Abstract

Software bugs are a noteworthy concern for developers and maintainers. When a failure is detected late, it costs more to be fixed. To repair the bug that caused the software failure, the location of the bug must first be known. The process of finding the defective source code elements that led to the failure of the software is called bug localization. Effective approaches for automatically locating bugs using bug reports are highly desirable, as they would reduce bug-fixing time, consequently lowering software maintenance costs. With the increasing size and complexity of software projects, manual bug localization methods have become complex, challenging, and time-consuming tasks, which motivates research on automated bug localization techniques. This paper introduces a novel bug localization model, which works on two levels. The first level localizes the buggy classes using an information retrieval approach and it has two additional sub-phases, namely the class-level feature scoring phase and the class-level final score and ranking phase, which ranks the top buggy classes. The second level localizes the buggy methods inside these classes using an information retrieval approach and it has two sub-phases, which are the method-level feature scoring phase and the method-level final score and ranking phase, which ranks the top buggy methods inside the localized classes. A model is evaluated using an AspectJ dataset, and it can correctly localize and rank more than 350 classes and more than 136 methods. The evaluation results show that the proposed model outperforms several state-of-the-art approaches in terms of the mean reciprocal rank (MRR) metrics and the mean average precision (MAP) in class-level bug localization.

1. Introduction

A software bug can be defined as an incorrect step, data definition, or process in a computer program that causes the program to produce incorrect results [1]. When a bug is discovered in a software system, it is reported using the bug report to the bug tracking system. Consequently, developers work to validate, locate, and fix the reported bug [2]. Usually, the developer who is working to solve the problem in the bug report needs to reproduce the bug [2] to find the cause. Nevertheless, the poor quality and multiformity of bug reports make this process a time-consuming task [3].

The number of these bug reports is high, and their size is increasing [4], which makes it difficult for developers to inspect them manually. Moreover, the process of investigating all source code files to indicate the faulty file is a tedious and time-consuming task [5], and this process can be the most expensive activity during the maintenance phase. Therefore, researchers are working on automating this process by introducing bug localization techniques. The automatic bug localization process ranks the potential source files with respect to their probability of having a bug, which decreases the scope of the search in the source files that need to be inspected by a developer [4].

The bug localization tool generally takes the bug report as input and outputs the possible source code files that are related to the given bug report [6].

In information-retrieval-based approaches, a bug report is treated as a query and the source code files are treated as a collection of documents making up a corpus; then, the task of localizing and ranking source files that are related to the bug report can be treated as a basic information retrieval task [7,8]. Gharabi et al. [4] proposed an information-retrieval-based approach for fault localization. Their muti-component approach influenced the relationship between the new bug reports and the bug reports that had been fixed previously, in addition to different textual properties of source files and bug reports. Their approach utilized textual matching, analysis of stack traces, information retrieval, and multilabel classification to increase bug localization performance. An evaluation of their results found that their model can localize relevant source files for more than 52% and 78% of bugs in the top 1 and top 10, respectively.

Many existing studies automate bug localization using different algorithms to localize faulty files in a software project. However, there is a lack of bug localization approaches that localize buggy classes and buggy methods inside these classes. Therefore, this study aims to provide a solution to improve the maintenance phase by using information retrieval (IR) and natural language processing (NLP) algorithms to provide a novel bug localization technique that works on two levels, automatically localizing the buggy class at the first level and the buggy method at the second level. Once the location of the bug has been identified, the maintenance phase is accelerated, and the developers can work on fixing the reported bug.

The primary contributions of this paper are outlined below:

- A two-level information-retrieval-based model for bug localization based on bug reports is proposed.

- A new approach for class-level bug localization at the first level of the proposed model is presented.

- A new approach for method-level bug localization at the second level of the proposed model is presented.

- The proposed model is evaluated by using a publicly available dataset for the class level and the method level.

- The proposed model is compared against several state-of-the-art class-level bug localization models, which proves that the proposed model outperforms these state-of-the-art models.

The structure of the rest of the paper is outlined as follows: Section 2 outlines the proposed model; the experimental study is illustrated in Section 3; Section 4 shows the results of the experiments and their analysis; Section 5 discusses the existing studies in the literature that focus on bug localization algorithms; and in Section 6, the conclusions and future work are outlined.

2. The Proposed Two-Level IR-Based Bug Localization Model

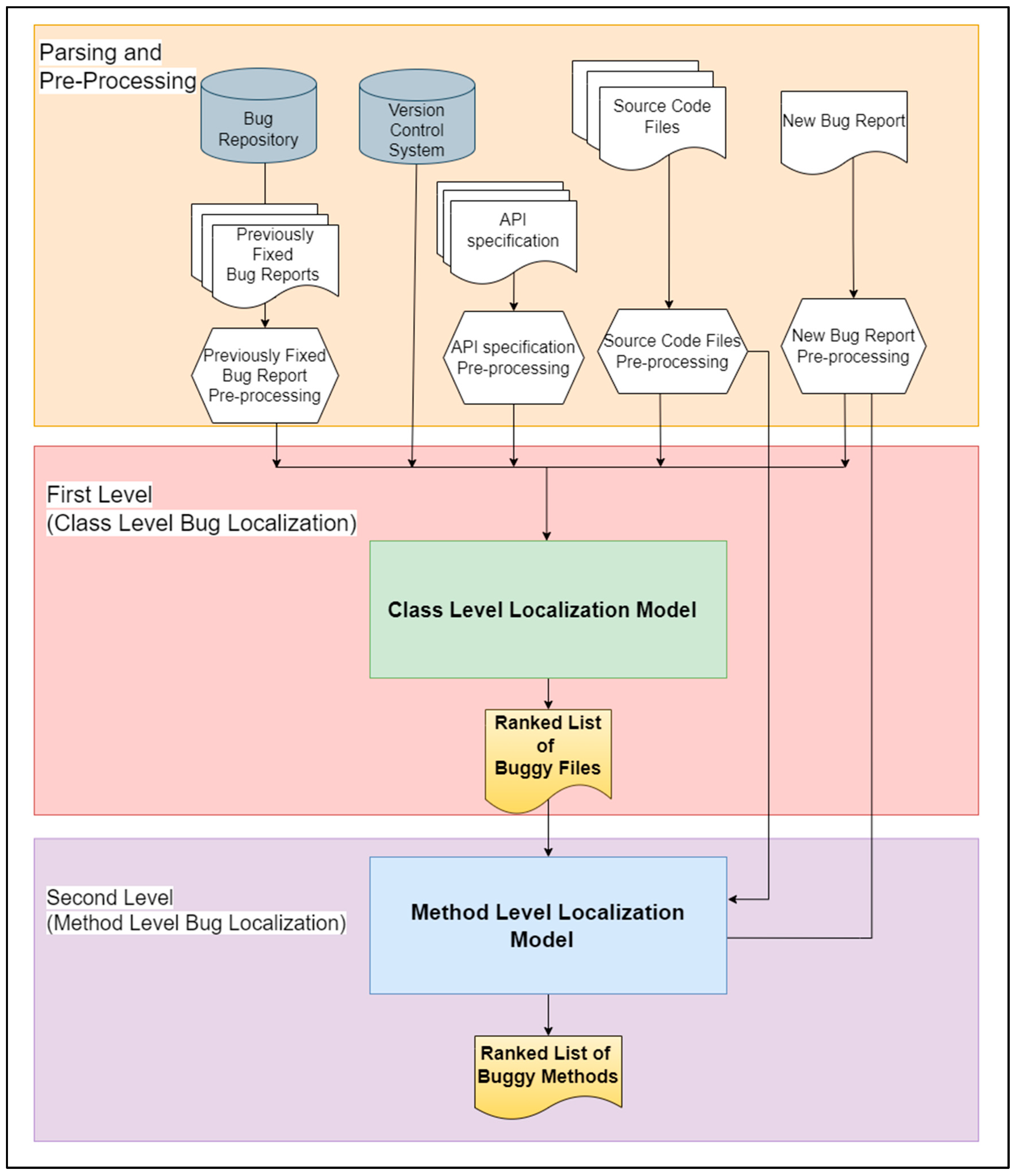

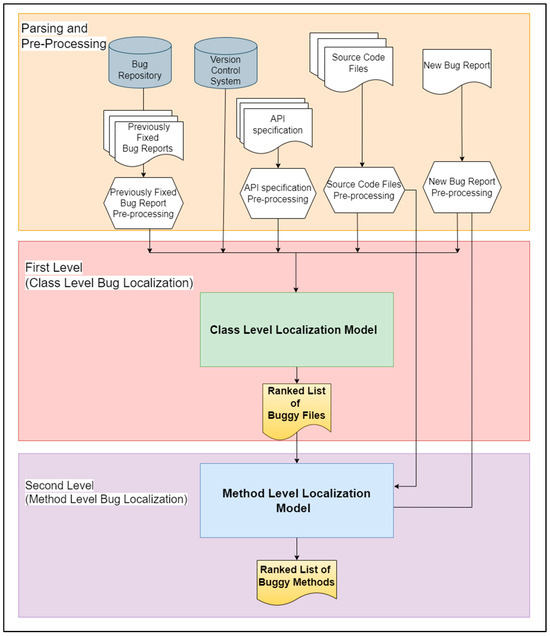

This section provides an overview of the suggested bug localization model that is used to localize buggy classes and methods with respect to a bug reported in a bug report. The proposed model consists of two main levels; the first level localizes and ranks the buggy classes and the second level localizes and ranks the buggy methods inside each localized class. The architecture of our model is presented in Figure 1. As depicted in this figure, the model has three phases. The first phase is the parsing and pre-processing phase, the second phase is class-level bug localization, and the third phase is method-level bug localization. Each phase is illustrated in the next sub-sections.

Figure 1.

Overall architecture of the proposed two-level bug localization model.

2.1. Parsing and Pre-Processing

In this phase, as an information-retrieval-based model, the bug report and the source files need to be parsed and pre-processed before they can be analyzed via the proposed model. This phase takes as input the bug report whose bug we aim to localize from the source code project, the source code files of the software repository that we aim to inspect, the specifications of the APIs of the classes and interfaces in the source files, the previous bug reports of the project, and the history of changes to the source files in the previous releases of the project. Additionally, this phase extracts the necessary elements from the bug reports, source files, and API specifications and removes unnecessary elements from them. From the bug report, the summary, description, and reporting date are extracted. From the source code files, the file names, class names, method names, attributes, comments, and variables are extracted.

In the pre-processing stage, many natural language processing approaches are applied to parsed elements of the bug report and source files to prepare them for the next steps. In more detail, the following steps are carried out in this phase:

- Stack trace extraction from the description of the bug report is performed. To extract the stack frames from the description of the bug report and distinguish them from the other parts of the description, a regular expression is used to apply the stack trace extraction process, which is in the form of ‘at package_name.class_name.method_name (file_name.java:line_number | Native Method | Unknown Source)’, which is found in the description of the bug report where the package, class, and method names that were being executed when the bug has been reported are found at package_name, class_name, and method_name, respectively [4].

- Then, a part of speech (POS) tagger is used to extract the verbs and nouns and the extracted elements are tokenized.

- Additionally, elements are normalized according to their type; for example, source files contain Camle Case identifiers and they are split into separate tokens; for example, “getAbsolutePath” is split into “get”, “Absolute”, and “Path”. Both splitting camel case tokens and the full identifier name are kept because it is shown that this approach is effective as the full identifier is often present in the bug report [9].

- Furthermore, unwanted tokens are removed such as programming language keywords, stop words, and punctuation.

- Finally, tokens are stemmed and converted into their root words.

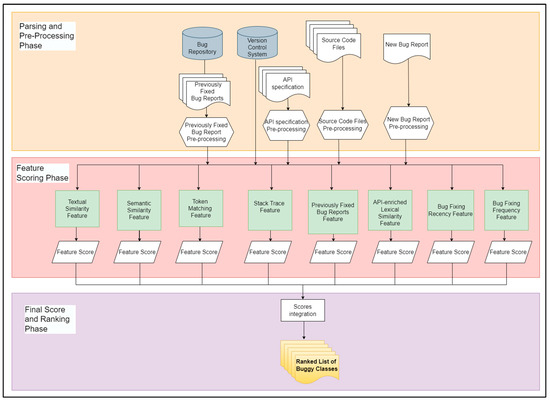

2.2. The Proposed Class-Level Bug Localization Approach

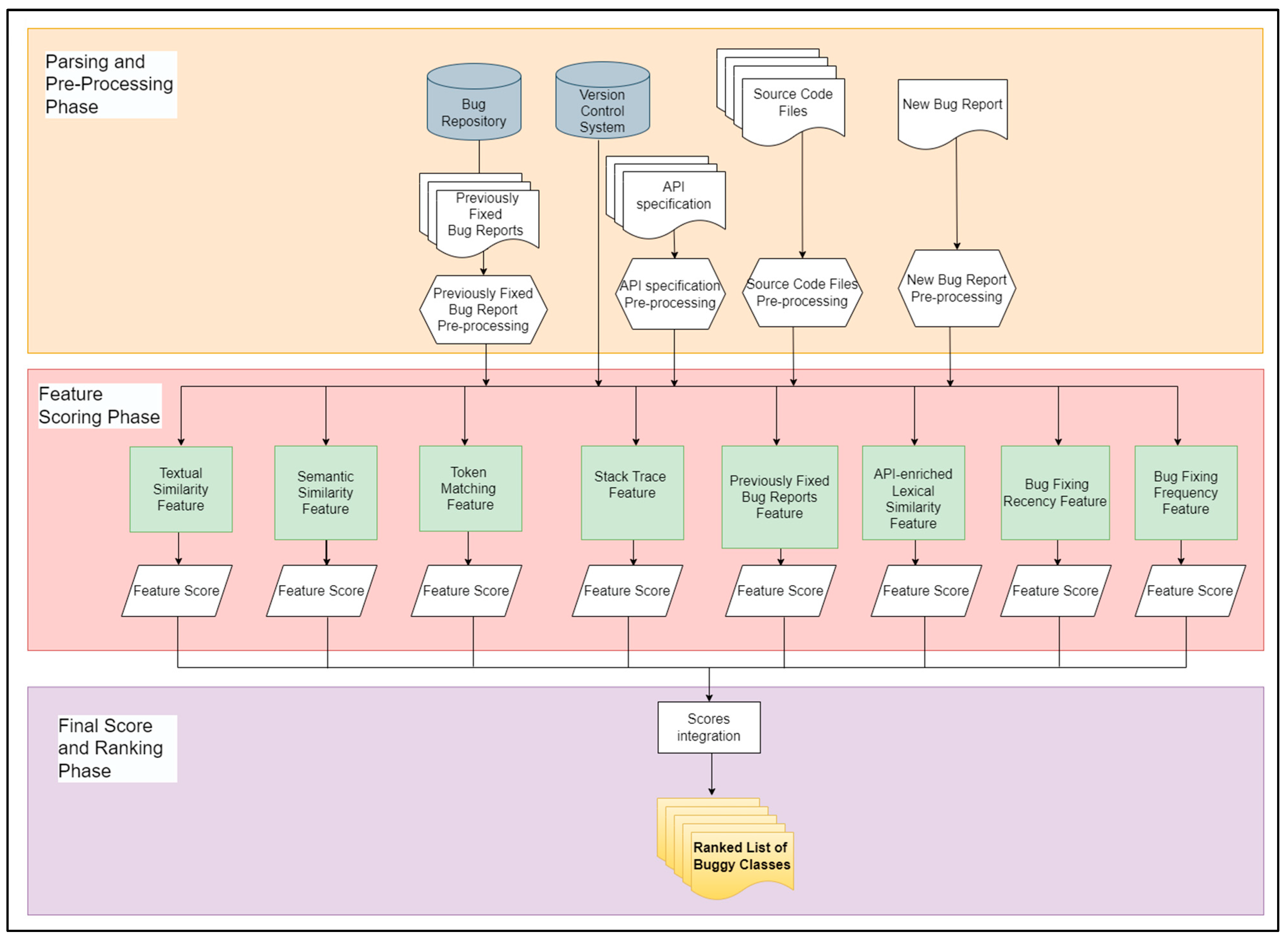

In this phase, the pre-processed source files and the bug report are used to conduct class-level bug localization. This phase has two additional sub-phases, which are the class-level feature scoring phase and the class-level final score and ranking phase.

In the class-level feature scoring phase, eight features are applied to each source file in the project repository with respect to the input bug report and each feature produces a score. In the class-level final score and ranking phase, the resultant scores of the previous step are normalized and integrated and the final integrated scores are ranked in which the source file with the highest score has the highest probability to include the reported bug in the bug report. The next sub-sections illustrate details for each phase. Figure 2 presents the architecture of the class-level bug localization algorithm.

Figure 2.

The first-level architecture of the proposed model (class-level bug localization algorithm).

2.2.1. Class-Level Feature Scoring Phase

In this phase, each source file in the source files repository is given a score for every feature with respect to the bug report. The proposed model has eight features, which are token matching, textual similarity, stack trace analysis, semantic similarity, and previously repaired bug reports features as used in [4], and an adapted version of bug-fixing frequency, API-enriched lexical similarity, and bug-fixing recency features [8,10] as they use them in the learning-to-rank approach. Meanwhile, in the proposed model, they are adapted to be used in an IR-based approach, as in the score-integration phase of the proposed model. This is achieved using weighted some of all sub-scores, as each feature has a score, and then all scores are normalized and integrated into one score. Each feature is discussed in detail in the following paragraphs.

- Textual similarity

For the similarity in text between the bug report and source code files, some previous studies used a Vector Space Model (VSM), such as [5,6]. Other studies, such as [4,11,12,13,14], used a revised Vector Space Model (rVSM), which was proposed by Zhou et al. [15]; this approach considers the length of the source code file, as a longer source file tends to have a higher probability of containing bugs [15]. In the proposed model, rVSM is used and it represents the bug report and source code file in the form of vectors of term weights. In the proposed model, from the bug report, a summary and a description are represented by a vector of term weights. Similarly, parsed contents from the source code file, such as the class name, method names, attributes, and comments, are represented by a vector of term weights as well. Then, the cosine similarity is performed on the vectors of the source file and the bug report considering the length of the source file. Therefore, in accordance with the rVSM, the textual similarity feature between the bug report br and the source code file s is calculated using the rVSM formula. Therefore, the textual similarity score can be calculated using Equation (1).

where for every source code file, is the length score and is computed using the number of terms in this source code file.

- 2.

- Semantic similarity

Using textual similarity in the bug localization tasks is effective but, in some cases, there is a lexical mismatching between the bug report and the relevant source code file. To overcome this issue, a semantic similarity feature is used to increase the effectiveness of the fault localization tasks. There are many approaches used in the literature to achieve semantic similarity by building the vectors that represent words; these vectors are called word-embedding vectors and capture the semantic relations between words [11]. The most utilized approaches for word embedding are Word2Vec and GloVe [11]. Word2Vec is a family of model optimizations and architectures that uses a large dataset to learn word embeddings [16]. GloVe is used to produce vector representations for words via an unsupervised learning algorithm that learns from combined global word-to-word co-occurrence statistics obtained from a corpus [17]. In our model, GloVe is used to represent word-embedding vectors for the bug report and source code file. To calculate the score of the semantic similarity feature, cosine similarity is computed between the vectors of the bug report and source file according to Equation (2); br is the bug report and s is the source file.

- 3.

- Token matching

This feature focuses on finding the shared tokens among the bug report and each source code file. In cases in which no token is shared between them, a score of 0 is given to this feature.

- 4.

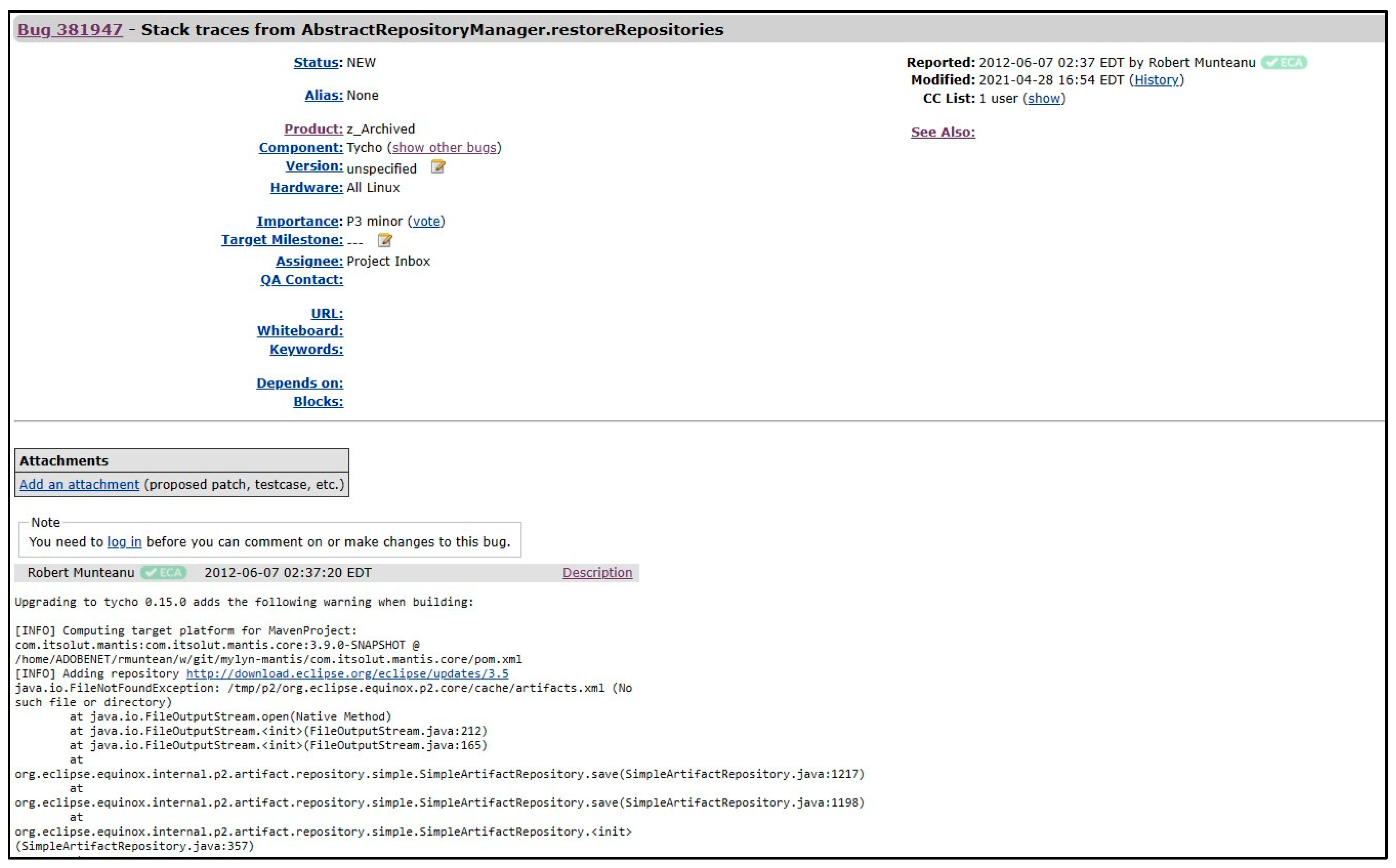

- Stack trace

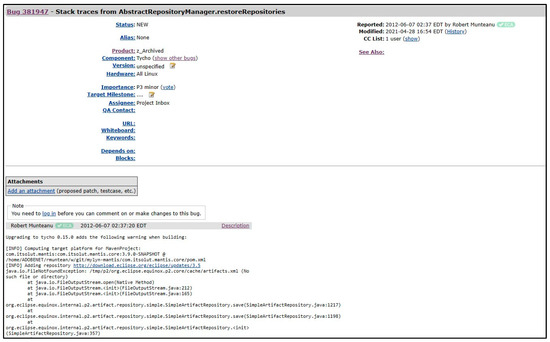

Some bug reports include stack traces; an example of a bug report from the Eclipse (https://bugs.eclipse.org/bugs/show_bug.cgi?id=381947#c0 accessed on 16 October 2023) repository is presented in Figure 3, which contains many stack traces in the description of this bug report. A stack trace can be defined as a series of function calls, which lists all function calls from the beginning of the execution of the software until the crash point [18]. Commonly, the buggy file can be directly found within the stack trace files [4]. There are multiple stack frames in the stack trace; therefore, to extract the stack frames from the description of the bug report, the regular expression is used.

Figure 3.

A bug report containing stack traces.

This feature can be used to find the faulty class relevant to the bug report. In more detail, the score of this feature can be calculated as in Equation (3).

Therefore, a score of 0 is assigned if the source file is not found at the stack trace, and ranks is the position of the source files in the stack trace, and it is the lowest for the first file so the value become the highest for the first file.

- 5.

- Previously fixed bug reports

The previously repaired bug reports feature was effective in enhancing the bug localization process and it is widely used in the literature; for example, it has been used in [4,5,6,11,12,14,15]. Bug reports that have been repaired previously could potentially lead to newer, similar bugs because similar bugs usually fix similar files [19]. Therefore, to compute the score of a previously fixed bug report feature, a classification algorithm, which includes a multi-label and is proposed by Gharibi et al. [4] for previously repaired bug reports, is used in our model to score the relevant source code files for the new bug report using bug reports that have been repaired previously.

- 6.

- API-enriched lexical similarity

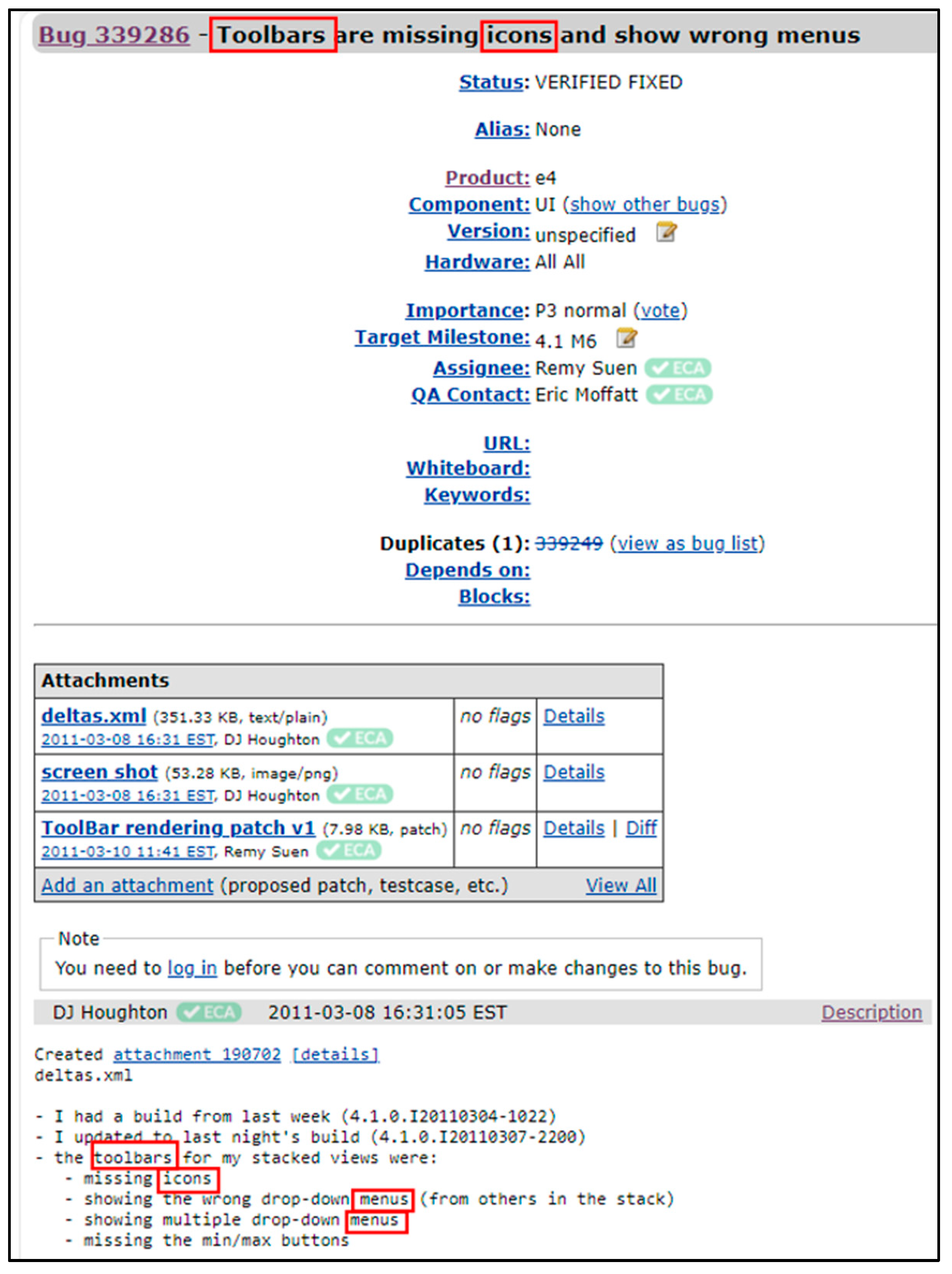

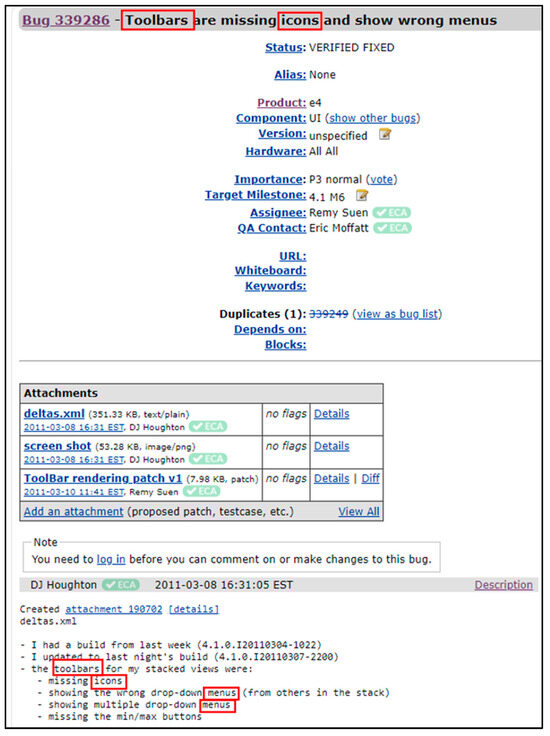

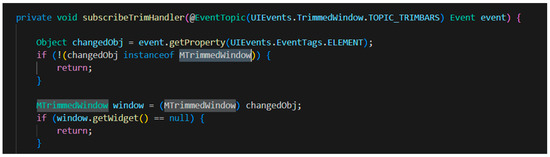

The majority of the content within a bug report consists of natural language terms, while most text in source files is in programming language terms. Therefore, the lexical similarity feature will result in a non-zero score when applying the cosine similarity among the source file and the bug report only if they have a shared token between them. In some cases, there are no shared tokens between the bug report and the source code file; For example, a bug report from the Eclipse project is presented in Figure 4, which illustrates a problem in GUI in which there are missing icons in the toolbar and, additionally, it presents wrong menus; Figure 5 shows a part from the source code file that is related to this bug report. However, the bug report and its related source code file at the surface level do not share any token and, therefore, the lexical similarity in this case will be zero [8].

Figure 4.

Eclipse bug report 339286.

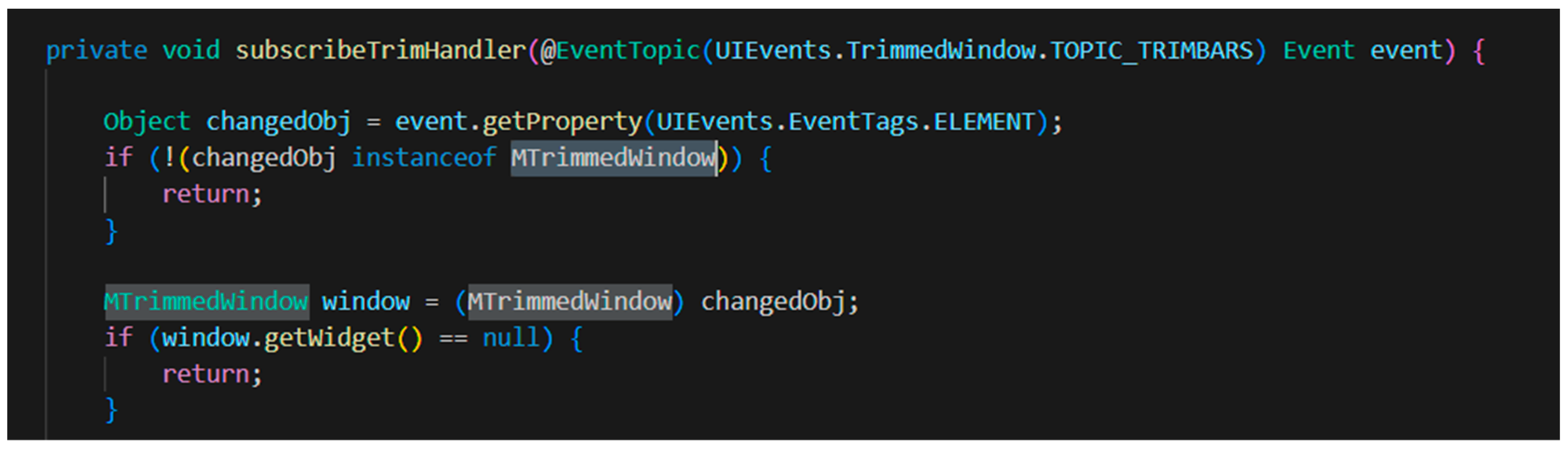

Figure 5.

Code snippet from PartRenderingEngine.java.

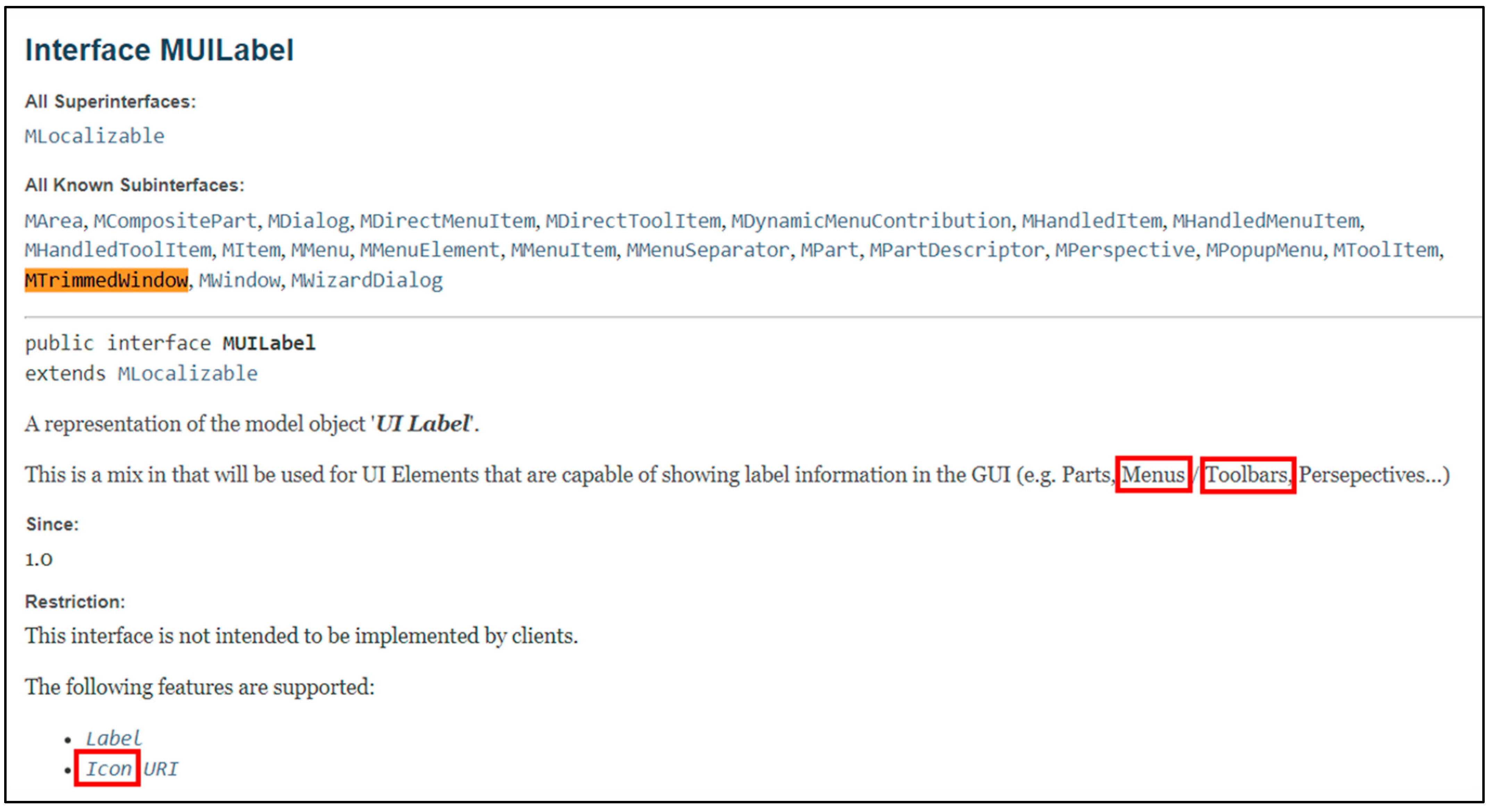

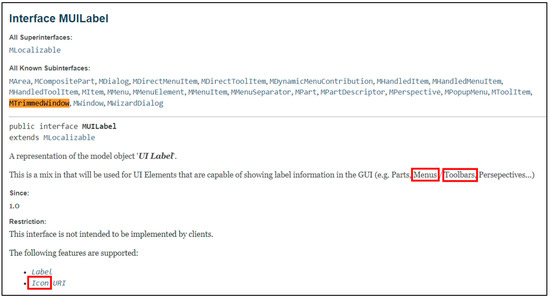

To overcome this gap, textual similarity is applied to the bug report and the API specifications of the classes and interfaces, which are found in the source code file. The Source code file PartRenderingEngine.java, which is related to the mentioned bug report, has a variable window whose type is MTrimmedWindow. In the Eclipse API specification, MUILabel is a superinterface of MTrimmedWindow [8]. Figure 6 shows a part of the API specification of the MUILabel interface, which has some tokens that are shared between this document and the bug report such as the menus, toolbars, and icon [8].

Figure 6.

API specification of the MUILabel interface.

For every method found in a source code file, a set of interface and class names are extracted as well as their textual description using the project API specification, and for every method, there is a document, m.api, which includes all related API descriptions. Moreover, every method in the source file s has its own m.api concatenated to the s.api, which includes the API specifications of every method in that source file. Then, API-enriched lexical similarity can be computed according to Equation (4), which is the maximum similarity between the bug report and per-method API similarities and between the bug report and the whole source file API similarity.

- 7.

- Bug-fixing recency

The version history of the source file gives information that assists in predicting faulty files [20]. For example, a recently repaired source file has a higher probability of containing bugs in comparison to another source file that has not been repaired before or has been repaired a long time ago [8]. Therefore, this observation can be utilized in buggy file localization. In more detail, for any bug report br, let br.month be the month in which the bug report was created and let br(br,s) be the set of bug reports in which the file s was repaired before the bug report was created. Additionally, let last (br,s) ∈ br(br,s); the bug-fixing recency feature can be computed as in Equation (5)

- 8.

- Bug-fixing frequency

A source code file that has undergone frequent fixes can be susceptible to bugs [8]; therefore, this feature can be utilized to localize the buggy classes in which the bug-fixing frequency score is the total number of times that the source file s has been repaired before the current bug report. Equation (6) represents the score of this feature.

2.2.2. Class-Level Final Score and Ranking Phase

Each feature produces a score for every source code file with respect to the new bug report. In our model, a weighted sum of the scores of all features is used, but some scores, such as bug-fixing frequency and token-matching features, need to be normalized first to be in the same scale, from 0 to 1, in order to be comparable with each other before applying the summation. Therefore, score normalization is applied for those scores according to Equation (7); x.min and x.max are the minimum and maximum scores in our set of score values.

Then, the weighted some of the scores of all features is used as in Equation (8), while wi is a value between 0 and 1 which represents the contribution of each feature in the final integrated score. Therefore, all classes are ranked in the form in which the class with the highest final score is the most likely to include the bug reported in the bug report.

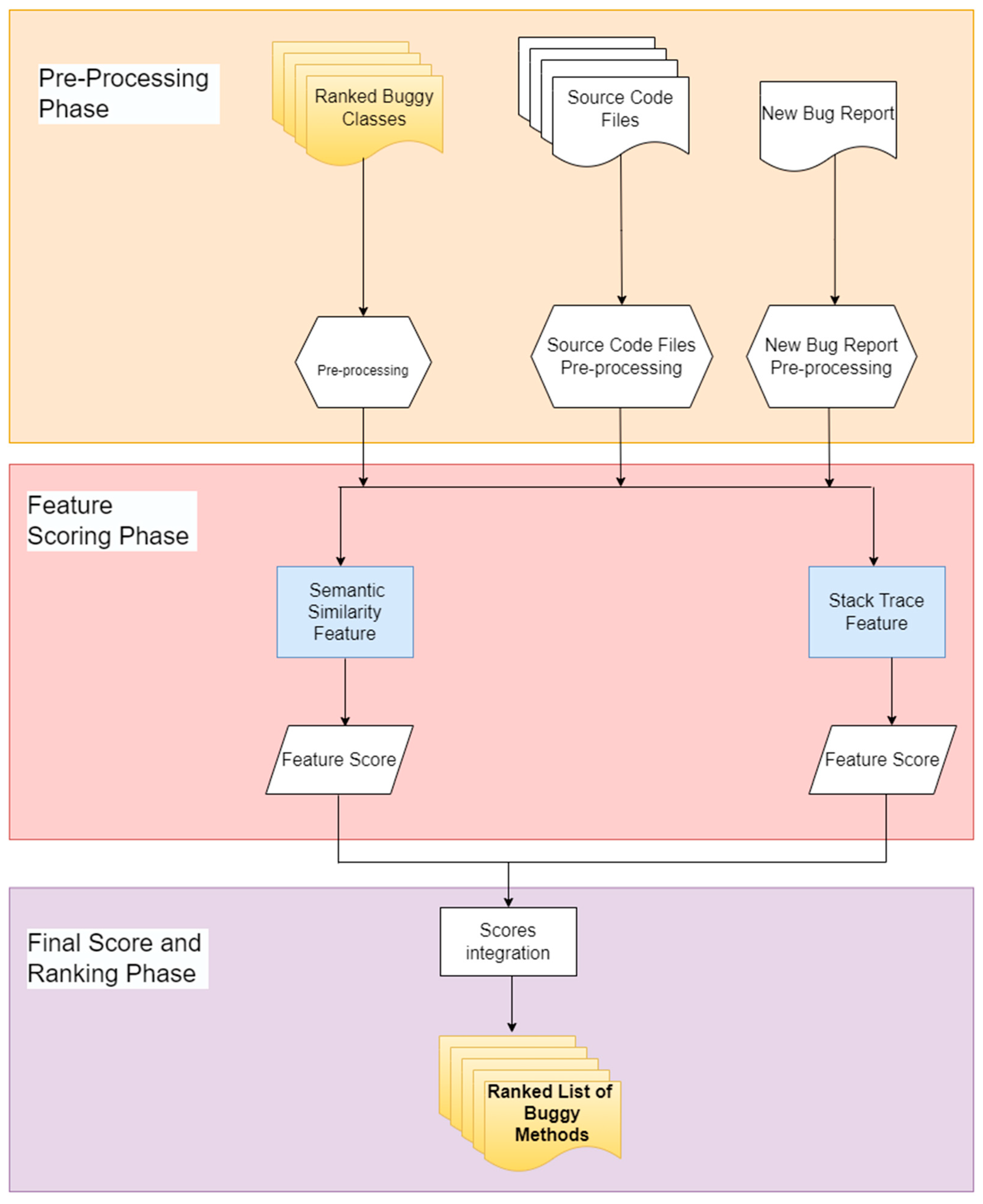

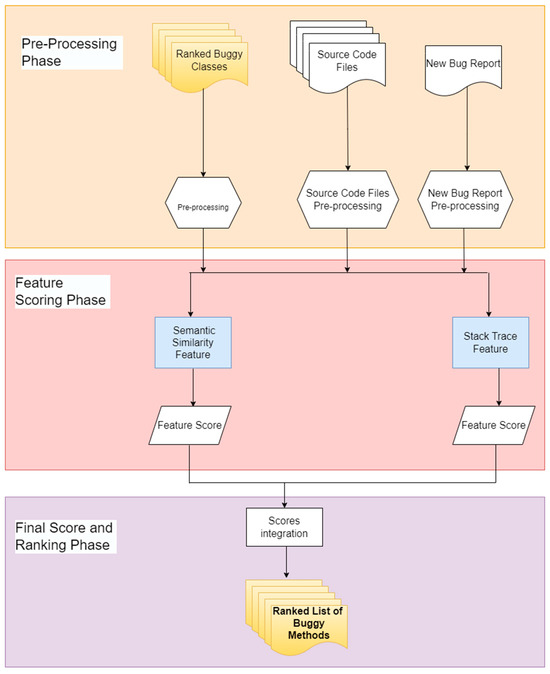

2.3. The Proposed Method-Level Bug Localization Approach

The next level in the proposed model is localizing the methods that most likely contain bugs reported in the bug report. This level is related to the first level in which, after localizing buggy classes, the search space is narrowed down to localize the buggy methods inside these classes. Therefore, this level takes as input the top ten ranked classes that result from the first level, the source code files of the project to be inspected, and the bug report. Additionally, this level has two additional sub-phases, like the class-level bug localization, which are the method-level feature scoring phase and the method-level final score and ranking phase. The method-level feature scoring phase has two features, semantic similarity and stack trace features, which are applied to the methods of the top ten classes that have resulted as an output from the previous level, and each feature produces a score. The next sub-phase calculates and ranks the final score to produce a list of suspect methods, ranking those most likely to include bugs related to the bug report. The second-level architecture of the suggested model is presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The second-level architecture of the proposed model (method-level bug localization algorithm).

2.3.1. Method-Level Feature Scoring Phase

Methods in each class, from the top ten classes that result from the first level, are parsed and extracted; therefore, for each feature, each method will have a score with respect to the bug report, and in the final phase, these sub-scores are integrated and, consequently, the methods are ranked in the order in which the method with the highest score is the first method in the list and will be the most likely to contain the reported bug. Each feature is discussed in detail in the next paragraphs.

- Semantic similarity

For each class, we take all its methods and compute the similarity between each method and the bug report. Method names and the description of the bug report are converted to word embedding using SentenceTransformers (https://huggingface.co/sentence-transformers accessed on 10 October 2023), which is a python framework that is used for converting text, images, and sentences into embeddings; it can compute the embeddings for many languages and these embeddings can be compared with cosine similarity to find text with similar meaning which is beneficial in many fields such as mining a paraphrase, semantic textual similarity, and semantic search [21]. Sentence Transformers have many models, and in our experiment, we compare four sentence-transformer models; All-MiniLM-L6-v2 (https://huggingface.co/sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2 accessed on 10 October 2023) is the fastest among them and provides good quality in comparison to other sentence-transformer models. The similarity scores among the bug reports and every method in the top 10 classes is computed using Equation (9).

where br and m represent the word embeddings for the bug report and the method, respectively.

- 2.

- Stack trace

As illustrated in Section 2.2.1, the bug report may include stack traces, and in the class-level bug localization, the pre-processed stack trace is analyzed against the class name, while at this level, the pre-processed stack trace is analyzed against the method name. Then, each method is given a score, with respect to the bug report, according to Equation (10).

Therefore, a score of 0 will be given if the method name is not found in the stack trace, and otherwise, if the method name is found in the pre-processed stack trace, the method is given a score of ; rankm is the rank of the method m in the stack trace.

2.3.2. Method-Level Final Score and Ranking Phase

As all resultant scores from each feature in the method-level bug localization are in the same range, from 0 to 1, there is no need to normalize scores in this step. The sum of both scores that resulted from features is calculated for each method in the class using Equation (11). Then, according to the resultant integrated score, all methods are ranked in the form in which the method with the highest score is the most likely to include the bug reported in the bug report.

3. Experiment Details

This section presents details of the experiments and presents the implementation of the proposed two-level bug localization model. The computer used in the experiments works with an ×64 Intel(R) Core (TM) i7-10510U CPU @ 1.80GHz and 16.0 GB of RAM, running a 64-bit Windows 10 Operating System. The model is implemented in Python programming language using Visual Studio Code version 1.85.1 with Anaconda.

3.1. Dataset

A dataset of the AspectJ Java open-source project from a publicly available dataset by Ye et al. [8] is used to evaluate the proposed class-level bug localization model. This dataset is extended by Almhana et al. [22] to include data needed to evaluate the method-level bug localization. AspectJ (https://eclipse.dev/aspectj/ accessed on 10 October 2023) extends the Java programming language with aspect-oriented programming (AOP) capabilities [8,23]. The AspectJ project uses GIT as a version control system and BugZilla (https://www.bugzilla.org/ accessed on 10 October 2023) as its bug-tracking system. The dataset contains the source code project, bug reports, and API specifications. Table 1 illustrates the information related to the dataset used and it presents the period for the bug reports and other information related to them such as the number of bug reports that were linked to repaired files. This table shows the number of bug reports which were associated with repaired files and the size of the project, and from the project API specification, it shows the number of API entries that are used in the evaluation.

Table 1.

Dataset details.

3.2. Evaluation Metrics

To indicate the performance of the suggested model, three evaluation metrics are selected, which are widely used in IR-based algorithms. These metrics are top N rank, Mean Average Precision (MAP), and Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR).

- Top N rank:

The top N rank metric is the number of bug reports in which associated repaired files are ranked in the top N; N could be any number, such as 1, 5, or 10, of the returned ranked list [4]. For the input bug report, if there is at least one file in which the bug should be repaired in the list of top N results, it is considered a hit and the location of the bug is determined [4].

- 2.

- Mean Average Precision (MAP):

MAP is a widely used evaluation metric in IR-based approaches. In the MAP metric, the ranks of all buggy files are considered rather than only the first one [22]; therefore, it takes into consideration all buggy files [24]. To compute MAP, the mean of the average precision among all bug reports is taken [22]. The average precision is calculated as in Equation (12), while MAP is calculated using Equation (13), and Precision@k is represented using Equation (13) [4].

m represents the related source files retrieved and ranked as s1, s2, …, sm for each bug report and N represents the set of bug reports.

Precision@k here is the retrieval precision over a set of K source files in the output ranked list and is represented using Equation (14).

- 3.

- Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR):

MRR is the mean of the reciprocal rank among all bug reports, while the reciprocal rank computes the reciprocal of the position at which the first file that contains the bug is found [25]. The MRR can be calculated using Equation (15), where ranki represents the rank of the first buggy file in the i-th bug report and N represents a set of bug reports [25].

4. Results and Discussion

This section demonstrates the obtained results of the proposed model utilizing the dataset at both levels, the class level and the method level. First, the results of the suggested model in class-level bug localization are illustrated. Then, the results of method-level bug localization are presented.

4.1. Class-Level Bug Localization

To indicate the effectiveness of the proposed model in class-level bug localization, the presented evaluation metrics in Section 3 are used. The model has been run on AspectJ bug reports to localize the buggy classes, in the AspectJ project, which are related to each bug report. Each class in the AspectJ project has a combined score with respect to each bug report and, therefore, for every bug report in the bug reports dataset, the proposed model assigns a ranked list of related classes in which the classes with a higher combined score are more likely to include the reported bug, and the class with the highest combined score is the first class in the list. To indicate the effectiveness of the proposed model in the bug localization process, the evaluation metric top N has been used.

As presented in Table 2, in AspectJ bug reports, the proposed model can recommend 176, 296, and 354 buggy classes correctly, which are related to the bug reports in the top 1, top 5, and top 10, respectively. In more detail, the proposed model can recommend correct classes at rates of approximately 29.68%, 49.92%, and 59.70% in the top 1, top 5, and top 10 classes.

Table 2.

Class-level bug localization results.

Additionally, in terms of MAP and MRR, the proposed model achieves 0.267 and 0.391, respectively.

To indicate the performance of the proposed model in class-level bug localization, the achieved results are compared against five algorithms from the literature. These algorithms are the following: (1) The standard VSM method is based on the textual similarity with the bug report; it ranks the source files according to their similarity. (2) The Usual Suspects method only ranks the top N most frequently repaired files [26]. (3) BugLocator [15] uses textual similarity, the size of source files, and previously repaired bugs to rank source files. (4) Learning to rank [8] uses the following six features: textual similarity among the bug report and source files and among the bug report and the API, specification of the interfaces and classes in the source code of the source files, previous bug reports, class name similarity, bug-fixing frequency, and bug-fixing recency, and it uses a learning-to-rank approach to rank and recommend the source files based of these features. (5) The bug localization approach proposed by Gharibi et al. [4] is an IR-based approach that uses five features such as textual and semantic similarities among source files and the bug report, POS tagging, stack trace analysis, and previously repaired bug report analysis.

For a comparison of these algorithms, the results that are reported by Ye et al. [8] in their paper, using the same AspectJ dataset, are used. Meanwhile, for the bug localization model proposed by Gharibi et al. [4], we run it using the same dataset and the environment used in the experiment of the proposed model, as they use a different dataset in their paper, and the results are reported in this paper.

Table 3 shows the MAP and MRR results of the proposed model and the mentioned studies. As illustrated in this table, the proposed model achieves the highest MAP among other algorithms of 0.267, followed by 0.25, 0.22, 0.12, and 0.16, achieved by learning to rank, BugLocator, VSM, and Usual Suspects, respectively. Similarly, in terms of MRR, the proposed model achieves the highest value among all other state-of-the-art models of 0.391, followed by 0.33, 0.32, 0.16, and 0.25 MRR values achieved by learning to rank, BugLocator, VSM, and Usual Suspects, respectively. Consequently, the proposed model at class-level bug localization achieves improvements in terms of MAP values of 6.8%, 21.36%, 122.5%, and 66.87% in comparison with learning to rank, BugLocator, VSM, and Usual Suspects, respectively, and improvements in terms of MRR of 18.48%, 22.18%, 144.37%, and 56.4% in comparison with learning to rank, BugLocator, VSM, and Usual Suspects, respectively. In comparison with Gharibi et al. [4], it is observed that the improvement that has been made using the proposed model, using the AspectJ dataset in the class-level bug localization, is relatively small as their model achieves 0.2659 and 0.388 in terms of MAP and MRR, respectively, while our model achieves 0.267 and 0.391 in terms of MAP and MRR, respectively. However, the proposed model has three additional features, which are bug-fixing recency, bug-fixing frequency, and API-enriched lexical similarity features, which depend on the software project; for example, the project must have enough API specification documents and, therefore, the MAP and MRR results may change in other software projects. Additionally, Gharibi et al. [4] proposed their model to localize buggy classes only, while the proposed model works on two levels to localize buggy classes and buggy methods inside these classes.

Table 3.

Performance comparison.

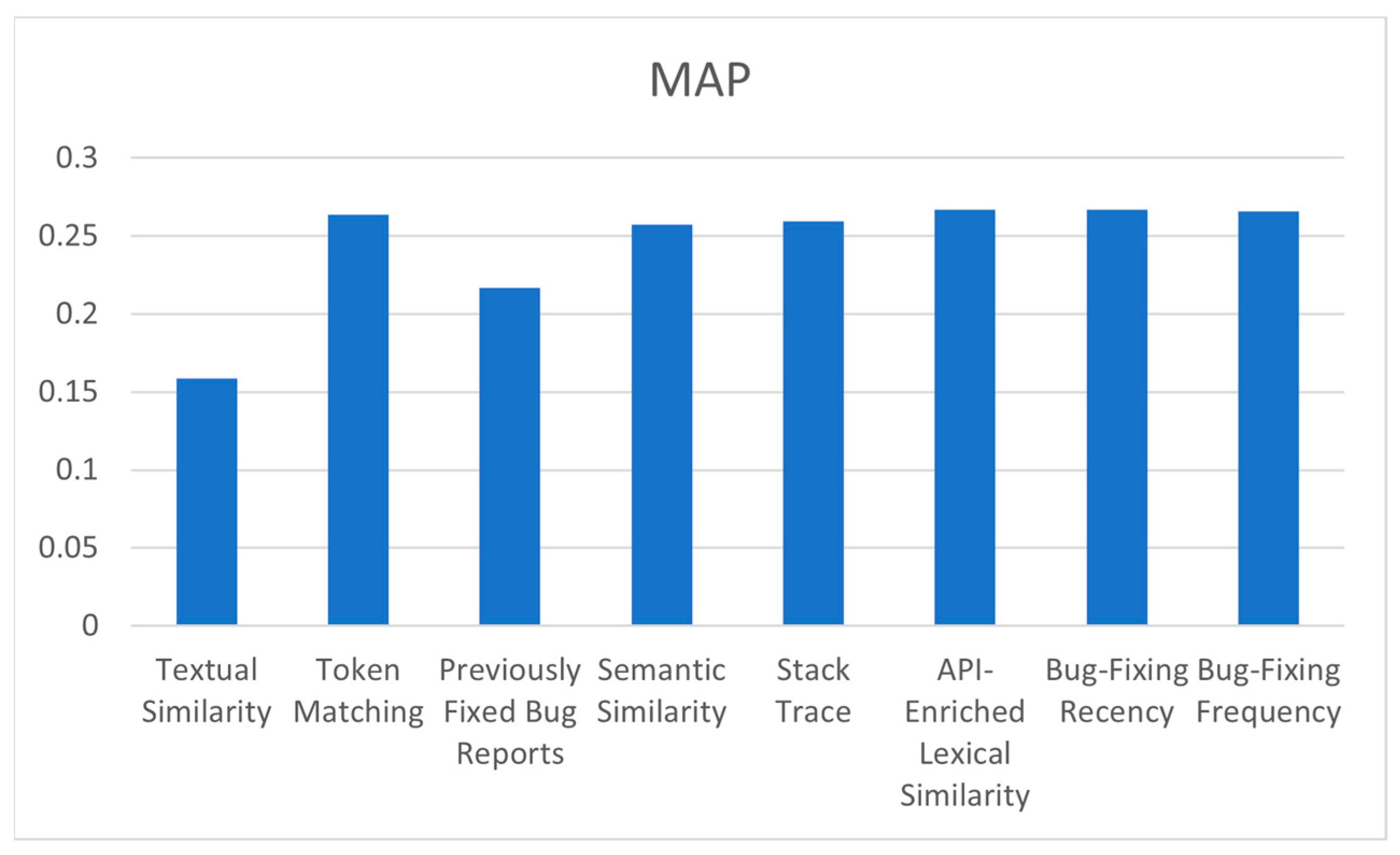

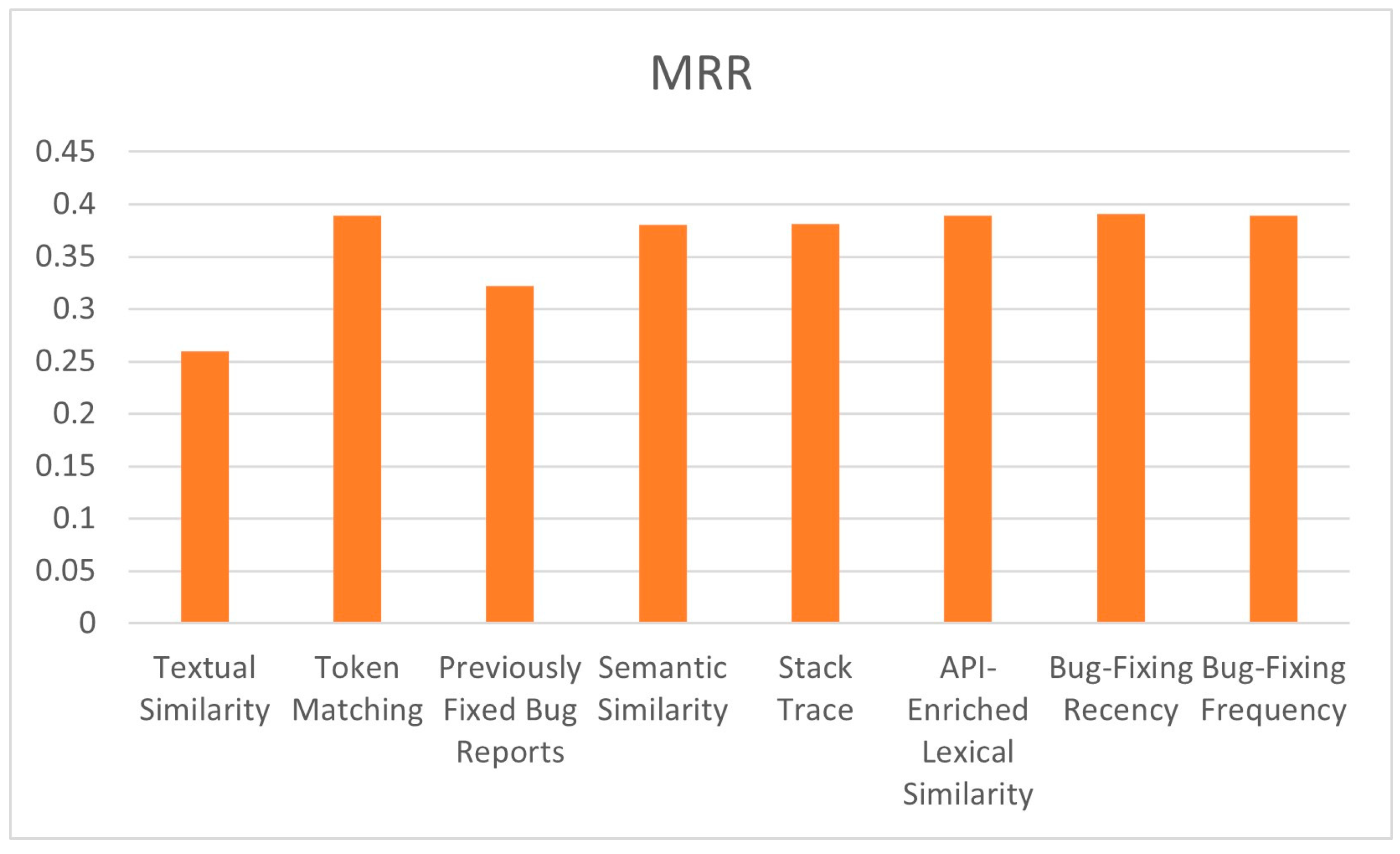

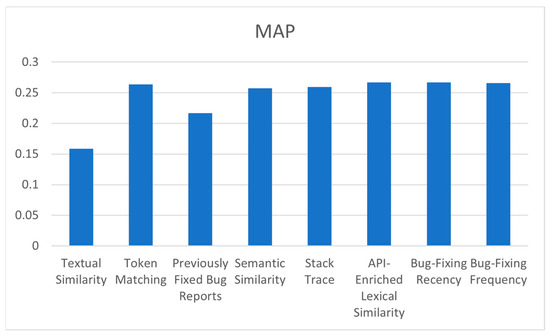

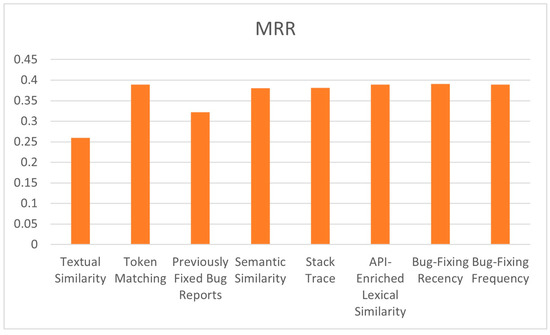

It can be observed from the results that the proposed model, in class-level bug localization, achieved the highest MRR and MAP compared to the mentioned approaches due to the number of features used in the proposed model, which has more features than them. To indicate the effect of each feature on the performance of the proposed model, a new experiment is conducted that runs the model many times, and each time, one feature is excluded and the resultant MAP, MRR, and top N are observed. The results of this experiment are illustrated in Table 4 and Figure 8 and Figure 9. From these figures, it can be observed that the lowest values of MAP and MRR, 0.1585 and 0.2600, respectively, result when the lexical similarity feature is excluded from the model, and this means that the textual similarity feature has the highest impact on the performance of the proposed model. On the other hand, the highest values of MAP and MRR, 0.2670 and 0.3911, respectively, are achieved when the bug-fixing recency feature is removed from the proposed model, which means that this feature has the least impact on the proposed model using the AspectJ dataset. Moreover, according to evaluation metrics values, API-enriched lexical similarity, bug-fixing frequency, and token-matching features have relatively similar impacts on the proposed model’s performance. Additionally, the stack trace and semantic similarity features have a relatively similar effect on the performance of the proposed model. The exclusion of the previously fixed bug report feature resulted in the second lowest MAP and MRR values in the model, which are 0.2170 and 0.3218, respectively, using the AspectJ dataset, and this means this feature has a strong impact on the performance of our model.

Table 4.

The effects of exclusion of each feature on the performance of the proposed model.

Figure 8.

The effects of the exclusion of each feature on MAP.

Figure 9.

The effects of the exclusion of each feature on MRR.

4.2. Method-Level Bug Localization

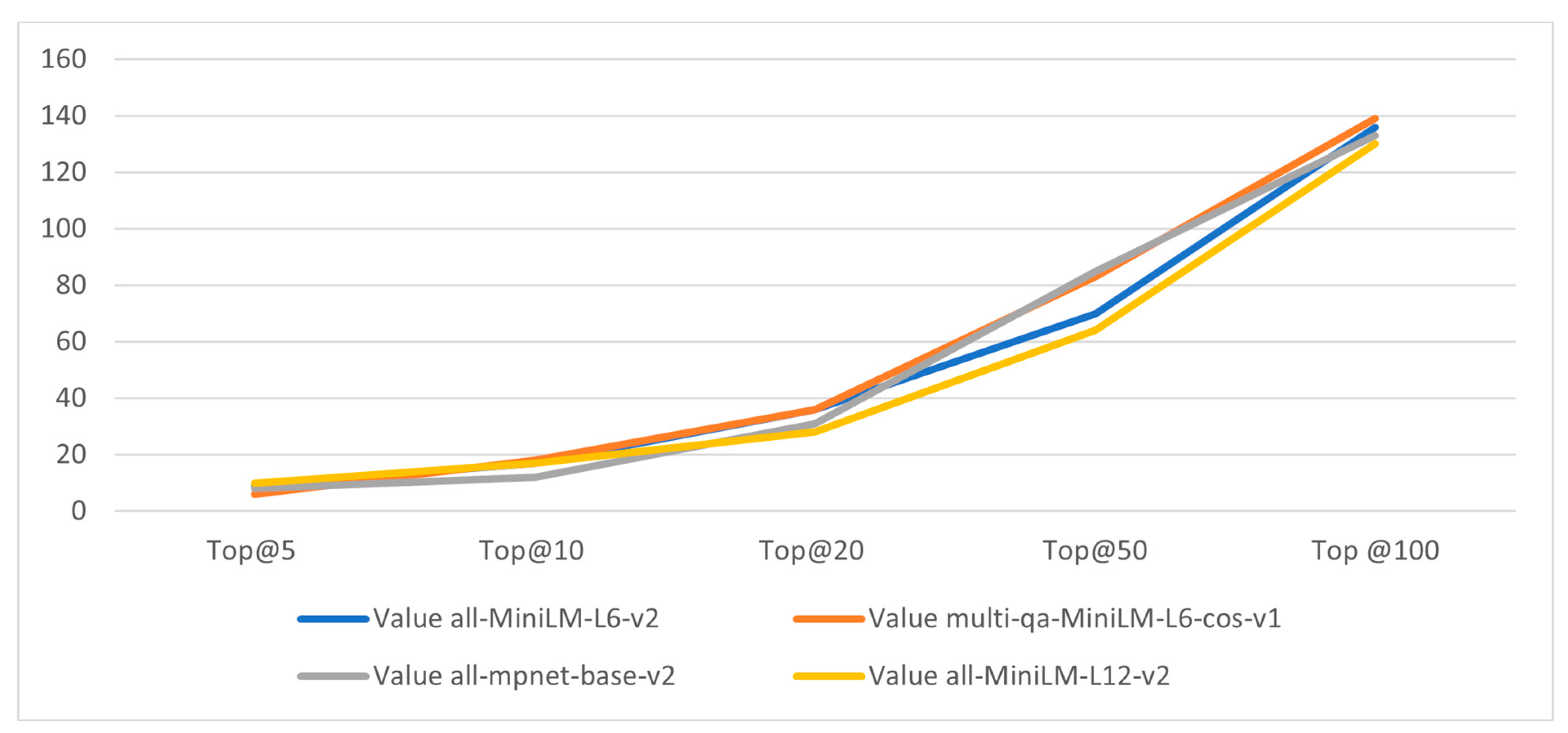

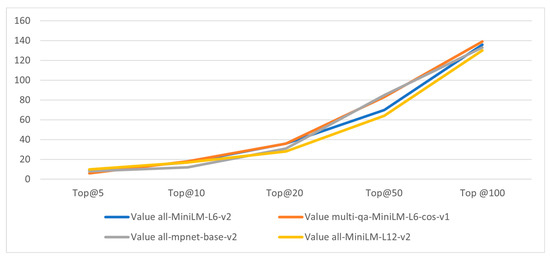

In the second level of the proposed model, there are two components, which are stack trace and semantic similarity features. In semantic similarity features, a sentence-transformer framework from HuggingFace [27] is used to transform both the description of the bug report and method names into word embeddings, and then the cosine similarity is used to compute the semantic similarity among method names and the description of the bug report. The sentence-transformer framework has many pre-trained models that can be used to compute the word embeddings. In the experiment, many sentence-transformer models were used to choose the most suitable model for the proposed model; these models are All-MiniLM-L6-v2, Multi-qa-MiniLM-L6-cos-v1, all-mpnet-base-v2, and All-MiniLM-L12-v2. All-MiniLM-L6-v2 (https://huggingface.co/sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2 accessed on 10 October 2023) is an all-round model tuned for various use cases, and it is trained on a diverse and large dataset of more than 1 billion training pairs and has 384 dimensions. This model can be used for tasks such as semantic search or clustering [28]. The Multi-qa-MiniLM-L6-cos-v1 (https://huggingface.co/sentence-transformers/multi-qa-MiniLM-L6-cos-v1 accessed on 10 October 2023) model was tuned for semantic search, and by giving it a query or question, that is, whether it can find relevant passages, it can be used to find related documents for the given passages. This model was trained on a diverse and large set of (question, answer) pairs and has 384 dimensions. The all-mpnet-base-v2 (https://huggingface.co/sentence-transformers/all-mpnet-base-v2 accessed on 10 October 2023) model was tuned for many use cases, and it is an all-round model trained on a diverse and large dataset of more than 1 billion training pairs and has 768 dimensions. All-MiniLM-L12-v2 (https://huggingface.co/sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L12-v2 accessed on 10 October 2023) has also been tuned for many use cases and is an all-round model trained on a diverse and large dataset of more than 1 billion training pairs, but it has 384 dimensions.

In the evaluation, the top ten classes that are related to each bug report are used as the input for the method-level bug localization stage. For each class of them, the methods inside this class are ranked, with respect to the bug report. Each method has a combined score in which methods with a higher score are more likely to include the reported bug and the method with the highest combined score is the first method in the ranked list.

In the experiment, the number of methods that have been correctly located using each sentence-transformer model is clarified in Table 5. The bold values in the table show the highest number of methods that have been correctly located by all models in one specific top N metric. In more detail, the highest number of methods that have been located correctly in the top 100 is 139 methods, and this is achieved using the Multli-qa-MiniLM-L6-cos-v1 model. For the top 50, the highest number of correctly located methods is 85 methods, achieved via the all-mpnet-base-v2 model. In the top 20, All-MiniLM-L6-v2 and Multi-qa-Mini-L6-cos-v1 both achieved the same number of correctly located methods, which is 36. For the top 10, 18 is the highest number of correctly located methods and is achieved using the Multi-qa-MiniLM-L6-cos-v1 model. For the top 5 methods, 10 is the highest number of correctly located methods and is achieved using the All-MiniLM-L12-v2 model.

Table 5.

Comparison of the performance of each sentence-transformer model on the proposed model in method-level bug localization. The bold values in the table show the highest number of methods that have been correctly located by all models in one specific top N metric.

Figure 10 illustrates the effect of different sentence-transformer models in the proposed method-level fault localization algorithm. As shown in this figure, Multi-qa-MiniLM-L6-cos-v1 has the best performance in the proposed model using the AspectJ dataset but All-MiniLM-L6-v2 has a significant performance as it provides relatively good results among the used models and, additionally, it is faster than them.

Figure 10.

Effect of different sentence-transformer models in the proposed method bug localization algorithm.

5. Related Work

There is a significant amount of research focused on bug report analysis using information retrieval, natural language processing, and artificial intelligence [29]. The fault localization process using bug reports is one of these research areas. The existing approaches of fault localization techniques can be divided into three main categories: information-retrieval-based (IR) approaches, machine learning (ML)/deep learning (DL) with information-retrieval-based (IR) approaches, and optimization algorithms with information-retrieval-based approaches.

5.1. IR-Based Algorithms

Zhou et al. [15] presented a model, BugLocator, for fault localization. In their model, they treat a new bug report as a query, and they introduce a revised Vector Space Model (rVSM) and apply it to the bug report to use it in the search process in the source code repository. This search process produces a list of ranked files, which are source code files that may include the bug. To build their model, they collect many elements, which are the following: the new bug report, similar bugs that have been fixed previously, and a source code repository. They combine the result from applying (rVSM) to the bug report, which is treated as the query and the source code repository, with the ranked result after utilizing previously fixed similar bugs and return combined ranks for the user. Then, the files can be inspected in descending order to locate and fix the bug. However, their model has some limitations such as its dependence on using appropriate naming for classes, methods, and variables, and the performance of their model will be affected if programmers do not use appropriate names. In the same way, if the bug report is written poorly, the performance of the bug localization process will be affected as well.

Saha et al. [9] focused on the bug localization problem and proposed BLUiR, which stands for Bug Localization using Information Retrieval. In their model, the main contribution was enhancing the accuracy of the fault localization process using structured information retrieval. In more detail, this is based on code constructs, i.e., class and method names. Their model requires source code files and bug reports only, taking into consideration bug similarity data if available.

As there is some work in the literature that has been conducted previously to locate the buggy files using bug reports, researchers have worked to increase the accuracy of these models. Wang and Lo, in [6], introduced a new model, namely AmaLgam (Automated Localization of Bug using Various Information), which is used for the bug localization process. To build their model, they integrated three components: a bug prediction algorithm used by Google, which they used in the version history; a BugLocator model that analyzes similar reports; and the BLUiR bug localization model, which utilizes the structure. They achieved improvements of 24.4% and 16.4% in terms of MAP in BugLocator and BLUiR, respectively.

Wang and Lo [5] aimed to enhance the accuracy that they achieved in their previous model AmaLgam [6] and proposed a new method, AmaLgam+, which takes into consideration five sources of information: reporter information, stack traces, version history, structure, and similar reports. To indicate the performance of their model, they used the same dataset used in [6] and achieved an improvement of 12.0% in terms of MAP in comparison with AmaLgam [6].

Wong et al. [12] developed a novel method for the bug localization process called BRTracer. In more detail, the idea behind their approach consists of two main parts, which are stack trace analysis and segmentation. In segmentation, every source code file is divided into a number of segments, and the segment that has the highest similarity to the bug report is chosen to represent the file. In stack trace analysis, their model recognizes the files that are relevant to the stack trace in the bug report and raises their rank. An evaluation of the results shows that BRTracer outperforms the BugLocator model.

Zhou et al. [13] introduced a novel fault localization method using the information in bug reports and source code files. In their model, they utilized the part-of-speech (POS) features of the bug report and source files’ invocation relationships. Additionally, to increase the performance of their model, they integrated an adaptive technique, which distinguishes the top 1 and top N for the input bug report. The adaptive technique has two models: the first model increased the accuracy of the first recommended file and the second one enhanced the accuracy of the fixed defect file list.

Youm et al. [14] proposed the BLIA model, Bug Localization using Integrated Analysis. In their model, they used text, comments, and stack traces in the bug report, the structured information of the source files, and the change history of the source code file, and integrated them. They enhanced fault localization from the class level to the localized buggy methods.

Seyam et al. [11] proposed a novel approach, namely the hybrid bug localization approach (HBL), for fault localization. The key insight behind their method is the fact that more complex source code files are more likely to be modified and more susceptible to bugs than less complex files. In more detail, their model utilized semantic and textual features of source files, complexity of source code, version history, stack trace analysis, POS tagging, and bug reports that have been fixed previously.

Table 6 summarizes previous IR-based studies. The first column of this table shows the name of the model and its reference. The second column presents the information retrieval method, which is used in each model. The similarity between the bug report and source file column shows the models that use textual similarity between the bug report and the source files. Structured information of the source code column shows the models that use the structure information of the source code as a feature to use it in the bug localization process. The previously fixed bug report column presents the models that utilize information about similar fixed bug reports and use it in their bug localization model. The version history column shows the models that use information from the version control system in their model. The POS tagging column shows models that use part-of-speech tagging in their bug localization model. The call graph column indicates models that use the invocation relationship among source files in their bug localization model. The semantic similarity column shows models that utilize the semantic similarity feature among the bug report and source files. The code complexity column shows models that use the code complexity feature in the fault localization process. The reporter information column shows models that use information about bug reporters. Finally, The evaluation metrics column shows the evaluation metrics that are used to indicate the effectiveness of each proposed fault localization model, and in the discussed IR-based studies, all of them used the same evaluation metrics, which are top N rank, Mean Average Precision (MAP), and Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR).

Table 6.

Comparison of previous IR-based bug localization approaches.

5.2. ML/DL with IR-Based Approaches

There are several existing bug localization algorithms that use machine learning or deep learning algorithms with information retrieval approaches to localize faulty files. The learning-to-rank technique, sometimes called machine-learned ranking (MLR) [30], is the use of machine-learning algorithms to build ranking models for IR systems [30]. Learning-to-rank models train themselves and provide the optimal order of the results to increase the relevancy of the results they deliver [30]. Ye et al. [8] proposed a novel learning-to-rank-based algorithm, which consists of several features, namely textual similarity among the bug report and source files and among the bug report and the application programming interfaces (APIs), specification of the interfaces and classes in the source code of the source files, previous bug reports, class name similarity, bug-fixing frequency, and bug-fixing recency. They used a learning-to-rank approach in which for the bug report, the score of every source file in the ranked list is calculated as a weighted sequence of an array of features encoding domain knowledge, and the weights undergo automatic training by using a learning-to-rank algorithm on bug reports that have been solved previously.

Lam et al. [31] proposed a novel method, named HyLoc, to localize faulty files for bug reports. The main insight behind their model is to overcome the lexical mismatching among the source code files and the bug report. In their model, they combine rVSM, an IR approach, with DNN, which is a deep learning algorithm. In more detail, rVSM is used to find the textual similarity among bug reports and source files while DNN measures the relevancy between them to overcome the lexical mismatching. Additionally, they use additional types of features, which are metadata features. These features are extracted from the history of bug fixing. In the evaluation process, they use the same dataset used by [8] and achieve better performance.

Huo et al. [32] presented a novel method for fault localization, namely NP-CNN, which utilized program structure and lexical information to learn unified features from source code in programming language and natural language to use them in locating buggy source files that are relevant for bug reports.

Lam et al. [33] proposed a model, namely DNNLOC, for bug localization. Their model combines IR with deep learning. In more detail, they integrate rVSM with DNN and use many features to improve the effectiveness of their model. The three main features are textual similarity among the bug report and source files using rVSM, relevancy between them using DNN, and metadata. These metadata features include bug-report-fixing history, bug-report-fixing frequency, and class name in the bug report and the source code file. In the evaluation, they use the same dataset used in [31] and achieve better results in comparison with some previous models for bug localization. In fact, in contrast with their previous work [31], they achieved the same MAP values.

Other researchers focus on making full use of semantic information in the bug localization process. Therefore, Xiao et al. [34] propose a new approach, namely DeepLocator, which includes an enhanced CNN (Convolutional Neural Network) integrated with a new rTF-IDuF method (term frequency–user-focused inverse document frequency), which is revised as TF-IDuF (rTF-IDuF). Additionally, they integrated their model with a pretrained word2vec technique. Their algorithm outperforms some state-of-the-art fault localization approaches, and they achieve 3.8% higher MAP in comparison with HyLoc.

Yang and Lee [35] focused on applying the LDA topic-modelling algorithm in a fault-localization technique. They utilized information about similar commits in modeling topics and used it in a bug localization process. Their approach consisted of many steps. Firstly, their approach determined topics that are similar to the new bug report. Secondly, for these topics, their method extracted bug reports and commits that are similar to these topics. Therefore, the similarity degree between the bug report and the source code was calculated. Their model used the CNN_LSTM network in which similar bug reports were input for CNN and the output is the extracted features, which go to LSTM as the input and result in similar source code files as the output. Finally, files of the buggy source code were scored. Overall, their model achieved 81.7% as an average F-measure. Table 7 summarizes and compares ML/DL and IR-based approaches.

Table 7.

Comparison of previous ML/DL with IR-based bug localization approaches.

5.3. Optimization Algorithms with IR-Based Approaches

Other researchers have focused on applying search-based software engineering and used it in buggy file localizations using bug reports. In fact, Almhana et al. [36] proposed the first bug localization model using this approach. In more detail, their approach integrated utilizing history-based and lexical similarity measures to find and rank related classes for bug reports. Their approach used a multi-objective search by reducing the number of recommended classes and increasing the relevance of the solution. To propose their model, they adopted the non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm (NSGA-II) [37].

6. Conclusions and Future Work

In the software development lifecycle, the maintenance phase concerns fixing the bugs discovered after the software has been released. To decrease the time required for maintenance, researchers have focused on automating the bug localization process. To contribute to this field, a novel model was proposed to localize buggy classes and methods using the bug report. The proposed model takes the bug report, source files of the software project, API documentations of classes and interfaces, and version control system (VCS) data as input, and it consists of two levels; the first level is responsible for localizing buggy classes, and the second level is responsible for localizing buggy methods. The first level contains eight features: token matching, textual similarity, stack trace, semantic similarity, previously fixed bug reports, API-enriched lexical similarity, bug-fixing frequency, and bug-fixing recency. The second level contains two features: semantic similarity and stack trace. The proposed model was evaluated using the AspectJ open-source Java project, and the achieved results show that the proposed model outperforms several state-of-the-art approaches in terms of MAP, MRR, and top N metrics in the class-level bug localization. The proposed model at class-level bug localization achieves improvements in terms of MAP of 6.8%, 21.36%, 122.5%, and 66.87% in comparison with learning to rank, BugLocator, VSM, and Usual Suspects, respectively, and improvements in terms of MRR of 18.48%, 22.18%, 144.37%, and 56.4% in comparison with learning to rank, BugLocator, VSM, and Usual Suspects, respectively. In comparison with Gharibi et al. [4], it was observed that the improvement made using the proposed model, using the AspectJ dataset in the class-level bug localization, is relatively small as it achieved improvements of 0.41%, and 0.51% in terms of MAP and MRR, respectively. However, the proposed model has three additional features, which are bug-fixing recency, bug-fixing frequency, and API-enriched lexical similarity features, which depend on the software project; for example, the project must have enough API specification documents and, therefore, the MAP and MRR results may vary in other software projects. Additionally, Gharibi et al. [4] proposed their model to localize buggy classes only, while the proposed model works on two levels to localize buggy classes and buggy methods inside these classes.

Future work will enhance this model by utilizing deep learning algorithms in the bug localization process and increasing the number of features in method-level bug localization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A., A.A.A.G.-E., A.N. and F.E.; methodology, S.A., A.A.A.G.-E., A.N. and F.E.; software, S.A.; validation, S.A., A.A.A.G.-E., A.N. and F.E.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.; writing—review and editing, S.A, A.A.A.G.-E., A.N. and F.E.; visualization, S.A.; supervision, A.N., A.A.A.G.-E. and F.E.; project administration, A.N., A.A.A.G.-E. and F.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University (KAU).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University (KAU), Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, funded this project under grant no. (KEP-PhD-102-611-1443). The authors, therefore, acknowledge DSR for the financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- IEEE Std 610.12-1990; IEEE Standard Glossary of Software Engineering Terminology. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1990. [CrossRef]

- Erfani Joorabchi, M.; Mirzaaghaei, M.; Mesbah, A. Works for me! characterizing non-reproducible bug reports. In Proceedings of the 11th Working Conference on Mining Software Repositories, Hyderabad, India, 31 May–1 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Breu, S.; Premraj, R.; Sillito, J.; Zimmermann, T. Information needs in Bug Reports. In Proceedings of the 2010 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Savannah, GA, USA, 6–10 February 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gharibi, R.; Rasekh, A.H.; Sadreddini, M.H.; Fakhrahmad, S.M. Leveraging textual properties of bug reports to localize relevant source files. Inf. Process. Manag. 2018, 54, 1058–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lo, D. Amalgam+: Composing rich information sources for accurate bug localization. J. Softw. Evol. Process 2016, 28, 921–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lo, D. Version history, similar report, and structure: Putting them together for improved bug localization. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Program Comprehension, Hyderabad, India, 2–3 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, C.D.; Raghavan, P.; Schutze, H. An Introduction to Information Retrieval; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X.; Bunescu, R.; Liu, C. Learning to rank relevant files for bug reports using domain knowledge. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Foundations of Software Engineering, Hong Kong, China, 16–22 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, R.K.; Lease, M.; Khurshid, S.; Perry, D.E. Improving bug localization using structured information retrieval. In Proceedings of the 2013 28th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering (ASE), Silicon Valley, CA, USA, 11–15 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fejzer, M.; Narebski, J.; Przymus, P.; Stencel, K. Tracking buggy files: New efficient adaptive bug localization algorithm. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2022, 48, 2557–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyam, A.A.; Hamdy, A.; Farhan, M.S. Code complexity and version history for enhancing hybrid bug localization. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 61101–61113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.-P.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Hao, D.; Zhang, L.; Mei, H. Boosting bug-report-oriented fault localization with segmentation and Stack-trace analysis. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Software Maintenance and Evolution, Victoria, BC, Canada, 29 September–3 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Tong, Y.; Chen, T.; Han, J. Augmenting bug localization with part-of-speech and invocation. Int. J. Softw. Eng. Knowl. Eng. 2017, 27, 925–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youm, K.C.; Ahn, J.; Lee, E. Improved bug localization based on code change histories and Bug Reports. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2017, 82, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, H.; Lo, D. Where should the bugs be fixed? more accurate information retrieval-based bug localization based on bug reports. In Proceedings of the 2012 34th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE), Zurich, Switzerland, 2–9 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- word2vec|Text. TensorFlow. Available online: https://www.tensorflow.org/text/tutorials/word2vec (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Pennington, J.; Socher, R.; Manning, C.D. GloVe: Global Vectors for Word Representation. Available online: https://nlp.stanford.edu/projects/glove (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Sabor, K.K. Automatic Bug Triaging Techniques Using Machine Learning and Stack Traces. Ph.D. Thesis, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy-Hill, E.; Zimmermann, T.; Bird, C.; Nagappan, N. The design of bug fixes. In Proceedings of the 2013 35th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE), San Francisco, CA, USA, 18–26 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, F.; Devanbu, P. How, and why, process metrics are better. In Proceedings of the 2013 35th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE), San Francisco, CA, USA, 18–26 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Sentence-bert: Sentence embeddings using Siamese Bert-Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), Hong Kong, China, 3–7 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Almhana, R.; Kessentini, M.; Mkaouer, W. Method-level bug localization using hybrid multi-objective search. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2021, 131, 106474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiczales, G.; Hilsdale, E. Aspect-oriented programming. ACM SIGSOFT Softw. Eng. Notes 2001, 26, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, F.; Assunção, W.K.; Huang, L.; Mayr-Dorn, C.; Ge, J.; Luo, B.; Egyed, A. Rat: A refactoring-aware traceability model for bug localization. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ACM 45th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE), Melbourne, Australia, 14–20 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A.R.; Chen, T.-H.; Wang, S. Pathidea: Improving information retrieval-based bug localization by re-constructing execution paths using logs. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2022, 48, 2905–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Tao, Y.; Kim, S.; Zeller, A. Where should we fix this bug? A two-phase recommendation model. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2013, 39, 1597–1610. [Google Scholar]

- Hugging Face—The AI Community Building the Future. Available online: https://huggingface.co/ (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Sentence-Transformers/All-Minilm-L6-V2 Hugging Face. Available online: https://huggingface.co/sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2 (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Alsaedi, S.A.; Noaman, A.Y.; Gad-Elrab, A.A.; Eassa, F.E. Nature-based prediction model of bug reports based on Ensemble Machine Learning Model. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 63916–63931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Quick Guide to Learning to Rank Models. Available online: https://practicaldatascience.co.uk/machine-learning/a-quick-guide-to-learning-to-rank-models (accessed on 6 October 2023).

- Lam, A.N.; Nguyen, A.T.; Nguyen, H.A.; Nguyen, T.N. Combining deep learning with information retrieval to localize buggy files for bug reports. In Proceedings of the 2015 30th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering (ASE), Lincoln, NE, USA, 9–13 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, X.; Li, M.; Zhou, Z.-H. Learning Unified Features from Natural and Programming Languages for Locating Buggy Source Code. IJCAI 2016, 16, 1606–1612. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, A.N.; Nguyen, A.T.; Nguyen, H.A.; Nguyen, T.N. Bug localization with combination of deep learning and Information Retrieval. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/ACM 25th International Conference on Program Comprehension (ICPC), Buenos Aires, Argentina, 22–23 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Keung, J.; Mi, Q.; Bennin, K.E. Improving bug localization with an enhanced convolutional neural network. In Proceedings of the 2017 24th Asia-Pacific Software Engineering Conference (APSEC), Nanjing, China, 4–8 December 2017; pp. 338–347. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Lee, B. Utilizing topic-based similar commit information and CNN-LSTM algorithm for bug localization. Symmetry 2021, 13, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almhana, R.; Mkaouer, W.; Kessentini, M.; Ouni, A. Recommending relevant classes for bug reports using multi-objective search. In Proceedings of the 31st IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering, Singapore, 3–7 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).