Precision Forecasting in Colorectal Oncology: Predicting Six-Month Survival to Optimize Clinical Decisions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset Description

2.2. Data Preprocessing

2.3. Construction of Predictive Models

- (1)

- The logistic regression (LR) model [41] is commonly employed for binary classification tasks, due to its ability to express the relationship between input features and the target variable in a linear fashion. The model is mathematically expressed as follows:where P(Y) is the probability of the dependent variable, is the intercept, and represents the regression coefficient for each predictor, . Logistic regression assumes that the log-odds of the dependent variable are linearly related to the independent variables. This makes it particularly suitable for datasets where the relationship between the predictors and the target variable is approximately linear. This model served as a baseline for comparing the performance of the other models.

- (2)

- The decision tree (DT) model [42] is a nonparametric algorithm widely used for classification tasks due to its ability to split data into homogeneous subsets based on specific criteria. The model is built upon a recursive partitioning process, where each split aims to maximize the purity of the resulting subsets. One commonly used criterion for assessing split quality is the Gini index, calculated as follows:where is the metric for assessing the purity of splits and represents the probability of the data point belonging to class . Lower Gini values indicate greater homogeneity within the subsets. Decision trees are particularly valued for their transparency and ease of interpretability, as the decision-making process can be visualized as a tree-like structure.

- (3)

- The random forest (RF) model [43] is an ensemble learning algorithm that combines multiple decision trees to improve classification accuracy and mitigate overfitting. The model aggregates predictions from individual trees through majority voting, as expressed in the following:where is the final prediction, represents the prediction made by the -th tree, and the overall classification result is determined by the mode of these predictions. This approach enables random forest to capture complex, nonlinear relationships within the data while maintaining robustness against noise.

- (4)

- The multilayer perceptron (MLP) model [44] is a type of feedforward neural network designed to capture complex, nonlinear relationships within data by leveraging multiple hidden layers. The output of a neuron in this model is given by the following:where is the activation function (ReLU in the hidden layers), represents the weights associated with each input feature , is the bias, and is the number of input features. For binary classification, the output layer employs a sigmoid activation function, transforming the output into a probability value between 0 and 1. This value is interpreted as Y = 1 if P() > 0.5 and Y = 0 otherwise, ensuring compatibility with classification tasks. The MLPClassifier function was used with the following hyperparameters: activation: set to ‘relu’, enabling the model to capture nonlinear relationships efficiently by introducing nonlinearity in each layer.

- (5)

- The XGBoost (extreme gradient boosting) model [45] is a gradient-boosting-based ensemble learning technique that is renowned for its high predictive performance and computational efficiency, particularly when working with high-dimensional datasets. Its objective function is defined as follows:where represents the model’s learnable parameters, L is the loss function that measures the error between the true value, , and the predicted value, , and () is the regularization term that penalizes overly complex models to prevent overfitting. For binary classification, XGBoost calculates the probability, P(Y), by aggregating the outputs of multiple decision trees. These outputs, expressed as logits, are transformed into probabilities using the sigmoid function. The final class label is determined by applying a threshold: P(Y) > 0.5 corresponds to Y = 1, while P(Y) ≤ 0.5 corresponds to Y = 0.

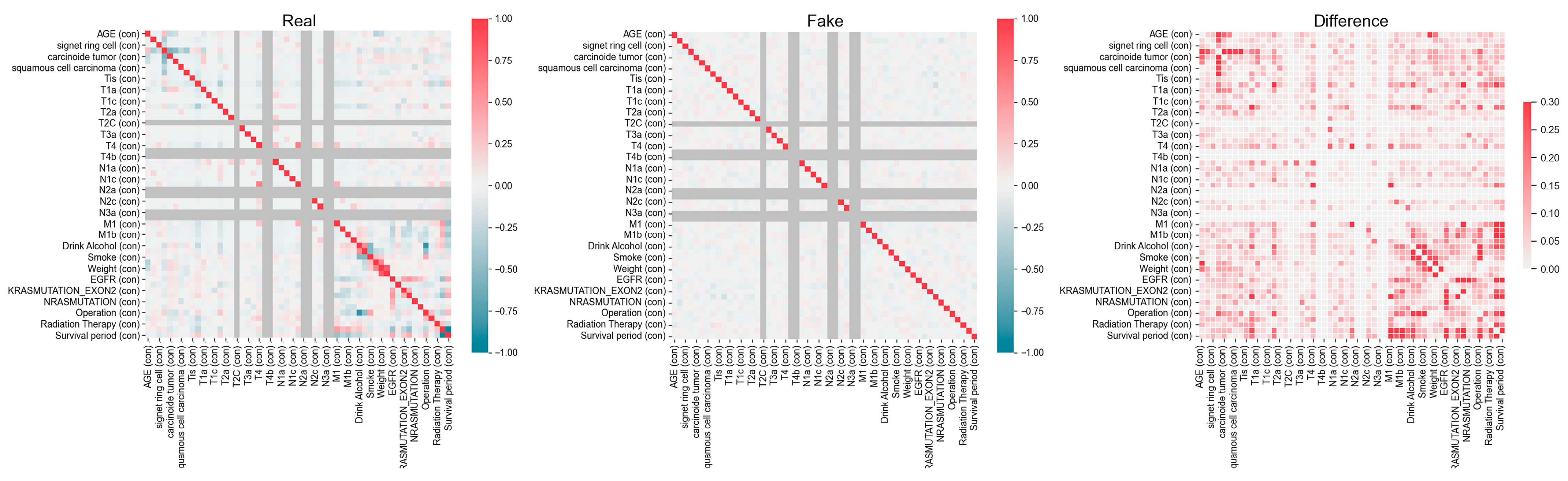

2.4. Oversampling Method

2.5. Performance Metrics

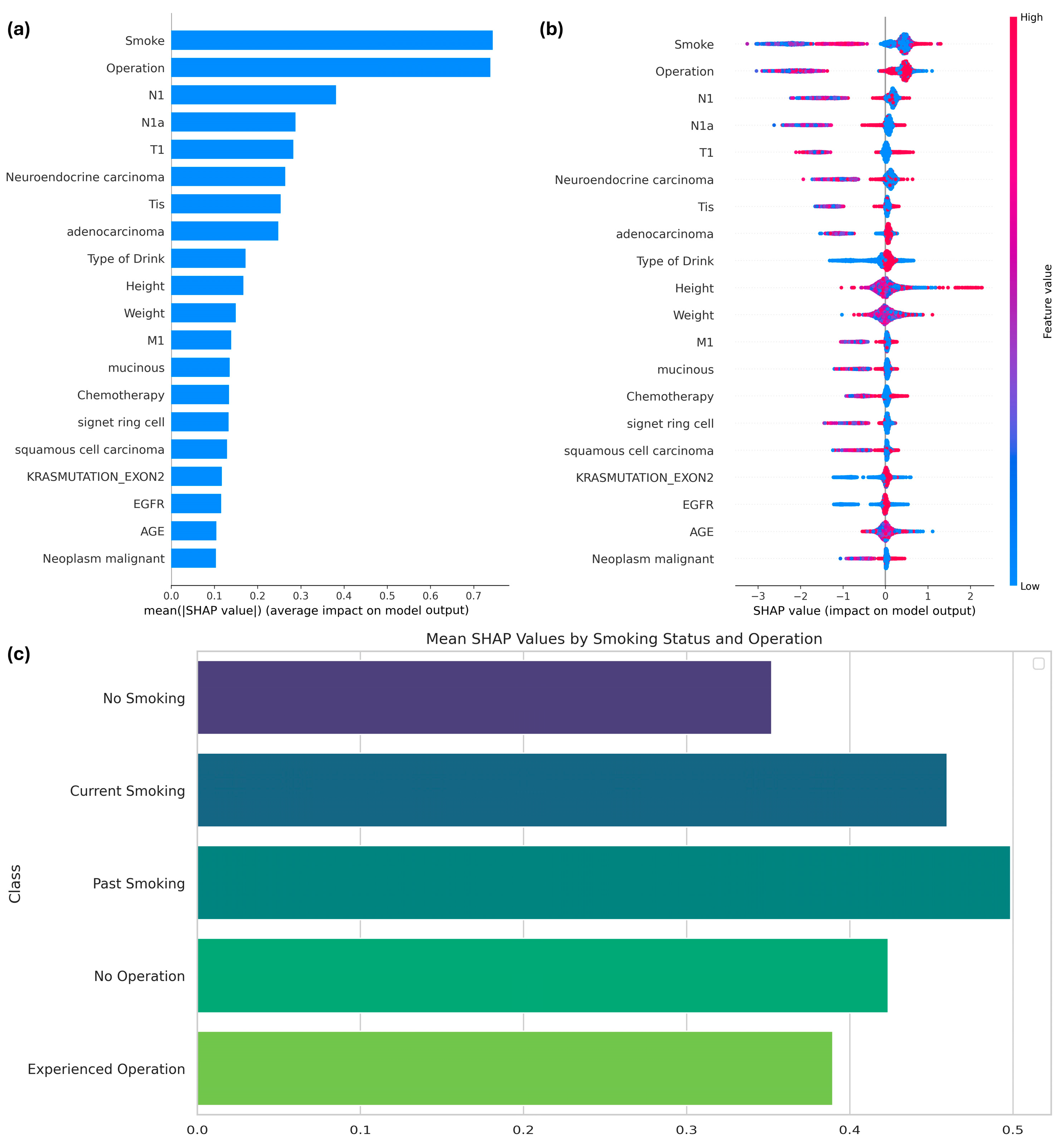

2.6. Exploring Feature Contributions via Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP)

3. Results

3.1. Model Performance

3.2. Feature Contributions via SHAP

4. Discussion

4.1. Insights and Future Studies

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Cancer Center. Annual Report of Cancer Statistics in Korea in 2020. Available online: https://ncc.re.kr/cancerStatsView.ncc?bbsn%20um=638&searchKey=total&searchValue%20=&pageNum=1 (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Kang, M.J.; Jung, K.-W.; Bang, S.H.; Choi, S.H.; Park, E.H.; Yun, E.H.; Kim, H.-J.; Kong, H.-J.; Im, J.-S.; Seo, H.G. Cancer Statistics in Korea: Incidence, Mortality, Survival, and Prevalence in 2020. Cancer Res. Treat. 2023, 55, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Goding Sauer, A.; Fedewa, S.A.; Butterly, L.F.; Anderson, J.C.; Cercek, A.; Smith, R.A.; Jemal, A. Colorectal Cancer Statistics, 2020. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dashwood, R.H. Early Detection and Prevention of Colorectal Cancer (Review). Oncol. Rep. 1999, 6, 277–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biller, L.H.; Schrag, D. Diagnosis and Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Review. JAMA 2021, 325, 669–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weeks, J.C.; Cook, E.F.; O’Day, S.J.; Peterson, L.M.; Wenger, N.; Reding, D.; Harrell, F.E.; Kussin, P.; Dawson, N.V.; Connors, J.; et al. Relationship Between Cancer Patients’ Predictions of Prognosis and Their Treatment Preferences. JAMA 1998, 279, 1709–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kather, J.N.; Krisam, J.; Charoentong, P.; Luedde, T.; Herpel, E.; Weis, C.-A.; Gaiser, T.; Marx, A.; Valous, N.A.; Ferber, D.; et al. Predicting Survival from Colorectal Cancer Histology Slides Using Deep Learning: A Retrospective Multicenter Study. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.; Ward, E.; Hao, Y.; Xu, J.; Thun, M.J. Cancer Statistics, 2009. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2009, 59, 225–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.S.; Pharm, E.Y.; Kerr, J.; Yim, Y.M.; Stepanski, E.J.; Schwartzberg, L.S. Symptom Burden & Quality of Life among Patients Receiving Second-Line Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. BMC Res. Notes 2012, 5, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanbutsele, G.; Pardon, K.; Belle, S.V.; Surmont, V.; Laat, M.D.; Colman, R.; Eecloo, K.; Cocquyt, V.; Geboes, K.; Deliens, L. Effect of Early and Systematic Integration of Palliative Care in Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, I.M.; Robinson, C.; Huq, S.; Philastre, M.; Fine, R.L. Cost Savings from Palliative Care Teams and Guidance for a Financially Viable Palliative Care Program. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 50, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Hannon, B.L.; Zimmermann, C.; Bruera, E. Improving Patient and Caregiver Outcomes in Oncology: Team-Based, Timely, and Targeted Palliative Care. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 356–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bade, B.C.; Silvestri, G.A. Palliative Care in Lung Cancer: A Review. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 37, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsuka, M.; Koyama, A.; Matsuoka, H.; Niki, M.; Makimura, C.; Sakamoto, R.; Sakai, K.; Fukuoka, M. Early Palliative Intervention for Patients with Advanced Cancer. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 43, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Temel, J.S.; Greer, J.A.; Muzikansky, A.; Gallagher, E.R.; Admane, S.; Jackson, V.A.; Dahlin, C.M.; Blinderman, C.D.; Jacobsen, J.; Pirl, W.F.; et al. Early Palliative Care for Patients with Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Li, J.; Zhou, T.; Tong, D.; Chi, S.; Kong, X.; Ding, K.; Li, J. Spatially Varying Effects of Predictors for the Survival Prediction of Nonmetastatic Colorectal Cancer. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Badisy, I.; BenBrahim, Z.; Khalis, M.; Elansari, S.; ElHitmi, Y.; Abbass, F.; Mellas, N.; EL Rhazi, K. Risk Factors Affecting Patients Survival with Colorectal Cancer in Morocco: Survival Analysis Using an Interpretable Machine Learning Approach. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manilich, E.A.; Kiran, R.P.; Radivoyevitch, T.; Lavery, I.; Fazio, V.W.; Remzi, F.H. A Novel Data-Driven Prognostic Model for Staging of Colorectal Cancer. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2011, 213, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, M.; Pasupathy, P.; Wu, X.; Recchia, S.S.; Pelegri, A.A. Multiscale Computational and Artificial Intelligence Models of Linear and Nonlinear Composites: A Review. Small Sci. 2024, 4, 2300185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrettos, K.; Triantafyllou, M.; Marias, K.; Karantanas, A.H.; Klontzas, M.E. Artificial Intelligence-Driven Radiomics: Developing Valuable Radiomics Signatures with the Use of Artificial Intelligence. BJRArtificial Intell. 2024, 1, ubae011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caie, P.D.; Dimitriou, N.; Arandjelović, O. Chapter 8—Precision Medicine in Digital Pathology via Image Analysis and Machine Learning. In Artificial Intelligence and Deep Learning in Pathology; Cohen, S., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 149–173. ISBN 978-0-323-67538-3. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, S.; Augustin, A.I.; Dunlop, A.; Sukumaran, R.; Dheer, S.; Zavalny, A.; Haslam, O.; Austin, T.; Donchez, J.; Tripathi, P.K.; et al. Recent Advances and Application of Generative Adversarial Networks in Drug Discovery, Development, and Targeting. Artif. Intell. Life Sci. 2022, 2, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, T.R.; Vinoth Kumar, V.; Muthukumaran, V.; Shashikala, H.K.; Swapna, B.; Guluwadi, S. Performance Analysis of XGBoost Ensemble Methods for Survivability with the Classification of Breast Cancer. J. Sens. 2022, 2022, 4649510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Yan, G.; Chai, B.; Hou, X. XGBLC: An Improved Survival Prediction Model Based on XGBoost. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Pan, H.; Li, M.; Qian, B.; Lin, X.; Fan, S. Predictive Model for the 5-Year Survival Status of Osteosarcoma Patients Based on the SEER Database and XGBoost Algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelke, M.S.; Deshmukh, P.R.; Shandilya, V.K. A Review on Imbalanced Data Handling Using Undersampling and Oversampling Technique. Int. J. Recent Trends Eng. Res. 2017, 3, 444–449. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, A.; Anwar, S.; Adnan, A.; Nawaz, M.; Howard, N.; Qadir, J.; Hawalah, A.; Hussain, A. Comparing Oversampling Techniques to Handle the Class Imbalance Problem: A Customer Churn Prediction Case Study. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 7940–7957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junsomboon, N.; Phienthrakul, T. Combining Over-Sampling and Under-Sampling Techniques for Imbalance Dataset. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Machine Learning and Computing, Singapore, 24–26 February 2017; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 243–247. [Google Scholar]

- Buk Cardoso, L.; Cunha Parro, V.; Verzinhasse Peres, S.; Curado, M.P.; Fernandes, G.A.; Wünsch Filho, V.; Natasha Toporcov, T. Machine Learning for Predicting Survival of Colorectal Cancer Patients. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heagerty, P.J.; Zheng, Y. Survival Model Predictive Accuracy and ROC Curves. Biometrics 2005, 61, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, Y.; Reddy, C.K. Machine Learning for Survival Analysis: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2019, 51, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourou, K.; Exarchos, T.P.; Exarchos, K.P.; Karamouzis, M.V.; Fotiadis, D.I. Machine Learning Applications in Cancer Prognosis and Prediction. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2015, 13, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerez, J.M.; Molina, I.; García-Laencina, P.J.; Alba, E.; Ribelles, N.; Martín, M.; Franco, L. Missing Data Imputation Using Statistical and Machine Learning Methods in a Real Breast Cancer Problem. Artif. Intell. Med. 2010, 50, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remontet, L.; Bossard, N.; Belot, A.; Estève, J.; French Network of Cancer Registries FRANCIM. An Overall Strategy Based on Regression Models to Estimate Relative Survival and Model the Effects of Prognostic Factors in Cancer Survival Studies. Stat. Med. 2007, 26, 2214–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, S.M.; Pocock, S.J.; Kerr, G.R. Regression Models and Non-Proportional Hazards in the Analysis of Breast Cancer Survival. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C Appl. Stat. 1984, 33, 176–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, K.A.; Kondrashova, O.; Bradley, A.; Williams, E.D.; Pearson, J.V.; Waddell, N. Deep Learning in Cancer Diagnosis, Prognosis and Treatment Selection. Genome Med. 2021, 13, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, Y.; Jin, Z.; Wu, J.; Deng, J.; Zhang, L.; Su, H.; Jiang, G.; Liu, H.; Xie, D.; Cao, N.; et al. Development and Validation of a Deep Learning Model for Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Survival. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e205842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, B.; Chen, R.-C.; Zhu, S.-Z.; Zhang, W.-W. Using Random Forest Algorithm for Breast Cancer Diagnosis. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Symposium on Computer, Consumer and Control (IS3C), Taichung, Taiwan, 6–8 December 2018; pp. 449–452. [Google Scholar]

- Hage Chehade, A.; Abdallah, N.; Marion, J.-M.; Oueidat, M.; Chauvet, P. Lung and Colon Cancer Classification Using Medical Imaging: A Feature Engineering Approach. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2022, 45, 729–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.W.; Guk, M.Y.; Kim, H.R.; Ryu, K.S.; Kong, H.J.; Cha, H.S.; Kim, H.-J.; Chae, H.; Jeon, Y.S.; Kim, H.; et al. Data resource profile: The cancer public library database in South Korea. Cancer Res. Treat. 2024, 56, 1014–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinbaum, D.G.; Klein, M. Logistic Regression, 3rd ed.; Statistics for Biology and Health; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; p. 536. ISBN 978-1-4419-1741-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rokach, L.; Maimon, O. Data Mining with Decision Trees: Theory and Applications, 2nd ed.; Series in Machine Perception and Artificial Intelligence; World Scientific Pub. Co.: Singapore, 2015; Volume 81, ISBN 978-981-4590-08-2. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Y. Random Forest for Bioinformatics. In Ensemble Machine Learning: Methods and Applications; Zhang, C., Ma, Y., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 307–323. ISBN 978-1-4419-9326-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bengio, Y.; Ducharme, R.; Vincent, P. A Neural Probabilistic Language Model. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 27 November–2 December 2000; Leen, T., Dietterich, T., Tresp, V., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; Volume 13, pp. 932–938. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling Technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Yang, N.; Qian, Z.; Zhang, G. What makes an online review more helpful: An interpretation framework using XGBoost and SHAP values. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 16, 466–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yan, C.; Gao, C.; Malin, B.A.; Chen, Y. Predicting Missing Values in Medical Data Via XGBoost Regression. J. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2020, 4, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, C.-X.; An, S.-Y.; Qiao, B.-J.; Wu, W. Time Series Analysis of Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome in Mainland China by Using an XGBoost Forecasting Model. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budholiya, K.; Shrivastava, S.K.; Sharma, V. An Optimized XGBoost Based Diagnostic System for Effective Prediction of Heart Disease. J. King Saud. Univ.—Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 4514–4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, V.; Jansen, L.; Hoffmeister, M.; Brenner, H. Smoking and survival of colorectal cancer patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 1517–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniacki, A.; Książek, W.; Mrowczyk, P. A novel approach for predicting the survival of colorectal cancer patients using machine learning techniques and advanced parameter optimization methods. Cancers 2024, 16, 3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susič, D.; Syed-Abdul, S.; Dovgan, E.; Jonnagaddala, J.; Gradišek, A. Artificial Intelligence Based Personalized Predictive Survival among Colorectal Cancer Patients. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2023, 231, 107435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Li, M.; Deng, S.; Wang, L. Hybrid Gene Selection Approach Using XGBoost and Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm for Cancer Classification. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2022, 60, 663–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, S.; Onyema, E.M.; Kumar, P.; Maryann, D.C.; Roselyn, A.O.; Obichili, M.I. A Hybrid Machine Learning Model for Timely Prediction of Breast Cancer. Int. J. Model. Simul. Sci. Comput. 2023, 14, 2341023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Feature | Training Set | p-Value | Test Set | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <6 mo. (n = 849) | >6 mo. (n = 8570) | <6 mo. (n = 198) | >6 mo. (n = 2157) | ||||

| 1 | Age | 56.98 (17.93) | 57.13 (17.98) | 0.811 | 58.33 (17.39) | 57.81 (17.91) | 0.698 |

| 2 | Mucinous | 0:665, 1:184 | 0:6913, 1:1657 | 0.111 | 0:151, 1:47 | 0:1741, 1:416 | 0.157 |

| 3 | Signet ring cell | 0:679, 1:170 | 0:6994, 1:1576 | 0.261 | 0:160, 1:38 | 0:1721, 1:436 | 0.802 |

| 4 | Adenocarcinoma | 0:211, 1:638 | 0:1908, 1:6662 | 0.092 | 0:50, 1:148 | 0:473, 1:1684 | 0.323 |

| 5 | Carcinoid tumor | 0:686, 1:163 | 0:7018, 1:1552 | 0.461 | 0:166, 1:32 | 0:1798, 1:359 | 0.941 |

| 6 | Neuroendocrine carcinoma | 0:654, 1:195 | 0:6915, 1:1655 | 0.012 * | 0:139, 1:59 | 0:1747, 1:410 | 0.000 ** |

| 7 | Squamous cell carcinoma | 0:688, 1:161 | 0:7057, 1:1513 | 0.366 | 0:155, 1:43 | 0:1755, 1:402 | 0.335 |

| 8 | Neoplasm malignant | 0:690, 1:159 | 0:7030, 1:1540 | 0.616 | 0:158, 1:40 | 0:1810, 1:347 | 0.163 |

| 9 | Tis | 0:657, 1:192 | 0:6894, 1:1676 | 0.037 * | 0:145, 1:53 | 0:1715, 1:442 | 0.047 |

| 10 | T1 | 0:685, 1:164 | 0:6972, 1:1598 | 0.666 | 0:160, 1:38 | 0:1750, 1:407 | 0.987 |

| 11 | T1a | 0:751, 1:98 | 0:7594, 1:976 | 0.937 | 0:177, 1:21 | 0:1924, 1:233 | 1.000 |

| 12 | T1b | 0:777, 1:72 | 0:7782, 1:788 | 0.531 | 0:177, 1:21 | 0:1965, 1:192 | 0.502 |

| 13 | T1c | 0:806, 1:43 | 0:8116, 1:454 | 0.835 | 0:190, 1:8 | 0:2033, 1:124 | 0.402 |

| 14 | T2 | 0:770, 1:79 | 0:7632, 1:938 | 0.158 | 0:182, 1:16 | 0:1922, 1:235 | 0.268 |

| 15 | T2a | 0:783, 1:66 | 0:7933, 1:637 | 0.770 | 0:189, 1:9 | 0:1972, 1:185 | 0.066 |

| 16 | T2b | 0:796, 1:53 | 0:8023, 1:547 | 0.931 | 0:188, 1:10 | 0:2026, 1:131 | 0.672 |

| 17 | T2C | 0:810, 1:39 | 0:8059, 1:511 | 0.122 | 0:190, 1:8 | 0:2012, 1:145 | 0.189 |

| 18 | T3 | 0:812, 1:37 | 0:8075, 1:495 | 0.103 | 0:191, 1:7 | 0:2048, 1:109 | 0.439 |

| 19 | T3a | 0:800, 1:49 | 0:8025, 1:545 | 0.550 | 0:194, 1:4 | 0:2045, 1:112 | 0.071 |

| 20 | T3b | 0:804, 1:45 | 0:7965, 1:605 | 0.063 | 0:184, 1:14 | 0:1981, 1:176 | 0.688 |

| 21 | T4 | 0:815, 1:34 | 0:8048, 1:522 | 0.017 | 0:191, 1:7 | 0:2018, 1:139 | 0.141 |

| 22 | T4a | 0:833, 1:16 | 0:8325, 1:245 | 0.123 | 0:198, 1:0 | 0:2102, 1:55 | 0.116 |

| 23 | T4b | 0:830, 1:19 | 0:8338, 1:232 | 0.485 | 0:191, 1:7 | 0:2098, 1:59 | 0.669 |

| 24 | N1 | 0:630, 1:219 | 0:6717, 1:1853 | 0.006 ** | 0:155, 1:43 | 0:1695, 1:462 | 0.994 |

| 25 | N1a | 0:714, 1:135 | 0:7350, 1:1220 | 0.205 | 0:161, 1:37 | 0:1830, 1:327 | 0.226 |

| 26 | N1b | 0:755, 1:94 | 0:7523, 1:1047 | 0.357 | 0:171, 1:27 | 0:1893, 1:264 | 0.646 |

| 27 | N1c | 0:772, 1:77 | 0:7860, 1:710 | 0.470 | 0:180, 1:18 | 0:1979, 1:178 | 0.784 |

| 28 | N2 | 0:785, 1:64 | 0:7992, 1:578 | 0.421 | 0:183, 1:15 | 0:2003, 1:154 | 0.933 |

| 29 | N2a | 0:849, 1:0 | 0:8570, 1:0 | 0.430 | 0:198, 1:0 | 0:2157, 1:0 | 0.399 |

| 30 | N2b | 0:849, 1:0 | 0:8570, 1:0 | 0.430 | 0:198, 1:0 | 0:2157, 1:0 | 0.399 |

| 31 | N2c | 0:803, 1:46 | 0:8054, 1:516 | 0.528 | 0:185, 1:13 | 0:2023, 1:134 | 0.966 |

| 32 | N3 | 0:818, 1:31 | 0:8213, 1:357 | 0.529 | 0:192, 1:6 | 0:2081, 1:76 | 0.873 |

| 33 | N3a | 0:849, 1:0 | 0:8570, 1:0 | 0.430 | 0:198, 1:0 | 0:2157, 1:0 | 0.399 |

| 34 | N3b | 0:849, 1:0 | 0:8570, 1:0 | 0.430 | 0:198, 1:0 | 0:2157, 1:0 | 0.399 |

| 35 | M1 | 0:679, 1:170 | 0:6745, 1:1825 | 0.412 | 0:143, 1:55 | 0:1714, 1:443 | 0.022 * |

| 36 | M1a | 0:707, 1:142 | 0:7230, 1:1340 | 0.434 | 0:170, 1:28 | 0:1827, 1:330 | 0.741 |

| 37 | M1b | 0:746, 1:103 | 0:7618, 1:952 | 0.398 | 0:173, 1:25 | 0:1900, 1:257 | 0.857 |

| 38 | M1c | 0:761, 1:88 | 0:7670, 1:900 | 0.948 | 0:179, 1:19 | 0:1932, 1:225 | 0.805 |

| 39 | Type of drink | 1:102, 2:223, 99:398 | 1:1091, 2:1853, 99:993, 99:4633 | 0.000 * | 1:24, 2:49, 3:26, 99:99 | 1:273, 2:469, 3:264, 99:1151 | 0.732 |

| 40 | Smoking | 0:533, 1:154, 2:162 | 0:5757, 1:1423, 2:1390 | 0.028 * | 0:113, 1:43, 2:42 | 0:1428, 1:358, 2:371 | 0.034 * |

| 41 | Height | 162.07 (10.17) | 161.58 (10.76) | 0.211 | 163.35 (9.88) | 161.89 (10.74) | 0.066 |

| 42 | Weight | 64.45 (13.85) | 64.43 (13.94) | 0.968 | 65.12 (14.17) | 64.34 (13.99) | 0.455 |

| 43 | EGFR | 1:142, 2:179, 99:528 | 1:1338, 2:1497, 99:5735 | 0.011 | 1:36, 2:32, 99:130 | 1:348, 2:376, 99:1433 | 0.722 |

| 44 | MSI | 1:159, 2:118, 3:111, 99:461 | 1:1346, 2:1201, 3:1057, 99:4966 | 0.088 | 1:35, 2:36, 3:28, 99:99 | 1:369, 2:292, 3:239, 99:1257 | 0.090 |

| 45 | KRASMUTATION_EXON2 | 1:149, 2:168, 99:532 | 1:1323, 2:1602, 99:5645 | 0.142 | 1:28, 2:49, 99:121 | 1:326, 2:392, 99:1439 | 0.076 |

| 46 | KRASMUTATION | 1:140, 2:123, 99:586 | 1:1281, 2:1167, 99:6122 | 0.320 | 1:30, 2:27, 99:141 | 1:310, 2:307, 99:1540 | 0.941 |

| 47 | NRASMUTATION | 1:189, 2:71, 99:589 | 1:1542, 2:757, 99:6271 | 0.009 ** | 1:32, 2:11, 99:155 | 1:402, 2:180, 99:1575 | 0.220 |

| 48 | BRAF_MUTATION | 1:156, 2:148, 99:545 | 1:1468, 2:1338, 99:5764 | 0.183 | 1:44, 2:38, 99:116 | 1:353, 2:316, 99:1488 | 0.011 * |

| 49 | Operation | 0:304, 1:545 | 0:2619, 1:5951 | 0.002 ** | 0:72, 1:126 | 0:661, 1:1496 | 0.113 |

| 50 | Chemotherapy | 0:663, 1:186 | 0:6758, 1:1812 | 0.634 | 0:151, 1:47 | 0:1724, 1:433 | 0.257 |

| 51 | Radiation therapy | 0:698, 1:151 | 0:6966, 1:1604 | 0.536 | 0:152, 1:46 | 0:1743, 1:414 | 0.201 |

| Model | The Best Hyperparameters Through Grid Search |

|---|---|

| LR | C = 0.001, max_iter = 1000, penalty = l2, solver = lbfgs |

| DT | max_depth = none, max_features = none, min_samples_leaf = 2, min_samples_split = 2 |

| RF | bootstrap = True, max_depth = 7, max_features = sqrt, max_leaf_nodes = none, min_samples_leaf = 1, min_samples_split = 2, n_estimators = 100 |

| MLP | activation = relu, alpha = 0.001, hidden_layer_sizes = (150, 150), max_iter = 100, solver = adam |

| XGBoost | scale_pos_weight = 0.1, learning_rate = 0.3, max_depth = 5, n_estimators = 200 |

| XGBoost (SMOTE) | scale_pos_weight = 0.5, learning_rate = 0.1, max_depth = 6, n_estimators = 200 |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR (base) | 0.49 (0.16) | 0.83 (0.02) | 0.49 (0.16) | 0.57 (0.17) |

| DT | 0.79 (0.02) | 0.84 (0.00) | 0.79 (0.02) | 0.81 (0.01) |

| RF | 0.73 (0.06) | 0.83 (0.01) | 0.73 (0.06) | 0.77 (0.04) |

| MLP | 0.88 (0.03) | 0.83 (0.00) | 0.88 (0.03) | 0.86 (0.01) |

| XGBoost | 0.79 (0.03) | 0.83 (0.00) | 0.79 (0.03) | 0.81 (0.02) |

| XGBoost (SMOTE) | 0.94 (0.09) | 0.96 (0.06) | 0.94 (0.09) | 0.94 (0.10) |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR (base) | 0.56 | 0.85 | 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.54 |

| DT | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.12 |

| RF | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.12 |

| MLP | 0.90 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.02 |

| XGBoost | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.12 |

| XGBoost (SMOTE) | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.; Cho, Y.; Kyung, Y.; Kim, E. Precision Forecasting in Colorectal Oncology: Predicting Six-Month Survival to Optimize Clinical Decisions. Electronics 2025, 14, 880. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14050880

Lee J, Cho Y, Kyung Y, Kim E. Precision Forecasting in Colorectal Oncology: Predicting Six-Month Survival to Optimize Clinical Decisions. Electronics. 2025; 14(5):880. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14050880

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jaehyuk, Youngchae Cho, Yeunwoong Kyung, and Eunchan Kim. 2025. "Precision Forecasting in Colorectal Oncology: Predicting Six-Month Survival to Optimize Clinical Decisions" Electronics 14, no. 5: 880. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14050880

APA StyleLee, J., Cho, Y., Kyung, Y., & Kim, E. (2025). Precision Forecasting in Colorectal Oncology: Predicting Six-Month Survival to Optimize Clinical Decisions. Electronics, 14(5), 880. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14050880