1. Introduction

Market globalization granted enormous power to Multinational Corporations (MNCs), whose influence keeps growing in international politics (Ordeix-Rigo, 2009 [

1], Molleda, 2011 [

2]), in parallel to their contribution to the GDP of the countries where they invest. (Today, however, the COVID-19 pandemic is “a supply, demand and policy shock for Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)”, the recent UNCTAD’s -United Nations Conference on Trade and Development- World Investment Report 2020 states. FDI flows are forecast to decrease by up to 40% in 2020 from their 2019 value of

$1.54 trillion; this would bring FDI below

$1 trillion for the first time since 2005. In addition, FDI is projected to decrease by a further 5% to 10% in 2021 and to initiate a recovery in 2022, the report says.) Yes, MNCs’ impact is bigger today, but so are the responsibility and risks, especially in an international business environment that is less predictable, more volatile, and involves more politics than in previous decades (Bolewski, 2019) [

3]: the COVID-19 world health crisis, Brexit, China’s state capitalism, the new populisms in Europe, cyberattacks, terrorism, or fake news are a few examples within an international arena where MNCs become more vulnerable to geopolitical risks (Van der Putten, 2018) [

4]. In this new reality, companies perceive clear signs that a new corporate mindset is vital to operate in the global environment, since their social role as economic agents is transitioning into a parallel role as

political and

social agents: MNCs and their CEOs have entered the diplomatic arena (Ruël, 2020) [

5], where corporate legitimacy (“social license to operate”), and stakeholder management become crucial elements for the survival of international businesses. This means that the most successful MNCs will be those that make expertise in international affairs central to their operations, those that internalize many elements traditionally applied by governments, and improve their ability to operate in the global market by means of what scholars have labeled as Corporate or Business Diplomacy. However, what is exactly corporate diplomacy, and how does it work? Do MNCs manage their political, social, and cultural influence abroad, strategically and autonomously? If that is the case, does this not turn these political and social agents into some sort of nation-state? What types of corporate diplomacy instruments can be distinguished? The purpose of this paper is to analyze and clarify these questions.

The Need of a Mindset Change vs. Today’s Reality

Doing business internationally is a complex process nowadays (Ruël, 2020: 2) [

5], especially taking into account that the competitive landscape can be deeply transformed by unexpected shifts in the non-market. These shifts have been traditionally linked with the technological environment, in which the theory of dynamic capabilities was first developed; dynamic capabilities were originally conceived as “the foundation of enterprise-level competitive advantage in regimes of rapid (technological) change” (Teece, 2007) [

6] (p. 1341), where performance, Research and Development (R&D), or innovation were highlighted as drivers of competitive advantage. In fact, and with the purpose of coping with fast-changing business environments, companies are opening up their organizational boundaries to tap into external sources of knowledge, giving rise to increasing and updated research on the open innovation concept (e.g., Yun et al., 2018, 2019, 2020a, 2020b) [

7,

8,

9,

10], which will be further discussed later in this paper.

However, the competitive landscape can be transformed not only by new entrants with new technologies but also by myriad stakeholders outside the economic value chain (Henisz, 2016: 184) [

11] (p. 184), particularly in foreign (geo) political and social spheres. As a consequence, the drivers of competitive advantage, particularly in emerging markets (Sawyerr, 1993) [

12], often relate to the technological environment, as well as to the political and social environment. The cases of Spanish oil company Repsol in Argentina -where Repsol’s subsidiary YPF was expropriated by former president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner in 2012- and construction firm Sacyr -which launched arbitration proceedings claim in 2018 against the Panamanian state before the UN’s Commission on International Trade Law as part of a cost-overrun dispute regarding the expansion of the Panama canal- are well-known examples within the Spanish imaginary of political risks affecting MNCs operations abroad. Could Repsol not anticipate the expropriation of its assets in Argentina once it had invested millions of dollars in capital in the ground? A positive answer to this question would require an enhanced ability to understand not only the impact of changes in technology but also the stakeholder environment on organizational strategy (Henisz, 2016: 185) [

11] (p. 185). Thus, and as a result of the current international economic and political context, MNCs would need to develop new strategies to operate in foreign markets. Because some things have changed (Egea et al., 2017) [

13]:

- (1)

The quality of the information that the company receives daily in overwhelming amounts and that must be filtered in a coordinated manner with intelligence instruments that allow it to read the “signals” in the non-market environment as well as anticipate potential conflicts.

- (2)

The

context in which to compete for positioning and benefit, which is no longer located only in the marketplace, but also in the

political arena and in the

host society. This requires knowing and getting involved with the external stakeholders as well as trying to influence them. In fact, Henisz (2016) [

11] considers engagement of external stakeholders as a dynamic capability. In this new context, the

management of perceptions gains importance, because:

- (a)

It requires that companies, especially those with an important impact in the host country, acquire new institutional roles in order to gain a perception of legitimacy and to increase their competitive advantage.

- (b)

The added value is no longer created only for customers and shareholders but also for society; in order to be able to develop it in the long term, a perception of good reputation is necessary to have opinion leaders and other stakeholders become favorable to the company.

- (3)

The reaction and response time, not only due to the rapid advances in the new ICT (Information and Communication Technologies), but also to the increasing uncertainty and the interconnection of geopolitical events happening daily.

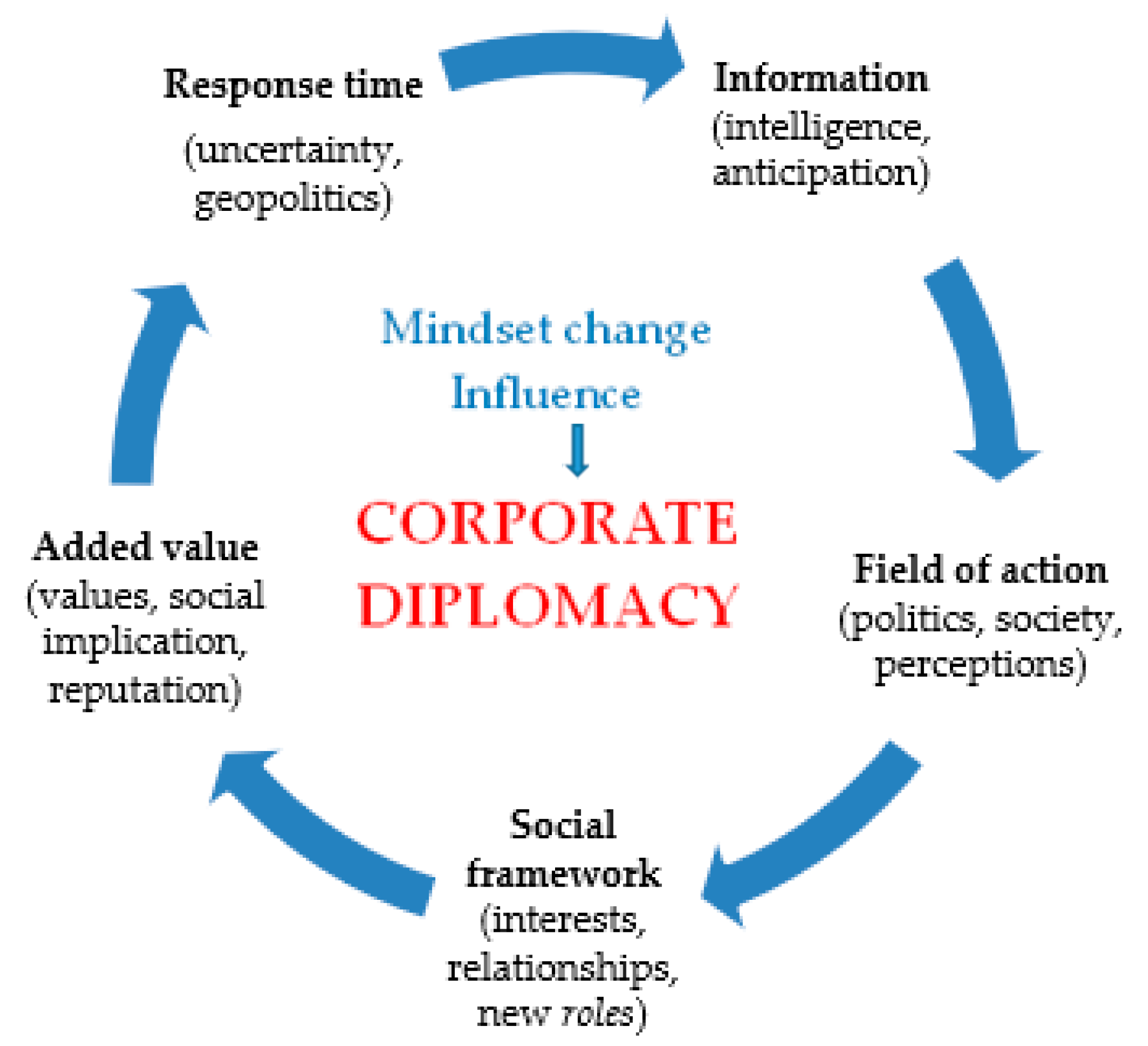

For all the above, if an MNC wants to change its mindset and bet for the strategic management of influence through corporate diplomacy, it should act on the mentioned five vectors (

Figure 1). But is this really happening? MNCs do not have the legal authority to sign international treaties. However, some of them are indeed making international affairs central to their operations. In the past few years, while nation-states are gradually losing their monopoly over international affairs due to the proliferation of new agents in the political, cultural, or defense spheres, many MNCs have started to extend their social power and influence, and, thereby, they are achieving a status as institutions within their host society; this search for symbolic power is linked to the strategic bet on corporate diplomacy by these companies [

1]. According to Ordeix-Rigo and Duarte (2009) [

1], in the process of satisfying expectations from multiple stakeholders, “corporations are taking some of the roles that have been generally associated with governments because the scope of their dimension means that their political surroundings (the sphere of all those affected by the corporation’s decisions) are comparable in dimension and economic or social power” [

1] (p. 556).

This happens, for example, when MNCs assume security in international waters or represent their own interests directly before international regulatory bodies, world economic forums, and foreign governments, establishing bonds that were the monopoly of the state in the past to obtain a “social license to operate” in foreign countries. It also takes place when MNCs establish contact with international partners on their own, without the intervention of their state of origin, as in November 2017, when the president of Spanish Bank Santander Ana Botín met with former Argentinian president Mauricio Macri to announce a

$550M investment in technology for the term 2018–2020. Botín is an example of a CEO who acquires a role that transcends that of the mere manager or strategist to become almost a stateswoman. In this sense, Camuñas (2012) [

14] states that, nowadays, the highest representative of a company “plays a role much more political and visible” (Camuñas, 2012) [

14] (p. 113). On the other hand, it is worth highlighting how some MNCs are assuming social development roles in local markets, thus gaining their trust, acquiring an institutional role there and, with it, a competitive advantage with respect to those that cannot, or do not know how to, get involved in this type of strategy. For example, Spanish MNC Telefónica, with powerful interests in Latin America, takes advantage of traditional Spanish diplomacy with the

Proniño program, which contributes to eradicating child labor and until 2013 had served 471,848 children and adolescents in Latin America. Likewise, the

ProFuturo program, promoted by Fundación Telefónica and Fundación Bancaria “la Caixa”, was created in 2016 to bring digital education to children from vulnerable environments. By the end of 2017, this initiative had benefited 5.8 million children in 23 countries in Latin America, Africa, and Asia.

As noted, corporate diplomacy emerges as a reaction to a new cross-border social framework. In this context, business success responds to a combination of market conditions with non-market elements and agents for whom transparency, social commitment, or protection of the environment, among other elements, are important for mutual trust. Therefore, it is vital for an MNC to manage political influence in order to obtain a social license to operate in the host country and provide more value to the company.

2. Literature Review: Defining Corporate Diplomacy

Corporate diplomacy is a social phenomenon derived from classical diplomacy, dynamic, in the process of consolidation, which grows within the framework of relationships of a different nature. It has barely received attention in disciplines such as business organization, corporate strategy (Asquer, 2012) [

15], or international relations (Van Willigen, 2020 [

16]; Westermann-Behaylo et al., 2015) [

17], and its sub-fields of foreign policy analysis and international political economy. Most of the existing literature on corporate diplomacy derives from tangential disciplines such as communication, marketing, advertising or PR, which does not mean that MNCs do not develop activities to manage their “diplomatic” relations with other companies and entities abroad; to refer to them, instead, different terms such as public relations, collaborative contacts, corporate social responsibility Asquer (2012) [

15] or institutional relations are often used. For that reason, it is not easy to delimit a corporate diplomacy concept in the world of MNCs. Corporate diplomacy is not a new concept, either, if we take into account that Christian A. Herter [

18], former managing director of the Department of Government Relations at Socony Mobil (today ExxonMobil), used this term in 1966 when indicating that American corporate diplomacy had two indisputable objectives: “first to establish the kinds of relationships abroad—private, public and governmental—that not only enhance the chance of commercial success but are essential to its achievement; second, and here corporate and political diplomacy are virtually indistinguishable, to build an enduring feeling of good will for the United States, its people, its economic system, its business organizations, its political institutions, and the validity of its culture in a world that daily grows more complex” (Herter, 1966) [

18] (p. 409). However, in the past two decades—perhaps as a consequence of the strong internationalization process of companies, derived from the free-market capitalism trends from the 1980s that opened the economies to a rapidly globalized world—there has been increasing interest in corporate diplomacy, with authors such as Strange (2000) [

19]; Steger (2003) [

20]; Saner and Yiu (2003) [

21]; Saner and Yiu (2005) [

22]; Watkins (2007) [

23]; Ordeix-Rigo (2009) [

1]; Asquer (2012) [

15]; Kesteleyn and Riordan (2014) [

24]; Henisz (2014) [

25]; Riordan (2014) [

26]; White (2015) [

27]; Westermann-Behaylo et al. (2015) [

17]; Egea (2016) [

28]; Ruël and Wolters (2016) [

29]; Mogensen (2017) [

30]; Egea, Parra, and Wandosell (2017) [

13]; and Bolewski (2018) [

31] being sources of its main definitions, objectives and evaluation methods.

In 2000, Strange [

19] argued that new forms of diplomacy arising from changes in the international economy had altered relations between states and MNCs (Strange, 2000) [

19] and between companies themselves, MNCs having become influential actors in transnational relations. Ruël and Wolters (2016) [

29] enhance Strange’s idea and believe that corporate diplomacy (they call it “international business diplomacy”) covers the representation and communication activities deployed by international businesses with host government representatives and non-governmental representatives in order to establish and sustain a positive relationship to maintain legitimacy and a “license to operate”. In this sense, Henisz (2014) believes corporate diplomacy “creates real business value” (Henisz (2014) [

25] (p. xii) when it occurs in the context of the companies’ external search for wealth, where business, politics, and society collide. This Wharton professor believes that value for shareholders and society is increasingly created and protected through the strategic integration of functions related to stakeholders, such as governmental affairs, stakeholder relations, sustainability, community relations, or corporate communications, and that it is necessary to raise corporate diplomacy to the executive level, providing it with sophisticated management tools, so that MNCs generate value. Thus, he defines it as “[…] the ability to win the hearts and minds of external stakeholders in support of an organizational mission. As compared to the narrow support function of external affairs, corporate diplomats play a central role not just in sensing risks and opportunities in the external environment, but also in shaping short- and long-term strategic responses across all functions of their organizations” (Henisz, 2016) [

11] (p. 183).

On the other hand, the authors of [

1] focus their notion of corporate diplomacy on business–society relations, studying how it contributes to enhancing the legitimacy and influence of corporations that operate abroad and must adapt to the host community. They argue that the challenges a company faces to be accepted abroad have changed and that MNCs have managed to adapt well, to the point that “when investing in corporate diplomacy, corporations are looking to take new roles in society” [

1] (p. 556), in particular of an institutional type. They also state that MNCs have undergone an evolutionary process that has made one of its most important assets its “ability to obtain a ‘license to operate’ by matching the expectations of numerous stakeholders” [

1] (p. 554), in a world where bad business practices have undermined confidence in MNCs. This represents a broad change in business logic that moves from a company model based on the shareholders to another more focused on the stakeholders, and therefore for these authors, corporate diplomacy “clearly becomes a valid way for organizations to extend their social power and influence and thus achieve their status of institutions within society.” [

1] (p. 557). For White (2015) [

27], corporate diplomacy and, in turn, the status that MNCs obtain as institutions, recognize that private corporations can both act for their business and profit-oriented interests and, at the same time, use their resources and increasing power to address broader social and political concerns.

As noted above, then, current literature on corporate diplomacy understands it in terms of its relationship with foreign societies. However, its function within international business management is increasingly linked to traditional state diplomacy, and therefore to the foreign policy functions of nation-states, especially when conceived as “the soft power of society, […] the diplomacy of citizens, of companies and of organizations, complementary to the diplomacy of the States” (Oliver, 2010) [

32] (p. 59), or as “a complementary instrument to the work of classical diplomacy developed by the States” (Camuñas) [

14] (p. 17). Westermann-Behaylo et al. (2015) [

17] go further on this and consider that corporate diplomacy “incorporates an MNE’s short-term and longer-term policies and activities to reduce political tensions within a host country, efforts separate from any official diplomatic and political efforts of the MNE’s home country government. (2015: 388) [

17] (p. 388). In line with this idea of MNCs as diplomatic actors, Egea (2016) [

28] and Egea, Parra, and Wandosell (2017) [

13] introduce in their definition different key concepts such as corporate foreign policy, institutional role, influence management, or mechanisms of state diplomacy, somehow equating corporate diplomacy strategies with functions that are the domain of state diplomatic services: “Corporate diplomacy is an instrument framed in a corporate foreign policy that promotes environments favorable to the interests of the company through the effective management of their political influence and their involvement in the host society, thanks to mechanisms of state diplomacy that grant them an institutional role and greater legitimacy to operate, which translates into a competitive advantage.” Likewise, Bier and White (2020) [

33] see corporate diplomacy as a component of cultural diplomacy, which in turn acts as the soft power engine of a state’s public diplomacy.

As can be seen from this literature review, the different conceptual approaches to corporate diplomacy follow a line centered on the management of relationships as a critical element for the acquisition and development of influence. Without diminishing the importance of networking, in our opinion, corporate diplomacy is not a corporate policy based solely on managing relationships with third parties, but a variety of techniques or means designed to implement corporate external policies that, beyond their greater or lesser consistency with national interests, need to have other instruments that provide the company with diplomatic know-how. In other words, a more complete and transversal approach to corporate diplomacy is needed.

Research questions

RQ1: What is corporate diplomacy, and what is the existing level of knowledge about it in Spain?

RQ2: Which corporate diplomacy instruments can be distinguished?

RQ3: When turning into political/social actors abroad, are MNCs assuming the role of nation-states?

3. Materials and Methods

Corporate diplomacy is an emerging discipline in Spain. Therefore, this contribution has applied a qualitative Focus Group (FG) technique as a methodological tool in order to conduct a preliminary exploration of an under-researched area (Tynan and Drayton, 1988: 5) [

34] (p. 5). In traditional FG interviews, a small sample of respondents discusses elected topics as a group for approximately one or two hours, and a moderator focuses the discussion onto relevant subjects in a non-directive manner. However, for this paper, the FG had an online format, thanks to the collaboration of the Innovation Center for Collaborative Intelligence in Madrid, and the company Dontknow, which allowed the use of their

Collaboratorium platform. The online format made it possible to:

Have participants located at various parts of the world;

Have less inhibited and more proactive participants; and

Lower the cost compared to usual in-person group sessions.

Following the considerations from Tynan and Drayto (1988) [

34], Merton (1990) [

35], and Krueger [

36], two groups of nine components were made up, so that they could both guarantee the participation of all their components and assure a diversity of perspectives: FG (1)

Corporate diplomacy researchers and promoters, who provided theoretical and practical perspectives; and FG (2)

Corporate diplomacy executive actors, who provided perspectives from high MNCs and state-diplomacy representatives. The respondents were contacted directly, by phone or e-mail. After having confirmation of their participation in the FG, we sent them an e-mail where we attached a letter and a dossier, where we explained how the process would take place and how the

Collaboratorium digital platform worked (both in English and Spanish).

According to Tynan and Drayton (1988) [

34], FG offers substantial benefits, in terms of the quality and nature of data collected, over more familiar techniques (1988: 8), since it offers a social context that enables participants to interact with each other by sharing and reflecting on each others’ experiences and ways of working. On this occasion, the purposes were to deepen the importance of non-market strategies through the exchange of ideas and opinions from experts in business internationalization, as well as to generate new knowledge on corporate diplomacy. The number of questions included in the FGs was based on Krueger (2000) [

36] and Stewart and Shamadasani (1990) [

37], who propose a number lower than ten or twelve, respectively. Due to the flexibility of the online format, it was considered reasonable to use a total of six questions or

challenges (as labeled in the Collaboratorium platform) over a period of 14 days, around two areas (

Table 3): Influence in foreign markets and corporate diplomacy. The six challenges posed were:

4. Results

4.1. Challenge 1: Do You Believe that MNCs Manage Properly, and in An Autonomous Way, Their Political, Social, and Cultural Influence in External Markets?

(a) In Focus Group 1

Predominant opinions refer to the great interest of MNCs for results and short-term business, rather than those non-trade or non-market issues. For example, two participants believe that MNCs “remain too focused on the bottom line. They think bolt-on CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) strategies are sufficient [and] do not understand the need for autonomous and interacted strategies for the analysis and management of geopolitical risk (e.g., Non-commercial)”, because they usually assume that their country of origin will rescue them when the time comes, or that “a couple of retired diplomats on the board will cover it”. One of the participants believes that this lack of interest in the autonomous management of their influence is particularly characteristic of the Spanish MNCs, which “lack a broader vision, not understanding in full the real impact (positive/negative) of non-commercial topics”, while the MNCs of American origin “[…] do have a real understanding and care about being a responsible ‘corporate citizen’ with rights and obligations. This is why they not only promote a non-commercial approach, but in some cases (US companies) consider interaction and support to public authorities a standard in the interest of the companies.”

Another respondent thinks that MNCs do not have much help from Spanish public institutions, because some, such as ICEX, are still focused on a rational choice analysis, forgetting non-market strategies. This opinion is shared by another participant who believes Spanish institutions “don’t get the analysis and management of geopolitical risk, including the Foreign Ministry, which prefers nation-branding to foreign policy!”

On the other hand, another member of the group, a State Commercial Technician, with more than thirty-five years of experience, believes that MNCs can count, at first, on the help of public institutions such as ICEX, to manage autonomously and adequately, its influence, being able later to “design their own policy in each of the markets.” Finally, another participant distinguishes between the particular role of the MNCs and that of the institutions, so that, while the former will “always take care of their private interests and find their own way according to their financial needs”, the latter—those which are not governmental, like Chambers of Commerce—“do not have a direct role in the drafting and adoption of laws and regulations that affect companies, [but] they will be able to lobby in an attempt to achieve laws that favor business.”

(b) In Focus Group 2

One of the participants posits that Spanish MNCs do manage their political, social, and cultural influence abroad, although “it is only within the reach of the largest and with the most history to do it properly and autonomously.” However, he also considers “very useful the support of public institutions to reinforce the message and in turn, take advantage of the management of MNCs for others who start doing it.” Another expert confirms that Spanish MNCs manage their influence, although their capacity for autonomy in said management “will be determined by the size of the company and the country in which they operate”, since, in his opinion: “In good times and boom times, and if their size allows it, [Spanish MNCs] do without any assistance from public authorities. That is a generic corporate policy. Only and to the extent that its strength to position itself in a market is not enough, then it will make use of public-private cooperation.”

On the other hand, another respondent believes Spanish MNCs continue paying for their youth and inexperience when compared to foreign MNCs “that have many decades of advantage over us and that, in this time, have learned to develop an action towards the outside that is not just based on the product or service they offer.” He considers that to complete this change of business mindset, Spanish MNCs need to make “a change of paradigm […] that should lead them precisely to become aware of the need to influence the environment in which they work.” This idea was synthesized by another participant who stated that “[…] the Spanish company does not have internalized the value of non-market”, noting that there is a pending change of strategy on the part of the State to adapt its instruments and mechanisms to the current game and market conditions to give MNCs the support they need.

4.2. Challenge 2. Which Instruments Are Most Important to Exert Effective Influence in the Pursuit of Economic and Trade Objectives?

The two groups agree that, among the options proposed by the authors, the most important is networking, consisting not only in having good public relations skills, but also an agenda of high-level and key contacts, acquired through years of work. However, one of the experts clarifies that it is not necessary to focus only on them, because “in the world of digital diplomacy, lower level stakeholders can also do damage!” FG 1, as a whole, believes that competitive intelligence (CI), corporate reputation, and lobbying follow in order of importance corporate diplomacy, while FG 2 believes that order is slightly altered, with corporate reputation occupying the second place, followed by competitive intelligence and lobbying.

4.3. Challenge 3. Do MNCs Assume Nation-State Roles to Gain Competitive Advantage?

(a) In Focus Group 1:

For one of the respondents, it is clear that large corporations “assume the roles of the State, being in many cases directly proportional to the size and geographic dispersion of the MNC.” Another participant endorses this point of view when stating that “some corporations, among them some Spanish ones, do adopt the roles of the State”, although when it comes to Spanish companies, it tends to be in the context of Corporate Social Responsibility, since they “are slow when it is time to adopt more proactive roles in other areas, for example, geopolitical risk management or global issues diplomacy.” Two different participants consider MNCs as players in the international arena on the same level as the state representatives, but a third one qualifies that idea by stating that “assuming the roles of the State must undoubtedly be an objective of any company that aspires to be a MNC, although the concept of the role of the State is subject to interpretation.” On the other hand, another expert questions this comparison by stating that “some may consider that […] in the framework of Corporate Social Responsibility, a company that builds a school acquires the role of Ministry of Education, but companies act to promote their interests and even the public good as they understand it, although they do not replace the state function.”

(b) In Focus Group 2

In this FG, one participant believes that companies do not adopt nation-state roles. “What has changed is the intensity of that relational role […], these activities of relationships and influence have multiplied due to the ever-increasing internationalization of the world”, he says, and adds that “in no case, the objective of corporate diplomacy should be to exercise a State role, in the sense of equating it in terms of power in the country of destination, nor adopt the identity or functions of the State of origin.” However, another expert states that what the MNCs do look for is to generate reputation and influence in the perceptions of the stakeholders in the host country, determinants for the success of the businesses because “they do not assume a state role; it is a perception of the countries in which they operate and it is inevitable that they identify the company as such.”

4.4. Challenge 4. What Does Corporate Diplomacy Mean to You?

It is important to note that participants in both Focus Groups distinguish corporate diplomacy from those consolidated management functions in the MNCs, such as International and Institutional Relations, Public and Government Affairs, etc. and describe it as a function that aims to cover the demands of the non-market, whose features, as Bach and Allen (2010) [

38] note, must be present in any planning of a company: information, coalitions, coherence, uncertainty, and values. However, each group adds different nuances, as seen in

Table 4 and

Table 5.

(a) In Focus Group 1

Out of the eight descriptions collected, up to four experts maintain that corporate diplomacy‘s objectives are: providing information to the company; helping manage the uncertainty caused by the presence in foreign markets; and fostering coalitions with key stakeholders in the host country (

Table 4).

(b) In Focus Group 2

The eight corporate diplomacy characterizations provided in FG 2 are more complete, because they address in a more or less similar way all the features demanded by the non-market, covering “information” in four of them, while “relationships and coalitions”, “coherence and values”, and “management of uncertainty” are covered in three of them (

Table 5). However, there are two other experts who describe corporate diplomacy as “a simple mechanism of interest management, so that companies could apply it”, and as “one of the basic functions of a corner office in any MNC.”

4.5. Challenge 5. Can DC Functions and Procedures Equate Nation-State’s Diplomatic Variations in the MNCs External Action?

Of the participants in the two Focus Groups, 69.3% argue that they are not comparable. Thus, one of the experts indicates that “neither the objectives nor the tools are the same”, although in the different answers there are some nuances about their complementarity, goals, and procedures.

(a) Complementarity

A businessperson and professor states that they cannot be equated, because “it is not the same to represent a State as to represent a company, regardless how important it may be”, although he acknowledges that, in functional terms, there can be many similarities. This idea is also endorsed by two diplomats: one of them states that “they are not comparable because they move in different frequencies, but they are two sides of the same coin”; the second diplomat believes that they are “not comparable, but complementary”, since “companies from a given country would compete abroad with their rivals in other countries at a disadvantage if they did so without the assistance of the Economic Diplomacy of their country. And vice versa: political weight and influence capacity of a given State on the international scene will be greater if its companies abroad enjoy prestige and reputation of reliability, obtaining large international contracts, and acting in the world according to the guidelines of transparency and good governance that inspire the performance of the State to which they belong.”

Another expert deepens that idea by saying that they are “complementary factors [that] should coexist, but not be considered at the same level”, something to which another participant responds that “in the debates on international regulation—e.g., the OTT (Over-The-Top) internet services or climate change —the MNCs have very real interests to promote, something that many do now directly or not through their governments.” So MNCs and States can be equated “in some things (such as discussions on international regulation, […] but not in others (geopolitics).” This same participant assures that corporate diplomacy must adapt the techniques and mentality of the diplomat to the needs of the company: “Thus networks of influence and information and coalition building will replace the blunter tool of lobbying. Public diplomacy (creating a political and social environment favorable to specific proposals) will replace marketing. Digital diplomacy tools will be introduced.”

(b) Purposes

Another expert argues that “companies can reproduce some of the angles of state diplomacy”, although “the main difference is that MNCs defend a private interest and their interpretation of the environment may differ from the State´s interest.” The example with which he argues is the annexation of Crimea by Russia: state diplomacy continues to believe that the occupation was illegal, while companies “simply adapted to Russian regulations (labeling and others) to continue selling.” The matter of whether the aims of the State and the MNCs are equal or not is scattered, depending on the profile of the participants. For example, one of the diplomats states that both actors are different, although he encourages the public sector to “assimilate corporate diplomacy instruments, especially regarding procedures and information technologies.” However, on the other hand, a former politician notes that “they are not comparable, although sometimes their goals are the same.”

(c) Procedures

One respondent understands that both functions can be similar, although the procedures cannot be the same: “There is a basic difference between the company´s corporate diplomacy and the diplomatic activity of the State: the latter is related to other States on an equal footing while the company is related to institutions or stakeholders that represent either a State or interests that the company wants to bring closer to its own interests. [Regarding procedures] There will be cases in which you can see more aggressiveness from the company compared to what a State would do, and vice versa.”

4.6. Challenge 6. What Structures Should Companies Create to Manage Their Influence Capacity and Make it Effective on the Ground?

Both Focus Groups agree that, out of the five alternatives proposed, the best one is to have a transversal department that coordinates corporate diplomacy activities, among others, and they indicate as their last option the creation of a corporate diplomacy Executive Committee in the Board of Directors. One of the participants believes that a change of mindset in the executives is necessary so that the directors of companies understand that “they are corporate diplomats” and that corporate diplomacy “is not something extra, but it is blended into the strategies and operations of a corporation.” However, another expert states that this change has already been made and that these transversal structures are already created in companies. The two Focus Groups do differ in the composition of the rest of the ranking:

- (a)

In FG 1, the creation of a Corporate Diplomacy Department comes in second place, although one of the experts points out that the danger of this option is to consider corporate diplomacy as an extra option, since, according to him, “corporate diplomacy strategies should knock down silos, and not create new ones.” In third place, they consider that no space should be created within the structure, because they understand that the current system works well; finally, this group, made up of researchers and representatives of Chambers of Commerce and ICEX, leaves in fourth place the option of MNCs having an institutional representation (non-trade) outside their country.

- (b)

In FG 2, the existence of an institutional representation (non-trade) outside of Spain to take care of corporate diplomacy comes in second place, while the creation of a Corporate Diplomacy Department comes in third place; lastly, the members of this group believe that no space should be created within the structure, since they consider that the current system works well.

4.7. Findings

After a content analysis of the individual and group responses within these Focus Groups, it is clear that beyond their economic resources, MNCs need four critical components to implement a strategic management plan based on corporate diplomacy that can help them acquire and develop influence (

Table 6): the collection and analysis of information through

intelligence; the development of

networks with external stakeholders; the management of

corporate reputation—and of perceptions; and the management of public affairs with regulators through

lobbying actions, spearhead of corporate diplomacy in the representation and defense of business interests in key decision-making centers. Despite the order in which

Table 6 is presented, both FG agree that, among the options proposed by the authors, the most important corporate diplomacy instrument is networking, consisting not only in having good public relations skills, but also an agenda of high level and key contacts, acquired through years of work.

As can be inferred, the selection of these four tools considers not only the opinion of the Focus Groups experts included in this paper, but also the consulted literature and analysis of the functions and features of corporate diplomacy by various researchers and the framework for the creation of non-market strategies by Bach and Allen (2010) [

38], which should be part of the overall corporate diplomacy strategy of companies that operate abroad or intend to do so. Until now, these tools have been studied and/or applied separately at both universities and business schools, as well as in MNCs; therefore, some of their functions are often repeated or overlapped. This is the reason why an integrated relationship of these four tools is required for the analysis of corporate diplomacy. Therefore, it should be noted here that, although they do not exactly correspond to each of them, these tools take as a reference the main state diplomacy functions according to the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations (1961): representation, protection of interests, negotiation, information, enhancement of cooperation relations, and the four most relevant diplomatic functions for the State, according to Vilariño (2011) [

39]—observation, information, representation, and negotiation (

Figure 2).

Thus, the key corporate diplomacy tools would be the following:

- (a)

Competitive intelligence: the starting points of good corporate diplomacy are the deep knowledge of the non-market environment where the company operates, and the positive relationships with key stakeholders. To accomplish them, MNCs need to use competitive intelligence tools to create influence and information networks among those actors -governmental or not- which shape and inspire the company’s political risk environment on a specific market. Such analysis would help the company to outline an appropriate design of the strategy that should be led by the company’s executives.

- (b)

The management of relationships with host stakeholders: these constitute a key instrument for the application of corporate diplomacy. It is therefore vital to configure or achieve, through the hiring of professionals with specific profiles -MNCs tend to hire former politicians, ministers and/or diplomats- a Business Diplomatic Agenda (BDA); in other words, a list of executive contacts similar to those of the Chambers of Commerce or the states diplomatic corps, which consolidates the corporate diplomacy strategy and the future of the business in the medium and long term.

- (c)

The management of corporate reputation: relational capital represents the strength and loyalty of the company’s links with its stakeholders. Its effective management is necessary to obtain a series of favorable perceptions from strategic audiences, especially from governments and public administrations in their role as regulators. It is essential to manage corporate reputation before even implementing strategies based on the power of influence to cope with the growing demand—especially in foreign markets—for transparency, values, and social commitment.

- (d)

Lobbying: the strategy of representation and defense of the interests of the company through lobbying actions must be based on the three previous pillars because, although in international business it is important to have economic resources, as previously noted, one cannot have influence without strategic information, networks of contacts and reputation.

5. Discussion

The analysis of the results obtained from the Focus Group challenges covers the triple objective of the present article. Thus, with regard to What is corporate diplomacy, and what is the existing level of knowledge about it in Spain?, here, it has been verified that corporate diplomacy is known and clearly distinguished from other similar functions within the company; nevertheless, it is admitted that, in the case of Spanish MNCs, there is still a long way to producing this paradigm shift that evidences the need for companies to influence the environment in which they operate if they want to obtain the “social license to operate” abroad. In particular, 73.3% of the participants in both Focus Groups consider that MNCs, especially the Spanish ones, do not manage their political, social, and cultural influence in foreign markets in an autonomous way, due to their lack of interest, their limited capacity to do it, or the reduced institutional help. The arrival of corporate diplomacy to Spanish MNCs is, therefore, somewhat delayed. Likewise, Spanish MNCs have the notion of adopting institutional roles in foreign markets, although more frequently in a Corporate Social Responsibility context.

With regards to the second objective,

Which corporate diplomacy instruments can be distinguished?, in the “Findings” section it was shown that the most important tools to exert influence and, therefore, the most necessary ones to implement corporate diplomacy strategies, are networking with external stakeholders, competitive intelligence, management of corporate reputation, and lobbying actions. Authors like Ruël (2020) [

5] recently developed a “Business Diplomacy Instruments Matrix” that distinguishes four types of instruments along two axes: public instruments vs. private; one-on-one dialogue instruments vs. group dialogue instruments. In general, the participants in our two Focus Groups, while assuming that the political, social, economic, or cultural uncertainty in the host country is the highest risk for business internationalization, identify corporate diplomacy as a strategic tool, focused on functions which are similar to three of the four more relevant diplomatic functions to the State, according to Bach and Allen (2010) [

38]: observation and analysis, information, and representation. In their opinion, its purpose is to obtain influence in the host country through the information obtained and the establishment of trust relationships with key stakeholders. The fourth relevant diplomatic function indicated by Vilariño (2011) [

39] -the capacity to negotiate to favor the company´s interests abroad- is only explicitly referenced in four of the sixteen descriptions provided. This may have happened because in Spain, lobbying is still to be regulated. These four corporate diplomacy tools should be used as a whole in those contexts when/where it is more needed, such as when there is disagreement or conflict with non-business counterparts (Ruël, 2020: 5) [

5]; in countries with developing regulations or political/social instability; or in environments with complex decision systems, such as the European Union. The lack of coordination or synergies, and exchanges of information will undoubtedly reduce the potential of corporate diplomacy to bring an institutional and foreign policy vision to the traditional “trade” or “economic vision” of the MNC in international markets. In this respect, it is important to remember that, even though today there are departments in MNCs that often include functions related to corporate diplomacy—e.g., Intelligence, Institutional Relations, Public and Government Affairs, Communications, Legal, etc.—it is not clear whether these units or functions emerge in order to accomplish the aforementioned mindset change or if they do so as a limited reaction to negative or unexpected events. In accordance with this idea, Henisz (2016) [

11] highlights the “limitations imposed by the traditional organization of government affairs, public affairs, communications, community affairs, and sustainability” (2016: 184). Without coordination or synergies among the four corporate diplomacy tools, MNCs’ foreign policy would be limited, therefore, to a strategy of institutional relations that can apply some of these instruments separately. However, if transversality is applied, the MNC will be betting on enhancing its legitimacy and acquiring the social license to operate.

On the other hand, with regard to the third objective,

When turning into political/social actors abroad, are MNCs assuming the role of nation-states?, the Focus Group technique here applied suggests that corporate diplomacy arises under the new maps of influence generated by powerful MNCs that assume similar functions to those of the nation-states and coexist with other types of diplomacy, such as state or political, public, and commercial (Egea, Parra, and Wandosell, (2017) [

13]. This is in line, for example, with the fact that government entities, non-profit organizations, political think tanks, and academics have endorsed corporations’ participation in public diplomacy (Bolewski, 2019 [

3]; White, 2015 [

27]). The majority of participants in both Focus Groups agree that MNCs assume, in a certain way, the role of the nation-states and have a great influence on decision-making in the host country. However, some believe that the scope of this action may be limited by

The impossibility of replacing the State of the host country in its functions;

The importance of the sector to which the MNC is devoted, or its intervention in several sectors at the same time; and

A specific context, e.g., when the enormous size of the MNC can match its power to that of the State in a small destination country, or in situations where the host country has a complex regulatory framework and high political volatility.

In fact, 69.3% of respondents in the two Focus Groups argue that corporate diplomacy functions and procedures are not comparable to those of a nation-state; “neither the objectives nor the tools are the same”, one expert says, while another one states that what some MNCs are putting into action in host countries is a complementary variety of diplomacy, but at a different level to the State in terms of procedures and purposes, with less weight and influence and fewer interlocutors, because, according to him, “without defining the company´s position as one of inferiority, we must not forget at any time that the MNC is a guest in the countries in which it operates.” He adds that what MNCs do look for is generating reputation and influence in the perceptions of stakeholders in the host country, determinants for the business success because “they do not assume a state role; it is a perception of the countries in which they operate and it is inevitable that they identify the company as such.” This is in line with Bolewski’s (2018) [

31] definition of corporate diplomacy as “a business approach and management practice of influence. Its main goal is to strategically manage stakeholders’ conception of the corporation” (2018: 125) [

31].

Discussion about ‘Corporate Diplomacy and Cyclical Dynamics of Open Innovation’

In addition to disciplines such as business organization, corporate strategy, IR, or PR, corporate diplomacy can be connected also to the open innovation concept. Open innovation means, on the one hand, the use of external knowledge sources to accelerate internal innovation and, on the other hand, the use of external paths to reach the internal knowledge market (Chesbrough, 2006) [

40]. Yun et al. (2018) [

7] have expanded this concept by conceiving open innovation as an economy model where the combination of technology and the market or society contributes to generating entrepreneurial cyclical dynamics. Open innovation dynamics would have two layers, according to Yun et al., 2019 [

8]: (1) open innovation micro-dynamics -that is, open innovation–complex adaption–evolutionary change (OCE) dynamics- and (2) open innovation macro-dynamics -that is, market open innovation–closed open innovation–social open innovation (MCS) dynamics). This model expands and updates, in turn, Schumpeter’s dynamics of open innovation in the context of the 21st-century capitalism; i.e., it suggests different innovative systems that match Schumpeter’s opinions on conglomerate innovation and closed innovation. For example, the Closed Open innovation system, where “big businesses basically choose closed innovation such as internal R&D, but open innovation such as M&A (Mergers & Acquisitions) or partnership with SMEs (Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises)” (Yun et al., 2018: 1156) [

7] (p. 1156).

In order to relate corporate diplomacy to entrepreneurial cyclical dynamics of open innovation, firstly it is crucial to remember that many MNCs are transcending their traditionally economic role to become also political and social agents in foreign markets, where they meet with governments or high-level politicians, among other stakeholders groups, as direct interlocutors. In this respect, Yun et al. (2018) [

7] highlight that cooperative efforts between governments and conglomerates are required to foster and sustain market open innovation, which is produced by a new combination […] of technology and markets (2018: 1171) [

7] (p. 1171). Thus, in the realm of open innovation and the technological environment, these cooperation efforts may be interpreted as the use of external knowledge sources to accelerate internal innovation, while in the realm of corporate diplomacy, this cooperation may recognize an MNC’s willingness to look outside for solutions, for example, to a project’s political and social problems in a specific country. Hence, the connection between corporate diplomacy and open innovation may have a starting point in one of the former’s main instruments: engagement of external stakeholders. In fact, Henisz (2016) [

11] establishes explicit parallels between the technological environment—in which the theory of dynamic capabilities (Teece’s definition of dynamic capabilities on p. 2 of this paper.) was first developed—and the stakeholder environment, by stating that engagement of external stakeholders

is a dynamic capability. If we bear in mind that enterprises with strong dynamic capabilities are intensely entrepreneurial (Teece, 2007) [

6], it could be inferred that those applying corporate diplomacy strategies have strong dynamic capabilities, and, in turn, contribute to generate entrepreneurial cyclical dynamics; however, these assumptions should, of course, be tested.

On the other hand, culture is another element in common between corporate diplomacy and open innovation. Scholars and practitioners have acknowledged the growing role of corporations as social actors and as non-state actors in promoting cultural understanding (Bier and White, 2020) [

33]. For White (2015) [

27], internationalized companies engage in business practices that promote understanding of national values through cultural exchanges and sponsorships as well as an array of other activities which contribute to a nation’s public diplomacy. At the same time, a cultural perspective on open innovation that values outside competence and know-how is crucial for open innovation practices, because opening up the innovation process starts with a mindset (Katz et al., 1982) [

41]. It is not strange, then, that authors such as Carayannis and Campbell (2011) [

42] bring up the

open innovation diplomacy (OID) concept that encompasses the concept and practice of bridging distance and other divides (cultural, socioeconomic, technological, etc.) with focused and properly targeted initiatives to connect ideas and solutions with markets and investors ready to appreciate them and nurture them to their full potential. According to them, OID qualifies as a new and novel strategy, policy-making, and governance approach in the context of the quadruple and quintuple innovation helices (2011: 328) [

42] (p. 328).

Today, in the so-called fourth Industrial Revolution, the dynamics of open innovation are rapidly increasing, giving rise to a context where the requirement to understand culture, which can control open innovation dynamics, is being augmented (Yun et al., 2020: 1–2) [

9] (pp. 1–2). In this respect, it is important to highlight that corporate diplomacy has a direct positive effect on firm performance with regard to soft or nonfinancial indicators (knowledge sharing, reputation, company image, and marketing possibilities) (Ruël and Suren, 2018) [

43], where cultural understanding should also play a crucial role in helping companies exert influence, anticipate potential threats, and/or seize opportunities in the host countries.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Implications

This contribution has highlighted the potential of corporate diplomacy to bring an institutional and foreign policy vision to the traditional “trade” or “economic vision” of the MNC in international markets and turn it into competitive advantage through the implementation of four instruments or functions which are similar to relevant diplomatic functions to the State: networking with external stakeholders, competitive intelligence, management of corporate reputation, and lobbying actions. The authors of this paper believe that the coordination and synergies among these functions would enhance corporate diplomacy potential and would end up transcending the traditional functions that currently manage external relations within MNCs.

Secondly, it is interesting to note the importance given by participants in this paper to the scope of perceptions when operating in other countries. It is in this realm that executives feel more comfortable agreeing that MNCs assume the state diplomacy, although from a private interest. In our opinion, these elements can give rise to different research lines focused on MNC branding or reputation, on the type of MNC’s soft power or public diplomacy, or on the need for MNCs and nation-states to coordinate when defending national policies in other countries. For example, corporate diplomacy recently proved to be more efficient than state diplomacy during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, as long as European MNCs have managed to bring personal protection equipment (PPE) to their home countries faster than both the governments of the most affected countries and their public diplomacy networks. This shows that MNCs may assume, somehow and in specific situations, the role of a nation-state in foreign markets.

6.2. Limits and Future Research Topics

As we mentioned earlier, the coordination and synergies among the four corporate diplomacy functions or instruments shown in this paper would enhance corporate diplomacy potential and would end up transcending the traditional functions that currently manage external relations within MNCs. In this respect, further research and case studies are needed to test these assertions.

On the other hand, it would be interesting to study the place that corporate diplomacy can occupy within the company, the profile that a corporate diplomat should have, and how corporate diplomacy is a driving power of open innovation for specific key sectors.

In addition to this, more research is needed on the relationship between corporate diplomacy, dynamic capabilities, and open innovation, because different studies show that there is a relationship between diplomacy and business results. In fact, diplomacy contributes to the improvement of the relations of MNCs with destination countries, and it is part of the corporate culture of the companies that develop it.

It would also be interesting to carry out a biometric study of corporate diplomacy literature to establish the different roles of diplomacy in the four-helix model of open innovations proposed by Yun et al. (2019, 2020a) [

8,

9].

Finally, another future line of research could be to document, through a case study, the work carried out by MNCs to achieve PPE during the COVID-19 pandemic through their networks and corporate diplomacy strategies. Therefore, we ask: Is corporate diplomacy open innovation? Is corporate diplomacy open innovation macro-dynamics? Is corporate diplomacy open innovation micro-dynamics? How can corporate diplomacy contribute empirically to open innovation?