To Use or Not to Use: Impact of Personality on the Intention of Using Gamified Learning Environments

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Related Literature

2.1. Gamification and Technology Acceptance

2.2. Personality

2.3. Research Gap and the Purpose of This Study

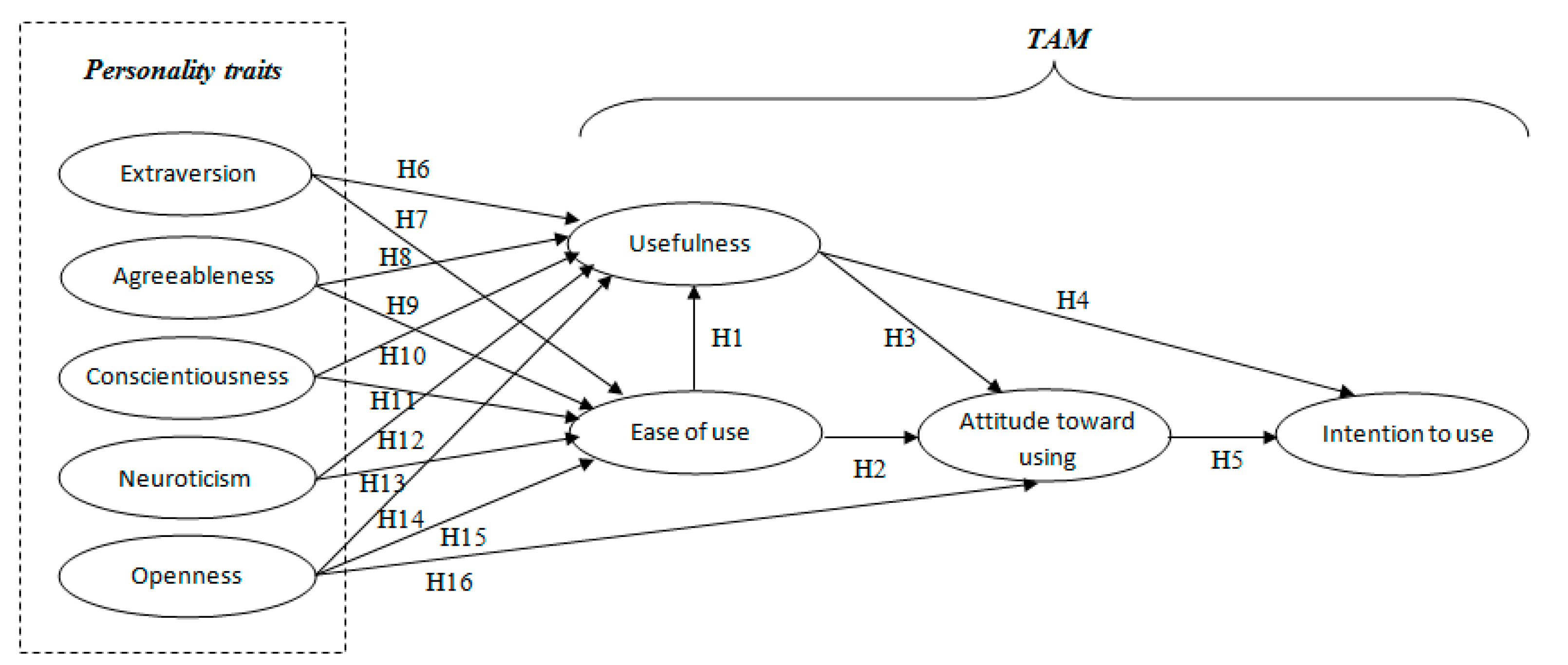

3. Research Model and Hypothesis

3.1. TAM

3.1.1. Perceived Ease of Use

3.1.2. Perceived Usefulness

3.1.3. Perceived Behavioral Attitudes toward Using a System

3.2. Personality

4. Method

4.1. Study Context

- 1.

- Points: Zichermann and Cunningham [69] recommended using different types of points based on students’ contributions to promote participation in the course. Therefore, each completed learning activity in the gamified course supported students with 50 experience points. They were also given 9 skill points for completing the teacher’s supplementary learning activities.

- 2.

- Levels: There were twenty levels in the course. According to Simões et al. [70], these levels should be sorted from easiest to hardest for reflecting the students’ newly acquired skills. Each week, students had the challenge of accumulating a set amount of points by completing a series of activities in order to advance to the next level. The intricacy of these weekly tasks was also taken into consideration when they were added (from the easiest to the hardest). For instance, in the first week, students were expected to graduate from level 1 to level 2. Each student had to score at least 120 points to do so. Virtual badges displaying the reached level number were used to present levels.

- 3.

- Badges: Enders and Kapp [71] recommended the use of badges only for meaningful achievements that demand some work to obtain. Therefore, in order to acquire a badge, students had to complete an assignment or quiz at the end of each level, which assessed their comprehension of all the content learned at that level. As indicated in Figure 2, several sorts of badges were used in the course depending on the completed activity. For instance, when students finished all the required assignments, they received a badge entitled “Problem solver”, which means that the student has solved all the problems related to the given assignments. In addition, the illustration of this badge, as shown in Figure 2, shows a picture of a lamp to refer to students’ ideas for solving the required assignments.

- 4.

- Avatar: Students had the freedom to upload personal avatars, which represented them within the gamified course, to make the course more enjoyable. Students were also given the freedom to create their own individualized avatars in order to increase their emotional attachment, which resulted in a higher degree of engagement [72]. The avatars chosen by the students were also shown on the leaderboard.

- 5.

- Leaderboard: Students’ ranks were shown on a leaderboard based on the points they had earned in the course. Its goal was to make students more competitive while learning. In addition, the leaderboard featured a real-time update system for students’ ranks (i.e., if a student earned more points, his or her place on the leaderboard was updated automatically in real time). As a result, students were able to see themselves on the board, which gave them the feeling that they had a chance to win [73]. The student with the highest position on the leaderboard at the end of the semester was announced as the course winner. Figure 3 presents the leaderboard of the OODM course, displaying students’ avatars, levels, progress in this level and collected points.

- 6.

- Feedback: Every week, students received amusing feedback from their teacher via Moodle, including photos and texts, to ensure their psychological well-being and inspire them to study more [74]. The teacher wrote the evaluation based on each student’s performance during the course (e.g., according to the accumulated points or badges).

- 7.

- Progress bar: Students should be able to clearly see their growth toward the course goal in order for a course to be meaningful to them [75]. As a result, a colored progress bar was created, to which weekly activities were added. In the progress bar, an unfinished activity was colored blue, while a completed activity was colored yellow, as seen in Figure 4. When feedback was received on an activity, it was colored green. This provided students with a sense of progression throughout the course.

- 8.

- Chat: Students could use immediate discussion to collaborate with their friends or to assist them if they had any questions. Furthermore, as recommended by Hou and Wu [76], in order to encourage students to complete the required goals in teams, they received several points once they had completed them.

4.2. Research Participants and Procedures

4.3. Measurement

4.3.1. Independent Variable: Big Five Inventory (BFI)

4.3.2. Dependent Variable: Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)

4.4. Validity and Reliability

5. Results

5.1. TAM

5.2. Personality

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions, Implications and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deterding, S.; Sicart, M.; Nacke, L.; O’Hara, K.; Dixon, D. Gamification: Using game-design elements in non-gaming contexts. In Proceedings of the CHI 2011, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–12 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kopcha, T.J.; Ding, L.; Neumann, K.L.; Choi, I. Teaching Technology Integration to K-12 Educators: A ‘Gamified’ Approach. TechTrends 2016, 60, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, P.; Doyle, E. Individualising gamification: An investigation of the impact of learning styles and personality traits on the efficacy of gamification using a prediction market. Comput. Educ. 2017, 106, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallifax, S.; Lavoué, E.; Serna, A. To Tailor or Not to Tailor Gamification? An Analysis of the Impact of Tailored Game Ele-ments on Learners’ Behaviours and Motivation. In Artificial Intelligence in Education, 2nd ed.; Bittencourt, I., Cukurova, M., Muldner, K., Luckin, R., Millán, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12163, pp. 216–227. [Google Scholar]

- Mekler, E.D.; Brühlmann, F.; Tuch, A.N.; Opwis, K. Towards understanding the effects of individual gamification elements on intrinsic motivation and performance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 71, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almiawi, M.W.E.; Adaletey, E.J.; Phung, S.P. Impact of Gamification on Higher Education; A Case Study on Lim-kokwing University of Creative Technology Campus in Cyberjaya, Malaysia. TEST Eng. Manag. 2020, 83, 16337–16346. [Google Scholar]

- Ab Rahman, R.; Ahmad, S.; Hashim, U.R. Ab Rahman, R.; Ahmad, S.; Hashim, U.R. A Study on Gamification for Higher Education Students’ Engagement Towards Education 4.0. In Intelligent and Interactive Computing, 2nd ed.; Piuri, V., Balas, V., Borah, S., Syed Ahmad, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 67, pp. 491–502. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, F.R.H.; Mizoguchi, R.; Isotani, S. The bright and dark sides of gamification. In Intelligent Tutoring Systems, 2nd ed.; Micarelli, A., Stamper, J., Panourgia, K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 9684, pp. 176–186. [Google Scholar]

- Toda, A.M.; Valle, P.H.; Isotani, S. The dark side of gamification: An overview of negative effects of gamification in education. In Higher Education for All. From Challenges to Novel Technology-Enhanced Solutions, 2nd ed.; Cristea, A., Bit-tencourt, I., Lima, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 832, pp. 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Mekler, E.D.; Brühlmann, F.; Opwis, K.; Tuch, A.N. Do points, levels and leaderboards harm intrinsic motivation? An empirical analysis of common gamification elements. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Gameful Design, Research, and Applications, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2–4 October 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mert, Y.; Samur, Y. Students’ Opinions Toward Game Elements Used in Gamification Application. Turk. Online J. Qual. Inq. 2018, 9, 70–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kapp, K.M. The Gamification of Learning and Instruction: Game-Based Methods and Strategies for Training and Education; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Werbach, K.; Hunter, D. For the Win: How Game Thinking Can Revolutionize Your Business; Wharton Digital Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, R.A.; Ahmad, S.; Hashim, U.R. The effectiveness of gamification technique for higher education students engagement in polytechnic Muadzam Shah Pahang, Malaysia. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2018, 15, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Panagiotarou, A.; Stamatiou, Y.C.; Pierrakeas, C.J.; Kameas, A. Gamification Acceptance for Learners with Different E-Skills. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2020, 19, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nayanajith, G.; Damunupola, K.A.; Ventayen, R.J. Impact of innovation and perceived ease of use on e-learning adoption. Asian J. Bus. Technol. Stud. 2019, 2, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Tlili, A.; Zhu, L.; Yang, J. Do Playfulness and University Support Facilitate the Adoption of Online Education in a Crisis? COVID-19 as a Case Study Based on the Technology Acceptance Model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindermann, C.; Riedl, R.; Montag, C. Investigating the Relationship between Personality and Technology Acceptance with a Focus on the Smartphone from a Gender Perspective: Results of an Exploratory Survey Study. Future Internet 2020, 12, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, G.B.; Johnsen, J.-A.K.; Almås-Sørensen, L.; Vittersø, J. Personality and technology acceptance: The influence of personality factors on the core constructs of the Technology Acceptance Model. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2013, 32, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouakket, S.; Sun, Y. Investigating the Impact of Personality Traits of Social Network Sites Users on Information Disclosure in China: The Moderating Role of Gender. Inf. Syst. Front. 2019, 22, 1305–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harb, Y.; Alhayajneh, S. Intention to use BI tools: Integrating technology acceptance model (TAM) and personality trait model. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Electrical Engineering and Information Technology, Amman, Jordan, 9–11 April 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punnoose, A.C. Determinants of Intention to Use eLearning Based on the Technology Acceptance Model. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2012, 11, 301–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nov, O.; Ye, C. Personality and Technology Acceptance: Personal Innovativeness in IT, Openness and Resistance to Change. In Proceedings of the HICSS, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 7–10 January 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, C.E. Big Five Personality Traits: The OCEAN Model Explained. Available online: https://positivepsychologyprogram.com/big-five-personality-theory/ (accessed on 7 November 2020).

- DeYoung, C.G.; Quilty, L.C.; Peterson, J.B. Between facets and domains: 10 aspects of the Big Five. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 93, 880–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, M.C. Individual Differences and Personality; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Spanellis, A.; Dörfler, V.; MacBryde, J. Investigating the potential for using gamification to empower knowledge workers. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 160, 113694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denden, M.; Tlili, A.; Essalmi, F.; Jemni, M. Students’ learning performance in a gamified and self-determined learning environment. In Proceedings of the OCTA, Tunis, Tunisia, 6–8 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, D. Reflection: Benefits of gamification in online higher education. J. Instr. Res. 2018, 7, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Zeshan, F.; Khan, M.S.; Marriam, R.; Ali, A.; Samreen, A. The Impact of Gamification on Learning Outcomes of Computer Science Majors. ACM Trans. Comput. Educ. 2020, 20, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakıroğlu, Ü.; Başıbüyük, B.; Güler, M.; Atabay, M.; Memiş, B.Y. Gamifying an ICT course: Influences on engagement and academic performance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J. Do badges increase user activity? A field experiment on the effects of gamification. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 71, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collan, M. Lazy User Behavior; MPRA Paper: Munich, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Behl, A.; Jayawardena, N.; Ishizaka, A.; Gupta, M.; Shankar, A. Gamification and gigification: A multidimensional theoretical approach. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 139, 1378–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varannai, I.; Sasvári, P.L.; Urbanovics, A. The use of gamification in higher education: An empirical study. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2017, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferianda, M.R.; Herdiani, A.; Sardi, I.L. Increasing Students Interaction in Distance Education Using Gamification. In Proceedings of the ICoICT, Bandung, Indonesia, 3–5 May 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maican, C.I.; Cazan, A.-M.; Lixandroiu, R.C.; Dovleac, L. A study on academic staff personality and technology acceptance: The case of communication and collaboration applications. Comput. Educ. 2018, 128, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwajana, D.; Vanduhe, V.; Idowu, A.; Cemal Nat, M.; Fadiya, S. The Adoption of Students’ Hedonic Motivation System Model to Gamified Learning Environment. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2019, 17, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vanduhe, V.Z.; Nat, M.; Hasan, H.F. Continuance intentions to use gamification for training in higher education: Integrating the technology acceptance model (TAM), social motivation, and task technology fit (TTF). IEEE Access 2020, 8, 21473–21484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucier, G.; Srivastava, S. What makes a good structural model of personality? Evaluating the big five and alternatives. In Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- John, O.P.; Srivastava, S. The Big-Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, 2nd ed.; Pervin, L.A., John, O.P., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 2, pp. 102–138. [Google Scholar]

- Tlili, A.; Essalmi, F.; Jemni, M. Metric-Based Approach for Selecting the Game Genre to Model Personality. In State-of-the-Art and Future Directions of Smart Learning; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlili, A.; Denden, M.; Essalmi, F.; Jemni, M.; Huang, R.; Chang, T.-W. Personality Effects on Students’ Intrinsic Motivation in a Gamified Learning Environment. In Proceedings of the ICALT, Maceio, Brazil, 15–18 July 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denden, M.; Tlili, A.; Essalmi, F.; Jemni, M.; Chen, N.S.; Burgos, D. Effects of gender and personality differences on students’ perception of game design elements in educational gamification. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2021, 154, 102674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codish, D.; Ravid, G. Personality based gamification: How different personalities perceive gamification. In ECIS; The Open University of Israel: Ra’anana, Israel, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bayne, R. Psychological Types at Work: An MBTI Perspective: Psychology@Work Series; International Thomson Business: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.; Chen, X. Continuance intention to use MOOCs: Integrating the technology acceptance model (TAM) and task technology fit (TTF) model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 67, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Zhang, C. Empirical study on continuance intentions towards E-Learning 2.0 systems. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2014, 33, 1027–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, R.-T.; Hsiao, C.-H.; Tang, T.-W.; Lien, T.-C. Exploring the moderating role of perceived flexibility advantages in mobile learning continuance intention (MLCI). Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2014, 15, 140–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.; Zhou, M. Explaining the intention to use technology among university students: A structural equation modeling approach. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2014, 26, 124–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaraj, S.; Easley, R.F.; Crant, J.M. Research Note—How Does Personality Matter? Relating the Five-Factor Model to Technology Acceptance and Use. Inf. Syst. Res. 2008, 19, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczuch, R.; Lemmink, J.; Streukens, S. The effect of service employees’ technology readiness on technology acceptance. Inf. Manag. 2007, 44, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouakket, S. The role of personality traits in motivating users’ continuance intention towards Facebook: Gender differences. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2018, 29, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, J.C.; Hendrickson, A.; Townsend, A.M.; DeMarie, S.M. Dispositional Factors in Internet Use: Personality versus Cognitive Style. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T. Conceptions and Correlates of Openness to Experience. In Handbook of Personality Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997; pp. 825–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittaranjan, G.; Blom, J.; Gatica-Perez, D. Who’s who with big-five: Analyzing and classifying personality traits with smartphones. In Proceedings of the ISWC, San Francisco, CA, USA, 12–15 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lombriser, P.; Dalpiaz, F.; Lucassen, G.; Brinkkemper, S. Gamified Requirements Engineering: Model and Experimentation; Springer Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sailer, M.; Hense, J.U.; Mayr, S.K.; Mandl, H. How gamification motivates: An experimental study of the effects of specific game design elements on psychological need satisfaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A.K.; Rigby, C.S.; Ryan, R.M. A Motivational Model of Video Game Engagement. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2010, 14, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rigby, C.S.; Ryan, R.M. Glued to Games: How Video Games Draw Us in and Hold Us Spellbound; Praeger: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M. On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. J. Psychother. Integr. 2013, 23, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Williams, G.C.; Resnicow, K. Toward systematic integration between self-determination theory and motivational interviewing as examples of top-down and bottom-up intervention development: Autonomy or volition as a fundamental theoretical principle. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Deci, E.L.; Vansteenkiste, M. Self-determination theory and basic need satisfaction: Understanding human development in positive psychology. Ric. Psicol. 2004, 27, 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Marczewski, A. Gamification: A Simple Introduction; Amazon Digital Services, Inc.: Seattle, WA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zichermann, G.; Cunningham, C. Gamification by Design: Implementing Game Mechanics in Web and Mobile Apps; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Simões, J.; Redondo, R.D.; Vilas, A.F. A social gamification framework for a K-6 learning platform. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 29, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, B.; Kapp, K. Gamification, Games, and Learning: What Managers and Practitioners Need to Know; The eLearning Guild: Santa Rosa, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, R.A.; Guadagno, R.E. My avatar and me—Gender and personality predictors of avatar-self discrepancy. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaswad, Z.; Nadolny, L. Designing for Game-Based Learning: The Effective Integration of Technology to Support Learning. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2015, 43, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Donovan, S. Gamification of the games course. Acessoem 2012, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, H.T.; Wu, S.Y. Analyzing the social knowledge construction behavioral patterns of an online synchronous collaborative discussion instructional activity using an instant messaging tool: A case study. Comput. Educ. 2011, 57, 1459–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatarain Cabada, R.; Barrón Estrada, M.L.; Ríos Félix, J.M.; Alor Hernández, G. A virtual environment for learning computer coding using gamification and emotion recognition. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 28, 1048–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T. Modelling technology acceptance in education: A study of pre-service teachers. Comput. Educ. 2009, 52, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Newsted, P.R. Structural equation modeling analysis with small samples using partial least squares. In Statistical Strategies for Small Sample Research, 2nd ed.; Hoyle, R., Ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 307–341. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Straub, D.W. Editor’s Comments: A Critical Look at the Use of PLS-SEM in “MIS Quarterly”. MIS Q. 2012, 36, Iii–xiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, C.-S.; Huang, Y.-M.; Hsu, K.-S. Developing a mobile game to support students in learning color mixing in design education. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2017, 9, 1687814016685226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dezdar, S. Green information technology adoption: Influencing factors and extension of theory of planned behavior. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, P.A.; Kluemper, D.H. The impact of the big five personality traits on the acceptance of social networking website. In Proceedings of the AMCIS, Toronto, ON, Canada, 14–17 August 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, I. Personality and ICT Adoption: The call for more research. In Gender Gaps and the Social Inclusion Movement in ICT; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 104–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denden, M.; Tlili, A.; Essalmi, F.; Jemni, M. Implicit modeling of learners’ personalities in a game-based learning environment using their gaming behaviors. Smart Learn. Environ. 2018, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Psychological Needs | Game Design Elements | Matching Psychological Needs to Game Design Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Competence | Points: a numerical presentation of students’ performance. | Element that shows students’ performance. |

| Badges: a sort of virtual rewards. | Element that shows students’ performance. | |

| Leaderboard: shows the ranking of each student against other students. | Element that shows students’ expertise. | |

| Progress bar: shows students’ progress in a given course. | Element that shows students’ progression. | |

| Feedback: teachers’ feedback. | Element that shows students’ performance | |

| Levels: the level achieved by each student in a given course. | Element that shows students’ expertise. | |

| Autonomy | Avatar: a visual representation of the student. | Students have the freedom to choose the photo/avatar that better represent them in the gamified course. |

| Badges: a sort of virtual rewards. | Students can display or hide their awarded badges on their profiles. | |

| Social relatedness | Chat: instantaneous discussion. | Students have the possibility to interact and work together to complete a given task. |

| Characteristics | Sample | |

|---|---|---|

| Count | % | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 16 | 28.57 |

| Female | 40 | 71.42 |

| Age Group | ||

| 18–25 | 56 | 100 |

| 26–29 | 0 | 0 |

| 30–35 | 0 | 0 |

| Constructs | Items | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usefulness | 3 | 0.72 | 0.85 | 0.75 |

| Ease of use | 3 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.80 |

| Attitude toward using | 4 | 0.71 | 0.77 | 0.53 |

| Intention to use | 4 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.79 |

| Extraversion | 8 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.89 |

| Agreeableness | 9 | 0.82 | 0.89 | 0.76 |

| Conscientiousness | 9 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.79 |

| Neuroticism | 8 | 0.78 | 0.88 | 0.75 |

| Openness | 10 | 0.86 | 0.93 | 0.79 |

| Constructs | Use | EU | ATT | INT | Extra | Agre | Cons | Neuro | Open |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use | 0.86 | ||||||||

| EU | 0.08 | 0.79 | |||||||

| ATT | 0.58 | 0.14 | 0.72 | ||||||

| INT | 0.21 | −0.16 | 0.48 | 0.77 | |||||

| Extra | −0.12 | 0.23 | −0.19 | −0.27 | 0.80 | ||||

| Agre | 0.11 | 0.02 | −0.13 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.82 | |||

| Consc | 0.10 | −0.09 | −0.06 | −0.21 | 0.24 | 0.54 | 0.80 | ||

| Neuro | −0.28 | 0.11 | −0.05 | −0.14 | −0.07 | −0.44 | −0.46 | 0.81 | |

| Open | −0.24 | −0.04 | −0.28 | −0.38 | 0.36 | 0.15 | 0.24 | −0.14 | 0.87 |

| Hypothesis | Path Coefficients | p Value | Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Ease of use → Usefulness | 0.134 | p > 0.05 | No |

| H2: Ease of use → Attitude toward using | 0.091 | p > 0.05 | No |

| H3: Usefulness → Attitude toward using | 0.546 | p < 0.001 *** | Yes |

| H4: Usefulness → Intention to use | 0.111 | p < 0.01 ** | Yes |

| H5: Attitude toward using → Intention to use | 0.551 | p < 0.001 *** | Yes |

| H6: Extraversion → Usefulness | −0.106 | p > 0.05 | No |

| H7: Extraversion → Ease of use | 0.301 | p < 0.05 * | Yes |

| H8: Agreeableness → Usefulness | −0.002 | p > 0.05 | No |

| H9: Agreeableness → Ease of use | 0.088 | p > 0.05 | No |

| H10: Conscientiousness → Usefulness | 0.057 | p > 0.05 | No |

| H11: Conscientiousness → Ease of use | −0.144 | p > 0.05 | No |

| H12: Neuroticism → Usefulness | −0.317 | p < 0.05 * | Yes |

| H13: Neuroticism → Ease of use | 0.087 | p > 0.05 | No |

| H14: Openness → Usefulness | −0.257 | p > 0.05 | No |

| H15: Openness → Ease of use | −0.120 | p > 0.05 | No |

| H16: Openness → Attitude toward using | 0.144 | p < 0.05 * | Yes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Denden, M.; Tlili, A.; Abed, M.; Bozkurt, A.; Huang, R.; Burgos, D. To Use or Not to Use: Impact of Personality on the Intention of Using Gamified Learning Environments. Electronics 2022, 11, 1907. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11121907

Denden M, Tlili A, Abed M, Bozkurt A, Huang R, Burgos D. To Use or Not to Use: Impact of Personality on the Intention of Using Gamified Learning Environments. Electronics. 2022; 11(12):1907. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11121907

Chicago/Turabian StyleDenden, Mouna, Ahmed Tlili, Mourad Abed, Aras Bozkurt, Ronghuai Huang, and Daniel Burgos. 2022. "To Use or Not to Use: Impact of Personality on the Intention of Using Gamified Learning Environments" Electronics 11, no. 12: 1907. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11121907

APA StyleDenden, M., Tlili, A., Abed, M., Bozkurt, A., Huang, R., & Burgos, D. (2022). To Use or Not to Use: Impact of Personality on the Intention of Using Gamified Learning Environments. Electronics, 11(12), 1907. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11121907