An Updated Etiology of Hair Loss and the New Cosmeceutical Paradigm in Therapy: Clearing ‘the Big Eight Strikes’

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Reversible Autoimmune: Alopecia Areata

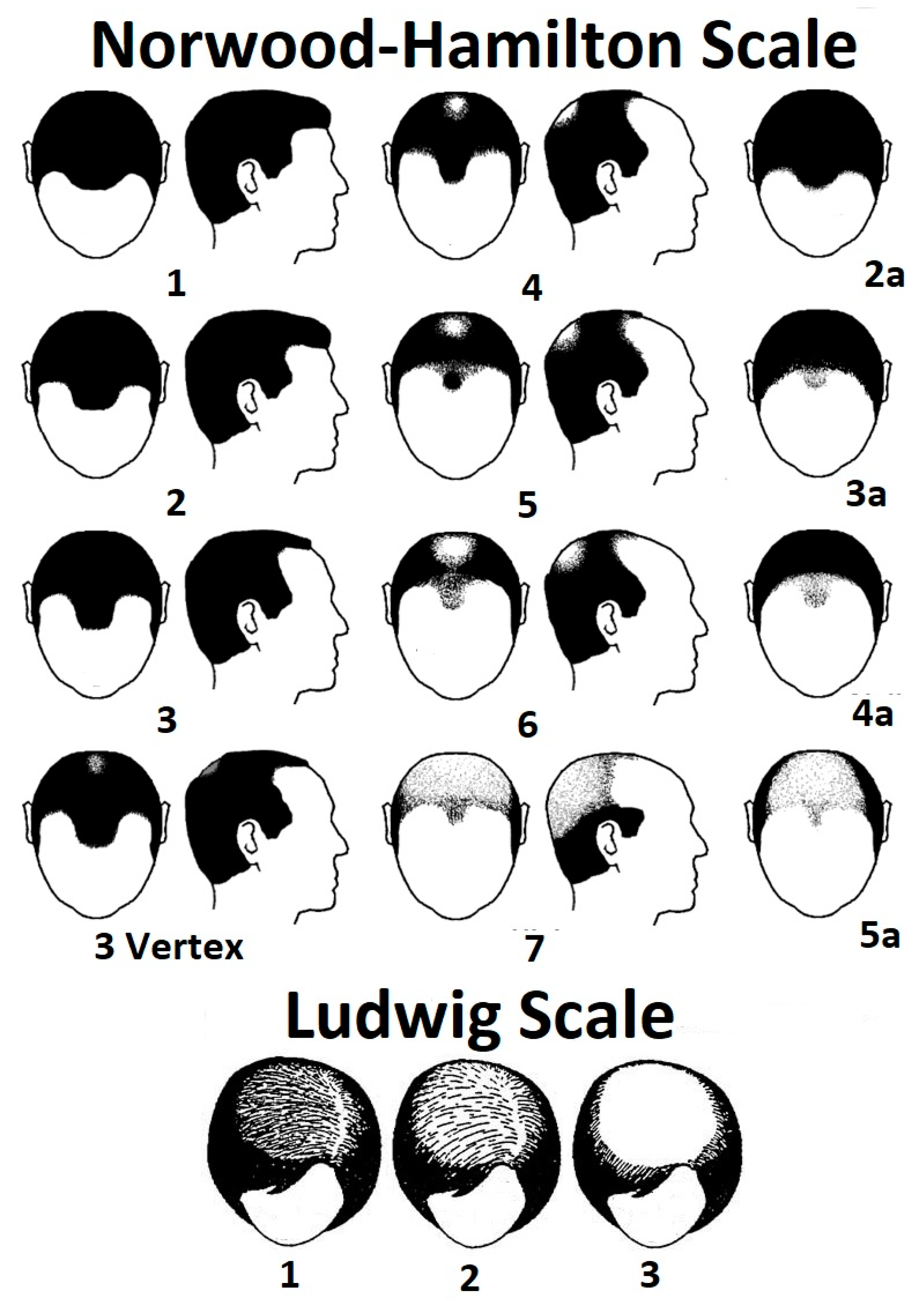

1.2. Androgenetic: Androgenetic Alopecia (AGA: Pattern Hair Loss)

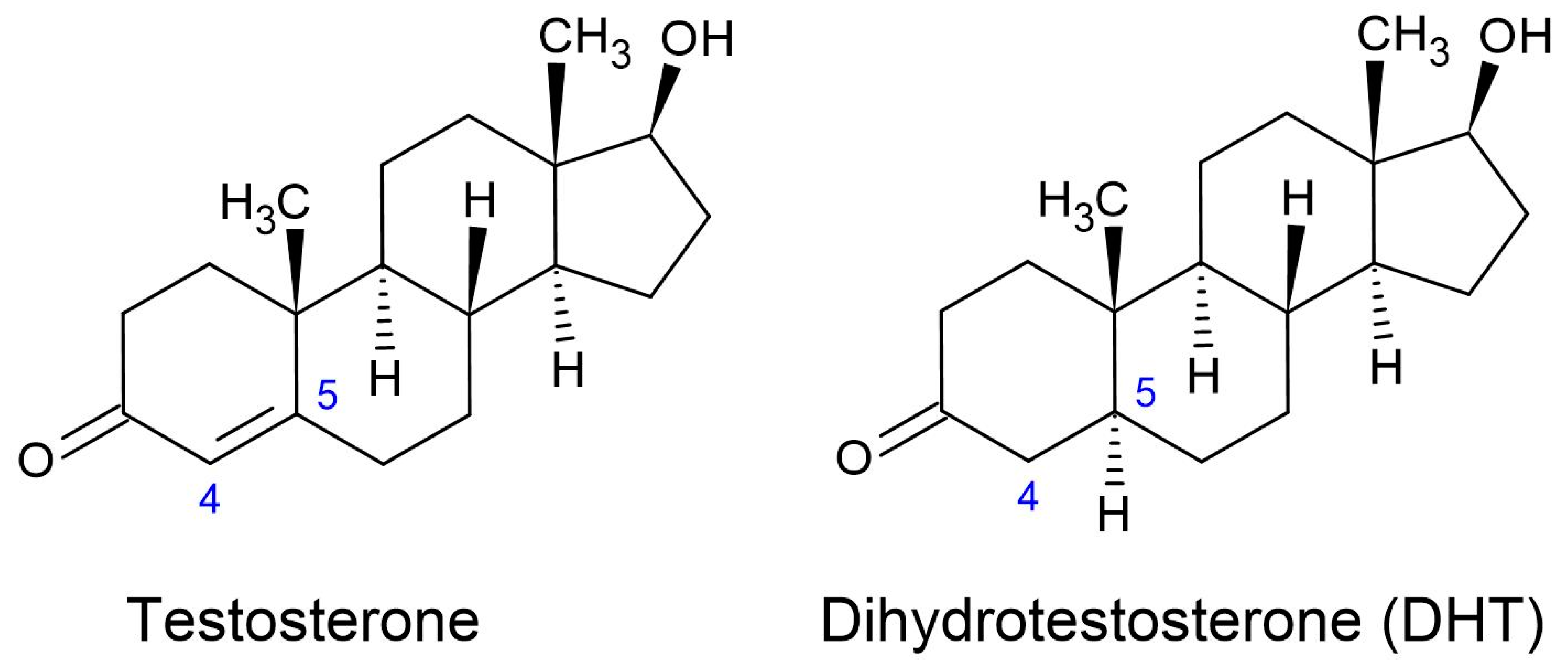

1.2.1. Dihydrotestosterone (DHT)

1.2.2. Molecular Mechanisms of DHT

1.2.3. Finasteride as a 5α-Reductase Inhibitor

1.2.4. Beyond DHT

1.3. Scarring: Cicatricial/Fibrosing Alopecia

1.4. Fungal/Bacterial Alopecia: Follicular Decalvans and Tinea Capitis

1.5. Stress/Trauma (Chemical, Psychological, and Physical)

2. The Big Eight Strikes, in Simple Terms

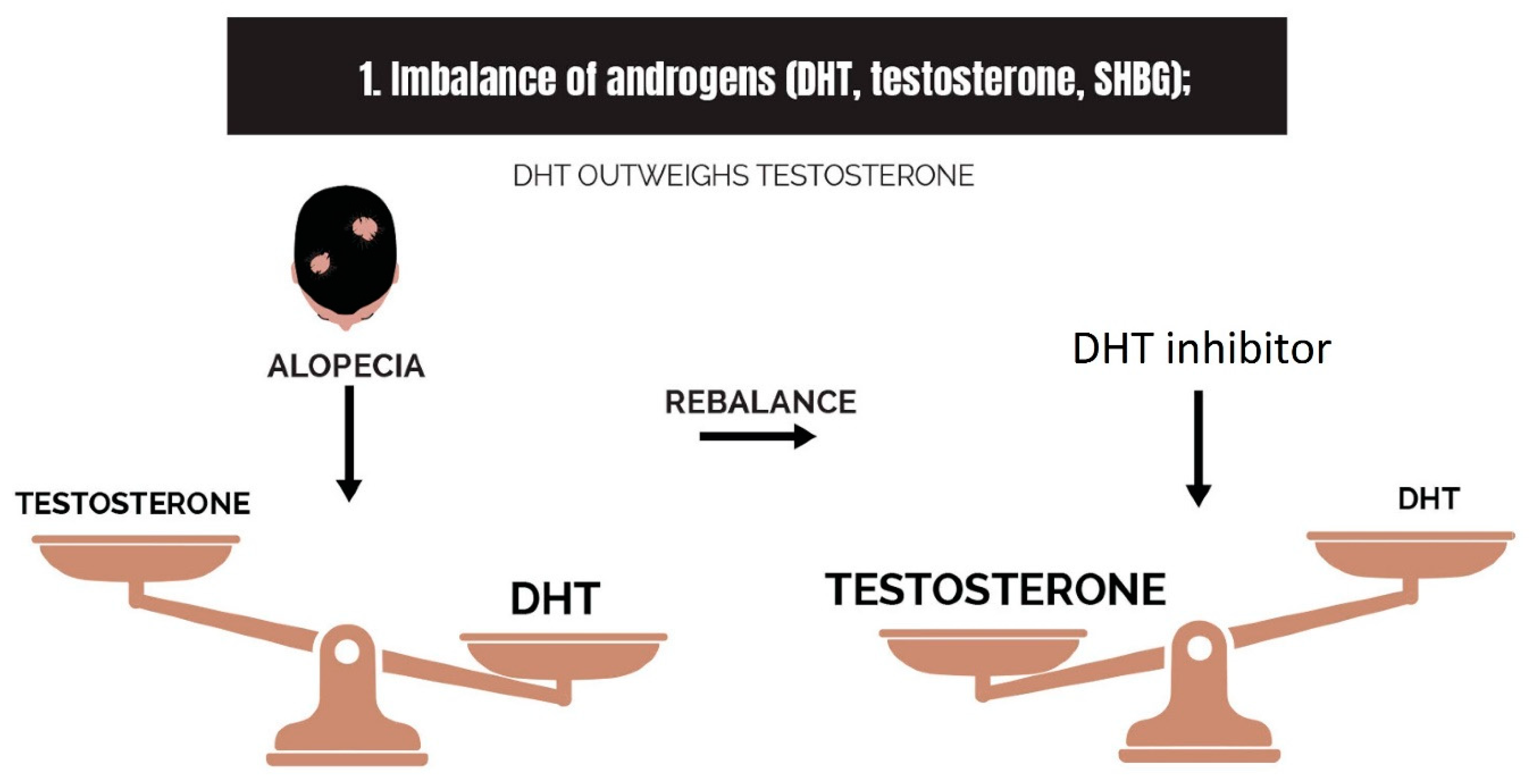

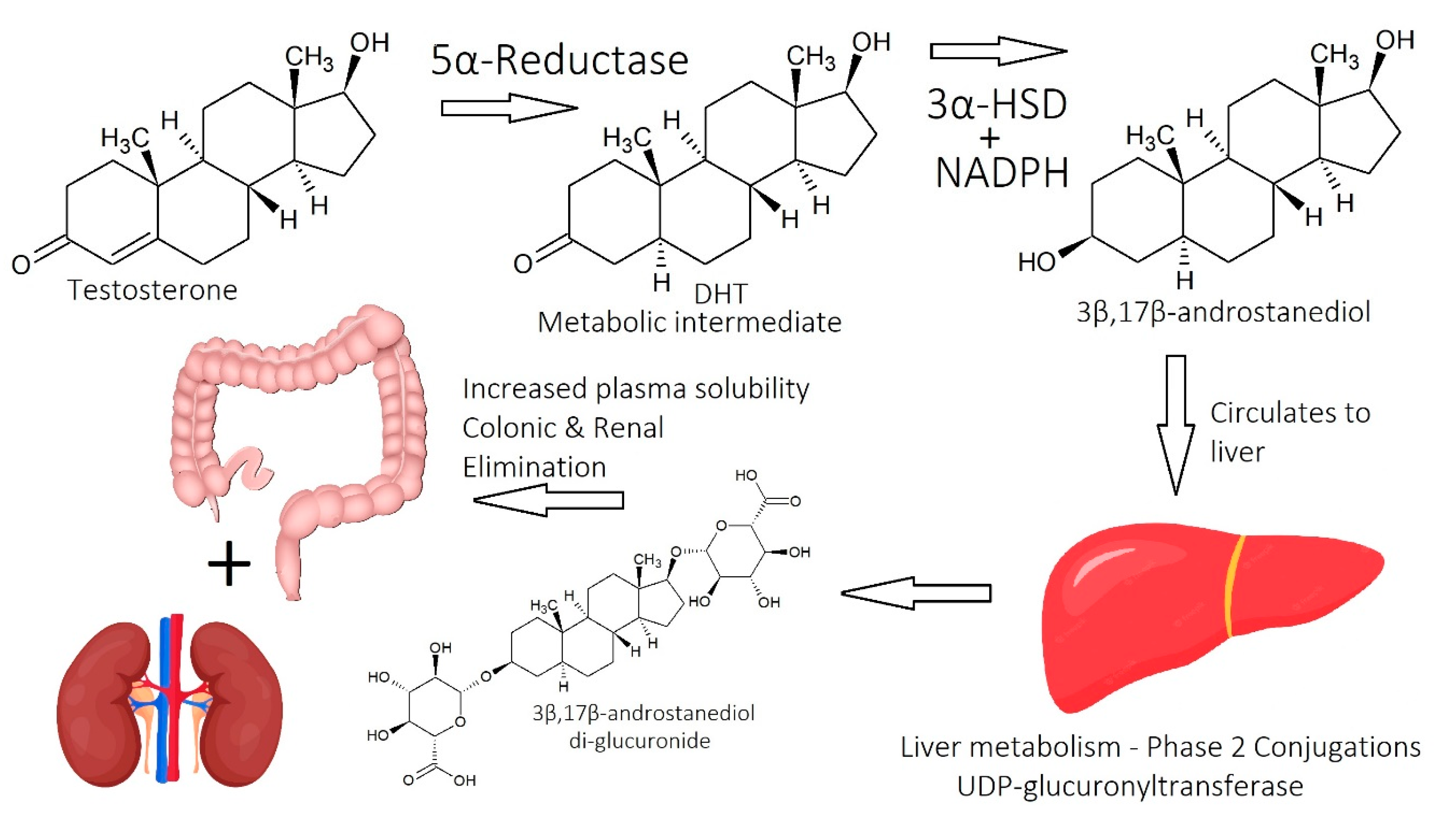

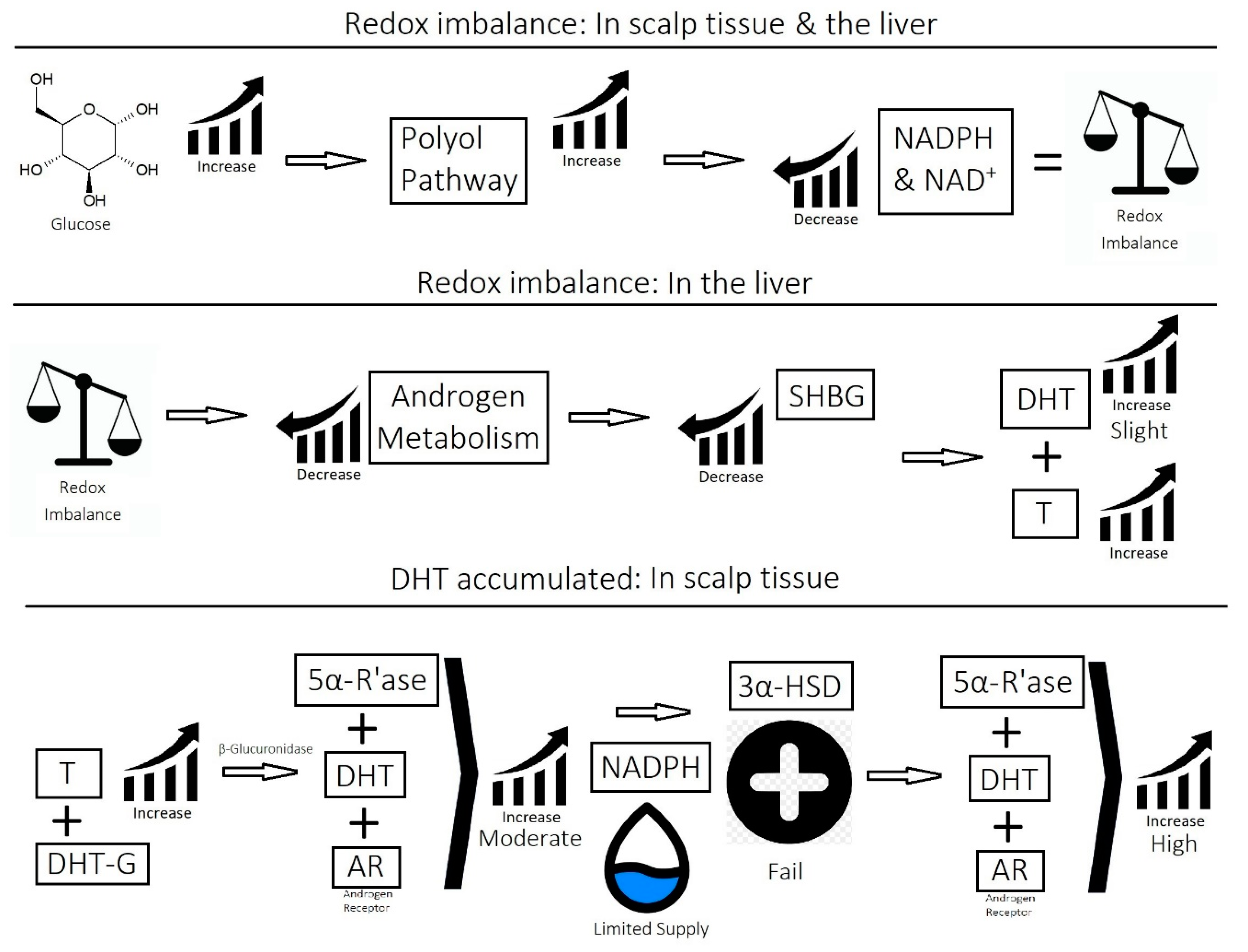

2.1. Imbalance of Androgens (DHT, Testosterone, and SHBG) in Cases of Androgenetic Alopecia

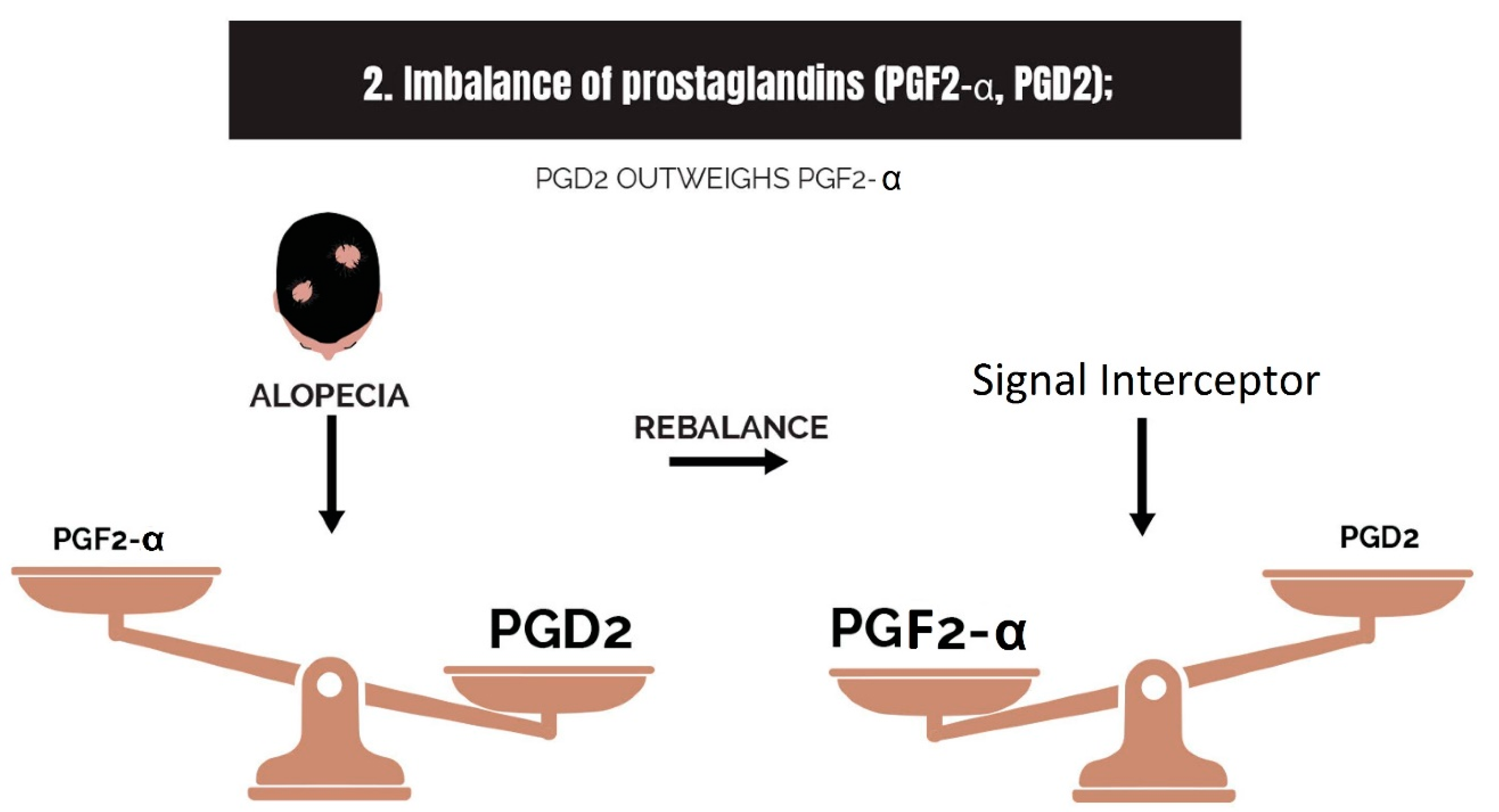

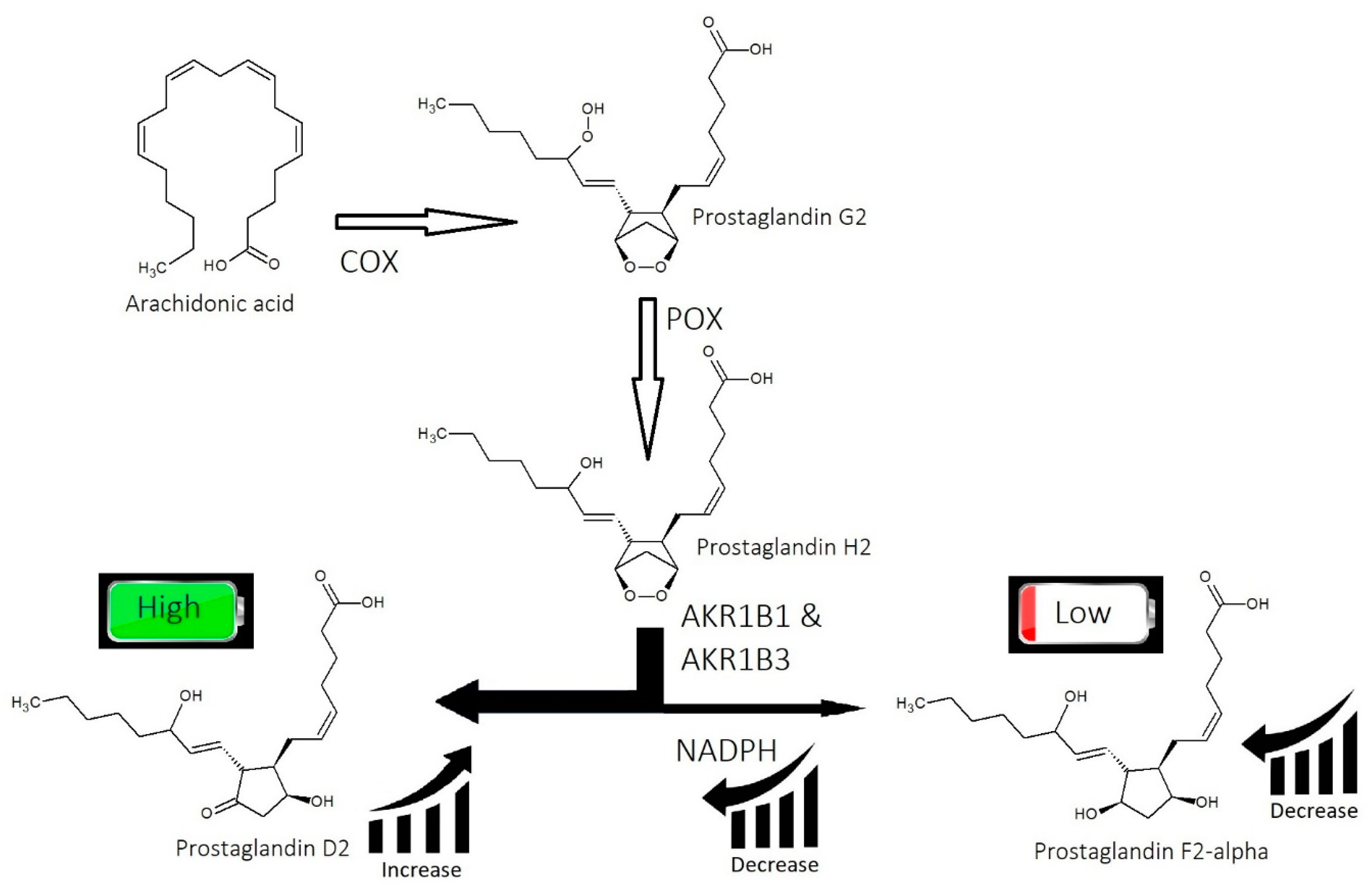

2.2. Imbalance of Prostaglandins (PGF2-α, PGD2)

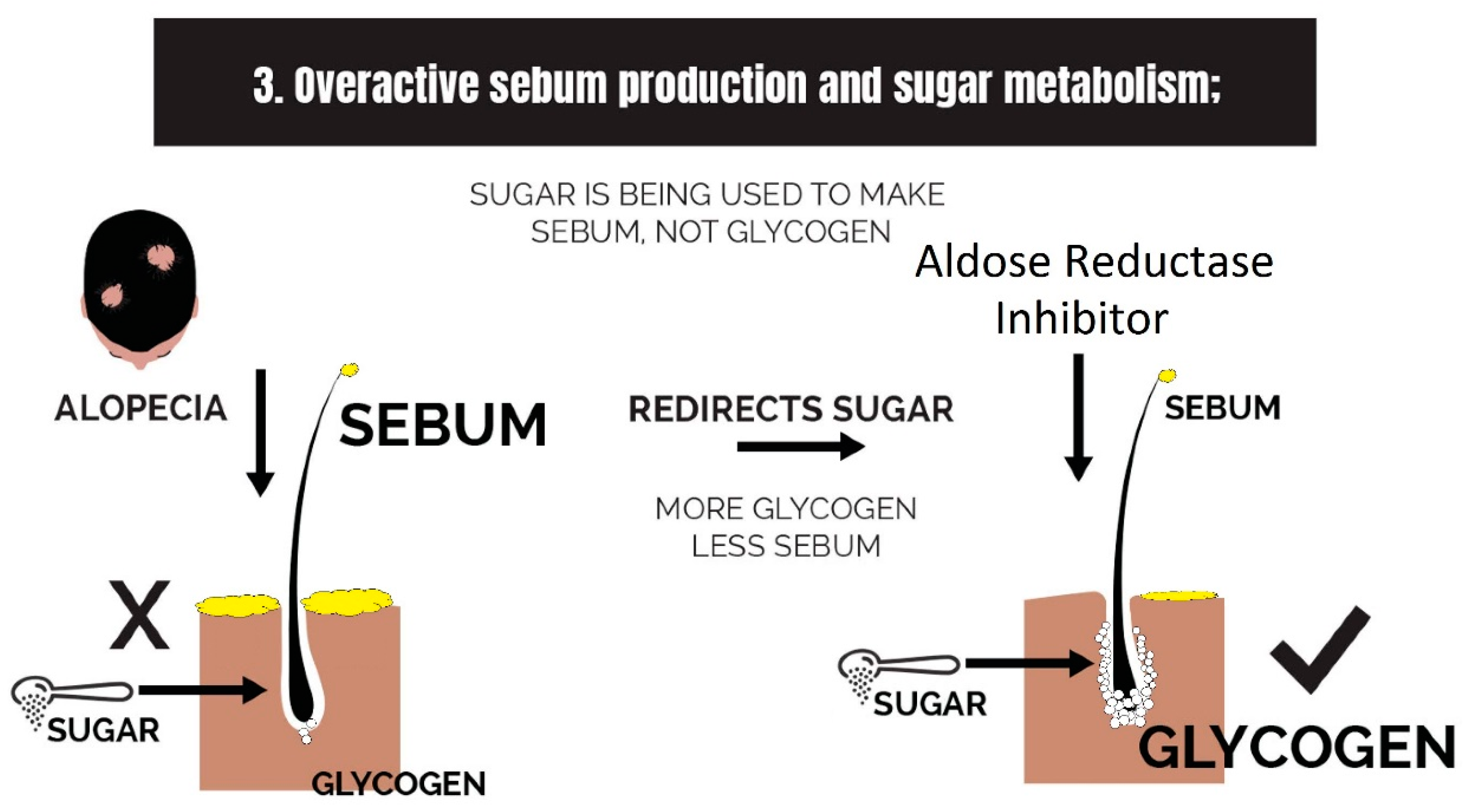

2.3. Overactive Sebum Production and Sugar Metabolism

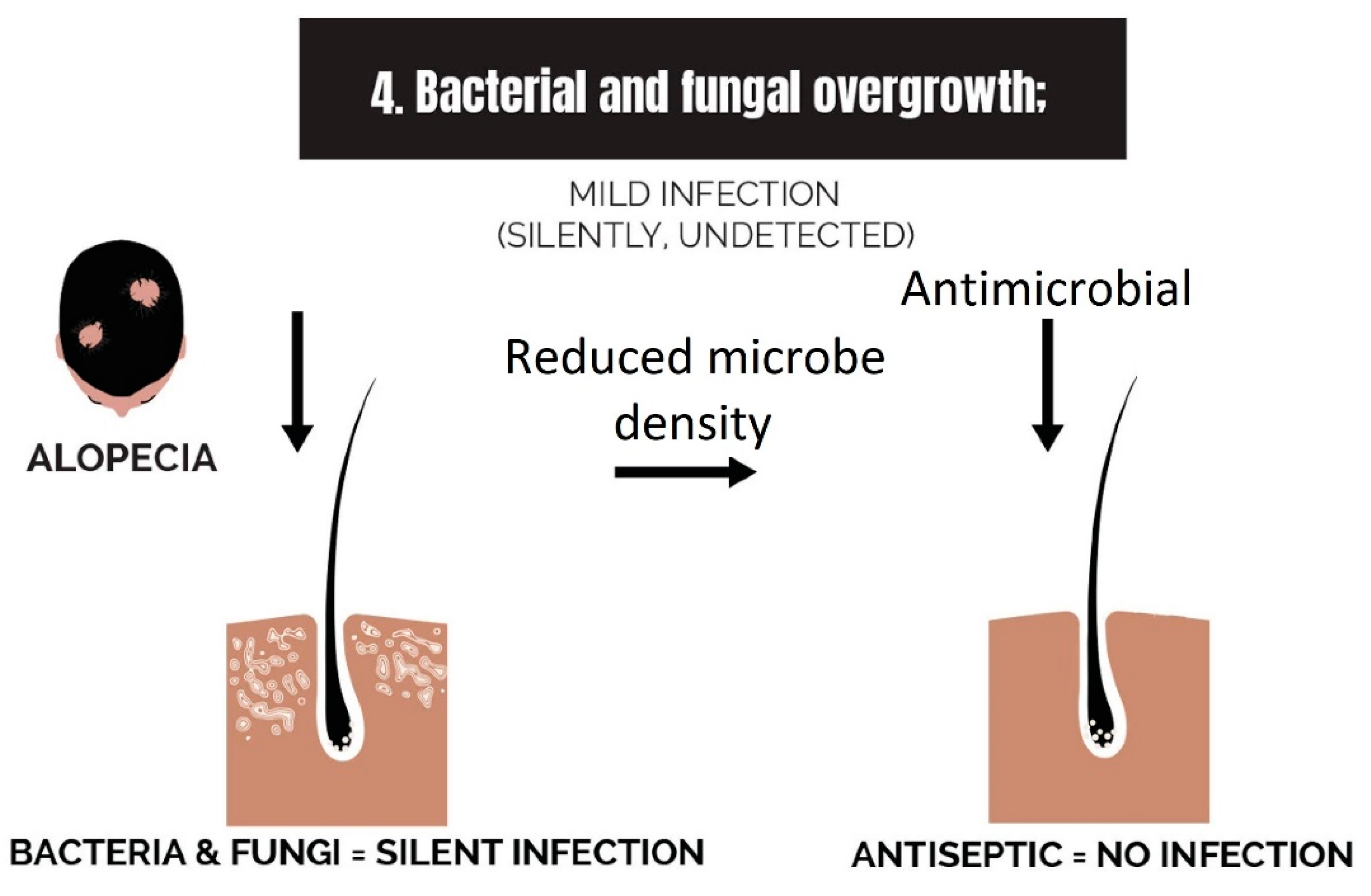

2.4. Bacterial and Fungal Overgrowth

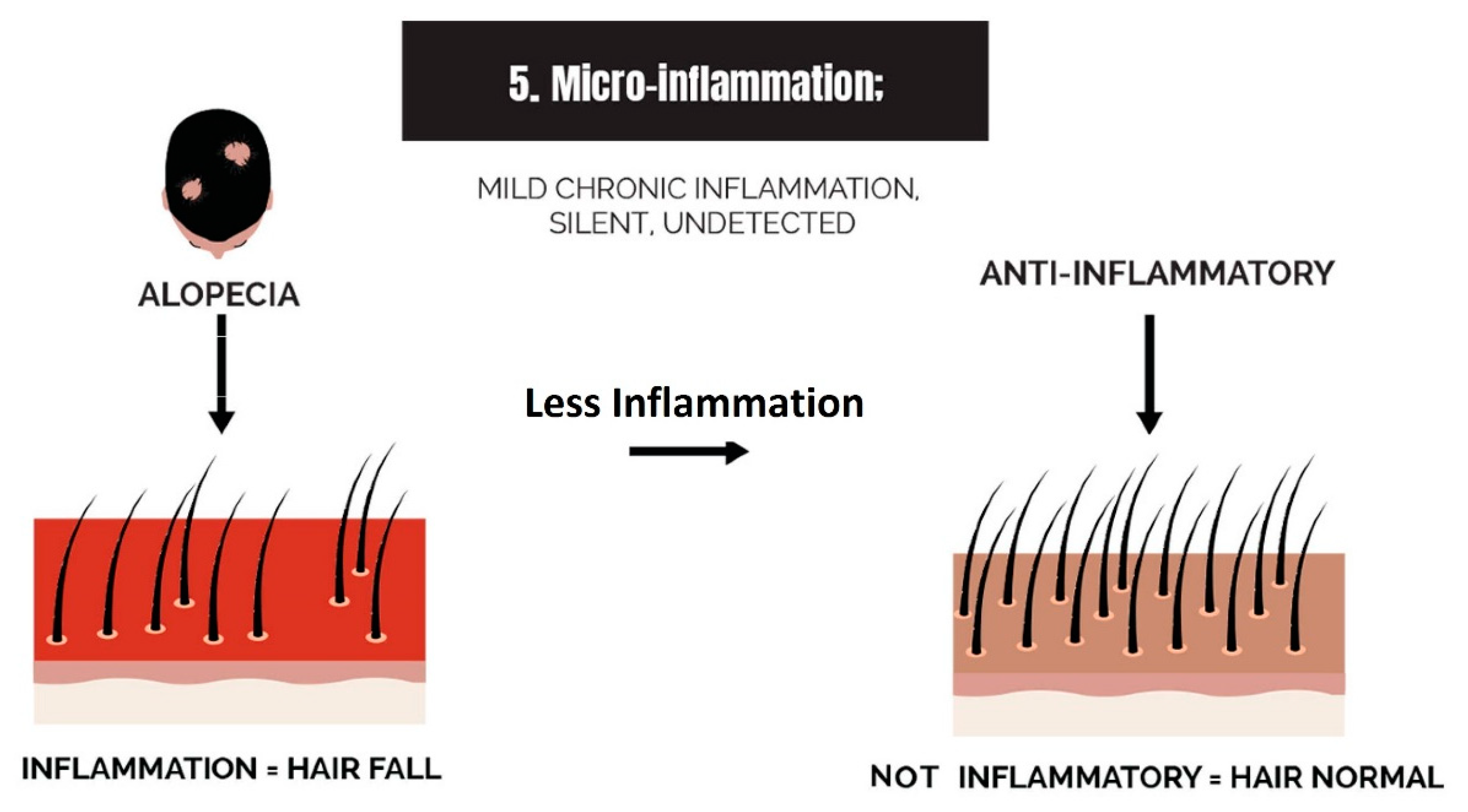

2.5. Micro-Inflammation

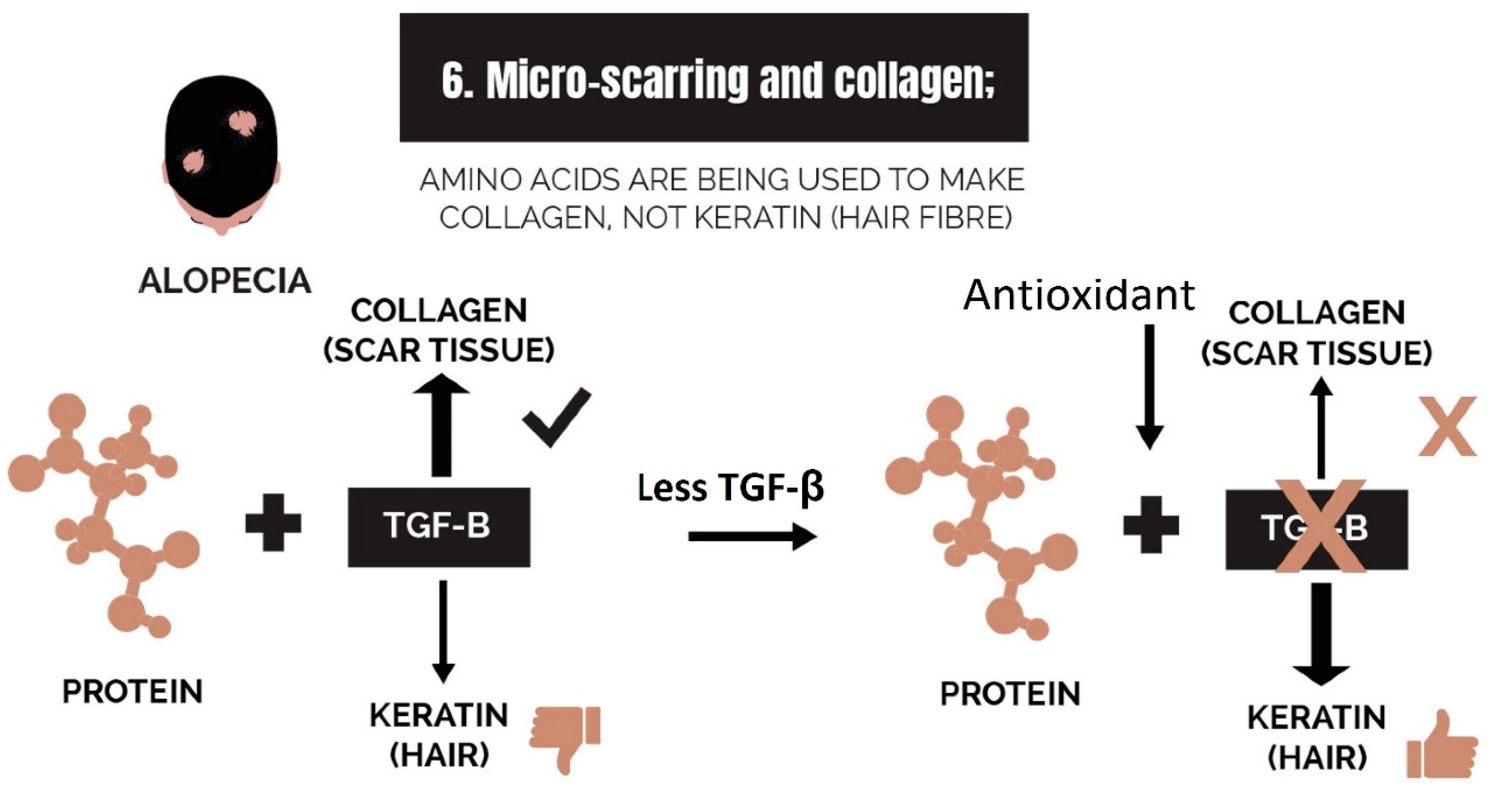

2.6. Micro-Scarring and Collagen

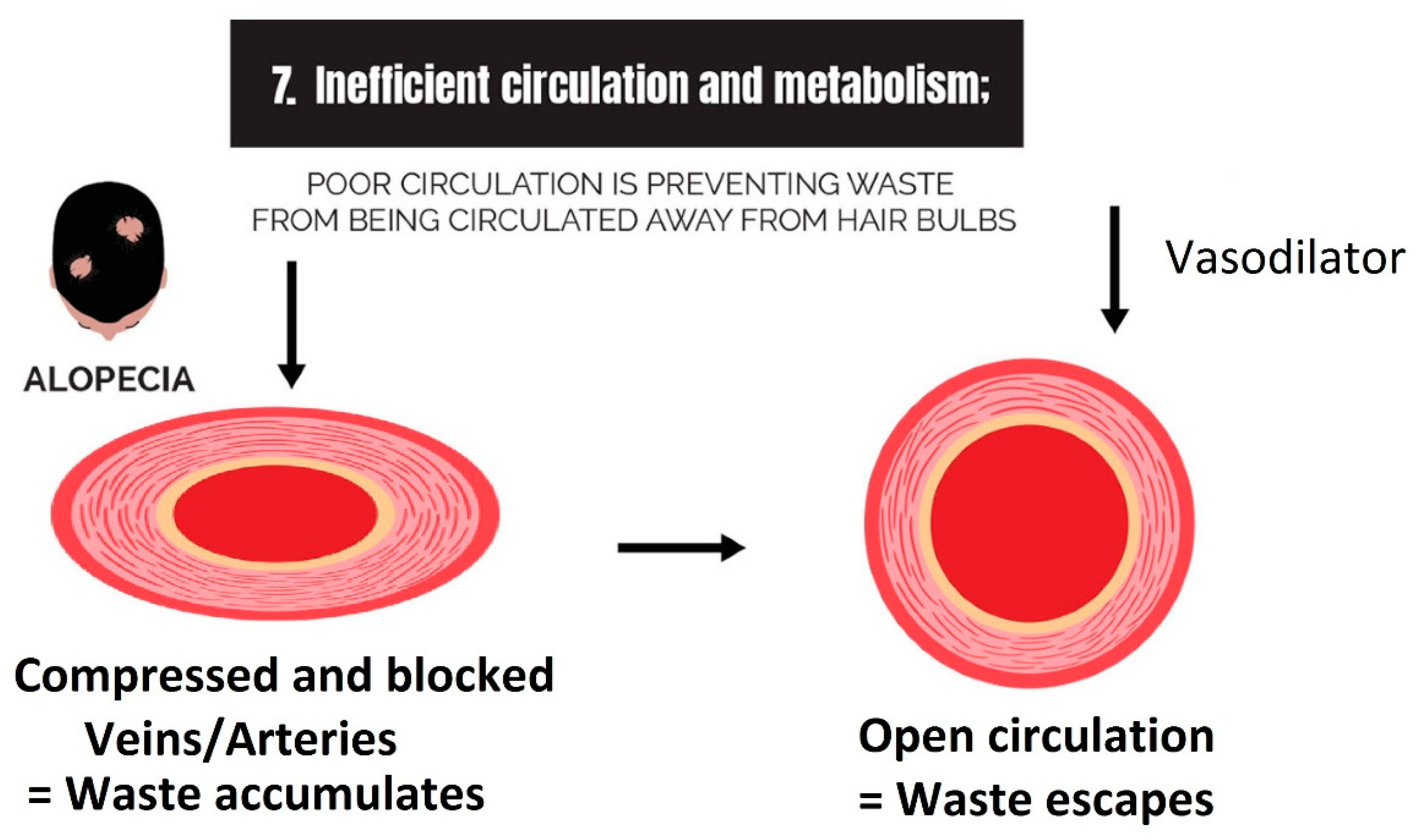

2.7. Inefficient Circulation and Metabolism

2.7.1. Circulation

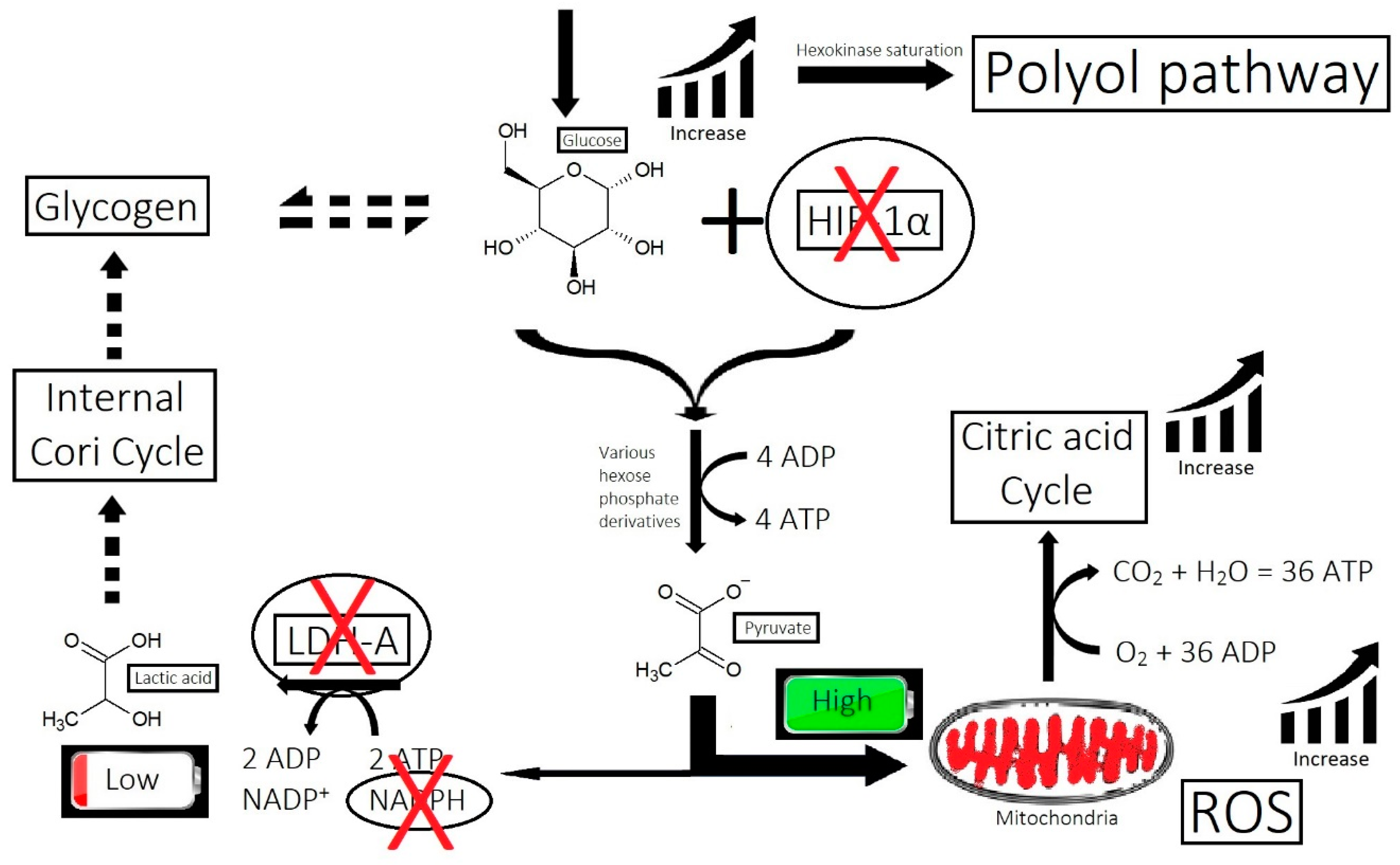

2.7.2. Metabolism

2.8. Nutrient Deficiency

3. Clearing the Big Eight Strikes with Cosmeceuticals to Improve Hair

3.1. Strike 1: Imbalance of Androgens

3.2. Strike 2: Imbalance of Prostaglandins

3.3. Strike 3: Sebum and Sugar Metabolism

3.4. Strike 4: Bacterial and Fungal Overgrowth

3.5. Strike 5: Micro-Inflammation

3.6. Strike 6: Micro-Scarring and Collagen

3.7. Strike 7: Inefficient Circulation and Metabolism

3.8. Strike 8: Nutrient Deficiency

4. Critical Examination of a Selection of Exemplary Cosmeceuticals in the Market

4.1. RedensylTM Ingredients

- -

- Strike 1 (androgens)

- ▪

- EGCG glucoside binds to 5α-reductase [183].

- -

- Strike 2 (prostaglandins);

- ▪

- The antimicrobial properties of taxifolin [184] may indirectly benefit prostaglandin balance.

- -

- Strike 3 (sebum and sugar);

- ▪

- Taxifolin is an aldose reductase inhibitor [185].

- -

- Strike 4 (bacteria/fungi);

- ▪

- Taxifolin is antimicrobial against Gram-positive bacteria [184].

- -

- Strike 5 (micro-inflammation);

- -

- Strike 8 (nutrients).

- ▪

- Zinc and glycine are nutritional.

4.2. CapixylTM Ingredients

4.3. Anasenzyl® Ingredients

- -

- Strike 5 (micro-inflammation);

- ▪

- Ammonium glycyrrhizate is anti-inflammatory [190].

- -

- Strike 6 (collagen/fibrosis);

- ▪

- Aesculus hippocastanum seed extract controls the differentiation of fibroblasts, reducing fibrosis development [170].

- -

- Strike 7 (circulation/metabolism);

- ▪

- Caffeine is a vasodilator [171].

- -

- Strike 8 (nutrients).

- ▪

- Zinc gluconate is a source of zinc.

4.4. Procapil® Ingredients

- -

- Strike 1 (androgens);

- -

- Strike 5 (micro-inflammation);

- -

- Strike 6 (collagen/fibrosis).

- ▪

- Biotinoyl tripeptide-1 is a derivative of GHK for penetration improvement. It signals a restructuring of the dermis, which reduces collagenous material and reactivates stem cell niches [42].

4.5. AnaGainTM Ingredients

4.6. Concentration, Clinical Efficacy, and Combining the Proprietary Blends

5. Conclusions

- Imbalance of androgens (DHT, testosterone, and SHBG) in cases of androgenetic alopecia: DHT triggers the expression of TGF-β1, which is reciprocal to the canonical Wnt signaling pathway.

- Imbalance of prostaglandins (PGF2-α, PGD2): Depletion of NADPH redirects the biosynthesis of prostaglandins toward PGD2. This may be jointly caused by bacterial overgrowth of P. acnes and the polyol pathway.

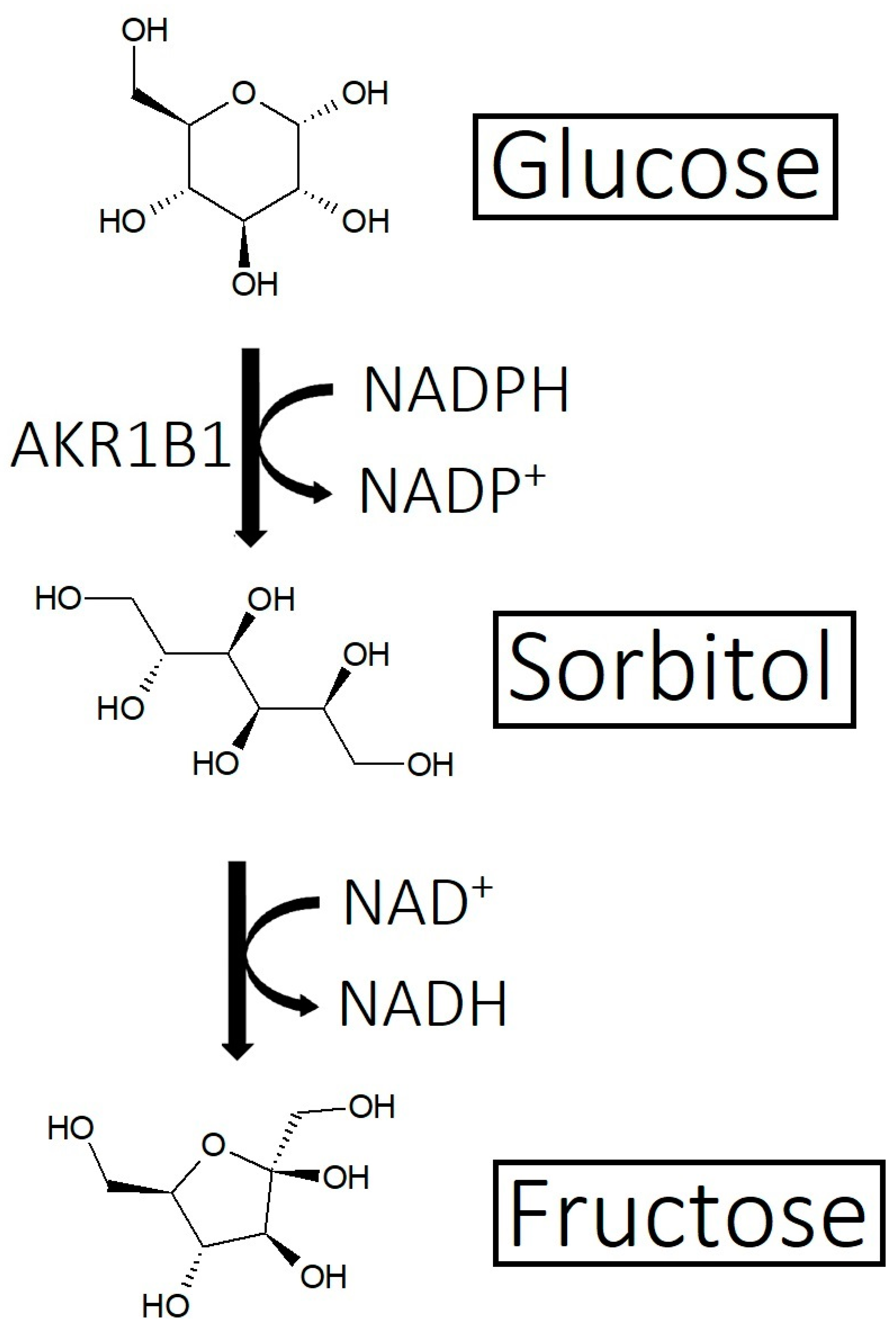

- Overactive sebum production and sugar metabolism: Prostaglandins and the polyol pathway change the metabolism of sugar so that lipid is produced in favor of glycogen stores; this may be due to increased expression of AKR1B1, a substrate for prostaglandin synthesis, and a trigger of the polyol pathway; insulin-like growth factor 1 is under-expressed in the balding scalp, and this may be why the glycogen stores are depleted.

- Bacterial and fungal overgrowth: Scalps afflicted with hair loss generally have bacterial overgrowth or inflammatory infiltrates as byproducts of clearing microbes. The bacteria can be P. acnes or S. aureus (in cases of scarring alopecia). The fungus is M. furfur.

- Micro-inflammation: Inflammation in the balding scalp can be severe, such as in scarring alopecia, or it can be low-grade chronic, such as in AGA. The term micro-inflammation was coined because candidates are unaware of the inflammation in AGA; it is subtle.

- Micro-scarring and collagen: While therapies can halt the progression of fibrosis, it is difficult to reverse it. The best approach is via the use of biomimetic peptides that signal a restructuring of the dermis and promote a return of the stem cell niche.

- Inefficient circulation and metabolism (i.e., cholesterol and scalp tension): Circulation is two-fold. It involves the transport of nutrients to the scalp, and it is equally as important to transport waste out. The elimination of waste can be antagonized by the inactivity of metabolizing enzymes that are responsible for converting waste into soluble forms, such as the metabolism of cholesterol.

- Nutrient deficiency (or nutrient synthesis via metabolism, i.e., vitamin D): Nutrient deficiencies can be corrected with supplementation, but the benefit can also be experienced by supplementing an item in the absence of a deficiency of that item, such as by the addition of amino acids to the diet. Furthermore, a deficiency can be caused by a failure of local metabolic processes that create nutrients, such as vitamin D, which can be adequate in terms of dietary intake but is not being utilized by hair follicles in balding scalps.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wall, D.; Meah, N.; Fagan, N.; York, K.; Sinclair, R. Advances in hair growth. Fac. Rev. 2022, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houschyar, K.S.; Borrelli, M.R.; Tapking, C.; Popp, D.; Puladi, B.; Ooms, M.; Chelliah, M.P.; Rein, S.; Pförringer, D.; Thor, D.; et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Hair Growth and Regeneration: Current Understanding and Novel Paradigms. Dermatology 2020, 236, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, D.; Sorbellini, E.; Marzani, B.; Rucco, M.; Giuliani, G.; Rinaldi, F. Scalp bacterial shift in Alopecia areata. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolduc, C.; Sperling, L.C.; Shapiro, J. Primary cicatricial alopecia: Other lymphocytic primary cicatricial alopecias and neutrophilic and mixed primary cicatricial alopecias. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 75, 1101–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.K.; Summerbell, R.C. Tinea capitis. Med. Mycol. 2000, 38, 255–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadgrove, N.J. The ‘bald’ phenotype (androgenetic alopecia) is caused by the high glycaemic, high cholesterol and low mineral ‘western diet’. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 1170–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, C.H.; King, L.E.; Messenger, A.G.; Christiano, A.M.; Sundberg, J.P. Alopecia areata. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017, 3, 17011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, V.A. Molecular Basis of Androgenetic Alopecia. In Aging Hair; Trüeb, R.M., Tobin, D.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuangtong, R. Vertex Accentuation in Female Pattern Hair Loss in Asians. Siriraj Med. J. 2016, 68, 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, C.N.; Bakayoko, A.; Callender, V.D. Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia: Challenges and Treatments. Dermatol. Clin. 2021, 39, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filbrandt, R.; Rufaut, N.; Jones, L.; Sinclair, R. Primary cicatricial alopecia: Diagnosis and treatment. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2013, 185, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oremović, L.; Lugović, L.; Vucić, M.; Buljan, M.; Ozanić-Bulić, S. Cicatricial alopecia as a manifestation of different dermatoses. Acta Dermatovenerol. Croat. ADC 2006, 14, 246–252. [Google Scholar]

- Rigopoulos, D.; Stamatios, G.; Ioannides, D. Primary Scarring Alopecias. In Alopecias-Practical Evaluation and Management; Ioannides, D., Tosti, A., Eds.; Current Problems in Dermatology; Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers: Basel, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 47, pp. 76–86. [Google Scholar]

- Harries, M.J.; Trueb, R.M.; Tosti, A.; Messenger, A.G.; Chaudhry, I.; Whiting, D.A.; Sinclair, R.; Griffiths, C.E.; Paus, R. How not to get scar(r)ed: Pointers to the correct diagnosis in patients with suspected primary cicatricial alopecia. Br. J. Dermatol. 2009, 160, 482–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, D.A. Cicatricial alopecia: Clinico-pathological findings and treatment. Clin. Dermatol. 2001, 19, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paus, R.; Haslam, I.S.; Sharov, A.A.; Botchkarev, V.A. Pathobiology of chemotherapy-induced hair loss. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, e50–e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daunton, A.; Harries, M.; Sinclair, R.; Paus, R.; Tosti, A.; Messenger, A. Chronic Telogen Effluvium: Is it a Distinct Condition? A Systematic Review. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, R.J. Tinea Capitis: Current Status. Mycopathologia 2017, 182, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billero, V.; Miteva, M. Traction alopecia: The root of the problem. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 11, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, J.E.; Dougherty, D.D.; Chamberlain, S.R. Prevalence, gender correlates, and co-morbidity of trichotillomania. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.-J.; Cheng, A.-Y.; Liu, C.-H.; Chu, C.-B.; Lee, C.-N.; Hsu, C.-K.; Lee, J.Y.-Y.; Yang, C.-C. Primary scarring alopecia: A retrospective study of 89 patients in Taiwan. J. Dermatol. 2018, 45, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villablanca, S.; Fischer, C.; García-García, S.C.; Mascaró-Galy, J.M.; Ferrando, J. Primary Scarring Alopecia: Clinical-Pathological Review of 72 Cases and Review of the Literature. Ski. Appendage Disord. 2017, 3, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebora, A.; Guarrera, M.; Baldari, M.; Vecchio, F. Distinguishing Androgenetic Alopecia from Chronic Telogen Effluvium When Associated in the Same Patient: A Simple Noninvasive Method. Arch. Dermatol. 2005, 141, 1243–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zinkernagel, M.S.; Med, C.; Trüeb, R.M. Fibrosing Alopecia in a Pattern Distribution: Patterned Lichen Planopilaris or Androgenetic Alopecia with a Lichenoid Tissue Reaction Pattern? Arch. Dermatol. 2000, 136, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadgrove, N.J. The new paradigm for androgenetic alopecia and plant-based folk remedies: 5α-reductase inhibition, reversal of secondary microinflammation and improving insulin resistance. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 227, 206–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habashi-Daniel, A.; Roberts, J.L.; Desai, N.; Thompson, C.T. Absence of catagen/telogen phase and loss of cytokeratin 15 expression in hair follicles in lichen planopilaris. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014, 71, 969–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, N.; Doshi, B.; Khopkar, U. Trichoscopy in alopecias: Diagnosis simplified. Int. J. Trichol. 2013, 5, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Seol, J.E.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, H. Analysis of Microscopic Examination of Pulled out Hair in Telogen Effluvium Patients. Ann. Dermatol. 2020, 32, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElwee, K.J.; Gilhar, A.; Tobin, D.J.; Ramot, Y.; Sundberg, J.P.; Nakamura, M.; Bertolini, M.; Inui, S.; Tokura, Y.; King, L.E.; et al. What causes alopecia areata? Exp. Dermatol. 2013, 22, 609–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Xu, Z.; Song, J.; Xie, Y.; Mei, X.; Shi, W. Efficacy of a mixed preparation containing piperine, capsaicin and curcumin in the treatment of alopecia areata. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 4510–4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żeberkiewicz, M.; Rudnicka, L.; Malejczyk, J. Immunology of alopecia areata. Cent. Eur. J. Nbsp Immunol. 2020, 45, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.H.C.; Yu, M.; Breitkopf, T.; Akhoundsadegh, N.; Wang, X.; Shi, F.T.; Leung, G.; Dutz, J.P.; Shapiro, J.; McElwee, K.J. Identification of Autoantigen Epitopes in Alopecia Areata. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2016, 136, 1617–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilhar, A.; Landau, M.; Assy, B.; Shalaginov, R.; Serafimovich, S.; Kalish, R.S. Melanocyte-associated T cell epitopes can function as autoantigens for transfer of alopecia areata to human scalp explants on Prkdc(scid) mice. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2001, 117, 1357–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, J.; Kaufman, K.D. Use of Finasteride in the Treatment of Men with Androgenetic Alopecia (Male Pattern Hair Loss). J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2003, 8, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Z.; Chen, M.; Liu, F.; Wang, Y.; Xu, S.; Sha, K.; Peng, Q.; Wu, Z.; Xiao, W.; Liu, T.; et al. Androgen Receptor–Mediated Paracrine Signaling Induces Regression of Blood Vessels in the Dermal Papilla in Androgenetic Alopecia. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 142, 2088–2099.e2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betriu, N.; Jarrosson-Moral, C.; Semino, C.E. Culture and Differentiation of Human Hair Follicle Dermal Papilla Cells in a Soft 3D Self-Assembling Peptide Scaffold. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, B.A. The Dermal Papilla: An Instructive Niche for Epithelial Stem and Progenitor Cells in Development and Regeneration of the Hair Follicle. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014, 4, a015180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwack, M.H.; Ahn, J.S.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, J.C.; Sung, Y.K. Dihydrotestosterone-Inducible IL-6 Inhibits Elongation of Human Hair Shafts by Suppressing Matrix Cell Proliferation and Promotes Regression of Hair Follicles in Mice. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2012, 132, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwack, M.H.; Sung, Y.K.; Chung, E.J.; Im, S.U.; Ahn, J.S.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, J.C. Dihydrotestosterone-Inducible Dickkopf 1 from Balding Dermal Papilla Cells Causes Apoptosis in Follicular Keratinocytes. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2008, 128, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, S.E. Molecular mechanisms regulating hair follicle development. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2002, 118, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, S.; Kiefer, A.K.; Fricker, N.; Drichel, D.; Hillmer, A.M.; Herold, C.; Tung, J.Y.; Eriksson, N.; Redler, S.; Betz, R.C.; et al. Androgenetic Alopecia: Identification of Four Genetic Risk Loci and Evidence for the Contribution of WNT Signaling to Its Etiology. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 1489–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadgrove, N.J.; Simmonds, M.S.J. Topical and nutricosmetic products for healthy hair and dermal anti-aging using ‘dual-acting’ (2 for 1) plant-based peptides, hormones, and cannabinoids. FASEB BioAdv. 2021, 3, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Yoo, H.G.; Inui, S.; Itami, S.; Kim, I.G.; Cho, A.-R.; Lee, D.H.; Park, W.S.; Kwon, O.; Cho, K.H.; et al. Induction of transforming growth factor-beta 1 by androgen is mediated by reactive oxygen species in hair follicle dermal papilla cells. BMB Rep. 2013, 46, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.-Q.; Wu, Z.-B.; Chu, X.-Y.; Bi, Z.-G.; Fan, W.-X. An investigation of crosstalk between Wnt/β-catenin and transforming growth factor-β signaling in androgenetic alopecia. Medicine 2016, 95, e4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhmetshina, A.; Palumbo, K.; Dees, C.; Bergmann, C.; Venalis, P.; Zerr, P.; Horn, A.; Kireva, T.; Beyer, C.; Zwerina, J.; et al. Activation of canonical Wnt signalling is required for TGF-β-mediated fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philips, N.; Auler, S.; Hugo, R.; Gonzales, S. Beneficial regulation of matrix metalloproteinases for skin health. Enzym. Res. 2011, 2011, 427286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beoy, L.A.; Woei, W.J.; Hay, Y.K. Effects of tocotrienol supplementation on hair growth in human volunteers. Trop. Life Sci. Res. 2010, 21, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yanagisawa, M.; Fujimaki, H.; Takeda, A.; Nemoto, M.; Sugimoto, T.; Sato, A. Long-term (10-year) efficacy of finasteride in 523 Japanese men with androgenetic alopecia. Clin. Res. Trials 2019, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PFS. Post-Finasteride Syndrome Foundation. Available online: https://www.pfsfoundation.org/ (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Diviccaro, S.; Melcangi, R.C.; Giatti, S. Post-finasteride syndrome: An emerging clinical problem. Neurobiol. Stress 2020, 12, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traish, A.M. Post-finasteride syndrome: A surmountable challenge for clinicians. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 113, 21–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, D.J.; Hodges, S. Medical therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia: Sexual dysfunction and impact on quality of life. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2003, 15, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baas, W.R.; Butcher, M.J.; Lwin, A.; Holland, B.; Herberts, M.; Clemons, J.; Delfino, K.; Althof, S.; Kohler, T.S.; McVary, K.T. A Review of the FAERS Data on 5-Alpha Reductase Inhibitors: Implications for Postfinasteride Syndrome. Male Sex. Dysfunct. 2018, 120, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harries, M.J.; Paus, R. The Pathogenesis of Primary Cicatricial Alopecias. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 177, 2152–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somani, N.; Bergfeld, W.F. Cicatricial alopecia: Classification and histopathology. Dermatol. Therapy. 2008, 21, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumalo, N.P.; Pillay, K.; Ngwanya, R.M. Acute ‘relaxer’-associated scarring alopecia: A report of five cases. Br. J. Dermatol. 2007, 156, 1394–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subash, J.; Alexander, T.; Beamer, V.; McMichael, A. A proposed mechanism for central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 29, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harries, M.J.; Sinclair, R.D.; MacDonald-Hull, S.; Whiting, D.A.; Griffiths, C.E.M.; Paus, R. Management of primary cicatricial alopecias: Options for treatment. Br. J. Dermatol. 2008, 159, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polak-Witka, K.; Rudnicka, L.; Blume-Peytavi, U.; Vogt, A. The role of the microbiome in scalp hair follicle biology and disease. Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 29, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.; Shapiro, J. Medical therapy for frontal fibrosing alopecia: A review and clinical approach. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 81, 568–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnchoowong, S.; Suchonwanit, P. PPAR-γ Agonists and Their Role in Primary Cicatricial Alopecia. PPAR Res. 2017, 2017, 2501248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.-Y.; Cheng, T.; Zheng, M.-H.; Yi, C.-G.; Pan, H.; Li, Z.-J.; Chen, X.-L.; Yu, Q.; Jiang, L.-F.; Zhou, F.-Y.; et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) agonist inhibits transforming growth factor-beta1 and matrix production in human dermal fibroblasts. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2010, 63, 1209–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, B.S.-Y.; Ho, E.X.P.; Chu, C.W.; Ramasamy, S.; Bigliardi-Qi, M.; de Sessions, P.F.; Bigliardi, P.L. Microbiome in the hair follicle of androgenetic alopecia patients. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trüeb, R.M. Telogen Effluvium: Is There a Need for a New Classification? Ski. Appendage Disord. 2016, 2, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebora, A. Proposing a Simpler Classification of Telogen Effluvium. Ski. Appendage Disord. 2016, 2, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkud, S. Telogen Effluvium: A Review. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, We01–We03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thom, E. Stress and the Hair Growth Cycle: Cortisol-Induced Hair Growth Disruption. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2016, 15, 1001–1004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sorriento, D.; Iaccarino, G. Inflammation and Cardiovascular Diseases: The Most Recent Findings. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarnieri, G.; Bertagna De Marchi, L.; Marcon, A.; Panunzi, S.; Batani, V.; Caminati, M.; Furci, F.; Senna, G.; Alaibac, M.; Vianello, A. Relationship between hair shedding and systemic inflammation in COVID-19 pneumonia. Ann. Med. 2022, 54, 869–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, R. Male pattern androgenetic alopecia. BMJ 1998, 317, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarrera, M.; Rebora, A. The Higher Number and Longer Duration of Kenogen Hairs Are the Main Cause of the Hair Rarefaction in Androgenetic Alopecia. Ski. Appendage Disord. 2019, 5, 152–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, R.; Ruiz, S. Conflicting Reports Regarding the Histopathological Features of Androgenic Alopecia: Are Biopsy Location, Hair Diameter Diversity, and Relative Hair Follicle Miniaturization Partly to Blame? Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 14, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza, L.A.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Alagesan, B.; Lawson, J.A.; Norberg, S.M.; Loy, D.E.; Zhao, T.; Blatt, H.B.; Stanton, D.C.; et al. Prostaglandin D2 inhibits hair growth and is elevated in bald scalp of men with androgenetic alopecia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 126ra134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.H.; Jung, J.H.; Kim, J.E.; Kang, H. Prostaglandin D2-mediated DP2 and AKT signal regulate the activation of androgen receptors in human dermal papilla cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, B.S.-Y.; Vaz, C.; Ramasamy, S.; Chew, E.G.Y.; Mohamed, J.S.; Jaffar, H.; Hillmer, A.; Tanavde, V.; Bigliardi-Qi, M.; Bigliardi, P.L. Progressive expression of PPARGC1α is associated with hair miniaturization in androgenetic alopecia. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Redondo, V.; Pettersson, A.T.; Ruas, J.L. The hitchhiker’s guide to PGC-1α isoform structure and biological functions. Diabetologia 2015, 58, 1969–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horii, N.; Hasegawa, N.; Fujie, S.; Uchida, M.; Iemitsu, M. Resistance exercise-induced increase in muscle 5α-dihydrotestosterone contributes to the activation of muscle Akt/mTOR/p70S6K- and Akt/AS160/GLUT4-signaling pathways in type 2 diabertic rats. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 11047–11057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshihara, Y.; Kawamura, M. Prostaglandin D2 stimulates calcification of human osteoblast cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1989, 159, 1206–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, R.S. A hypothetical pathogenesis model for androgenic alopecia: Clarifying the dihydrotestosterone paradox and rate-limiting recovery factors. Med. Hypotheses 2018, 111, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal-Villarreal, C.D.; Sinclair, R.D.; Martínez-Jacobo, L.; Garza-Rodríguez, V.; Rodríguez-León, S.A.; Lamadrid-Zertuche, A.C.; Rodríguez-Gutierrez, R.; Ortiz-Lopez, R.; Rojas-Martinez, A.; Ocampo-Candiani, J. Prostaglandins in androgenetic alopecia in 12 men and four female. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, e214–e215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, S.; Hozumi, Y.; Kondo, S. Influence of prostaglandin F2α and its analogues on hair regrowth and follicular melanogenesis in a murine model. Exp. Dermatol. 2005, 14, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chovarda, E.; Sotiriou, E.; Lazaridou, E.; Vakirlis, E.; Ioannides, D. The role of prostaglandins in androgenetic alopecia. Int. J. Dermatol. 2021, 60, 730–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iinuma, K.; Sato, T.; Akimoto, N.; Noguchi, N.; Sasatsu, M.; Nishijima, S.; Kurokawa, I.; Ito, A. Involvement of Priopionibacterium acnes in the augmentation of lipogenesis in hamster sebaceous glans in vivo and in vitro. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 2113–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, S.G.; Phipps, R.P. Prostaglandin D2, its metabolite 15-d-PGJ2, and peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ agonists induce apoptosis in transformed, but not normal, human T lineage cells. Immunology 2002, 105, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schadinger, S.E.; Bucher, N.L.R.; Schreiber, B.M.; Farmer, S.R. PPARγ2 regulates lipogenesis and lipid accumulation in steatotic hepatocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 288, E1195–E1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bie, Q.; Dong, H.; Jin, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, B. 15d-PGJ2 is a new hope for controlling tumor growth. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2018, 10, 648–658. [Google Scholar]

- Iwata, C.; Akimoto, N.; Sato, T.; Morokuma, Y.; Ito, A. Augmentation of Lipogenesis by 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-Prostaglandin J2 in Hamster Sebaceous Glands: Identification of Cytochrome P-450-mediated 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-Prostaglandin J2 Production. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2005, 125, 865–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, R.J.; Sánchez-Lozada, L.G.; Andrews, P.; Lanaspa, M.A. Perspective: A historical and scientific perspective of sugar and its relation with obesity and diabetes. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagata, N.; Kusakari, Y.; Fukunishi, Y.; Inoue, T.; Urade, Y. Catalytic mechanism of the primary human prostaglandin F2α synthase, aldo-keto reductase 1B1--prostaglandin D2 synthase activity in the absence of NADP(H). FEBS J. 2011, 278, 1288–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabututu, Z.; Manin, M.; Pointud, J.C.; Maruyama, T.; Nagata, N.; Lambert, S.; Lefrançois-Martinez, A.M.; Martinez, A.; Urade, Y. Prostaglandin F2alpha synthase activities of aldo-keto reductase 1B1, 1B3 and 1B7. J. Biochem. 2009, 145, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.J. Redox imbalance stress in diabetes mellitus: Role of the polyol pathway. Anim. Model. Exp. Med. 2018, 1, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix Pépin, N.; Chapdelaine, P.; Fortier, M.A. Evaluation of the prostaglandin F synthase activity of human and bovine aldo-keto reductases: AKR1A1s complement AKR1B1s as potent PGF synthases. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2013, 106, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansmann, H.C. Consider magnesium homeostasis: III: Cytochrome P450 enzymes and drug toxicity. Padiatr. ASthma Allergy Immunol. 1994, 8, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharam Kumar, K.C.; Kishan Kumar, Y.H.; Neladimmanahally, V. Association of Androgenetic Alopecia with Metabolic Syndrome: A Case-control Study on 100 Patients in a Tertiary Care Hospital in South India. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 22, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matilainen, V.; Koskela, P.; Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi, S. Early androgenetic alopecia as a marker of insulin resistance. Lancet 2000, 356, 1165–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakry, O.A.; Shoeib, M.A.M.; El Shafiee, M.K.; Hassan, A. Androgenetic alopecia, metabolic syndrome, and insulin resistance: Is there any association? A case-control study. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2014, 5, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Santiago, S.; Gutiérrez-Salmerón, M.T.; Buendía-Eisman, A.; Girón-Prieto, M.S.; Naranjo-Sintes, R. Sex hormone-binding globulin and risk of hyperglycemia in patients with androgenetic alopecia. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2011, 65, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaikittisilpa, S.; Rattanasirisin, N.; Panchaprateep, R.; Orprayoon, N.; Phutrakul, P.; Suwan, A.; Jaisamrarn, U. Prevalence of female pattern hair loss in postmenopausal women: A cross-sectional study. Menopause 2022, 29, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Tuan, H.; Na, X.; Yang, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xi, M.; Tan, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhang, J.; et al. The Association between Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Male Pattern Hair Loss in Young Men. Nutrients 2023, 15, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, E.G.Y.; Ho, B.S.-Y.; Ramasamy, S.; Dawson, T.; Tennakoon, C.; Liu, X.; Leong, W.M.S.; Yang, W.Y.S.; Lim, S.Y.D.; Jaffar, H.; et al. Comparative transcriptome profiling provides new insights into mechanisms of androgenetic alopecia progression: Whole transcriptome discovery study identifies altered oxidation-reduction state of hair follicles of androgenetic alopecia patients. Br. J. Dermatol. 2017, 176, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figlak, K.; Paus, R.; Williams, G.; Philpott, M. 597 Outer root sheath is able to synthesise glycogen from lactate-investigating glycogen metabolism in human hair follicles. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2019, 139, S317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plikus, M.V.; Vollmers, C.; Cruz, D.d.l.; Chaix, A.; Ramos, R.; Panda, S.; Chuong, C.-M. Local circadian clock gates cell cycle progression of transient amplifying cells during regenerative hair cycling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E2106–E2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figlak, K.; Williams, G.; Bertolini, M.; Paus, R.; Philpott, M.P. Human hair follicles operate an internal Cori cycle and modulate their growth via glycogen phosphorylase. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, J.; Aas, V.; Tingstad, R.H.; Van Hees, A.; Nikolić, N. Utilization of lactic acid in human myotubes and interplay with glucose and fatty acid metabolism. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, R.; Philpott, M.P.; Kealey, T. Metabolism of Freshly Isolated Human Hair Follicles Capable of Hair Elongation: A Glutaminolytic, Aerobic Glycolytic Tissue. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1993, 100, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kierans, S.J.; Taylor, C.T. Regulation of glycolysis by the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF): Implications for cellular physiology. J. Physiol. 2021, 599, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Tang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, J.a.; Yang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Pu, W.; Liu, J.; Shi, X.; Ma, Y.; et al. Insights into male androgenetic alopecia using comparative transcriptome profiling: Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 and Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathways. Br. J. Dermatol. 2022, 187, 936–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philpott, M. Transcriptomic analysis identifies regulators of the Wnt signalling and hypoxia-inducible factor pathways as possible mediators of androgenetic alopecia. Br. J. Dermatol. 2022, 187, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Yan, L.; Kageyama, T.; Nanmo, A.; Chun, Y.-S. Hypoxia inducible factor-1a promotes trichogenic gene expression in human dermal papilla cells. Sci. Rep. 2023, in press. [CrossRef]

- Flores, A.; Schell, J.; Krall, A.S.; Jelinek, D.; Miranda, M.; Grigorian, M.; Braas, D.; White, A.C.; Zhou, J.L.; Graham, N.A.; et al. Lactate dehydrogenase activity drives hair follicle stem cell activation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuloaga, K.L.; Gonzales, R.J. Dihydrotestosterone attenuates hypoxia inducible factor-1α and cyclooxygenase-2 in cerebral arteries during hypoxia or hypoxia with glucose deprivation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011, 301, H1882–H1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, E.G.Y.; Lim, T.C.; Leong, M.F.; Liu, X.; Sia, Y.Y.; Leong, S.T.; Yan-Jiang, B.C.; Stoecklin, C.; Borhan, R.; Heilmann-Heimbach, S.; et al. Observations that suggest a contribution of altered dermal papilla mitochondrial function to androgenetic alopecia. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 31, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogacka, I.; Ukropcova, B.; McNeil, M.; Gimble, J.M.; Smith, S.R. Structural and functional consequences of mitochondrial biogenesis in human adipocytes in vitro. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 6650–6656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, E.S.; Lee, M.H.; Murphy, R.E.; Malloy, C.R. Pentose phosphate pathway activity parallels lipogenesis but not antioxidant processes in rat liver. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 314, E543–E551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.S.; Gupta, J. Polyol pathway and redox balance in diabetes. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 182, 106326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimori, K.; Ueno, T.; Nagata, N.; Kashiwagi, K.; Aritake, K.; Amano, F.; Urade, Y. (2010). Suppression of adipocyte differentiation by aldo-keto reductase 1B3 acting as prostaglandin F2α synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 8880–8886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondrakhina, I.N.; Verbenko, D.A.; Zatevalov, A.M.; Gatiatulina, E.R.; Nikonorov, A.A.; Deryabin, D.G.; Kubanov, A.A. A Cross-sectional Study of Plasma Trace Elements and Vitamins Content in Androgenetic Alopecia in Men. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2021, 199, 3232–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, S.; Salem, M.; Laughlin, M.R. Intracellular Mg2+ regulates ADP phosphorylation and adenine nucleotide synthesis in human erythrocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 1998, 274, E920–E927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-Bellosta, R. Dietary magnesium supplementation improves lifespan in a mouse model of progeria. EMBO Mol. Med. 2020, 12, e12423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizžner, T.L.n.; Lin, H.K.; Peehl, D.M.; Steckelbroeck, S.; Bauman, D.R.; Penning, T.M. Human Type 3 3α-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase (Aldo-Keto Reductase 1C2) and Androgen Metabolism in Prostate Cells. Endocrinology 2003, 144, 2922–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchaprateep, R.; Asawanonda, P. Insulin-like growth factor-1: Roles in androgenetic alopecia. Exp. Dermatol. 2014, 23, 216–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhič, M.; Vardjan, N.; Chowdhury, H.H.; Zorec, R.; Kreft, M. Insulin and Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1) Modulate Cytoplasmic Glucose and Glycogen Levels but Not Glucose Transport across the Membrane in Astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 11167–11176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlino, E.; Tommasi, S.; Moro, L.; Bellizzi, A.; Marra, E.; Casavola, V.; Reshkin, S.J. TGF-beta1 and IGF-1 expression are differently regulated by serum in metastatic and non-metastatic human breast cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2000, 16, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudramurthy, S.M.; Honnavar, P.; Dogra, S.; Yegneswaran, P.P.; Handa, S.; Chakrabarti, A. Association of Malassezia species with dandruff. Indian J. Med. Res. 2014, 139, 431–437. [Google Scholar]

- Piérard-Franchimont, C.; De Doncker, P.; Cauwenbergh, G.; Piérard, G.E. Ketoconazole Shampoo: Effect of Long-Term Use in Androgenic Alopecia. Dermatology 1998, 196, 474–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyravian, N.; Deo, S.; Daunert, S.; Jimenez, J.J. The Inflammatory Aspect of Male and Female Pattern Hair Loss. J. Inflamm. Res. 2020, 13, 879–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halley-Stott, R.P.; Adeola, H.A.; Khumalo, N.P. Destruction of the stem cell Niche, Pathogenesis and Promising Treatment Targets for Primary Scarring Alopecias. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2020, 16, 1105–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.G.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, S.R.; Pyo, H.K.; Moon, H.I.; Lee, J.H.; Kwon, O.S.; Chung, J.H.; Kim, K.H.; Eun, H.C.; et al. Perifollicular Fibrosis: Pathogenetic Role in Androgenetic Alopecia. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2006, 29, 1246–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuoka, K.; Mauch, C.; Schell, H.; Hornstein, O.P.; Krieg, T. Collagen-type synthesis in human-hair papilla cells in culture. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 1988, 280, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askew, E.B.; Gampe, R.T.; Stanley, T.B.; Faggart, J.L.; Wilson, E.M. Modulation of Androgen Receptor Activation Function 2 by Testosterone and Dihydrotestosterone. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 25801–25816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pleiner, J.; Mittermayer, F.; Schaller, G.; Marsik, C.; MacAllister, R.J.; Wolzt, M. Inflammation-induced vasoconstrictor hyporeactivity is caused by oxidative stress. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 42, 1656–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Freund, B.J.; Schwartz, M. Treatment of male pattern baldness with botulinum toxin: A pilot study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010, 126, 246e–248e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, R.S., Jr.; Barazesh, J.M. Self-Assessments of Standardized Scalp Massages for Androgenic Alopecia: Survey Results. Dermatol. Ther. 2019, 9, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoelzel, F. Baldness and calcification of the “Ivory Dome”. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1942, 119, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotta, N.; Kawamura, T.; Umemura, T. Are the polyol pathway and hyperuricemia partners in the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in diabetes? J. Diabetes Investig. 2020, 11, 786–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevisan, M.; Farinaro, E.; Krogh, V.; Jossa, F.; Giumetti, D.; Fusco, G.; Panico, S.; Mellone, C.; Frascatore, S.; Scottoni, A.; et al. Baldness and coronary heart disease risk factors. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1993, 46, P1213–P1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, C.K.; Tsai, J.C.; Soroceanu, L.; Gillespie, G.Y. Loss of vascular endothelial growth factor in human alopecia hair follicles. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1995, 104, 18s–20s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimna, A.; Kurpisz, M. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 in Physiological and Pathophysiological Angiogenesis: Applications and Therapies. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 549412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey-Rao, R.; Sinha, A.A. A genomic approach to susceptibility and pathogenesis leads to identifying potential novel therapeutic targets in androgenetic alopecia. Genomics 2017, 109, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire, M.; Larsen, M.C.; Vezina, C.M.; Quadro, L.; Kim, Y.-K.; Tanumihardjo, S.A.; Jefcoate, C.R. Cyp1b1 directs Srebp-mediated cholesterol and retinoid synthesis in perinatal liver; Association with retinoic acid activity during fetal development. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Tomisato, W.; Su, L.; Sun, L.; Choi, J.H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, K.-W.; Zhan, X.; Choi, M.; Li, X.; et al. Skin-specific regulation of SREBP processing and lipid biosynthesis by glycerol kinase 5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E5197–E5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, L.B.; Bergfeld, W.F.; Calogeras, E. The diagnosis and treatment of iron deficiency and its potential relationship to hair loss. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2006, 54, 824–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kil, M.S.; Kim, C.W.; Kim, S.S. Analysis of Serum Zinc and Copper Concentrations in Hair Loss. Ann. Dermatol. 2013, 25, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, P.; Kurutas, E.; Ataseven, A.; Dokur, N.; Gumusalan, Y.; Gorur, A.; Tamer, L.; Inaloz, S. BMI and levels of zinc, copper in hair, serum and urine of Turkish male patients with androgenetic alopecia. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2014, 28, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trüeb, R.M. The Difficult Hair Loss Patient: Guide to Successful Management of Alopecia and Related Conditions; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, L.; Reygagne, P.; Benech, P.; Jean-Louis, F.; Scalvino, S.; So, S.L.K.; Hamidou, Z.; Bianoici, S.; Pouch, J.; Ducos, B.; et al. Study of gene expression alteration in male androgenetic alopecia: Evidence of predominant molecular signalling pathways. Br. J. Dermatol. 2017, 177, 1322–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Q.; Zhu, X.; Manson, J.E.; Song, Y.; Li, X.; Franke, A.A.; Costello, R.B.; Rosanoff, A.; Nian, H.; Fan, L.; et al. Magnesium status and supplementation influence vitamin D status and metabolism: Results from a randomized trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 108, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickart, L. The human tri-peptide GHK and tissue remodeling. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2008, 19, 969–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickart, L.; Margolina, A. Regenerative and protective actions of the GHK-Cu peptide in the light of the new gene data. Int. J. Mol. Biosci. 2018, 19, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.; Shinozaki, S.; Shimokado, K. Sulforaphane promotes murine hair growth by accelerating the degradation of dihydrotestosterone. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 472, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Choi, K.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.; Park, G.; Kim, J. Sulforaphane, L-Menthol, and Dexpanthenol as a Novel Active Cosmetic Ingredient Composition for Relieving Hair Loss Symptoms. Cosmetics 2021, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattanand, A.; Johnson, W.C. Male Pattern Alopecia A Histopathologic and Histochemical Study. J. Cutan. Pathol. 1975, 2, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoi, K.; Nakayama, T. Glucuronidase deconjugation in inflammation. Methods Enzym. 2005, 400, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, Y. β-Glucuronidase activity and mitochondrial dysfunction: The sites where flavonoid glucuronides act as anti-inflammatory agents. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2014, 54, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, V.E. The Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Testosterone. J. Endocr. Soc. 2019, 3, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Yang, B.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, S.D.; Du, X.J.; Feng, X.L.; Yu, Z.; Xia, Y.T.; Yu, J.P. Clinical significance of TGF- beta1 and beta-glucuronidase synchronous detection in human pancreatic cancer. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2002, 1, 309–311. [Google Scholar]

- Itsumi, M.; Shiota, M.; Takeuchi, A.; Kashiwagi, E.; Inokuchi, J.; Tatsugami, K.; Kajioka, S.; Uchiumi, T.; Naito, S.; Eto, M.; et al. Equol inhibits prostate cancer growth through degradation of androgen receptor by S-phase kinase-associated protein 2. Cancer Sci. 2016, 107, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.; Steels, E.; Beccaria, G.; Inder, W.J.; Vitetta, L. Influence of a Specialized Trigonella foenum-graecum Seed Extract (Libifem), on Testosterone, Estradiol and Sexual Function in Healthy Menstruating Women, a Randomised Placebo Controlled Study. Phytother. Res. 2015, 29, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-López, C.; Soriguer, F.; Hernandez, C.; Rojo-Martinez, G.; Rubio-Martín, E.; Simó, R.; Selva, D.M. Oleic acid increases hepatic sex hormone binding globulin production in men. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, A.M.; Merz-Demlow, B.E.; Xu, X.; Phipps, W.R.; Kurzer, M.S. Premenopausal Equol Excretors Show Plasma Hormone Profiles Associated with Lowered Risk of Breast Cancer1. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2000, 9, 581–586. [Google Scholar]

- Leoncini, E.; Malaguti, M.; Angeloni, C.; Motori, E.; Fabbri, D.; Hrelia, S. Cruciferous Vegetable Phytochemical Sulforaphane Affects Phase II Enzyme Expression and Activity in Rat Cardiomyocytes through Modulation of Akt Signaling Pathway. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, H175–H181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.; Jia, F.-Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z.-H.; Jin, W.-Y.; Yang, J. Salidroside alleviates oxidative stress and apoptosis via AMPK/Nrf2 pathway in DHT-induced human granulosa cell line KGN. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2022, 715, 109094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Liu, P.; Tao, S.; Deng, Y.; Li, X.; Lan, T.; Zhang, X.; Guo, F.; Huang, W.; Chen, F.; et al. Berberine inhibits aldose reductase and oxidative stress in rat mesangial cells cultured under high glucose. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008, 475, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shevelev, A.B.; La Porta, N.; Isakova, E.P.; Martens, S.; Biryukova, Y.K.; Belous, A.S.; Sivokhin, D.A.; Trubnikova, E.V.; Zylkova, M.V.; Belyakova, A.V.; et al. In Vivo Antimicrobial and Wound-Healing Activity of Resveratrol, Dihydroquercetin, and Dihydromyricetin against Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Candida albicans. Pathogens 2020, 9, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetti, G.; D’Auria, F.D.; Mulinacci, N.; Innocenti, M.; Antonacci, D.; Angiolella, L.; Santamaria, A.R.; Valletta, A.; Donati, L.; Pasqua, G. Anti-Dermatophyte and Anti-Malassezia Activity of Extracts Rich in Polymeric Flavan-3-ols Obtained from Vitis vinifera Seeds. Phytother. Res. 2017, 31, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, P.; Barice, E.J.; Park, J.; Dyess, S.M.; McCaffrey, R.; Hennekens, C.H. Treatments for Inflammatory Arthritis: Potential But Unproven Role of Topical Copaiba. Integr. Med. 2017, 16, 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Pferschy-Wenzig, E.M.; Kunert, O.; Presser, A.; Bauer, R. In vitro anti-inflammatory activity of larch (Larix decidua L. ) sawdust. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 11688–11693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovac, I.; Melegova, N.; Coma, M.; Takac, P.; Kovacova, K.; Holly, M.; Durkac, J.; Urban, L.; Gurbalova, M.; Svajdlenka, E.; et al. Aesculus hippocastanum L. Extract Does Not Induce Fibroblast to Myofibroblast Conversion but Increases Extracellular Matrix Production In Vitro Leading to Increased Wound Tensile Strength in Rats. Molecules 2020, 25, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.; Padilla-Gonzalez, G.F.; Phumthum, M.; Simmonds, M.S.J.; Sadgrove, N.J. Comparative metabolomics of reproductive organs in the genus Aesculus (Sapindaceae) reveals that immature fruits are a key organ of procyanidin accumulation and bioactivity. Plants 2021, 10, 2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallelli, L. Escin: A review of its anti-edematous, anti-inflammatory, and venotonic properties. Drug Des. Develop. Ther. 2019, 13, 3425–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, M.; Manchandra, K.; Pandey, S.S. Role of caffeine in the management of androgenetic alopecia. Int. J. Trichol. 2012, 4, 185–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juhász, M.L.W.; Mesinkovska, N.A. The use of phosphodiesterase inhibitors for the treatment of alopecia. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2020, 31, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velickovic, K.; Wayne, D.; Leija, H.A.L.; Bloor, I.; Morris, D.E.; Law, J.; Budge, H.; Sacks, H.; Symonds, M.E. Caffeine exposure induces browning features in adipose tissue in vitro and in vivo. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojuka, E.O.; Jones, T.E.; Han, D.H.; Chen, M.; Holloszy, J.O. Raising Ca2+ in L6 myotubes mimics effects of exercise on mitochondrial biogenesis in muscle. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2003, 17, 675–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, E.J.; Lee, Y.M.; Lee, O.H.; Lee, M.J.; Lee, S.K.; Chung, M.H.; Park, Y.I.; Sung, C.K.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, K.W. A novel angiogenic factor derived from Aloe vera gel: Beta-sitosterol, a plant sterol. Angiogenesis 1999, 3, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorenson, W.R.; Sullivan, D. Determination of Campesterol, Stigmasterol, and beta-Sitosterol in Saw Palmetto RawMaterials and Dietary Supplements by Gas Chromatography: Single-Laboratory Validation. J. AOAC Int. 2019, 89, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, M.; Asai, M.; Moriya, T.; Sagara, M.; Inoué, S.; Shibata, S. Methylcobalamin amplifies melatonin-induced circadian phase shifts by facilitation of melatonin synthesis in the rat pineal gland. Brain Res. 1998, 795, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.W.; Trüeb, R.M.; Hänggi, G.; Innocenti, M.; Elsner, P. Topical melatonin for treatment of androgenetic alopecia. Int. J. Trichol. 2012, 4, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Maria, R.P. Hair Sustaining Formulation. U.S. Patent 8,580,236, 12 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman, C. Use a Plant Extract to Enhance Hair Growth and Hair Restoration for Damaged Hair. U.S. Patent 10/934,700, 10 March 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Karaca, N.; Akpolat, N.D. A Comparative Study between Topical 5% Minoxidil and Topical “Redensyl, Capixyl, and Procapil” Combination in Men with Androgenetic Alopecia. J. Cosmetol. Trichol. 2019, 5, 150370987. [Google Scholar]

- Givaudan. Redensyl® The Hair Growth Galvanizer Reactivates Hair Follicle Stem Cells for an Outstanding Hair Growth. Available online: https://agerahealth.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/TDS-Redensyl-04.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Liao, S.S.; Hiipakka, R.A. Selective-Inhibition of Steroid 5 α-Reductase Isozymes by Tea Epicatechin-3-Gallate and Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 214, 833–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batubara, I.; Kuspradini, H.; Mitsunaga, T. Anti-acne and Tyrosinase Inhibition Properties of Taxifolin and Some Flavanonol Rhamnosides from Kempas (Koompassia malaccensis). Wood Res. J. 2017, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, H.; Ohmi, I.; Fukuda, A.; Tamura, Y.; Mizutani, K.; Tanaka, O.; Chou, W.-H. Inhibition of Aldose Reductase and Sorbitol Accumulation by Astilbin and Taxifolin Dihydroflavonols in Engelhardtia chrysolepis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1997, 61, 651–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.B.; Bhalla, T.N.; Gupta, G.P.; Mitra, C.R.; Bhargava, K.P. Anti-inflammatory activity of taxifolin. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1971, 21, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muramatsu, D.; Uchiyama, H.; Kida, H.; Iwai, A. In vitro anti-inflammatory and anti-lipid accumulation properties of taxifolin-rich extract from the Japanese larch, Larix kaempferi. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, B.A.J.; Griffiths, K.; Morton, M.S. Inhibition of 5α-reductase in genital skin fibroblasts and prostate tissue by dietary lignans and isoflavonoids. J. Endocrinol. 1995, 147, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.-W.; Luo, D.; Chen, D.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, X.-C.; Yang, X.-L.; Wang, Y.-L.; Liu, W. Co-delivery of bioactive peptides by nanoliposomes for promotion of hair growth. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 72, 103381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, A.; Cristiano, M.C.; Cilurzo, F.; Locatelli, M.; Iannotta, D.; Di Marzio, L.; Celia, C.; Paolino, D. Ammonium glycyrrhizate skin delivery from ultradeformable liposomes: A novel use as an anti-inflammatory agent in topical drug delivery. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 193, 111152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huh, S.; Lee, J.; Jung, E.; Kim, S.-C.; Kang, J.-I.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y.-W.; Sung, Y.K.; Kang, H.-K.; Park, D. A cell-based system for screening hair growth-promoting agents. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2009, 301, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, S.-Y.; Jin, B.-R.; Kim, H.-J.; An, H.-J. Oleanolic Acid Ameliorates Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia by Regulating PCNA-Dependent Cell Cycle Progression In Vivo and In Vitro. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 1183–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.B.; Singh, S.; Bani, S.; Gupta, B.D.; Banerjee, S.K. Anti-inflammatory activity of oleanolic acid in rats and mice. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1992, 44, 456–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginwala, R.; Bhavsar, R.; Chigbu, D.G.I.; Jain, P.; Khan, Z.K. Potential Role of Flavonoids in Treating Chronic Inflammatory Diseases with a Special Focus on the Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Apigenin. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grothe, T.; Wandrey, F.; Schuerch, C. Short communication: Clinical evaluation of pea sprout extract in the treatment of hair loss. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 428–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, B.-S.; Yoon, J.-Y.; Kim, M.-Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Choi, T.; Choi, K.-Y. Bone morphogenetic protein 4 stimulates neuronal differentiation of neuronal stem cells through the ERK pathway. Exp. Mol. Med. 2009, 41, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turck, D.; Bresson, J.L.; Burlingame, B.; Dean, T.; Fairweather-Tait, S.; Heinonen, M.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; Naska, A.; et al. Scientific Opinion on taxifolin-rich extract from Dahurian Larch (Larix gmelinii). EFSA J. Eur. Food Saf. Auth. 2017, 15, e04682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alves, C.M.; de Almeida, A.P.; Polonini, C.H.; Bhering, A.P.C.; de Ferreira, A.O.; Brandao, A.F.M.; Raposo, R.B.N. Taxifolin: Evaluation through Ex vivo Permeations on Human Skin and Porcine Vaginal Mucosa. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2018, 15, 1123–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, S.; Tanaka, M.; Satoh-Asahara, N.; Carare, R.O.; Ihara, M. Taxifolin: A Potential Therapeutic Agent for Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 643357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type and Variations | Vernacular | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Alopecia areata, and phenotypic variations. | Patchy hair loss. Phenotypic variations include alopecia totalis, alopecia universalis, diffuse AA, and ophiasis AA. | This is characterized by either patchy, diffuse, or complete hair loss that is thought to relate to an autoimmune disorder that attacks the base of the follicle (the bulb). This does not have a distinct pattern; it can occur anywhere on the scalp or the body [7]. |

| Androgenetic alopecia (AGA) or female pattern hair loss. | Pattern hair loss, male pattern baldness, and hereditary baldness. | This is the most common cause of hair loss, characterized by hair miniaturization and inactivity triggered by over-expression of dihydrotestosterone in scalp tissue [8] and an orchestration of other factors [6]. Female pattern hair loss can be diagnosed in males. It is more diffuse than the male phenotype and tends to be concentrated on the vertex or mid-scalp, rather than the frontal region [9]. |

| Primary cicatricial alopecia. | Primary or general scarring alopecia. | This is a group of hair follicle disorders in which the bulge region is irreversibly destroyed, and follicles are replaced by fibrous tissue. Three subgroups include (1) the lymphocytic group (i.e., classic pseudopelade (Brocq), lichen planopilaris, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia [10], frontal fibrosing alopecia [11], and chronic discoid lupus erythematosus); (2) the neutrophilic group (i.e., dissecting cellulitis and follicular decalvans,); and (3) the lymphocytic/neutrophilic group (i.e., folliculitis keloidalis) [4,12,13]. |

| Secondary cicatricial alopecia. | Injury alopecia. | This involves irreversible destruction of the hair follicle by injuries, such as burns, deep skin infection, trauma, metastatic cancer, or radiation [14,15]. |

| Chemotherapy-induced alopecia. | Anagen effluvium. | Chemotherapy causes hair loss via P53-dependent apoptosis of hair-matrix keratinocytes. This is reinforced by the dystrophic anagen or dystrophic catagen pathway leading to chemotherapy-induced hair-cycle abnormalities [16]. |

| Chronic telogen effluvium. | Stress alopecia. | This occurs when chemical or mental stress causes hair to stop growing and stay at rest, then shed. It is commonly diffuse but can be restricted to specific regions that correlate to an area of a comorbidity, such as androgenetic alopecia. While generally characterized by a lack of miniaturized hairs, it often occurs as a comorbidity of androgenetic alopecia, both of which can be difficult to recognize or diagnose. Sometimes, the cause of telogen effluvium is not identified [17]. |

| Tinea capitis. | Fungal alopecia. | Characterized by patches of hair loss caused by a fungal infection wherein hair bulbs are sometimes inflamed severely, sometimes not, yet hairs are frequently broken rather than shed [18]. |

| Traction alopecia. | Injury alopecia. | Caused by strain against the hair follicles, typically via tight hairstyles. This causes terminal hairs to be replaced with vellus hairs, creating a marginal or non-marginal patchy phenotype that may involve the development of fibrotic tissue that replaces the capillary network if hair styling practices persist without intervention or treatment [19]. |

| Trichotillomania. | Hair pulling. | A psychosomatic disorder involving compulsive plucking of hairs from one’s scalp, eyelashes, or eyebrows often in relation to a psychological comorbidity, such as obsessive–compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [20]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sadgrove, N.; Batra, S.; Barreto, D.; Rapaport, J. An Updated Etiology of Hair Loss and the New Cosmeceutical Paradigm in Therapy: Clearing ‘the Big Eight Strikes’. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics10040106

Sadgrove N, Batra S, Barreto D, Rapaport J. An Updated Etiology of Hair Loss and the New Cosmeceutical Paradigm in Therapy: Clearing ‘the Big Eight Strikes’. Cosmetics. 2023; 10(4):106. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics10040106

Chicago/Turabian StyleSadgrove, Nicholas, Sanjay Batra, David Barreto, and Jeffrey Rapaport. 2023. "An Updated Etiology of Hair Loss and the New Cosmeceutical Paradigm in Therapy: Clearing ‘the Big Eight Strikes’" Cosmetics 10, no. 4: 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics10040106

APA StyleSadgrove, N., Batra, S., Barreto, D., & Rapaport, J. (2023). An Updated Etiology of Hair Loss and the New Cosmeceutical Paradigm in Therapy: Clearing ‘the Big Eight Strikes’. Cosmetics, 10(4), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics10040106