The Research of Relationship among Smile Developing Software, Internet Addiction, and Attachment Style

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- What attachment style do vocational school students demonstrate?

- (2)

- Can smile-developing software help improve students’ choice of attachment styles and decrease their Internet addiction

- (3)

- To what extent are vocational school students addicted to the Internet?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Attachment Style

2.2. Internet Addiction

2.3. Smile and Attachment Style

3. Research Methods

3.1. Participants

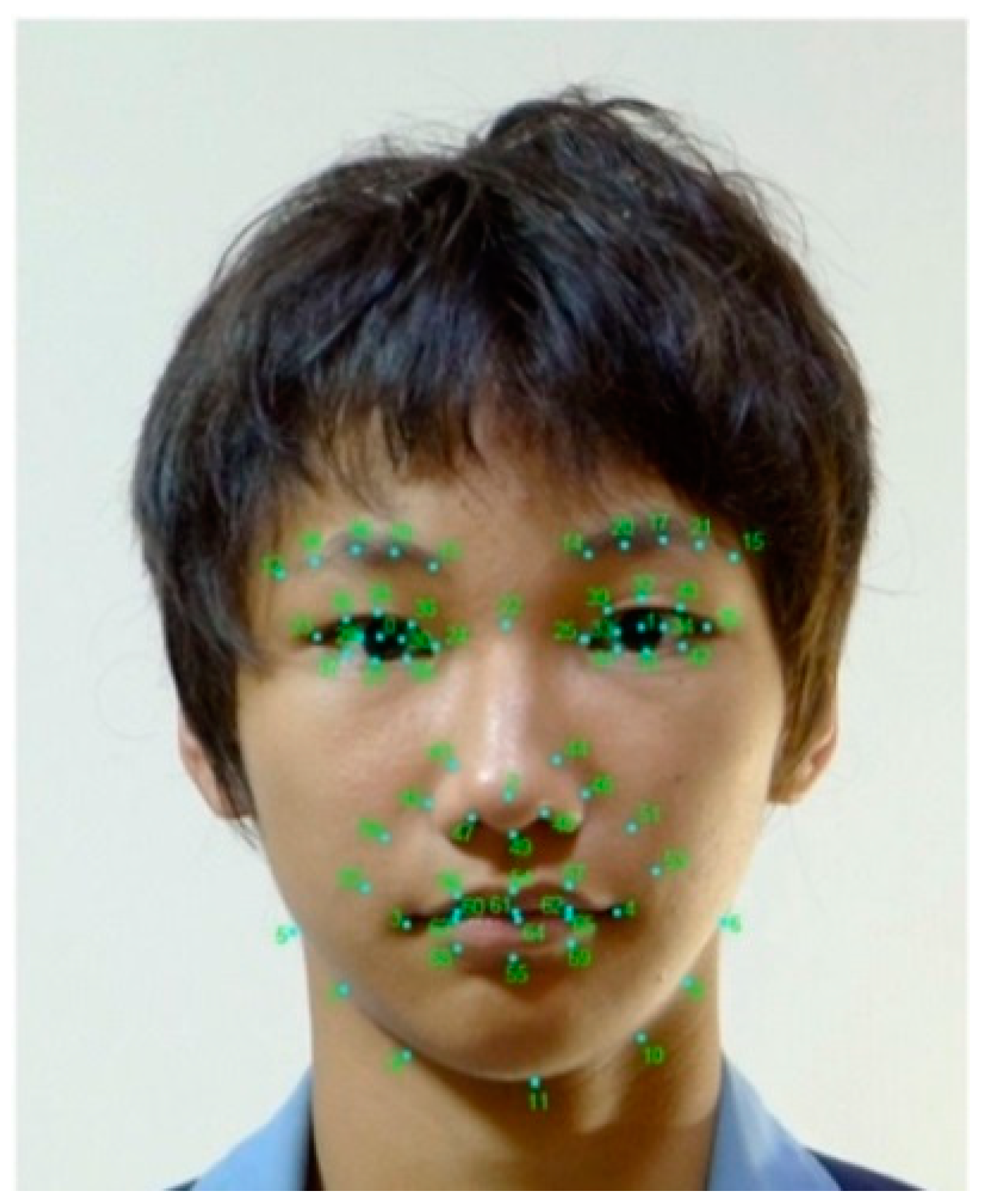

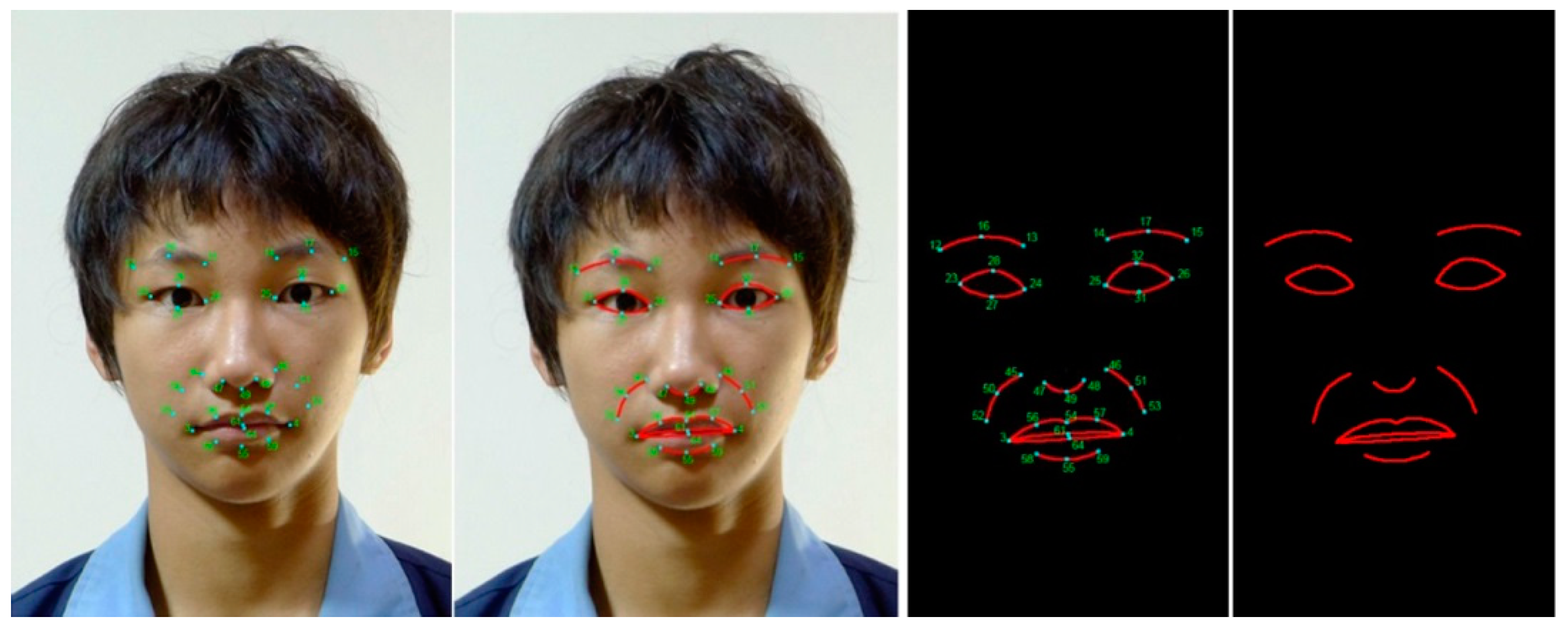

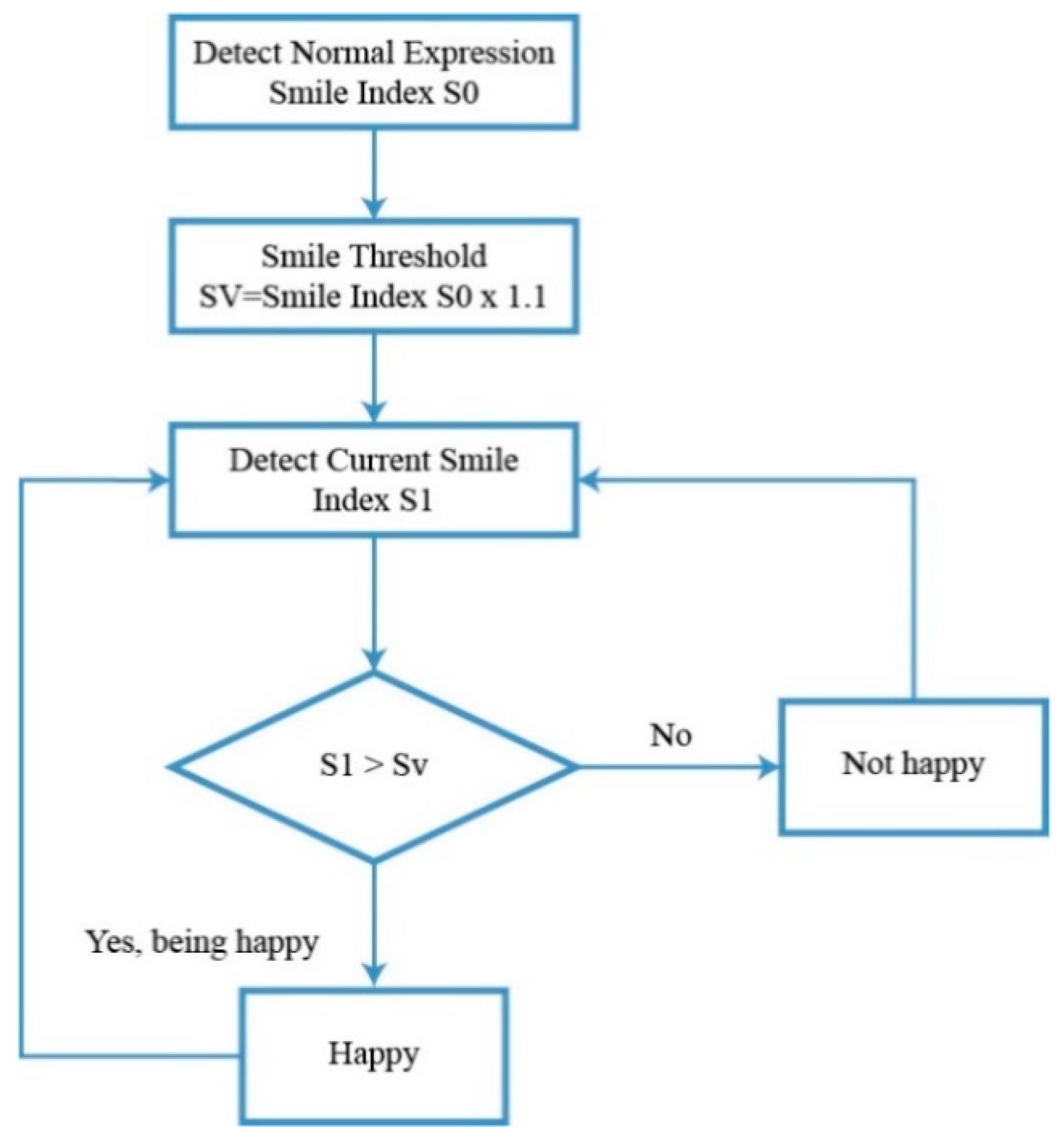

3.2. Automatic Recognition System for Facial Expressions

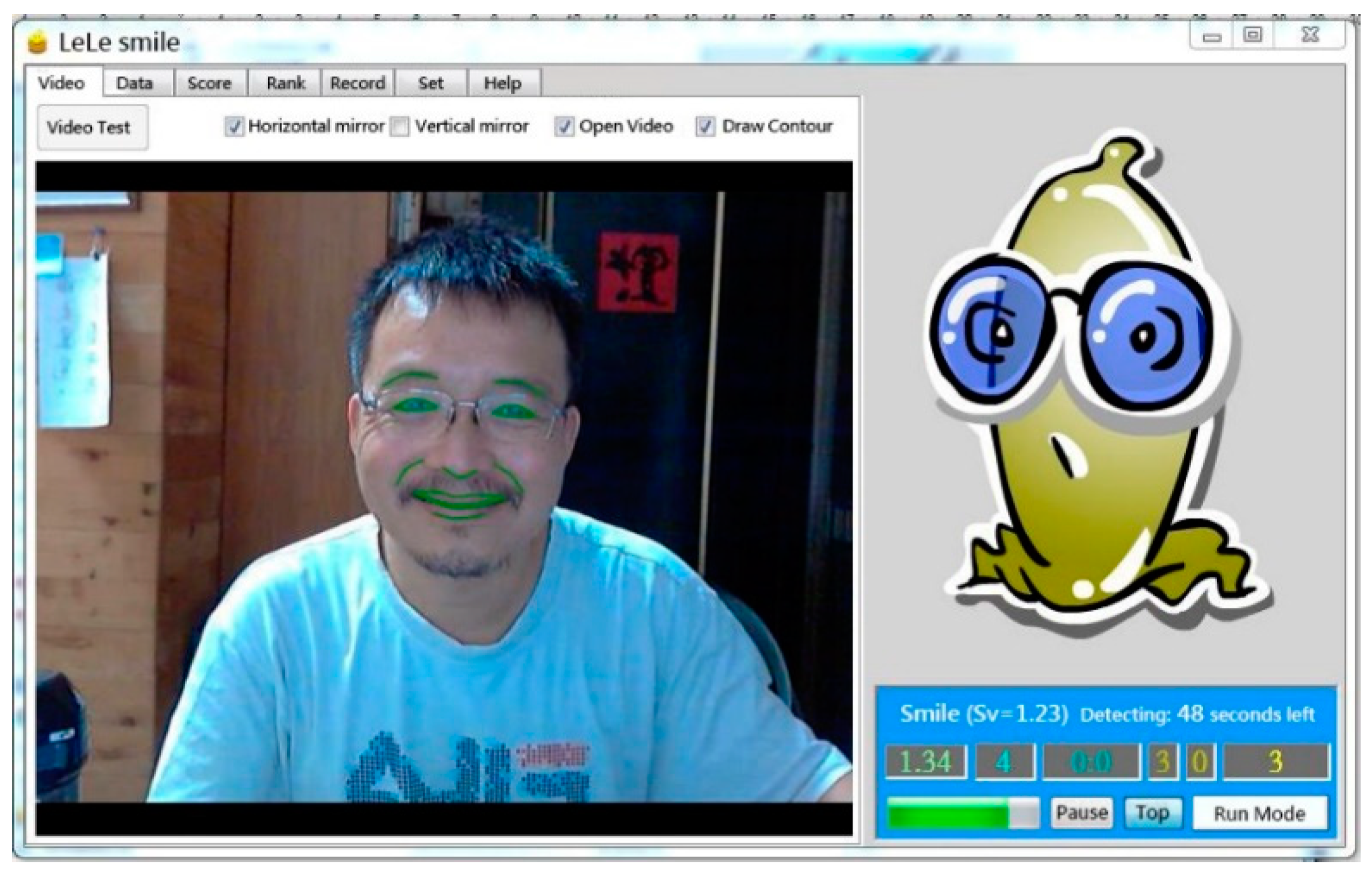

3.3. Smile Developing Software

3.4. Research Tools

3.4.1. LeLe Smile Task

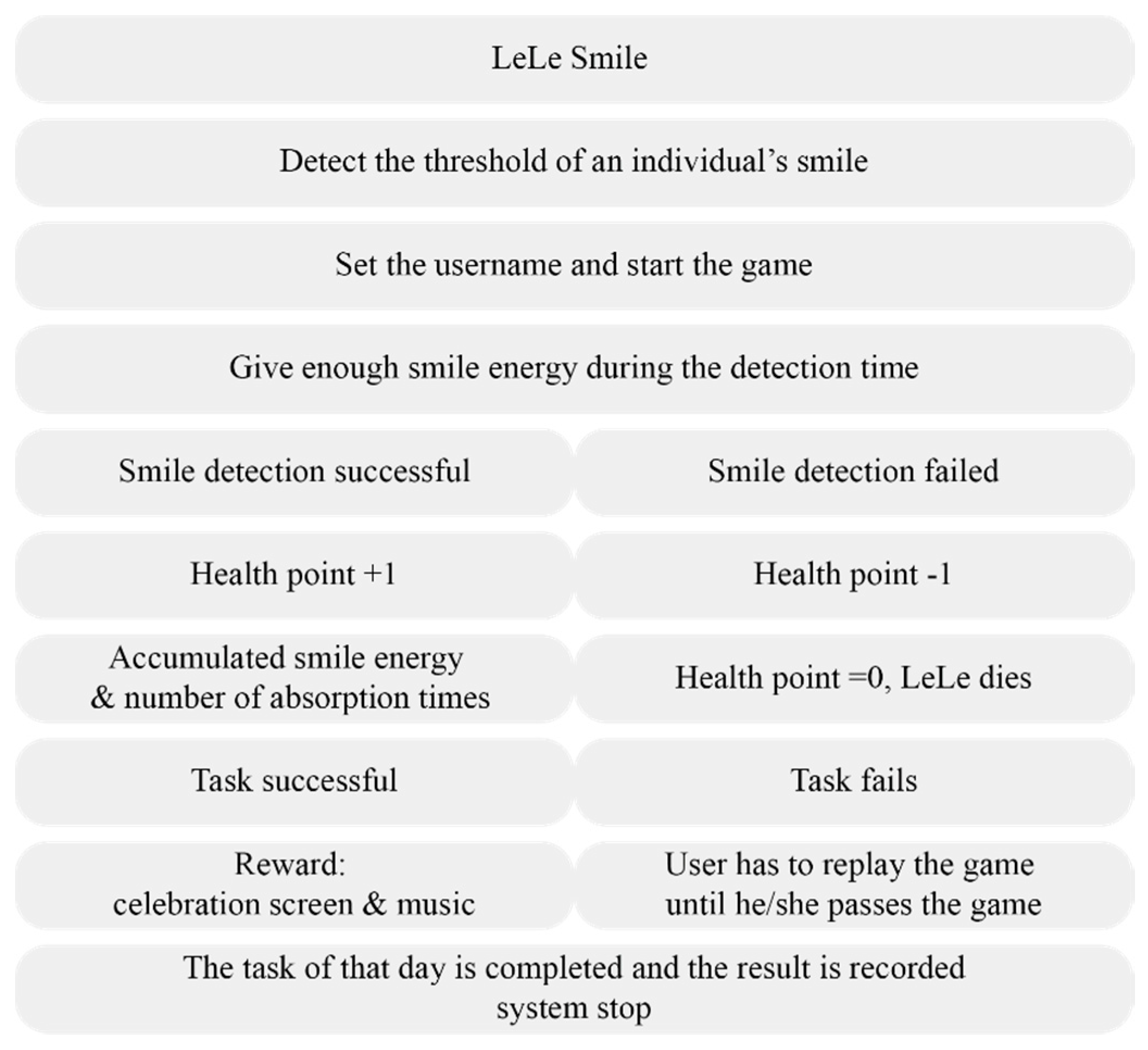

- Detect the threshold of an individual’s smile: the user takes and analyzes 10 facial images of his/her own without making any facial expressions (normal).

- Set the username and start the game: identical name as the codename on the pre- and post-test questionnaires.

- Give enough smile energy during the detection time: LeLe’s health point increases by 1 point for every successful detection, with a maximum of 3 points; LeLe’s health point decreases by 1 point for every failed detection until it reaches 0 points, which means LeLe dies and the smile task fails.

- Upon a successful completion in getting the number of absorption times of smile energy preset for the game, the program will display a celebration screen with music, and record the result and time spent at this time, so that the program operation of that day is then successfully completed.

- Once the user fails to fill up the smile energy bucket for several times and causes Lele to die, the smile task fails, for which the result will not be recorded. The user has to replay the game until he/she passes the game so that the result will be recorded and then, the program operation of that day is successfully completed

3.4.2. Interpersonal Attachment Style Scale

3.4.3. Internet Addiction Scale

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Attachment Style Scale

4.2. Internet Addiction Scale

5. Conclusions

5.1. What Is the Students’ Choice of Attachment Style?

5.2. Can Smile-Developing Software Help Improve Attachment Style?

5.3. What Is the Internet Addiction Level of Students Enrolled in the Practical Skills Program?

5.4. Can the Smile-Developing Software Reduce Internet Addiction?

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Items | Descriptions | - | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | It makes me uncomfortable to get close to people. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 2 | I find it very easy to get close to people. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 3 | Even without any close emotional ties, I still live comfortably. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 4 | I want emotional intimacy, but it’s hard to trust someone completely. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 5 | It’s very important to me to be independent and self-sufficient. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 6 | I worry that I’ll be vulnerable if I get too close to people. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 7 | I will worry that people don’t want to be with me that much. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 8 | I don’t like to depend on people. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 9 | I will worry that people don’t value me as much as I value them. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 10 | I will not worry about being alone. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 11 | It makes me uncomfortable when people get too close to me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 12 | I will worry that people don’t really like me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 13 | I rarely worry that people don’t accept me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 14 | I’d rather keep my distance from people to avoid disappointment. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 15 | I will get anxious when people want to be closer to me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 16 | I’m not satisfied with myself. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 17 | Usually I prefer to be free on my own. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 18 | I find myself always seeking acceptance and affirmation. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 19 | I know my strengths and weaknesses, and I like myself. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 20 | I often care too much about what people think of me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 21 | I’m comfortable with people depending on me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 22 | I have no problem with living by myself. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 23 | Even if people don’t appreciate me, I can still be sure of my worth. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 24 | When I need a friend, I can always find one. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Items | Descriptions | - | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I was told more than once that I spend too much time online. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 2 | I feel uneasy once I stop going online for a certain period of time. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 3 | I find that I have been spending longer and longer periods of time online. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 4 | I feel restless and irritable when the Internet is disconnected or unavailable. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 5 | I feel energized online. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 6 | I stay online for longer periods of time than intended. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 7 | Although using the Internet has negatively affected my relationships, the amount of time I spend online has not decreased. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 8 | More than once, I have slept less than four hours due to being online. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 9 | I have increased substantially the amount of time I spend online. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 10 | I feel distressed or down when I stop using the Internet for a certain period of time. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 11 | I fail to control the impulse to log on. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 12 | I find myself going online instead of spending time with friends. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 13 | I get backaches or other physical discomfort from spending time surfing the net. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 14 | Going online is the first thought I have when I wake up each morning. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 15 | Going online has negatively affected my schoolwork or job performance. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 16 | I feel like I am missing something if I don’t go online for a certain period of time. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 17 | My interactions with family members have decreased as a result of Internet use. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 18 | My recreational activities have decreased as a result of Internet use. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 19 | I fail to control the impulse to go back online after logging off for other work. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 20 | My life would be joyless without the Internet. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 21 | Surfing the Internet has negatively affected my physical health. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 22 | I have tried to spend less time online but have been unsuccessful. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 23 | I make it a habit to sleep less so that more time can be spent online. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 24 | I need to spend an increasing amount of time online to achieve the same satisfaction as before. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 24 | I fail to have meals on time because of using the Internet. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 26 | I feel tired during the day because of using the Internet late at night. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

References

- Kushlev, K.; Hunter, J.F.; Proulx, J.; Pressman, S.D.; Dunn, E. Smartphones reduce smiles between strangers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 91, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandstrom, G.M.; Rawn, C.D. Embrace chattering students: They may be building community and interest in your class. Teach. Psychol. 2015, 42, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Wang, W.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Nie, J. Succumb to habit: Behavioral evidence for overreliance on habit learning in Internet addicts. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 89, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.J.; Lopez-Fernandez, O. Internet addiction and problematic Internet use: A systematic review of clinical research. World J. Psychiatry 2016, 6, 143–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sioni, S.R.; Burleson, M.H.; Bekerian, D.A. Internet gaming disorder: Social phobia and identifying with your virtual self. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 71, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuma, N.; Watanabe, K.; Nishi, D.; Ishikawa, H.; Tachimori, H.; Takeshima, T.; Umeda, M.; Sampson, L.A.; Galea, S.; Kawakami, N. Urbanization and Internet addiction in a nationally representative sample of adult community residents in Japan: A cross-sectional, multilevel study. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 273, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chern, K.-C.; Huang, J.-H. Internet addiction: Associated with lower health-related quality of life among college students in Taiwan, and in what aspects? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 84, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Zhang, Z.; Bi, L.; Wu, X.-S.; Wang, W.-J.; Li, Y.-F.; Sun, Y.-H. The association between life events and internet addiction among Chinese vocational school students: The mediating role of depression. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 70, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.A.; Malmberg, J.; Goodell, N.K.; Boring, R.L. The distribution of attention across a talker’s face. Discourse Process. 2004, 38, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odaci, H. Academic self-efficacy and academic procrastination as predictors of problematic internet use in university students. Comput. Educ. 2011, 57, 1109–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odacı, H.; Çelik, Ç.B. Who are problematic internet users? An investigation of the correlations between problematic internet use and shyness, loneliness, narcissism, aggression and self-perception. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 2382–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, S.; Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Sadness and Depression. J. Marriage Fam. 1982, 44, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trairatvorakul, P. Patterns of Attachment. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2016, 37, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, K.; Horowitz, L.M. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A.; Bowlby, J. Attachment, 2nd ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Developmental psychiatry comes of age. Am. J. Psychiatry 1988, 145, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.F.; Lin, H.; Chang, T.J. Rating of attachment style, intimacy competency and sex role orientation. Psychol. Test. 1997, 44, 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.-H.; Lee, Y.-T.; Hsieh, S. Internet Interpersonal Connection Mediates the Association between Personality and Internet Addiction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 2019, 16, 3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nie, J.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y. Exploring depression, self-esteem and verbal fluency with different degrees of internet addiction among Chinese college students. Compr. Psychiatry 2017, 72, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M.; Black, D.W. Internet Addiction. CNS Drugs 2008, 22, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. Internet Addiction—Time to be Taken Seriously? Addict. Res. 2000, 8, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przepiórka, A.; Blachnio, A.; Cudo, A. The role of depression, personality, and future time perspective in internet addiction in adolescents and emerging adults. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 272, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longstreet, P.; Brooks, S.; Gonzalez, E. Internet addiction: When the positive emotions are not so positive. Technol. Soc. 2019, 57, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.K.; Yoshimura, M.; Murata, M.; Sato-Fujimoto, Y.; Hitokoto, H.; Mimura, M.; Tsubota, K.; Kishimoto, T. Associations between problematic Internet use and psychiatric symptoms among university students in Japan. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 72, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, C.; Lee, M.-B.; Liao, S.-C.; Ko, C.-H. A nationwide survey of the prevalence and psychosocial correlates of internet addictive disorders in Taiwan. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2019, 118, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, W.-J.; Chang, Y.-P.; Yen, C.-F. Boredom proneness and its correlation with Internet addiction and Internet activities in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2018, 34, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yılmaz, S.; Hergüner, S.; Bilgiç, A.; Işik, Ü. Internet addiction is related to attention deficit but not hyperactivity in a sample of high school students. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2014, 19, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J. Subst. Use 2005, 10, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. Internet Addiction: Does it Really Exist? In Psychology and the Internet: Intrapersonal, Interpersonal, and Transpersonal Implications; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kandell, J.J. Internet Addiction on Campus: The Vulnerability of College Students. CyberPsychol. Behav. 1998, 1, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichenberg, C.; Schott, M.; Decker, O.; Sindelar, B. Attachment Style and Internet Addiction: An Online Survey. J. Med. Int. Res. 2017, 19, e170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibeklioglu, H.; Salah, A.A.; Gevers, T. Recognition of Genuine Smiles. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2015, 17, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Geld, P.; Oosterveld, P.; Van Heck, G.; Kuijpers-Jagtman, A.M. Smile attractiveness: Self-perception and influence on personality. Angle Orthod. 2007, 77, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Connolly, K.; Smith, P.K. Reactions of pre-school-children to a strange observer. In Ethological Studies of Child Behaviour; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1972; pp. 157–172. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, D.G.; Hewitt, J. Giving Men the Come-On: Effect of Eye Contact and Smiling in a Bar Environment. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1985, 61, 873–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Mao, H.; Li, Y.J.; Liu, F. Smile Big or Not? Effects of Smile Intensity on Perceptions of Warmth and Competence. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 787–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, R.H.; Teichert, T. The effect of ad smiles on consumer attitudes and intentions: Influence of model gender and consumer gender. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.D.; Rychlowska, M.; Wood, A.; Niedenthal, P. Smiles as Multipurpose Social Signals. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2017, 21, 864–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutsch, F.M. Status, sex, and smiling: The effect of role on smiling in men and women. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 16, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinsz, V.B.; Tomhave, J.A. Smile and (Half) the World Smiles with You, Frown and You Frown Alone. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 17, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharlemann, J.P.W.; Eckel, C.; Kacelnik, A.; Wilson, R.K. The value of a smile: Game theory with a human face. J. Econ. Psychol. 2001, 22, 617–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arienzo, M.C.; Boursier, V.; Griffiths, M.D. Addiction to Social Media and Attachment Styles: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2019, 17, 1094–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ceyhan, E.; Boysan, M.; Kadak, M.T. Associations between Online Addiction, Attachment Style, Emotion Regulation, Depression and Anxiety in General Population: Testing the Proposed Diagnostic Criteria for Internet Addiction. Sleep Hypn.-Int. J. 2018, 21, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrtička, P.; Andersson, F.; Grandjean, D.M.; Sander, D.; Vuilleumier, P. Individual Attachment Style Modulates Human Amygdala and Striatum Activation during Social Appraisal. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goffman, E. On Face-Work: An Analysis of Ritual Elements in Social Interaction. Reflect. SoL J. 2003, 4, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerey, E.A.; Gilder, T.S.E. The subjective value of a smile alters social behaviour. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Luxand, Inc. Luxand FaceSDK; Luxand, Inc.: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2014; Available online: http://www.luxand.com/facesdk/ (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Tan, P.Y.; Ibrahim, H.; Bhargav, Y.; Moorthy, P.S.; Bhargav, Y.; Moorthy, P.S.; Patel, C. Implementation of band pass filter for homomorphic filtering technique. Int. J. Comput. Sci. 2013, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tome, P.; Fierrez, J.; Vera-Rodriguez, R.; Ramos, D. Identification using face regions: Application and assessment in forensic scenarios. Forensic Sci. Int. 2013, 233, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V. The Facial Action Coding System (FACS): A Technique for the Measurement of Facial Action; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, C.; Prodger, P. The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; (Original work published 1872). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.H.; Weng, L.J.; Su, Y.J.; Wu, H.M.; Yang, P.F. Development of a Chinese Internet addiction scale and its psychometric study. Chin. J. Psychol. 2003, 43, 279–294. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, C.-H.; Yen, J.-Y.; Chen, C.-C.; Chen, S.-H.; Yen, C.-F. Proposed Diagnostic Criteria of Internet Addiction for Adolescents. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2005, 193, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeef, A.S.; Faisal, G.G. Internet Addiction among Dental Students in Malaysia. J. Int. Dental Med. Res. 2019, 12, 1452–1456. [Google Scholar]

- Estevez, A.; Jauregui, P.; Lopez-Gonzalez, H. Attachment and behavioral addictions in adolescents: The mediating and moderating role of coping strategies. Scand. J. Psychol. 2019, 60, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| - | Self-Internal Model (Self Recognition) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Other’s Internal Model (Give Others Recognition) | Positive | Secure | Preoccupied |

| Negative | Dismissing | Fearful | |

| NEUTRAL | AU 1 | AU 2 | AU 4 | AU 5 |

|  |  |  |  |

| Eyes, brow, and cheek are relaxed. | Inner portion of the brows is raised. | Outer portion of the brows is raised. | Brows lowered and drawn together. | Upper eyelids are raised. |

| AU6 | AU7 | AU 1 + 2 | AU 1 + 4 | AU 4 + 5 |

|  |  |  |  |

| Cheeks are raised. | Lower eyelids are raised. | Inner and outer portions of the brows are raised. | Medial portion of the brows is raised and pulled together. | Brows lowered and drawn together and upper eyelids are raised. |

| AU 1 + 2 + 4 | AU 1 + 2 + 5 | AU 1 + 6 | AU 6 + 7 | AU 1 + 2 + 5 + 6 + 7 |

|  |  |  |  |

| Brows are pulled together and upward. | Brows and upper eyelids are raised. | Inner portion of brows and cheeks are raised. | Lower eyelids cheeks are raised. | Brows, eyelids, and cheeks are raised. |

| NEUTRAL | AU 9 | AU 10 | AU 12 | AU 20 |

|  |  |  |  |

| Lips relaxed and closed. | The infraorbital triangle and center of the upper lip are pulled upwards. Nasal root wrinkling is present. | The infraorbital triangle is pushed upwards. Upper lip is raised. Causes angular bend in shape of upper lip Nasal root wrinkle is absent. | Lip corners are pulled obliquely. | The lips and the lower portion of the nasolabial furrow are pulled back laterally. The mouth is elongated. |

| AU 15 | AU 17 | AU 25 | AU 26 | AU 27 |

|  |  |  |  |

| The corners of the lips are pulled down. | The chin boss is pushed upwards. | Lips are relaxed and parted. | Lips are relaxed and parted; mandible is lowered. | Mouth stretched open and the mandible pulled downwards. |

| AU 23 + 24 | AU 9 + 17 | AU 9 + 25 | AU 9 + 17 + 23 + 24 | AU 10 + 17 |

|  |  |  |  |

| Lips tightened, narrowed, and pressed together. | - | - | - | - |

| AU 10 + 25 | AU 10 + 15 + 17 | AU 12 + 25 | AU 12 + 26 | AU 15 + 17 |

|  |  |  |  |

| AU 17 + 23 + 24 | AU 20 + 25 | - | - | - |

|  | - | - | - |

| Attachment | Secure | Anxious-Preoccupied | Dismissive-Avoidant | Fearful-Avoidant | Total Amount | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before/After Test | Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | - | |||||||||

| Amount of people | 2 | 3 | 10 | 13 | 8 | 5 | 10 | 9 | 30 | |||||||||

| M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | |

| 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 19 | 11 | |

| Statistic of Paired Sample | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | Average | Amount | SD * | SEM * | |

| Secure | After | 17.27 | 30 | 3.676 | 0.671 |

| Before | 17.10 | 30 | 3.800 | 0.694 | |

| Anxious–preoccupied | After | 22.77 | 30 | 3.287 | 0.600 |

| Before | 23.30 | 30 | 4.284 | 0.782 | |

| Dismissive–avoidant | After | 20.47 | 30 | 5.532 | 1.010 |

| Before | 21.73 | 30 | 5.343 | 0.975 | |

| Fearful–avoidant | After | 22.07 | 30 | 4.927 | 0.899 |

| Before | 22.40 | 30 | 4.782 | 0.873 | |

| Paired Sample Correlations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | Amount | Correlation | Significance | |

| Secure | After–Before | 30 | 0.541 | 0.002 ** |

| Anxious–preoccupied | After–Before | 30 | 0.600 | 0.000 *** |

| Dismissive–avoidant | After–Before | 30 | 0.722 | 0.000 *** |

| Fearful–avoidant | After–Before | 30 | 0.753 | 0.000 *** |

| Paired Sample Test | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | Pairwise Variable Difference | t | Degree of Freedom | Significance (Two-Tail) | |||||

| Average | SD * | SEM * | 95% Difference CI * | ||||||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Secure | After–Before | 0.167 | 3.582 | 0.654 | −1.171 | 1.504 | 0.255 | 29 | 0.801 |

| Anxious–preoccupied | After–Before | −0.533 | 3.501 | 0.639 | −1.841 | 0.774 | −0.834 | 29 | 0.411 |

| Dismissive–avoidant | After–Before | −1.267 | 4.059 | 0.741 | −2.782 | 0.249 | −1.709 | 29 | 0.098 |

| Fearful–avoidant | After–Before | −0.333 | 3.417 | 0.624 | −1.609 | 0.943 | −0.534 | 29 | 0.597 |

| - | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

| Normal (S < 87) | 20 | 22 |

| Have signs of Internet Addiction () | 6 | 3 |

| High Risk () | 4 | 5 |

| Paired Sample Statistic | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | Average | Number | SD * | SEM * | |

| Total | After | 70.500 | 30 | 21.210 | 3.872 |

| Before | 73.667 | 30 | 21.085 | 3.850 | |

| Sym-C | After | 10.833 | 30 | 3.896 | 0.711 |

| Before | 10.900 | 30 | 4.213 | 0.769 | |

| Sym-W | After | 13.233 | 30 | 5.144 | 0.939 |

| Before | 14.800 | 30 | 5.222 | 0.953 | |

| Sym-T | After | 11.900 | 30 | 3.916 | 0.715 |

| Before | 12.767 | 30 | 3.664 | 0.669 | |

| RP-IH | After | 19.667 | 30 | 5.441 | 0.993 |

| Before | 20.000 | 30 | 5.994 | 1.094 | |

| RP-TM | After | 12.067 | 30 | 5.085 | 0.928 |

| Before | 12.367 | 30 | 3.943 | 0.720 | |

| Paired Sample Correlation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | Number | Correlation | Significance | |

| Total | After and Before | 30 | 0.855 | 0.000 *** |

| Sym-C | After and Before | 30 | 0.678 | 0.000 *** |

| Sym-W | After and Before | 30 | 0.920 | 0.000 *** |

| Sym-T | After and Before | 30 | 0.787 | 0.000 *** |

| RP-IH | After and Before | 30 | 0.734 | 0.000 *** |

| RP-TM | After and Before | 30 | 0.693 | 0.000 *** |

| Paired Sample Test | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | Pairwise Variable Difference | t | Degree of Freedom | Significance (Two-Tail) | |||||

| Average | SD * | SEM * | 95% Difference CI * | ||||||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Total | After–Before | −3.167 | 11.387 | 2.079 | −7.419 | 1.085 | −1.523 | 29 | 0.139 |

| Sym-C | After–Before | −0.067 | 3.269 | 0.597 | −1.287 | 1.154 | −0.112 | 29 | 0.912 |

| Sym-W | After–Before | −1.567 | 2.079 | 0.380 | −2.343 | −0.790 | −4.127 | 29 | 0.000 *** |

| Sym-T | After–Before | −0.867 | 2.488 | 0.454 | −1.796 | 0.0622 | −1.908 | 29 | 0.066 |

| RP-IH | After–Before | −0.333 | 4.205 | 0.768 | −1.903 | 1.237 | −0.434 | 29 | 0.667 |

| RP-TM | After–Before | −0.300 | 3.687 | 0.673 | −1.677 | 1.077 | −0.446 | 29 | 0.659 |

| No. | Score | Sym-C | Sym-W | Sym-T | RP-IH | RP-TM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | After | 103 | 20 | 21 | 18 | 24 | 20 | Increase |

| Before | 93 | 21 | 20 | 15 | 23 | 14 | ||

| 2 | After | 97 | 20 | 17 | 15 | 26 | 19 | Increase |

| Before | 95 | 18 | 21 | 15 | 27 | 14 | ||

| 3 | After | 109 | 25 | 23 | 17 | 24 | 20 | Lower |

| Before | 114 | 23 | 25 | 17 | 33 | 16 | ||

| 4 | After | 94 | 17 | 22 | 14 | 24 | 17 | Lower |

| Before | 96 | 21 | 22 | 13 | 24 | 16 | ||

| 5 | After | 96 | 17 | 19 | 19 | 24 | 17 | Lower |

| Before | 99 | 21 | 18 | 19 | 22 | 19 | ||

| 6 | After | 100 | 18 | 19 | 18 | 27 | 18 | Lower |

| Before | 120 | 23 | 23 | 22 | 32 | 20 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, H.-C.K.; Tsai, M.-C.; Wu, K.-H. The Research of Relationship among Smile Developing Software, Internet Addiction, and Attachment Style. Electronics 2020, 9, 2057. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics9122057

Lin H-CK, Tsai M-C, Wu K-H. The Research of Relationship among Smile Developing Software, Internet Addiction, and Attachment Style. Electronics. 2020; 9(12):2057. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics9122057

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Hao-Chiang Koong, Meng-Chun Tsai, and Kuang-Hsiang Wu. 2020. "The Research of Relationship among Smile Developing Software, Internet Addiction, and Attachment Style" Electronics 9, no. 12: 2057. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics9122057