant feedback process with enriched information |

| 6 | Interviewers Seriousness of the Process | Hiring Members Involvement | Contributory elements towards the overall satisfaction of the interview selection process |

| 7 | Participation of Panel Members | Hiring Members Involvement | Contributory elements towards the overall satisfaction of the interview selection process |

| 8 | Applicant Database Like Seek | Interview Process Enhancements | Contributory elements towards the overall satisfaction of the interview selection process |

| 9 | Best Interview: Elements | Interview Process Enhancements | Contributory elements towards the overall satisfaction of the interview selection process |

| 10 | Northern Territory state’s Feedback Process Replication in Victoria state | Interview Process Enhancements | Contributory elements towards the overall satisfaction of the interview selection process |

| 11 | Practical Improvements to HP | Interview Process Enhancements | Contributory elements towards the overall satisfaction of the interview selection process |

| 12 | Request for Feedback | Interview Process Enhancements | Contributory elements towards the overall satisfaction of the interview selection process |

| 13 | Share Interview Questions Prior Interview | Interview Process Enhancements | Contributory elements towards overall satisfaction of the interview selection process |

| 14 | Use of Technology: Recruitment Management System | Interview Process Enhancements | Contributory elements towards the overall satisfaction of the interview selection process |

| 15 | Common Selection Process for all TAFEs | Interview Process Enhancements | Contributory elements towards the overall satisfaction of the interview selection process |

| 16 | Use of Scores and Ranks | Interview Process Enhancements | Contributory elements towards the overall satisfaction of the interview selection process |

| 17 | Shortlisting Strategies for Interview | Interview Process Enhancements | overall satisfaction of the interview selection process |

| 18 | Shortlisting Strategies After Interview | Interview Process Enhancements | Contributory elements towards the overall satisfaction of the interview selection process |

| 19 | Appropriate Interview Method | Interview Process Problems | Ensuring integrity of the interview selection process |

| 20 | Duration of Interview | Interview Process Problems | Ensuring integrity of the interview selection process |

| 21 | Interview Planning and Prep Process | Interview Process Problems | Ensuring integrity of the interview selection process |

| 22 | Interview Outcome Conveyed Duration | Interview Process Problems | Ensuring integrity of the interview selection process |

| 23 | Interview Training | Interview Process Problems | Ensuring integrity of the interview selection process |

| 24 | Interviewer Qualified | Interview Process Problems | Ensuring integrity of the interview selection process |

| 25 | Organised Interview Process | Interview Process Problems | Ensuring integrity of the interview selection process |

| 26 | Relevant Interview Questions | Interview Process Problems | Ensuring integrity of the interview selection process |

| 27 | Cert IV implemented | Interview Process Problems | Ensuring integrity of the interview selection process |

| 28 | Key Selection Criteria - Enhancement | Interview Process Problems | Ensuring integrity of the interview selection process |

| 29 | Worst Interview: Elements | Interview Process Problems | Ensuring integrity of the interview selection process |

| 30 | Interviewer Preference Between Structured and Unstructured Interviews | Interview Process Problems | Ensuring integrity of the interview selection process |

| 31 | Training on How to Use the Scoring and Ranking | Interview Process Problems | Ensuring integrity of the interview selection process |

| 32 | Hiring Decision Overridden | Variation of Bias in Interviews | Ensuring integrity of the interview selection process |

| 33 | Internal Employees Preferred | Variation of Bias in Interviews | Ensuring integrity of the interview selection process |

| 34 | Interviewer Bias | Variation of Bias in Interviews | Ensuring integrity of the interview selection process |

| 35 | Underpin Fairness, Equality, and Transparency | Variation of Bias in Interviews | Ensuring integrity of the interview selection process |

References

- Ekwoaba, J.O.; Ikeije, U.U.; Ufoma, N. The impact of recruitment and selection criteria on organizational performance. Glob. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 3, 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Huffcutt, A.I.; Culbertson, S.S. APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 2: Selecting and Developing Members for the Organization; Zedeck, S., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 185–203. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt, D.; Jamieson, R. Improving Recruitment and Selection Decision Processes with an Expert System. In Proceedings of the Second Americas Conference on Information Systems, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 16–18 August 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sudheshna, B.; Sudhir, B. Employee Perception and Interview Process in IT Companies. Splint Int. J. Prof. 2016, 3, 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ababneh, K.I.; Al-Waqfi, M.A. The role of privacy invasion and fairness in understanding job applicant reactions to potentially inappropriate/discriminatory interview questions. Pers. Rev. 2016, 45, 392–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi Mehrabad, M.; Brojeny, M.F. The development of an expert system for effective selection and appointment of the jobs applicants in human resource management. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2007, 53, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ones, D.S.; Viswesvaran, C. Integrity tests and other criterion-focused occupational personality scales (COPS) used in personnel selection. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2001, 9, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierlasinski, N.J.; Nixon, D.R. A Comparison of Interviewing Techniques: HR versus Fraud Examination. Oxf. J. Int. J. Bus. Econ. 2014, 5, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, I.T.; Smith, M. Personnel selection. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2001, 74, 441–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, D.; Puharić, M.; Kastratović, E. Defining of necessary number of employees in airline by using artificial intelligence tools. Int. Rev. 2018, 3–4, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naim, I.; Tanveer, M.I.; Gildea, D.; Hoque, M.E. Automated analysis and prediction of job interview performance. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2016, 9, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosla, R.; Chu, M.-T.; Yamada, K.G.; Kuneida, K.; Oga, S. Innovative embodiment of job interview in emotionally aware communication robot. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, San Jose, CA, USA, 31 July–5 August 2011; pp. 1546–1552. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, W.C.; Chen, F.H.; Chen, H.-Y.; Tseng, K.-Y. When Will Interviewers Be Willing to Use High-structured Job Interviews? The role of personality. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2016, 24, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levashina, J.; Hartwell, C.; Morgeson, F.; Campion, M.A. The structured employment interview: Narrative and quantitative review of the research literature. Pers. Psychol. 2014, 67, 241–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffcutt, A.I.; Arthur, W., Jr. Hunter and Hunter (1984) revisited: Interview validity for entry-level jobs. J. Appl. Psychol. 1994, 79, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, J.; Dawes, R.; Peterson, N. Belief in the unstructured interview: The persistence of an illusion. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2013, 8, 512. [Google Scholar]

- Law, P.K.; Yuen, D.C. An empirical examination of hiring decisions of experienced auditors in public accounting: Evidence from Hong Kong. Manag. Audit. J. 2011, 26, 760–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozario, S.D.; Venkatraman, S.; Abbas, A. Challenges in Recruitment and Selection Process: An Empirical Study. Challenges 2019, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peccei, R.; Van de Voorde, K. The application of the multilevel paradigm in human resource management–outcomes research: Taking stock and going forward. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 786–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.A.; Pohler, D.M. Making stronger causal inferences: Accounting for selection bias in associations between high performance work systems, leadership, and employee and customer satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Messersmith, J. On the shoulders of giants: A meta-review of strategic human resource management. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 6–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, C.; den Hartog, D.N.; Lepak, D.P. A systematic review of human resource management systems and their measurement. J. Manag. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackett, P.R.; Lievens, F. Personnel selection. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 419–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ployhart, R.; Harold, C. The Applicant Attribution-Reaction Theory (AART): An Integrative Theory of Applicant Attributional Processing. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2004, 12, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederman, N.G.; Lederman, J.S. What Is a Theoretical Framework? A Practical Answer. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2015, 26, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M. Research Methods for Business Students, 6th ed.; Lewis, P., Thornhill, A., Eds.; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, E.; Bryman, A.; Harley, B. Business Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M. Research Methods for Business Students, 7th ed.; Lewis, P., Thornhill, A., Eds.; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- DeCoster, J. Overview of Factor Analysis. 1998. Available online: www.stat-help.com/notes.html (accessed on 23 May 2019).

- Williams, B.; Onsman, A.; Brown, T. Exploratory factor analysis: A five-step guide for novices. Australas. J. Paramed. 2010, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, J.M.; Huffcutt, A.I. A review and evaluation of exploratory factor analysis practices in organizational research. Organ. Res. Methods 2003, 6, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro-Premuzic, T. Psychology of Personnel Selection; Furnham, A., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley-Adams, K. Face to face with success: Keith Bradley-Adams offers advice on how to behave in interviews and how to answer tricky questions. (Career Development) (Brief article). Nurs. Stand. 2011, 25, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Entwistle, F. How to prepare for your first job interview. Nurs. Times 2013, 109, 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Emett, S.; Wood, D.A. Tactics: Common questions-evasion: Identify ploys and learn methods to get the specific answers you need. J. Account. 2010, 210, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Macan, T. The employment interview: A review of current studies and directions for future research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2009, 19, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.D.; Gordon, M.E. Meeting the Challenge of Human Resource Management: A Communication Perspective; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, M.; Cripps, B. Psychological Assessment in the Workplace; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: West Sussex, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

| Background | Related Theory | Introduced By | Synopsis of the Theory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personality | Cognitive-Affective System Theory | Walter Mischel and Yuichi Shoda | Personality tendencies may be stable in a specific context but may vary significantly on other domains due to the psychological cues and demands unique to one context. |

| Work performance | Trait Activation Theory | Robert Tett and Dawn Burnett | Trait activation theory states that employees will be looking for and derive fundamental satisfaction from a work environment that consents for the easy expression of their unique personality traits. |

| Job interview | Interpersonal Deception Theory | David B. Buller and Judee K. Burgoon | Describes how people handle actual/perceived deception knowingly or unknowingly while involved in face-to-face communication. |

| Signalling Theory | Michael Spence | One party (agent) credibly conveys some information about itself to another party (principal). | |

| The Theory of Planned Behaviour | Icek Ajzen | Explaining human behaviour by including perceived behavioural control. Connecting behaviour with beliefs to improve the predictive power of the theory of reasoned action. | |

| Theory of Reasoned Action | Martin Fishbein and Icek Ajzen | It is used in predicting how a person would behave based on their pre-existing approaches and behavioural intents. | |

| Social Cognitive Theory | Albert Bandura | Remembering the consequences and sequence of others experience and using this information to guide their own subsequent behaviours even when they have not experienced it beforehand. | |

| Retention | Expectancy-Value Theory | Lynd-Stevenson | There must be a balanced relationship between the candidate’s expectations and the value the company can deliver. |

| # | Urban Institutes (Melbourne) | # | Regional Institutes | Regional Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Box Hill Institute | 1 | Federation Training | Chadstone |

| 2 | Chisholm | 2 | Federation University | Ballarat |

| 3 | Holmesglen | 3 | Gordon Institute of TAFE | Geelong |

| 4 | Kangan Institute | 4 | South West TAFE | Warrnambool |

| 5 | Melbourne Polytechnic | 5 | Wodonga TAFE | Wodonga |

| 6 | William Angliss Institute | 6 | Sunraysia Institute | Mildura |

| 7 | AMES Australia | 7 | GOTAFE | Wangaratta |

| 8 | RMIT University | |||

| 9 | Swinburne | |||

| 10 | Victoria Polytechnic |

| TAFE/Dual-Sector | Interviews | Successful Interview Experience | Unsuccessful Interview Experience | Hiring Member |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Name Coded) | Qualitative Data (N) | Quantitative Data (N) | ||

| 1 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | 6 | 22 | 2 | 7 |

| 3 | 8 | 22 | 5 | 13 |

| 4 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 3 |

| 5 | 4 | 45 | 4 | 28 |

| 6 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 7 |

| 7 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 4 |

| 8 | 5 | 14 | 4 | 5 |

| 9 | 5 | 21 | 5 | 6 |

| 10 | 7 | 59 | 14 | 28 |

| 11 | 6 | 16 | 8 | 8 |

| 12 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 5 |

| 13 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| 14 | 6 | 19 | 2 | 6 |

| 15 | 5 | 24 | 5 | 5 |

| 16 | 5 | 18 | 4 | 12 |

| 17 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 5 |

| Other | 0 | 52 | 27 | 0 |

| Total | 74 | 368 | 91 | 146 |

| Gender | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 104 | 51% |

| Female | 98 | 48% |

| Do not wish to answer | 2 | 1% |

| Age | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 25–34 | 15 | 7% |

| 35–44 | 32 | 16% |

| 45–54 | 64 | 31% |

| 55–64 | 79 | 39% |

| 65–74 | 14 | 7% |

| Citizenship | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Australian Citizen | 184 | 90% |

| Permanent Resident | 16 | 8% |

| Other | 4 | 2% |

| Research Question | Quantitative Analysis—Online Survey Questions | Qualitative Analysis—Interview Questions |

|---|---|---|

| What are the dominant factors to be considered for improving the effectiveness of the current hiring process? | • The duration of the total hiring process was reasonable • There was bias in the hiring decision • All interview questions were relevant to the job • The interview process was well organised • Constructive interview feedback was provided | • What more information would you have liked when the hiring decision was conveyed to you? • Can you describe the best interview you have had as an interviewee? Why is it the best? • Can you describe the best interview you have had as an interviewer? • How do you think we can underpin fairness, equity, and transparency in the hiring process? |

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | 0.807 | |

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approximate chi-square | 2486.455 |

| df | 703 | |

| Significance | 0.000 | |

| Valid Cases | Reliability Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | Cronbach’s Alpha | N Items | |

| Case Processing Summary 1 | 350 | 95.1 | 0.903 * | 7 |

| Case Processing Summary 2 | 138 | 37.5 | 0.815 * | 6 |

| Case Processing Summary 3 | 135 | 36.7 | −0.696 | 5 |

| Case Processing Summary 4 | 350 | 95.1 | 0.905 * | 3 |

| Case Processing Summary 5 | 135 | 36.7 | 0.714 * | 3 |

| Case Processing Summary 6 | 203 | 55.2 | 0.784 * | 2 |

| Case Processing Summary 7 | 203 | 55.2 | 0.584 | 4 |

| Case Processing Summary 8 | 203 | 55.2 | 0.117 | 5 |

| Case Processing Summary 9 | 203 | 55.2 | 0.089 | 3 |

| Case Processing Summary 10 | 135 | 36.7 | 0.021 | 2 |

| Case Processing Summary 11 | 135 | 36.7 | 0.021 | 2 |

| # | EFA Components Label |

|---|---|

| 1 | Training |

| 2 | Planning and structured interviews |

| 3 | Bias in the selection process |

| 4 | Interviewer’s personality |

| 5 | Panel Interview and Transparency |

| # | Thematic Analysis (Categories) |

|---|---|

| 1 | Hiring members involvement |

| 2 | Interview process enhancements |

| 3 | Variation of bias in interviews |

| 4 | Interview process problems |

| 5 | Applicant feedback |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rozario, S.D.; Venkatraman, S.; Chu, M.-T.; Abbas, A. Dominant Factors for an Effective Selection System: An Australian Education Sector Perspective. Systems 2019, 7, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems7040050

Rozario SD, Venkatraman S, Chu M-T, Abbas A. Dominant Factors for an Effective Selection System: An Australian Education Sector Perspective. Systems. 2019; 7(4):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems7040050

Chicago/Turabian StyleRozario, Sophia Diana, Sitalakshmi Venkatraman, Mei-Tai Chu, and Adil Abbas. 2019. "Dominant Factors for an Effective Selection System: An Australian Education Sector Perspective" Systems 7, no. 4: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems7040050

APA StyleRozario, S. D., Venkatraman, S., Chu, M.-T., & Abbas, A. (2019). Dominant Factors for an Effective Selection System: An Australian Education Sector Perspective. Systems, 7(4), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems7040050