Multi-Environment Vehicle Trajectory Automatic Driving Scene Generation Method Based on Simulation and Real Vehicle Testing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Graph Theory

2.2. Artificial Potential Field

2.3. The Fusion of Graph Theory and APF

3. Experiment and Result Analysis

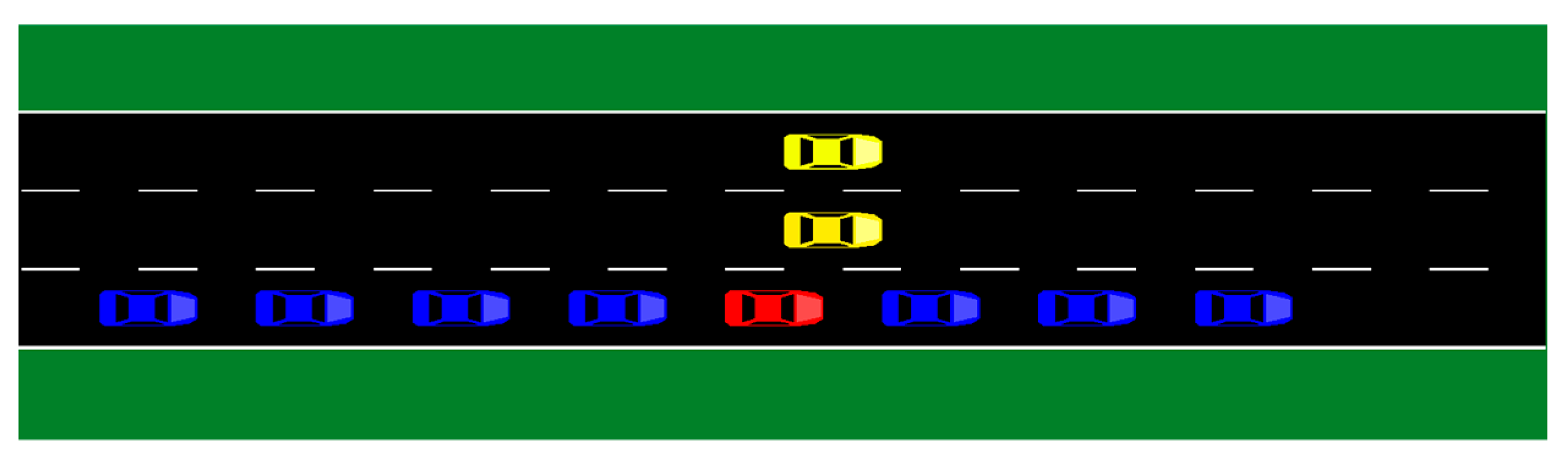

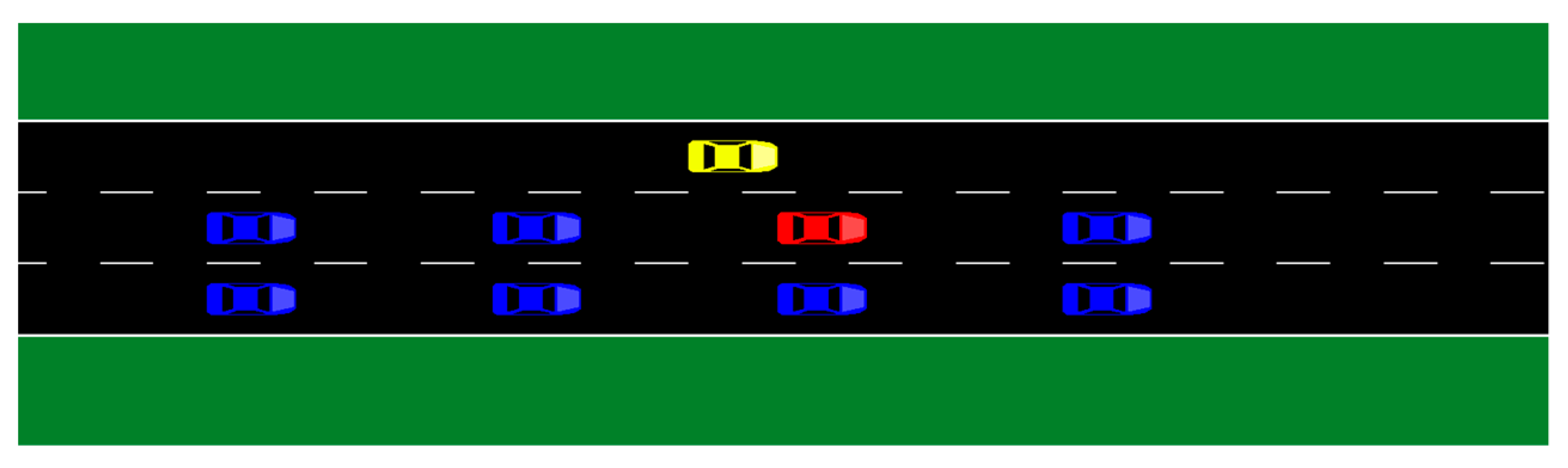

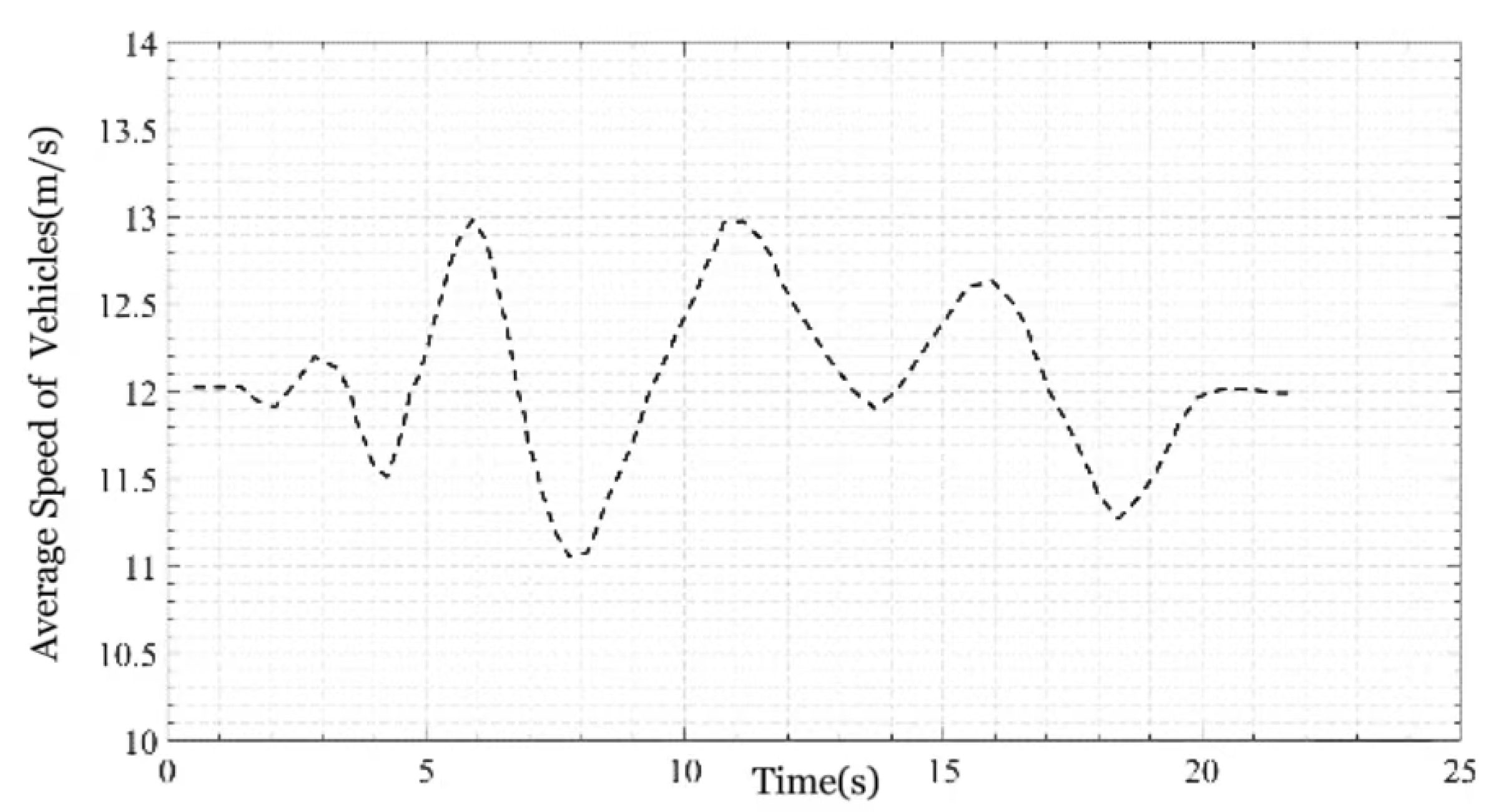

3.1. Simulation Experiment

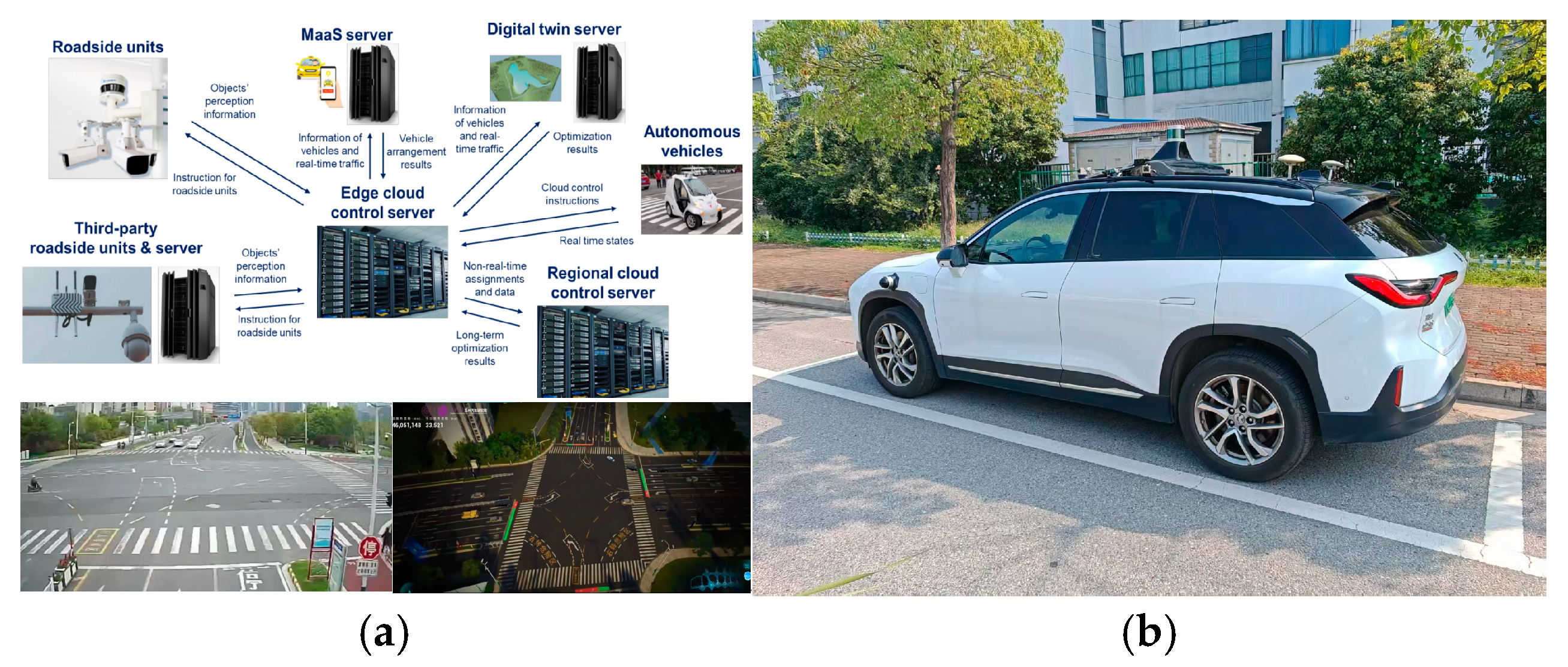

3.2. Field Experiment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Xu, L.; He, B.; Zhou, H.; He, J. Impact and Revolution on Law on Road Traffic Safety by Autonomous Driving Technology in China. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2023, 51, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Yu, C.; Kodaka, K.; Li, K. Driving risk assessment using cluster analysis based on naturalistic driving data. In Proceedings of the 17th International IEEE Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Qingdao, China, 8–11 October 2014; pp. 2584–2589. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, H.; Xu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Gong, Y.; Huang, T.S. A general framework to detect unsafe system states from multisensor data stream. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2009, 11, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.X.; Chen, L.; Liang, J.; Cai, Y.F.; Jiang, H.B. Simulation study of driving risk discrimination method based on driver collision avoidance behavior. Automot. Eng. 2019, 41, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Arbabzadeh, N.; Jafari, M. A data-driven approach for driving safety risk prediction using driver behavior and roadway information data. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2017, 19, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhu, J. Estimating Risk Levels of Driving Scenarios through Analysis of Driving Styles for Autonomous Vehicles. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.10176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAE On-Road Automated Vehicle Standards Committee. Taxonomy and definitions for terms related to on-road motor vehicle automated driving systems. SAE Standard J. 2014, 3016, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Klischat, M.; Althoff, M. Generating Critical Test Scenarios for Automated Vehicles with Evolutionary Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Paris, France, 9–12 June 2019; pp. 2352–2358. [Google Scholar]

- Nalic, D.; Mihalj, T.; Bäumler, M.; Lehmann, M.; Eichberger, A.; Bernsteiner, S. Scenario Based Testing of Automated Driving Systems: A Literature Survey. FISITA Web Congr. 2020, 2020, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Riedmaier, S.; Ponn, T.; Ludwig, D.; Schick, B.; Diermeyer, F. Survey on Scenario-Based Safety Assessment of Automated Vehicles. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 87456–87477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Review of Scenario-based Virtual Validation Methods for Automated Vehicles. China J. Highw. Transp. 2019, 32, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Drechsler, M.F.; Peintner, J.; Reway, F.; Seifert, G.; Riener, A.; Huber, W. MiRE, A Mixed Reality Environment for Testing of Automated Driving Functions. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 3443–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedmaier, S.; Schneider, D.; Watzenig, D.; Diermeyer, F.; Schick, B. Model Validation and Scenario Selection for Virtual-Based Homologation of Automated Vehicles. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmen, U.; Osterloh, T.; Roßmann, J. Structured Validation of AI-Based Systems by Virtual Testing in Simulated Test Scenarios. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 18910–18924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.; Leitão, J.M.; Pereira, J.P.; Ribas, A.; Coelho, A.F. Procedural Generation of Topologic Road Networks for Driving Simulation. In Proceedings of the 2015 10th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), Aveiro, Portugal, 17–20 June 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, M. Graph-Based Generation of OpenSCENARIO-Driving-Scenarios for Virtual Validation of Automated Driving Functions. PhD Thesis, Technische Hochschule Ingolstadt, Ingolstadt, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Thieling, J.; Mathar, M.; Roßmann, J. Automated Generation of Virtual Road Scenarios For Efficient Tests of Driver Assistance Systems. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE AUTOTESTCON, Schaumburg, IL, USA, 9–15 September 2017; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Gao, S.; Li, L.; Sun, B.; Cheng, S. Obstacle Avoidance Path Planning Design for Autonomous Driving Vehicles Based on an Improved Artificial Potential Field Algorithm. Energies 2019, 12, 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, M.C.; Tornero, J. Path Planning and Trajectory Generation Using Multi-Rate Predictive Artificial Potential Fields. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Nice, France, 22–26 September 2008; pp. 2990–2995. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.; Hu, J.; Bhowmick, P.; Ding, Z.; Arvin, F. Distributed Motion Planning for Safe Autonomous Vehicle Overtaking via Artificial Potential Field. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 21531–21547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, O. Real-Time Obstacle Avoidance for Manipulators and Mobile Robots. Int. J. Robot. Res. 1986, 5, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H.-T.; Malone, N.; Lesser, K.; Oishi, M.; Tapia, L. Path-Guided Artificial Potential Fields with Stochastic Reachable Sets for Motion Planning in Highly Dynamic Environments. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Seattle, WA, USA, 26–30 May 2015; pp. 2347–2354. [Google Scholar]

- Das, M.S.; Sanyal, S.; Mandal, S. Navigation of Multiple Robots in Formative Manner in an Unknown Environment Using Artificial Potential Field Based Path Planning Algorithm. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajzewicz, D.; Erdmann, J.; Behrisch, M.; Bieker, L. Recent development and applications of SUMO-Simulation of Urban MObility. Int. J. Adv. Syst. Meas. 2012, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Graph Theory and Artificial Potential Field Method | RRT | |

|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 | 21 s | 36 s |

| Scenario 2 | 18 s | 30 s |

| Graph Theory and Artificial Potential Field Method | RRT | |

|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 | 23 s | 45 s |

| Scenario 2 | 20 s | 39 s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cao, Y.; Sun, H.; Li, G.; Sun, C.; Li, H.; Yang, J.; Tian, L.; Li, F. Multi-Environment Vehicle Trajectory Automatic Driving Scene Generation Method Based on Simulation and Real Vehicle Testing. Electronics 2025, 14, 1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14051000

Cao Y, Sun H, Li G, Sun C, Li H, Yang J, Tian L, Li F. Multi-Environment Vehicle Trajectory Automatic Driving Scene Generation Method Based on Simulation and Real Vehicle Testing. Electronics. 2025; 14(5):1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14051000

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Yicheng, Haiming Sun, Guisheng Li, Chuan Sun, Haoran Li, Junru Yang, Liangyu Tian, and Fei Li. 2025. "Multi-Environment Vehicle Trajectory Automatic Driving Scene Generation Method Based on Simulation and Real Vehicle Testing" Electronics 14, no. 5: 1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14051000

APA StyleCao, Y., Sun, H., Li, G., Sun, C., Li, H., Yang, J., Tian, L., & Li, F. (2025). Multi-Environment Vehicle Trajectory Automatic Driving Scene Generation Method Based on Simulation and Real Vehicle Testing. Electronics, 14(5), 1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14051000